User login

Team tracks blood formation in real time

in the bone marrow

Scientists have reported a method for equipping mouse hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with a fluorescent marker that can be switched on from the outside.

Using this tool, they were able to observe how HSCs mature into blood cells under normal conditions, and they developed a mathematical model of the dynamics of hematopoiesis.

The research suggests the normal process of hematopoiesis differs from what scientists previously assumed when using data from stem cell transplants.

“[A] problem with almost all research on hematopoiesis in past decades is that it has been restricted to experiments in culture or using transplantation into mice,” said study author Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“We have now developed the first model where we can observe the development of a stem cell into a mature blood cell in a living organism.”

The researchers described this model in Nature.

The team genetically modified mice by introducing a protein into their HSCs that sends out a yellow fluorescent signal. This marker can be turned on by administering a reagent. All daughter cells that arise from a cell containing the marker also send out a light signal.

When they turned on the marker in adult mice, the researchers observed that at least a third of a mouse’s HSCs (approximately 5000 cells) produce differentiated progenitor cells.

“This was the first surprise,” said study author Katrin Busch, also of DKFZ. “Until now, scientists had believed that, in the normal state, very few stem cells—only about 10—are actively involved in blood formation.”

The researchers performed a mathematical analysis of these experimental data to provide additional insight into blood stem cell dynamics. They were surprised to find that, under normal conditions, HSCs do not replenish blood cells.

Instead, blood cells are supplied by the first progenitor cells that develop during the differentiation step. These cells are able to regenerate themselves for a long time, though not quite as long as HSCs.

To ensure that the population of this cell type never runs out, HSCs must occasionally produce a couple of new first progenitors.

During murine embryonic development, however, the situation is different. To build up the system, all mature blood and immune cells develop much more rapidly and almost completely from HSCs.

The researchers were also able to accelerate this process in adult mice by artificially depleting their white blood cells. Under these conditions, HSCs increase the formation of first progenitor cells, which then immediately start supplying new, mature blood cells.

During this process, several hundred times more myeloid cells (thrombocytes, erythrocytes, granulocytes, monocytes) form than long-lived lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells).

“When we transplanted our labeled blood stem cells from the bone marrow into other mice, only a few stem cells were active in the recipients, and many stem cells were lost,” Dr Rodewald noted.

“Our new data therefore show that the findings obtained up until now using transplanted stem cells can surely not be reflective of normal hematopoiesis. On the contrary, transplantation is an exception. This shows how important it is that we actually follow hematopoiesis under normal conditions in a living organism.”

The researchers now plan to use their model to investigate the impact of pathogenic challenges to blood formation; for example, in cancer, cachexia, or infection. This method would also allow them to follow potential aging processes in HSCs as they occur naturally in a living organism. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists have reported a method for equipping mouse hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with a fluorescent marker that can be switched on from the outside.

Using this tool, they were able to observe how HSCs mature into blood cells under normal conditions, and they developed a mathematical model of the dynamics of hematopoiesis.

The research suggests the normal process of hematopoiesis differs from what scientists previously assumed when using data from stem cell transplants.

“[A] problem with almost all research on hematopoiesis in past decades is that it has been restricted to experiments in culture or using transplantation into mice,” said study author Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“We have now developed the first model where we can observe the development of a stem cell into a mature blood cell in a living organism.”

The researchers described this model in Nature.

The team genetically modified mice by introducing a protein into their HSCs that sends out a yellow fluorescent signal. This marker can be turned on by administering a reagent. All daughter cells that arise from a cell containing the marker also send out a light signal.

When they turned on the marker in adult mice, the researchers observed that at least a third of a mouse’s HSCs (approximately 5000 cells) produce differentiated progenitor cells.

“This was the first surprise,” said study author Katrin Busch, also of DKFZ. “Until now, scientists had believed that, in the normal state, very few stem cells—only about 10—are actively involved in blood formation.”

The researchers performed a mathematical analysis of these experimental data to provide additional insight into blood stem cell dynamics. They were surprised to find that, under normal conditions, HSCs do not replenish blood cells.

Instead, blood cells are supplied by the first progenitor cells that develop during the differentiation step. These cells are able to regenerate themselves for a long time, though not quite as long as HSCs.

To ensure that the population of this cell type never runs out, HSCs must occasionally produce a couple of new first progenitors.

During murine embryonic development, however, the situation is different. To build up the system, all mature blood and immune cells develop much more rapidly and almost completely from HSCs.

The researchers were also able to accelerate this process in adult mice by artificially depleting their white blood cells. Under these conditions, HSCs increase the formation of first progenitor cells, which then immediately start supplying new, mature blood cells.

During this process, several hundred times more myeloid cells (thrombocytes, erythrocytes, granulocytes, monocytes) form than long-lived lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells).

“When we transplanted our labeled blood stem cells from the bone marrow into other mice, only a few stem cells were active in the recipients, and many stem cells were lost,” Dr Rodewald noted.

“Our new data therefore show that the findings obtained up until now using transplanted stem cells can surely not be reflective of normal hematopoiesis. On the contrary, transplantation is an exception. This shows how important it is that we actually follow hematopoiesis under normal conditions in a living organism.”

The researchers now plan to use their model to investigate the impact of pathogenic challenges to blood formation; for example, in cancer, cachexia, or infection. This method would also allow them to follow potential aging processes in HSCs as they occur naturally in a living organism. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists have reported a method for equipping mouse hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with a fluorescent marker that can be switched on from the outside.

Using this tool, they were able to observe how HSCs mature into blood cells under normal conditions, and they developed a mathematical model of the dynamics of hematopoiesis.

The research suggests the normal process of hematopoiesis differs from what scientists previously assumed when using data from stem cell transplants.

“[A] problem with almost all research on hematopoiesis in past decades is that it has been restricted to experiments in culture or using transplantation into mice,” said study author Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“We have now developed the first model where we can observe the development of a stem cell into a mature blood cell in a living organism.”

The researchers described this model in Nature.

The team genetically modified mice by introducing a protein into their HSCs that sends out a yellow fluorescent signal. This marker can be turned on by administering a reagent. All daughter cells that arise from a cell containing the marker also send out a light signal.

When they turned on the marker in adult mice, the researchers observed that at least a third of a mouse’s HSCs (approximately 5000 cells) produce differentiated progenitor cells.

“This was the first surprise,” said study author Katrin Busch, also of DKFZ. “Until now, scientists had believed that, in the normal state, very few stem cells—only about 10—are actively involved in blood formation.”

The researchers performed a mathematical analysis of these experimental data to provide additional insight into blood stem cell dynamics. They were surprised to find that, under normal conditions, HSCs do not replenish blood cells.

Instead, blood cells are supplied by the first progenitor cells that develop during the differentiation step. These cells are able to regenerate themselves for a long time, though not quite as long as HSCs.

To ensure that the population of this cell type never runs out, HSCs must occasionally produce a couple of new first progenitors.

During murine embryonic development, however, the situation is different. To build up the system, all mature blood and immune cells develop much more rapidly and almost completely from HSCs.

The researchers were also able to accelerate this process in adult mice by artificially depleting their white blood cells. Under these conditions, HSCs increase the formation of first progenitor cells, which then immediately start supplying new, mature blood cells.

During this process, several hundred times more myeloid cells (thrombocytes, erythrocytes, granulocytes, monocytes) form than long-lived lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells).

“When we transplanted our labeled blood stem cells from the bone marrow into other mice, only a few stem cells were active in the recipients, and many stem cells were lost,” Dr Rodewald noted.

“Our new data therefore show that the findings obtained up until now using transplanted stem cells can surely not be reflective of normal hematopoiesis. On the contrary, transplantation is an exception. This shows how important it is that we actually follow hematopoiesis under normal conditions in a living organism.”

The researchers now plan to use their model to investigate the impact of pathogenic challenges to blood formation; for example, in cancer, cachexia, or infection. This method would also allow them to follow potential aging processes in HSCs as they occur naturally in a living organism. ![]()

CRT may pose long-term risk of hormone deficiencies

Photo by Bill Branson

New research indicates that patients who undergo cranial radiotherapy (CRT) for pediatric cancer may have an increased risk of anterior pituitary deficits decades after they receive treatment.

The study also suggests these deficiencies often go undiagnosed, although they can impact health and quality of life.

These discoveries, reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, highlight the need for lifelong health screenings of pediatric cancer survivors, researchers say.

They studied 748 survivors of leukemia, brain, and other cancers, assessing the prevalence of and risk factors for growth hormone deficiency (GHD), luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone deficiencies (LH/FSHD), thyroid-stimulating hormone deficiency (TSHD), and adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency (ACTHD) after CRT.

The researchers observed survivors for a mean of 27.3 years (range, 10.8 to 47.7 years).

GHD was the most common deficiency, with an estimated point prevalence of 46.5%. The estimated point prevalence was 10.8% for LH/FSHD, 7.5% for TSHD, and 4% for ACTHD. The cumulative incidence of the deficiencies increased with follow-up.

Higher doses of CRT were associated with an increased risk of deficiencies. Doses of 22 to 29.9 Gy were significantly associated with GHD, doses of 22 Gy or higher were associated with LH/FSHD, and doses of 30 Gy or greater were associated with TSHD and ACTHD.

The researchers also found that male sex and obesity were significantly associated with LH/FSHD, and white race was significantly associated with LH/FSHD and TSHD.

GHD and LH/FSHD were the deficiencies that were most likely to be undiagnosed. GHD was not treated in 99.7% of affected survivors, and LH/FSHD was not treated in 78.5%.

There was an association between untreated GHD and reduced strength and muscle size, low energy, poor fitness, and abdominal obesity. Untreated LH/FSHD was associated with low bone mineral density, reduced fitness, high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, and elevated cholesterol and other blood lipids.

“This study provides much needed long-term follow-up data and shows that the risk of pituitary problems follows these survivors into adulthood,” said study author Wassim Chemaitilly, MD, of St Jude Children’s Research Center in Memphis, Tennessee.

“The findings also underscore the need for the nation’s growing population of childhood cancer survivors to get recommended health screenings, and the challenges they face in trying to navigate the healthcare system and follow that advice.”

Guidelines developed by the Children’s Oncology Group call for childhood cancer survivors treated with CRT to have their pituitary function checked annually. Dr Chemaitilly said the high percentage of survivors with previously undiagnosed hormone deficiencies in this study highlights the need for new strategies to ensure survivors receive recommended health checks.

He also said additional research is needed to help guide the management of adults with growth hormone deficiency. Treatment is expensive, and the long-term benefits in adults are uncertain. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

New research indicates that patients who undergo cranial radiotherapy (CRT) for pediatric cancer may have an increased risk of anterior pituitary deficits decades after they receive treatment.

The study also suggests these deficiencies often go undiagnosed, although they can impact health and quality of life.

These discoveries, reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, highlight the need for lifelong health screenings of pediatric cancer survivors, researchers say.

They studied 748 survivors of leukemia, brain, and other cancers, assessing the prevalence of and risk factors for growth hormone deficiency (GHD), luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone deficiencies (LH/FSHD), thyroid-stimulating hormone deficiency (TSHD), and adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency (ACTHD) after CRT.

The researchers observed survivors for a mean of 27.3 years (range, 10.8 to 47.7 years).

GHD was the most common deficiency, with an estimated point prevalence of 46.5%. The estimated point prevalence was 10.8% for LH/FSHD, 7.5% for TSHD, and 4% for ACTHD. The cumulative incidence of the deficiencies increased with follow-up.

Higher doses of CRT were associated with an increased risk of deficiencies. Doses of 22 to 29.9 Gy were significantly associated with GHD, doses of 22 Gy or higher were associated with LH/FSHD, and doses of 30 Gy or greater were associated with TSHD and ACTHD.

The researchers also found that male sex and obesity were significantly associated with LH/FSHD, and white race was significantly associated with LH/FSHD and TSHD.

GHD and LH/FSHD were the deficiencies that were most likely to be undiagnosed. GHD was not treated in 99.7% of affected survivors, and LH/FSHD was not treated in 78.5%.

There was an association between untreated GHD and reduced strength and muscle size, low energy, poor fitness, and abdominal obesity. Untreated LH/FSHD was associated with low bone mineral density, reduced fitness, high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, and elevated cholesterol and other blood lipids.

“This study provides much needed long-term follow-up data and shows that the risk of pituitary problems follows these survivors into adulthood,” said study author Wassim Chemaitilly, MD, of St Jude Children’s Research Center in Memphis, Tennessee.

“The findings also underscore the need for the nation’s growing population of childhood cancer survivors to get recommended health screenings, and the challenges they face in trying to navigate the healthcare system and follow that advice.”

Guidelines developed by the Children’s Oncology Group call for childhood cancer survivors treated with CRT to have their pituitary function checked annually. Dr Chemaitilly said the high percentage of survivors with previously undiagnosed hormone deficiencies in this study highlights the need for new strategies to ensure survivors receive recommended health checks.

He also said additional research is needed to help guide the management of adults with growth hormone deficiency. Treatment is expensive, and the long-term benefits in adults are uncertain. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

New research indicates that patients who undergo cranial radiotherapy (CRT) for pediatric cancer may have an increased risk of anterior pituitary deficits decades after they receive treatment.

The study also suggests these deficiencies often go undiagnosed, although they can impact health and quality of life.

These discoveries, reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, highlight the need for lifelong health screenings of pediatric cancer survivors, researchers say.

They studied 748 survivors of leukemia, brain, and other cancers, assessing the prevalence of and risk factors for growth hormone deficiency (GHD), luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone deficiencies (LH/FSHD), thyroid-stimulating hormone deficiency (TSHD), and adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency (ACTHD) after CRT.

The researchers observed survivors for a mean of 27.3 years (range, 10.8 to 47.7 years).

GHD was the most common deficiency, with an estimated point prevalence of 46.5%. The estimated point prevalence was 10.8% for LH/FSHD, 7.5% for TSHD, and 4% for ACTHD. The cumulative incidence of the deficiencies increased with follow-up.

Higher doses of CRT were associated with an increased risk of deficiencies. Doses of 22 to 29.9 Gy were significantly associated with GHD, doses of 22 Gy or higher were associated with LH/FSHD, and doses of 30 Gy or greater were associated with TSHD and ACTHD.

The researchers also found that male sex and obesity were significantly associated with LH/FSHD, and white race was significantly associated with LH/FSHD and TSHD.

GHD and LH/FSHD were the deficiencies that were most likely to be undiagnosed. GHD was not treated in 99.7% of affected survivors, and LH/FSHD was not treated in 78.5%.

There was an association between untreated GHD and reduced strength and muscle size, low energy, poor fitness, and abdominal obesity. Untreated LH/FSHD was associated with low bone mineral density, reduced fitness, high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, and elevated cholesterol and other blood lipids.

“This study provides much needed long-term follow-up data and shows that the risk of pituitary problems follows these survivors into adulthood,” said study author Wassim Chemaitilly, MD, of St Jude Children’s Research Center in Memphis, Tennessee.

“The findings also underscore the need for the nation’s growing population of childhood cancer survivors to get recommended health screenings, and the challenges they face in trying to navigate the healthcare system and follow that advice.”

Guidelines developed by the Children’s Oncology Group call for childhood cancer survivors treated with CRT to have their pituitary function checked annually. Dr Chemaitilly said the high percentage of survivors with previously undiagnosed hormone deficiencies in this study highlights the need for new strategies to ensure survivors receive recommended health checks.

He also said additional research is needed to help guide the management of adults with growth hormone deficiency. Treatment is expensive, and the long-term benefits in adults are uncertain. ![]()

NICE rejects pomalidomide as MM treatment

In a final draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has said it cannot recommend pomalidomide (Imnovid) for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE recommends thalidomide for most MM patients as a first-line treatment and bortezomib for patients who are unable to receive thalidomide and those who fail first-line treatment.

For patients who have received 2 prior therapies, the agency recommends lenalidomide.

NICE considered pomalidomide for use in MM patients after their third or subsequent relapse.

The agency said it could not recommend pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, within its marketing authorization, which is to treat adults with relapsed and refractory MM who have had at least 2 prior treatments, including lenalidomide and bortezomib, and whose disease has progressed on their last therapy.

“Unfortunately, we cannot recommend pomalidomide, as the analyses from Celgene, the company that markets pomalidomide, showed that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify its high price,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE chief executive.

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it. Until NICE issues its final guidance, National Health Service (NHS) bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments.

This draft guidance does not mean that patients currently taking pomalidomide will stop receiving it. They have the option to continue treatment until they and their clinicians consider it appropriate to stop.

And pomalidomide is recommended for use within NHS Scotland.

Insufficient evidence

The committee advising NICE was not able to judge with any confidence how much more effective pomalidomide was compared with current treatment options based on the evidence provided by Celgene before and after consultation.

However, bearing in mind the magnitude of the differences in the overall survival estimates between pomalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone in the phase 3 MM-003 trial, and all data presented to the committee for comparators, the committee was persuaded that pomalidomide extends life for at least 3 months, on average, when compared with standard NHS care.

Nevertheless, considering the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, the committee concluded that, even with the end-of-life criteria met, the weighting that would have to be placed on the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained would be too high to consider pomalidomide a cost-effective use of NHS resources.

Also, the committee concluded that the uncertainty in the relative effectiveness of pomalidomide compared with established NHS practice would affect any weighting that could be placed on the QALYs gained.

All cost-per-QALY figures presented by Celgene were over £50,000 compared with bortezomib and over £70,000 compared with bendamustine plus thalidomide and dexamethasone. And the figures would further increase when a number of more realistic assumptions were included in the model, the committee said.

A pack of pomalidomide (21 tablets of 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg) costs £8884. The recommended dosage of the drug is 4 mg once daily, taken on days 1 to 21 of repeated 28 day cycles. Treatment should continue until disease progression. ![]()

In a final draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has said it cannot recommend pomalidomide (Imnovid) for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE recommends thalidomide for most MM patients as a first-line treatment and bortezomib for patients who are unable to receive thalidomide and those who fail first-line treatment.

For patients who have received 2 prior therapies, the agency recommends lenalidomide.

NICE considered pomalidomide for use in MM patients after their third or subsequent relapse.

The agency said it could not recommend pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, within its marketing authorization, which is to treat adults with relapsed and refractory MM who have had at least 2 prior treatments, including lenalidomide and bortezomib, and whose disease has progressed on their last therapy.

“Unfortunately, we cannot recommend pomalidomide, as the analyses from Celgene, the company that markets pomalidomide, showed that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify its high price,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE chief executive.

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it. Until NICE issues its final guidance, National Health Service (NHS) bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments.

This draft guidance does not mean that patients currently taking pomalidomide will stop receiving it. They have the option to continue treatment until they and their clinicians consider it appropriate to stop.

And pomalidomide is recommended for use within NHS Scotland.

Insufficient evidence

The committee advising NICE was not able to judge with any confidence how much more effective pomalidomide was compared with current treatment options based on the evidence provided by Celgene before and after consultation.

However, bearing in mind the magnitude of the differences in the overall survival estimates between pomalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone in the phase 3 MM-003 trial, and all data presented to the committee for comparators, the committee was persuaded that pomalidomide extends life for at least 3 months, on average, when compared with standard NHS care.

Nevertheless, considering the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, the committee concluded that, even with the end-of-life criteria met, the weighting that would have to be placed on the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained would be too high to consider pomalidomide a cost-effective use of NHS resources.

Also, the committee concluded that the uncertainty in the relative effectiveness of pomalidomide compared with established NHS practice would affect any weighting that could be placed on the QALYs gained.

All cost-per-QALY figures presented by Celgene were over £50,000 compared with bortezomib and over £70,000 compared with bendamustine plus thalidomide and dexamethasone. And the figures would further increase when a number of more realistic assumptions were included in the model, the committee said.

A pack of pomalidomide (21 tablets of 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg) costs £8884. The recommended dosage of the drug is 4 mg once daily, taken on days 1 to 21 of repeated 28 day cycles. Treatment should continue until disease progression. ![]()

In a final draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has said it cannot recommend pomalidomide (Imnovid) for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE recommends thalidomide for most MM patients as a first-line treatment and bortezomib for patients who are unable to receive thalidomide and those who fail first-line treatment.

For patients who have received 2 prior therapies, the agency recommends lenalidomide.

NICE considered pomalidomide for use in MM patients after their third or subsequent relapse.

The agency said it could not recommend pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, within its marketing authorization, which is to treat adults with relapsed and refractory MM who have had at least 2 prior treatments, including lenalidomide and bortezomib, and whose disease has progressed on their last therapy.

“Unfortunately, we cannot recommend pomalidomide, as the analyses from Celgene, the company that markets pomalidomide, showed that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify its high price,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE chief executive.

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it. Until NICE issues its final guidance, National Health Service (NHS) bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments.

This draft guidance does not mean that patients currently taking pomalidomide will stop receiving it. They have the option to continue treatment until they and their clinicians consider it appropriate to stop.

And pomalidomide is recommended for use within NHS Scotland.

Insufficient evidence

The committee advising NICE was not able to judge with any confidence how much more effective pomalidomide was compared with current treatment options based on the evidence provided by Celgene before and after consultation.

However, bearing in mind the magnitude of the differences in the overall survival estimates between pomalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone in the phase 3 MM-003 trial, and all data presented to the committee for comparators, the committee was persuaded that pomalidomide extends life for at least 3 months, on average, when compared with standard NHS care.

Nevertheless, considering the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, the committee concluded that, even with the end-of-life criteria met, the weighting that would have to be placed on the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained would be too high to consider pomalidomide a cost-effective use of NHS resources.

Also, the committee concluded that the uncertainty in the relative effectiveness of pomalidomide compared with established NHS practice would affect any weighting that could be placed on the QALYs gained.

All cost-per-QALY figures presented by Celgene were over £50,000 compared with bortezomib and over £70,000 compared with bendamustine plus thalidomide and dexamethasone. And the figures would further increase when a number of more realistic assumptions were included in the model, the committee said.

A pack of pomalidomide (21 tablets of 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg) costs £8884. The recommended dosage of the drug is 4 mg once daily, taken on days 1 to 21 of repeated 28 day cycles. Treatment should continue until disease progression. ![]()

PE surgery prevents death in severely ill

Photo courtesy of Medical

College of Georgia

Pulmonary embolectomy, a procedure that was virtually abandoned in the 1950s because it resulted in high mortality rates, may actually prevent more deaths in severely ill patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) than current drug therapies alone, according to research published in the Texas Heart Institute Journal.

More than 2 dozen studies conducted between 1961 and 1984 suggest the death rate associated with pulmonary embolectomy is 32%.

But safer techniques have led to better outcomes, and surgeons continue to take their most seriously ill PE patients into the operating room.

Still, Alan R. Hartman, MD, of North Shore-LIJ Health System in Great Neck, New York, and his colleagues wanted to determine just how successful the surgery is and which patients are the best candidates for surgery.

To find out, the team went back into the surgical archives and identified 96 patients who underwent surgery during a 9-year period (from 2003 to 2011). The researchers assessed how many patients survived in the month following surgery and compared the results to historical mortality data from patients who did not undergo surgery.

All of the patients who had undergone surgery had acute, centrally located PE and severe global hyperkinetic right ventricular dysfunction.

All patients had either a large clot burden in the main pulmonary arteries or a saddle embolism. None of the patients had a history of chronic pulmonary thrombolytic disease or evidence of chronic disease on a computed-tomographic-angiography scan.

They all made it to surgery within an hour of the embolism. The surgery was performed through cardiopulmonary bypass, at normal body temperature, and without aortic cross-clamping, thus avoiding myocardial ischemia.

A pulmonary arteriotomy and clot extraction were performed under direct vision, according to Dr Hartman, which he believes is critical to the success of the procedure.

The mortality rate was 4.2%, which is lower than any other published reports. In addition, 68 patients (73.9%) were discharged home or to rehabilitation facilities.

Those patients with low blood pressure had a higher 30-day mortality rate—12.5% compared to 1.4% in those with normal blood pressure. Patients with low blood pressure also spent a longer time in the hospital—13.4 days compared to 9.1 days in patients with normal blood pressure.

Based on these results, the researchers concluded that acute pulmonary embolectomy can be a viable procedure for patients with severe, globally hypokinetic right ventricular dysfunction, with or without hemodynamic compromise.

However, they cautioned that rates of success are dependent upon experience, surgical ability, and careful patient selection. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Medical

College of Georgia

Pulmonary embolectomy, a procedure that was virtually abandoned in the 1950s because it resulted in high mortality rates, may actually prevent more deaths in severely ill patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) than current drug therapies alone, according to research published in the Texas Heart Institute Journal.

More than 2 dozen studies conducted between 1961 and 1984 suggest the death rate associated with pulmonary embolectomy is 32%.

But safer techniques have led to better outcomes, and surgeons continue to take their most seriously ill PE patients into the operating room.

Still, Alan R. Hartman, MD, of North Shore-LIJ Health System in Great Neck, New York, and his colleagues wanted to determine just how successful the surgery is and which patients are the best candidates for surgery.

To find out, the team went back into the surgical archives and identified 96 patients who underwent surgery during a 9-year period (from 2003 to 2011). The researchers assessed how many patients survived in the month following surgery and compared the results to historical mortality data from patients who did not undergo surgery.

All of the patients who had undergone surgery had acute, centrally located PE and severe global hyperkinetic right ventricular dysfunction.

All patients had either a large clot burden in the main pulmonary arteries or a saddle embolism. None of the patients had a history of chronic pulmonary thrombolytic disease or evidence of chronic disease on a computed-tomographic-angiography scan.

They all made it to surgery within an hour of the embolism. The surgery was performed through cardiopulmonary bypass, at normal body temperature, and without aortic cross-clamping, thus avoiding myocardial ischemia.

A pulmonary arteriotomy and clot extraction were performed under direct vision, according to Dr Hartman, which he believes is critical to the success of the procedure.

The mortality rate was 4.2%, which is lower than any other published reports. In addition, 68 patients (73.9%) were discharged home or to rehabilitation facilities.

Those patients with low blood pressure had a higher 30-day mortality rate—12.5% compared to 1.4% in those with normal blood pressure. Patients with low blood pressure also spent a longer time in the hospital—13.4 days compared to 9.1 days in patients with normal blood pressure.

Based on these results, the researchers concluded that acute pulmonary embolectomy can be a viable procedure for patients with severe, globally hypokinetic right ventricular dysfunction, with or without hemodynamic compromise.

However, they cautioned that rates of success are dependent upon experience, surgical ability, and careful patient selection. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Medical

College of Georgia

Pulmonary embolectomy, a procedure that was virtually abandoned in the 1950s because it resulted in high mortality rates, may actually prevent more deaths in severely ill patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) than current drug therapies alone, according to research published in the Texas Heart Institute Journal.

More than 2 dozen studies conducted between 1961 and 1984 suggest the death rate associated with pulmonary embolectomy is 32%.

But safer techniques have led to better outcomes, and surgeons continue to take their most seriously ill PE patients into the operating room.

Still, Alan R. Hartman, MD, of North Shore-LIJ Health System in Great Neck, New York, and his colleagues wanted to determine just how successful the surgery is and which patients are the best candidates for surgery.

To find out, the team went back into the surgical archives and identified 96 patients who underwent surgery during a 9-year period (from 2003 to 2011). The researchers assessed how many patients survived in the month following surgery and compared the results to historical mortality data from patients who did not undergo surgery.

All of the patients who had undergone surgery had acute, centrally located PE and severe global hyperkinetic right ventricular dysfunction.

All patients had either a large clot burden in the main pulmonary arteries or a saddle embolism. None of the patients had a history of chronic pulmonary thrombolytic disease or evidence of chronic disease on a computed-tomographic-angiography scan.

They all made it to surgery within an hour of the embolism. The surgery was performed through cardiopulmonary bypass, at normal body temperature, and without aortic cross-clamping, thus avoiding myocardial ischemia.

A pulmonary arteriotomy and clot extraction were performed under direct vision, according to Dr Hartman, which he believes is critical to the success of the procedure.

The mortality rate was 4.2%, which is lower than any other published reports. In addition, 68 patients (73.9%) were discharged home or to rehabilitation facilities.

Those patients with low blood pressure had a higher 30-day mortality rate—12.5% compared to 1.4% in those with normal blood pressure. Patients with low blood pressure also spent a longer time in the hospital—13.4 days compared to 9.1 days in patients with normal blood pressure.

Based on these results, the researchers concluded that acute pulmonary embolectomy can be a viable procedure for patients with severe, globally hypokinetic right ventricular dysfunction, with or without hemodynamic compromise.

However, they cautioned that rates of success are dependent upon experience, surgical ability, and careful patient selection. ![]()

Modifier -25 Use in Dermatology

According to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), modifier -25 is to be used to identify “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service.”1 Modifier -25 frequently is integral to the description of patient visits in dermatology. Dermatologists use modifier -25 more than physicians of any other specialty, and in recent years, more than 50% of dermatology evaluation and management (E/M) visits have been appended with this modifier.

When patients present for assessment and management of various skin findings, a dermatologist may deem it appropriate to proceed with a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure at the same visit after obtaining the patient’s medical history, completing a review of systems, and conducting a clinical examination. Most commonly, a skin biopsy or destruction of a benign or malignant lesion may be performed, but other simple procedures also may be appropriate. The ability to assess and intervene during the same visit is optimal for patients who subsequently may require fewer follow-up visits and experience more immediate relief from their symptoms.

When E/M Cannot Be Billed Separately

Regulatory guidance from the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) dated January 2013 indicates that procedures with a global period of 90 days are major surgical procedures, and if an E/M service is performed on the same day as such a procedure to decide whether or not to perform that procedure, then the E/M service should be reported with modifier -57.2 On the other hand, CPT defines procedures with a 0- or 10-day global period as minor surgical procedures, and E/M services provided on the same day of service as these procedures are included in the procedure code and cannot be billed separately. For review, common dermatologic procedures with 0-day global periods include biopsies (CPT code 11000), shave removals (11300–11313), debridements (11000, 11011–11042), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311–17315); procedures with 10-day global periods include destructions (17000–17286), excisions (11400–11646), and repairs (12001–13153). If an E/M service is performed on the same day as one of these procedures to decide whether to proceed with the minor surgical procedure, this E/M service cannot be reported separately. Additionally, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M with such a minor procedure.

When E/M Can Be Billed Separately

However, a “significant and separately identifiable E/M service unrelated to the decision to perform the minor procedure” is separately reportable with modifier -25. According to the NCCI, the minor procedure and the E/M do not require different diagnoses, but the E/M service must be above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.2 Because a certain amount of so-called preservice time is built into minor procedure codes, the implication is that substantially more E/M was needed than envisioned in this preservice time, necessitating inclusion of an E/M in addition to a minor procedure when there is a single diagnosis.

When there is a single diagnosis, the physician has to decide when such a significant and separately identifiable service exists. If the physician determines that it is appropriate to code for E/M in addition to the minor procedure, clear documentation of the additional E/M service provided will reduce the likelihood of this choice being questioned. Specifically, it may be helpful to describe the additional history, examination results, medical knowledge, professional skill, and work time above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.

When there are many diagnosis codes for a single visit and only a subset of them are associated with the minor procedure, as is common in dermatology, then the decision to include an E/M service is simpler. In this case, if E/M services were provided that pertained to a diagnosis or diagnoses other than the one(s) associated with the minor procedure(s), then these additional E/M services will clearly not be included in the preservice time for the procedure and an E/M can virtually always be coded separately. For instance, if a patient presents with a growing scaly bump (clinically apparent squamous cell carcinoma) on the leg that the dermatologist deems is appropriate for biopsy but concurrently notices nummular dermatitis of the legs, which the patient describes as itchy and uncomfortable, then the diagnosis and management of the dermatitis would clearly be a separate E/M service and would not be included in the workup for the biopsy. The E/M code that is applied should, of course, reflect the services provided exclusive of those integral to the minor procedure. To make it easier for regulators and auditors, it may be helpful to clearly itemize the additional diagnoses unrelated to the minor procedure and describe the specific E/M services provided for these diagnoses. Although it is certainly not necessary or required, it also may be helpful to physically separate the documentation for the minor procedure from the E/M services for the additional diagnoses within the medical chart.

Final Thoughts

It is clear that frequent use of modifier -25 is appropriate in routine, high-quality dermatologic practice. Simultaneous provision of E/M services and minor procedures often is in the patient’s best interest, as it minimizes unnecessary office visits and expedites treatment. When modifier -25 is appropriately appended, careful documentation by the dermatologist can help to clarify the precise basis for its use. Recent NCCI edits provide guidelines for use of this modifier that can be adapted by individual dermatologists for particular patient circumstances.2

1. CPT 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2014.

2. National Correct Coding Initiative Policy Manual for Medicare Services. Carmel, IN: National Correct Coding Initiative; 2013.

According to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), modifier -25 is to be used to identify “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service.”1 Modifier -25 frequently is integral to the description of patient visits in dermatology. Dermatologists use modifier -25 more than physicians of any other specialty, and in recent years, more than 50% of dermatology evaluation and management (E/M) visits have been appended with this modifier.

When patients present for assessment and management of various skin findings, a dermatologist may deem it appropriate to proceed with a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure at the same visit after obtaining the patient’s medical history, completing a review of systems, and conducting a clinical examination. Most commonly, a skin biopsy or destruction of a benign or malignant lesion may be performed, but other simple procedures also may be appropriate. The ability to assess and intervene during the same visit is optimal for patients who subsequently may require fewer follow-up visits and experience more immediate relief from their symptoms.

When E/M Cannot Be Billed Separately

Regulatory guidance from the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) dated January 2013 indicates that procedures with a global period of 90 days are major surgical procedures, and if an E/M service is performed on the same day as such a procedure to decide whether or not to perform that procedure, then the E/M service should be reported with modifier -57.2 On the other hand, CPT defines procedures with a 0- or 10-day global period as minor surgical procedures, and E/M services provided on the same day of service as these procedures are included in the procedure code and cannot be billed separately. For review, common dermatologic procedures with 0-day global periods include biopsies (CPT code 11000), shave removals (11300–11313), debridements (11000, 11011–11042), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311–17315); procedures with 10-day global periods include destructions (17000–17286), excisions (11400–11646), and repairs (12001–13153). If an E/M service is performed on the same day as one of these procedures to decide whether to proceed with the minor surgical procedure, this E/M service cannot be reported separately. Additionally, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M with such a minor procedure.

When E/M Can Be Billed Separately

However, a “significant and separately identifiable E/M service unrelated to the decision to perform the minor procedure” is separately reportable with modifier -25. According to the NCCI, the minor procedure and the E/M do not require different diagnoses, but the E/M service must be above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.2 Because a certain amount of so-called preservice time is built into minor procedure codes, the implication is that substantially more E/M was needed than envisioned in this preservice time, necessitating inclusion of an E/M in addition to a minor procedure when there is a single diagnosis.

When there is a single diagnosis, the physician has to decide when such a significant and separately identifiable service exists. If the physician determines that it is appropriate to code for E/M in addition to the minor procedure, clear documentation of the additional E/M service provided will reduce the likelihood of this choice being questioned. Specifically, it may be helpful to describe the additional history, examination results, medical knowledge, professional skill, and work time above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.

When there are many diagnosis codes for a single visit and only a subset of them are associated with the minor procedure, as is common in dermatology, then the decision to include an E/M service is simpler. In this case, if E/M services were provided that pertained to a diagnosis or diagnoses other than the one(s) associated with the minor procedure(s), then these additional E/M services will clearly not be included in the preservice time for the procedure and an E/M can virtually always be coded separately. For instance, if a patient presents with a growing scaly bump (clinically apparent squamous cell carcinoma) on the leg that the dermatologist deems is appropriate for biopsy but concurrently notices nummular dermatitis of the legs, which the patient describes as itchy and uncomfortable, then the diagnosis and management of the dermatitis would clearly be a separate E/M service and would not be included in the workup for the biopsy. The E/M code that is applied should, of course, reflect the services provided exclusive of those integral to the minor procedure. To make it easier for regulators and auditors, it may be helpful to clearly itemize the additional diagnoses unrelated to the minor procedure and describe the specific E/M services provided for these diagnoses. Although it is certainly not necessary or required, it also may be helpful to physically separate the documentation for the minor procedure from the E/M services for the additional diagnoses within the medical chart.

Final Thoughts

It is clear that frequent use of modifier -25 is appropriate in routine, high-quality dermatologic practice. Simultaneous provision of E/M services and minor procedures often is in the patient’s best interest, as it minimizes unnecessary office visits and expedites treatment. When modifier -25 is appropriately appended, careful documentation by the dermatologist can help to clarify the precise basis for its use. Recent NCCI edits provide guidelines for use of this modifier that can be adapted by individual dermatologists for particular patient circumstances.2

According to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), modifier -25 is to be used to identify “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service.”1 Modifier -25 frequently is integral to the description of patient visits in dermatology. Dermatologists use modifier -25 more than physicians of any other specialty, and in recent years, more than 50% of dermatology evaluation and management (E/M) visits have been appended with this modifier.

When patients present for assessment and management of various skin findings, a dermatologist may deem it appropriate to proceed with a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure at the same visit after obtaining the patient’s medical history, completing a review of systems, and conducting a clinical examination. Most commonly, a skin biopsy or destruction of a benign or malignant lesion may be performed, but other simple procedures also may be appropriate. The ability to assess and intervene during the same visit is optimal for patients who subsequently may require fewer follow-up visits and experience more immediate relief from their symptoms.

When E/M Cannot Be Billed Separately

Regulatory guidance from the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) dated January 2013 indicates that procedures with a global period of 90 days are major surgical procedures, and if an E/M service is performed on the same day as such a procedure to decide whether or not to perform that procedure, then the E/M service should be reported with modifier -57.2 On the other hand, CPT defines procedures with a 0- or 10-day global period as minor surgical procedures, and E/M services provided on the same day of service as these procedures are included in the procedure code and cannot be billed separately. For review, common dermatologic procedures with 0-day global periods include biopsies (CPT code 11000), shave removals (11300–11313), debridements (11000, 11011–11042), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311–17315); procedures with 10-day global periods include destructions (17000–17286), excisions (11400–11646), and repairs (12001–13153). If an E/M service is performed on the same day as one of these procedures to decide whether to proceed with the minor surgical procedure, this E/M service cannot be reported separately. Additionally, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M with such a minor procedure.

When E/M Can Be Billed Separately

However, a “significant and separately identifiable E/M service unrelated to the decision to perform the minor procedure” is separately reportable with modifier -25. According to the NCCI, the minor procedure and the E/M do not require different diagnoses, but the E/M service must be above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.2 Because a certain amount of so-called preservice time is built into minor procedure codes, the implication is that substantially more E/M was needed than envisioned in this preservice time, necessitating inclusion of an E/M in addition to a minor procedure when there is a single diagnosis.

When there is a single diagnosis, the physician has to decide when such a significant and separately identifiable service exists. If the physician determines that it is appropriate to code for E/M in addition to the minor procedure, clear documentation of the additional E/M service provided will reduce the likelihood of this choice being questioned. Specifically, it may be helpful to describe the additional history, examination results, medical knowledge, professional skill, and work time above and beyond what is usually required for the minor surgical procedure.

When there are many diagnosis codes for a single visit and only a subset of them are associated with the minor procedure, as is common in dermatology, then the decision to include an E/M service is simpler. In this case, if E/M services were provided that pertained to a diagnosis or diagnoses other than the one(s) associated with the minor procedure(s), then these additional E/M services will clearly not be included in the preservice time for the procedure and an E/M can virtually always be coded separately. For instance, if a patient presents with a growing scaly bump (clinically apparent squamous cell carcinoma) on the leg that the dermatologist deems is appropriate for biopsy but concurrently notices nummular dermatitis of the legs, which the patient describes as itchy and uncomfortable, then the diagnosis and management of the dermatitis would clearly be a separate E/M service and would not be included in the workup for the biopsy. The E/M code that is applied should, of course, reflect the services provided exclusive of those integral to the minor procedure. To make it easier for regulators and auditors, it may be helpful to clearly itemize the additional diagnoses unrelated to the minor procedure and describe the specific E/M services provided for these diagnoses. Although it is certainly not necessary or required, it also may be helpful to physically separate the documentation for the minor procedure from the E/M services for the additional diagnoses within the medical chart.

Final Thoughts

It is clear that frequent use of modifier -25 is appropriate in routine, high-quality dermatologic practice. Simultaneous provision of E/M services and minor procedures often is in the patient’s best interest, as it minimizes unnecessary office visits and expedites treatment. When modifier -25 is appropriately appended, careful documentation by the dermatologist can help to clarify the precise basis for its use. Recent NCCI edits provide guidelines for use of this modifier that can be adapted by individual dermatologists for particular patient circumstances.2

1. CPT 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2014.

2. National Correct Coding Initiative Policy Manual for Medicare Services. Carmel, IN: National Correct Coding Initiative; 2013.

1. CPT 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2014.

2. National Correct Coding Initiative Policy Manual for Medicare Services. Carmel, IN: National Correct Coding Initiative; 2013.

Practice Points

- Frequent use of modifier -25 is appropriate in routine, high-quality dermatologic practice.

- The global period (0, 10, or 90 days) of a procedure dictates if evaluation and management services provided on the same day of service as the original procedure can be billed separately.

- Careful documentation by the dermatologist can help clarify the precise basis for the use of modifier -25.

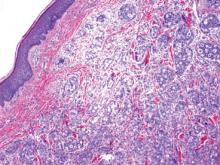

Pseudoglandular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

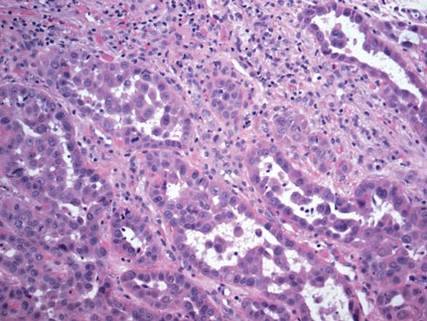

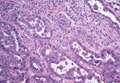

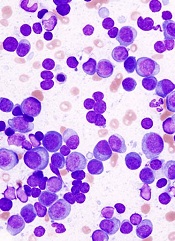

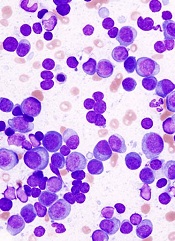

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

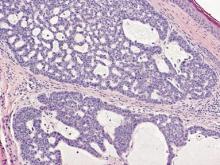

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

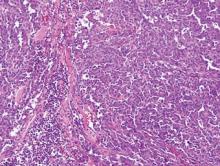

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

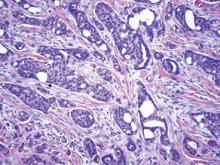

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

VIDEO: Embolectomy’s success in stroke mandates expanded access

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Newly reported results from three trials showing “profound” benefit from endovascular embolectomy in selected patients with acute ischemic stroke “will have a major impact on how we treat stroke patients,” Dr. Lee H. Schwamm said during an interview at the International Stroke Conference.

“Many centers already provide this treatment, but this is the first time we have data on which patients to select” for catheter-based embolectomy, said Dr. Schwamm, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “Because we already have the capability in many centers, the first focus will be to extend the number of centers that can do this,” Dr. Schwamm noted.

An important part of that will be “changing the public health system to route patients to appropriate facilities” that can perform embolectomy, he said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Dr. Schwamm also noted that intravenous, thrombolytic treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) remains unchanged as the key first treatment for all patients with acute ischemic stroke. Following that, selected patients who do not fully respond to TPA should proceed to embolectomy. However, the new findings “do not suggest that you should avoid TPA and go directly to the catheter,” Dr. Schwamm cautioned.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Newly reported results from three trials showing “profound” benefit from endovascular embolectomy in selected patients with acute ischemic stroke “will have a major impact on how we treat stroke patients,” Dr. Lee H. Schwamm said during an interview at the International Stroke Conference.

“Many centers already provide this treatment, but this is the first time we have data on which patients to select” for catheter-based embolectomy, said Dr. Schwamm, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “Because we already have the capability in many centers, the first focus will be to extend the number of centers that can do this,” Dr. Schwamm noted.

An important part of that will be “changing the public health system to route patients to appropriate facilities” that can perform embolectomy, he said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Dr. Schwamm also noted that intravenous, thrombolytic treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) remains unchanged as the key first treatment for all patients with acute ischemic stroke. Following that, selected patients who do not fully respond to TPA should proceed to embolectomy. However, the new findings “do not suggest that you should avoid TPA and go directly to the catheter,” Dr. Schwamm cautioned.