User login

AGA: Biopsy normal gastric mucosa for H. pylori during esophagogastroduodenoscopy

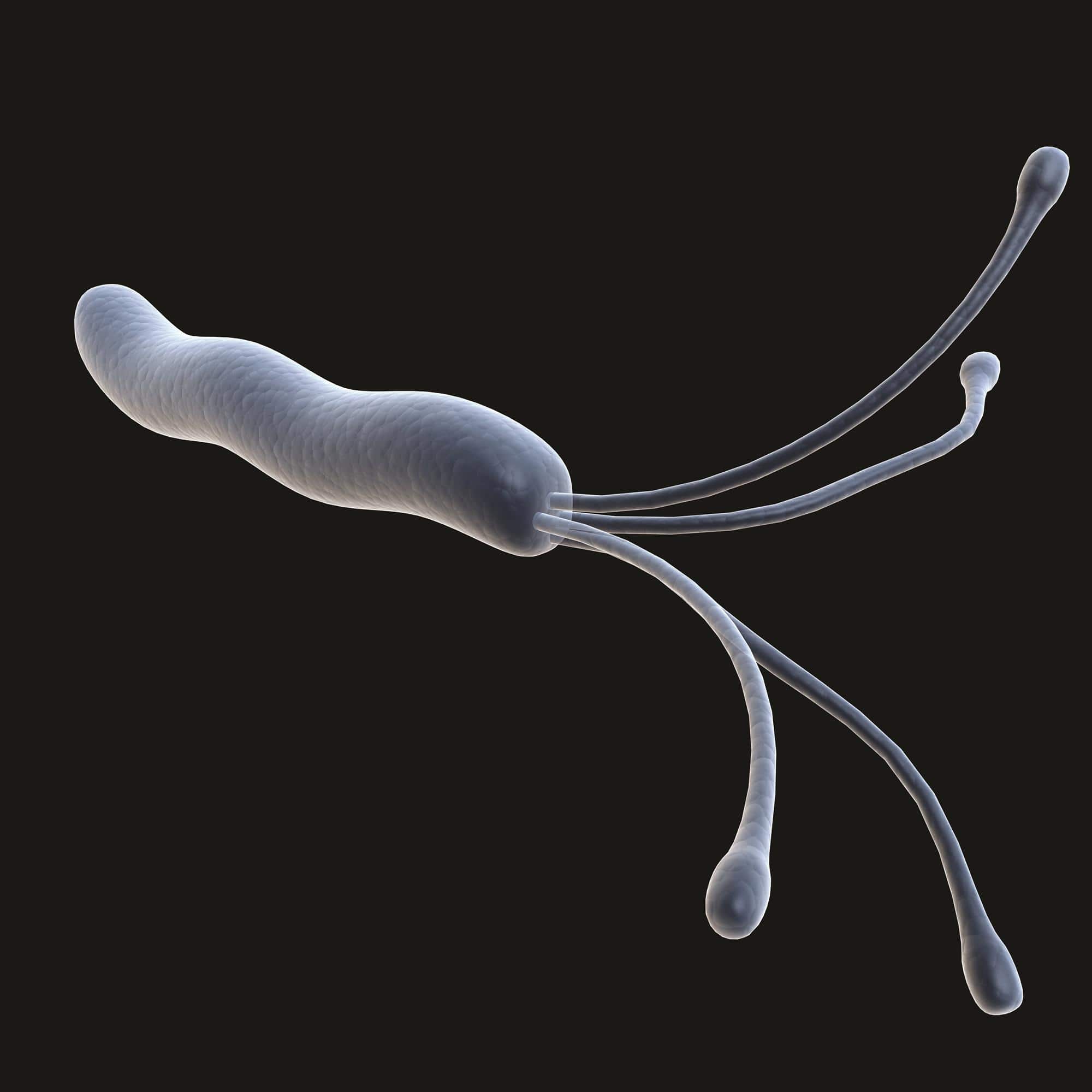

Obtain gastric biopsies to check for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients undergoing routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dyspepsia, even if their mucosa appears normal and they’re immunocompetent, the American Gastroenterological Association advises in a new guideline for upper gastrointestinal biopsy to evaluate dyspepsia in the adult patient in the absence of visible mucosal lesions, which was published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

The group suggests taking five biopsy specimens from the gastric body and antrum using the updated Sydney System; placing the samples in the same jar; and relying on routine staining to make the call. “Experienced GI pathologists can determine the anatomic location of biopsy specimens sent from the stomach, which obviates the need for” – and cost of – “separating specimens into multiple jars.” They can also identify “virtually all cases of H. pylori .... Therefore, routine use of ancillary special staining” needlessly adds cost, said the guideline authors, led by Dr. Yu-Xiao Yang of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.039).

The group also counsels against routine biopsies of normal-appearing esophagus and gastroesophageal junctions in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for dyspepsia, regardless of their immune status.

It does recommend biopsies of normal-appearing duodenum in immunocompromised patients to check for opportunistic infections and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplant, but counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia if signs and symptoms of celiac disease are absent. Again, routine use of special staining isn’t necessary. “Studies using [hematoxylin and eosin] counting methods show similar results as those obtained using CD3 [T-cell marker] stains,” the authors wrote.

The purpose of the guideline is to establish evidence-based standards for biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa in the upper gastrointestinal tract. No such standards existed until now, so “there [is] likely wide practice variation in whether or not such biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa are obtained,” they said.

The advice is based on a thorough review of the medical literature, and a grading of its strength. The guideline is meant for adult patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia, and assumes that endoscopic biopsy has negligible complications.

The esophageal biopsy recommendations are strong, meaning that “most individuals should receive the recommended course of action.” The gastric biopsy advice is a mix of both strong and conditional recommendations, while the duodenal biopsy recommendations are conditional. Evidence for each recommendation ranged from very low to moderate.

Regarding gastric biopsy, H. pylori can lurk in normal-looking mucosa, and evidence supports detection and treatment for both symptom relief and cancer risk reduction. In the immunocompromised, gastric biopsies can also help detect cytomegalovirus infection.

The five-biopsy Sydney System gathers specimens from the lesser and greater curve of the gastric antrum, lesser curvature of the corpus, middle portion of the greater curvature of the corpus, and the incisura angularis. The thorough approach probably detects H. pylori missed by a three-biopsy method, with little added cost.

Esophageal biopsies of normal mucosa aren’t necessary, the authors said, because “although a number of microscopic changes in the esophageal mucosa can be seen in patients with” gastroesophageal reflux disease, they aren’t much help in distinguishing it from heartburn or even healthy controls. For immune compromised patients, GVHD is more likely to show up at other sites, such as the duodenum.

Although the group counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients, it did note that “if the suspicion of celiac disease is high, biopsies of the normal-appearing duodenum may be of value even if serologies ... are negative.”

Funding source and disclosures for the work are available from AGA.

Obtain gastric biopsies to check for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients undergoing routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dyspepsia, even if their mucosa appears normal and they’re immunocompetent, the American Gastroenterological Association advises in a new guideline for upper gastrointestinal biopsy to evaluate dyspepsia in the adult patient in the absence of visible mucosal lesions, which was published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

The group suggests taking five biopsy specimens from the gastric body and antrum using the updated Sydney System; placing the samples in the same jar; and relying on routine staining to make the call. “Experienced GI pathologists can determine the anatomic location of biopsy specimens sent from the stomach, which obviates the need for” – and cost of – “separating specimens into multiple jars.” They can also identify “virtually all cases of H. pylori .... Therefore, routine use of ancillary special staining” needlessly adds cost, said the guideline authors, led by Dr. Yu-Xiao Yang of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.039).

The group also counsels against routine biopsies of normal-appearing esophagus and gastroesophageal junctions in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for dyspepsia, regardless of their immune status.

It does recommend biopsies of normal-appearing duodenum in immunocompromised patients to check for opportunistic infections and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplant, but counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia if signs and symptoms of celiac disease are absent. Again, routine use of special staining isn’t necessary. “Studies using [hematoxylin and eosin] counting methods show similar results as those obtained using CD3 [T-cell marker] stains,” the authors wrote.

The purpose of the guideline is to establish evidence-based standards for biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa in the upper gastrointestinal tract. No such standards existed until now, so “there [is] likely wide practice variation in whether or not such biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa are obtained,” they said.

The advice is based on a thorough review of the medical literature, and a grading of its strength. The guideline is meant for adult patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia, and assumes that endoscopic biopsy has negligible complications.

The esophageal biopsy recommendations are strong, meaning that “most individuals should receive the recommended course of action.” The gastric biopsy advice is a mix of both strong and conditional recommendations, while the duodenal biopsy recommendations are conditional. Evidence for each recommendation ranged from very low to moderate.

Regarding gastric biopsy, H. pylori can lurk in normal-looking mucosa, and evidence supports detection and treatment for both symptom relief and cancer risk reduction. In the immunocompromised, gastric biopsies can also help detect cytomegalovirus infection.

The five-biopsy Sydney System gathers specimens from the lesser and greater curve of the gastric antrum, lesser curvature of the corpus, middle portion of the greater curvature of the corpus, and the incisura angularis. The thorough approach probably detects H. pylori missed by a three-biopsy method, with little added cost.

Esophageal biopsies of normal mucosa aren’t necessary, the authors said, because “although a number of microscopic changes in the esophageal mucosa can be seen in patients with” gastroesophageal reflux disease, they aren’t much help in distinguishing it from heartburn or even healthy controls. For immune compromised patients, GVHD is more likely to show up at other sites, such as the duodenum.

Although the group counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients, it did note that “if the suspicion of celiac disease is high, biopsies of the normal-appearing duodenum may be of value even if serologies ... are negative.”

Funding source and disclosures for the work are available from AGA.

Obtain gastric biopsies to check for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients undergoing routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dyspepsia, even if their mucosa appears normal and they’re immunocompetent, the American Gastroenterological Association advises in a new guideline for upper gastrointestinal biopsy to evaluate dyspepsia in the adult patient in the absence of visible mucosal lesions, which was published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

The group suggests taking five biopsy specimens from the gastric body and antrum using the updated Sydney System; placing the samples in the same jar; and relying on routine staining to make the call. “Experienced GI pathologists can determine the anatomic location of biopsy specimens sent from the stomach, which obviates the need for” – and cost of – “separating specimens into multiple jars.” They can also identify “virtually all cases of H. pylori .... Therefore, routine use of ancillary special staining” needlessly adds cost, said the guideline authors, led by Dr. Yu-Xiao Yang of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.039).

The group also counsels against routine biopsies of normal-appearing esophagus and gastroesophageal junctions in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for dyspepsia, regardless of their immune status.

It does recommend biopsies of normal-appearing duodenum in immunocompromised patients to check for opportunistic infections and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplant, but counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia if signs and symptoms of celiac disease are absent. Again, routine use of special staining isn’t necessary. “Studies using [hematoxylin and eosin] counting methods show similar results as those obtained using CD3 [T-cell marker] stains,” the authors wrote.

The purpose of the guideline is to establish evidence-based standards for biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa in the upper gastrointestinal tract. No such standards existed until now, so “there [is] likely wide practice variation in whether or not such biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa are obtained,” they said.

The advice is based on a thorough review of the medical literature, and a grading of its strength. The guideline is meant for adult patients undergoing EGD solely for dyspepsia, and assumes that endoscopic biopsy has negligible complications.

The esophageal biopsy recommendations are strong, meaning that “most individuals should receive the recommended course of action.” The gastric biopsy advice is a mix of both strong and conditional recommendations, while the duodenal biopsy recommendations are conditional. Evidence for each recommendation ranged from very low to moderate.

Regarding gastric biopsy, H. pylori can lurk in normal-looking mucosa, and evidence supports detection and treatment for both symptom relief and cancer risk reduction. In the immunocompromised, gastric biopsies can also help detect cytomegalovirus infection.

The five-biopsy Sydney System gathers specimens from the lesser and greater curve of the gastric antrum, lesser curvature of the corpus, middle portion of the greater curvature of the corpus, and the incisura angularis. The thorough approach probably detects H. pylori missed by a three-biopsy method, with little added cost.

Esophageal biopsies of normal mucosa aren’t necessary, the authors said, because “although a number of microscopic changes in the esophageal mucosa can be seen in patients with” gastroesophageal reflux disease, they aren’t much help in distinguishing it from heartburn or even healthy controls. For immune compromised patients, GVHD is more likely to show up at other sites, such as the duodenum.

Although the group counsels against routine duodenum biopsies in immunocompetent patients, it did note that “if the suspicion of celiac disease is high, biopsies of the normal-appearing duodenum may be of value even if serologies ... are negative.”

Funding source and disclosures for the work are available from AGA.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Hepatitis C drove steep rises in cirrhosis, HCC, and related deaths

Cirrhosis nearly doubled among Veterans Affairs patients between 2001 and 2013, while cirrhosis-related mortality rose by about 50% and deaths from hepatocellular carcinoma almost tripled, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

Hepatitis C virus infection was “the overwhelming driver of these trends, with smaller contributions from alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other liver diseases,” said Dr. Lauren Beste of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates. Based on their data, the prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States will peak in 2021, they said. “In contrast, the incidence of HCC continues to increase, confirming worrisome predictions of rapid growth put forward by work (Gastroenterology. 2010;138[2]:513-21) conducted” in the early 2000s.

New HCV infections have dropped sharply in the United States since about 1990, but cases of HCV-related cirrhosis and HCC continue to rise as chronically infected patients age and their liver disease progresses. Although the burden of cirrhosis and HCC due to HCV infection is expected to peak in about the year 2020, the population-level effects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis B virus infection remained unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they retrospectively studied underlying etiologies among a national cohort of almost 130,000 Veterans Affairs patients with cirrhosis and more than 21,000 patients with HCC between 2001 and 2013 (Gastroenterology 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056).

In 2013, the VA cared for more than 5.7 million patients, including about 1% with cirrhosis and 0.13% with HCC. Between 2001 and 2013, the prevalence of cirrhosis almost doubled, rising from 664 to 1,058 cases for every 100,000 patients. Deaths among cirrhotic patients also increased by about half, rising from 83 to 126 for every 100,000 patient-years. These liver-related deaths were mainly caused by HCC, whose incidence rose about 2.5 times from 17 to 45 per 100,000 patient-years, Dr. Beste and her associates reported.

Notably, deaths due to liver cancer rose threefold – from 13 to 37 per 100,000 patient-years between 2001 and 2013, “driven overwhelmingly by HCV with much smaller contributions from NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease,” said the researchers. By 2013, almost half of cirrhosis cases and related deaths occurred among HCV-infected patients, as did 67% of HCC cases and related deaths, they noted.

About 60% of patients with cirrhosis and HCV infection also had a longstanding history of alcohol use, the researchers noted. Addressing both factors, as well as diabetes, obesity, and other drivers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, could help ease the national burden of liver disease and liver-related mortality among U.S. veterans and other groups, they added. “The increasing burden of cirrhosis and HCC highlights the need for greater efforts to address their causes at a population level,” Dr. Beste and her associates wrote. “Health care systems will need to accommodate rising numbers of patients with cirrhosis and HCC.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Health Administration funded the study. The investigators declared no competing interests.

Despite recent advances in hepatitis C virus treatment, many infected patients have preexisting liver fibrosis that puts them at risk for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Meanwhile, risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are increasingly prevalent. In this study, the investigators sought to understand the contribution of liver disease etiology to trends in adverse liver outcomes (the prevalence, incidence, and mortality of cirrhosis and HCC). They identified all VA health care users from 2001 to 2013 with diagnoses of cirrhosis (n = 129,998) or HCC (n = 21,326) and their liver disease etiology, and compared outcomes by calendar year.

|

Dr. Barry Schlansky |

Over the study period, marked increases in cirrhosis prevalence (59%), cirrhosis mortality (52%), HCC incidence (164%), and HCC mortality (185%) were observed in this national VA cohort. The increasing prevalence of cirrhosis was mainly driven by increasing contributions from HCV or NAFLD liver disease, but rises in mortality from cirrhosis and both incidence and mortality from HCC were almost entirely due to HCV. Based on these trends, the researchers forecasted that the prevalence of cirrhosis will plateau and begin to decline in 2021 (2020 in the HCV subgroup), but rates of HCC will continue to surge.

Although these results differ from two recent analyses of the national cancer surveillance registry (SEER) that found decelerations in HCC incidence and mortality in recent years, the current study included methodologic features (stratification by liver disease etiology and absence of age standardization) that likely facilitated more accurate estimates of HCC incidence and mortality. The generalizability of VA data to the general population is always debated (the former is nearly exclusively men with a higher prevalence of HCV infection and other liver disease risk factors, all of whom have access to medical care), yet the researchers rightly note that the time trends in cirrhosis and HCC outcomes (rather than absolute numbers) are still applicable to the non-VA population, particularly men. This study highlights the dramatic rise in cirrhosis and HCC, and associated deaths from these conditions, over the last decade. In addition to aggressive treatment of the underlying cause of liver disease, meaningful reductions in the burden of advanced liver disease will require a renewed focus on measures to improve adherence with maintenance care for cirrhotic patients, especially liver cancer screening.

Dr. Barry Schlansky is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He has no conflicts of interest.

Despite recent advances in hepatitis C virus treatment, many infected patients have preexisting liver fibrosis that puts them at risk for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Meanwhile, risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are increasingly prevalent. In this study, the investigators sought to understand the contribution of liver disease etiology to trends in adverse liver outcomes (the prevalence, incidence, and mortality of cirrhosis and HCC). They identified all VA health care users from 2001 to 2013 with diagnoses of cirrhosis (n = 129,998) or HCC (n = 21,326) and their liver disease etiology, and compared outcomes by calendar year.

|

Dr. Barry Schlansky |

Over the study period, marked increases in cirrhosis prevalence (59%), cirrhosis mortality (52%), HCC incidence (164%), and HCC mortality (185%) were observed in this national VA cohort. The increasing prevalence of cirrhosis was mainly driven by increasing contributions from HCV or NAFLD liver disease, but rises in mortality from cirrhosis and both incidence and mortality from HCC were almost entirely due to HCV. Based on these trends, the researchers forecasted that the prevalence of cirrhosis will plateau and begin to decline in 2021 (2020 in the HCV subgroup), but rates of HCC will continue to surge.

Although these results differ from two recent analyses of the national cancer surveillance registry (SEER) that found decelerations in HCC incidence and mortality in recent years, the current study included methodologic features (stratification by liver disease etiology and absence of age standardization) that likely facilitated more accurate estimates of HCC incidence and mortality. The generalizability of VA data to the general population is always debated (the former is nearly exclusively men with a higher prevalence of HCV infection and other liver disease risk factors, all of whom have access to medical care), yet the researchers rightly note that the time trends in cirrhosis and HCC outcomes (rather than absolute numbers) are still applicable to the non-VA population, particularly men. This study highlights the dramatic rise in cirrhosis and HCC, and associated deaths from these conditions, over the last decade. In addition to aggressive treatment of the underlying cause of liver disease, meaningful reductions in the burden of advanced liver disease will require a renewed focus on measures to improve adherence with maintenance care for cirrhotic patients, especially liver cancer screening.

Dr. Barry Schlansky is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He has no conflicts of interest.

Despite recent advances in hepatitis C virus treatment, many infected patients have preexisting liver fibrosis that puts them at risk for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Meanwhile, risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are increasingly prevalent. In this study, the investigators sought to understand the contribution of liver disease etiology to trends in adverse liver outcomes (the prevalence, incidence, and mortality of cirrhosis and HCC). They identified all VA health care users from 2001 to 2013 with diagnoses of cirrhosis (n = 129,998) or HCC (n = 21,326) and their liver disease etiology, and compared outcomes by calendar year.

|

Dr. Barry Schlansky |

Over the study period, marked increases in cirrhosis prevalence (59%), cirrhosis mortality (52%), HCC incidence (164%), and HCC mortality (185%) were observed in this national VA cohort. The increasing prevalence of cirrhosis was mainly driven by increasing contributions from HCV or NAFLD liver disease, but rises in mortality from cirrhosis and both incidence and mortality from HCC were almost entirely due to HCV. Based on these trends, the researchers forecasted that the prevalence of cirrhosis will plateau and begin to decline in 2021 (2020 in the HCV subgroup), but rates of HCC will continue to surge.

Although these results differ from two recent analyses of the national cancer surveillance registry (SEER) that found decelerations in HCC incidence and mortality in recent years, the current study included methodologic features (stratification by liver disease etiology and absence of age standardization) that likely facilitated more accurate estimates of HCC incidence and mortality. The generalizability of VA data to the general population is always debated (the former is nearly exclusively men with a higher prevalence of HCV infection and other liver disease risk factors, all of whom have access to medical care), yet the researchers rightly note that the time trends in cirrhosis and HCC outcomes (rather than absolute numbers) are still applicable to the non-VA population, particularly men. This study highlights the dramatic rise in cirrhosis and HCC, and associated deaths from these conditions, over the last decade. In addition to aggressive treatment of the underlying cause of liver disease, meaningful reductions in the burden of advanced liver disease will require a renewed focus on measures to improve adherence with maintenance care for cirrhotic patients, especially liver cancer screening.

Dr. Barry Schlansky is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He has no conflicts of interest.

Cirrhosis nearly doubled among Veterans Affairs patients between 2001 and 2013, while cirrhosis-related mortality rose by about 50% and deaths from hepatocellular carcinoma almost tripled, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

Hepatitis C virus infection was “the overwhelming driver of these trends, with smaller contributions from alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other liver diseases,” said Dr. Lauren Beste of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates. Based on their data, the prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States will peak in 2021, they said. “In contrast, the incidence of HCC continues to increase, confirming worrisome predictions of rapid growth put forward by work (Gastroenterology. 2010;138[2]:513-21) conducted” in the early 2000s.

New HCV infections have dropped sharply in the United States since about 1990, but cases of HCV-related cirrhosis and HCC continue to rise as chronically infected patients age and their liver disease progresses. Although the burden of cirrhosis and HCC due to HCV infection is expected to peak in about the year 2020, the population-level effects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis B virus infection remained unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they retrospectively studied underlying etiologies among a national cohort of almost 130,000 Veterans Affairs patients with cirrhosis and more than 21,000 patients with HCC between 2001 and 2013 (Gastroenterology 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056).

In 2013, the VA cared for more than 5.7 million patients, including about 1% with cirrhosis and 0.13% with HCC. Between 2001 and 2013, the prevalence of cirrhosis almost doubled, rising from 664 to 1,058 cases for every 100,000 patients. Deaths among cirrhotic patients also increased by about half, rising from 83 to 126 for every 100,000 patient-years. These liver-related deaths were mainly caused by HCC, whose incidence rose about 2.5 times from 17 to 45 per 100,000 patient-years, Dr. Beste and her associates reported.

Notably, deaths due to liver cancer rose threefold – from 13 to 37 per 100,000 patient-years between 2001 and 2013, “driven overwhelmingly by HCV with much smaller contributions from NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease,” said the researchers. By 2013, almost half of cirrhosis cases and related deaths occurred among HCV-infected patients, as did 67% of HCC cases and related deaths, they noted.

About 60% of patients with cirrhosis and HCV infection also had a longstanding history of alcohol use, the researchers noted. Addressing both factors, as well as diabetes, obesity, and other drivers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, could help ease the national burden of liver disease and liver-related mortality among U.S. veterans and other groups, they added. “The increasing burden of cirrhosis and HCC highlights the need for greater efforts to address their causes at a population level,” Dr. Beste and her associates wrote. “Health care systems will need to accommodate rising numbers of patients with cirrhosis and HCC.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Health Administration funded the study. The investigators declared no competing interests.

Cirrhosis nearly doubled among Veterans Affairs patients between 2001 and 2013, while cirrhosis-related mortality rose by about 50% and deaths from hepatocellular carcinoma almost tripled, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

Hepatitis C virus infection was “the overwhelming driver of these trends, with smaller contributions from alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other liver diseases,” said Dr. Lauren Beste of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates. Based on their data, the prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States will peak in 2021, they said. “In contrast, the incidence of HCC continues to increase, confirming worrisome predictions of rapid growth put forward by work (Gastroenterology. 2010;138[2]:513-21) conducted” in the early 2000s.

New HCV infections have dropped sharply in the United States since about 1990, but cases of HCV-related cirrhosis and HCC continue to rise as chronically infected patients age and their liver disease progresses. Although the burden of cirrhosis and HCC due to HCV infection is expected to peak in about the year 2020, the population-level effects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis B virus infection remained unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they retrospectively studied underlying etiologies among a national cohort of almost 130,000 Veterans Affairs patients with cirrhosis and more than 21,000 patients with HCC between 2001 and 2013 (Gastroenterology 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056).

In 2013, the VA cared for more than 5.7 million patients, including about 1% with cirrhosis and 0.13% with HCC. Between 2001 and 2013, the prevalence of cirrhosis almost doubled, rising from 664 to 1,058 cases for every 100,000 patients. Deaths among cirrhotic patients also increased by about half, rising from 83 to 126 for every 100,000 patient-years. These liver-related deaths were mainly caused by HCC, whose incidence rose about 2.5 times from 17 to 45 per 100,000 patient-years, Dr. Beste and her associates reported.

Notably, deaths due to liver cancer rose threefold – from 13 to 37 per 100,000 patient-years between 2001 and 2013, “driven overwhelmingly by HCV with much smaller contributions from NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease,” said the researchers. By 2013, almost half of cirrhosis cases and related deaths occurred among HCV-infected patients, as did 67% of HCC cases and related deaths, they noted.

About 60% of patients with cirrhosis and HCV infection also had a longstanding history of alcohol use, the researchers noted. Addressing both factors, as well as diabetes, obesity, and other drivers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, could help ease the national burden of liver disease and liver-related mortality among U.S. veterans and other groups, they added. “The increasing burden of cirrhosis and HCC highlights the need for greater efforts to address their causes at a population level,” Dr. Beste and her associates wrote. “Health care systems will need to accommodate rising numbers of patients with cirrhosis and HCC.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Health Administration funded the study. The investigators declared no competing interests.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality rose substantially among Veterans Affairs patients over the past 12 years, mainly driven by HCV infection.

Major finding: The prevalence of cirrhosis nearly doubled between 2001 and 2013, while cirrhosis-related deaths rose by about 50% and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma almost tripled.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 129,998 Veterans Affairs patients with cirrhosis and 21,326 VA patients with HCC between 2001 and 2013.

Disclosures: The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Health Administration funded the study. The investigators declared no competing interests.

Narrow-band colonoscopy faster, as sensitive as white light in ulcerative colitis

Among patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), narrow-band imaging colonoscopy with targeted and segmental biopsy specimens was faster, needed fewer specimens, and was as sensitive for detecting intraepithelial neoplasias as white light colonoscopy with targeted and stepwise sampling, researchers reported.

“Our study shows the high yield of stepwise random biopsy specimens in long-standing colitis,” Dr. Ludger Leifeld of the department of internal medicine at Evangelisches Krankenhaus Kalk in Cologne, Germany, and his associates wrote in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The highest sensitivity should be reached by combining the white light and narrow-band imaging techniques by switching between the modes.”

Ulcerative colitis increases colorectal cancer risk, and detecting lesions early can be lifesaving. But the best technique for colonoscopy in UC remains controversial, the investigators noted. Therefore, they prospectively studied 159 adults with left-sided UC diagnosed at least 15 years earlier who were in clinical remission and had not undergone partial colectomy. Each patient underwent both narrow-band imaging and white light colonoscopy separated by 3 weeks to 3 months. In addition to targeted sampling, white-light colonoscopists took four predefined biopsy specimens every 10 cm, as well as two biopsy specimens in each of the five segments of the colon. Narrow-band imaging procedures only involved taking targeted and segmental biopsy specimens (Clin Gastro Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.172).

Overall, colonoscopy detected dysplastic lesions in more than 22% of patients, the researchers reported. The narrow-band method identified similar numbers of intraepithelial cancers as white light, but required an average of only 11.9 specimens per patient – less than one-third as many as white light (38.6; P less than .001), the investigators said. Furthermore, withdrawal times averaged only 13 minutes for narrow-band imaging, compared with 23 minutes for white light colonoscopy (P less than .001). The two techniques had similar miss rates, according to the researchers.

Notably, 37% of intraepithelial neoplasias that were detected by white light colonoscopy came from stepwise random biopsy specimens, said the investigators. “The idea to take random biopsy specimens is ignored by many endoscopists, which limits the sensitivity of those colonoscopies,” they emphasized. “The sensitivity of stepwise random biopsy specimens could be increased further by adding 10 more segmental random biopsy specimens, which uncovered an additional 13% of lesions,” they added. Fourteen of these 15 lesions were non–adenomalike, showing the importance of random biopsy specimens, especially for detecting nonadenoma lesions, they said.

“When the white light technique is used, stepwise biopsy specimens are indispensable,” the investigators concluded. For narrow-band imaging technology, “combining targeted biopsy specimens … with 10 segmental biopsy specimens is an equipotent alternative to targeted biopsy specimens using white light in addition to four biopsy specimens every 10 cm. However, [the narrow-band] approach significantly saves time and numbers of biopsy specimens, which should have positive effects on feasibility, costs, and endoscopist compliance.”

The study was funded by Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis Ulcerosa Vereinigung, the Working Group for Endoscopic Research of the DGVS, and the Kurscheid Foundation, and Olympus Medical. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Among patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), narrow-band imaging colonoscopy with targeted and segmental biopsy specimens was faster, needed fewer specimens, and was as sensitive for detecting intraepithelial neoplasias as white light colonoscopy with targeted and stepwise sampling, researchers reported.

“Our study shows the high yield of stepwise random biopsy specimens in long-standing colitis,” Dr. Ludger Leifeld of the department of internal medicine at Evangelisches Krankenhaus Kalk in Cologne, Germany, and his associates wrote in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The highest sensitivity should be reached by combining the white light and narrow-band imaging techniques by switching between the modes.”

Ulcerative colitis increases colorectal cancer risk, and detecting lesions early can be lifesaving. But the best technique for colonoscopy in UC remains controversial, the investigators noted. Therefore, they prospectively studied 159 adults with left-sided UC diagnosed at least 15 years earlier who were in clinical remission and had not undergone partial colectomy. Each patient underwent both narrow-band imaging and white light colonoscopy separated by 3 weeks to 3 months. In addition to targeted sampling, white-light colonoscopists took four predefined biopsy specimens every 10 cm, as well as two biopsy specimens in each of the five segments of the colon. Narrow-band imaging procedures only involved taking targeted and segmental biopsy specimens (Clin Gastro Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.172).

Overall, colonoscopy detected dysplastic lesions in more than 22% of patients, the researchers reported. The narrow-band method identified similar numbers of intraepithelial cancers as white light, but required an average of only 11.9 specimens per patient – less than one-third as many as white light (38.6; P less than .001), the investigators said. Furthermore, withdrawal times averaged only 13 minutes for narrow-band imaging, compared with 23 minutes for white light colonoscopy (P less than .001). The two techniques had similar miss rates, according to the researchers.

Notably, 37% of intraepithelial neoplasias that were detected by white light colonoscopy came from stepwise random biopsy specimens, said the investigators. “The idea to take random biopsy specimens is ignored by many endoscopists, which limits the sensitivity of those colonoscopies,” they emphasized. “The sensitivity of stepwise random biopsy specimens could be increased further by adding 10 more segmental random biopsy specimens, which uncovered an additional 13% of lesions,” they added. Fourteen of these 15 lesions were non–adenomalike, showing the importance of random biopsy specimens, especially for detecting nonadenoma lesions, they said.

“When the white light technique is used, stepwise biopsy specimens are indispensable,” the investigators concluded. For narrow-band imaging technology, “combining targeted biopsy specimens … with 10 segmental biopsy specimens is an equipotent alternative to targeted biopsy specimens using white light in addition to four biopsy specimens every 10 cm. However, [the narrow-band] approach significantly saves time and numbers of biopsy specimens, which should have positive effects on feasibility, costs, and endoscopist compliance.”

The study was funded by Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis Ulcerosa Vereinigung, the Working Group for Endoscopic Research of the DGVS, and the Kurscheid Foundation, and Olympus Medical. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Among patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), narrow-band imaging colonoscopy with targeted and segmental biopsy specimens was faster, needed fewer specimens, and was as sensitive for detecting intraepithelial neoplasias as white light colonoscopy with targeted and stepwise sampling, researchers reported.

“Our study shows the high yield of stepwise random biopsy specimens in long-standing colitis,” Dr. Ludger Leifeld of the department of internal medicine at Evangelisches Krankenhaus Kalk in Cologne, Germany, and his associates wrote in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The highest sensitivity should be reached by combining the white light and narrow-band imaging techniques by switching between the modes.”

Ulcerative colitis increases colorectal cancer risk, and detecting lesions early can be lifesaving. But the best technique for colonoscopy in UC remains controversial, the investigators noted. Therefore, they prospectively studied 159 adults with left-sided UC diagnosed at least 15 years earlier who were in clinical remission and had not undergone partial colectomy. Each patient underwent both narrow-band imaging and white light colonoscopy separated by 3 weeks to 3 months. In addition to targeted sampling, white-light colonoscopists took four predefined biopsy specimens every 10 cm, as well as two biopsy specimens in each of the five segments of the colon. Narrow-band imaging procedures only involved taking targeted and segmental biopsy specimens (Clin Gastro Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.172).

Overall, colonoscopy detected dysplastic lesions in more than 22% of patients, the researchers reported. The narrow-band method identified similar numbers of intraepithelial cancers as white light, but required an average of only 11.9 specimens per patient – less than one-third as many as white light (38.6; P less than .001), the investigators said. Furthermore, withdrawal times averaged only 13 minutes for narrow-band imaging, compared with 23 minutes for white light colonoscopy (P less than .001). The two techniques had similar miss rates, according to the researchers.

Notably, 37% of intraepithelial neoplasias that were detected by white light colonoscopy came from stepwise random biopsy specimens, said the investigators. “The idea to take random biopsy specimens is ignored by many endoscopists, which limits the sensitivity of those colonoscopies,” they emphasized. “The sensitivity of stepwise random biopsy specimens could be increased further by adding 10 more segmental random biopsy specimens, which uncovered an additional 13% of lesions,” they added. Fourteen of these 15 lesions were non–adenomalike, showing the importance of random biopsy specimens, especially for detecting nonadenoma lesions, they said.

“When the white light technique is used, stepwise biopsy specimens are indispensable,” the investigators concluded. For narrow-band imaging technology, “combining targeted biopsy specimens … with 10 segmental biopsy specimens is an equipotent alternative to targeted biopsy specimens using white light in addition to four biopsy specimens every 10 cm. However, [the narrow-band] approach significantly saves time and numbers of biopsy specimens, which should have positive effects on feasibility, costs, and endoscopist compliance.”

The study was funded by Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis Ulcerosa Vereinigung, the Working Group for Endoscopic Research of the DGVS, and the Kurscheid Foundation, and Olympus Medical. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The narrow-band method identified similar numbers of intraepithelial cancers in ulcerative colitis patients as white light, but required less than one-third as many samples as white light and was faster.

Major finding: In patients with ulcerative colitis, narrow-band imaging colonoscopy with targeted and segmental biopsy specimens was faster, needed fewer specimens, and was as sensitive for detecting intraepithelial neoplasias as white light colonoscopy with targeted and stepwise sampling.

Data source: Prospective multicenter study of 159 patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis Ulcerosa Vereinigung, the Working Group for Endoscopic Research of the DGVS, and the Kurscheid Foundation, and Olympus Medical. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Fukuoka, Sendai guidelines identified advanced pancreatic neoplasias

Both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines correctly identified all patients whose cystic pancreatic lesions were advanced neoplasias, but the “high-risk” criteria for both guidelines missed some high-grade dysplasias, researchers reported in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The updated Fukuoka guidelines are not superior to the Sendai guidelines in identifying neoplasias,” said Dr. Pavlos Kaimakliotis and his associates at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The single-center retrospective study showed that both guidelines can help triage patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms, but “have low specificity and positive predictive value, underscoring the pressing need to develop more accurate predictors of malignancy,” the researchers said. “On the basis of our data, we recommend that the Fukuoka guidelines be used only as a framework for the work-up of a patient with a suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm, and that management be adapted in the context of the individual patient.”

Developed in 2006, the Sendai consensus guidelines (Pancreatology 2006;6:17-32) reliably detected patients with malignant mucinous lesions of the pancreas, but poor specificity led to many needless resections, noted the investigators. The revised Fukuoka guidelines (Pancreatology 2012;12:183-97), improved specificity by classifying cysts measuring more than 3 cm as worrisome, rather than high risk. Notably, cyst size did not predict advanced neoplasia in the study, even though several consensus guidelines recommend resection when cysts exceed 3 cm, the investigators said. “Other studies have demonstrated similar results, with rates of advanced neoplasia of 25%-34% in cysts less than 3 cm in size,” they added (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.01).

The study included 194 patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasias assessed by cross-sectional imaging prior to surgical resection between 2000 and 2008. Surgical pathology revealed advanced neoplasias among 18.5% of patients. Overall median cyst size was 33 mm, said the investigators. All patients with invasive cancers met the high-risk criteria in both guidelines, but three patients in the Sendai low-risk group and two patients in the Fukuoka low-risk group had high-grade dysplasias, they said. The Sendai consensus guidelines identified patients with advanced neoplasia with about 92% sensitivity, 21% specificity, 21% positive predictive value, and 92% negative predictive value, while the Fukuoka had about 55% sensitivity, 73% specificity, 32% positive predictive value, and 88% negative predictive value. However, the guidelines did not statistically differ in their ability to predict neoplasia, the researchers said.

“In the course of reviewing our data, we have become increasingly conservative in the management of patients with pancreatic cysts,” the researchers commented. “This approach has been underscored by the low number of cases of advanced neoplasia, even among those who would be considered high risk on the basis of the updated guidelines, in surgically resected patients. With the elimination of cyst size as a high-risk predictor of malignancy for mucinous cysts, cognizance that smaller cysts can also harbor malignancy should come.”

The researchers reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

This study by Kaimakliotis et al. highlights the limitations in the current diagnostic and management algorithm for mucinous cystic lesion of the pancreas. Although both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines accurately detected patients with advanced neoplasia with a sensitivity higher than 90%, the specificity of both guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia did not exceed 22%. The updated Fukuoka guidelines were not superior to the Sendai guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia.

|

| Dr. Mohamed O. Othman |

The worrisome group in the Fukuoka guidelines was introduced to decrease the unnecessary resection of benign pancreatic cystic lesions and surveillance with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) imaging is recommended for this group. If a definite mural nodule, dilated pancreatic duct, or positive cytology is found on follow-up EUS, then the patient should be triaged for surgery. Lumping the low-risk lesions and the worrisome lesions of the Fukuoka guidelines into one group resulted in increasing the specificity of detecting advanced neoplasia to 73% at the expense of sensitivity, which dropped to 55.6%, which may result in missing many cases of advanced neoplasia.

Prospective evaluation of the performance of the updated Fukuoka guidelines with particular attention to the worrisome group is needed. Ultimately, molecular markers that can predict the risk of progression to malignancy will be validated and will most likely replace the current experts’ opinion and consensus guidelines.

Dr. Mohamed O. Othman is director of advanced endoscopy, assistant professor of medicine, gastroenterology section, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no relevant conflicts of interest.

This study by Kaimakliotis et al. highlights the limitations in the current diagnostic and management algorithm for mucinous cystic lesion of the pancreas. Although both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines accurately detected patients with advanced neoplasia with a sensitivity higher than 90%, the specificity of both guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia did not exceed 22%. The updated Fukuoka guidelines were not superior to the Sendai guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia.

|

| Dr. Mohamed O. Othman |

The worrisome group in the Fukuoka guidelines was introduced to decrease the unnecessary resection of benign pancreatic cystic lesions and surveillance with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) imaging is recommended for this group. If a definite mural nodule, dilated pancreatic duct, or positive cytology is found on follow-up EUS, then the patient should be triaged for surgery. Lumping the low-risk lesions and the worrisome lesions of the Fukuoka guidelines into one group resulted in increasing the specificity of detecting advanced neoplasia to 73% at the expense of sensitivity, which dropped to 55.6%, which may result in missing many cases of advanced neoplasia.

Prospective evaluation of the performance of the updated Fukuoka guidelines with particular attention to the worrisome group is needed. Ultimately, molecular markers that can predict the risk of progression to malignancy will be validated and will most likely replace the current experts’ opinion and consensus guidelines.

Dr. Mohamed O. Othman is director of advanced endoscopy, assistant professor of medicine, gastroenterology section, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no relevant conflicts of interest.

This study by Kaimakliotis et al. highlights the limitations in the current diagnostic and management algorithm for mucinous cystic lesion of the pancreas. Although both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines accurately detected patients with advanced neoplasia with a sensitivity higher than 90%, the specificity of both guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia did not exceed 22%. The updated Fukuoka guidelines were not superior to the Sendai guidelines in detecting advanced neoplasia.

|

| Dr. Mohamed O. Othman |

The worrisome group in the Fukuoka guidelines was introduced to decrease the unnecessary resection of benign pancreatic cystic lesions and surveillance with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) imaging is recommended for this group. If a definite mural nodule, dilated pancreatic duct, or positive cytology is found on follow-up EUS, then the patient should be triaged for surgery. Lumping the low-risk lesions and the worrisome lesions of the Fukuoka guidelines into one group resulted in increasing the specificity of detecting advanced neoplasia to 73% at the expense of sensitivity, which dropped to 55.6%, which may result in missing many cases of advanced neoplasia.

Prospective evaluation of the performance of the updated Fukuoka guidelines with particular attention to the worrisome group is needed. Ultimately, molecular markers that can predict the risk of progression to malignancy will be validated and will most likely replace the current experts’ opinion and consensus guidelines.

Dr. Mohamed O. Othman is director of advanced endoscopy, assistant professor of medicine, gastroenterology section, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines correctly identified all patients whose cystic pancreatic lesions were advanced neoplasias, but the “high-risk” criteria for both guidelines missed some high-grade dysplasias, researchers reported in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The updated Fukuoka guidelines are not superior to the Sendai guidelines in identifying neoplasias,” said Dr. Pavlos Kaimakliotis and his associates at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The single-center retrospective study showed that both guidelines can help triage patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms, but “have low specificity and positive predictive value, underscoring the pressing need to develop more accurate predictors of malignancy,” the researchers said. “On the basis of our data, we recommend that the Fukuoka guidelines be used only as a framework for the work-up of a patient with a suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm, and that management be adapted in the context of the individual patient.”

Developed in 2006, the Sendai consensus guidelines (Pancreatology 2006;6:17-32) reliably detected patients with malignant mucinous lesions of the pancreas, but poor specificity led to many needless resections, noted the investigators. The revised Fukuoka guidelines (Pancreatology 2012;12:183-97), improved specificity by classifying cysts measuring more than 3 cm as worrisome, rather than high risk. Notably, cyst size did not predict advanced neoplasia in the study, even though several consensus guidelines recommend resection when cysts exceed 3 cm, the investigators said. “Other studies have demonstrated similar results, with rates of advanced neoplasia of 25%-34% in cysts less than 3 cm in size,” they added (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.01).

The study included 194 patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasias assessed by cross-sectional imaging prior to surgical resection between 2000 and 2008. Surgical pathology revealed advanced neoplasias among 18.5% of patients. Overall median cyst size was 33 mm, said the investigators. All patients with invasive cancers met the high-risk criteria in both guidelines, but three patients in the Sendai low-risk group and two patients in the Fukuoka low-risk group had high-grade dysplasias, they said. The Sendai consensus guidelines identified patients with advanced neoplasia with about 92% sensitivity, 21% specificity, 21% positive predictive value, and 92% negative predictive value, while the Fukuoka had about 55% sensitivity, 73% specificity, 32% positive predictive value, and 88% negative predictive value. However, the guidelines did not statistically differ in their ability to predict neoplasia, the researchers said.

“In the course of reviewing our data, we have become increasingly conservative in the management of patients with pancreatic cysts,” the researchers commented. “This approach has been underscored by the low number of cases of advanced neoplasia, even among those who would be considered high risk on the basis of the updated guidelines, in surgically resected patients. With the elimination of cyst size as a high-risk predictor of malignancy for mucinous cysts, cognizance that smaller cysts can also harbor malignancy should come.”

The researchers reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

Both the Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines correctly identified all patients whose cystic pancreatic lesions were advanced neoplasias, but the “high-risk” criteria for both guidelines missed some high-grade dysplasias, researchers reported in the October issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The updated Fukuoka guidelines are not superior to the Sendai guidelines in identifying neoplasias,” said Dr. Pavlos Kaimakliotis and his associates at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The single-center retrospective study showed that both guidelines can help triage patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms, but “have low specificity and positive predictive value, underscoring the pressing need to develop more accurate predictors of malignancy,” the researchers said. “On the basis of our data, we recommend that the Fukuoka guidelines be used only as a framework for the work-up of a patient with a suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm, and that management be adapted in the context of the individual patient.”

Developed in 2006, the Sendai consensus guidelines (Pancreatology 2006;6:17-32) reliably detected patients with malignant mucinous lesions of the pancreas, but poor specificity led to many needless resections, noted the investigators. The revised Fukuoka guidelines (Pancreatology 2012;12:183-97), improved specificity by classifying cysts measuring more than 3 cm as worrisome, rather than high risk. Notably, cyst size did not predict advanced neoplasia in the study, even though several consensus guidelines recommend resection when cysts exceed 3 cm, the investigators said. “Other studies have demonstrated similar results, with rates of advanced neoplasia of 25%-34% in cysts less than 3 cm in size,” they added (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.01).

The study included 194 patients with suspected pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasias assessed by cross-sectional imaging prior to surgical resection between 2000 and 2008. Surgical pathology revealed advanced neoplasias among 18.5% of patients. Overall median cyst size was 33 mm, said the investigators. All patients with invasive cancers met the high-risk criteria in both guidelines, but three patients in the Sendai low-risk group and two patients in the Fukuoka low-risk group had high-grade dysplasias, they said. The Sendai consensus guidelines identified patients with advanced neoplasia with about 92% sensitivity, 21% specificity, 21% positive predictive value, and 92% negative predictive value, while the Fukuoka had about 55% sensitivity, 73% specificity, 32% positive predictive value, and 88% negative predictive value. However, the guidelines did not statistically differ in their ability to predict neoplasia, the researchers said.

“In the course of reviewing our data, we have become increasingly conservative in the management of patients with pancreatic cysts,” the researchers commented. “This approach has been underscored by the low number of cases of advanced neoplasia, even among those who would be considered high risk on the basis of the updated guidelines, in surgically resected patients. With the elimination of cyst size as a high-risk predictor of malignancy for mucinous cysts, cognizance that smaller cysts can also harbor malignancy should come.”

The researchers reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The Sendai and Fukuoka guidelines were equivalent when detecting advanced neoplasias among patients with pancreatic cystic lesions.

Major finding: All patients found to have invasive cancers met the high-risk criteria for both guidelines. Both guidelines missed some high-grade dysplasias.

Data source: Retrospective study of 194 patients with cystic lesions of the pancreas.

Disclosures: The researchers reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

High death rates for IBD patients who underwent emergency resections

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were about five to eight times more likely to die after emergency intestinal resection as opposed to elective surgery, a large meta-analysis found.

Overall mortality rates after emergency intestinal resection were 5.3% for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 3.6% for patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), said Dr. Sunny Singh and his associates at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. In contrast, only 0.6%-0.7% of patients died after elective resection, the researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology (2015 Jun 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.001).

Source: American Gastroenterological AssociationClinicians should optimize medical management to avoid emergency resection, seek ways to reduce associated mortality, and use the data when counseling patients and weighing medical and surgical management options, they added.

Intestinal resection is less common among patients with IBD than in decades past, but almost half of CD patients undergo the surgery within 10 years of diagnosis, as do 16% of UC patients, according to another meta-analysis (Gastroenterology 2013;145:996-1006). Past studies have reported divergent rates of death after these surgeries, the researchers noted. To better understand mortality rates and relevant risk factors, they reviewed 18 original research articles and three abstracts published between 1990 and 2015, all of which were indexed in Medline, EMBASE, or PubMed. The studies included 67,057 UC patients and 75,971 CD patients from 15 countries.

Rates of mortality after elective resection were significantly lower than after emergency resection, whether patients had CD (elective, 0.6%; 95% confidence interval, 0.2%-1.7%; emergency, 3.6%; 1.8%-6.9%) or UC (elective, 0.7%; 0.6%-0.9%; emergency, 5.3%; 3.8%-7.3%), the researchers found. Death rates did not significantly differ based on disease type. Postoperative mortality dropped significantly after the 1990s among CD patients only, perhaps because emergency surgery has become less common in Calgary since 1997, the researchers said. However, they were unable to compare changes in death rates over time by surgery type, they said.

Several factors could explain the high fatality rates after emergency intestinal resection, the researchers said. Patients tended to have worse disease activity and higher rates of intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal abscess, toxic megacolon, preoperative clostridial diarrhea, venous thromboembolism, malnourishment, or prolonged treatment with intravenous corticosteroids, they said. General surgeons are more likely to perform emergency resections than elective cases, which are typically handled by more experienced colorectal surgeons, they added. Emergency resections also are less likely to be performed laparoscopically than are elective resections, they noted. “The low risk of death associated with elective intestinal resections for CD and UC could be used as a quality assurance benchmark to compare outcomes between hospitals and surgeons,” they added.

The research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Alberta-Innovates Health-Solutions, the Alberta IBD Consortium. Dr. Singh reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author Dr. Gilaad Kaplan and four coauthors disclosed speaker, advisory board, and funding relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were about five to eight times more likely to die after emergency intestinal resection as opposed to elective surgery, a large meta-analysis found.

Overall mortality rates after emergency intestinal resection were 5.3% for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 3.6% for patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), said Dr. Sunny Singh and his associates at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. In contrast, only 0.6%-0.7% of patients died after elective resection, the researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology (2015 Jun 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.001).

Source: American Gastroenterological AssociationClinicians should optimize medical management to avoid emergency resection, seek ways to reduce associated mortality, and use the data when counseling patients and weighing medical and surgical management options, they added.

Intestinal resection is less common among patients with IBD than in decades past, but almost half of CD patients undergo the surgery within 10 years of diagnosis, as do 16% of UC patients, according to another meta-analysis (Gastroenterology 2013;145:996-1006). Past studies have reported divergent rates of death after these surgeries, the researchers noted. To better understand mortality rates and relevant risk factors, they reviewed 18 original research articles and three abstracts published between 1990 and 2015, all of which were indexed in Medline, EMBASE, or PubMed. The studies included 67,057 UC patients and 75,971 CD patients from 15 countries.

Rates of mortality after elective resection were significantly lower than after emergency resection, whether patients had CD (elective, 0.6%; 95% confidence interval, 0.2%-1.7%; emergency, 3.6%; 1.8%-6.9%) or UC (elective, 0.7%; 0.6%-0.9%; emergency, 5.3%; 3.8%-7.3%), the researchers found. Death rates did not significantly differ based on disease type. Postoperative mortality dropped significantly after the 1990s among CD patients only, perhaps because emergency surgery has become less common in Calgary since 1997, the researchers said. However, they were unable to compare changes in death rates over time by surgery type, they said.

Several factors could explain the high fatality rates after emergency intestinal resection, the researchers said. Patients tended to have worse disease activity and higher rates of intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal abscess, toxic megacolon, preoperative clostridial diarrhea, venous thromboembolism, malnourishment, or prolonged treatment with intravenous corticosteroids, they said. General surgeons are more likely to perform emergency resections than elective cases, which are typically handled by more experienced colorectal surgeons, they added. Emergency resections also are less likely to be performed laparoscopically than are elective resections, they noted. “The low risk of death associated with elective intestinal resections for CD and UC could be used as a quality assurance benchmark to compare outcomes between hospitals and surgeons,” they added.

The research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Alberta-Innovates Health-Solutions, the Alberta IBD Consortium. Dr. Singh reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author Dr. Gilaad Kaplan and four coauthors disclosed speaker, advisory board, and funding relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were about five to eight times more likely to die after emergency intestinal resection as opposed to elective surgery, a large meta-analysis found.

Overall mortality rates after emergency intestinal resection were 5.3% for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 3.6% for patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), said Dr. Sunny Singh and his associates at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. In contrast, only 0.6%-0.7% of patients died after elective resection, the researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology (2015 Jun 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.001).

Source: American Gastroenterological AssociationClinicians should optimize medical management to avoid emergency resection, seek ways to reduce associated mortality, and use the data when counseling patients and weighing medical and surgical management options, they added.

Intestinal resection is less common among patients with IBD than in decades past, but almost half of CD patients undergo the surgery within 10 years of diagnosis, as do 16% of UC patients, according to another meta-analysis (Gastroenterology 2013;145:996-1006). Past studies have reported divergent rates of death after these surgeries, the researchers noted. To better understand mortality rates and relevant risk factors, they reviewed 18 original research articles and three abstracts published between 1990 and 2015, all of which were indexed in Medline, EMBASE, or PubMed. The studies included 67,057 UC patients and 75,971 CD patients from 15 countries.

Rates of mortality after elective resection were significantly lower than after emergency resection, whether patients had CD (elective, 0.6%; 95% confidence interval, 0.2%-1.7%; emergency, 3.6%; 1.8%-6.9%) or UC (elective, 0.7%; 0.6%-0.9%; emergency, 5.3%; 3.8%-7.3%), the researchers found. Death rates did not significantly differ based on disease type. Postoperative mortality dropped significantly after the 1990s among CD patients only, perhaps because emergency surgery has become less common in Calgary since 1997, the researchers said. However, they were unable to compare changes in death rates over time by surgery type, they said.

Several factors could explain the high fatality rates after emergency intestinal resection, the researchers said. Patients tended to have worse disease activity and higher rates of intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal abscess, toxic megacolon, preoperative clostridial diarrhea, venous thromboembolism, malnourishment, or prolonged treatment with intravenous corticosteroids, they said. General surgeons are more likely to perform emergency resections than elective cases, which are typically handled by more experienced colorectal surgeons, they added. Emergency resections also are less likely to be performed laparoscopically than are elective resections, they noted. “The low risk of death associated with elective intestinal resections for CD and UC could be used as a quality assurance benchmark to compare outcomes between hospitals and surgeons,” they added.

The research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Alberta-Innovates Health-Solutions, the Alberta IBD Consortium. Dr. Singh reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author Dr. Gilaad Kaplan and four coauthors disclosed speaker, advisory board, and funding relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with IBD were about five to eight times more likely to die after emergency intestinal resection as opposed to elective surgery.

Major finding: Overall mortality rates after emergency intestinal resection were 5.3% for patients with ulcerative colitis and 3.6% for Crohn’s disease; mortality rates after elective surgery were 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively.

Data source: Meta-analysis of 18 original research studies and three abstracts published between 1990 and 2015.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Alberta-Innovates Health-Solutions, the Alberta IBD Consortium. Dr. Singh reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author Dr. Gilaad Kaplan and four coauthors disclosed speaker, advisory board, and funding relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

H. pylori resistance highlights need for guided therapy

Only half of Helicobacter pylori strains were pansusceptible, and almost one in three was resistant to at least one antibiotic, according to a single-center study of U.S. veterans published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The analysis is the first published report of H. pylori resistance in more than a decade, said Dr. Seiji Shiota at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his associates. “Clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin resistances were all high among untreated patients, suggesting that they all should be avoided as components of empiric triple therapy [consisting of a] proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, plus a third antibiotic,” said the researchers. “The four-drug concomitant therapy and bismuth quadruple therapy, or antibiotic susceptibility–guided therapy, are likely be the best strategies locally and are recommended for previously untreated patients with H. pylori infection.”

The study assessed 656 gastric biopsies randomly selected from a cohort of 1,559 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Houston VA Medical Center between 2009 and 2013. About 90% of patients were male, and patients ranged in age from 40 to 79 years old, with an average age of 60 years. The researchers cultured tissue samples and used the E test to assess minimum inhibitory concentrations for amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, levofloxacin, and tetracycline. (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Feb 11. pii: S1542-3565(15)00122-6).

A total of 135 (20.6%) of the biopsies cultured H. pylori, of which half (65 strains) were susceptible to all five antibiotics tested, 31% were resistant to levofloxacin (95% confidence interval, 23%-39%), 20% were resistant to metronidazole (95% CI, 13%-27%), 16% were resistant to clarithromycin (95% CI, 10%-23%), 0.8% were resistant to tetracycline (95% CI, 0%-2%), and none were resistant to amoxicillin, said the researchers. The extent of levofloxacin resistance was a “new and concerning finding” that was linked in the multivariable analysis with past fluoroquinolone treatment, reflecting the rising use of fluoroquinolones in community practice, they said. “Levofloxacin has been recommended as a rescue drug to eradicate H. pylori in patients who fail first-line therapy,” they added. “Locally, it would seem to be a poor choice on the basis of the high resistance rate (31.9%), which is higher than the 10% limit suggested as a cutoff for use of fluoroquinolone-containing triple therapy for H. pylori.”

Clarithromycin resistance also rose during the study period, probably because of the rising use of macrolides in respiratory and otorhinolaryngology, the investigators noted. Patients who had been treated before for helicobacteriosis were significantly more likely to have clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori infections even after accounting for demographic factors, smoking status, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and past use of macrolides and fluoroquinolones, they said. Based on that result, patients with a history of prior helicobacteriosis should not receive clarithromycin as part of triple therapy, they emphasized.

Resistance to metronidazole also remained high, but only 1.8% of isolates were resistant to both metronidazole and clarithromycin, making combination therapy with a proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin “an excellent choice as an empiric therapy,” added Dr. Shiota and his associates. Furthermore, the study might have overestimated the rate of metronidazole resistance because the E test yielded significantly higher minimum inhibitory concentration values than did agar dilution, they noted. The study cohort also was demographically dissimilar to that of the United States and might have reflected selection bias, because patients with a history of helicobacteriosis would be more likely to be referred for endoscopy, they said.

The National Institutes of Health and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety supported the study. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Antimicrobial-resistant strains of H. pylori are increasing in prevalence in the United States. In the study described here, only half of H. pylori strains were susceptible to commonly used antibiotics and approximately one in three were resistant to at least one antibiotic, according to a single-center study of U.S. veterans. The study assessed 656 gastric biopsies randomly selected from a cohort of 1,559 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Houston VA Medical Center between 2009 and 2013. Patients were mostly male and had an average age of 60 years. The researchers cultured tissue samples and used the E test to assess minimum inhibitory concentrations for amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, levofloxacin, and tetracycline.

|

Dr. Nimish Vakil |

A total of 135 (20.6%) of the biopsies cultured H. pylori, of which half (65 strains) were susceptible to all five antibiotics tested, 31% were resistant to levofloxacin (95% confidence interval, 23%-39%), 20% were resistant to metronidazole (95% CI, 13%-27%), 16% were resistant to clarithromycin (95% CI, 10%-23%), 0.8% were resistant to tetracycline (95% CI, 0%-2%), and none were resistant to amoxicillin, said the researchers.

The study mirrors findings in Europe where similar rates of resistance have been reported. European studies have also shown that levofloxacin resistance rises rapidly when it becomes widely used in the community, The study described here is not population based and consists mostly of male subjects and therefore may not be generalizable to the rest to the rest of the United States. As culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing is not available to most gastroenterologists, the initial treatment chosen should reflect resistance data in the community. Given the rising rates of resistance, it is important that eradication be confirmed 4 weeks or more after eradication therapy ends using a stool antigen test or a breath test. Clinicians should be prepared to re-treat patients if necessary.

Dr. Nimish Vakil, AGAF, is clinical professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison. He has no conflicts of interest.

Antimicrobial-resistant strains of H. pylori are increasing in prevalence in the United States. In the study described here, only half of H. pylori strains were susceptible to commonly used antibiotics and approximately one in three were resistant to at least one antibiotic, according to a single-center study of U.S. veterans. The study assessed 656 gastric biopsies randomly selected from a cohort of 1,559 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Houston VA Medical Center between 2009 and 2013. Patients were mostly male and had an average age of 60 years. The researchers cultured tissue samples and used the E test to assess minimum inhibitory concentrations for amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, levofloxacin, and tetracycline.

|

Dr. Nimish Vakil |

A total of 135 (20.6%) of the biopsies cultured H. pylori, of which half (65 strains) were susceptible to all five antibiotics tested, 31% were resistant to levofloxacin (95% confidence interval, 23%-39%), 20% were resistant to metronidazole (95% CI, 13%-27%), 16% were resistant to clarithromycin (95% CI, 10%-23%), 0.8% were resistant to tetracycline (95% CI, 0%-2%), and none were resistant to amoxicillin, said the researchers.

The study mirrors findings in Europe where similar rates of resistance have been reported. European studies have also shown that levofloxacin resistance rises rapidly when it becomes widely used in the community, The study described here is not population based and consists mostly of male subjects and therefore may not be generalizable to the rest to the rest of the United States. As culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing is not available to most gastroenterologists, the initial treatment chosen should reflect resistance data in the community. Given the rising rates of resistance, it is important that eradication be confirmed 4 weeks or more after eradication therapy ends using a stool antigen test or a breath test. Clinicians should be prepared to re-treat patients if necessary.

Dr. Nimish Vakil, AGAF, is clinical professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison. He has no conflicts of interest.