User login

Children and COVID: Vaccinations lower than ever as cases continue to drop

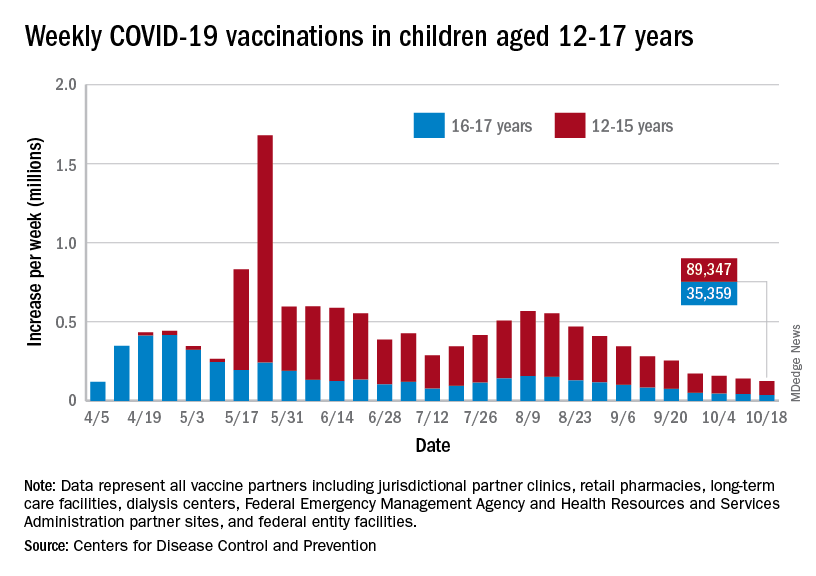

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

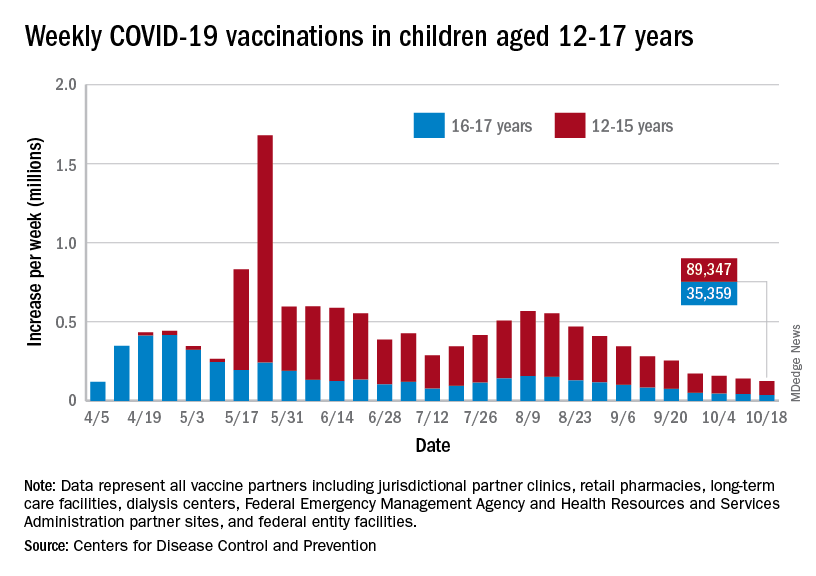

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

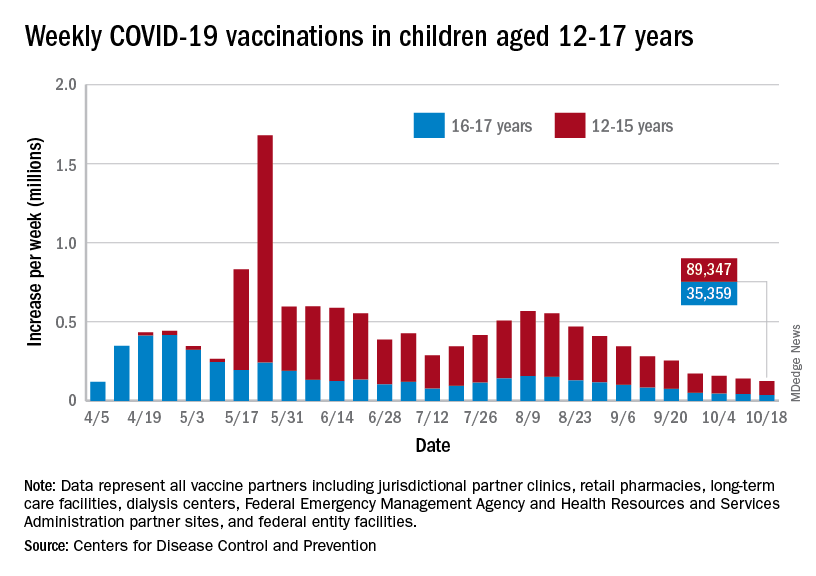

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

Open ICUs giveth and taketh away

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Mortality in 2nd wave higher with ECMO for COVID-ARDS

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Universal masking of health care workers decreases SARS-CoV-2 positivity

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Biomarkers may indicate severity of COVID in children

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA panel backs second dose for Johnson & Johnson vaccine recipients

It was the second vote in as many days to back a change to a COVID vaccine timeline.

In its vote, the committee said that boosters could be offered to people as young as age 18. However, it is not clear that everyone who got a Johnson & Johnson vaccine needs to get a second dose. The same panel voted Oct. 14 to recommend booster shots for the Moderna vaccine, but for a narrower group of people.

It will be up to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel to make more specific recommendations for who might need another shot. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is scheduled to meet next Oct. 21 to discuss issues related to COVID-19 vaccines.

Studies of the effectiveness of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the real world show that its protection — while good — has not been as strong as that of the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, which are given as part of a two-dose series.

In the end, the members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee said they felt that the company hadn’t made a case for calling their second shot a booster, but had shown enough data to suggest that everyone over the age of 18 should consider getting two shots of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine as a matter of course.

This is an especially important issue for adults over the age of 50. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that older adults who got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine were less protected against infection and hospitalization than those who got mRNA vaccines.

Limited data

The company presented data from six studies to the FDA panel in support of a second dose that were limited. The only study looking at second doses after 6 months included just 17 people.

These studies did show that a second dose substantially increased levels of neutralizing antibodies, which are the body’s first line of protection against COVID-19 infection.

But the company turned this data over to the FDA so recently that agency scientists repeatedly stressed during the meeting that they did not have ample time to follow their normal process of independently verifying the data and following up with their own analysis of the study results.

Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said it would have taken months to complete that rigorous level of review.

Instead, in the interest of urgency, the FDA said it had tried to bring some clarity to the tangle of study results presented that included three dosing schedules and different measures of effectiveness.

“Here’s how this strikes me,” said committee member Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “I think this vaccine was always a two-dose vaccine. I think it’s better as a two-dose vaccine. I think it would be hard to recommend this as a single-dose vaccine at this point.”

“As far as I’m concerned, it was always going to be necessary for J&J recipients to get a second shot,” said James Hildreth, MD, PhD, president and CEO of Meharry Medical College in Nashville.

Archana Chatterjee, MD, PhD, dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, said she had changed her vote during the course of the meeting.

She said that, based on the very limited safety and effectiveness data presented to the committee, she was prepared to vote against the idea of offering second doses of Johnson & Johnson shots.

But after considering the 15 million people who have been vaccinated with a single dose and studies that have suggested that close to 5 million older adults may still be at risk for hospitalization because they’ve just had one shot, “This is still a public health imperative,” she said.

“I’m in agreement with most of my colleagues that this second dose, booster, whatever you want to call it, is necessary in these individuals to boost up their immunity back into the 90-plus percentile range,” Dr. Chatterjee said.

Who needs a second dose?

On Oct. 14, the committee heard an update on data from Israel, which saw a wave of severe breakthrough infections during the Delta wave.

COVID-19 cases are falling rapidly there after the country widely deployed booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The FDA’s Dr. Marks said Oct. 15 that the agency was leaning toward creating greater flexibility in the emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines so that boosters could be more widely deployed in the United States too.

The FDA panel on Oct. 14 voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose of Moderna’s vaccine — half the dose used in the primary series of shots — to boost immunity at least 6 months after the second dose.

Those who might need a Moderna booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses, including people over 65, adults at higher risk for severe COVID-19, and those who are at higher risk because of where they live or work.

The FDA asked the committee on Oct. 15 to discuss whether boosters should be offered to younger adults, even those without underlying health conditions.

“We’re concerned that what was seen in Israel could be seen here,” Dr. Marks said. “We don’t want to have a wave of severe COVID-19 before we deploy boosters.”

Trying to avoid confusion

Some members of the committee cautioned Dr. Marks to be careful when expanding the EUAs, because it could confuse people.

“When we say immunity is waning, what are the implications of that?” said Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health.

Overall, data show that all the vaccines currently being used in the United States — including Johnson & Johnson — remain highly effective for preventing severe outcomes from COVID-19, like hospitalization and death.

Booster doses could prevent more people from even getting mild or moderate symptoms from “breakthrough” COVID-19 cases, which began to rise during the recent Delta surge. The additional doses are also expected to prevent severe outcomes like hospitalization in older adults and those with underlying health conditions.

“I think we need to be clear when we say waning immunity and we need to do something about that, I think we need to be clear what we’re really targeting [with boosters] in terms of clinical impact we expect to have,” Dr. Kurilla said.

Others pointed out that preventing even mild-to-moderate infections was a worthy goal, especially considering the implications of long-haul COVID-19.

“COVID does have tremendous downstream effects, even in those who are not hospitalized. Whenever we can prevent significant morbidity in a population, there are advantages to that,” said Steven Pergam, MD, MPH, medical director of infection prevention at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“I’d really be in the camp that would be moving towards a younger age range for allowing boosters,” he said.

This article was updated on 10/18/21. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was the second vote in as many days to back a change to a COVID vaccine timeline.

In its vote, the committee said that boosters could be offered to people as young as age 18. However, it is not clear that everyone who got a Johnson & Johnson vaccine needs to get a second dose. The same panel voted Oct. 14 to recommend booster shots for the Moderna vaccine, but for a narrower group of people.

It will be up to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel to make more specific recommendations for who might need another shot. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is scheduled to meet next Oct. 21 to discuss issues related to COVID-19 vaccines.

Studies of the effectiveness of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the real world show that its protection — while good — has not been as strong as that of the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, which are given as part of a two-dose series.

In the end, the members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee said they felt that the company hadn’t made a case for calling their second shot a booster, but had shown enough data to suggest that everyone over the age of 18 should consider getting two shots of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine as a matter of course.

This is an especially important issue for adults over the age of 50. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that older adults who got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine were less protected against infection and hospitalization than those who got mRNA vaccines.

Limited data

The company presented data from six studies to the FDA panel in support of a second dose that were limited. The only study looking at second doses after 6 months included just 17 people.

These studies did show that a second dose substantially increased levels of neutralizing antibodies, which are the body’s first line of protection against COVID-19 infection.

But the company turned this data over to the FDA so recently that agency scientists repeatedly stressed during the meeting that they did not have ample time to follow their normal process of independently verifying the data and following up with their own analysis of the study results.

Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said it would have taken months to complete that rigorous level of review.

Instead, in the interest of urgency, the FDA said it had tried to bring some clarity to the tangle of study results presented that included three dosing schedules and different measures of effectiveness.

“Here’s how this strikes me,” said committee member Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “I think this vaccine was always a two-dose vaccine. I think it’s better as a two-dose vaccine. I think it would be hard to recommend this as a single-dose vaccine at this point.”

“As far as I’m concerned, it was always going to be necessary for J&J recipients to get a second shot,” said James Hildreth, MD, PhD, president and CEO of Meharry Medical College in Nashville.

Archana Chatterjee, MD, PhD, dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, said she had changed her vote during the course of the meeting.

She said that, based on the very limited safety and effectiveness data presented to the committee, she was prepared to vote against the idea of offering second doses of Johnson & Johnson shots.

But after considering the 15 million people who have been vaccinated with a single dose and studies that have suggested that close to 5 million older adults may still be at risk for hospitalization because they’ve just had one shot, “This is still a public health imperative,” she said.

“I’m in agreement with most of my colleagues that this second dose, booster, whatever you want to call it, is necessary in these individuals to boost up their immunity back into the 90-plus percentile range,” Dr. Chatterjee said.

Who needs a second dose?

On Oct. 14, the committee heard an update on data from Israel, which saw a wave of severe breakthrough infections during the Delta wave.

COVID-19 cases are falling rapidly there after the country widely deployed booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The FDA’s Dr. Marks said Oct. 15 that the agency was leaning toward creating greater flexibility in the emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines so that boosters could be more widely deployed in the United States too.

The FDA panel on Oct. 14 voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose of Moderna’s vaccine — half the dose used in the primary series of shots — to boost immunity at least 6 months after the second dose.

Those who might need a Moderna booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses, including people over 65, adults at higher risk for severe COVID-19, and those who are at higher risk because of where they live or work.

The FDA asked the committee on Oct. 15 to discuss whether boosters should be offered to younger adults, even those without underlying health conditions.

“We’re concerned that what was seen in Israel could be seen here,” Dr. Marks said. “We don’t want to have a wave of severe COVID-19 before we deploy boosters.”

Trying to avoid confusion

Some members of the committee cautioned Dr. Marks to be careful when expanding the EUAs, because it could confuse people.

“When we say immunity is waning, what are the implications of that?” said Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health.

Overall, data show that all the vaccines currently being used in the United States — including Johnson & Johnson — remain highly effective for preventing severe outcomes from COVID-19, like hospitalization and death.

Booster doses could prevent more people from even getting mild or moderate symptoms from “breakthrough” COVID-19 cases, which began to rise during the recent Delta surge. The additional doses are also expected to prevent severe outcomes like hospitalization in older adults and those with underlying health conditions.

“I think we need to be clear when we say waning immunity and we need to do something about that, I think we need to be clear what we’re really targeting [with boosters] in terms of clinical impact we expect to have,” Dr. Kurilla said.

Others pointed out that preventing even mild-to-moderate infections was a worthy goal, especially considering the implications of long-haul COVID-19.

“COVID does have tremendous downstream effects, even in those who are not hospitalized. Whenever we can prevent significant morbidity in a population, there are advantages to that,” said Steven Pergam, MD, MPH, medical director of infection prevention at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“I’d really be in the camp that would be moving towards a younger age range for allowing boosters,” he said.

This article was updated on 10/18/21. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was the second vote in as many days to back a change to a COVID vaccine timeline.

In its vote, the committee said that boosters could be offered to people as young as age 18. However, it is not clear that everyone who got a Johnson & Johnson vaccine needs to get a second dose. The same panel voted Oct. 14 to recommend booster shots for the Moderna vaccine, but for a narrower group of people.

It will be up to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel to make more specific recommendations for who might need another shot. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is scheduled to meet next Oct. 21 to discuss issues related to COVID-19 vaccines.

Studies of the effectiveness of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the real world show that its protection — while good — has not been as strong as that of the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, which are given as part of a two-dose series.

In the end, the members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee said they felt that the company hadn’t made a case for calling their second shot a booster, but had shown enough data to suggest that everyone over the age of 18 should consider getting two shots of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine as a matter of course.

This is an especially important issue for adults over the age of 50. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that older adults who got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine were less protected against infection and hospitalization than those who got mRNA vaccines.

Limited data

The company presented data from six studies to the FDA panel in support of a second dose that were limited. The only study looking at second doses after 6 months included just 17 people.

These studies did show that a second dose substantially increased levels of neutralizing antibodies, which are the body’s first line of protection against COVID-19 infection.

But the company turned this data over to the FDA so recently that agency scientists repeatedly stressed during the meeting that they did not have ample time to follow their normal process of independently verifying the data and following up with their own analysis of the study results.

Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said it would have taken months to complete that rigorous level of review.

Instead, in the interest of urgency, the FDA said it had tried to bring some clarity to the tangle of study results presented that included three dosing schedules and different measures of effectiveness.

“Here’s how this strikes me,” said committee member Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “I think this vaccine was always a two-dose vaccine. I think it’s better as a two-dose vaccine. I think it would be hard to recommend this as a single-dose vaccine at this point.”

“As far as I’m concerned, it was always going to be necessary for J&J recipients to get a second shot,” said James Hildreth, MD, PhD, president and CEO of Meharry Medical College in Nashville.

Archana Chatterjee, MD, PhD, dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, said she had changed her vote during the course of the meeting.

She said that, based on the very limited safety and effectiveness data presented to the committee, she was prepared to vote against the idea of offering second doses of Johnson & Johnson shots.

But after considering the 15 million people who have been vaccinated with a single dose and studies that have suggested that close to 5 million older adults may still be at risk for hospitalization because they’ve just had one shot, “This is still a public health imperative,” she said.

“I’m in agreement with most of my colleagues that this second dose, booster, whatever you want to call it, is necessary in these individuals to boost up their immunity back into the 90-plus percentile range,” Dr. Chatterjee said.

Who needs a second dose?

On Oct. 14, the committee heard an update on data from Israel, which saw a wave of severe breakthrough infections during the Delta wave.

COVID-19 cases are falling rapidly there after the country widely deployed booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The FDA’s Dr. Marks said Oct. 15 that the agency was leaning toward creating greater flexibility in the emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines so that boosters could be more widely deployed in the United States too.

The FDA panel on Oct. 14 voted to authorize a 50-milligram dose of Moderna’s vaccine — half the dose used in the primary series of shots — to boost immunity at least 6 months after the second dose.

Those who might need a Moderna booster are the same groups who’ve gotten a green light for third Pfizer doses, including people over 65, adults at higher risk for severe COVID-19, and those who are at higher risk because of where they live or work.

The FDA asked the committee on Oct. 15 to discuss whether boosters should be offered to younger adults, even those without underlying health conditions.

“We’re concerned that what was seen in Israel could be seen here,” Dr. Marks said. “We don’t want to have a wave of severe COVID-19 before we deploy boosters.”

Trying to avoid confusion

Some members of the committee cautioned Dr. Marks to be careful when expanding the EUAs, because it could confuse people.

“When we say immunity is waning, what are the implications of that?” said Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health.

Overall, data show that all the vaccines currently being used in the United States — including Johnson & Johnson — remain highly effective for preventing severe outcomes from COVID-19, like hospitalization and death.

Booster doses could prevent more people from even getting mild or moderate symptoms from “breakthrough” COVID-19 cases, which began to rise during the recent Delta surge. The additional doses are also expected to prevent severe outcomes like hospitalization in older adults and those with underlying health conditions.

“I think we need to be clear when we say waning immunity and we need to do something about that, I think we need to be clear what we’re really targeting [with boosters] in terms of clinical impact we expect to have,” Dr. Kurilla said.

Others pointed out that preventing even mild-to-moderate infections was a worthy goal, especially considering the implications of long-haul COVID-19.

“COVID does have tremendous downstream effects, even in those who are not hospitalized. Whenever we can prevent significant morbidity in a population, there are advantages to that,” said Steven Pergam, MD, MPH, medical director of infection prevention at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“I’d really be in the camp that would be moving towards a younger age range for allowing boosters,” he said.

This article was updated on 10/18/21. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

QI reduces daily labs and promotes sleep-friendly lab timing

Background: Daily labs are often unnecessary on clinically stable inpatients. Additionally, daily labs are frequently drawn very early in the morning, resulting in sleep disruptions. No prior studies have attempted an EHR-based intervention to simultaneously improve both frequency and timing of labs.

Study design: Quality improvement project.

Setting: Resident and hospitalist services at a single academic medical center.

Synopsis: After surveying providers about lab-ordering preferences, an EHR shortcut and visual reminder were built to facilitate labs being ordered every 48 hours at 6 a.m. (rather than daily at 4 a.m.). Results included 26.3% fewer routine lab draws per patient-day per week, and a significant increase in sleep-friendly lab order utilization per encounter per week on both resident services (intercept, 1.03; standard error, 0.29; P < .001) and hospitalist services (intercept, 1.17; SE, .50; P = .02).

Bottom line: An intervention consisting of physician education and an EHR tool reduced daily lab frequency and optimized morning lab timing to improve sleep.

Citation: Tapaskar N et al. Evaluation of the order SMARTT: An initiative to reduce phlebotomy and improve sleep-friendly labs on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:479-82.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Daily labs are often unnecessary on clinically stable inpatients. Additionally, daily labs are frequently drawn very early in the morning, resulting in sleep disruptions. No prior studies have attempted an EHR-based intervention to simultaneously improve both frequency and timing of labs.

Study design: Quality improvement project.

Setting: Resident and hospitalist services at a single academic medical center.

Synopsis: After surveying providers about lab-ordering preferences, an EHR shortcut and visual reminder were built to facilitate labs being ordered every 48 hours at 6 a.m. (rather than daily at 4 a.m.). Results included 26.3% fewer routine lab draws per patient-day per week, and a significant increase in sleep-friendly lab order utilization per encounter per week on both resident services (intercept, 1.03; standard error, 0.29; P < .001) and hospitalist services (intercept, 1.17; SE, .50; P = .02).

Bottom line: An intervention consisting of physician education and an EHR tool reduced daily lab frequency and optimized morning lab timing to improve sleep.

Citation: Tapaskar N et al. Evaluation of the order SMARTT: An initiative to reduce phlebotomy and improve sleep-friendly labs on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:479-82.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Daily labs are often unnecessary on clinically stable inpatients. Additionally, daily labs are frequently drawn very early in the morning, resulting in sleep disruptions. No prior studies have attempted an EHR-based intervention to simultaneously improve both frequency and timing of labs.

Study design: Quality improvement project.

Setting: Resident and hospitalist services at a single academic medical center.

Synopsis: After surveying providers about lab-ordering preferences, an EHR shortcut and visual reminder were built to facilitate labs being ordered every 48 hours at 6 a.m. (rather than daily at 4 a.m.). Results included 26.3% fewer routine lab draws per patient-day per week, and a significant increase in sleep-friendly lab order utilization per encounter per week on both resident services (intercept, 1.03; standard error, 0.29; P < .001) and hospitalist services (intercept, 1.17; SE, .50; P = .02).

Bottom line: An intervention consisting of physician education and an EHR tool reduced daily lab frequency and optimized morning lab timing to improve sleep.

Citation: Tapaskar N et al. Evaluation of the order SMARTT: An initiative to reduce phlebotomy and improve sleep-friendly labs on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:479-82.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

FDA advisors vote to recommend Moderna boosters