User login

Rivaroxaban no help for heart failure outcomes

MUNICH – For patients with heart disease, coronary artery disease, and normal sinus rhythm, giving , investigators in the COMMANDER trial said.

Rivaroxaban did not improve rehospitalization rates either, reported lead author Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from the University of Henri Poincaré in Nancy, France, and his co-investigators.

“After an episode of worsening chronic heart failure, rates of readmission to the hospital and of death are high, especially in the first few months,” they said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The report of the research was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Findings from previous research have suggested that, for patients with coronary artery disease, a combination of antiplatelet agents and low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) reduced incidence of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The authors designed the COMMANDER trial to test a similar regimen in patients with chronic heart failure and coronary heart disease without an arrhythmia. Results were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The COMMANDER trial involved 5,022 patients with coronary artery disease, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (less than or equal to 40%), worsening chronic heart failure (index event within past 21 days), and normal splasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of at least 200 ng per liter or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) of at least 800 ng per liter.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily (n = 2,507) or placebo (n = 2,515). Treatment was given in addition to standard care for coronary disease or heart failure (single or dual antiplatelet therapy was allowed). Patients were assessed at week 4 and week 12, then every 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from any cause. Secondary efficacy outcomes included death from cardiovascular disease, rehospitalization for heart failure, a composite of either, or rehospitalization for cardiovascular events. The principal safety outcome was a composite of bleeding into a critical space with potential for permanent disability or fatal bleeding.

Death, myocardial failure, or stroke occurred in 626 patients (25%) in the rivaroxaban group compared with 658 patients (26.2%) in the placebo group (P = .27). Secondary efficacy outcomes were also highly similar between groups, differing at most by 0.9%. The principal safety outcome (fatal bleeding or bleeding into a critical space) occurred in 18 patients (0.7%) in the rivaroxaban group and 23 patients (0.9%) in the placebo group (P = .25). Again, no significant difference was found between groups.

These results suggest that while low-dose rivaroxaban may be safe, it also offers no treatment benefit. “The most likely reason for the failure … is that thrombin-mediated events are not the major driver of heart failure-related events in patients with recent hospitalization for heart failure,” the authors wrote.

“Whether a higher dose of rivaroxaban could have led to a more favorable outcome remains unknown,” they concluded.

The COMMANDER trial was funded by Janssen Research and Development. Authors reported compensation from Bayer, Servier, Novartis, Impulse Dynamics, and others.

SOURCE: Zannad F et al. NEJM/ESC.

.

MUNICH – For patients with heart disease, coronary artery disease, and normal sinus rhythm, giving , investigators in the COMMANDER trial said.

Rivaroxaban did not improve rehospitalization rates either, reported lead author Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from the University of Henri Poincaré in Nancy, France, and his co-investigators.

“After an episode of worsening chronic heart failure, rates of readmission to the hospital and of death are high, especially in the first few months,” they said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The report of the research was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Findings from previous research have suggested that, for patients with coronary artery disease, a combination of antiplatelet agents and low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) reduced incidence of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The authors designed the COMMANDER trial to test a similar regimen in patients with chronic heart failure and coronary heart disease without an arrhythmia. Results were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The COMMANDER trial involved 5,022 patients with coronary artery disease, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (less than or equal to 40%), worsening chronic heart failure (index event within past 21 days), and normal splasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of at least 200 ng per liter or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) of at least 800 ng per liter.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily (n = 2,507) or placebo (n = 2,515). Treatment was given in addition to standard care for coronary disease or heart failure (single or dual antiplatelet therapy was allowed). Patients were assessed at week 4 and week 12, then every 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from any cause. Secondary efficacy outcomes included death from cardiovascular disease, rehospitalization for heart failure, a composite of either, or rehospitalization for cardiovascular events. The principal safety outcome was a composite of bleeding into a critical space with potential for permanent disability or fatal bleeding.

Death, myocardial failure, or stroke occurred in 626 patients (25%) in the rivaroxaban group compared with 658 patients (26.2%) in the placebo group (P = .27). Secondary efficacy outcomes were also highly similar between groups, differing at most by 0.9%. The principal safety outcome (fatal bleeding or bleeding into a critical space) occurred in 18 patients (0.7%) in the rivaroxaban group and 23 patients (0.9%) in the placebo group (P = .25). Again, no significant difference was found between groups.

These results suggest that while low-dose rivaroxaban may be safe, it also offers no treatment benefit. “The most likely reason for the failure … is that thrombin-mediated events are not the major driver of heart failure-related events in patients with recent hospitalization for heart failure,” the authors wrote.

“Whether a higher dose of rivaroxaban could have led to a more favorable outcome remains unknown,” they concluded.

The COMMANDER trial was funded by Janssen Research and Development. Authors reported compensation from Bayer, Servier, Novartis, Impulse Dynamics, and others.

SOURCE: Zannad F et al. NEJM/ESC.

.

MUNICH – For patients with heart disease, coronary artery disease, and normal sinus rhythm, giving , investigators in the COMMANDER trial said.

Rivaroxaban did not improve rehospitalization rates either, reported lead author Faiez Zannad, MD, PhD, from the University of Henri Poincaré in Nancy, France, and his co-investigators.

“After an episode of worsening chronic heart failure, rates of readmission to the hospital and of death are high, especially in the first few months,” they said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The report of the research was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Findings from previous research have suggested that, for patients with coronary artery disease, a combination of antiplatelet agents and low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) reduced incidence of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The authors designed the COMMANDER trial to test a similar regimen in patients with chronic heart failure and coronary heart disease without an arrhythmia. Results were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The COMMANDER trial involved 5,022 patients with coronary artery disease, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (less than or equal to 40%), worsening chronic heart failure (index event within past 21 days), and normal splasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of at least 200 ng per liter or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) of at least 800 ng per liter.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily (n = 2,507) or placebo (n = 2,515). Treatment was given in addition to standard care for coronary disease or heart failure (single or dual antiplatelet therapy was allowed). Patients were assessed at week 4 and week 12, then every 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from any cause. Secondary efficacy outcomes included death from cardiovascular disease, rehospitalization for heart failure, a composite of either, or rehospitalization for cardiovascular events. The principal safety outcome was a composite of bleeding into a critical space with potential for permanent disability or fatal bleeding.

Death, myocardial failure, or stroke occurred in 626 patients (25%) in the rivaroxaban group compared with 658 patients (26.2%) in the placebo group (P = .27). Secondary efficacy outcomes were also highly similar between groups, differing at most by 0.9%. The principal safety outcome (fatal bleeding or bleeding into a critical space) occurred in 18 patients (0.7%) in the rivaroxaban group and 23 patients (0.9%) in the placebo group (P = .25). Again, no significant difference was found between groups.

These results suggest that while low-dose rivaroxaban may be safe, it also offers no treatment benefit. “The most likely reason for the failure … is that thrombin-mediated events are not the major driver of heart failure-related events in patients with recent hospitalization for heart failure,” the authors wrote.

“Whether a higher dose of rivaroxaban could have led to a more favorable outcome remains unknown,” they concluded.

The COMMANDER trial was funded by Janssen Research and Development. Authors reported compensation from Bayer, Servier, Novartis, Impulse Dynamics, and others.

SOURCE: Zannad F et al. NEJM/ESC.

.

Key clinical point: For patients with heart failure and coronary artery disease, rivaroxaban does not significantly reduce the risk of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

Major finding: Death, myocardial failure, or stroke occurred in 25.0% of patients in the rivaroxaban group compared with 26.2% of patients in the placebo group (P = .27).

Study details: The COMMANDER study was a double-blind, randomized trial involving 5,022 patients. Patients had heart failure, normal sinus rhythm, and coronary artery disease.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Authors reported compensation from Bayer, Servier, Novartis, Impulse Dynamics, and others.

Source: Zannad F et al. NEJM/ESC.

VTE risk unchanged by rivaroxaban after discharge

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 0.83% of patients given rivaroxaban, compared with 1.10% of patients given placebo (P = .14).

Study details: The MARINER study was a double-blind, randomized trial involving 12,019 patients. Patients were recently hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

Source: Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

Variety is the spice of hospital medicine

Dr. Raj Sehgal enjoys a variety of roles

Unlike some children who wanted be firefighters or astronauts when they grew up, ever since Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, was a boy, he dreamed of being a doctor.

Since earning his medical degree, Dr. Sehgal has kept himself involved in a wide variety of projects, driven by the desire to diversify his expertise.

Currently a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, and University of Texas Health San Antonio, Dr. Sehgal has found his place as an educator as well as a clinician, earning the Division of Hospital Medicine Teaching Award in 2016.

As a member of the The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board, Dr. Sehgal enjoys helping to educate and inform fellow hospitalists. He spoke with The Hospitalist to tell us more about himself.

How did you get into medicine?

I don’t know how old I was when I decided I was going to be a doctor, but it was at a very young age and I never really wavered in that desire. I guess I also would have wanted to be a baseball player or a musician, but I never had the talents for those, so it was doctor. That’s always what I was thinking of doing, straight through high school and college, and then after college I took a year off and joined AmeriCorps. I spent a year there and then went to medical school in Dallas at UT Southwestern. After medical school, I thought I should go somewhere as different from Dallas as possible, so I went to Portland, Ore., for my residency and then a fellowship in general internal medicine.

How did you end up in hospital medicine?

When I was doing my residency, I always enjoyed being a generalist. A lot of different areas of medicine interested me, but I like the breadth of things you encounter as a generalist, so I could never picture myself being a subspecialist, doing the same things every day, seeing the same things. I knew I wanted to keep practicing general internal medicine, so I took a fellowship where I was working both inpatient and outpatient, and when I was looking for a job, I sought out things that involved some inpatient and some outpatient work. It turned out hospital medicine was the best fit.

What would you say is your favorite part of hospital medicine?

My favorite part of the job is getting to teach, working with medical students and residents. I also like the variety of what I do as a hospitalist, so I’m about 50% clinical and the rest of the time I perform a variety of tasks, both administrative and educational.

What about your least favorite part of hospitalist work?

Sometimes, particularly if you’re doing clinical, educational, and administrative work, it can be a little overwhelming to try and do a little bit of everything. I think generally that’s a good thing, but sometimes it can feel like a little too much.

What is some of the best advice you have received regarding how to handle the stresses of hospital medicine?

Feel free to say no to things. When hospitalists are starting their careers, and particularly when they are new to a job and trying to express their desire to get involved, sometimes they can have too much thrown at them at once. People can get overloaded very quickly, so I think feeling like you’re able to say no to some requests, or to take some time to think before you accept an additional role. The other piece of advice I remember from my fellowship, is that, when you do something, make it count twice. For example, if you’re involved in a project, you get the practical clinical or educational benefits of whatever the project was. But also think about how you might write about your experience for research purposes, such as for a poster, article, or other presentation.

What is the worst advice you have been given?

I think it’s not necessarily bad advice, but I guess it’s advice that I haven’t really followed. Since I work in academic medicine, I’ve found that the people in academics fall into one of two categories: There are the people who find their niche and remain on that path, and they’re very clear about it and don’t really stray from it; and there are people who don’t find that niche right away. I think the advice I received when starting out was to try to find that niche, and if you’re building an academic career it is very helpful to have these things in which you have become the expert. But I’ve just tried to go where the job takes me. I don’t necessarily have a single academic niche or something that I spend all my time doing, but I do have my hand in a lot of different things. To me, that’s a lot more interesting because it adds to the variety of what you’re doing. Every day is a little different.

What else do you do professionally outside of hospital medicine?

I actually practice a little outpatient medicine. When I first started here, I wanted to keep some outpatient experience, and so I actually created my own clinic. It’s a procedure clinic where I do paracentesis on people who have cirrhosis. Then on the educational side, I sit on the admission committees for the medical school here, so I get to look through the applicants and choose who we interview, and then once we interview candidates, I help choose how we rank students for admission.

Where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

I’ve never been one who looks at a particular job and says ‘Okay, I want to be the dean or have this position.’ I guess I just hope I’m better at the things I’m currently doing. I hope in 10 years that I’m a better teacher, that I’ll have learned more strategies to help more people, and that I have a better handle on the administrative side of the work. I hope I’ve progressed to a point in my career where I’m doing an even better job than I am now.

What are your goals as a member of the editorial board?

I have an interest not only in medicine but also in writing; I’ve gotten to do some writing both medical and nonmedical in the past. I’ve published a few articles in The Hospitalist, and hopefully, I can do more of that because writing is just another part of education.

Dr. Raj Sehgal enjoys a variety of roles

Dr. Raj Sehgal enjoys a variety of roles

Unlike some children who wanted be firefighters or astronauts when they grew up, ever since Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, was a boy, he dreamed of being a doctor.

Since earning his medical degree, Dr. Sehgal has kept himself involved in a wide variety of projects, driven by the desire to diversify his expertise.

Currently a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, and University of Texas Health San Antonio, Dr. Sehgal has found his place as an educator as well as a clinician, earning the Division of Hospital Medicine Teaching Award in 2016.

As a member of the The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board, Dr. Sehgal enjoys helping to educate and inform fellow hospitalists. He spoke with The Hospitalist to tell us more about himself.

How did you get into medicine?

I don’t know how old I was when I decided I was going to be a doctor, but it was at a very young age and I never really wavered in that desire. I guess I also would have wanted to be a baseball player or a musician, but I never had the talents for those, so it was doctor. That’s always what I was thinking of doing, straight through high school and college, and then after college I took a year off and joined AmeriCorps. I spent a year there and then went to medical school in Dallas at UT Southwestern. After medical school, I thought I should go somewhere as different from Dallas as possible, so I went to Portland, Ore., for my residency and then a fellowship in general internal medicine.

How did you end up in hospital medicine?

When I was doing my residency, I always enjoyed being a generalist. A lot of different areas of medicine interested me, but I like the breadth of things you encounter as a generalist, so I could never picture myself being a subspecialist, doing the same things every day, seeing the same things. I knew I wanted to keep practicing general internal medicine, so I took a fellowship where I was working both inpatient and outpatient, and when I was looking for a job, I sought out things that involved some inpatient and some outpatient work. It turned out hospital medicine was the best fit.

What would you say is your favorite part of hospital medicine?

My favorite part of the job is getting to teach, working with medical students and residents. I also like the variety of what I do as a hospitalist, so I’m about 50% clinical and the rest of the time I perform a variety of tasks, both administrative and educational.

What about your least favorite part of hospitalist work?

Sometimes, particularly if you’re doing clinical, educational, and administrative work, it can be a little overwhelming to try and do a little bit of everything. I think generally that’s a good thing, but sometimes it can feel like a little too much.

What is some of the best advice you have received regarding how to handle the stresses of hospital medicine?

Feel free to say no to things. When hospitalists are starting their careers, and particularly when they are new to a job and trying to express their desire to get involved, sometimes they can have too much thrown at them at once. People can get overloaded very quickly, so I think feeling like you’re able to say no to some requests, or to take some time to think before you accept an additional role. The other piece of advice I remember from my fellowship, is that, when you do something, make it count twice. For example, if you’re involved in a project, you get the practical clinical or educational benefits of whatever the project was. But also think about how you might write about your experience for research purposes, such as for a poster, article, or other presentation.

What is the worst advice you have been given?

I think it’s not necessarily bad advice, but I guess it’s advice that I haven’t really followed. Since I work in academic medicine, I’ve found that the people in academics fall into one of two categories: There are the people who find their niche and remain on that path, and they’re very clear about it and don’t really stray from it; and there are people who don’t find that niche right away. I think the advice I received when starting out was to try to find that niche, and if you’re building an academic career it is very helpful to have these things in which you have become the expert. But I’ve just tried to go where the job takes me. I don’t necessarily have a single academic niche or something that I spend all my time doing, but I do have my hand in a lot of different things. To me, that’s a lot more interesting because it adds to the variety of what you’re doing. Every day is a little different.

What else do you do professionally outside of hospital medicine?

I actually practice a little outpatient medicine. When I first started here, I wanted to keep some outpatient experience, and so I actually created my own clinic. It’s a procedure clinic where I do paracentesis on people who have cirrhosis. Then on the educational side, I sit on the admission committees for the medical school here, so I get to look through the applicants and choose who we interview, and then once we interview candidates, I help choose how we rank students for admission.

Where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

I’ve never been one who looks at a particular job and says ‘Okay, I want to be the dean or have this position.’ I guess I just hope I’m better at the things I’m currently doing. I hope in 10 years that I’m a better teacher, that I’ll have learned more strategies to help more people, and that I have a better handle on the administrative side of the work. I hope I’ve progressed to a point in my career where I’m doing an even better job than I am now.

What are your goals as a member of the editorial board?

I have an interest not only in medicine but also in writing; I’ve gotten to do some writing both medical and nonmedical in the past. I’ve published a few articles in The Hospitalist, and hopefully, I can do more of that because writing is just another part of education.

Unlike some children who wanted be firefighters or astronauts when they grew up, ever since Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, was a boy, he dreamed of being a doctor.

Since earning his medical degree, Dr. Sehgal has kept himself involved in a wide variety of projects, driven by the desire to diversify his expertise.

Currently a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, and University of Texas Health San Antonio, Dr. Sehgal has found his place as an educator as well as a clinician, earning the Division of Hospital Medicine Teaching Award in 2016.

As a member of the The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board, Dr. Sehgal enjoys helping to educate and inform fellow hospitalists. He spoke with The Hospitalist to tell us more about himself.

How did you get into medicine?

I don’t know how old I was when I decided I was going to be a doctor, but it was at a very young age and I never really wavered in that desire. I guess I also would have wanted to be a baseball player or a musician, but I never had the talents for those, so it was doctor. That’s always what I was thinking of doing, straight through high school and college, and then after college I took a year off and joined AmeriCorps. I spent a year there and then went to medical school in Dallas at UT Southwestern. After medical school, I thought I should go somewhere as different from Dallas as possible, so I went to Portland, Ore., for my residency and then a fellowship in general internal medicine.

How did you end up in hospital medicine?

When I was doing my residency, I always enjoyed being a generalist. A lot of different areas of medicine interested me, but I like the breadth of things you encounter as a generalist, so I could never picture myself being a subspecialist, doing the same things every day, seeing the same things. I knew I wanted to keep practicing general internal medicine, so I took a fellowship where I was working both inpatient and outpatient, and when I was looking for a job, I sought out things that involved some inpatient and some outpatient work. It turned out hospital medicine was the best fit.

What would you say is your favorite part of hospital medicine?

My favorite part of the job is getting to teach, working with medical students and residents. I also like the variety of what I do as a hospitalist, so I’m about 50% clinical and the rest of the time I perform a variety of tasks, both administrative and educational.

What about your least favorite part of hospitalist work?

Sometimes, particularly if you’re doing clinical, educational, and administrative work, it can be a little overwhelming to try and do a little bit of everything. I think generally that’s a good thing, but sometimes it can feel like a little too much.

What is some of the best advice you have received regarding how to handle the stresses of hospital medicine?

Feel free to say no to things. When hospitalists are starting their careers, and particularly when they are new to a job and trying to express their desire to get involved, sometimes they can have too much thrown at them at once. People can get overloaded very quickly, so I think feeling like you’re able to say no to some requests, or to take some time to think before you accept an additional role. The other piece of advice I remember from my fellowship, is that, when you do something, make it count twice. For example, if you’re involved in a project, you get the practical clinical or educational benefits of whatever the project was. But also think about how you might write about your experience for research purposes, such as for a poster, article, or other presentation.

What is the worst advice you have been given?

I think it’s not necessarily bad advice, but I guess it’s advice that I haven’t really followed. Since I work in academic medicine, I’ve found that the people in academics fall into one of two categories: There are the people who find their niche and remain on that path, and they’re very clear about it and don’t really stray from it; and there are people who don’t find that niche right away. I think the advice I received when starting out was to try to find that niche, and if you’re building an academic career it is very helpful to have these things in which you have become the expert. But I’ve just tried to go where the job takes me. I don’t necessarily have a single academic niche or something that I spend all my time doing, but I do have my hand in a lot of different things. To me, that’s a lot more interesting because it adds to the variety of what you’re doing. Every day is a little different.

What else do you do professionally outside of hospital medicine?

I actually practice a little outpatient medicine. When I first started here, I wanted to keep some outpatient experience, and so I actually created my own clinic. It’s a procedure clinic where I do paracentesis on people who have cirrhosis. Then on the educational side, I sit on the admission committees for the medical school here, so I get to look through the applicants and choose who we interview, and then once we interview candidates, I help choose how we rank students for admission.

Where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

I’ve never been one who looks at a particular job and says ‘Okay, I want to be the dean or have this position.’ I guess I just hope I’m better at the things I’m currently doing. I hope in 10 years that I’m a better teacher, that I’ll have learned more strategies to help more people, and that I have a better handle on the administrative side of the work. I hope I’ve progressed to a point in my career where I’m doing an even better job than I am now.

What are your goals as a member of the editorial board?

I have an interest not only in medicine but also in writing; I’ve gotten to do some writing both medical and nonmedical in the past. I’ve published a few articles in The Hospitalist, and hopefully, I can do more of that because writing is just another part of education.

Dr. Eric Howell joins SHM as chief operating officer

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

Replacing warfarin with a NOAC in patients on chronic anticoagulation therapy

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

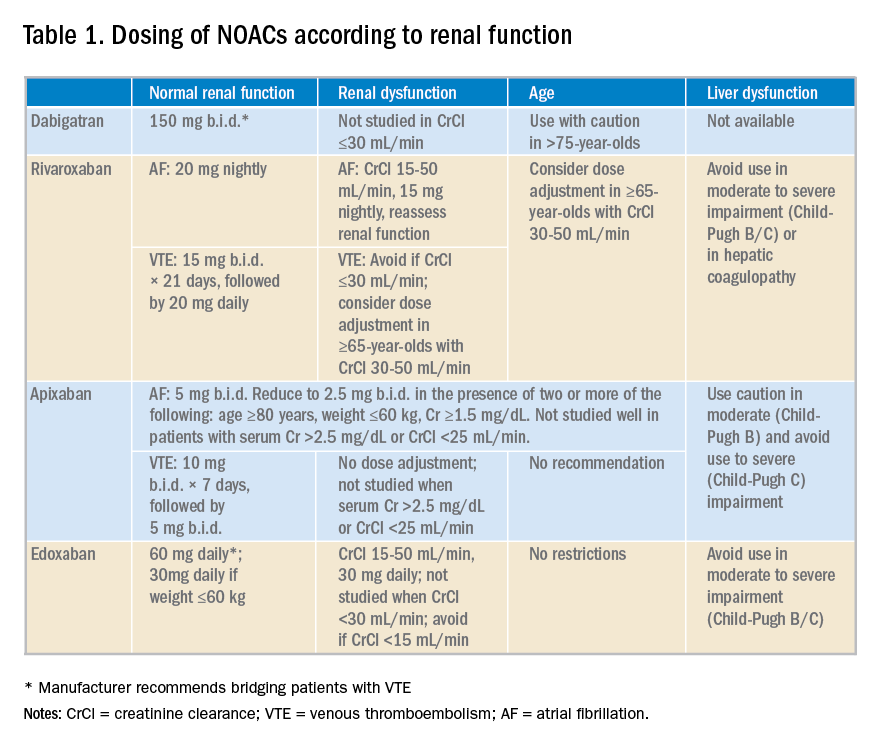

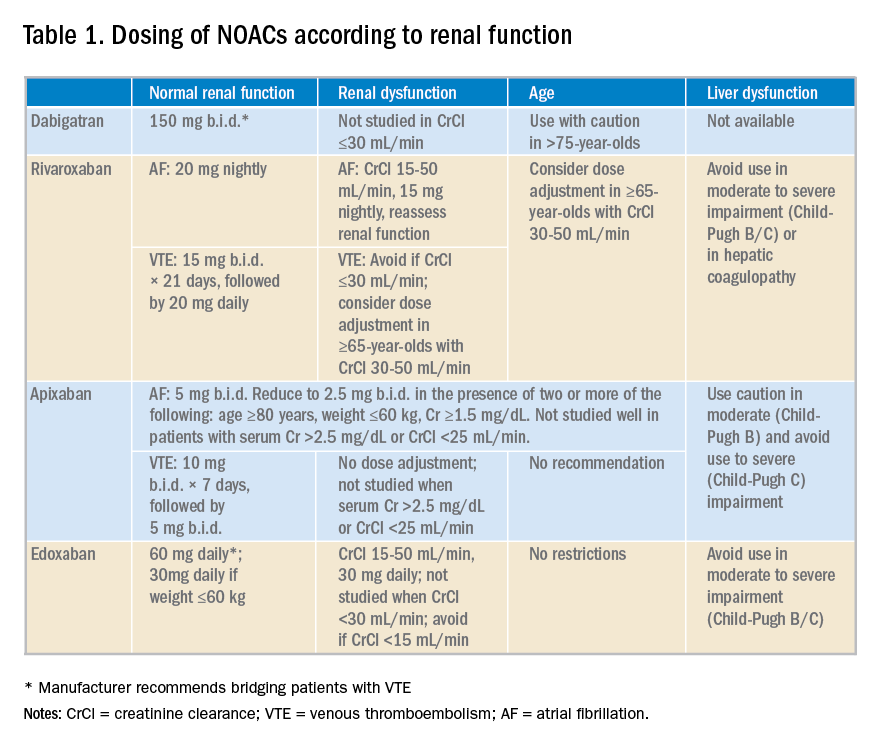

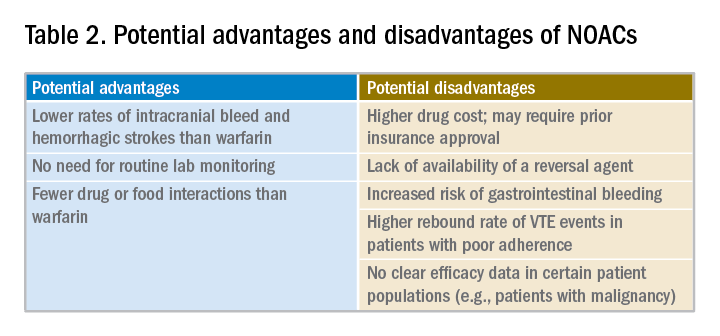

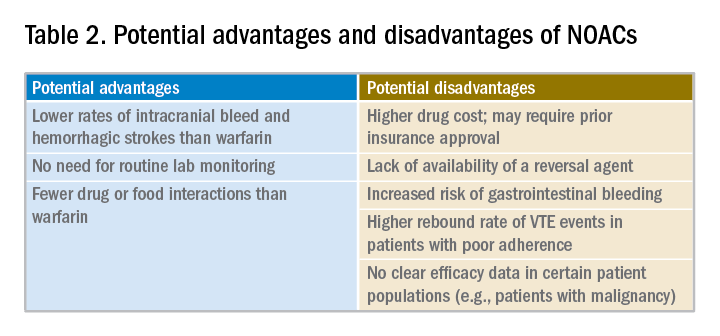

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

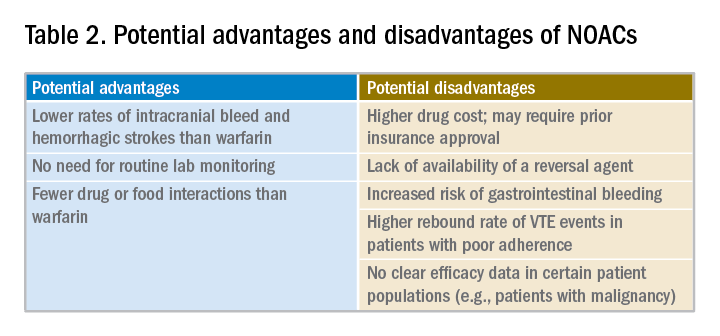

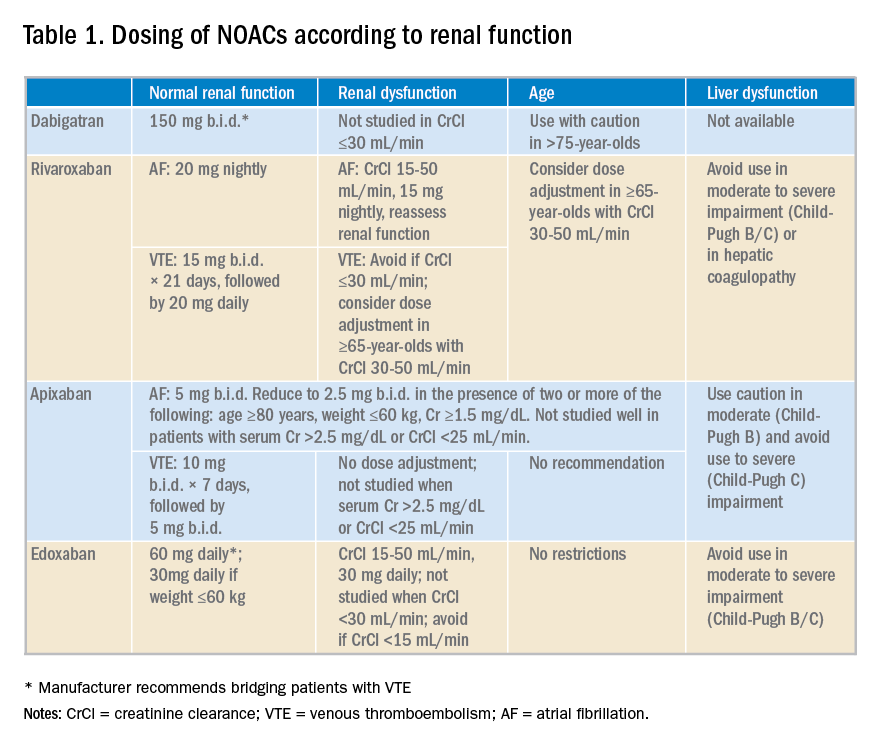

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

New Valsalva maneuver for SVT beats all others

NEW ORLEANS – , according to Jeet Mehta, MD, a resident in the combined medicine/pediatrics program at the University of Kansas, Wichita.

The 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommended vagal maneuvers as first-line treatment of supraventricular tachycardia, but added that there was no gold standard method. Since then, the situation has changed. Two well-conducted randomized clinical trials have been published that bring clarity as to the vagal maneuver of choice, Dr. Mehta reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

He and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of the three pre-2000 randomized controlled trials that compared the standard Valsalva maneuver to carotid sinus massage plus the two newer studies, both of which systematically compared a modified Valsalva maneuver with the standard version.

The clear winner in terms of efficacy was the modified Valsalva maneuver, in which patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) performed a standardized strain while in a semirecumbent position, then immediately laid flat and had their legs raised to 45 degrees for 15 seconds before returning to the semirecumbent position. The purpose of this postural modification is to boost relaxation phase venous return and vagal stimulation.

In the 433-patient multicenter REVERT trial in the United Kingdom, 43% of those assigned to the modified Valsalva maneuver returned to sinus rhythm 1 minute after completing the task, compared with 17% of those randomized to the standard semirecumbent Valsalva maneuver. This resulted in significantly less need for adenosine and other treatments. Although REVERT investigators had the patients blow into a manometer at 40 mm Hg for 15 seconds, they noted that the same intensity of strain can be achieved more practically by blowing into a 10-mL syringe sufficient to just move the plunger (Lancet. 2015 Oct 31;386[10005]:1747-53).

The REVERT findings were confirmed by a second trial conducted by Turkish investigators, in which the modified Valsalva maneuver was successful in 43% of patients, compared with 11% in the standard Valsalva maneuver group (Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;35[11]:1662-5).