User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

There’s a much safer food allergy immunotherapy – why don’t more doctors offer it?

For the 32 million people in the United States with food allergies, those who seek relief beyond constant vigilance and EpiPens face a confusing treatment landscape. In January 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an oral immunotherapy product (Palforzia) for peanut-allergic children. Yet the product’s ill-timed release during a pandemic and its black-box warning about the risk for anaphylaxis has slowed uptake.

A small number of allergists offer home-grown oral immunotherapy (OIT), which builds protection by exposing patients to increasing daily doses of commercial food products over months. However, as with Palforzia, allergic reactions are common during treatment, and the hard-earned protection can fade if not maintained with regular dosing.

An alternate approach, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), delivers food proteins through liquid drops held in the mouth – a site rich in tolerance-inducing immune cells. In a 2019 study of peanut-allergic children aged 1-11 years, SLIT offered a level of protection on par with Palforzia while causing considerably fewer adverse events. And at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, researchers reported that SLIT produced stronger, more durable benefits in toddlers aged 1-4.

Sublingual immunotherapy is “a bunch of drops you put under your tongue, you hold it for a couple minutes, and then you’re done for the day,” said Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who led the two recent studies. For protecting against accidental ingestions, SLIT “is pushing pretty close to what OIT is able to provide but seemingly with a superior ease of administration and safety profile.”

Many parents don’t necessarily want their allergic kids to be able to eat a peanut butter sandwich – but do want them to be able to safely sit at the same lunch table and attend birthday parties with other kids. SLIT achieves this level of protection about as well as OIT, with fewer side effects.

Still, because of concerns about the treatment’s cost, unclear dosing regimens, and lack of FDA approval, very few U.S. allergists – likely less than 5% – offer sublingual immunotherapy to treat food allergies, making SLIT even less available than OIT.

Concerns about SLIT

One possible reason: Success is slower and less visible for SLIT. When patients undergo OIT, they build up to dosing with the actual food. “To a family who has a concern about their kid reacting, they can see them eating chunks of peanut in our office. That is really encouraging,” said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, an allergist with Halton Pediatric Allergy and assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

On the other hand, ingestion isn’t the focus for SLIT, so progress is harder to measure using metrics in published trials. After holding SLIT drops under the tongue, some patients spit them out. If they swallow the dose, it’s a vanishingly small amount. Immune changes that reflect increasing tolerance, such as a decrease in IgE antibodies, tend to be more gradual with SLIT than with OIT. And because SLIT is only offered in private clinics, such tests are not conducted as regularly as they would be for published trials.

But there may be a bigger factor: Some think earlier trials comparing the two immunotherapy regimens gave SLIT a bad rap. For example, in studies of milk- and peanut-allergic children conducted in 2011 and 2014, investigators concluded that SLIT was safer and that OIT appeared to be more effective. However, those trials compared SLIT with OIT using a much higher dose (2,000 mg) than is used in the licensed product (300 mg).

Over the years, endpoints for food allergy treatment trials have shifted from enabling patients to eat a full serving of their allergen to merely raising their threshold to guard against accidental exposures. So in those earlier articles, “we would probably write the discussion section differently now,” said Corinne Keet, MD, PhD, first author on the 2011 milk study and an associate professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Indeed, “when you compare [SLIT] to Palforzia or other studies of low-dose OIT (300 mg/d), they look equal in terms of their efficacy,” said senior author Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins. Yet, “I’m afraid we had a major [negative] impact on pharma’s interest in pursuing SLIT.”

Without corporate funding, it’s nearly impossible to conduct the large, multisite trials required for FDA approval of a treatment. And without approved products, many allergists are reluctant to offer the therapy, Dr. Wood said. It “makes your life a lot more complicated to be dabbling in things that are not approved,” he noted.

But at least one company is giving it a go. Applying the SLIT principle of delivering food allergens to tolerance-promoting immune cells in the mouth, New York–based Intrommune Therapeutics recently started enrolling peanut-allergic adults for a phase 1 trial of its experimental toothpaste.

Interest in food-allergy SLIT seems to be growing. “I definitely think that it could be an option for the future,” said Jaclyn Bjelac, MD, associate director of the Food Allergy Center of Excellence at the Cleveland Clinic. “Up until a few months ago, it really wasn’t on our radar.”

On conversations with Dr. Kim, philanthropists and drug developers said they found the recent data on SLIT promising, yet pointed out that food SLIT protocols and products are already in the public domain – they are described in published research using allergen extracts that are on the market. They “can’t see a commercial path forward,” Dr. Kim said in an interview. “And that’s kind of where many of my conversations end.”

Although there are no licensed SLIT products for food allergies, between 2014 and 2017, the FDA approved four sublingual immunotherapy tablets to treat environmental allergies – Stallergenes-Greer’s Oralair and ALK’s Grastek for grass pollens, ALK’s Odactra for dust mites, and ALK’s Ragwitek for short ragweed.

SLIT tablets work as well as allergy shots (subcutaneous immunotherapy) for controlling environmental allergy symptoms, they have a better safety profile, according to AAAAI guidelines, and they can be self-administered at home, which has made them a popular option globally. “Our European colleagues have used sublingual immunotherapy much more frequently than, for example, in the U.S.,” said Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Use of SLIT is also increasing in the United States, especially as FDA-approved products become available. In a 2019 survey, the percentage of U.S. allergists who said they were offering sublingual treatment for environmental allergies increased from 5.9% in 2007 to 73.5% in 2019. However, only 11.2% reported extensive SLIT use; the remainder reported some (50.5%) or little (38.3%) use.

As noted above, considerably fewer U.S. allergists use SLIT to treat food allergies. Similarly, a 2021 survey of allergists in Canada found that only 7% offered food sublingual immunotherapy; more than half reported offering OIT.

One practice, Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), has offered SLIT drops for food and environmental allergies for decades. Since the clinic opened in 1970, more than 200,000 people have been treated with its protocol. Every patient receives customized sublingual drops – “exactly what they’re allergic to, exactly how allergic they are, and then we build from there,” said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, practice executive at Allergy Associates of La Crosse. “Quite frankly, it’s the way immunotherapy should be done.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part one of a three-part series. Part two is here. Part three is here.

For the 32 million people in the United States with food allergies, those who seek relief beyond constant vigilance and EpiPens face a confusing treatment landscape. In January 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an oral immunotherapy product (Palforzia) for peanut-allergic children. Yet the product’s ill-timed release during a pandemic and its black-box warning about the risk for anaphylaxis has slowed uptake.

A small number of allergists offer home-grown oral immunotherapy (OIT), which builds protection by exposing patients to increasing daily doses of commercial food products over months. However, as with Palforzia, allergic reactions are common during treatment, and the hard-earned protection can fade if not maintained with regular dosing.

An alternate approach, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), delivers food proteins through liquid drops held in the mouth – a site rich in tolerance-inducing immune cells. In a 2019 study of peanut-allergic children aged 1-11 years, SLIT offered a level of protection on par with Palforzia while causing considerably fewer adverse events. And at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, researchers reported that SLIT produced stronger, more durable benefits in toddlers aged 1-4.

Sublingual immunotherapy is “a bunch of drops you put under your tongue, you hold it for a couple minutes, and then you’re done for the day,” said Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who led the two recent studies. For protecting against accidental ingestions, SLIT “is pushing pretty close to what OIT is able to provide but seemingly with a superior ease of administration and safety profile.”

Many parents don’t necessarily want their allergic kids to be able to eat a peanut butter sandwich – but do want them to be able to safely sit at the same lunch table and attend birthday parties with other kids. SLIT achieves this level of protection about as well as OIT, with fewer side effects.

Still, because of concerns about the treatment’s cost, unclear dosing regimens, and lack of FDA approval, very few U.S. allergists – likely less than 5% – offer sublingual immunotherapy to treat food allergies, making SLIT even less available than OIT.

Concerns about SLIT

One possible reason: Success is slower and less visible for SLIT. When patients undergo OIT, they build up to dosing with the actual food. “To a family who has a concern about their kid reacting, they can see them eating chunks of peanut in our office. That is really encouraging,” said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, an allergist with Halton Pediatric Allergy and assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

On the other hand, ingestion isn’t the focus for SLIT, so progress is harder to measure using metrics in published trials. After holding SLIT drops under the tongue, some patients spit them out. If they swallow the dose, it’s a vanishingly small amount. Immune changes that reflect increasing tolerance, such as a decrease in IgE antibodies, tend to be more gradual with SLIT than with OIT. And because SLIT is only offered in private clinics, such tests are not conducted as regularly as they would be for published trials.

But there may be a bigger factor: Some think earlier trials comparing the two immunotherapy regimens gave SLIT a bad rap. For example, in studies of milk- and peanut-allergic children conducted in 2011 and 2014, investigators concluded that SLIT was safer and that OIT appeared to be more effective. However, those trials compared SLIT with OIT using a much higher dose (2,000 mg) than is used in the licensed product (300 mg).

Over the years, endpoints for food allergy treatment trials have shifted from enabling patients to eat a full serving of their allergen to merely raising their threshold to guard against accidental exposures. So in those earlier articles, “we would probably write the discussion section differently now,” said Corinne Keet, MD, PhD, first author on the 2011 milk study and an associate professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Indeed, “when you compare [SLIT] to Palforzia or other studies of low-dose OIT (300 mg/d), they look equal in terms of their efficacy,” said senior author Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins. Yet, “I’m afraid we had a major [negative] impact on pharma’s interest in pursuing SLIT.”

Without corporate funding, it’s nearly impossible to conduct the large, multisite trials required for FDA approval of a treatment. And without approved products, many allergists are reluctant to offer the therapy, Dr. Wood said. It “makes your life a lot more complicated to be dabbling in things that are not approved,” he noted.

But at least one company is giving it a go. Applying the SLIT principle of delivering food allergens to tolerance-promoting immune cells in the mouth, New York–based Intrommune Therapeutics recently started enrolling peanut-allergic adults for a phase 1 trial of its experimental toothpaste.

Interest in food-allergy SLIT seems to be growing. “I definitely think that it could be an option for the future,” said Jaclyn Bjelac, MD, associate director of the Food Allergy Center of Excellence at the Cleveland Clinic. “Up until a few months ago, it really wasn’t on our radar.”

On conversations with Dr. Kim, philanthropists and drug developers said they found the recent data on SLIT promising, yet pointed out that food SLIT protocols and products are already in the public domain – they are described in published research using allergen extracts that are on the market. They “can’t see a commercial path forward,” Dr. Kim said in an interview. “And that’s kind of where many of my conversations end.”

Although there are no licensed SLIT products for food allergies, between 2014 and 2017, the FDA approved four sublingual immunotherapy tablets to treat environmental allergies – Stallergenes-Greer’s Oralair and ALK’s Grastek for grass pollens, ALK’s Odactra for dust mites, and ALK’s Ragwitek for short ragweed.

SLIT tablets work as well as allergy shots (subcutaneous immunotherapy) for controlling environmental allergy symptoms, they have a better safety profile, according to AAAAI guidelines, and they can be self-administered at home, which has made them a popular option globally. “Our European colleagues have used sublingual immunotherapy much more frequently than, for example, in the U.S.,” said Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Use of SLIT is also increasing in the United States, especially as FDA-approved products become available. In a 2019 survey, the percentage of U.S. allergists who said they were offering sublingual treatment for environmental allergies increased from 5.9% in 2007 to 73.5% in 2019. However, only 11.2% reported extensive SLIT use; the remainder reported some (50.5%) or little (38.3%) use.

As noted above, considerably fewer U.S. allergists use SLIT to treat food allergies. Similarly, a 2021 survey of allergists in Canada found that only 7% offered food sublingual immunotherapy; more than half reported offering OIT.

One practice, Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), has offered SLIT drops for food and environmental allergies for decades. Since the clinic opened in 1970, more than 200,000 people have been treated with its protocol. Every patient receives customized sublingual drops – “exactly what they’re allergic to, exactly how allergic they are, and then we build from there,” said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, practice executive at Allergy Associates of La Crosse. “Quite frankly, it’s the way immunotherapy should be done.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part one of a three-part series. Part two is here. Part three is here.

For the 32 million people in the United States with food allergies, those who seek relief beyond constant vigilance and EpiPens face a confusing treatment landscape. In January 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an oral immunotherapy product (Palforzia) for peanut-allergic children. Yet the product’s ill-timed release during a pandemic and its black-box warning about the risk for anaphylaxis has slowed uptake.

A small number of allergists offer home-grown oral immunotherapy (OIT), which builds protection by exposing patients to increasing daily doses of commercial food products over months. However, as with Palforzia, allergic reactions are common during treatment, and the hard-earned protection can fade if not maintained with regular dosing.

An alternate approach, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), delivers food proteins through liquid drops held in the mouth – a site rich in tolerance-inducing immune cells. In a 2019 study of peanut-allergic children aged 1-11 years, SLIT offered a level of protection on par with Palforzia while causing considerably fewer adverse events. And at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, researchers reported that SLIT produced stronger, more durable benefits in toddlers aged 1-4.

Sublingual immunotherapy is “a bunch of drops you put under your tongue, you hold it for a couple minutes, and then you’re done for the day,” said Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who led the two recent studies. For protecting against accidental ingestions, SLIT “is pushing pretty close to what OIT is able to provide but seemingly with a superior ease of administration and safety profile.”

Many parents don’t necessarily want their allergic kids to be able to eat a peanut butter sandwich – but do want them to be able to safely sit at the same lunch table and attend birthday parties with other kids. SLIT achieves this level of protection about as well as OIT, with fewer side effects.

Still, because of concerns about the treatment’s cost, unclear dosing regimens, and lack of FDA approval, very few U.S. allergists – likely less than 5% – offer sublingual immunotherapy to treat food allergies, making SLIT even less available than OIT.

Concerns about SLIT

One possible reason: Success is slower and less visible for SLIT. When patients undergo OIT, they build up to dosing with the actual food. “To a family who has a concern about their kid reacting, they can see them eating chunks of peanut in our office. That is really encouraging,” said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, an allergist with Halton Pediatric Allergy and assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

On the other hand, ingestion isn’t the focus for SLIT, so progress is harder to measure using metrics in published trials. After holding SLIT drops under the tongue, some patients spit them out. If they swallow the dose, it’s a vanishingly small amount. Immune changes that reflect increasing tolerance, such as a decrease in IgE antibodies, tend to be more gradual with SLIT than with OIT. And because SLIT is only offered in private clinics, such tests are not conducted as regularly as they would be for published trials.

But there may be a bigger factor: Some think earlier trials comparing the two immunotherapy regimens gave SLIT a bad rap. For example, in studies of milk- and peanut-allergic children conducted in 2011 and 2014, investigators concluded that SLIT was safer and that OIT appeared to be more effective. However, those trials compared SLIT with OIT using a much higher dose (2,000 mg) than is used in the licensed product (300 mg).

Over the years, endpoints for food allergy treatment trials have shifted from enabling patients to eat a full serving of their allergen to merely raising their threshold to guard against accidental exposures. So in those earlier articles, “we would probably write the discussion section differently now,” said Corinne Keet, MD, PhD, first author on the 2011 milk study and an associate professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Indeed, “when you compare [SLIT] to Palforzia or other studies of low-dose OIT (300 mg/d), they look equal in terms of their efficacy,” said senior author Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins. Yet, “I’m afraid we had a major [negative] impact on pharma’s interest in pursuing SLIT.”

Without corporate funding, it’s nearly impossible to conduct the large, multisite trials required for FDA approval of a treatment. And without approved products, many allergists are reluctant to offer the therapy, Dr. Wood said. It “makes your life a lot more complicated to be dabbling in things that are not approved,” he noted.

But at least one company is giving it a go. Applying the SLIT principle of delivering food allergens to tolerance-promoting immune cells in the mouth, New York–based Intrommune Therapeutics recently started enrolling peanut-allergic adults for a phase 1 trial of its experimental toothpaste.

Interest in food-allergy SLIT seems to be growing. “I definitely think that it could be an option for the future,” said Jaclyn Bjelac, MD, associate director of the Food Allergy Center of Excellence at the Cleveland Clinic. “Up until a few months ago, it really wasn’t on our radar.”

On conversations with Dr. Kim, philanthropists and drug developers said they found the recent data on SLIT promising, yet pointed out that food SLIT protocols and products are already in the public domain – they are described in published research using allergen extracts that are on the market. They “can’t see a commercial path forward,” Dr. Kim said in an interview. “And that’s kind of where many of my conversations end.”

Although there are no licensed SLIT products for food allergies, between 2014 and 2017, the FDA approved four sublingual immunotherapy tablets to treat environmental allergies – Stallergenes-Greer’s Oralair and ALK’s Grastek for grass pollens, ALK’s Odactra for dust mites, and ALK’s Ragwitek for short ragweed.

SLIT tablets work as well as allergy shots (subcutaneous immunotherapy) for controlling environmental allergy symptoms, they have a better safety profile, according to AAAAI guidelines, and they can be self-administered at home, which has made them a popular option globally. “Our European colleagues have used sublingual immunotherapy much more frequently than, for example, in the U.S.,” said Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Use of SLIT is also increasing in the United States, especially as FDA-approved products become available. In a 2019 survey, the percentage of U.S. allergists who said they were offering sublingual treatment for environmental allergies increased from 5.9% in 2007 to 73.5% in 2019. However, only 11.2% reported extensive SLIT use; the remainder reported some (50.5%) or little (38.3%) use.

As noted above, considerably fewer U.S. allergists use SLIT to treat food allergies. Similarly, a 2021 survey of allergists in Canada found that only 7% offered food sublingual immunotherapy; more than half reported offering OIT.

One practice, Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), has offered SLIT drops for food and environmental allergies for decades. Since the clinic opened in 1970, more than 200,000 people have been treated with its protocol. Every patient receives customized sublingual drops – “exactly what they’re allergic to, exactly how allergic they are, and then we build from there,” said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, practice executive at Allergy Associates of La Crosse. “Quite frankly, it’s the way immunotherapy should be done.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part one of a three-part series. Part two is here. Part three is here.

California’s highest COVID infection rates shift to rural counties

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

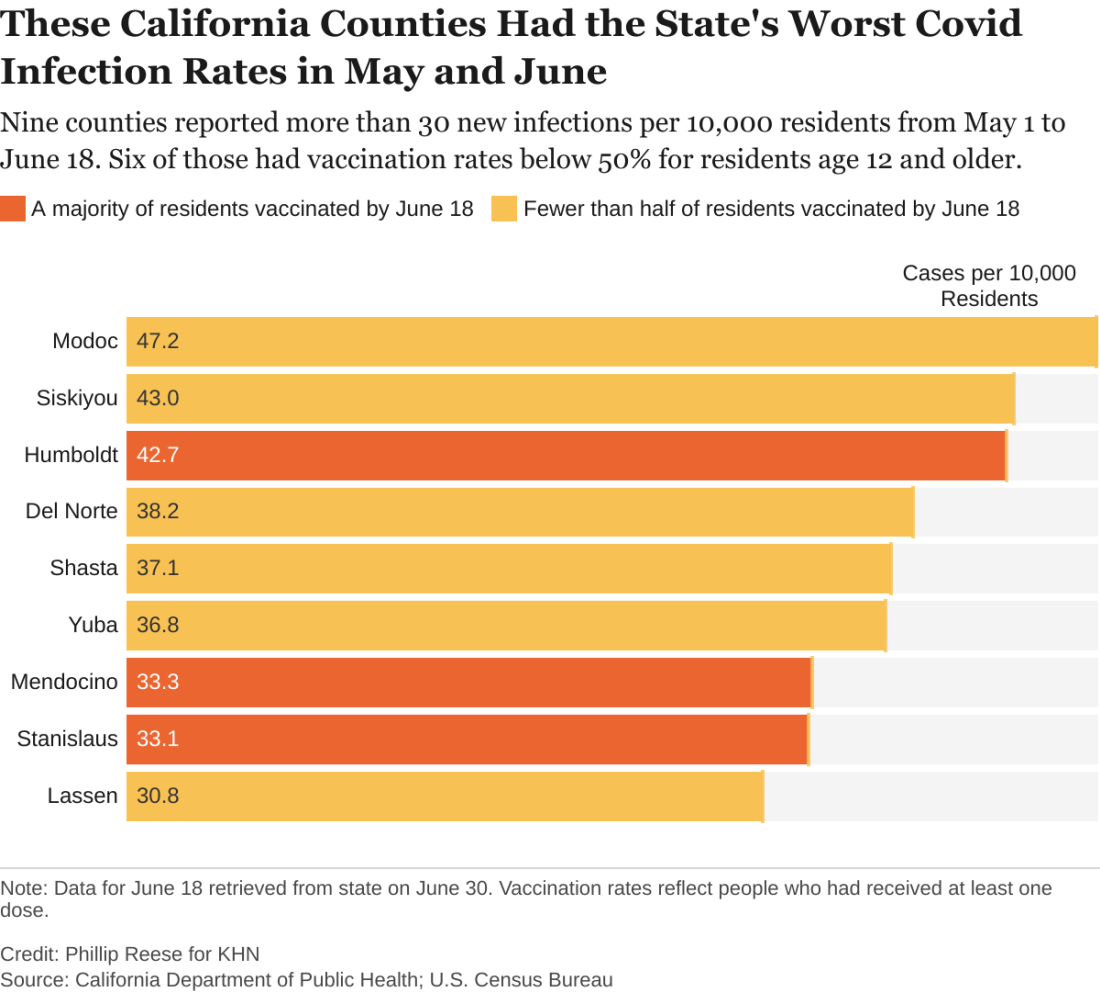

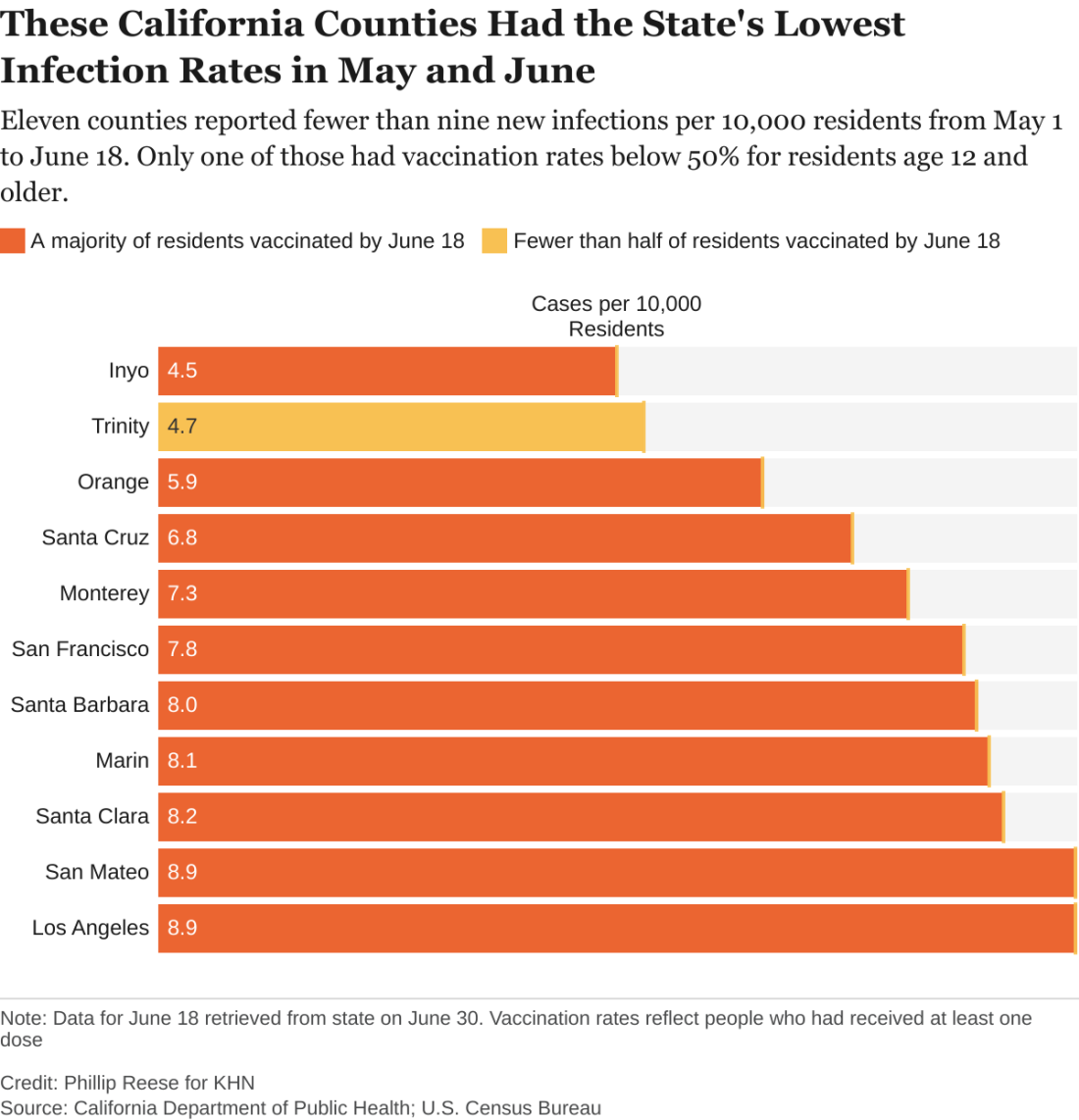

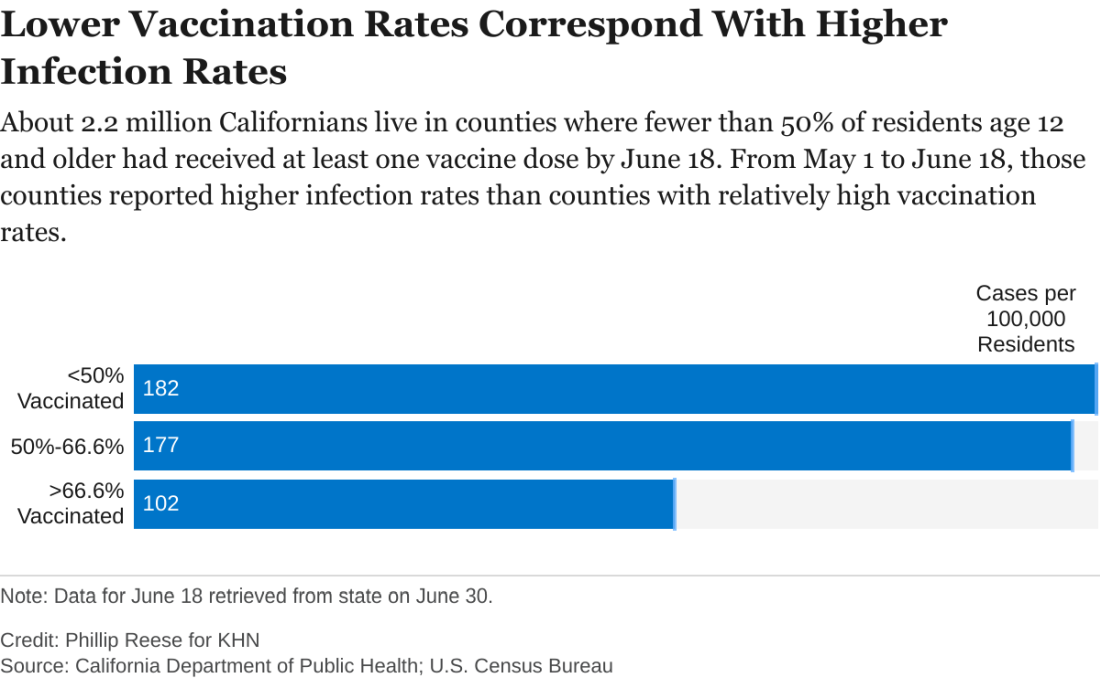

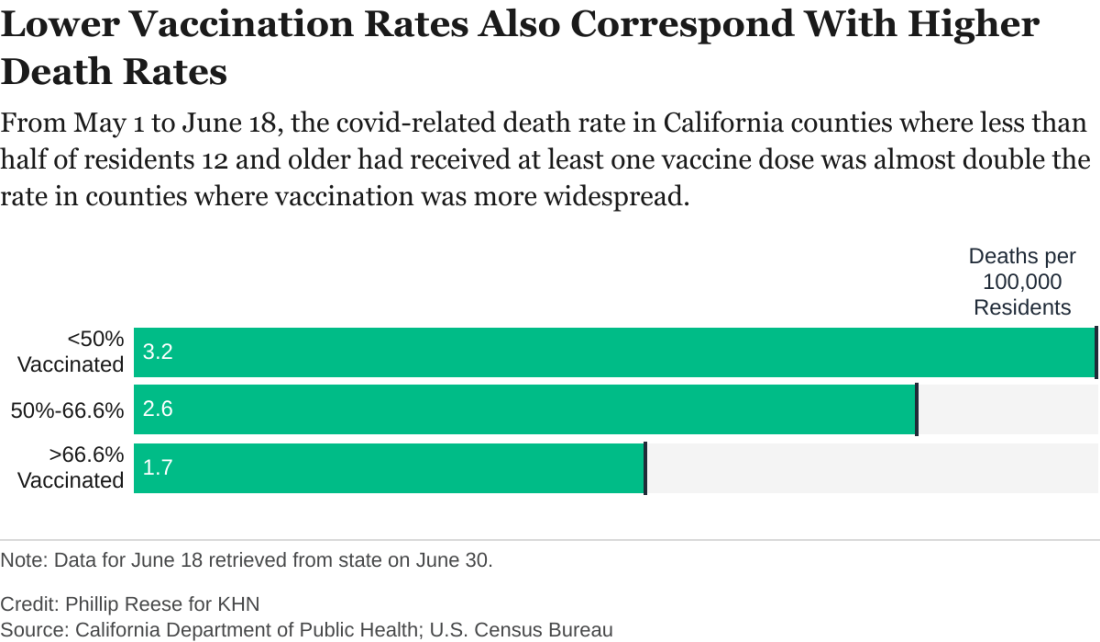

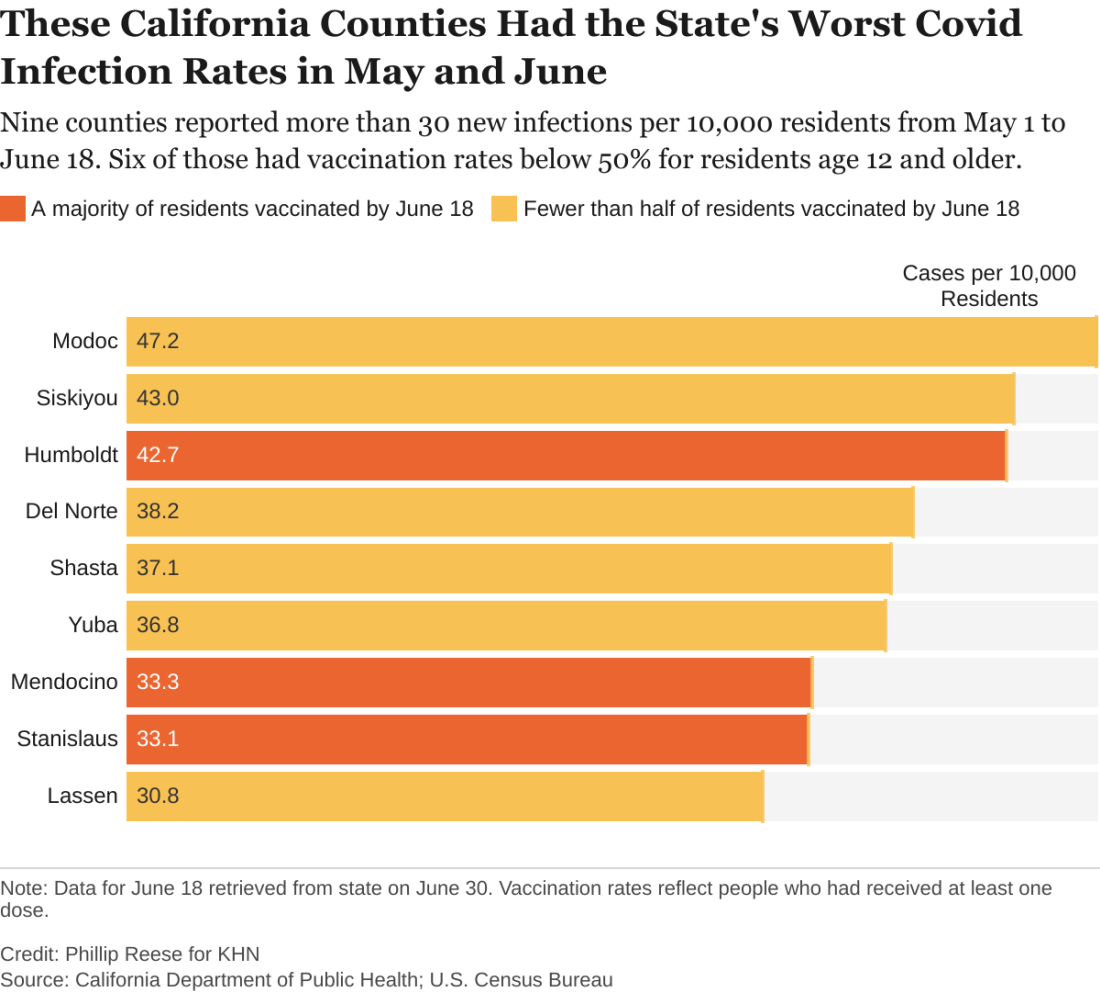

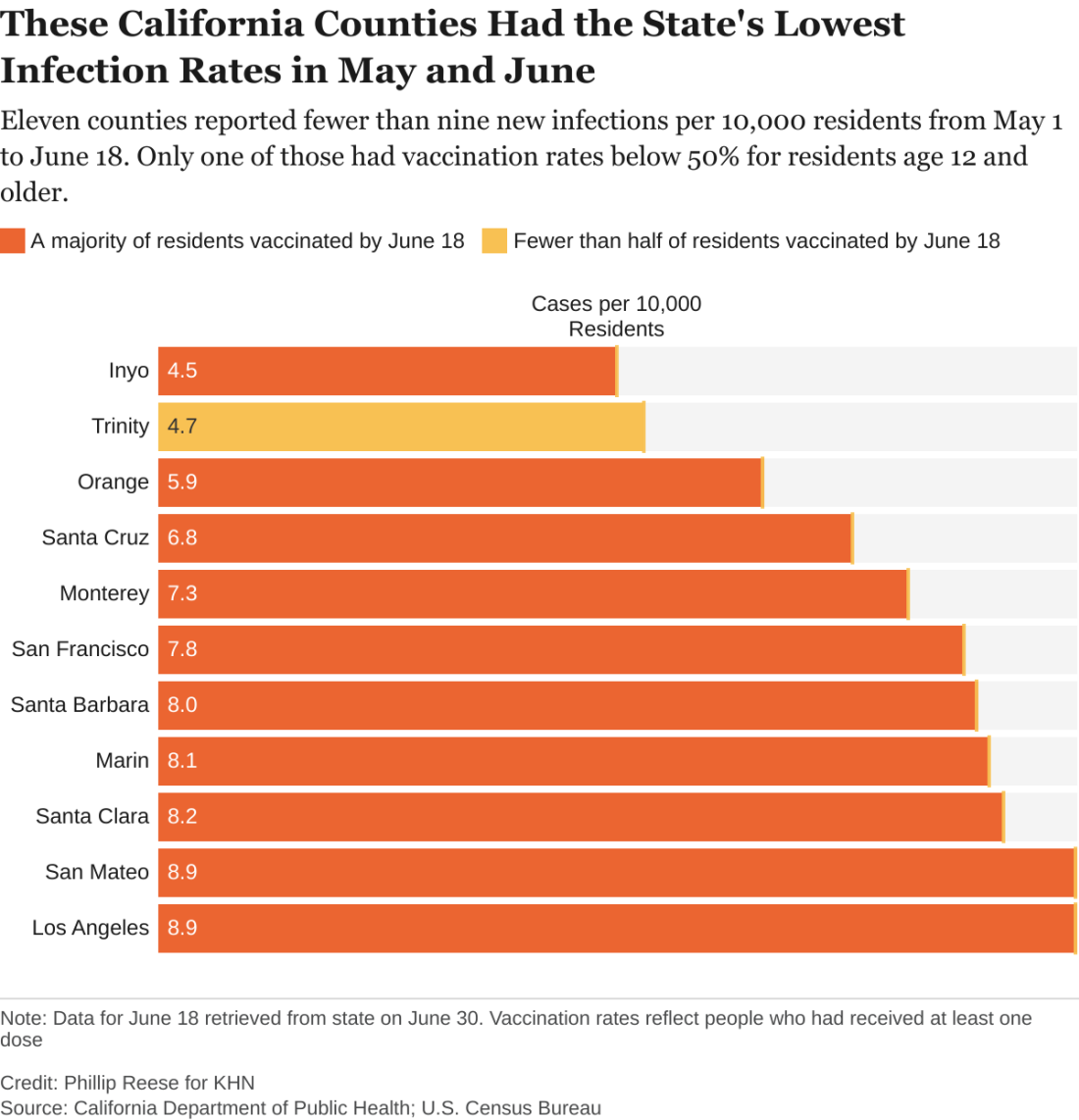

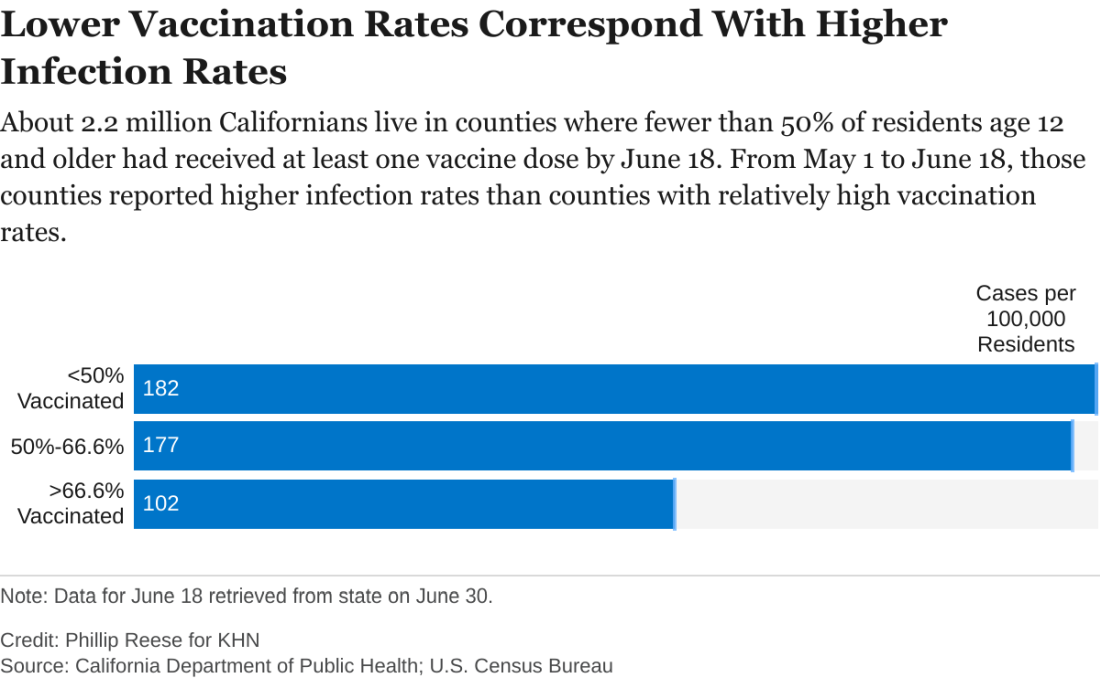

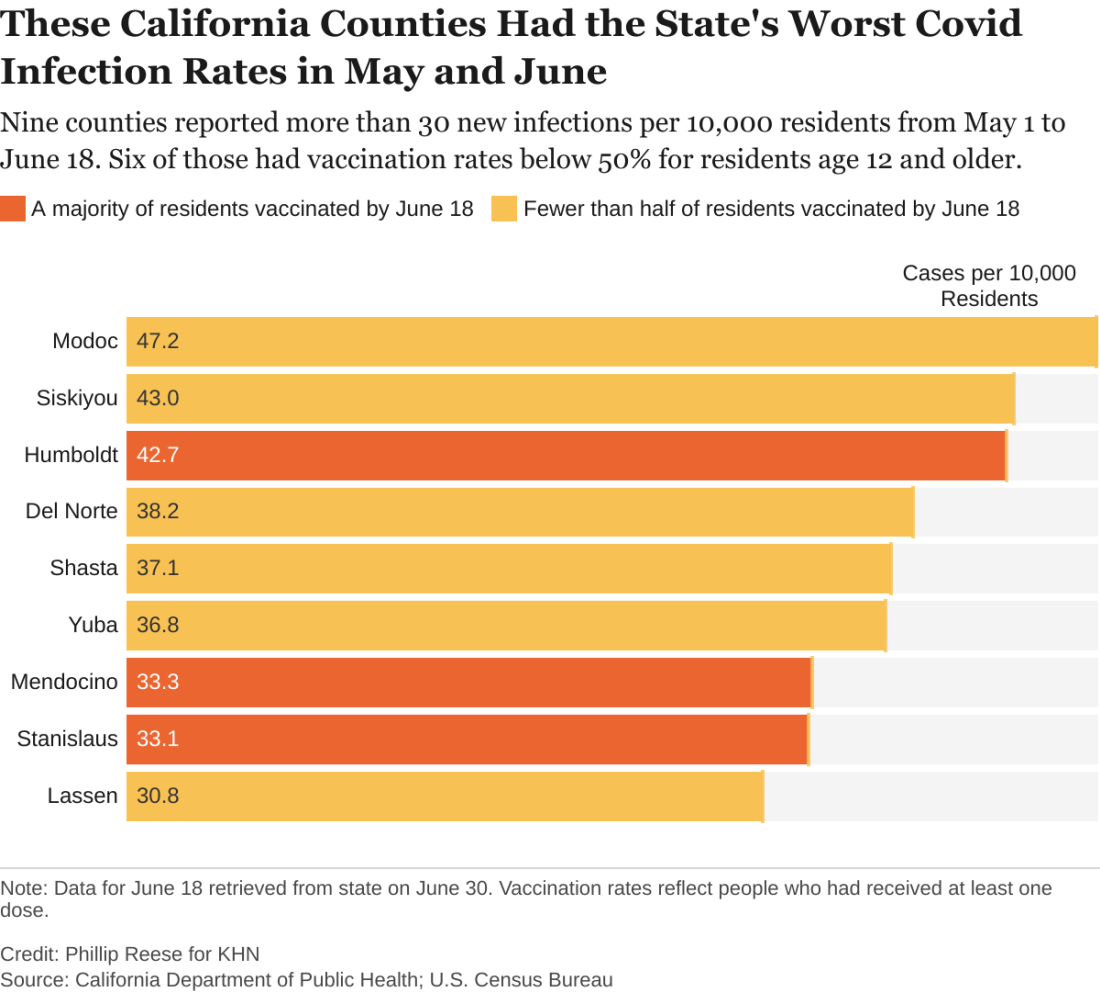

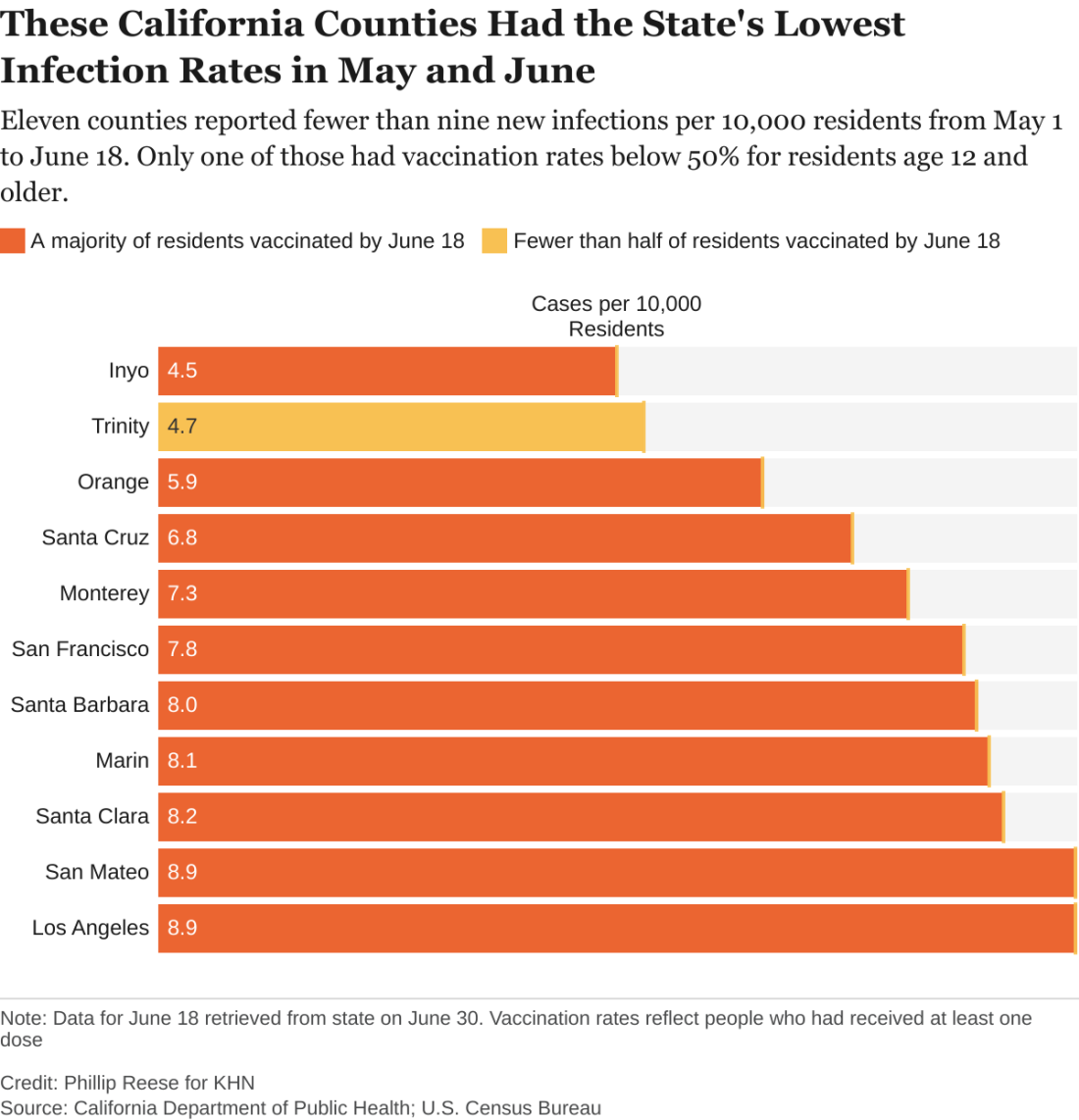

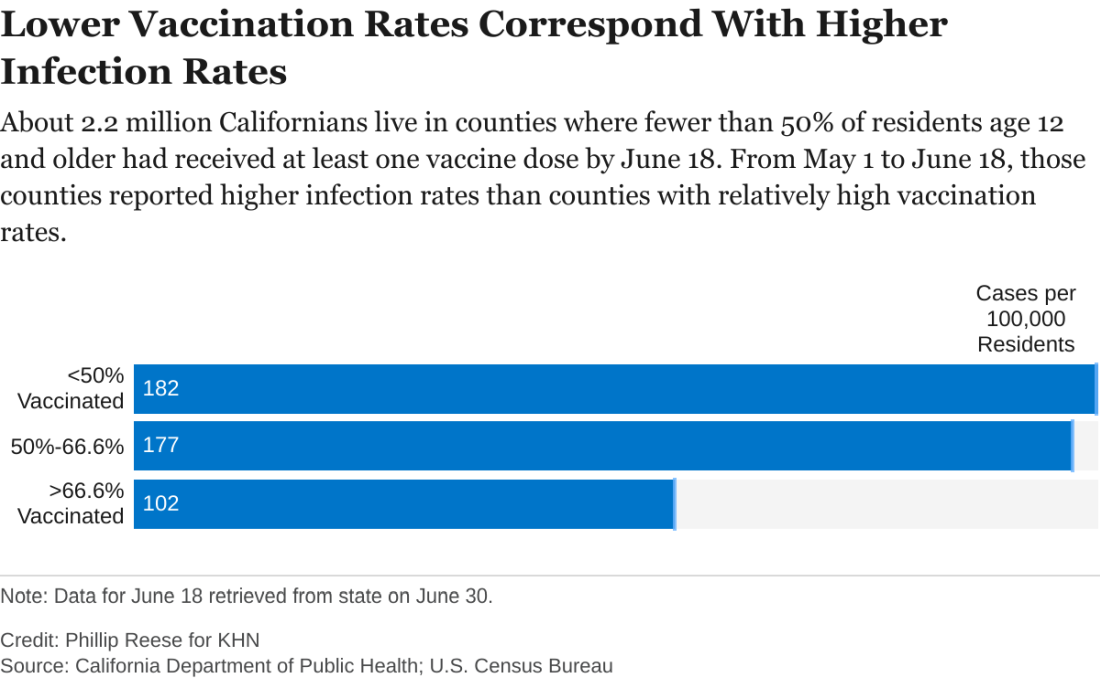

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

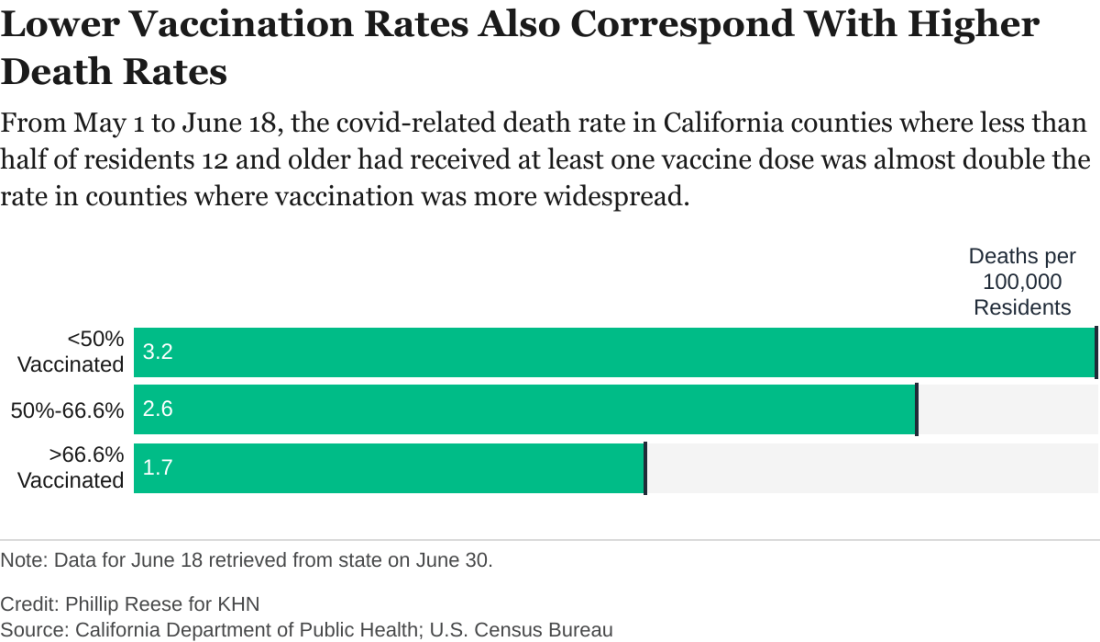

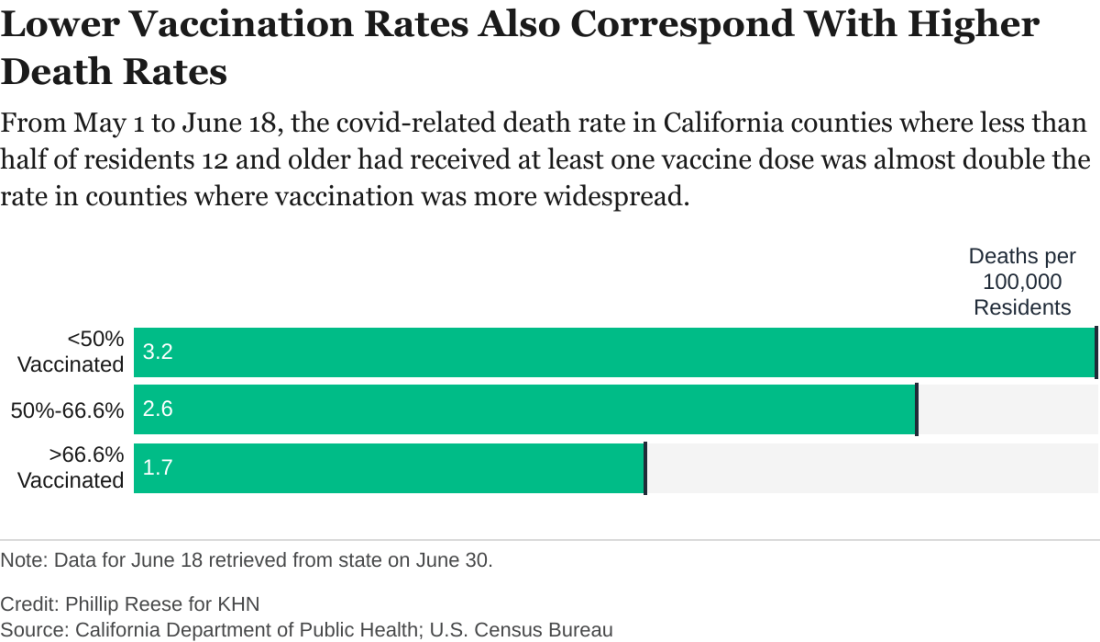

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Sleep-disordered breathing in neuromuscular disease: Early noninvasive ventilation needed

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in patients with neuromuscular disease and is increasingly addressed with noninvasive ventilation, but its patterns go beyond obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and include hypoventilation, hypoxemia, central sleep apnea, pseudocentrals, periodic breathing, and Cheyne-Stokes respiration, Gaurav Singh, MD, MPH said at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The prevalence of sleep-related disordered breathing surpasses 40% in patients diagnosed with neuromuscular disease, but “sleep disordered breathing [in these patients] does not equal obstructive sleep apnea,” said Dr. Singh, staff physician at the Veteran Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System in the section of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine, and an affiliated clinical assistant professor at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“The most common sleep-related breathing disorder in neuromuscular disease is probably hypopnea and hypoventilation with the sawtooth pattern of dips in oxygen saturation that occur during REM sleep,” he said. As neuromuscular diseases progress, hypoventilation may occur during non-REM sleep as well.

Evaluation is usually performed with polysomnography and pulmonary function testing, he said, but supplementary testing including serum bicarbonate levels, arterial blood gases, and echocardiography to assess for left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiomyopathy may be useful as well.

While a sleep study is not required per Centers for Medicare & Medicaid coverage criteria for the use of respiratory assist devices in patients with neuromuscular disease, polysomnography is valuable for identifying early nocturnal respiratory impairment before the appearance of symptoms and daytime abnormalities in gas exchange, and is better than home testing for distinguishing different types of events (including pseudocentrals). It also is helpful for determining the appropriate pressures needed for ventilatory support and for assessing the need for a backup rate, Dr. Singh said.

Commonly used types of noninvasive ventilation include bilevel positive airway pressure on the spontaneous/timed or pressure control modes, with or without volume-assured pressure support, he said.

Expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) is usually set low initially to help decrease the work of breathing and improve triggering, then titrated up to ensure that upper airway obstructive events are treated. Pressure support (the difference between the inspiratory positive airway pressure and EPAP) is set to achieve target tidal volume and to rest the respiratory muscles. And inspiratory time is set “on the longer end” to achieve maximal target volume and ensure appropriate gas exchange, Dr. Singh said.

Data from randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of NIV are limited, he said. A study published 15 years ago showed a survival benefit and improvement in quality of life measures in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with normal or moderately impaired bulbar function but not in those with severe bulbar weakness.

Regarding the timing of initiating NIV, a retrospective study published several years ago looked at almost 200 ALS patients and evaluated differences in survival amongst those started earlier with NIV (forced vital capacity ≥80%) and those started later (FVC <80%). At 36 months from diagnosis, mortality was 35% for the early group and 53% for the later group. “Improved survival was driven by benefit in patients with non–bulbar-onset ALS, compared with bulbar-onset disease,” Dr. Singh said.

“This study and several other similar studies seem to indicate that the earlier NIV [noninvasive ventilation] is started in patients with neuromuscular disease, the better in terms of improving survival and other relevant measures such as quality of life,” he said.

Asked about Dr. Singh’s presentation, Michelle Cao, DO, clinical associate professor at Stanford University, said that NIV is an “invaluable tool in the treatment of conditions leading to chronic respiratory failure,” such as neuromuscular disease, and that it’s important to incorporate NIV training for future pulmonary, critical care and sleep physicians. Dr. Cao directs the adult NIV program for the neuromuscular medical program at Stanford Health Care.

Saiprakash B. Venkateshiah, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also said in introducing Dr. Singh at the meeting that earlier diagnosis and appropriate NIV therapy “may improve quality of life and possibly even lower survival in certain disorders.”

In addition, he noted that sleep disturbances “may be the earliest sign of muscle weakness in [patients with neuromuscular disease], sometimes being detected before their underlying neuromuscular disease is diagnosed.”

Dr. Singh, Dr. Cao, and Dr. Venkateshiah each reported that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in patients with neuromuscular disease and is increasingly addressed with noninvasive ventilation, but its patterns go beyond obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and include hypoventilation, hypoxemia, central sleep apnea, pseudocentrals, periodic breathing, and Cheyne-Stokes respiration, Gaurav Singh, MD, MPH said at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The prevalence of sleep-related disordered breathing surpasses 40% in patients diagnosed with neuromuscular disease, but “sleep disordered breathing [in these patients] does not equal obstructive sleep apnea,” said Dr. Singh, staff physician at the Veteran Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System in the section of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine, and an affiliated clinical assistant professor at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“The most common sleep-related breathing disorder in neuromuscular disease is probably hypopnea and hypoventilation with the sawtooth pattern of dips in oxygen saturation that occur during REM sleep,” he said. As neuromuscular diseases progress, hypoventilation may occur during non-REM sleep as well.

Evaluation is usually performed with polysomnography and pulmonary function testing, he said, but supplementary testing including serum bicarbonate levels, arterial blood gases, and echocardiography to assess for left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiomyopathy may be useful as well.

While a sleep study is not required per Centers for Medicare & Medicaid coverage criteria for the use of respiratory assist devices in patients with neuromuscular disease, polysomnography is valuable for identifying early nocturnal respiratory impairment before the appearance of symptoms and daytime abnormalities in gas exchange, and is better than home testing for distinguishing different types of events (including pseudocentrals). It also is helpful for determining the appropriate pressures needed for ventilatory support and for assessing the need for a backup rate, Dr. Singh said.

Commonly used types of noninvasive ventilation include bilevel positive airway pressure on the spontaneous/timed or pressure control modes, with or without volume-assured pressure support, he said.

Expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) is usually set low initially to help decrease the work of breathing and improve triggering, then titrated up to ensure that upper airway obstructive events are treated. Pressure support (the difference between the inspiratory positive airway pressure and EPAP) is set to achieve target tidal volume and to rest the respiratory muscles. And inspiratory time is set “on the longer end” to achieve maximal target volume and ensure appropriate gas exchange, Dr. Singh said.

Data from randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of NIV are limited, he said. A study published 15 years ago showed a survival benefit and improvement in quality of life measures in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with normal or moderately impaired bulbar function but not in those with severe bulbar weakness.

Regarding the timing of initiating NIV, a retrospective study published several years ago looked at almost 200 ALS patients and evaluated differences in survival amongst those started earlier with NIV (forced vital capacity ≥80%) and those started later (FVC <80%). At 36 months from diagnosis, mortality was 35% for the early group and 53% for the later group. “Improved survival was driven by benefit in patients with non–bulbar-onset ALS, compared with bulbar-onset disease,” Dr. Singh said.

“This study and several other similar studies seem to indicate that the earlier NIV [noninvasive ventilation] is started in patients with neuromuscular disease, the better in terms of improving survival and other relevant measures such as quality of life,” he said.

Asked about Dr. Singh’s presentation, Michelle Cao, DO, clinical associate professor at Stanford University, said that NIV is an “invaluable tool in the treatment of conditions leading to chronic respiratory failure,” such as neuromuscular disease, and that it’s important to incorporate NIV training for future pulmonary, critical care and sleep physicians. Dr. Cao directs the adult NIV program for the neuromuscular medical program at Stanford Health Care.

Saiprakash B. Venkateshiah, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also said in introducing Dr. Singh at the meeting that earlier diagnosis and appropriate NIV therapy “may improve quality of life and possibly even lower survival in certain disorders.”

In addition, he noted that sleep disturbances “may be the earliest sign of muscle weakness in [patients with neuromuscular disease], sometimes being detected before their underlying neuromuscular disease is diagnosed.”

Dr. Singh, Dr. Cao, and Dr. Venkateshiah each reported that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in patients with neuromuscular disease and is increasingly addressed with noninvasive ventilation, but its patterns go beyond obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and include hypoventilation, hypoxemia, central sleep apnea, pseudocentrals, periodic breathing, and Cheyne-Stokes respiration, Gaurav Singh, MD, MPH said at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The prevalence of sleep-related disordered breathing surpasses 40% in patients diagnosed with neuromuscular disease, but “sleep disordered breathing [in these patients] does not equal obstructive sleep apnea,” said Dr. Singh, staff physician at the Veteran Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System in the section of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine, and an affiliated clinical assistant professor at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“The most common sleep-related breathing disorder in neuromuscular disease is probably hypopnea and hypoventilation with the sawtooth pattern of dips in oxygen saturation that occur during REM sleep,” he said. As neuromuscular diseases progress, hypoventilation may occur during non-REM sleep as well.

Evaluation is usually performed with polysomnography and pulmonary function testing, he said, but supplementary testing including serum bicarbonate levels, arterial blood gases, and echocardiography to assess for left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiomyopathy may be useful as well.

While a sleep study is not required per Centers for Medicare & Medicaid coverage criteria for the use of respiratory assist devices in patients with neuromuscular disease, polysomnography is valuable for identifying early nocturnal respiratory impairment before the appearance of symptoms and daytime abnormalities in gas exchange, and is better than home testing for distinguishing different types of events (including pseudocentrals). It also is helpful for determining the appropriate pressures needed for ventilatory support and for assessing the need for a backup rate, Dr. Singh said.

Commonly used types of noninvasive ventilation include bilevel positive airway pressure on the spontaneous/timed or pressure control modes, with or without volume-assured pressure support, he said.

Expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) is usually set low initially to help decrease the work of breathing and improve triggering, then titrated up to ensure that upper airway obstructive events are treated. Pressure support (the difference between the inspiratory positive airway pressure and EPAP) is set to achieve target tidal volume and to rest the respiratory muscles. And inspiratory time is set “on the longer end” to achieve maximal target volume and ensure appropriate gas exchange, Dr. Singh said.

Data from randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of NIV are limited, he said. A study published 15 years ago showed a survival benefit and improvement in quality of life measures in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with normal or moderately impaired bulbar function but not in those with severe bulbar weakness.

Regarding the timing of initiating NIV, a retrospective study published several years ago looked at almost 200 ALS patients and evaluated differences in survival amongst those started earlier with NIV (forced vital capacity ≥80%) and those started later (FVC <80%). At 36 months from diagnosis, mortality was 35% for the early group and 53% for the later group. “Improved survival was driven by benefit in patients with non–bulbar-onset ALS, compared with bulbar-onset disease,” Dr. Singh said.

“This study and several other similar studies seem to indicate that the earlier NIV [noninvasive ventilation] is started in patients with neuromuscular disease, the better in terms of improving survival and other relevant measures such as quality of life,” he said.

Asked about Dr. Singh’s presentation, Michelle Cao, DO, clinical associate professor at Stanford University, said that NIV is an “invaluable tool in the treatment of conditions leading to chronic respiratory failure,” such as neuromuscular disease, and that it’s important to incorporate NIV training for future pulmonary, critical care and sleep physicians. Dr. Cao directs the adult NIV program for the neuromuscular medical program at Stanford Health Care.

Saiprakash B. Venkateshiah, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also said in introducing Dr. Singh at the meeting that earlier diagnosis and appropriate NIV therapy “may improve quality of life and possibly even lower survival in certain disorders.”

In addition, he noted that sleep disturbances “may be the earliest sign of muscle weakness in [patients with neuromuscular disease], sometimes being detected before their underlying neuromuscular disease is diagnosed.”

Dr. Singh, Dr. Cao, and Dr. Venkateshiah each reported that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM SLEEP 2021

Delta becomes dominant coronavirus variant in U.S.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pandemic upped telemedicine use 100-fold in type 2 diabetes

The COVID-19 pandemic jump-started a significant role for telemedicine in the routine follow-up of U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, based on insurance claims records for more than 2.7 million American adults during 2019 and 2020.

During 2019, 0.3% of 1,357,029 adults with type 2 diabetes in a U.S. claims database, OptumLabs Data Warehouse, had one or more telemedicine visits. During 2020, this jumped to 29% of a similar group of U.S. adults once the pandemic kicked in, a nearly 100-fold increase, Sadiq Y. Patel, PhD, and coauthors wrote in a research letter published July 6, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The data show that telemedicine visits didn’t seem to negatively impact care, with hemoglobin A1c levels and medication fills remaining constant across the year.

But Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association, said these results, while reassuring, seem “quite surprising” relative to anecdotal reports from colleagues around the United States.

It’s possible they may only apply to the specific patients included in this study – which was limited to those with either commercial or Medicare Advantage health insurance – he noted in an interview.

Diabetes well-suited to telemedicine

Dr. Patel, of the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors said the information from their study showed “no evidence of a negative association with medication fills or glycemic control” among these patients during the pandemic in 2020, compared with the prepandemic year 2019.

During the first 48 weeks in 2020, A1c levels averaged 7.16% among patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with an average of 7.14% for patients with type 2 diabetes during the first 48 weeks of 2019. Fill rates for prescription medications were 64% during 2020 and 62% during 2019.

A1c levels and medication fill rates “are important markers of the quality of diabetes care, but obviously not the only important things,” said Ateev Mehrotra, MD, corresponding author for the study and a researcher in the same department as Dr. Patel.

“Limited to the metrics we looked at and in this population we did not see any substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the care for patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Mehrotra said in an interview.

“The pandemic catalyzed a tremendous shift to telemedicine among patients with diabetes. Because it is a chronic illness that requires frequent check-ins, diabetes is particularly well suited to using telemedicine,” he added.

Telemedicine not a complete replacement for in-patient visits

Dr. Gabbay agreed that “providers and patients have found telemedicine to be a helpful tool for managing patients with diabetes.”

But “most people do not think of this as a complete replacement for in-person visits, and most [U.S.] institutions have started to have more in-person visits. It’s probably about 50/50 at this point,” he said in an interview.

“It represents an impressive effort by the health care community to pivot toward telehealth to ensure that patients with diabetes continue to get care.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Gabbay added that “despite the success of telemedicine many patients still prefer to see their providers in person. I have a number of patients who were overjoyed to come in and be seen in person even when I offered telemedicine as an alternative. There is a relationship and trust piece that is more profound in person.”

And he cautioned that, although A1c “is a helpful measure, it may not fully demonstrate the percentage of patients at high risk.”

The data in the study by Dr. Patel and coauthors showing a steady level of medication refills during the pandemic “is encouraging,” he said, speculating that “people may have had more time [during the pandemic] to focus on medication adherence.”

More evidence of telemedicine’s leap

Other U.S. sites that follow patients with type 2 diabetes have recently reported similar findings, albeit on a much more localized level.

At Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., telemedicine consultations for patients with diabetes or other endocrinology disorders spurted from essentially none prior to March 2020 to a peak of nearly 700 visits/week in early May 2020, and then maintained a rate of roughly 500 telemedicine consultations weekly through the end of 2020, said Michelle L. Griffth, MD, during a talk at the 2021 annual ADA scientific sessions.

“We’ve made telehealth a permanent part of our practice,” said Dr. Griffith, medical director of telehealth ambulatory services at Vanderbilt. “We can use this boom in telehealth as a catalyst for diabetes-practice evolution,” she suggested.

It was a similar story at Scripps Health in southern California. During March and April 2020, video telemedicine consultations jumped from a prior rate of about 60/month to about 13,000/week, and then settled back to a monthly rate of about 25,000-30,000 during the balance of 2020, said Athena Philis-Tsimikas, MD, an endocrinologist and vice president of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, Calif. (These numbers include all telehealth consultations for patients at Scripps, not just patients with diabetes.)

“COVID sped up the process of integrating digital technology into health care,” concluded Dr. Philis-Tsimikas. A big factor driving this transition was the decision of many insurers to reimburse for telemedicine visits, something not done prepandemic.

The study received no commercial support. Dr. Patel, Dr. Mehrotra, Dr. Griffith, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas, and Dr. Gabbay reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic jump-started a significant role for telemedicine in the routine follow-up of U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, based on insurance claims records for more than 2.7 million American adults during 2019 and 2020.

During 2019, 0.3% of 1,357,029 adults with type 2 diabetes in a U.S. claims database, OptumLabs Data Warehouse, had one or more telemedicine visits. During 2020, this jumped to 29% of a similar group of U.S. adults once the pandemic kicked in, a nearly 100-fold increase, Sadiq Y. Patel, PhD, and coauthors wrote in a research letter published July 6, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The data show that telemedicine visits didn’t seem to negatively impact care, with hemoglobin A1c levels and medication fills remaining constant across the year.

But Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association, said these results, while reassuring, seem “quite surprising” relative to anecdotal reports from colleagues around the United States.

It’s possible they may only apply to the specific patients included in this study – which was limited to those with either commercial or Medicare Advantage health insurance – he noted in an interview.

Diabetes well-suited to telemedicine

Dr. Patel, of the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors said the information from their study showed “no evidence of a negative association with medication fills or glycemic control” among these patients during the pandemic in 2020, compared with the prepandemic year 2019.

During the first 48 weeks in 2020, A1c levels averaged 7.16% among patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with an average of 7.14% for patients with type 2 diabetes during the first 48 weeks of 2019. Fill rates for prescription medications were 64% during 2020 and 62% during 2019.

A1c levels and medication fill rates “are important markers of the quality of diabetes care, but obviously not the only important things,” said Ateev Mehrotra, MD, corresponding author for the study and a researcher in the same department as Dr. Patel.

“Limited to the metrics we looked at and in this population we did not see any substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the care for patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Mehrotra said in an interview.

“The pandemic catalyzed a tremendous shift to telemedicine among patients with diabetes. Because it is a chronic illness that requires frequent check-ins, diabetes is particularly well suited to using telemedicine,” he added.

Telemedicine not a complete replacement for in-patient visits

Dr. Gabbay agreed that “providers and patients have found telemedicine to be a helpful tool for managing patients with diabetes.”

But “most people do not think of this as a complete replacement for in-person visits, and most [U.S.] institutions have started to have more in-person visits. It’s probably about 50/50 at this point,” he said in an interview.

“It represents an impressive effort by the health care community to pivot toward telehealth to ensure that patients with diabetes continue to get care.”