User login

Lumbar spinal stenosis: Can positional therapy alleviate pain?

- Positional therapy with a wheeled walker may help patients with spinal stenosis to walk, as well as ease their pain. This conservative approach has minimum risks—and minimum costs.

Methods: We analyzed a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging and walking limitations treated with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion.

Results: Of the 52 patients, improvement in ambulation was classified as excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%). Among 48 patients with neurogenic pain, pain relief was classified as excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%).

Conclusions: These retrospective data from a case series support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion relieves lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. However, an adequate test of this hypothesis will require randomized trials of sufficient size and duration that include objective clinical endpoints such as quality-of-life measures, immobility complications and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures including epidural injections, and spinal surgery.

In the meantime, this conservative strategy is an option for patients following the recommendations of the North American Spine Society, or for those who have contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections, or who have found these options ineffective. Positional therapy with a wheeled walker offers the possibility of short-term benefits for ambulation and pain, with minimal risks and costs.

When shoppers at the grocery store are leaning forward on their carts, many of them could be trying to relieve the pain of lumbar spinal stenosis. This way of finding temporary relief is one we replicated with a wheeled walker for prolonged periods in a retrospective case series to see what further benefits might be gained.

Symptoms are affected by body position and activity level. For patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, lower extremity symptoms can be debilitating and include loss of sensation, paresthesias, burning, pain, weakness, claudication, difficulty standing or walking, or nocturnal neuropathic pain in the feet, legs, or thighs. Axial loading1 (as occurs during walking) and spinal extension2 (as occurs in an erect position) both decrease the diameter of the central spinal canal and lateral recesses, and may cause nerve compression and lower extremity symptoms. In contrast, lumbosacral flexion—facilitated, for example, by leaning forward on a grocery cart3—opens the spine and may reduce nerve compression and related symptoms.

Exhaust all medical options before turning to surgery. The North American Spine Society (NASS) has issued clinical guidelines for spinal stenosis that make recommendations regarding the value of pharmacologic interventions, manipulative techniques, behavioral therapies, and other conservative measures (www. guideline.gov).4 For patients with severe or unremitting symptoms requiring specialized care by spine specialists, NASS further outlines 3 phases of gradually intensifying medical therapy before turning to surgery, which is associated with increased morbidity and costs.5

A previously untested medical approach. Most patients may return to productivity within 2 to 4 months after starting conservative treatment, but some will still require treatment recommended for greater levels of severity.6 For these latter patients, no randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of medical management with a wheeled walker. This new intervention, if effective, could avoid or delay the expense and side effects of surgery.7 In addition, a wheeled walker may decrease pain from spinal stenosis.8

To explore whether positional therapy with a wheeled walker relieves lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, we conducted a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal imaging confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations.9

Methods

These observations were based on retrospective chart reviews of all patients in a podiatric private practice (SMG) over 1 year to identify those with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis who were evaluated with positional testing.

Identifying possible stenosis by positional history

Patients were suspected of having spinal stenosis contributing to, or entirely responsible for, lower extremity neuropathic or claudication symptoms based on a positive positional history, including any of the following patterns:

- walking limitation in which the patient needed to sit or lean forward to get relief

- significant improvement in ambulation when pushing a grocery cart, walker, or baby stroller, or when on a treadmill that induced lumbosacral flexion

- constant, frequent, or occasional lower extremity symptoms of a neuropathic nature with an unclear cause that was exacerbated by walking or standing

- nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms affected by sleep position.

Symptoms linked to the cause radiologically. Spinal stenosis was confirmed by spinal imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan) showing stenosis in areas corresponding to symptoms in the lower extremities. Patients without confirmatory spinal imaging were excluded from our study.

Peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed by changes in nerve conduction studies interpreted as being consistent with axonal or demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Using these criteria, we assembled a case series of 52 patients with imaging-confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations. Of the 52 patients, 33 had received a previous diagnosis of spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging, but only 10 considered that to be the cause of their lower extremity symptoms, with the remainder presenting with a primary diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy—with or without arterial claudication.

Using positional testing to confirm suitability of rollator walker

Patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis underwent a therapeutic trial of “positional testing” involving full-time use of a 3- or 4-wheeled rollator walker (usually provided as a loan) set to induce lumbosacral flexion for 3 days. For patients no taller than 4’ 9” to 5’ 2”, a reduced-height walker (29” to 32”) was usually necessary; patients shorter than 4’ 9” usually needed a modified pediatric walker.

Patients returned for adjustment of the walker if it was uncomfortable or unhelpful. We recommended they also use a shower stool and kitchen stool to minimize erect posture. If they experienced nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms, we encouraged them to try sleeping in a recliner. If patients with neuropathic symptoms wanted to continue sleeping in bed, we encouraged them to try sleeping with a pillow beneath their thighs (if sleeping on their back), or sleeping in a fetal position with a pillow between their thighs (if sleeping on their side).10

We usually reevaluated patients in 3 to 5 days, comparing current pain severity and walking capability with previous levels. Patients reporting improvement were encouraged to maintain this full-time positional testing for a total of 10 days. During the subsequent “positional therapy” phase, they gradually reduced their use of the walker, if possible, to an amount just needed to maintain improvement. The therapy phase lasted for 3 months, bringing the total time that patients used a walker to nearly 14 weeks.

Criteria for successful treatment

We gauged treatment success according to self-reported walking capabilities and subjective descriptions of uncomfortable symptoms, using criteria previously described.10

Walking distance. Patients reported uninterrupted walking distance before using the walker and after they had begun using the walker. We classified improvement in walking distance as excellent (over 400% increase), good (250%– 399%), moderate (100%–249%), or poor (≤99%). (The distance a patient can walk—before pain sets in—may vary from day to day. We therefore gauged improvement in this distance by contrasting consistent walking distances achieved and maintained with positional management to the shortest usual walking distance before the intervention.)

Pain reduction. To define a decrease in discomfort reported during the positional testing phase and maintained with positional therapy, we used a verbal analog pain scale (1–3 out of 10=mild pain; 4–7=moderate pain; 8–10=severe pain). We classified reduction in discomfort stemming from spinal stenosis as excellent (75%–100%), good (50%–74%), moderate (25%–49%), or poor (≤24%).

Results

Rapid and dramatic improvement for most patients

The 52 patients in our case series ranged in age from 67 to 90 years; 19 were men. Of the 52, improvement in ambulation was excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of 48 patients with neurogenic pain, grading with the verbal analog pain scale showed relief was excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of the 37 patients with excellent or good improvement in ambulation, 11 needed to keep using the walker extensively, 22 frequently, and 4 occasionally or not at all. Of the 6 patients who had undergone spinal stenosis surgery, improvement was excellent for 3, good for 1, and poor for 2.

A subgroup of 36 patients in our study had diabetes. Of these, 25 had concomitant peripheral neuropathy; 18 reported good to excellent improvement of ambulation or reduction of pain.

Conclusion

Patients deserve a trial of positional therapy with the wheeled walker

These descriptive data support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion alleviates lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. Limitations of this case series:

- the lack of any comparison group

- improvements in ambulation are based on subjective criteria

- findings can be generalized only to older patients potentially eligible for surgery,11 those who have not benefited from surgery, or those who are undergoing medical therapies recommended by the North American Spine Society4

- patients seen in a podiatry office who present for lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis may differ from those seen in a family practitioner’s office who present with low back pain.

Nonetheless, this conservative strategy may be applicable to the evaluation and management of lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis regardless of presenting symptoms or source of medical care.

Walking limitations and lower extremity pain caused by spinal stenosis are physically and psychologically disabling. Relief can dramatically improve a person’s quality of life. Improved ambulation may also aid in the management of concurrent medical conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Our hypothesis requires direct testing in randomized trials of sufficient size and duration. Such trials should include longer term and more objective clinical endpoints, such as quality of life measures, complications due to immobility and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures such as epidural injections, or spinal surgery. Validation of this hypothesis would substantially reduce morbidity and costs, as well as increase the quality of life of patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis. Until such studies are conducted, this conservative strategy may increase ambulation and decrease pain over the short term, with minimal risks and costs. It may also be helpful for those with contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections or those who have found these approaches ineffective.

Correspondence

Charles H. Hennekens, MD, Sir Richard Doll Research Professor, College of Biomedical Science, Department of Clinical Science and Medical Education and Center of Excellence, Florida Atlantic University, Building 10–Administration, Division of Research, Room 244D, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton, FL 33432; [email protected]

1. Willen J, Danielson B, Gaulitz A, Niklason T, Schönström N, Hansson T. Dynamic effect on the lumbar spinal canal: axial loaded CT-myelography and MRI in patients with sciatica and/or neurogenic claudication. Spine. 1997;22:2968-2976.

2. Harrison DE, Calliet R, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison SO. A review of biomechanics of the central nervous system–part 1: spinal canal deformations resulting from changes in posture. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:227-234.

3. Goldsmith ME, Wiesel S. Spinal stenosis: a straightforward approach to a complex problem. J Clin Rheumatol. 1998;4:92.-

4. Diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. National Guideline Clearinghouse Web site. Available at: www.guidelines.gov. Accessed March 6, 2008.

5. Wong DA, Mayer TG, Spivak JM, et al. North American Spine Society (NASS). Phase III clinical guide-lines for multidisciplinary spine care specialists. Spinal stenosis version 1.0. LaGrange, IL: North American Spine Society; 2002.

6. Snyder DL, Doggett D, Turkelson C. Treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:517-520.

7. Malmivaara A, Slätis P, Heliövaara M, et al. Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group. Surgical or non-operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:1-8.

8. Hoenig H. Assistive technology and mobility aids for the older patient with disability. Ann Long Term Care. 2004;12:12-19.

9. Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1987.

10. Goldman SM. Neuropathic pain at night in diabetic patients may be caused by spinal stenosis. Diabetic Med. 2005;22:1763-1765.

11. Tong HC, Haig AJ, Geisser ME. Comparing pain severity and functional status of older adults without spinal symptoms, with lumbar spinal stenosis, and with axial low back pain. Gerontology. 2007;53:111-115.

- Positional therapy with a wheeled walker may help patients with spinal stenosis to walk, as well as ease their pain. This conservative approach has minimum risks—and minimum costs.

Methods: We analyzed a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging and walking limitations treated with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion.

Results: Of the 52 patients, improvement in ambulation was classified as excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%). Among 48 patients with neurogenic pain, pain relief was classified as excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%).

Conclusions: These retrospective data from a case series support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion relieves lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. However, an adequate test of this hypothesis will require randomized trials of sufficient size and duration that include objective clinical endpoints such as quality-of-life measures, immobility complications and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures including epidural injections, and spinal surgery.

In the meantime, this conservative strategy is an option for patients following the recommendations of the North American Spine Society, or for those who have contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections, or who have found these options ineffective. Positional therapy with a wheeled walker offers the possibility of short-term benefits for ambulation and pain, with minimal risks and costs.

When shoppers at the grocery store are leaning forward on their carts, many of them could be trying to relieve the pain of lumbar spinal stenosis. This way of finding temporary relief is one we replicated with a wheeled walker for prolonged periods in a retrospective case series to see what further benefits might be gained.

Symptoms are affected by body position and activity level. For patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, lower extremity symptoms can be debilitating and include loss of sensation, paresthesias, burning, pain, weakness, claudication, difficulty standing or walking, or nocturnal neuropathic pain in the feet, legs, or thighs. Axial loading1 (as occurs during walking) and spinal extension2 (as occurs in an erect position) both decrease the diameter of the central spinal canal and lateral recesses, and may cause nerve compression and lower extremity symptoms. In contrast, lumbosacral flexion—facilitated, for example, by leaning forward on a grocery cart3—opens the spine and may reduce nerve compression and related symptoms.

Exhaust all medical options before turning to surgery. The North American Spine Society (NASS) has issued clinical guidelines for spinal stenosis that make recommendations regarding the value of pharmacologic interventions, manipulative techniques, behavioral therapies, and other conservative measures (www. guideline.gov).4 For patients with severe or unremitting symptoms requiring specialized care by spine specialists, NASS further outlines 3 phases of gradually intensifying medical therapy before turning to surgery, which is associated with increased morbidity and costs.5

A previously untested medical approach. Most patients may return to productivity within 2 to 4 months after starting conservative treatment, but some will still require treatment recommended for greater levels of severity.6 For these latter patients, no randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of medical management with a wheeled walker. This new intervention, if effective, could avoid or delay the expense and side effects of surgery.7 In addition, a wheeled walker may decrease pain from spinal stenosis.8

To explore whether positional therapy with a wheeled walker relieves lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, we conducted a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal imaging confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations.9

Methods

These observations were based on retrospective chart reviews of all patients in a podiatric private practice (SMG) over 1 year to identify those with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis who were evaluated with positional testing.

Identifying possible stenosis by positional history

Patients were suspected of having spinal stenosis contributing to, or entirely responsible for, lower extremity neuropathic or claudication symptoms based on a positive positional history, including any of the following patterns:

- walking limitation in which the patient needed to sit or lean forward to get relief

- significant improvement in ambulation when pushing a grocery cart, walker, or baby stroller, or when on a treadmill that induced lumbosacral flexion

- constant, frequent, or occasional lower extremity symptoms of a neuropathic nature with an unclear cause that was exacerbated by walking or standing

- nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms affected by sleep position.

Symptoms linked to the cause radiologically. Spinal stenosis was confirmed by spinal imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan) showing stenosis in areas corresponding to symptoms in the lower extremities. Patients without confirmatory spinal imaging were excluded from our study.

Peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed by changes in nerve conduction studies interpreted as being consistent with axonal or demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Using these criteria, we assembled a case series of 52 patients with imaging-confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations. Of the 52 patients, 33 had received a previous diagnosis of spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging, but only 10 considered that to be the cause of their lower extremity symptoms, with the remainder presenting with a primary diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy—with or without arterial claudication.

Using positional testing to confirm suitability of rollator walker

Patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis underwent a therapeutic trial of “positional testing” involving full-time use of a 3- or 4-wheeled rollator walker (usually provided as a loan) set to induce lumbosacral flexion for 3 days. For patients no taller than 4’ 9” to 5’ 2”, a reduced-height walker (29” to 32”) was usually necessary; patients shorter than 4’ 9” usually needed a modified pediatric walker.

Patients returned for adjustment of the walker if it was uncomfortable or unhelpful. We recommended they also use a shower stool and kitchen stool to minimize erect posture. If they experienced nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms, we encouraged them to try sleeping in a recliner. If patients with neuropathic symptoms wanted to continue sleeping in bed, we encouraged them to try sleeping with a pillow beneath their thighs (if sleeping on their back), or sleeping in a fetal position with a pillow between their thighs (if sleeping on their side).10

We usually reevaluated patients in 3 to 5 days, comparing current pain severity and walking capability with previous levels. Patients reporting improvement were encouraged to maintain this full-time positional testing for a total of 10 days. During the subsequent “positional therapy” phase, they gradually reduced their use of the walker, if possible, to an amount just needed to maintain improvement. The therapy phase lasted for 3 months, bringing the total time that patients used a walker to nearly 14 weeks.

Criteria for successful treatment

We gauged treatment success according to self-reported walking capabilities and subjective descriptions of uncomfortable symptoms, using criteria previously described.10

Walking distance. Patients reported uninterrupted walking distance before using the walker and after they had begun using the walker. We classified improvement in walking distance as excellent (over 400% increase), good (250%– 399%), moderate (100%–249%), or poor (≤99%). (The distance a patient can walk—before pain sets in—may vary from day to day. We therefore gauged improvement in this distance by contrasting consistent walking distances achieved and maintained with positional management to the shortest usual walking distance before the intervention.)

Pain reduction. To define a decrease in discomfort reported during the positional testing phase and maintained with positional therapy, we used a verbal analog pain scale (1–3 out of 10=mild pain; 4–7=moderate pain; 8–10=severe pain). We classified reduction in discomfort stemming from spinal stenosis as excellent (75%–100%), good (50%–74%), moderate (25%–49%), or poor (≤24%).

Results

Rapid and dramatic improvement for most patients

The 52 patients in our case series ranged in age from 67 to 90 years; 19 were men. Of the 52, improvement in ambulation was excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of 48 patients with neurogenic pain, grading with the verbal analog pain scale showed relief was excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of the 37 patients with excellent or good improvement in ambulation, 11 needed to keep using the walker extensively, 22 frequently, and 4 occasionally or not at all. Of the 6 patients who had undergone spinal stenosis surgery, improvement was excellent for 3, good for 1, and poor for 2.

A subgroup of 36 patients in our study had diabetes. Of these, 25 had concomitant peripheral neuropathy; 18 reported good to excellent improvement of ambulation or reduction of pain.

Conclusion

Patients deserve a trial of positional therapy with the wheeled walker

These descriptive data support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion alleviates lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. Limitations of this case series:

- the lack of any comparison group

- improvements in ambulation are based on subjective criteria

- findings can be generalized only to older patients potentially eligible for surgery,11 those who have not benefited from surgery, or those who are undergoing medical therapies recommended by the North American Spine Society4

- patients seen in a podiatry office who present for lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis may differ from those seen in a family practitioner’s office who present with low back pain.

Nonetheless, this conservative strategy may be applicable to the evaluation and management of lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis regardless of presenting symptoms or source of medical care.

Walking limitations and lower extremity pain caused by spinal stenosis are physically and psychologically disabling. Relief can dramatically improve a person’s quality of life. Improved ambulation may also aid in the management of concurrent medical conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Our hypothesis requires direct testing in randomized trials of sufficient size and duration. Such trials should include longer term and more objective clinical endpoints, such as quality of life measures, complications due to immobility and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures such as epidural injections, or spinal surgery. Validation of this hypothesis would substantially reduce morbidity and costs, as well as increase the quality of life of patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis. Until such studies are conducted, this conservative strategy may increase ambulation and decrease pain over the short term, with minimal risks and costs. It may also be helpful for those with contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections or those who have found these approaches ineffective.

Correspondence

Charles H. Hennekens, MD, Sir Richard Doll Research Professor, College of Biomedical Science, Department of Clinical Science and Medical Education and Center of Excellence, Florida Atlantic University, Building 10–Administration, Division of Research, Room 244D, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton, FL 33432; [email protected]

- Positional therapy with a wheeled walker may help patients with spinal stenosis to walk, as well as ease their pain. This conservative approach has minimum risks—and minimum costs.

Methods: We analyzed a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging and walking limitations treated with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion.

Results: Of the 52 patients, improvement in ambulation was classified as excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%). Among 48 patients with neurogenic pain, pain relief was classified as excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%).

Conclusions: These retrospective data from a case series support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion relieves lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. However, an adequate test of this hypothesis will require randomized trials of sufficient size and duration that include objective clinical endpoints such as quality-of-life measures, immobility complications and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures including epidural injections, and spinal surgery.

In the meantime, this conservative strategy is an option for patients following the recommendations of the North American Spine Society, or for those who have contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections, or who have found these options ineffective. Positional therapy with a wheeled walker offers the possibility of short-term benefits for ambulation and pain, with minimal risks and costs.

When shoppers at the grocery store are leaning forward on their carts, many of them could be trying to relieve the pain of lumbar spinal stenosis. This way of finding temporary relief is one we replicated with a wheeled walker for prolonged periods in a retrospective case series to see what further benefits might be gained.

Symptoms are affected by body position and activity level. For patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, lower extremity symptoms can be debilitating and include loss of sensation, paresthesias, burning, pain, weakness, claudication, difficulty standing or walking, or nocturnal neuropathic pain in the feet, legs, or thighs. Axial loading1 (as occurs during walking) and spinal extension2 (as occurs in an erect position) both decrease the diameter of the central spinal canal and lateral recesses, and may cause nerve compression and lower extremity symptoms. In contrast, lumbosacral flexion—facilitated, for example, by leaning forward on a grocery cart3—opens the spine and may reduce nerve compression and related symptoms.

Exhaust all medical options before turning to surgery. The North American Spine Society (NASS) has issued clinical guidelines for spinal stenosis that make recommendations regarding the value of pharmacologic interventions, manipulative techniques, behavioral therapies, and other conservative measures (www. guideline.gov).4 For patients with severe or unremitting symptoms requiring specialized care by spine specialists, NASS further outlines 3 phases of gradually intensifying medical therapy before turning to surgery, which is associated with increased morbidity and costs.5

A previously untested medical approach. Most patients may return to productivity within 2 to 4 months after starting conservative treatment, but some will still require treatment recommended for greater levels of severity.6 For these latter patients, no randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of medical management with a wheeled walker. This new intervention, if effective, could avoid or delay the expense and side effects of surgery.7 In addition, a wheeled walker may decrease pain from spinal stenosis.8

To explore whether positional therapy with a wheeled walker relieves lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, we conducted a retrospective case series of 52 patients with spinal imaging confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations.9

Methods

These observations were based on retrospective chart reviews of all patients in a podiatric private practice (SMG) over 1 year to identify those with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis who were evaluated with positional testing.

Identifying possible stenosis by positional history

Patients were suspected of having spinal stenosis contributing to, or entirely responsible for, lower extremity neuropathic or claudication symptoms based on a positive positional history, including any of the following patterns:

- walking limitation in which the patient needed to sit or lean forward to get relief

- significant improvement in ambulation when pushing a grocery cart, walker, or baby stroller, or when on a treadmill that induced lumbosacral flexion

- constant, frequent, or occasional lower extremity symptoms of a neuropathic nature with an unclear cause that was exacerbated by walking or standing

- nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms affected by sleep position.

Symptoms linked to the cause radiologically. Spinal stenosis was confirmed by spinal imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan) showing stenosis in areas corresponding to symptoms in the lower extremities. Patients without confirmatory spinal imaging were excluded from our study.

Peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed by changes in nerve conduction studies interpreted as being consistent with axonal or demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Using these criteria, we assembled a case series of 52 patients with imaging-confirmed lumbar spinal stenosis and walking limitations. Of the 52 patients, 33 had received a previous diagnosis of spinal stenosis confirmed by spinal imaging, but only 10 considered that to be the cause of their lower extremity symptoms, with the remainder presenting with a primary diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy—with or without arterial claudication.

Using positional testing to confirm suitability of rollator walker

Patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis underwent a therapeutic trial of “positional testing” involving full-time use of a 3- or 4-wheeled rollator walker (usually provided as a loan) set to induce lumbosacral flexion for 3 days. For patients no taller than 4’ 9” to 5’ 2”, a reduced-height walker (29” to 32”) was usually necessary; patients shorter than 4’ 9” usually needed a modified pediatric walker.

Patients returned for adjustment of the walker if it was uncomfortable or unhelpful. We recommended they also use a shower stool and kitchen stool to minimize erect posture. If they experienced nocturnal exacerbation of neuropathic symptoms, we encouraged them to try sleeping in a recliner. If patients with neuropathic symptoms wanted to continue sleeping in bed, we encouraged them to try sleeping with a pillow beneath their thighs (if sleeping on their back), or sleeping in a fetal position with a pillow between their thighs (if sleeping on their side).10

We usually reevaluated patients in 3 to 5 days, comparing current pain severity and walking capability with previous levels. Patients reporting improvement were encouraged to maintain this full-time positional testing for a total of 10 days. During the subsequent “positional therapy” phase, they gradually reduced their use of the walker, if possible, to an amount just needed to maintain improvement. The therapy phase lasted for 3 months, bringing the total time that patients used a walker to nearly 14 weeks.

Criteria for successful treatment

We gauged treatment success according to self-reported walking capabilities and subjective descriptions of uncomfortable symptoms, using criteria previously described.10

Walking distance. Patients reported uninterrupted walking distance before using the walker and after they had begun using the walker. We classified improvement in walking distance as excellent (over 400% increase), good (250%– 399%), moderate (100%–249%), or poor (≤99%). (The distance a patient can walk—before pain sets in—may vary from day to day. We therefore gauged improvement in this distance by contrasting consistent walking distances achieved and maintained with positional management to the shortest usual walking distance before the intervention.)

Pain reduction. To define a decrease in discomfort reported during the positional testing phase and maintained with positional therapy, we used a verbal analog pain scale (1–3 out of 10=mild pain; 4–7=moderate pain; 8–10=severe pain). We classified reduction in discomfort stemming from spinal stenosis as excellent (75%–100%), good (50%–74%), moderate (25%–49%), or poor (≤24%).

Results

Rapid and dramatic improvement for most patients

The 52 patients in our case series ranged in age from 67 to 90 years; 19 were men. Of the 52, improvement in ambulation was excellent for 30 (58%), good for 7 (13%), moderate for 8 (16%), and poor for 7 (13%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of 48 patients with neurogenic pain, grading with the verbal analog pain scale showed relief was excellent for 22 (46%), good for 11 (23%), moderate for 7 (14.5%), and poor for 8 (16.5%) after 3 to 5 days.

Of the 37 patients with excellent or good improvement in ambulation, 11 needed to keep using the walker extensively, 22 frequently, and 4 occasionally or not at all. Of the 6 patients who had undergone spinal stenosis surgery, improvement was excellent for 3, good for 1, and poor for 2.

A subgroup of 36 patients in our study had diabetes. Of these, 25 had concomitant peripheral neuropathy; 18 reported good to excellent improvement of ambulation or reduction of pain.

Conclusion

Patients deserve a trial of positional therapy with the wheeled walker

These descriptive data support the hypothesis that positional therapy with a wheeled walker set to induce lumbosacral flexion alleviates lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis. Limitations of this case series:

- the lack of any comparison group

- improvements in ambulation are based on subjective criteria

- findings can be generalized only to older patients potentially eligible for surgery,11 those who have not benefited from surgery, or those who are undergoing medical therapies recommended by the North American Spine Society4

- patients seen in a podiatry office who present for lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis may differ from those seen in a family practitioner’s office who present with low back pain.

Nonetheless, this conservative strategy may be applicable to the evaluation and management of lower extremity symptoms of spinal stenosis regardless of presenting symptoms or source of medical care.

Walking limitations and lower extremity pain caused by spinal stenosis are physically and psychologically disabling. Relief can dramatically improve a person’s quality of life. Improved ambulation may also aid in the management of concurrent medical conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Our hypothesis requires direct testing in randomized trials of sufficient size and duration. Such trials should include longer term and more objective clinical endpoints, such as quality of life measures, complications due to immobility and need for drugs, physical therapy, procedures such as epidural injections, or spinal surgery. Validation of this hypothesis would substantially reduce morbidity and costs, as well as increase the quality of life of patients with lower extremity symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis. Until such studies are conducted, this conservative strategy may increase ambulation and decrease pain over the short term, with minimal risks and costs. It may also be helpful for those with contraindications (or aversions) to surgery or epidural injections or those who have found these approaches ineffective.

Correspondence

Charles H. Hennekens, MD, Sir Richard Doll Research Professor, College of Biomedical Science, Department of Clinical Science and Medical Education and Center of Excellence, Florida Atlantic University, Building 10–Administration, Division of Research, Room 244D, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton, FL 33432; [email protected]

1. Willen J, Danielson B, Gaulitz A, Niklason T, Schönström N, Hansson T. Dynamic effect on the lumbar spinal canal: axial loaded CT-myelography and MRI in patients with sciatica and/or neurogenic claudication. Spine. 1997;22:2968-2976.

2. Harrison DE, Calliet R, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison SO. A review of biomechanics of the central nervous system–part 1: spinal canal deformations resulting from changes in posture. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:227-234.

3. Goldsmith ME, Wiesel S. Spinal stenosis: a straightforward approach to a complex problem. J Clin Rheumatol. 1998;4:92.-

4. Diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. National Guideline Clearinghouse Web site. Available at: www.guidelines.gov. Accessed March 6, 2008.

5. Wong DA, Mayer TG, Spivak JM, et al. North American Spine Society (NASS). Phase III clinical guide-lines for multidisciplinary spine care specialists. Spinal stenosis version 1.0. LaGrange, IL: North American Spine Society; 2002.

6. Snyder DL, Doggett D, Turkelson C. Treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:517-520.

7. Malmivaara A, Slätis P, Heliövaara M, et al. Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group. Surgical or non-operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:1-8.

8. Hoenig H. Assistive technology and mobility aids for the older patient with disability. Ann Long Term Care. 2004;12:12-19.

9. Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1987.

10. Goldman SM. Neuropathic pain at night in diabetic patients may be caused by spinal stenosis. Diabetic Med. 2005;22:1763-1765.

11. Tong HC, Haig AJ, Geisser ME. Comparing pain severity and functional status of older adults without spinal symptoms, with lumbar spinal stenosis, and with axial low back pain. Gerontology. 2007;53:111-115.

1. Willen J, Danielson B, Gaulitz A, Niklason T, Schönström N, Hansson T. Dynamic effect on the lumbar spinal canal: axial loaded CT-myelography and MRI in patients with sciatica and/or neurogenic claudication. Spine. 1997;22:2968-2976.

2. Harrison DE, Calliet R, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison SO. A review of biomechanics of the central nervous system–part 1: spinal canal deformations resulting from changes in posture. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:227-234.

3. Goldsmith ME, Wiesel S. Spinal stenosis: a straightforward approach to a complex problem. J Clin Rheumatol. 1998;4:92.-

4. Diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. National Guideline Clearinghouse Web site. Available at: www.guidelines.gov. Accessed March 6, 2008.

5. Wong DA, Mayer TG, Spivak JM, et al. North American Spine Society (NASS). Phase III clinical guide-lines for multidisciplinary spine care specialists. Spinal stenosis version 1.0. LaGrange, IL: North American Spine Society; 2002.

6. Snyder DL, Doggett D, Turkelson C. Treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:517-520.

7. Malmivaara A, Slätis P, Heliövaara M, et al. Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group. Surgical or non-operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:1-8.

8. Hoenig H. Assistive technology and mobility aids for the older patient with disability. Ann Long Term Care. 2004;12:12-19.

9. Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1987.

10. Goldman SM. Neuropathic pain at night in diabetic patients may be caused by spinal stenosis. Diabetic Med. 2005;22:1763-1765.

11. Tong HC, Haig AJ, Geisser ME. Comparing pain severity and functional status of older adults without spinal symptoms, with lumbar spinal stenosis, and with axial low back pain. Gerontology. 2007;53:111-115.

MEASLES HITS HOME: Sobering lessons from 2 travel-related outbreaks

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

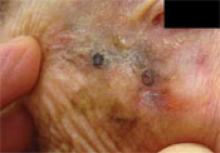

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians

Include measles in the differential diagnosis of patients who have fever and rash, especially if they have traveled to another country within the past 3 to 4 weeks. Any patient who meets the definition of measles (fever 101ºF or higher; rash; and at least 1 of the 3 Cs—cough, coryza, conjunctivitis) should be immediately reported to the local health department. The health department will provide instructions for collecting laboratory samples for confirmation; instructions on patient isolation; and assistance with notification and disease control measures for exposed individuals.

Immunize patients and staff. These recurring cases of imported measles underscore the importance of maintaining a high level of immunity. Outbreaks can happen even where immunity is 90% to 95%. When vaccination rates dip below 90%, sustained outbreaks can occur.6

Ensure that staff and patients are all immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases, and inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated place their children at risk and contribute to higher community risk. Communities that have higher rates of non-adherence to vaccine recommendations are more likely to have outbreaks.7,8

Use strict infection control in the office. The recent outbreak in California where 4 children were infected in their physician’s office reinforces the need for strict infection-control practices. Do not allow patients with rash and fever to remain in a common waiting area. Move them to an examination room, preferably an airborne infection isolation room. Keep the door to the examination room closed, and be sure that all health care personnel who come in contact with such patients are immune. Do not use triage rooms for 2 hours after the patient suspected of having measles leaves. Do not send these patients to other health care facilities, such as laboratories, unless infection control measures can be adhered to at those locations. Guidelines on infection control practices in health care settings are available.9,10

Quick response

Quick control of these outbreaks shows the value of the public health infrastructure. Disease surveillance and outbreak response is vital to the public health system, and its value is frequently under-appreciated by physicians and the public.

Fewer than 100 cases of measles occur in the United States each year, and virtually all are linked to imported cases.3 Before vaccine was introduced in 1963, 3 to 4 million cases per year occurred, and caused, on average, 450 deaths, 1000 chronic disabilities, and 28,000 hospitalizations.1 Success in controlling measles is due largely to high levels of coverage with 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine and public health surveillance and disease control.

Measles virus is highly infectious and is spread by airborne droplets and direct contact with nose and throat secretions. The incubation is 7 to 18 days.

Measles begins with fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and whitish spots on the buccal mucosa (Koplick spots).4 Rash appears on the 3rd to 7th day and lasts 4 to 7 days. It begins on the face but soon becomes generalized. An infected person is contagious from 5 days before the rash until 4 days after the rash appears. The diagnosis of measles can be confirrmed by serum measles IGM, which occurs within 3 days of rash, or a rise in measles IGG between acute and 2-week convalescent serum titers.

Complications: pneumonia (5%), otitis media (10%), and encephalitis 1/1000). Death rates: 1 to 2/1000, varying greatly based on age and nutrition; more severe in the very young and the malnourished. Worldwide, about 500,000 children die from measles each year.5

Immunity is defined as:

- 2 vaccine doses at least 1 month apart, both given after the 1st birthday,

- born before 1957,

- serological evidence, or

- history of physician-diagnosed measles.

1. CDC. Outbreak of measles—San Diego, California, January-February 2008. MMWR. 2008;57:Early Release February 22, 2008.-

2. CDC. Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August-September 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:169-173.

3. CDC. Measles—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55:1348-1351.

4. Measles. In: Heyman DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

5. CDC. Parents’ guide to childhood immunizations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/measles/downloads/pg_why_vacc_measles.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2008.

6. Richard JL, Masserey-Spicher V, Santibanez S, Mankertz A. Measles outbreak in Switzerland. Available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/edition/v13n08/080221_1.asp. Accessed March 17. 2008.

7. Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws; individual and societal risk of measles. JAMA. 1999;282:47-53

8. Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, et al. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA. 2008;284:3145-3150.

9. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory committee, 2007.Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(suppl 2):S65-164.

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Infection control in outpatient settings. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:485-488.

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians

Include measles in the differential diagnosis of patients who have fever and rash, especially if they have traveled to another country within the past 3 to 4 weeks. Any patient who meets the definition of measles (fever 101ºF or higher; rash; and at least 1 of the 3 Cs—cough, coryza, conjunctivitis) should be immediately reported to the local health department. The health department will provide instructions for collecting laboratory samples for confirmation; instructions on patient isolation; and assistance with notification and disease control measures for exposed individuals.

Immunize patients and staff. These recurring cases of imported measles underscore the importance of maintaining a high level of immunity. Outbreaks can happen even where immunity is 90% to 95%. When vaccination rates dip below 90%, sustained outbreaks can occur.6

Ensure that staff and patients are all immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases, and inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated place their children at risk and contribute to higher community risk. Communities that have higher rates of non-adherence to vaccine recommendations are more likely to have outbreaks.7,8

Use strict infection control in the office. The recent outbreak in California where 4 children were infected in their physician’s office reinforces the need for strict infection-control practices. Do not allow patients with rash and fever to remain in a common waiting area. Move them to an examination room, preferably an airborne infection isolation room. Keep the door to the examination room closed, and be sure that all health care personnel who come in contact with such patients are immune. Do not use triage rooms for 2 hours after the patient suspected of having measles leaves. Do not send these patients to other health care facilities, such as laboratories, unless infection control measures can be adhered to at those locations. Guidelines on infection control practices in health care settings are available.9,10

Quick response

Quick control of these outbreaks shows the value of the public health infrastructure. Disease surveillance and outbreak response is vital to the public health system, and its value is frequently under-appreciated by physicians and the public.

Fewer than 100 cases of measles occur in the United States each year, and virtually all are linked to imported cases.3 Before vaccine was introduced in 1963, 3 to 4 million cases per year occurred, and caused, on average, 450 deaths, 1000 chronic disabilities, and 28,000 hospitalizations.1 Success in controlling measles is due largely to high levels of coverage with 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine and public health surveillance and disease control.

Measles virus is highly infectious and is spread by airborne droplets and direct contact with nose and throat secretions. The incubation is 7 to 18 days.

Measles begins with fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and whitish spots on the buccal mucosa (Koplick spots).4 Rash appears on the 3rd to 7th day and lasts 4 to 7 days. It begins on the face but soon becomes generalized. An infected person is contagious from 5 days before the rash until 4 days after the rash appears. The diagnosis of measles can be confirrmed by serum measles IGM, which occurs within 3 days of rash, or a rise in measles IGG between acute and 2-week convalescent serum titers.

Complications: pneumonia (5%), otitis media (10%), and encephalitis 1/1000). Death rates: 1 to 2/1000, varying greatly based on age and nutrition; more severe in the very young and the malnourished. Worldwide, about 500,000 children die from measles each year.5

Immunity is defined as:

- 2 vaccine doses at least 1 month apart, both given after the 1st birthday,

- born before 1957,

- serological evidence, or

- history of physician-diagnosed measles.

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians

Include measles in the differential diagnosis of patients who have fever and rash, especially if they have traveled to another country within the past 3 to 4 weeks. Any patient who meets the definition of measles (fever 101ºF or higher; rash; and at least 1 of the 3 Cs—cough, coryza, conjunctivitis) should be immediately reported to the local health department. The health department will provide instructions for collecting laboratory samples for confirmation; instructions on patient isolation; and assistance with notification and disease control measures for exposed individuals.

Immunize patients and staff. These recurring cases of imported measles underscore the importance of maintaining a high level of immunity. Outbreaks can happen even where immunity is 90% to 95%. When vaccination rates dip below 90%, sustained outbreaks can occur.6

Ensure that staff and patients are all immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases, and inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated place their children at risk and contribute to higher community risk. Communities that have higher rates of non-adherence to vaccine recommendations are more likely to have outbreaks.7,8

Use strict infection control in the office. The recent outbreak in California where 4 children were infected in their physician’s office reinforces the need for strict infection-control practices. Do not allow patients with rash and fever to remain in a common waiting area. Move them to an examination room, preferably an airborne infection isolation room. Keep the door to the examination room closed, and be sure that all health care personnel who come in contact with such patients are immune. Do not use triage rooms for 2 hours after the patient suspected of having measles leaves. Do not send these patients to other health care facilities, such as laboratories, unless infection control measures can be adhered to at those locations. Guidelines on infection control practices in health care settings are available.9,10

Quick response

Quick control of these outbreaks shows the value of the public health infrastructure. Disease surveillance and outbreak response is vital to the public health system, and its value is frequently under-appreciated by physicians and the public.

Fewer than 100 cases of measles occur in the United States each year, and virtually all are linked to imported cases.3 Before vaccine was introduced in 1963, 3 to 4 million cases per year occurred, and caused, on average, 450 deaths, 1000 chronic disabilities, and 28,000 hospitalizations.1 Success in controlling measles is due largely to high levels of coverage with 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine and public health surveillance and disease control.

Measles virus is highly infectious and is spread by airborne droplets and direct contact with nose and throat secretions. The incubation is 7 to 18 days.

Measles begins with fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and whitish spots on the buccal mucosa (Koplick spots).4 Rash appears on the 3rd to 7th day and lasts 4 to 7 days. It begins on the face but soon becomes generalized. An infected person is contagious from 5 days before the rash until 4 days after the rash appears. The diagnosis of measles can be confirrmed by serum measles IGM, which occurs within 3 days of rash, or a rise in measles IGG between acute and 2-week convalescent serum titers.

Complications: pneumonia (5%), otitis media (10%), and encephalitis 1/1000). Death rates: 1 to 2/1000, varying greatly based on age and nutrition; more severe in the very young and the malnourished. Worldwide, about 500,000 children die from measles each year.5

Immunity is defined as:

- 2 vaccine doses at least 1 month apart, both given after the 1st birthday,

- born before 1957,

- serological evidence, or

- history of physician-diagnosed measles.

1. CDC. Outbreak of measles—San Diego, California, January-February 2008. MMWR. 2008;57:Early Release February 22, 2008.-

2. CDC. Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August-September 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:169-173.

3. CDC. Measles—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55:1348-1351.

4. Measles. In: Heyman DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

5. CDC. Parents’ guide to childhood immunizations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/measles/downloads/pg_why_vacc_measles.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2008.

6. Richard JL, Masserey-Spicher V, Santibanez S, Mankertz A. Measles outbreak in Switzerland. Available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/edition/v13n08/080221_1.asp. Accessed March 17. 2008.

7. Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws; individual and societal risk of measles. JAMA. 1999;282:47-53

8. Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, et al. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA. 2008;284:3145-3150.

9. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory committee, 2007.Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(suppl 2):S65-164.

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Infection control in outpatient settings. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:485-488.

1. CDC. Outbreak of measles—San Diego, California, January-February 2008. MMWR. 2008;57:Early Release February 22, 2008.-

2. CDC. Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August-September 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:169-173.

3. CDC. Measles—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55:1348-1351.

4. Measles. In: Heyman DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

5. CDC. Parents’ guide to childhood immunizations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/measles/downloads/pg_why_vacc_measles.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2008.

6. Richard JL, Masserey-Spicher V, Santibanez S, Mankertz A. Measles outbreak in Switzerland. Available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/edition/v13n08/080221_1.asp. Accessed March 17. 2008.

7. Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws; individual and societal risk of measles. JAMA. 1999;282:47-53

8. Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, et al. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA. 2008;284:3145-3150.

9. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory committee, 2007.Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(suppl 2):S65-164.

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Infection control in outpatient settings. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:485-488.

Helping patients kick the "other" habit

- Nicotine replacement therapy may be useful for short-term treatment of cravings, but may not improve cessation rates among patients who use smokeless tobacco (B).

- Patients who use >3 cans of smokeless tobacco a day may need higher than normal doses (42 mg/day) of nicotine replacement therapy (B).

- Evidence is insufficient to support the routine use of bupropion (Zyban) for smokeless tobacco cessation. It should be initiated at the physician’s discretion (B).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Through with Chew Week” and the “Great American Spitout.” Do they ring a bell?

If you answered no, you’re not alone.

“Through with Chew Week” was established by the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) in 1989, but it hasn’t quite garnered the same kind of recognition as the American Cancer Society’s Great American Smokeout.

When it comes to tobacco use—and more importantly, cessation—smokeless tobacco just doesn’t generate the kind of attention that cigarette smoking does. In fact, smokeless tobacco’s low profile extends beyond talk of “smokeouts” and “spitouts” to research on effective ways to quit.

We found this out first-hand when we conducted a literature search of Medline, PubMed, and a number of other databases to learn which cessation methods have proven efficacy. What we learned is that not only is research on the subject of smokeless tobacco cessation limited, but there is no recommended medication therapy to help these patients quit. Specifically:

- Nicotine-replacement therapies have failed to demonstrate a clear benefit in smokeless tobacco cessation, but under-dosing may be a factor for some patients.

- Bupropion’s (Zyban) usefulness in smokeless tobacco cessation is unclear. Data, thus far, have been inconclusive.

- Varenicline’s (Chantix) usefulness in smokeless tobacco cessation is unknown. There are no published case reports or clinical trials on the subject.

Millions of “chew” users are at risk

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of premature death in the United States, with more than 440,000 Americans dying of tobacco-related disease each year.1 Cigarette smoking is by far the most common form of tobacco used; however, smokeless tobacco, also known as chew, spit tobacco, or snuff, is used by 8.2 million Americans.2 More men than women use tobacco products overall, and smokeless tobacco, in particular.2

Health risks include MI. Specific health risks associated with smokeless tobacco include cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, oral and periodontal disease, tooth decay, and pregnancy-related problems.1 (See “Smokeless tobacco was to blame”)

In addition, an international, case-control study evaluating the risk of myocardial infarction associated with various forms of tobacco use found an increased risk of myocardial infarction associated with smokeless tobacco use compared to non-tobacco users (odds ratio [OR]=2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.41-3.52).3

Notably, smokeless tobacco users in the study who also smoked cigarettes had the highest risk of all tobacco users when compared to non-users (OR=4.09; 95% CI, 2.98-5.61). These findings demonstrate that nicotine dependence is detrimental to health—regardless of the form of tobacco used. Even more worrisome is the notion that risk may actually be increased when multiple forms of tobacco are used by the same patient.

Patients want medication to help them quit

Current guidelines for tobacco cessation recommend that patients using smokeless tobacco should be identified, urged to quit, and treated with counseling interventions.4 Despite this recommendation, many patients are interested in using a medication to aid them in their quit effort, and many physicians would like to prescribe medication to help patients succeed.

To that end, it seemed logical to us that the same treatments used for smoking cessation would also be effective for smokeless tobacco cessation, given that the underlying problem—despite the form of tobacco used—is nicotine dependence. So we did a literature review to determine the optimal treatment for smokeless tobacco cessation. Our search included: Medline (1950-2007), PubMed (1966-2006), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970-2006), Science Direct, CINAHL, PsycArticles, and Dissertation Abstracts. We used the following search terms: smokeless tobacco, spit tobacco, chew tobacco, cessation, bupropion, nicotine, and nicotine replacement. (Searches in Medline for nicotine replacement therapy in smokeless tobacco cessation were limited to clinical trials.) What we found were a limited number of studies, which we’ve summarized here.

Nicotine patch is useful, but to what degree?

We reviewed four studies involving the use of a nicotine patch for smokeless tobacco cessation (TABLE 1). In chronological order:

Study #1: 15-mg patch. The first study to evaluate the nicotine patch was a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial published in 1999. A 15-mg nicotine patch was used by approximately 420 patients.5 Patients included in the trial were at least 18 years of age, nonsmokers, and used at least 1 can of smokeless tobacco per week. The main outcome of this trial was cessation at 6 months.

A significant difference was found in abstinence rates between patients treated with active therapy compared to those treated with placebo early in the study; however, by study end, there were no significant differences between groups. The medication was well tolerated, though patients receiving active therapy did report an increase in adverse effects related to patch use, such as rash and itching.

TABLE 1

Conflicting findings on the nicotine patch for smokeless tobacco cessation

| STUDY (YEAR) | POPULATION | INTERVENTION | COUNSELING | DURATION | RESULTS | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Howard-Pitney5 (1999) | 420 patients • ≥18 years, nonsmokers • ≥1 can/week | • Nicotine patch (15 mg) • Placebo patch | • Written materials • Telephone contact | 6 months | No significant difference in cessation rates | N/A |

| Hatsukami6 (2000) | 400 patients • 1 can/week | • Nicotine patch (began on 22 mg and tapered to 7 mg by study end) + mint snuff • Nicotine patch (same tapering as above) + no mint snuff • Placebo patch + mint snuff • Placebo patch + no mint snuff | • Written materials • 10 minute behavioral counseling | 10 weeks | Patients receiving active NRT had significantly higher quit rates at 10 and 15 weeks (P=0.002 and 0.016, respectively) | Patients with mint snuff: • 10 weeks: 4.3 • 15 weeks: 5.5 Patients w/o mint snuff: • 10 weeks: 14.3 • 15 weeks: 20 |

| Stotts7 (2003) | 300 patients • 14- to 19- year-old males • ST use ≥5 days/week | • Nicotine patch • Placebo patch • Usual care | • Patch: Six, 50- minute behavioral counseling sessions • Usual care: one, 5- to 10-minute counseling session with one follow-up telephone contact | 1 year | No significant difference in cessation rates at 1 year | N/A |

| Ebbert8 (2007) | 42 patients • ≥18 years, in good health • ≥3 cans or pouches/day | • Nicotine patch (21, 42, or 63 mg/day) • Placebo patch | • None | 3 days | NRT with 42 mg/day provided similar levels of nicotine to active ST users | N/A |

| NNT, number needed to treat; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; ST, smokeless tobacco. | ||||||