User login

Caring for patients with co-occurring mental health & substance use disorders

THE CASE

Janice J* visits her family physician with complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, and heart palpitations that are usually worse at night. Her medical history is significant for deep vein thrombosis secondary to an underlying hypercoagulability condition (rheumatoid arthritis) diagnosed 2 months earlier. She also has a history of opioid use disorder and has been on buprenorphine/naloxone therapy for 3 years. Her family medical history is unremarkable. She works full-time and lives with her 8-year-old son. On physical exam, she appears anxious; her cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal. A completed workup rules out cardiac or pulmonary problems.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS: SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Co-occurring disorders, previously called “dual diagnosis,” refers to the coexistence of a mental health disorder and a substance use disorder. The obsolete term, dual diagnosis, specified the presence of 2 co-occurring Axis I diagnoses or the presence of an Axis I diagnosis and an Axis II diagnosis (such as mental disability). The change in nomenclature more precisely describes the co-existing mental health and substance use disorders.

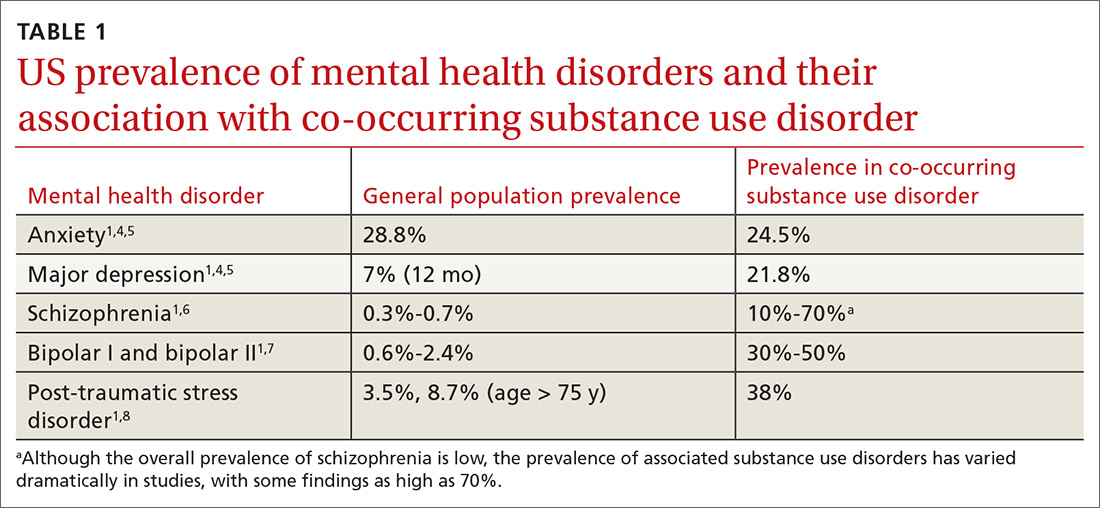

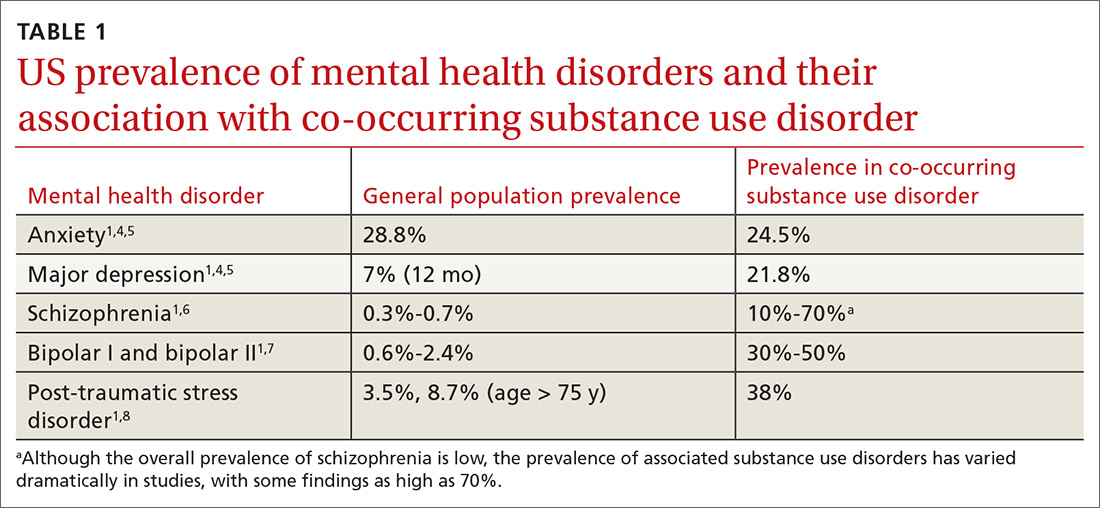

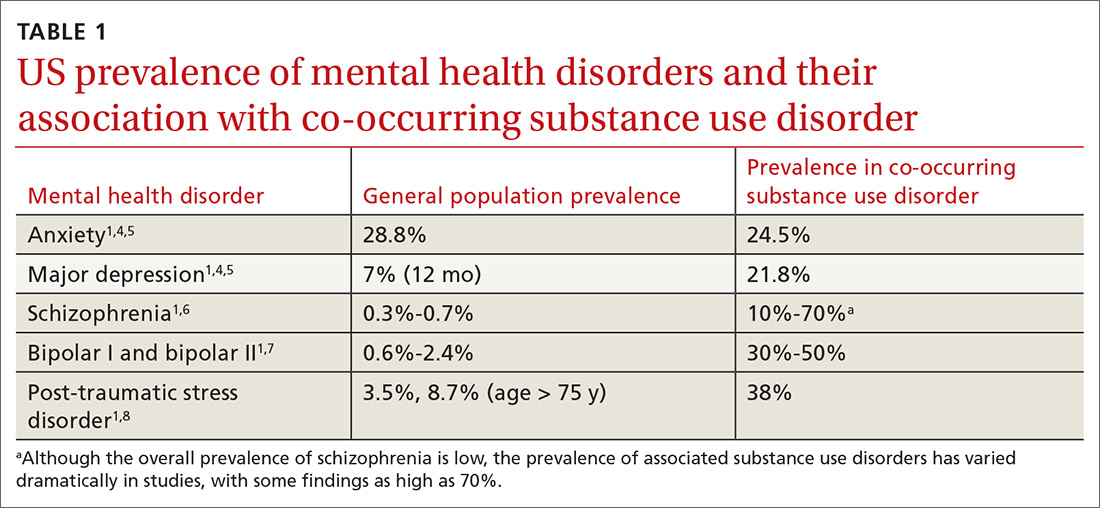

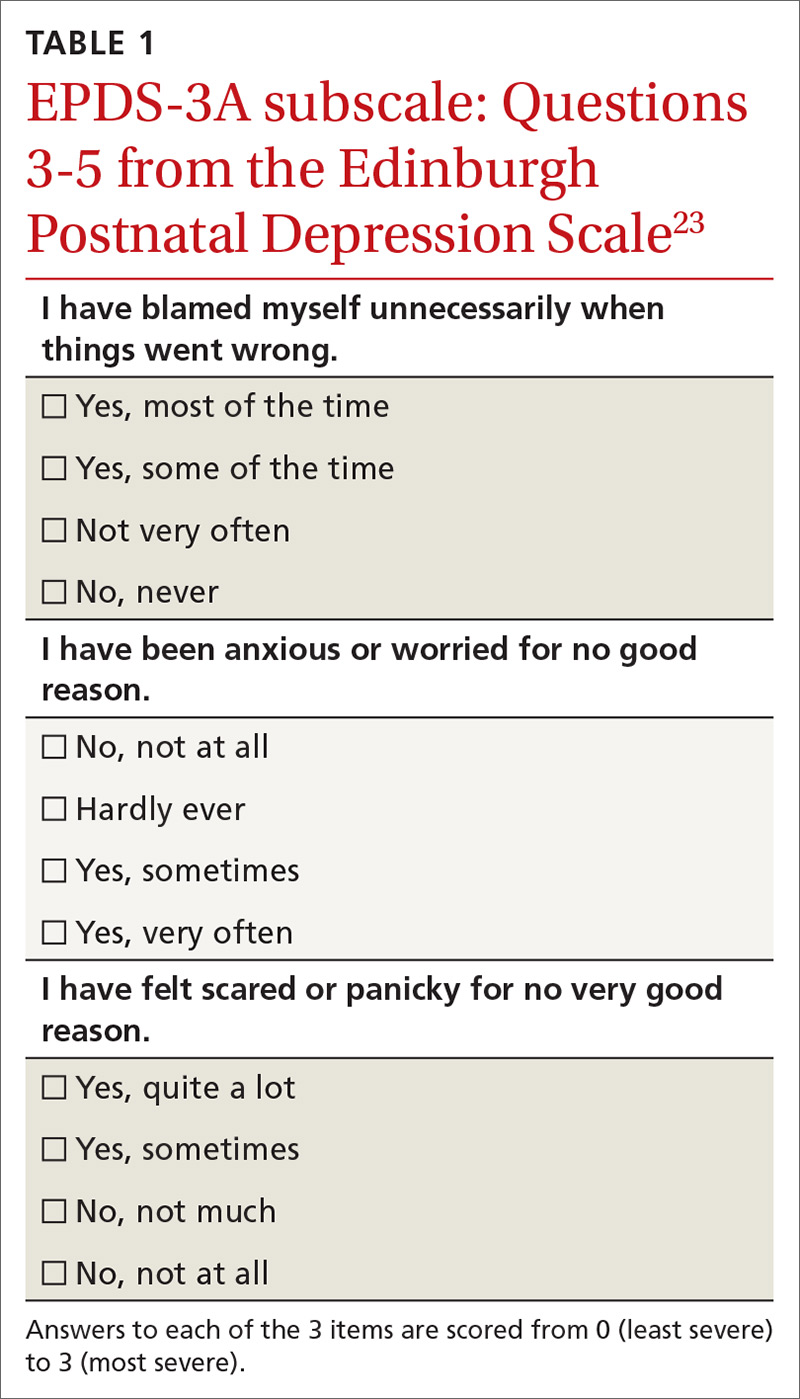

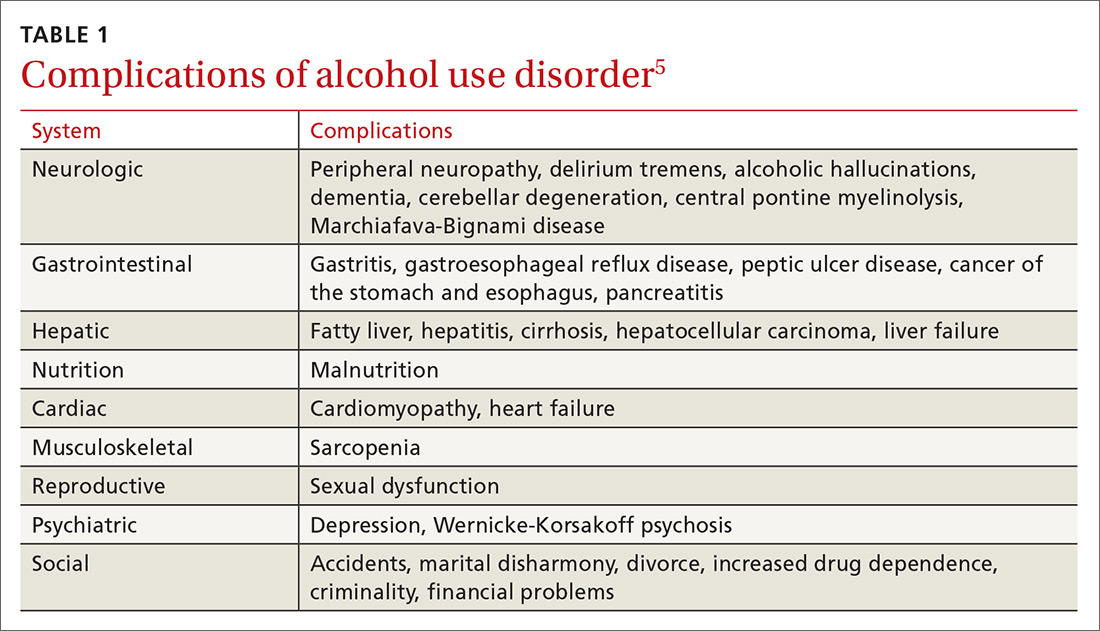

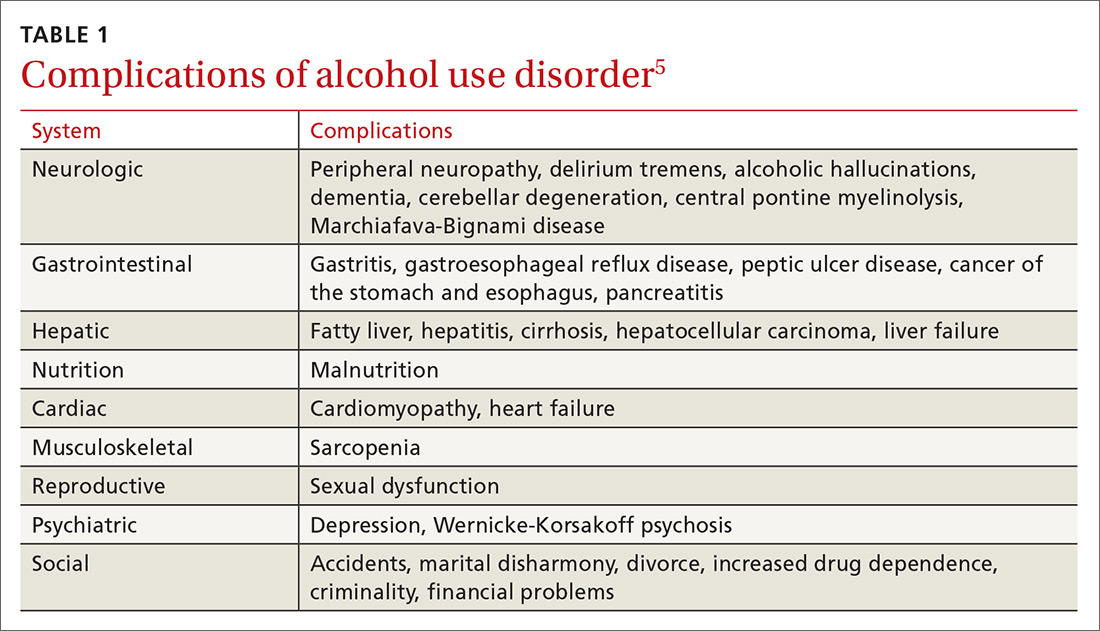

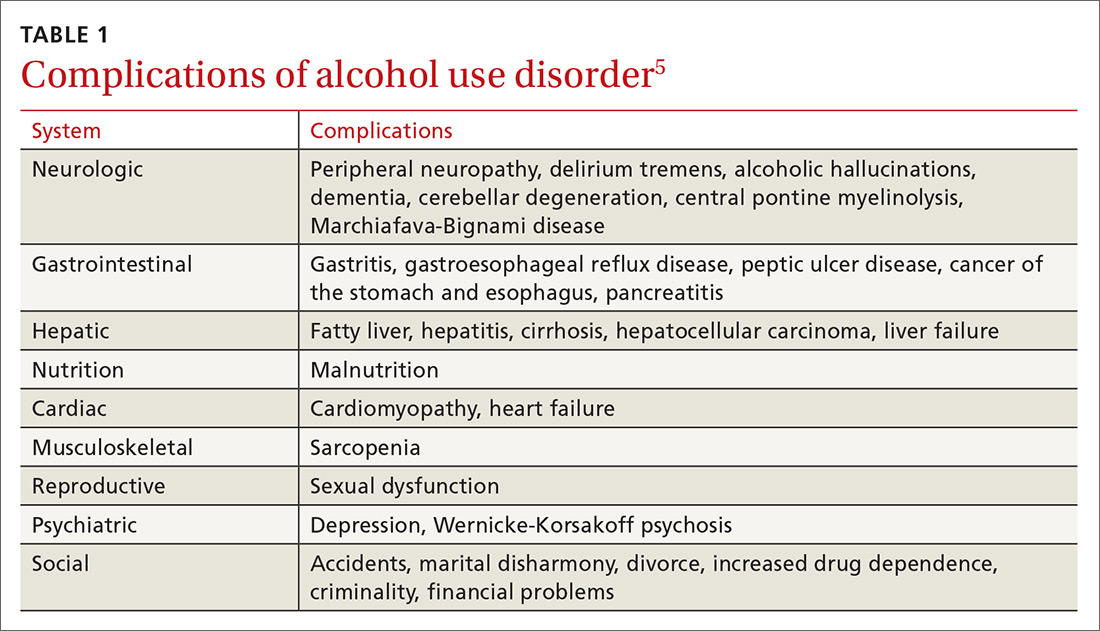

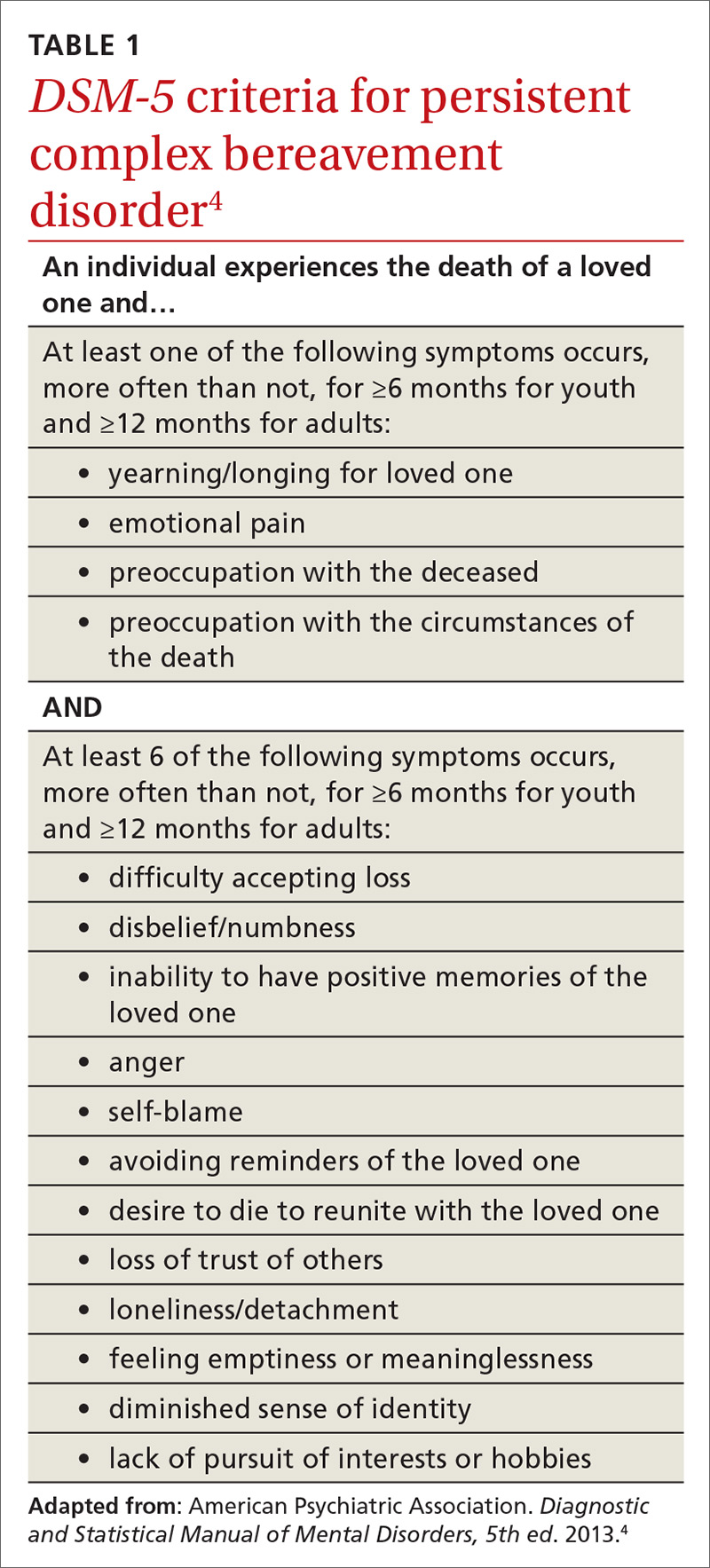

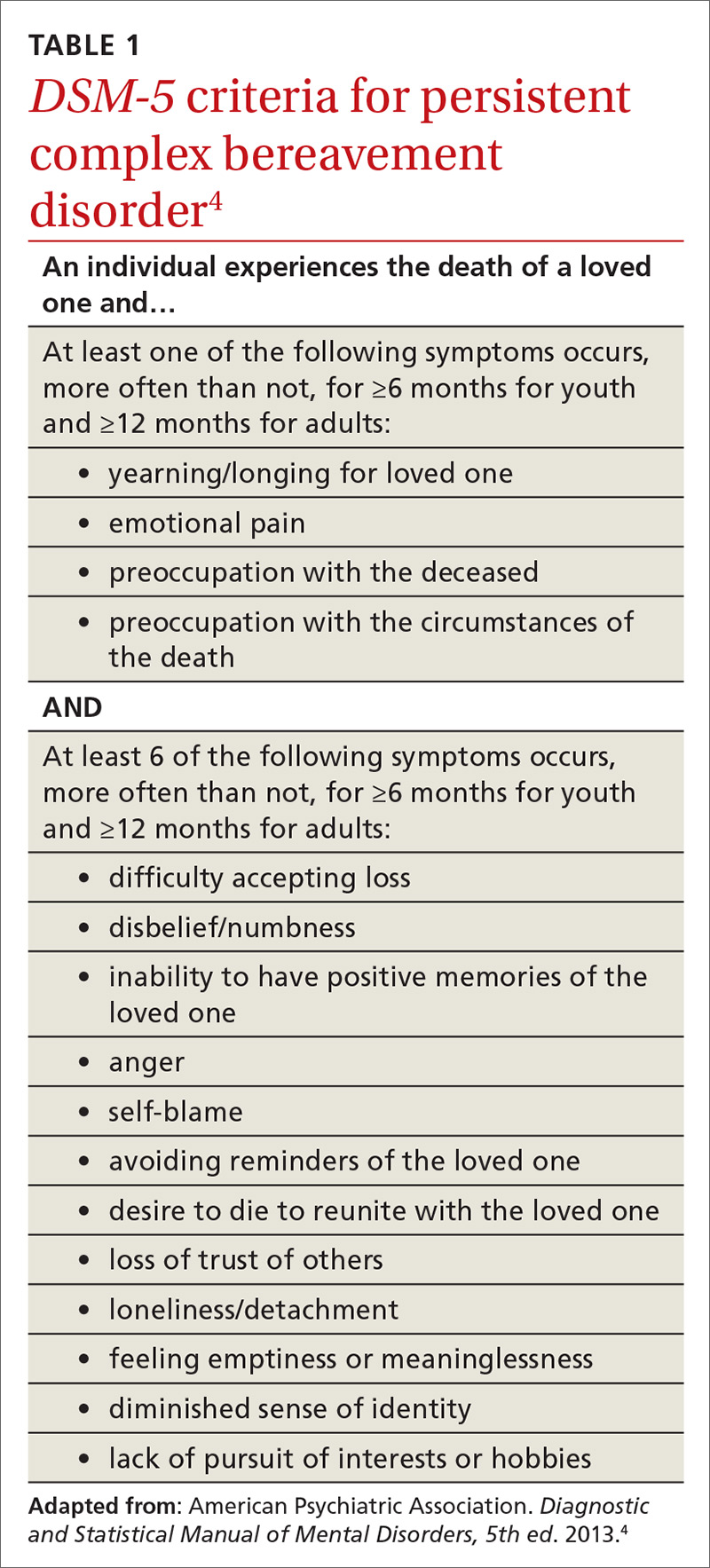

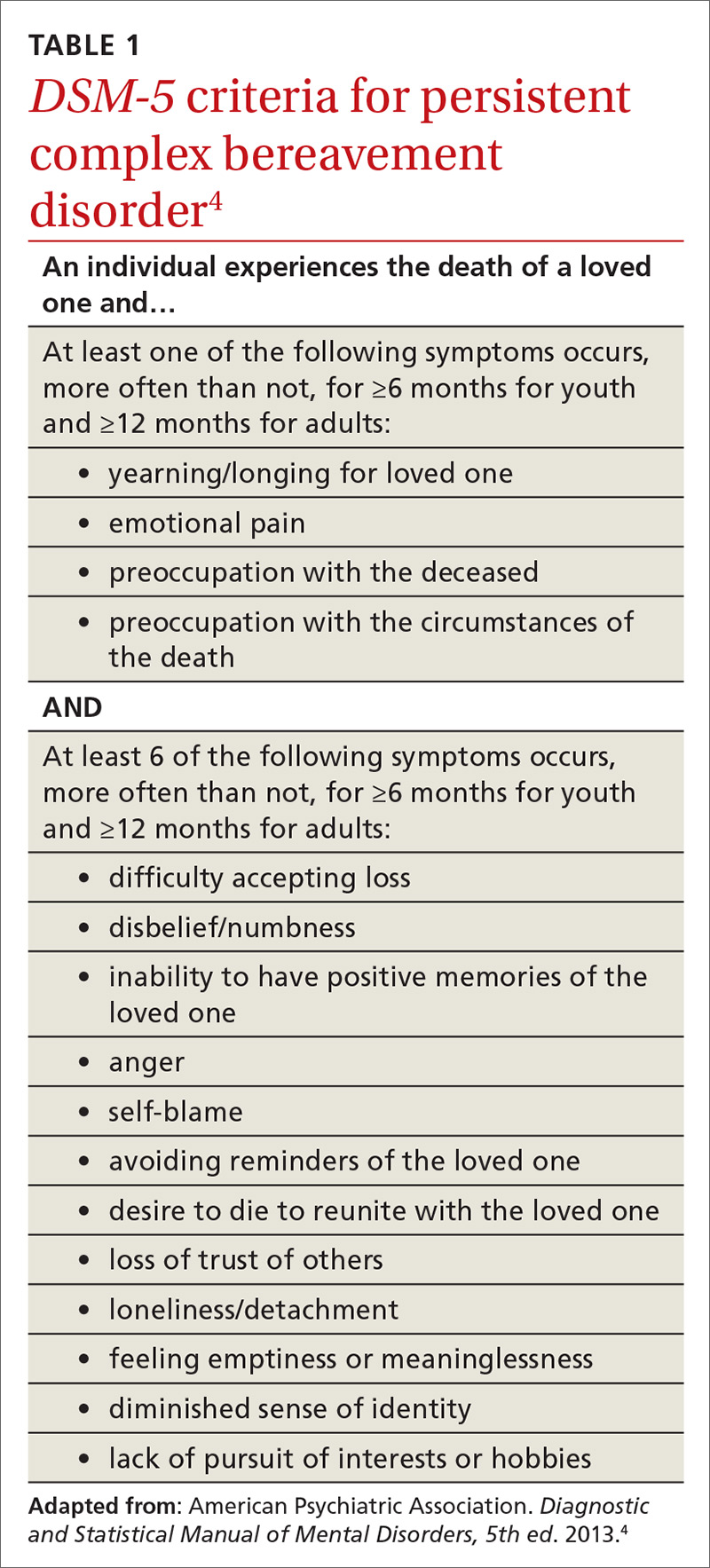

Currently the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, (DSM-5) includes no diagnostic criteria for this dual condition.1 The criteria for mental health disorders and for substance use disorders comprise separate lists. Criteria for substance use disorder fall broadly into categories of “impaired [self] control, social impairment, risky behaviors, increased tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms.”1 It is estimated that 8.5 million US adults have co-occurring disorders, per the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.2 Distinguishing which of the 2 conditions occurred first can be challenging. It has been suggested that the lifetime prevalence of a mental health disorder with a coexisting substance use disorder is greater than 40%3,4 (TABLE 11,4-8). For patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, these numbers may be higher.

The consequences of undiagnosed and untreated co-occurring disorders include poor medication adherence, physical comorbidities (and decreased overall health), diminished self-care, increased suicide risk or aggression, increased risky sexual behavior, and possible incarceration.9

WHEN SHOULD YOU SUSPECT CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS?

Diagnosing a second condition can also be difficult when a patient’s symptoms are actually adverse effects of substances or prescribed medications. For example, a patient with worsening anxiety may also exhibit increasing blood pressure resistant to treatment. The cause of the patient’s fluctuating blood pressures may actually be the result of his or her use of alcohol to self-treat the anxiety. In addition to self-medication, other underlying factors may be at play, including genetic vulnerability, environment, and lifestyle.14 In the case we present, the patient’s conditions arose independently.

Anxiety disorders, with a lifetime risk of 28.8% in the US population,4 may be the primary mental health issue in many patients with co-occurring disorders, but this cannot be assumed in lieu of a complete workup.2,8,9,15 Substance use disorders in the general population have a past-year and lifetime prevalence of 14.6%.1,4,16,17 Because the causal and temporal association between anxiety and substance abuse is not always clear, it’s important to separate the diagnoses of the mental health and substance use disorders.

Continue to: MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

To make an accurate diagnosis of co-occurring disorder, it is essential to take a complete history focusing on the timeline of symptoms, previous diagnoses and treatments, if any, and substance-free periods. Details gathered from these inquiries will help to separate symptoms of a primary mental health disorder from adverse effects of medication, withdrawal symptoms, or symptoms related to an underlying chronic medical condition.

Optimally, the diagnosis of a mental health disorder should be considered following a substance-free period. If this is not possible, a chart review may reveal a time when the patient did not have a substance use disorder.18

A diagnosis of substance use disorder requires that the patient manifest at least 2 of 11 behaviors listed in the DSM-5 over a 12-month period.1 The criteria focus on the amount of substance used, the time spent securing the substance, risky behaviors associated with the substance, and tolerance to the substance.

DON'T DEFER MENTAL HEALTH Tx

It is necessary to treat co-occurring disorders simultaneously. The old idea of deferring treatment of a mental health issue until the substance use disorder is resolved no longer applies.19,20 Treating substance use problems without addressing comorbid mental health issues can negatively impact treatment progress and increase risk for relapse. In a similar way, leaving substance use problems untreated is associated with nonadherence in mental health treatment, poor engagement, and dropout.21,22

Integrated services. Due to this condition’s level of clinical complexity, the optimal treatment approach is an interdisciplinary one in which integrated services are offered at a single location by a team of medical, mental health, and substance use providers (see “The case for behavioral health integration into primary care” in the June issue). An evidence-based example of such an approach is the Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) model—a comprehensive, integrated method of treating severe mental health disorders, including substance use disorders.21,22 IDDT combines coordinated services such as pharmacologic, psychological, educational, and social interventions to address the needs of patients and their family members. The IDDT model conceptualizes and treats co-occurring disorders within a biopsychosocial framework. Specific services may include medical detoxification, pharmacotherapy, patient and family education, behavioral and cognitive therapies, contingency management, self-help support groups, supported employment, residential/housing assistance, and case management services.23,24

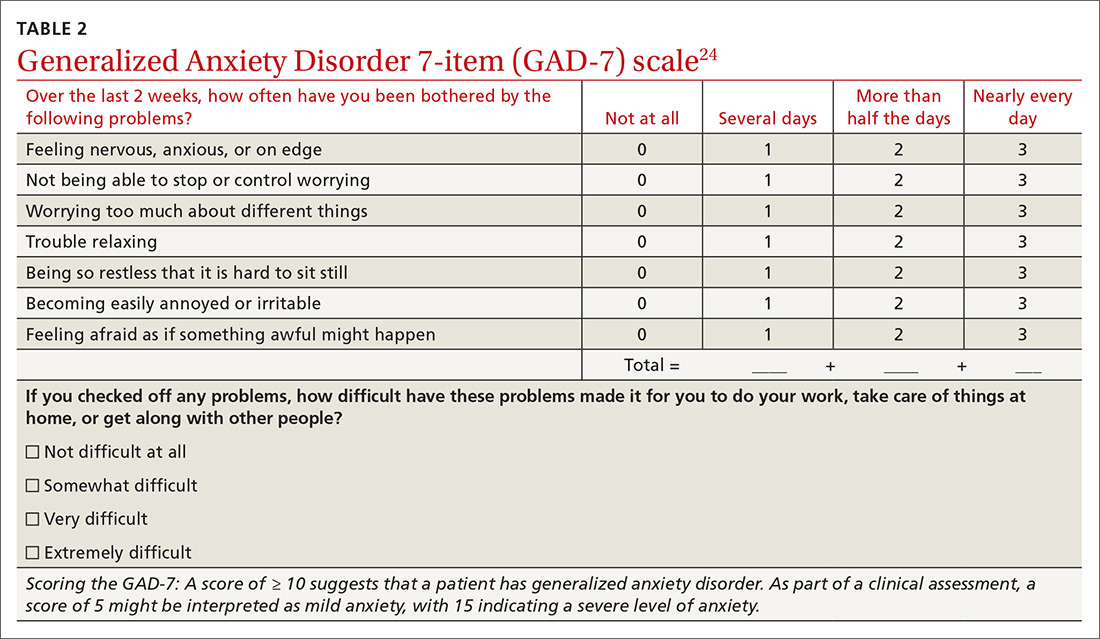

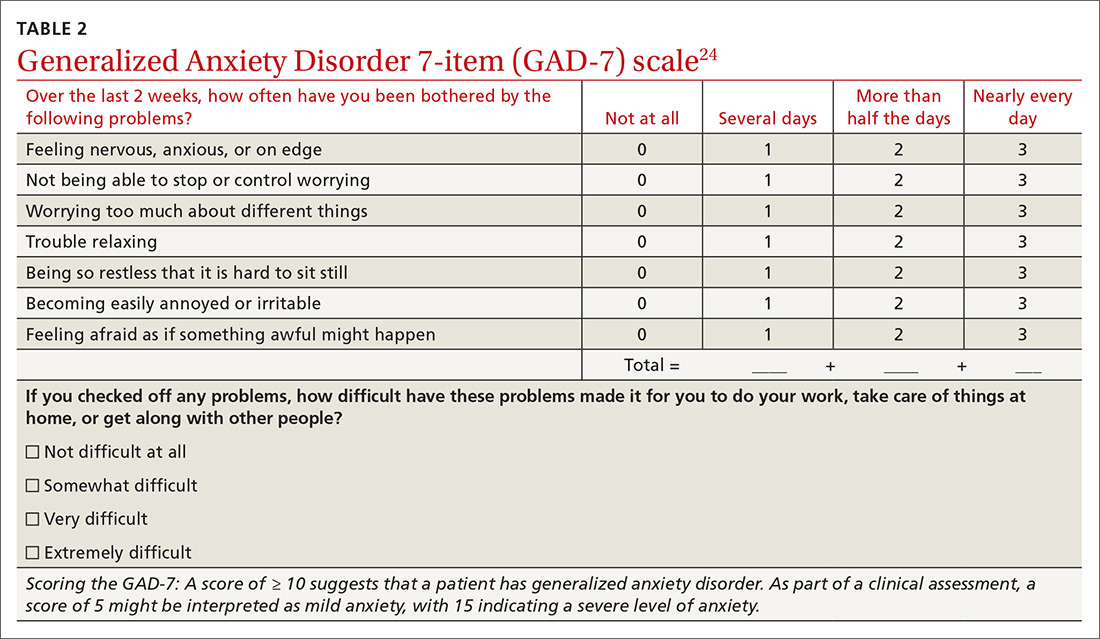

Continue to: Medications for the mental health component

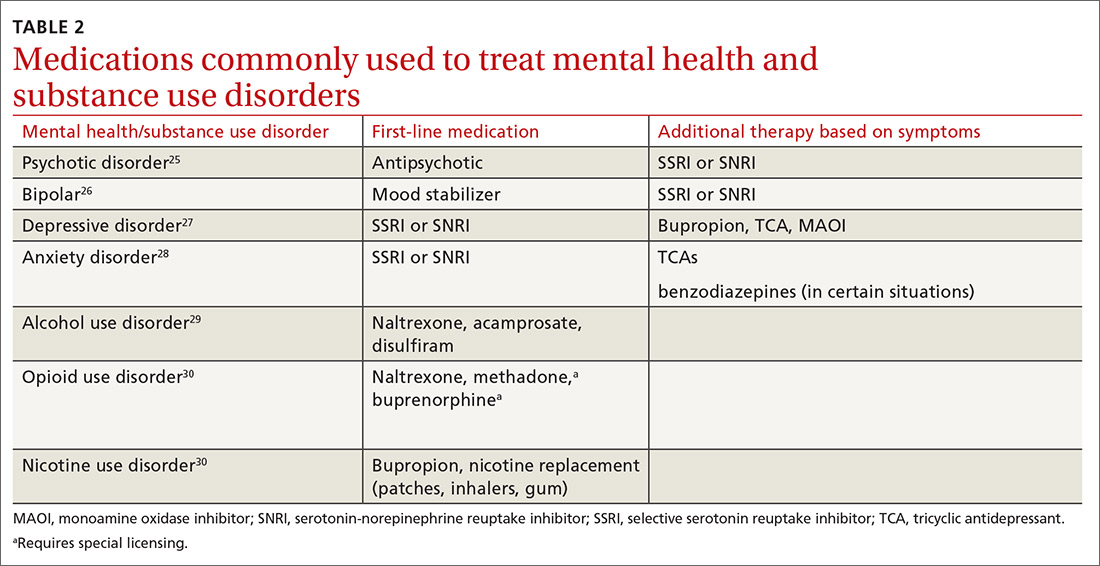

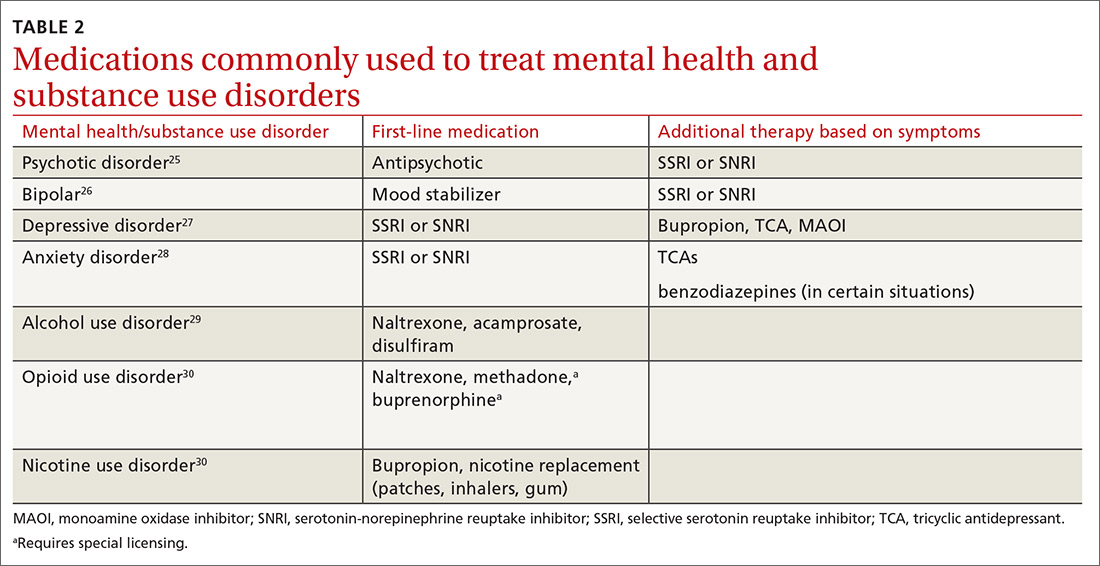

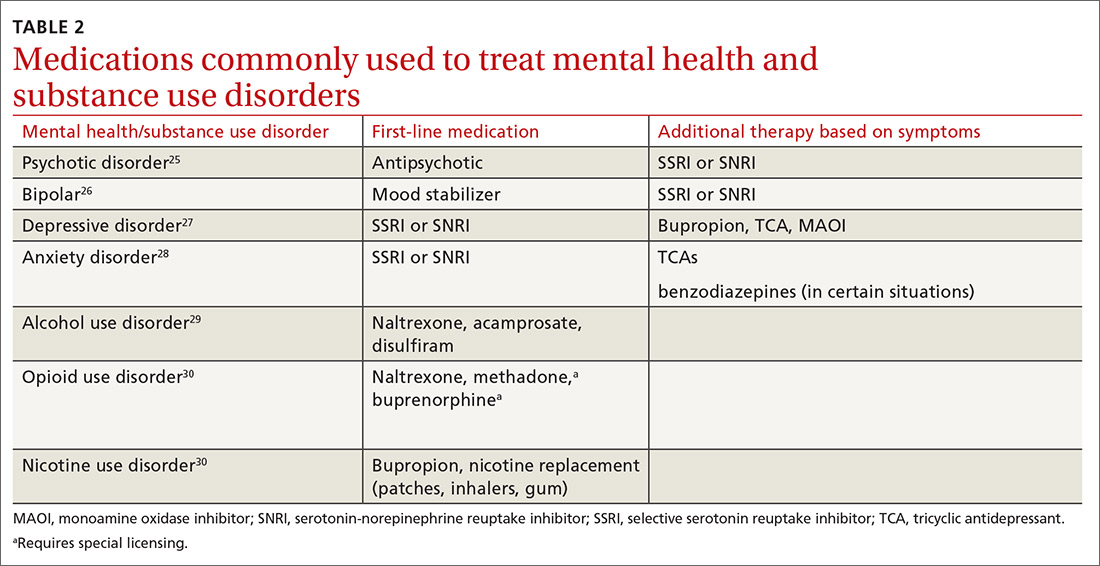

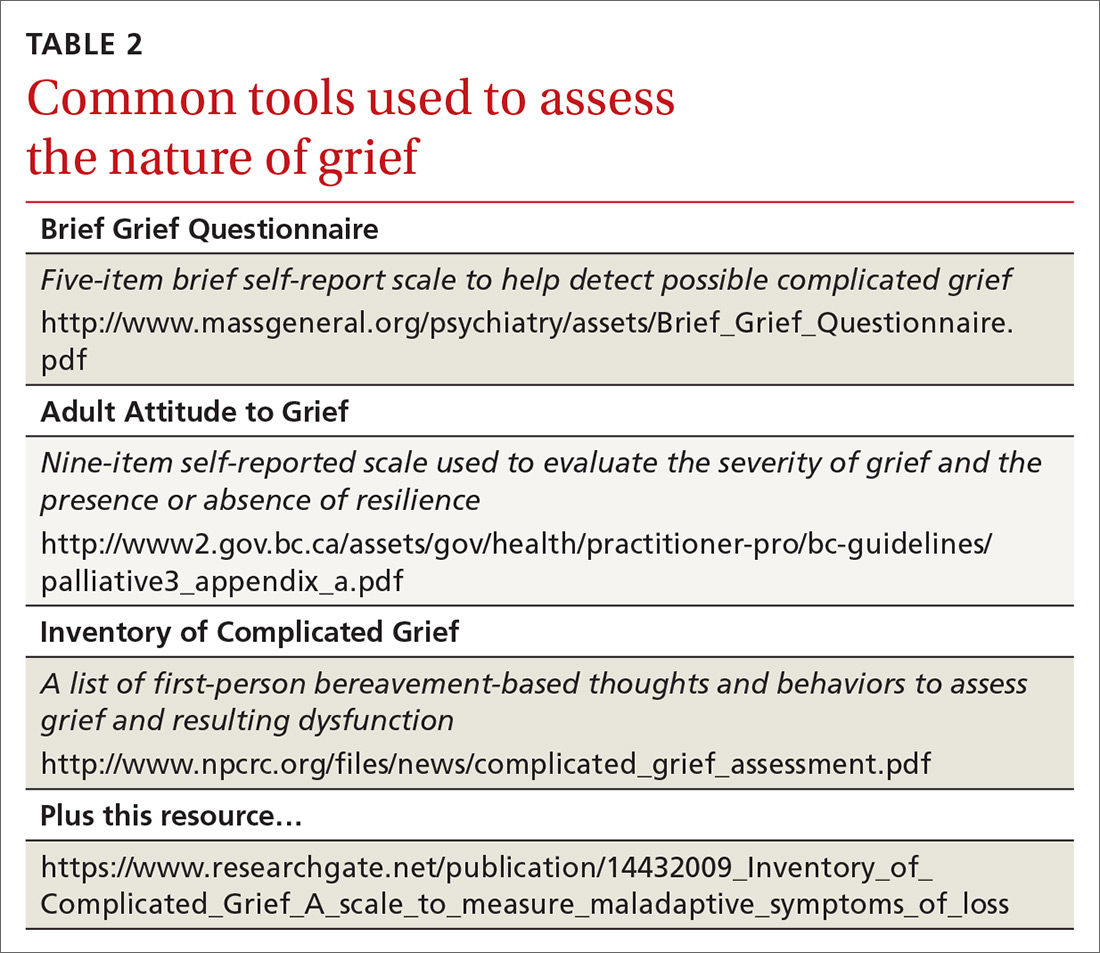

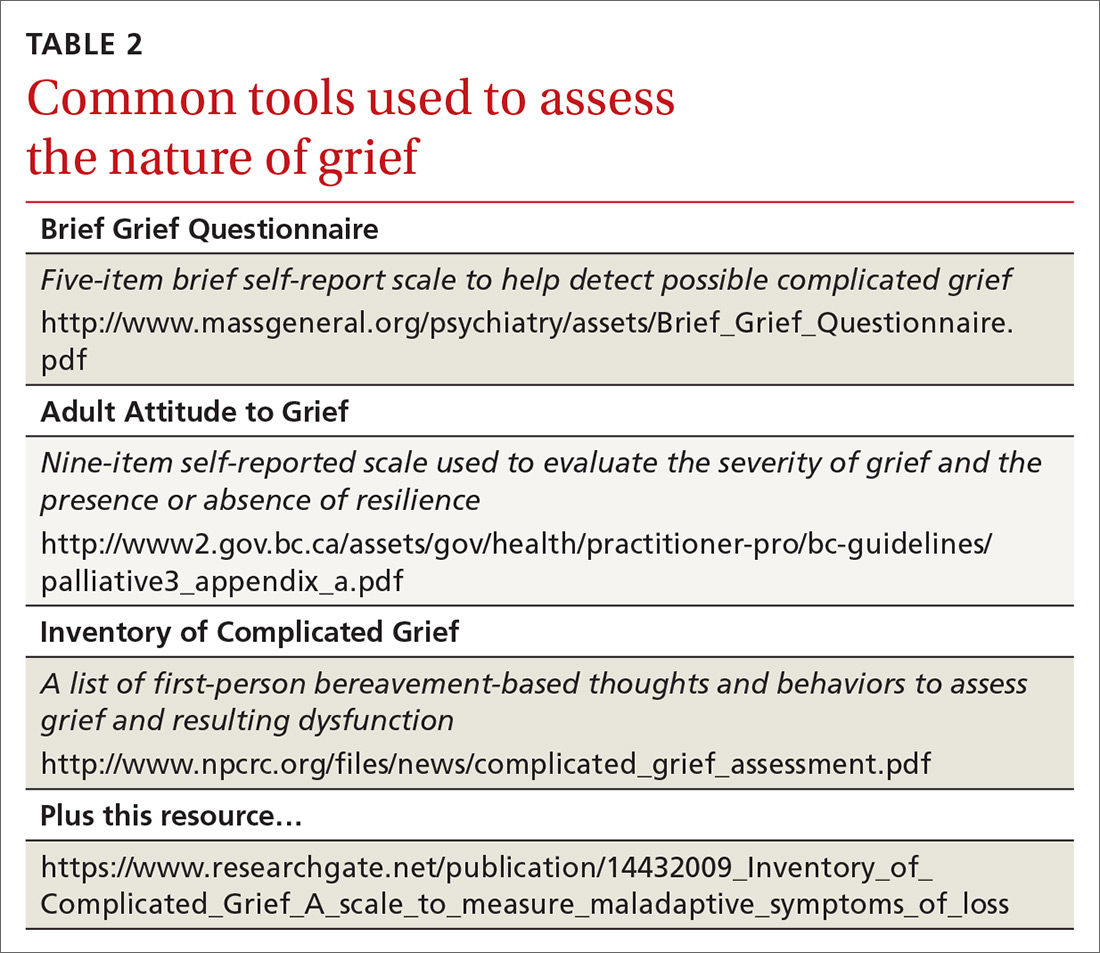

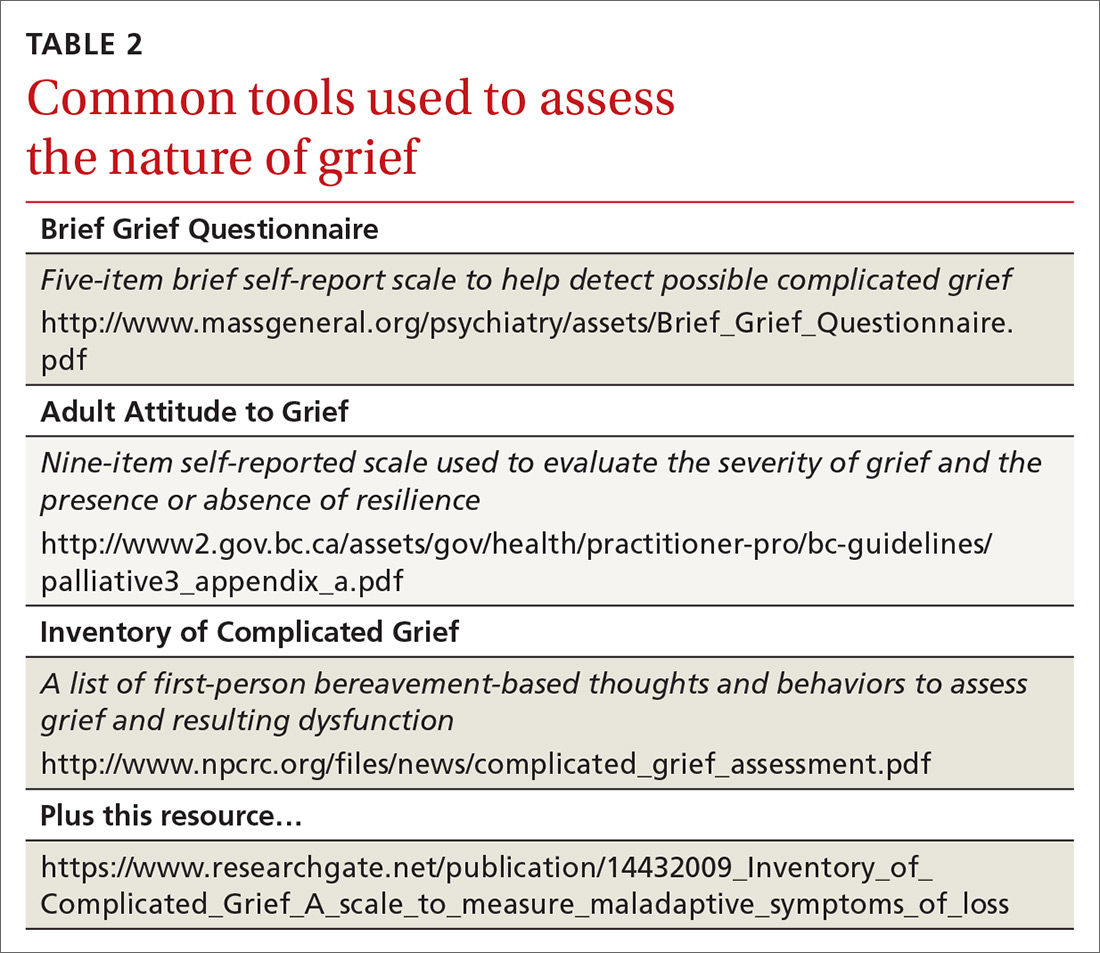

Medications for the mental health component. For patients who prefer medication treatment to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or for whom CBT is unavailable, treat the mental health disorder per customary practice for the diagnosis (TABLE 225-30). For psychotic disorders, use an antipsychotic, adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) as needed depending on the presence of negative symptoms.25,31 For bipolar spectrum disorder, start a mood stabilizer32; for depressive disorders initiate an SSRI or SNRI.27 Anxiety disorders respond optimally when treated with SSRIs or SNRIs. Buspirone may be prescribed alone or as an adjunct for anxiety, and it does not cause mood-altering or withdrawal effects. Benzodiazepines in a controlled and monitored setting are an option in some antianxiety treatment plans. Consultation with a psychiatrist will help to determine the best treatment in these situations.

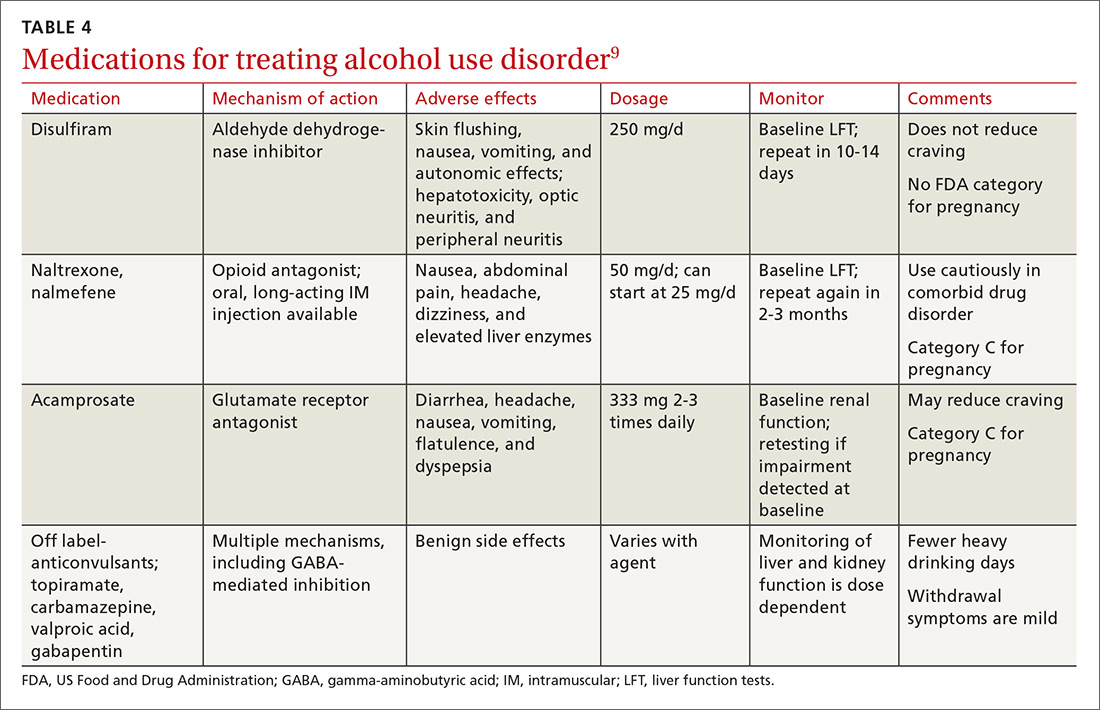

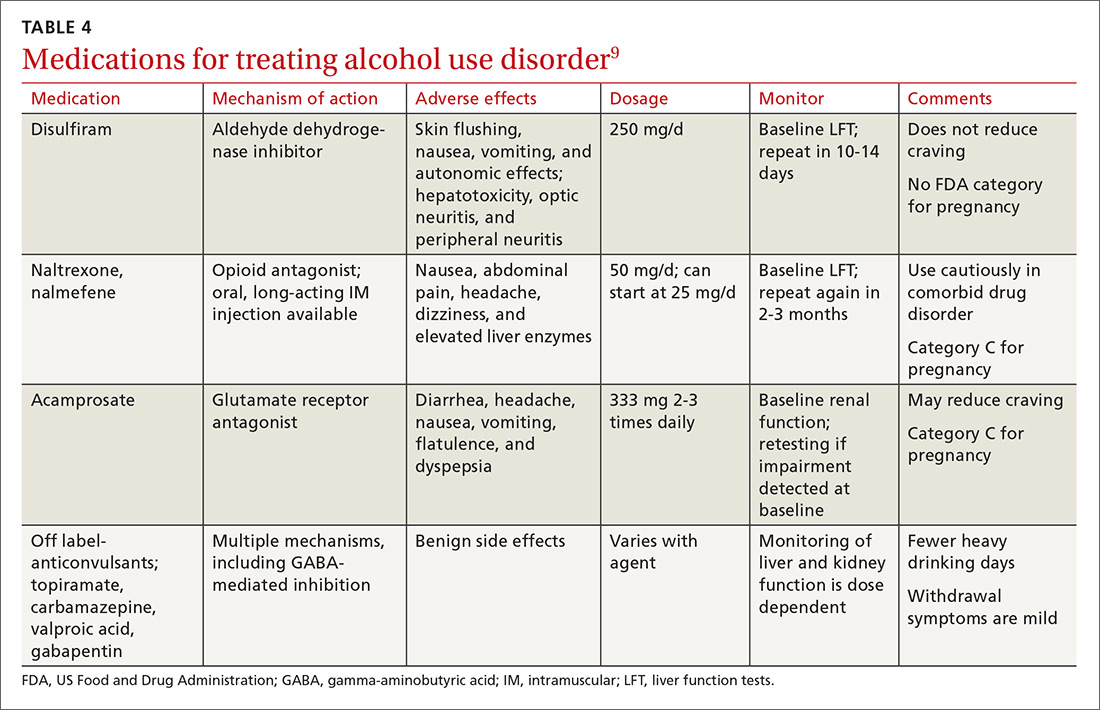

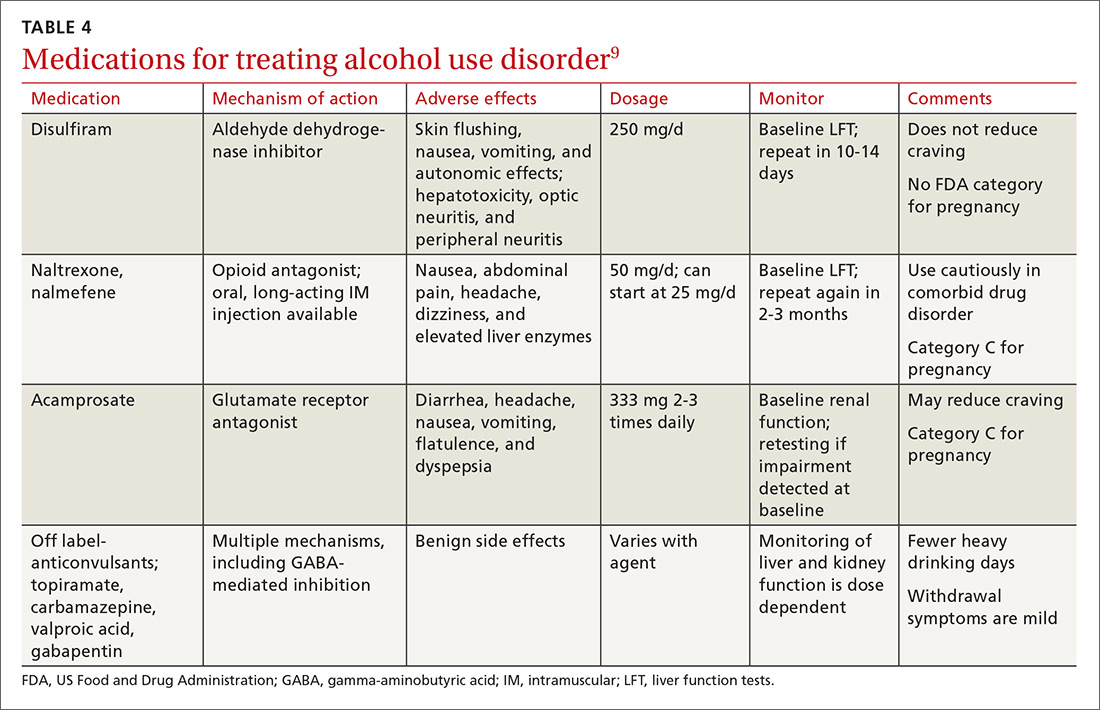

In all cases, treat the substance use disorder concurrently. Treatment options vary depending on the substance of choice. Although often overlooked, there can be simultaneous nicotine abuse. Oral or inhaled medications for nicotine abuse treatment are limited. The range of pharmacologic options for alcohol use disorder includes naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.29,33 Pharmacologic treatment options for opioid use disorder include naltrexone, methadone, and a combination of naloxone and buprenorphine.34

Physicians who wish to prescribe buprenorphine must qualify for and complete a certified 8 hour waiver-training course, which is then approved by the Drug Enforcement Agency (under the DATA 2000 – Drug and Alcohol Act 2000). The physician obtains the designation of a data-waived physician and is assigned a special identification number to prescribe these medications.35,36 Methadone may be provided only in a licensed methadone maintenance program. Regular and random drug urine screen requirements apply to all treatment programs.

Psychosocial and behavioral interventions are essential to the successful treatment of co-occurring disorders. Evidence-based behavioral and cognitive therapies are recommended for promoting adaptive coping skills and healthy lifestyle behaviors in co-occurring disorder populations.23,24,37-40 Motivational interviewing enhances motivation and adherence when patients demonstrate resistance or ambivalence.41,42 Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective and may be particularly beneficial for treating cravings/urges and promoting relapse prevention.37,39,40,43-46

Psychotropic medications, as with other treatment components, are most effective when used in combination with services that simultaneously address the patient’s biological, psychological, and social needs.

Continue to: The grassroots organization...

The grassroots organization National Alliance on Mental Illness (www.nami.org) recommends self-help and support groups, which include 12-step, faith-based and non-faith–based programs.20

For any treatment method to be successful, there needs to be a level of customization and individualization. Some patients may respond to medication or nonmedication treatments only, and others may need a combination of treatments.

CASE

The physician recalls a past diagnosis of anxiety and asks Ms. J if there are any new stressors or changes causing concern. The patient expresses concern about an opioid use relapse secondary to her recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, which may be life altering or limiting.

Even though she has been doing well and has been adherent to her daily buprenorphine treatment, she worries for the well-being of her family and what would happen if she cannot work, becomes incapacitated, or dies at a young age. She has never considered herself an anxious person and is surprised that anxiety could cause such pronounced physical symptoms.

The physician discusses different modalities of treatment, including counseling with an onsite psychologist, a trial of an anti-anxiety medication such as sertraline, or return office visits with the physician. They decide first to schedule an appointment with the psychologist, and Ms. J promises to find more time for self-wellness activities, such as exercise.

After 3 months of therapy, the patient decides to space out treatment to every 2 to 3 months and does not report any more episodes of chest pain or shortness of breath.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Northwood-High Building, 2231 N. High Street, Suite 211, Columbus, OH 43201; [email protected].

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013.

2. SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm#cooccur2. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, et al. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247-257.

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

5. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

6. Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(suppl):S93-S100.

7. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241-251.

8. Cottler LB, Compton WM 3rd, Mager D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:664-670.

9. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168-176.

10. Burns L, Teesson M, O’Neill K. The impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on alcohol treatment outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100:787-796.

11. Magidson JF, Liu SM, Lejuez CW, et al. Comparison of the course of substance use disorders among individuals with and without generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:659666.

12. Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, et al. Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:476-484.

13. Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):76-88.

14. Buckley PF. Prevalence and consequences of the dual diagnosis of substance abuse and severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):5-9.

15. Salo R, Flower K, Kielstein A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in methamphetamine dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:356-361.

16. Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:147-156.

17. Buckner JD, Timpano KR, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:1028-1037.

18. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149-171.

19. McHugh RK. Treatment of co-occurring anxiety disorders and substance use disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:99-111.

20. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. NAMI Web site. www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/related-conditions/dual-diagnosis. Reviewed August 2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

21. SAMSHA. Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series No. 42. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-3992. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.

22. SAMHSA. Treatment of co-occurring disorders. In: Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005.

23. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:360-374.

24. Kola LA, Kruszynski R. Adapting the integrated dual-disorder treatment model for addiction services. Alcohol Treat Q. 2010;28:437-450.

25. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

27. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 23, 2019.

28. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed August 2, 2019.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969. Accessed August 2, 2019.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/substanceuse.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

31. Petrakis IL, Nich C, Ralevski E. Psychotic spectrum disorders and alcohol abuse: a review of pharmacotherapeutic strategies and a report on the effectiveness of naltrexone and disulfiram. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:644-654.

32. McIntyre RS, Yoon J. Efficacy of antimanic treatments in mixed states. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(suppl 2):22-36.

33. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876-880.

34. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:309-318.

35. US Department of Justice. DEA requirements for DATA waived physicians (DWPs). Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division Web site. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/docs/dwp_buprenorphine.htm. Accessed August 2, 2019.

36. SAMHSA. Buprenorphine waiver management. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/buprenorphine-waiver-management. SAMHSA Web site. Updated May 7, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

37. Bowen S, Chawla N, Witkiewitz K. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. In: Baer RA, ed. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: A Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications. London, UK: Elsevier; 2014.

38. Dixon L, McFarlane W, Lefley H, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:903-910.

39. Hayes SC, Levin M, Plumb-Vilardaga J, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44:180-198.

40. Osilla KC, Hepner KA, Muñoz RF, et al. Developing an integrated treatment for substance use and depression using cognitive behavioral therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:412-420.

41. Martino S, Carroll K, Kostas D, et al. Dual diagnosis motivational interviewing: a modification of motivational interviewing for substance-abusing patients with psychotic disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:297-308.

42. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325-334.

43. Garland EL. Disrupting the downward spiral of chronic pain and opioid addiction with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: a review of clinical outcomes and neurocognitive targets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28:122-129.

44. Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:448-459.

45. Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

46. Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, et al. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30:266-294.

THE CASE

Janice J* visits her family physician with complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, and heart palpitations that are usually worse at night. Her medical history is significant for deep vein thrombosis secondary to an underlying hypercoagulability condition (rheumatoid arthritis) diagnosed 2 months earlier. She also has a history of opioid use disorder and has been on buprenorphine/naloxone therapy for 3 years. Her family medical history is unremarkable. She works full-time and lives with her 8-year-old son. On physical exam, she appears anxious; her cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal. A completed workup rules out cardiac or pulmonary problems.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS: SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Co-occurring disorders, previously called “dual diagnosis,” refers to the coexistence of a mental health disorder and a substance use disorder. The obsolete term, dual diagnosis, specified the presence of 2 co-occurring Axis I diagnoses or the presence of an Axis I diagnosis and an Axis II diagnosis (such as mental disability). The change in nomenclature more precisely describes the co-existing mental health and substance use disorders.

Currently the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, (DSM-5) includes no diagnostic criteria for this dual condition.1 The criteria for mental health disorders and for substance use disorders comprise separate lists. Criteria for substance use disorder fall broadly into categories of “impaired [self] control, social impairment, risky behaviors, increased tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms.”1 It is estimated that 8.5 million US adults have co-occurring disorders, per the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.2 Distinguishing which of the 2 conditions occurred first can be challenging. It has been suggested that the lifetime prevalence of a mental health disorder with a coexisting substance use disorder is greater than 40%3,4 (TABLE 11,4-8). For patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, these numbers may be higher.

The consequences of undiagnosed and untreated co-occurring disorders include poor medication adherence, physical comorbidities (and decreased overall health), diminished self-care, increased suicide risk or aggression, increased risky sexual behavior, and possible incarceration.9

WHEN SHOULD YOU SUSPECT CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS?

Diagnosing a second condition can also be difficult when a patient’s symptoms are actually adverse effects of substances or prescribed medications. For example, a patient with worsening anxiety may also exhibit increasing blood pressure resistant to treatment. The cause of the patient’s fluctuating blood pressures may actually be the result of his or her use of alcohol to self-treat the anxiety. In addition to self-medication, other underlying factors may be at play, including genetic vulnerability, environment, and lifestyle.14 In the case we present, the patient’s conditions arose independently.

Anxiety disorders, with a lifetime risk of 28.8% in the US population,4 may be the primary mental health issue in many patients with co-occurring disorders, but this cannot be assumed in lieu of a complete workup.2,8,9,15 Substance use disorders in the general population have a past-year and lifetime prevalence of 14.6%.1,4,16,17 Because the causal and temporal association between anxiety and substance abuse is not always clear, it’s important to separate the diagnoses of the mental health and substance use disorders.

Continue to: MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

To make an accurate diagnosis of co-occurring disorder, it is essential to take a complete history focusing on the timeline of symptoms, previous diagnoses and treatments, if any, and substance-free periods. Details gathered from these inquiries will help to separate symptoms of a primary mental health disorder from adverse effects of medication, withdrawal symptoms, or symptoms related to an underlying chronic medical condition.

Optimally, the diagnosis of a mental health disorder should be considered following a substance-free period. If this is not possible, a chart review may reveal a time when the patient did not have a substance use disorder.18

A diagnosis of substance use disorder requires that the patient manifest at least 2 of 11 behaviors listed in the DSM-5 over a 12-month period.1 The criteria focus on the amount of substance used, the time spent securing the substance, risky behaviors associated with the substance, and tolerance to the substance.

DON'T DEFER MENTAL HEALTH Tx

It is necessary to treat co-occurring disorders simultaneously. The old idea of deferring treatment of a mental health issue until the substance use disorder is resolved no longer applies.19,20 Treating substance use problems without addressing comorbid mental health issues can negatively impact treatment progress and increase risk for relapse. In a similar way, leaving substance use problems untreated is associated with nonadherence in mental health treatment, poor engagement, and dropout.21,22

Integrated services. Due to this condition’s level of clinical complexity, the optimal treatment approach is an interdisciplinary one in which integrated services are offered at a single location by a team of medical, mental health, and substance use providers (see “The case for behavioral health integration into primary care” in the June issue). An evidence-based example of such an approach is the Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) model—a comprehensive, integrated method of treating severe mental health disorders, including substance use disorders.21,22 IDDT combines coordinated services such as pharmacologic, psychological, educational, and social interventions to address the needs of patients and their family members. The IDDT model conceptualizes and treats co-occurring disorders within a biopsychosocial framework. Specific services may include medical detoxification, pharmacotherapy, patient and family education, behavioral and cognitive therapies, contingency management, self-help support groups, supported employment, residential/housing assistance, and case management services.23,24

Continue to: Medications for the mental health component

Medications for the mental health component. For patients who prefer medication treatment to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or for whom CBT is unavailable, treat the mental health disorder per customary practice for the diagnosis (TABLE 225-30). For psychotic disorders, use an antipsychotic, adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) as needed depending on the presence of negative symptoms.25,31 For bipolar spectrum disorder, start a mood stabilizer32; for depressive disorders initiate an SSRI or SNRI.27 Anxiety disorders respond optimally when treated with SSRIs or SNRIs. Buspirone may be prescribed alone or as an adjunct for anxiety, and it does not cause mood-altering or withdrawal effects. Benzodiazepines in a controlled and monitored setting are an option in some antianxiety treatment plans. Consultation with a psychiatrist will help to determine the best treatment in these situations.

In all cases, treat the substance use disorder concurrently. Treatment options vary depending on the substance of choice. Although often overlooked, there can be simultaneous nicotine abuse. Oral or inhaled medications for nicotine abuse treatment are limited. The range of pharmacologic options for alcohol use disorder includes naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.29,33 Pharmacologic treatment options for opioid use disorder include naltrexone, methadone, and a combination of naloxone and buprenorphine.34

Physicians who wish to prescribe buprenorphine must qualify for and complete a certified 8 hour waiver-training course, which is then approved by the Drug Enforcement Agency (under the DATA 2000 – Drug and Alcohol Act 2000). The physician obtains the designation of a data-waived physician and is assigned a special identification number to prescribe these medications.35,36 Methadone may be provided only in a licensed methadone maintenance program. Regular and random drug urine screen requirements apply to all treatment programs.

Psychosocial and behavioral interventions are essential to the successful treatment of co-occurring disorders. Evidence-based behavioral and cognitive therapies are recommended for promoting adaptive coping skills and healthy lifestyle behaviors in co-occurring disorder populations.23,24,37-40 Motivational interviewing enhances motivation and adherence when patients demonstrate resistance or ambivalence.41,42 Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective and may be particularly beneficial for treating cravings/urges and promoting relapse prevention.37,39,40,43-46

Psychotropic medications, as with other treatment components, are most effective when used in combination with services that simultaneously address the patient’s biological, psychological, and social needs.

Continue to: The grassroots organization...

The grassroots organization National Alliance on Mental Illness (www.nami.org) recommends self-help and support groups, which include 12-step, faith-based and non-faith–based programs.20

For any treatment method to be successful, there needs to be a level of customization and individualization. Some patients may respond to medication or nonmedication treatments only, and others may need a combination of treatments.

CASE

The physician recalls a past diagnosis of anxiety and asks Ms. J if there are any new stressors or changes causing concern. The patient expresses concern about an opioid use relapse secondary to her recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, which may be life altering or limiting.

Even though she has been doing well and has been adherent to her daily buprenorphine treatment, she worries for the well-being of her family and what would happen if she cannot work, becomes incapacitated, or dies at a young age. She has never considered herself an anxious person and is surprised that anxiety could cause such pronounced physical symptoms.

The physician discusses different modalities of treatment, including counseling with an onsite psychologist, a trial of an anti-anxiety medication such as sertraline, or return office visits with the physician. They decide first to schedule an appointment with the psychologist, and Ms. J promises to find more time for self-wellness activities, such as exercise.

After 3 months of therapy, the patient decides to space out treatment to every 2 to 3 months and does not report any more episodes of chest pain or shortness of breath.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Northwood-High Building, 2231 N. High Street, Suite 211, Columbus, OH 43201; [email protected].

THE CASE

Janice J* visits her family physician with complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, and heart palpitations that are usually worse at night. Her medical history is significant for deep vein thrombosis secondary to an underlying hypercoagulability condition (rheumatoid arthritis) diagnosed 2 months earlier. She also has a history of opioid use disorder and has been on buprenorphine/naloxone therapy for 3 years. Her family medical history is unremarkable. She works full-time and lives with her 8-year-old son. On physical exam, she appears anxious; her cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal. A completed workup rules out cardiac or pulmonary problems.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS: SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Co-occurring disorders, previously called “dual diagnosis,” refers to the coexistence of a mental health disorder and a substance use disorder. The obsolete term, dual diagnosis, specified the presence of 2 co-occurring Axis I diagnoses or the presence of an Axis I diagnosis and an Axis II diagnosis (such as mental disability). The change in nomenclature more precisely describes the co-existing mental health and substance use disorders.

Currently the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, (DSM-5) includes no diagnostic criteria for this dual condition.1 The criteria for mental health disorders and for substance use disorders comprise separate lists. Criteria for substance use disorder fall broadly into categories of “impaired [self] control, social impairment, risky behaviors, increased tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms.”1 It is estimated that 8.5 million US adults have co-occurring disorders, per the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.2 Distinguishing which of the 2 conditions occurred first can be challenging. It has been suggested that the lifetime prevalence of a mental health disorder with a coexisting substance use disorder is greater than 40%3,4 (TABLE 11,4-8). For patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, these numbers may be higher.

The consequences of undiagnosed and untreated co-occurring disorders include poor medication adherence, physical comorbidities (and decreased overall health), diminished self-care, increased suicide risk or aggression, increased risky sexual behavior, and possible incarceration.9

WHEN SHOULD YOU SUSPECT CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS?

Diagnosing a second condition can also be difficult when a patient’s symptoms are actually adverse effects of substances or prescribed medications. For example, a patient with worsening anxiety may also exhibit increasing blood pressure resistant to treatment. The cause of the patient’s fluctuating blood pressures may actually be the result of his or her use of alcohol to self-treat the anxiety. In addition to self-medication, other underlying factors may be at play, including genetic vulnerability, environment, and lifestyle.14 In the case we present, the patient’s conditions arose independently.

Anxiety disorders, with a lifetime risk of 28.8% in the US population,4 may be the primary mental health issue in many patients with co-occurring disorders, but this cannot be assumed in lieu of a complete workup.2,8,9,15 Substance use disorders in the general population have a past-year and lifetime prevalence of 14.6%.1,4,16,17 Because the causal and temporal association between anxiety and substance abuse is not always clear, it’s important to separate the diagnoses of the mental health and substance use disorders.

Continue to: MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

To make an accurate diagnosis of co-occurring disorder, it is essential to take a complete history focusing on the timeline of symptoms, previous diagnoses and treatments, if any, and substance-free periods. Details gathered from these inquiries will help to separate symptoms of a primary mental health disorder from adverse effects of medication, withdrawal symptoms, or symptoms related to an underlying chronic medical condition.

Optimally, the diagnosis of a mental health disorder should be considered following a substance-free period. If this is not possible, a chart review may reveal a time when the patient did not have a substance use disorder.18

A diagnosis of substance use disorder requires that the patient manifest at least 2 of 11 behaviors listed in the DSM-5 over a 12-month period.1 The criteria focus on the amount of substance used, the time spent securing the substance, risky behaviors associated with the substance, and tolerance to the substance.

DON'T DEFER MENTAL HEALTH Tx

It is necessary to treat co-occurring disorders simultaneously. The old idea of deferring treatment of a mental health issue until the substance use disorder is resolved no longer applies.19,20 Treating substance use problems without addressing comorbid mental health issues can negatively impact treatment progress and increase risk for relapse. In a similar way, leaving substance use problems untreated is associated with nonadherence in mental health treatment, poor engagement, and dropout.21,22

Integrated services. Due to this condition’s level of clinical complexity, the optimal treatment approach is an interdisciplinary one in which integrated services are offered at a single location by a team of medical, mental health, and substance use providers (see “The case for behavioral health integration into primary care” in the June issue). An evidence-based example of such an approach is the Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) model—a comprehensive, integrated method of treating severe mental health disorders, including substance use disorders.21,22 IDDT combines coordinated services such as pharmacologic, psychological, educational, and social interventions to address the needs of patients and their family members. The IDDT model conceptualizes and treats co-occurring disorders within a biopsychosocial framework. Specific services may include medical detoxification, pharmacotherapy, patient and family education, behavioral and cognitive therapies, contingency management, self-help support groups, supported employment, residential/housing assistance, and case management services.23,24

Continue to: Medications for the mental health component

Medications for the mental health component. For patients who prefer medication treatment to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or for whom CBT is unavailable, treat the mental health disorder per customary practice for the diagnosis (TABLE 225-30). For psychotic disorders, use an antipsychotic, adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) as needed depending on the presence of negative symptoms.25,31 For bipolar spectrum disorder, start a mood stabilizer32; for depressive disorders initiate an SSRI or SNRI.27 Anxiety disorders respond optimally when treated with SSRIs or SNRIs. Buspirone may be prescribed alone or as an adjunct for anxiety, and it does not cause mood-altering or withdrawal effects. Benzodiazepines in a controlled and monitored setting are an option in some antianxiety treatment plans. Consultation with a psychiatrist will help to determine the best treatment in these situations.

In all cases, treat the substance use disorder concurrently. Treatment options vary depending on the substance of choice. Although often overlooked, there can be simultaneous nicotine abuse. Oral or inhaled medications for nicotine abuse treatment are limited. The range of pharmacologic options for alcohol use disorder includes naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.29,33 Pharmacologic treatment options for opioid use disorder include naltrexone, methadone, and a combination of naloxone and buprenorphine.34

Physicians who wish to prescribe buprenorphine must qualify for and complete a certified 8 hour waiver-training course, which is then approved by the Drug Enforcement Agency (under the DATA 2000 – Drug and Alcohol Act 2000). The physician obtains the designation of a data-waived physician and is assigned a special identification number to prescribe these medications.35,36 Methadone may be provided only in a licensed methadone maintenance program. Regular and random drug urine screen requirements apply to all treatment programs.

Psychosocial and behavioral interventions are essential to the successful treatment of co-occurring disorders. Evidence-based behavioral and cognitive therapies are recommended for promoting adaptive coping skills and healthy lifestyle behaviors in co-occurring disorder populations.23,24,37-40 Motivational interviewing enhances motivation and adherence when patients demonstrate resistance or ambivalence.41,42 Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective and may be particularly beneficial for treating cravings/urges and promoting relapse prevention.37,39,40,43-46

Psychotropic medications, as with other treatment components, are most effective when used in combination with services that simultaneously address the patient’s biological, psychological, and social needs.

Continue to: The grassroots organization...

The grassroots organization National Alliance on Mental Illness (www.nami.org) recommends self-help and support groups, which include 12-step, faith-based and non-faith–based programs.20

For any treatment method to be successful, there needs to be a level of customization and individualization. Some patients may respond to medication or nonmedication treatments only, and others may need a combination of treatments.

CASE

The physician recalls a past diagnosis of anxiety and asks Ms. J if there are any new stressors or changes causing concern. The patient expresses concern about an opioid use relapse secondary to her recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, which may be life altering or limiting.

Even though she has been doing well and has been adherent to her daily buprenorphine treatment, she worries for the well-being of her family and what would happen if she cannot work, becomes incapacitated, or dies at a young age. She has never considered herself an anxious person and is surprised that anxiety could cause such pronounced physical symptoms.

The physician discusses different modalities of treatment, including counseling with an onsite psychologist, a trial of an anti-anxiety medication such as sertraline, or return office visits with the physician. They decide first to schedule an appointment with the psychologist, and Ms. J promises to find more time for self-wellness activities, such as exercise.

After 3 months of therapy, the patient decides to space out treatment to every 2 to 3 months and does not report any more episodes of chest pain or shortness of breath.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Northwood-High Building, 2231 N. High Street, Suite 211, Columbus, OH 43201; [email protected].

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013.

2. SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm#cooccur2. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, et al. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247-257.

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

5. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

6. Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(suppl):S93-S100.

7. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241-251.

8. Cottler LB, Compton WM 3rd, Mager D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:664-670.

9. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168-176.

10. Burns L, Teesson M, O’Neill K. The impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on alcohol treatment outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100:787-796.

11. Magidson JF, Liu SM, Lejuez CW, et al. Comparison of the course of substance use disorders among individuals with and without generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:659666.

12. Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, et al. Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:476-484.

13. Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):76-88.

14. Buckley PF. Prevalence and consequences of the dual diagnosis of substance abuse and severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):5-9.

15. Salo R, Flower K, Kielstein A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in methamphetamine dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:356-361.

16. Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:147-156.

17. Buckner JD, Timpano KR, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:1028-1037.

18. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149-171.

19. McHugh RK. Treatment of co-occurring anxiety disorders and substance use disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:99-111.

20. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. NAMI Web site. www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/related-conditions/dual-diagnosis. Reviewed August 2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

21. SAMSHA. Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series No. 42. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-3992. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.

22. SAMHSA. Treatment of co-occurring disorders. In: Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005.

23. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:360-374.

24. Kola LA, Kruszynski R. Adapting the integrated dual-disorder treatment model for addiction services. Alcohol Treat Q. 2010;28:437-450.

25. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

27. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 23, 2019.

28. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed August 2, 2019.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969. Accessed August 2, 2019.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/substanceuse.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

31. Petrakis IL, Nich C, Ralevski E. Psychotic spectrum disorders and alcohol abuse: a review of pharmacotherapeutic strategies and a report on the effectiveness of naltrexone and disulfiram. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:644-654.

32. McIntyre RS, Yoon J. Efficacy of antimanic treatments in mixed states. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(suppl 2):22-36.

33. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876-880.

34. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:309-318.

35. US Department of Justice. DEA requirements for DATA waived physicians (DWPs). Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division Web site. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/docs/dwp_buprenorphine.htm. Accessed August 2, 2019.

36. SAMHSA. Buprenorphine waiver management. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/buprenorphine-waiver-management. SAMHSA Web site. Updated May 7, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

37. Bowen S, Chawla N, Witkiewitz K. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. In: Baer RA, ed. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: A Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications. London, UK: Elsevier; 2014.

38. Dixon L, McFarlane W, Lefley H, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:903-910.

39. Hayes SC, Levin M, Plumb-Vilardaga J, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44:180-198.

40. Osilla KC, Hepner KA, Muñoz RF, et al. Developing an integrated treatment for substance use and depression using cognitive behavioral therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:412-420.

41. Martino S, Carroll K, Kostas D, et al. Dual diagnosis motivational interviewing: a modification of motivational interviewing for substance-abusing patients with psychotic disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:297-308.

42. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325-334.

43. Garland EL. Disrupting the downward spiral of chronic pain and opioid addiction with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: a review of clinical outcomes and neurocognitive targets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28:122-129.

44. Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:448-459.

45. Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

46. Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, et al. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30:266-294.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013.

2. SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm#cooccur2. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, et al. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247-257.

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

5. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

6. Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(suppl):S93-S100.

7. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241-251.

8. Cottler LB, Compton WM 3rd, Mager D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:664-670.

9. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168-176.

10. Burns L, Teesson M, O’Neill K. The impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on alcohol treatment outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100:787-796.

11. Magidson JF, Liu SM, Lejuez CW, et al. Comparison of the course of substance use disorders among individuals with and without generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:659666.

12. Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, et al. Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:476-484.

13. Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):76-88.

14. Buckley PF. Prevalence and consequences of the dual diagnosis of substance abuse and severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):5-9.

15. Salo R, Flower K, Kielstein A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in methamphetamine dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:356-361.

16. Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:147-156.

17. Buckner JD, Timpano KR, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:1028-1037.

18. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149-171.

19. McHugh RK. Treatment of co-occurring anxiety disorders and substance use disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:99-111.

20. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. NAMI Web site. www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/related-conditions/dual-diagnosis. Reviewed August 2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

21. SAMSHA. Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series No. 42. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-3992. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.

22. SAMHSA. Treatment of co-occurring disorders. In: Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005.

23. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:360-374.

24. Kola LA, Kruszynski R. Adapting the integrated dual-disorder treatment model for addiction services. Alcohol Treat Q. 2010;28:437-450.

25. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

27. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 23, 2019.

28. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed August 2, 2019.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969. Accessed August 2, 2019.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders, 2nd ed. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/substanceuse.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed August 2, 2019.

31. Petrakis IL, Nich C, Ralevski E. Psychotic spectrum disorders and alcohol abuse: a review of pharmacotherapeutic strategies and a report on the effectiveness of naltrexone and disulfiram. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:644-654.

32. McIntyre RS, Yoon J. Efficacy of antimanic treatments in mixed states. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(suppl 2):22-36.

33. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876-880.

34. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:309-318.

35. US Department of Justice. DEA requirements for DATA waived physicians (DWPs). Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division Web site. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/docs/dwp_buprenorphine.htm. Accessed August 2, 2019.

36. SAMHSA. Buprenorphine waiver management. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/buprenorphine-waiver-management. SAMHSA Web site. Updated May 7, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

37. Bowen S, Chawla N, Witkiewitz K. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. In: Baer RA, ed. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: A Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications. London, UK: Elsevier; 2014.

38. Dixon L, McFarlane W, Lefley H, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:903-910.

39. Hayes SC, Levin M, Plumb-Vilardaga J, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44:180-198.

40. Osilla KC, Hepner KA, Muñoz RF, et al. Developing an integrated treatment for substance use and depression using cognitive behavioral therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:412-420.

41. Martino S, Carroll K, Kostas D, et al. Dual diagnosis motivational interviewing: a modification of motivational interviewing for substance-abusing patients with psychotic disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:297-308.

42. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325-334.

43. Garland EL. Disrupting the downward spiral of chronic pain and opioid addiction with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: a review of clinical outcomes and neurocognitive targets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28:122-129.

44. Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:448-459.

45. Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

46. Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, et al. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30:266-294.

The case for behavioral health integration into primary care

In a typical primary care practice, detecting and managing mental health problems competes with other priorities such as treating acute physical illness, monitoring chronic disease, providing preventive health services, and assessing compliance with standards of care.1 These competing demands for a primary care provider’s time, paired with limited mental health resources in the community, may result in suboptimal behavioral health care.1-3 Even when referrals are made to

Approximately 30% of adults with physical disorders also have one or more behavioral health conditions, such as anxiety, panic, mood, or substance use disorders.6 Although physical and behavioral health conditions are inextricably linked, their assessment and treatment get separated into different silos.7 Given that fewer than 20% of depressed patients are seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist,8 the responsibility of providing mental health care often falls on the primary care physician.8,9

Efforts to improve the treatment of common mental disorders in primary care have traditionally focused on screening for these disorders, educating primary care providers, developing treatment guidelines, and referring patients to mental health specialty care.10 However, behavioral health integration offers another way forward.

WHAT IS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION?

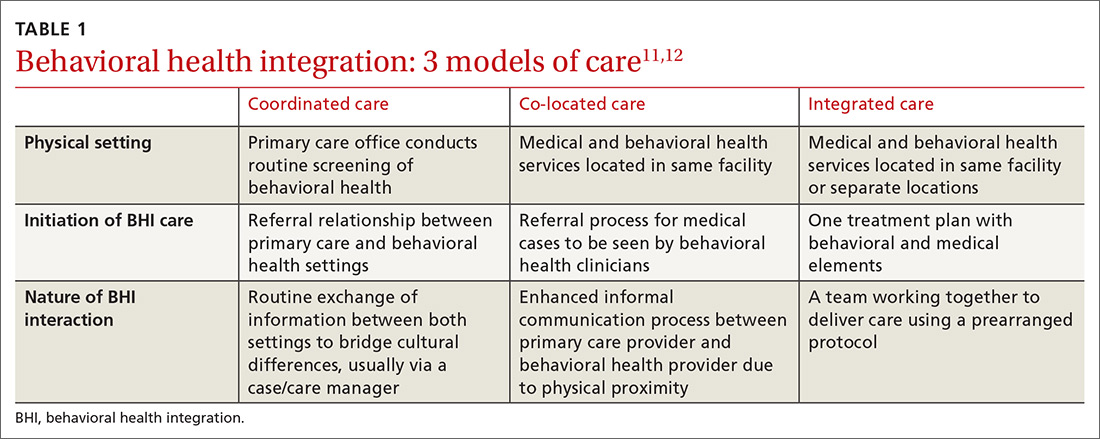

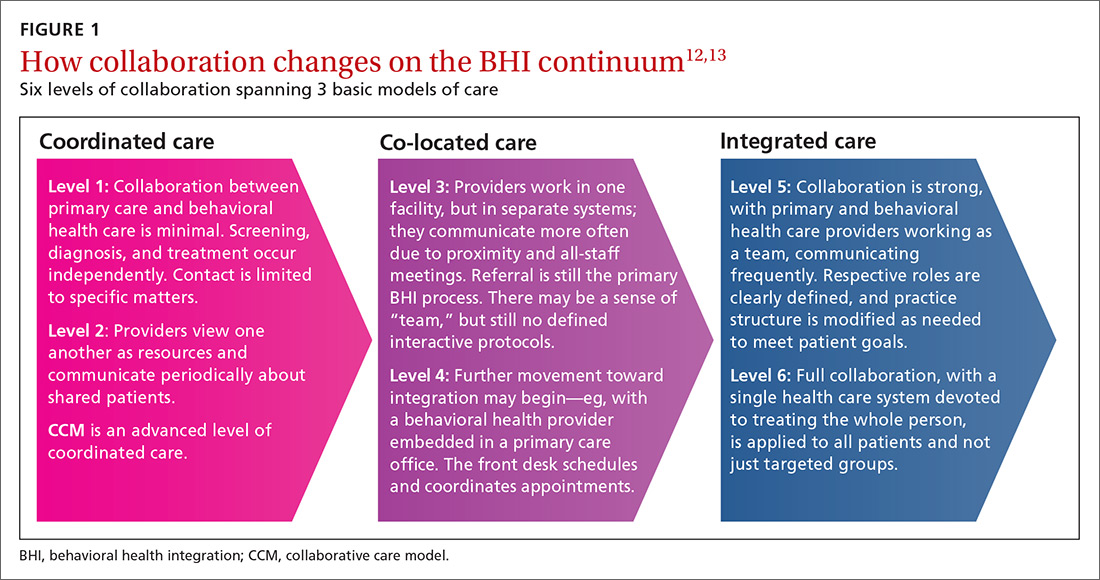

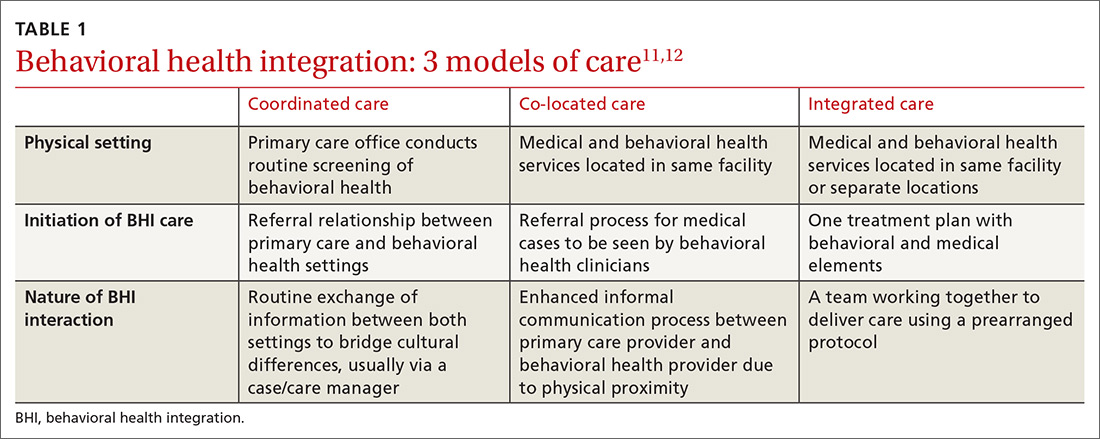

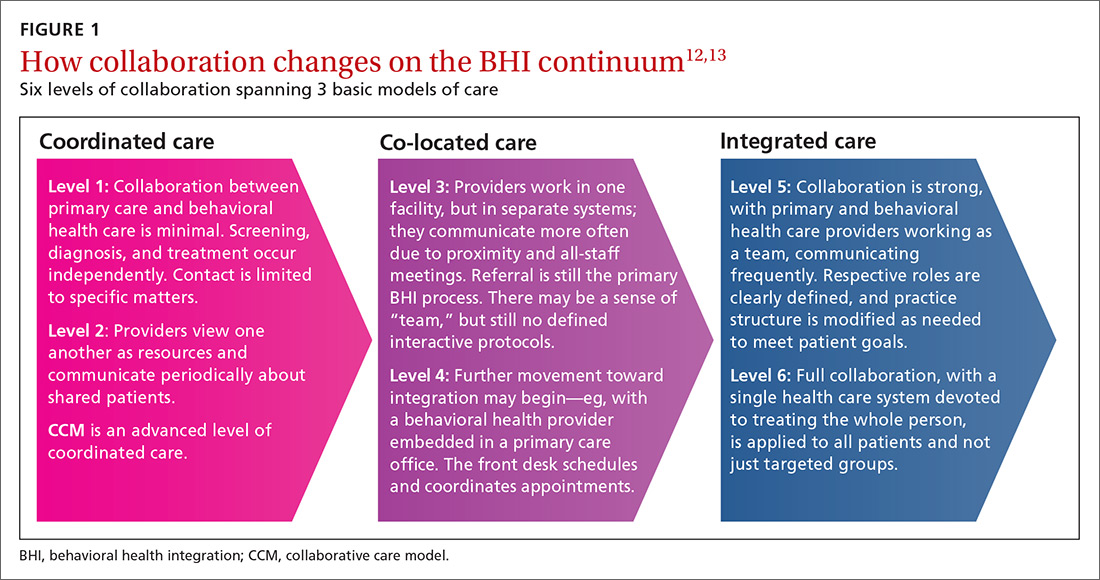

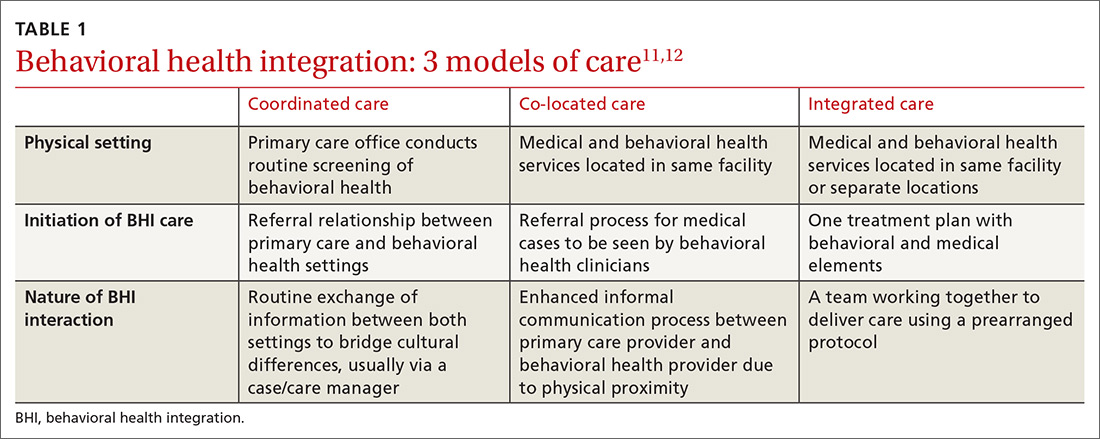

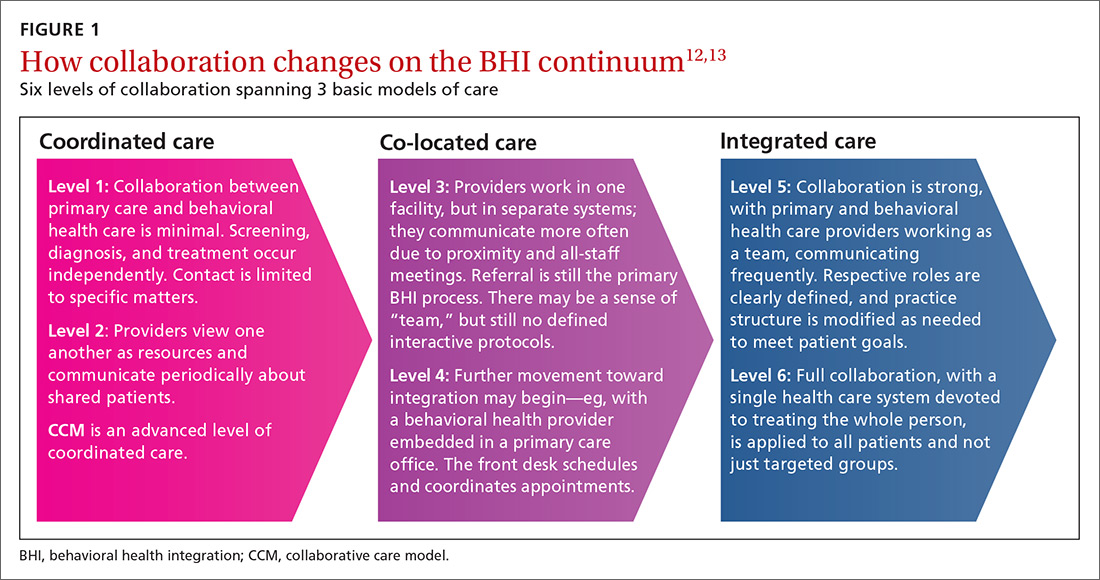

Behavioral health integration (BHI) in primary care refers to primary care physicians and behavioral health clinicians working in concert with patients to address their primary care and behavioral health needs.11

Numerous overlapping terms have been used to describe BHI, and this has caused some confusion. In 2013, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) issued a lexicon standardizing the terminology used in BHI.11 The commonly used terms are

COORDINATED CARE AND THE COLLABORATIVE CARE MODEL

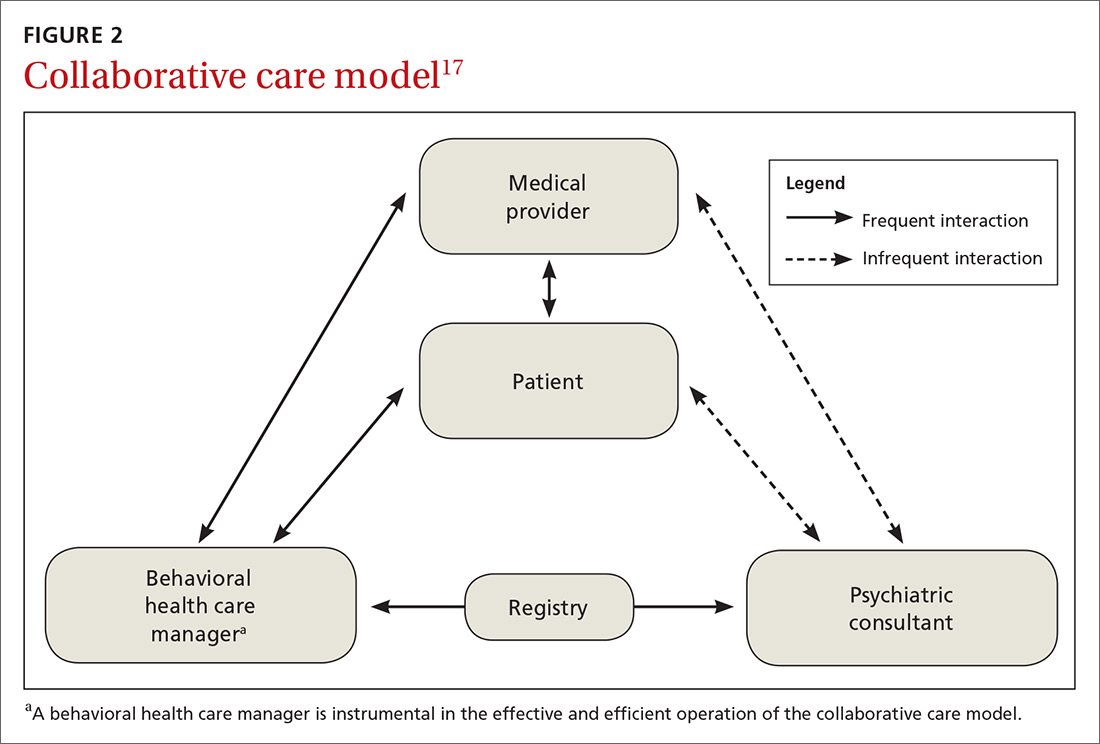

BHI at the level of coordinated care has almost exclusively been studied and practiced along the lines of the collaborative care model (CCM).14-16 This model represents an advanced level of coordinated care in the BHI continuum. The most substantial evidence for CCM lies in the management of depression and anxiety.14-16

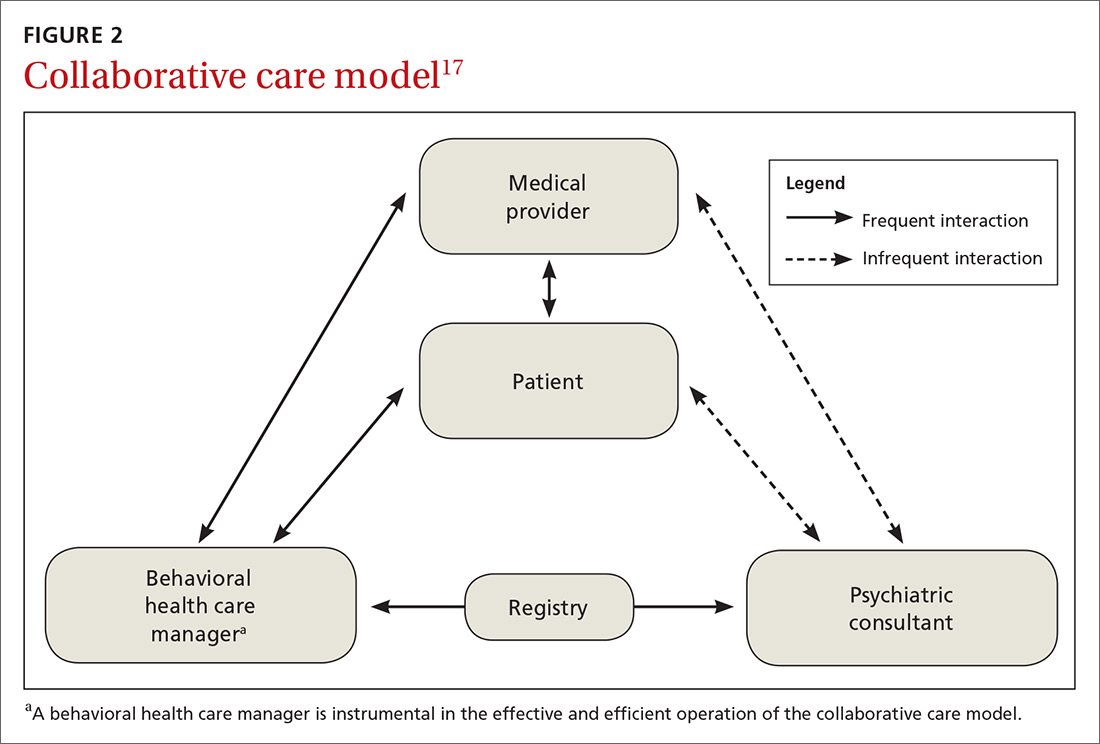

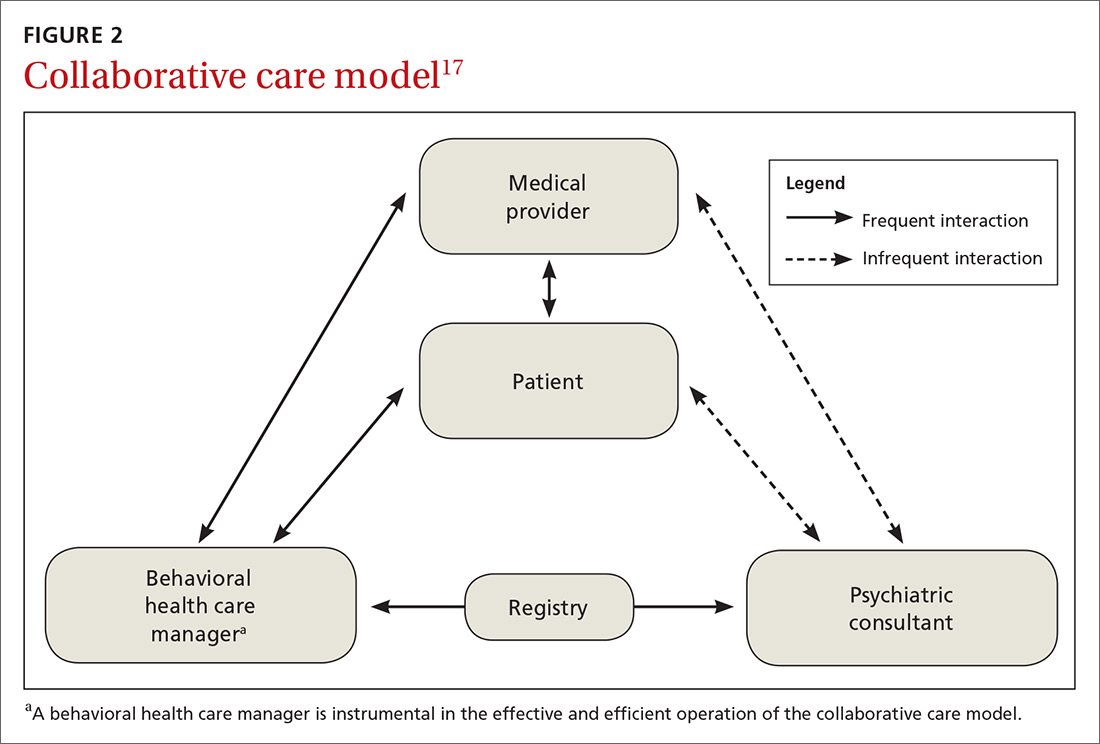

Usual care involves the primary care physician and the patient. CCM adds 2 vital roles—a behavioral health care manager and a psychiatric consultant. A behavioral health care manager is typically a counselor, clinical social worker, psychologist, or psychiatric nurse who performs all care-management tasks including offering psychotherapy when that is part of the treatment plan.

Continue to: The care manager's functions include...

The care manager’s functions include systematic follow-up with structured monitoring of symptoms and treatment adherence, coordination and communication among care providers, patient education, and self-management support, including the use of motivational interviewing. The behavioral health care manager performs this systematic follow up by maintaining a patient “registry”—case-management software used in conjunction with, or embedded in, the practice electronic health record to track patients’ data and clinical outcomes, as well as to facilitate decision-making.

The care manager communicates with the psychiatrist, who offers suggestions for drug therapy, which is prescribed by the primary care physician. The care manager also regularly evaluates the patient’s status using a standardized scale, communicates these scores to the psychiatrist, and transmits any recommendations to the primary care physician (FIGURE 2).17

EVIDENCE FOR CCM

Collaborative and routine care were compared in a 2012 Cochrane review that included 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 24,308 patients worldwide.16 Seventy-two of the 79 RCTs focused on patients with depression or depression with anxiety, while 6 studies included participants with only anxiety disorders.16 One additional study focused on mental health quality of life. (To learn about CCM and severe mental illness and substance use disorder, see “Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence.”18-20)

SIDEBAR

Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence

Evidence for collaborative care in severe mental illness (SMI) is very limited. SMI is defined as schizophrenia or other schizophrenia-like psychoses (eg, schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), bipolar affective disorder, or other psychosis.

A 2013 Cochrane review identified only 1 RCT involving 306 veterans with bipolar disease.18 The review concluded that there was low-quality evidence that collaborative care led to a relative risk reduction of 25% for psychiatric admissions at Year 2 compared with standard care (RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.99).18

One 2017 RCT involving 245 veterans that looked at a collaborative care model for patients with severe mental illness found a modest benefit for physical health-related quality of life, but did not find any benefit in mental health outcomes.19

Alcohol dependence. There is very limited, but high-quality, evidence for the utility of CCM in alcohol dependence. In one RCT, 163 veterans were assigned to either CCM or referral to standard treatment in a specialty outpatient addiction treatment program. The CCM group had a significantly higher proportion of participants engaged in treatment over the study’s 26 weeks (odds ratio [OR] = 5.36; 95% CI, 2.99-9.59). The percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly lower in the CCM group (OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 1.27-3.66), while overall abstinence did not differ between groups.20

For adults with depression treated with the CCM, significantly greater improvement in depression outcome measures was seen in the short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] = -0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.41 to -0.27; risk ratio [RR] = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.22-1.43), in the medium term (SMD = -0.28; 95% CI, -0.41 to -0.15; RR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17–1.48), and in the long term (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI, -0.46 to -0.24; RR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18–1.41).16

Comparisons of mental health quality of life over the short term (0-6 months), medium term (7-12 months), and long term (13-24 months) did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16 Comparisons of physical health quality of life over the short term and medium term did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16

Continue to: Significantly greater improvement...

Significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes was seen for adults treated with CCM in the short term (SMD = -0.30; 95% CI, -0.44 to -0.17; RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.21–1.87), in the medium term (SMD = -0.33; 95% CI, -0.47 to -0.19; RR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18-1.69), and in the long term (SMD = -0.20; 95% CI, -0.34 to -0.06; RR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42).16

A 2016 systematic review of 94 RCTs involving more than 25,000 patients also provided high-quality evidence that collaborative care yields small-to-moderate improvements in symptoms from mood disorders and mental health-related quality of life.15 A 2006 meta-analysis of 37 RCTs comprising 12,355 patients showed that collaborative care involving a case manager is more effective than standard care in improving depression outcomes at 6 months (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.32) and up to 5 years (SMD = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.001-0.31).21

Better care of mental health disorders also improves medical outcomes

Several trials have focused on jointly managing depression and a chronic physical condition such as chronic pain, diabetes, and coronary heart disease,22 demonstrating improved outcomes for both depression and the comanaged conditions.

- Chronic pain. When compared with usual care, collaborative care resulted in moderate reductions in both pain severity and associated disability (41.5% vs 17.3%; RR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6-3.2).23

- Diabetes. Patients managed collaboratively were more likely to have a decrease of ≥ 1% in the glycated hemoglobin level from baseline (36% vs 19%; P = .006).24

- Cardiovascular disease. Significant real-world risk reduction was achieved by improving blood pressure control (58% achieved blood pressure control compared with a projected target of 20%).22

IS THERE A COMMON THREAD AMONG SUCCESSFUL CCMs?

Attempts to identify commonalities between the many iterations of successful CCMs have produced varying results due to differing selections of relevant RCTs.25-29 However, a few common features have been identified:

- care managers assess symptoms at baseline and at follow-up using a standardized measure such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);

- care managers monitor treatment adherence;

- follow-up is active for at least 16 weeks;

- primary care and mental health providers actively engage in patient management; and

- mental health specialists regularly supervise care managers.

The one feature that is consistent with improved outcomes is the presence of the care manager.25-29

Continue to: The improvement associated...

The improvement associated with collaborative care is clinically meaningful to patients and physicians. In one RCT, collaborative care doubled response rates of depression treatment compared with usual care.3 Quality improvement data from real-world implementation of collaborative care programs suggests that similar outcomes can be achieved in a variety of settings.30

COST BENEFITS OF CCM

Collaborative care for depression is associated with lower health care costs.29,31

A meta-analysis of 57 RCTs in 2012 showed that CCM improves depression outcomes across populations, settings, and outcome domains, and that these results are achieved at little to no increase in treatment costs compared with usual care (Cohen’s d = 0.05; 95% CI, –0.02–0.12).26

When collaborative care was compared with routine care in an RCT involving 1801 primary care patients ≥ 60 years who were suffering from depression, a cost saving of $3363 per patient over 4 years was demonstrated in the intervention arm.31

A technical analysis of 94 RCTs in 2015 concluded that CCM is cost effective compared with usual care, with a range of $15,000 to $80,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained. These studies also indicated that organizations’ costs to implement CCM increase in the short term. Based on this analysis, organizations would need to invest between $3 to $22 per patient per month to implement and sustain CCMs, depending on the prevalence of depression in the population.29

Continue to: OTHER MODELS OF BHI

OTHER MODELS OF BHI

Higher levels of BHI such as co-location and integration do not have the same quality of evidence as CCM.

A 2009 Cochrane review of 42 studies involving 3880 patients found that mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care settings brought about significant reductions in primary care physician consultations (SMD = ‐0.17; 95% CI, ‐0.30 to ‐0.05); a relative risk reduction of 23% in psychotropic prescribing (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56–0.79); a decrease in prescribing costs (SMD = ‐0.22; 95% CI, ‐0.38 to ‐0.07); and a relative risk reduction in mental health referral of 87% (RR = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09–0.20) for the patients they were seeing.32 The authors concluded the changes were modest in magnitude and inconsistent across different studies.32

Embedding medical providers in behavior health centers—ie, the reverse co-location model—also has very limited evidence. An RCT involving 120 veterans found that patients enrolled in a reverse co-location clinic did significantly better than controls seen in a general care clinic in terms of continuity of care and preventive care such as screening for hypertension (84.7% vs 65.6%; X 2 = 5.9, P = .01), diabetes (71.2% vs 45.9%; X 2 = 7.9, P < .005), hepatitis (39% vs 14.8%; X 2 = 9, P = .003), and cholesterol (79.7% vs 57.4%; X 2 = 6.9, P = .009).33

HOW TO IMPLEMENT A SUCCESSFUL BHI PROGRAM

A demonstration and evaluation project involving 11 diverse practices in Colorado explored ways to integrate behavioral health in primary care. Five main themes emerged34,35:

- Frame integrated care as a necessary paradigm shift to patient-centered, whole-person health care.

- Define relationships and protocols up front, understanding that they will evolve.

- Build inclusive, empowered teams to provide the foundation for integration.

- Develop a change management strategy of continuous evaluation and course correction.

- Use targeted data collection pertinent to integrated care to drive improvement and impart accountability.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review has organized an extensive list of resources36 for implementing BHI models, a sampling of which is shown in TABLE 2.

Continue to: TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

There is high quality evidence that collaborative care works for the management of depression and anxiety disorder in primary care, and this is associated with significant cost savings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (FNU) Rajesh, MD, Main Campus Family Medicine Clinic, MetroHealth, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected]

1. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:150-154.

2. Rush A, Trivedi M, Carmody T, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:46-53.

3. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Bradford DW, Slubicki MN, McDuffie J, et al. Effects of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness. 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/smi-REPORT.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. Druss BG, von Esenwein S. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:145-153.

6. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental Disorders and Medical Comorbidity. Research Synthesis Report No. 21. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; February 2011.

7. Reed SJ, Shore KK, Tice JA. Effectiveness and value of integrating behavioral health into primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:691-692.

8. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55-61.

9. Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38632/. Accessed March 2, 2019.

10. Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss B, et al. Transforming mental health care at the interface with general medicine: report for the presidents commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:37-47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37.

11. Peek CJ; the National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. AHRQ. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

12. Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare and update throughout the document. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/A_Standard_Framework_for_Levels_of_Integrated_Healthcare.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

13. Integrating physical and behavioral health care: promising Medicaid models. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/8553-integrating-physical-and-behavioral-health-care-promising-medicaid-models.pdf. Published February 2014. Accessed May 29, 2019.

14. Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: the collaborative care model. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

15. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

16. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10.1002/14651858.cd006525.pub2.

17. Team Structure. University of Washington AIMs Center. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure. Published 2017.Accessed May 29, 2019.

18. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

19. Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, et al. Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:129-137.

20. Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto HSA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29:162-168.

21. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314-2321.

22. Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Magnan S, et al. Impact of a national collaborative care initiative for patients with depression and diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;15:77-85.