User login

Onychomycosis: A simpler in-office technique for sampling specimens

Background In onychomycosis, proper specimen collection is essential for an accurate diagnosis and initiation of appropriate therapy. Several techniques and locations have been suggested for specimen collection.

Objective To investigate the optimal technique of fungal sampling in onychomycosis.

Methods We reexamined 106 patients with distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails. (The diagnosis had previously been confirmed by a laboratory mycological examination—both potassium hydroxide [KOH] test and fungal culture—of samples obtained by the proximal sampling approach.) We collected fungal specimens from the distal nail bed first, and later from the distal underside of the nail plate. The collected specimens underwent laboratory mycological examination.

Results KOH testing was positive in 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed and only in 60 (56.6%) from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); cultures were positive in 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations showed positive KOH test results in 92 (86.8%) of the 106 patients and positive cultures in 100 (94.3%) patients.

Conclusions Based on our study, we suggest that in cases of suspected DLSO, material should be obtained by scraping nail material from the distal underside of the nail and then collecting all the material from the distal part of the nail bed.

When assessing possible onychomycosis, conventional practice is to take samples from the most proximal infected area. But this approach is usually technically difficult and may cause discomfort to patients.1-6 We therefore sought to determine the optimal location for fungal sampling from the distal part of the affected nail.

Methods

To assess the accuracy of distal sampling in diagnosing distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails, we reevaluated 106 patients with DLSO previously confirmed by microscopic visualization of fungi in potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and by fungal culture of specimens obtained using the proximal sampling approach.

Before we obtained our samples, we cleaned the nails with alcohol and pared the most distal part of the nails in an effort to eliminate contaminant molds and bacteria. Using a 1- or 2-mm curette, we took specimens first from the distal nail bed and, second, from the distal underside of the nail plate ( FIGURE ). We separated specimens for use in either direct KOH visualization or in fungal culture using Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar (Novamed; Jerusalem, Israel), which contains chloramphenicol or streptomycin and penicillin to prevent contamination.

FIGURE

Distal sampling for distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis

Using a 2-mm curette, we collected specimens from the distal nail bed first (A), and then from the distal underside of the nail plate (B). However, our recommendation for clinical practice is to reverse this order of sampling to collect all possible material.

Statistical analyses

We recorded sociodemographic characteristics and fungal culture results in basic descriptive (prevalence) tables. In univariate analysis, we used t-tests to compare the means of continuous variables (eg, age, duration of fungal infection). To assess the distribution of categorical parameters (eg, sex) and to gauge the efficacy of the different probing techniques, we used chi-square (χ2) tests. We analyzed coded data using SPSS (Chicago, IL) for Windows software, version 12.

We conducted the study according to the rules of the local Helsinki Committee.

Results

We examined 106 patients with DLSO, of which 65 (61.3%) were male and 41 (38.7%) were female, ages 23 to 72 years (mean age, 44.6). The duration of fungal infection ranged from 3 to 30 years, with a mean of 14.9 years. In 70.8% of cases, the infection involved the first toenail. Duration of the fungal disease did not differ significantly between the sexes.

KOH test results were positive for 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed, and for only 60 (56.6%) specimens from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); culture results were positive for 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations (all positive samples from the nail bed, plus positive samples from the nail underside when results from the nail bed were negative) yielded confirmation with KOH testing in 92 (86.8%) patients and with culture in 100 (94.3%) patients. There were no statistically significant differences between the combined results of both locations and the results from the distal nail bed alone (KOH, P=.143; culture, P=.149) ( TABLE ).

TABLE

Accuracy of distal sampling in 106 patients with confirmed DLSO

| Nail bed | Underside of nail plate | P value | Combined results | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive KOH | 84 (79.2%) | 60 (56.65%) | .0007 | 92 (86.8%) | .143 |

| Positive culture | 93 (87.7%) | 76 (71.7%) | .0063 | 100 (94.3%) | .149 |

| *Differences between results from sampling the nail bed alone and results from combined nail bed and nail plate sampling were not statistically significant. DLSO, distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis; KOH, potassium hydroxide. | |||||

Discussion

In DLSO, most dermatophyte species invade the middle and ventral layers of the nail plate adjacent to the nail bed, where the keratin is soft and close to the living cells below. In fact, the nail bed is probably the primary invasion site of dermatophytes, and it acts as a reservoir for continual reinfection of the growing nail.7 Obtaining confirmation of fungal infection before initiating antifungal treatment is the gold standard in clinical practice, given that antifungal agents have potentially serious adverse effects, that treatment is expensive, and that medicolegal issues exist.8

The standard methods used to detect a fungal nail infection are direct microscopy with KOH preparation and fungal culture. The KOH test is the simplest, least expensive method used in the detection of fungi, but it cannot identify the specific pathogen. Fungal speciation is done by culture. More accurate histopathologic evaluation is possible with periodic acid-Schiff stain, immunofluorescent microscopy with calcofluor stain, or polymerase chain reaction, but these techniques are more expensive and less feasible in outpatient clinics.9

The diagnostic accuracy of the KOH test and fungal culture ranges from 50% to 70%, depending on the experience of the laboratory technician and the methods used to collect and prepare the sample.8-10 It is better to take samples from the most proximal infected area by curettage or drilling, but this technique is usually more difficult than a distal approach, should be performed by skilled personnel, and may cause discomfort to patients.3,5,6

Our recommendation for practice. Earlier studies suggested that nail specimens should be taken from the nail bed.11-13 We sampled the nail bed first in our study because, in trying to determine an optimal location for sampling, we wanted to avoid contaminating nail-bed specimens with debris from the underside of the nail. In practice, however, we suggest that, in cases of suspected DLSO, clinicians first obtain specimens from the distal underside of the nail, and then collect all remaining material from the distal part of the nail bed. This technique is simple and can easily be performed in an office setting. If test results are negative but DLSO remains clinically likely, test a second sample after a week or 2.

CORRESPONDENCE Boaz Amichai, MD, Department of Dermatology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel; [email protected]

1. Lawry MA, Haneke E, Strobeck K, et al. Methods for diagnosing onychomycosis: a comparative study and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1112-1116.

2. Elewski BE. Diagnostic techniques for confirming onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3 pt 2):S6-S9.

3. Heikkila H. Isolation of fungi from onychomycosis-suspected nails by two methods: clipping and drilling. Mycoses. 1996;39:479-482.

4. Mochizuki T, Kawasaki M, Tanabe H, et al. A nail drilling method suitable for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Dermatol. 2005;32:108-113.

5. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Nail sampling in onychomycosis: comparative study of curettage from three sites of the infected nail. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1108-1111.

6. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

7. Hay RJ, Baran R, Haneke E. Fungal (onychomycosis) and other infections involving the nail apparatus. In: Baran R, Dawber RPR, eds. Disease of the Nails and Their Management. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Sciences Ltd; 1994: 97–134.

8. Daniel CR, 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

9. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

10. Arnold B, Kianifrad F, Tavakkol A. A comparison of KOH and culture results from two mycology laboratories for the diagnosis of onychomycosis during a randomized, multicenter clinical trial: a subset study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:421-423.

11. English MP. Nails and fungi. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:697-701.

12. Elewski BE. Clinical pearl: diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:500-501.

13. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677–678.

Background In onychomycosis, proper specimen collection is essential for an accurate diagnosis and initiation of appropriate therapy. Several techniques and locations have been suggested for specimen collection.

Objective To investigate the optimal technique of fungal sampling in onychomycosis.

Methods We reexamined 106 patients with distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails. (The diagnosis had previously been confirmed by a laboratory mycological examination—both potassium hydroxide [KOH] test and fungal culture—of samples obtained by the proximal sampling approach.) We collected fungal specimens from the distal nail bed first, and later from the distal underside of the nail plate. The collected specimens underwent laboratory mycological examination.

Results KOH testing was positive in 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed and only in 60 (56.6%) from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); cultures were positive in 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations showed positive KOH test results in 92 (86.8%) of the 106 patients and positive cultures in 100 (94.3%) patients.

Conclusions Based on our study, we suggest that in cases of suspected DLSO, material should be obtained by scraping nail material from the distal underside of the nail and then collecting all the material from the distal part of the nail bed.

When assessing possible onychomycosis, conventional practice is to take samples from the most proximal infected area. But this approach is usually technically difficult and may cause discomfort to patients.1-6 We therefore sought to determine the optimal location for fungal sampling from the distal part of the affected nail.

Methods

To assess the accuracy of distal sampling in diagnosing distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails, we reevaluated 106 patients with DLSO previously confirmed by microscopic visualization of fungi in potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and by fungal culture of specimens obtained using the proximal sampling approach.

Before we obtained our samples, we cleaned the nails with alcohol and pared the most distal part of the nails in an effort to eliminate contaminant molds and bacteria. Using a 1- or 2-mm curette, we took specimens first from the distal nail bed and, second, from the distal underside of the nail plate ( FIGURE ). We separated specimens for use in either direct KOH visualization or in fungal culture using Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar (Novamed; Jerusalem, Israel), which contains chloramphenicol or streptomycin and penicillin to prevent contamination.

FIGURE

Distal sampling for distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis

Using a 2-mm curette, we collected specimens from the distal nail bed first (A), and then from the distal underside of the nail plate (B). However, our recommendation for clinical practice is to reverse this order of sampling to collect all possible material.

Statistical analyses

We recorded sociodemographic characteristics and fungal culture results in basic descriptive (prevalence) tables. In univariate analysis, we used t-tests to compare the means of continuous variables (eg, age, duration of fungal infection). To assess the distribution of categorical parameters (eg, sex) and to gauge the efficacy of the different probing techniques, we used chi-square (χ2) tests. We analyzed coded data using SPSS (Chicago, IL) for Windows software, version 12.

We conducted the study according to the rules of the local Helsinki Committee.

Results

We examined 106 patients with DLSO, of which 65 (61.3%) were male and 41 (38.7%) were female, ages 23 to 72 years (mean age, 44.6). The duration of fungal infection ranged from 3 to 30 years, with a mean of 14.9 years. In 70.8% of cases, the infection involved the first toenail. Duration of the fungal disease did not differ significantly between the sexes.

KOH test results were positive for 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed, and for only 60 (56.6%) specimens from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); culture results were positive for 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations (all positive samples from the nail bed, plus positive samples from the nail underside when results from the nail bed were negative) yielded confirmation with KOH testing in 92 (86.8%) patients and with culture in 100 (94.3%) patients. There were no statistically significant differences between the combined results of both locations and the results from the distal nail bed alone (KOH, P=.143; culture, P=.149) ( TABLE ).

TABLE

Accuracy of distal sampling in 106 patients with confirmed DLSO

| Nail bed | Underside of nail plate | P value | Combined results | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive KOH | 84 (79.2%) | 60 (56.65%) | .0007 | 92 (86.8%) | .143 |

| Positive culture | 93 (87.7%) | 76 (71.7%) | .0063 | 100 (94.3%) | .149 |

| *Differences between results from sampling the nail bed alone and results from combined nail bed and nail plate sampling were not statistically significant. DLSO, distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis; KOH, potassium hydroxide. | |||||

Discussion

In DLSO, most dermatophyte species invade the middle and ventral layers of the nail plate adjacent to the nail bed, where the keratin is soft and close to the living cells below. In fact, the nail bed is probably the primary invasion site of dermatophytes, and it acts as a reservoir for continual reinfection of the growing nail.7 Obtaining confirmation of fungal infection before initiating antifungal treatment is the gold standard in clinical practice, given that antifungal agents have potentially serious adverse effects, that treatment is expensive, and that medicolegal issues exist.8

The standard methods used to detect a fungal nail infection are direct microscopy with KOH preparation and fungal culture. The KOH test is the simplest, least expensive method used in the detection of fungi, but it cannot identify the specific pathogen. Fungal speciation is done by culture. More accurate histopathologic evaluation is possible with periodic acid-Schiff stain, immunofluorescent microscopy with calcofluor stain, or polymerase chain reaction, but these techniques are more expensive and less feasible in outpatient clinics.9

The diagnostic accuracy of the KOH test and fungal culture ranges from 50% to 70%, depending on the experience of the laboratory technician and the methods used to collect and prepare the sample.8-10 It is better to take samples from the most proximal infected area by curettage or drilling, but this technique is usually more difficult than a distal approach, should be performed by skilled personnel, and may cause discomfort to patients.3,5,6

Our recommendation for practice. Earlier studies suggested that nail specimens should be taken from the nail bed.11-13 We sampled the nail bed first in our study because, in trying to determine an optimal location for sampling, we wanted to avoid contaminating nail-bed specimens with debris from the underside of the nail. In practice, however, we suggest that, in cases of suspected DLSO, clinicians first obtain specimens from the distal underside of the nail, and then collect all remaining material from the distal part of the nail bed. This technique is simple and can easily be performed in an office setting. If test results are negative but DLSO remains clinically likely, test a second sample after a week or 2.

CORRESPONDENCE Boaz Amichai, MD, Department of Dermatology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel; [email protected]

Background In onychomycosis, proper specimen collection is essential for an accurate diagnosis and initiation of appropriate therapy. Several techniques and locations have been suggested for specimen collection.

Objective To investigate the optimal technique of fungal sampling in onychomycosis.

Methods We reexamined 106 patients with distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails. (The diagnosis had previously been confirmed by a laboratory mycological examination—both potassium hydroxide [KOH] test and fungal culture—of samples obtained by the proximal sampling approach.) We collected fungal specimens from the distal nail bed first, and later from the distal underside of the nail plate. The collected specimens underwent laboratory mycological examination.

Results KOH testing was positive in 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed and only in 60 (56.6%) from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); cultures were positive in 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations showed positive KOH test results in 92 (86.8%) of the 106 patients and positive cultures in 100 (94.3%) patients.

Conclusions Based on our study, we suggest that in cases of suspected DLSO, material should be obtained by scraping nail material from the distal underside of the nail and then collecting all the material from the distal part of the nail bed.

When assessing possible onychomycosis, conventional practice is to take samples from the most proximal infected area. But this approach is usually technically difficult and may cause discomfort to patients.1-6 We therefore sought to determine the optimal location for fungal sampling from the distal part of the affected nail.

Methods

To assess the accuracy of distal sampling in diagnosing distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) of the toenails, we reevaluated 106 patients with DLSO previously confirmed by microscopic visualization of fungi in potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and by fungal culture of specimens obtained using the proximal sampling approach.

Before we obtained our samples, we cleaned the nails with alcohol and pared the most distal part of the nails in an effort to eliminate contaminant molds and bacteria. Using a 1- or 2-mm curette, we took specimens first from the distal nail bed and, second, from the distal underside of the nail plate ( FIGURE ). We separated specimens for use in either direct KOH visualization or in fungal culture using Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar (Novamed; Jerusalem, Israel), which contains chloramphenicol or streptomycin and penicillin to prevent contamination.

FIGURE

Distal sampling for distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis

Using a 2-mm curette, we collected specimens from the distal nail bed first (A), and then from the distal underside of the nail plate (B). However, our recommendation for clinical practice is to reverse this order of sampling to collect all possible material.

Statistical analyses

We recorded sociodemographic characteristics and fungal culture results in basic descriptive (prevalence) tables. In univariate analysis, we used t-tests to compare the means of continuous variables (eg, age, duration of fungal infection). To assess the distribution of categorical parameters (eg, sex) and to gauge the efficacy of the different probing techniques, we used chi-square (χ2) tests. We analyzed coded data using SPSS (Chicago, IL) for Windows software, version 12.

We conducted the study according to the rules of the local Helsinki Committee.

Results

We examined 106 patients with DLSO, of which 65 (61.3%) were male and 41 (38.7%) were female, ages 23 to 72 years (mean age, 44.6). The duration of fungal infection ranged from 3 to 30 years, with a mean of 14.9 years. In 70.8% of cases, the infection involved the first toenail. Duration of the fungal disease did not differ significantly between the sexes.

KOH test results were positive for 84 (79.2%) specimens from the distal nail bed, and for only 60 (56.6%) specimens from the distal underside of the nail plate (P=.0007); culture results were positive for 93 (87.7%) and 76 (71.7%) specimens, respectively (P=.0063). Combining results from both locations (all positive samples from the nail bed, plus positive samples from the nail underside when results from the nail bed were negative) yielded confirmation with KOH testing in 92 (86.8%) patients and with culture in 100 (94.3%) patients. There were no statistically significant differences between the combined results of both locations and the results from the distal nail bed alone (KOH, P=.143; culture, P=.149) ( TABLE ).

TABLE

Accuracy of distal sampling in 106 patients with confirmed DLSO

| Nail bed | Underside of nail plate | P value | Combined results | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive KOH | 84 (79.2%) | 60 (56.65%) | .0007 | 92 (86.8%) | .143 |

| Positive culture | 93 (87.7%) | 76 (71.7%) | .0063 | 100 (94.3%) | .149 |

| *Differences between results from sampling the nail bed alone and results from combined nail bed and nail plate sampling were not statistically significant. DLSO, distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis; KOH, potassium hydroxide. | |||||

Discussion

In DLSO, most dermatophyte species invade the middle and ventral layers of the nail plate adjacent to the nail bed, where the keratin is soft and close to the living cells below. In fact, the nail bed is probably the primary invasion site of dermatophytes, and it acts as a reservoir for continual reinfection of the growing nail.7 Obtaining confirmation of fungal infection before initiating antifungal treatment is the gold standard in clinical practice, given that antifungal agents have potentially serious adverse effects, that treatment is expensive, and that medicolegal issues exist.8

The standard methods used to detect a fungal nail infection are direct microscopy with KOH preparation and fungal culture. The KOH test is the simplest, least expensive method used in the detection of fungi, but it cannot identify the specific pathogen. Fungal speciation is done by culture. More accurate histopathologic evaluation is possible with periodic acid-Schiff stain, immunofluorescent microscopy with calcofluor stain, or polymerase chain reaction, but these techniques are more expensive and less feasible in outpatient clinics.9

The diagnostic accuracy of the KOH test and fungal culture ranges from 50% to 70%, depending on the experience of the laboratory technician and the methods used to collect and prepare the sample.8-10 It is better to take samples from the most proximal infected area by curettage or drilling, but this technique is usually more difficult than a distal approach, should be performed by skilled personnel, and may cause discomfort to patients.3,5,6

Our recommendation for practice. Earlier studies suggested that nail specimens should be taken from the nail bed.11-13 We sampled the nail bed first in our study because, in trying to determine an optimal location for sampling, we wanted to avoid contaminating nail-bed specimens with debris from the underside of the nail. In practice, however, we suggest that, in cases of suspected DLSO, clinicians first obtain specimens from the distal underside of the nail, and then collect all remaining material from the distal part of the nail bed. This technique is simple and can easily be performed in an office setting. If test results are negative but DLSO remains clinically likely, test a second sample after a week or 2.

CORRESPONDENCE Boaz Amichai, MD, Department of Dermatology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel; [email protected]

1. Lawry MA, Haneke E, Strobeck K, et al. Methods for diagnosing onychomycosis: a comparative study and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1112-1116.

2. Elewski BE. Diagnostic techniques for confirming onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3 pt 2):S6-S9.

3. Heikkila H. Isolation of fungi from onychomycosis-suspected nails by two methods: clipping and drilling. Mycoses. 1996;39:479-482.

4. Mochizuki T, Kawasaki M, Tanabe H, et al. A nail drilling method suitable for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Dermatol. 2005;32:108-113.

5. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Nail sampling in onychomycosis: comparative study of curettage from three sites of the infected nail. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1108-1111.

6. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

7. Hay RJ, Baran R, Haneke E. Fungal (onychomycosis) and other infections involving the nail apparatus. In: Baran R, Dawber RPR, eds. Disease of the Nails and Their Management. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Sciences Ltd; 1994: 97–134.

8. Daniel CR, 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

9. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

10. Arnold B, Kianifrad F, Tavakkol A. A comparison of KOH and culture results from two mycology laboratories for the diagnosis of onychomycosis during a randomized, multicenter clinical trial: a subset study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:421-423.

11. English MP. Nails and fungi. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:697-701.

12. Elewski BE. Clinical pearl: diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:500-501.

13. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677–678.

1. Lawry MA, Haneke E, Strobeck K, et al. Methods for diagnosing onychomycosis: a comparative study and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1112-1116.

2. Elewski BE. Diagnostic techniques for confirming onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3 pt 2):S6-S9.

3. Heikkila H. Isolation of fungi from onychomycosis-suspected nails by two methods: clipping and drilling. Mycoses. 1996;39:479-482.

4. Mochizuki T, Kawasaki M, Tanabe H, et al. A nail drilling method suitable for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Dermatol. 2005;32:108-113.

5. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Nail sampling in onychomycosis: comparative study of curettage from three sites of the infected nail. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1108-1111.

6. Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B, et al. Collection of fungi samples from nails: comparative study of curettage and drilling techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:182-185.

7. Hay RJ, Baran R, Haneke E. Fungal (onychomycosis) and other infections involving the nail apparatus. In: Baran R, Dawber RPR, eds. Disease of the Nails and Their Management. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Sciences Ltd; 1994: 97–134.

8. Daniel CR, 3rd, Elewski BE. The diagnosis of nail fungus infection revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1162-1164.

9. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:193-197.

10. Arnold B, Kianifrad F, Tavakkol A. A comparison of KOH and culture results from two mycology laboratories for the diagnosis of onychomycosis during a randomized, multicenter clinical trial: a subset study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:421-423.

11. English MP. Nails and fungi. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:697-701.

12. Elewski BE. Clinical pearl: diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:500-501.

13. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677–678.

Aspirin for primary prevention of CVD: Are the right people using it?

Purpose Aspirin is recommended for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults at high risk, but little is known about sociodemographic disparities in prophylactic aspirin use. This study examined the association between sociodemographic characteristics and regular aspirin use among adults in Wisconsin who are free of CVD.

Methods A cross-sectional design was used, and data collected from 2008 to 2010. Regular aspirin use (aspirin therapy) was defined as taking aspirin most days of the week. We found 831 individuals for whom complete data were available for regression analyses and stratified the sample into 2 groups: those for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and those for whom it was not indicated, based on national guidelines.

Results Of the 268 patients for whom aspirin therapy was indicated, only 83 (31%) were using it regularly, and 102 (18%) of the 563 participants who did not have an aspirin indication were taking it regularly. In the group with an aspirin indication, participants who were older had higher rates of regular aspirin use than younger patients (odds ratio [OR]=1.07; P<.001), and women had significantly higher adjusted odds of regular aspirin use than men (OR=3.49; P=.021). Among those for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, the adjusted odds of regular aspirin use were significantly higher among older participants (OR=1.07; P<.001) vs their younger counterparts, and significantly lower among Hispanic or nonwhite participants (OR=0.32; P=.063) relative to non-Hispanic whites.

Conclusions Aspirin therapy is underused by those at high risk for CVD—individuals who could gain cardioprotection from regular use—and overused by those at low risk for CVD, for whom the risk of major bleeding outweighs the potential benefit. Stronger primary care initiatives may be needed to ensure that patients undergo regular screening for aspirin use, particularly middle-aged men at high CVD risk. Patient education may be needed, as well, to better inform people (particularly older, non-Hispanic whites) about the risks of regular aspirin use that is not medically indicated.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the principal cause of death in the United States.1 As the population grows older and obesity and diabetes become increasingly prevalent, the prevalence of CVD is also expected to rise.2,3 Fortunately, many CVD events can be prevented or delayed by modifying risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and smoking. Interventions associated with a reduction in risk have led to a reduction in CVD events4,5 and contributed to a steady decline in cardiac deaths.6

Control of platelet aggregation is a cornerstone of primary CVD prevention.7 In an outpatient setting, this usually translates into identifying patients who are at high risk for a CVD event and advising them to take low-dose aspirin daily or every other day. Although not without controversy,8,9 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends regular aspirin use for primary CVD prevention for middle-aged to older men at high risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and women at high risk for ischemic stroke.10

The efficacy of this intervention is proven: In primary prevention trials, regular aspirin use is associated with a 14% reduction in the likelihood of CVD events over 7 years.11 What’s more, aspirin therapy, as recommended by the USPSTF, is among the most cost-effective clinic-based preventive measures.12

In 2004, 41% of US adults age 40 or older reported taking aspirin regularly13 —an increase of approximately 20% since 1999.14 More recent data from a national population-based cohort study found that 41% of adults ages 45 to 90 years who did not have CVD but were at moderate to high risk for a CVD event reported taking aspirin ≥3 days per week.15 In the same study, almost one-fourth of those at low CVD risk also reported regular aspirin use.

While regular aspirin use for primary CVD prevention has been on the rise,13,14 the extent to which this intervention has penetrated various segments of the population is unclear. Several studies have found that aspirin use is consistently highest among those who are older, male, and white.15-17 Other socioeconomic variables (eg, education level, employment, marital status) have received little attention. And no previous study has used national guidelines for aspirin therapy to stratify samples.

A look at overuse and underuse. To ensure that aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention is directed at those who are most likely to benefit from it, a better understanding of variables associated with both aspirin overuse and underuse is needed. This area of research is important, in part because direct-to-consumer aspirin marketing may be particularly influential among groups at low risk for CVD—for whom the risk of excess bleeding outweighs the potential for disease prevention.13,18

This study was undertaken to examine the association between specific sociodemographic variables and aspirin use among a representative sample of Wisconsin adults without CVD, looking both at those for whom aspirin therapy is indicated and those for whom it is not indicated based on national guidelines.

Methods

Design

We used a cross-sectional design, with data from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW),19 an annual survey of Wisconsin residents ages 21 to 74 years. SHOW uses a 2-stage stratified cluster sampling design to select households, with all age-eligible household members invited to participate. Recruitment for the annual survey consists of general community-wide announcements, as well as an initial letter and up to 6 visits to the randomly selected households to encourage participation.

By the end of 2010, SHOW had 1572 enrollees—about 53% of all eligible invitees. The demographic profile of SHOW enrollees was similar to US census data for all Wisconsin adults during the same time frame.19 All SHOW procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent.

Study sample

Our analyses were based on data provided by SHOW participants who were screened and enrolled between 2008 and 2010. To be included in our study, participants had to be between the ages of 35 and 74 years; not pregnant, on active military duty, or institutionalized; and have no personal history of CVD (myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, or transient ischemic attack) or CVD risk equivalent (type 1 or type 2 diabetes) at the time of recruitment. Data on key study variables had to be available, as well. (We used 35 years as the lower age limit because of the very low likelihood of CVD in younger individuals.)

We stratified the analytical sample (N=831) into 2 groups—participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and those for whom it was not indicated—in order to examine aspirin’s appropriate (recommended) and inappropriate use.

Measures

Outcome. The outcome variable was aspirin use. SHOW had asked participants how often they took aspirin. Similar to the methods used by Sanchez et al,15 we classified those who reported taking aspirin most (≥4) days of the week as regular aspirin users. All others were classified as nonregular aspirin users. Participants were not asked about the daily dose or weekly volume of aspirin.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables considered in our analysis were age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, marital/partner status, employment status, health insurance, and region of residence within Wisconsin.

All participants underwent physical examinations, conducted as part of SHOW, at either a permanent or mobile exam center. Blood pressure was measured after a 5-minute rest period in a seated position, and the average of the last 2 out of 3 consecutive measurements was reported. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and blood samples were obtained by venipuncture, processed immediately, and sent to the Marshfield Clinic laboratory for measuring total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

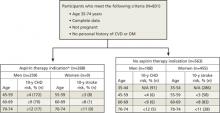

Indications for aspirin therapy. We stratified the sample by those who were and those who were not candidates for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention based on the latest guidelines from the USPSTF ( FIGURE ).10 The Task Force recommends aspirin therapy for men ages 45 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of a coronary heart disease (CHD) event and women ages 55 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of stroke. We used the global CVD risk equation derived from the Framingham Heart Study (based on age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, and total and HDL cholesterol) to calculate each participant’s 10-year risk and, thus, determine whether aspirin therapy was or was not indicated.20 Total and HDL cholesterol values were missing for 94 participants in the analytical sample; their 10-year CVD risk was estimated using BMI, a reasonable alternative to more conventional CVD risk prediction when laboratory values are unavailable.21

FIGURE

Study (SHOW) sample, stratified based on aspirin indication10

*US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines were slightly modified for this analysis: The upper age bound was reduced from 79 to 74 years because the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin did not enroll participants >74 years.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; N/A, not applicable; SHOW, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin.

Statistical analyses

All analytical procedures were conducted using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS Version 9.2; Cary, NC). A complete-case framework was used.

We used multivariate logistic regression for survey data (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to examine the association between aspirin use and sociodemographic variables. Two separate analyses were conducted, one of participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and the other for participants for whom it was not. The outcomes were modeled dichotomously, as regular vs nonregular aspirin users, and a collinearity check was done. 21

Initially, we created univariate models to gauge the crude relationship between each variable and aspirin use. Any variable with P<.20 in its univariate association with regular aspirin use was considered for inclusion in the final multivariate regression model. In the multivariate analyses, we sequentially eliminated variables with the weakest association with aspirin use until only significant (P<.10) independent predictors remained. Appropriate weighting was applied based on survey strata and cluster structure.19

Results

Of the 831 participants who met the eligibility criteria for our analysis, 268 (32%) had an aspirin indication. TABLE 1 shows the key characteristics of the analytical sample, stratified by those for whom aspirin was indicated and those for whom it was not. The sample was primarily middle-aged (mean age 52.4±0.36) and non-Hispanic white (93%). Compared with those for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, the group with an aspirin indication was significantly older (56.9 vs 50.3) and had a significantly higher proportion of males (97% vs 19%). As expected, those for whom aspirin was indicated were also at higher risk for CHD and stroke, most notably as a result of significantly higher systolic BP (131.9 vs 121.5 mm Hg) and lower HDL cholesterol (42.5 vs 52.6 mg/dL) compared with participants without an aspirin indication.

TABLE 1

Study sample, by sociodemographic variable and aspirin indication

| Variable | Full sample (N=831) | Aspirin indicated (n=268) | Aspirin not indicated (n=563) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 52.4 | 56.9 | 50.3 |

| Sex, n Male Female | 367 464 | 259 9 | 108 455 |

| Race/ethnicity, n White, non-Hispanic Nonwhite/Hispanic | 776 55 | 252 16 | 524 39 |

| Marital status, n Married/partnered Not married or partnered | 637 194 | 215 53 | 422 141 |

| Health insurance, n Uninsured Insured | 76 755 | 26 242 | 50 513 |

| Education, n ≤High school Associate’s degree ≥Bachelor’s degree | 217 312 302 | 77 107 84 | 140 205 218 |

| Employment, n Unemployed Student/retiree/home Employed | 98 147 586 | 33 52 183 | 65 95 403 |

When aspirin was indicated, use was linked to age and sex

In the group with an aspirin indication (n=268), 83 (31%) reported taking aspirin most days of the week. The initial examination of sociodemographic variables showed that age, sex, and employment status demonstrated significant univariate associations with regular aspirin use ( TABLE 2 ). In the multivariate model, however, the odds of regular aspirin use were significantly greater among participants who were older (odds ratio [OR], 1.07; P<.001) or female (OR, 3.49; P=.021) compared with participants who were younger or male, respectively.

TABLE 2

Participants who have an aspirin indication: Association between sociodemographic variables and regular aspirin use

| Variable | Regular aspirin use, OR (95% CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older vs younger | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) | .001 |

| Sex Female vs male | 3.89 (1.42-10.67)† | .008 |

| Race/ethnicity Nonwhite/Hispanic vs white non-Hispanic | 0.55 (0.09-3.47) | .526 |

| Marital status Not married/partnered vs married/partner | 0.83 (0.36-1.95) | .678 |

| Health insurance Uninsured vs insured | 0.86 (0.50-1.47) | .579 |

| Education ≥Bachelor’s degree vs ≤high school Associate’s degree/some college vs ≤high school | 1.58 (0.75-3.34) 1.36 (0.74-2.49) | .234 .325 |

| Employment Student or retired vs employed Unemployed vs employed | 2.96 (1.74-5.03) 0.62 (0.25-1.56) | .001 .314 |

| *Significance was defined as P<.10. †Multivariate adjusted model: 3.49 (95% CI, 1.21-10.07; P=.021). CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. | ||

When aspirin was not indicated, age and sex still affected use

Among the 563 participants for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, 102 (18%) reported taking aspirin regularly. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, health insurance, and employment ( TABLE 3 ), as well as region of residence and study enrollment year, had significant univariate associations with regular aspirin use; these variables were tested for potential inclusion in the multivariate model. In the final multivariate regression model, the odds of regular aspirin use were significantly greater among participants who were older (OR, 1.07; P<.001) and significantly lower among participants who were Hispanic or nonwhite (OR, 0.32; P=.063).

TABLE 3

Participants who do not have an aspirin indication: Association between sociodemographic variables and regular aspirin use

| Variable | Regular aspirin use, OR (95% CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older vs younger | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | .001 |

| Sex Female vs male | 1.60 (0.84-3.04) | .152 |

| Race/ethnicity Nonwhite or Hispanic vs white non-Hispanic | 0.23 (0.07- 0.73)† | .013 |

| Marital status Not married/partnered vs married/partnered | 1.00 (0.63-1.59) | .992 |

| Health insurance Uninsured vs insured | 0.36 (0.11- 1.15) | .086 |

| Education Bachelor’s or higher vs high school or less Associate’s/some college vs high school or less | 0.74 (0.35-1.57) 0.67 (0.38-1.17) | .431 .158 |

| Employment Student/retired vs employed Unemployed vs employed | 2.35 (1.32-4.20) 0.78 (0.26- 2.34) | .004 .652 |

| *Significance was defined as P<.10. †Multivariate adjusted model: 0.32 (95% CI, 0.10-1.06; P=.063). CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. | ||

Discussion

Aspirin was generally underutilized in the group with significant CVD risk (n=268) in our study, with slightly less than a third of participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated taking it most days of the week. Despite trends of increased aspirin use among US adults in recent years,15 aspirin therapy in the 2008-2010 SHOW sample was lower than in 2005 to 2008. It was also lower than national estimates of aspirin use for primary CVD prevention15,22 —but about 20% higher than estimates of overall aspirin use in Wisconsin 20 years ago.23 Consistent with previous research, the final adjusted model and sensitivity analysis indicated that older individuals were more likely to take aspirin regularly.

Contrary to the findings in some previous studies,15-17 however, our analysis suggested that women had a higher adjusted odds of regular aspirin use compared with men. This result should be interpreted with extreme caution, however, because so few females (9 of 464 [3%]) met the current USPSTF criteria for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention. The previous USPSTF guidelines24,25 were less conservative, with a lower minimum age and threshold for CVD risk for women. The revision is the likely result of recent primary prevention trials10 that found regular aspirin use provided less cardioprotection for younger women.

The sample without an aspirin indication—roughly twice the size of the group with an aspirin indication (563 vs 268), which is reflective of the general population of Wisconsin—was useful in highlighting inappropriate use. There were clear indications of aspirin overuse in this group, with 18% of the sample reporting that they took aspirin regularly. The finding that inappropriate aspirin use was more likely in non-Hispanic whites vs minorities is similar to the result of an earlier study in which blacks, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans with low CVD risk were much less likely to report regular aspirin use compared with whites at low risk.15

The main concern with regular aspirin use in those for whom it is not indicated for primary CVD prevention is the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and, less commonly, hemorrhagic stroke.26 To illustrate this point, consider the following: About 10% of SHOW participants ages 35 to 74 years had no history of CVD and no indication for aspirin therapy based on the latest USPSTF guidelines, but took aspirin regularly nonetheless. Extrapolating those numbers to the entire state of Wisconsin would suggest that approximately 270,000 state residents have a similar profile. Assuming an extra 1.3 major bleeding events per 1000 person-years of regular aspirin use (as a meta-analysis of studies of adverse events associated with antiplatelet therapy found),27 that would translate into an estimated 350 major bleeding events per year in Wisconsin that are attributable to aspirin overuse.

In view of the current USPSTF recommendations,10 aspirin is not optimally utilized by Wisconsin residents for the primary prevention of CVD. Aspirin therapy is not used enough by those with a high CVD risk, who could derive substantial vascular disease protection from it. Conversely, aspirin therapy is overused by those with a low CVD risk, for whom the risk of major bleeding is significantly higher than the potential for vascular disease protection. Furthermore, younger individuals at high CVD risk appear to be least likely to take aspirin regularly.

Recommendations

The strongest modifiable predictor of regular aspirin use is a recommendation from a clinician.13 Therefore, we recommend stronger primary care initiatives to ensure that patients are screened for aspirin use more frequently, particularly middle-aged men at high CVD risk. This clinic-based initiative could reach a larger proportion of the general population when combined with broader, community-oriented CVD preventive services.28

More precise marketing and education are also needed. Because aspirin is a low-cost over-the-counter product that leads the consumer market for analgesics,29 the general public (and older, non-Hispanic whites, in particular) needs to be better informed about the risks of medically inappropriate aspirin use for primary CVD prevention.

Study limitations

Selection and measurement biases were among the chief study limitations.

Study (SHOW) enrollment rate was slightly above 50%, with steady increases in enrollment each year (from 46% in 2008-2009 to 56% in 2010) due to expanded recruitment and consolidation of field operations.

Aspirin use was self-reported, and SHOW did not capture the reason for taking it (eg, CVD prevention or pain management). Some evidence of overreporting of aspirin use among older individuals exists,30 suggesting that a more objective measure of aspirin use (eg, pill bottle verification or blood platelet aggregation test) could yield different results.

Certain confounders were not measured, most notably contraindications to aspirin (eg, genetic platelet abnormalities). Such findings could explain some patterns of aspirin use in both strata, as up to 10% of any given population has a contraindication to aspirin due to allergy, intolerance, gastrointestinal ulcer, concomitant anticoagulant medication, or other high bleeding risk.18,31 Few of these variables were known about our sample.

TABLE 4W (available below) provides a breakdown of some possible aspirin contraindications, as well as possible reasons other than primary CVD prevention for regular aspirin use. Because clinical judgment is often required to assess the degree of severity of a given health condition in order to deem it an aspirin contraindication, these findings could not reliably be used to reclassify participants. We present them simply for hypothesis generation.

Some data collection predates the current USPSTF guidelines,10 which could have resulted in a misclassification of participants’ aspirin indication. However, sensitivity analyses restricted to the 2010 sample alone—the only one with data collection after the newer guidelines were released—did not reveal any meaningful differences.

Other methodological limitations include the less racially diverse population of Wisconsin compared with other parts of the country and the sample size, which did not permit testing for statistical interactions and perhaps resulted in larger confidence intervals for some associations (eg, race/ethnicity) relative to the population as a whole.

TABLE 4W

Possible reasons for aspirin use—or contraindication— by aspirin indication*

| Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had … | Aspirin indicated (n=268) | Aspirin not indicated (n=563) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular aspirin user (n=83) | Nonregular aspirin user (n=185) | Regular aspirin user (n=102) | Nonregular aspirin user (n=461) | |

| Migraine headache Yes No | 20 (24%) 63 (76%) | 28 (15%) 157 (85%) | 24 (24%) 78 (76%) | 76 (16%) 385 (84%) |

| Arthritis† Yes No | 2 (2%) 81 (98%) | 1 (1%) 184 (99%) | 12 (12%) 90 (88%) | 26 (6%) 435 (94%) |

| Stomach or intestinal ulcer Yes No | 5 (6%) 78 (94%) | 6 (3%) 179 (97%) | 7 (7%) 95 (93%) | 10 (2%) 451 (98%) |

| Reflux or GERD Yes No | 8 (10%) 75 (90%) | 14 (8%) 171 (92%) | 11 (11%) 91 (89%) | 32 (7%) 429 (93%) |

| Values presented as n (%). *Data not included in study analysis. †Osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. GERD, gastric esophageal reflux disease. | ||||

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Matt Walsh, PhD, for his assistance in creating the analytical dataset, as well as Sally Steward-Townsend, Susan Wright, Bri Deyo, Bethany Varley, and the rest of the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin staff.

CORRESPONDENCE Jeffrey J. VanWormer, PhD, Epidemiology Research Center, Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation, 1000 North Oak Avenue, Marshfield, WI 54449; [email protected]

1. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18-e209.

2. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933-944.

3. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Wyatt HR. The medical cost of cardiometabolic risk factor clusters in the United States. Obesity. 2007;15:3150-3158.

4. Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. AHA guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke: 2002 update. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 2002;106:388-391.

5. Kriekard P, Gharacholou SM, Peterson ED. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in older adults: a status report. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:745-755.

6. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388-2398.

7. Hennekens CH, Schneider WR. The need for wider and appropriate utilization of aspirin and statins in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:95-107.

8. Barnett H, Burrill P, Iheanacho I. Don’t use aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2010;340:c1805.-

9. Sanchez-Ross M, Waller AH, Maher J, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity. Minerva Med. 2010;101:205-214.

10. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:396-404.

11. Bartolucci AA, Tendera M, Howard G. Meta-analysis of multiple primary prevention trials of cardiovascular events using aspirin. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1796-1801.

12. Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, et al. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:52-61.

13. Pignone M, Anderson GK, Binns K, et al. Aspirin use among adults aged 40 and older in the United States results of a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:403-407.

14. Ajani UA, Ford ES, Greenland KJ, et al. Aspirin use among US adults: behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:74-77.

15. Sanchez DR, Diez Roux AV, Michos ED, et al. Comparison of the racial/ethnic prevalence of regular aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:41-46.

16. Stafford RS, Monti V, Ma J. Underutilization of aspirin persists in US ambulatory care for the secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e353.-

17. Rodondi N, Vittinghoff E, Cornuz J, et al. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in older adults. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl):1288e1-1288e9.

18. Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease: a population-based study in Switzerland. Prev Med. 2008;46:137-144.

19. Nieto FJ, Peppard PE, Engelman CD, et al. The Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW), a novel infrastructure for population health research: rationale and methods. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:785.-

20. D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743-753.

21. Cody RP, Smith JK. Applied Statistics and the SAS Programming Language. New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 2005.

22. Mallonee S, Daniels CG, Mold JW, et al. Increasing aspirin use among persons at risk for cardiovascular events in Oklahoma. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2010;103:254-260.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of aspirin use to prevent heart disease—Wisconsin, 1991, and Michigan, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:498-502.

24. US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:157-160.

25. Werner M, Kelsberg G, Weismantel AM. Which healthy adults should take aspirin? J Fam Pract. 2004;53:146-150.

26. Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:306-313.

27. McQuaid KR, Laine L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse events of low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2006;119:624-638.

28. VanWormer JJ, Johnson PJ, Pereira RF, et al. The Heart of New Ulm project: using community-based cardiometabolic risk factor screenings in a rural population health improvement initiative. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15:135-143.

29. Jeffreys D. Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2005.

30. Smith NL, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, et al. The reliability of medication inventory methods compared to serum levels of cardiovascular drugs in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:143-146.

31. Hedman J, Kaprio J, Poussa T, et al. Prevalence of asthma, aspirin intolerance, nasal polyposis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:717-722.

Purpose Aspirin is recommended for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults at high risk, but little is known about sociodemographic disparities in prophylactic aspirin use. This study examined the association between sociodemographic characteristics and regular aspirin use among adults in Wisconsin who are free of CVD.

Methods A cross-sectional design was used, and data collected from 2008 to 2010. Regular aspirin use (aspirin therapy) was defined as taking aspirin most days of the week. We found 831 individuals for whom complete data were available for regression analyses and stratified the sample into 2 groups: those for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and those for whom it was not indicated, based on national guidelines.

Results Of the 268 patients for whom aspirin therapy was indicated, only 83 (31%) were using it regularly, and 102 (18%) of the 563 participants who did not have an aspirin indication were taking it regularly. In the group with an aspirin indication, participants who were older had higher rates of regular aspirin use than younger patients (odds ratio [OR]=1.07; P<.001), and women had significantly higher adjusted odds of regular aspirin use than men (OR=3.49; P=.021). Among those for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, the adjusted odds of regular aspirin use were significantly higher among older participants (OR=1.07; P<.001) vs their younger counterparts, and significantly lower among Hispanic or nonwhite participants (OR=0.32; P=.063) relative to non-Hispanic whites.

Conclusions Aspirin therapy is underused by those at high risk for CVD—individuals who could gain cardioprotection from regular use—and overused by those at low risk for CVD, for whom the risk of major bleeding outweighs the potential benefit. Stronger primary care initiatives may be needed to ensure that patients undergo regular screening for aspirin use, particularly middle-aged men at high CVD risk. Patient education may be needed, as well, to better inform people (particularly older, non-Hispanic whites) about the risks of regular aspirin use that is not medically indicated.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the principal cause of death in the United States.1 As the population grows older and obesity and diabetes become increasingly prevalent, the prevalence of CVD is also expected to rise.2,3 Fortunately, many CVD events can be prevented or delayed by modifying risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and smoking. Interventions associated with a reduction in risk have led to a reduction in CVD events4,5 and contributed to a steady decline in cardiac deaths.6

Control of platelet aggregation is a cornerstone of primary CVD prevention.7 In an outpatient setting, this usually translates into identifying patients who are at high risk for a CVD event and advising them to take low-dose aspirin daily or every other day. Although not without controversy,8,9 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends regular aspirin use for primary CVD prevention for middle-aged to older men at high risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and women at high risk for ischemic stroke.10

The efficacy of this intervention is proven: In primary prevention trials, regular aspirin use is associated with a 14% reduction in the likelihood of CVD events over 7 years.11 What’s more, aspirin therapy, as recommended by the USPSTF, is among the most cost-effective clinic-based preventive measures.12

In 2004, 41% of US adults age 40 or older reported taking aspirin regularly13 —an increase of approximately 20% since 1999.14 More recent data from a national population-based cohort study found that 41% of adults ages 45 to 90 years who did not have CVD but were at moderate to high risk for a CVD event reported taking aspirin ≥3 days per week.15 In the same study, almost one-fourth of those at low CVD risk also reported regular aspirin use.

While regular aspirin use for primary CVD prevention has been on the rise,13,14 the extent to which this intervention has penetrated various segments of the population is unclear. Several studies have found that aspirin use is consistently highest among those who are older, male, and white.15-17 Other socioeconomic variables (eg, education level, employment, marital status) have received little attention. And no previous study has used national guidelines for aspirin therapy to stratify samples.

A look at overuse and underuse. To ensure that aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention is directed at those who are most likely to benefit from it, a better understanding of variables associated with both aspirin overuse and underuse is needed. This area of research is important, in part because direct-to-consumer aspirin marketing may be particularly influential among groups at low risk for CVD—for whom the risk of excess bleeding outweighs the potential for disease prevention.13,18

This study was undertaken to examine the association between specific sociodemographic variables and aspirin use among a representative sample of Wisconsin adults without CVD, looking both at those for whom aspirin therapy is indicated and those for whom it is not indicated based on national guidelines.

Methods

Design

We used a cross-sectional design, with data from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW),19 an annual survey of Wisconsin residents ages 21 to 74 years. SHOW uses a 2-stage stratified cluster sampling design to select households, with all age-eligible household members invited to participate. Recruitment for the annual survey consists of general community-wide announcements, as well as an initial letter and up to 6 visits to the randomly selected households to encourage participation.

By the end of 2010, SHOW had 1572 enrollees—about 53% of all eligible invitees. The demographic profile of SHOW enrollees was similar to US census data for all Wisconsin adults during the same time frame.19 All SHOW procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent.

Study sample

Our analyses were based on data provided by SHOW participants who were screened and enrolled between 2008 and 2010. To be included in our study, participants had to be between the ages of 35 and 74 years; not pregnant, on active military duty, or institutionalized; and have no personal history of CVD (myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, or transient ischemic attack) or CVD risk equivalent (type 1 or type 2 diabetes) at the time of recruitment. Data on key study variables had to be available, as well. (We used 35 years as the lower age limit because of the very low likelihood of CVD in younger individuals.)

We stratified the analytical sample (N=831) into 2 groups—participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and those for whom it was not indicated—in order to examine aspirin’s appropriate (recommended) and inappropriate use.

Measures

Outcome. The outcome variable was aspirin use. SHOW had asked participants how often they took aspirin. Similar to the methods used by Sanchez et al,15 we classified those who reported taking aspirin most (≥4) days of the week as regular aspirin users. All others were classified as nonregular aspirin users. Participants were not asked about the daily dose or weekly volume of aspirin.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables considered in our analysis were age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, marital/partner status, employment status, health insurance, and region of residence within Wisconsin.

All participants underwent physical examinations, conducted as part of SHOW, at either a permanent or mobile exam center. Blood pressure was measured after a 5-minute rest period in a seated position, and the average of the last 2 out of 3 consecutive measurements was reported. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and blood samples were obtained by venipuncture, processed immediately, and sent to the Marshfield Clinic laboratory for measuring total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Indications for aspirin therapy. We stratified the sample by those who were and those who were not candidates for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention based on the latest guidelines from the USPSTF ( FIGURE ).10 The Task Force recommends aspirin therapy for men ages 45 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of a coronary heart disease (CHD) event and women ages 55 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of stroke. We used the global CVD risk equation derived from the Framingham Heart Study (based on age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, and total and HDL cholesterol) to calculate each participant’s 10-year risk and, thus, determine whether aspirin therapy was or was not indicated.20 Total and HDL cholesterol values were missing for 94 participants in the analytical sample; their 10-year CVD risk was estimated using BMI, a reasonable alternative to more conventional CVD risk prediction when laboratory values are unavailable.21

FIGURE

Study (SHOW) sample, stratified based on aspirin indication10

*US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines were slightly modified for this analysis: The upper age bound was reduced from 79 to 74 years because the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin did not enroll participants >74 years.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; N/A, not applicable; SHOW, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin.

Statistical analyses

All analytical procedures were conducted using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS Version 9.2; Cary, NC). A complete-case framework was used.

We used multivariate logistic regression for survey data (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to examine the association between aspirin use and sociodemographic variables. Two separate analyses were conducted, one of participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and the other for participants for whom it was not. The outcomes were modeled dichotomously, as regular vs nonregular aspirin users, and a collinearity check was done. 21

Initially, we created univariate models to gauge the crude relationship between each variable and aspirin use. Any variable with P<.20 in its univariate association with regular aspirin use was considered for inclusion in the final multivariate regression model. In the multivariate analyses, we sequentially eliminated variables with the weakest association with aspirin use until only significant (P<.10) independent predictors remained. Appropriate weighting was applied based on survey strata and cluster structure.19

Results

Of the 831 participants who met the eligibility criteria for our analysis, 268 (32%) had an aspirin indication. TABLE 1 shows the key characteristics of the analytical sample, stratified by those for whom aspirin was indicated and those for whom it was not. The sample was primarily middle-aged (mean age 52.4±0.36) and non-Hispanic white (93%). Compared with those for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, the group with an aspirin indication was significantly older (56.9 vs 50.3) and had a significantly higher proportion of males (97% vs 19%). As expected, those for whom aspirin was indicated were also at higher risk for CHD and stroke, most notably as a result of significantly higher systolic BP (131.9 vs 121.5 mm Hg) and lower HDL cholesterol (42.5 vs 52.6 mg/dL) compared with participants without an aspirin indication.

TABLE 1

Study sample, by sociodemographic variable and aspirin indication

| Variable | Full sample (N=831) | Aspirin indicated (n=268) | Aspirin not indicated (n=563) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 52.4 | 56.9 | 50.3 |

| Sex, n Male Female | 367 464 | 259 9 | 108 455 |

| Race/ethnicity, n White, non-Hispanic Nonwhite/Hispanic | 776 55 | 252 16 | 524 39 |

| Marital status, n Married/partnered Not married or partnered | 637 194 | 215 53 | 422 141 |

| Health insurance, n Uninsured Insured | 76 755 | 26 242 | 50 513 |

| Education, n ≤High school Associate’s degree ≥Bachelor’s degree | 217 312 302 | 77 107 84 | 140 205 218 |

| Employment, n Unemployed Student/retiree/home Employed | 98 147 586 | 33 52 183 | 65 95 403 |

When aspirin was indicated, use was linked to age and sex

In the group with an aspirin indication (n=268), 83 (31%) reported taking aspirin most days of the week. The initial examination of sociodemographic variables showed that age, sex, and employment status demonstrated significant univariate associations with regular aspirin use ( TABLE 2 ). In the multivariate model, however, the odds of regular aspirin use were significantly greater among participants who were older (odds ratio [OR], 1.07; P<.001) or female (OR, 3.49; P=.021) compared with participants who were younger or male, respectively.

TABLE 2

Participants who have an aspirin indication: Association between sociodemographic variables and regular aspirin use

| Variable | Regular aspirin use, OR (95% CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older vs younger | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) | .001 |

| Sex Female vs male | 3.89 (1.42-10.67)† | .008 |

| Race/ethnicity Nonwhite/Hispanic vs white non-Hispanic | 0.55 (0.09-3.47) | .526 |

| Marital status Not married/partnered vs married/partner | 0.83 (0.36-1.95) | .678 |

| Health insurance Uninsured vs insured | 0.86 (0.50-1.47) | .579 |

| Education ≥Bachelor’s degree vs ≤high school Associate’s degree/some college vs ≤high school | 1.58 (0.75-3.34) 1.36 (0.74-2.49) | .234 .325 |

| Employment Student or retired vs employed Unemployed vs employed | 2.96 (1.74-5.03) 0.62 (0.25-1.56) | .001 .314 |

| *Significance was defined as P<.10. †Multivariate adjusted model: 3.49 (95% CI, 1.21-10.07; P=.021). CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. | ||

When aspirin was not indicated, age and sex still affected use

Among the 563 participants for whom aspirin therapy was not indicated, 102 (18%) reported taking aspirin regularly. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, health insurance, and employment ( TABLE 3 ), as well as region of residence and study enrollment year, had significant univariate associations with regular aspirin use; these variables were tested for potential inclusion in the multivariate model. In the final multivariate regression model, the odds of regular aspirin use were significantly greater among participants who were older (OR, 1.07; P<.001) and significantly lower among participants who were Hispanic or nonwhite (OR, 0.32; P=.063).

TABLE 3

Participants who do not have an aspirin indication: Association between sociodemographic variables and regular aspirin use

| Variable | Regular aspirin use, OR (95% CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older vs younger | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | .001 |

| Sex Female vs male | 1.60 (0.84-3.04) | .152 |

| Race/ethnicity Nonwhite or Hispanic vs white non-Hispanic | 0.23 (0.07- 0.73)† | .013 |

| Marital status Not married/partnered vs married/partnered | 1.00 (0.63-1.59) | .992 |

| Health insurance Uninsured vs insured | 0.36 (0.11- 1.15) | .086 |

| Education Bachelor’s or higher vs high school or less Associate’s/some college vs high school or less | 0.74 (0.35-1.57) 0.67 (0.38-1.17) | .431 .158 |

| Employment Student/retired vs employed Unemployed vs employed | 2.35 (1.32-4.20) 0.78 (0.26- 2.34) | .004 .652 |

| *Significance was defined as P<.10. †Multivariate adjusted model: 0.32 (95% CI, 0.10-1.06; P=.063). CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. | ||

Discussion

Aspirin was generally underutilized in the group with significant CVD risk (n=268) in our study, with slightly less than a third of participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated taking it most days of the week. Despite trends of increased aspirin use among US adults in recent years,15 aspirin therapy in the 2008-2010 SHOW sample was lower than in 2005 to 2008. It was also lower than national estimates of aspirin use for primary CVD prevention15,22 —but about 20% higher than estimates of overall aspirin use in Wisconsin 20 years ago.23 Consistent with previous research, the final adjusted model and sensitivity analysis indicated that older individuals were more likely to take aspirin regularly.

Contrary to the findings in some previous studies,15-17 however, our analysis suggested that women had a higher adjusted odds of regular aspirin use compared with men. This result should be interpreted with extreme caution, however, because so few females (9 of 464 [3%]) met the current USPSTF criteria for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention. The previous USPSTF guidelines24,25 were less conservative, with a lower minimum age and threshold for CVD risk for women. The revision is the likely result of recent primary prevention trials10 that found regular aspirin use provided less cardioprotection for younger women.

The sample without an aspirin indication—roughly twice the size of the group with an aspirin indication (563 vs 268), which is reflective of the general population of Wisconsin—was useful in highlighting inappropriate use. There were clear indications of aspirin overuse in this group, with 18% of the sample reporting that they took aspirin regularly. The finding that inappropriate aspirin use was more likely in non-Hispanic whites vs minorities is similar to the result of an earlier study in which blacks, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans with low CVD risk were much less likely to report regular aspirin use compared with whites at low risk.15

The main concern with regular aspirin use in those for whom it is not indicated for primary CVD prevention is the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and, less commonly, hemorrhagic stroke.26 To illustrate this point, consider the following: About 10% of SHOW participants ages 35 to 74 years had no history of CVD and no indication for aspirin therapy based on the latest USPSTF guidelines, but took aspirin regularly nonetheless. Extrapolating those numbers to the entire state of Wisconsin would suggest that approximately 270,000 state residents have a similar profile. Assuming an extra 1.3 major bleeding events per 1000 person-years of regular aspirin use (as a meta-analysis of studies of adverse events associated with antiplatelet therapy found),27 that would translate into an estimated 350 major bleeding events per year in Wisconsin that are attributable to aspirin overuse.

In view of the current USPSTF recommendations,10 aspirin is not optimally utilized by Wisconsin residents for the primary prevention of CVD. Aspirin therapy is not used enough by those with a high CVD risk, who could derive substantial vascular disease protection from it. Conversely, aspirin therapy is overused by those with a low CVD risk, for whom the risk of major bleeding is significantly higher than the potential for vascular disease protection. Furthermore, younger individuals at high CVD risk appear to be least likely to take aspirin regularly.

Recommendations

The strongest modifiable predictor of regular aspirin use is a recommendation from a clinician.13 Therefore, we recommend stronger primary care initiatives to ensure that patients are screened for aspirin use more frequently, particularly middle-aged men at high CVD risk. This clinic-based initiative could reach a larger proportion of the general population when combined with broader, community-oriented CVD preventive services.28

More precise marketing and education are also needed. Because aspirin is a low-cost over-the-counter product that leads the consumer market for analgesics,29 the general public (and older, non-Hispanic whites, in particular) needs to be better informed about the risks of medically inappropriate aspirin use for primary CVD prevention.

Study limitations

Selection and measurement biases were among the chief study limitations.

Study (SHOW) enrollment rate was slightly above 50%, with steady increases in enrollment each year (from 46% in 2008-2009 to 56% in 2010) due to expanded recruitment and consolidation of field operations.

Aspirin use was self-reported, and SHOW did not capture the reason for taking it (eg, CVD prevention or pain management). Some evidence of overreporting of aspirin use among older individuals exists,30 suggesting that a more objective measure of aspirin use (eg, pill bottle verification or blood platelet aggregation test) could yield different results.