User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Children and COVID: New cases rise to winter levels

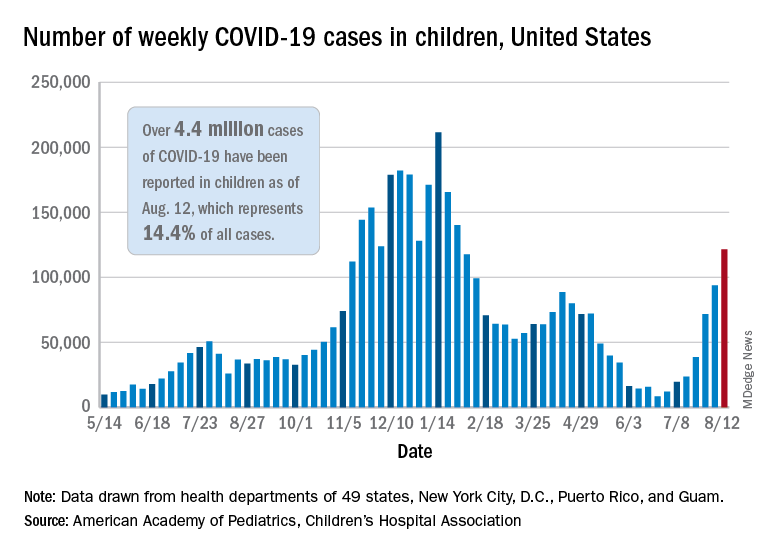

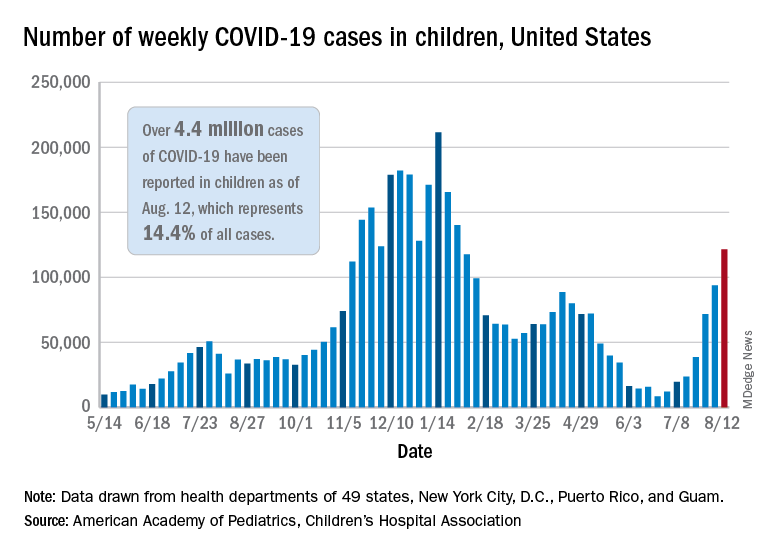

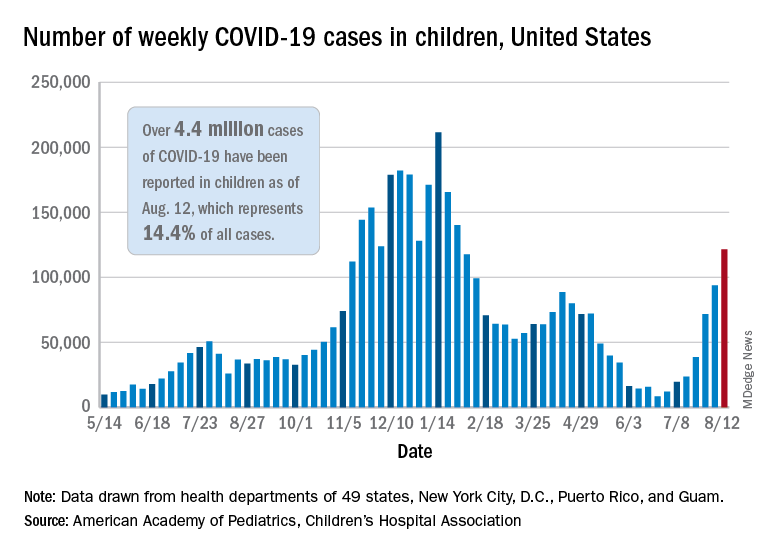

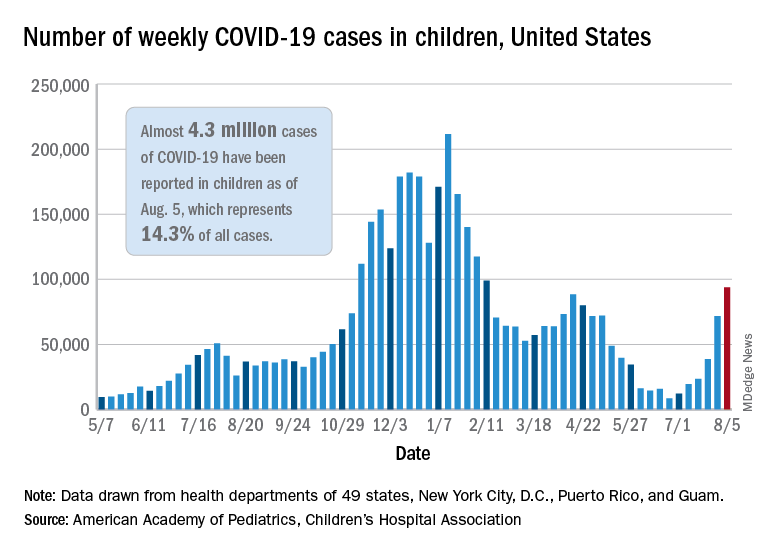

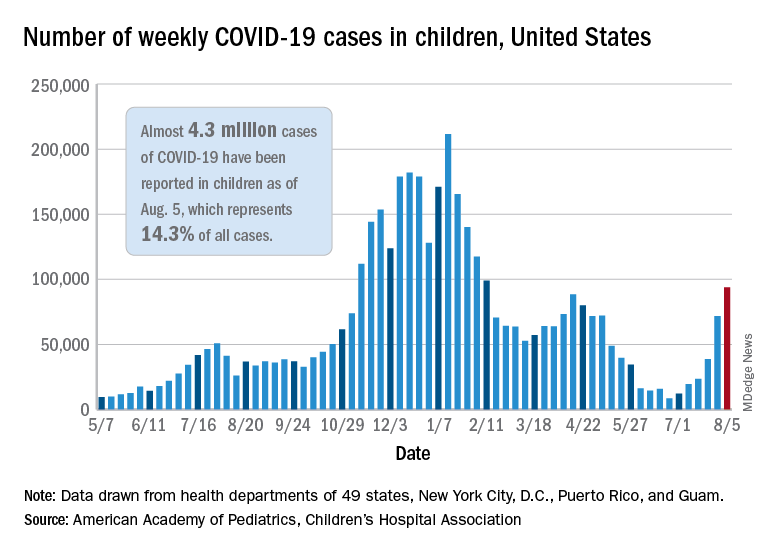

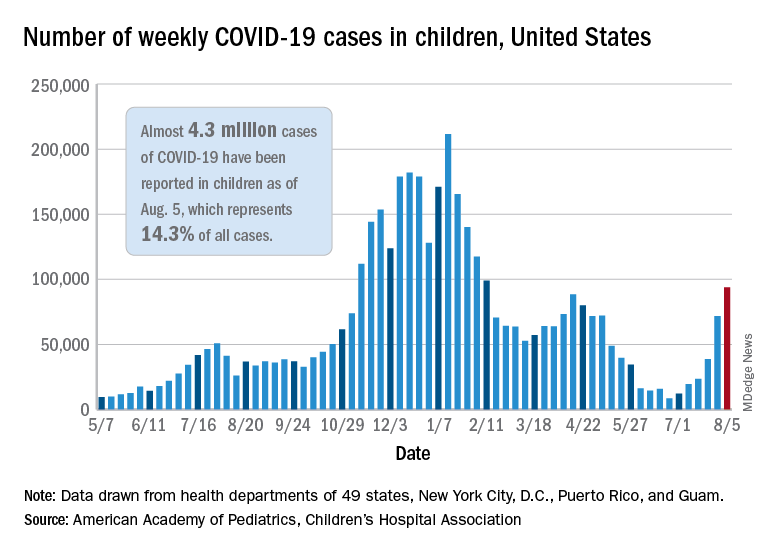

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

Heparin’s COVID-19 benefit greatest in moderately ill patients

Critically ill derive no benefit

Therapeutic levels of heparin can have widely varying effects on COVID-19 patients depending on the severity of their disease, according to a multiplatform clinical trial that analyzed patient data from three international trials.

COVID-19 patients in the ICU, or at least receiving ICU-level care, derived no benefit from anticoagulation with heparin, while non–critically ill COVID-19 patients – those who were hospitalized but not receiving ICU-level care – on the same anticoagulation were less likely to progress to need respiratory or cardiovascular organ support despite a slightly heightened risk of bleeding events.

Reporting in two articles published online in the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of three international trials combined their data into one multiplatform trial that makes a strong case for prescribing therapeutic levels of heparin in hospitalized patients not receiving ICU-level care were non–critically ill and critically ill.

“I think this is going to be a game changer,” said Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, ACTIV-4a co–principal investigator and co–first author of the study of non–critically ill patients. “I think that using therapeutic-dose anticoagulation should improve outcomes in the tens of thousands of patients worldwide. I hope our data can have a global impact.”

Outcomes based on disease severity

The multiplatform trial analyzed data from the Antithrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19 (ATTACC); A Multicenter, Adaptive, Randomized Controlled Platform Trial of the Safety and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Strategies in Hospitalized Adults with COVID-19 (ACTIV-4a); and Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP).

The trial evaluated 2,219 non–critically ill hospitalized patients, 1,181 of whom were randomized to therapeutic-dose anticoagulation; and 1,098 critically ill patients, 534 of whom were prescribed therapeutic levels of heparin.

In the critically ill patients, those on heparin were no more likely to get discharged or spend fewer days on respiratory or CV organ support – oxygen, mechanical ventilation, life support, vasopressors or inotropes – than were those on usual-care thromboprophylaxis. The investigators stopped the trial in both patient populations: in critically ill patients when it became obvious therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was having no impact; and in moderately ill patients when the trial met the prespecified criteria for the superiority of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation.

ICU patients on therapeutic-level heparin spent an average of 1 day free of organ support vs. 4 for patients on usual-care prophylactic antithrombotic drugs. The percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge was similar in the therapeutic-level and usual-care critically ill patients: 62.7% and 64.5%, respectively. Major bleeding occurred in 3.8% and 2.8%, respectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both patient groups.

However, in non–critically ill patients, therapeutic levels of heparin resulted in a marked improvement in outcomes. The researchers estimated that, for every 1,000 hospitalized patients with what they labeled moderate disease, an initial treatment with therapeutic-dose heparin resulted in 40 additional patients surviving compared to usual-care thromboprophylaxis.

The percentages of patients not needing organ support before hospital discharge was 80.2% on therapeutic-dose heparin and 76.4% on usual-care therapy. In terms of adjusted odds ratio, the anticoagulation group had a 27% improved chance of not needing daily organ support.

Those improvements came with an additional seven major bleeding events per 1,000 patients. That broke down to a rate of 1.9% in the therapeutic-dose and 0.9% in the usual-care patients.

As the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreads, Patrick R. Lawler, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the ATTACC trial, said there’s no reason these findings shouldn’t apply for all variants of the disease.

Dr. Lawler, a physician-scientist at Peter Munk Cardiac Centre at Toronto General Hospital, noted that the multiplatform study did not account for disease variant. “Ongoing clinical trials are tracking the variant patients have or the variants that are most prevalent in an area at that time,” he said. “It may be easier in future trials to look at that question.”

Explaining heparin’s varying effects

The study did not specifically sort out why moderately ill patients fared better on heparin than their critically ill counterparts, but Dr. Lawler speculated on possible reasons. “One might be that the extent of illness severity is too extreme in the ICU-level population for heparin to have a beneficial extent,” he said.

He acknowledged that higher rates of macrovascular thrombosis, such as venous thromboembolism, in ICU patients would suggest that heparin would have a greater beneficial effect, but, he added, “it may also suggest how advanced that process is, and perhaps heparin is not adequate to reverse the course at that point given relatively extensive thrombosis and associate organ failure.”

As clinicians have gained experience dealing with COVID-19, they’ve learned that infected patients carry a high burden of macro- and microthrombosis, Dr. Berger said, which may explain why critically ill patients didn’t respond as well to therapeutic levels of heparin. “I think the cat is out of the bag; patients who are severe are too ill to benefit,” he said. “I would think there’s too much microthrombosis that is already in their bodies.”

However, this doesn’t completely rule out therapeutic levels of heparin in critically ill COVID-19 patients. There are some scenarios where it’s needed, said Dr. Berger, associate professor of medicine and surgery and director of the Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease at New York University Langone Health. “Anyone who has a known clot already, like a known macrothrombosis in their leg or lung, needs to be on full-dose heparin,” he said.

That rationale can help reconcile the different outcomes in the critically and non–critically ill COVID-19 patients, wrote Hugo ten Cate, MD, PhD, of Maastricht University in the Netherlands, wrote in an accompanying editorial. But differences in the study populations may also explain the divergent outcomes, Dr. ten Cate noted.

The studies suggest that critically ill patients may need hon-heparin antithrombotic approaches “or even profibrinolytic strategies,” Dr. Cate wrote, and that the safety and effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis “remains an important question.” Nonetheless, he added, treating physicians must deal with the bleeding risk when using heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin in moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Deepak L. Bhatt MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, said in an interview that reconciling the two studies was “a bit challenging,” because effective therapies tend to have a greater impact in sicker patients.

“Of course, with antithrombotic therapies, bleeding side effects can sometimes overwhelm benefits in patients who are at high risk of both bleeding and ischemic complications, though that does not seem to be the explanation here,” Dr. Bhatt said. “I do think we need more data to clarify exactly which COVID patients benefit from various antithrombotic regimens, and fortunately, there are other ongoing studies, some of which will report relatively soon.”

He concurred with Dr. Berger that patients who need anticoagulation should receive it “apart from their COVID status,” Dr. Bhatt said. “Sick, hospitalized patients with or without COVID should receive appropriate prophylactic doses of anticoagulation.” However, he added, “Whether we should routinely go beyond that in COVID-positive inpatients, I think we need more data.”

The ATTACC platform received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and several other research foundations. The ACTIV-4a platform received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. REMAP-CAP received funding from the European Union and several international research foundations, as well as Amgen and Eisai.

Dr. Lawler had no relationships to disclose. Dr. Berger disclosed receiving grants from the NHLBI, and financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. ten Cate reported relationships with Alveron, Coagulation Profile, Portola/Alexion, Bayer, Pfizer, Stago, Leo Pharma, Daiichi, and Gilead/Galapagos. Dr. Bhatt is chair of the data safety and monitoring board of the FREEDOM COVID anticoagulation clinical trial.

Critically ill derive no benefit

Critically ill derive no benefit

Therapeutic levels of heparin can have widely varying effects on COVID-19 patients depending on the severity of their disease, according to a multiplatform clinical trial that analyzed patient data from three international trials.

COVID-19 patients in the ICU, or at least receiving ICU-level care, derived no benefit from anticoagulation with heparin, while non–critically ill COVID-19 patients – those who were hospitalized but not receiving ICU-level care – on the same anticoagulation were less likely to progress to need respiratory or cardiovascular organ support despite a slightly heightened risk of bleeding events.

Reporting in two articles published online in the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of three international trials combined their data into one multiplatform trial that makes a strong case for prescribing therapeutic levels of heparin in hospitalized patients not receiving ICU-level care were non–critically ill and critically ill.

“I think this is going to be a game changer,” said Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, ACTIV-4a co–principal investigator and co–first author of the study of non–critically ill patients. “I think that using therapeutic-dose anticoagulation should improve outcomes in the tens of thousands of patients worldwide. I hope our data can have a global impact.”

Outcomes based on disease severity

The multiplatform trial analyzed data from the Antithrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19 (ATTACC); A Multicenter, Adaptive, Randomized Controlled Platform Trial of the Safety and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Strategies in Hospitalized Adults with COVID-19 (ACTIV-4a); and Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP).

The trial evaluated 2,219 non–critically ill hospitalized patients, 1,181 of whom were randomized to therapeutic-dose anticoagulation; and 1,098 critically ill patients, 534 of whom were prescribed therapeutic levels of heparin.

In the critically ill patients, those on heparin were no more likely to get discharged or spend fewer days on respiratory or CV organ support – oxygen, mechanical ventilation, life support, vasopressors or inotropes – than were those on usual-care thromboprophylaxis. The investigators stopped the trial in both patient populations: in critically ill patients when it became obvious therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was having no impact; and in moderately ill patients when the trial met the prespecified criteria for the superiority of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation.

ICU patients on therapeutic-level heparin spent an average of 1 day free of organ support vs. 4 for patients on usual-care prophylactic antithrombotic drugs. The percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge was similar in the therapeutic-level and usual-care critically ill patients: 62.7% and 64.5%, respectively. Major bleeding occurred in 3.8% and 2.8%, respectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both patient groups.

However, in non–critically ill patients, therapeutic levels of heparin resulted in a marked improvement in outcomes. The researchers estimated that, for every 1,000 hospitalized patients with what they labeled moderate disease, an initial treatment with therapeutic-dose heparin resulted in 40 additional patients surviving compared to usual-care thromboprophylaxis.

The percentages of patients not needing organ support before hospital discharge was 80.2% on therapeutic-dose heparin and 76.4% on usual-care therapy. In terms of adjusted odds ratio, the anticoagulation group had a 27% improved chance of not needing daily organ support.

Those improvements came with an additional seven major bleeding events per 1,000 patients. That broke down to a rate of 1.9% in the therapeutic-dose and 0.9% in the usual-care patients.

As the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreads, Patrick R. Lawler, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the ATTACC trial, said there’s no reason these findings shouldn’t apply for all variants of the disease.

Dr. Lawler, a physician-scientist at Peter Munk Cardiac Centre at Toronto General Hospital, noted that the multiplatform study did not account for disease variant. “Ongoing clinical trials are tracking the variant patients have or the variants that are most prevalent in an area at that time,” he said. “It may be easier in future trials to look at that question.”

Explaining heparin’s varying effects

The study did not specifically sort out why moderately ill patients fared better on heparin than their critically ill counterparts, but Dr. Lawler speculated on possible reasons. “One might be that the extent of illness severity is too extreme in the ICU-level population for heparin to have a beneficial extent,” he said.

He acknowledged that higher rates of macrovascular thrombosis, such as venous thromboembolism, in ICU patients would suggest that heparin would have a greater beneficial effect, but, he added, “it may also suggest how advanced that process is, and perhaps heparin is not adequate to reverse the course at that point given relatively extensive thrombosis and associate organ failure.”

As clinicians have gained experience dealing with COVID-19, they’ve learned that infected patients carry a high burden of macro- and microthrombosis, Dr. Berger said, which may explain why critically ill patients didn’t respond as well to therapeutic levels of heparin. “I think the cat is out of the bag; patients who are severe are too ill to benefit,” he said. “I would think there’s too much microthrombosis that is already in their bodies.”

However, this doesn’t completely rule out therapeutic levels of heparin in critically ill COVID-19 patients. There are some scenarios where it’s needed, said Dr. Berger, associate professor of medicine and surgery and director of the Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease at New York University Langone Health. “Anyone who has a known clot already, like a known macrothrombosis in their leg or lung, needs to be on full-dose heparin,” he said.

That rationale can help reconcile the different outcomes in the critically and non–critically ill COVID-19 patients, wrote Hugo ten Cate, MD, PhD, of Maastricht University in the Netherlands, wrote in an accompanying editorial. But differences in the study populations may also explain the divergent outcomes, Dr. ten Cate noted.

The studies suggest that critically ill patients may need hon-heparin antithrombotic approaches “or even profibrinolytic strategies,” Dr. Cate wrote, and that the safety and effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis “remains an important question.” Nonetheless, he added, treating physicians must deal with the bleeding risk when using heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin in moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Deepak L. Bhatt MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, said in an interview that reconciling the two studies was “a bit challenging,” because effective therapies tend to have a greater impact in sicker patients.

“Of course, with antithrombotic therapies, bleeding side effects can sometimes overwhelm benefits in patients who are at high risk of both bleeding and ischemic complications, though that does not seem to be the explanation here,” Dr. Bhatt said. “I do think we need more data to clarify exactly which COVID patients benefit from various antithrombotic regimens, and fortunately, there are other ongoing studies, some of which will report relatively soon.”

He concurred with Dr. Berger that patients who need anticoagulation should receive it “apart from their COVID status,” Dr. Bhatt said. “Sick, hospitalized patients with or without COVID should receive appropriate prophylactic doses of anticoagulation.” However, he added, “Whether we should routinely go beyond that in COVID-positive inpatients, I think we need more data.”

The ATTACC platform received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and several other research foundations. The ACTIV-4a platform received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. REMAP-CAP received funding from the European Union and several international research foundations, as well as Amgen and Eisai.

Dr. Lawler had no relationships to disclose. Dr. Berger disclosed receiving grants from the NHLBI, and financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. ten Cate reported relationships with Alveron, Coagulation Profile, Portola/Alexion, Bayer, Pfizer, Stago, Leo Pharma, Daiichi, and Gilead/Galapagos. Dr. Bhatt is chair of the data safety and monitoring board of the FREEDOM COVID anticoagulation clinical trial.

Therapeutic levels of heparin can have widely varying effects on COVID-19 patients depending on the severity of their disease, according to a multiplatform clinical trial that analyzed patient data from three international trials.

COVID-19 patients in the ICU, or at least receiving ICU-level care, derived no benefit from anticoagulation with heparin, while non–critically ill COVID-19 patients – those who were hospitalized but not receiving ICU-level care – on the same anticoagulation were less likely to progress to need respiratory or cardiovascular organ support despite a slightly heightened risk of bleeding events.

Reporting in two articles published online in the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of three international trials combined their data into one multiplatform trial that makes a strong case for prescribing therapeutic levels of heparin in hospitalized patients not receiving ICU-level care were non–critically ill and critically ill.

“I think this is going to be a game changer,” said Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, ACTIV-4a co–principal investigator and co–first author of the study of non–critically ill patients. “I think that using therapeutic-dose anticoagulation should improve outcomes in the tens of thousands of patients worldwide. I hope our data can have a global impact.”

Outcomes based on disease severity

The multiplatform trial analyzed data from the Antithrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19 (ATTACC); A Multicenter, Adaptive, Randomized Controlled Platform Trial of the Safety and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Strategies in Hospitalized Adults with COVID-19 (ACTIV-4a); and Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP).

The trial evaluated 2,219 non–critically ill hospitalized patients, 1,181 of whom were randomized to therapeutic-dose anticoagulation; and 1,098 critically ill patients, 534 of whom were prescribed therapeutic levels of heparin.

In the critically ill patients, those on heparin were no more likely to get discharged or spend fewer days on respiratory or CV organ support – oxygen, mechanical ventilation, life support, vasopressors or inotropes – than were those on usual-care thromboprophylaxis. The investigators stopped the trial in both patient populations: in critically ill patients when it became obvious therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was having no impact; and in moderately ill patients when the trial met the prespecified criteria for the superiority of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation.

ICU patients on therapeutic-level heparin spent an average of 1 day free of organ support vs. 4 for patients on usual-care prophylactic antithrombotic drugs. The percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge was similar in the therapeutic-level and usual-care critically ill patients: 62.7% and 64.5%, respectively. Major bleeding occurred in 3.8% and 2.8%, respectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both patient groups.

However, in non–critically ill patients, therapeutic levels of heparin resulted in a marked improvement in outcomes. The researchers estimated that, for every 1,000 hospitalized patients with what they labeled moderate disease, an initial treatment with therapeutic-dose heparin resulted in 40 additional patients surviving compared to usual-care thromboprophylaxis.

The percentages of patients not needing organ support before hospital discharge was 80.2% on therapeutic-dose heparin and 76.4% on usual-care therapy. In terms of adjusted odds ratio, the anticoagulation group had a 27% improved chance of not needing daily organ support.

Those improvements came with an additional seven major bleeding events per 1,000 patients. That broke down to a rate of 1.9% in the therapeutic-dose and 0.9% in the usual-care patients.

As the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreads, Patrick R. Lawler, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the ATTACC trial, said there’s no reason these findings shouldn’t apply for all variants of the disease.

Dr. Lawler, a physician-scientist at Peter Munk Cardiac Centre at Toronto General Hospital, noted that the multiplatform study did not account for disease variant. “Ongoing clinical trials are tracking the variant patients have or the variants that are most prevalent in an area at that time,” he said. “It may be easier in future trials to look at that question.”

Explaining heparin’s varying effects

The study did not specifically sort out why moderately ill patients fared better on heparin than their critically ill counterparts, but Dr. Lawler speculated on possible reasons. “One might be that the extent of illness severity is too extreme in the ICU-level population for heparin to have a beneficial extent,” he said.

He acknowledged that higher rates of macrovascular thrombosis, such as venous thromboembolism, in ICU patients would suggest that heparin would have a greater beneficial effect, but, he added, “it may also suggest how advanced that process is, and perhaps heparin is not adequate to reverse the course at that point given relatively extensive thrombosis and associate organ failure.”

As clinicians have gained experience dealing with COVID-19, they’ve learned that infected patients carry a high burden of macro- and microthrombosis, Dr. Berger said, which may explain why critically ill patients didn’t respond as well to therapeutic levels of heparin. “I think the cat is out of the bag; patients who are severe are too ill to benefit,” he said. “I would think there’s too much microthrombosis that is already in their bodies.”

However, this doesn’t completely rule out therapeutic levels of heparin in critically ill COVID-19 patients. There are some scenarios where it’s needed, said Dr. Berger, associate professor of medicine and surgery and director of the Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease at New York University Langone Health. “Anyone who has a known clot already, like a known macrothrombosis in their leg or lung, needs to be on full-dose heparin,” he said.

That rationale can help reconcile the different outcomes in the critically and non–critically ill COVID-19 patients, wrote Hugo ten Cate, MD, PhD, of Maastricht University in the Netherlands, wrote in an accompanying editorial. But differences in the study populations may also explain the divergent outcomes, Dr. ten Cate noted.

The studies suggest that critically ill patients may need hon-heparin antithrombotic approaches “or even profibrinolytic strategies,” Dr. Cate wrote, and that the safety and effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis “remains an important question.” Nonetheless, he added, treating physicians must deal with the bleeding risk when using heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin in moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Deepak L. Bhatt MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, said in an interview that reconciling the two studies was “a bit challenging,” because effective therapies tend to have a greater impact in sicker patients.

“Of course, with antithrombotic therapies, bleeding side effects can sometimes overwhelm benefits in patients who are at high risk of both bleeding and ischemic complications, though that does not seem to be the explanation here,” Dr. Bhatt said. “I do think we need more data to clarify exactly which COVID patients benefit from various antithrombotic regimens, and fortunately, there are other ongoing studies, some of which will report relatively soon.”

He concurred with Dr. Berger that patients who need anticoagulation should receive it “apart from their COVID status,” Dr. Bhatt said. “Sick, hospitalized patients with or without COVID should receive appropriate prophylactic doses of anticoagulation.” However, he added, “Whether we should routinely go beyond that in COVID-positive inpatients, I think we need more data.”

The ATTACC platform received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and several other research foundations. The ACTIV-4a platform received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. REMAP-CAP received funding from the European Union and several international research foundations, as well as Amgen and Eisai.

Dr. Lawler had no relationships to disclose. Dr. Berger disclosed receiving grants from the NHLBI, and financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. ten Cate reported relationships with Alveron, Coagulation Profile, Portola/Alexion, Bayer, Pfizer, Stago, Leo Pharma, Daiichi, and Gilead/Galapagos. Dr. Bhatt is chair of the data safety and monitoring board of the FREEDOM COVID anticoagulation clinical trial.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

FDA authorizes booster shot for immunocompromised Americans

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospitals struggle to find nurses, beds, even oxygen as Delta surges

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”

Compounding the staffing problems, about half of hospital workers in Alabama are still unvaccinated. Dr. Williamson says they’re now starting to see these unvaccinated health care workers come down with COVID too. He says that will exacerbate their surge even further as health care workers become too sick to help care for patients and some will end up needing hospital beds themselves.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70 hospital employees and another 20 clinic employees are now being quarantined or have COVID, Dr. Jones said.

“The situation is bleak for Mississippi hospitals,” said Timothy Moore, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association. He said he doesn’t expect it to get better anytime soon.

Mississippi has more patients hospitalized now than at any other point in the pandemic, said Thomas Dobbs, MD, MPH, the state epidemiologist.

“If we look at the rapidity of this rise, it’s really kind of terrifying and awe-inspiring,” Dr. Dobbs said in a news conference Aug. 11.

Schools are just starting back, and, in many parts of the South, districts are operating under a patchwork of policies – some require masks, while others have made them voluntary. Physicians say they are bracing for what these half measures could mean for pediatric cases and community transmission.

The only sure way for people to help themselves and their hospitals and schools, experts said, is vaccination.

“State data show that in this latest COVID surge, 97% of new COVID-19 infections, 89% of hospitalizations, and 82% of deaths occur in unvaccinated residents,” Mr. Moore said.

“To relieve pressure on hospitals, we need Mississippians – even those who have previously had COVID – to get vaccinated and wear a mask in public. The Delta variant is highly contagious and we need to do all we can to stop the spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”

Compounding the staffing problems, about half of hospital workers in Alabama are still unvaccinated. Dr. Williamson says they’re now starting to see these unvaccinated health care workers come down with COVID too. He says that will exacerbate their surge even further as health care workers become too sick to help care for patients and some will end up needing hospital beds themselves.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70 hospital employees and another 20 clinic employees are now being quarantined or have COVID, Dr. Jones said.

“The situation is bleak for Mississippi hospitals,” said Timothy Moore, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association. He said he doesn’t expect it to get better anytime soon.

Mississippi has more patients hospitalized now than at any other point in the pandemic, said Thomas Dobbs, MD, MPH, the state epidemiologist.

“If we look at the rapidity of this rise, it’s really kind of terrifying and awe-inspiring,” Dr. Dobbs said in a news conference Aug. 11.

Schools are just starting back, and, in many parts of the South, districts are operating under a patchwork of policies – some require masks, while others have made them voluntary. Physicians say they are bracing for what these half measures could mean for pediatric cases and community transmission.

The only sure way for people to help themselves and their hospitals and schools, experts said, is vaccination.

“State data show that in this latest COVID surge, 97% of new COVID-19 infections, 89% of hospitalizations, and 82% of deaths occur in unvaccinated residents,” Mr. Moore said.

“To relieve pressure on hospitals, we need Mississippians – even those who have previously had COVID – to get vaccinated and wear a mask in public. The Delta variant is highly contagious and we need to do all we can to stop the spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”

Compounding the staffing problems, about half of hospital workers in Alabama are still unvaccinated. Dr. Williamson says they’re now starting to see these unvaccinated health care workers come down with COVID too. He says that will exacerbate their surge even further as health care workers become too sick to help care for patients and some will end up needing hospital beds themselves.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70 hospital employees and another 20 clinic employees are now being quarantined or have COVID, Dr. Jones said.

“The situation is bleak for Mississippi hospitals,” said Timothy Moore, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association. He said he doesn’t expect it to get better anytime soon.

Mississippi has more patients hospitalized now than at any other point in the pandemic, said Thomas Dobbs, MD, MPH, the state epidemiologist.

“If we look at the rapidity of this rise, it’s really kind of terrifying and awe-inspiring,” Dr. Dobbs said in a news conference Aug. 11.

Schools are just starting back, and, in many parts of the South, districts are operating under a patchwork of policies – some require masks, while others have made them voluntary. Physicians say they are bracing for what these half measures could mean for pediatric cases and community transmission.

The only sure way for people to help themselves and their hospitals and schools, experts said, is vaccination.

“State data show that in this latest COVID surge, 97% of new COVID-19 infections, 89% of hospitalizations, and 82% of deaths occur in unvaccinated residents,” Mr. Moore said.

“To relieve pressure on hospitals, we need Mississippians – even those who have previously had COVID – to get vaccinated and wear a mask in public. The Delta variant is highly contagious and we need to do all we can to stop the spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA may okay COVID booster for vulnerable adults before weekend: Media

according to multiple media reports.

The agency, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health, is working through the details of how booster doses for this population would work, and could authorize a third dose of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as early as Aug. 12, Politico reports.

About 2.7% of adults in the United States are immunocompromised, according to the CDC. This group includes people who have cancer, have received solid organ or stem cell transplants, have genetic conditions that weaken the immune function, have HIV, or are people with health conditions that require treatment with medications that turn down immune function, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Immune function also wanes with age, so the FDA could consider boosters for the elderly.

New research shows that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised patients who didn’t develop detectable levels of virus-fighting antibodies after two doses of a COVID vaccine will respond to a third dose.

A committee of independent experts that advises the CDC on the use of vaccines in the United States had previously signaled its support for giving boosters to those who are immunocompromised, but noted that it couldn’t officially recommend the strategy until the FDA had updated its emergency-use authorization for the shots or granted them a full biologics license, or “full approval.”

It’s unclear which mechanism the FDA might use, or exactly who will be eligible for the shots.

The United States would follow other nations such as Israel, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany in planning for or authorizing boosters for some vulnerable individuals.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has voiced strong opposition to the use of boosters in wealthy countries while much of the world still doesn’t have access to these lifesaving therapies. The WHO has asked wealthy nations to hold off on giving boosters until at least the end of September to give more people the opportunity to get a first dose.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meets again on Aug. 13 and is expected to discuss booster doses for this population of patients. The ACIP officially makes recommendations on the use of vaccines to the nation’s doctors.

The committee’s recommendation ensures that a vaccine will be covered by public and private insurers. Statutory vaccination requirements are also made based on the ACIP’s recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to multiple media reports.

The agency, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health, is working through the details of how booster doses for this population would work, and could authorize a third dose of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as early as Aug. 12, Politico reports.

About 2.7% of adults in the United States are immunocompromised, according to the CDC. This group includes people who have cancer, have received solid organ or stem cell transplants, have genetic conditions that weaken the immune function, have HIV, or are people with health conditions that require treatment with medications that turn down immune function, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Immune function also wanes with age, so the FDA could consider boosters for the elderly.

New research shows that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised patients who didn’t develop detectable levels of virus-fighting antibodies after two doses of a COVID vaccine will respond to a third dose.

A committee of independent experts that advises the CDC on the use of vaccines in the United States had previously signaled its support for giving boosters to those who are immunocompromised, but noted that it couldn’t officially recommend the strategy until the FDA had updated its emergency-use authorization for the shots or granted them a full biologics license, or “full approval.”

It’s unclear which mechanism the FDA might use, or exactly who will be eligible for the shots.

The United States would follow other nations such as Israel, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany in planning for or authorizing boosters for some vulnerable individuals.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has voiced strong opposition to the use of boosters in wealthy countries while much of the world still doesn’t have access to these lifesaving therapies. The WHO has asked wealthy nations to hold off on giving boosters until at least the end of September to give more people the opportunity to get a first dose.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meets again on Aug. 13 and is expected to discuss booster doses for this population of patients. The ACIP officially makes recommendations on the use of vaccines to the nation’s doctors.

The committee’s recommendation ensures that a vaccine will be covered by public and private insurers. Statutory vaccination requirements are also made based on the ACIP’s recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to multiple media reports.

The agency, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health, is working through the details of how booster doses for this population would work, and could authorize a third dose of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as early as Aug. 12, Politico reports.

About 2.7% of adults in the United States are immunocompromised, according to the CDC. This group includes people who have cancer, have received solid organ or stem cell transplants, have genetic conditions that weaken the immune function, have HIV, or are people with health conditions that require treatment with medications that turn down immune function, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Immune function also wanes with age, so the FDA could consider boosters for the elderly.

New research shows that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised patients who didn’t develop detectable levels of virus-fighting antibodies after two doses of a COVID vaccine will respond to a third dose.

A committee of independent experts that advises the CDC on the use of vaccines in the United States had previously signaled its support for giving boosters to those who are immunocompromised, but noted that it couldn’t officially recommend the strategy until the FDA had updated its emergency-use authorization for the shots or granted them a full biologics license, or “full approval.”

It’s unclear which mechanism the FDA might use, or exactly who will be eligible for the shots.

The United States would follow other nations such as Israel, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany in planning for or authorizing boosters for some vulnerable individuals.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has voiced strong opposition to the use of boosters in wealthy countries while much of the world still doesn’t have access to these lifesaving therapies. The WHO has asked wealthy nations to hold off on giving boosters until at least the end of September to give more people the opportunity to get a first dose.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meets again on Aug. 13 and is expected to discuss booster doses for this population of patients. The ACIP officially makes recommendations on the use of vaccines to the nation’s doctors.

The committee’s recommendation ensures that a vaccine will be covered by public and private insurers. Statutory vaccination requirements are also made based on the ACIP’s recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 mitigation measures led to shifts in typical annual respiratory virus patterns

Nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as masking, staying home, limiting travel, and social distancing, have been doing more than reducing the risk for COVID-19. They’re also having an impact on infection rates and the timing of seasonal surges of other common respiratory diseases, according to an article published July 23 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Typically, respiratory pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), common cold coronaviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and respiratory adenoviruses increase in the fall and remain high throughout winter, following the same basic patterns as influenza. Although the historically low rates of influenza remained low into spring 2021, that’s not the case for several other common respiratory viruses.

“Clinicians should be aware of increases in some respiratory virus activity and remain vigilant for off-season increases,” wrote Sonja J. Olsen, PhD, and her colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She told this news organization that clinicians should use multipathogen testing to help guide treatment.

The authors also underscore the importance of fall influenza vaccination campaigns for anyone aged 6 months or older.

Timothy Brewer, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, agreed that it’s important for health care professionals to consider off-season illnesses in their patients.

“Practitioners should be aware that if they see a sick child in the summer, outside of what normally might be influenza season, but they look like they have influenza, consider potentially influenza and test for it, because it might be possible that we may have disrupted that natural pattern,” Dr. Brewer told this news organization. Dr. Brewer, who was not involved in the CDC research, said it’s also “critically important” to encourage influenza vaccination as the season approaches.

The CDC researchers used the U.S. World Health Organization Collaborating Laboratories System and the CDC’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System to analyze virologic data from Oct. 3, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for influenza and Jan. 4, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for other respiratory viruses. The authors compared virus circulation during these periods to circulation during the same dates from four previous years.

Data to calculate influenza and RSV hospitalization rates came from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network and RSV Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

The authors report that flu activity dropped dramatically in March 2020 to its lowest levels since 1997, the earliest season for which data are available. Only 0.2% of more than 1 million specimens tested positive for influenza; the rate of hospitalizations for lab-confirmed flu was 0.8 per 100,000 people. Flu levels remained low through the summer, fall, and on to May 2021.

A potential drawback to this low activity, however, is a more prevalent and severe upcoming flu season, the authors write. The repeated exposure to flu viruses every year often “does not lead to illness, but it does serve to boost our immune response to influenza viruses,” Dr. Olsen said in an interview. “The absence of influenza viruses in the community over the last year means that we are not getting these regular boosts to our immune system. When we finally get exposed, our body may mount a weak response, and this could mean we develop a more clinically severe illness.”

Children are most susceptible to that phenomenon because they haven’t had a lifetime of exposure to flu viruses, Dr. Olsen said.

“An immunologically naive child may be more likely to develop a severe illness than someone who has lived through several influenza seasons,” she said. “This is why it is especially important for everyone 6 months and older to get vaccinated against influenza this season.”

Rhinovirus and enterovirus infections rebounded fairly quickly after their decline in March 2020 and started increasing in May 2020 until they reached “near prepandemic seasonal levels,” the authors write.

RSV infections dropped from 15.3% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.4% by April and then stayed below 1% through the end of 2020. In past years, weekly positive results climbed to 3% in October and peaked at 12.5% to 16.7% in late December. Instead, RSV weekly positive results began increasing in April 2021, rising from 1.1% to 2.8% in May.

The “unusually timed” late spring increase in RSV “is probably associated with various nonpharmaceutical measures that have been in place but are now relaxing,” Dr. Olsen stated.

The RSV hospitalization rate was 0.3 per 100,000 people from October 2020 to April 2021, compared to 27.1 and 33.4 per 100,000 people in the previous 2 years. Of all RSV hospitalizations in the past year, 76.5% occurred in April-May 2021.

Rates of illness caused by the four common human coronaviruses (OC43, NL63, 229E, and HKU1) dropped from 7.5% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.3% in April 2020 and stayed below 1% through February 2021. Then they climbed to 6.6% by May 2021. Infection rates of parainfluenza viruses types 1-4 similarly dropped from 2.6% in January 2020 to 1% in March 2020 and stayed below 1% until April 2021. Since then, rates of the common coronaviruses increased to 6.6% and parainfluenza viruses to 10.9% in May 2021.

Normally, parainfluenza viruses peak in October-November and May-June, so “the current increase could represent a return to prepandemic seasonality,” the authors write.