User login

“Patchy” pneumonia

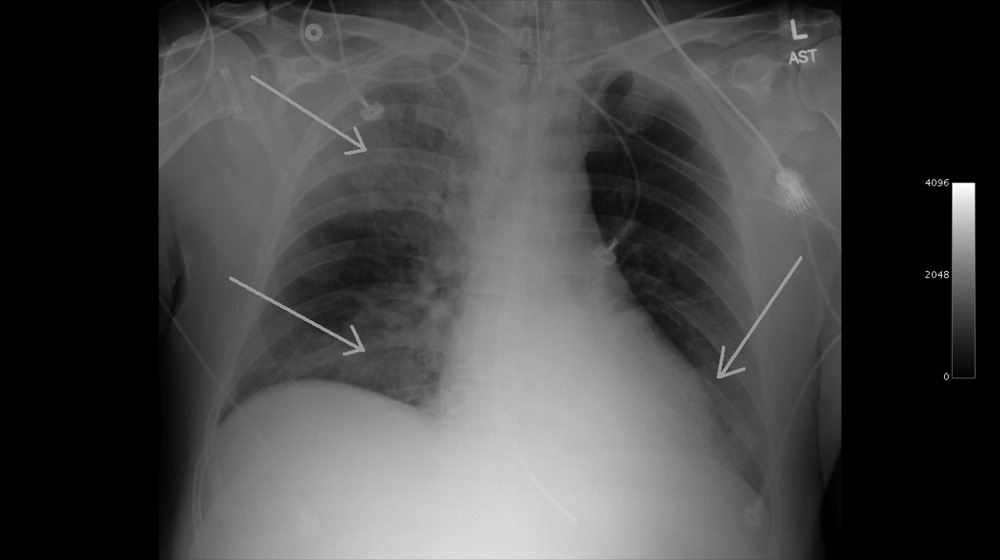

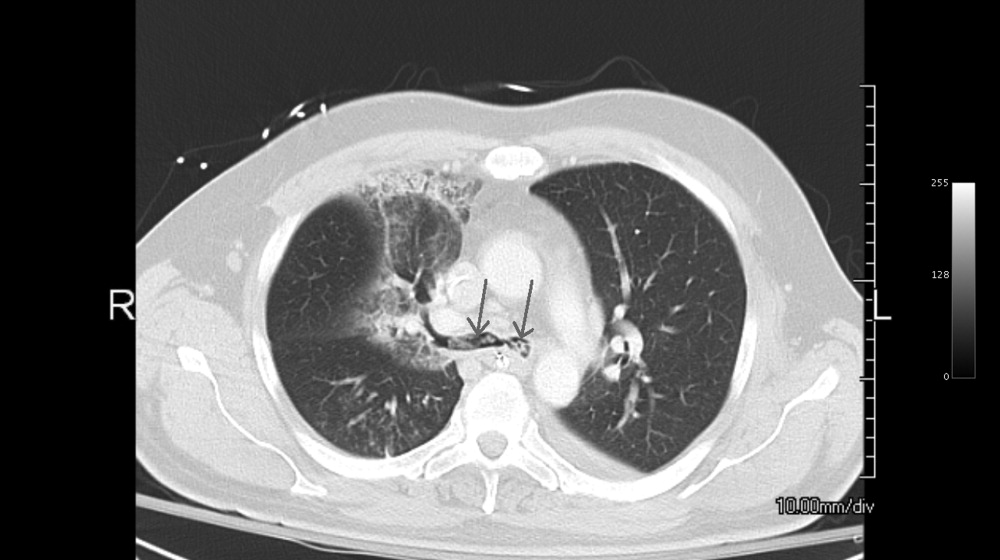

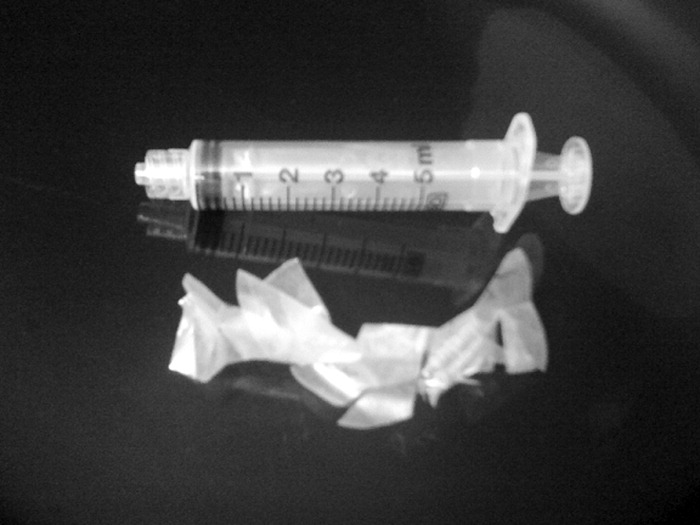

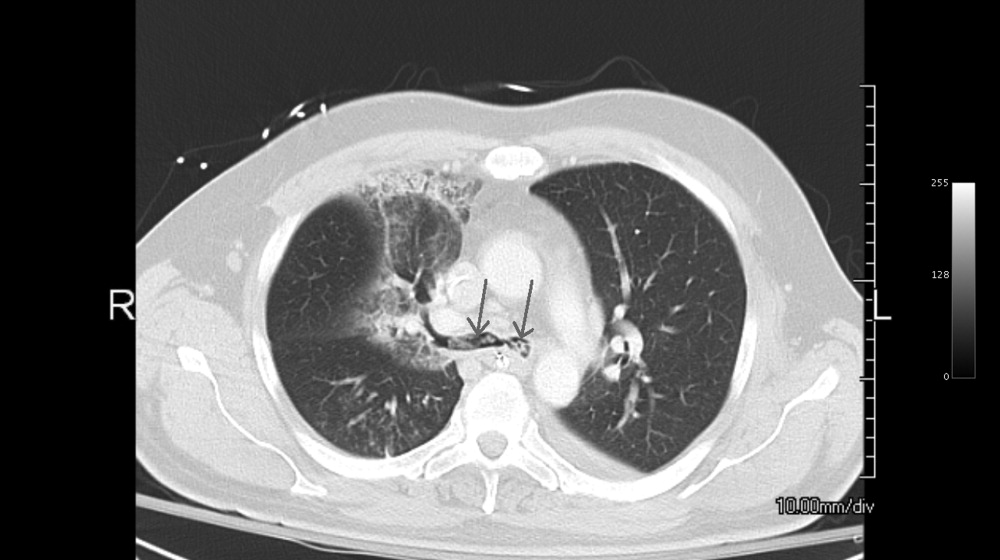

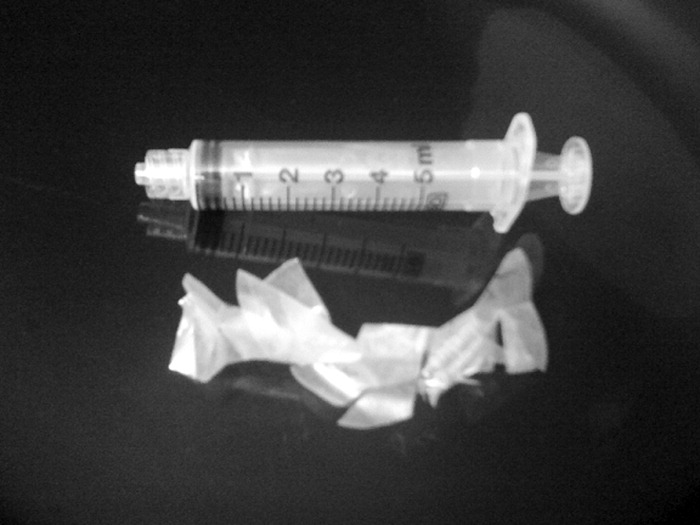

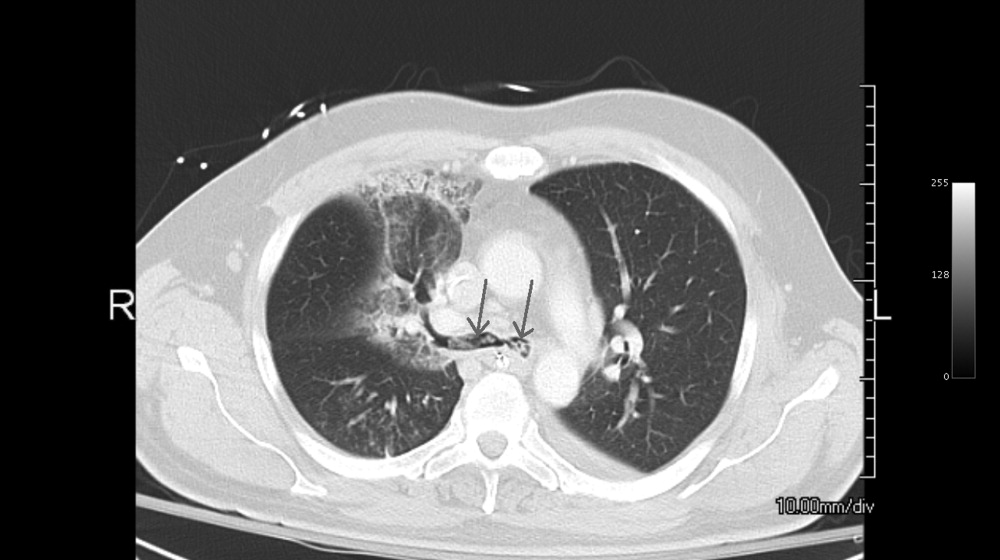

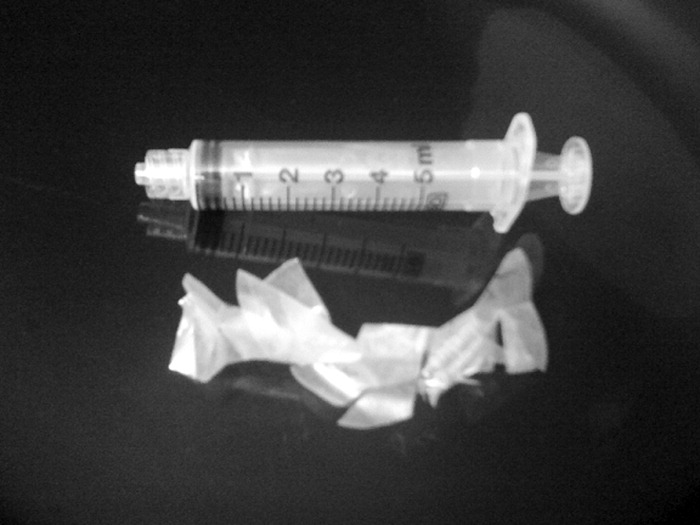

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

Language Barriers and Hospital Care

Forty‐five‐million Americans speak a language other than English and more than 19 million of these speak English less than very wellor are limited English proficient (LEP).1 The number of non‐English‐speaking and LEP people in the US has risen in recent decades, presenting a challenge to healthcare systems to provide high‐quality, patient‐centered care for these patients.2

For outpatients, language barriers are a fundamental contributor to gaps in health care. In the clinic setting, patients who do not speak English well have less access to a usual source of care and lower rates of physician visits and preventive services.36 Even when patients with language barriers do have access to care, they have poorer adherence, decreased comprehension of their diagnoses, decreased satisfaction with care, and increased medication complications.710

Few studies, however, have examined how language influences outcomes of hospital care. Compared to English‐speakers, patients who do not speak English well may experience longer lengths of stay,11 and have more adverse events while in the hospital.12 However, these previous studies have not investigated outcomes immediately post‐hospitalization, such as readmission rates and mortality, nor have they directly addressed the interaction between ethnicity and language.

To understand these questions, we analyzed data collected from a university‐based teaching hospital which cares for patients of diverse cultural and language backgrounds. Using these data, we examined how patients' primary language influenced hospital costs, length of stay (LOS), 30‐day readmission, and 30‐day mortality risk.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population and Setting

Our study examined patients admitted to the General Medicine Service at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) between July 1, 2001 and June 30th, 2003, the time period during which UCSF participated in the Multicenter Hospitalist Trial (MHT) a prospective quasi‐randomized trial of hospitalist care for general medicine patients.13, 14

UCSF Moffitt‐Long Hospital is a 400‐bed urban academic medical center which provides services to the City and County of San Francisco, an ethnically and linguistically diverse area. UCSF employs staff language interpreters in Spanish, Chinese and Russian who travel to its many outpatient clinics, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Children's Hospital, as well as to Moffitt‐Long Hospital upon request; phone interpretation is also available when in‐person interpreters are not available, for off hours needs and for less common languages. During the period of this study there were no specific inpatient guidelines in place for use of interpretation services at UCSF, nor were there any specific interventions targeting LEP or non‐English speaking inpatients.

Patients were eligible for the MHT if they were 18 years of age or older and admitted at random to a hospitalist or non‐hospitalist physician (eg, outpatient general internist attending on average 1‐month/year); a minority of patients were cared for directly by their primary care physician while in the hospital, and were excluded. For purposes of our study, which merged MHT data with hospital administrative data on primary language, we further excluded all admissions for patients for whom primary language was missing (n = 5), whose listing was unknown or other language (n = 78), sign language (n = 3) or whose language was listed but was not one of the included languages (n = 258). Included languages were English, Chinese, Russian and Spanish. Because LOS and cost data were skewed, we excluded those admissions with the top 1% longest stays and the top 1% highest cost (n = 176); these exclusions did not alter the proportion of admissions across language and ethnicity. In addition, we excluded 102 admissions that were missing data on cost and 11 with costs <$500 and which were likely to be erroneous. Our research was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Data Sources

We collected administrative data from Transition Systems Inc (TSI, Boston, MA) billing databases at UCSF as part of the MHT. These data include patient demographics, insurance, costs, ICD‐9CM diagnostic codes, admission and discharge dates in Uniform Bill 92 format. Patient mortality information was collected as part of the MHT using the National Death Index.14

Language data were collected from a separate patient‐registration database (STOR) at UCSF. Information on a patient's primary language is entered at the time each patient first registers at UCSF, whether for the index hospitalization or for prior clinic visits, and is based generally on patient self report. As part of our validation step, we cross‐checked 829 STOR language entries against patient reports and found 91% agreement with the majority of the errors classifying non‐English speakers as English‐speakers.

Measures

Predictor

Our primary language variable was derived using language designations collected from patient registration databases described above. Using these data we specified our key language groups as English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), Russian, or Spanish.

Outcomes

LOS and total cost of hospital stay for each hospitalization derived from administrative data sources. Readmissions were identified at the time patients were readmitted to UCSF (eg, flagged in administrative data). Mortality was determined by whether an individual patient with an admission in the database was recorded in the National Death Index as dead within 30‐days of admission.

Covariates

Additional covariates included age at admission, gender, ethnicity as recorded in registration databases (White, African American, Asian, Latino, Other), insurance, principal billing diagnosis, whether or not a patient received intensive care unit (ICU) care, type of admitting attending physician (Hospitalist/non‐Hospitalist), and an administrative Charlson comorbidity score.15 To collapse the principal diagnoses into categories, we used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)'s Clinical Classification System, which allowed us to classify each diagnosis in 1 of 14 generally accepted categories.16

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (STATACorp, Version 9, College Station, TX). We examined descriptive means and proportions for all variables, including sociodemographic, hospitalization, comorbidity and outcome variables. We compared English and non‐English speakers on all covariate and outcome variables using t‐tests for comparison of means and chi‐square for comparison of categorical variables.

It was not possible to fully test the language‐by‐ethnicity interactionwhether or not the impact of language varied by ethnic groupbecause many cells of the joint distribution were very sparse (eg, the sample contained very few non‐English‐speaking African Americans). Therefore, to better understand the influence of English vs. non‐English language usage across different ethnic groups, we created a combined language‐ethnicity predictor variable which categorized each subject first by language and then for the English‐speakers by ethnicity. For example, a Chinese, Spanish or Russian speaker would be categorized as such, and an English‐speaker could fall into the English‐White, English‐African American, English‐Asian or English‐Latino group. This allowed us to test whether there were any differences in language effects across the White, Asian, and Latino ethnicities, and any difference in ethnicity effects among English‐speakers.

Because cost and LOS were skewed, we used negative binomial models for LOS and log transformed costs. We performed a sensitivity analysis testing whether our results were robust to the exclusion of the admissions with the top 1% LOS and top 1% cost. We used logistic regression for the 30‐day readmission and mortality outcomes.

Our primary predictor was the language‐ethnicity variable described above. To determine the independent association between this predictor and our key outcomes, we then built models which included additional potential confounders selected either for face validity or because of observed confounding with other covariates. Our inclusion of potential confounders was limited by the variables available in the administrative database; thus, we were not able to pursue detailed analyses of communication and literacy factors and their interaction with our predictor or their independent impact on outcomes. Models also included a linear spline with a single knot at age 65 years as a further adjustment for age in Medicare recipients.1719 For the 30‐day readmission outcome model, we excluded those admissions for which the patient either died in the hospital or was discharged to hospice care. Within each model we tested the impact of a language barrier using custom contrasts. This allowed us to examine the language‐ethnicity effect aggregating all non‐English speakers compared to all English‐speakers, comparing each non‐English speaking group to all English‐speakers, comparing Chinese speakers to English‐speaking Asians and Spanish speakers to English‐speaking‐Latinos, as well as to test whether the effect of English language is the same across ethnicities.

Results

Admission Characteristics of the Sample

A total of 7023 patients were admitted to the General Medicine service, 5877 (84%) of whom were English‐speakers and 1146 (16%) non‐English‐speakers (Table 1). Overall, half of the admitted patients were women (50%), and the vast majority was insured (93%). The most common principal diagnoses were respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders. Only a small number of non‐English speakers 164 (14%) were recorded in the UCSF Interpreter Services database as having had any interaction with a professional staff interpreter during their hospitalization.

| English (n = 5877) n (%) | Non‐English (n = 1146) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Socio‐economic variables | ||

| Language‐ethnicity | ||

| English | ||

| White | 3066 (52.2) | |

| African American | 1351 (23.0) | |

| Asian | 544 (9.3) | |

| Latino | 298 (5.1) | |

| Other | 618 (10.5) | |

| Chinese speakers | 584 (51.0) | |

| Spanish speakers | 272 (25.3) | |

| Russian speakers | 290 (23.7) | |

| Age mean (SD) (range 18‐105) | 58.8 (20.3) | 72.3 (15.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2967 (50.5) | 514 (44.8) |

| Female | 2910 (49.5) | 632 (55.2) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 2878 (49.0) | 800 (69.8) |

| Medicaid | 1201 (20.4) | 193 (16.8) |

| Commercial | 1358 (23.1) | 106 (9.3) |

| Charity/other | 440 (7.5) | 47 (4.1) |

| Hospitalization variables | ||

| Admitted to ICU | ||

| Yes | 721 (12.3) | 149 (13.0) |

| Attending physician | ||

| Hospitalist | 3950 (67.2) | 781 (68.2) |

| Comorbidity variables | ||

| Principal Diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory disorder | 1061 (18.1) | 225 (19.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 963 (16.4) | 205 (17.9) |

| Circulatory disorder | 613 (10.4) | 140 (12.2) |

| Endocrine/metabolism | 671 (11.4) | 80 (7.0) |

| Injury/poisoning | 475 (8.1) | 64 (5.6) |

| Malignancy | 395 (6.7) | 107 (9.3) |

| Renal/urinary disorder | 383 (6.5) | 108 (9.4) |

| Skin disorder | 278 (4.7) | 28 (2.9) |

| Infection/fatigue NOS | 206 (3.5) | 45 (3.4) |

| Blood disorder (non‐malignant) | 189 (3.2) | 38 (3.3) |

| Musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorder | 164 (2.8) | 33 (2.9) |

| Mental disorder/substance abuse | 171 (2.9) | 7 (0.6) |

| Nervous system/brain infection | 137 (2.3) | 26 (2.3) |

| Unclassified | 171 (2.9) | 40 (3.5) |

| Charlson Index score mean (SD) | 0.97 1.33 | 1.10 1.42 |

Among English speakers, Whites and African Americans were the most common ethnicities; however, more than 500 admissions were categorized as Asian ethnicity, and more than 600 as patients of other ethnicity. Close to 300 admissions were for Latinos. Among non‐English speakers, Chinese speakers had the largest number of admissions (n = 584), while Spanish and Russian speakers had similar numbers (n = 272 and 290 respectively).

Non‐English speakers were older, more likely to be female, more likely to be insured by Medicare, and more likely to have a higher comorbidity index score. While comorbidity scores were similar among non‐English speakers (Chinese 1.13 1.50; Russian 1.09 1.37; Spanish 1.06 1.30), they differed considerably among English speakers (White 0.94 1.29; African American 1.05 1.40; Asian 1.04 1.45; Latino 0.89 1.23; Other 0.91 1.29).

Hospital Outcome by Language‐Ethnicity Group (Table 2)

When aggregated together, non‐English speakers were somewhat more likely to be dead at 30‐days and have lower cost admissions; however, they did not differ from English speakers on LOS or readmission rates. While differences among disaggregated language‐ethnicity groups were not all statistically significant, English‐speaking Whites had the longest LOS (mean = 4.9 days) and highest costs (mean = $10,530). English‐speaking African Americans, Chinese and Spanish speakers had the highest 30‐day readmission rates; whereas, English‐speaking Latinos and Russian speakers had markedly lower 30‐day readmission rates (2.5% and 6.4%, respectively). Chinese speakers had the highest 30‐day mortality, followed by English speaking Whites and Asians.

| Language‐Ethnicity Groups | LOS* Mean #Days (SD) | Cost Mean Cost $ (SD) | 30‐Day Readmission, n (%) | 30‐Day Mortality, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| English speakers (all) | 4.7 (4.5) | 10,035 (15,041) | 648 (11.9) | 613 (10.4) |

| White | 4.9 (5.1) | 10,530 (15,894) | 322 (11.4) | 377 (12.3) |

| African American | 4.5 (4.8) | 9107 (13,314) | 227 (17.5) | 91 (6.7) |

| Asian | 4.3 (4.5) | 9933 (15,607) | 43 (8.8) | 67 (12.3) |

| Latino | 4.6 (4.8) | 9823 (14,113) | 7 (2.5) | 18 (6.0) |

| Other | 4.5 (4.8) | 9662 (14,016) | 49 (8.5) | 60 (9.7) |

| Non‐English speakers (all) | 4.5 (4.5) | 9515 (13,213) | 117 (11.0) | 147 (12.8) |

| Chinese speakers | 4.5 (4.6) | 9505 (12,841) | 69 (12.8) | 85 (14.6) |

| Spanish speakers | 4.5 (4.5) | 9115 (13,846) | 31 (12.0) | 28 (10.3) |

| Russian speakers | 4.7 (4.2) | 9846 (13,360) | 17 (6.4) | 34 (11.7) |

We further investigated differences among English speakers to better understand the very high rate of readmission for African Americans and the very low rate for English‐speaking Latinos. African Americans were on average younger than other English speakers (55 19 years vs. 60 21 years; P < 0.001); but, they had higher comorbidity scores than other English speakers (1.05 1.40 vs. 0.94 1.31; P = 0.008), and were more likely to be admitted for non‐malignant blood disorders (eg, sickle cell disease), endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes mellitus), and circulatory disorders (eg, stroke). In contrast, English‐speaking Latinos were also younger than other English speakers (53 21 years vs. 59 20 years; P < 0.001), but they trended toward lower comorbidity scores (0.87 1.23 vs. 0.97 1.33; P = 0.2), and were more likely to be admitted for gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders, and less likely to be admitted for malignancy and endocrine disorders.

Multivariate Analyses: Association of Aggregated and Disaggregated Language‐Ethnicity Groups With Hospital Outcomes (Table 3)

In multivariate models examining aggregated language‐ethnicity groups, non‐English speakers had a trend toward higher odds of readmission at 30‐days post‐discharge than the English‐speaking group (odds ratio [OR], 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0‐1.7). There were no significant differences for LOS, cost, or 30‐day mortality. Compared to English speakers, Chinese and Spanish speakers had 70% and 50% higher adjusted odds of readmission at 30‐days post‐discharge respectively, while Russian speakers' odds of readmission was not increased. Additionally, Chinese speakers had 7% shorter LOS than English‐speakers. There were no significant differences among any of the language‐ethnicity groups for 30‐day mortality. The increased odds of readmission for Chinese and Spanish speakers compared to English speakers was robust to reinclusion of the admissions with the top 1% LOS and top 1% cost.

| Language Categorization | LOS, % Difference (95% CI) | Total Cost, % Difference (95% CI) | 30‐Day Readmission,* OR (95% CI) | Mortality, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| All English speakers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non‐English speakers | 3.1 (8.7 to 3.1) | 2.5 (8.3 to 2.1) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| All English speakers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Chinese speakers | 7.2 (13.9 to 0) | 5.3 (12.2 to 2.1) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| Spanish speakers | 3.0 (12.6 to 7.6) | 3.0 (12.7 to 7.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) |

| Russian speakers | 1.5 (8.3 to 12.2) | 0.9 (8.9 to 11.8) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) |

Multivariate Analyses: Association of Language for Asians and Latinos, and of Ethnicity for English speakers, With Hospital Outcomes (Table 4)

Both Chinese and Spanish speakers had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission than their English speaking Asian and Latino counterparts. There were no significant differences in LOS, cost, or 30‐day mortality in this within‐ethnicity analysis. Among English speakers, admissions for patients with Asian ethnicity were 15% shorter and resulted in 9% lower costs than for Whites. While LOS and cost were similar for English‐speaking Latino and White admissions, English‐speaking Latinos had markedly lower odds of 30‐day readmission than their White counterparts. Whereas African‐Americans had 6% shorter LOS, 40% higher odds of readmission and 30% lower odds of mortality at 30‐days than English speaking Whites.

| Language‐Ethnicity Comparisons | LOS, % Difference (95% CI) | Total Cost, % Difference (95% CI) | 30‐Day Readmission,* OR (95% CI) | Mortality, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| English speaking Asians | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Chinese speakers | 2.2 (7.4 to 12.7) | 0.3 (9.2 to 10.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| English speaking Latinos | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Spanish speakers | 4.5 (16.8 to 9.5) | 1.2 (14.0 to 13.5) | 5.7 (2.4 to 13.2) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) |

| English‐White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| English‐African American | 6.2 (11.3 to 0.9) | 4.4 (9.6 to 1.1) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

| English‐Asian | 14.6 (20.9 to 7.9) | 8.6 (15.4 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| English‐Latino | 4.5 (13.5 to 5.4) | 5.0 (14.0 to 5.0) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) |

Conclusion/Discussion

Our results indicate that language barriers may contribute to higher readmission rates for non‐English speakers, but that they have less impact on care efficiency or mortality. This finding of an association between language and readmission, without a similar association with efficiency, suggests a potentially communication‐critical step in care.20, 21 Patients with language barriers are more likely to experience adverse events, and those events are often caused by errors in communication.12 It is conceivable that higher readmission risk for Chinese and Spanish speakers in our study was, at least in part, due to gaps in communication that are present in all patient groups, and exacerbated by the presence of a language barrier. This barrier is likely present during hospitalization but magnified at discharge, limiting caregivers' ability to understand patients' needs for home care, while simultaneously limiting patients' understanding of the discharge plan. After discharge, it is also possible that non‐English speakers are less able to communicate their needs as they arise, ormore subtlyfeel less supported by a primarily English speaking healthcare system. As in other clinical arenas,22 it is quite possible that increased access to professional interpreters in the hospital setting, and particularly at the time of discharge, would enhance communication and outcomes for LEP patients. Our interpreter services data showed that the patients in our study had quite limited access to staff professional interpreters.

Our findings differ somewhat from those of John‐Baptiste et al.,11 who found that language barriers contributed to increased LOS for patients with cardiac and major surgical diagnoses. Our study's findings are akin to recent research suggesting that being a monolingual Spanish speaker or receiving interpreter services may not significantly impact LOS or cost of hospitalization,23 and that LOS and in‐hospital mortality do not differ for non‐English speakers and English speakers after acute myocardial infarction.24 These studies, along with our results, suggest that that care efficiency in the hospital may be driven much more by clinical acuity (eg, the need to respond rapidly to urgent clinical signs such as hypotension, fever and respiratory distress) than by adequacy of communication. For example, elderly LEP patients may be even more likely than English speakers to have vigilant family members at the bedside throughout their hospitalization due to their need for communication assistance; these family members can quickly alert hospital staff to concerning changes in the patient's condition.

Our results also suggest the possibility that language and ethnicity are not monolithic concepts, and that even within language and ethnic groups there are potential differences in care pattern. For example, not speaking English may be a surrogate marker for unmeasured factors such as social supports and access to care. Language is intimately associated with culture; it remains plausible that cultural differences between highly acculturated and less acculturated members of a given ethno‐cultural group may have contributed to our observed differences in readmission rates. Differences in culture and associated factors, such as social support or use of multiple hospital systems, may account for lack of higher readmission risk in Russian speakers, while Chinese and Spanish speakers had higher readmission risk.

In addition, our finding that English‐speaking Latinos had lower readmission risk than any other group may be more consistent with their clinical characteristicseg, younger age, fewer comorbiditiesthan with cultural factors. Our finding that African American patients had the highest readmission risk in our hospital was both surprising and concerning. Some of this increased risk may be explained by clinical characteristics, such as higher comorbidities and higher rates of diagnoses leading to frequent admissions (eg, sickle cell disease); however, the reasons for this disparity deserves further investigation.

Our study has limitations. First, our data are administrative, and lack information about patients' educational attainment, social support, acculturation, utilization of other hospital systems, and usual source of care. Despite this, we were able to account for many significant covariates that might contribute to readmission rates, including age, insurance status, gender, comorbidities, and admission to the intensive care unit.2528 Second, our information about patients' English language proficiency is limited. While direct assessments of English proficiency are more accurate ways to determine a patient's ability to communicate with health care providers in English,29 our language validation work conducted in preparation for this study suggests that most of our patients recorded as having a non‐English primary language (87%) also have a low score on a language acculturation scale.

Third, only 14% of our non‐English speaking subjects utilized professional staff interpreters, and we had no information on the use of professional telephonic interpreters, or ad hoc interpretersfamily members, non‐interpreter staff membersand their impact on our results. It is well‐documented that ad hoc interpreters are used frequently in healthcare, particularly in the hospital setting, and thus we can assume this to be true in our study.30, 31 As noted above, it is likely that the advocacy of family members and friends at the bedside helped to minimize potential differences in care efficiency for patients with language barriers. Finally, our study was performed at a single university based hospital and may not produce results which are applicable to other care settings.

Our findings point to several avenues for future research on language barriers and hospitalized patients. First, the field would benefit from an examination of the impact of easy access to professional interpreters during hospitalization on outcomes of hospital care, in particular on readmission rates. Second, there is need for development and assessment of best practices for creating a culture of professional interpreter utilization in the hospital among physicians and nursing staff. Third, investigation of the role of caregiver presence in the hospital room and how this might differ by patient culture, age and language ability may further elucidate some of the differences across language groups observed in our study. Lastly, a more granular investigation of clinician‐patient communication and the importance of interpersonal processes of care on both patient satisfaction and understanding of and adherence to discharge instructions could lead to the development of detailed interventions to enhance this communication and these outcomes as it has done for communication‐sensitive outcomes in the outpatient arena.3234

In summary, our study suggests that higher risk for readmission can be added to the unfortunate list of outcomes which are worsened due to language barriers, pointing to transition from the hospital as a potentially communication‐critical step in care which may be amenable to intervention. Our findings also suggest that this risk can vary even between groups of patients who do not speak English primarily. Whether and to what degree language and communication barriers aloneincluding access to professional interpreters and patient‐centered communicationduring hospitalization, or differences in caregiver social support both during and after hospitalization as well as access to care post‐hospitalization contribute to these findings is a worthy subject of future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Eliseo J. Prez‐Stable for his mentorship on this project.

- ,. Language Use and English‐Speaking Ability:2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr‐29.pdf. Accessed January 2010.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.2006National Healthcare Disparities Report. AHRQ Publication No. 070012; 2006.

- ,,,.Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample.Med Care.2002;40(1):52–59.

- ,.The effect of physician‐patient communication on mammography utilization by different ethnic groups.Med Care.1991;29(11):1065–1082.

- ,.Language of interview:relevance for research of Southwest Hispanics.Am J Pub Health.1991;81(11):1399–1404.

- ,,,.Is language a barrier to the use of preventive services?J Gen Intern Med.1997;12(8):472–477.

- ,,,.Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department.JGIM.1999;14:82–87.

- .Patient comprehension of doctor‐patient communication on discharge from the emergency department.J Emerg Med.1997;15(1):1–7.

- ,,, et al.Drug complications in outpatients.J Gen Intern Med.2000;15:149–154.

- .Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma.Med Care.1988;26(12):1119–1128.

- ,,,et al.The effect of English language proficiency on length of stay and in‐hospital mortality.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:221–228.

- ,,,.Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study.Int J Qual Health Care.2007;19(2):60–67.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with discussion of care plans and code status at the time of hospital admission: results from the Multicenter Hospitalist Study.J Hosp Med.2008;3(6):437–445.

- ,,, et al.Quality of care for decompensated heart failure: comparable performance between academic hospitalists and non‐hospitalists.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(9):1399–1406.

- ,,,.A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation.J Chronic Dis.1987;40(5):373–383.

- AHRQ. Healthcare Cost and Utilizlation Project: Tools 132(3):191–200.

- ,,.Free knot splines for logistic models and threshold selection.Comput Methods Programs Biomed.2005;77(1):1–9.

- ,,,,.Statistical methods in epidemiology: a comparison of statistical methods to analyze dose‐response and trend analysis in epidemiologic studies.J Clin Epidemiol.1998;51(12):1223–1233.

- The Care Transitions Project. Health Care Policy and Research, Practitioner Tools. Available at: http://www.caretransitions.org/practitioner_tools.asp.

- AHRQ. Improving safety at the point of care. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pips. Accessed January2010.

- ,,,.Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited english proficiency? A systematic review of the literature.Health Serv Res.2007;42(2):727–754.

- ,,.The impact of an enhanced interpreter service intervention on hospital costs and patient satisfaction.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22 Suppl 2:306–311.

- ,,,,.Acute myocardial infarction length of stay and hospital mortality are not associated with language preference.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(2):190–194.

- ,,.A systematic literature review of factors affecting outcome in older medical patients admitted to hospital.Age Ageing.2004;33(2):110–115.

- ,,,,,.Risk factors and prognostic predictors of unexpected intensive care unit admission within 3 days after ED discharge.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25(9):1009–1014.

- ,.Effect of gender, ethnicity, pulmonary disease, and symptom stability on rehospitalization in patients with heart failure.Am J Cardiol.2007;100(7):1139–1144.

- ,,,.Bouncing back: patterns and predictors of complicated transitions 30 days after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke.J Am Geriatr Soc.2007;55(3):365–373.

- ,,,,.Identification of limited English proficient patients in clinical care.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(10):1555–1560.

- ,,,,.Hospital langague services for patients with limited English proficiency: results from a national survey.Health Research October2006.

- ,.Hospitals, Language, and Culture: a Snapshot of the Nation. The Joint Commission and The California Endowment;2007.

- ,,, et al.A randomized controlled trial of interventions to enhance patient‐physician partnership, patient adherence and high blood pressure control among ethnic minorities and poor persons: study protocol NCT00123045.Implement Sci.2009;4:7.

- ,,,,.Interpersonal processes of care and patient satisfaction: do associations differ by race, ethnicity, and language?Health Serv Res.2009;44(4):1326–1344.

- ,,,.Understanding concordance in patient‐physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity.Ann Fam Med.2008;6(3):198–205.

Forty‐five‐million Americans speak a language other than English and more than 19 million of these speak English less than very wellor are limited English proficient (LEP).1 The number of non‐English‐speaking and LEP people in the US has risen in recent decades, presenting a challenge to healthcare systems to provide high‐quality, patient‐centered care for these patients.2

For outpatients, language barriers are a fundamental contributor to gaps in health care. In the clinic setting, patients who do not speak English well have less access to a usual source of care and lower rates of physician visits and preventive services.36 Even when patients with language barriers do have access to care, they have poorer adherence, decreased comprehension of their diagnoses, decreased satisfaction with care, and increased medication complications.710

Few studies, however, have examined how language influences outcomes of hospital care. Compared to English‐speakers, patients who do not speak English well may experience longer lengths of stay,11 and have more adverse events while in the hospital.12 However, these previous studies have not investigated outcomes immediately post‐hospitalization, such as readmission rates and mortality, nor have they directly addressed the interaction between ethnicity and language.

To understand these questions, we analyzed data collected from a university‐based teaching hospital which cares for patients of diverse cultural and language backgrounds. Using these data, we examined how patients' primary language influenced hospital costs, length of stay (LOS), 30‐day readmission, and 30‐day mortality risk.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population and Setting

Our study examined patients admitted to the General Medicine Service at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) between July 1, 2001 and June 30th, 2003, the time period during which UCSF participated in the Multicenter Hospitalist Trial (MHT) a prospective quasi‐randomized trial of hospitalist care for general medicine patients.13, 14

UCSF Moffitt‐Long Hospital is a 400‐bed urban academic medical center which provides services to the City and County of San Francisco, an ethnically and linguistically diverse area. UCSF employs staff language interpreters in Spanish, Chinese and Russian who travel to its many outpatient clinics, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Children's Hospital, as well as to Moffitt‐Long Hospital upon request; phone interpretation is also available when in‐person interpreters are not available, for off hours needs and for less common languages. During the period of this study there were no specific inpatient guidelines in place for use of interpretation services at UCSF, nor were there any specific interventions targeting LEP or non‐English speaking inpatients.

Patients were eligible for the MHT if they were 18 years of age or older and admitted at random to a hospitalist or non‐hospitalist physician (eg, outpatient general internist attending on average 1‐month/year); a minority of patients were cared for directly by their primary care physician while in the hospital, and were excluded. For purposes of our study, which merged MHT data with hospital administrative data on primary language, we further excluded all admissions for patients for whom primary language was missing (n = 5), whose listing was unknown or other language (n = 78), sign language (n = 3) or whose language was listed but was not one of the included languages (n = 258). Included languages were English, Chinese, Russian and Spanish. Because LOS and cost data were skewed, we excluded those admissions with the top 1% longest stays and the top 1% highest cost (n = 176); these exclusions did not alter the proportion of admissions across language and ethnicity. In addition, we excluded 102 admissions that were missing data on cost and 11 with costs <$500 and which were likely to be erroneous. Our research was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Data Sources

We collected administrative data from Transition Systems Inc (TSI, Boston, MA) billing databases at UCSF as part of the MHT. These data include patient demographics, insurance, costs, ICD‐9CM diagnostic codes, admission and discharge dates in Uniform Bill 92 format. Patient mortality information was collected as part of the MHT using the National Death Index.14

Language data were collected from a separate patient‐registration database (STOR) at UCSF. Information on a patient's primary language is entered at the time each patient first registers at UCSF, whether for the index hospitalization or for prior clinic visits, and is based generally on patient self report. As part of our validation step, we cross‐checked 829 STOR language entries against patient reports and found 91% agreement with the majority of the errors classifying non‐English speakers as English‐speakers.

Measures

Predictor

Our primary language variable was derived using language designations collected from patient registration databases described above. Using these data we specified our key language groups as English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), Russian, or Spanish.

Outcomes

LOS and total cost of hospital stay for each hospitalization derived from administrative data sources. Readmissions were identified at the time patients were readmitted to UCSF (eg, flagged in administrative data). Mortality was determined by whether an individual patient with an admission in the database was recorded in the National Death Index as dead within 30‐days of admission.

Covariates

Additional covariates included age at admission, gender, ethnicity as recorded in registration databases (White, African American, Asian, Latino, Other), insurance, principal billing diagnosis, whether or not a patient received intensive care unit (ICU) care, type of admitting attending physician (Hospitalist/non‐Hospitalist), and an administrative Charlson comorbidity score.15 To collapse the principal diagnoses into categories, we used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)'s Clinical Classification System, which allowed us to classify each diagnosis in 1 of 14 generally accepted categories.16

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (STATACorp, Version 9, College Station, TX). We examined descriptive means and proportions for all variables, including sociodemographic, hospitalization, comorbidity and outcome variables. We compared English and non‐English speakers on all covariate and outcome variables using t‐tests for comparison of means and chi‐square for comparison of categorical variables.

It was not possible to fully test the language‐by‐ethnicity interactionwhether or not the impact of language varied by ethnic groupbecause many cells of the joint distribution were very sparse (eg, the sample contained very few non‐English‐speaking African Americans). Therefore, to better understand the influence of English vs. non‐English language usage across different ethnic groups, we created a combined language‐ethnicity predictor variable which categorized each subject first by language and then for the English‐speakers by ethnicity. For example, a Chinese, Spanish or Russian speaker would be categorized as such, and an English‐speaker could fall into the English‐White, English‐African American, English‐Asian or English‐Latino group. This allowed us to test whether there were any differences in language effects across the White, Asian, and Latino ethnicities, and any difference in ethnicity effects among English‐speakers.

Because cost and LOS were skewed, we used negative binomial models for LOS and log transformed costs. We performed a sensitivity analysis testing whether our results were robust to the exclusion of the admissions with the top 1% LOS and top 1% cost. We used logistic regression for the 30‐day readmission and mortality outcomes.

Our primary predictor was the language‐ethnicity variable described above. To determine the independent association between this predictor and our key outcomes, we then built models which included additional potential confounders selected either for face validity or because of observed confounding with other covariates. Our inclusion of potential confounders was limited by the variables available in the administrative database; thus, we were not able to pursue detailed analyses of communication and literacy factors and their interaction with our predictor or their independent impact on outcomes. Models also included a linear spline with a single knot at age 65 years as a further adjustment for age in Medicare recipients.1719 For the 30‐day readmission outcome model, we excluded those admissions for which the patient either died in the hospital or was discharged to hospice care. Within each model we tested the impact of a language barrier using custom contrasts. This allowed us to examine the language‐ethnicity effect aggregating all non‐English speakers compared to all English‐speakers, comparing each non‐English speaking group to all English‐speakers, comparing Chinese speakers to English‐speaking Asians and Spanish speakers to English‐speaking‐Latinos, as well as to test whether the effect of English language is the same across ethnicities.

Results

Admission Characteristics of the Sample

A total of 7023 patients were admitted to the General Medicine service, 5877 (84%) of whom were English‐speakers and 1146 (16%) non‐English‐speakers (Table 1). Overall, half of the admitted patients were women (50%), and the vast majority was insured (93%). The most common principal diagnoses were respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders. Only a small number of non‐English speakers 164 (14%) were recorded in the UCSF Interpreter Services database as having had any interaction with a professional staff interpreter during their hospitalization.

| English (n = 5877) n (%) | Non‐English (n = 1146) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Socio‐economic variables | ||

| Language‐ethnicity | ||

| English | ||

| White | 3066 (52.2) | |

| African American | 1351 (23.0) | |

| Asian | 544 (9.3) | |

| Latino | 298 (5.1) | |

| Other | 618 (10.5) | |

| Chinese speakers | 584 (51.0) | |

| Spanish speakers | 272 (25.3) | |

| Russian speakers | 290 (23.7) | |

| Age mean (SD) (range 18‐105) | 58.8 (20.3) | 72.3 (15.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2967 (50.5) | 514 (44.8) |

| Female | 2910 (49.5) | 632 (55.2) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 2878 (49.0) | 800 (69.8) |

| Medicaid | 1201 (20.4) | 193 (16.8) |

| Commercial | 1358 (23.1) | 106 (9.3) |

| Charity/other | 440 (7.5) | 47 (4.1) |

| Hospitalization variables | ||

| Admitted to ICU | ||

| Yes | 721 (12.3) | 149 (13.0) |

| Attending physician | ||

| Hospitalist | 3950 (67.2) | 781 (68.2) |

| Comorbidity variables | ||

| Principal Diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory disorder | 1061 (18.1) | 225 (19.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 963 (16.4) | 205 (17.9) |

| Circulatory disorder | 613 (10.4) | 140 (12.2) |

| Endocrine/metabolism | 671 (11.4) | 80 (7.0) |

| Injury/poisoning | 475 (8.1) | 64 (5.6) |

| Malignancy | 395 (6.7) | 107 (9.3) |

| Renal/urinary disorder | 383 (6.5) | 108 (9.4) |

| Skin disorder | 278 (4.7) | 28 (2.9) |

| Infection/fatigue NOS | 206 (3.5) | 45 (3.4) |

| Blood disorder (non‐malignant) | 189 (3.2) | 38 (3.3) |

| Musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorder | 164 (2.8) | 33 (2.9) |

| Mental disorder/substance abuse | 171 (2.9) | 7 (0.6) |

| Nervous system/brain infection | 137 (2.3) | 26 (2.3) |

| Unclassified | 171 (2.9) | 40 (3.5) |

| Charlson Index score mean (SD) | 0.97 1.33 | 1.10 1.42 |

Among English speakers, Whites and African Americans were the most common ethnicities; however, more than 500 admissions were categorized as Asian ethnicity, and more than 600 as patients of other ethnicity. Close to 300 admissions were for Latinos. Among non‐English speakers, Chinese speakers had the largest number of admissions (n = 584), while Spanish and Russian speakers had similar numbers (n = 272 and 290 respectively).

Non‐English speakers were older, more likely to be female, more likely to be insured by Medicare, and more likely to have a higher comorbidity index score. While comorbidity scores were similar among non‐English speakers (Chinese 1.13 1.50; Russian 1.09 1.37; Spanish 1.06 1.30), they differed considerably among English speakers (White 0.94 1.29; African American 1.05 1.40; Asian 1.04 1.45; Latino 0.89 1.23; Other 0.91 1.29).

Hospital Outcome by Language‐Ethnicity Group (Table 2)

When aggregated together, non‐English speakers were somewhat more likely to be dead at 30‐days and have lower cost admissions; however, they did not differ from English speakers on LOS or readmission rates. While differences among disaggregated language‐ethnicity groups were not all statistically significant, English‐speaking Whites had the longest LOS (mean = 4.9 days) and highest costs (mean = $10,530). English‐speaking African Americans, Chinese and Spanish speakers had the highest 30‐day readmission rates; whereas, English‐speaking Latinos and Russian speakers had markedly lower 30‐day readmission rates (2.5% and 6.4%, respectively). Chinese speakers had the highest 30‐day mortality, followed by English speaking Whites and Asians.

| Language‐Ethnicity Groups | LOS* Mean #Days (SD) | Cost Mean Cost $ (SD) | 30‐Day Readmission, n (%) | 30‐Day Mortality, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| English speakers (all) | 4.7 (4.5) | 10,035 (15,041) | 648 (11.9) | 613 (10.4) |

| White | 4.9 (5.1) | 10,530 (15,894) | 322 (11.4) | 377 (12.3) |

| African American | 4.5 (4.8) | 9107 (13,314) | 227 (17.5) | 91 (6.7) |

| Asian | 4.3 (4.5) | 9933 (15,607) | 43 (8.8) | 67 (12.3) |

| Latino | 4.6 (4.8) | 9823 (14,113) | 7 (2.5) | 18 (6.0) |

| Other | 4.5 (4.8) | 9662 (14,016) | 49 (8.5) | 60 (9.7) |

| Non‐English speakers (all) | 4.5 (4.5) | 9515 (13,213) | 117 (11.0) | 147 (12.8) |

| Chinese speakers | 4.5 (4.6) | 9505 (12,841) | 69 (12.8) | 85 (14.6) |

| Spanish speakers | 4.5 (4.5) | 9115 (13,846) | 31 (12.0) | 28 (10.3) |

| Russian speakers | 4.7 (4.2) | 9846 (13,360) | 17 (6.4) | 34 (11.7) |

We further investigated differences among English speakers to better understand the very high rate of readmission for African Americans and the very low rate for English‐speaking Latinos. African Americans were on average younger than other English speakers (55 19 years vs. 60 21 years; P < 0.001); but, they had higher comorbidity scores than other English speakers (1.05 1.40 vs. 0.94 1.31; P = 0.008), and were more likely to be admitted for non‐malignant blood disorders (eg, sickle cell disease), endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes mellitus), and circulatory disorders (eg, stroke). In contrast, English‐speaking Latinos were also younger than other English speakers (53 21 years vs. 59 20 years; P < 0.001), but they trended toward lower comorbidity scores (0.87 1.23 vs. 0.97 1.33; P = 0.2), and were more likely to be admitted for gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders, and less likely to be admitted for malignancy and endocrine disorders.

Multivariate Analyses: Association of Aggregated and Disaggregated Language‐Ethnicity Groups With Hospital Outcomes (Table 3)

In multivariate models examining aggregated language‐ethnicity groups, non‐English speakers had a trend toward higher odds of readmission at 30‐days post‐discharge than the English‐speaking group (odds ratio [OR], 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0‐1.7). There were no significant differences for LOS, cost, or 30‐day mortality. Compared to English speakers, Chinese and Spanish speakers had 70% and 50% higher adjusted odds of readmission at 30‐days post‐discharge respectively, while Russian speakers' odds of readmission was not increased. Additionally, Chinese speakers had 7% shorter LOS than English‐speakers. There were no significant differences among any of the language‐ethnicity groups for 30‐day mortality. The increased odds of readmission for Chinese and Spanish speakers compared to English speakers was robust to reinclusion of the admissions with the top 1% LOS and top 1% cost.

| Language Categorization | LOS, % Difference (95% CI) | Total Cost, % Difference (95% CI) | 30‐Day Readmission,* OR (95% CI) | Mortality, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| All English speakers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non‐English speakers | 3.1 (8.7 to 3.1) | 2.5 (8.3 to 2.1) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| All English speakers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Chinese speakers | 7.2 (13.9 to 0) | 5.3 (12.2 to 2.1) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| Spanish speakers | 3.0 (12.6 to 7.6) | 3.0 (12.7 to 7.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) |

| Russian speakers | 1.5 (8.3 to 12.2) | 0.9 (8.9 to 11.8) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) |

Multivariate Analyses: Association of Language for Asians and Latinos, and of Ethnicity for English speakers, With Hospital Outcomes (Table 4)

Both Chinese and Spanish speakers had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission than their English speaking Asian and Latino counterparts. There were no significant differences in LOS, cost, or 30‐day mortality in this within‐ethnicity analysis. Among English speakers, admissions for patients with Asian ethnicity were 15% shorter and resulted in 9% lower costs than for Whites. While LOS and cost were similar for English‐speaking Latino and White admissions, English‐speaking Latinos had markedly lower odds of 30‐day readmission than their White counterparts. Whereas African‐Americans had 6% shorter LOS, 40% higher odds of readmission and 30% lower odds of mortality at 30‐days than English speaking Whites.

| Language‐Ethnicity Comparisons | LOS, % Difference (95% CI) | Total Cost, % Difference (95% CI) | 30‐Day Readmission,* OR (95% CI) | Mortality, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| English speaking Asians | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Chinese speakers | 2.2 (7.4 to 12.7) | 0.3 (9.2 to 10.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| English speaking Latinos | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Spanish speakers | 4.5 (16.8 to 9.5) | 1.2 (14.0 to 13.5) | 5.7 (2.4 to 13.2) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) |

| English‐White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| English‐African American | 6.2 (11.3 to 0.9) | 4.4 (9.6 to 1.1) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

| English‐Asian | 14.6 (20.9 to 7.9) | 8.6 (15.4 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| English‐Latino | 4.5 (13.5 to 5.4) | 5.0 (14.0 to 5.0) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) |

Conclusion/Discussion

Our results indicate that language barriers may contribute to higher readmission rates for non‐English speakers, but that they have less impact on care efficiency or mortality. This finding of an association between language and readmission, without a similar association with efficiency, suggests a potentially communication‐critical step in care.20, 21 Patients with language barriers are more likely to experience adverse events, and those events are often caused by errors in communication.12 It is conceivable that higher readmission risk for Chinese and Spanish speakers in our study was, at least in part, due to gaps in communication that are present in all patient groups, and exacerbated by the presence of a language barrier. This barrier is likely present during hospitalization but magnified at discharge, limiting caregivers' ability to understand patients' needs for home care, while simultaneously limiting patients' understanding of the discharge plan. After discharge, it is also possible that non‐English speakers are less able to communicate their needs as they arise, ormore subtlyfeel less supported by a primarily English speaking healthcare system. As in other clinical arenas,22 it is quite possible that increased access to professional interpreters in the hospital setting, and particularly at the time of discharge, would enhance communication and outcomes for LEP patients. Our interpreter services data showed that the patients in our study had quite limited access to staff professional interpreters.

Our findings differ somewhat from those of John‐Baptiste et al.,11 who found that language barriers contributed to increased LOS for patients with cardiac and major surgical diagnoses. Our study's findings are akin to recent research suggesting that being a monolingual Spanish speaker or receiving interpreter services may not significantly impact LOS or cost of hospitalization,23 and that LOS and in‐hospital mortality do not differ for non‐English speakers and English speakers after acute myocardial infarction.24 These studies, along with our results, suggest that that care efficiency in the hospital may be driven much more by clinical acuity (eg, the need to respond rapidly to urgent clinical signs such as hypotension, fever and respiratory distress) than by adequacy of communication. For example, elderly LEP patients may be even more likely than English speakers to have vigilant family members at the bedside throughout their hospitalization due to their need for communication assistance; these family members can quickly alert hospital staff to concerning changes in the patient's condition.

Our results also suggest the possibility that language and ethnicity are not monolithic concepts, and that even within language and ethnic groups there are potential differences in care pattern. For example, not speaking English may be a surrogate marker for unmeasured factors such as social supports and access to care. Language is intimately associated with culture; it remains plausible that cultural differences between highly acculturated and less acculturated members of a given ethno‐cultural group may have contributed to our observed differences in readmission rates. Differences in culture and associated factors, such as social support or use of multiple hospital systems, may account for lack of higher readmission risk in Russian speakers, while Chinese and Spanish speakers had higher readmission risk.

In addition, our finding that English‐speaking Latinos had lower readmission risk than any other group may be more consistent with their clinical characteristicseg, younger age, fewer comorbiditiesthan with cultural factors. Our finding that African American patients had the highest readmission risk in our hospital was both surprising and concerning. Some of this increased risk may be explained by clinical characteristics, such as higher comorbidities and higher rates of diagnoses leading to frequent admissions (eg, sickle cell disease); however, the reasons for this disparity deserves further investigation.

Our study has limitations. First, our data are administrative, and lack information about patients' educational attainment, social support, acculturation, utilization of other hospital systems, and usual source of care. Despite this, we were able to account for many significant covariates that might contribute to readmission rates, including age, insurance status, gender, comorbidities, and admission to the intensive care unit.2528 Second, our information about patients' English language proficiency is limited. While direct assessments of English proficiency are more accurate ways to determine a patient's ability to communicate with health care providers in English,29 our language validation work conducted in preparation for this study suggests that most of our patients recorded as having a non‐English primary language (87%) also have a low score on a language acculturation scale.

Third, only 14% of our non‐English speaking subjects utilized professional staff interpreters, and we had no information on the use of professional telephonic interpreters, or ad hoc interpretersfamily members, non‐interpreter staff membersand their impact on our results. It is well‐documented that ad hoc interpreters are used frequently in healthcare, particularly in the hospital setting, and thus we can assume this to be true in our study.30, 31 As noted above, it is likely that the advocacy of family members and friends at the bedside helped to minimize potential differences in care efficiency for patients with language barriers. Finally, our study was performed at a single university based hospital and may not produce results which are applicable to other care settings.

Our findings point to several avenues for future research on language barriers and hospitalized patients. First, the field would benefit from an examination of the impact of easy access to professional interpreters during hospitalization on outcomes of hospital care, in particular on readmission rates. Second, there is need for development and assessment of best practices for creating a culture of professional interpreter utilization in the hospital among physicians and nursing staff. Third, investigation of the role of caregiver presence in the hospital room and how this might differ by patient culture, age and language ability may further elucidate some of the differences across language groups observed in our study. Lastly, a more granular investigation of clinician‐patient communication and the importance of interpersonal processes of care on both patient satisfaction and understanding of and adherence to discharge instructions could lead to the development of detailed interventions to enhance this communication and these outcomes as it has done for communication‐sensitive outcomes in the outpatient arena.3234

In summary, our study suggests that higher risk for readmission can be added to the unfortunate list of outcomes which are worsened due to language barriers, pointing to transition from the hospital as a potentially communication‐critical step in care which may be amenable to intervention. Our findings also suggest that this risk can vary even between groups of patients who do not speak English primarily. Whether and to what degree language and communication barriers aloneincluding access to professional interpreters and patient‐centered communicationduring hospitalization, or differences in caregiver social support both during and after hospitalization as well as access to care post‐hospitalization contribute to these findings is a worthy subject of future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Eliseo J. Prez‐Stable for his mentorship on this project.

Forty‐five‐million Americans speak a language other than English and more than 19 million of these speak English less than very wellor are limited English proficient (LEP).1 The number of non‐English‐speaking and LEP people in the US has risen in recent decades, presenting a challenge to healthcare systems to provide high‐quality, patient‐centered care for these patients.2

For outpatients, language barriers are a fundamental contributor to gaps in health care. In the clinic setting, patients who do not speak English well have less access to a usual source of care and lower rates of physician visits and preventive services.36 Even when patients with language barriers do have access to care, they have poorer adherence, decreased comprehension of their diagnoses, decreased satisfaction with care, and increased medication complications.710

Few studies, however, have examined how language influences outcomes of hospital care. Compared to English‐speakers, patients who do not speak English well may experience longer lengths of stay,11 and have more adverse events while in the hospital.12 However, these previous studies have not investigated outcomes immediately post‐hospitalization, such as readmission rates and mortality, nor have they directly addressed the interaction between ethnicity and language.

To understand these questions, we analyzed data collected from a university‐based teaching hospital which cares for patients of diverse cultural and language backgrounds. Using these data, we examined how patients' primary language influenced hospital costs, length of stay (LOS), 30‐day readmission, and 30‐day mortality risk.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population and Setting

Our study examined patients admitted to the General Medicine Service at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) between July 1, 2001 and June 30th, 2003, the time period during which UCSF participated in the Multicenter Hospitalist Trial (MHT) a prospective quasi‐randomized trial of hospitalist care for general medicine patients.13, 14

UCSF Moffitt‐Long Hospital is a 400‐bed urban academic medical center which provides services to the City and County of San Francisco, an ethnically and linguistically diverse area. UCSF employs staff language interpreters in Spanish, Chinese and Russian who travel to its many outpatient clinics, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Children's Hospital, as well as to Moffitt‐Long Hospital upon request; phone interpretation is also available when in‐person interpreters are not available, for off hours needs and for less common languages. During the period of this study there were no specific inpatient guidelines in place for use of interpretation services at UCSF, nor were there any specific interventions targeting LEP or non‐English speaking inpatients.

Patients were eligible for the MHT if they were 18 years of age or older and admitted at random to a hospitalist or non‐hospitalist physician (eg, outpatient general internist attending on average 1‐month/year); a minority of patients were cared for directly by their primary care physician while in the hospital, and were excluded. For purposes of our study, which merged MHT data with hospital administrative data on primary language, we further excluded all admissions for patients for whom primary language was missing (n = 5), whose listing was unknown or other language (n = 78), sign language (n = 3) or whose language was listed but was not one of the included languages (n = 258). Included languages were English, Chinese, Russian and Spanish. Because LOS and cost data were skewed, we excluded those admissions with the top 1% longest stays and the top 1% highest cost (n = 176); these exclusions did not alter the proportion of admissions across language and ethnicity. In addition, we excluded 102 admissions that were missing data on cost and 11 with costs <$500 and which were likely to be erroneous. Our research was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Data Sources

We collected administrative data from Transition Systems Inc (TSI, Boston, MA) billing databases at UCSF as part of the MHT. These data include patient demographics, insurance, costs, ICD‐9CM diagnostic codes, admission and discharge dates in Uniform Bill 92 format. Patient mortality information was collected as part of the MHT using the National Death Index.14

Language data were collected from a separate patient‐registration database (STOR) at UCSF. Information on a patient's primary language is entered at the time each patient first registers at UCSF, whether for the index hospitalization or for prior clinic visits, and is based generally on patient self report. As part of our validation step, we cross‐checked 829 STOR language entries against patient reports and found 91% agreement with the majority of the errors classifying non‐English speakers as English‐speakers.

Measures

Predictor

Our primary language variable was derived using language designations collected from patient registration databases described above. Using these data we specified our key language groups as English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), Russian, or Spanish.

Outcomes

LOS and total cost of hospital stay for each hospitalization derived from administrative data sources. Readmissions were identified at the time patients were readmitted to UCSF (eg, flagged in administrative data). Mortality was determined by whether an individual patient with an admission in the database was recorded in the National Death Index as dead within 30‐days of admission.

Covariates

Additional covariates included age at admission, gender, ethnicity as recorded in registration databases (White, African American, Asian, Latino, Other), insurance, principal billing diagnosis, whether or not a patient received intensive care unit (ICU) care, type of admitting attending physician (Hospitalist/non‐Hospitalist), and an administrative Charlson comorbidity score.15 To collapse the principal diagnoses into categories, we used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)'s Clinical Classification System, which allowed us to classify each diagnosis in 1 of 14 generally accepted categories.16

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (STATACorp, Version 9, College Station, TX). We examined descriptive means and proportions for all variables, including sociodemographic, hospitalization, comorbidity and outcome variables. We compared English and non‐English speakers on all covariate and outcome variables using t‐tests for comparison of means and chi‐square for comparison of categorical variables.

It was not possible to fully test the language‐by‐ethnicity interactionwhether or not the impact of language varied by ethnic groupbecause many cells of the joint distribution were very sparse (eg, the sample contained very few non‐English‐speaking African Americans). Therefore, to better understand the influence of English vs. non‐English language usage across different ethnic groups, we created a combined language‐ethnicity predictor variable which categorized each subject first by language and then for the English‐speakers by ethnicity. For example, a Chinese, Spanish or Russian speaker would be categorized as such, and an English‐speaker could fall into the English‐White, English‐African American, English‐Asian or English‐Latino group. This allowed us to test whether there were any differences in language effects across the White, Asian, and Latino ethnicities, and any difference in ethnicity effects among English‐speakers.

Because cost and LOS were skewed, we used negative binomial models for LOS and log transformed costs. We performed a sensitivity analysis testing whether our results were robust to the exclusion of the admissions with the top 1% LOS and top 1% cost. We used logistic regression for the 30‐day readmission and mortality outcomes.

Our primary predictor was the language‐ethnicity variable described above. To determine the independent association between this predictor and our key outcomes, we then built models which included additional potential confounders selected either for face validity or because of observed confounding with other covariates. Our inclusion of potential confounders was limited by the variables available in the administrative database; thus, we were not able to pursue detailed analyses of communication and literacy factors and their interaction with our predictor or their independent impact on outcomes. Models also included a linear spline with a single knot at age 65 years as a further adjustment for age in Medicare recipients.1719 For the 30‐day readmission outcome model, we excluded those admissions for which the patient either died in the hospital or was discharged to hospice care. Within each model we tested the impact of a language barrier using custom contrasts. This allowed us to examine the language‐ethnicity effect aggregating all non‐English speakers compared to all English‐speakers, comparing each non‐English speaking group to all English‐speakers, comparing Chinese speakers to English‐speaking Asians and Spanish speakers to English‐speaking‐Latinos, as well as to test whether the effect of English language is the same across ethnicities.

Results

Admission Characteristics of the Sample

A total of 7023 patients were admitted to the General Medicine service, 5877 (84%) of whom were English‐speakers and 1146 (16%) non‐English‐speakers (Table 1). Overall, half of the admitted patients were women (50%), and the vast majority was insured (93%). The most common principal diagnoses were respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders. Only a small number of non‐English speakers 164 (14%) were recorded in the UCSF Interpreter Services database as having had any interaction with a professional staff interpreter during their hospitalization.

| English (n = 5877) n (%) | Non‐English (n = 1146) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Socio‐economic variables | ||

| Language‐ethnicity | ||

| English | ||

| White | 3066 (52.2) | |

| African American | 1351 (23.0) | |

| Asian | 544 (9.3) | |

| Latino | 298 (5.1) | |

| Other | 618 (10.5) | |

| Chinese speakers | 584 (51.0) | |

| Spanish speakers | 272 (25.3) | |

| Russian speakers | 290 (23.7) | |

| Age mean (SD) (range 18‐105) | 58.8 (20.3) | 72.3 (15.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2967 (50.5) | 514 (44.8) |

| Female | 2910 (49.5) | 632 (55.2) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 2878 (49.0) | 800 (69.8) |

| Medicaid | 1201 (20.4) | 193 (16.8) |

| Commercial | 1358 (23.1) | 106 (9.3) |

| Charity/other | 440 (7.5) | 47 (4.1) |

| Hospitalization variables | ||

| Admitted to ICU | ||

| Yes | 721 (12.3) | 149 (13.0) |

| Attending physician | ||

| Hospitalist | 3950 (67.2) | 781 (68.2) |

| Comorbidity variables | ||

| Principal Diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory disorder | 1061 (18.1) | 225 (19.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 963 (16.4) | 205 (17.9) |

| Circulatory disorder | 613 (10.4) | 140 (12.2) |

| Endocrine/metabolism | 671 (11.4) | 80 (7.0) |

| Injury/poisoning | 475 (8.1) | 64 (5.6) |

| Malignancy | 395 (6.7) | 107 (9.3) |

| Renal/urinary disorder | 383 (6.5) | 108 (9.4) |

| Skin disorder | 278 (4.7) | 28 (2.9) |

| Infection/fatigue NOS | 206 (3.5) | 45 (3.4) |

| Blood disorder (non‐malignant) | 189 (3.2) | 38 (3.3) |

| Musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorder | 164 (2.8) | 33 (2.9) |

| Mental disorder/substance abuse | 171 (2.9) | 7 (0.6) |

| Nervous system/brain infection | 137 (2.3) | 26 (2.3) |

| Unclassified | 171 (2.9) | 40 (3.5) |

| Charlson Index score mean (SD) | 0.97 1.33 | 1.10 1.42 |

Among English speakers, Whites and African Americans were the most common ethnicities; however, more than 500 admissions were categorized as Asian ethnicity, and more than 600 as patients of other ethnicity. Close to 300 admissions were for Latinos. Among non‐English speakers, Chinese speakers had the largest number of admissions (n = 584), while Spanish and Russian speakers had similar numbers (n = 272 and 290 respectively).

Non‐English speakers were older, more likely to be female, more likely to be insured by Medicare, and more likely to have a higher comorbidity index score. While comorbidity scores were similar among non‐English speakers (Chinese 1.13 1.50; Russian 1.09 1.37; Spanish 1.06 1.30), they differed considerably among English speakers (White 0.94 1.29; African American 1.05 1.40; Asian 1.04 1.45; Latino 0.89 1.23; Other 0.91 1.29).

Hospital Outcome by Language‐Ethnicity Group (Table 2)

When aggregated together, non‐English speakers were somewhat more likely to be dead at 30‐days and have lower cost admissions; however, they did not differ from English speakers on LOS or readmission rates. While differences among disaggregated language‐ethnicity groups were not all statistically significant, English‐speaking Whites had the longest LOS (mean = 4.9 days) and highest costs (mean = $10,530). English‐speaking African Americans, Chinese and Spanish speakers had the highest 30‐day readmission rates; whereas, English‐speaking Latinos and Russian speakers had markedly lower 30‐day readmission rates (2.5% and 6.4%, respectively). Chinese speakers had the highest 30‐day mortality, followed by English speaking Whites and Asians.

| Language‐Ethnicity Groups | LOS* Mean #Days (SD) | Cost Mean Cost $ (SD) | 30‐Day Readmission, n (%) | 30‐Day Mortality, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| English speakers (all) | 4.7 (4.5) | 10,035 (15,041) | 648 (11.9) | 613 (10.4) |

| White | 4.9 (5.1) | 10,530 (15,894) | 322 (11.4) | 377 (12.3) |

| African American | 4.5 (4.8) | 9107 (13,314) | 227 (17.5) | 91 (6.7) |

| Asian | 4.3 (4.5) | 9933 (15,607) | 43 (8.8) | 67 (12.3) |

| Latino | 4.6 (4.8) | 9823 (14,113) | 7 (2.5) | 18 (6.0) |

| Other | 4.5 (4.8) | 9662 (14,016) | 49 (8.5) | 60 (9.7) |

| Non‐English speakers (all) | 4.5 (4.5) | 9515 (13,213) | 117 (11.0) | 147 (12.8) |

| Chinese speakers | 4.5 (4.6) | 9505 (12,841) | 69 (12.8) | 85 (14.6) |

| Spanish speakers | 4.5 (4.5) | 9115 (13,846) | 31 (12.0) | 28 (10.3) |

| Russian speakers | 4.7 (4.2) | 9846 (13,360) | 17 (6.4) | 34 (11.7) |

We further investigated differences among English speakers to better understand the very high rate of readmission for African Americans and the very low rate for English‐speaking Latinos. African Americans were on average younger than other English speakers (55 19 years vs. 60 21 years; P < 0.001); but, they had higher comorbidity scores than other English speakers (1.05 1.40 vs. 0.94 1.31; P = 0.008), and were more likely to be admitted for non‐malignant blood disorders (eg, sickle cell disease), endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes mellitus), and circulatory disorders (eg, stroke). In contrast, English‐speaking Latinos were also younger than other English speakers (53 21 years vs. 59 20 years; P < 0.001), but they trended toward lower comorbidity scores (0.87 1.23 vs. 0.97 1.33; P = 0.2), and were more likely to be admitted for gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders, and less likely to be admitted for malignancy and endocrine disorders.

Multivariate Analyses: Association of Aggregated and Disaggregated Language‐Ethnicity Groups With Hospital Outcomes (Table 3)