User login

Varicella-Zoster Virus in Children Immunized With the Varicella Vaccine

Faulty equipment blamed for improper diagnosis: $78M verdict … and more

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Ins and outs of straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy

Watch 3 videos illustrating laparoscopic myomectomy

These videos were provided by Gaby Moawad, MD, and James Robinson, MD, MS.

By age 50, almost 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women will have a uterine leiomyoma.1 These benign, hormone-sensitive neoplasms1 are asymptomatic in the majority of women, but they can cause infertility, abnormal uterine bleeding, and bulk symptoms.2

When symptomatic, fibroids are amenable to multiple management options, ranging from expectant management to medical therapy to uterine artery embolization to myomectomy to hysterectomy. Myomectomy remains the surgical option of choice for women with symptomatic fibroids who wish to retain their fertility. It is also an option for some women who may not desire fertility retention but who do wish to maintain their uterus.

Compared with traditional myomectomy by laparotomy, laparoscopic myomectomy offers the advantages of:

- less blood loss

- less postoperative pain

- less postoperative adhesions formation

- faster recovery

- better cosmesis.3,4

Current technology makes performing laparoscopic myomectomy by either “straight-stick” or robotic assistance a viable option for most women.

In this article, we describe our technique in performing straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative evaluation: The first key to success

Laparoscopic myomectomy is an advanced, delicate, and challenging surgery. Preoperative evaluation is integral to its planning and a successful outcome.

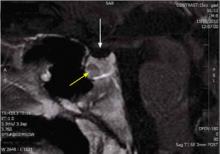

Imaging

We recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a standard order whenever a laparoscopic approach to myomectomy is being considered, for several reasons. First, MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast allows for a precise map of the location of fibroids in relation to the myometrium and the uterine cavity. Reviewing the MRI results with the patient preoperatively gives both you and the patient a clearer picture of the challenges ahead. Patients tell us they appreciate these easier-to-understand images of their anatomy and, in cases when the decision is made to proceed abdominally, it is more clear to the patient why the decision is being made.

Surgically, the MRI helps compensate for the lack of tactile feedback when faced with deep intramural fibroids laparoscopically. The MRI also helps avoid operative surprises. Experience teaches us that, when relying on transvaginal ultrasound alone, adenomyotic regions can be identified mistakenly as fibroids. Preoperative MRI can help you avoid this discovery at the time of surgery.

A flexible office hysteroscopy serves as an adjunct to MRI for precise preoperative cavitary evaluation, especially when fibroids are present in close proximity to the endometrial cavity or the patient reports menorrhagia as a component of her symptomatology. When small submucosal fibroids exist in addition to larger fibroids, we frequently perform a combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic approach to myomectomy.

Although bowel preparation does not diminish complications from bowel surgery or improve outcome,5 we generally use laxative suppositories the night prior to surgery to improve access to the posterior cul-de-sac and reduce bulk resulting from a sigmoid full of feces.

Preoperative laboratory evaluation should always include complete blood count, beta hCG, blood type testing, and antibody screen. In patients with known anemia or large intramural fibroids, we typically match the patient for 2 units of packed red blood cells. Additionally, if significant blood loss is anticipated, cell saver technology can be modified to accommodate a laparoscopic suction tip, allowing the patient’s own blood to be collected and readministered.

Aside from the standard risks of surgery, including bleeding, transfusion, infection, and injury to adjacent organs, myomectomy has its own unique risks that need to be made clear to patients preoperatively.

Surgery timing. Initially, women with symptomatic fibroids are at significant risk for developing more fibroids in the future. In fact, 25% of women who undergo myomectomy will require a second surgery at some point in their lives to address recurrent symptoms.1 If women are young, not yet ready to conceive, and are still relatively asymptomatic, waiting to perform myomectomy may be the most prudent course.

Future uterine rupture. There are no good myomectomy data to guide us with respect to the risk of uterine rupture at future pregnancy. When we perform deep intramural myomectomy (regardless of endometrial disruption), we extrapolate from classical cesarean section data and counsel our patients to have planned cesarean sections for all future pregnancies. Patients are also counseled that uterine rupture has been well described after laparoscopic myomectomy prior to the onset of labor so any sudden onset of pain or bleeding during the late second or third trimester of pregnancy has to be regarded as a medical emergency.

Pregnancy. Again, no good data exist to guide us with respect to postoperative timing of future pregnancy. We typically suggest patients refrain from conceiving following myomectomy for at least 6 months. We are aware that other well-respected surgeons have different thresholds.

Reference

1. Andiani GB, Fedele L, Parazzini F, Villa L. Risk of recurrence after myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(4):385-389.

How to minimize blood loss

Blood loss during laparoscopic myomectomy generally is less than during laparotomy due to venous compression from pneumoperitoneum. However, blood loss remains a chief concern when performing laparoscopic myomectomy. A variety of techniques have been described to minimize blood loss, including injection of dilute vasopressin6 and tourniquet placement around uterine vessels.7

Injection. To temporarily minimize bleeding in the surgical field, we routinely utilize subserosal injection of dilute vasopressin (20 IU in 100 mL of normal saline) until visible vessels blanch. This practice is more effective than deep myoma or myometrial injection.

Tourniquet. We selectively use a laparoscopically placed tourniquet to compress uterine arteries at the mid-cervix during surgery. One approach is as follows (see VIDEO 1):

- Open windows in bilateral broad ligaments lateral to the uterine pedicles and medial to the ureters.

- Pass the end of a 14-16 French red rubber catheter through one of the low lateral port sites with the port removed.

- Tag the trailing end of the tourniquet outside the abdomen and replace the port alongside the catheter.

- Pass the end of the catheter down through the ipsilateral broad ligament window and under the posterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter up through the contralateral broad ligament window and over the anterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter through each of the broad ligament windows a second time and then out through the contralateral port site.

- Pull the tourniquet tight from both port sites (which will occlude the uterine arteries). Place Kelly clamps on the catheter ends where they exit the port sites to maintain tension until the end of the uterine repair.

Lateral ports can still be utilized with the tourniquet in place.

Permanent occlusion. In women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy who have completed child bearing, we advocate permanent uterine artery occlusion at the origin of the uterine arteries retroperitoneally. This can be performed in a number of ways— utilizing clips, suture, or transection. Uterine artery occlusion not only leads to less operative blood loss but preliminary studies also suggest it decreases the risk of fibroid recurrence.8

After the patient is prepped and draped in low lithotomy position with her arms tucked at her sides, drain the bladder with an indwelling catheter. Insert a uterine manipulator, such as the VCare (Conmed Corporation), into the uterus.

Obtain umbilical entry for a 30° optic scope, and place the patient in steep Trendelenburg position. We use two 5-mm lateral ports and one 12-mm suprapubic port. The level of placement of the lateral ports is tailored to the size of the fibroids; it can be anywhere from the level of the anterior iliac spine to the level of the umbilicus for fibroids contained in the pelvis or in the abdomen, respectively.

Uterine incision

After vasopressin injection, tourniquet placement, or permanent uterine artery occlusion is performed as described above, we advocate a transverse uterine incision. We do so mainly because:

- The transverse incision runs parallel to the arcuate vessels of the myometrium, leading to less bleeding.

- We suture from the lateral ports so the transverse incision facilitates a more ergonomic repair.

Perform the uterine incision (we use the Harmonic Ace [Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc]) through the uterine serosa deep toward the myoma. Incision size should be appropriate to the diameter of the fibroid; smaller incisions result in unnecessary struggling during enucleation of the fibroid. Incision depth should reach the fibroid capsule, and this incision should be developed over the entire fibroid. Tunneling in the myometrium is undesirable and should be avoided because it increases myometrial injury as well as the risk of hematoma.

Fibroid enucleation

Once the initial uterine incision is complete, enucleate the fibroid using a combination of traction, countertraction, sharp, and blunt dissection (see VIDEO 2). Pearls to successful enucleation include:

- Maintain traction and countertraction when cutting tissue. This helps to identify appropriate planes and allows tissue to separate quickly, minimizing thermal energy spread.

- Replace the tenaculum or myoma screw regularly at the border of the myoma and myometrium. The ultrasonic scalpel blade can be drilled into the myoma in order to create traction on the myoma.

- Bluntly peel tissue from the myoma outward. Ideally all myometrium and vessels should stay with the uterus. A properly enucleated fibroid will be pearly in appearance and avascular.

- Be particularly careful when in contact with the endometrium. Even submucous fibroids can be enucleated regularly without entering the endometrial cavity.

Uterine repair

If the endometrial cavity is inadvertently entered, close the defect (we use a 2-0 monocryl or Vicryl suture). Next, imbricate the endometrium over with successive layers, taking special care not to pass a needle into the endometrial cavity. In cases in which significant endometrial disruption cannot be avoided, use a postoperative intrauterine balloon stent. This is placed postoperatively and left in place for 2 weeks. To stimulate endometrial proliferation, we prescribe oral estradiol 1 mg twice per day for 4 weeks. Following endometrial stimulation, we prescribe a 10-day progestin withdrawal and ask the patient to return to the office for a flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy following her first menses to ensure cavitary integrity.

Once fibroid enucleation is complete, perform a multilayer closure of the defect using an absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture (V-Loc, Covidien). Eliminate all dead space in the closure. The last two throws of each barbed suture should be in the direction of the prior two throws to secure the suture. Finally, cut the suture at the tissue edge without leaving any trailing tail or knot.

Why use a barbed suture? The advantages of using absorbable barbed suture include:

- elimination of knot tying

- shorter closure time

- better tension distribution throughout the wound.

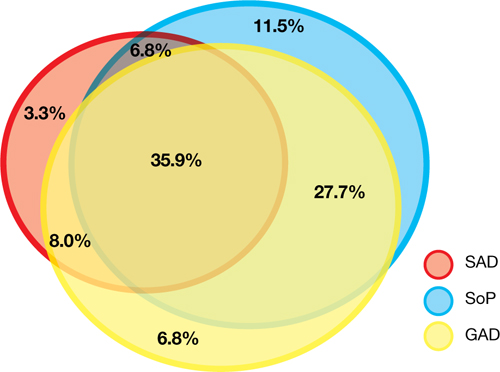

Close the seromuscularis layer in a hemostatic baseball stitch fashion to minimize suture exposure and subsequent adhesions (FIGURE). Use of the suprapubic port for the needle retrieval device facilitates placement of the alternating “inside-out” baseball stitch (see VIDEO 3).

FIGURE Use of a hemostatic baseball stitch (with absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture) to close the seromuscularis layer of the uterus, thereby minimizing suture exposure and subsequent adhesions.

Morcellation

Mechanically morcellate the fibroids through the suprapubic port site. We use an electrical morcellator (Karl Storz Endoscopy). In cases of massive fibroids (>15 cm) we utilize cold- knife morcellation with a # 10 scalpel through an extended 3-cm suprapubic incision with a vertical fascial incision protected by a self-retaining wound retractor. It is important to be vigilant to remove all fibroid pieces as postoperative disseminated leiomyomatosis is well described.

Adhesion prevention

Myomectomy is notorious for creating dense and challenging postoperative adhesions. Given the high rate of repeat surgery for patients undergoing the procedure, anything you can do to limit the adhesion load will be appreciated by both your patient and her next surgeon. Without exception, the most important adhesion-prevention strategy is meticulous attention to tissue handling and hemostasis. In general, laparoscopy leads to fewer adhesions than laparotomy, but a bloody field and raw uterine serosa will create an environment ripe for adhesions regardless of surgical approach. If the operative field is dry, use commercial adhesion prevention aids according to manufacturers’ recommendations.

- Use preoperative MRI to tailor your surgical approach

- When menorrhagia is a presenting symptom, assess the endometrial cavity preoperatively and consider combining the laparoscopic myomectomy with hysteroscopic myomectomy

- Minimize blood loss with vasopressin or a laparoscopic tourniquet

- Utilize a transverse uterine incision and a lateral suturing technique

- Use delayed absorbable barbed suture to close the myometrial defect

- Bury the seromuscular closure suture by utilizing an “inside-out” baseball stitch

- If the risk for postoperative cavitary adhesions is high, consider postoperative balloon placement with close postoperative follow-up

- Advise patients to wait 6 months prior to attempting to conceive and have a low threshold for scheduled cesarean delivery to minimize the risk of uterine rupture

Concluding thoughts, from experience

Laparoscopic myomectomy is a challenging yet rewarding procedure. For essential points to our approach, see “Laparoscopic myomectomy: Key takeaways” on this page.

Other important things to keep in mind:

- Fibroid presentation is as varied as the women who have them—meticulous preoperative preparation is an absolute must.

- Utilize well-established approaches to preventing blood loss, removing fibroids, and repairing the uterine defects. The accomplished gynecologic laparoscopist will be successful in the majority of cases.

- Practice suturing in a box-trainer setting before taking on initial cases. Early cases should focus on straightforward subserosal fibroids and, as skills progress, more and more difficult cases will become reasonable.

- Do not place any hard and fast limit on either the number or size of fibroids you are willing to remove laparoscopically. Rather, rely on sound surgical judgment, an honest assessment of your limitations, and a healthy dose of caution as you approach every new patient. Never sacrifice the quality of your repair for a less invasive approach to surgery.

Laparoscopic myomectomy: 8 pearls

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH (March 2010)

Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, March 2010)

Barbed suture, now in the toolbox of minimally invasive gyn surgery

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH; James A. Greenberg, MD (September 2009)

When necessity calls for treating uterine fibroids

William H. Parker, MD (Surgical Techniques, June 2008)

Advising your patients–Uterine fibroids: Childbearing, cancer, and hormone effects

William H. Parker, MD (May 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(2):393-406.

3. Stringer NH, Walker JC, Meyer PM. Comparison of 49 laparoscopic myomec- tomies and 49 open myomectomies. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(4):457-464.

4. Bulletti C, Polli V, Negrini V, Giacomucci E, Flamigni C. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic myomectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3(4):533-536.

5. Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, Vishne T, Kravarusic D, Dreznik Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140(3):285-288.

6. Frederick J, Fletcher H, Simeon D, Mullings A, Hardie M. Intramyometrial vasopressin as a haemostatic agent during myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(5):435-437.

7. Taylor A, Sharma M, Tsirkas P, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Setchell M, Magos A. Reducing blood loss at open myomectomy using triple tourniquets: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005;112(3):340-345.

8. Burbank F, Hutchins FL, Jr. Uterine artery occlusion by embolization or surgery for the treatment of fibroids: A unifying hypothesis-transient uterine ischemia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(suppl 4):S1-S49.

Watch 3 videos illustrating laparoscopic myomectomy

These videos were provided by Gaby Moawad, MD, and James Robinson, MD, MS.

By age 50, almost 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women will have a uterine leiomyoma.1 These benign, hormone-sensitive neoplasms1 are asymptomatic in the majority of women, but they can cause infertility, abnormal uterine bleeding, and bulk symptoms.2

When symptomatic, fibroids are amenable to multiple management options, ranging from expectant management to medical therapy to uterine artery embolization to myomectomy to hysterectomy. Myomectomy remains the surgical option of choice for women with symptomatic fibroids who wish to retain their fertility. It is also an option for some women who may not desire fertility retention but who do wish to maintain their uterus.

Compared with traditional myomectomy by laparotomy, laparoscopic myomectomy offers the advantages of:

- less blood loss

- less postoperative pain

- less postoperative adhesions formation

- faster recovery

- better cosmesis.3,4

Current technology makes performing laparoscopic myomectomy by either “straight-stick” or robotic assistance a viable option for most women.

In this article, we describe our technique in performing straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative evaluation: The first key to success

Laparoscopic myomectomy is an advanced, delicate, and challenging surgery. Preoperative evaluation is integral to its planning and a successful outcome.

Imaging

We recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a standard order whenever a laparoscopic approach to myomectomy is being considered, for several reasons. First, MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast allows for a precise map of the location of fibroids in relation to the myometrium and the uterine cavity. Reviewing the MRI results with the patient preoperatively gives both you and the patient a clearer picture of the challenges ahead. Patients tell us they appreciate these easier-to-understand images of their anatomy and, in cases when the decision is made to proceed abdominally, it is more clear to the patient why the decision is being made.

Surgically, the MRI helps compensate for the lack of tactile feedback when faced with deep intramural fibroids laparoscopically. The MRI also helps avoid operative surprises. Experience teaches us that, when relying on transvaginal ultrasound alone, adenomyotic regions can be identified mistakenly as fibroids. Preoperative MRI can help you avoid this discovery at the time of surgery.

A flexible office hysteroscopy serves as an adjunct to MRI for precise preoperative cavitary evaluation, especially when fibroids are present in close proximity to the endometrial cavity or the patient reports menorrhagia as a component of her symptomatology. When small submucosal fibroids exist in addition to larger fibroids, we frequently perform a combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic approach to myomectomy.

Although bowel preparation does not diminish complications from bowel surgery or improve outcome,5 we generally use laxative suppositories the night prior to surgery to improve access to the posterior cul-de-sac and reduce bulk resulting from a sigmoid full of feces.

Preoperative laboratory evaluation should always include complete blood count, beta hCG, blood type testing, and antibody screen. In patients with known anemia or large intramural fibroids, we typically match the patient for 2 units of packed red blood cells. Additionally, if significant blood loss is anticipated, cell saver technology can be modified to accommodate a laparoscopic suction tip, allowing the patient’s own blood to be collected and readministered.

Aside from the standard risks of surgery, including bleeding, transfusion, infection, and injury to adjacent organs, myomectomy has its own unique risks that need to be made clear to patients preoperatively.

Surgery timing. Initially, women with symptomatic fibroids are at significant risk for developing more fibroids in the future. In fact, 25% of women who undergo myomectomy will require a second surgery at some point in their lives to address recurrent symptoms.1 If women are young, not yet ready to conceive, and are still relatively asymptomatic, waiting to perform myomectomy may be the most prudent course.

Future uterine rupture. There are no good myomectomy data to guide us with respect to the risk of uterine rupture at future pregnancy. When we perform deep intramural myomectomy (regardless of endometrial disruption), we extrapolate from classical cesarean section data and counsel our patients to have planned cesarean sections for all future pregnancies. Patients are also counseled that uterine rupture has been well described after laparoscopic myomectomy prior to the onset of labor so any sudden onset of pain or bleeding during the late second or third trimester of pregnancy has to be regarded as a medical emergency.

Pregnancy. Again, no good data exist to guide us with respect to postoperative timing of future pregnancy. We typically suggest patients refrain from conceiving following myomectomy for at least 6 months. We are aware that other well-respected surgeons have different thresholds.

Reference

1. Andiani GB, Fedele L, Parazzini F, Villa L. Risk of recurrence after myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(4):385-389.

How to minimize blood loss

Blood loss during laparoscopic myomectomy generally is less than during laparotomy due to venous compression from pneumoperitoneum. However, blood loss remains a chief concern when performing laparoscopic myomectomy. A variety of techniques have been described to minimize blood loss, including injection of dilute vasopressin6 and tourniquet placement around uterine vessels.7

Injection. To temporarily minimize bleeding in the surgical field, we routinely utilize subserosal injection of dilute vasopressin (20 IU in 100 mL of normal saline) until visible vessels blanch. This practice is more effective than deep myoma or myometrial injection.

Tourniquet. We selectively use a laparoscopically placed tourniquet to compress uterine arteries at the mid-cervix during surgery. One approach is as follows (see VIDEO 1):

- Open windows in bilateral broad ligaments lateral to the uterine pedicles and medial to the ureters.

- Pass the end of a 14-16 French red rubber catheter through one of the low lateral port sites with the port removed.

- Tag the trailing end of the tourniquet outside the abdomen and replace the port alongside the catheter.

- Pass the end of the catheter down through the ipsilateral broad ligament window and under the posterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter up through the contralateral broad ligament window and over the anterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter through each of the broad ligament windows a second time and then out through the contralateral port site.

- Pull the tourniquet tight from both port sites (which will occlude the uterine arteries). Place Kelly clamps on the catheter ends where they exit the port sites to maintain tension until the end of the uterine repair.

Lateral ports can still be utilized with the tourniquet in place.

Permanent occlusion. In women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy who have completed child bearing, we advocate permanent uterine artery occlusion at the origin of the uterine arteries retroperitoneally. This can be performed in a number of ways— utilizing clips, suture, or transection. Uterine artery occlusion not only leads to less operative blood loss but preliminary studies also suggest it decreases the risk of fibroid recurrence.8

After the patient is prepped and draped in low lithotomy position with her arms tucked at her sides, drain the bladder with an indwelling catheter. Insert a uterine manipulator, such as the VCare (Conmed Corporation), into the uterus.

Obtain umbilical entry for a 30° optic scope, and place the patient in steep Trendelenburg position. We use two 5-mm lateral ports and one 12-mm suprapubic port. The level of placement of the lateral ports is tailored to the size of the fibroids; it can be anywhere from the level of the anterior iliac spine to the level of the umbilicus for fibroids contained in the pelvis or in the abdomen, respectively.

Uterine incision

After vasopressin injection, tourniquet placement, or permanent uterine artery occlusion is performed as described above, we advocate a transverse uterine incision. We do so mainly because:

- The transverse incision runs parallel to the arcuate vessels of the myometrium, leading to less bleeding.

- We suture from the lateral ports so the transverse incision facilitates a more ergonomic repair.

Perform the uterine incision (we use the Harmonic Ace [Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc]) through the uterine serosa deep toward the myoma. Incision size should be appropriate to the diameter of the fibroid; smaller incisions result in unnecessary struggling during enucleation of the fibroid. Incision depth should reach the fibroid capsule, and this incision should be developed over the entire fibroid. Tunneling in the myometrium is undesirable and should be avoided because it increases myometrial injury as well as the risk of hematoma.

Fibroid enucleation

Once the initial uterine incision is complete, enucleate the fibroid using a combination of traction, countertraction, sharp, and blunt dissection (see VIDEO 2). Pearls to successful enucleation include:

- Maintain traction and countertraction when cutting tissue. This helps to identify appropriate planes and allows tissue to separate quickly, minimizing thermal energy spread.

- Replace the tenaculum or myoma screw regularly at the border of the myoma and myometrium. The ultrasonic scalpel blade can be drilled into the myoma in order to create traction on the myoma.

- Bluntly peel tissue from the myoma outward. Ideally all myometrium and vessels should stay with the uterus. A properly enucleated fibroid will be pearly in appearance and avascular.

- Be particularly careful when in contact with the endometrium. Even submucous fibroids can be enucleated regularly without entering the endometrial cavity.

Uterine repair

If the endometrial cavity is inadvertently entered, close the defect (we use a 2-0 monocryl or Vicryl suture). Next, imbricate the endometrium over with successive layers, taking special care not to pass a needle into the endometrial cavity. In cases in which significant endometrial disruption cannot be avoided, use a postoperative intrauterine balloon stent. This is placed postoperatively and left in place for 2 weeks. To stimulate endometrial proliferation, we prescribe oral estradiol 1 mg twice per day for 4 weeks. Following endometrial stimulation, we prescribe a 10-day progestin withdrawal and ask the patient to return to the office for a flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy following her first menses to ensure cavitary integrity.

Once fibroid enucleation is complete, perform a multilayer closure of the defect using an absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture (V-Loc, Covidien). Eliminate all dead space in the closure. The last two throws of each barbed suture should be in the direction of the prior two throws to secure the suture. Finally, cut the suture at the tissue edge without leaving any trailing tail or knot.

Why use a barbed suture? The advantages of using absorbable barbed suture include:

- elimination of knot tying

- shorter closure time

- better tension distribution throughout the wound.

Close the seromuscularis layer in a hemostatic baseball stitch fashion to minimize suture exposure and subsequent adhesions (FIGURE). Use of the suprapubic port for the needle retrieval device facilitates placement of the alternating “inside-out” baseball stitch (see VIDEO 3).

FIGURE Use of a hemostatic baseball stitch (with absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture) to close the seromuscularis layer of the uterus, thereby minimizing suture exposure and subsequent adhesions.

Morcellation

Mechanically morcellate the fibroids through the suprapubic port site. We use an electrical morcellator (Karl Storz Endoscopy). In cases of massive fibroids (>15 cm) we utilize cold- knife morcellation with a # 10 scalpel through an extended 3-cm suprapubic incision with a vertical fascial incision protected by a self-retaining wound retractor. It is important to be vigilant to remove all fibroid pieces as postoperative disseminated leiomyomatosis is well described.

Adhesion prevention

Myomectomy is notorious for creating dense and challenging postoperative adhesions. Given the high rate of repeat surgery for patients undergoing the procedure, anything you can do to limit the adhesion load will be appreciated by both your patient and her next surgeon. Without exception, the most important adhesion-prevention strategy is meticulous attention to tissue handling and hemostasis. In general, laparoscopy leads to fewer adhesions than laparotomy, but a bloody field and raw uterine serosa will create an environment ripe for adhesions regardless of surgical approach. If the operative field is dry, use commercial adhesion prevention aids according to manufacturers’ recommendations.

- Use preoperative MRI to tailor your surgical approach

- When menorrhagia is a presenting symptom, assess the endometrial cavity preoperatively and consider combining the laparoscopic myomectomy with hysteroscopic myomectomy

- Minimize blood loss with vasopressin or a laparoscopic tourniquet

- Utilize a transverse uterine incision and a lateral suturing technique

- Use delayed absorbable barbed suture to close the myometrial defect

- Bury the seromuscular closure suture by utilizing an “inside-out” baseball stitch

- If the risk for postoperative cavitary adhesions is high, consider postoperative balloon placement with close postoperative follow-up

- Advise patients to wait 6 months prior to attempting to conceive and have a low threshold for scheduled cesarean delivery to minimize the risk of uterine rupture

Concluding thoughts, from experience

Laparoscopic myomectomy is a challenging yet rewarding procedure. For essential points to our approach, see “Laparoscopic myomectomy: Key takeaways” on this page.

Other important things to keep in mind:

- Fibroid presentation is as varied as the women who have them—meticulous preoperative preparation is an absolute must.

- Utilize well-established approaches to preventing blood loss, removing fibroids, and repairing the uterine defects. The accomplished gynecologic laparoscopist will be successful in the majority of cases.

- Practice suturing in a box-trainer setting before taking on initial cases. Early cases should focus on straightforward subserosal fibroids and, as skills progress, more and more difficult cases will become reasonable.

- Do not place any hard and fast limit on either the number or size of fibroids you are willing to remove laparoscopically. Rather, rely on sound surgical judgment, an honest assessment of your limitations, and a healthy dose of caution as you approach every new patient. Never sacrifice the quality of your repair for a less invasive approach to surgery.

Laparoscopic myomectomy: 8 pearls

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH (March 2010)

Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, March 2010)

Barbed suture, now in the toolbox of minimally invasive gyn surgery

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH; James A. Greenberg, MD (September 2009)

When necessity calls for treating uterine fibroids

William H. Parker, MD (Surgical Techniques, June 2008)

Advising your patients–Uterine fibroids: Childbearing, cancer, and hormone effects

William H. Parker, MD (May 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Watch 3 videos illustrating laparoscopic myomectomy

These videos were provided by Gaby Moawad, MD, and James Robinson, MD, MS.

By age 50, almost 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women will have a uterine leiomyoma.1 These benign, hormone-sensitive neoplasms1 are asymptomatic in the majority of women, but they can cause infertility, abnormal uterine bleeding, and bulk symptoms.2

When symptomatic, fibroids are amenable to multiple management options, ranging from expectant management to medical therapy to uterine artery embolization to myomectomy to hysterectomy. Myomectomy remains the surgical option of choice for women with symptomatic fibroids who wish to retain their fertility. It is also an option for some women who may not desire fertility retention but who do wish to maintain their uterus.

Compared with traditional myomectomy by laparotomy, laparoscopic myomectomy offers the advantages of:

- less blood loss

- less postoperative pain

- less postoperative adhesions formation

- faster recovery

- better cosmesis.3,4

Current technology makes performing laparoscopic myomectomy by either “straight-stick” or robotic assistance a viable option for most women.

In this article, we describe our technique in performing straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative evaluation: The first key to success

Laparoscopic myomectomy is an advanced, delicate, and challenging surgery. Preoperative evaluation is integral to its planning and a successful outcome.

Imaging

We recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a standard order whenever a laparoscopic approach to myomectomy is being considered, for several reasons. First, MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast allows for a precise map of the location of fibroids in relation to the myometrium and the uterine cavity. Reviewing the MRI results with the patient preoperatively gives both you and the patient a clearer picture of the challenges ahead. Patients tell us they appreciate these easier-to-understand images of their anatomy and, in cases when the decision is made to proceed abdominally, it is more clear to the patient why the decision is being made.

Surgically, the MRI helps compensate for the lack of tactile feedback when faced with deep intramural fibroids laparoscopically. The MRI also helps avoid operative surprises. Experience teaches us that, when relying on transvaginal ultrasound alone, adenomyotic regions can be identified mistakenly as fibroids. Preoperative MRI can help you avoid this discovery at the time of surgery.

A flexible office hysteroscopy serves as an adjunct to MRI for precise preoperative cavitary evaluation, especially when fibroids are present in close proximity to the endometrial cavity or the patient reports menorrhagia as a component of her symptomatology. When small submucosal fibroids exist in addition to larger fibroids, we frequently perform a combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic approach to myomectomy.

Although bowel preparation does not diminish complications from bowel surgery or improve outcome,5 we generally use laxative suppositories the night prior to surgery to improve access to the posterior cul-de-sac and reduce bulk resulting from a sigmoid full of feces.

Preoperative laboratory evaluation should always include complete blood count, beta hCG, blood type testing, and antibody screen. In patients with known anemia or large intramural fibroids, we typically match the patient for 2 units of packed red blood cells. Additionally, if significant blood loss is anticipated, cell saver technology can be modified to accommodate a laparoscopic suction tip, allowing the patient’s own blood to be collected and readministered.

Aside from the standard risks of surgery, including bleeding, transfusion, infection, and injury to adjacent organs, myomectomy has its own unique risks that need to be made clear to patients preoperatively.

Surgery timing. Initially, women with symptomatic fibroids are at significant risk for developing more fibroids in the future. In fact, 25% of women who undergo myomectomy will require a second surgery at some point in their lives to address recurrent symptoms.1 If women are young, not yet ready to conceive, and are still relatively asymptomatic, waiting to perform myomectomy may be the most prudent course.

Future uterine rupture. There are no good myomectomy data to guide us with respect to the risk of uterine rupture at future pregnancy. When we perform deep intramural myomectomy (regardless of endometrial disruption), we extrapolate from classical cesarean section data and counsel our patients to have planned cesarean sections for all future pregnancies. Patients are also counseled that uterine rupture has been well described after laparoscopic myomectomy prior to the onset of labor so any sudden onset of pain or bleeding during the late second or third trimester of pregnancy has to be regarded as a medical emergency.

Pregnancy. Again, no good data exist to guide us with respect to postoperative timing of future pregnancy. We typically suggest patients refrain from conceiving following myomectomy for at least 6 months. We are aware that other well-respected surgeons have different thresholds.

Reference

1. Andiani GB, Fedele L, Parazzini F, Villa L. Risk of recurrence after myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(4):385-389.

How to minimize blood loss

Blood loss during laparoscopic myomectomy generally is less than during laparotomy due to venous compression from pneumoperitoneum. However, blood loss remains a chief concern when performing laparoscopic myomectomy. A variety of techniques have been described to minimize blood loss, including injection of dilute vasopressin6 and tourniquet placement around uterine vessels.7

Injection. To temporarily minimize bleeding in the surgical field, we routinely utilize subserosal injection of dilute vasopressin (20 IU in 100 mL of normal saline) until visible vessels blanch. This practice is more effective than deep myoma or myometrial injection.

Tourniquet. We selectively use a laparoscopically placed tourniquet to compress uterine arteries at the mid-cervix during surgery. One approach is as follows (see VIDEO 1):

- Open windows in bilateral broad ligaments lateral to the uterine pedicles and medial to the ureters.

- Pass the end of a 14-16 French red rubber catheter through one of the low lateral port sites with the port removed.

- Tag the trailing end of the tourniquet outside the abdomen and replace the port alongside the catheter.

- Pass the end of the catheter down through the ipsilateral broad ligament window and under the posterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter up through the contralateral broad ligament window and over the anterior cervix.

- Pass the end of the catheter through each of the broad ligament windows a second time and then out through the contralateral port site.

- Pull the tourniquet tight from both port sites (which will occlude the uterine arteries). Place Kelly clamps on the catheter ends where they exit the port sites to maintain tension until the end of the uterine repair.

Lateral ports can still be utilized with the tourniquet in place.

Permanent occlusion. In women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy who have completed child bearing, we advocate permanent uterine artery occlusion at the origin of the uterine arteries retroperitoneally. This can be performed in a number of ways— utilizing clips, suture, or transection. Uterine artery occlusion not only leads to less operative blood loss but preliminary studies also suggest it decreases the risk of fibroid recurrence.8

After the patient is prepped and draped in low lithotomy position with her arms tucked at her sides, drain the bladder with an indwelling catheter. Insert a uterine manipulator, such as the VCare (Conmed Corporation), into the uterus.

Obtain umbilical entry for a 30° optic scope, and place the patient in steep Trendelenburg position. We use two 5-mm lateral ports and one 12-mm suprapubic port. The level of placement of the lateral ports is tailored to the size of the fibroids; it can be anywhere from the level of the anterior iliac spine to the level of the umbilicus for fibroids contained in the pelvis or in the abdomen, respectively.

Uterine incision

After vasopressin injection, tourniquet placement, or permanent uterine artery occlusion is performed as described above, we advocate a transverse uterine incision. We do so mainly because:

- The transverse incision runs parallel to the arcuate vessels of the myometrium, leading to less bleeding.

- We suture from the lateral ports so the transverse incision facilitates a more ergonomic repair.

Perform the uterine incision (we use the Harmonic Ace [Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc]) through the uterine serosa deep toward the myoma. Incision size should be appropriate to the diameter of the fibroid; smaller incisions result in unnecessary struggling during enucleation of the fibroid. Incision depth should reach the fibroid capsule, and this incision should be developed over the entire fibroid. Tunneling in the myometrium is undesirable and should be avoided because it increases myometrial injury as well as the risk of hematoma.

Fibroid enucleation

Once the initial uterine incision is complete, enucleate the fibroid using a combination of traction, countertraction, sharp, and blunt dissection (see VIDEO 2). Pearls to successful enucleation include:

- Maintain traction and countertraction when cutting tissue. This helps to identify appropriate planes and allows tissue to separate quickly, minimizing thermal energy spread.

- Replace the tenaculum or myoma screw regularly at the border of the myoma and myometrium. The ultrasonic scalpel blade can be drilled into the myoma in order to create traction on the myoma.

- Bluntly peel tissue from the myoma outward. Ideally all myometrium and vessels should stay with the uterus. A properly enucleated fibroid will be pearly in appearance and avascular.

- Be particularly careful when in contact with the endometrium. Even submucous fibroids can be enucleated regularly without entering the endometrial cavity.

Uterine repair

If the endometrial cavity is inadvertently entered, close the defect (we use a 2-0 monocryl or Vicryl suture). Next, imbricate the endometrium over with successive layers, taking special care not to pass a needle into the endometrial cavity. In cases in which significant endometrial disruption cannot be avoided, use a postoperative intrauterine balloon stent. This is placed postoperatively and left in place for 2 weeks. To stimulate endometrial proliferation, we prescribe oral estradiol 1 mg twice per day for 4 weeks. Following endometrial stimulation, we prescribe a 10-day progestin withdrawal and ask the patient to return to the office for a flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy following her first menses to ensure cavitary integrity.

Once fibroid enucleation is complete, perform a multilayer closure of the defect using an absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture (V-Loc, Covidien). Eliminate all dead space in the closure. The last two throws of each barbed suture should be in the direction of the prior two throws to secure the suture. Finally, cut the suture at the tissue edge without leaving any trailing tail or knot.

Why use a barbed suture? The advantages of using absorbable barbed suture include:

- elimination of knot tying

- shorter closure time

- better tension distribution throughout the wound.

Close the seromuscularis layer in a hemostatic baseball stitch fashion to minimize suture exposure and subsequent adhesions (FIGURE). Use of the suprapubic port for the needle retrieval device facilitates placement of the alternating “inside-out” baseball stitch (see VIDEO 3).

FIGURE Use of a hemostatic baseball stitch (with absorbable, unidirectional barbed suture) to close the seromuscularis layer of the uterus, thereby minimizing suture exposure and subsequent adhesions.

Morcellation

Mechanically morcellate the fibroids through the suprapubic port site. We use an electrical morcellator (Karl Storz Endoscopy). In cases of massive fibroids (>15 cm) we utilize cold- knife morcellation with a # 10 scalpel through an extended 3-cm suprapubic incision with a vertical fascial incision protected by a self-retaining wound retractor. It is important to be vigilant to remove all fibroid pieces as postoperative disseminated leiomyomatosis is well described.

Adhesion prevention

Myomectomy is notorious for creating dense and challenging postoperative adhesions. Given the high rate of repeat surgery for patients undergoing the procedure, anything you can do to limit the adhesion load will be appreciated by both your patient and her next surgeon. Without exception, the most important adhesion-prevention strategy is meticulous attention to tissue handling and hemostasis. In general, laparoscopy leads to fewer adhesions than laparotomy, but a bloody field and raw uterine serosa will create an environment ripe for adhesions regardless of surgical approach. If the operative field is dry, use commercial adhesion prevention aids according to manufacturers’ recommendations.

- Use preoperative MRI to tailor your surgical approach

- When menorrhagia is a presenting symptom, assess the endometrial cavity preoperatively and consider combining the laparoscopic myomectomy with hysteroscopic myomectomy

- Minimize blood loss with vasopressin or a laparoscopic tourniquet

- Utilize a transverse uterine incision and a lateral suturing technique

- Use delayed absorbable barbed suture to close the myometrial defect

- Bury the seromuscular closure suture by utilizing an “inside-out” baseball stitch

- If the risk for postoperative cavitary adhesions is high, consider postoperative balloon placement with close postoperative follow-up

- Advise patients to wait 6 months prior to attempting to conceive and have a low threshold for scheduled cesarean delivery to minimize the risk of uterine rupture

Concluding thoughts, from experience

Laparoscopic myomectomy is a challenging yet rewarding procedure. For essential points to our approach, see “Laparoscopic myomectomy: Key takeaways” on this page.

Other important things to keep in mind:

- Fibroid presentation is as varied as the women who have them—meticulous preoperative preparation is an absolute must.

- Utilize well-established approaches to preventing blood loss, removing fibroids, and repairing the uterine defects. The accomplished gynecologic laparoscopist will be successful in the majority of cases.

- Practice suturing in a box-trainer setting before taking on initial cases. Early cases should focus on straightforward subserosal fibroids and, as skills progress, more and more difficult cases will become reasonable.

- Do not place any hard and fast limit on either the number or size of fibroids you are willing to remove laparoscopically. Rather, rely on sound surgical judgment, an honest assessment of your limitations, and a healthy dose of caution as you approach every new patient. Never sacrifice the quality of your repair for a less invasive approach to surgery.

Laparoscopic myomectomy: 8 pearls

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH (March 2010)

Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, March 2010)

Barbed suture, now in the toolbox of minimally invasive gyn surgery

Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH; James A. Greenberg, MD (September 2009)

When necessity calls for treating uterine fibroids

William H. Parker, MD (Surgical Techniques, June 2008)

Advising your patients–Uterine fibroids: Childbearing, cancer, and hormone effects

William H. Parker, MD (May 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(2):393-406.

3. Stringer NH, Walker JC, Meyer PM. Comparison of 49 laparoscopic myomec- tomies and 49 open myomectomies. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(4):457-464.

4. Bulletti C, Polli V, Negrini V, Giacomucci E, Flamigni C. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic myomectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3(4):533-536.

5. Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, Vishne T, Kravarusic D, Dreznik Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140(3):285-288.

6. Frederick J, Fletcher H, Simeon D, Mullings A, Hardie M. Intramyometrial vasopressin as a haemostatic agent during myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(5):435-437.

7. Taylor A, Sharma M, Tsirkas P, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Setchell M, Magos A. Reducing blood loss at open myomectomy using triple tourniquets: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005;112(3):340-345.

8. Burbank F, Hutchins FL, Jr. Uterine artery occlusion by embolization or surgery for the treatment of fibroids: A unifying hypothesis-transient uterine ischemia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(suppl 4):S1-S49.

1. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(2):393-406.

3. Stringer NH, Walker JC, Meyer PM. Comparison of 49 laparoscopic myomec- tomies and 49 open myomectomies. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(4):457-464.

4. Bulletti C, Polli V, Negrini V, Giacomucci E, Flamigni C. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic myomectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3(4):533-536.

5. Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, Vishne T, Kravarusic D, Dreznik Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140(3):285-288.

6. Frederick J, Fletcher H, Simeon D, Mullings A, Hardie M. Intramyometrial vasopressin as a haemostatic agent during myomectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(5):435-437.

7. Taylor A, Sharma M, Tsirkas P, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Setchell M, Magos A. Reducing blood loss at open myomectomy using triple tourniquets: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005;112(3):340-345.

8. Burbank F, Hutchins FL, Jr. Uterine artery occlusion by embolization or surgery for the treatment of fibroids: A unifying hypothesis-transient uterine ischemia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(suppl 4):S1-S49.

DEXA screening—are we doing too much?

Reconsider the intervals at which you recommend rescreening for osteoporosis; for post-menopausal women with a baseline of normal bone mineral density (BMD) or mild osteopenia, a 15-year interval is probably sufficient.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single cohort study

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, et al. Bone density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;366: 225-233

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE