User login

Factors Tied to Photoprotection ID'd for Organ Recipients

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Factors Tied to Photoprotection ID'd for Organ Recipients

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Publications

Page Number

4

Legacy Keywords

photoprotection, skin cancer, aging skin

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Page Number

4

Page Number

4

Publications

Publications

Article Type

Display Headline

Factors Tied to Photoprotection ID'd for Organ Recipients

Display Headline

Factors Tied to Photoprotection ID'd for Organ Recipients

Legacy Keywords

photoprotection, skin cancer, aging skin

Legacy Keywords

photoprotection, skin cancer, aging skin

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Neurotoxin Treatment of the Upper Face

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Neurotoxin Treatment of the Upper Face

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

427-432

Legacy Keywords

neurotoxin injections of the face, Botulinum toxin type A preparations, topical and injectable forms of botox, injection techniques for the upper face, botulinum toxin mechanism of action,

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

427-432

Page Number

427-432

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Neurotoxin Treatment of the Upper Face

Display Headline

Neurotoxin Treatment of the Upper Face

Legacy Keywords

neurotoxin injections of the face, Botulinum toxin type A preparations, topical and injectable forms of botox, injection techniques for the upper face, botulinum toxin mechanism of action,

Legacy Keywords

neurotoxin injections of the face, Botulinum toxin type A preparations, topical and injectable forms of botox, injection techniques for the upper face, botulinum toxin mechanism of action,

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

An Overview of Injectable Fillers With Special Consideration to the Periorbital Area

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

An Overview of Injectable Fillers With Special Consideration to the Periorbital Area

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

421-426

Legacy Keywords

soft tissue augmentation with temporary fillers, history of injectable fillers in dermatology, injectable facial fillers, injection technique for dermal fillers, ideal characteristics of facial fillers, synthetic extracellular matrix materials

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

421-426

Page Number

421-426

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

An Overview of Injectable Fillers With Special Consideration to the Periorbital Area

Display Headline

An Overview of Injectable Fillers With Special Consideration to the Periorbital Area

Legacy Keywords

soft tissue augmentation with temporary fillers, history of injectable fillers in dermatology, injectable facial fillers, injection technique for dermal fillers, ideal characteristics of facial fillers, synthetic extracellular matrix materials

Legacy Keywords

soft tissue augmentation with temporary fillers, history of injectable fillers in dermatology, injectable facial fillers, injection technique for dermal fillers, ideal characteristics of facial fillers, synthetic extracellular matrix materials

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

Devices for Rejuvenation of the Aging Face

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Devices for Rejuvenation of the Aging Face

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

412-418

Legacy Keywords

photorejuvenation devices, ablative resurfacing techniques, nonablative resurfacing techniques, reversing signs of aging, treating signs of skin aging, technology and facial rejuvenation

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

412-418

Page Number

412-418

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Devices for Rejuvenation of the Aging Face

Display Headline

Devices for Rejuvenation of the Aging Face

Legacy Keywords

photorejuvenation devices, ablative resurfacing techniques, nonablative resurfacing techniques, reversing signs of aging, treating signs of skin aging, technology and facial rejuvenation

Legacy Keywords

photorejuvenation devices, ablative resurfacing techniques, nonablative resurfacing techniques, reversing signs of aging, treating signs of skin aging, technology and facial rejuvenation

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

Disallow All Ads

Article PDF Media

Document

Vitamin-Based Cosmeceuticals

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Vitamin-Based Cosmeceuticals

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

405-410

Legacy Keywords

cosmeceutical product testing and development, antiaging skin care market, botanicals and vitamins in cosmetic products, vitamins in topical skin care formulations

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

405-410

Page Number

405-410

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Vitamin-Based Cosmeceuticals

Display Headline

Vitamin-Based Cosmeceuticals

Legacy Keywords

cosmeceutical product testing and development, antiaging skin care market, botanicals and vitamins in cosmetic products, vitamins in topical skin care formulations

Legacy Keywords

cosmeceutical product testing and development, antiaging skin care market, botanicals and vitamins in cosmetic products, vitamins in topical skin care formulations

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

Mechanisms of Skin Aging

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Mechanisms of Skin Aging

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

399-402

Legacy Keywords

extrinsic signs of aging, intrinsic signs of aging, extrinsic facial aging, free radical theory of aging, UV radiation and skin aging, photoaging

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

399-402

Page Number

399-402

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Mechanisms of Skin Aging

Display Headline

Mechanisms of Skin Aging

Legacy Keywords

extrinsic signs of aging, intrinsic signs of aging, extrinsic facial aging, free radical theory of aging, UV radiation and skin aging, photoaging

Legacy Keywords

extrinsic signs of aging, intrinsic signs of aging, extrinsic facial aging, free radical theory of aging, UV radiation and skin aging, photoaging

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

Plant Stem Cells and Skin Care

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Plant Stem Cells and Skin Care

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

395-396

Legacy Keywords

preparation of plant extracts, stem cell cultivation and cosmetics, berry extracts and cosmetics, stem cells and cosmeceutical ingredients

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

395-396

Page Number

395-396

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Plant Stem Cells and Skin Care

Display Headline

Plant Stem Cells and Skin Care

Legacy Keywords

preparation of plant extracts, stem cell cultivation and cosmetics, berry extracts and cosmetics, stem cells and cosmeceutical ingredients

Legacy Keywords

preparation of plant extracts, stem cell cultivation and cosmetics, berry extracts and cosmetics, stem cells and cosmeceutical ingredients

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

Training in Cosmetic Dermatology [editorial]

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Training in Cosmetic Dermatology [editorial]

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

392-393

Legacy Keywords

development of cosmetic procedures, dermatology residents in training, dermatologists and technology development, cosmetic dermatology training programs, teaching dermatologic techniques

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

392-393

Page Number

392-393

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Training in Cosmetic Dermatology [editorial]

Display Headline

Training in Cosmetic Dermatology [editorial]

Legacy Keywords

development of cosmetic procedures, dermatology residents in training, dermatologists and technology development, cosmetic dermatology training programs, teaching dermatologic techniques

Legacy Keywords

development of cosmetic procedures, dermatology residents in training, dermatologists and technology development, cosmetic dermatology training programs, teaching dermatologic techniques

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document

Reasons for Discontinuation Vary by Psoriasis Treatment

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Reasons for Discontinuation Vary by Psoriasis Treatment

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Publications

Page Number

3

Legacy Keywords

psoriasis treatment, plaque psoriasis

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Issue

Cutis - 90(2)

Page Number

3

Page Number

3

Publications

Publications

Article Type

Display Headline

Reasons for Discontinuation Vary by Psoriasis Treatment

Display Headline

Reasons for Discontinuation Vary by Psoriasis Treatment

Legacy Keywords

psoriasis treatment, plaque psoriasis

Legacy Keywords

psoriasis treatment, plaque psoriasis

Article Source

Citation Override

Originally published in Cosmetic Dermatology

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

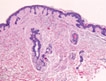

Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

119, 123-124

Legacy Keywords

primary systemic amyloidosis and underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, primary systemic amyloidosis and organ involvement, histopathology of primary systemic amyloidosis,

Sections

Article PDF

Article PDF

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Issue

Cutis - 90(3)

Page Number

119, 123-124

Page Number

119, 123-124

Publications

Publications

Topics

Article Type

Display Headline

Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Display Headline

Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Legacy Keywords

primary systemic amyloidosis and underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, primary systemic amyloidosis and organ involvement, histopathology of primary systemic amyloidosis,

Legacy Keywords

primary systemic amyloidosis and underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, primary systemic amyloidosis and organ involvement, histopathology of primary systemic amyloidosis,

Sections

Article Source

PURLs Copyright

Inside the Article

Article PDF Media

Document