User login

24-7 Dressing Technique to Optimize Wound Healing After Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Practice Gap

Management of surgical wounds is a critical component of postsurgical care for patients during recovery at home.1 However, postoperative wound care can be troublesome, time consuming, and expensive. Common problems with current standard dressings include an increased risk for infection, pain, and wound damage with frequent dressing changes.2-4

Patients often are unable to take proper care of wounds themselves and may not have the financial means or social support to have others assist them.4-6 For these patients, the option of a hassle-free dressing that they can leave on until their follow-up appointment is preferred. In our experience, what we call a 24-7 bandage has been remarkably successful in patients who are vulnerable to wound complications.

We report a comfortable, effective, and simple technique for wound dressings after dermatologic surgery.

The Technique

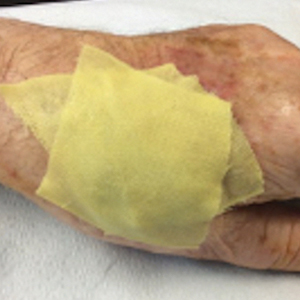

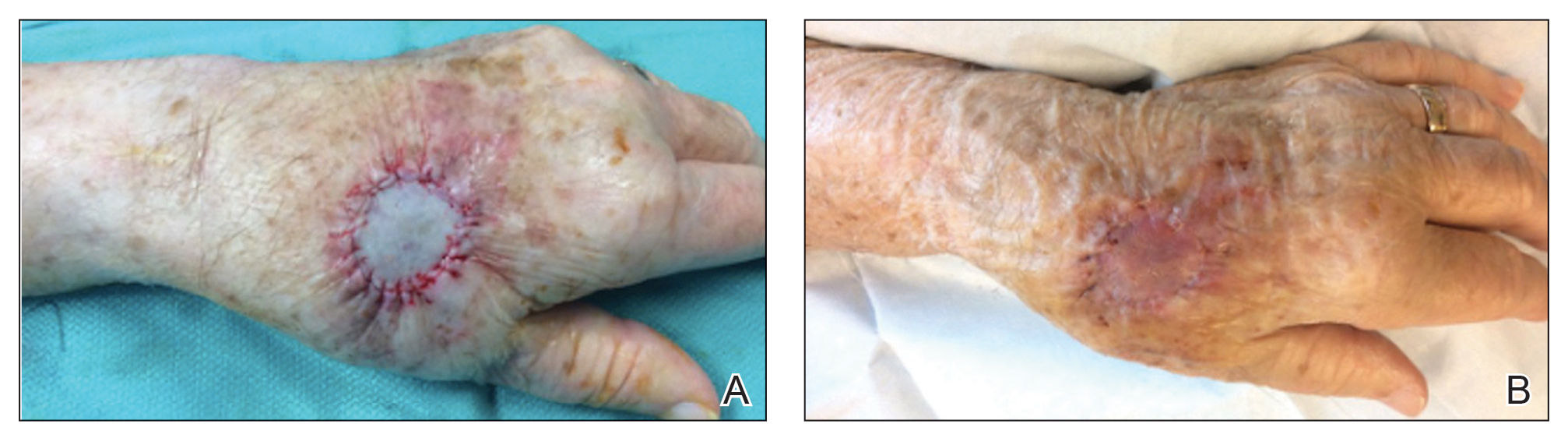

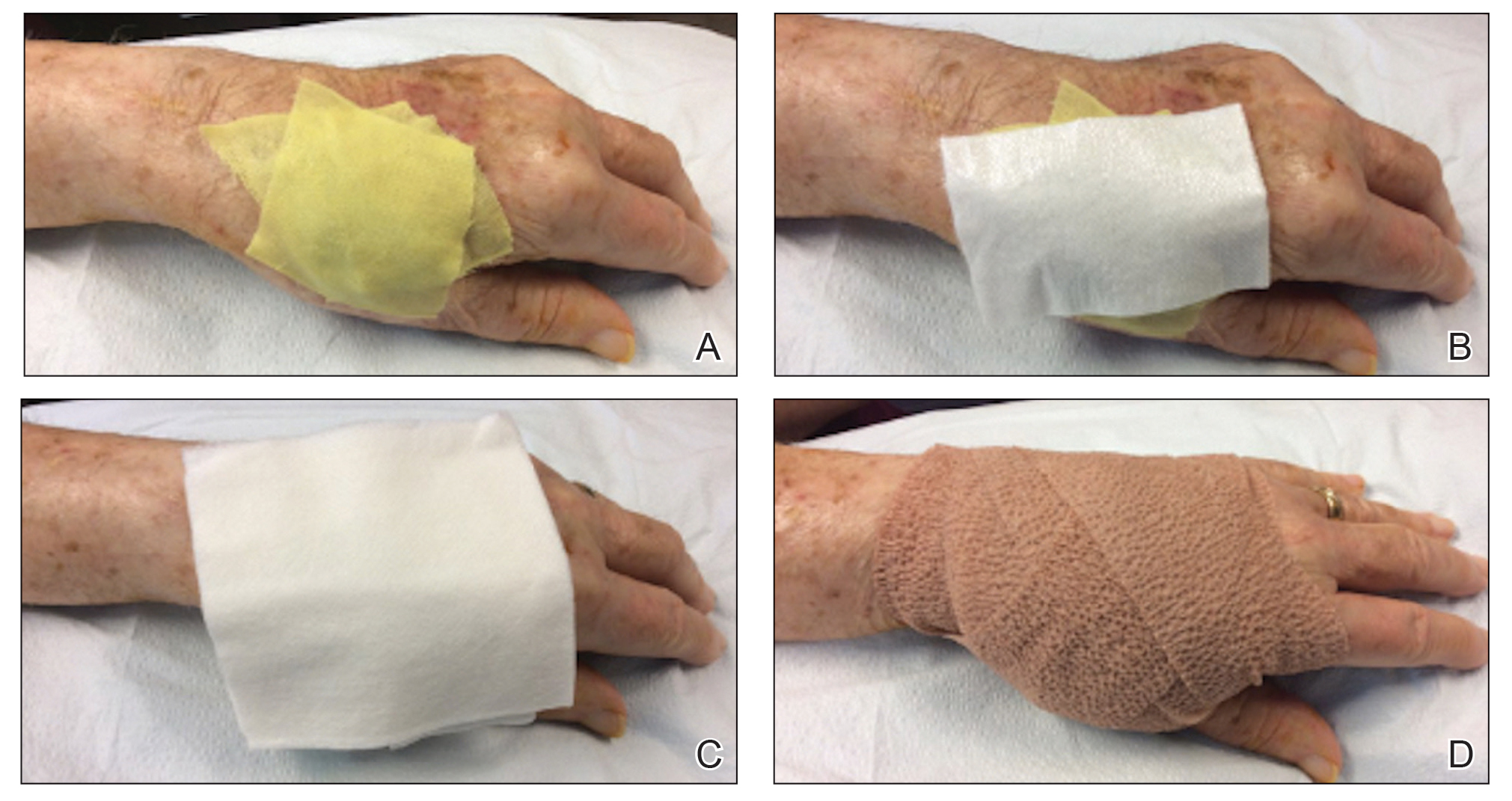

In Figure 1, we demonstrate a simple dressing technique that can be used to optimize wound healing in patients unable to provide adequate wound care for themselves:

1. The surgical site is covered with mupirocin ointment, followed by bismuth tribromophenate gauze (Figure 1A). The bismuth-impregnated gauze helps make the dressing nonadherent and moderately occlusive. It also adds moisture to the wound bed.

2. The gauze is then covered with excess mupirocin. A nonadherent dressing is applied (Figure 1B).

3. The entire area is covered with gauze and cover-roll nonlatex bandaging tape to ensure maximum adhesion (Figures 1C and 1D).

4. When the surgical site is on an extremity, it is wrapped in a self-adherent wrap or bandage roll to prevent clothing from pulling the tape loose.

Once this dressing technique is performed in the office, the bandage requires no wound care at home other than ensuring that the bandage is kept dry. The 24-7 dressing can be left on the surgical site for 7 days until the follow-up appointment. If necessary, it also can be applied for a second week after bolster removal or for multiple weeks following advanced flap repair.

Our patients find this dressing comfortable and unobtrusive. It is easy for the staff to apply and inexpensive.

Practical Implications

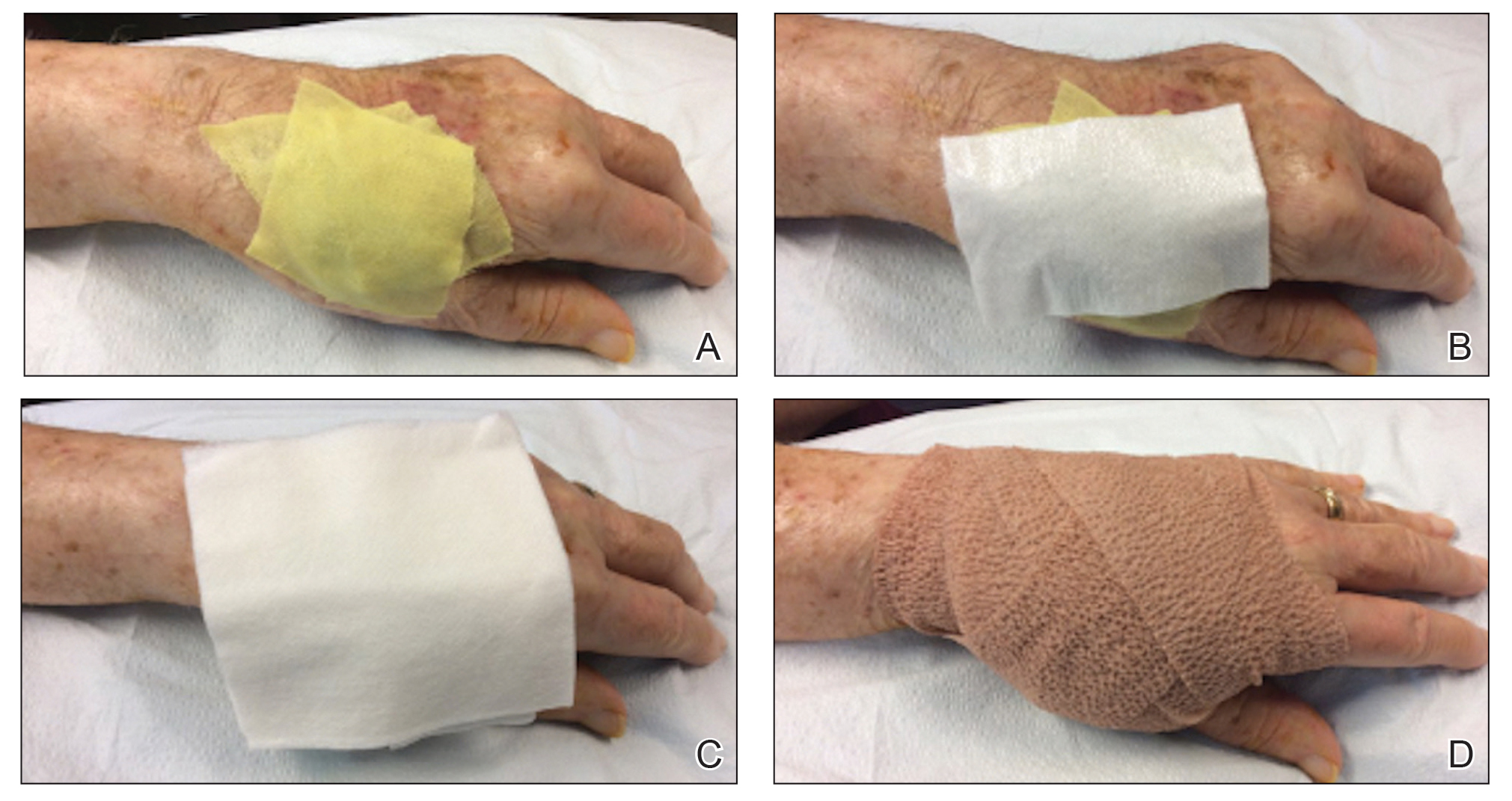

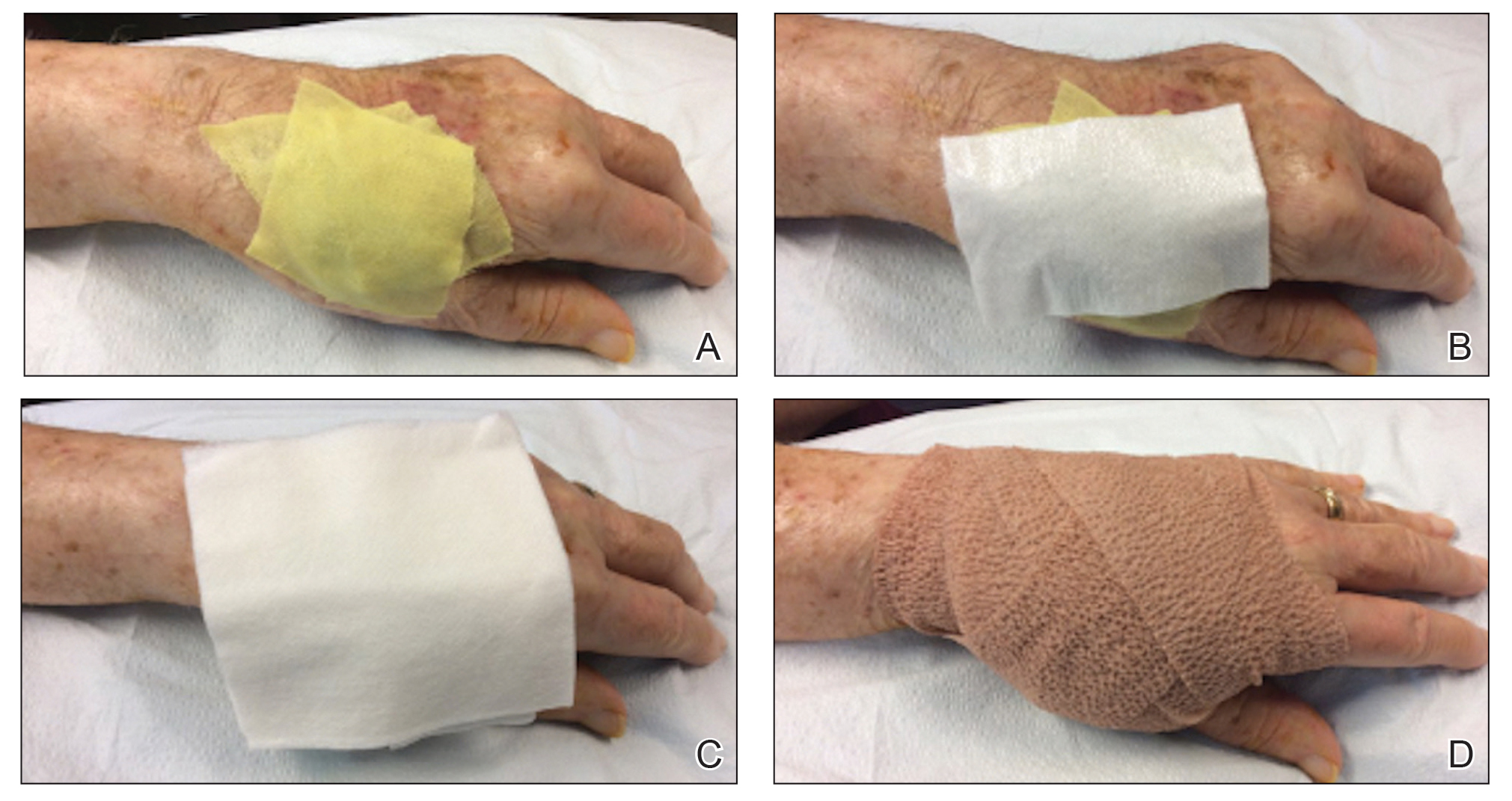

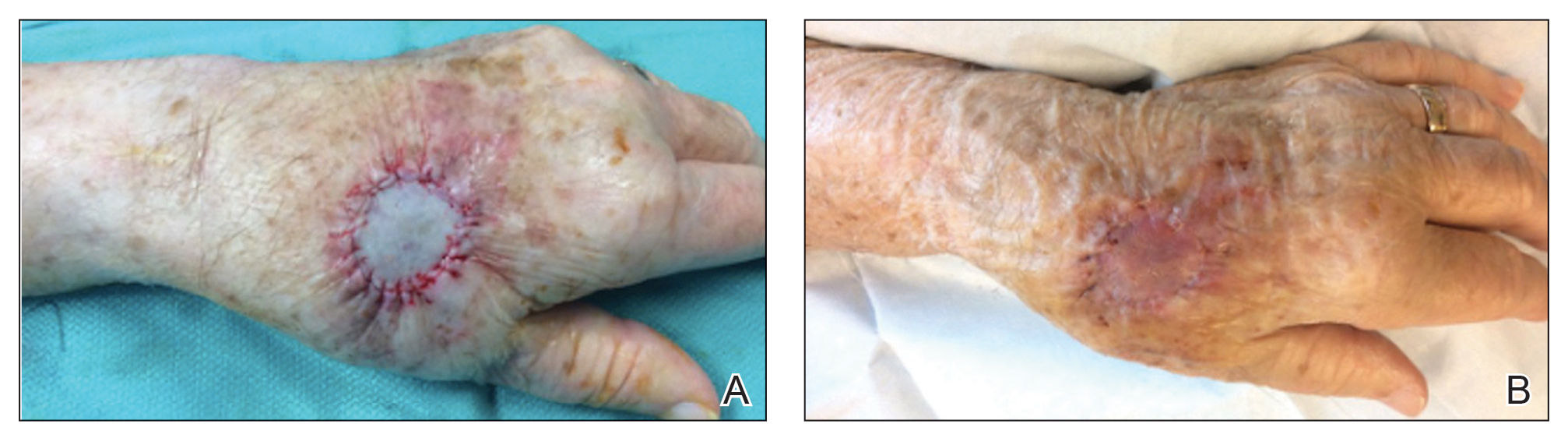

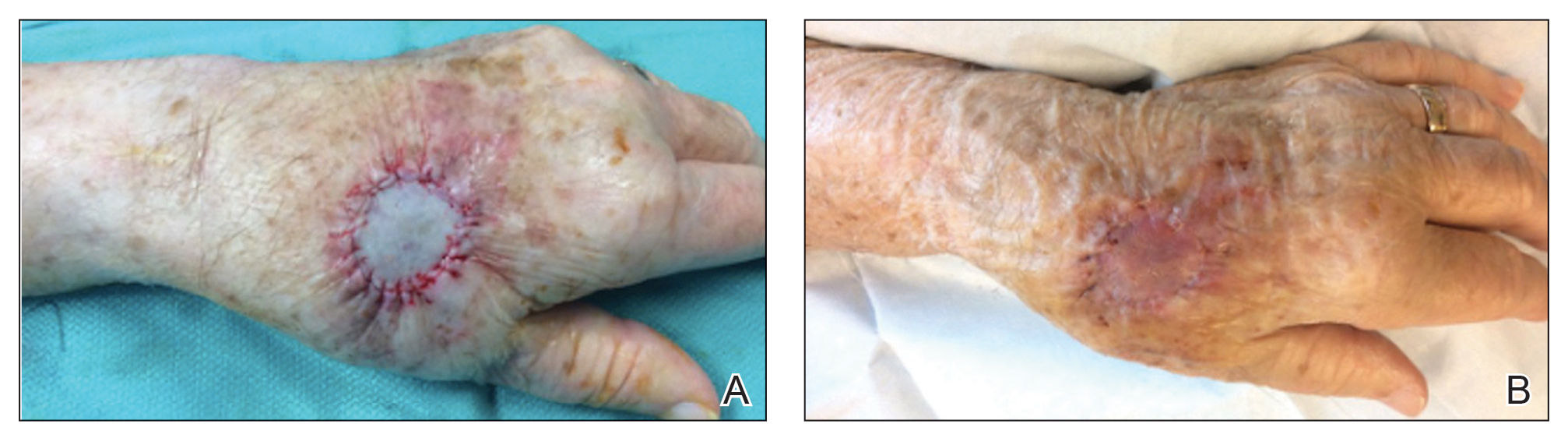

We have treated approximately 200 patients with the 24-7 dressing technique. Our experience is that these patients demonstrated an excellent aesthetic outcome without complications (Figure 2). We have successfully utilized the dressing in several anatomic locations, including the arms, legs, neck, face, and scalp. We use mupirocin for its antimicrobial activity, but we have not performed a study at our clinic looking at the difference between rate of infection and wound healing using mupirocin vs petrolatum. We prefer adding bulk gauze under the tape and leaving the dressing on for 7 days. We seldom have issues with bleeding, and if there is an issue, the patient is told to come back to our clinic so we can change the bandage for them.

This dressing technique is cost-effective to the patient and clinical staff, provides protection from potential injury to the sutures, decreases the risk for infection, and removes the stress and burden on the patient and family of frequent dressing changes. Furthermore, by preventing patient manipulation and frequent removal of the dressing, the wound retains adequate moisture during healing. This technique also can be applied to a variety of outpatient procedures other than Mohs micrographic surgery.

We hope that our colleagues find this 24-7 dressing technique for dressing wounds after dermatologic surgery useful in patient populations vulnerable to wound complications.

- Winton GB, Salasche SJ. Wound dressings for dermatologic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;13:1026-1044.

- Broussard KC, Powers JG. Wound dressings: selecting the most appropriate type. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:449-459.

- Kannon GA, Garrett AB. Moist wound healing with occlusive dressings. a clinical review. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:583-590.

- Jones AM, San Miguel L. Are modern wound dressings a clinical and cost-effective alternative to the use of gauze? J Wound Care. 2006;15:65-66.

- Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H, Goossens A. Occlusive vs gauze dressings for local wound care in surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:950-955.

- Sood A, Granick MS, Tomaselli NL. Wound dressings and comparative effectiveness data. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014;3;511-529.

Practice Gap

Management of surgical wounds is a critical component of postsurgical care for patients during recovery at home.1 However, postoperative wound care can be troublesome, time consuming, and expensive. Common problems with current standard dressings include an increased risk for infection, pain, and wound damage with frequent dressing changes.2-4

Patients often are unable to take proper care of wounds themselves and may not have the financial means or social support to have others assist them.4-6 For these patients, the option of a hassle-free dressing that they can leave on until their follow-up appointment is preferred. In our experience, what we call a 24-7 bandage has been remarkably successful in patients who are vulnerable to wound complications.

We report a comfortable, effective, and simple technique for wound dressings after dermatologic surgery.

The Technique

In Figure 1, we demonstrate a simple dressing technique that can be used to optimize wound healing in patients unable to provide adequate wound care for themselves:

1. The surgical site is covered with mupirocin ointment, followed by bismuth tribromophenate gauze (Figure 1A). The bismuth-impregnated gauze helps make the dressing nonadherent and moderately occlusive. It also adds moisture to the wound bed.

2. The gauze is then covered with excess mupirocin. A nonadherent dressing is applied (Figure 1B).

3. The entire area is covered with gauze and cover-roll nonlatex bandaging tape to ensure maximum adhesion (Figures 1C and 1D).

4. When the surgical site is on an extremity, it is wrapped in a self-adherent wrap or bandage roll to prevent clothing from pulling the tape loose.

Once this dressing technique is performed in the office, the bandage requires no wound care at home other than ensuring that the bandage is kept dry. The 24-7 dressing can be left on the surgical site for 7 days until the follow-up appointment. If necessary, it also can be applied for a second week after bolster removal or for multiple weeks following advanced flap repair.

Our patients find this dressing comfortable and unobtrusive. It is easy for the staff to apply and inexpensive.

Practical Implications

We have treated approximately 200 patients with the 24-7 dressing technique. Our experience is that these patients demonstrated an excellent aesthetic outcome without complications (Figure 2). We have successfully utilized the dressing in several anatomic locations, including the arms, legs, neck, face, and scalp. We use mupirocin for its antimicrobial activity, but we have not performed a study at our clinic looking at the difference between rate of infection and wound healing using mupirocin vs petrolatum. We prefer adding bulk gauze under the tape and leaving the dressing on for 7 days. We seldom have issues with bleeding, and if there is an issue, the patient is told to come back to our clinic so we can change the bandage for them.

This dressing technique is cost-effective to the patient and clinical staff, provides protection from potential injury to the sutures, decreases the risk for infection, and removes the stress and burden on the patient and family of frequent dressing changes. Furthermore, by preventing patient manipulation and frequent removal of the dressing, the wound retains adequate moisture during healing. This technique also can be applied to a variety of outpatient procedures other than Mohs micrographic surgery.

We hope that our colleagues find this 24-7 dressing technique for dressing wounds after dermatologic surgery useful in patient populations vulnerable to wound complications.

Practice Gap

Management of surgical wounds is a critical component of postsurgical care for patients during recovery at home.1 However, postoperative wound care can be troublesome, time consuming, and expensive. Common problems with current standard dressings include an increased risk for infection, pain, and wound damage with frequent dressing changes.2-4

Patients often are unable to take proper care of wounds themselves and may not have the financial means or social support to have others assist them.4-6 For these patients, the option of a hassle-free dressing that they can leave on until their follow-up appointment is preferred. In our experience, what we call a 24-7 bandage has been remarkably successful in patients who are vulnerable to wound complications.

We report a comfortable, effective, and simple technique for wound dressings after dermatologic surgery.

The Technique

In Figure 1, we demonstrate a simple dressing technique that can be used to optimize wound healing in patients unable to provide adequate wound care for themselves:

1. The surgical site is covered with mupirocin ointment, followed by bismuth tribromophenate gauze (Figure 1A). The bismuth-impregnated gauze helps make the dressing nonadherent and moderately occlusive. It also adds moisture to the wound bed.

2. The gauze is then covered with excess mupirocin. A nonadherent dressing is applied (Figure 1B).

3. The entire area is covered with gauze and cover-roll nonlatex bandaging tape to ensure maximum adhesion (Figures 1C and 1D).

4. When the surgical site is on an extremity, it is wrapped in a self-adherent wrap or bandage roll to prevent clothing from pulling the tape loose.

Once this dressing technique is performed in the office, the bandage requires no wound care at home other than ensuring that the bandage is kept dry. The 24-7 dressing can be left on the surgical site for 7 days until the follow-up appointment. If necessary, it also can be applied for a second week after bolster removal or for multiple weeks following advanced flap repair.

Our patients find this dressing comfortable and unobtrusive. It is easy for the staff to apply and inexpensive.

Practical Implications

We have treated approximately 200 patients with the 24-7 dressing technique. Our experience is that these patients demonstrated an excellent aesthetic outcome without complications (Figure 2). We have successfully utilized the dressing in several anatomic locations, including the arms, legs, neck, face, and scalp. We use mupirocin for its antimicrobial activity, but we have not performed a study at our clinic looking at the difference between rate of infection and wound healing using mupirocin vs petrolatum. We prefer adding bulk gauze under the tape and leaving the dressing on for 7 days. We seldom have issues with bleeding, and if there is an issue, the patient is told to come back to our clinic so we can change the bandage for them.

This dressing technique is cost-effective to the patient and clinical staff, provides protection from potential injury to the sutures, decreases the risk for infection, and removes the stress and burden on the patient and family of frequent dressing changes. Furthermore, by preventing patient manipulation and frequent removal of the dressing, the wound retains adequate moisture during healing. This technique also can be applied to a variety of outpatient procedures other than Mohs micrographic surgery.

We hope that our colleagues find this 24-7 dressing technique for dressing wounds after dermatologic surgery useful in patient populations vulnerable to wound complications.

- Winton GB, Salasche SJ. Wound dressings for dermatologic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;13:1026-1044.

- Broussard KC, Powers JG. Wound dressings: selecting the most appropriate type. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:449-459.

- Kannon GA, Garrett AB. Moist wound healing with occlusive dressings. a clinical review. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:583-590.

- Jones AM, San Miguel L. Are modern wound dressings a clinical and cost-effective alternative to the use of gauze? J Wound Care. 2006;15:65-66.

- Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H, Goossens A. Occlusive vs gauze dressings for local wound care in surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:950-955.

- Sood A, Granick MS, Tomaselli NL. Wound dressings and comparative effectiveness data. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014;3;511-529.

- Winton GB, Salasche SJ. Wound dressings for dermatologic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;13:1026-1044.

- Broussard KC, Powers JG. Wound dressings: selecting the most appropriate type. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:449-459.

- Kannon GA, Garrett AB. Moist wound healing with occlusive dressings. a clinical review. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:583-590.

- Jones AM, San Miguel L. Are modern wound dressings a clinical and cost-effective alternative to the use of gauze? J Wound Care. 2006;15:65-66.

- Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H, Goossens A. Occlusive vs gauze dressings for local wound care in surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:950-955.

- Sood A, Granick MS, Tomaselli NL. Wound dressings and comparative effectiveness data. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014;3;511-529.

Andecaliximab disappoints in advanced gastric cancer

Objective response rates were 50.5% in the ADX arm and 41.1% in the placebo arm (stratified odds ratio, 1.47; P = .049), but this did not translate to improved survival.

The median overall survival (OS) was 12.5 months in the ADX arm and 11.8 months in the placebo arm (stratified hazard ratio, 0.93; P = .56). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.5 months and 7.1 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.84; P = .10).

Manish A. Shah, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The lack of improvement when ADX was added to mFOLFOX6 was despite encouraging antitumor activity seen with the combination in a phase 1 and phase 1b study, the authors noted.

“Despite compelling early-phase data, the addition of ADX did not improve outcomes in an unselected patient population,” the authors wrote. “Tissue or blood samples were not available for correlative analyses to understand why ADX was less active than expected or to identify any gastric cancer subset that may derive greater benefit with ADX.”

The researchers did note, however, that subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older.

Study details

Participants in the double-blind GAMMA-1 trial were adults with confirmed locally advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. They were enrolled at 132 centers worldwide between Oct. 13, 2015, and May 15, 2019.

There were 432 patients randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 plus either 800 mg of ADX (n = 218) or placebo (n = 214) infused on days 1 and 15 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression or intolerance.

As noted before, there was a significant improvement in response rate with the addition of ADX (P = .049) but no significant improvements in PFS (P = .10) or OS (P = .56).

On the other hand, subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older. The authors said this result is intriguing and warrants further study.

Among patients aged 65 and older, the median OS was 13.9 months in the ADX arm and 10.5 months in the placebo arm (stratified HR, 0.64; P = .03). The median PFS was 8.7 months and 5.6 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.50; P < .001). However, the P values were not adjusted for multiplicity.

No significant differences were seen between the groups with respect to safety outcomes. Serious adverse events occurred in 47.7% of patients in the ADX arm and 51.4% of those in the placebo arm. Nine patients in the ADX arm and 13 in the placebo arm discontinued the study because of adverse events.

The GAMMA-1 trial was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. The authors disclosed relationships with Gilead and many other companies.

Objective response rates were 50.5% in the ADX arm and 41.1% in the placebo arm (stratified odds ratio, 1.47; P = .049), but this did not translate to improved survival.

The median overall survival (OS) was 12.5 months in the ADX arm and 11.8 months in the placebo arm (stratified hazard ratio, 0.93; P = .56). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.5 months and 7.1 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.84; P = .10).

Manish A. Shah, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The lack of improvement when ADX was added to mFOLFOX6 was despite encouraging antitumor activity seen with the combination in a phase 1 and phase 1b study, the authors noted.

“Despite compelling early-phase data, the addition of ADX did not improve outcomes in an unselected patient population,” the authors wrote. “Tissue or blood samples were not available for correlative analyses to understand why ADX was less active than expected or to identify any gastric cancer subset that may derive greater benefit with ADX.”

The researchers did note, however, that subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older.

Study details

Participants in the double-blind GAMMA-1 trial were adults with confirmed locally advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. They were enrolled at 132 centers worldwide between Oct. 13, 2015, and May 15, 2019.

There were 432 patients randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 plus either 800 mg of ADX (n = 218) or placebo (n = 214) infused on days 1 and 15 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression or intolerance.

As noted before, there was a significant improvement in response rate with the addition of ADX (P = .049) but no significant improvements in PFS (P = .10) or OS (P = .56).

On the other hand, subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older. The authors said this result is intriguing and warrants further study.

Among patients aged 65 and older, the median OS was 13.9 months in the ADX arm and 10.5 months in the placebo arm (stratified HR, 0.64; P = .03). The median PFS was 8.7 months and 5.6 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.50; P < .001). However, the P values were not adjusted for multiplicity.

No significant differences were seen between the groups with respect to safety outcomes. Serious adverse events occurred in 47.7% of patients in the ADX arm and 51.4% of those in the placebo arm. Nine patients in the ADX arm and 13 in the placebo arm discontinued the study because of adverse events.

The GAMMA-1 trial was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. The authors disclosed relationships with Gilead and many other companies.

Objective response rates were 50.5% in the ADX arm and 41.1% in the placebo arm (stratified odds ratio, 1.47; P = .049), but this did not translate to improved survival.

The median overall survival (OS) was 12.5 months in the ADX arm and 11.8 months in the placebo arm (stratified hazard ratio, 0.93; P = .56). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.5 months and 7.1 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.84; P = .10).

Manish A. Shah, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The lack of improvement when ADX was added to mFOLFOX6 was despite encouraging antitumor activity seen with the combination in a phase 1 and phase 1b study, the authors noted.

“Despite compelling early-phase data, the addition of ADX did not improve outcomes in an unselected patient population,” the authors wrote. “Tissue or blood samples were not available for correlative analyses to understand why ADX was less active than expected or to identify any gastric cancer subset that may derive greater benefit with ADX.”

The researchers did note, however, that subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older.

Study details

Participants in the double-blind GAMMA-1 trial were adults with confirmed locally advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. They were enrolled at 132 centers worldwide between Oct. 13, 2015, and May 15, 2019.

There were 432 patients randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 plus either 800 mg of ADX (n = 218) or placebo (n = 214) infused on days 1 and 15 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression or intolerance.

As noted before, there was a significant improvement in response rate with the addition of ADX (P = .049) but no significant improvements in PFS (P = .10) or OS (P = .56).

On the other hand, subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits with ADX in patients aged 65 years and older. The authors said this result is intriguing and warrants further study.

Among patients aged 65 and older, the median OS was 13.9 months in the ADX arm and 10.5 months in the placebo arm (stratified HR, 0.64; P = .03). The median PFS was 8.7 months and 5.6 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.50; P < .001). However, the P values were not adjusted for multiplicity.

No significant differences were seen between the groups with respect to safety outcomes. Serious adverse events occurred in 47.7% of patients in the ADX arm and 51.4% of those in the placebo arm. Nine patients in the ADX arm and 13 in the placebo arm discontinued the study because of adverse events.

The GAMMA-1 trial was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. The authors disclosed relationships with Gilead and many other companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Bleeding disorder diagnoses delayed by years in girls and women

Diagnosis of bleeding disorders in girls and women can lag behind diagnosis in boys and men by more than a decade, meaning needless delays in treatment and poor quality of life for many with hemophilia or related conditions.

“There is increasing awareness about issues faced by women and girls with inherited bleeding disorders, but disparities still exist both in both access to diagnosis and treatment,” said Roseline D’Oiron, MD, from Hôpital Bicêtre in Paris.

“Diagnosis, when it is made, is often made late, particularly in women. Indeed, a recent study from the European Hemophilia Consortium including more than 700 women with bleeding disorders showed that the median age at diagnosis was 16 years old,” she said during the annual congress of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

She said that delayed diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls may be caused by a lack of knowledge by patients, families, and general practitioners about family history of bleeding disorders, abnormal bleeding events, and heavy menstrual bleeding. In addition, despite the frequency and severity of heavy bleeding events, patients, their families, and caregivers may underestimate the effect on the patient’s quality of life.

Disparities documented

Dr. D’Oiron pointed to several studies showing clear sex-based disparities in time to diagnosis. For example, a study published in Haemophilia showed that in 22 girls with hemophilia A or hemophilia B, the diagnosis of severe hemophilia was delayed by a median of 6.5 months compared with the diagnosis in boys, and a diagnosis of moderate hemophilia in girls was delayed by a median of 39 months.

In a second, single-center study comparing 44 women and girls with mild hemophilia (factor VIII or factor XI levels from 5 to 50 IU/dL) with 77 men and boys with mild hemophilia, the mean age at diagnosis was 31.63 years versus 19.18 years, respectively – a delay of 12.45 years.

A third study comparing 442 girls/women and 442 boys/men with mild hemophilia in France showed a difference of 6.07 years in diagnosis: the median age for girls/women at diagnosis was 16.91 years versus10.84 years for boys/men.

Why it matters

Dr. D’Oiron described the case of a patient named Clare, who first experienced, at age 8, 12 hours of bleeding following a dental procedure. At age 12.5, she began having heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss school for a few days each month, to be feel tired, and have poor-quality sleep.

Despite repeated bleeding episodes, severe anemia, and iron deficiency, her hemophilia was not suspected until after her 16th birthday, and a definitive diagnosis of hemophilia in both Clare and her mother was finally made when Clare was past 17, when a nonsense variant factor in F8, the gene encoding for factor VIII, was detected.

“For Clare, it took more the 8 years after the first bleeding symptoms, and nearly 4 years after presenting with heavy menstrual bleeding to recognize that she had a bleeding problem,” she said.

In total, Clare had about 450 days of heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss an estimated 140 days of school because of the delayed diagnosis and treatment.

“In my view, this is the main argument why it is urgent for these patients to achieve diagnosis early: this is to reduce the duration [of] a very poor quality of life,” Dr. D’Oiron said.

Barriers to diagnosis

Patients and families have reported difficulty distinguishing normal bleeding from abnormal symptoms, and girls may be reluctant to discuss their symptoms with their family or peers. In addition, primary care practitioners may not recognize the severity of the symptoms and therefore may not refer patients to hematologists for further workup.

These findings emphasize the need for improved tools to help patients differentiate between normal and abnormal bleeding, using symptom recognition–based language tools that can lead to early testing and application of accurate diagnostic tools, she said.

Standardization of definitions can help to improve screening and diagnosis, Dr. D’Oiron said, pointing to a recent study in Blood Advances proposing definitions for future research in von Willebrand disease.

For example, the authors of that study proposed a definition of heavy menstrual bleeding to include any of the following:

- Bleeding lasting 8 or more days

- Bleeding that consistently soaks through one or more sanitary protections every 2 hours on multiple days

- Requires use of more than one sanitary protection item at a time

- Requires changing sanitary protection during the night

- Is associated with repeat passing of blood clots

- Has a Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart score greater than 100.

Problem and solutions

Answering the question posed in the title of her talk, Dr. D’Oiron said: “Yes, we do have a problem with the diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls, but we also have solutions.”

The solutions include family and patient outreach efforts; communication to improve awareness; inclusion of general practitioners in the circle of care; and early screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

A bleeding disorders specialist who was not involved in the study said that Dr. D’Oiron’s report closely reflects what she sees in the clinic.

“I do pediatrics, and usually what happens is that I see a teenager with heavy menstrual bleeding and we take her history, and we find out that Mom and multiple female family members have had horrible menstrual bleeding, possibly many of whom have had hysterectomies for it, and then diagnosing the parents and other family members after diagnosing the girl that we’re seeing” said Veronica H. Flood, MD, from the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“It is unfortunately a very real thing,” she added.

Reasons for the delay likely include lack of awareness of bleeding disorders.

“If you present to a hematologist, we think about bleeding disorders, but if you present to a primary care physician, they don’t always have that on their radar,” she said.

Additionally, a girl from a family with a history of heavy menstrual bleeding may just assume that what she is experiencing is “normal,” despite the serious affect it has on her quality of life, Dr. Flood said.

Dr. D’Oiron’s research is supported by her institution, the French Hemophilia Association, FranceCoag and Mhemon, the European Hemophilia Consortium, and the World Federation of Hemophilia. She reported advisory board or invited speaker activities for multiple companies. Dr. Flood reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Diagnosis of bleeding disorders in girls and women can lag behind diagnosis in boys and men by more than a decade, meaning needless delays in treatment and poor quality of life for many with hemophilia or related conditions.

“There is increasing awareness about issues faced by women and girls with inherited bleeding disorders, but disparities still exist both in both access to diagnosis and treatment,” said Roseline D’Oiron, MD, from Hôpital Bicêtre in Paris.

“Diagnosis, when it is made, is often made late, particularly in women. Indeed, a recent study from the European Hemophilia Consortium including more than 700 women with bleeding disorders showed that the median age at diagnosis was 16 years old,” she said during the annual congress of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

She said that delayed diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls may be caused by a lack of knowledge by patients, families, and general practitioners about family history of bleeding disorders, abnormal bleeding events, and heavy menstrual bleeding. In addition, despite the frequency and severity of heavy bleeding events, patients, their families, and caregivers may underestimate the effect on the patient’s quality of life.

Disparities documented

Dr. D’Oiron pointed to several studies showing clear sex-based disparities in time to diagnosis. For example, a study published in Haemophilia showed that in 22 girls with hemophilia A or hemophilia B, the diagnosis of severe hemophilia was delayed by a median of 6.5 months compared with the diagnosis in boys, and a diagnosis of moderate hemophilia in girls was delayed by a median of 39 months.

In a second, single-center study comparing 44 women and girls with mild hemophilia (factor VIII or factor XI levels from 5 to 50 IU/dL) with 77 men and boys with mild hemophilia, the mean age at diagnosis was 31.63 years versus 19.18 years, respectively – a delay of 12.45 years.

A third study comparing 442 girls/women and 442 boys/men with mild hemophilia in France showed a difference of 6.07 years in diagnosis: the median age for girls/women at diagnosis was 16.91 years versus10.84 years for boys/men.

Why it matters

Dr. D’Oiron described the case of a patient named Clare, who first experienced, at age 8, 12 hours of bleeding following a dental procedure. At age 12.5, she began having heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss school for a few days each month, to be feel tired, and have poor-quality sleep.

Despite repeated bleeding episodes, severe anemia, and iron deficiency, her hemophilia was not suspected until after her 16th birthday, and a definitive diagnosis of hemophilia in both Clare and her mother was finally made when Clare was past 17, when a nonsense variant factor in F8, the gene encoding for factor VIII, was detected.

“For Clare, it took more the 8 years after the first bleeding symptoms, and nearly 4 years after presenting with heavy menstrual bleeding to recognize that she had a bleeding problem,” she said.

In total, Clare had about 450 days of heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss an estimated 140 days of school because of the delayed diagnosis and treatment.

“In my view, this is the main argument why it is urgent for these patients to achieve diagnosis early: this is to reduce the duration [of] a very poor quality of life,” Dr. D’Oiron said.

Barriers to diagnosis

Patients and families have reported difficulty distinguishing normal bleeding from abnormal symptoms, and girls may be reluctant to discuss their symptoms with their family or peers. In addition, primary care practitioners may not recognize the severity of the symptoms and therefore may not refer patients to hematologists for further workup.

These findings emphasize the need for improved tools to help patients differentiate between normal and abnormal bleeding, using symptom recognition–based language tools that can lead to early testing and application of accurate diagnostic tools, she said.

Standardization of definitions can help to improve screening and diagnosis, Dr. D’Oiron said, pointing to a recent study in Blood Advances proposing definitions for future research in von Willebrand disease.

For example, the authors of that study proposed a definition of heavy menstrual bleeding to include any of the following:

- Bleeding lasting 8 or more days

- Bleeding that consistently soaks through one or more sanitary protections every 2 hours on multiple days

- Requires use of more than one sanitary protection item at a time

- Requires changing sanitary protection during the night

- Is associated with repeat passing of blood clots

- Has a Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart score greater than 100.

Problem and solutions

Answering the question posed in the title of her talk, Dr. D’Oiron said: “Yes, we do have a problem with the diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls, but we also have solutions.”

The solutions include family and patient outreach efforts; communication to improve awareness; inclusion of general practitioners in the circle of care; and early screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

A bleeding disorders specialist who was not involved in the study said that Dr. D’Oiron’s report closely reflects what she sees in the clinic.

“I do pediatrics, and usually what happens is that I see a teenager with heavy menstrual bleeding and we take her history, and we find out that Mom and multiple female family members have had horrible menstrual bleeding, possibly many of whom have had hysterectomies for it, and then diagnosing the parents and other family members after diagnosing the girl that we’re seeing” said Veronica H. Flood, MD, from the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“It is unfortunately a very real thing,” she added.

Reasons for the delay likely include lack of awareness of bleeding disorders.

“If you present to a hematologist, we think about bleeding disorders, but if you present to a primary care physician, they don’t always have that on their radar,” she said.

Additionally, a girl from a family with a history of heavy menstrual bleeding may just assume that what she is experiencing is “normal,” despite the serious affect it has on her quality of life, Dr. Flood said.

Dr. D’Oiron’s research is supported by her institution, the French Hemophilia Association, FranceCoag and Mhemon, the European Hemophilia Consortium, and the World Federation of Hemophilia. She reported advisory board or invited speaker activities for multiple companies. Dr. Flood reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Diagnosis of bleeding disorders in girls and women can lag behind diagnosis in boys and men by more than a decade, meaning needless delays in treatment and poor quality of life for many with hemophilia or related conditions.

“There is increasing awareness about issues faced by women and girls with inherited bleeding disorders, but disparities still exist both in both access to diagnosis and treatment,” said Roseline D’Oiron, MD, from Hôpital Bicêtre in Paris.

“Diagnosis, when it is made, is often made late, particularly in women. Indeed, a recent study from the European Hemophilia Consortium including more than 700 women with bleeding disorders showed that the median age at diagnosis was 16 years old,” she said during the annual congress of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

She said that delayed diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls may be caused by a lack of knowledge by patients, families, and general practitioners about family history of bleeding disorders, abnormal bleeding events, and heavy menstrual bleeding. In addition, despite the frequency and severity of heavy bleeding events, patients, their families, and caregivers may underestimate the effect on the patient’s quality of life.

Disparities documented

Dr. D’Oiron pointed to several studies showing clear sex-based disparities in time to diagnosis. For example, a study published in Haemophilia showed that in 22 girls with hemophilia A or hemophilia B, the diagnosis of severe hemophilia was delayed by a median of 6.5 months compared with the diagnosis in boys, and a diagnosis of moderate hemophilia in girls was delayed by a median of 39 months.

In a second, single-center study comparing 44 women and girls with mild hemophilia (factor VIII or factor XI levels from 5 to 50 IU/dL) with 77 men and boys with mild hemophilia, the mean age at diagnosis was 31.63 years versus 19.18 years, respectively – a delay of 12.45 years.

A third study comparing 442 girls/women and 442 boys/men with mild hemophilia in France showed a difference of 6.07 years in diagnosis: the median age for girls/women at diagnosis was 16.91 years versus10.84 years for boys/men.

Why it matters

Dr. D’Oiron described the case of a patient named Clare, who first experienced, at age 8, 12 hours of bleeding following a dental procedure. At age 12.5, she began having heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss school for a few days each month, to be feel tired, and have poor-quality sleep.

Despite repeated bleeding episodes, severe anemia, and iron deficiency, her hemophilia was not suspected until after her 16th birthday, and a definitive diagnosis of hemophilia in both Clare and her mother was finally made when Clare was past 17, when a nonsense variant factor in F8, the gene encoding for factor VIII, was detected.

“For Clare, it took more the 8 years after the first bleeding symptoms, and nearly 4 years after presenting with heavy menstrual bleeding to recognize that she had a bleeding problem,” she said.

In total, Clare had about 450 days of heavy menstrual bleeding, causing her to miss an estimated 140 days of school because of the delayed diagnosis and treatment.

“In my view, this is the main argument why it is urgent for these patients to achieve diagnosis early: this is to reduce the duration [of] a very poor quality of life,” Dr. D’Oiron said.

Barriers to diagnosis

Patients and families have reported difficulty distinguishing normal bleeding from abnormal symptoms, and girls may be reluctant to discuss their symptoms with their family or peers. In addition, primary care practitioners may not recognize the severity of the symptoms and therefore may not refer patients to hematologists for further workup.

These findings emphasize the need for improved tools to help patients differentiate between normal and abnormal bleeding, using symptom recognition–based language tools that can lead to early testing and application of accurate diagnostic tools, she said.

Standardization of definitions can help to improve screening and diagnosis, Dr. D’Oiron said, pointing to a recent study in Blood Advances proposing definitions for future research in von Willebrand disease.

For example, the authors of that study proposed a definition of heavy menstrual bleeding to include any of the following:

- Bleeding lasting 8 or more days

- Bleeding that consistently soaks through one or more sanitary protections every 2 hours on multiple days

- Requires use of more than one sanitary protection item at a time

- Requires changing sanitary protection during the night

- Is associated with repeat passing of blood clots

- Has a Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart score greater than 100.

Problem and solutions

Answering the question posed in the title of her talk, Dr. D’Oiron said: “Yes, we do have a problem with the diagnosis of bleeding disorders in women and girls, but we also have solutions.”

The solutions include family and patient outreach efforts; communication to improve awareness; inclusion of general practitioners in the circle of care; and early screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

A bleeding disorders specialist who was not involved in the study said that Dr. D’Oiron’s report closely reflects what she sees in the clinic.

“I do pediatrics, and usually what happens is that I see a teenager with heavy menstrual bleeding and we take her history, and we find out that Mom and multiple female family members have had horrible menstrual bleeding, possibly many of whom have had hysterectomies for it, and then diagnosing the parents and other family members after diagnosing the girl that we’re seeing” said Veronica H. Flood, MD, from the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“It is unfortunately a very real thing,” she added.

Reasons for the delay likely include lack of awareness of bleeding disorders.

“If you present to a hematologist, we think about bleeding disorders, but if you present to a primary care physician, they don’t always have that on their radar,” she said.

Additionally, a girl from a family with a history of heavy menstrual bleeding may just assume that what she is experiencing is “normal,” despite the serious affect it has on her quality of life, Dr. Flood said.

Dr. D’Oiron’s research is supported by her institution, the French Hemophilia Association, FranceCoag and Mhemon, the European Hemophilia Consortium, and the World Federation of Hemophilia. She reported advisory board or invited speaker activities for multiple companies. Dr. Flood reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM EAHAD 2021

CDC: Vaccinated people can gather indoors without masks

People who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 can safely gather unmasked and inside with nonvulnerable people who are not yet immunized, according to long-awaited guidance released by the CDC.

“Today’s action represents an important first step. It is not our final destination,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said March 8 at a White House briefing. “As more people get vaccinated, levels of COVID-19 infection decline in communities, and as our understanding of COVID immunity improves, we look forward to updating these recommendations to the public.”

According to the new guidance, people who are at least 2 weeks out from their last dose can:

- Visit with other fully vaccinated people indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing.

- Visit with unvaccinated people from a single household who are at low risk for severe COVID-19 disease indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

- Avoid quarantine and testing following exposure to someone if they remain asymptomatic.

However, there are still restrictions that will remain until further data are collected. Those who are fully vaccinated must still:

- Wear masks and physically distance in public settings and around people at high risk for severe disease.

- Wear masks and physically distance when visiting unvaccinated people from more than one household.

- Avoid medium- and large-sized gatherings.

- Avoid travel.

People considered at high risk for severe disease include older adults and those with cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, Down syndrome, heart disease, heart failure, a weakened immune system, obesity, sickle cell disease, and type 2 diabetes. The category also includes pregnant women and smokers.

“In public spaces, fully vaccinated people should continue to follow guidance to protect themselves and others, including wearing a well-fitted mask, physical distancing (at least 6 feet), avoiding crowds, avoiding poorly ventilated spaces, covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands often, and following any applicable workplace or school guidance,” the guidance says. “Fully vaccinated people should still watch for symptoms of COVID-19, especially following an exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.”

Respecting travel restrictions is still crucial, Dr. Walensky said, given past surges and variants that have emerged after periods of increased travel.

"We would like to give the opportunity for vaccinated grandparents to visit children and grandchildren who are healthy and local,” Dr. Walensky said.

But, she said, “It’s important to realize as we’re working through this that over 90% of the population is not yet vaccinated.”

For now, there are not enough data on transmission rates from those who are vaccinated to the rest of the public. However, Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a briefing last month that preliminary data are “pointing in a very favorable direction.”

Studies from Spain and Israel published last month showed the amount of viral load – or the amount of the COVID-19 virus in someone’s body – is significantly lower if someone gets infected after they’ve been vaccinated, compared with people who get infected and didn’t have the vaccine. Lower viral load means much lower chances of passing the virus to someone else, Dr. Fauci said.

“The science of COVID-19 is complex,” Dr. Walensky said, “and our understanding of it continues to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

People who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 can safely gather unmasked and inside with nonvulnerable people who are not yet immunized, according to long-awaited guidance released by the CDC.

“Today’s action represents an important first step. It is not our final destination,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said March 8 at a White House briefing. “As more people get vaccinated, levels of COVID-19 infection decline in communities, and as our understanding of COVID immunity improves, we look forward to updating these recommendations to the public.”

According to the new guidance, people who are at least 2 weeks out from their last dose can:

- Visit with other fully vaccinated people indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing.

- Visit with unvaccinated people from a single household who are at low risk for severe COVID-19 disease indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

- Avoid quarantine and testing following exposure to someone if they remain asymptomatic.

However, there are still restrictions that will remain until further data are collected. Those who are fully vaccinated must still:

- Wear masks and physically distance in public settings and around people at high risk for severe disease.

- Wear masks and physically distance when visiting unvaccinated people from more than one household.

- Avoid medium- and large-sized gatherings.

- Avoid travel.

People considered at high risk for severe disease include older adults and those with cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, Down syndrome, heart disease, heart failure, a weakened immune system, obesity, sickle cell disease, and type 2 diabetes. The category also includes pregnant women and smokers.

“In public spaces, fully vaccinated people should continue to follow guidance to protect themselves and others, including wearing a well-fitted mask, physical distancing (at least 6 feet), avoiding crowds, avoiding poorly ventilated spaces, covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands often, and following any applicable workplace or school guidance,” the guidance says. “Fully vaccinated people should still watch for symptoms of COVID-19, especially following an exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.”

Respecting travel restrictions is still crucial, Dr. Walensky said, given past surges and variants that have emerged after periods of increased travel.

"We would like to give the opportunity for vaccinated grandparents to visit children and grandchildren who are healthy and local,” Dr. Walensky said.

But, she said, “It’s important to realize as we’re working through this that over 90% of the population is not yet vaccinated.”

For now, there are not enough data on transmission rates from those who are vaccinated to the rest of the public. However, Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a briefing last month that preliminary data are “pointing in a very favorable direction.”

Studies from Spain and Israel published last month showed the amount of viral load – or the amount of the COVID-19 virus in someone’s body – is significantly lower if someone gets infected after they’ve been vaccinated, compared with people who get infected and didn’t have the vaccine. Lower viral load means much lower chances of passing the virus to someone else, Dr. Fauci said.

“The science of COVID-19 is complex,” Dr. Walensky said, “and our understanding of it continues to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

People who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 can safely gather unmasked and inside with nonvulnerable people who are not yet immunized, according to long-awaited guidance released by the CDC.

“Today’s action represents an important first step. It is not our final destination,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said March 8 at a White House briefing. “As more people get vaccinated, levels of COVID-19 infection decline in communities, and as our understanding of COVID immunity improves, we look forward to updating these recommendations to the public.”

According to the new guidance, people who are at least 2 weeks out from their last dose can:

- Visit with other fully vaccinated people indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing.

- Visit with unvaccinated people from a single household who are at low risk for severe COVID-19 disease indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

- Avoid quarantine and testing following exposure to someone if they remain asymptomatic.

However, there are still restrictions that will remain until further data are collected. Those who are fully vaccinated must still:

- Wear masks and physically distance in public settings and around people at high risk for severe disease.

- Wear masks and physically distance when visiting unvaccinated people from more than one household.

- Avoid medium- and large-sized gatherings.

- Avoid travel.

People considered at high risk for severe disease include older adults and those with cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, Down syndrome, heart disease, heart failure, a weakened immune system, obesity, sickle cell disease, and type 2 diabetes. The category also includes pregnant women and smokers.

“In public spaces, fully vaccinated people should continue to follow guidance to protect themselves and others, including wearing a well-fitted mask, physical distancing (at least 6 feet), avoiding crowds, avoiding poorly ventilated spaces, covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands often, and following any applicable workplace or school guidance,” the guidance says. “Fully vaccinated people should still watch for symptoms of COVID-19, especially following an exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.”

Respecting travel restrictions is still crucial, Dr. Walensky said, given past surges and variants that have emerged after periods of increased travel.

"We would like to give the opportunity for vaccinated grandparents to visit children and grandchildren who are healthy and local,” Dr. Walensky said.

But, she said, “It’s important to realize as we’re working through this that over 90% of the population is not yet vaccinated.”

For now, there are not enough data on transmission rates from those who are vaccinated to the rest of the public. However, Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a briefing last month that preliminary data are “pointing in a very favorable direction.”

Studies from Spain and Israel published last month showed the amount of viral load – or the amount of the COVID-19 virus in someone’s body – is significantly lower if someone gets infected after they’ve been vaccinated, compared with people who get infected and didn’t have the vaccine. Lower viral load means much lower chances of passing the virus to someone else, Dr. Fauci said.

“The science of COVID-19 is complex,” Dr. Walensky said, “and our understanding of it continues to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Asthma-COPD overlap linked to occupational pollutants

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

FROM AAAAI 2021

How to make resident mental health care stigma free

Sarah Sofka, MD, FACP, noticed a pattern. As program director for the internal medicine (IM) residency at West Virginia University, Morgantown, she was informed when residents were sent to counseling because they were affected by burnout, depression, or anxiety. When trainees returned from these visits, many told her the same thing: They wished they had sought help sooner.

IM residents and their families had access to free counseling at WVU, but few used the resource, says Dr. Sofka. “So, we thought, let’s just schedule all of our residents for a therapy visit so they can go and see what it’s like,” she said. “This will hopefully decrease the stigma for seeking mental health care. If everybody’s going, it’s not a big deal.”

In July 2015, Dr. Sofka and her colleagues launched a universal well-being assessment program for the IM residents at WVU. The program leaders automatically scheduled first- and second-year residents for a visit to the faculty staff assistance program counselors. The visits were not mandatory, and residents could choose not to go; but if they did go, they received the entire day of their visit off from work.

Five and a half years after launching their program, Dr. Sofka and her colleagues conducted one of the first studies of the efficacy of an opt-out approach for resident mental wellness. They found that , suggesting that residents were seeking help proactively after having to at least consider it.

Opt-out counseling is a recent concept in residency programs – one that’s attracting interest from training programs across the country. Brown University, Providence, R.I.; the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and the University of California, San Francisco have at least one residency program that uses the approach.

Lisa Meeks, PhD, an assistant professor of family medicine at Michigan Medicine, in Ann Arbor, and other experts also believe opt-out counseling could decrease stigma and help normalize seeking care for mental health problems in the medical community while lowering the barriers for trainees who need help.

No time, no access, plenty of stigma

Burnout and mental health are known to be major concerns for health care workers, especially trainees. College graduates starting medical education have lower rates of burnout and depression, compared with demographically matched peers; however, once they’ve started training, medical students, residents, and fellows are more likely to be burned out and exhibit symptoms of depression. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is further fraying the well-being of overworked and traumatized health care professionals, and experts predict a mental health crisis will follow the viral crisis.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recently mandated that programs offer wellness services to trainees. Yet this doesn’t mean they are always used; well-known barriers stand between residents, medical students, and physicians and their receiving effective mental health treatment.

Two of the most obvious are access and time, given the grueling and often inflexible schedules of most trainees, says Jessica Gold, MD, a psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis, who specializes in treating medical professionals. Dr. Gold also points out that, to be done correctly, these programs require institutional support and investment – resources that aren’t always adequate.

“A lack of transparency and clear messaging around what is available, who provides the services, and how to access these services can be a major barrier,” says Erene Stergiopoulos, MD, a second-year psychiatry resident at the University of Toronto. In addition, there can be considerable lag between when a resident realizes they need help and when they manage to find a provider and schedule an appointment, says Dr. Meeks.

Even when these logistical barriers are overcome, trainees and physicians have to contend with the persistent stigma associated with mental health treatment in the culture of medicine, says Dr. Gold. A recent survey by the American College of Emergency Physicians found that 73% of surveyed physicians feel there is stigma in their workplace about seeking mental health treatment. Many state medical licensing boards still require physicians to disclose mental health treatment, which discourages many trainees and providers from seeking proactive care, says Mary Moffit, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and director of the resident and faculty wellness program at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

How the opt-out approach works

“The idea is by making it opt-out, you really normalize it,” says Maneesh Batra, MD, MPH, associate director of the University of Washington, Seattle, Children’s Hospital residency program. Similar approaches have proven effective at shaping human behavior in other health care settings, including boosting testing rates for HIV and increasing immunization rates for childhood vaccines, Dr. Batra says.

In general, opt-out programs acknowledge that people are busy and won’t take that extra step or click that extra button if they don’t have to, says Oana Tomescu, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical medicine and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

In 2018, Dr. Sofka and her colleagues at WVU conducted a survey that showed that a majority of residents thought favorably of their opt-out program and said they would return to counseling for follow-up care. In their most recent study, published in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education in 2021, Dr. Sofka and her colleagues found that residents did just that – only 8 of 239 opted out of universally scheduled visits. Resident-initiated visits increased significantly from zero during the 2014-2015 academic year to 23 in 2018-2019. Between those periods, program-mandated visits decreased significantly from 12 to 3.

The initiative has succeeded in creating a culture of openness and caring at WVU, says 2nd-year internal medicine resident Nistha Modi, MD. “It sets the tone for the program – we talk about mental health openly,” says Dr. Modi.

Crucially, the counselors work out of a different building than the hospital where Dr. Modi and her fellow residents work and use a separate electronic medical record system to protect resident privacy. This is hugely important for medical trainees, note Dr. Tomescu, Dr. Gold, and many other experts. The therapists understand residency and medical education, and there is no limit to the number of visits a resident or fellow can make with the program counselors, says Dr. Modi.

Opt-out programs offer a counterbalance to many negative tendencies in residency, says Dr. Meeks. “We’ve normalized so many things that are not healthy and productive. ... We need to counterbalance that with normalizing help seeking. And it’s really difficult to normalize something that’s not part of a system.”

Costs, concerns, and systematic support

Providing unlimited, free counseling for trainees can be very beneficial, but it requires adequate funding and personnel resources. Offering unlimited access means that an institution has to follow through in making this degree of care available while also ensuring that the system doesn’t get overwhelmed or is unable to accommodate very sick individuals, says Dr. Gold.

Another concern that experts like Dr. Batra, Dr. Moffit, and Dr. Gold share is that residents who go to their scheduled appointments may not completely buy into the experience because it wasn’t their idea in the first place. Participation alone doesn’t necessarily indicate full acceptance. Program personnel don’t intend for these appointments to be thought of as mandatory, yet residents may still experience them that way. Several leading resident well-being programs instead emphasize outreach to trainees, institutional support, and accessible mental health resources that are – and feel – entirely voluntary.

“If I tell someone that they have to do something, it’s very different than if they arrive at that conclusion for themselves,” says Dr. Batra. “That’s how life works.”