User login

VIDEO: Second wave of psoriatic arthritis therapies

SANDESTIN, FLA. – An array of potential new options for psoriatic arthritis offers new targeted options and poses challenges for how to use the drugs, Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, said in a video interview at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

“We’re seeing a second wave – a second wave driven by the additional ways that we have to target aspects of the immune system relevant to psoriatic arthritis,” he said.

First used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal antibodies to interleukin targets, including IL12 and IL23 (ustekinumab) and IL17 (secukinumab and ixekizumab), have become established psoriatic arthritis therapies. Additionally, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib has become an option.

Other options in the pipeline include the JAK inhibitor baricitinib; the anti-IL23 monoclonal antibodies guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab; and even more anti-IL17 therapies, including brodalumab and bimekizumab .

“Now we have the synergy of having novel therapeutic approaches to maybe address some of the different domains of disease,” he said. Despite efforts to develop better biomarkers, it’s hard to predict how an individual patient will respond to a specific therapy. The longer the menu of therapeutic options, the better it is for patients.

As methotrexate remains a go-to treatment for many patients, new data from the SEAM trial assessing etanercept and methotrexate will address the question of whether the conventional drug and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors create therapeutic synergy in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Kavanaugh discussed the implications of the trial’s findings, which are expected to go public this summer.

SANDESTIN, FLA. – An array of potential new options for psoriatic arthritis offers new targeted options and poses challenges for how to use the drugs, Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, said in a video interview at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

“We’re seeing a second wave – a second wave driven by the additional ways that we have to target aspects of the immune system relevant to psoriatic arthritis,” he said.

First used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal antibodies to interleukin targets, including IL12 and IL23 (ustekinumab) and IL17 (secukinumab and ixekizumab), have become established psoriatic arthritis therapies. Additionally, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib has become an option.

Other options in the pipeline include the JAK inhibitor baricitinib; the anti-IL23 monoclonal antibodies guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab; and even more anti-IL17 therapies, including brodalumab and bimekizumab .

“Now we have the synergy of having novel therapeutic approaches to maybe address some of the different domains of disease,” he said. Despite efforts to develop better biomarkers, it’s hard to predict how an individual patient will respond to a specific therapy. The longer the menu of therapeutic options, the better it is for patients.

As methotrexate remains a go-to treatment for many patients, new data from the SEAM trial assessing etanercept and methotrexate will address the question of whether the conventional drug and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors create therapeutic synergy in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Kavanaugh discussed the implications of the trial’s findings, which are expected to go public this summer.

SANDESTIN, FLA. – An array of potential new options for psoriatic arthritis offers new targeted options and poses challenges for how to use the drugs, Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, said in a video interview at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

“We’re seeing a second wave – a second wave driven by the additional ways that we have to target aspects of the immune system relevant to psoriatic arthritis,” he said.

First used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal antibodies to interleukin targets, including IL12 and IL23 (ustekinumab) and IL17 (secukinumab and ixekizumab), have become established psoriatic arthritis therapies. Additionally, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib has become an option.

Other options in the pipeline include the JAK inhibitor baricitinib; the anti-IL23 monoclonal antibodies guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab; and even more anti-IL17 therapies, including brodalumab and bimekizumab .

“Now we have the synergy of having novel therapeutic approaches to maybe address some of the different domains of disease,” he said. Despite efforts to develop better biomarkers, it’s hard to predict how an individual patient will respond to a specific therapy. The longer the menu of therapeutic options, the better it is for patients.

As methotrexate remains a go-to treatment for many patients, new data from the SEAM trial assessing etanercept and methotrexate will address the question of whether the conventional drug and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors create therapeutic synergy in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Kavanaugh discussed the implications of the trial’s findings, which are expected to go public this summer.

REPORTING FROM CCR

Novel x-ray score distinguishes psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis of the hand

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A novel radiologic scoring system differentiated psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from nodal osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand in a pilot study.

“It’s a dilemma that’s faced, perhaps every couple of weeks, by most [rheumatologists]: Is it osteoarthritis or is it early psoriatic arthritis?” said Sardar Bahadur, MD, at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Both conditions are seen in daily practice, although the prevalence of hand OA is less frequent than knee OA. Approximately one in five of all adults in the United Kingdom have OA and 1%-2% have psoriasis. Of these, the prevalence of hand OA is about 11% and 0.1%-0.3% have psoriatic arthritis.

Being able to differentiate between the two conditions has important consequences for treatment, Dr. Bahadur said.

“Getting the diagnosis wrong could have major implications,” he said. “If you miss psoriatic arthritis, then potentially you are going to find irreversible joint damage causing pain and disability, and the opposite is also true, with misdiagnosis of osteoarthritis, with overuse of immunosuppression and all the cost implications as well as medicolegal consequences.”

Dr. Bahadur of the department of rehabilitation medicine and rheumatology at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre Headley Court, in Epsom, England, added: “So early diagnosis is very important, it means early treatment, it means better care, potentially preventing serious and irreversible damage.”

Together with researchers at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, Dr. Bahadur hypothesized that changes in hand x-rays were distinct and could be reliably used to differentiate between the two conditions. They developed a scoring system for hand radiographs that looked at the differences in the interphalangeal joints, soft tissue, and bone features of patients with known OA or PsA.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the aim was to focus on plain film radiographs of the hands because these were inexpensive, universally accessible, did not rely on radiologists’ interpretation, and changes in the hands were known to occur in both OA and PsA.

A total of 99 sets of hand x-rays taken between 2008 and 2016 from 50 patients with OA and 49 patients with PsA were obtained. These were anonymized and then analyzed by a musculoskeletal radiologist using the scoring system the team had developed. The radiologist was unaware of the patients’ clinical status. The results were then compared to the clinical diagnosis.

The novel method of scoring each x-ray was then taught to two rheumatology and one radiology trainee during a 1-hour training session and were then asked to score the same radiographs.

Dr. Bahadur reported that the radiologist reported normal hand radiographs in five patients and, of the remaining 94 sets of left- and right-hand radiographs, the scoring system correctly allocated 100% of images to either PsA, OA, or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Of note was that the radiologist correctly identified two patients with nodal hand OA who later developed PsA several years later, and one patient with RA who was initially thought to have PsA.

“The system could be successfully used by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur proposed. There was good agreement between the scoring system results and the clinical diagnosis then used by the trainees, with 88% and 67% of the radiographs correctly matched to the clinical diagnosis by the rheumatology trainees, and 70% for the radiology trainee.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the features that were consistently identified as being different between hand OA and PsA patients were soft tissue changes, such as dactylitis, as well as erosions, new bone formation, and other features such as subchondral surface changes and cysts.

The results of this single-center study show that the novel radiologic scoring system of hand radiographs was effective at differentiating patients with PsA from nodal OA.

“The ambition is to make this usable by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur said. A multicenter trial would be the next step to look at the use of the scoring system.

Dr. Bahadur had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Bahadur S et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.184

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A novel radiologic scoring system differentiated psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from nodal osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand in a pilot study.

“It’s a dilemma that’s faced, perhaps every couple of weeks, by most [rheumatologists]: Is it osteoarthritis or is it early psoriatic arthritis?” said Sardar Bahadur, MD, at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Both conditions are seen in daily practice, although the prevalence of hand OA is less frequent than knee OA. Approximately one in five of all adults in the United Kingdom have OA and 1%-2% have psoriasis. Of these, the prevalence of hand OA is about 11% and 0.1%-0.3% have psoriatic arthritis.

Being able to differentiate between the two conditions has important consequences for treatment, Dr. Bahadur said.

“Getting the diagnosis wrong could have major implications,” he said. “If you miss psoriatic arthritis, then potentially you are going to find irreversible joint damage causing pain and disability, and the opposite is also true, with misdiagnosis of osteoarthritis, with overuse of immunosuppression and all the cost implications as well as medicolegal consequences.”

Dr. Bahadur of the department of rehabilitation medicine and rheumatology at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre Headley Court, in Epsom, England, added: “So early diagnosis is very important, it means early treatment, it means better care, potentially preventing serious and irreversible damage.”

Together with researchers at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, Dr. Bahadur hypothesized that changes in hand x-rays were distinct and could be reliably used to differentiate between the two conditions. They developed a scoring system for hand radiographs that looked at the differences in the interphalangeal joints, soft tissue, and bone features of patients with known OA or PsA.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the aim was to focus on plain film radiographs of the hands because these were inexpensive, universally accessible, did not rely on radiologists’ interpretation, and changes in the hands were known to occur in both OA and PsA.

A total of 99 sets of hand x-rays taken between 2008 and 2016 from 50 patients with OA and 49 patients with PsA were obtained. These were anonymized and then analyzed by a musculoskeletal radiologist using the scoring system the team had developed. The radiologist was unaware of the patients’ clinical status. The results were then compared to the clinical diagnosis.

The novel method of scoring each x-ray was then taught to two rheumatology and one radiology trainee during a 1-hour training session and were then asked to score the same radiographs.

Dr. Bahadur reported that the radiologist reported normal hand radiographs in five patients and, of the remaining 94 sets of left- and right-hand radiographs, the scoring system correctly allocated 100% of images to either PsA, OA, or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Of note was that the radiologist correctly identified two patients with nodal hand OA who later developed PsA several years later, and one patient with RA who was initially thought to have PsA.

“The system could be successfully used by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur proposed. There was good agreement between the scoring system results and the clinical diagnosis then used by the trainees, with 88% and 67% of the radiographs correctly matched to the clinical diagnosis by the rheumatology trainees, and 70% for the radiology trainee.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the features that were consistently identified as being different between hand OA and PsA patients were soft tissue changes, such as dactylitis, as well as erosions, new bone formation, and other features such as subchondral surface changes and cysts.

The results of this single-center study show that the novel radiologic scoring system of hand radiographs was effective at differentiating patients with PsA from nodal OA.

“The ambition is to make this usable by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur said. A multicenter trial would be the next step to look at the use of the scoring system.

Dr. Bahadur had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Bahadur S et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.184

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A novel radiologic scoring system differentiated psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from nodal osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand in a pilot study.

“It’s a dilemma that’s faced, perhaps every couple of weeks, by most [rheumatologists]: Is it osteoarthritis or is it early psoriatic arthritis?” said Sardar Bahadur, MD, at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Both conditions are seen in daily practice, although the prevalence of hand OA is less frequent than knee OA. Approximately one in five of all adults in the United Kingdom have OA and 1%-2% have psoriasis. Of these, the prevalence of hand OA is about 11% and 0.1%-0.3% have psoriatic arthritis.

Being able to differentiate between the two conditions has important consequences for treatment, Dr. Bahadur said.

“Getting the diagnosis wrong could have major implications,” he said. “If you miss psoriatic arthritis, then potentially you are going to find irreversible joint damage causing pain and disability, and the opposite is also true, with misdiagnosis of osteoarthritis, with overuse of immunosuppression and all the cost implications as well as medicolegal consequences.”

Dr. Bahadur of the department of rehabilitation medicine and rheumatology at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre Headley Court, in Epsom, England, added: “So early diagnosis is very important, it means early treatment, it means better care, potentially preventing serious and irreversible damage.”

Together with researchers at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, Dr. Bahadur hypothesized that changes in hand x-rays were distinct and could be reliably used to differentiate between the two conditions. They developed a scoring system for hand radiographs that looked at the differences in the interphalangeal joints, soft tissue, and bone features of patients with known OA or PsA.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the aim was to focus on plain film radiographs of the hands because these were inexpensive, universally accessible, did not rely on radiologists’ interpretation, and changes in the hands were known to occur in both OA and PsA.

A total of 99 sets of hand x-rays taken between 2008 and 2016 from 50 patients with OA and 49 patients with PsA were obtained. These were anonymized and then analyzed by a musculoskeletal radiologist using the scoring system the team had developed. The radiologist was unaware of the patients’ clinical status. The results were then compared to the clinical diagnosis.

The novel method of scoring each x-ray was then taught to two rheumatology and one radiology trainee during a 1-hour training session and were then asked to score the same radiographs.

Dr. Bahadur reported that the radiologist reported normal hand radiographs in five patients and, of the remaining 94 sets of left- and right-hand radiographs, the scoring system correctly allocated 100% of images to either PsA, OA, or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Of note was that the radiologist correctly identified two patients with nodal hand OA who later developed PsA several years later, and one patient with RA who was initially thought to have PsA.

“The system could be successfully used by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur proposed. There was good agreement between the scoring system results and the clinical diagnosis then used by the trainees, with 88% and 67% of the radiographs correctly matched to the clinical diagnosis by the rheumatology trainees, and 70% for the radiology trainee.

Dr. Bahadur noted that the features that were consistently identified as being different between hand OA and PsA patients were soft tissue changes, such as dactylitis, as well as erosions, new bone formation, and other features such as subchondral surface changes and cysts.

The results of this single-center study show that the novel radiologic scoring system of hand radiographs was effective at differentiating patients with PsA from nodal OA.

“The ambition is to make this usable by nonradiologists,” Dr. Bahadur said. A multicenter trial would be the next step to look at the use of the scoring system.

Dr. Bahadur had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Bahadur S et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.184

REPORTING FROM RHEUMATOLOGY 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Using the scoring system, 100% of images were correctly allocated to PsA, OA, or RA.

Study details: Single center pilot study assessing 99 x-rays of both hands taken between 2008 and 2016 of patients with OA (n = 50) or PsA (n = 49).

Disclosures: Dr. Bahadur had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Bahadur S et al., Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.184

Methotrexate-induced pulmonary fibrosis risk examined in 10-year study

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A 10-year follow up of patients with inflammatory arthritis has shown that methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk of pulmonary fibrosis.

“As rheumatologists, it’s a really important message that methotrexate does not cause chronic pulmonary fibrosis and it should not be stopped because of pulmonary fibrosis,” Julie Dawson, MD, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. “It’s the rheumatoid arthritis. It’s not the methotrexate.”

Dr. Dawson, of St. Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, St. Helens, England, added that the current findings were consistent with her team’s prior research looking at earlier time periods. There was also no correlation between the duration or dose of methotrexate used and the development of the lung disease, she said.

“If anything, the suggestion is you’d be more symptomatic if you delay using methotrexate,” Dr. Dawson observed. If patients are not doing well on methotrexate, then perhaps adjusting therapy or changing to another drug would of course be the next step, but if patients are well controlled then “stopping it is the worst thing to do” for their arthritis, she said.

“This is of great clinical interest, and we can be reassured now about this, I think. This is really good, long-term data,” said Devesh Mewar, MD, of Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, Liverpool, England, who was not involved in the research.

“We know that methotrexate is associated with a pneumonitis reaction, but there is no high-quality evidence that methotrexate is associated with a chronic pulmonary fibrosis” Dr. Dawson said, explaining the rationale for the current study she presented during a poster session. Previous studies considered data for up to 5 years, she added, so the aim of the current study, therefore, was to look at the longer-term effect of methotrexate use on the incidence of pulmonary fibrosis.

Data on 129 patients who had started treatment with methotrexate from 2004 to 2007 were analyzed, of whom 63 (49%) had stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years. Most (82%) had been given methotrexate to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with other indications including inflammatory arthritis (5.4%) and psoriatic arthritis (4.7%).

“Practice was different 10 years ago, so just 56% of patients commenced methotrexate within the first year of the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Dawson reported.

Only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis were seen, all in the RA patients, and three of these were in patients who had started methotrexate over 1 year after their diagnosis. The incidence of 3.8% seen in the study matches the expected incidence of pulmonary fibrosis in RA and was actually “at the lower end of the expected incidence,” Dr. Dawson said. Previous studies have suggested an incidence rate of RA-associated interstitial lung disease of about 3%-7%.

All of the pulmonary fibrosis cases had occurred in men and 75% were seropositive for rheumatoid factor. The mean duration of RA at the time of onset of pulmonary fibrosis was 7.8 years and the usual interstitial pattern of fibrosis was seen. The 125 patients without pulmonary fibrosis had taken methotrexate for a mean of 8 years at a mean final weekly dose of 16.3 mg, compared with a mean of 6 years at a mean dose of 18.1 mg per week in the 4 patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

One of the next steps is to look at cases where methotrexate has been stopped and the effects of that on pulmonary fibrosis and disease activity. In Dr. Dawson’s experience, stopping methotrexate just affects the management of the arthritis and had no difference to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

If patients start to experience any lung symptoms while continuing methotrexate, such as shortness of breath, then they would need to be assessed and undergo lung function tests to monitor their condition. Treating the fibrosis using an antifibrotic drug, such as pirfenidone, is something that might be possible in the future, but this needs investigation in inflammatory arthritis as the drug is currently only licensed for use in idiopathic cases.

This is something the British Rheumatoid Interstitial Lung network plans to investigate in a placebo-controlled study of RA patients with fibrotic lung disease. “We’re looking to see if antifibrotic agents are going to slow the disease as it does in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is obviously quite exciting when it’s such a hard condition to treat,” said Dr. Dawson, who will be one of the study’s investigators.

Dr. Dawson had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Mewar was not involved in the study and had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Dawson J et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.470.

The subject of this retrospective study is of great interest. The authors point out that pulmonary fibrosis (as opposed to acute allergic reaction, which is extremely rare) is also extremely uncommon in patients using methotrexate over the long haul. Over 10 years, their data points to a 3.1% incidence of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis.

The issue here is its generalizability. There were 63 patients who used methotrexate for 10 years or more and 88 who used it for 5 years or more, according to the poster. This must represent a highly selected population. For example, what percent of the total RA/psoriatic arthritis/”inflammatory arthritis” population do these patients represent, i.e., what is the denominator here? The authors stated that the 63 patients who stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years represent 49% of the 129 patients on methotrexate overall in the study. This is a highly unusual datum, as most of the literature indicates that only 40% or less of patients stay on methotrexate for even 5 years. And this completely ignores the issue of adherence over this long a period; these patients must represent a truly minuscule percentage of the total if they actually stayed on methotrexate with even moderate adherence for 10 years.

Importantly, the authors point out that they had only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis. Once more, this points to the highly selective group of patients seen, as this study does not examine patients with asymptomatic pulmonary fibrosis, including those with fibrosis on high-resolution CT of the lungs or chest film or evidence of abnormalities on pulmonary function tests, but who do not have sufficient symptoms ascribed to methotrexate to bring them to medical attention.

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who also is affiliated with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Florence, Italy. He was not involved with the study.

The subject of this retrospective study is of great interest. The authors point out that pulmonary fibrosis (as opposed to acute allergic reaction, which is extremely rare) is also extremely uncommon in patients using methotrexate over the long haul. Over 10 years, their data points to a 3.1% incidence of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis.

The issue here is its generalizability. There were 63 patients who used methotrexate for 10 years or more and 88 who used it for 5 years or more, according to the poster. This must represent a highly selected population. For example, what percent of the total RA/psoriatic arthritis/”inflammatory arthritis” population do these patients represent, i.e., what is the denominator here? The authors stated that the 63 patients who stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years represent 49% of the 129 patients on methotrexate overall in the study. This is a highly unusual datum, as most of the literature indicates that only 40% or less of patients stay on methotrexate for even 5 years. And this completely ignores the issue of adherence over this long a period; these patients must represent a truly minuscule percentage of the total if they actually stayed on methotrexate with even moderate adherence for 10 years.

Importantly, the authors point out that they had only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis. Once more, this points to the highly selective group of patients seen, as this study does not examine patients with asymptomatic pulmonary fibrosis, including those with fibrosis on high-resolution CT of the lungs or chest film or evidence of abnormalities on pulmonary function tests, but who do not have sufficient symptoms ascribed to methotrexate to bring them to medical attention.

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who also is affiliated with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Florence, Italy. He was not involved with the study.

The subject of this retrospective study is of great interest. The authors point out that pulmonary fibrosis (as opposed to acute allergic reaction, which is extremely rare) is also extremely uncommon in patients using methotrexate over the long haul. Over 10 years, their data points to a 3.1% incidence of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis.

The issue here is its generalizability. There were 63 patients who used methotrexate for 10 years or more and 88 who used it for 5 years or more, according to the poster. This must represent a highly selected population. For example, what percent of the total RA/psoriatic arthritis/”inflammatory arthritis” population do these patients represent, i.e., what is the denominator here? The authors stated that the 63 patients who stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years represent 49% of the 129 patients on methotrexate overall in the study. This is a highly unusual datum, as most of the literature indicates that only 40% or less of patients stay on methotrexate for even 5 years. And this completely ignores the issue of adherence over this long a period; these patients must represent a truly minuscule percentage of the total if they actually stayed on methotrexate with even moderate adherence for 10 years.

Importantly, the authors point out that they had only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis. Once more, this points to the highly selective group of patients seen, as this study does not examine patients with asymptomatic pulmonary fibrosis, including those with fibrosis on high-resolution CT of the lungs or chest film or evidence of abnormalities on pulmonary function tests, but who do not have sufficient symptoms ascribed to methotrexate to bring them to medical attention.

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who also is affiliated with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Florence, Italy. He was not involved with the study.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A 10-year follow up of patients with inflammatory arthritis has shown that methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk of pulmonary fibrosis.

“As rheumatologists, it’s a really important message that methotrexate does not cause chronic pulmonary fibrosis and it should not be stopped because of pulmonary fibrosis,” Julie Dawson, MD, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. “It’s the rheumatoid arthritis. It’s not the methotrexate.”

Dr. Dawson, of St. Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, St. Helens, England, added that the current findings were consistent with her team’s prior research looking at earlier time periods. There was also no correlation between the duration or dose of methotrexate used and the development of the lung disease, she said.

“If anything, the suggestion is you’d be more symptomatic if you delay using methotrexate,” Dr. Dawson observed. If patients are not doing well on methotrexate, then perhaps adjusting therapy or changing to another drug would of course be the next step, but if patients are well controlled then “stopping it is the worst thing to do” for their arthritis, she said.

“This is of great clinical interest, and we can be reassured now about this, I think. This is really good, long-term data,” said Devesh Mewar, MD, of Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, Liverpool, England, who was not involved in the research.

“We know that methotrexate is associated with a pneumonitis reaction, but there is no high-quality evidence that methotrexate is associated with a chronic pulmonary fibrosis” Dr. Dawson said, explaining the rationale for the current study she presented during a poster session. Previous studies considered data for up to 5 years, she added, so the aim of the current study, therefore, was to look at the longer-term effect of methotrexate use on the incidence of pulmonary fibrosis.

Data on 129 patients who had started treatment with methotrexate from 2004 to 2007 were analyzed, of whom 63 (49%) had stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years. Most (82%) had been given methotrexate to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with other indications including inflammatory arthritis (5.4%) and psoriatic arthritis (4.7%).

“Practice was different 10 years ago, so just 56% of patients commenced methotrexate within the first year of the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Dawson reported.

Only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis were seen, all in the RA patients, and three of these were in patients who had started methotrexate over 1 year after their diagnosis. The incidence of 3.8% seen in the study matches the expected incidence of pulmonary fibrosis in RA and was actually “at the lower end of the expected incidence,” Dr. Dawson said. Previous studies have suggested an incidence rate of RA-associated interstitial lung disease of about 3%-7%.

All of the pulmonary fibrosis cases had occurred in men and 75% were seropositive for rheumatoid factor. The mean duration of RA at the time of onset of pulmonary fibrosis was 7.8 years and the usual interstitial pattern of fibrosis was seen. The 125 patients without pulmonary fibrosis had taken methotrexate for a mean of 8 years at a mean final weekly dose of 16.3 mg, compared with a mean of 6 years at a mean dose of 18.1 mg per week in the 4 patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

One of the next steps is to look at cases where methotrexate has been stopped and the effects of that on pulmonary fibrosis and disease activity. In Dr. Dawson’s experience, stopping methotrexate just affects the management of the arthritis and had no difference to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

If patients start to experience any lung symptoms while continuing methotrexate, such as shortness of breath, then they would need to be assessed and undergo lung function tests to monitor their condition. Treating the fibrosis using an antifibrotic drug, such as pirfenidone, is something that might be possible in the future, but this needs investigation in inflammatory arthritis as the drug is currently only licensed for use in idiopathic cases.

This is something the British Rheumatoid Interstitial Lung network plans to investigate in a placebo-controlled study of RA patients with fibrotic lung disease. “We’re looking to see if antifibrotic agents are going to slow the disease as it does in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is obviously quite exciting when it’s such a hard condition to treat,” said Dr. Dawson, who will be one of the study’s investigators.

Dr. Dawson had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Mewar was not involved in the study and had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Dawson J et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.470.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – A 10-year follow up of patients with inflammatory arthritis has shown that methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk of pulmonary fibrosis.

“As rheumatologists, it’s a really important message that methotrexate does not cause chronic pulmonary fibrosis and it should not be stopped because of pulmonary fibrosis,” Julie Dawson, MD, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. “It’s the rheumatoid arthritis. It’s not the methotrexate.”

Dr. Dawson, of St. Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, St. Helens, England, added that the current findings were consistent with her team’s prior research looking at earlier time periods. There was also no correlation between the duration or dose of methotrexate used and the development of the lung disease, she said.

“If anything, the suggestion is you’d be more symptomatic if you delay using methotrexate,” Dr. Dawson observed. If patients are not doing well on methotrexate, then perhaps adjusting therapy or changing to another drug would of course be the next step, but if patients are well controlled then “stopping it is the worst thing to do” for their arthritis, she said.

“This is of great clinical interest, and we can be reassured now about this, I think. This is really good, long-term data,” said Devesh Mewar, MD, of Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, Liverpool, England, who was not involved in the research.

“We know that methotrexate is associated with a pneumonitis reaction, but there is no high-quality evidence that methotrexate is associated with a chronic pulmonary fibrosis” Dr. Dawson said, explaining the rationale for the current study she presented during a poster session. Previous studies considered data for up to 5 years, she added, so the aim of the current study, therefore, was to look at the longer-term effect of methotrexate use on the incidence of pulmonary fibrosis.

Data on 129 patients who had started treatment with methotrexate from 2004 to 2007 were analyzed, of whom 63 (49%) had stayed on methotrexate for 10 or more years. Most (82%) had been given methotrexate to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with other indications including inflammatory arthritis (5.4%) and psoriatic arthritis (4.7%).

“Practice was different 10 years ago, so just 56% of patients commenced methotrexate within the first year of the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Dawson reported.

Only four cases of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis were seen, all in the RA patients, and three of these were in patients who had started methotrexate over 1 year after their diagnosis. The incidence of 3.8% seen in the study matches the expected incidence of pulmonary fibrosis in RA and was actually “at the lower end of the expected incidence,” Dr. Dawson said. Previous studies have suggested an incidence rate of RA-associated interstitial lung disease of about 3%-7%.

All of the pulmonary fibrosis cases had occurred in men and 75% were seropositive for rheumatoid factor. The mean duration of RA at the time of onset of pulmonary fibrosis was 7.8 years and the usual interstitial pattern of fibrosis was seen. The 125 patients without pulmonary fibrosis had taken methotrexate for a mean of 8 years at a mean final weekly dose of 16.3 mg, compared with a mean of 6 years at a mean dose of 18.1 mg per week in the 4 patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

One of the next steps is to look at cases where methotrexate has been stopped and the effects of that on pulmonary fibrosis and disease activity. In Dr. Dawson’s experience, stopping methotrexate just affects the management of the arthritis and had no difference to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

If patients start to experience any lung symptoms while continuing methotrexate, such as shortness of breath, then they would need to be assessed and undergo lung function tests to monitor their condition. Treating the fibrosis using an antifibrotic drug, such as pirfenidone, is something that might be possible in the future, but this needs investigation in inflammatory arthritis as the drug is currently only licensed for use in idiopathic cases.

This is something the British Rheumatoid Interstitial Lung network plans to investigate in a placebo-controlled study of RA patients with fibrotic lung disease. “We’re looking to see if antifibrotic agents are going to slow the disease as it does in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is obviously quite exciting when it’s such a hard condition to treat,” said Dr. Dawson, who will be one of the study’s investigators.

Dr. Dawson had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Mewar was not involved in the study and had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Dawson J et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.470.

REPORTING FROM RHEUMATOLOGY 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 10 years’ follow-up, four patients (3.1%) developed pulmonary fibrosis.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 129 patients with inflammatory arthritis treated with methotrexate for up to 10 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Dawson had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Mewar was not involved in the study and had nothing to disclose.

Source: Dawson J et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.470.

Family history of psoriasis and PsA predicts disease phenotype

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

REPORTING FROM SPARTAN 2018

Key clinical point: Family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis appear linked with disease phenotypes.

Major finding: Family history of PsA, compared with that of psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis.

Study details: Retrospective data from the poster session of SPARTAN 18

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the UCB Axial Fellowship Grant.

Psoriasis duration reflects cardiovascular event risk

KAUAI, HAWAII – The recent report that the risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event increases by 1% more than in the general population for each additional year of psoriasis duration is sobering news for physicians who treat pediatric psoriasis.

“If I have a 16-year-old who has a 5-year history of psoriasis, what does that mean for when she’s 30 or 40? And should we be intervening more aggressively?” Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, asked at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Even though there’s not a great deal of evidence, there’s some evidence to rationalize early screening in psoriasis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Psoriasis develops during childhood in almost one-third of patients.

The pediatric psoriasis screening guidelines describe a simple routine screening program and timeline for early identification of overweight or obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, inflammatory bowel disease, and quality of life issues, all of which are encountered with increased frequency in pediatric psoriasis patients. A fasting lipid panel is recommended in children aged 9-11 years with psoriasis and again at age 17-21 years.

“Don’t forget arthritis. For a kid with psoriasis, at every office visit, I ask about morning stiffness or limp. Those are probably the two most sensitive questions in screening for psoriatic arthritis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield.

It has been clear for some time that the skin is not the only organ affected by psoriatic inflammation. The study that quantified the relationship between psoriasis duration and cardiovascular risk – a 1% increase for each year of psoriasis – was a collaboration between investigators at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The two-part project included aortal imaging of 190 psoriasis patients using fludeoxyglucose F 18 PET/CT scan, which showed a strong relationship between duration of psoriasis and the degree of vascular inflammation. This was bolstered by a population-based study using Danish national registry data on 87,161 psoriasis patients and 4.2 million controls from the general Danish population (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:650-56.e3).

Dr. Eichenfield reported serving as a consultant to and/or recipient of research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – The recent report that the risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event increases by 1% more than in the general population for each additional year of psoriasis duration is sobering news for physicians who treat pediatric psoriasis.

“If I have a 16-year-old who has a 5-year history of psoriasis, what does that mean for when she’s 30 or 40? And should we be intervening more aggressively?” Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, asked at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Even though there’s not a great deal of evidence, there’s some evidence to rationalize early screening in psoriasis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Psoriasis develops during childhood in almost one-third of patients.

The pediatric psoriasis screening guidelines describe a simple routine screening program and timeline for early identification of overweight or obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, inflammatory bowel disease, and quality of life issues, all of which are encountered with increased frequency in pediatric psoriasis patients. A fasting lipid panel is recommended in children aged 9-11 years with psoriasis and again at age 17-21 years.

“Don’t forget arthritis. For a kid with psoriasis, at every office visit, I ask about morning stiffness or limp. Those are probably the two most sensitive questions in screening for psoriatic arthritis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield.

It has been clear for some time that the skin is not the only organ affected by psoriatic inflammation. The study that quantified the relationship between psoriasis duration and cardiovascular risk – a 1% increase for each year of psoriasis – was a collaboration between investigators at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The two-part project included aortal imaging of 190 psoriasis patients using fludeoxyglucose F 18 PET/CT scan, which showed a strong relationship between duration of psoriasis and the degree of vascular inflammation. This was bolstered by a population-based study using Danish national registry data on 87,161 psoriasis patients and 4.2 million controls from the general Danish population (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:650-56.e3).

Dr. Eichenfield reported serving as a consultant to and/or recipient of research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – The recent report that the risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event increases by 1% more than in the general population for each additional year of psoriasis duration is sobering news for physicians who treat pediatric psoriasis.

“If I have a 16-year-old who has a 5-year history of psoriasis, what does that mean for when she’s 30 or 40? And should we be intervening more aggressively?” Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, asked at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Even though there’s not a great deal of evidence, there’s some evidence to rationalize early screening in psoriasis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Psoriasis develops during childhood in almost one-third of patients.

The pediatric psoriasis screening guidelines describe a simple routine screening program and timeline for early identification of overweight or obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, inflammatory bowel disease, and quality of life issues, all of which are encountered with increased frequency in pediatric psoriasis patients. A fasting lipid panel is recommended in children aged 9-11 years with psoriasis and again at age 17-21 years.

“Don’t forget arthritis. For a kid with psoriasis, at every office visit, I ask about morning stiffness or limp. Those are probably the two most sensitive questions in screening for psoriatic arthritis,” according to Dr. Eichenfield.

It has been clear for some time that the skin is not the only organ affected by psoriatic inflammation. The study that quantified the relationship between psoriasis duration and cardiovascular risk – a 1% increase for each year of psoriasis – was a collaboration between investigators at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The two-part project included aortal imaging of 190 psoriasis patients using fludeoxyglucose F 18 PET/CT scan, which showed a strong relationship between duration of psoriasis and the degree of vascular inflammation. This was bolstered by a population-based study using Danish national registry data on 87,161 psoriasis patients and 4.2 million controls from the general Danish population (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:650-56.e3).

Dr. Eichenfield reported serving as a consultant to and/or recipient of research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

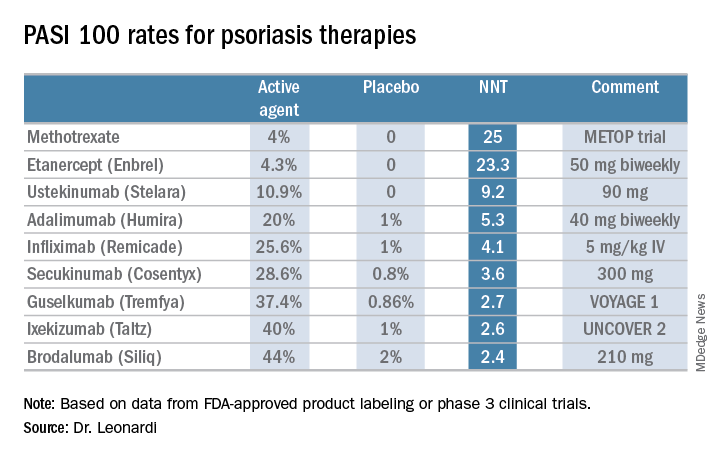

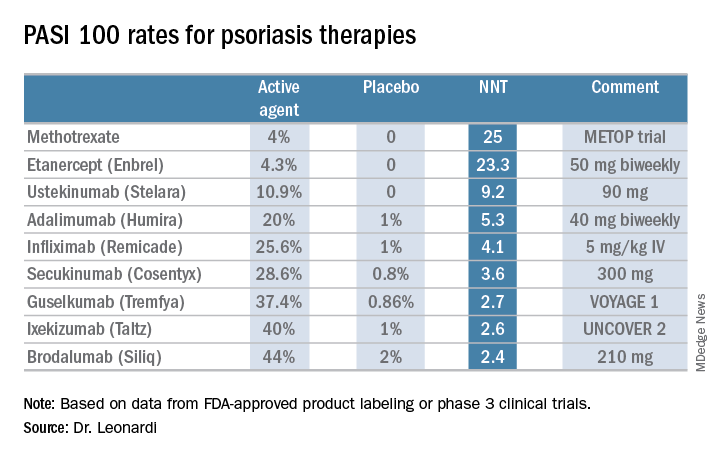

Is PASI 100 the new benchmark in psoriasis?

KAUAI, HAWAII – I think we should just do away with PASI 90 [90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score] and look at how well our drugs do against the metric of PASI 100. The whole ball of wax. Let’s just go for complete clearance,” Craig L. Leonardi, MD, declared in a provocative presentation at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Skin Disease Education Foundation/Global Academy for Medical Education.

He advocates using number needed to treat (NNT) as a performance yardstick. He finds it helpful in translating sometimes-arcane clinical trial results into useful information to guide everyday practice. The NNT is the average number of patients who need to be treated with a drug or procedure in order to achieve one additional good outcome, compared with a control intervention or placebo. It’s the inverse of the absolute risk reduction. The lower the NNT, the better an intervention is performing.

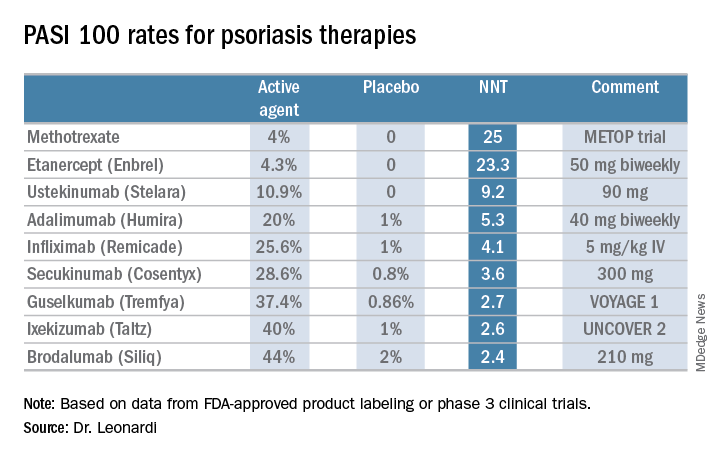

He presented a chart that summarized the NNTs to achieve a PASI 100 response for various systemic agents commonly used in treating moderate to severe psoriasis. He obtained the data from Food and Drug Administration–regulated product labeling and phase 3 clinical trials.

Dr. Leonardi drew attention to the worst performers on the list: methotrexate, with an NNT of 25 to achieve a PASI 100 response, and etanercept, with an NNT of 23.3.

“Methotrexate is a drug that the insurance industry says we have to flow through on our way to biologic drugs. But if complete clearance is your goal, this is an exercise in futility. These patients will never, ever get to complete clearance – or it’s at least very unlikely. We shouldn’t be asked to go through methotrexate on our way to anything. We shouldn’t be asked to use methotrexate at all. We should be bypassing it. And some of us are working on this,” he said.

Ustekinumab and adalimumab are the current market leaders in biologic therapy for psoriasis, but they don’t stack up so well when viewed through the filter of PASI 100 response, with NNTs of 9.2 and 5.3, respectively.

“These market leaders may not be the most relevant drugs in the current era,” according to the dermatologist.

In contrast, the high-performance biologics – the interleukin-17 inhibitors secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab and the interleukin-23 antagonist guselkumab – have impressively low NNTs of 2.4-3.6 in order to achieve complete clearance.

“But our IL-17 and IL-23 antagonists are markedly different from all other therapies, with NNTs of 1.3-1.1. With an NNT of 1.1, if you treated 11 patients with ixekizumab, 10 of them would achieve a PASI 75,” he explained.

“This is really quite remarkable,” Dr. Leonardi commented. “Our first drug back in 2002 was alefacept, and that drug was a ‘twenty-one percenter’: 21% of patients achieved a PASI 75. And quite frankly, we thought that was rocking voodoo science back in the day. Well, we’re really out there now. This is utterly amazing data: a PASI 75 of 81.6% for secukinumab, 86% for brodalumab, 90% for ixekizumab, and 91.2% for guselkumab. This is why we’re publishing this stuff in the best medical journals, because these results are absolutely amazing. So many different medical specialties are interested in what we’re doing with these drugs.”

He reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Pfizer, Sandoz, and UCB and receiving research funding from 21 pharmaceutical companies.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – I think we should just do away with PASI 90 [90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score] and look at how well our drugs do against the metric of PASI 100. The whole ball of wax. Let’s just go for complete clearance,” Craig L. Leonardi, MD, declared in a provocative presentation at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Skin Disease Education Foundation/Global Academy for Medical Education.

He advocates using number needed to treat (NNT) as a performance yardstick. He finds it helpful in translating sometimes-arcane clinical trial results into useful information to guide everyday practice. The NNT is the average number of patients who need to be treated with a drug or procedure in order to achieve one additional good outcome, compared with a control intervention or placebo. It’s the inverse of the absolute risk reduction. The lower the NNT, the better an intervention is performing.

He presented a chart that summarized the NNTs to achieve a PASI 100 response for various systemic agents commonly used in treating moderate to severe psoriasis. He obtained the data from Food and Drug Administration–regulated product labeling and phase 3 clinical trials.

Dr. Leonardi drew attention to the worst performers on the list: methotrexate, with an NNT of 25 to achieve a PASI 100 response, and etanercept, with an NNT of 23.3.

“Methotrexate is a drug that the insurance industry says we have to flow through on our way to biologic drugs. But if complete clearance is your goal, this is an exercise in futility. These patients will never, ever get to complete clearance – or it’s at least very unlikely. We shouldn’t be asked to go through methotrexate on our way to anything. We shouldn’t be asked to use methotrexate at all. We should be bypassing it. And some of us are working on this,” he said.

Ustekinumab and adalimumab are the current market leaders in biologic therapy for psoriasis, but they don’t stack up so well when viewed through the filter of PASI 100 response, with NNTs of 9.2 and 5.3, respectively.

“These market leaders may not be the most relevant drugs in the current era,” according to the dermatologist.

In contrast, the high-performance biologics – the interleukin-17 inhibitors secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab and the interleukin-23 antagonist guselkumab – have impressively low NNTs of 2.4-3.6 in order to achieve complete clearance.

“But our IL-17 and IL-23 antagonists are markedly different from all other therapies, with NNTs of 1.3-1.1. With an NNT of 1.1, if you treated 11 patients with ixekizumab, 10 of them would achieve a PASI 75,” he explained.

“This is really quite remarkable,” Dr. Leonardi commented. “Our first drug back in 2002 was alefacept, and that drug was a ‘twenty-one percenter’: 21% of patients achieved a PASI 75. And quite frankly, we thought that was rocking voodoo science back in the day. Well, we’re really out there now. This is utterly amazing data: a PASI 75 of 81.6% for secukinumab, 86% for brodalumab, 90% for ixekizumab, and 91.2% for guselkumab. This is why we’re publishing this stuff in the best medical journals, because these results are absolutely amazing. So many different medical specialties are interested in what we’re doing with these drugs.”

He reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Pfizer, Sandoz, and UCB and receiving research funding from 21 pharmaceutical companies.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – I think we should just do away with PASI 90 [90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score] and look at how well our drugs do against the metric of PASI 100. The whole ball of wax. Let’s just go for complete clearance,” Craig L. Leonardi, MD, declared in a provocative presentation at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Skin Disease Education Foundation/Global Academy for Medical Education.

He advocates using number needed to treat (NNT) as a performance yardstick. He finds it helpful in translating sometimes-arcane clinical trial results into useful information to guide everyday practice. The NNT is the average number of patients who need to be treated with a drug or procedure in order to achieve one additional good outcome, compared with a control intervention or placebo. It’s the inverse of the absolute risk reduction. The lower the NNT, the better an intervention is performing.

He presented a chart that summarized the NNTs to achieve a PASI 100 response for various systemic agents commonly used in treating moderate to severe psoriasis. He obtained the data from Food and Drug Administration–regulated product labeling and phase 3 clinical trials.

Dr. Leonardi drew attention to the worst performers on the list: methotrexate, with an NNT of 25 to achieve a PASI 100 response, and etanercept, with an NNT of 23.3.

“Methotrexate is a drug that the insurance industry says we have to flow through on our way to biologic drugs. But if complete clearance is your goal, this is an exercise in futility. These patients will never, ever get to complete clearance – or it’s at least very unlikely. We shouldn’t be asked to go through methotrexate on our way to anything. We shouldn’t be asked to use methotrexate at all. We should be bypassing it. And some of us are working on this,” he said.

Ustekinumab and adalimumab are the current market leaders in biologic therapy for psoriasis, but they don’t stack up so well when viewed through the filter of PASI 100 response, with NNTs of 9.2 and 5.3, respectively.

“These market leaders may not be the most relevant drugs in the current era,” according to the dermatologist.

In contrast, the high-performance biologics – the interleukin-17 inhibitors secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab and the interleukin-23 antagonist guselkumab – have impressively low NNTs of 2.4-3.6 in order to achieve complete clearance.

“But our IL-17 and IL-23 antagonists are markedly different from all other therapies, with NNTs of 1.3-1.1. With an NNT of 1.1, if you treated 11 patients with ixekizumab, 10 of them would achieve a PASI 75,” he explained.

“This is really quite remarkable,” Dr. Leonardi commented. “Our first drug back in 2002 was alefacept, and that drug was a ‘twenty-one percenter’: 21% of patients achieved a PASI 75. And quite frankly, we thought that was rocking voodoo science back in the day. Well, we’re really out there now. This is utterly amazing data: a PASI 75 of 81.6% for secukinumab, 86% for brodalumab, 90% for ixekizumab, and 91.2% for guselkumab. This is why we’re publishing this stuff in the best medical journals, because these results are absolutely amazing. So many different medical specialties are interested in what we’re doing with these drugs.”

He reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Pfizer, Sandoz, and UCB and receiving research funding from 21 pharmaceutical companies.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

MACE risk similar across arthritis subtypes

Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis were linked to similarly increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events in a large population-based cohort study.

Inflammation itself drives this relationship and “adequate control of disease activity is needed to lower cardiovascular risk,” wrote Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, and her coinvestigators.

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) also were significantly associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, “stressing the importance of [their] detection and management,” the researchers wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

Previous studies linked inflammatory arthritis to a 40%-50% increase in risk of cardiovascular events, such as MI and acute coronary syndrome. Inflammatory arthritis also increases the risk of cerebrovascular disease, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors alone do not explain these associations, the researchers noted. Mounting data suggest that inflammation underlies the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Other studies have documented the cardioprotective effect of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.

Dr. Lauper and her coinvestigators examined the prevalence and incidence of MACE, including MI, transient or permanent cerebrovascular events, or cardiovascular deaths among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or spondyloarthritis. The 5,315 patients in the study were part of the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry, which longitudinally tracks individuals throughout Switzerland who receive biologic DMARDs.

The investigators also asked rheumatologists to supply missing data and used a questionnaire to survey patients about cardiovascular events and associated risk factors. These efforts produced more than 66,000 patient-years of follow-up data, more than half of which were for rheumatoid arthritis and less than 10,000 of which were for psoriatic arthritis.

For every 1,000 patient-years, there were 2.7 MACE for rheumatoid arthritis, 1.4 MACE for axial spondyloarthritis, and 1.4 MACE for psoriatic arthritis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis tended to be older, which explained most of their excess risk of MACE, the researchers said. Controlling for age only, MACE incidence rate ratios were 1.16 for spondyloarthritis (P = .52) and 0.75 for psoriatic arthritis (P = .34).

The analysis of prevalent MACE included more than 5,000 patients. Nonfatal MACE had affected 4.8% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 2.2% of patients with axial spondyloarthritis, and 2.9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis (P less than .001). Once again, differences among groups were not significant after researchers controlled for the older age of the rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Among all patients, independent risk factors for MACE included older age (P less than .001), disease duration (P = .002), male gender (P less than .001), family history of MACE (P = .03), personal history of hyperlipidemia (P less than .001), and hypertension (P = .04). In contrast, there was no link between MACE and use of NSAIDs. “Similarly, a recent Taiwanese nationwide study did not find an increase in coronary disease in patients taking etoricoxib or celecoxib after adjustment for gender, age, comorbidities, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and DMARDs,” the researchers wrote.Dr. Lauper reported having no conflicts of interest. The senior author and two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Roche, Abbvie, Pfizer, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lauper K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.23567.

Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis were linked to similarly increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events in a large population-based cohort study.

Inflammation itself drives this relationship and “adequate control of disease activity is needed to lower cardiovascular risk,” wrote Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, and her coinvestigators.

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) also were significantly associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, “stressing the importance of [their] detection and management,” the researchers wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

Previous studies linked inflammatory arthritis to a 40%-50% increase in risk of cardiovascular events, such as MI and acute coronary syndrome. Inflammatory arthritis also increases the risk of cerebrovascular disease, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors alone do not explain these associations, the researchers noted. Mounting data suggest that inflammation underlies the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Other studies have documented the cardioprotective effect of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.

Dr. Lauper and her coinvestigators examined the prevalence and incidence of MACE, including MI, transient or permanent cerebrovascular events, or cardiovascular deaths among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or spondyloarthritis. The 5,315 patients in the study were part of the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry, which longitudinally tracks individuals throughout Switzerland who receive biologic DMARDs.

The investigators also asked rheumatologists to supply missing data and used a questionnaire to survey patients about cardiovascular events and associated risk factors. These efforts produced more than 66,000 patient-years of follow-up data, more than half of which were for rheumatoid arthritis and less than 10,000 of which were for psoriatic arthritis.

For every 1,000 patient-years, there were 2.7 MACE for rheumatoid arthritis, 1.4 MACE for axial spondyloarthritis, and 1.4 MACE for psoriatic arthritis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis tended to be older, which explained most of their excess risk of MACE, the researchers said. Controlling for age only, MACE incidence rate ratios were 1.16 for spondyloarthritis (P = .52) and 0.75 for psoriatic arthritis (P = .34).

The analysis of prevalent MACE included more than 5,000 patients. Nonfatal MACE had affected 4.8% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 2.2% of patients with axial spondyloarthritis, and 2.9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis (P less than .001). Once again, differences among groups were not significant after researchers controlled for the older age of the rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Among all patients, independent risk factors for MACE included older age (P less than .001), disease duration (P = .002), male gender (P less than .001), family history of MACE (P = .03), personal history of hyperlipidemia (P less than .001), and hypertension (P = .04). In contrast, there was no link between MACE and use of NSAIDs. “Similarly, a recent Taiwanese nationwide study did not find an increase in coronary disease in patients taking etoricoxib or celecoxib after adjustment for gender, age, comorbidities, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and DMARDs,” the researchers wrote.Dr. Lauper reported having no conflicts of interest. The senior author and two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Roche, Abbvie, Pfizer, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lauper K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.23567.

Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis were linked to similarly increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events in a large population-based cohort study.

Inflammation itself drives this relationship and “adequate control of disease activity is needed to lower cardiovascular risk,” wrote Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, and her coinvestigators.

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) also were significantly associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, “stressing the importance of [their] detection and management,” the researchers wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

Previous studies linked inflammatory arthritis to a 40%-50% increase in risk of cardiovascular events, such as MI and acute coronary syndrome. Inflammatory arthritis also increases the risk of cerebrovascular disease, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors alone do not explain these associations, the researchers noted. Mounting data suggest that inflammation underlies the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Other studies have documented the cardioprotective effect of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.

Dr. Lauper and her coinvestigators examined the prevalence and incidence of MACE, including MI, transient or permanent cerebrovascular events, or cardiovascular deaths among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or spondyloarthritis. The 5,315 patients in the study were part of the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry, which longitudinally tracks individuals throughout Switzerland who receive biologic DMARDs.

The investigators also asked rheumatologists to supply missing data and used a questionnaire to survey patients about cardiovascular events and associated risk factors. These efforts produced more than 66,000 patient-years of follow-up data, more than half of which were for rheumatoid arthritis and less than 10,000 of which were for psoriatic arthritis.

For every 1,000 patient-years, there were 2.7 MACE for rheumatoid arthritis, 1.4 MACE for axial spondyloarthritis, and 1.4 MACE for psoriatic arthritis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis tended to be older, which explained most of their excess risk of MACE, the researchers said. Controlling for age only, MACE incidence rate ratios were 1.16 for spondyloarthritis (P = .52) and 0.75 for psoriatic arthritis (P = .34).

The analysis of prevalent MACE included more than 5,000 patients. Nonfatal MACE had affected 4.8% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 2.2% of patients with axial spondyloarthritis, and 2.9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis (P less than .001). Once again, differences among groups were not significant after researchers controlled for the older age of the rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Among all patients, independent risk factors for MACE included older age (P less than .001), disease duration (P = .002), male gender (P less than .001), family history of MACE (P = .03), personal history of hyperlipidemia (P less than .001), and hypertension (P = .04). In contrast, there was no link between MACE and use of NSAIDs. “Similarly, a recent Taiwanese nationwide study did not find an increase in coronary disease in patients taking etoricoxib or celecoxib after adjustment for gender, age, comorbidities, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and DMARDs,” the researchers wrote.Dr. Lauper reported having no conflicts of interest. The senior author and two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Roche, Abbvie, Pfizer, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lauper K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.23567.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was similar for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis.

Major finding: For every 1,000 patient-years, there were 2.7 MACE for rheumatoid arthritis, 1.4 MACE for axial spondyloarthritis, and 1.4 MACE for psoriatic arthritis. The older age of patients with rheumatoid arthritis explained most of their elevated absolute risk.

Study details: Population-based cohort study of 5,315 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lauper reported having no conflicts of interest. The senior author and two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Roche, Abbvie, Pfizer, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Lauper K et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.23567.

How to avoid severe diarrhea from apremilast

KAUAI, HAWAII – Physicians have become much more cognizant of severe diarrhea and nausea as potential side effects of apremilast since the Food and Drug Administration–approved change in the warnings and precautions section of the drug’s labeling in June 2017. Jashin J. Wu, MD, director of the psoriasis clinic at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, has a tip for avoiding these problems: Delay up-titrating.

“In my opinion, that may be too quick of an up-titration. I tell patients that, if they feel the GI issues are still a problem for them on day 6, they should take 30 mg just once a day for the first 1-2 months. After that we’ll see how they’re doing, and if they feel they can make the jump to twice a day, then they can go for it. Of course, I also tell them that maybe their psoriasis will not clear as well as if they’d been on apremilast twice a day right from day 6, but if they’re able to tolerate it and can continue to take it, they can improve while they’re on it,” the dermatologist said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dr. Wu presented an update on recent developments regarding the newest oral drugs for psoriasis and one of the oldest: apremilast and methotrexate, respectively.

Apremilast

The revised warning label highlighting the risks of severe diarrhea and nausea associated with the oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor says that most such events have occurred within the first few weeks of therapy. The guidance also notes that patients who reduced the dosage or discontinued treatment outright generally improved rapidly.

“I see this in a lot of my patients. They have to go to the bathroom pretty often. It’s actually unusual for me for a patient not to have any GI issues at all,” according to Dr. Wu.

He shared a number of other fresh insights into apremilast’s safety and efficacy derived from recent studies.

Efficacy appears to increase at least out to 1 year