User login

NAM offers recommendations to fight clinician burnout

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

Climate change, health systems, and hospital medicine

Working toward carbon neutrality

I have always enjoyed talking with my patients from coastal Louisiana. They enjoy life, embrace their environment, and give me a perspective which is both similar and different than that of residents of New Orleans where I practice hospital medicine.

Their hospitalization is often a reflective moment in their lives. Lately I have been asking them about their advice to their children concerning the future of southern Louisiana in reference to sea rise, global warming, and increasing climatic events. More often than not, they have been telling their children it is time to move away.

These are a people who have strong devotion to family, but they are also practical. More than anything they would like their children to stay and preserve their heritage, but concern for their children’s future outweighs that. They have not come to this conclusion by scientific reports, but rather by what is happening before them. This group of people doesn’t alarm easily, but they see the unrelenting evidence of land loss and sea rise before them with little reason to believe it will change.

I am normally not one to speak out about climate change. Like most I have listened to the continuous alarms sounded by experts but have always assumed someone more qualified than myself should lead the efforts. But when I see the tangible effects of climate change both in my own life and the lives of my patients, I feel a sense of urgency.

12 years

Twelve years. That is the time we have to significantly reduce carbon emissions before catastrophic and potentially irreversible events will occur. This evidence is according to the authors of the landmark report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released in October 2018. The report states urgent and unprecedented changes are needed to limit temperature elevations of 1.5°C and 2°C, as compared with the preindustrial era. Exceeding a 2°C elevation will likely lead to global adverse events at an unprecedented level.1

The events forecast by the U.N. report are not abstract, particularly as they relate to public health. With high confidence, the report outlines with high specificity: increases in extreme heat, floods, crop failures, and a multitude of economic and social stressors which will affect the care of our most vulnerable patients.1

This statement by Dr. Dana Hanson, president of the World Medical Association, summarizes the effects of climate change on the delivery of health care: “Climate change represents an inevitable massive threat to global health that will likely eclipse the major pandemics as a leading cause of death in the 21st century.”

So, what does the health care system have to do with climate change and its primary driver, carbon emissions? More than I realized, as the U.S. health care industry produces 10% of the nation’s carbon emissions.2 If the U.S. health care system was a country it would be ranked seventh, ahead of the United Kingdom; 10% of all smog and 9% of all particulate-related respiratory disease can be attributed to the carbon emissions of the health care industry. This breaks down to possibly 20,000 premature deaths per year.2 Our current health care industry is a significant driver of environmentally related disease and will continue to be so, unless major change occurs.

Although much of it is behind the scenes, providing health care 24/7 is a highly energy-intensive and waste-producing endeavor. Many of the innovations to reduce carbon emissions that have been seen in other industries have lagged behind in health care, as we have focused on other issues.

But the health care system is transitioning. It strives to address the whole person, including where they live, work, and play. A key component of this will be addressing our impact on the environments we serve. How can we make that argument if we don’t first address our own impact on the climate?

Carbon-neutral health care

Health care is one of the few industries that has the economic clout, the scientific basis, the community engagement, and perhaps most importantly the motivations to “first, do no harm” that could lead a national (if not a global) transformation in environmental stewardship among all industries.

Many agree that action is needed, but is essential that we set specific meaningful goals that take into account the urgency of the situation. One possible solution is to encourage every health care system to begin the process of becoming carbon neutral. Simply defined, carbon neutrality is balancing the activities that result in carbon emissions with activities that reduce carbon emissions. Carbon neutrality has become the standard by which an industry’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions is measured. The measurement is standardized and achievable, and the basic concept is understood by most. It results not only in long-term benefits to climate change, but immediate improvement of air quality in the local community. In addition, achieving carbon neutrality serves as a catalyst of new desired industries, improves employee morale, and aids in recruitment.3

So, what would a carbon-neutral health care system look like? In short, sustainability should be considered in all of its actions. Risks and benefits would be contemplated, as we do with all treatments, except now environmental risks would be brought into the equation. This includes the obvious, such as purchasing and supporting the development of renewable energy, but also transportation of patients and employees, food supply chains, and even the use of virtual visits to reduce the environmental impact of patient transportation.

I am optimistic that carbon neutrality is achievable in the health care sector. It can drive economic development and engage the community in environmental stewardship efforts. But time is of the essence and leaders for these efforts are needed now. As hospitalists, we are on the front lines of the health care system. We see the direct impact of social, economic, and environmental issues on our patients. We have credibility with both our patients and hospital administration. Among all industries, there need to be champions of environmental sustainability efforts. Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to fill that role.

My concern is that 12 years is right around the corner. We are at an inflection point on our efforts to reduce carbon emissions and that is good, but time has become our enemy. The difference between terrible and unlivable will be our, and the world’s, response to reducing carbon emissions.

It is time for bold action from us, the health care community. It is our moment and our place to lead those efforts, so let’s take advantage of both this challenge and this opportunity. Consider leading those efforts in your health care system.

Dr. Conrad is medical director of community affairs and health policy at Ochsner Health Systems in New Orleans.

References

1. Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. Incheon [Republic of Korea]: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 7 Oct 2018.

2. Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS ONE. 11(6):e0157014.

3. McCunn LJ, Gifford R. Do green offices affect employee engagement and environmental attitudes? Archit Sci Rev. 55:2;128-34. doi: 10.1080/00038628.2012.667939.

Working toward carbon neutrality

Working toward carbon neutrality

I have always enjoyed talking with my patients from coastal Louisiana. They enjoy life, embrace their environment, and give me a perspective which is both similar and different than that of residents of New Orleans where I practice hospital medicine.

Their hospitalization is often a reflective moment in their lives. Lately I have been asking them about their advice to their children concerning the future of southern Louisiana in reference to sea rise, global warming, and increasing climatic events. More often than not, they have been telling their children it is time to move away.

These are a people who have strong devotion to family, but they are also practical. More than anything they would like their children to stay and preserve their heritage, but concern for their children’s future outweighs that. They have not come to this conclusion by scientific reports, but rather by what is happening before them. This group of people doesn’t alarm easily, but they see the unrelenting evidence of land loss and sea rise before them with little reason to believe it will change.

I am normally not one to speak out about climate change. Like most I have listened to the continuous alarms sounded by experts but have always assumed someone more qualified than myself should lead the efforts. But when I see the tangible effects of climate change both in my own life and the lives of my patients, I feel a sense of urgency.

12 years

Twelve years. That is the time we have to significantly reduce carbon emissions before catastrophic and potentially irreversible events will occur. This evidence is according to the authors of the landmark report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released in October 2018. The report states urgent and unprecedented changes are needed to limit temperature elevations of 1.5°C and 2°C, as compared with the preindustrial era. Exceeding a 2°C elevation will likely lead to global adverse events at an unprecedented level.1

The events forecast by the U.N. report are not abstract, particularly as they relate to public health. With high confidence, the report outlines with high specificity: increases in extreme heat, floods, crop failures, and a multitude of economic and social stressors which will affect the care of our most vulnerable patients.1

This statement by Dr. Dana Hanson, president of the World Medical Association, summarizes the effects of climate change on the delivery of health care: “Climate change represents an inevitable massive threat to global health that will likely eclipse the major pandemics as a leading cause of death in the 21st century.”

So, what does the health care system have to do with climate change and its primary driver, carbon emissions? More than I realized, as the U.S. health care industry produces 10% of the nation’s carbon emissions.2 If the U.S. health care system was a country it would be ranked seventh, ahead of the United Kingdom; 10% of all smog and 9% of all particulate-related respiratory disease can be attributed to the carbon emissions of the health care industry. This breaks down to possibly 20,000 premature deaths per year.2 Our current health care industry is a significant driver of environmentally related disease and will continue to be so, unless major change occurs.

Although much of it is behind the scenes, providing health care 24/7 is a highly energy-intensive and waste-producing endeavor. Many of the innovations to reduce carbon emissions that have been seen in other industries have lagged behind in health care, as we have focused on other issues.

But the health care system is transitioning. It strives to address the whole person, including where they live, work, and play. A key component of this will be addressing our impact on the environments we serve. How can we make that argument if we don’t first address our own impact on the climate?

Carbon-neutral health care

Health care is one of the few industries that has the economic clout, the scientific basis, the community engagement, and perhaps most importantly the motivations to “first, do no harm” that could lead a national (if not a global) transformation in environmental stewardship among all industries.

Many agree that action is needed, but is essential that we set specific meaningful goals that take into account the urgency of the situation. One possible solution is to encourage every health care system to begin the process of becoming carbon neutral. Simply defined, carbon neutrality is balancing the activities that result in carbon emissions with activities that reduce carbon emissions. Carbon neutrality has become the standard by which an industry’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions is measured. The measurement is standardized and achievable, and the basic concept is understood by most. It results not only in long-term benefits to climate change, but immediate improvement of air quality in the local community. In addition, achieving carbon neutrality serves as a catalyst of new desired industries, improves employee morale, and aids in recruitment.3

So, what would a carbon-neutral health care system look like? In short, sustainability should be considered in all of its actions. Risks and benefits would be contemplated, as we do with all treatments, except now environmental risks would be brought into the equation. This includes the obvious, such as purchasing and supporting the development of renewable energy, but also transportation of patients and employees, food supply chains, and even the use of virtual visits to reduce the environmental impact of patient transportation.

I am optimistic that carbon neutrality is achievable in the health care sector. It can drive economic development and engage the community in environmental stewardship efforts. But time is of the essence and leaders for these efforts are needed now. As hospitalists, we are on the front lines of the health care system. We see the direct impact of social, economic, and environmental issues on our patients. We have credibility with both our patients and hospital administration. Among all industries, there need to be champions of environmental sustainability efforts. Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to fill that role.

My concern is that 12 years is right around the corner. We are at an inflection point on our efforts to reduce carbon emissions and that is good, but time has become our enemy. The difference between terrible and unlivable will be our, and the world’s, response to reducing carbon emissions.

It is time for bold action from us, the health care community. It is our moment and our place to lead those efforts, so let’s take advantage of both this challenge and this opportunity. Consider leading those efforts in your health care system.

Dr. Conrad is medical director of community affairs and health policy at Ochsner Health Systems in New Orleans.

References

1. Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. Incheon [Republic of Korea]: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 7 Oct 2018.

2. Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS ONE. 11(6):e0157014.

3. McCunn LJ, Gifford R. Do green offices affect employee engagement and environmental attitudes? Archit Sci Rev. 55:2;128-34. doi: 10.1080/00038628.2012.667939.

I have always enjoyed talking with my patients from coastal Louisiana. They enjoy life, embrace their environment, and give me a perspective which is both similar and different than that of residents of New Orleans where I practice hospital medicine.

Their hospitalization is often a reflective moment in their lives. Lately I have been asking them about their advice to their children concerning the future of southern Louisiana in reference to sea rise, global warming, and increasing climatic events. More often than not, they have been telling their children it is time to move away.

These are a people who have strong devotion to family, but they are also practical. More than anything they would like their children to stay and preserve their heritage, but concern for their children’s future outweighs that. They have not come to this conclusion by scientific reports, but rather by what is happening before them. This group of people doesn’t alarm easily, but they see the unrelenting evidence of land loss and sea rise before them with little reason to believe it will change.

I am normally not one to speak out about climate change. Like most I have listened to the continuous alarms sounded by experts but have always assumed someone more qualified than myself should lead the efforts. But when I see the tangible effects of climate change both in my own life and the lives of my patients, I feel a sense of urgency.

12 years

Twelve years. That is the time we have to significantly reduce carbon emissions before catastrophic and potentially irreversible events will occur. This evidence is according to the authors of the landmark report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released in October 2018. The report states urgent and unprecedented changes are needed to limit temperature elevations of 1.5°C and 2°C, as compared with the preindustrial era. Exceeding a 2°C elevation will likely lead to global adverse events at an unprecedented level.1

The events forecast by the U.N. report are not abstract, particularly as they relate to public health. With high confidence, the report outlines with high specificity: increases in extreme heat, floods, crop failures, and a multitude of economic and social stressors which will affect the care of our most vulnerable patients.1

This statement by Dr. Dana Hanson, president of the World Medical Association, summarizes the effects of climate change on the delivery of health care: “Climate change represents an inevitable massive threat to global health that will likely eclipse the major pandemics as a leading cause of death in the 21st century.”

So, what does the health care system have to do with climate change and its primary driver, carbon emissions? More than I realized, as the U.S. health care industry produces 10% of the nation’s carbon emissions.2 If the U.S. health care system was a country it would be ranked seventh, ahead of the United Kingdom; 10% of all smog and 9% of all particulate-related respiratory disease can be attributed to the carbon emissions of the health care industry. This breaks down to possibly 20,000 premature deaths per year.2 Our current health care industry is a significant driver of environmentally related disease and will continue to be so, unless major change occurs.

Although much of it is behind the scenes, providing health care 24/7 is a highly energy-intensive and waste-producing endeavor. Many of the innovations to reduce carbon emissions that have been seen in other industries have lagged behind in health care, as we have focused on other issues.

But the health care system is transitioning. It strives to address the whole person, including where they live, work, and play. A key component of this will be addressing our impact on the environments we serve. How can we make that argument if we don’t first address our own impact on the climate?

Carbon-neutral health care

Health care is one of the few industries that has the economic clout, the scientific basis, the community engagement, and perhaps most importantly the motivations to “first, do no harm” that could lead a national (if not a global) transformation in environmental stewardship among all industries.

Many agree that action is needed, but is essential that we set specific meaningful goals that take into account the urgency of the situation. One possible solution is to encourage every health care system to begin the process of becoming carbon neutral. Simply defined, carbon neutrality is balancing the activities that result in carbon emissions with activities that reduce carbon emissions. Carbon neutrality has become the standard by which an industry’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions is measured. The measurement is standardized and achievable, and the basic concept is understood by most. It results not only in long-term benefits to climate change, but immediate improvement of air quality in the local community. In addition, achieving carbon neutrality serves as a catalyst of new desired industries, improves employee morale, and aids in recruitment.3

So, what would a carbon-neutral health care system look like? In short, sustainability should be considered in all of its actions. Risks and benefits would be contemplated, as we do with all treatments, except now environmental risks would be brought into the equation. This includes the obvious, such as purchasing and supporting the development of renewable energy, but also transportation of patients and employees, food supply chains, and even the use of virtual visits to reduce the environmental impact of patient transportation.

I am optimistic that carbon neutrality is achievable in the health care sector. It can drive economic development and engage the community in environmental stewardship efforts. But time is of the essence and leaders for these efforts are needed now. As hospitalists, we are on the front lines of the health care system. We see the direct impact of social, economic, and environmental issues on our patients. We have credibility with both our patients and hospital administration. Among all industries, there need to be champions of environmental sustainability efforts. Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to fill that role.

My concern is that 12 years is right around the corner. We are at an inflection point on our efforts to reduce carbon emissions and that is good, but time has become our enemy. The difference between terrible and unlivable will be our, and the world’s, response to reducing carbon emissions.

It is time for bold action from us, the health care community. It is our moment and our place to lead those efforts, so let’s take advantage of both this challenge and this opportunity. Consider leading those efforts in your health care system.

Dr. Conrad is medical director of community affairs and health policy at Ochsner Health Systems in New Orleans.

References

1. Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. Incheon [Republic of Korea]: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 7 Oct 2018.

2. Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS ONE. 11(6):e0157014.

3. McCunn LJ, Gifford R. Do green offices affect employee engagement and environmental attitudes? Archit Sci Rev. 55:2;128-34. doi: 10.1080/00038628.2012.667939.

New test edges closer to rapid, accurate ID of active TB

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection.

Major finding: The assay had a sensitivity of 86%.

Study details: A machine learning and validation study involving patients with chronic cough from multiple countries.

Disclosures: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

Source: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

The growing NP and PA workforce in hospital medicine

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

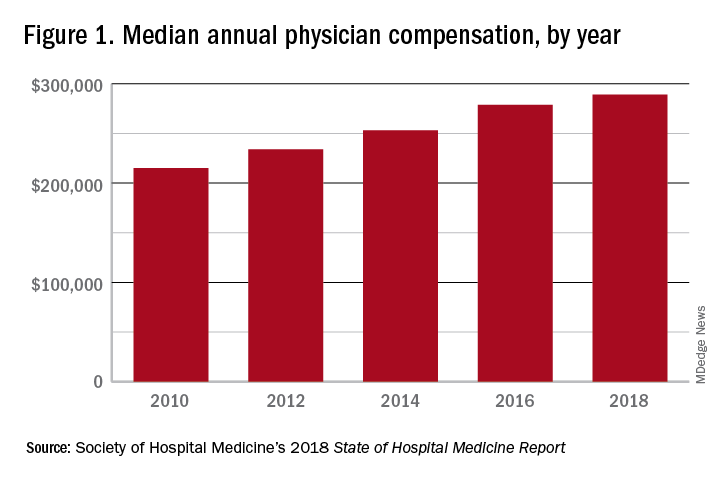

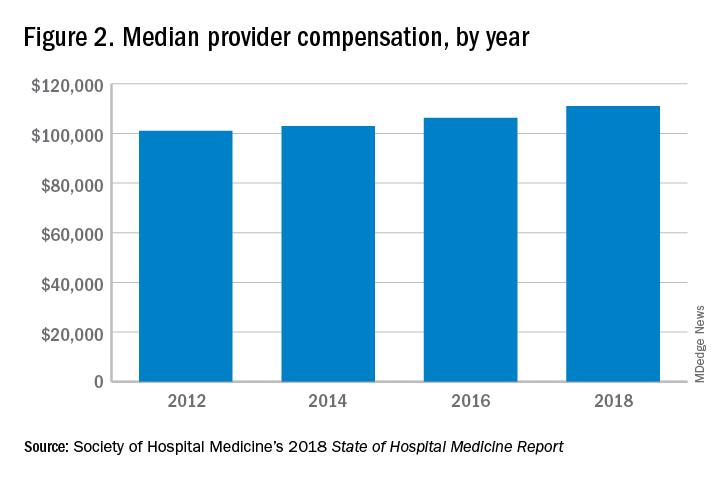

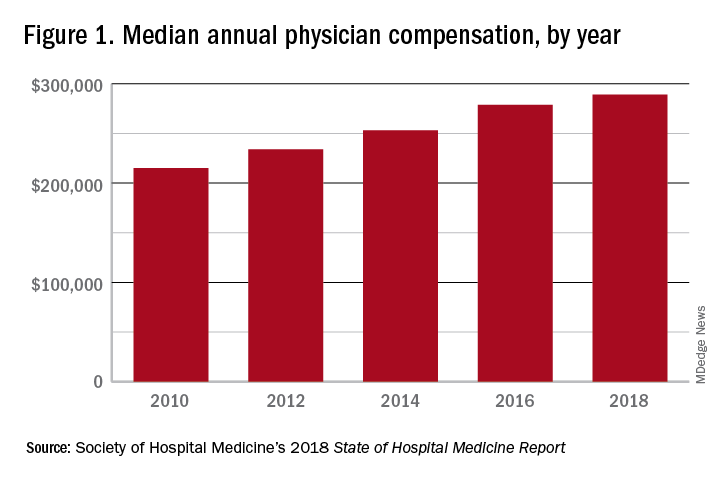

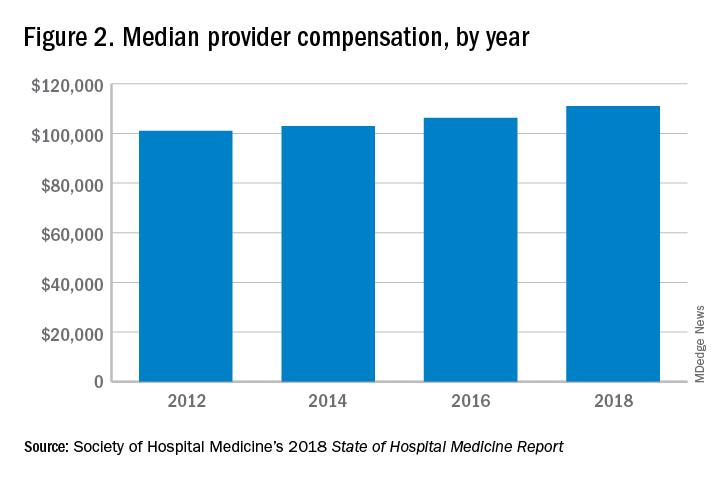

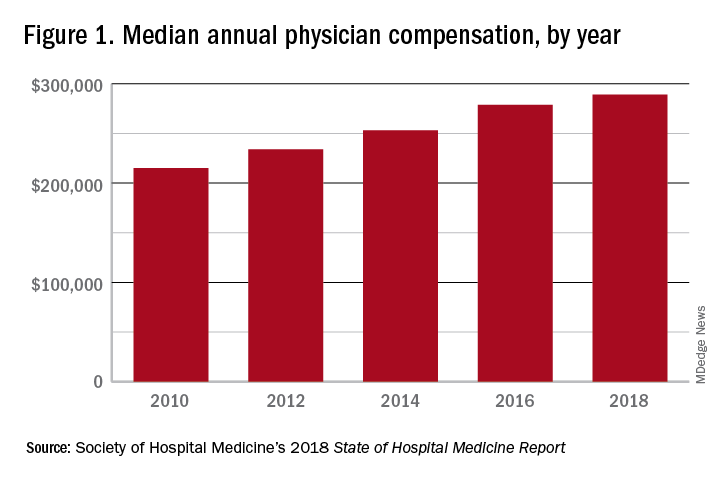

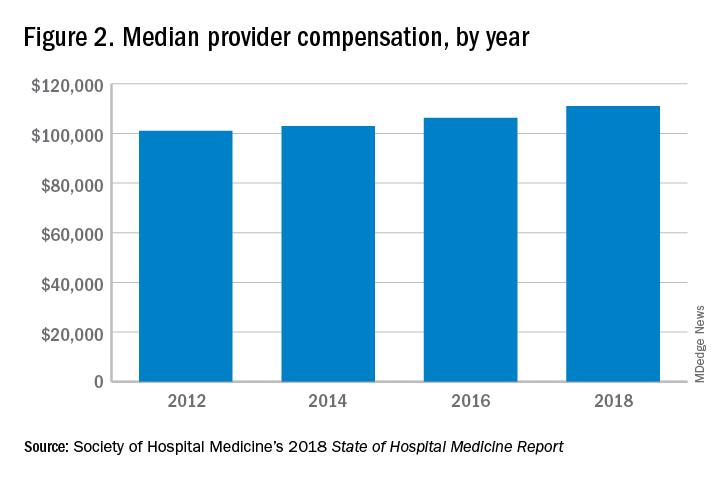

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

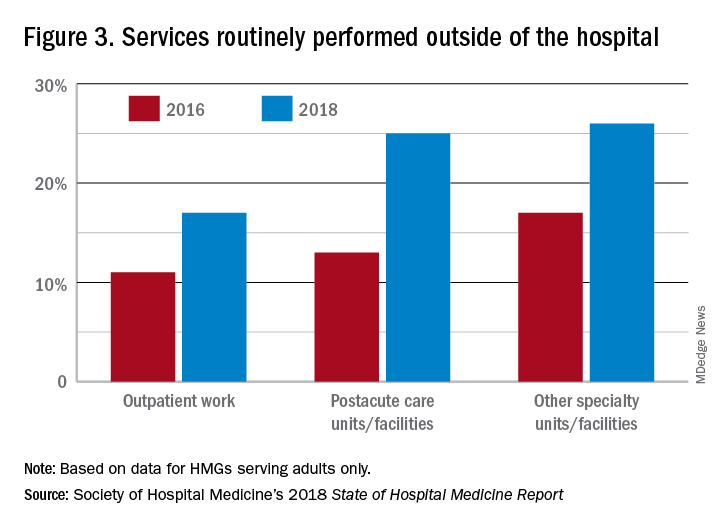

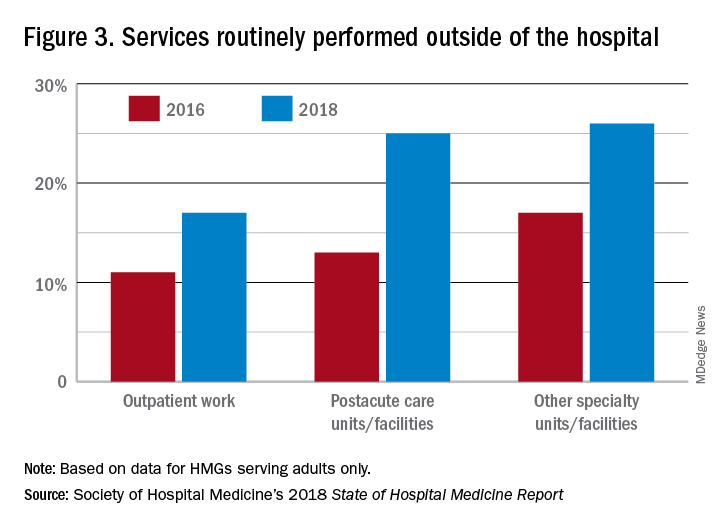

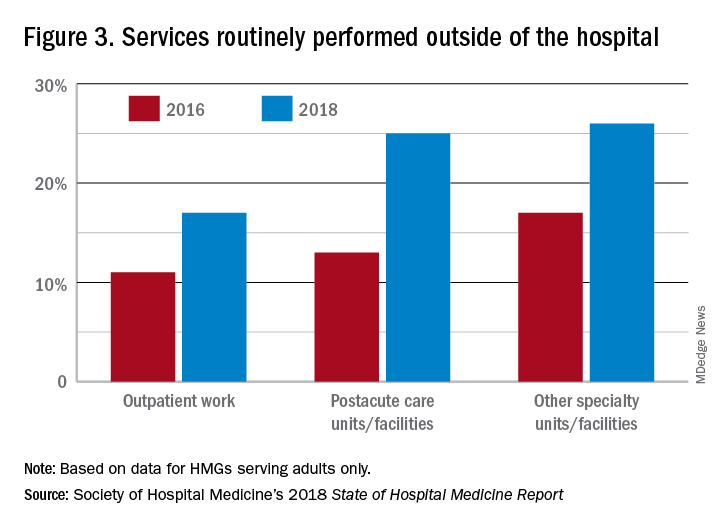

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

Vitamin C–based regimens in sepsis plausible, need more data, expert says

NEW ORLEANS – While further data are awaited on the role of vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids in sepsis, there is at least biologic plausibility for using the combination, and clinical equipoise that supports continued enrollment of patients in the ongoing randomized, controlled VICTAS trial, according to that study’s principal investigator.

“There is tremendous biologic plausibility for giving vitamin C in sepsis,” said Jon Sevransky, MD, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. But until more data are available on vitamin C–based regimens, those who choose to use vitamin C with thiamine and steroids in this setting need to ensure that glucose is being measured appropriately, he warned.

“If you decide that vitamin C is right for your patient, prior to having enough data – so if you’re doing a Hail Mary, or a ‘this patient is sick, and it’s probably not going to hurt them’ – please make sure that you measure your glucose with something that uses whole blood, which is either a blood gas or sending it down to the core lab, because otherwise, you might get an inaccurate result,” Dr. Sevransky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Steroids in Sepsis (VICTAS) trial may be available within the next few months, according to Dr. Sevransky, who noted that the trial was funded for 500 patients, which provides an 80% probability of showing an absolute risk reduction of 10% in mortality.

The primary endpoint of the phase 3 trial is vasopressor and ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomization, while 30-day mortality has been described as “the key secondary outcome” by Dr. Sevransky and colleagues in a recent report on the trial design.

Clinicians have been “captivated” by the potential benefit of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, as published in CHEST in June 2017, Dr. Sevransky said. In that study, reported by Paul E. Marik, MD, and colleagues, hospital mortality was 8.5% for the treatment group, versus 40.4% in the control group, a significant difference.

That retrospective, single-center study had a number of limitations, however, including its before-and-after design and the use of steroids in the comparator arm. In addition, little information was available on antibiotics or fluids given at the time of the intervention, according to Dr. Sevransky.

In results of the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial, just published in JAMA, intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C in patients with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) failed to significantly reduce organ failure scores or biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury.

In an exploratory analysis of CITRIS-ALI, mortality at day 28 was 29.8% for the treatment group and 46.3% for placebo, with a statistically significant difference between Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two arms, according to the investigators.

That exploratory result from CITRIS-ALI, however, is indicative of “something that needs further study,” Dr. Sevransky cautioned. “In summary, I hope I told you that biologic plausibility is present for vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids. I think that, and this is my own personal opinion, that evidence to date allows for randomization of patients, that there’s current equipoise.”

Dr. Sevransky disclosed current grant support from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Marcus Foundation, as well as a stipend from Critical Care Medicine related to work as an associate editor. He is also a medical advisor to Project Hope and ARDS Foundation and a member of the Surviving Sepsis guideline committees.

SOURCE: Sevransky J et al. Chest 2019.

NEW ORLEANS – While further data are awaited on the role of vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids in sepsis, there is at least biologic plausibility for using the combination, and clinical equipoise that supports continued enrollment of patients in the ongoing randomized, controlled VICTAS trial, according to that study’s principal investigator.

“There is tremendous biologic plausibility for giving vitamin C in sepsis,” said Jon Sevransky, MD, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. But until more data are available on vitamin C–based regimens, those who choose to use vitamin C with thiamine and steroids in this setting need to ensure that glucose is being measured appropriately, he warned.

“If you decide that vitamin C is right for your patient, prior to having enough data – so if you’re doing a Hail Mary, or a ‘this patient is sick, and it’s probably not going to hurt them’ – please make sure that you measure your glucose with something that uses whole blood, which is either a blood gas or sending it down to the core lab, because otherwise, you might get an inaccurate result,” Dr. Sevransky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Steroids in Sepsis (VICTAS) trial may be available within the next few months, according to Dr. Sevransky, who noted that the trial was funded for 500 patients, which provides an 80% probability of showing an absolute risk reduction of 10% in mortality.

The primary endpoint of the phase 3 trial is vasopressor and ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomization, while 30-day mortality has been described as “the key secondary outcome” by Dr. Sevransky and colleagues in a recent report on the trial design.

Clinicians have been “captivated” by the potential benefit of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, as published in CHEST in June 2017, Dr. Sevransky said. In that study, reported by Paul E. Marik, MD, and colleagues, hospital mortality was 8.5% for the treatment group, versus 40.4% in the control group, a significant difference.