User login

GET INVOLVED!

- Administrators in Hospital Medicine

- Canadian Hospitalists

- Comanagement/Consultative Hospital Medicine

- Community-Based Hospitalists

- Early-Career Hospitalists

- Education/Curriculum

- Family Practice Hospitalists

- Geriatric Hospitalists

- Information Technology

- International Hospital Medicine

- Medical Directors/Leadership

- Med-Peds Hospitalists

- Nonphysician Providers

- Pediatric Hospitalists

- Quality Improvement

- Researchers/Academic Hospitalists

- Rural Hospitalists

- VA Hospitalists

- Women in Hospital Medicine

- Administrators in Hospital Medicine

- Canadian Hospitalists

- Comanagement/Consultative Hospital Medicine

- Community-Based Hospitalists

- Early-Career Hospitalists

- Education/Curriculum

- Family Practice Hospitalists

- Geriatric Hospitalists

- Information Technology

- International Hospital Medicine

- Medical Directors/Leadership

- Med-Peds Hospitalists

- Nonphysician Providers

- Pediatric Hospitalists

- Quality Improvement

- Researchers/Academic Hospitalists

- Rural Hospitalists

- VA Hospitalists

- Women in Hospital Medicine

- Administrators in Hospital Medicine

- Canadian Hospitalists

- Comanagement/Consultative Hospital Medicine

- Community-Based Hospitalists

- Early-Career Hospitalists

- Education/Curriculum

- Family Practice Hospitalists

- Geriatric Hospitalists

- Information Technology

- International Hospital Medicine

- Medical Directors/Leadership

- Med-Peds Hospitalists

- Nonphysician Providers

- Pediatric Hospitalists

- Quality Improvement

- Researchers/Academic Hospitalists

- Rural Hospitalists

- VA Hospitalists

- Women in Hospital Medicine

MEET AND GREET, TEXAS-STYLE

Ask any veteran of an SHM annual meeting, and they’ll tell you that they come for the people.

The unprecedented growth of HM as a specialty means that more hospitalists have chances to connect throughout the year. But the specialty’s relative youth and the demand for hospitalists make networking with peers a key part of the annual meeting experience.

In response to conference attendees, HM11 will have even more networking opportunities built into the schedule than before. Additional time for lunches and breaks are built into the schedule, and the always-popular Special Interest Forums have been moved to the evening of the first day of the regular meeting, May 11.

The forums are specially designed to bring hospitalists with common interests together to informally share their experiences. “Many hospitalists across the country are tackling similar challenges,” says Geri Barnes, senior director of education and meetings at SHM. “The Special Interest Forums are an opportunity to build community around those challenges and the best practices they’ve developed.”

For hospitalists looking for face time with SHM leadership, the SHM Town Hall (2 p.m., May 13) offers a once-a-year preview into the society’s vision and the chance to ask the nation’s HM leaders about the specialty and its impact on hospitalists.—BS

Ask any veteran of an SHM annual meeting, and they’ll tell you that they come for the people.

The unprecedented growth of HM as a specialty means that more hospitalists have chances to connect throughout the year. But the specialty’s relative youth and the demand for hospitalists make networking with peers a key part of the annual meeting experience.

In response to conference attendees, HM11 will have even more networking opportunities built into the schedule than before. Additional time for lunches and breaks are built into the schedule, and the always-popular Special Interest Forums have been moved to the evening of the first day of the regular meeting, May 11.

The forums are specially designed to bring hospitalists with common interests together to informally share their experiences. “Many hospitalists across the country are tackling similar challenges,” says Geri Barnes, senior director of education and meetings at SHM. “The Special Interest Forums are an opportunity to build community around those challenges and the best practices they’ve developed.”

For hospitalists looking for face time with SHM leadership, the SHM Town Hall (2 p.m., May 13) offers a once-a-year preview into the society’s vision and the chance to ask the nation’s HM leaders about the specialty and its impact on hospitalists.—BS

Ask any veteran of an SHM annual meeting, and they’ll tell you that they come for the people.

The unprecedented growth of HM as a specialty means that more hospitalists have chances to connect throughout the year. But the specialty’s relative youth and the demand for hospitalists make networking with peers a key part of the annual meeting experience.

In response to conference attendees, HM11 will have even more networking opportunities built into the schedule than before. Additional time for lunches and breaks are built into the schedule, and the always-popular Special Interest Forums have been moved to the evening of the first day of the regular meeting, May 11.

The forums are specially designed to bring hospitalists with common interests together to informally share their experiences. “Many hospitalists across the country are tackling similar challenges,” says Geri Barnes, senior director of education and meetings at SHM. “The Special Interest Forums are an opportunity to build community around those challenges and the best practices they’ve developed.”

For hospitalists looking for face time with SHM leadership, the SHM Town Hall (2 p.m., May 13) offers a once-a-year preview into the society’s vision and the chance to ask the nation’s HM leaders about the specialty and its impact on hospitalists.—BS

POLICY CORNER: An inside look at the most pressing policy issues

On Feb. 16, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) listed SHM as a patient safety organization (PSO). A PSO serves as an independent, external, expert organization that can collect, analyze, and aggregate information in order to develop insights into the underlying causes of patient-safety events. PSOs are designed to help clinicians, hospitals, and healthcare organizations improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

PSO status allows SHM’s current quality-improvement (QI) activities to be conducted in a secure environment that is protected from legal discovery. AHRQ currently lists 78 PSOs, including the Society for Vascular Surgery PSO, the Emergency Medicine Patient Safety Foundation, and the Biomedical Research and Education Foundation. A full list is available at www.pso.ahrq.gov/listing/psolist.htm.

To achieve PSO status, SHM worked closely with AHRQ to meet specific guidelines and requirements. One of the requirements is that the mission and primary activity of a PSO must be to conduct activities that are designed to improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

To comply, SHM formed a separate component within the Quality Initiatives Department strictly to pursue patient safety and quality activities.

The SHM PSO will be unique. While PSOs are required to collect patient-safety data and provide some form of feedback to contracted sites, few have their own QI initiatives, and even fewer are established by a national physician’s professional society.

These differences will help the SHM PSO stand out from the crowd and will present opportunities within the healthcare reform framework. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires significant QI among the nation’s hospitals.

Specifically pertaining to PSOs, Section 399KK, a rarely mentioned section of the ACA, requires the Health and Human Services to establish a program for hospitals with high readmission rates to improve their rates through the use of PSOs. The details of this program remain unclear, but based upon the little bit of information currently available, there could be positive overlap between SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) and the provision.

AHRQ’s recognition of the SHM PSO exemplifies SHM’s commitment to improving the quality of healthcare delivery. It also provides additional value to sites that implement SHM’s QI initiatives and will hopefully open new doors to SHM’s members. TH

On Feb. 16, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) listed SHM as a patient safety organization (PSO). A PSO serves as an independent, external, expert organization that can collect, analyze, and aggregate information in order to develop insights into the underlying causes of patient-safety events. PSOs are designed to help clinicians, hospitals, and healthcare organizations improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

PSO status allows SHM’s current quality-improvement (QI) activities to be conducted in a secure environment that is protected from legal discovery. AHRQ currently lists 78 PSOs, including the Society for Vascular Surgery PSO, the Emergency Medicine Patient Safety Foundation, and the Biomedical Research and Education Foundation. A full list is available at www.pso.ahrq.gov/listing/psolist.htm.

To achieve PSO status, SHM worked closely with AHRQ to meet specific guidelines and requirements. One of the requirements is that the mission and primary activity of a PSO must be to conduct activities that are designed to improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

To comply, SHM formed a separate component within the Quality Initiatives Department strictly to pursue patient safety and quality activities.

The SHM PSO will be unique. While PSOs are required to collect patient-safety data and provide some form of feedback to contracted sites, few have their own QI initiatives, and even fewer are established by a national physician’s professional society.

These differences will help the SHM PSO stand out from the crowd and will present opportunities within the healthcare reform framework. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires significant QI among the nation’s hospitals.

Specifically pertaining to PSOs, Section 399KK, a rarely mentioned section of the ACA, requires the Health and Human Services to establish a program for hospitals with high readmission rates to improve their rates through the use of PSOs. The details of this program remain unclear, but based upon the little bit of information currently available, there could be positive overlap between SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) and the provision.

AHRQ’s recognition of the SHM PSO exemplifies SHM’s commitment to improving the quality of healthcare delivery. It also provides additional value to sites that implement SHM’s QI initiatives and will hopefully open new doors to SHM’s members. TH

On Feb. 16, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) listed SHM as a patient safety organization (PSO). A PSO serves as an independent, external, expert organization that can collect, analyze, and aggregate information in order to develop insights into the underlying causes of patient-safety events. PSOs are designed to help clinicians, hospitals, and healthcare organizations improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

PSO status allows SHM’s current quality-improvement (QI) activities to be conducted in a secure environment that is protected from legal discovery. AHRQ currently lists 78 PSOs, including the Society for Vascular Surgery PSO, the Emergency Medicine Patient Safety Foundation, and the Biomedical Research and Education Foundation. A full list is available at www.pso.ahrq.gov/listing/psolist.htm.

To achieve PSO status, SHM worked closely with AHRQ to meet specific guidelines and requirements. One of the requirements is that the mission and primary activity of a PSO must be to conduct activities that are designed to improve patient safety and the quality of healthcare delivery.

To comply, SHM formed a separate component within the Quality Initiatives Department strictly to pursue patient safety and quality activities.

The SHM PSO will be unique. While PSOs are required to collect patient-safety data and provide some form of feedback to contracted sites, few have their own QI initiatives, and even fewer are established by a national physician’s professional society.

These differences will help the SHM PSO stand out from the crowd and will present opportunities within the healthcare reform framework. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires significant QI among the nation’s hospitals.

Specifically pertaining to PSOs, Section 399KK, a rarely mentioned section of the ACA, requires the Health and Human Services to establish a program for hospitals with high readmission rates to improve their rates through the use of PSOs. The details of this program remain unclear, but based upon the little bit of information currently available, there could be positive overlap between SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) and the provision.

AHRQ’s recognition of the SHM PSO exemplifies SHM’s commitment to improving the quality of healthcare delivery. It also provides additional value to sites that implement SHM’s QI initiatives and will hopefully open new doors to SHM’s members. TH

HM11 BLOGS & BLOGGERS: Hear it through the Grapevine

For hospitalists planning on attending HM11, and those who can’t make it to Dallas in May, SHM’s blogs are a vital connection to the most up-to-date information about the biggest annual event in HM. And many of the specialty’s top bloggers will be speaking or presenting at HM11.

SHM bloggers will keep readers updated before the big event, highlighting can’t-miss issues, sessions, and experts who they’re anxious to see. Plus, they’ll apply the issues of the day to HM11 sessions and pre-courses.

One of HM’s most popular bloggers not only will be blogging about HM11, he’ll be a featured presenter. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine UCSF Medical Center, and author of the blog Wachter’s World, will deliver the May 13 keynote presentation, “Hospital Medicine at 15: The Things I Never Would Have Guessed When the Fun Began.”

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, author of the SHM blog Hospital Medicine Quick Hits: Clinical Updates for the Busy Hospitalist and SHM physician advisor, will be teaching the “ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Learning Session” pre-course May 10. Dr. Scheurer will work with hospitalists to prepare for the ABIM modules and earn up to 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program.

In between teaching and learning, she also will be blogging about HM11. “I do it as a way to include those members that are not able attend,” Dr. Scheurer says, “or those who can’t stay for the whole meeting, as well as people who are at the meeting but who like guidance and synopses.”

With nine tracks and hundreds of educational and networking opportunities, odds are good that her online guidance will be in high demand.—BS

For hospitalists planning on attending HM11, and those who can’t make it to Dallas in May, SHM’s blogs are a vital connection to the most up-to-date information about the biggest annual event in HM. And many of the specialty’s top bloggers will be speaking or presenting at HM11.

SHM bloggers will keep readers updated before the big event, highlighting can’t-miss issues, sessions, and experts who they’re anxious to see. Plus, they’ll apply the issues of the day to HM11 sessions and pre-courses.

One of HM’s most popular bloggers not only will be blogging about HM11, he’ll be a featured presenter. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine UCSF Medical Center, and author of the blog Wachter’s World, will deliver the May 13 keynote presentation, “Hospital Medicine at 15: The Things I Never Would Have Guessed When the Fun Began.”

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, author of the SHM blog Hospital Medicine Quick Hits: Clinical Updates for the Busy Hospitalist and SHM physician advisor, will be teaching the “ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Learning Session” pre-course May 10. Dr. Scheurer will work with hospitalists to prepare for the ABIM modules and earn up to 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program.

In between teaching and learning, she also will be blogging about HM11. “I do it as a way to include those members that are not able attend,” Dr. Scheurer says, “or those who can’t stay for the whole meeting, as well as people who are at the meeting but who like guidance and synopses.”

With nine tracks and hundreds of educational and networking opportunities, odds are good that her online guidance will be in high demand.—BS

For hospitalists planning on attending HM11, and those who can’t make it to Dallas in May, SHM’s blogs are a vital connection to the most up-to-date information about the biggest annual event in HM. And many of the specialty’s top bloggers will be speaking or presenting at HM11.

SHM bloggers will keep readers updated before the big event, highlighting can’t-miss issues, sessions, and experts who they’re anxious to see. Plus, they’ll apply the issues of the day to HM11 sessions and pre-courses.

One of HM’s most popular bloggers not only will be blogging about HM11, he’ll be a featured presenter. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine UCSF Medical Center, and author of the blog Wachter’s World, will deliver the May 13 keynote presentation, “Hospital Medicine at 15: The Things I Never Would Have Guessed When the Fun Began.”

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, author of the SHM blog Hospital Medicine Quick Hits: Clinical Updates for the Busy Hospitalist and SHM physician advisor, will be teaching the “ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Learning Session” pre-course May 10. Dr. Scheurer will work with hospitalists to prepare for the ABIM modules and earn up to 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program.

In between teaching and learning, she also will be blogging about HM11. “I do it as a way to include those members that are not able attend,” Dr. Scheurer says, “or those who can’t stay for the whole meeting, as well as people who are at the meeting but who like guidance and synopses.”

With nine tracks and hundreds of educational and networking opportunities, odds are good that her online guidance will be in high demand.—BS

In the Literature: HM-Related Research You Need to Know

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk of adverse events with opioid use

- Drug of choice for outpatient treatment of cellulitis

- Preventing hospital falls

- Post-hospital outcomes based on status of PCP follow-up

- LOS, mortality, and readmission based on insurance

- Antiplatelets added to warfarin for atrial fibrillation.

- Cognitive effects of severe sepsis

- Effect of preoperative furosemide use

ED Visits Are Higher among Recipients of Chronic Opioid Therapy

Clinical question: Is there an association between the use of prescription opioids and adverse outcomes?

Background: Chronic opioid therapy is a common strategy for managing chronic, noncancer pain. There has been an increase in overdose deaths and ED visits (EDV) involving the use of prescription opioids.

Study design: Retrospective study from claims records.

Setting: Population in the Health Core Integrated Research Database, containing large, commercial insurance plans in 14 states, and Arkansas Medicaid.

Synopsis: Patients 18 and older without cancer diagnoses who used prescription opioids for at least 90 continuous days within a six-month period from 2000 to 2005 were examined for risk factors for EDVs and alcohol- or drug-related encounters (ADEs) in the 12 months following 90 days or more of prescribed opioids.

Patients with diagnoses of headache, back pain, and pre-existing substance-use disorders had significantly higher EDVs and ADEs. Opioid dose at morphine-equivalent doses over 120 mg per day doubled the risk of ADEs. The use of short-acting Schedule II opioids was associated with EDVs (relative risk, 1.09-1.74). The use of long-acting Schedule II opioids was strongly associated with ADEs (relative risk, 1.64-4.00).

Bottom line: In adults with noncancer pain prescribed opioids for 90 days or more, short-acting Schedule II opioid use was associated with an increased number of EDVs, and long-acting opioid use was associated with an increased number of ADEs. Minimizing Schedule II opioid prescription in these higher-risk patients might be prudent to increase patient safety.

Citation: Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MI, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170(16):1425-1432.

Empiric Outpatient Therapy with Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole or Clindamycin Is Preferred for Cellulitis

Clinical question: What is the best empiric outpatient oral antibiotic treatment for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-associated MRSA infections?

Background: The increasing rates of community-associated MRSA skin and soft-tissue infections have raised concerns that such beta-lactams as cephalexin and other semisynthetic penicillins are not appropriate for empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis.

Study design: Three-year, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A teaching clinic of a tertiary-care medical center in Hawaii.

Synopsis: More than 540 patients with cellulitis were identified from January 2005 to December 2007. Of these, 139 patients were excluded for reasons such as hospitalization, surgical intervention, etc. In the final cohort of 405 patients, the three most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics were cephalexin (44%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (38%), and clindamycin (10%). Other antibiotics accounted for the remaining 8%.

MRSA was recovered in 62% of positive culture specimens. The success rate of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was 91% vs. 74% in the cephalexin group (P<0.001). Clindamycin success rates were higher than those of cephalexin in patients who had subsequently confirmed MRSA infections (P=0.01) and moderately severe cellulitis (P=0.03) and were obese (P=0.04).

Bottom line: Antibiotics with activity against community-acquired MRSA (e.g. trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole and clinidamycin) are the preferred empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA.

Citation: Khawcharoenporn T, Tice A. Empiric outpatient therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, or clindamycin for cellulitis. Am J Med. 2010;123(10):942-950.

Patient-Specific Screening with Health Information Technology Prevents Falls

Clinical question: Does a fall-prevention toolkit using health information technology decrease patient falls in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inpatient falls and fall-related injuries result in substantial morbidity and additional healthcare costs. While specific fall-prevention strategies were a longstanding target for intervention, little evidence exists to link them with decreased fall rates.

Study design: Cluster-randomized study.

Setting: Four urban hospitals in Massachusetts.

Synopsis: Comparing patient fall rates in four acute-care hospitals between units providing usual care (5,104 patients) and units using a health information technology (HIT)-linked fall prevention toolkit (5,160 patients), this study demonstrated significant fall reduction in older inpatients. The intervention integrated existing workflow and validated fall risk assessment (Morse Falls Scale) into an HIT software application that tailored fall-prevention interventions to patients’ specific fall risk determinants. The toolkit produced bed posters, patient education handouts, and plans of care communicating patient-specific alerts to key stakeholders.

The primary outcome was patient falls per 1,000 patient-days during the six-month intervention period. The number of patients with falls was significantly different (P=0.02) between control (n=87) and intervention (n=67) units. The toolkit prevented one fall per 862 patient-days.

This nonblinded study was limited by the fact that it was conducted in a single health system. The toolkit was not effective in patients less than 65 years of age. Additionally, the sample size did not have sufficient power to detect effectiveness in preventing repeat falls or falls with injury.

Bottom line: Patient-specific fall prevention strategy coupled with HIT reduces falls in older inpatients.

Citation: Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1912-1918.

Lack of Timely Outpatient Follow-Up Results in Higher Readmission Rates

Clinical question: Does timely primary-care-physician (PCP) follow-up improve outcomes and prevent hospital readmissions?

Background: Active PCP involvement is key to interventions aimed at reducing readmissions and ensuring effective ongoing patient care. Some studies suggest increased overall resource utilization when PCP follow-up occurs after hospitalization. Resource utilization and clinical outcomes after hospitalization related to timely PCP follow-up have not been adequately studied.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: An urban, academic, 425-bed tertiary-care center in Colorado.

Synopsis: From a convenience sample of 121 patients admitted to general medicine services during winter months, 65 patients completed the study. Demographics, diagnosis, payor source, and PCP information were collected upon enrollment. Post-discharge phone calls and patient surveys were used to determine follow-up and readmission status. Timely PCP follow-up was defined as a visit with a PCP or specialist related to the discharge diagnosis within four weeks of hospital discharge.

Thirty-day readmission rates and hospital length of stay were compared for those with timely PCP follow-up and those without. Less than half of general-medicine inpatients received timely PCP follow-up post-discharge. Lack of timely PCP follow-up was associated with younger age, a 10-fold increase in 30-day readmission for the same condition, and a trend toward longer length of stay. However, hospital readmission for any condition did not differ with lack of timely PCP follow-up.

This small, single-center study with convenience sample enrollment might not represent all medical inpatients or diagnoses. Determination of same-condition readmission was potentially subjective.

Bottom line: Patients who lack timely post-discharge follow-up have higher readmission rates for the same medical condition.

Citation: Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

Compared with Uninsured and Medicaid Patients, Privately Insured Patients Admitted for Acute MI, Stroke, and Pneumonia Have Better Mortality Rates

Clinical question: Do outcomes for insured and underinsured patients vary for three of the most common medical conditions for which patients are hospitalized: acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke, and pneumonia?

Background: The ideal healthcare system would provide quality care to all individuals regardless of insurance status. Nevertheless, disparities in outcomes for the insured and underinsured or uninsured are well-documented in the outpatient setting but not as well in the inpatient setting. More needs to be done to address these potential disparities.

Study design: Retrospective database analysis.

Setting: Database including 20% of all U.S. community hospitals, including public hospitals, academic medical centers, and specialty hospitals.

Synopsis: This study utilized a database of 8 million discharges from more than 1,000 hospitals and isolated patients 18-64 years old (154,381 patients). Privately insured, uninsured, and Medicaid patients’ data were reviewed for in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost per hospitalization. The analysis took into account disease severity, comorbidities, and the proportion of underinsured patients receiving care in each hospital when insurance-related disparities were examined.

Compared with the privately insured, in-hospital mortality and LOS for AMI and stroke were significantly higher for uninsured and Medicaid patients. Among pneumonia patients, Medicaid patients had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and LOS than the other two groups. Cost per hospitalization was highest for all three conditions in the Medicaid group; the uninsured group had the lowest costs for all three conditions.

Unfortunately, the three conditions analyzed only comprise 8% of annual hospital discharges, so the findings cannot be generalized. Also, deaths occurring soon after hospital discharge were not included, and uninsured and Medicaid patients are likely to have more severe diseases, which, rather than insurance status, could account for the mortality differences.

Bottom line: In-hospital mortality and resource use for three common medical conditions vary significantly between privately insured and uninsured or Medicaid patients, highlighting the need to take measures to close this gap.

Citation: Hasan O, Orav EJ, LeRoi LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8);452-459.

Warfarin Monotherapy Best in Prevention of Thromboembolic Events for Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to adding an antiplatelet agent to warfarin for the prevention of thromboembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation?

Background: Many physicians prescribe various combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin, as these treatments are endorsed in guidelines and expert statements. The use of these medications, however, has not been studied in a setting large enough to understand the safety of these therapies.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: All Danish hospitals.

Synopsis: All hospitalized patients in Denmark from 1997 to 2006 who were identified with new onset atrial fibrillation (n=118,606) were monitored for outcomes and the use of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin. These patients were followed for a mean of 3.3 years with the primary endpoint being admission to a hospital for a diagnosis of bleeding and a secondary endpoint of stroke.

Bleeding occurred in 13,573 patients (11.4%). The incidence of bleeding was highest in the first 180 days and then leveled off. Hazard ratios were computed with warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Only the hazard ratio for aspirin monotherapy (0.93) was lower (confidence interval [CI] 0.88-0.98). The highest risk of bleeding was with the triple therapy warfarin-aspirin-clopidogrel, which had a hazard ratio of 3.70 (CI 2.89-4.76).

For strokes, the hazard ratio was slightly better for warfarin-clopidogrel (0.70), although the CI was wide at 0.35-1.4 compared to warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Hazard ratios for monotherapy with clopidogrel or aspirin, dual therapy, and triple therapy all were worse, ranging from 1.27 to 1.86.

Bottom line: Warfarin as a monotherapy might have a bleeding risk comparable to that of aspirin or clopidogrel alone, and prevents more strokes than various combinations of these medications.

Citation: Hansen ML, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170 (16):1433-1441.

Cognitive and Physical Function Declines in Elderly Severe Sepsis Survivors

Clinical question: Is there a change in cognitive and physical functioning after severe sepsis?

Background: Disability is associated with increased mortality, decreased quality of life, and increased burdens by families and healthcare costs. After severe sepsis, the lasting effects of debility have not been investigated in any large studies.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitalized Medicare patients participating in the Health and Retirement Study.

Synopsis: Patients (n=1194) were followed for a minimum of one year between 1998 and 2006. The outcomes were measured by multiple personal interviews before and after a severe sepsis episode. Cognitive impairment was measured using three validated questionnaires dependent upon age or if a proxy was the respondent. For functional limitations, a questionnaire concerning instrumental and basic activities of daily living was used.

Cognitive impairment for those with moderate to severe impairment increased to 16.7% from 6.1% after a sepsis episode with an odds ratio of 3.34 (95% confidence interval 1.53-7.25). There was no significant increase in nonsevere sepsis hospitalized comparison patients (n=5574). All survivors with severe sepsis had a functional decline of 1.5 activities. The comparison group had about a 0.4 activity decline. All of these deficits endured throughout the study.

The authors provide comments that there should be a system-based approach in preventing severe sepsis, its burdens, and its costs. Suggestions include preventing delirium, initiating better standards of care, and involving therapists earlier to prevent immobility.

Bottom line: Severe sepsis is independently associated with enduring cognitive and physical functional declines, which strain families and our healthcare system.

Citation: Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787-1794.

Furosemide on Day of Elective Noncardiac Surgery Does Not Increase Risk of Intraoperative Hypotension

Clinical question: For patients chronically treated with loop diuretics, does withholding furosemide on the day of elective noncardiac surgery prevent intraoperative hypotension?

Background: Recent studies have questioned the safety of blood-pressure-lowering medications administered on the day of surgery. Beta-blockers have been associated with an increase in strokes and death perioperatively, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are frequently withheld on the day of surgery to avoid intraoperative hypotension. The effect of loop diuretics is uncertain.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Three North American university centers.

Synopsis: One hundred ninety-three patients were instructed to take furosemide or placebo on the day they underwent noncardiac surgery. The primary outcome measure was perioperative hypotension defined as a SBP <90 mmHg for more than five minutes, a 35% drop in the mean arterial blood pressure, or the need for a vasopressor agent. The number of cardiovascular complications (acute heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, acute cerebrovascular event) and deaths also were analyzed.

Concerns have been raised that loop diuretics might predispose patients to a higher risk of intraoperative hypotension during noncardiac surgery. This trial showed no significant difference in the rates of intraoperative hypotension in patients who were administered furosemide versus those who were not. Although cardiovascular complications occurred more frequently in the furosemide group, the difference was not statistically significant.

Important limitations of the study were recognized. A larger population of patients could have revealed a statistically significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes in the furosemide group. Also, an anesthetic protocol was not utilized, which raises questions about the interaction of furosemide and effect on blood pressure with certain anesthetics.

Bottom line: Administering furosemide prior to surgery in chronic users does not appreciably increase the rate of intraoperative hypotension or cardiovascular events.

Citation: Khan NA, Campbell NR, Frost SD, et al. Risk of intraoperative hypotension with loop diuretics: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):1059e1-1059e8.

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk of adverse events with opioid use

- Drug of choice for outpatient treatment of cellulitis

- Preventing hospital falls

- Post-hospital outcomes based on status of PCP follow-up

- LOS, mortality, and readmission based on insurance

- Antiplatelets added to warfarin for atrial fibrillation.

- Cognitive effects of severe sepsis

- Effect of preoperative furosemide use

ED Visits Are Higher among Recipients of Chronic Opioid Therapy

Clinical question: Is there an association between the use of prescription opioids and adverse outcomes?

Background: Chronic opioid therapy is a common strategy for managing chronic, noncancer pain. There has been an increase in overdose deaths and ED visits (EDV) involving the use of prescription opioids.

Study design: Retrospective study from claims records.

Setting: Population in the Health Core Integrated Research Database, containing large, commercial insurance plans in 14 states, and Arkansas Medicaid.

Synopsis: Patients 18 and older without cancer diagnoses who used prescription opioids for at least 90 continuous days within a six-month period from 2000 to 2005 were examined for risk factors for EDVs and alcohol- or drug-related encounters (ADEs) in the 12 months following 90 days or more of prescribed opioids.

Patients with diagnoses of headache, back pain, and pre-existing substance-use disorders had significantly higher EDVs and ADEs. Opioid dose at morphine-equivalent doses over 120 mg per day doubled the risk of ADEs. The use of short-acting Schedule II opioids was associated with EDVs (relative risk, 1.09-1.74). The use of long-acting Schedule II opioids was strongly associated with ADEs (relative risk, 1.64-4.00).

Bottom line: In adults with noncancer pain prescribed opioids for 90 days or more, short-acting Schedule II opioid use was associated with an increased number of EDVs, and long-acting opioid use was associated with an increased number of ADEs. Minimizing Schedule II opioid prescription in these higher-risk patients might be prudent to increase patient safety.

Citation: Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MI, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170(16):1425-1432.

Empiric Outpatient Therapy with Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole or Clindamycin Is Preferred for Cellulitis

Clinical question: What is the best empiric outpatient oral antibiotic treatment for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-associated MRSA infections?

Background: The increasing rates of community-associated MRSA skin and soft-tissue infections have raised concerns that such beta-lactams as cephalexin and other semisynthetic penicillins are not appropriate for empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis.

Study design: Three-year, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A teaching clinic of a tertiary-care medical center in Hawaii.

Synopsis: More than 540 patients with cellulitis were identified from January 2005 to December 2007. Of these, 139 patients were excluded for reasons such as hospitalization, surgical intervention, etc. In the final cohort of 405 patients, the three most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics were cephalexin (44%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (38%), and clindamycin (10%). Other antibiotics accounted for the remaining 8%.

MRSA was recovered in 62% of positive culture specimens. The success rate of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was 91% vs. 74% in the cephalexin group (P<0.001). Clindamycin success rates were higher than those of cephalexin in patients who had subsequently confirmed MRSA infections (P=0.01) and moderately severe cellulitis (P=0.03) and were obese (P=0.04).

Bottom line: Antibiotics with activity against community-acquired MRSA (e.g. trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole and clinidamycin) are the preferred empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA.

Citation: Khawcharoenporn T, Tice A. Empiric outpatient therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, or clindamycin for cellulitis. Am J Med. 2010;123(10):942-950.

Patient-Specific Screening with Health Information Technology Prevents Falls

Clinical question: Does a fall-prevention toolkit using health information technology decrease patient falls in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inpatient falls and fall-related injuries result in substantial morbidity and additional healthcare costs. While specific fall-prevention strategies were a longstanding target for intervention, little evidence exists to link them with decreased fall rates.

Study design: Cluster-randomized study.

Setting: Four urban hospitals in Massachusetts.

Synopsis: Comparing patient fall rates in four acute-care hospitals between units providing usual care (5,104 patients) and units using a health information technology (HIT)-linked fall prevention toolkit (5,160 patients), this study demonstrated significant fall reduction in older inpatients. The intervention integrated existing workflow and validated fall risk assessment (Morse Falls Scale) into an HIT software application that tailored fall-prevention interventions to patients’ specific fall risk determinants. The toolkit produced bed posters, patient education handouts, and plans of care communicating patient-specific alerts to key stakeholders.

The primary outcome was patient falls per 1,000 patient-days during the six-month intervention period. The number of patients with falls was significantly different (P=0.02) between control (n=87) and intervention (n=67) units. The toolkit prevented one fall per 862 patient-days.

This nonblinded study was limited by the fact that it was conducted in a single health system. The toolkit was not effective in patients less than 65 years of age. Additionally, the sample size did not have sufficient power to detect effectiveness in preventing repeat falls or falls with injury.

Bottom line: Patient-specific fall prevention strategy coupled with HIT reduces falls in older inpatients.

Citation: Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1912-1918.

Lack of Timely Outpatient Follow-Up Results in Higher Readmission Rates

Clinical question: Does timely primary-care-physician (PCP) follow-up improve outcomes and prevent hospital readmissions?

Background: Active PCP involvement is key to interventions aimed at reducing readmissions and ensuring effective ongoing patient care. Some studies suggest increased overall resource utilization when PCP follow-up occurs after hospitalization. Resource utilization and clinical outcomes after hospitalization related to timely PCP follow-up have not been adequately studied.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: An urban, academic, 425-bed tertiary-care center in Colorado.

Synopsis: From a convenience sample of 121 patients admitted to general medicine services during winter months, 65 patients completed the study. Demographics, diagnosis, payor source, and PCP information were collected upon enrollment. Post-discharge phone calls and patient surveys were used to determine follow-up and readmission status. Timely PCP follow-up was defined as a visit with a PCP or specialist related to the discharge diagnosis within four weeks of hospital discharge.

Thirty-day readmission rates and hospital length of stay were compared for those with timely PCP follow-up and those without. Less than half of general-medicine inpatients received timely PCP follow-up post-discharge. Lack of timely PCP follow-up was associated with younger age, a 10-fold increase in 30-day readmission for the same condition, and a trend toward longer length of stay. However, hospital readmission for any condition did not differ with lack of timely PCP follow-up.

This small, single-center study with convenience sample enrollment might not represent all medical inpatients or diagnoses. Determination of same-condition readmission was potentially subjective.

Bottom line: Patients who lack timely post-discharge follow-up have higher readmission rates for the same medical condition.

Citation: Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

Compared with Uninsured and Medicaid Patients, Privately Insured Patients Admitted for Acute MI, Stroke, and Pneumonia Have Better Mortality Rates

Clinical question: Do outcomes for insured and underinsured patients vary for three of the most common medical conditions for which patients are hospitalized: acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke, and pneumonia?

Background: The ideal healthcare system would provide quality care to all individuals regardless of insurance status. Nevertheless, disparities in outcomes for the insured and underinsured or uninsured are well-documented in the outpatient setting but not as well in the inpatient setting. More needs to be done to address these potential disparities.

Study design: Retrospective database analysis.

Setting: Database including 20% of all U.S. community hospitals, including public hospitals, academic medical centers, and specialty hospitals.

Synopsis: This study utilized a database of 8 million discharges from more than 1,000 hospitals and isolated patients 18-64 years old (154,381 patients). Privately insured, uninsured, and Medicaid patients’ data were reviewed for in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost per hospitalization. The analysis took into account disease severity, comorbidities, and the proportion of underinsured patients receiving care in each hospital when insurance-related disparities were examined.

Compared with the privately insured, in-hospital mortality and LOS for AMI and stroke were significantly higher for uninsured and Medicaid patients. Among pneumonia patients, Medicaid patients had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and LOS than the other two groups. Cost per hospitalization was highest for all three conditions in the Medicaid group; the uninsured group had the lowest costs for all three conditions.

Unfortunately, the three conditions analyzed only comprise 8% of annual hospital discharges, so the findings cannot be generalized. Also, deaths occurring soon after hospital discharge were not included, and uninsured and Medicaid patients are likely to have more severe diseases, which, rather than insurance status, could account for the mortality differences.

Bottom line: In-hospital mortality and resource use for three common medical conditions vary significantly between privately insured and uninsured or Medicaid patients, highlighting the need to take measures to close this gap.

Citation: Hasan O, Orav EJ, LeRoi LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8);452-459.

Warfarin Monotherapy Best in Prevention of Thromboembolic Events for Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to adding an antiplatelet agent to warfarin for the prevention of thromboembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation?

Background: Many physicians prescribe various combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin, as these treatments are endorsed in guidelines and expert statements. The use of these medications, however, has not been studied in a setting large enough to understand the safety of these therapies.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: All Danish hospitals.

Synopsis: All hospitalized patients in Denmark from 1997 to 2006 who were identified with new onset atrial fibrillation (n=118,606) were monitored for outcomes and the use of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin. These patients were followed for a mean of 3.3 years with the primary endpoint being admission to a hospital for a diagnosis of bleeding and a secondary endpoint of stroke.

Bleeding occurred in 13,573 patients (11.4%). The incidence of bleeding was highest in the first 180 days and then leveled off. Hazard ratios were computed with warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Only the hazard ratio for aspirin monotherapy (0.93) was lower (confidence interval [CI] 0.88-0.98). The highest risk of bleeding was with the triple therapy warfarin-aspirin-clopidogrel, which had a hazard ratio of 3.70 (CI 2.89-4.76).

For strokes, the hazard ratio was slightly better for warfarin-clopidogrel (0.70), although the CI was wide at 0.35-1.4 compared to warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Hazard ratios for monotherapy with clopidogrel or aspirin, dual therapy, and triple therapy all were worse, ranging from 1.27 to 1.86.

Bottom line: Warfarin as a monotherapy might have a bleeding risk comparable to that of aspirin or clopidogrel alone, and prevents more strokes than various combinations of these medications.

Citation: Hansen ML, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170 (16):1433-1441.

Cognitive and Physical Function Declines in Elderly Severe Sepsis Survivors

Clinical question: Is there a change in cognitive and physical functioning after severe sepsis?

Background: Disability is associated with increased mortality, decreased quality of life, and increased burdens by families and healthcare costs. After severe sepsis, the lasting effects of debility have not been investigated in any large studies.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitalized Medicare patients participating in the Health and Retirement Study.

Synopsis: Patients (n=1194) were followed for a minimum of one year between 1998 and 2006. The outcomes were measured by multiple personal interviews before and after a severe sepsis episode. Cognitive impairment was measured using three validated questionnaires dependent upon age or if a proxy was the respondent. For functional limitations, a questionnaire concerning instrumental and basic activities of daily living was used.

Cognitive impairment for those with moderate to severe impairment increased to 16.7% from 6.1% after a sepsis episode with an odds ratio of 3.34 (95% confidence interval 1.53-7.25). There was no significant increase in nonsevere sepsis hospitalized comparison patients (n=5574). All survivors with severe sepsis had a functional decline of 1.5 activities. The comparison group had about a 0.4 activity decline. All of these deficits endured throughout the study.

The authors provide comments that there should be a system-based approach in preventing severe sepsis, its burdens, and its costs. Suggestions include preventing delirium, initiating better standards of care, and involving therapists earlier to prevent immobility.

Bottom line: Severe sepsis is independently associated with enduring cognitive and physical functional declines, which strain families and our healthcare system.

Citation: Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787-1794.

Furosemide on Day of Elective Noncardiac Surgery Does Not Increase Risk of Intraoperative Hypotension

Clinical question: For patients chronically treated with loop diuretics, does withholding furosemide on the day of elective noncardiac surgery prevent intraoperative hypotension?

Background: Recent studies have questioned the safety of blood-pressure-lowering medications administered on the day of surgery. Beta-blockers have been associated with an increase in strokes and death perioperatively, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are frequently withheld on the day of surgery to avoid intraoperative hypotension. The effect of loop diuretics is uncertain.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Three North American university centers.

Synopsis: One hundred ninety-three patients were instructed to take furosemide or placebo on the day they underwent noncardiac surgery. The primary outcome measure was perioperative hypotension defined as a SBP <90 mmHg for more than five minutes, a 35% drop in the mean arterial blood pressure, or the need for a vasopressor agent. The number of cardiovascular complications (acute heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, acute cerebrovascular event) and deaths also were analyzed.

Concerns have been raised that loop diuretics might predispose patients to a higher risk of intraoperative hypotension during noncardiac surgery. This trial showed no significant difference in the rates of intraoperative hypotension in patients who were administered furosemide versus those who were not. Although cardiovascular complications occurred more frequently in the furosemide group, the difference was not statistically significant.

Important limitations of the study were recognized. A larger population of patients could have revealed a statistically significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes in the furosemide group. Also, an anesthetic protocol was not utilized, which raises questions about the interaction of furosemide and effect on blood pressure with certain anesthetics.

Bottom line: Administering furosemide prior to surgery in chronic users does not appreciably increase the rate of intraoperative hypotension or cardiovascular events.

Citation: Khan NA, Campbell NR, Frost SD, et al. Risk of intraoperative hypotension with loop diuretics: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):1059e1-1059e8.

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk of adverse events with opioid use

- Drug of choice for outpatient treatment of cellulitis

- Preventing hospital falls

- Post-hospital outcomes based on status of PCP follow-up

- LOS, mortality, and readmission based on insurance

- Antiplatelets added to warfarin for atrial fibrillation.

- Cognitive effects of severe sepsis

- Effect of preoperative furosemide use

ED Visits Are Higher among Recipients of Chronic Opioid Therapy

Clinical question: Is there an association between the use of prescription opioids and adverse outcomes?

Background: Chronic opioid therapy is a common strategy for managing chronic, noncancer pain. There has been an increase in overdose deaths and ED visits (EDV) involving the use of prescription opioids.

Study design: Retrospective study from claims records.

Setting: Population in the Health Core Integrated Research Database, containing large, commercial insurance plans in 14 states, and Arkansas Medicaid.

Synopsis: Patients 18 and older without cancer diagnoses who used prescription opioids for at least 90 continuous days within a six-month period from 2000 to 2005 were examined for risk factors for EDVs and alcohol- or drug-related encounters (ADEs) in the 12 months following 90 days or more of prescribed opioids.

Patients with diagnoses of headache, back pain, and pre-existing substance-use disorders had significantly higher EDVs and ADEs. Opioid dose at morphine-equivalent doses over 120 mg per day doubled the risk of ADEs. The use of short-acting Schedule II opioids was associated with EDVs (relative risk, 1.09-1.74). The use of long-acting Schedule II opioids was strongly associated with ADEs (relative risk, 1.64-4.00).

Bottom line: In adults with noncancer pain prescribed opioids for 90 days or more, short-acting Schedule II opioid use was associated with an increased number of EDVs, and long-acting opioid use was associated with an increased number of ADEs. Minimizing Schedule II opioid prescription in these higher-risk patients might be prudent to increase patient safety.

Citation: Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MI, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170(16):1425-1432.

Empiric Outpatient Therapy with Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole or Clindamycin Is Preferred for Cellulitis

Clinical question: What is the best empiric outpatient oral antibiotic treatment for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-associated MRSA infections?

Background: The increasing rates of community-associated MRSA skin and soft-tissue infections have raised concerns that such beta-lactams as cephalexin and other semisynthetic penicillins are not appropriate for empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis.

Study design: Three-year, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A teaching clinic of a tertiary-care medical center in Hawaii.

Synopsis: More than 540 patients with cellulitis were identified from January 2005 to December 2007. Of these, 139 patients were excluded for reasons such as hospitalization, surgical intervention, etc. In the final cohort of 405 patients, the three most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics were cephalexin (44%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (38%), and clindamycin (10%). Other antibiotics accounted for the remaining 8%.

MRSA was recovered in 62% of positive culture specimens. The success rate of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was 91% vs. 74% in the cephalexin group (P<0.001). Clindamycin success rates were higher than those of cephalexin in patients who had subsequently confirmed MRSA infections (P=0.01) and moderately severe cellulitis (P=0.03) and were obese (P=0.04).

Bottom line: Antibiotics with activity against community-acquired MRSA (e.g. trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole and clinidamycin) are the preferred empiric outpatient therapy for cellulitis in areas with a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA.

Citation: Khawcharoenporn T, Tice A. Empiric outpatient therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, or clindamycin for cellulitis. Am J Med. 2010;123(10):942-950.

Patient-Specific Screening with Health Information Technology Prevents Falls

Clinical question: Does a fall-prevention toolkit using health information technology decrease patient falls in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inpatient falls and fall-related injuries result in substantial morbidity and additional healthcare costs. While specific fall-prevention strategies were a longstanding target for intervention, little evidence exists to link them with decreased fall rates.

Study design: Cluster-randomized study.

Setting: Four urban hospitals in Massachusetts.

Synopsis: Comparing patient fall rates in four acute-care hospitals between units providing usual care (5,104 patients) and units using a health information technology (HIT)-linked fall prevention toolkit (5,160 patients), this study demonstrated significant fall reduction in older inpatients. The intervention integrated existing workflow and validated fall risk assessment (Morse Falls Scale) into an HIT software application that tailored fall-prevention interventions to patients’ specific fall risk determinants. The toolkit produced bed posters, patient education handouts, and plans of care communicating patient-specific alerts to key stakeholders.

The primary outcome was patient falls per 1,000 patient-days during the six-month intervention period. The number of patients with falls was significantly different (P=0.02) between control (n=87) and intervention (n=67) units. The toolkit prevented one fall per 862 patient-days.

This nonblinded study was limited by the fact that it was conducted in a single health system. The toolkit was not effective in patients less than 65 years of age. Additionally, the sample size did not have sufficient power to detect effectiveness in preventing repeat falls or falls with injury.

Bottom line: Patient-specific fall prevention strategy coupled with HIT reduces falls in older inpatients.

Citation: Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1912-1918.

Lack of Timely Outpatient Follow-Up Results in Higher Readmission Rates

Clinical question: Does timely primary-care-physician (PCP) follow-up improve outcomes and prevent hospital readmissions?

Background: Active PCP involvement is key to interventions aimed at reducing readmissions and ensuring effective ongoing patient care. Some studies suggest increased overall resource utilization when PCP follow-up occurs after hospitalization. Resource utilization and clinical outcomes after hospitalization related to timely PCP follow-up have not been adequately studied.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: An urban, academic, 425-bed tertiary-care center in Colorado.

Synopsis: From a convenience sample of 121 patients admitted to general medicine services during winter months, 65 patients completed the study. Demographics, diagnosis, payor source, and PCP information were collected upon enrollment. Post-discharge phone calls and patient surveys were used to determine follow-up and readmission status. Timely PCP follow-up was defined as a visit with a PCP or specialist related to the discharge diagnosis within four weeks of hospital discharge.

Thirty-day readmission rates and hospital length of stay were compared for those with timely PCP follow-up and those without. Less than half of general-medicine inpatients received timely PCP follow-up post-discharge. Lack of timely PCP follow-up was associated with younger age, a 10-fold increase in 30-day readmission for the same condition, and a trend toward longer length of stay. However, hospital readmission for any condition did not differ with lack of timely PCP follow-up.

This small, single-center study with convenience sample enrollment might not represent all medical inpatients or diagnoses. Determination of same-condition readmission was potentially subjective.

Bottom line: Patients who lack timely post-discharge follow-up have higher readmission rates for the same medical condition.

Citation: Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

Compared with Uninsured and Medicaid Patients, Privately Insured Patients Admitted for Acute MI, Stroke, and Pneumonia Have Better Mortality Rates

Clinical question: Do outcomes for insured and underinsured patients vary for three of the most common medical conditions for which patients are hospitalized: acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke, and pneumonia?

Background: The ideal healthcare system would provide quality care to all individuals regardless of insurance status. Nevertheless, disparities in outcomes for the insured and underinsured or uninsured are well-documented in the outpatient setting but not as well in the inpatient setting. More needs to be done to address these potential disparities.

Study design: Retrospective database analysis.

Setting: Database including 20% of all U.S. community hospitals, including public hospitals, academic medical centers, and specialty hospitals.

Synopsis: This study utilized a database of 8 million discharges from more than 1,000 hospitals and isolated patients 18-64 years old (154,381 patients). Privately insured, uninsured, and Medicaid patients’ data were reviewed for in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost per hospitalization. The analysis took into account disease severity, comorbidities, and the proportion of underinsured patients receiving care in each hospital when insurance-related disparities were examined.

Compared with the privately insured, in-hospital mortality and LOS for AMI and stroke were significantly higher for uninsured and Medicaid patients. Among pneumonia patients, Medicaid patients had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and LOS than the other two groups. Cost per hospitalization was highest for all three conditions in the Medicaid group; the uninsured group had the lowest costs for all three conditions.

Unfortunately, the three conditions analyzed only comprise 8% of annual hospital discharges, so the findings cannot be generalized. Also, deaths occurring soon after hospital discharge were not included, and uninsured and Medicaid patients are likely to have more severe diseases, which, rather than insurance status, could account for the mortality differences.

Bottom line: In-hospital mortality and resource use for three common medical conditions vary significantly between privately insured and uninsured or Medicaid patients, highlighting the need to take measures to close this gap.

Citation: Hasan O, Orav EJ, LeRoi LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8);452-459.

Warfarin Monotherapy Best in Prevention of Thromboembolic Events for Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to adding an antiplatelet agent to warfarin for the prevention of thromboembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation?

Background: Many physicians prescribe various combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin, as these treatments are endorsed in guidelines and expert statements. The use of these medications, however, has not been studied in a setting large enough to understand the safety of these therapies.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: All Danish hospitals.

Synopsis: All hospitalized patients in Denmark from 1997 to 2006 who were identified with new onset atrial fibrillation (n=118,606) were monitored for outcomes and the use of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin. These patients were followed for a mean of 3.3 years with the primary endpoint being admission to a hospital for a diagnosis of bleeding and a secondary endpoint of stroke.

Bleeding occurred in 13,573 patients (11.4%). The incidence of bleeding was highest in the first 180 days and then leveled off. Hazard ratios were computed with warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Only the hazard ratio for aspirin monotherapy (0.93) was lower (confidence interval [CI] 0.88-0.98). The highest risk of bleeding was with the triple therapy warfarin-aspirin-clopidogrel, which had a hazard ratio of 3.70 (CI 2.89-4.76).

For strokes, the hazard ratio was slightly better for warfarin-clopidogrel (0.70), although the CI was wide at 0.35-1.4 compared to warfarin monotherapy as a reference. Hazard ratios for monotherapy with clopidogrel or aspirin, dual therapy, and triple therapy all were worse, ranging from 1.27 to 1.86.

Bottom line: Warfarin as a monotherapy might have a bleeding risk comparable to that of aspirin or clopidogrel alone, and prevents more strokes than various combinations of these medications.

Citation: Hansen ML, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170 (16):1433-1441.

Cognitive and Physical Function Declines in Elderly Severe Sepsis Survivors

Clinical question: Is there a change in cognitive and physical functioning after severe sepsis?

Background: Disability is associated with increased mortality, decreased quality of life, and increased burdens by families and healthcare costs. After severe sepsis, the lasting effects of debility have not been investigated in any large studies.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitalized Medicare patients participating in the Health and Retirement Study.

Synopsis: Patients (n=1194) were followed for a minimum of one year between 1998 and 2006. The outcomes were measured by multiple personal interviews before and after a severe sepsis episode. Cognitive impairment was measured using three validated questionnaires dependent upon age or if a proxy was the respondent. For functional limitations, a questionnaire concerning instrumental and basic activities of daily living was used.

Cognitive impairment for those with moderate to severe impairment increased to 16.7% from 6.1% after a sepsis episode with an odds ratio of 3.34 (95% confidence interval 1.53-7.25). There was no significant increase in nonsevere sepsis hospitalized comparison patients (n=5574). All survivors with severe sepsis had a functional decline of 1.5 activities. The comparison group had about a 0.4 activity decline. All of these deficits endured throughout the study.

The authors provide comments that there should be a system-based approach in preventing severe sepsis, its burdens, and its costs. Suggestions include preventing delirium, initiating better standards of care, and involving therapists earlier to prevent immobility.

Bottom line: Severe sepsis is independently associated with enduring cognitive and physical functional declines, which strain families and our healthcare system.

Citation: Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787-1794.

Furosemide on Day of Elective Noncardiac Surgery Does Not Increase Risk of Intraoperative Hypotension

Clinical question: For patients chronically treated with loop diuretics, does withholding furosemide on the day of elective noncardiac surgery prevent intraoperative hypotension?

Background: Recent studies have questioned the safety of blood-pressure-lowering medications administered on the day of surgery. Beta-blockers have been associated with an increase in strokes and death perioperatively, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are frequently withheld on the day of surgery to avoid intraoperative hypotension. The effect of loop diuretics is uncertain.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Three North American university centers.

Synopsis: One hundred ninety-three patients were instructed to take furosemide or placebo on the day they underwent noncardiac surgery. The primary outcome measure was perioperative hypotension defined as a SBP <90 mmHg for more than five minutes, a 35% drop in the mean arterial blood pressure, or the need for a vasopressor agent. The number of cardiovascular complications (acute heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, acute cerebrovascular event) and deaths also were analyzed.

Concerns have been raised that loop diuretics might predispose patients to a higher risk of intraoperative hypotension during noncardiac surgery. This trial showed no significant difference in the rates of intraoperative hypotension in patients who were administered furosemide versus those who were not. Although cardiovascular complications occurred more frequently in the furosemide group, the difference was not statistically significant.

Important limitations of the study were recognized. A larger population of patients could have revealed a statistically significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes in the furosemide group. Also, an anesthetic protocol was not utilized, which raises questions about the interaction of furosemide and effect on blood pressure with certain anesthetics.

Bottom line: Administering furosemide prior to surgery in chronic users does not appreciably increase the rate of intraoperative hypotension or cardiovascular events.

Citation: Khan NA, Campbell NR, Frost SD, et al. Risk of intraoperative hypotension with loop diuretics: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):1059e1-1059e8.

CPT 2011 Update

In the past, observation services typically did not exceed 24 hours or two calendar days. However, changes in healthcare policy coupled with the impetus to reduce wasteful spending have spurred an atmosphere of scrutiny over hospital admissions. Sometimes there are discrepancies between a hospital’s utilization review committee and a payor’s utilization review committee in determining the appropriateness of healthcare services and supplies, in accordance with each party’s definition of medical necessity. This situation has caused an increase in both the number and cost of observation stays.

In response, subsequent observation-care codes (99224-99226) were developed and published in the 2011 edition of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).1

Codes and Their Uses

CPT outlines three subsequent observation care codes:

- 99224: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the evaluation and management (E/M) of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: problem-focused interval history; problem-focused examination; and medical decision-making that is straightforward or of low complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is stable, recovering, or improving. Physicians typically spend 15 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99225: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: expanded problem focused interval history; expanded problem focused examination; and medical decision-making of moderate complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is responding inadequately to therapy or has developed a minor complication. Physicians typically spend 25 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99226: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: detailed interval history; detailed examination; and medical decision-making of high complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem. Physicians typically spend 35 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

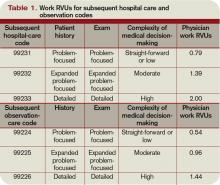

Subsequent observation-care codes replicate the key components and time requirements established for subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233). However, the relative value units (RVUs) of physician work associated with subsequent observation care are not weighted equally (see Table 1, below). Subsequent observation care is a less-intense service, and therefore is valued at a lesser rate.

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation (OBS); indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. Specialists typically are called onto an OBS case for their opinion/advice (i.e. consultants) but do not function as the attending of record.

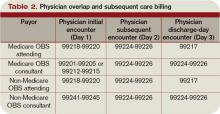

According to CPT 2011, subsequent OBS care codes can be reported by both the attending physician of record and specialists who provide medically necessary, nonoverlapping care to patients on any day other than the admission or discharge day (see Table 2, above). At press time, CMS and private payors had not provided written clarification on the use of subsequent observation-care codes. Therefore, it is imperative to monitor payments, denials, and policy clarifications providing further billing instruction.

On the Horizon

Prior reporting guidelines required the reporting of subsequent observation-care days with established outpatient codes (99212-99215). Some member plans insisted on referrals for all outpatient visits regardless nature of the service. Without the mandated referral for established patient visits performed in the observation setting, physician services were denied for coverage.

The creation of subsequent observation codes might play a role in decreasing these denials. Be sure to review the private payors’ fee schedules for inclusion of 99224-99226 codes. If missing, contact the payor or include it as an agenda item during your contract negotiations.

For more information on observation care services, check out “Observation Care” in the July 2010 issue of The Hospitalist. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology: Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2011.

In the past, observation services typically did not exceed 24 hours or two calendar days. However, changes in healthcare policy coupled with the impetus to reduce wasteful spending have spurred an atmosphere of scrutiny over hospital admissions. Sometimes there are discrepancies between a hospital’s utilization review committee and a payor’s utilization review committee in determining the appropriateness of healthcare services and supplies, in accordance with each party’s definition of medical necessity. This situation has caused an increase in both the number and cost of observation stays.

In response, subsequent observation-care codes (99224-99226) were developed and published in the 2011 edition of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).1

Codes and Their Uses

CPT outlines three subsequent observation care codes: