User login

Difficult patient, or something else? A review of personality disorders

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

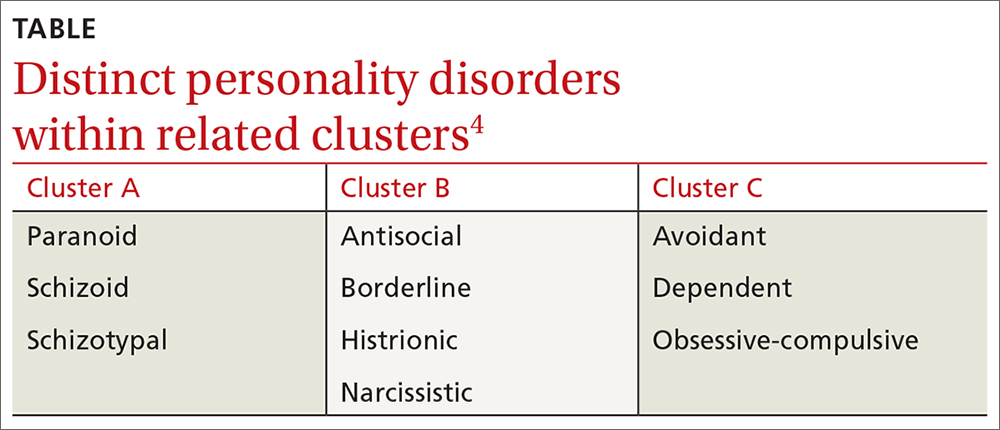

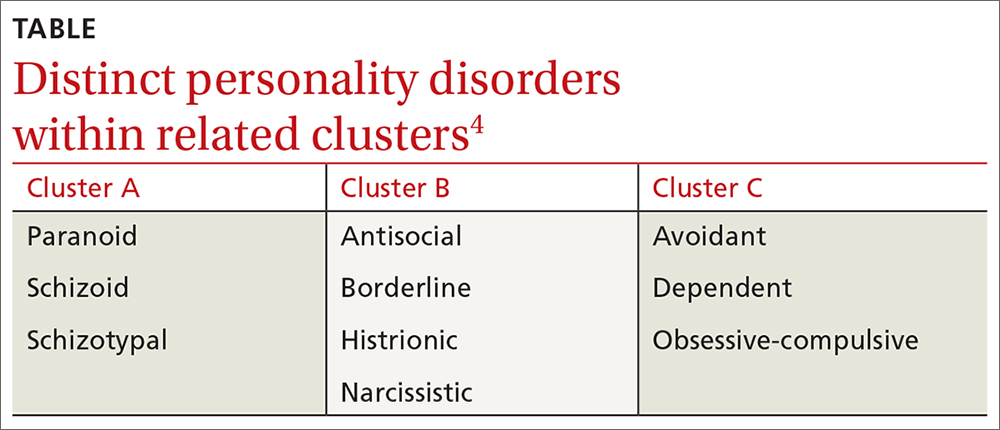

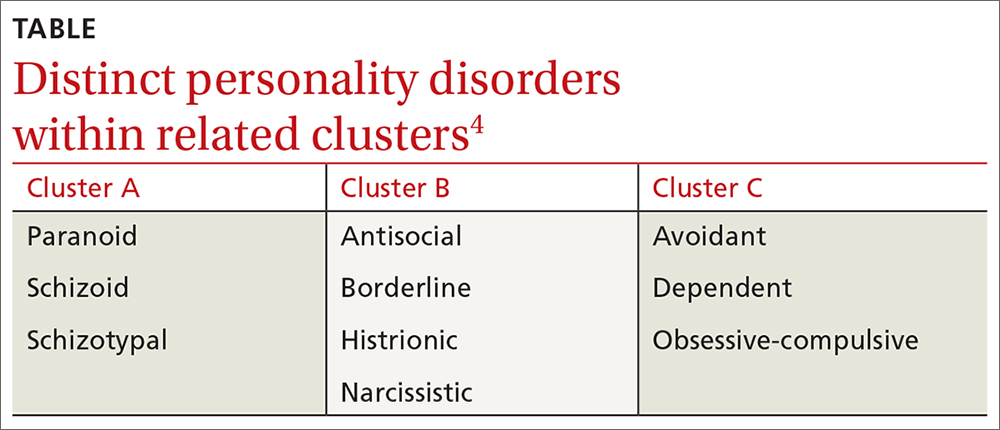

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

Alcohol use disorder: How best to screen and intervene

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and often untreated condition that is increasingly prevalent in the United States.1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) characterizes AUD as a combination of signs and symptoms typifying alcohol abuse and dependence (discussed in a bit).2

Data from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showed 15.7 million Americans with AUD, affecting 6.2% of the population ages 18 years or older and 2.5% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 years.3

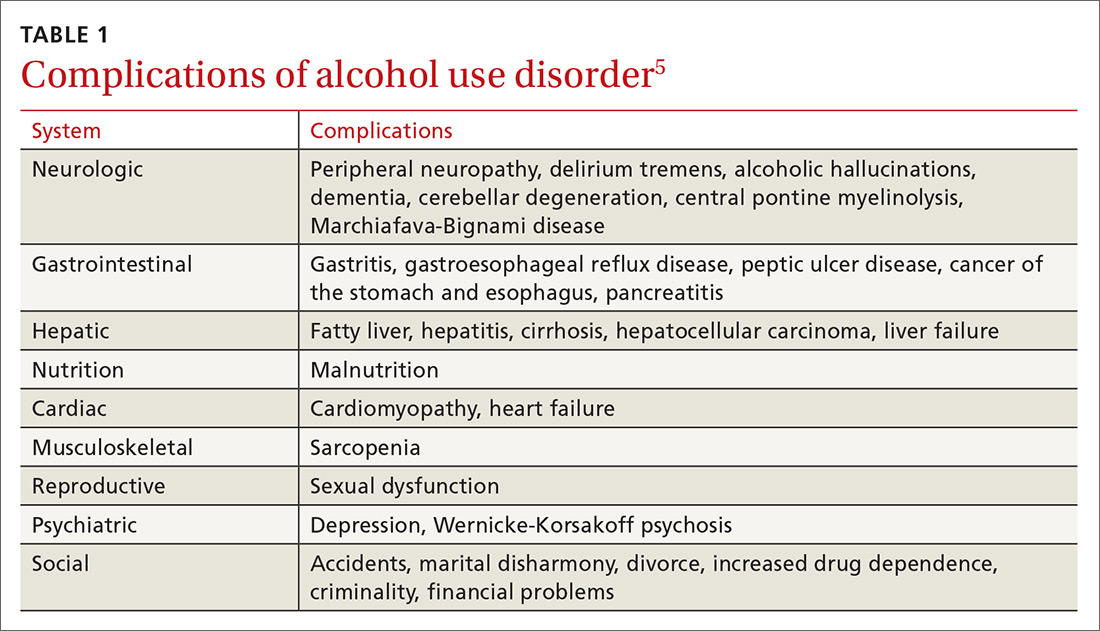

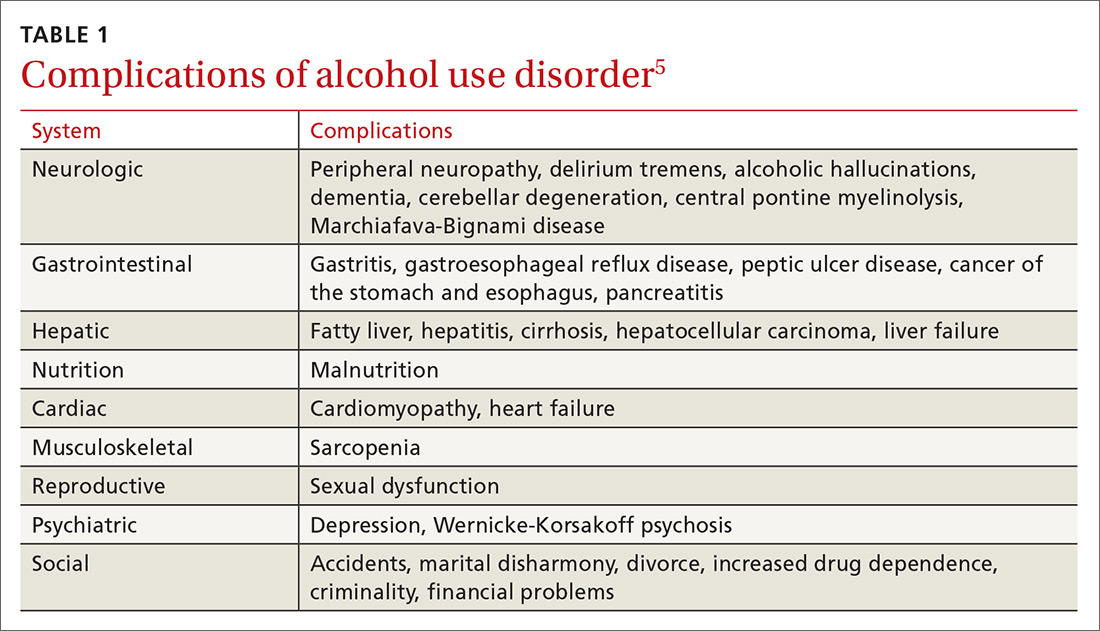

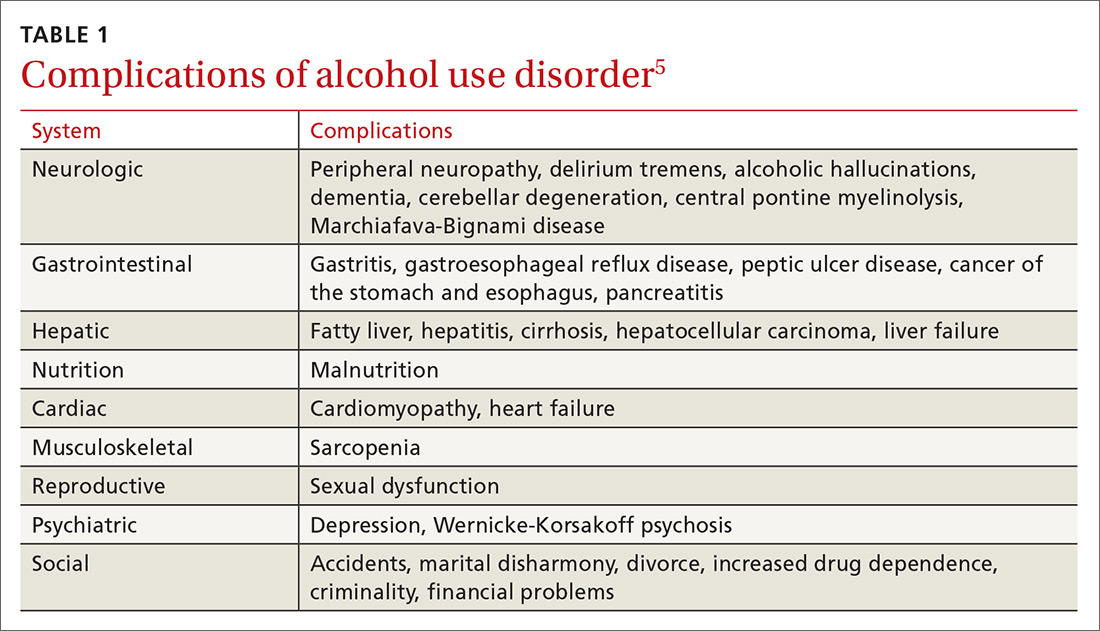

Alcohol use and AUD account for an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life years.4 AUD adversely affects several systems (TABLE 15), and patients with AUD are sicker and more likely to die younger than those without AUD.4 In the United States, prevalence of AUD has increased in recent years among women, older adults, racial minorities, and individuals with a low education level.6

Screening for AUD is reasonable and straightforward, although diagnosis and treatment of AUD in primary care settings may be challenging due to competing clinical priorities; lack of training, resources, and support; and skepticism about the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments.7,8 However, family physicians are in an excellent position to diagnose and help address the complex biopsychosocial needs of patients with AUD, often in collaboration with colleagues and community organizations.

Signs and symptoms of AUD

In clinical practice, at least 2 of the following 11 behaviors or symptoms are required to diagnose AUD2:

- consuming larger amounts of alcohol over a longer period than intended

- persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use

- making a significant effort to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol

In moderate-to-severe cases:

- cravings or urges to use alcohol

- recurrent failure to fulfill major work, school, or social obligations

- continued alcohol use despite recurrent social and interpersonal problems

- giving up social, occupational, and recreational activities due to alcohol

- using alcohol in physically dangerous situations

- continued alcohol use despite having physical or psychological problems

- tolerance to alcohol’s effects

- withdrawal symptoms.

Continue to: Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if...

Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if they exhibit 2 or 3 symptoms, moderate AUD with 4 or 5 symptoms, and severe AUD if there are 6 or more symptoms.2

Those who meet criteria for AUD and are able to stop using alcohol are deemed to be in early remission if the criteria have gone unfulfilled for at least 3 months and less than 12 months. Patients are considered to be in sustained remission if they have not met criteria for AUD at any time during a period of 12 months or longer.

How to detect AUD

Several clues in a patient’s history can suggest AUD (TABLE 29,10). Most imbibers are unaware of the dangers and may consider themselves merely “social drinkers.” Binge drinking may be an early indicator of vulnerability to AUD and should be assessed as part of a thorough clinical evaluation.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) that clinicians screen adults ages 18 years or older for alcohol misuse.12

Studies demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the development of AUD.13 A family history of excessive alcohol use increases the risk of AUD. Comorbidity of AUD and other mental health conditions is extremely common. For example, high rates of association between major depressive disorder and AUD have been observed.14

Tools to use in screening and diagnosing AUD

Screening for AUD during an office visit can be done fairly quickly. While 96% of primary care physicians screen for alcohol misuse in some way, only 38% use 1 of the 3 tools recommended by the USPSTF15—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the abbreviated AUDIT-C, or the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) single question screen—which detect the full spectrum of alcohol misuse in adults.12 Although the commonly used CAGE questionnaire is one of the most studied self-report tools, it has lower sensitivity at a lower level of alcohol intake.16

Continue to: The NIAAA single-question screen asks...

The NIAAA single-question screen asks how many times in the past year the patient had ≥4 drinks (women) or ≥5 drinks (men) in a day.15 The sensitivity and specificity of single-question screening are 82% to 87% and 61% to 79%, respectively, and the test has been validated in several different settings.12 The AUDIT screening tool, freely available from the World Health Organization, is a 10-item questionnaire that probes an individual’s alcohol intake, alcohol dependence, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. Administration of the AUDIT typically requires only 2 minutes. AUDIT-C17 is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT questionnaire that asks 3 consumption questions to screen for AUD.

It was found that AUDIT scores in the range of 8 to 15 indicate a medium-level alcohol problem, whereas a score of ≥16 indicates a high-level alcohol problem. The AUDIT-C is scored from 0 to 12, with ≥4 indicating a problem in men and ≥3

THE CASE

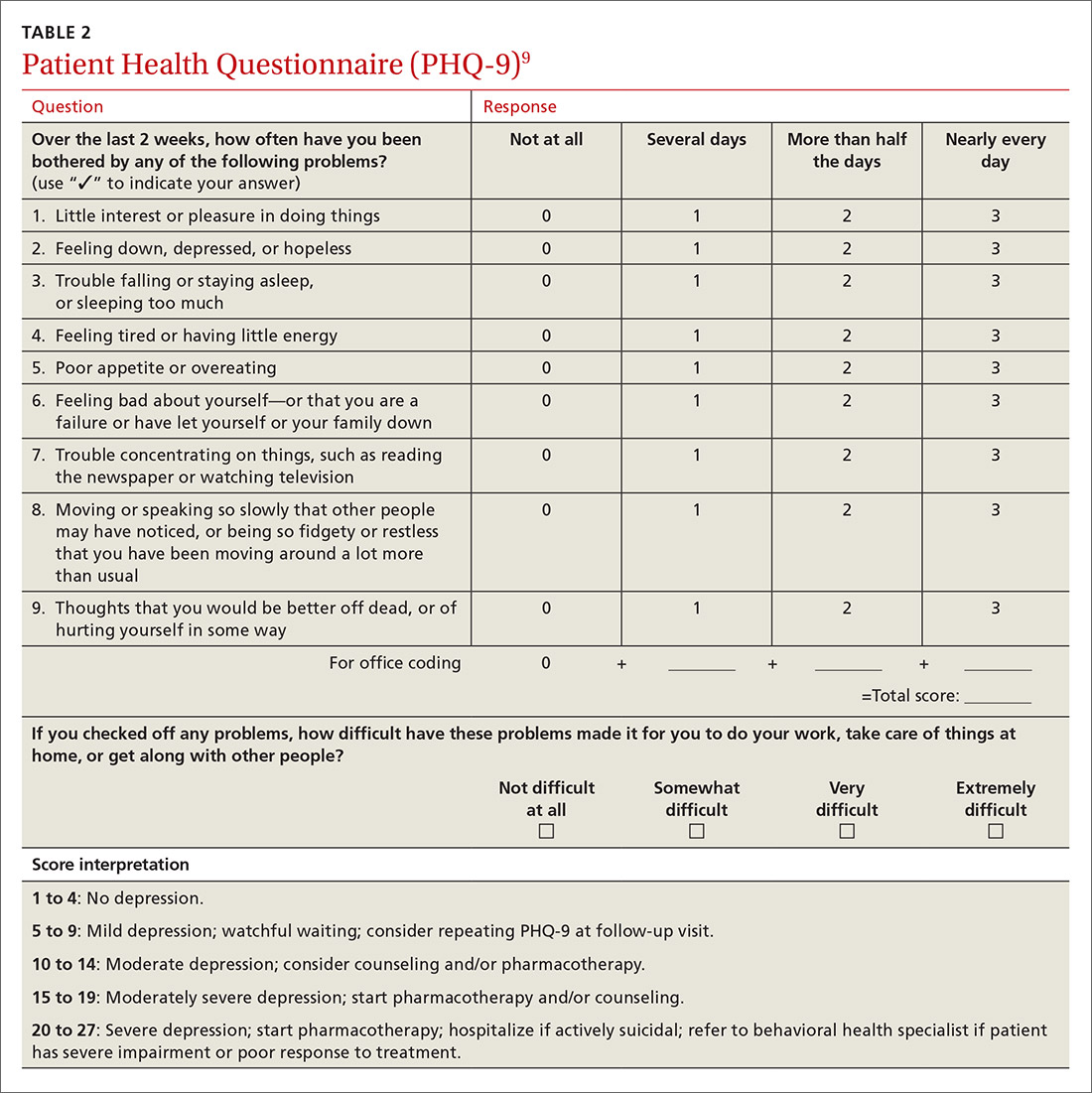

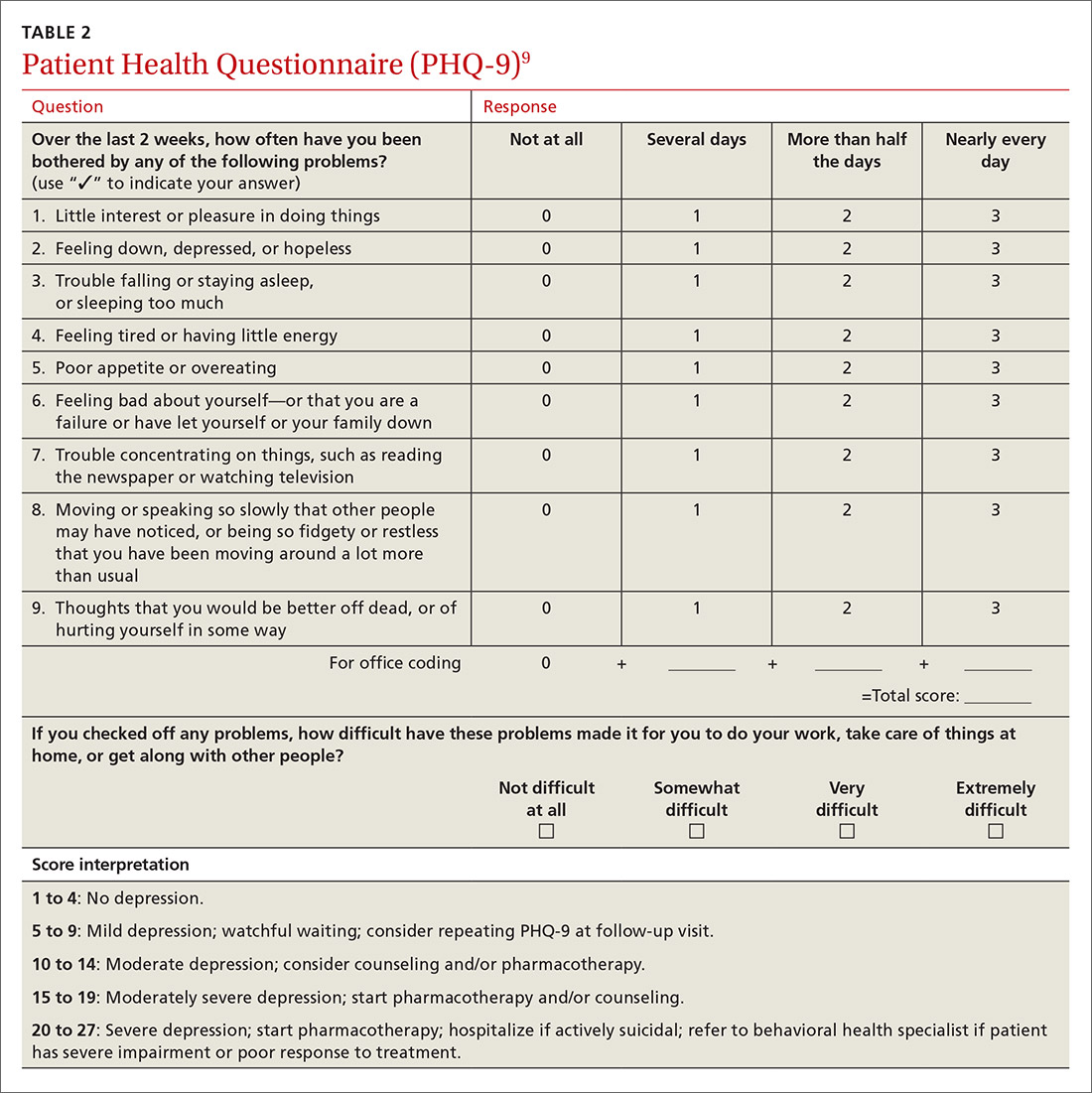

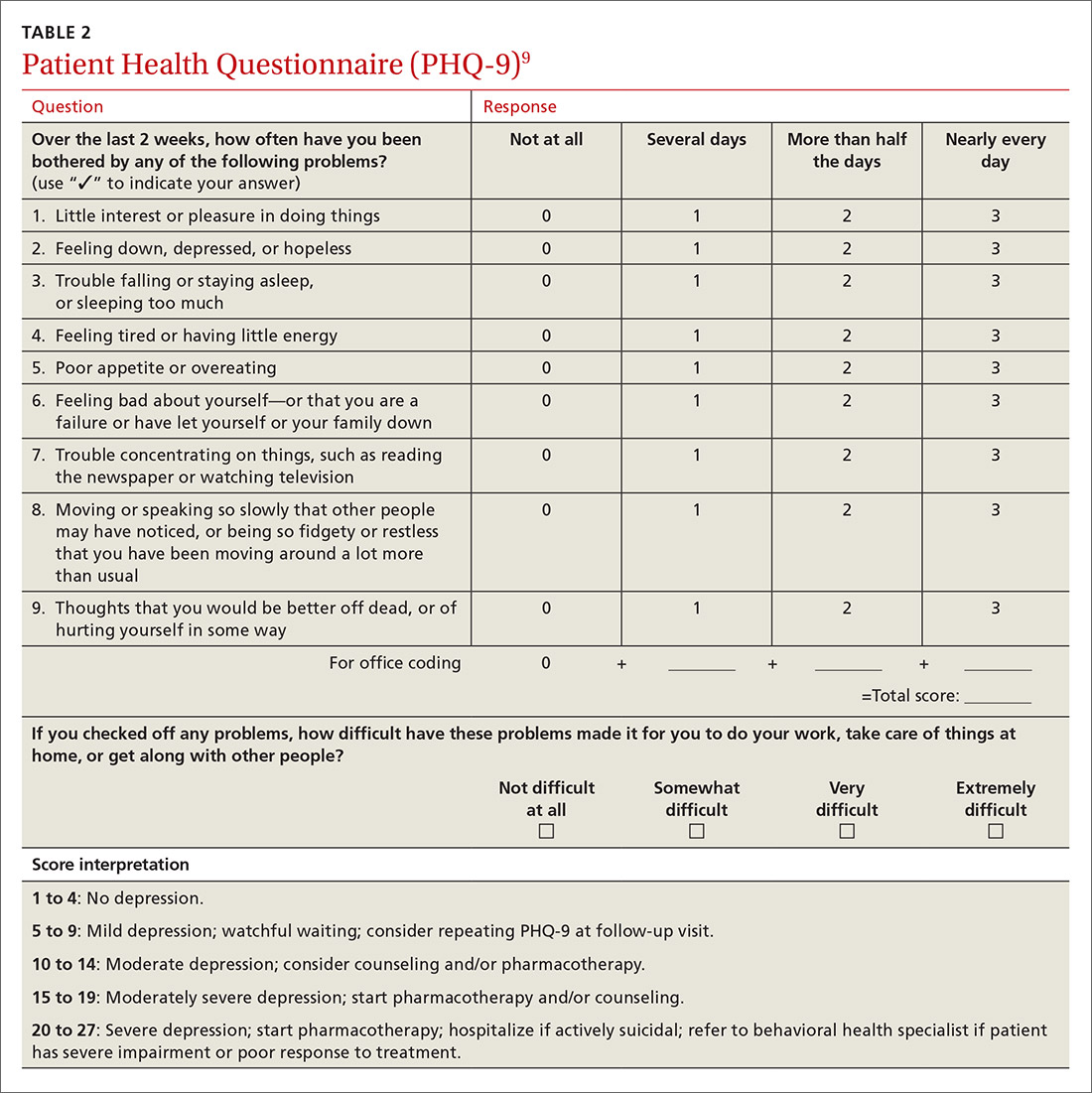

The physician had used the NIAAA single- question screen to determine that Ms. E drank more than 4 beers per day during social events and weekends, which occurred 2 to 3 times per month over the past year. She lives alone and said that she’d been seeing less and less of her boyfriend lately. Her score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which screens for depression, was 11, indicating moderate impairment. Her response on the CAGE questionnaire was negative for a problem with alcohol. However, her AUDIT score was 17, indicating a high-level alcohol problem. Based on these findings, her physician expressed concern that her alcohol use might be contributing to her symptoms and difficulties.

Although she did not have a history of increasing usage per day, a persistent desire to cut down, significant effort to obtain alcohol, or cravings, she was having work troubles and continued to drink even though it was straining relationships, promoting weight gain, and causing abdominal pain.

The physician asked her to schedule a return visit and ordered several blood studies. He also offered to connect her with a colleague with whom he collaborated who could speak with her about possible alcohol use disorders and depression.

Continue to: Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

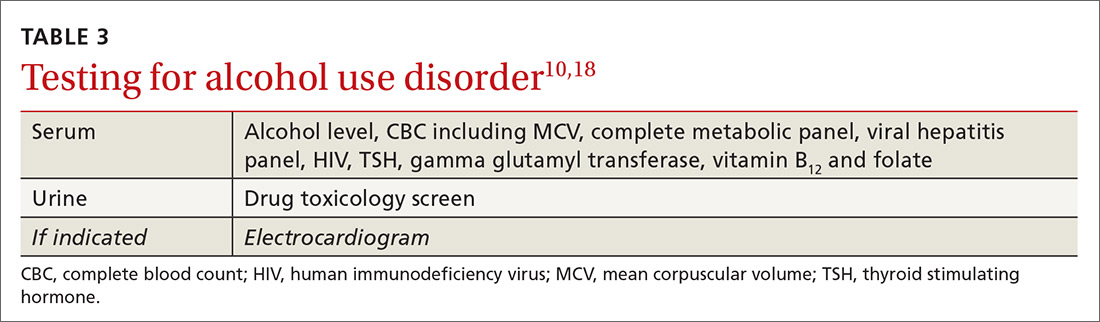

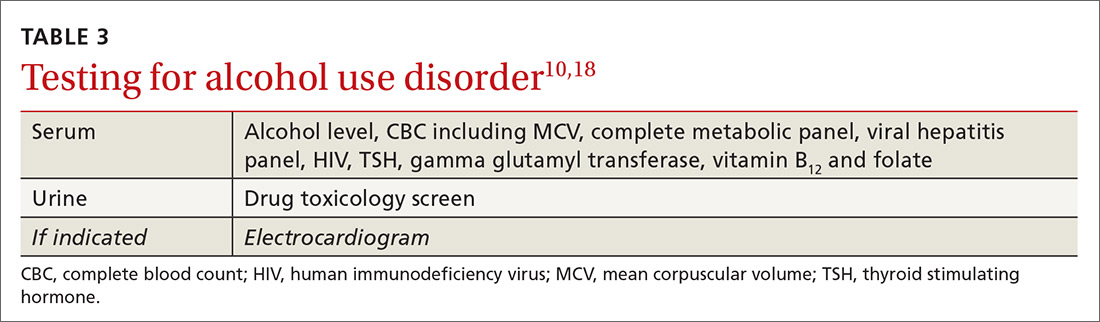

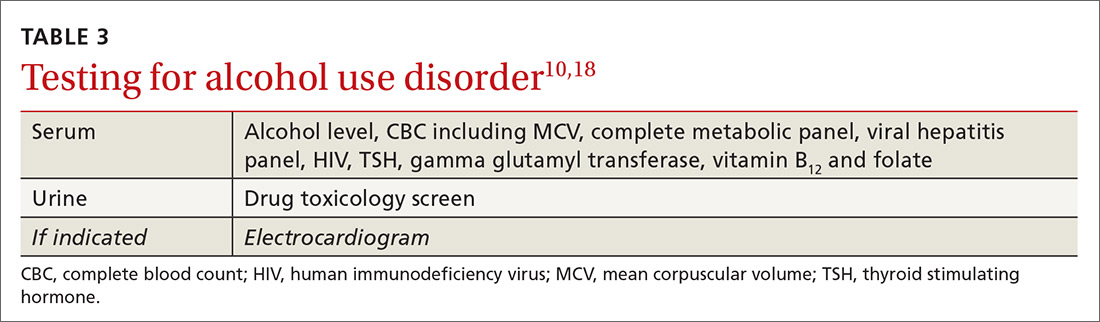

Lab tests used to measure hepatic injury due to alcohol include gamma-glutamyl-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and macrocytic volume, although the indices of hepatic damage have low specificity. Elevated serum ethanol levels can reveal recent alcohol use, and vitamin deficiencies and other abnormalities can be used to differentiate other causes of hepatic inflammation and co-existing health issues (TABLE 310,18). A number of as-yet-unvalidated biomarkers are being studied to assist in screening, diagnosing, and treating AUD.18

What treatment approaches work for AUD?

Family physicians can efficiently and productively address AUD by using alcohol screening and brief intervention, which have been shown to reduce risky drinking. Reimbursement for this service is covered by such CPT codes as 99408, 99409, or H0049, or with other evaluation and management (E/M) codes by using modifier 25.

Treatment of AUD varies and should be customized to each patient’s needs, readiness, preferences, and resources. Individual and group counseling approaches can be effective, and medications are available for inpatient and outpatient settings. Psychotherapy options include brief interventions, 12-step programs (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous—https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources),motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these options in detail, resources are available for those who wish to learn more.19-21

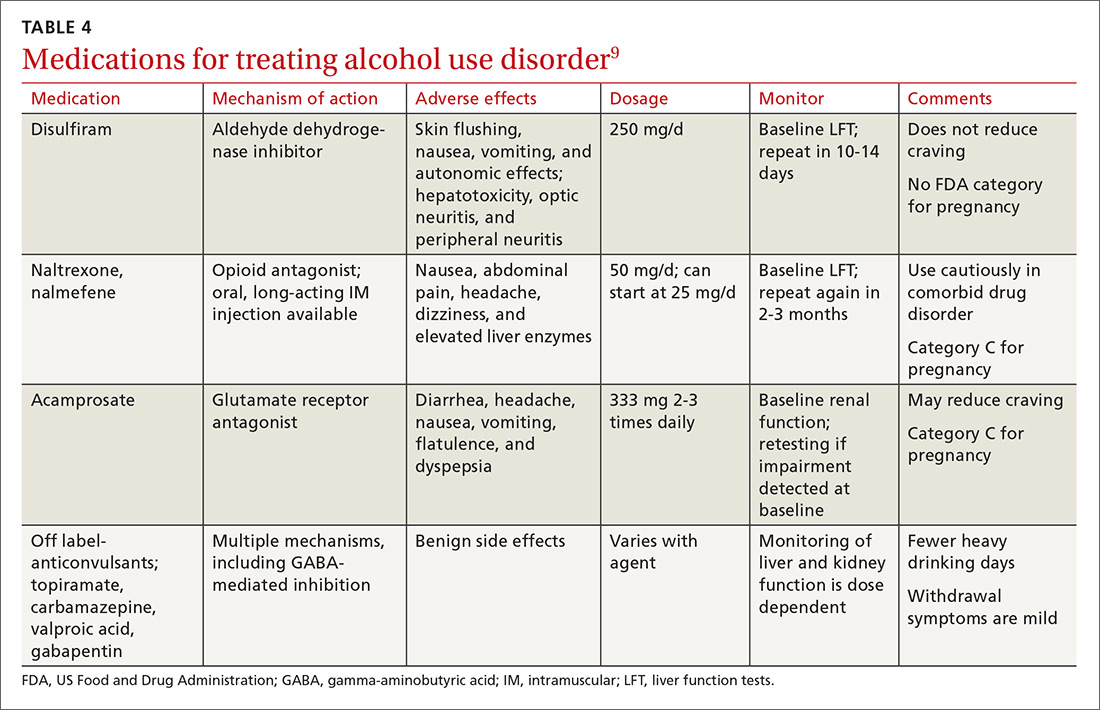

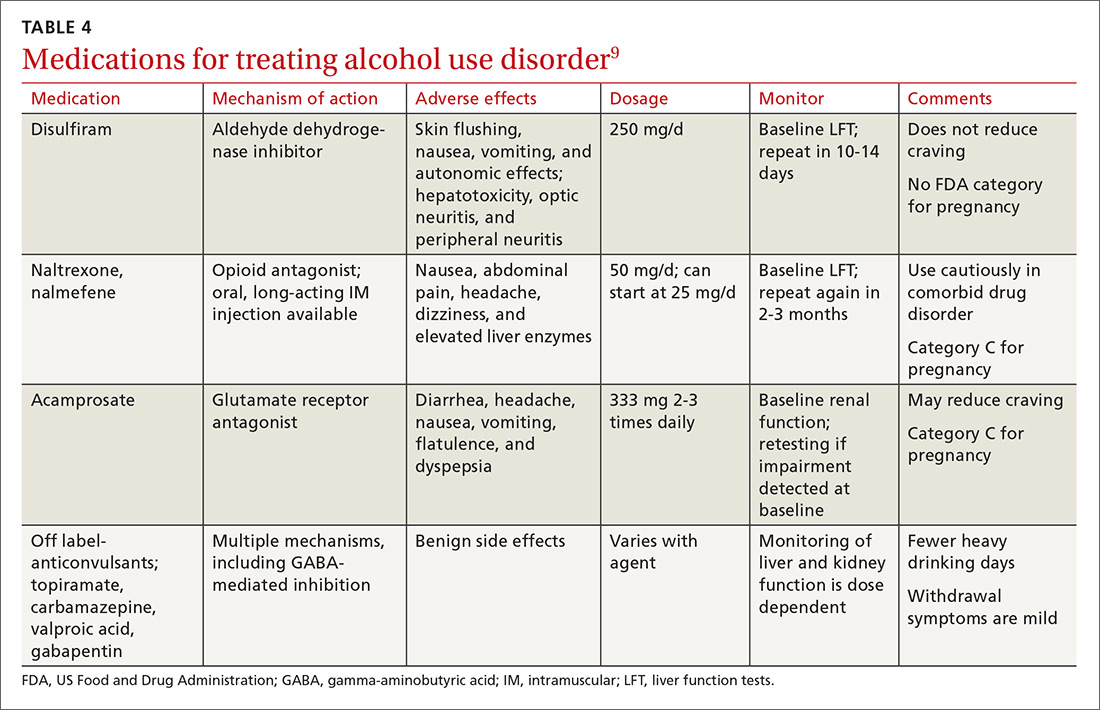

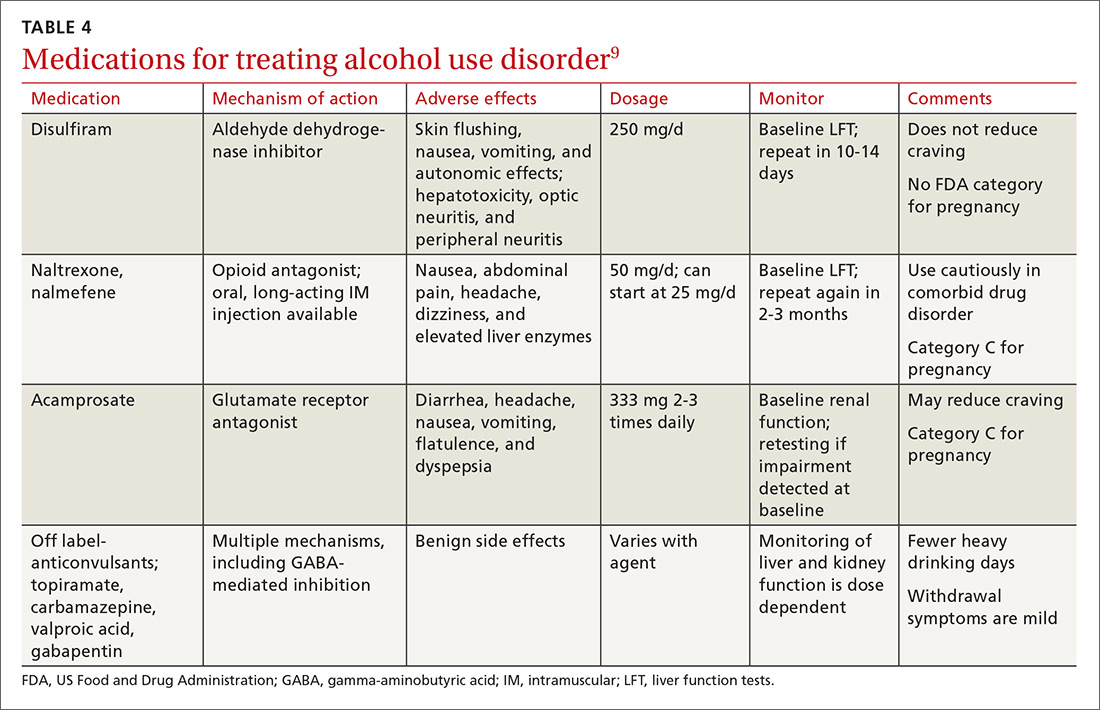

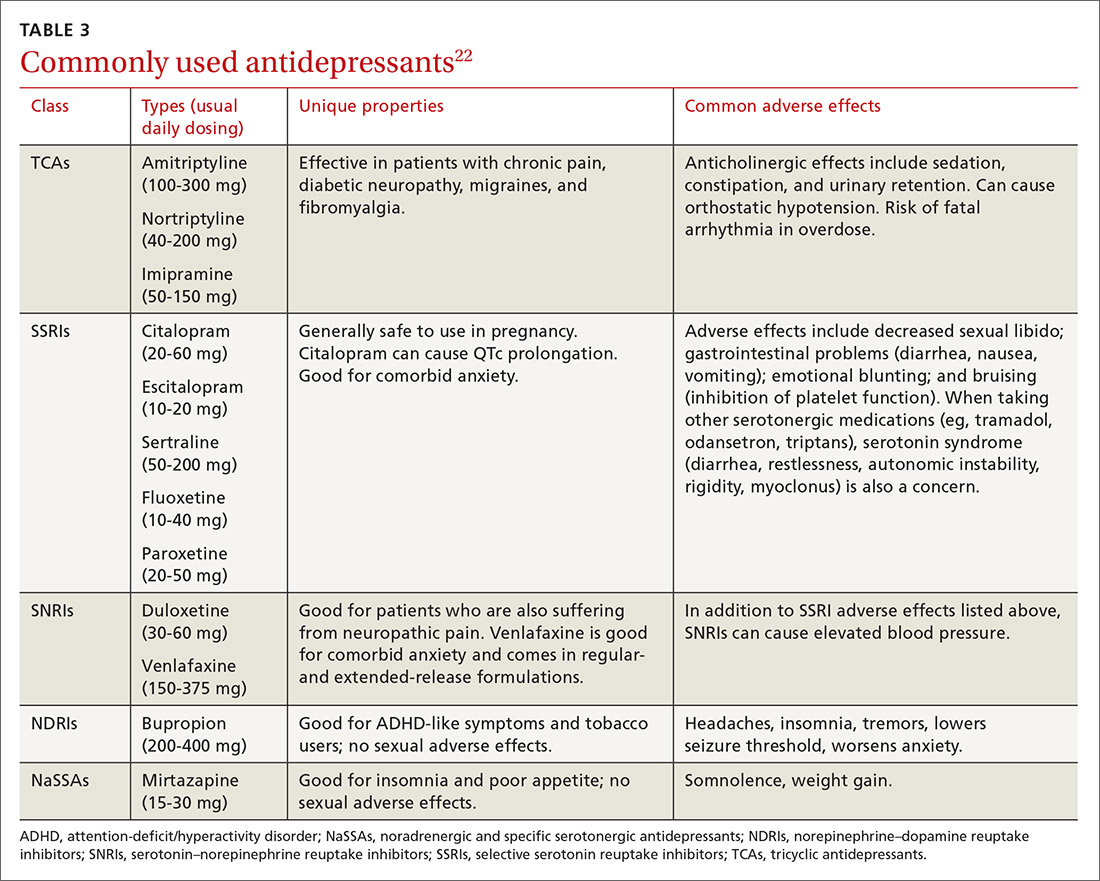

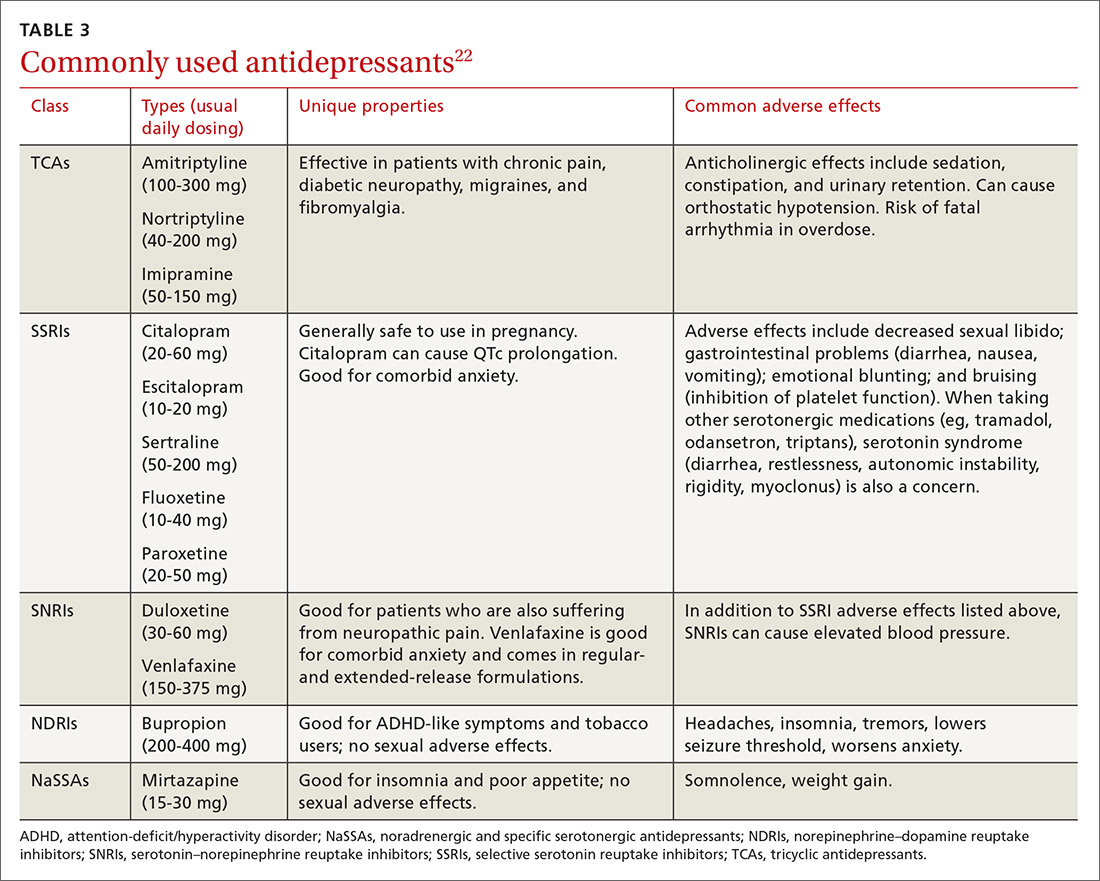

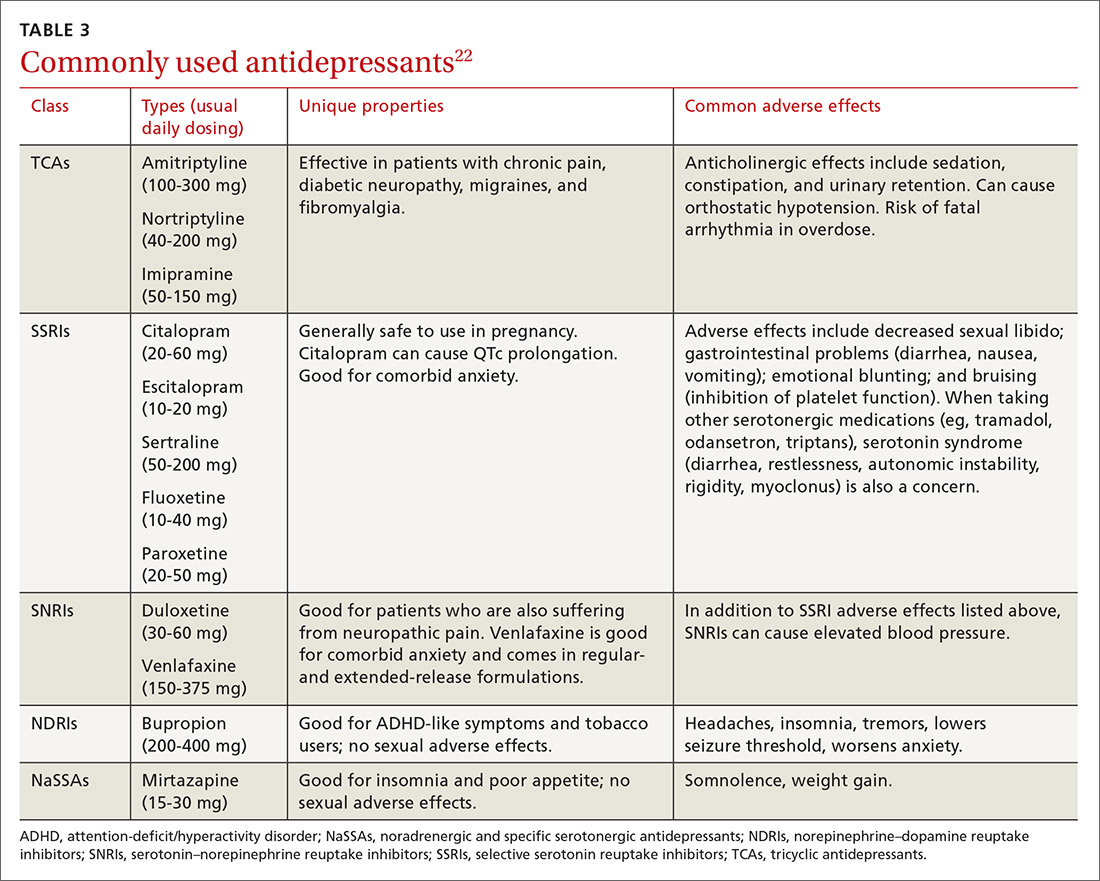

Psychopharmacologic management includes US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications such as disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate, and off-label uses of other medications (TABLE 49). Not enough empiric evidence is available to judge the effectiveness of these medications in adolescents, and the FDA has not approved them for such use. Evidence from meta-analyses comparing naltrexone and acamprosate have shown naltrexone to be more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and cravings, while acamprosate is effective in promoting abstinence.22,23 Naltrexone combined with behavioral intervention reduces the heavy drinking days and percentage of abstinence days.24

Current guideline recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association25 include:

- Naltrexone and acamprosate are recommended to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AUD in specific circumstances (eg, when nonpharmacologic approaches have failed to produce an effect or when patients prefer to use one of these medications).

- Topiramate and gabapentin are also suggested as medications for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD, but typically after first trying naltrexone and acamprosate.

- Disulfiram generally should not be used as first-line treatment. It produces physical reactions (eg, flushing) if alcohol is consumed within 12 to 24 hours of medication use.

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Ms. E was open to the idea of decreasing her alcohol use and agreed that she was depressed. Her lab tests at follow-up were normal other than an elevated AST/ALT of 90/80 U/L. S

She continued to get counseling for her AUD and for her comorbid depression in addition to taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She is now in early remission for her alcohol use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Metro Health Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

1. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

2. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC; 2013.

3. HHS. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2018.

4. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233.

5. Chase V, Neild R, Sadler CW, et al. The medical complications of alcohol use: understanding mechanisms to improve management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:253-265.

6. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:911-923.

7. Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care: a qualitative study in five VA clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:258-267.

8. Zhang DX, Li ST, Lee QK, et al. Systematic review of guidelines on managing patients with harmful use of alcohol in primary healthcare settings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52:595-609.

9. Wackernah RC, Minnick MJ, Clapp P. Alcohol use disorder: pathophysiology, effects, and pharmacologic options for treatment. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:1-12.

10. Kattimani S, Bharadwaj B. Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal: a systematic review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:100-108.

11. Gowin JL, Sloan ME, Stangl BL, et al. Vulnerability for alcohol use disorder and rate of alcohol consumption. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1094-1101.

12. Moyer VA; Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210-218.

13. Tarter RE, Alterman AI, Edwards KL. Vulnerability to alcoholism in men: a behavior-genetic perspective. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:329-356.

14. Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, et al. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood [published online ahead of print, October 22, 2013]. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:526-533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

15. Tan CH, Hungerford DW, Denny CH, et al. Screening for alcohol misuse: practices among U.S. primary care providers, DocStyles 2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:173-180.

16. Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:30-39.

17. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789-1795.

18. Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Biomolecules and biomarkers used in diagnosis of alcohol drinking and in monitoring therapeutic interventions. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1339-1385.

19. Raddock M, Martukovich R, Berko E, et al. 7 tools to help patients adopt healthier behaviors. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:97-103.

20. AHRQ. Whitlock EP, Green CA, Polen MR, et al. Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care to Reduce Risky/Harmful Alcohol Use. 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK42863/. Accessed November 17, 2018.

21. Miller WR, Baca C, Compton WM, et al. Addressing substance abuse in health care settings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:292-302.

22. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108:275-293.

23. Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:11-23.

24. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003-2017.

25. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:86-90.

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and often untreated condition that is increasingly prevalent in the United States.1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) characterizes AUD as a combination of signs and symptoms typifying alcohol abuse and dependence (discussed in a bit).2

Data from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showed 15.7 million Americans with AUD, affecting 6.2% of the population ages 18 years or older and 2.5% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 years.3

Alcohol use and AUD account for an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life years.4 AUD adversely affects several systems (TABLE 15), and patients with AUD are sicker and more likely to die younger than those without AUD.4 In the United States, prevalence of AUD has increased in recent years among women, older adults, racial minorities, and individuals with a low education level.6

Screening for AUD is reasonable and straightforward, although diagnosis and treatment of AUD in primary care settings may be challenging due to competing clinical priorities; lack of training, resources, and support; and skepticism about the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments.7,8 However, family physicians are in an excellent position to diagnose and help address the complex biopsychosocial needs of patients with AUD, often in collaboration with colleagues and community organizations.

Signs and symptoms of AUD

In clinical practice, at least 2 of the following 11 behaviors or symptoms are required to diagnose AUD2:

- consuming larger amounts of alcohol over a longer period than intended

- persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use

- making a significant effort to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol

In moderate-to-severe cases:

- cravings or urges to use alcohol

- recurrent failure to fulfill major work, school, or social obligations

- continued alcohol use despite recurrent social and interpersonal problems

- giving up social, occupational, and recreational activities due to alcohol

- using alcohol in physically dangerous situations

- continued alcohol use despite having physical or psychological problems

- tolerance to alcohol’s effects

- withdrawal symptoms.

Continue to: Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if...

Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if they exhibit 2 or 3 symptoms, moderate AUD with 4 or 5 symptoms, and severe AUD if there are 6 or more symptoms.2

Those who meet criteria for AUD and are able to stop using alcohol are deemed to be in early remission if the criteria have gone unfulfilled for at least 3 months and less than 12 months. Patients are considered to be in sustained remission if they have not met criteria for AUD at any time during a period of 12 months or longer.

How to detect AUD

Several clues in a patient’s history can suggest AUD (TABLE 29,10). Most imbibers are unaware of the dangers and may consider themselves merely “social drinkers.” Binge drinking may be an early indicator of vulnerability to AUD and should be assessed as part of a thorough clinical evaluation.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) that clinicians screen adults ages 18 years or older for alcohol misuse.12

Studies demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the development of AUD.13 A family history of excessive alcohol use increases the risk of AUD. Comorbidity of AUD and other mental health conditions is extremely common. For example, high rates of association between major depressive disorder and AUD have been observed.14

Tools to use in screening and diagnosing AUD

Screening for AUD during an office visit can be done fairly quickly. While 96% of primary care physicians screen for alcohol misuse in some way, only 38% use 1 of the 3 tools recommended by the USPSTF15—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the abbreviated AUDIT-C, or the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) single question screen—which detect the full spectrum of alcohol misuse in adults.12 Although the commonly used CAGE questionnaire is one of the most studied self-report tools, it has lower sensitivity at a lower level of alcohol intake.16

Continue to: The NIAAA single-question screen asks...

The NIAAA single-question screen asks how many times in the past year the patient had ≥4 drinks (women) or ≥5 drinks (men) in a day.15 The sensitivity and specificity of single-question screening are 82% to 87% and 61% to 79%, respectively, and the test has been validated in several different settings.12 The AUDIT screening tool, freely available from the World Health Organization, is a 10-item questionnaire that probes an individual’s alcohol intake, alcohol dependence, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. Administration of the AUDIT typically requires only 2 minutes. AUDIT-C17 is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT questionnaire that asks 3 consumption questions to screen for AUD.

It was found that AUDIT scores in the range of 8 to 15 indicate a medium-level alcohol problem, whereas a score of ≥16 indicates a high-level alcohol problem. The AUDIT-C is scored from 0 to 12, with ≥4 indicating a problem in men and ≥3

THE CASE

The physician had used the NIAAA single- question screen to determine that Ms. E drank more than 4 beers per day during social events and weekends, which occurred 2 to 3 times per month over the past year. She lives alone and said that she’d been seeing less and less of her boyfriend lately. Her score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which screens for depression, was 11, indicating moderate impairment. Her response on the CAGE questionnaire was negative for a problem with alcohol. However, her AUDIT score was 17, indicating a high-level alcohol problem. Based on these findings, her physician expressed concern that her alcohol use might be contributing to her symptoms and difficulties.

Although she did not have a history of increasing usage per day, a persistent desire to cut down, significant effort to obtain alcohol, or cravings, she was having work troubles and continued to drink even though it was straining relationships, promoting weight gain, and causing abdominal pain.

The physician asked her to schedule a return visit and ordered several blood studies. He also offered to connect her with a colleague with whom he collaborated who could speak with her about possible alcohol use disorders and depression.

Continue to: Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Lab tests used to measure hepatic injury due to alcohol include gamma-glutamyl-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and macrocytic volume, although the indices of hepatic damage have low specificity. Elevated serum ethanol levels can reveal recent alcohol use, and vitamin deficiencies and other abnormalities can be used to differentiate other causes of hepatic inflammation and co-existing health issues (TABLE 310,18). A number of as-yet-unvalidated biomarkers are being studied to assist in screening, diagnosing, and treating AUD.18

What treatment approaches work for AUD?

Family physicians can efficiently and productively address AUD by using alcohol screening and brief intervention, which have been shown to reduce risky drinking. Reimbursement for this service is covered by such CPT codes as 99408, 99409, or H0049, or with other evaluation and management (E/M) codes by using modifier 25.

Treatment of AUD varies and should be customized to each patient’s needs, readiness, preferences, and resources. Individual and group counseling approaches can be effective, and medications are available for inpatient and outpatient settings. Psychotherapy options include brief interventions, 12-step programs (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous—https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources),motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these options in detail, resources are available for those who wish to learn more.19-21

Psychopharmacologic management includes US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications such as disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate, and off-label uses of other medications (TABLE 49). Not enough empiric evidence is available to judge the effectiveness of these medications in adolescents, and the FDA has not approved them for such use. Evidence from meta-analyses comparing naltrexone and acamprosate have shown naltrexone to be more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and cravings, while acamprosate is effective in promoting abstinence.22,23 Naltrexone combined with behavioral intervention reduces the heavy drinking days and percentage of abstinence days.24

Current guideline recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association25 include:

- Naltrexone and acamprosate are recommended to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AUD in specific circumstances (eg, when nonpharmacologic approaches have failed to produce an effect or when patients prefer to use one of these medications).

- Topiramate and gabapentin are also suggested as medications for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD, but typically after first trying naltrexone and acamprosate.

- Disulfiram generally should not be used as first-line treatment. It produces physical reactions (eg, flushing) if alcohol is consumed within 12 to 24 hours of medication use.

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Ms. E was open to the idea of decreasing her alcohol use and agreed that she was depressed. Her lab tests at follow-up were normal other than an elevated AST/ALT of 90/80 U/L. S

She continued to get counseling for her AUD and for her comorbid depression in addition to taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She is now in early remission for her alcohol use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Metro Health Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?