User login

Mortality risk remains high for survivors of opioid overdose

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

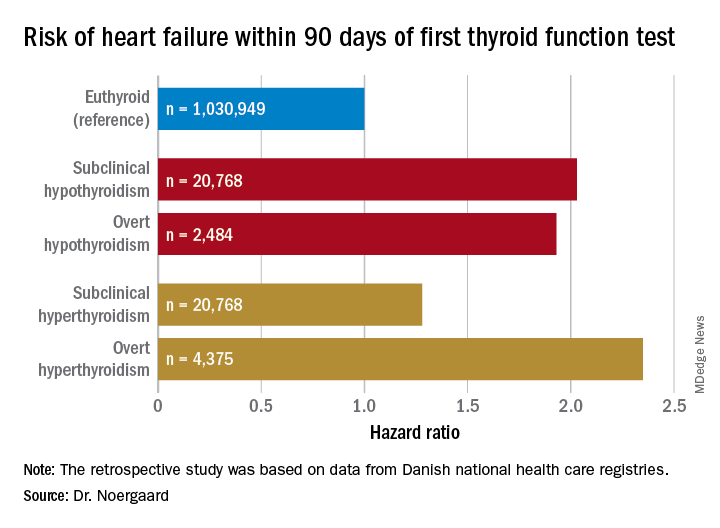

Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure

Dr. Noergaard presented a retrospective study of over 1 million Copenhagen-area adults (mean age, 50 years) with no history of heart failure, who had their first thyroid function test. She and her coinvestigators turned to comprehensive Danish national health care registries to determine how many of these individuals were diagnosed with new-onset heart failure within 90 days after their thyroid function test.

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined by a thyroid-stimulating hormone level greater than 5 mIU/L and a free T4 of 9-22 pmol/L. Overt hypothyroidism required a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L with a free T4 less than 9 pmol/L.

Free T4 predicts atrial fibrillation risk

Dr. Anderson presented a retrospective analysis of 174,914 adult patients in the Intermountain Healthcare EMR database, none of whom were on thyroid replacement at entry. The patients, who were a mean age of 64 years and 65% women, were followed for an average of 6.3 years. Of these, 88.4% had a free T4 within the normal reference range of 0.75-1.5 ng/dL, 7.4% had a value below the cutoff for normal, and 4.2% had a free T4 above the reference range.

Upon dividing the patients within the normal range into quartiles based upon their free T4 level, he and his coinvestigators found that the baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation was 8.7% in those in quartile 1, 9.3% in quartile 2, 10.5% in quartile 3, and 12.6% in quartile 4. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the risk of prevalent atrial fibrillation was increased by 11% for patients in quartile 2, compared with those in the first quartile, by 22% in quartile 3, and by 40% in quartile 4.

The incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during 3 years of follow-up was 4.1% in patients in normal-range quartile 1, 4.3% in quartile 2, 4.5% in quartile 3, and 5.2% in the top normal-range quartile. The odds of developing atrial fibrillation were increased by 8% and 16% in quartiles 3 and 4, compared with quartile 1.

Serum TSH and free T3 levels showed no consistent relationship with atrial fibrillation.

The Utah findings confirm in a large U.S. population the earlier report from the Rotterdam Study (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3718-24).

Dr. Noergaard and Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies, which were carried out free of commercial support.

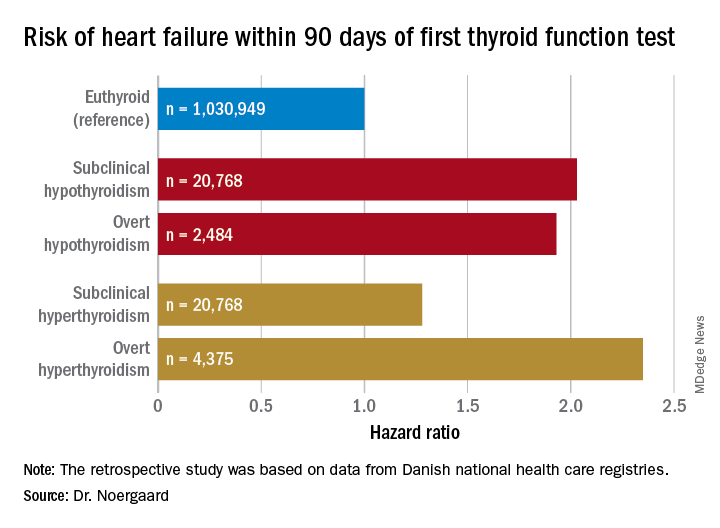

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure

Dr. Noergaard presented a retrospective study of over 1 million Copenhagen-area adults (mean age, 50 years) with no history of heart failure, who had their first thyroid function test. She and her coinvestigators turned to comprehensive Danish national health care registries to determine how many of these individuals were diagnosed with new-onset heart failure within 90 days after their thyroid function test.

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined by a thyroid-stimulating hormone level greater than 5 mIU/L and a free T4 of 9-22 pmol/L. Overt hypothyroidism required a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L with a free T4 less than 9 pmol/L.

Free T4 predicts atrial fibrillation risk

Dr. Anderson presented a retrospective analysis of 174,914 adult patients in the Intermountain Healthcare EMR database, none of whom were on thyroid replacement at entry. The patients, who were a mean age of 64 years and 65% women, were followed for an average of 6.3 years. Of these, 88.4% had a free T4 within the normal reference range of 0.75-1.5 ng/dL, 7.4% had a value below the cutoff for normal, and 4.2% had a free T4 above the reference range.

Upon dividing the patients within the normal range into quartiles based upon their free T4 level, he and his coinvestigators found that the baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation was 8.7% in those in quartile 1, 9.3% in quartile 2, 10.5% in quartile 3, and 12.6% in quartile 4. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the risk of prevalent atrial fibrillation was increased by 11% for patients in quartile 2, compared with those in the first quartile, by 22% in quartile 3, and by 40% in quartile 4.

The incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during 3 years of follow-up was 4.1% in patients in normal-range quartile 1, 4.3% in quartile 2, 4.5% in quartile 3, and 5.2% in the top normal-range quartile. The odds of developing atrial fibrillation were increased by 8% and 16% in quartiles 3 and 4, compared with quartile 1.

Serum TSH and free T3 levels showed no consistent relationship with atrial fibrillation.

The Utah findings confirm in a large U.S. population the earlier report from the Rotterdam Study (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3718-24).

Dr. Noergaard and Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies, which were carried out free of commercial support.

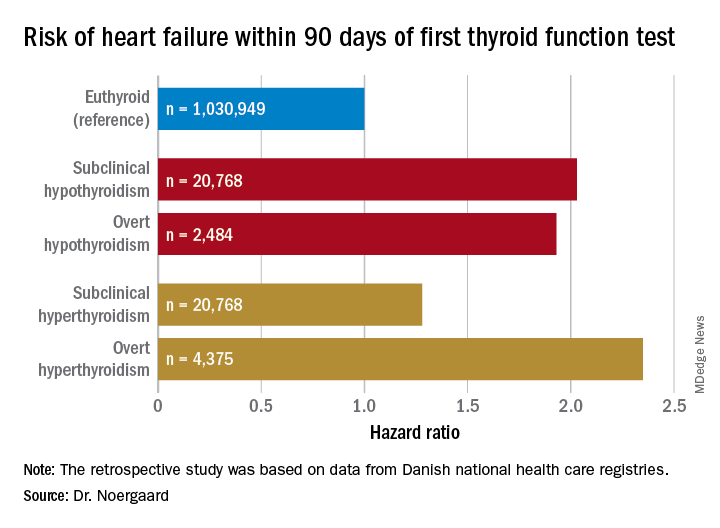

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure

Dr. Noergaard presented a retrospective study of over 1 million Copenhagen-area adults (mean age, 50 years) with no history of heart failure, who had their first thyroid function test. She and her coinvestigators turned to comprehensive Danish national health care registries to determine how many of these individuals were diagnosed with new-onset heart failure within 90 days after their thyroid function test.

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined by a thyroid-stimulating hormone level greater than 5 mIU/L and a free T4 of 9-22 pmol/L. Overt hypothyroidism required a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L with a free T4 less than 9 pmol/L.

Free T4 predicts atrial fibrillation risk

Dr. Anderson presented a retrospective analysis of 174,914 adult patients in the Intermountain Healthcare EMR database, none of whom were on thyroid replacement at entry. The patients, who were a mean age of 64 years and 65% women, were followed for an average of 6.3 years. Of these, 88.4% had a free T4 within the normal reference range of 0.75-1.5 ng/dL, 7.4% had a value below the cutoff for normal, and 4.2% had a free T4 above the reference range.

Upon dividing the patients within the normal range into quartiles based upon their free T4 level, he and his coinvestigators found that the baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation was 8.7% in those in quartile 1, 9.3% in quartile 2, 10.5% in quartile 3, and 12.6% in quartile 4. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the risk of prevalent atrial fibrillation was increased by 11% for patients in quartile 2, compared with those in the first quartile, by 22% in quartile 3, and by 40% in quartile 4.

The incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during 3 years of follow-up was 4.1% in patients in normal-range quartile 1, 4.3% in quartile 2, 4.5% in quartile 3, and 5.2% in the top normal-range quartile. The odds of developing atrial fibrillation were increased by 8% and 16% in quartiles 3 and 4, compared with quartile 1.

Serum TSH and free T3 levels showed no consistent relationship with atrial fibrillation.

The Utah findings confirm in a large U.S. population the earlier report from the Rotterdam Study (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3718-24).

Dr. Noergaard and Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies, which were carried out free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Both subclinical and overt hypothyroidism are associated with a 100% increased risk of being diagnosed with heart failure, compared with euthyroid individuals.

Study details: This was a retrospective study of the association between free thyroxine levels and short-term risk of developing heart failure in more than 1 million Copenhagen-area patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the Danish study, conducted free of commercial support.

New study determines factors that can send flu patients to the ICU

Numerous independent factors – including a history of obstructive/central sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS/CSAS) or myocardial infarction, along with a body mass index greater than 30 g/m2 – could be related to ICU admission and subsequent high mortality rates in influenza patients, according to an analysis of patients in the Netherlands who were treated during the influenza epidemic of 2015-2016.

Along with determining these factors, lead author M.C. Beumer, of Radboud University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and his coauthors found that “coinfections with bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens developed more often in patients who were admitted to the ICU.” The study was published in the Journal of Critical Care.

The coauthors reviewed 199 influenza patients who were admitted to two medical centers in the Netherlands during October 2015–April 2016. Of those patients, 45 (23%) were admitted to the ICU, primarily because of respiratory failure, and their mortality rate was 17/45 (38%) versus an overall mortality rate of 18/199 (9%).

Compared with patients in the normal ward, patients admitted to the ICU more frequently had a history of OSAS/CSAS (11% vs. 3%; P = .03) and MI (20% vs. 6%; P = .007), along with a BMI higher than 30 g/m2 (30% vs. 15%; P = .04) and dyspnea as a symptom (77% vs. 48%,; P = .001). In addition, more ICU-admitted patients had influenza A rather than influenza B, compared with those not admitted (87% vs. 66%; P = .009).

Pulmonary coinfections – including bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens – were also proportionally higher among the 45 ICU patients (56% vs. 20%; P less than .0001). The most common bacterial pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (11%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (7%) while Aspergillus fumigatus (18%) and Pneumocystis jirovecii (7%) topped the fungal pathogens.

Mr. Beumer and his colleagues noted potential limitations of their work, including the selection of patients from among the “most severely ill” contributing to an ICU admission rate that surpassed the 5%-10% described elsewhere. They also admitted that their study relied on a “relatively small sample size,” focusing on one seasonal influenza outbreak. However, “despite the limited validity,” they reiterated that “the identified factors may contribute to a complicated disease course and could represent a tool for early recognition of the influenza patients at risk for a complicated disease course.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Beumer MC et al. J Crit Care. 2019;50:59-65.

.

Numerous independent factors – including a history of obstructive/central sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS/CSAS) or myocardial infarction, along with a body mass index greater than 30 g/m2 – could be related to ICU admission and subsequent high mortality rates in influenza patients, according to an analysis of patients in the Netherlands who were treated during the influenza epidemic of 2015-2016.

Along with determining these factors, lead author M.C. Beumer, of Radboud University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and his coauthors found that “coinfections with bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens developed more often in patients who were admitted to the ICU.” The study was published in the Journal of Critical Care.

The coauthors reviewed 199 influenza patients who were admitted to two medical centers in the Netherlands during October 2015–April 2016. Of those patients, 45 (23%) were admitted to the ICU, primarily because of respiratory failure, and their mortality rate was 17/45 (38%) versus an overall mortality rate of 18/199 (9%).

Compared with patients in the normal ward, patients admitted to the ICU more frequently had a history of OSAS/CSAS (11% vs. 3%; P = .03) and MI (20% vs. 6%; P = .007), along with a BMI higher than 30 g/m2 (30% vs. 15%; P = .04) and dyspnea as a symptom (77% vs. 48%,; P = .001). In addition, more ICU-admitted patients had influenza A rather than influenza B, compared with those not admitted (87% vs. 66%; P = .009).

Pulmonary coinfections – including bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens – were also proportionally higher among the 45 ICU patients (56% vs. 20%; P less than .0001). The most common bacterial pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (11%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (7%) while Aspergillus fumigatus (18%) and Pneumocystis jirovecii (7%) topped the fungal pathogens.

Mr. Beumer and his colleagues noted potential limitations of their work, including the selection of patients from among the “most severely ill” contributing to an ICU admission rate that surpassed the 5%-10% described elsewhere. They also admitted that their study relied on a “relatively small sample size,” focusing on one seasonal influenza outbreak. However, “despite the limited validity,” they reiterated that “the identified factors may contribute to a complicated disease course and could represent a tool for early recognition of the influenza patients at risk for a complicated disease course.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Beumer MC et al. J Crit Care. 2019;50:59-65.

.

Numerous independent factors – including a history of obstructive/central sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS/CSAS) or myocardial infarction, along with a body mass index greater than 30 g/m2 – could be related to ICU admission and subsequent high mortality rates in influenza patients, according to an analysis of patients in the Netherlands who were treated during the influenza epidemic of 2015-2016.

Along with determining these factors, lead author M.C. Beumer, of Radboud University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and his coauthors found that “coinfections with bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens developed more often in patients who were admitted to the ICU.” The study was published in the Journal of Critical Care.

The coauthors reviewed 199 influenza patients who were admitted to two medical centers in the Netherlands during October 2015–April 2016. Of those patients, 45 (23%) were admitted to the ICU, primarily because of respiratory failure, and their mortality rate was 17/45 (38%) versus an overall mortality rate of 18/199 (9%).

Compared with patients in the normal ward, patients admitted to the ICU more frequently had a history of OSAS/CSAS (11% vs. 3%; P = .03) and MI (20% vs. 6%; P = .007), along with a BMI higher than 30 g/m2 (30% vs. 15%; P = .04) and dyspnea as a symptom (77% vs. 48%,; P = .001). In addition, more ICU-admitted patients had influenza A rather than influenza B, compared with those not admitted (87% vs. 66%; P = .009).

Pulmonary coinfections – including bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens – were also proportionally higher among the 45 ICU patients (56% vs. 20%; P less than .0001). The most common bacterial pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (11%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (7%) while Aspergillus fumigatus (18%) and Pneumocystis jirovecii (7%) topped the fungal pathogens.

Mr. Beumer and his colleagues noted potential limitations of their work, including the selection of patients from among the “most severely ill” contributing to an ICU admission rate that surpassed the 5%-10% described elsewhere. They also admitted that their study relied on a “relatively small sample size,” focusing on one seasonal influenza outbreak. However, “despite the limited validity,” they reiterated that “the identified factors may contribute to a complicated disease course and could represent a tool for early recognition of the influenza patients at risk for a complicated disease course.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Beumer MC et al. J Crit Care. 2019;50:59-65.

.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Flu patients in the ICU more frequently had a history of obstructive/central sleep apnea syndrome (11% vs. 3%; P = .03) and MI (20% vs. 6%; P = .007), compared with non-ICU flu patients.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 199 flu patients who were admitted to two academic hospitals in the Netherlands.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Beumer MC et al. J Crit Care. 2019; 50:59-65.

Increasing inpatient attending supervision does not decrease medical errors

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Prescribed opioids increase pneumonia risk in patients with, without HIV

Prescribed opioids were associated with an increase in community-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without HIV infection, according to results of a large database study.

People living with HIV (PLWH) appeared to have a greater community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) risk at lower opioid doses and particularly with immunosuppressive opioids compared with uninfected patients, although the difference was not significant, E. Jennifer Edelman, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers performed a nested case-control study comprising 25,392 participants (98.9% men; mean age, 55 years) in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2012.

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues compared the characteristics of 4,246 CAP cases with those of 21,146 uninfected controls in the sample. They also compared cases and controls by HIV status. They ran bivariate and multivariate analysis to estimate odds ratios for CAP risk associated with opioid exposure. In addition, the researchers ran models stratified by HIV status and formally checked for an interaction between prescribed opioid characteristics and HIV status.

In unadjusted logistic regression, prescribed opioids were associated with increased odds of CAP, with the greatest risk observed with currently prescribed opioids, compared with past prescribed opioids or no opioids.

Prescribed opioids remained associated with CAP in the adjusted models for past unknown or nonimmunosuppressive (adjusted OR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.40) and past immunosuppressive opioid use (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.67).

For currently prescribed opioids, nonimmunosuppressive or unknown, the aOR was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.03-1.48). For currently prescribed immunosuppressive opioids, the aOR was 3.18 (95% CI, 2.44-4.14).

The researchers also found evidence of a dose-response effect such that currently prescribed high-dose opioids were associated with the greatest CAP risk, followed by medium- and then by low-dose opioids, whether immunosuppressive or not.

With regard to the effect of HIV status in stratified, adjusted analyses, CAP risk tended to be greater among PLWH with current prescribed opioids, especially immunosuppressive opioids, compared with uninfected patients. However, the overall interaction term for opioid × HIV status was not significant (P = .36).

Although the researchers stated that a limitation of their study was an inability to prove causality or rule out respiratory depression (vs. immunosuppression) as the cause of the increased CAP risk, “the observed effects of opioid immunosuppressive properties and CAP risk lend support to our hypothesis that opioids have clinically relevant immunosuppressive properties.”

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, they were not able to determine whether patients took their prescribed medications appropriately and assess whether the patients took nonmedically prescribed opioids. Also, because men made up such a large portion of the study population, it is unclear whether the results are generalizable to women.

Nevertheless, the study “adds to growing evidence of potential medical harms associated with prescribed opioids,” they wrote.

“Health care professionals should be aware of this additional CAP risk when they prescribe opioids, and future studies should investigate the effects of opioids prescribed for longer durations and on other immune-related outcomes,” wrote Dr. Edelman and her colleagues. “Understanding whether mitigating the risk of prescribed opioids for CAP is possible by using a lower dose and nonimmunosuppressive opioids awaits further study.”

However, without such data, when prescribed opioids are warranted, physicians should attempt to modify other factors known to affect CAP risk, including smoking and lack of vaccination, Dr. Edelman and her colleagues concluded.

Several U.S. government agencies and Yale University provided funding for the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Edelman EJ et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6101.

Prescribed opioids were associated with an increase in community-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without HIV infection, according to results of a large database study.

People living with HIV (PLWH) appeared to have a greater community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) risk at lower opioid doses and particularly with immunosuppressive opioids compared with uninfected patients, although the difference was not significant, E. Jennifer Edelman, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers performed a nested case-control study comprising 25,392 participants (98.9% men; mean age, 55 years) in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2012.

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues compared the characteristics of 4,246 CAP cases with those of 21,146 uninfected controls in the sample. They also compared cases and controls by HIV status. They ran bivariate and multivariate analysis to estimate odds ratios for CAP risk associated with opioid exposure. In addition, the researchers ran models stratified by HIV status and formally checked for an interaction between prescribed opioid characteristics and HIV status.

In unadjusted logistic regression, prescribed opioids were associated with increased odds of CAP, with the greatest risk observed with currently prescribed opioids, compared with past prescribed opioids or no opioids.

Prescribed opioids remained associated with CAP in the adjusted models for past unknown or nonimmunosuppressive (adjusted OR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.40) and past immunosuppressive opioid use (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.67).

For currently prescribed opioids, nonimmunosuppressive or unknown, the aOR was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.03-1.48). For currently prescribed immunosuppressive opioids, the aOR was 3.18 (95% CI, 2.44-4.14).

The researchers also found evidence of a dose-response effect such that currently prescribed high-dose opioids were associated with the greatest CAP risk, followed by medium- and then by low-dose opioids, whether immunosuppressive or not.

With regard to the effect of HIV status in stratified, adjusted analyses, CAP risk tended to be greater among PLWH with current prescribed opioids, especially immunosuppressive opioids, compared with uninfected patients. However, the overall interaction term for opioid × HIV status was not significant (P = .36).

Although the researchers stated that a limitation of their study was an inability to prove causality or rule out respiratory depression (vs. immunosuppression) as the cause of the increased CAP risk, “the observed effects of opioid immunosuppressive properties and CAP risk lend support to our hypothesis that opioids have clinically relevant immunosuppressive properties.”

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, they were not able to determine whether patients took their prescribed medications appropriately and assess whether the patients took nonmedically prescribed opioids. Also, because men made up such a large portion of the study population, it is unclear whether the results are generalizable to women.

Nevertheless, the study “adds to growing evidence of potential medical harms associated with prescribed opioids,” they wrote.

“Health care professionals should be aware of this additional CAP risk when they prescribe opioids, and future studies should investigate the effects of opioids prescribed for longer durations and on other immune-related outcomes,” wrote Dr. Edelman and her colleagues. “Understanding whether mitigating the risk of prescribed opioids for CAP is possible by using a lower dose and nonimmunosuppressive opioids awaits further study.”

However, without such data, when prescribed opioids are warranted, physicians should attempt to modify other factors known to affect CAP risk, including smoking and lack of vaccination, Dr. Edelman and her colleagues concluded.

Several U.S. government agencies and Yale University provided funding for the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Edelman EJ et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6101.

Prescribed opioids were associated with an increase in community-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without HIV infection, according to results of a large database study.

People living with HIV (PLWH) appeared to have a greater community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) risk at lower opioid doses and particularly with immunosuppressive opioids compared with uninfected patients, although the difference was not significant, E. Jennifer Edelman, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers performed a nested case-control study comprising 25,392 participants (98.9% men; mean age, 55 years) in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2012.

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues compared the characteristics of 4,246 CAP cases with those of 21,146 uninfected controls in the sample. They also compared cases and controls by HIV status. They ran bivariate and multivariate analysis to estimate odds ratios for CAP risk associated with opioid exposure. In addition, the researchers ran models stratified by HIV status and formally checked for an interaction between prescribed opioid characteristics and HIV status.

In unadjusted logistic regression, prescribed opioids were associated with increased odds of CAP, with the greatest risk observed with currently prescribed opioids, compared with past prescribed opioids or no opioids.

Prescribed opioids remained associated with CAP in the adjusted models for past unknown or nonimmunosuppressive (adjusted OR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.40) and past immunosuppressive opioid use (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.67).

For currently prescribed opioids, nonimmunosuppressive or unknown, the aOR was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.03-1.48). For currently prescribed immunosuppressive opioids, the aOR was 3.18 (95% CI, 2.44-4.14).

The researchers also found evidence of a dose-response effect such that currently prescribed high-dose opioids were associated with the greatest CAP risk, followed by medium- and then by low-dose opioids, whether immunosuppressive or not.

With regard to the effect of HIV status in stratified, adjusted analyses, CAP risk tended to be greater among PLWH with current prescribed opioids, especially immunosuppressive opioids, compared with uninfected patients. However, the overall interaction term for opioid × HIV status was not significant (P = .36).

Although the researchers stated that a limitation of their study was an inability to prove causality or rule out respiratory depression (vs. immunosuppression) as the cause of the increased CAP risk, “the observed effects of opioid immunosuppressive properties and CAP risk lend support to our hypothesis that opioids have clinically relevant immunosuppressive properties.”

Dr. Edelman and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, they were not able to determine whether patients took their prescribed medications appropriately and assess whether the patients took nonmedically prescribed opioids. Also, because men made up such a large portion of the study population, it is unclear whether the results are generalizable to women.

Nevertheless, the study “adds to growing evidence of potential medical harms associated with prescribed opioids,” they wrote.

“Health care professionals should be aware of this additional CAP risk when they prescribe opioids, and future studies should investigate the effects of opioids prescribed for longer durations and on other immune-related outcomes,” wrote Dr. Edelman and her colleagues. “Understanding whether mitigating the risk of prescribed opioids for CAP is possible by using a lower dose and nonimmunosuppressive opioids awaits further study.”

However, without such data, when prescribed opioids are warranted, physicians should attempt to modify other factors known to affect CAP risk, including smoking and lack of vaccination, Dr. Edelman and her colleagues concluded.

Several U.S. government agencies and Yale University provided funding for the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Edelman EJ et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6101.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Prescribed opioids, especially those with immunosuppressive properties, are associated with increased community-acquired pneumonia risk.

Major finding: For currently prescribed immunosuppressive opioids, the adjusted odds ratio for community-acquired pneumonia was 3.18 (95% confidence interval, 2.44-4.14).

Study details: A nested case-control study of 25,392 patients in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2012.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by a variety of government organizations and Yale University, New Haven, Conn. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Edelman EJ et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6101.

COPD linked to higher in-hospital death rates in patients with PAD

A growing body of evidence suggests that, along with other vascular beds, smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affect the arteries of the lower limbs in terms of the development of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), reported Karsten Keller, MD, of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (Germany) and his colleagues.

This provided the rationale for their large database analysis of inpatients with concomitant COPD and PAD. They found that the additional presence of COPD was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with PAD.

“Our data suggest that COPD increased the mortality of PAD patients by the factor 1.2-fold,” they wrote in Respiratory Medicine. “Unexpectedly, this increase was not driven by [myocardial infarction] as the life-threatening acute presentation of [coronary artery disease], but rather related to an increased risk for [pulmonary embolism] and a higher coprevalence of cancer.”

Dr. Keller and his colleagues inspected the German inpatient national database based on ICD codes. They identified 5,611,827 adult inpatients (64.8% men) diagnosed with PAD between January 2005 and December 2015, and of those, 13.6% also were coded for COPD. Overall, 277,894 PAD patients (5.0%) died in the hospital, Dr. Keller and his colleagues wrote.

The all-cause, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in PAD patients with COPD, compared with those without COPD (6.5% vs. 4.7%, respectively; P less than .001), and cardiovascular events comprising pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and myocardial infarction (MI) occurred more often in coprevalence with PAD and COPD than in PAD without COPD.

In PAD patients, COPD was an independent predictor of in-hospital death (odds ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.17; P less than .001) as well as an independent predictor for PE (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.40-1.49; P less than .001).

Overall, PAD patients with COPD were of similar age as (73 years), but stayed slightly longer in the hospital than (9 vs. 8 days), those without COPD. PAD patients without COPD revealed more often cardiovascular risk factors like essential arterial hypertension and diabetes, but the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease and heart failure were more often found in PAD patients with COPD. In addition, cancer and renal insufficiency also were more common in PAD patients with COPD, according to the authors.

“Remarkably, PAD patients with COPD showed more frequently lower PAD stages than those without COPD. Especially, PAD stage IV was more prevalent in PAD patients without COPD (19.6% vs. 13.8%; P less than 0.001),” the authors stated. In addition, amputations were more often performed in PAD patients without COPD.

Dr. Keller and his colleagues had the following conclusions regarding the clinical implications of their study: “I) PAD patients with long-standing tobacco use might benefit from COPD screening and treatment. II) PAD patients with additional COPD should be monitored more intensively, and the treatment for COPD should be optimized. III) COPD increases the risk for PE, and it is critical not to overlook this life-threatening disease. IV) MI and PE are important causes of in-hospital death in PAD patients with and without COPD.”

The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research funded the study, and the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Respir Med. 2019 Feb;147:1-6.

A growing body of evidence suggests that, along with other vascular beds, smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affect the arteries of the lower limbs in terms of the development of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), reported Karsten Keller, MD, of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (Germany) and his colleagues.

This provided the rationale for their large database analysis of inpatients with concomitant COPD and PAD. They found that the additional presence of COPD was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with PAD.

“Our data suggest that COPD increased the mortality of PAD patients by the factor 1.2-fold,” they wrote in Respiratory Medicine. “Unexpectedly, this increase was not driven by [myocardial infarction] as the life-threatening acute presentation of [coronary artery disease], but rather related to an increased risk for [pulmonary embolism] and a higher coprevalence of cancer.”

Dr. Keller and his colleagues inspected the German inpatient national database based on ICD codes. They identified 5,611,827 adult inpatients (64.8% men) diagnosed with PAD between January 2005 and December 2015, and of those, 13.6% also were coded for COPD. Overall, 277,894 PAD patients (5.0%) died in the hospital, Dr. Keller and his colleagues wrote.

The all-cause, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in PAD patients with COPD, compared with those without COPD (6.5% vs. 4.7%, respectively; P less than .001), and cardiovascular events comprising pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and myocardial infarction (MI) occurred more often in coprevalence with PAD and COPD than in PAD without COPD.

In PAD patients, COPD was an independent predictor of in-hospital death (odds ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.17; P less than .001) as well as an independent predictor for PE (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.40-1.49; P less than .001).

Overall, PAD patients with COPD were of similar age as (73 years), but stayed slightly longer in the hospital than (9 vs. 8 days), those without COPD. PAD patients without COPD revealed more often cardiovascular risk factors like essential arterial hypertension and diabetes, but the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease and heart failure were more often found in PAD patients with COPD. In addition, cancer and renal insufficiency also were more common in PAD patients with COPD, according to the authors.

“Remarkably, PAD patients with COPD showed more frequently lower PAD stages than those without COPD. Especially, PAD stage IV was more prevalent in PAD patients without COPD (19.6% vs. 13.8%; P less than 0.001),” the authors stated. In addition, amputations were more often performed in PAD patients without COPD.

Dr. Keller and his colleagues had the following conclusions regarding the clinical implications of their study: “I) PAD patients with long-standing tobacco use might benefit from COPD screening and treatment. II) PAD patients with additional COPD should be monitored more intensively, and the treatment for COPD should be optimized. III) COPD increases the risk for PE, and it is critical not to overlook this life-threatening disease. IV) MI and PE are important causes of in-hospital death in PAD patients with and without COPD.”

The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research funded the study, and the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Respir Med. 2019 Feb;147:1-6.

A growing body of evidence suggests that, along with other vascular beds, smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affect the arteries of the lower limbs in terms of the development of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), reported Karsten Keller, MD, of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (Germany) and his colleagues.

This provided the rationale for their large database analysis of inpatients with concomitant COPD and PAD. They found that the additional presence of COPD was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with PAD.

“Our data suggest that COPD increased the mortality of PAD patients by the factor 1.2-fold,” they wrote in Respiratory Medicine. “Unexpectedly, this increase was not driven by [myocardial infarction] as the life-threatening acute presentation of [coronary artery disease], but rather related to an increased risk for [pulmonary embolism] and a higher coprevalence of cancer.”

Dr. Keller and his colleagues inspected the German inpatient national database based on ICD codes. They identified 5,611,827 adult inpatients (64.8% men) diagnosed with PAD between January 2005 and December 2015, and of those, 13.6% also were coded for COPD. Overall, 277,894 PAD patients (5.0%) died in the hospital, Dr. Keller and his colleagues wrote.

The all-cause, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in PAD patients with COPD, compared with those without COPD (6.5% vs. 4.7%, respectively; P less than .001), and cardiovascular events comprising pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and myocardial infarction (MI) occurred more often in coprevalence with PAD and COPD than in PAD without COPD.

In PAD patients, COPD was an independent predictor of in-hospital death (odds ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.17; P less than .001) as well as an independent predictor for PE (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.40-1.49; P less than .001).

Overall, PAD patients with COPD were of similar age as (73 years), but stayed slightly longer in the hospital than (9 vs. 8 days), those without COPD. PAD patients without COPD revealed more often cardiovascular risk factors like essential arterial hypertension and diabetes, but the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease and heart failure were more often found in PAD patients with COPD. In addition, cancer and renal insufficiency also were more common in PAD patients with COPD, according to the authors.

“Remarkably, PAD patients with COPD showed more frequently lower PAD stages than those without COPD. Especially, PAD stage IV was more prevalent in PAD patients without COPD (19.6% vs. 13.8%; P less than 0.001),” the authors stated. In addition, amputations were more often performed in PAD patients without COPD.

Dr. Keller and his colleagues had the following conclusions regarding the clinical implications of their study: “I) PAD patients with long-standing tobacco use might benefit from COPD screening and treatment. II) PAD patients with additional COPD should be monitored more intensively, and the treatment for COPD should be optimized. III) COPD increases the risk for PE, and it is critical not to overlook this life-threatening disease. IV) MI and PE are important causes of in-hospital death in PAD patients with and without COPD.”

The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research funded the study, and the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Respir Med. 2019 Feb;147:1-6.

FROM RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All-cause, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in PAD patients with COPD, compared with those without (6.5% vs. 4.7%; P less than 0.001).

Study details: Database analysis of 5.6 million German PAD inpatients stratified for COPD.

Disclosures: The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research funded the study, and the authors reported having no conflicts.

Source: Keller K et al. Respir Med. 2019 Feb;147:1-6.

In the Literature: Short Takes

A second medical emergency team (MET) activation more likely in patients with recent MET activation

A prospective cohort study examined 471 MET activatios where the patient was not transferred to a higher level of care found that 18% had a second MET event. These second events were more likely to occur in the first 8-12 hours and to occur in patients recently discharged from the ICU.

Citation: Still MD et al. Predictors of a second medical emergency team activation within 24 hours of index event. J Nurs Care Qual 2018;33(2): 157-65

Risk of CV events in patients with TIA or minor stroke decreases significantly after first year

A prospective cohort study following TIA or minor stroke patients from the TIAregistry.org project shows that the risk of additional events (death from cardiovascular cause, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal acute coronary syndrome) in the following 5 years is 12.9% with half of those events occuring in the first year.

Citation: Amarenco P et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-90.

Maintenance of certification associated with better physician performance scores

Physicians who still participated in Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs 20 years after their initial certification scored higher on a variety of physician performance scores on Medicare patients.

Citation: Gray BG et al. Associations between American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certificate status and performance on a set of healthcare effectiveness data and information set (HEDIS) process measures. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):97-105.

A second medical emergency team (MET) activation more likely in patients with recent MET activation

A prospective cohort study examined 471 MET activatios where the patient was not transferred to a higher level of care found that 18% had a second MET event. These second events were more likely to occur in the first 8-12 hours and to occur in patients recently discharged from the ICU.

Citation: Still MD et al. Predictors of a second medical emergency team activation within 24 hours of index event. J Nurs Care Qual 2018;33(2): 157-65

Risk of CV events in patients with TIA or minor stroke decreases significantly after first year

A prospective cohort study following TIA or minor stroke patients from the TIAregistry.org project shows that the risk of additional events (death from cardiovascular cause, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal acute coronary syndrome) in the following 5 years is 12.9% with half of those events occuring in the first year.

Citation: Amarenco P et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-90.

Maintenance of certification associated with better physician performance scores

Physicians who still participated in Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs 20 years after their initial certification scored higher on a variety of physician performance scores on Medicare patients.

Citation: Gray BG et al. Associations between American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certificate status and performance on a set of healthcare effectiveness data and information set (HEDIS) process measures. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):97-105.

A second medical emergency team (MET) activation more likely in patients with recent MET activation

A prospective cohort study examined 471 MET activatios where the patient was not transferred to a higher level of care found that 18% had a second MET event. These second events were more likely to occur in the first 8-12 hours and to occur in patients recently discharged from the ICU.

Citation: Still MD et al. Predictors of a second medical emergency team activation within 24 hours of index event. J Nurs Care Qual 2018;33(2): 157-65

Risk of CV events in patients with TIA or minor stroke decreases significantly after first year

A prospective cohort study following TIA or minor stroke patients from the TIAregistry.org project shows that the risk of additional events (death from cardiovascular cause, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal acute coronary syndrome) in the following 5 years is 12.9% with half of those events occuring in the first year.

Citation: Amarenco P et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-90.

Maintenance of certification associated with better physician performance scores

Physicians who still participated in Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs 20 years after their initial certification scored higher on a variety of physician performance scores on Medicare patients.

Citation: Gray BG et al. Associations between American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certificate status and performance on a set of healthcare effectiveness data and information set (HEDIS) process measures. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):97-105.

CTPA may not rule out VTE in high-risk patients

Clinical question: Does a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography rule out venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the most common diagnostic modality used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) and has a high negative predictive value in patients with a low 3-month risk of VTE. In patients with higher pretest probability of PE, it is unknown whether CTPA is sufficient to rule out VTE.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Published prospective outcome studies of patients with suspected PE using CTPA as a diagnostic strategy.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 3,143 publications from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library and identified 22 prospective outcome studies to include in their meta-analysis. A VTE was diagnosed in 3,923 out of 11,872 participants (33%) using CTPA. Of the 7,863 patients with a negative CTPA, 148 patients had an acute VTE confirmed by venous ultrasound, ventilation/perfusion scan, or angiography, and 74 patients experienced VTE during a 3-month follow-up period, yielding an overall proportion of 2.4% of patients (95% confidence interval, 1.3%-3.8%).

Subgroup analysis showed that cumulative occurrence of VTE was related to pretest prevalence. In the subgroup of patients with a VTE prevalence greater than 40%, VTE was observed in 8.1% of patients with a negative CTPA (95% CI, 3.4%-14.5%).

Bottom line: CTPA may be insufficient to rule out VTE in patients with a high pretest probability of PE.

Citation: Belzile D et al. Outcomes following a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography according to pulmonary embolism prevalence: a meta-analysisof the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Jun;16(6):1107-20.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Does a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography rule out venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the most common diagnostic modality used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) and has a high negative predictive value in patients with a low 3-month risk of VTE. In patients with higher pretest probability of PE, it is unknown whether CTPA is sufficient to rule out VTE.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Published prospective outcome studies of patients with suspected PE using CTPA as a diagnostic strategy.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 3,143 publications from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library and identified 22 prospective outcome studies to include in their meta-analysis. A VTE was diagnosed in 3,923 out of 11,872 participants (33%) using CTPA. Of the 7,863 patients with a negative CTPA, 148 patients had an acute VTE confirmed by venous ultrasound, ventilation/perfusion scan, or angiography, and 74 patients experienced VTE during a 3-month follow-up period, yielding an overall proportion of 2.4% of patients (95% confidence interval, 1.3%-3.8%).

Subgroup analysis showed that cumulative occurrence of VTE was related to pretest prevalence. In the subgroup of patients with a VTE prevalence greater than 40%, VTE was observed in 8.1% of patients with a negative CTPA (95% CI, 3.4%-14.5%).

Bottom line: CTPA may be insufficient to rule out VTE in patients with a high pretest probability of PE.

Citation: Belzile D et al. Outcomes following a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography according to pulmonary embolism prevalence: a meta-analysisof the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Jun;16(6):1107-20.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Does a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography rule out venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the most common diagnostic modality used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) and has a high negative predictive value in patients with a low 3-month risk of VTE. In patients with higher pretest probability of PE, it is unknown whether CTPA is sufficient to rule out VTE.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Published prospective outcome studies of patients with suspected PE using CTPA as a diagnostic strategy.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 3,143 publications from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library and identified 22 prospective outcome studies to include in their meta-analysis. A VTE was diagnosed in 3,923 out of 11,872 participants (33%) using CTPA. Of the 7,863 patients with a negative CTPA, 148 patients had an acute VTE confirmed by venous ultrasound, ventilation/perfusion scan, or angiography, and 74 patients experienced VTE during a 3-month follow-up period, yielding an overall proportion of 2.4% of patients (95% confidence interval, 1.3%-3.8%).

Subgroup analysis showed that cumulative occurrence of VTE was related to pretest prevalence. In the subgroup of patients with a VTE prevalence greater than 40%, VTE was observed in 8.1% of patients with a negative CTPA (95% CI, 3.4%-14.5%).

Bottom line: CTPA may be insufficient to rule out VTE in patients with a high pretest probability of PE.

Citation: Belzile D et al. Outcomes following a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography according to pulmonary embolism prevalence: a meta-analysisof the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Jun;16(6):1107-20.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

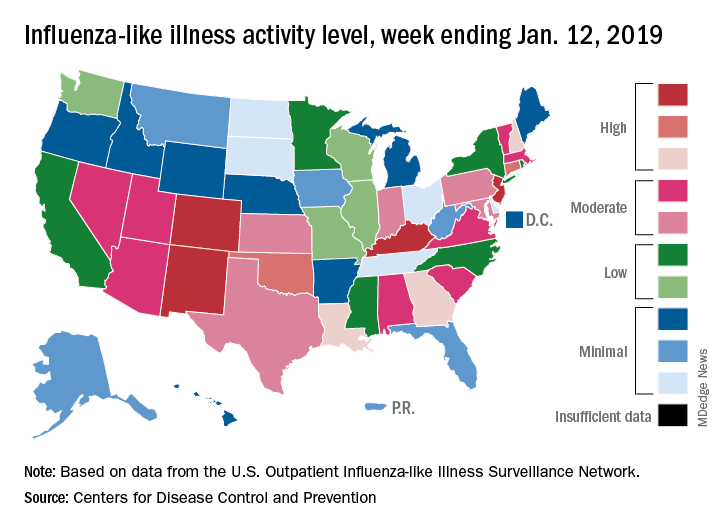

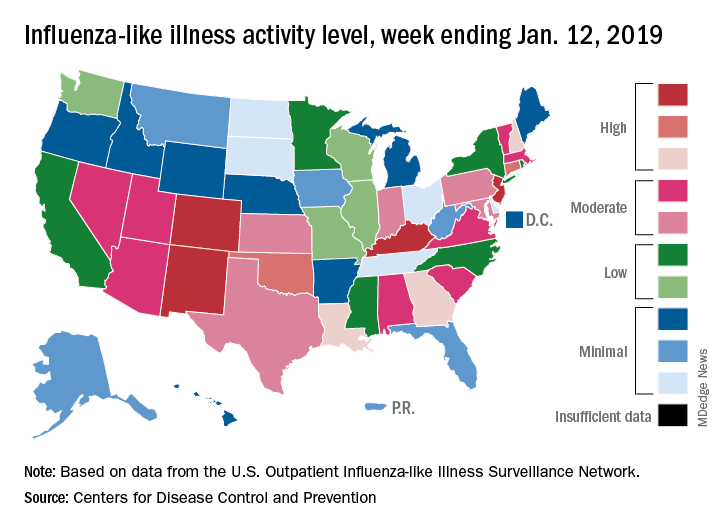

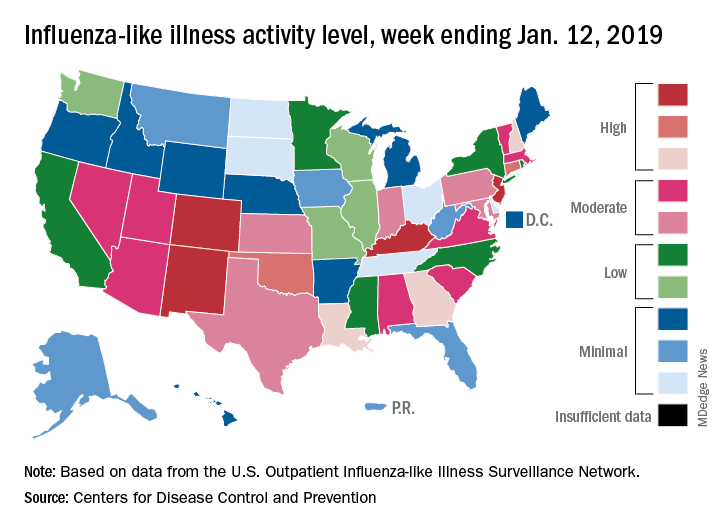

Flu activity down for second consecutive week

The second week of the new year brought a second straight week of declining activity for the 2018-2019 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 3.1% for the week ending Jan. 12, 2019, down from 3.5% the previous week but still above the national baseline level of 2.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 18.

Activity was also down at the state level. There were 4 states – Colorado, Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for ILI activity, compared with 10 the week before, and a total of 9 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 15 the previous week, data from the influenza division show.

Reports of total influenza deaths, which lag a week behind other measures, continue to rise: 111 for the week ending Jan. 5, although reporting is only 72% complete. There were 89 deaths during the previous week, with reporting 82% complete so far. Total flu-related deaths among children are up to 19 for the 2018-2019 season after three more were reported during the week ending Jan. 12, the CDC said. Influenza deaths from the comparable weeks of the much more severe 2017-2018 season were 1,163 for all ages and 10 for children.

The second week of the new year brought a second straight week of declining activity for the 2018-2019 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 3.1% for the week ending Jan. 12, 2019, down from 3.5% the previous week but still above the national baseline level of 2.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 18.

Activity was also down at the state level. There were 4 states – Colorado, Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for ILI activity, compared with 10 the week before, and a total of 9 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 15 the previous week, data from the influenza division show.

Reports of total influenza deaths, which lag a week behind other measures, continue to rise: 111 for the week ending Jan. 5, although reporting is only 72% complete. There were 89 deaths during the previous week, with reporting 82% complete so far. Total flu-related deaths among children are up to 19 for the 2018-2019 season after three more were reported during the week ending Jan. 12, the CDC said. Influenza deaths from the comparable weeks of the much more severe 2017-2018 season were 1,163 for all ages and 10 for children.

The second week of the new year brought a second straight week of declining activity for the 2018-2019 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 3.1% for the week ending Jan. 12, 2019, down from 3.5% the previous week but still above the national baseline level of 2.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 18.

Activity was also down at the state level. There were 4 states – Colorado, Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for ILI activity, compared with 10 the week before, and a total of 9 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 15 the previous week, data from the influenza division show.

Reports of total influenza deaths, which lag a week behind other measures, continue to rise: 111 for the week ending Jan. 5, although reporting is only 72% complete. There were 89 deaths during the previous week, with reporting 82% complete so far. Total flu-related deaths among children are up to 19 for the 2018-2019 season after three more were reported during the week ending Jan. 12, the CDC said. Influenza deaths from the comparable weeks of the much more severe 2017-2018 season were 1,163 for all ages and 10 for children.

Intramuscular midazolam superior in sedating acutely agitated adults

Clinical question: How effective are intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and haloperidol at sedating acutely agitated adults in the emergency department?

Background: Acute agitation is commonly seen in the ED and sometimes requires parenteral medications to keep patients and staff safe. Although many medications, including benzodiazepines and antipsychotics, are used, there is no consensus regarding which medications are most effective and safe for acute agitation.

Study design: Prospective observational study.

Setting: Emergency department of an inner-city Level 1 adult and pediatric trauma center.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 737 adults in the ED who presented with acute agitation and treated them with either haloperidol 5 mg, ziprasidone 20 mg, olanzapine 10 mg, midazolam 5 mg, or haloperidol 10 mg intramuscularly, based on predetermined 3-week blocks. The main outcome was the proportion of patients adequately sedated at 15 minutes, based on Altered Mental Status Scale score less than 1. A total of 650 patients (88%) were agitated from alcohol intoxication.

Midazolam resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with ziprasidone (difference, 18%; 95% confidence interval, 6%-29%), haloperidol 5 mg (difference, 30%; 95% CI, 19%-41%), and haloperidol 10 mg (difference, 28%; 95% CI,17%-39%). Midazolam resulted in a higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with olanzapine (difference 9%), but this difference was not statistically significant because the confidence interval crossed 1 (95% CI, –1%-20%). Olanzapine resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with haloperidol 5 mg (difference 20%; 95% CI, 10%-31%) and 10 mg (difference 18%; 95% CI, 7%-29%). Adverse effects were rare.

Bottom line: Intramuscular midazolam is safe and may be more effective for treating acute agitation in the emergency department than standard antipsychotics.

Citation: Klein LR et al. Intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, or haloperidol for treating acute agitation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Jun 6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.027.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: How effective are intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and haloperidol at sedating acutely agitated adults in the emergency department?

Background: Acute agitation is commonly seen in the ED and sometimes requires parenteral medications to keep patients and staff safe. Although many medications, including benzodiazepines and antipsychotics, are used, there is no consensus regarding which medications are most effective and safe for acute agitation.

Study design: Prospective observational study.

Setting: Emergency department of an inner-city Level 1 adult and pediatric trauma center.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 737 adults in the ED who presented with acute agitation and treated them with either haloperidol 5 mg, ziprasidone 20 mg, olanzapine 10 mg, midazolam 5 mg, or haloperidol 10 mg intramuscularly, based on predetermined 3-week blocks. The main outcome was the proportion of patients adequately sedated at 15 minutes, based on Altered Mental Status Scale score less than 1. A total of 650 patients (88%) were agitated from alcohol intoxication.

Midazolam resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with ziprasidone (difference, 18%; 95% confidence interval, 6%-29%), haloperidol 5 mg (difference, 30%; 95% CI, 19%-41%), and haloperidol 10 mg (difference, 28%; 95% CI,17%-39%). Midazolam resulted in a higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with olanzapine (difference 9%), but this difference was not statistically significant because the confidence interval crossed 1 (95% CI, –1%-20%). Olanzapine resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with haloperidol 5 mg (difference 20%; 95% CI, 10%-31%) and 10 mg (difference 18%; 95% CI, 7%-29%). Adverse effects were rare.

Bottom line: Intramuscular midazolam is safe and may be more effective for treating acute agitation in the emergency department than standard antipsychotics.

Citation: Klein LR et al. Intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, or haloperidol for treating acute agitation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Jun 6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.027.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: How effective are intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and haloperidol at sedating acutely agitated adults in the emergency department?

Background: Acute agitation is commonly seen in the ED and sometimes requires parenteral medications to keep patients and staff safe. Although many medications, including benzodiazepines and antipsychotics, are used, there is no consensus regarding which medications are most effective and safe for acute agitation.

Study design: Prospective observational study.

Setting: Emergency department of an inner-city Level 1 adult and pediatric trauma center.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 737 adults in the ED who presented with acute agitation and treated them with either haloperidol 5 mg, ziprasidone 20 mg, olanzapine 10 mg, midazolam 5 mg, or haloperidol 10 mg intramuscularly, based on predetermined 3-week blocks. The main outcome was the proportion of patients adequately sedated at 15 minutes, based on Altered Mental Status Scale score less than 1. A total of 650 patients (88%) were agitated from alcohol intoxication.

Midazolam resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with ziprasidone (difference, 18%; 95% confidence interval, 6%-29%), haloperidol 5 mg (difference, 30%; 95% CI, 19%-41%), and haloperidol 10 mg (difference, 28%; 95% CI,17%-39%). Midazolam resulted in a higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with olanzapine (difference 9%), but this difference was not statistically significant because the confidence interval crossed 1 (95% CI, –1%-20%). Olanzapine resulted in a statistically higher proportion of patients adequately sedated, compared with haloperidol 5 mg (difference 20%; 95% CI, 10%-31%) and 10 mg (difference 18%; 95% CI, 7%-29%). Adverse effects were rare.

Bottom line: Intramuscular midazolam is safe and may be more effective for treating acute agitation in the emergency department than standard antipsychotics.

Citation: Klein LR et al. Intramuscular midazolam, olanzapine, ziprasidone, or haloperidol for treating acute agitation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Jun 6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.027.

Dr. Jenkins is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.