User login

Resident debt is ruining medicine

Most physicians accumulate near $300,000 in debt by the time they finish residency and go to work. This debt is crushing, and it is having negative effects.

College and medical school tuition has soared in the last 20 years, keeping pace with federal loan availability. There is no clear relationship with increased quality of the educational experience or with increased knowledge of the students. Colleges are part of the problem, but, in my opinion, the medical schools are even more egregious. After all, how much does it cost to rent a lecture hall for 2 years and provide some lecturers?

I will never forget when I complained about the increasing expense of medical school to a dean once. He explained that all of the faculty’s salary is considered an expense to the medical school, and that students are only paying a fraction of the true cost.

I must object! If a professor makes a guest appearance for an afternoon or two, the medical students are expected to pay him for a year of work?

I will never forget the goofy physiology professor who gave us two afternoons of demonstrations and lectures. He hooked live frogs to electrodes and made waves on a monitor. It was interesting, but his salary is $200,000 a year. Was it worth $2,000 a student (a class of 100 medical students) to watch him make frogs twitch two afternoons? I think not.

Caribbean medical schools charge about the same as those in North America and make a large profit. Medical students have become a “profit center.” This is occurring in an age when medical students write and share much of their own educational content in an interactive environment. This cannot be sustained.

For the last 2 years of medical school, the students are turned loose on the hospital wards and become slaves. This is called running scut, and it includes running specimens to the lab, wheeling patients to x-ray, drawing blood, fetching lab results, doing much chart work (completing the chart is the most important thing), and learning a lot in spite of the grunt work. The older physicians do teach on rounds, and there is always a resident physician around.

Again, these practicing physicians (they bill for their services) would be there anyway for the residents, and if there were not residents, would have to be there for their patients. The medical students cannot possibly add much additional cost, but these attending physicians and residents salaries are included in the educational cost justification.

The debt introduces a toxic calculus to specialty selection. Residencies are chosen for their fiscal attractiveness, which is not a correct or sustaining reason in a long hard career. Also, it may become economically impossible to practice in a lower-paying specialty.

Let me tell you about Razor Rick, a college student I mentored for several years. I hire these kids in their college summers and breaks to do not much but make a little money, and in exchange they let me pontificate and smile at me. Well, Rick got through med school and then dropped out of his primary care residency, owing several hundred thousand dollars. I was stunned when his parents called me, and I insisted he come in to talk to me.

He patiently explained that his board scores were passing but not good enough to get into to a well-paying specialty. He logically explained that he would have a better life, and have a better return on his investment, if he simply went into pharma with his expensive degree.

I helped him find some interviews.

Some criticize this generation of doctors for not being engaged, for not joining organized medicine, and for avoiding the glorious heart of difficult medicine. I don’t blame them for being distracted. They have, on average, 300,000 good reasons to be more self-concerned.

Dermatology News is proud to introduce the inaugural column of Cold Iron Truth by Dr. Brett Coldiron. Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of over 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Most physicians accumulate near $300,000 in debt by the time they finish residency and go to work. This debt is crushing, and it is having negative effects.

College and medical school tuition has soared in the last 20 years, keeping pace with federal loan availability. There is no clear relationship with increased quality of the educational experience or with increased knowledge of the students. Colleges are part of the problem, but, in my opinion, the medical schools are even more egregious. After all, how much does it cost to rent a lecture hall for 2 years and provide some lecturers?

I will never forget when I complained about the increasing expense of medical school to a dean once. He explained that all of the faculty’s salary is considered an expense to the medical school, and that students are only paying a fraction of the true cost.

I must object! If a professor makes a guest appearance for an afternoon or two, the medical students are expected to pay him for a year of work?

I will never forget the goofy physiology professor who gave us two afternoons of demonstrations and lectures. He hooked live frogs to electrodes and made waves on a monitor. It was interesting, but his salary is $200,000 a year. Was it worth $2,000 a student (a class of 100 medical students) to watch him make frogs twitch two afternoons? I think not.

Caribbean medical schools charge about the same as those in North America and make a large profit. Medical students have become a “profit center.” This is occurring in an age when medical students write and share much of their own educational content in an interactive environment. This cannot be sustained.

For the last 2 years of medical school, the students are turned loose on the hospital wards and become slaves. This is called running scut, and it includes running specimens to the lab, wheeling patients to x-ray, drawing blood, fetching lab results, doing much chart work (completing the chart is the most important thing), and learning a lot in spite of the grunt work. The older physicians do teach on rounds, and there is always a resident physician around.

Again, these practicing physicians (they bill for their services) would be there anyway for the residents, and if there were not residents, would have to be there for their patients. The medical students cannot possibly add much additional cost, but these attending physicians and residents salaries are included in the educational cost justification.

The debt introduces a toxic calculus to specialty selection. Residencies are chosen for their fiscal attractiveness, which is not a correct or sustaining reason in a long hard career. Also, it may become economically impossible to practice in a lower-paying specialty.

Let me tell you about Razor Rick, a college student I mentored for several years. I hire these kids in their college summers and breaks to do not much but make a little money, and in exchange they let me pontificate and smile at me. Well, Rick got through med school and then dropped out of his primary care residency, owing several hundred thousand dollars. I was stunned when his parents called me, and I insisted he come in to talk to me.

He patiently explained that his board scores were passing but not good enough to get into to a well-paying specialty. He logically explained that he would have a better life, and have a better return on his investment, if he simply went into pharma with his expensive degree.

I helped him find some interviews.

Some criticize this generation of doctors for not being engaged, for not joining organized medicine, and for avoiding the glorious heart of difficult medicine. I don’t blame them for being distracted. They have, on average, 300,000 good reasons to be more self-concerned.

Dermatology News is proud to introduce the inaugural column of Cold Iron Truth by Dr. Brett Coldiron. Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of over 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Most physicians accumulate near $300,000 in debt by the time they finish residency and go to work. This debt is crushing, and it is having negative effects.

College and medical school tuition has soared in the last 20 years, keeping pace with federal loan availability. There is no clear relationship with increased quality of the educational experience or with increased knowledge of the students. Colleges are part of the problem, but, in my opinion, the medical schools are even more egregious. After all, how much does it cost to rent a lecture hall for 2 years and provide some lecturers?

I will never forget when I complained about the increasing expense of medical school to a dean once. He explained that all of the faculty’s salary is considered an expense to the medical school, and that students are only paying a fraction of the true cost.

I must object! If a professor makes a guest appearance for an afternoon or two, the medical students are expected to pay him for a year of work?

I will never forget the goofy physiology professor who gave us two afternoons of demonstrations and lectures. He hooked live frogs to electrodes and made waves on a monitor. It was interesting, but his salary is $200,000 a year. Was it worth $2,000 a student (a class of 100 medical students) to watch him make frogs twitch two afternoons? I think not.

Caribbean medical schools charge about the same as those in North America and make a large profit. Medical students have become a “profit center.” This is occurring in an age when medical students write and share much of their own educational content in an interactive environment. This cannot be sustained.

For the last 2 years of medical school, the students are turned loose on the hospital wards and become slaves. This is called running scut, and it includes running specimens to the lab, wheeling patients to x-ray, drawing blood, fetching lab results, doing much chart work (completing the chart is the most important thing), and learning a lot in spite of the grunt work. The older physicians do teach on rounds, and there is always a resident physician around.

Again, these practicing physicians (they bill for their services) would be there anyway for the residents, and if there were not residents, would have to be there for their patients. The medical students cannot possibly add much additional cost, but these attending physicians and residents salaries are included in the educational cost justification.

The debt introduces a toxic calculus to specialty selection. Residencies are chosen for their fiscal attractiveness, which is not a correct or sustaining reason in a long hard career. Also, it may become economically impossible to practice in a lower-paying specialty.

Let me tell you about Razor Rick, a college student I mentored for several years. I hire these kids in their college summers and breaks to do not much but make a little money, and in exchange they let me pontificate and smile at me. Well, Rick got through med school and then dropped out of his primary care residency, owing several hundred thousand dollars. I was stunned when his parents called me, and I insisted he come in to talk to me.

He patiently explained that his board scores were passing but not good enough to get into to a well-paying specialty. He logically explained that he would have a better life, and have a better return on his investment, if he simply went into pharma with his expensive degree.

I helped him find some interviews.

Some criticize this generation of doctors for not being engaged, for not joining organized medicine, and for avoiding the glorious heart of difficult medicine. I don’t blame them for being distracted. They have, on average, 300,000 good reasons to be more self-concerned.

Dermatology News is proud to introduce the inaugural column of Cold Iron Truth by Dr. Brett Coldiron. Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of over 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Familial factors linked to child’s risk of blood cancer

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.” ![]()

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.” ![]()

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.” ![]()

New method to assess cancer risk from pollutants

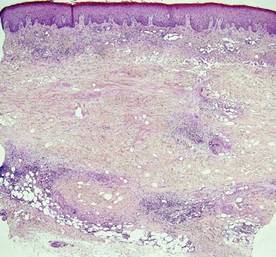

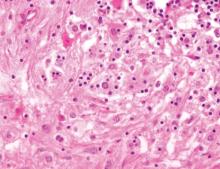

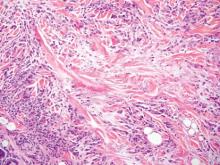

Photo by Tiffany Dawn Nicholson

Scientists say they have developed a faster, more accurate method to assess cancer risk from certain common environmental pollutants.

The group found they could analyze the immediate genetic responses of the skin cells of exposed mice and apply statistical approaches to determine whether or not those cells would eventually become cancerous.

The study focused on a class of pollutants known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) that commonly occur in the environment as mixtures such as diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke.

“After only 12 hours, we could predict the ability of certain PAH mixtures to cause cancer, rather than waiting 25 weeks for tumors to develop,” said study author Susan Tilton, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

For at least some PAH mixtures, the new method is not only quicker but produces more accurate cancer-risk assessments than are currently possible, she added.

Dr Tilton and her colleagues described the method in Toxicological Sciences.

“Our work was intended as a proof of concept,” Dr Tilton noted. “The method needs to be tested with a larger group of chemicals and mixtures. But we now have a model that we can use to develop larger-scale screening tests with human cells in a laboratory dish.”

The researchers believe the model will be particularly useful for screening PAHs, a large class of pollutants that result from combustion of organic matter and fossil fuels. PAHs are widespread contaminants of air, water, and soil. There are hundreds of different kinds, and some are known carcinogens, but many have not been tested.

Humans are primarily exposed to PAHs in the environment as mixtures, which makes it harder to assess their cancer risk. The standard calculation, Dr Tilton said, is to identify the risk of each element in the mix—if it’s known—and add them together.

But this method doesn’t work with most PAH mixes. It assumes the risk for each component is known, as well as which components are in a given mix. Often, that information is not available.

For this study, Dr Tilton and her colleagues examined 3 PAH mixtures that are common in the environment—coal tar, diesel exhaust, and cigarette smoke—and various mixtures of them.

The group found that each substance touched off a rapid and distinctive cascade of biological and metabolic changes in the skin cells of a mouse. The response amounted to a unique “fingerprint” of the genetic changes that occur as cells reacted to exposure to each chemical.

By matching patterns of genetic changes known to occur as cells become cancerous, the researchers found that some of the cellular responses were early indicators of developing cancers.

They also found that the standard method to calculate carcinogenic material underestimated the cancer risk of some mixtures and overestimated the combined risk of others.

“Our study is a first step in moving away from risk assessments based on individual components of these PAH mixtures and developing more accurate methods that look at the mixture as a whole,” Dr Tilton said. “We’re hoping to bring the methodology to the point where we no longer need to use tumors as our endpoint.” ![]()

Photo by Tiffany Dawn Nicholson

Scientists say they have developed a faster, more accurate method to assess cancer risk from certain common environmental pollutants.

The group found they could analyze the immediate genetic responses of the skin cells of exposed mice and apply statistical approaches to determine whether or not those cells would eventually become cancerous.

The study focused on a class of pollutants known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) that commonly occur in the environment as mixtures such as diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke.

“After only 12 hours, we could predict the ability of certain PAH mixtures to cause cancer, rather than waiting 25 weeks for tumors to develop,” said study author Susan Tilton, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

For at least some PAH mixtures, the new method is not only quicker but produces more accurate cancer-risk assessments than are currently possible, she added.

Dr Tilton and her colleagues described the method in Toxicological Sciences.

“Our work was intended as a proof of concept,” Dr Tilton noted. “The method needs to be tested with a larger group of chemicals and mixtures. But we now have a model that we can use to develop larger-scale screening tests with human cells in a laboratory dish.”

The researchers believe the model will be particularly useful for screening PAHs, a large class of pollutants that result from combustion of organic matter and fossil fuels. PAHs are widespread contaminants of air, water, and soil. There are hundreds of different kinds, and some are known carcinogens, but many have not been tested.

Humans are primarily exposed to PAHs in the environment as mixtures, which makes it harder to assess their cancer risk. The standard calculation, Dr Tilton said, is to identify the risk of each element in the mix—if it’s known—and add them together.

But this method doesn’t work with most PAH mixes. It assumes the risk for each component is known, as well as which components are in a given mix. Often, that information is not available.

For this study, Dr Tilton and her colleagues examined 3 PAH mixtures that are common in the environment—coal tar, diesel exhaust, and cigarette smoke—and various mixtures of them.

The group found that each substance touched off a rapid and distinctive cascade of biological and metabolic changes in the skin cells of a mouse. The response amounted to a unique “fingerprint” of the genetic changes that occur as cells reacted to exposure to each chemical.

By matching patterns of genetic changes known to occur as cells become cancerous, the researchers found that some of the cellular responses were early indicators of developing cancers.

They also found that the standard method to calculate carcinogenic material underestimated the cancer risk of some mixtures and overestimated the combined risk of others.

“Our study is a first step in moving away from risk assessments based on individual components of these PAH mixtures and developing more accurate methods that look at the mixture as a whole,” Dr Tilton said. “We’re hoping to bring the methodology to the point where we no longer need to use tumors as our endpoint.” ![]()

Photo by Tiffany Dawn Nicholson

Scientists say they have developed a faster, more accurate method to assess cancer risk from certain common environmental pollutants.

The group found they could analyze the immediate genetic responses of the skin cells of exposed mice and apply statistical approaches to determine whether or not those cells would eventually become cancerous.

The study focused on a class of pollutants known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) that commonly occur in the environment as mixtures such as diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke.

“After only 12 hours, we could predict the ability of certain PAH mixtures to cause cancer, rather than waiting 25 weeks for tumors to develop,” said study author Susan Tilton, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

For at least some PAH mixtures, the new method is not only quicker but produces more accurate cancer-risk assessments than are currently possible, she added.

Dr Tilton and her colleagues described the method in Toxicological Sciences.

“Our work was intended as a proof of concept,” Dr Tilton noted. “The method needs to be tested with a larger group of chemicals and mixtures. But we now have a model that we can use to develop larger-scale screening tests with human cells in a laboratory dish.”

The researchers believe the model will be particularly useful for screening PAHs, a large class of pollutants that result from combustion of organic matter and fossil fuels. PAHs are widespread contaminants of air, water, and soil. There are hundreds of different kinds, and some are known carcinogens, but many have not been tested.

Humans are primarily exposed to PAHs in the environment as mixtures, which makes it harder to assess their cancer risk. The standard calculation, Dr Tilton said, is to identify the risk of each element in the mix—if it’s known—and add them together.

But this method doesn’t work with most PAH mixes. It assumes the risk for each component is known, as well as which components are in a given mix. Often, that information is not available.

For this study, Dr Tilton and her colleagues examined 3 PAH mixtures that are common in the environment—coal tar, diesel exhaust, and cigarette smoke—and various mixtures of them.

The group found that each substance touched off a rapid and distinctive cascade of biological and metabolic changes in the skin cells of a mouse. The response amounted to a unique “fingerprint” of the genetic changes that occur as cells reacted to exposure to each chemical.

By matching patterns of genetic changes known to occur as cells become cancerous, the researchers found that some of the cellular responses were early indicators of developing cancers.

They also found that the standard method to calculate carcinogenic material underestimated the cancer risk of some mixtures and overestimated the combined risk of others.

“Our study is a first step in moving away from risk assessments based on individual components of these PAH mixtures and developing more accurate methods that look at the mixture as a whole,” Dr Tilton said. “We’re hoping to bring the methodology to the point where we no longer need to use tumors as our endpoint.” ![]()

Microbubbles can treat, track thrombosis

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN FRANCISCO—Microbubbles can be used to simultaneously treat and monitor thrombosis, according to preclinical research presented at the ATVB/PVD 2015 Scientific Sessions.

The microbubbles double as agents for contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging and targeted drug-delivery vehicles.

Experiments in mice showed that the microbubbles could deliver treatment directly to a blood clot, noticeably reducing its size without causing abnormal bleeding.

Karlheinz Peter, MD, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 36.

He and his colleagues combined the thrombolytic agent urokinase with an activated-platelet-specific, single-chain antibody and placed the duo on the surface of microbubbles.

The researchers then tracked the microbubbles’ progress in a mouse model of carotid artery thrombosis induced by ferric-chloride.

The team monitored clot size in these mice with ultrasound imaging and measured bleeding time after experimental injury, while comparing 4 treatment groups:

- Microbubbles coated with both the targeting antibody and urokinase

- Targeted microbubbles and a high dose of urokinase administered separately

- Targeted microbubbles and a low dose of urokinase administered separately

- A control group with targeted microbubbles and no urokinase.

Microbubbles with urokinase on their surface significantly reduced clot size after 45 minutes, but microbubbles without urokinase did not. The mean percentage change in thrombus size from baseline was 97.16 ± 4.3 and 37.09 ± 5.6, respectively (P<0.001).

Urokinase administered alone could only match the efficacy of the treatment-loaded microbubbles if the drug was administered at a high dose. However, that significantly prolonged bleeding time from baseline—1079.25 ± 260.7 seconds vs 79.25 ± 6.5 seconds (P<0.001)—whereas, treatment with microbubbles did not.

While this research is in the early stages, the researchers believe the technology could help patients who develop venous thromboembolism and related conditions, such as heart attack and stroke. The team also believes the technology could have a major impact on treatment of patients in the emergency department. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN FRANCISCO—Microbubbles can be used to simultaneously treat and monitor thrombosis, according to preclinical research presented at the ATVB/PVD 2015 Scientific Sessions.

The microbubbles double as agents for contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging and targeted drug-delivery vehicles.

Experiments in mice showed that the microbubbles could deliver treatment directly to a blood clot, noticeably reducing its size without causing abnormal bleeding.

Karlheinz Peter, MD, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 36.

He and his colleagues combined the thrombolytic agent urokinase with an activated-platelet-specific, single-chain antibody and placed the duo on the surface of microbubbles.

The researchers then tracked the microbubbles’ progress in a mouse model of carotid artery thrombosis induced by ferric-chloride.

The team monitored clot size in these mice with ultrasound imaging and measured bleeding time after experimental injury, while comparing 4 treatment groups:

- Microbubbles coated with both the targeting antibody and urokinase

- Targeted microbubbles and a high dose of urokinase administered separately

- Targeted microbubbles and a low dose of urokinase administered separately

- A control group with targeted microbubbles and no urokinase.

Microbubbles with urokinase on their surface significantly reduced clot size after 45 minutes, but microbubbles without urokinase did not. The mean percentage change in thrombus size from baseline was 97.16 ± 4.3 and 37.09 ± 5.6, respectively (P<0.001).

Urokinase administered alone could only match the efficacy of the treatment-loaded microbubbles if the drug was administered at a high dose. However, that significantly prolonged bleeding time from baseline—1079.25 ± 260.7 seconds vs 79.25 ± 6.5 seconds (P<0.001)—whereas, treatment with microbubbles did not.

While this research is in the early stages, the researchers believe the technology could help patients who develop venous thromboembolism and related conditions, such as heart attack and stroke. The team also believes the technology could have a major impact on treatment of patients in the emergency department. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN FRANCISCO—Microbubbles can be used to simultaneously treat and monitor thrombosis, according to preclinical research presented at the ATVB/PVD 2015 Scientific Sessions.

The microbubbles double as agents for contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging and targeted drug-delivery vehicles.

Experiments in mice showed that the microbubbles could deliver treatment directly to a blood clot, noticeably reducing its size without causing abnormal bleeding.

Karlheinz Peter, MD, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 36.

He and his colleagues combined the thrombolytic agent urokinase with an activated-platelet-specific, single-chain antibody and placed the duo on the surface of microbubbles.

The researchers then tracked the microbubbles’ progress in a mouse model of carotid artery thrombosis induced by ferric-chloride.

The team monitored clot size in these mice with ultrasound imaging and measured bleeding time after experimental injury, while comparing 4 treatment groups:

- Microbubbles coated with both the targeting antibody and urokinase

- Targeted microbubbles and a high dose of urokinase administered separately

- Targeted microbubbles and a low dose of urokinase administered separately

- A control group with targeted microbubbles and no urokinase.

Microbubbles with urokinase on their surface significantly reduced clot size after 45 minutes, but microbubbles without urokinase did not. The mean percentage change in thrombus size from baseline was 97.16 ± 4.3 and 37.09 ± 5.6, respectively (P<0.001).

Urokinase administered alone could only match the efficacy of the treatment-loaded microbubbles if the drug was administered at a high dose. However, that significantly prolonged bleeding time from baseline—1079.25 ± 260.7 seconds vs 79.25 ± 6.5 seconds (P<0.001)—whereas, treatment with microbubbles did not.

While this research is in the early stages, the researchers believe the technology could help patients who develop venous thromboembolism and related conditions, such as heart attack and stroke. The team also believes the technology could have a major impact on treatment of patients in the emergency department. ![]()

FDA issues draft guidance on blood donation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance recommending changes to current policies aimed at reducing the risk of HIV transmission via blood products.

Among the recommended changes is a proposal to alter the policy that prevents men who have sex with men (MSM) from donating blood.

The FDA’s draft guidance is recommending that MSM be allowed to donate blood if they have abstained from sexual contact for 1 year.

If this draft guidance is implemented, the US would follow other countries that have lifted the lifetime ban on MSM blood donors in recent years, such as the UK, Canada, and South Africa.

Human rights groups—such as the Human Rights Campaign, the US’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender civil rights organization—have said the FDA’s proposed policy change is still discriminatory.

“While the new policy is a step in the right direction toward an ideal policy that reflects the best scientific research, it still falls far short of a fully acceptable solution because it continues to stigmatize gay and bisexual men,” said Human Rights Campaign Government Affairs Director David Stacy.

“This policy prevents men from donating life-saving blood based solely on their sexual orientation rather than actual risk to the blood supply. It simply cannot be justified in light of current scientific research and updated blood screening technology.”

On the other side of the debate, blood banking groups—including the American Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers, and the American Association of Blood Banks—have voiced their support of a 1-year deferral period for MSM, as data have suggested this group has an increased risk of contracting HIV.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MSM are more severely affected by HIV than any other group in the US.

“This change in policy would align the donor deferral period for MSM with criteria for other activities that may pose a similar risk of transfusion-transmissible infections,” the blood banking groups said in a joint statement.

“We believe the current FDA indefinite blood donation deferral for a man who has [had] sex with another man since 1977 is medically and scientifically unwarranted. The blood banking community strongly supports the use of rational, scientifically based deferral periods that are applied fairly and consistently among blood donors who engage in similar-risk activities.”

The FDA’s draft guidance seems to reflect that idea, as the 1-year deferral period does not only pertain to MSM. It also pertains to individuals who have a history of receiving a transfusion of whole blood or blood components, individuals with a history of syphilis or gonorrhea, and individuals who have had a tattoo or piercing in the last year, among others.

The draft guidance also includes recommendations pertaining to donor education material and donor history questionnaires, donor requalification, product retrieval and quarantine, testing requirements, and other issues.

The full guidance, available here, is open for comment. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance recommending changes to current policies aimed at reducing the risk of HIV transmission via blood products.

Among the recommended changes is a proposal to alter the policy that prevents men who have sex with men (MSM) from donating blood.

The FDA’s draft guidance is recommending that MSM be allowed to donate blood if they have abstained from sexual contact for 1 year.

If this draft guidance is implemented, the US would follow other countries that have lifted the lifetime ban on MSM blood donors in recent years, such as the UK, Canada, and South Africa.

Human rights groups—such as the Human Rights Campaign, the US’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender civil rights organization—have said the FDA’s proposed policy change is still discriminatory.

“While the new policy is a step in the right direction toward an ideal policy that reflects the best scientific research, it still falls far short of a fully acceptable solution because it continues to stigmatize gay and bisexual men,” said Human Rights Campaign Government Affairs Director David Stacy.

“This policy prevents men from donating life-saving blood based solely on their sexual orientation rather than actual risk to the blood supply. It simply cannot be justified in light of current scientific research and updated blood screening technology.”

On the other side of the debate, blood banking groups—including the American Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers, and the American Association of Blood Banks—have voiced their support of a 1-year deferral period for MSM, as data have suggested this group has an increased risk of contracting HIV.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MSM are more severely affected by HIV than any other group in the US.

“This change in policy would align the donor deferral period for MSM with criteria for other activities that may pose a similar risk of transfusion-transmissible infections,” the blood banking groups said in a joint statement.

“We believe the current FDA indefinite blood donation deferral for a man who has [had] sex with another man since 1977 is medically and scientifically unwarranted. The blood banking community strongly supports the use of rational, scientifically based deferral periods that are applied fairly and consistently among blood donors who engage in similar-risk activities.”

The FDA’s draft guidance seems to reflect that idea, as the 1-year deferral period does not only pertain to MSM. It also pertains to individuals who have a history of receiving a transfusion of whole blood or blood components, individuals with a history of syphilis or gonorrhea, and individuals who have had a tattoo or piercing in the last year, among others.

The draft guidance also includes recommendations pertaining to donor education material and donor history questionnaires, donor requalification, product retrieval and quarantine, testing requirements, and other issues.

The full guidance, available here, is open for comment. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a draft guidance recommending changes to current policies aimed at reducing the risk of HIV transmission via blood products.

Among the recommended changes is a proposal to alter the policy that prevents men who have sex with men (MSM) from donating blood.

The FDA’s draft guidance is recommending that MSM be allowed to donate blood if they have abstained from sexual contact for 1 year.

If this draft guidance is implemented, the US would follow other countries that have lifted the lifetime ban on MSM blood donors in recent years, such as the UK, Canada, and South Africa.

Human rights groups—such as the Human Rights Campaign, the US’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender civil rights organization—have said the FDA’s proposed policy change is still discriminatory.

“While the new policy is a step in the right direction toward an ideal policy that reflects the best scientific research, it still falls far short of a fully acceptable solution because it continues to stigmatize gay and bisexual men,” said Human Rights Campaign Government Affairs Director David Stacy.

“This policy prevents men from donating life-saving blood based solely on their sexual orientation rather than actual risk to the blood supply. It simply cannot be justified in light of current scientific research and updated blood screening technology.”

On the other side of the debate, blood banking groups—including the American Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers, and the American Association of Blood Banks—have voiced their support of a 1-year deferral period for MSM, as data have suggested this group has an increased risk of contracting HIV.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MSM are more severely affected by HIV than any other group in the US.

“This change in policy would align the donor deferral period for MSM with criteria for other activities that may pose a similar risk of transfusion-transmissible infections,” the blood banking groups said in a joint statement.

“We believe the current FDA indefinite blood donation deferral for a man who has [had] sex with another man since 1977 is medically and scientifically unwarranted. The blood banking community strongly supports the use of rational, scientifically based deferral periods that are applied fairly and consistently among blood donors who engage in similar-risk activities.”

The FDA’s draft guidance seems to reflect that idea, as the 1-year deferral period does not only pertain to MSM. It also pertains to individuals who have a history of receiving a transfusion of whole blood or blood components, individuals with a history of syphilis or gonorrhea, and individuals who have had a tattoo or piercing in the last year, among others.

The draft guidance also includes recommendations pertaining to donor education material and donor history questionnaires, donor requalification, product retrieval and quarantine, testing requirements, and other issues.

The full guidance, available here, is open for comment. ![]()

Lawsuits against skilled nursing facilities

Question: Grandma finally checked into a skilled nursing facility (SNF), a member of a national chain of for-profit SNFs, after her progressive dementia prevented her from performing the basic activities of daily living. Unfortunately, the staffing was inadequate, and there were lapses in attention toward her nutrition, medications, and body hygiene. She even fell from her bed on a couple of occasions. Other residents have registered similar complaints. Which of the following legal recourses is available?

A. A lawsuit against the SNF, alleging neglect and abuse.

B. A class action suit against the SNF and its corporate owners.

C. A lawsuit against the attending physician and/or the medical director.

D. A, B, and C.

E. Only A and B.

Answer: D. According to the Wall Street Journal, more than 1.4 million people live in U.S. nursing homes, 69% of which are run by for-profit entities.1 In contrast to a malpractice complaint, lawsuits against nursing homes and SNFs typically involve allegations of a pattern of neglect and abuse rather than any single incident of negligence. The terms nursing home and SNF are often used interchangeably, but do differ somewhat in that the former deals with non-Medicare regulated custodial care, whereas Medicare regulates and certifies all SNFs, which provide both custodial and medical care. Federal and state statutes, e.g., 42 CFR §483 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines in the State Operations Manual, prescribe the requisite standards. Collectively referred to as the OBRA standards, their violations are frequently at the heart of a plaintiff’s allegations. These may include short staffing, inattention to body hygiene, skin infections, pressure ulcers, improper use of restraints, poor nutrition and hydration, and failure to monitor or supervise, including failure to administer prescription medications and prevention of falls and violent acts from other residents.

In the past 2 decades, nursing homes and SNFs have experienced soaring numbers of lawsuits, with Texas and Florida being especially vulnerable.2 Runaway jury verdicts can result even where the elderly victim has incurred little or no economic loss. Noneconomic losses such as pain and suffering as well as punitive damages explain these huge awards. A recent widely publicized case is illustrative: On Sept. 4, 2009, 87-year-old Dorothy Douglas, an Alzheimer’s patient, was admitted to Heartland Nursing Home in Charleston, W.Va. Still cognitive, she was able to ambulate with an assistive device and was well nourished. However, within 19 days of admission, she became barely responsive, dehydrated, and bedridden, and had fallen numerous times, injuring her head. She died shortly thereafter. Her son sued the owner of Heartland and those responsible for its operations, claiming, among other things, medical and corporate negligence. A jury found in his favor, awarding $11.5 million in compensatory damages and $80 million in punitive damages. On appeal, the West Virginia Supreme Court affirmed in part the trial court’s order, although it reduced the punitive damages from $80 million to $32 million (termed a remittitur).3

There are other sizable verdicts, such as a $29 million lawsuit against a Rocklin, Calif., facility in 2010. Another, possibly the largest on record, was a 2013 Florida jury award of $110 million in compensatory damages and $1.0 billion in punitive damages against Auburndale Oaks Healthcare Center. However, this may not have been the final negotiated amount. Increasingly popular is the use of class action lawsuits, where representative plaintiffs assert claims on behalf of a large class of similarly injured members. Typically, they allege grossly substandard care and understaffing in violation of Medicare and/or other statutory rules. New York’s first nursing home class action suit,4 which dragged on for some 9 years, ended up with a settlement sum of only $950,000 for its 22 class members. The suit alleged, among other things, inedible food, inadequate heat, and squalid conditions. A more recent example: In 2010, a Humboldt County, Calif., jury returned a $677 million verdict (Lavender v. Skilled Healthcare Group Inc.) against one of the nation’s largest nursing home chains for violating California’s Health and Safety Code in its 22 statewide facilities. The case later settled for $62.8 million on behalf of the 32,000 residents.

What about physician liability? Many doctors attend to SNF patients and a number act as medical directors. Liability exists in both roles. The first is governed by the usual tort action of malpractice. The latter is infinitely trickier. Medicare mandates all SNFs to have a medical director, and federal law [42 CFR 483.75 (i)] requires the medical director to be responsible for implementation of resident care policies and the coordination of medical care in the facility. Although their duties are administrative in nature, medical directors are not infrequently named as codefendants in SNF lawsuits. Allegations against the medical director may include negligent supervision of staff, and/or the failure to set standards, policies, and procedures, especially if they have been made aware of citations by auditing agencies. Because a doctor’s professional liability policy typically excludes coverage for such work, it behooves all medical directors to insist on being a named insured in the institution’s general liability policy (to include tail coverage), and to be informed in a timely fashion should there be a relevant change or cancellation of coverage. Their contract should stipulate that the facility would indemnify them for all lawsuits arising out of their work. More and more nursing homes are dropping their insurance to bypass legal exposure, leaving the attending physician and/or medical director at increased risk. To avoid a serious gap in coverage, medical directors should consider purchasing a specific medical director policy.5 Medical directors should also be aware of potential Stark Law violations, such as treating private patients without paying fair rent or receiving compensation in exchange for referrals.

Importantly, elder abuse judgments, as opposed to malpractice awards, may negate restrictions on attorney fees and noneconomic damages such as California’s $250,000 cap. The jury may also levy punitive damages, which are not covered by professional insurance. The plaintiff will need to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, something more than simple or gross negligence such as malice, fraud, oppression, or recklessness.6 Under California’s elder abuse and dependent Adult Civil Protection Act, an appellate court has held that a plaintiff may mount an elder abuse claim directed at physicians and not just facilities with “custodial” duties.7This important issue is currently under appeal before the California Supreme Court.

References

1. The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 3, 2014.

2. Stevenson, DG and DM Studdert, The Rise Of Nursing Home Litigation: Findings From A National Survey Of Attorneys. Health Affairs 2003; 22:219-29.

3. Manor Care Inc. v. Douglas, 763 N.E.2d 73 (W. Va. 2014).

4. Fleming v. Barnwell Nursing Hone and Health Facilities Inc., 309 A.D.2d 1132 (N.Y. App. Div. 2003).

5. See the American Medical Directors Association’s (AMDA) offering at http://locktonmedicalliabilityinsurance.com/amda/.

6. Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23 (1999).

7. Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group Inc., 216 Cal. App. 4th 875 (2013).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. He currently directs The St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Grandma finally checked into a skilled nursing facility (SNF), a member of a national chain of for-profit SNFs, after her progressive dementia prevented her from performing the basic activities of daily living. Unfortunately, the staffing was inadequate, and there were lapses in attention toward her nutrition, medications, and body hygiene. She even fell from her bed on a couple of occasions. Other residents have registered similar complaints. Which of the following legal recourses is available?

A. A lawsuit against the SNF, alleging neglect and abuse.

B. A class action suit against the SNF and its corporate owners.

C. A lawsuit against the attending physician and/or the medical director.

D. A, B, and C.

E. Only A and B.

Answer: D. According to the Wall Street Journal, more than 1.4 million people live in U.S. nursing homes, 69% of which are run by for-profit entities.1 In contrast to a malpractice complaint, lawsuits against nursing homes and SNFs typically involve allegations of a pattern of neglect and abuse rather than any single incident of negligence. The terms nursing home and SNF are often used interchangeably, but do differ somewhat in that the former deals with non-Medicare regulated custodial care, whereas Medicare regulates and certifies all SNFs, which provide both custodial and medical care. Federal and state statutes, e.g., 42 CFR §483 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines in the State Operations Manual, prescribe the requisite standards. Collectively referred to as the OBRA standards, their violations are frequently at the heart of a plaintiff’s allegations. These may include short staffing, inattention to body hygiene, skin infections, pressure ulcers, improper use of restraints, poor nutrition and hydration, and failure to monitor or supervise, including failure to administer prescription medications and prevention of falls and violent acts from other residents.

In the past 2 decades, nursing homes and SNFs have experienced soaring numbers of lawsuits, with Texas and Florida being especially vulnerable.2 Runaway jury verdicts can result even where the elderly victim has incurred little or no economic loss. Noneconomic losses such as pain and suffering as well as punitive damages explain these huge awards. A recent widely publicized case is illustrative: On Sept. 4, 2009, 87-year-old Dorothy Douglas, an Alzheimer’s patient, was admitted to Heartland Nursing Home in Charleston, W.Va. Still cognitive, she was able to ambulate with an assistive device and was well nourished. However, within 19 days of admission, she became barely responsive, dehydrated, and bedridden, and had fallen numerous times, injuring her head. She died shortly thereafter. Her son sued the owner of Heartland and those responsible for its operations, claiming, among other things, medical and corporate negligence. A jury found in his favor, awarding $11.5 million in compensatory damages and $80 million in punitive damages. On appeal, the West Virginia Supreme Court affirmed in part the trial court’s order, although it reduced the punitive damages from $80 million to $32 million (termed a remittitur).3

There are other sizable verdicts, such as a $29 million lawsuit against a Rocklin, Calif., facility in 2010. Another, possibly the largest on record, was a 2013 Florida jury award of $110 million in compensatory damages and $1.0 billion in punitive damages against Auburndale Oaks Healthcare Center. However, this may not have been the final negotiated amount. Increasingly popular is the use of class action lawsuits, where representative plaintiffs assert claims on behalf of a large class of similarly injured members. Typically, they allege grossly substandard care and understaffing in violation of Medicare and/or other statutory rules. New York’s first nursing home class action suit,4 which dragged on for some 9 years, ended up with a settlement sum of only $950,000 for its 22 class members. The suit alleged, among other things, inedible food, inadequate heat, and squalid conditions. A more recent example: In 2010, a Humboldt County, Calif., jury returned a $677 million verdict (Lavender v. Skilled Healthcare Group Inc.) against one of the nation’s largest nursing home chains for violating California’s Health and Safety Code in its 22 statewide facilities. The case later settled for $62.8 million on behalf of the 32,000 residents.

What about physician liability? Many doctors attend to SNF patients and a number act as medical directors. Liability exists in both roles. The first is governed by the usual tort action of malpractice. The latter is infinitely trickier. Medicare mandates all SNFs to have a medical director, and federal law [42 CFR 483.75 (i)] requires the medical director to be responsible for implementation of resident care policies and the coordination of medical care in the facility. Although their duties are administrative in nature, medical directors are not infrequently named as codefendants in SNF lawsuits. Allegations against the medical director may include negligent supervision of staff, and/or the failure to set standards, policies, and procedures, especially if they have been made aware of citations by auditing agencies. Because a doctor’s professional liability policy typically excludes coverage for such work, it behooves all medical directors to insist on being a named insured in the institution’s general liability policy (to include tail coverage), and to be informed in a timely fashion should there be a relevant change or cancellation of coverage. Their contract should stipulate that the facility would indemnify them for all lawsuits arising out of their work. More and more nursing homes are dropping their insurance to bypass legal exposure, leaving the attending physician and/or medical director at increased risk. To avoid a serious gap in coverage, medical directors should consider purchasing a specific medical director policy.5 Medical directors should also be aware of potential Stark Law violations, such as treating private patients without paying fair rent or receiving compensation in exchange for referrals.

Importantly, elder abuse judgments, as opposed to malpractice awards, may negate restrictions on attorney fees and noneconomic damages such as California’s $250,000 cap. The jury may also levy punitive damages, which are not covered by professional insurance. The plaintiff will need to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, something more than simple or gross negligence such as malice, fraud, oppression, or recklessness.6 Under California’s elder abuse and dependent Adult Civil Protection Act, an appellate court has held that a plaintiff may mount an elder abuse claim directed at physicians and not just facilities with “custodial” duties.7This important issue is currently under appeal before the California Supreme Court.

References

1. The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 3, 2014.

2. Stevenson, DG and DM Studdert, The Rise Of Nursing Home Litigation: Findings From A National Survey Of Attorneys. Health Affairs 2003; 22:219-29.

3. Manor Care Inc. v. Douglas, 763 N.E.2d 73 (W. Va. 2014).

4. Fleming v. Barnwell Nursing Hone and Health Facilities Inc., 309 A.D.2d 1132 (N.Y. App. Div. 2003).

5. See the American Medical Directors Association’s (AMDA) offering at http://locktonmedicalliabilityinsurance.com/amda/.

6. Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23 (1999).

7. Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group Inc., 216 Cal. App. 4th 875 (2013).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. He currently directs The St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Grandma finally checked into a skilled nursing facility (SNF), a member of a national chain of for-profit SNFs, after her progressive dementia prevented her from performing the basic activities of daily living. Unfortunately, the staffing was inadequate, and there were lapses in attention toward her nutrition, medications, and body hygiene. She even fell from her bed on a couple of occasions. Other residents have registered similar complaints. Which of the following legal recourses is available?

A. A lawsuit against the SNF, alleging neglect and abuse.

B. A class action suit against the SNF and its corporate owners.

C. A lawsuit against the attending physician and/or the medical director.

D. A, B, and C.

E. Only A and B.

Answer: D. According to the Wall Street Journal, more than 1.4 million people live in U.S. nursing homes, 69% of which are run by for-profit entities.1 In contrast to a malpractice complaint, lawsuits against nursing homes and SNFs typically involve allegations of a pattern of neglect and abuse rather than any single incident of negligence. The terms nursing home and SNF are often used interchangeably, but do differ somewhat in that the former deals with non-Medicare regulated custodial care, whereas Medicare regulates and certifies all SNFs, which provide both custodial and medical care. Federal and state statutes, e.g., 42 CFR §483 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines in the State Operations Manual, prescribe the requisite standards. Collectively referred to as the OBRA standards, their violations are frequently at the heart of a plaintiff’s allegations. These may include short staffing, inattention to body hygiene, skin infections, pressure ulcers, improper use of restraints, poor nutrition and hydration, and failure to monitor or supervise, including failure to administer prescription medications and prevention of falls and violent acts from other residents.

In the past 2 decades, nursing homes and SNFs have experienced soaring numbers of lawsuits, with Texas and Florida being especially vulnerable.2 Runaway jury verdicts can result even where the elderly victim has incurred little or no economic loss. Noneconomic losses such as pain and suffering as well as punitive damages explain these huge awards. A recent widely publicized case is illustrative: On Sept. 4, 2009, 87-year-old Dorothy Douglas, an Alzheimer’s patient, was admitted to Heartland Nursing Home in Charleston, W.Va. Still cognitive, she was able to ambulate with an assistive device and was well nourished. However, within 19 days of admission, she became barely responsive, dehydrated, and bedridden, and had fallen numerous times, injuring her head. She died shortly thereafter. Her son sued the owner of Heartland and those responsible for its operations, claiming, among other things, medical and corporate negligence. A jury found in his favor, awarding $11.5 million in compensatory damages and $80 million in punitive damages. On appeal, the West Virginia Supreme Court affirmed in part the trial court’s order, although it reduced the punitive damages from $80 million to $32 million (termed a remittitur).3

There are other sizable verdicts, such as a $29 million lawsuit against a Rocklin, Calif., facility in 2010. Another, possibly the largest on record, was a 2013 Florida jury award of $110 million in compensatory damages and $1.0 billion in punitive damages against Auburndale Oaks Healthcare Center. However, this may not have been the final negotiated amount. Increasingly popular is the use of class action lawsuits, where representative plaintiffs assert claims on behalf of a large class of similarly injured members. Typically, they allege grossly substandard care and understaffing in violation of Medicare and/or other statutory rules. New York’s first nursing home class action suit,4 which dragged on for some 9 years, ended up with a settlement sum of only $950,000 for its 22 class members. The suit alleged, among other things, inedible food, inadequate heat, and squalid conditions. A more recent example: In 2010, a Humboldt County, Calif., jury returned a $677 million verdict (Lavender v. Skilled Healthcare Group Inc.) against one of the nation’s largest nursing home chains for violating California’s Health and Safety Code in its 22 statewide facilities. The case later settled for $62.8 million on behalf of the 32,000 residents.

What about physician liability? Many doctors attend to SNF patients and a number act as medical directors. Liability exists in both roles. The first is governed by the usual tort action of malpractice. The latter is infinitely trickier. Medicare mandates all SNFs to have a medical director, and federal law [42 CFR 483.75 (i)] requires the medical director to be responsible for implementation of resident care policies and the coordination of medical care in the facility. Although their duties are administrative in nature, medical directors are not infrequently named as codefendants in SNF lawsuits. Allegations against the medical director may include negligent supervision of staff, and/or the failure to set standards, policies, and procedures, especially if they have been made aware of citations by auditing agencies. Because a doctor’s professional liability policy typically excludes coverage for such work, it behooves all medical directors to insist on being a named insured in the institution’s general liability policy (to include tail coverage), and to be informed in a timely fashion should there be a relevant change or cancellation of coverage. Their contract should stipulate that the facility would indemnify them for all lawsuits arising out of their work. More and more nursing homes are dropping their insurance to bypass legal exposure, leaving the attending physician and/or medical director at increased risk. To avoid a serious gap in coverage, medical directors should consider purchasing a specific medical director policy.5 Medical directors should also be aware of potential Stark Law violations, such as treating private patients without paying fair rent or receiving compensation in exchange for referrals.

Importantly, elder abuse judgments, as opposed to malpractice awards, may negate restrictions on attorney fees and noneconomic damages such as California’s $250,000 cap. The jury may also levy punitive damages, which are not covered by professional insurance. The plaintiff will need to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, something more than simple or gross negligence such as malice, fraud, oppression, or recklessness.6 Under California’s elder abuse and dependent Adult Civil Protection Act, an appellate court has held that a plaintiff may mount an elder abuse claim directed at physicians and not just facilities with “custodial” duties.7This important issue is currently under appeal before the California Supreme Court.

References

1. The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 3, 2014.

2. Stevenson, DG and DM Studdert, The Rise Of Nursing Home Litigation: Findings From A National Survey Of Attorneys. Health Affairs 2003; 22:219-29.

3. Manor Care Inc. v. Douglas, 763 N.E.2d 73 (W. Va. 2014).

4. Fleming v. Barnwell Nursing Hone and Health Facilities Inc., 309 A.D.2d 1132 (N.Y. App. Div. 2003).

5. See the American Medical Directors Association’s (AMDA) offering at http://locktonmedicalliabilityinsurance.com/amda/.

6. Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23 (1999).

7. Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group Inc., 216 Cal. App. 4th 875 (2013).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. He currently directs The St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

OARSI: Bisphosphonate users less likely to undergo knee replacement

SEATTLE – Women with knee osteoarthritis who took bisphosphonates were 27% less likely to undergo joint replacement surgery than were women who didn’t take bisphosphonates in a U.K. cohort study of 3,928 propensity-matched users and nonusers, according to a report at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

“In older women with incident knee osteoarthritis, incident bisphosphonate use may be associated with lower risk of knee replacement than in nonusers,” said Dr. Tuhina Neogi of Boston University.

Dr. Neogi and her colleagues used data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a U.K. database of primary care patients, to identify women aged 50-89 years who received a diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis between 2003 and 2012. Patients were excluded if they were poor surgical candidates or were taking disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic agents, or other bone-active agents.

The researchers compared 1,964 women who subsequently started bisphosphonate therapy with 1,964 propensity score–matched women who did not. In 85% of the former, the bisphosphonate was alendronate, marketed as Fosamax in the United States.

During a mean follow-up of 3 years, the incidence rate of knee replacement was 21 cases per 1,000 patient-years among bisphosphonate users and 29 cases per 1,000 patient-years among nonusers, according to results reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

In adjusted analyses, users had a significantly lower relative risk of undergoing this surgery (hazard ratio, 0.73), reported Dr. Neogi, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sensitivity analyses showed an even stronger association in a separate cohort of patients matched by age, body mass index, and the duration of osteoarthritis (hazard ratio, 0.33) and a nonsignificant benefit when bisphosphonate users were instead compared against an active user group of women who initiated any other bone-modulating therapy.

“Now of course this is observational data from electronic medical records, so we cannot rule out the potential for residual bias,” she acknowledged. “Our sensitivity analyses were fairly consistent and provide some reassurance, but nonetheless, the magnitude of effect is still likely to be biased due to residual confounding.”

In an interview, Dr. Rik Lories, one of the session’s comoderators and a professor at the University of Leuven, Belgium, said that the study “is still far from practice changing. But the great thing about this research is that we are starting to split up what you would call the osteoarthritic diseases, taking osteoarthritis as the outcome [and showing] the underlying mechanisms of the different phenotypes being different.”

Dr. Neogi noted that subchrondral bone changes are prominent in knee osteoarthritis and that mechanical factors play a central role in the disease. At the same time, findings of trials of antiresorptive agents, including bisphosphonates, in knee osteoarthritis have been conflicting.

“There are a number of limitations to this study, including the fact that The Health Improvement Network does not have bone mineral density results. We tried to address this by accounting for a prior diagnosis of osteoporosis, fracture history, potential risk for fractures, body mass index, age, number of bone mineral density tests ordered, et cetera,” Dr. Neogi said. “Another limitation is that of the secular trends in use of bone-modulating agents over this time frame, and that precluded robust evaluation of the active user comparator analysis.

“Bone mineral density is still a major potential confounder here that can’t be adequately addressed,” she acknowledged.

SEATTLE – Women with knee osteoarthritis who took bisphosphonates were 27% less likely to undergo joint replacement surgery than were women who didn’t take bisphosphonates in a U.K. cohort study of 3,928 propensity-matched users and nonusers, according to a report at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.