User login

In reply: Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression

In Reply: We thank Drs. Rodríguez-Gutiérrez and Gonzálvez-Gonzálvez and Dr. Keller for their thoughtful comments.

In our paper, we did not elaborate on the low-dose cosyntropin stimulation test. The 1-μg test, in particular, has been shown to have similar or better sensitivity, with similar or lower specificity, compared with the 250-μg dose, depending on the study design. Unfortunately, the administration of the 1-μg dose presents more technical difficulty than the 250-μg dose, thus limiting its use. Cosyntropin (used in the United States) comes in a vial with 250 μg of powder. This must be reconstituted with 250 mL of normal saline, and only 1 mL is to be given. Adherence to the plastic tubing may occur, and more precise timing is needed as the cortisol levels may decrease.1–3

Responding to Dr. Keller, we were unable to find any systematic reviews comparing inhaled corticosteroids that have a “higher therapeutic index” as a class vs older inhaled corticosteroids. There are several studies, however, comparing individual inhaled corticosteroid preparations with each other in terms of adrenal effects, and we feel that it is beyond the scope of this response to perform a systematic analysis. In addition, the determination of adrenal function used in studies comparing one inhaled corticosteroid with another were varied, including cosyntropin stimulation tests and surrogates such as the urinary cortisolcreatinine ratio, a morning plasma cortisol level less than 5 μg/L, and serum cortisol concentration curves, preventing more definitive conclusions even if the data were to be pooled.4–6 A double-blind, randomized study comparing the adrenal effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone showed a smaller reduction in the peak serum cortisol level achieved with ciclesonide compared with fluticasone, in both low-dose and high-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests, with the results in the ciclesonide group being similar to placebo.7 However, the mean peak serum cortisol levels after exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids were not presented in table format, and the results have to be inferred from the figures and the narrative description of the baseline mean peak cortisol levels8 (ie, before exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids). Case reports have suggested that changing the inhaled corticostseroid formulation from fluticasone to ciclesonide allowed for improvement of adrenal function.8 The purported mechanism of decreased adrenal effects of ciclesonide is its greater deposition in the lungs and, hence, less entry into the systemic circulation and fewer systemic adverse effects.9

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenalin sufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- Dickstein G. High-dose and low-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests for diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:312–314.

- Rose SR, Lustig RH, Burstein S, Pitukcheewanont P, Broome DC, Burthen GA. Diagnosis of ACTH deficiency. Comparison of overnight metyrapone test to either low-dose or high-dose ACTH test. Horm Res 1999; 52:73–79.

- Chrousos GP, Ghaly L, Shedden A, Iezzoni DG, Harris AG. Effects of mometasone furoate dry powder inhaler and beclomethasone dipropionate hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in asthmatic subjects. Chest 2005; 128:70–77.

- White M, Crisalida T, Li H, Economides A, Kaliner M. Effects of long-term inhaled corticosteroids on adrenal function in asthmatics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96:437–444.

- Fardon TC, Lee DK, Haggart K, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Adrenal suppression with dry powder formulations of fluticasone propionate and mometasone furoate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:960–966.

- Lipworth BJ, Kaliner MA, LaForde CF, et al. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adults with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 94:465–472.

- Heller MK, Laks J, Kovesi TA, Ahmet A. Reversal of adrenal suppression with ciclesonide. J Asthma 2010; 47:337–339.

- Kaliner MA. Pharmacologic characteristics and adrenal suppression with newer inhaled corticosteroids: a comparison of ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate. Clin Ther 2006; 28:319–3.

In Reply: We thank Drs. Rodríguez-Gutiérrez and Gonzálvez-Gonzálvez and Dr. Keller for their thoughtful comments.

In our paper, we did not elaborate on the low-dose cosyntropin stimulation test. The 1-μg test, in particular, has been shown to have similar or better sensitivity, with similar or lower specificity, compared with the 250-μg dose, depending on the study design. Unfortunately, the administration of the 1-μg dose presents more technical difficulty than the 250-μg dose, thus limiting its use. Cosyntropin (used in the United States) comes in a vial with 250 μg of powder. This must be reconstituted with 250 mL of normal saline, and only 1 mL is to be given. Adherence to the plastic tubing may occur, and more precise timing is needed as the cortisol levels may decrease.1–3

Responding to Dr. Keller, we were unable to find any systematic reviews comparing inhaled corticosteroids that have a “higher therapeutic index” as a class vs older inhaled corticosteroids. There are several studies, however, comparing individual inhaled corticosteroid preparations with each other in terms of adrenal effects, and we feel that it is beyond the scope of this response to perform a systematic analysis. In addition, the determination of adrenal function used in studies comparing one inhaled corticosteroid with another were varied, including cosyntropin stimulation tests and surrogates such as the urinary cortisolcreatinine ratio, a morning plasma cortisol level less than 5 μg/L, and serum cortisol concentration curves, preventing more definitive conclusions even if the data were to be pooled.4–6 A double-blind, randomized study comparing the adrenal effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone showed a smaller reduction in the peak serum cortisol level achieved with ciclesonide compared with fluticasone, in both low-dose and high-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests, with the results in the ciclesonide group being similar to placebo.7 However, the mean peak serum cortisol levels after exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids were not presented in table format, and the results have to be inferred from the figures and the narrative description of the baseline mean peak cortisol levels8 (ie, before exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids). Case reports have suggested that changing the inhaled corticostseroid formulation from fluticasone to ciclesonide allowed for improvement of adrenal function.8 The purported mechanism of decreased adrenal effects of ciclesonide is its greater deposition in the lungs and, hence, less entry into the systemic circulation and fewer systemic adverse effects.9

In Reply: We thank Drs. Rodríguez-Gutiérrez and Gonzálvez-Gonzálvez and Dr. Keller for their thoughtful comments.

In our paper, we did not elaborate on the low-dose cosyntropin stimulation test. The 1-μg test, in particular, has been shown to have similar or better sensitivity, with similar or lower specificity, compared with the 250-μg dose, depending on the study design. Unfortunately, the administration of the 1-μg dose presents more technical difficulty than the 250-μg dose, thus limiting its use. Cosyntropin (used in the United States) comes in a vial with 250 μg of powder. This must be reconstituted with 250 mL of normal saline, and only 1 mL is to be given. Adherence to the plastic tubing may occur, and more precise timing is needed as the cortisol levels may decrease.1–3

Responding to Dr. Keller, we were unable to find any systematic reviews comparing inhaled corticosteroids that have a “higher therapeutic index” as a class vs older inhaled corticosteroids. There are several studies, however, comparing individual inhaled corticosteroid preparations with each other in terms of adrenal effects, and we feel that it is beyond the scope of this response to perform a systematic analysis. In addition, the determination of adrenal function used in studies comparing one inhaled corticosteroid with another were varied, including cosyntropin stimulation tests and surrogates such as the urinary cortisolcreatinine ratio, a morning plasma cortisol level less than 5 μg/L, and serum cortisol concentration curves, preventing more definitive conclusions even if the data were to be pooled.4–6 A double-blind, randomized study comparing the adrenal effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone showed a smaller reduction in the peak serum cortisol level achieved with ciclesonide compared with fluticasone, in both low-dose and high-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests, with the results in the ciclesonide group being similar to placebo.7 However, the mean peak serum cortisol levels after exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids were not presented in table format, and the results have to be inferred from the figures and the narrative description of the baseline mean peak cortisol levels8 (ie, before exposure to these inhaled corticosteroids). Case reports have suggested that changing the inhaled corticostseroid formulation from fluticasone to ciclesonide allowed for improvement of adrenal function.8 The purported mechanism of decreased adrenal effects of ciclesonide is its greater deposition in the lungs and, hence, less entry into the systemic circulation and fewer systemic adverse effects.9

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenalin sufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- Dickstein G. High-dose and low-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests for diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:312–314.

- Rose SR, Lustig RH, Burstein S, Pitukcheewanont P, Broome DC, Burthen GA. Diagnosis of ACTH deficiency. Comparison of overnight metyrapone test to either low-dose or high-dose ACTH test. Horm Res 1999; 52:73–79.

- Chrousos GP, Ghaly L, Shedden A, Iezzoni DG, Harris AG. Effects of mometasone furoate dry powder inhaler and beclomethasone dipropionate hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in asthmatic subjects. Chest 2005; 128:70–77.

- White M, Crisalida T, Li H, Economides A, Kaliner M. Effects of long-term inhaled corticosteroids on adrenal function in asthmatics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96:437–444.

- Fardon TC, Lee DK, Haggart K, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Adrenal suppression with dry powder formulations of fluticasone propionate and mometasone furoate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:960–966.

- Lipworth BJ, Kaliner MA, LaForde CF, et al. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adults with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 94:465–472.

- Heller MK, Laks J, Kovesi TA, Ahmet A. Reversal of adrenal suppression with ciclesonide. J Asthma 2010; 47:337–339.

- Kaliner MA. Pharmacologic characteristics and adrenal suppression with newer inhaled corticosteroids: a comparison of ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate. Clin Ther 2006; 28:319–3.

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenalin sufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- Dickstein G. High-dose and low-dose cosyntropin stimulation tests for diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:312–314.

- Rose SR, Lustig RH, Burstein S, Pitukcheewanont P, Broome DC, Burthen GA. Diagnosis of ACTH deficiency. Comparison of overnight metyrapone test to either low-dose or high-dose ACTH test. Horm Res 1999; 52:73–79.

- Chrousos GP, Ghaly L, Shedden A, Iezzoni DG, Harris AG. Effects of mometasone furoate dry powder inhaler and beclomethasone dipropionate hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in asthmatic subjects. Chest 2005; 128:70–77.

- White M, Crisalida T, Li H, Economides A, Kaliner M. Effects of long-term inhaled corticosteroids on adrenal function in asthmatics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96:437–444.

- Fardon TC, Lee DK, Haggart K, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Adrenal suppression with dry powder formulations of fluticasone propionate and mometasone furoate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:960–966.

- Lipworth BJ, Kaliner MA, LaForde CF, et al. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adults with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 94:465–472.

- Heller MK, Laks J, Kovesi TA, Ahmet A. Reversal of adrenal suppression with ciclesonide. J Asthma 2010; 47:337–339.

- Kaliner MA. Pharmacologic characteristics and adrenal suppression with newer inhaled corticosteroids: a comparison of ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate. Clin Ther 2006; 28:319–3.

Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression

To the Editor: Drs. Lansang and Hustak1 provide a comprehensive and useful review of steroid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression.

In their section on local steroids, they discuss the side effects of topical and inhaled glucocorticosteroids. Much has been made of the fact that certain steroids, such as mometasone (Elocon, Nasonex) and fluticasone (Flonase), have a higher “therapeutic index” or ratio of local anti-inflammatory effect to systemic side effects, due to extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism, than older agents such as beclomethasone (Qvar) and betamethasone (Diprosone).2 Ciclesonide (Alvesco, Omnaris), a newer inhaled steroid, is said to have an enhanced therapeutic index because it is a prodrug that is activated by metabolism in the lungs; it reportedly has an even less suppressive effect on hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis function.3

Are the authors aware of any other evidence that clinical outcome, such as adrenal suppression or hyperglycemia, is improved by the use of steroids with a higher therapeutic index?

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Drug Bank. Mometasone. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00764. Accessed February 17, 2012.

- Derom E, Louis R, Tiesler C, Engelsätter R, Kaufman JM, Joos GF. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on cortisol secretion in patients with persistent asthma. Eur Respir J 2009; 33:1277–1286.

To the Editor: Drs. Lansang and Hustak1 provide a comprehensive and useful review of steroid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression.

In their section on local steroids, they discuss the side effects of topical and inhaled glucocorticosteroids. Much has been made of the fact that certain steroids, such as mometasone (Elocon, Nasonex) and fluticasone (Flonase), have a higher “therapeutic index” or ratio of local anti-inflammatory effect to systemic side effects, due to extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism, than older agents such as beclomethasone (Qvar) and betamethasone (Diprosone).2 Ciclesonide (Alvesco, Omnaris), a newer inhaled steroid, is said to have an enhanced therapeutic index because it is a prodrug that is activated by metabolism in the lungs; it reportedly has an even less suppressive effect on hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis function.3

Are the authors aware of any other evidence that clinical outcome, such as adrenal suppression or hyperglycemia, is improved by the use of steroids with a higher therapeutic index?

To the Editor: Drs. Lansang and Hustak1 provide a comprehensive and useful review of steroid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression.

In their section on local steroids, they discuss the side effects of topical and inhaled glucocorticosteroids. Much has been made of the fact that certain steroids, such as mometasone (Elocon, Nasonex) and fluticasone (Flonase), have a higher “therapeutic index” or ratio of local anti-inflammatory effect to systemic side effects, due to extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism, than older agents such as beclomethasone (Qvar) and betamethasone (Diprosone).2 Ciclesonide (Alvesco, Omnaris), a newer inhaled steroid, is said to have an enhanced therapeutic index because it is a prodrug that is activated by metabolism in the lungs; it reportedly has an even less suppressive effect on hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis function.3

Are the authors aware of any other evidence that clinical outcome, such as adrenal suppression or hyperglycemia, is improved by the use of steroids with a higher therapeutic index?

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Drug Bank. Mometasone. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00764. Accessed February 17, 2012.

- Derom E, Louis R, Tiesler C, Engelsätter R, Kaufman JM, Joos GF. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on cortisol secretion in patients with persistent asthma. Eur Respir J 2009; 33:1277–1286.

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Drug Bank. Mometasone. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00764. Accessed February 17, 2012.

- Derom E, Louis R, Tiesler C, Engelsätter R, Kaufman JM, Joos GF. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone on cortisol secretion in patients with persistent asthma. Eur Respir J 2009; 33:1277–1286.

Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression

To the Editor: We found the article by Drs. Lansang and Kramer1 on glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression in the November 2011 issue to be a useful and clinically oriented review. However, we strongly believe there is an issue that should be addressed.

It is well accepted that the short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test is the best screening maneuver for assessing adrenocortical insufficiency. The authors state, however, that 250 μg is preferable to lower doses (10 μg or 1 μg), since these are not yet widely accepted, and refer to an article by Axelrod from 1976.2

Based on studies showing that 250 μg of cosyntropin is a pharmacologic rather than a physiologic stimulus that may overstimulate partially atrophied or mildly dysfunctional adrenal glands, multiple studies in the last 20 years have shown that the low-dose test has an equal or better result than the classic 250-μg dose test.3 Dorin et al,4 in a meta-analysis of the diagnosis of adrenocortical insufficiency that included more than 30 studies, found similar sensitivity and specificity in primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency comparing the 250-μg dose vs the low dose. In cases of mild primary adrenal failure, the low-dose test has better performance. A previous investigation in our research center contrasting 250 μg vs 10 μg proved that 10 μg had a better sensitivity than the standard dose, with excellent reproducibility and interchangeability.5 Similar findings have been shown by other authors contrasting 1 μg vs 250 μg of cosyntropin.6

We believe that the limited use of the low-dose cosyntropin test is not a matter of acceptance or performance but a consequence of the lack of vials containing lower doses of cosyntropin (1 to 10 μg), which makes this test technically challenging.2,4 The steps needed for one-dose testing and the preservation time of the preparation are strong limitations to its wide use in clinical practice and endocrine laboratories.

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Axelrod L. Glucocorticoid therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:39–65.

- Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991; 72:773–778.

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- González-González JG, De la Garza-Hernández NE, Mancillas-Adame LG, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ. A high-sensitivity test in the assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency: 10 microg vs 250 microg cosyntropin dose assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency. J Endocrinol 1998; 159:275–280.

- Abdu TA, Elhadd TA, Neary R, Clayton RN. Comparison of the low dose short synacthen test (1 microg), the conventional dose short synacthen test (250 microg), and the insulin tolerance test for assessment of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:838–843.

To the Editor: We found the article by Drs. Lansang and Kramer1 on glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression in the November 2011 issue to be a useful and clinically oriented review. However, we strongly believe there is an issue that should be addressed.

It is well accepted that the short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test is the best screening maneuver for assessing adrenocortical insufficiency. The authors state, however, that 250 μg is preferable to lower doses (10 μg or 1 μg), since these are not yet widely accepted, and refer to an article by Axelrod from 1976.2

Based on studies showing that 250 μg of cosyntropin is a pharmacologic rather than a physiologic stimulus that may overstimulate partially atrophied or mildly dysfunctional adrenal glands, multiple studies in the last 20 years have shown that the low-dose test has an equal or better result than the classic 250-μg dose test.3 Dorin et al,4 in a meta-analysis of the diagnosis of adrenocortical insufficiency that included more than 30 studies, found similar sensitivity and specificity in primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency comparing the 250-μg dose vs the low dose. In cases of mild primary adrenal failure, the low-dose test has better performance. A previous investigation in our research center contrasting 250 μg vs 10 μg proved that 10 μg had a better sensitivity than the standard dose, with excellent reproducibility and interchangeability.5 Similar findings have been shown by other authors contrasting 1 μg vs 250 μg of cosyntropin.6

We believe that the limited use of the low-dose cosyntropin test is not a matter of acceptance or performance but a consequence of the lack of vials containing lower doses of cosyntropin (1 to 10 μg), which makes this test technically challenging.2,4 The steps needed for one-dose testing and the preservation time of the preparation are strong limitations to its wide use in clinical practice and endocrine laboratories.

To the Editor: We found the article by Drs. Lansang and Kramer1 on glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression in the November 2011 issue to be a useful and clinically oriented review. However, we strongly believe there is an issue that should be addressed.

It is well accepted that the short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test is the best screening maneuver for assessing adrenocortical insufficiency. The authors state, however, that 250 μg is preferable to lower doses (10 μg or 1 μg), since these are not yet widely accepted, and refer to an article by Axelrod from 1976.2

Based on studies showing that 250 μg of cosyntropin is a pharmacologic rather than a physiologic stimulus that may overstimulate partially atrophied or mildly dysfunctional adrenal glands, multiple studies in the last 20 years have shown that the low-dose test has an equal or better result than the classic 250-μg dose test.3 Dorin et al,4 in a meta-analysis of the diagnosis of adrenocortical insufficiency that included more than 30 studies, found similar sensitivity and specificity in primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency comparing the 250-μg dose vs the low dose. In cases of mild primary adrenal failure, the low-dose test has better performance. A previous investigation in our research center contrasting 250 μg vs 10 μg proved that 10 μg had a better sensitivity than the standard dose, with excellent reproducibility and interchangeability.5 Similar findings have been shown by other authors contrasting 1 μg vs 250 μg of cosyntropin.6

We believe that the limited use of the low-dose cosyntropin test is not a matter of acceptance or performance but a consequence of the lack of vials containing lower doses of cosyntropin (1 to 10 μg), which makes this test technically challenging.2,4 The steps needed for one-dose testing and the preservation time of the preparation are strong limitations to its wide use in clinical practice and endocrine laboratories.

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Axelrod L. Glucocorticoid therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:39–65.

- Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991; 72:773–778.

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- González-González JG, De la Garza-Hernández NE, Mancillas-Adame LG, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ. A high-sensitivity test in the assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency: 10 microg vs 250 microg cosyntropin dose assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency. J Endocrinol 1998; 159:275–280.

- Abdu TA, Elhadd TA, Neary R, Clayton RN. Comparison of the low dose short synacthen test (1 microg), the conventional dose short synacthen test (250 microg), and the insulin tolerance test for assessment of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:838–843.

- Lansang MC, Hustak LK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and adrenal suppression: how to detect and manage them. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:748–756.

- Axelrod L. Glucocorticoid therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:39–65.

- Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991; 72:773–778.

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM. Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:194–204.

- González-González JG, De la Garza-Hernández NE, Mancillas-Adame LG, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ. A high-sensitivity test in the assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency: 10 microg vs 250 microg cosyntropin dose assessment of adrenocortical insufficiency. J Endocrinol 1998; 159:275–280.

- Abdu TA, Elhadd TA, Neary R, Clayton RN. Comparison of the low dose short synacthen test (1 microg), the conventional dose short synacthen test (250 microg), and the insulin tolerance test for assessment of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:838–843.

Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs: The emerging ‘incense’ and ‘bath salt’ phenomenon

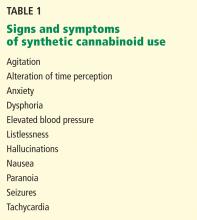

Over the past year, it has been hard to avoid news reports involving people getting high on “bath salts” and “incense” (also known as “Spice” or “K2”). Addiction treatment professionals have been overwhelmed by questions regarding why one would want to “snort bath salts” or “smoke incense.”

These substances are not what they appear to be. They are sold as bath salts and incense and are labeled “not for human consumption” simply to avoid regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In reality, they are powerful psychoactive drugs, with effects that mimic those of more commonly abused drugs such as amphetamines and marijuana. Until recently, they were legally available over the counter at quick-marts, head shops, and on the Internet. Because they are relatively new, they may not be detectable on routine urine drug screens, and users may be unaware of the specific chemicals contained in them.

These drugs, which we have collectively termed synthetic legal intoxicating drugs (SLIDs), are increasing dramatically in use.1–3 A survey of youths at a rave party indicated that 21% had used one of them on at least one occasion.4 The general impression held by the drug-using public is that SLIDs are relatively cheap, are not detected on standard urine drug screens, can produce a powerful high, and, until recently, were readily available through legitimate sources.

Physicians need to be aware of SLIDs in order to recognize and manage the intoxication syndromes associated with these substances when encountered in clinical practice, and in order to educate patients about their potential dangers.

SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS MARKETED AS INCENSE

Herbal incense products that could be smoked as an alternative to marijuana started appearing on the Internet in Europe in 2004. By 2008, when such products first appeared in the United States, their use in Europe was already widespread.

Initially, consumers were led to believe that such herbal smoking blends were safe, legal alternatives to marijuana, and that it was the proprietary blend of herbs that was responsible for the “natural” high. Spice, a specific brand name, was originally trademarked in England as incense and also as an herbal smoking product.5

Legal authorities, however, suspected that these herbal blends were adulterated with synthetic substances. In December 2008, the first such substance was found when Austrian authorities isolated a synthetic cannabinoid, JWH-018, from an herbal incense product.6 By the end of 2009, five other synthetic cannabinoids—CP-47,497, HU-210, JWH-073, JWH-250, and JWH-398—had been isolated from various herbal incense samples around the world.7

The synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products are not derived from the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa), but are synthesized in laboratories and are formulated to interact with the endogenous cannabinoid receptors in the brain to produce psychoactive effects.

Synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists; natural THC is only a partial agonist

Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been discovered in humans: CB1 and CB2. Both types are found in the central nervous system, and CB2 is also found extensively in the periphery. CB1 is the receptor responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabinoids, including altered consciousness, euphoria, relaxation, perceptual disturbances, intensified sensory experiences, cognitive impairment, and increased reaction time.6 The physiologic role of CB2 remains uncertain.

The major psychoactive cannabinoid in naturally occurring marijuana is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The so-called classic cannabinoids, such as HU-210, are analogues of THC and are based on its chemical structure. The rest of the synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products differ in chemical structure from naturally occurring cannabinoids such as THC, but have activity at the CB1 receptor and are thus psychoactive.

Of clinical relevance is that THC is only a partial agonist at the CB1 receptor, while all synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products are full agonists at CB1.7 This difference is important because partial agonists bind to receptors but stimulate them only partially and therefore exhibit a plateau effect in terms of dose vs clinical response. In contrast, full agonists have no ceiling on the dose-response relationship and therefore have a greater potential for overdose and severe toxic effects.

Despite uncertainties, use is widespread

Most of the synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products were developed for research purposes, and there are almost no reliable scientific data on their effects in humans. Of additional concern is that no research has been conducted on their pyrolytic effects, ie, how these chemicals are transformed when they are burned, such as when consumers smoke them. Furthermore, herbal incense products often vary in their active substances and concentrations, so consumers really do not know what they are getting.

Despite the many uncertainties, the use of these products is widespread. Data submitted to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from a major toxicology laboratory indicated that from July through November of 2010, 3,700 samples tested positive for either JWH-018 or JWH-073. This report also indicated that 30% to 35% of specimens submitted by juvenile probation departments were positive for synthetic cannabinoids.8

MEDICAL CONCERNS OVER SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS

Amid the mysteries surrounding synthetic cannabinoids, one thing is clear: users are increasingly seeking medical attention. In 2010, there were 2,906 calls to poison control centers across the United States pertaining to “synthetic marijuana”; in 2011 there were 6,959 calls, and in January 2012, 639 such calls had been placed.9

The duration of the intoxicating effects of synthetic cannabinoids is generally longer than that of THC, but this seems to be variable. JWH-018, for instance, seems to have a shorter duration of action, at around 1 to 2 hours, while a longer, 5- to 6-hour intoxicating effect has been observed with CP-47,497.7,12

Serious adverse effects

Although the prevalence of serious adverse effects associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids is not known, a number of serious complications have been recognized.

Seizures. One case of seizure has been reported in association with the use of synthetic cannabinoids, specifically JWH-018.12 This case involved a previously healthy 48-year-old man who had ingested a powder that was subsequently confirmed to be JWH-018, which he mixed with alcohol. Of further concern in this case is that this individual developed a refractory supraventricular tachycardia that required cardioversion on the first hospital day.

The authors speculated that the seizure may have been due to a dose-response mechanism that resulted in either the release of presynaptic excitatory neurotransmitters or the decreased release of inhibitory neurotransmitters. They further postulated that the supraventricular tachycardia could have been caused by one of two mechanisms previously reported in association with CB1 agonists: an increase in circulating catecholamines or heightened oxidative demands on the myocardium.12

Psychosis. The occurrence of psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions in association with synthetic cannabinoids is not surprising, given the well-documented link between marijuana use and psychosis.13,14

A case report of a 25-year-old patient with a 7-year history of recurrent psychosis that was initially triggered by cannabis use indicated that the use of 3 g of herbal incense on three occasions was associated with worsening of previous psychotic symptoms and the emergence of command and paranoid types of auditory hallucination.10

Semistructured interviews of 15 patients in a forensic rehabilitative service, all of whom had a history of psychotic illness, showed that 69% experienced symptoms consistent with psychotic relapse after smoking an herbal incense product containing JWH-018.15

It is possible that psychotic symptoms may be more prominent with synthetic cannabinoids than with natural marijuana because not only are synthetic cannabinoids more potent and work as full agonists, but, unlike marijuana, they do not contain cannabidiol, which is thought to have antipsychotic efficacy.10,16 However, the risk of psychotic symptoms in association with synthetic cannabinoid usage in otherwise healthy people is unknown.

Regulation lags behind

Growing concern over the perceived dangers posed by synthetic cannabinoids has led to a ban on some of the more common ones contained in herbal incense preparations. On March 1, 2011, the US DEA temporarily placed five synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47,497, and cannabicyclohexanol) under schedule I (banned substances).

Such a ban, however, may be futile because there are an estimated 100 synthetic cannabinoids that have yet to enter the market, and when one is banned, a new one is likely to be introduced immediately as a replacement.8

SYNTHETIC STIMULANTS MARKETED AS BATH SALTS

Like the herbal incense products, “bath salts” may likewise not be what they appear to be. They too may be labeled “not for human consumption” in an effort to bypass laws governing mind-altering substances.

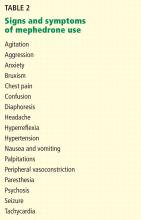

Several pharmacologically active substances have been marketed as bath salts. Two of the more common ingredients are 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and 4-methylcathinone (mephedrone).

MDPV is a dopamine and norepineph-rine reuptake inhibitor that acts as a powerful stimulant. It has no FDA-approved medical use, but it is an analogue of the stimulant pyrovalerone, which was once used to treat chronic fatigue.17

MDPV seems to be the most common substance found in bath salt products in the United States. A sample of this substance was first seized on the streets by German authorities in 2007. A study in Finland conducted from August 2009 to September 2010 estimated that 5.7% of all arrests for driving under the influence (DUI) unrelated to alcohol consumption involved MDPV intoxication.17 In 2009, the National Forensic Laboratory Information System of the US DEA had seized only two samples of MDPV, but by 2010 that had increased to 161.18

Mephedrone is derived from phenethylamine and is closely related to cathinone, the active ingredient in the African khat plant (Catha edulis).19 Khat has a history of abuse, and the chemical structure of cathinone and its derivatives is similar to that of amphetamine.

Mephedrone, a powerful stimulant, is suspected of working as a monoamine reuptake inhibitor, and it may also directly induce the presynaptic release of monoamines.20 The net effect is an increase in serotonin, norepineph-rine, and dopamine levels at neuronal synapses.

Mephedrone was first described in 1929 by chemist Saem de Burnaga Sanchez, and it remained an obscure research chemical for many years.21 It was formally recognized as a drug of abuse in Europe in 2007, and by 2009 it was the sixth most frequently used such drug in Europe.8,22

Although MDPV and mephedrone are the most common psychoactive ingredients in bath salts, many other synthetic drugs have been found on the market.

A temporary ban

On September 7, 2011, the US government made it illegal to possess or sell any substance containing MDPV, mephedrone, or methy-lone. This temporary restriction was to remain in effect for 1 year to give the DEA time to collect data to support a move to permanently control these substances.3

Like synthetic cannabinoids, however, synthetic stimulants are very difficult to regulate because they are a large group of substances. As soon as one substance is outlawed, another synthetic stimulant will likely take its place.

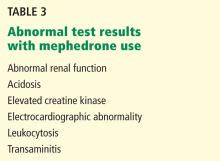

MEDICAL CONCERNS REGARDING SYNTHETIC STIMULANTS

The medical and psychiatric sequelae that are associated with the use of bath salts have sent an increasing number of people to emergency rooms. The number of bath-salt-related calls to US poison control centers increased dramatically from 303 in 2010 to 4,720 by August 31, 2011. Most of these calls were related to tachycardia, agitation, hallucinations, extreme paranoia, delusions, and elevations in blood pressure.3

A report of 35 cases of people who had used bath salts and who had reported to Michigan emergency rooms between November 13, 2010, and March 31, 2011, indicated that agitation was present in 66%, tachycardia in 63%, delusions and hallucinations in 40%, seizure or tremor in 29%, hypertension in 23%, drowsiness in 23%, paranoia in 20%, and mydriasis in 20%; one patient was dead on arrival. Of the 34 patients who were alive on arrival, 17 (50%) were hospitalized, 15 were released, and 2 left against medical advice. In the patients in this study, 63% had injected the drug, 26% snorted it, and 11% ingested it orally.2 Toxicology results obtained during an autopsy on the one person who died revealed a high level of MDPV, and the coroner ruled that MDPV toxicity was the primary cause of death.2

Though the pharmacokinetic properties of mephedrone are unknown, James et al24 noted that an interesting feature is that its clinical effects seem to persist for more than 24 hours after the last exposure to the drug, which would not be expected based on the rapid elimination of other similar cathinones.

Sympathomimetic toxicity. Many of the symptoms listed in Table 2 are consistent with a sympathomimetic syndrome. In a case series reported by Regan et al,26 most of the 57 patients exhibited cardiovascular findings consistent with sympathomimetic toxicity.

In the study by James et al,24 one of the patients with chest pain had electrocardiographic changes consistent with acute myocardial infarction. Though it is not possible to conclude from a single case that mephedrone poses a risk of myocardial infarction, such a risk has been reported with khat.28 More research is needed to determine whether mephedrone poses a risk of cardiac events when used by people with or without an underlying cardiac condition.

Seizure also seems to be a relatively common feature associated with mephedrone use in case series of emergency room presentations. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention l2 reported that of 35 patients who had used bath salts, 40% experienced seizures or “tremors.” A recent case series27 of 15 patients presenting to an emergency department after mephedrone use reported that 20% had experienced seizures. In the study by James et al,24 four patients (3% of the total group) experienced seizures after using mephedrone. It should be noted that, aside from people presenting to emergency rooms, seizures are rarely reported in the wider population of mephedrone users.

Psychotic symptoms are also quite common in users of synthetic stimulants who present to emergency rooms, occurring, as previously stated, in 14% to 40% of cases.2,24

In a small case series, Penders and Gestring29 pointed out some common features in three patients who had used MDPV and had presented with psychosis: sleep problems, inattention, vivid hallucinations of intruders, fearfulness, and inability to remember many of the events surrounding their drug use. The authors concluded that the psychotic syndrome present in their three patients was indicative of a short-term delirium rather than a substance-induced psychosis based on the presence of attention deficits and memory problems. The patients in this series responded well to brief hospitalization and antipsychotic medications.

As with seizure, extreme presentations such as psychosis are infrequently mentioned except in people requiring treatment at a hospital. There are simply no data regarding the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in the larger group of all synthetic stimulant users.

SUSPECT SLID INTOXICATION IN ‘PSYCHIATRIC’ PATIENTS

Despite the temporary ban on the more common substances found in Spice and bath salts, it is premature for the medical community to breath a sigh of relief. Producers of these products are already likely bringing to market new ones containing similar but as yet nonbanned substances. Furthermore, such bans will do little to affect Internet commerce; rather than go to a head shop, consumers will order the products online.

Doctors in urgent care centers, emergency rooms, and on general medical floors should pay close attention to any patient without a known psychiatric history who is acting in a bizarre fashion. Most SLID-intoxicated patients will present with anxiety, agitation, and psychosis. Rather than assume that they are psychiatric patients, one should consider the possibility of SLID intoxication and pay close attention to the possible medical sequelae associated with SLID use, such as elevated blood pressure, tachycardia, and seizure.

Benzodiazepines, especially lorazepam (Ativan), have been the agents most commonly used to treat both agitation and seizures associated with SLID intoxication.

Antipsychotics should be used judiciously because of their propensity to lower the seizure threshold, and patients with synthetic stimulant toxicity are already at increased risk of seizure.

A psychiatric consult should be considered in the event of any suspected toxicity or for any patient whose behavior is difficult to manage.

Restraints may be needed in some circumstances when agitation cannot be controlled with benzodiazepines alone, to ensure safety for the patient as well as that of others in the emergency department.

Routine laboratory tests should be part of the workup of patients suspected of being under the influence of SLIDs. These include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and urine toxicology (Table 3).23,25 A routine urine toxicology study will likely be negative, but either the patient or collateral information may give you a general idea of what the patient used, in which case the sample could be sent out for special tests for the more common substances found in herbal incense or bath salt products.

Electroencephalography may be indicated if there is any question as to whether the patient may have suffered a seizure. There should be a low threshold to order electrocardiography, especially in the case of synthetic stimulant intoxication.

Serial cardiac enzymes may be warranted if a patient with synthetic-stimulant intoxicated has chest pain.

Education, addiction treatment. Much is unknown about the risk of SLIDs, but given the adverse events reported in the literature, it seems likely that those with underlying cardiac or psychiatric issues may be at higher risk for the most serious drug-related consequences. With regard to synthetic stimulants, Winstock et al20 recommend a harm-reduction approach involving educating patients about avoiding the development of tolerance, not engaging in polydrug use, not injecting, and paying special attention to remaining cool and well hydrated.

Experience shows that once SLID patients get through their acute crisis and are no longer psychotic, they tend to be forthright in divulging what they used to get high. At that point, consideration should be given to consulting an addiction treatment specialist for further evaluation of the patient’s drug use history and for formulation of a treatment plan to help ensure that the patient doesn’t return to using these drugs.

SLIDs POSE A REAL CHALLENGE

SLIDs present a real challenge to law enforcement, governments, the public, and the addiction treatment community. There is currently no way to routinely test for these substances. Furthermore, any tests that are developed or laws that are enacted will be easily evaded, as there are many more synthetic substances waiting in the wings to be released.

Don’t be lulled into thinking that SLIDs are gone with the recent bans against some of the more common substances. More SLIDs are coming, and more morbidity should be expected in medical settings.

Doctors in emergency departments and other settings need to be prepared for the agitated and often psychotic presentation of SLID-intoxicated patients and should be ready with benzodiazepines, restraints, and a calm and reassuring manner. And for patients who present with psychotic symptoms, medical staff should also be ready to consider involuntary short-term commitment to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Once they recover, patients need to be educated about the dangers of substances such as SLIDs that, because of their novelty, may be perceived as less dangerous alternatives to traditional illicit drugs.

- Wehrman J. Fake marijuana spurs more than 4,500 calls to US poison centers. American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC), May 12, 2011. http://www.aapcc.org/dnn/Portals/0/prrel/updatedk2-may112011.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency department visits after use of a drug sold as “bath salts”—Michigan, November 13, 2010–March 31, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60( 19):624–627.

- Canton L. Poison control centers applaud DEA’s ban of bath salts. American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC). September 8, 2011. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/root/vumc.php?site=poisoncenter&doc=36028. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- Banta-Green C. “Club drug” use patterns and related behaviors in Seattle, King County. Survey data collected for STEPS (Stemming the Tide of Ecstasy through Prevention Strategies). Report to public health-Seattle, King County, Feb. 9, 2004.

- Erowid EF, Erowid F. Spice & spin-offs: prohibition’s high-tech cannabis substitutes. June 2009. http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/spice_product/spice_product_article1.shtml. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- Cary P. Spice, K2 and the problem of synthetic cannabinoids. Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet 2010; 6:2–3.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. EMCDDA 2009 thematic paper—understanding the ‘Spice’ phenomenon. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2009.

- Rannazzi T. The dangers of synthetic cannabinoids and stimulants. Testimony before the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, United States Senate. April 6, 2011. http://www.justice.gov/dea/speeches/110412_testimony.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. Poison centers report calls about synthetic marijuana. www.AAPCC.org. Accessed February 22, 2012.

- Müller H, Sperling W, Körhrmann M, Huttner HB, Kornhuber J, Maler JM. The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes. Schizophr Res 2010; 118:309–310.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011: 49;760–764.

- Vardakou I, Pistos C, Spiliopoulou CH. Spice drugs as a new trend: mode of action, identification and legislation. Toxicol Lett 2010; 197:157–162.

- Fergusson DM, Poulton R, Smith PF, Boden JM. Cannabis and psychosis. BMJ 2006; 332:172–175.

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2007; 370:319–328.

- Every-Palmer S. Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: an explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011; 117:152–157.

- Huffman JW, Thompson AL, Wilety JL, Martin BR. Synthesis and pharmacology of 1-deoxy analogs of CP-47,497 and CP-55,940. Bioorg Med Chem 2008; 16:322–335.

- Kriikku P, Wilhelm L, Schwarz O, Rintatalo J. New designer drug of abuse: 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). Findings from apprehended drivers in Finland. Forensic Sci Int 2011; 210:195–200.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). (Street names: “bath salts,” Ivory Wave,” “plant fertilizer,” “Vanilla Sky,” “Energy-1”). October 2011. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/mdpv.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- Kalix P. Cathinone, a natural amphetamine. Pharmacol Toxicol 1992; 70:77–86.

- Winstock AR, Marsen J, Mitcheson L. What should be done about mephedrone? BMJ 2010; 340:c1605.

- Saem de Burnaga Sanchez J. Sur un homologue de l’ éphédrine. Bulletin de la Societé Chimique de France 1929; 45:284–286.

- Winstock A, Mitcheson L, Ramsey J, Davies S, Puchnarewicz M, Marsden J. Mephedrone: use, subjective effects and health risks. Addiction 2011; 106:1991–1996.

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction 2011; 106:154–161.

- James D, Adams RD, Spears R, et al; National Poisons Information Service. Clinical characteristics of mephedrone toxicity reported to the UK National Poisons Information Service. Emerg Med J 2011; 28:686–689.

- Wood DM, Davies S, Puchnarewicz M, et al. Recreational use of 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC) with associated sympathomimetic toxicity. J Med Toxicol 2010; 6:327–330.

- Regan L, Mitchelson M, Macdonald C. Mephedrone toxicity in a Scottish emergency department. Emerg Med J 2011; 28:1055–1058.

- Wood DM, Greene SL, Dargan PI. Clinical pattern of toxicity associated with the novel synthetic cathinone mephedrone. Emerg Med J 2011; 28:280–282.

- Al-Motarreb A, Briancon S, Al-Jaber N, et al. Khat chewing is a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction: a case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59:574–581.

- Penders TM, Gestring R. Hallucinatory delirium following use of MDPV: “bath salts.” Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011; 33:525–526.

Over the past year, it has been hard to avoid news reports involving people getting high on “bath salts” and “incense” (also known as “Spice” or “K2”). Addiction treatment professionals have been overwhelmed by questions regarding why one would want to “snort bath salts” or “smoke incense.”

These substances are not what they appear to be. They are sold as bath salts and incense and are labeled “not for human consumption” simply to avoid regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In reality, they are powerful psychoactive drugs, with effects that mimic those of more commonly abused drugs such as amphetamines and marijuana. Until recently, they were legally available over the counter at quick-marts, head shops, and on the Internet. Because they are relatively new, they may not be detectable on routine urine drug screens, and users may be unaware of the specific chemicals contained in them.

These drugs, which we have collectively termed synthetic legal intoxicating drugs (SLIDs), are increasing dramatically in use.1–3 A survey of youths at a rave party indicated that 21% had used one of them on at least one occasion.4 The general impression held by the drug-using public is that SLIDs are relatively cheap, are not detected on standard urine drug screens, can produce a powerful high, and, until recently, were readily available through legitimate sources.

Physicians need to be aware of SLIDs in order to recognize and manage the intoxication syndromes associated with these substances when encountered in clinical practice, and in order to educate patients about their potential dangers.

SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS MARKETED AS INCENSE

Herbal incense products that could be smoked as an alternative to marijuana started appearing on the Internet in Europe in 2004. By 2008, when such products first appeared in the United States, their use in Europe was already widespread.

Initially, consumers were led to believe that such herbal smoking blends were safe, legal alternatives to marijuana, and that it was the proprietary blend of herbs that was responsible for the “natural” high. Spice, a specific brand name, was originally trademarked in England as incense and also as an herbal smoking product.5

Legal authorities, however, suspected that these herbal blends were adulterated with synthetic substances. In December 2008, the first such substance was found when Austrian authorities isolated a synthetic cannabinoid, JWH-018, from an herbal incense product.6 By the end of 2009, five other synthetic cannabinoids—CP-47,497, HU-210, JWH-073, JWH-250, and JWH-398—had been isolated from various herbal incense samples around the world.7

The synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products are not derived from the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa), but are synthesized in laboratories and are formulated to interact with the endogenous cannabinoid receptors in the brain to produce psychoactive effects.

Synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists; natural THC is only a partial agonist

Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been discovered in humans: CB1 and CB2. Both types are found in the central nervous system, and CB2 is also found extensively in the periphery. CB1 is the receptor responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabinoids, including altered consciousness, euphoria, relaxation, perceptual disturbances, intensified sensory experiences, cognitive impairment, and increased reaction time.6 The physiologic role of CB2 remains uncertain.

The major psychoactive cannabinoid in naturally occurring marijuana is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The so-called classic cannabinoids, such as HU-210, are analogues of THC and are based on its chemical structure. The rest of the synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products differ in chemical structure from naturally occurring cannabinoids such as THC, but have activity at the CB1 receptor and are thus psychoactive.

Of clinical relevance is that THC is only a partial agonist at the CB1 receptor, while all synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products are full agonists at CB1.7 This difference is important because partial agonists bind to receptors but stimulate them only partially and therefore exhibit a plateau effect in terms of dose vs clinical response. In contrast, full agonists have no ceiling on the dose-response relationship and therefore have a greater potential for overdose and severe toxic effects.

Despite uncertainties, use is widespread

Most of the synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products were developed for research purposes, and there are almost no reliable scientific data on their effects in humans. Of additional concern is that no research has been conducted on their pyrolytic effects, ie, how these chemicals are transformed when they are burned, such as when consumers smoke them. Furthermore, herbal incense products often vary in their active substances and concentrations, so consumers really do not know what they are getting.

Despite the many uncertainties, the use of these products is widespread. Data submitted to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from a major toxicology laboratory indicated that from July through November of 2010, 3,700 samples tested positive for either JWH-018 or JWH-073. This report also indicated that 30% to 35% of specimens submitted by juvenile probation departments were positive for synthetic cannabinoids.8

MEDICAL CONCERNS OVER SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS

Amid the mysteries surrounding synthetic cannabinoids, one thing is clear: users are increasingly seeking medical attention. In 2010, there were 2,906 calls to poison control centers across the United States pertaining to “synthetic marijuana”; in 2011 there were 6,959 calls, and in January 2012, 639 such calls had been placed.9

The duration of the intoxicating effects of synthetic cannabinoids is generally longer than that of THC, but this seems to be variable. JWH-018, for instance, seems to have a shorter duration of action, at around 1 to 2 hours, while a longer, 5- to 6-hour intoxicating effect has been observed with CP-47,497.7,12

Serious adverse effects

Although the prevalence of serious adverse effects associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids is not known, a number of serious complications have been recognized.

Seizures. One case of seizure has been reported in association with the use of synthetic cannabinoids, specifically JWH-018.12 This case involved a previously healthy 48-year-old man who had ingested a powder that was subsequently confirmed to be JWH-018, which he mixed with alcohol. Of further concern in this case is that this individual developed a refractory supraventricular tachycardia that required cardioversion on the first hospital day.

The authors speculated that the seizure may have been due to a dose-response mechanism that resulted in either the release of presynaptic excitatory neurotransmitters or the decreased release of inhibitory neurotransmitters. They further postulated that the supraventricular tachycardia could have been caused by one of two mechanisms previously reported in association with CB1 agonists: an increase in circulating catecholamines or heightened oxidative demands on the myocardium.12

Psychosis. The occurrence of psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions in association with synthetic cannabinoids is not surprising, given the well-documented link between marijuana use and psychosis.13,14

A case report of a 25-year-old patient with a 7-year history of recurrent psychosis that was initially triggered by cannabis use indicated that the use of 3 g of herbal incense on three occasions was associated with worsening of previous psychotic symptoms and the emergence of command and paranoid types of auditory hallucination.10

Semistructured interviews of 15 patients in a forensic rehabilitative service, all of whom had a history of psychotic illness, showed that 69% experienced symptoms consistent with psychotic relapse after smoking an herbal incense product containing JWH-018.15

It is possible that psychotic symptoms may be more prominent with synthetic cannabinoids than with natural marijuana because not only are synthetic cannabinoids more potent and work as full agonists, but, unlike marijuana, they do not contain cannabidiol, which is thought to have antipsychotic efficacy.10,16 However, the risk of psychotic symptoms in association with synthetic cannabinoid usage in otherwise healthy people is unknown.

Regulation lags behind

Growing concern over the perceived dangers posed by synthetic cannabinoids has led to a ban on some of the more common ones contained in herbal incense preparations. On March 1, 2011, the US DEA temporarily placed five synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47,497, and cannabicyclohexanol) under schedule I (banned substances).

Such a ban, however, may be futile because there are an estimated 100 synthetic cannabinoids that have yet to enter the market, and when one is banned, a new one is likely to be introduced immediately as a replacement.8

SYNTHETIC STIMULANTS MARKETED AS BATH SALTS

Like the herbal incense products, “bath salts” may likewise not be what they appear to be. They too may be labeled “not for human consumption” in an effort to bypass laws governing mind-altering substances.

Several pharmacologically active substances have been marketed as bath salts. Two of the more common ingredients are 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and 4-methylcathinone (mephedrone).

MDPV is a dopamine and norepineph-rine reuptake inhibitor that acts as a powerful stimulant. It has no FDA-approved medical use, but it is an analogue of the stimulant pyrovalerone, which was once used to treat chronic fatigue.17

MDPV seems to be the most common substance found in bath salt products in the United States. A sample of this substance was first seized on the streets by German authorities in 2007. A study in Finland conducted from August 2009 to September 2010 estimated that 5.7% of all arrests for driving under the influence (DUI) unrelated to alcohol consumption involved MDPV intoxication.17 In 2009, the National Forensic Laboratory Information System of the US DEA had seized only two samples of MDPV, but by 2010 that had increased to 161.18

Mephedrone is derived from phenethylamine and is closely related to cathinone, the active ingredient in the African khat plant (Catha edulis).19 Khat has a history of abuse, and the chemical structure of cathinone and its derivatives is similar to that of amphetamine.

Mephedrone, a powerful stimulant, is suspected of working as a monoamine reuptake inhibitor, and it may also directly induce the presynaptic release of monoamines.20 The net effect is an increase in serotonin, norepineph-rine, and dopamine levels at neuronal synapses.

Mephedrone was first described in 1929 by chemist Saem de Burnaga Sanchez, and it remained an obscure research chemical for many years.21 It was formally recognized as a drug of abuse in Europe in 2007, and by 2009 it was the sixth most frequently used such drug in Europe.8,22

Although MDPV and mephedrone are the most common psychoactive ingredients in bath salts, many other synthetic drugs have been found on the market.

A temporary ban

On September 7, 2011, the US government made it illegal to possess or sell any substance containing MDPV, mephedrone, or methy-lone. This temporary restriction was to remain in effect for 1 year to give the DEA time to collect data to support a move to permanently control these substances.3

Like synthetic cannabinoids, however, synthetic stimulants are very difficult to regulate because they are a large group of substances. As soon as one substance is outlawed, another synthetic stimulant will likely take its place.

MEDICAL CONCERNS REGARDING SYNTHETIC STIMULANTS

The medical and psychiatric sequelae that are associated with the use of bath salts have sent an increasing number of people to emergency rooms. The number of bath-salt-related calls to US poison control centers increased dramatically from 303 in 2010 to 4,720 by August 31, 2011. Most of these calls were related to tachycardia, agitation, hallucinations, extreme paranoia, delusions, and elevations in blood pressure.3

A report of 35 cases of people who had used bath salts and who had reported to Michigan emergency rooms between November 13, 2010, and March 31, 2011, indicated that agitation was present in 66%, tachycardia in 63%, delusions and hallucinations in 40%, seizure or tremor in 29%, hypertension in 23%, drowsiness in 23%, paranoia in 20%, and mydriasis in 20%; one patient was dead on arrival. Of the 34 patients who were alive on arrival, 17 (50%) were hospitalized, 15 were released, and 2 left against medical advice. In the patients in this study, 63% had injected the drug, 26% snorted it, and 11% ingested it orally.2 Toxicology results obtained during an autopsy on the one person who died revealed a high level of MDPV, and the coroner ruled that MDPV toxicity was the primary cause of death.2

Though the pharmacokinetic properties of mephedrone are unknown, James et al24 noted that an interesting feature is that its clinical effects seem to persist for more than 24 hours after the last exposure to the drug, which would not be expected based on the rapid elimination of other similar cathinones.

Sympathomimetic toxicity. Many of the symptoms listed in Table 2 are consistent with a sympathomimetic syndrome. In a case series reported by Regan et al,26 most of the 57 patients exhibited cardiovascular findings consistent with sympathomimetic toxicity.

In the study by James et al,24 one of the patients with chest pain had electrocardiographic changes consistent with acute myocardial infarction. Though it is not possible to conclude from a single case that mephedrone poses a risk of myocardial infarction, such a risk has been reported with khat.28 More research is needed to determine whether mephedrone poses a risk of cardiac events when used by people with or without an underlying cardiac condition.

Seizure also seems to be a relatively common feature associated with mephedrone use in case series of emergency room presentations. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention l2 reported that of 35 patients who had used bath salts, 40% experienced seizures or “tremors.” A recent case series27 of 15 patients presenting to an emergency department after mephedrone use reported that 20% had experienced seizures. In the study by James et al,24 four patients (3% of the total group) experienced seizures after using mephedrone. It should be noted that, aside from people presenting to emergency rooms, seizures are rarely reported in the wider population of mephedrone users.

Psychotic symptoms are also quite common in users of synthetic stimulants who present to emergency rooms, occurring, as previously stated, in 14% to 40% of cases.2,24

In a small case series, Penders and Gestring29 pointed out some common features in three patients who had used MDPV and had presented with psychosis: sleep problems, inattention, vivid hallucinations of intruders, fearfulness, and inability to remember many of the events surrounding their drug use. The authors concluded that the psychotic syndrome present in their three patients was indicative of a short-term delirium rather than a substance-induced psychosis based on the presence of attention deficits and memory problems. The patients in this series responded well to brief hospitalization and antipsychotic medications.

As with seizure, extreme presentations such as psychosis are infrequently mentioned except in people requiring treatment at a hospital. There are simply no data regarding the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in the larger group of all synthetic stimulant users.

SUSPECT SLID INTOXICATION IN ‘PSYCHIATRIC’ PATIENTS

Despite the temporary ban on the more common substances found in Spice and bath salts, it is premature for the medical community to breath a sigh of relief. Producers of these products are already likely bringing to market new ones containing similar but as yet nonbanned substances. Furthermore, such bans will do little to affect Internet commerce; rather than go to a head shop, consumers will order the products online.

Doctors in urgent care centers, emergency rooms, and on general medical floors should pay close attention to any patient without a known psychiatric history who is acting in a bizarre fashion. Most SLID-intoxicated patients will present with anxiety, agitation, and psychosis. Rather than assume that they are psychiatric patients, one should consider the possibility of SLID intoxication and pay close attention to the possible medical sequelae associated with SLID use, such as elevated blood pressure, tachycardia, and seizure.

Benzodiazepines, especially lorazepam (Ativan), have been the agents most commonly used to treat both agitation and seizures associated with SLID intoxication.

Antipsychotics should be used judiciously because of their propensity to lower the seizure threshold, and patients with synthetic stimulant toxicity are already at increased risk of seizure.

A psychiatric consult should be considered in the event of any suspected toxicity or for any patient whose behavior is difficult to manage.

Restraints may be needed in some circumstances when agitation cannot be controlled with benzodiazepines alone, to ensure safety for the patient as well as that of others in the emergency department.

Routine laboratory tests should be part of the workup of patients suspected of being under the influence of SLIDs. These include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and urine toxicology (Table 3).23,25 A routine urine toxicology study will likely be negative, but either the patient or collateral information may give you a general idea of what the patient used, in which case the sample could be sent out for special tests for the more common substances found in herbal incense or bath salt products.

Electroencephalography may be indicated if there is any question as to whether the patient may have suffered a seizure. There should be a low threshold to order electrocardiography, especially in the case of synthetic stimulant intoxication.

Serial cardiac enzymes may be warranted if a patient with synthetic-stimulant intoxicated has chest pain.

Education, addiction treatment. Much is unknown about the risk of SLIDs, but given the adverse events reported in the literature, it seems likely that those with underlying cardiac or psychiatric issues may be at higher risk for the most serious drug-related consequences. With regard to synthetic stimulants, Winstock et al20 recommend a harm-reduction approach involving educating patients about avoiding the development of tolerance, not engaging in polydrug use, not injecting, and paying special attention to remaining cool and well hydrated.

Experience shows that once SLID patients get through their acute crisis and are no longer psychotic, they tend to be forthright in divulging what they used to get high. At that point, consideration should be given to consulting an addiction treatment specialist for further evaluation of the patient’s drug use history and for formulation of a treatment plan to help ensure that the patient doesn’t return to using these drugs.

SLIDs POSE A REAL CHALLENGE

SLIDs present a real challenge to law enforcement, governments, the public, and the addiction treatment community. There is currently no way to routinely test for these substances. Furthermore, any tests that are developed or laws that are enacted will be easily evaded, as there are many more synthetic substances waiting in the wings to be released.

Don’t be lulled into thinking that SLIDs are gone with the recent bans against some of the more common substances. More SLIDs are coming, and more morbidity should be expected in medical settings.

Doctors in emergency departments and other settings need to be prepared for the agitated and often psychotic presentation of SLID-intoxicated patients and should be ready with benzodiazepines, restraints, and a calm and reassuring manner. And for patients who present with psychotic symptoms, medical staff should also be ready to consider involuntary short-term commitment to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Once they recover, patients need to be educated about the dangers of substances such as SLIDs that, because of their novelty, may be perceived as less dangerous alternatives to traditional illicit drugs.

Over the past year, it has been hard to avoid news reports involving people getting high on “bath salts” and “incense” (also known as “Spice” or “K2”). Addiction treatment professionals have been overwhelmed by questions regarding why one would want to “snort bath salts” or “smoke incense.”

These substances are not what they appear to be. They are sold as bath salts and incense and are labeled “not for human consumption” simply to avoid regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In reality, they are powerful psychoactive drugs, with effects that mimic those of more commonly abused drugs such as amphetamines and marijuana. Until recently, they were legally available over the counter at quick-marts, head shops, and on the Internet. Because they are relatively new, they may not be detectable on routine urine drug screens, and users may be unaware of the specific chemicals contained in them.

These drugs, which we have collectively termed synthetic legal intoxicating drugs (SLIDs), are increasing dramatically in use.1–3 A survey of youths at a rave party indicated that 21% had used one of them on at least one occasion.4 The general impression held by the drug-using public is that SLIDs are relatively cheap, are not detected on standard urine drug screens, can produce a powerful high, and, until recently, were readily available through legitimate sources.

Physicians need to be aware of SLIDs in order to recognize and manage the intoxication syndromes associated with these substances when encountered in clinical practice, and in order to educate patients about their potential dangers.

SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS MARKETED AS INCENSE

Herbal incense products that could be smoked as an alternative to marijuana started appearing on the Internet in Europe in 2004. By 2008, when such products first appeared in the United States, their use in Europe was already widespread.

Initially, consumers were led to believe that such herbal smoking blends were safe, legal alternatives to marijuana, and that it was the proprietary blend of herbs that was responsible for the “natural” high. Spice, a specific brand name, was originally trademarked in England as incense and also as an herbal smoking product.5

Legal authorities, however, suspected that these herbal blends were adulterated with synthetic substances. In December 2008, the first such substance was found when Austrian authorities isolated a synthetic cannabinoid, JWH-018, from an herbal incense product.6 By the end of 2009, five other synthetic cannabinoids—CP-47,497, HU-210, JWH-073, JWH-250, and JWH-398—had been isolated from various herbal incense samples around the world.7

The synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products are not derived from the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa), but are synthesized in laboratories and are formulated to interact with the endogenous cannabinoid receptors in the brain to produce psychoactive effects.

Synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists; natural THC is only a partial agonist

Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been discovered in humans: CB1 and CB2. Both types are found in the central nervous system, and CB2 is also found extensively in the periphery. CB1 is the receptor responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabinoids, including altered consciousness, euphoria, relaxation, perceptual disturbances, intensified sensory experiences, cognitive impairment, and increased reaction time.6 The physiologic role of CB2 remains uncertain.

The major psychoactive cannabinoid in naturally occurring marijuana is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The so-called classic cannabinoids, such as HU-210, are analogues of THC and are based on its chemical structure. The rest of the synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products differ in chemical structure from naturally occurring cannabinoids such as THC, but have activity at the CB1 receptor and are thus psychoactive.

Of clinical relevance is that THC is only a partial agonist at the CB1 receptor, while all synthetic cannabinoids commonly found in incense products are full agonists at CB1.7 This difference is important because partial agonists bind to receptors but stimulate them only partially and therefore exhibit a plateau effect in terms of dose vs clinical response. In contrast, full agonists have no ceiling on the dose-response relationship and therefore have a greater potential for overdose and severe toxic effects.

Despite uncertainties, use is widespread

Most of the synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products were developed for research purposes, and there are almost no reliable scientific data on their effects in humans. Of additional concern is that no research has been conducted on their pyrolytic effects, ie, how these chemicals are transformed when they are burned, such as when consumers smoke them. Furthermore, herbal incense products often vary in their active substances and concentrations, so consumers really do not know what they are getting.

Despite the many uncertainties, the use of these products is widespread. Data submitted to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from a major toxicology laboratory indicated that from July through November of 2010, 3,700 samples tested positive for either JWH-018 or JWH-073. This report also indicated that 30% to 35% of specimens submitted by juvenile probation departments were positive for synthetic cannabinoids.8

MEDICAL CONCERNS OVER SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS