User login

What Can We Do to Prevent Alzheimer Disease?

Alzheimer disease (AD) and other forms of dementia are pressing public health issues. They diminish quality of life for older adults and their families and impose significant financial costs on individuals and society. Dementia prevention and the development of treatments for dementia are important goals, and as a consequence, the VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) have been conducting innovative research for the treatment and prevention of AD and related dementias.

Research conducted at the VISN 20 GRECC at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (PSHCS) has helped increase clinicians’ understanding of the role of insulin in the development of AD and has evaluated the potential of treatment approaches based on the insulin-related research. More recently, this research has provided the basis for a pilot study aimed at dementia prevention for high-risk patients and for educational outreach about prevention within the VA.

Dementia Studies

The hormone insulin is required for efficient use of glucose throughout the body, including the brain. Insulin may also play a role in regulating cerebral amyloid, which is directly involved in the development of AD neuropathology and in maintaining healthy vascular function and lipid metabolism, both of which are required for brain health.1 Research over the past decade has shown that patients with AD have reduced levels of brain insulin, and individuals with insulin resistance have an increased risk of developing AD. Insulin resistance also has been shown to be related to reduced cerebral glucose metabolism, even in individuals who did not have a memory disorder.2

One recent study, led by Suzanne Craft, PhD, and colleagues at PSHCS, tested the potential of intranasal insulin to treat cognitive impairment.3 Participants with either AD or milder memory deficits used a specially designed device to deliver insulin or a placebo to the nose twice a day. Insulin provided in this way reaches the brain quickly without entering the lungs or affecting glucose metabolism elsewhere in the body. Participants who received the insulin experienced improvements in delayed memory and functional abilities compared with those who received the placebo.

Studies at the same laboratory investigated the role of diet and exercise in insulin metabolism and cognitive function. In a diet-related study, older adults with normal memory and those with mild memory impairment received either a high saturated fat, high glycemic index (GI) diet or a low saturated fat, low GI diet for 4 weeks.4 Plasma insulin levels decreased and delayed visual memory improved for participants who received the low-fat, low-GI diet. AD-related markers in cerebrospinal fluid, however, improved only among participants with mild memory impairment, not among healthy individuals.

In an exercise-related study, older adults with glucose intolerance participated in a 6-month aerobic exercise program.5 Although memory did not improve, cardiorespiratory fitness, executive function, and insulin sensitivity improved for participants in the aerobic exercise program compared with those in a stretching program. The relationship of diet and exercise and cognitive function is complex and likely involves insulin regulation, vascular function, and lipid metabolism, among other factors. More research is needed to fully understand the relationships among diet, exercise, and dementia, but these results suggest that lifestyle modifications may play a role in prevention of dementia.

When patients have problems with memory, attention, or executive function, they may have difficulty managing their medications, making good nutritional choices, and monitoring blood pressure and blood glucose.6 Given the importance of controlling vascular risk factors, helping patients manage their medical conditions may help them prevent or delay the onset of AD.

Pilot Study

A VA-funded pilot study with the goal of dementia prevention among high-risk patients was recently conducted at the PSHCS. This study focused on veterans at significantly elevated risk of dementia: those with both diabetes and hypertension, with poor control of either or both conditions, and who had some degree of memory or attentional impairment. Participants were randomly assigned to continue their usual care or to add a 6-month care management intervention to their usual care.

A registered nurse who helped the veterans overcome the barriers to controlling their medical conditions led the intervention. Barriers ranged from relatively simple problems, such as appropriate use of insulin, to more complex issues, such as learning about healthy nutrition and exercise for people with diabetes. The intervention was adapted to meet each participant’s cognitive level, and family involvement was encouraged, with the veteran’s permission. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America in 2011 and the Alzheimer’s Association International conference in July 2013.7,8

The VISN 20 GRECC also developed a “Dementia Roadshow” in which GRECC clinicians present educational, research-based lectures on dementia-related topics at VAMCs in VISN 20. One lecture in this series incorporates this recent research about prevention of dementia through control of diabetes and hypertension, as well as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other risk factors; the lecture is presented to frontline clinicians who can then use this information to guide their work with high-risk patients.

The GRECCs are at the forefront of understanding the causes of dementia and how to prevent it. This work will help the VA to develop more effective ways of reducing the public health burden of this disease.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Debby Tsuang, MD, Stephen Thielke, MD, and Julie Moorer, RN, for helpful feedback on the initial draft of this manuscript. The pilot project described was funded by VA VISN 20.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Craft S, Cholerton B, Baker LD. Insulin and Alzheimer’s disease: Untangling the web. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(suppl 1):S263-S275.

2. Baker LD, Cross DJ, Minoshima S, Belongia D, Watson GS, Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer-like reductions in regional cerebral glucose metabolism for cognitively normal adults with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(1):51-57.

3. Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):29-38.

4. Bayer-Carter JL, Green PS, Montine TJ, et al. Diet intervention and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6):743-752.

5. Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):569-579.

6. Bonner LM, Craft S. Uncontrolled diabetes plus hypertension: A recipe for dementia? Fed Pract. 2009;26(2):33-35.

7. Bonner LM, Craft S, Robinson G. Screening and care management for dementia prevention and management in VA primary care patients with vascular risk. Poster presented at: Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting; November 18, 2011; Boston, MA.

8. Bonner LM, Robinson G, Craft S. Care management for VA patients with vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment: A randomized trial. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 2013, Boston, MA.

Alzheimer disease (AD) and other forms of dementia are pressing public health issues. They diminish quality of life for older adults and their families and impose significant financial costs on individuals and society. Dementia prevention and the development of treatments for dementia are important goals, and as a consequence, the VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) have been conducting innovative research for the treatment and prevention of AD and related dementias.

Research conducted at the VISN 20 GRECC at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (PSHCS) has helped increase clinicians’ understanding of the role of insulin in the development of AD and has evaluated the potential of treatment approaches based on the insulin-related research. More recently, this research has provided the basis for a pilot study aimed at dementia prevention for high-risk patients and for educational outreach about prevention within the VA.

Dementia Studies

The hormone insulin is required for efficient use of glucose throughout the body, including the brain. Insulin may also play a role in regulating cerebral amyloid, which is directly involved in the development of AD neuropathology and in maintaining healthy vascular function and lipid metabolism, both of which are required for brain health.1 Research over the past decade has shown that patients with AD have reduced levels of brain insulin, and individuals with insulin resistance have an increased risk of developing AD. Insulin resistance also has been shown to be related to reduced cerebral glucose metabolism, even in individuals who did not have a memory disorder.2

One recent study, led by Suzanne Craft, PhD, and colleagues at PSHCS, tested the potential of intranasal insulin to treat cognitive impairment.3 Participants with either AD or milder memory deficits used a specially designed device to deliver insulin or a placebo to the nose twice a day. Insulin provided in this way reaches the brain quickly without entering the lungs or affecting glucose metabolism elsewhere in the body. Participants who received the insulin experienced improvements in delayed memory and functional abilities compared with those who received the placebo.

Studies at the same laboratory investigated the role of diet and exercise in insulin metabolism and cognitive function. In a diet-related study, older adults with normal memory and those with mild memory impairment received either a high saturated fat, high glycemic index (GI) diet or a low saturated fat, low GI diet for 4 weeks.4 Plasma insulin levels decreased and delayed visual memory improved for participants who received the low-fat, low-GI diet. AD-related markers in cerebrospinal fluid, however, improved only among participants with mild memory impairment, not among healthy individuals.

In an exercise-related study, older adults with glucose intolerance participated in a 6-month aerobic exercise program.5 Although memory did not improve, cardiorespiratory fitness, executive function, and insulin sensitivity improved for participants in the aerobic exercise program compared with those in a stretching program. The relationship of diet and exercise and cognitive function is complex and likely involves insulin regulation, vascular function, and lipid metabolism, among other factors. More research is needed to fully understand the relationships among diet, exercise, and dementia, but these results suggest that lifestyle modifications may play a role in prevention of dementia.

When patients have problems with memory, attention, or executive function, they may have difficulty managing their medications, making good nutritional choices, and monitoring blood pressure and blood glucose.6 Given the importance of controlling vascular risk factors, helping patients manage their medical conditions may help them prevent or delay the onset of AD.

Pilot Study

A VA-funded pilot study with the goal of dementia prevention among high-risk patients was recently conducted at the PSHCS. This study focused on veterans at significantly elevated risk of dementia: those with both diabetes and hypertension, with poor control of either or both conditions, and who had some degree of memory or attentional impairment. Participants were randomly assigned to continue their usual care or to add a 6-month care management intervention to their usual care.

A registered nurse who helped the veterans overcome the barriers to controlling their medical conditions led the intervention. Barriers ranged from relatively simple problems, such as appropriate use of insulin, to more complex issues, such as learning about healthy nutrition and exercise for people with diabetes. The intervention was adapted to meet each participant’s cognitive level, and family involvement was encouraged, with the veteran’s permission. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America in 2011 and the Alzheimer’s Association International conference in July 2013.7,8

The VISN 20 GRECC also developed a “Dementia Roadshow” in which GRECC clinicians present educational, research-based lectures on dementia-related topics at VAMCs in VISN 20. One lecture in this series incorporates this recent research about prevention of dementia through control of diabetes and hypertension, as well as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other risk factors; the lecture is presented to frontline clinicians who can then use this information to guide their work with high-risk patients.

The GRECCs are at the forefront of understanding the causes of dementia and how to prevent it. This work will help the VA to develop more effective ways of reducing the public health burden of this disease.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Debby Tsuang, MD, Stephen Thielke, MD, and Julie Moorer, RN, for helpful feedback on the initial draft of this manuscript. The pilot project described was funded by VA VISN 20.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Alzheimer disease (AD) and other forms of dementia are pressing public health issues. They diminish quality of life for older adults and their families and impose significant financial costs on individuals and society. Dementia prevention and the development of treatments for dementia are important goals, and as a consequence, the VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) have been conducting innovative research for the treatment and prevention of AD and related dementias.

Research conducted at the VISN 20 GRECC at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (PSHCS) has helped increase clinicians’ understanding of the role of insulin in the development of AD and has evaluated the potential of treatment approaches based on the insulin-related research. More recently, this research has provided the basis for a pilot study aimed at dementia prevention for high-risk patients and for educational outreach about prevention within the VA.

Dementia Studies

The hormone insulin is required for efficient use of glucose throughout the body, including the brain. Insulin may also play a role in regulating cerebral amyloid, which is directly involved in the development of AD neuropathology and in maintaining healthy vascular function and lipid metabolism, both of which are required for brain health.1 Research over the past decade has shown that patients with AD have reduced levels of brain insulin, and individuals with insulin resistance have an increased risk of developing AD. Insulin resistance also has been shown to be related to reduced cerebral glucose metabolism, even in individuals who did not have a memory disorder.2

One recent study, led by Suzanne Craft, PhD, and colleagues at PSHCS, tested the potential of intranasal insulin to treat cognitive impairment.3 Participants with either AD or milder memory deficits used a specially designed device to deliver insulin or a placebo to the nose twice a day. Insulin provided in this way reaches the brain quickly without entering the lungs or affecting glucose metabolism elsewhere in the body. Participants who received the insulin experienced improvements in delayed memory and functional abilities compared with those who received the placebo.

Studies at the same laboratory investigated the role of diet and exercise in insulin metabolism and cognitive function. In a diet-related study, older adults with normal memory and those with mild memory impairment received either a high saturated fat, high glycemic index (GI) diet or a low saturated fat, low GI diet for 4 weeks.4 Plasma insulin levels decreased and delayed visual memory improved for participants who received the low-fat, low-GI diet. AD-related markers in cerebrospinal fluid, however, improved only among participants with mild memory impairment, not among healthy individuals.

In an exercise-related study, older adults with glucose intolerance participated in a 6-month aerobic exercise program.5 Although memory did not improve, cardiorespiratory fitness, executive function, and insulin sensitivity improved for participants in the aerobic exercise program compared with those in a stretching program. The relationship of diet and exercise and cognitive function is complex and likely involves insulin regulation, vascular function, and lipid metabolism, among other factors. More research is needed to fully understand the relationships among diet, exercise, and dementia, but these results suggest that lifestyle modifications may play a role in prevention of dementia.

When patients have problems with memory, attention, or executive function, they may have difficulty managing their medications, making good nutritional choices, and monitoring blood pressure and blood glucose.6 Given the importance of controlling vascular risk factors, helping patients manage their medical conditions may help them prevent or delay the onset of AD.

Pilot Study

A VA-funded pilot study with the goal of dementia prevention among high-risk patients was recently conducted at the PSHCS. This study focused on veterans at significantly elevated risk of dementia: those with both diabetes and hypertension, with poor control of either or both conditions, and who had some degree of memory or attentional impairment. Participants were randomly assigned to continue their usual care or to add a 6-month care management intervention to their usual care.

A registered nurse who helped the veterans overcome the barriers to controlling their medical conditions led the intervention. Barriers ranged from relatively simple problems, such as appropriate use of insulin, to more complex issues, such as learning about healthy nutrition and exercise for people with diabetes. The intervention was adapted to meet each participant’s cognitive level, and family involvement was encouraged, with the veteran’s permission. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America in 2011 and the Alzheimer’s Association International conference in July 2013.7,8

The VISN 20 GRECC also developed a “Dementia Roadshow” in which GRECC clinicians present educational, research-based lectures on dementia-related topics at VAMCs in VISN 20. One lecture in this series incorporates this recent research about prevention of dementia through control of diabetes and hypertension, as well as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other risk factors; the lecture is presented to frontline clinicians who can then use this information to guide their work with high-risk patients.

The GRECCs are at the forefront of understanding the causes of dementia and how to prevent it. This work will help the VA to develop more effective ways of reducing the public health burden of this disease.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Debby Tsuang, MD, Stephen Thielke, MD, and Julie Moorer, RN, for helpful feedback on the initial draft of this manuscript. The pilot project described was funded by VA VISN 20.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Craft S, Cholerton B, Baker LD. Insulin and Alzheimer’s disease: Untangling the web. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(suppl 1):S263-S275.

2. Baker LD, Cross DJ, Minoshima S, Belongia D, Watson GS, Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer-like reductions in regional cerebral glucose metabolism for cognitively normal adults with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(1):51-57.

3. Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):29-38.

4. Bayer-Carter JL, Green PS, Montine TJ, et al. Diet intervention and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6):743-752.

5. Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):569-579.

6. Bonner LM, Craft S. Uncontrolled diabetes plus hypertension: A recipe for dementia? Fed Pract. 2009;26(2):33-35.

7. Bonner LM, Craft S, Robinson G. Screening and care management for dementia prevention and management in VA primary care patients with vascular risk. Poster presented at: Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting; November 18, 2011; Boston, MA.

8. Bonner LM, Robinson G, Craft S. Care management for VA patients with vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment: A randomized trial. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 2013, Boston, MA.

1. Craft S, Cholerton B, Baker LD. Insulin and Alzheimer’s disease: Untangling the web. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(suppl 1):S263-S275.

2. Baker LD, Cross DJ, Minoshima S, Belongia D, Watson GS, Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer-like reductions in regional cerebral glucose metabolism for cognitively normal adults with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(1):51-57.

3. Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):29-38.

4. Bayer-Carter JL, Green PS, Montine TJ, et al. Diet intervention and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6):743-752.

5. Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):569-579.

6. Bonner LM, Craft S. Uncontrolled diabetes plus hypertension: A recipe for dementia? Fed Pract. 2009;26(2):33-35.

7. Bonner LM, Craft S, Robinson G. Screening and care management for dementia prevention and management in VA primary care patients with vascular risk. Poster presented at: Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting; November 18, 2011; Boston, MA.

8. Bonner LM, Robinson G, Craft S. Care management for VA patients with vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment: A randomized trial. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 2013, Boston, MA.

Pharmacist-Managed Collaborative Practice for Chronic Stable Angina

Coronary artery disease (CAD) continues to have a significant impact on society. The latest update by the American Heart Association estimates that 83.6 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with an anticipated 15.4 million attributed to CAD.1 A portion of patients with CAD experience predictable chest pain, which occurs as a result of physical, emotional, or mental stress, more commonly referred to as chronic stable angina (CSA). Based on the most recent estimates, the incidence of patients who experience CSA is about 565,000 and increases in the male population through the eighth decade of life.1

Although it may be common, treatment options for patients with CSA are limited, as these patients may not be ideal candidates for coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and may often prefer less invasive treatments. It has also been demonstrated that optimal medical management results in similar cardiovascular outcomes when compared with optimal medical management combined with PCI.2,3 Therefore, optimizing medical management is a reasonable alternative for these individuals.

Pharmacists have been successful in implementing collaborative practices for the management of various conditions, including anticoagulation, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.4-7 Pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction and management, so it seems opportune that they also treat CSA.8 The latest estimated direct and indirect costs for CVD and stroke were well over $315 billion for 2010, and it is anticipated that the costs will continue to rise.1 Because CSA is typically a medically managed disease and due to its huge medical expense, the development of a pharmacist-managed collaborative practice for treating CSA may prove to be beneficial for both clinical and pharmacoeconomic outcomes.

Clinic Development and Practices

In June 2007, following the approval of ranolazine by the FDA, the VA adopted nonformulary criteria for ranolazine use (Appendix).9,10 In order for patients to receive ranolazine, health care providers (HCPs) within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS) network were required to submit an electronic nonformulary consult using the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Select clinical pharmacists who had knowledge of the health system’s nonformulary criteria and who were granted access to the electronic consults responded to the requests.

The consults primarily consisted of an automated template that required providers to fill out their contact information and the name of the requested nonformulary medication, dose, and clinical rationale for requesting the specified medication, including any previous treatments that the patient could not tolerate or on which the patient failed to achieve an adequate response. It was highly recommended but not required that the HCPs include other supporting information regarding the patient’s cardiovascular status, such as results from diagnostic cardiac catheterization, stress tests, electrocardiograms (ECGs), or echocardiograms if not readily available from the CPRS. If procedures or tests were conducted at outside facilities, then this information was supplied in the request or obtained with the patient’s consent. However, this information was not necessarily required in order to complete the nonformulary consult. Nonformulary requests for ranolazine were typically forwarded to the clinical pharmacists who specialized in cardiology.

A pharmacist-oriented collaborative practice was established to increase cost-effective use, improve monitoring by a HCP because of the drug’s ability to prolong the corrected QT (QTc) interval, and to more firmly establish its safety and efficacy in a veteran population. This practice operated in a clinic, which was staffed by a nurse, postdoctoral pharmacy fellow, clinical pharmacy specialist in cardiology, and a cardiologist. The nurse was responsible for obtaining the patient’s vitals and ECG and documenting them in the CPRS. The pharmacy fellow interviewed the patient and obtained pertinent medical and historical information before discussing any clinical recommendations with the clinical pharmacy specialist.

The recommendations consisted of drug initiation/discontinuation, dose adjustments, and assessing and ordering of pertinent laboratory values and ECGs, which took place under the scope of the clinical pharmacy specialist. The focus of the ECG was to assess for any evidence of excessive QTc prolongation. Due to the variable and subjective nature of CAD, a cardiologist was available at any time and was used to review any relevant information and further discuss any treatment recommendations.

Based in the NFSGVHS Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, clinic services were primarily offered to patients of that facility due to the limited number of cardiology providers and services offered at other NFSGVHS locations. Despite being driven by requests for ranolazine, especially after cardiac catheterization when further cardiac intervention may not have been feasible, all patients were allowed to enroll in the clinic at the discretion of their primary care provider (PCP) for optimization of their CSA regimen with the intent of adding ranolazine when appropriate.

Patients in outlying regions who met the criteria were supplied with ranolazine and continued to follow up with their HCPs as recommended by the criteria for use. Conversely, if patients from outside areas failed to meet the criteria, their PCPs were supplied with appropriate, alternative guideline-based recommendations for improving CSA with the option to resubmit the nonformulary consult.11 Recommendations regarding cardiovascular risk reduction were also sent to HCPs at that time, which included optimal endpoints for managing other conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia when necesary.8,11

Regardless of whether ranolazine was initiated at baseline, all patients enrolled in the clinic underwent appropriate labs and tests, including a basic metabolic panel, magnesium level, and an ECG, if not otherwise available from the CPRS or documented from outside facilities. A thorough history and description of the patient’s anginal symptoms were also taken at baseline and during follow-up visits. Once it was confirmed that the patients’ electrolytes were within normal limits and there was no evidence of prolongation in the Bazett’s QTc interval or major drug interactions, all patients who met criteria for ranolazine were initiated at 500 mg twice daily.9,12 The Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) was also completed by patients at the initiation of ranolazine and then again at follow-up visits. The SAQ is an 11-question, self-administered survey that measures functional status of patients with angina.13

All patients initiated on or ensuing dose changes with ranolazine followed up with the clinic at 1 and 3 months with labs and ECGs obtained prior to ensure that there were no electrolyte imbalances or excessive QTc prolongation. Excessive QTc prolongation was defined as an increase of ≥ 60 milliseconds (msec) from baseline or > 500 msec.14 If this boundary was exceeded, ranolazine was discontinued, or for those taking higher doses, it was reduced to the initial 500 mg twice daily as long as there was no previous excessive QTc prolongation. In cases where ranolazine was not added at baseline, doses of antianginal medications were titrated over appropriate intervals to improve angina symptoms with ranolazine subsequently added in conjunction with the nonformulary criteria.

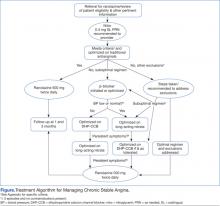

A generalized treatment algorithm was followed by the clinic for the management of CSA (Figure). It was highly recommended that all referred patients have an active prescription in the CPRS for short-acting sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg in case of any acute episodes. Although other forms of short-acting nitroglycerin were available, sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg was the preferred formulary medication at the time of the study.

Depending on whether the patients met nonformulary inclusion or exclusion criteria, they were either initiated or optimized on ranolazine or other traditional antianginals, such as beta-blockers (BBs), dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (DHP-CCBs), or long-acting nitrates (LANs). Beta-blockers were recommended as first-line treatment for patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI) and left ventricular dysfunction, in accordance with treatment guidelines and because of their benefits in treating patients with CSA.12,15

Once patients were optimized on BBs and/or DHP-CCBs, LANs were added if patients experienced ≥ 3 bothersome episodes of chest pain weekly. Optimization for BBs meant an ideal heart rate of at least about 60 bpm without symptoms suggestive of excessive bradycardia, whereas optimization for all 3 classes (BBs, DHP-CCBs, and LANs) consisted of dose titration until the presence of drug-related adverse effects (AEs) or symptoms suggestive of hypotension. Because LANs have lesser effects on blood pressure (BP) compared with DHP-CCBs, they were preferred in patients with persistent anginal symptoms whose BPs were considered low or normal, according to the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guidelines.16

If patients with normal or controlled BP continued to have symptoms of angina despite optimal doses of BBs and LANs, an appropriate dose of a DHP-CCB was administered and titrated for as long as the patients tolerated the treatment. If titration of antianginal agents was limited due to the presence of other antihypertensives, then the patient’s medication regimen was modified as necessary to allow for an increased dose of the BB or DHP-CCB due to these medications’ abilities to improve angina symptoms while also lowering BP. If patients achieved an acceptable reduction in their angina symptoms, they were discharged from the clinic, whereas those with contraindications to other classes were referred to their PCP or cardiologist.

Patients successfully treated with ranolazine (defined as a noticeable reduction in angina symptoms in the absence of intolerable AEs and excessive QTc prolongation after 3 months) were discharged from the clinic and instructed to follow up with their PCP at least annually. If the patient was discharged from the clinic at the baseline dose, it was recommended to the HCP that he or she follow up within 3 months after any dose increases. Any patient whose symptoms were consistent with unstable angina (described as occurring in an unpredictable manner, as determined by the clinical pharmacy specialist, lasting longer in duration and/or increasing in frequency, and those who experience symptoms at rest) were immediately evaluated and referred to a cardiologist. Patients who continued to have unacceptable rates or episodes of angina despite an optimal medical regimen were referred to Cardiology for consideration of other treatment modalities.

Results

The initial report of this study population was described by Reeder and colleagues.17 Fifty-seven patients were evaluated for study inclusion, of which 22 were excluded due to ranolazine being managed by an outside HCP or because an SAQ was not obtained at baseline. All study participants were males with an average age of 68 years and were predominantly white (86%). All patients had a past medical history significant for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. More than half (57%) had a prior MI and multivessel disease, although only 1 patient had an ejection fraction of < 35%. The majority of patients enrolled were being treated with BBs (97%) and LANs (94%) with a little more than half prescribed CCBs (60%). A large percentage (97%) of patients were also taking aspirin and a statin.

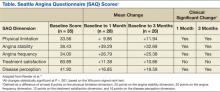

Improvements in angina symptoms as measured by the SAQ and safety measures, which included details of AEs and discontinuation rates following the initiation of ranolazine within the clinic, have previously been published.17 In summary, it was found that the addition of ranolazine to an optimal medical regimen for CSA improved all dimensions of the SAQ scores at 1 and 3 months compared with baseline (Table). Additionally, it was noted that higher doses may not have been as well tolerated in the veteran population, despite that only a small number of eligible patients were captured. This was because 5 of 7 patients whose dose was increased to 1,000 mg twice daily after 1 month required withdrawal as a result of AEs or lack of efficacy. The AEs reported included dizziness, abdominal pain, blurry vision, nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, and dyspnea.

The pharmacists were able to ensure that relevant electrolytes were replaced during the treatment period and also minimized the number of clinically significant drug interactions. Twenty-one patients received medications at baseline that had known interactions with ranolazine. Two patients required discontinuation of other medications: sotalol and diltiazem. At the time this study was conducted, diltiazem was contraindicated when given concomitantly but has since been allowed per manufacturer recommendations as long as the dose of ranolazine does not exceed 500 mg twice daily. Electrolyte replacement was also required in 3 patients, 2 of whom had hypomagnesemia.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have been influential in managing a variety of chronic diseases. When instituted into collaborative practice agreements, CSA is another unique condition that pharmacists can play a role in treating. Given that pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction, combined with the higher cost of ranolazine and the need for monitoring due to its AEs, QTc interval prolongation, and significant drug interactions, the benefits of having pharmacist-oriented clinics can ensure the safe and effective use of medications in the treatment of CSA.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28-e292.

2. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(15):1503-1516.

3. RITA-2 trial participants. Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: The second Randomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):461-468.

4. Norton JL, Gibson DL. Establishing an outpatient anticoagulation clinic in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1996;53(10):1151-1157.

5. Morello CM, Zadvorny EB, Cording MA, Suemoto RT, Skog J, Harari A. Development and clinical outcomes of pharmacist-managed diabetes care clinics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(14):1325-1331.

6. Vivian EM. Improving blood pressure control in a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(12):1533-1540.

7. Cording MA, Engelbrecht-Zadvorny EB, Pettit BJ, Eastham JH, Sandoval R. Development of a pharmacist-managed lipid clinic. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(5):892-904.

8. Geber J, Parra D, Beckey NP, Korman L. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: The impact of pharmacist-managed pharmacotherapy clinics in a primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22(6):738-747.

9. Ranexa [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2013.

10. VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group and the Medical Advisory Panel. Ranolazine. National PBM Drug Monograph. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Website. http://www.pbm.va.gov/clinicalguidance/drugmonographs/Ranolazine.pdf. Published June 2007. Accessed May 7, 2014.

11. Fraker TD Jr, Fihn SD; writing on behalf of the 2002 Chronic Stable Angina Writing Committee. 2007 chronic angina focused update of the ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Group to develop the focused update of the 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina. Circulation. 2007;116(23):2762-2772.

12. Funck-Brentano C, Jaillon P. Rate-corrected QT interval: Techniques and limitations. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(6):17B-22B.

13. Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(2):333-341.

14. Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-1060.

15. Heidenreich PA, McDonald KM, Hastie T, et al. Meta-analysis of trials comparing beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, and nitrates for stable angina. JAMA. 1999;281(20):1927-1936.

16. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572.

17. Reeder DN, Gillette MA, Franck AJ, Frohnapple DJ. Clinical experience with ranolazine in a veteran population with chronic stable angina. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(1):42-50.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) continues to have a significant impact on society. The latest update by the American Heart Association estimates that 83.6 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with an anticipated 15.4 million attributed to CAD.1 A portion of patients with CAD experience predictable chest pain, which occurs as a result of physical, emotional, or mental stress, more commonly referred to as chronic stable angina (CSA). Based on the most recent estimates, the incidence of patients who experience CSA is about 565,000 and increases in the male population through the eighth decade of life.1

Although it may be common, treatment options for patients with CSA are limited, as these patients may not be ideal candidates for coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and may often prefer less invasive treatments. It has also been demonstrated that optimal medical management results in similar cardiovascular outcomes when compared with optimal medical management combined with PCI.2,3 Therefore, optimizing medical management is a reasonable alternative for these individuals.

Pharmacists have been successful in implementing collaborative practices for the management of various conditions, including anticoagulation, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.4-7 Pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction and management, so it seems opportune that they also treat CSA.8 The latest estimated direct and indirect costs for CVD and stroke were well over $315 billion for 2010, and it is anticipated that the costs will continue to rise.1 Because CSA is typically a medically managed disease and due to its huge medical expense, the development of a pharmacist-managed collaborative practice for treating CSA may prove to be beneficial for both clinical and pharmacoeconomic outcomes.

Clinic Development and Practices

In June 2007, following the approval of ranolazine by the FDA, the VA adopted nonformulary criteria for ranolazine use (Appendix).9,10 In order for patients to receive ranolazine, health care providers (HCPs) within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS) network were required to submit an electronic nonformulary consult using the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Select clinical pharmacists who had knowledge of the health system’s nonformulary criteria and who were granted access to the electronic consults responded to the requests.

The consults primarily consisted of an automated template that required providers to fill out their contact information and the name of the requested nonformulary medication, dose, and clinical rationale for requesting the specified medication, including any previous treatments that the patient could not tolerate or on which the patient failed to achieve an adequate response. It was highly recommended but not required that the HCPs include other supporting information regarding the patient’s cardiovascular status, such as results from diagnostic cardiac catheterization, stress tests, electrocardiograms (ECGs), or echocardiograms if not readily available from the CPRS. If procedures or tests were conducted at outside facilities, then this information was supplied in the request or obtained with the patient’s consent. However, this information was not necessarily required in order to complete the nonformulary consult. Nonformulary requests for ranolazine were typically forwarded to the clinical pharmacists who specialized in cardiology.

A pharmacist-oriented collaborative practice was established to increase cost-effective use, improve monitoring by a HCP because of the drug’s ability to prolong the corrected QT (QTc) interval, and to more firmly establish its safety and efficacy in a veteran population. This practice operated in a clinic, which was staffed by a nurse, postdoctoral pharmacy fellow, clinical pharmacy specialist in cardiology, and a cardiologist. The nurse was responsible for obtaining the patient’s vitals and ECG and documenting them in the CPRS. The pharmacy fellow interviewed the patient and obtained pertinent medical and historical information before discussing any clinical recommendations with the clinical pharmacy specialist.

The recommendations consisted of drug initiation/discontinuation, dose adjustments, and assessing and ordering of pertinent laboratory values and ECGs, which took place under the scope of the clinical pharmacy specialist. The focus of the ECG was to assess for any evidence of excessive QTc prolongation. Due to the variable and subjective nature of CAD, a cardiologist was available at any time and was used to review any relevant information and further discuss any treatment recommendations.

Based in the NFSGVHS Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, clinic services were primarily offered to patients of that facility due to the limited number of cardiology providers and services offered at other NFSGVHS locations. Despite being driven by requests for ranolazine, especially after cardiac catheterization when further cardiac intervention may not have been feasible, all patients were allowed to enroll in the clinic at the discretion of their primary care provider (PCP) for optimization of their CSA regimen with the intent of adding ranolazine when appropriate.

Patients in outlying regions who met the criteria were supplied with ranolazine and continued to follow up with their HCPs as recommended by the criteria for use. Conversely, if patients from outside areas failed to meet the criteria, their PCPs were supplied with appropriate, alternative guideline-based recommendations for improving CSA with the option to resubmit the nonformulary consult.11 Recommendations regarding cardiovascular risk reduction were also sent to HCPs at that time, which included optimal endpoints for managing other conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia when necesary.8,11

Regardless of whether ranolazine was initiated at baseline, all patients enrolled in the clinic underwent appropriate labs and tests, including a basic metabolic panel, magnesium level, and an ECG, if not otherwise available from the CPRS or documented from outside facilities. A thorough history and description of the patient’s anginal symptoms were also taken at baseline and during follow-up visits. Once it was confirmed that the patients’ electrolytes were within normal limits and there was no evidence of prolongation in the Bazett’s QTc interval or major drug interactions, all patients who met criteria for ranolazine were initiated at 500 mg twice daily.9,12 The Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) was also completed by patients at the initiation of ranolazine and then again at follow-up visits. The SAQ is an 11-question, self-administered survey that measures functional status of patients with angina.13

All patients initiated on or ensuing dose changes with ranolazine followed up with the clinic at 1 and 3 months with labs and ECGs obtained prior to ensure that there were no electrolyte imbalances or excessive QTc prolongation. Excessive QTc prolongation was defined as an increase of ≥ 60 milliseconds (msec) from baseline or > 500 msec.14 If this boundary was exceeded, ranolazine was discontinued, or for those taking higher doses, it was reduced to the initial 500 mg twice daily as long as there was no previous excessive QTc prolongation. In cases where ranolazine was not added at baseline, doses of antianginal medications were titrated over appropriate intervals to improve angina symptoms with ranolazine subsequently added in conjunction with the nonformulary criteria.

A generalized treatment algorithm was followed by the clinic for the management of CSA (Figure). It was highly recommended that all referred patients have an active prescription in the CPRS for short-acting sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg in case of any acute episodes. Although other forms of short-acting nitroglycerin were available, sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg was the preferred formulary medication at the time of the study.

Depending on whether the patients met nonformulary inclusion or exclusion criteria, they were either initiated or optimized on ranolazine or other traditional antianginals, such as beta-blockers (BBs), dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (DHP-CCBs), or long-acting nitrates (LANs). Beta-blockers were recommended as first-line treatment for patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI) and left ventricular dysfunction, in accordance with treatment guidelines and because of their benefits in treating patients with CSA.12,15

Once patients were optimized on BBs and/or DHP-CCBs, LANs were added if patients experienced ≥ 3 bothersome episodes of chest pain weekly. Optimization for BBs meant an ideal heart rate of at least about 60 bpm without symptoms suggestive of excessive bradycardia, whereas optimization for all 3 classes (BBs, DHP-CCBs, and LANs) consisted of dose titration until the presence of drug-related adverse effects (AEs) or symptoms suggestive of hypotension. Because LANs have lesser effects on blood pressure (BP) compared with DHP-CCBs, they were preferred in patients with persistent anginal symptoms whose BPs were considered low or normal, according to the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guidelines.16

If patients with normal or controlled BP continued to have symptoms of angina despite optimal doses of BBs and LANs, an appropriate dose of a DHP-CCB was administered and titrated for as long as the patients tolerated the treatment. If titration of antianginal agents was limited due to the presence of other antihypertensives, then the patient’s medication regimen was modified as necessary to allow for an increased dose of the BB or DHP-CCB due to these medications’ abilities to improve angina symptoms while also lowering BP. If patients achieved an acceptable reduction in their angina symptoms, they were discharged from the clinic, whereas those with contraindications to other classes were referred to their PCP or cardiologist.

Patients successfully treated with ranolazine (defined as a noticeable reduction in angina symptoms in the absence of intolerable AEs and excessive QTc prolongation after 3 months) were discharged from the clinic and instructed to follow up with their PCP at least annually. If the patient was discharged from the clinic at the baseline dose, it was recommended to the HCP that he or she follow up within 3 months after any dose increases. Any patient whose symptoms were consistent with unstable angina (described as occurring in an unpredictable manner, as determined by the clinical pharmacy specialist, lasting longer in duration and/or increasing in frequency, and those who experience symptoms at rest) were immediately evaluated and referred to a cardiologist. Patients who continued to have unacceptable rates or episodes of angina despite an optimal medical regimen were referred to Cardiology for consideration of other treatment modalities.

Results

The initial report of this study population was described by Reeder and colleagues.17 Fifty-seven patients were evaluated for study inclusion, of which 22 were excluded due to ranolazine being managed by an outside HCP or because an SAQ was not obtained at baseline. All study participants were males with an average age of 68 years and were predominantly white (86%). All patients had a past medical history significant for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. More than half (57%) had a prior MI and multivessel disease, although only 1 patient had an ejection fraction of < 35%. The majority of patients enrolled were being treated with BBs (97%) and LANs (94%) with a little more than half prescribed CCBs (60%). A large percentage (97%) of patients were also taking aspirin and a statin.

Improvements in angina symptoms as measured by the SAQ and safety measures, which included details of AEs and discontinuation rates following the initiation of ranolazine within the clinic, have previously been published.17 In summary, it was found that the addition of ranolazine to an optimal medical regimen for CSA improved all dimensions of the SAQ scores at 1 and 3 months compared with baseline (Table). Additionally, it was noted that higher doses may not have been as well tolerated in the veteran population, despite that only a small number of eligible patients were captured. This was because 5 of 7 patients whose dose was increased to 1,000 mg twice daily after 1 month required withdrawal as a result of AEs or lack of efficacy. The AEs reported included dizziness, abdominal pain, blurry vision, nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, and dyspnea.

The pharmacists were able to ensure that relevant electrolytes were replaced during the treatment period and also minimized the number of clinically significant drug interactions. Twenty-one patients received medications at baseline that had known interactions with ranolazine. Two patients required discontinuation of other medications: sotalol and diltiazem. At the time this study was conducted, diltiazem was contraindicated when given concomitantly but has since been allowed per manufacturer recommendations as long as the dose of ranolazine does not exceed 500 mg twice daily. Electrolyte replacement was also required in 3 patients, 2 of whom had hypomagnesemia.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have been influential in managing a variety of chronic diseases. When instituted into collaborative practice agreements, CSA is another unique condition that pharmacists can play a role in treating. Given that pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction, combined with the higher cost of ranolazine and the need for monitoring due to its AEs, QTc interval prolongation, and significant drug interactions, the benefits of having pharmacist-oriented clinics can ensure the safe and effective use of medications in the treatment of CSA.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) continues to have a significant impact on society. The latest update by the American Heart Association estimates that 83.6 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with an anticipated 15.4 million attributed to CAD.1 A portion of patients with CAD experience predictable chest pain, which occurs as a result of physical, emotional, or mental stress, more commonly referred to as chronic stable angina (CSA). Based on the most recent estimates, the incidence of patients who experience CSA is about 565,000 and increases in the male population through the eighth decade of life.1

Although it may be common, treatment options for patients with CSA are limited, as these patients may not be ideal candidates for coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and may often prefer less invasive treatments. It has also been demonstrated that optimal medical management results in similar cardiovascular outcomes when compared with optimal medical management combined with PCI.2,3 Therefore, optimizing medical management is a reasonable alternative for these individuals.

Pharmacists have been successful in implementing collaborative practices for the management of various conditions, including anticoagulation, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.4-7 Pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction and management, so it seems opportune that they also treat CSA.8 The latest estimated direct and indirect costs for CVD and stroke were well over $315 billion for 2010, and it is anticipated that the costs will continue to rise.1 Because CSA is typically a medically managed disease and due to its huge medical expense, the development of a pharmacist-managed collaborative practice for treating CSA may prove to be beneficial for both clinical and pharmacoeconomic outcomes.

Clinic Development and Practices

In June 2007, following the approval of ranolazine by the FDA, the VA adopted nonformulary criteria for ranolazine use (Appendix).9,10 In order for patients to receive ranolazine, health care providers (HCPs) within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS) network were required to submit an electronic nonformulary consult using the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Select clinical pharmacists who had knowledge of the health system’s nonformulary criteria and who were granted access to the electronic consults responded to the requests.

The consults primarily consisted of an automated template that required providers to fill out their contact information and the name of the requested nonformulary medication, dose, and clinical rationale for requesting the specified medication, including any previous treatments that the patient could not tolerate or on which the patient failed to achieve an adequate response. It was highly recommended but not required that the HCPs include other supporting information regarding the patient’s cardiovascular status, such as results from diagnostic cardiac catheterization, stress tests, electrocardiograms (ECGs), or echocardiograms if not readily available from the CPRS. If procedures or tests were conducted at outside facilities, then this information was supplied in the request or obtained with the patient’s consent. However, this information was not necessarily required in order to complete the nonformulary consult. Nonformulary requests for ranolazine were typically forwarded to the clinical pharmacists who specialized in cardiology.

A pharmacist-oriented collaborative practice was established to increase cost-effective use, improve monitoring by a HCP because of the drug’s ability to prolong the corrected QT (QTc) interval, and to more firmly establish its safety and efficacy in a veteran population. This practice operated in a clinic, which was staffed by a nurse, postdoctoral pharmacy fellow, clinical pharmacy specialist in cardiology, and a cardiologist. The nurse was responsible for obtaining the patient’s vitals and ECG and documenting them in the CPRS. The pharmacy fellow interviewed the patient and obtained pertinent medical and historical information before discussing any clinical recommendations with the clinical pharmacy specialist.

The recommendations consisted of drug initiation/discontinuation, dose adjustments, and assessing and ordering of pertinent laboratory values and ECGs, which took place under the scope of the clinical pharmacy specialist. The focus of the ECG was to assess for any evidence of excessive QTc prolongation. Due to the variable and subjective nature of CAD, a cardiologist was available at any time and was used to review any relevant information and further discuss any treatment recommendations.

Based in the NFSGVHS Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, clinic services were primarily offered to patients of that facility due to the limited number of cardiology providers and services offered at other NFSGVHS locations. Despite being driven by requests for ranolazine, especially after cardiac catheterization when further cardiac intervention may not have been feasible, all patients were allowed to enroll in the clinic at the discretion of their primary care provider (PCP) for optimization of their CSA regimen with the intent of adding ranolazine when appropriate.

Patients in outlying regions who met the criteria were supplied with ranolazine and continued to follow up with their HCPs as recommended by the criteria for use. Conversely, if patients from outside areas failed to meet the criteria, their PCPs were supplied with appropriate, alternative guideline-based recommendations for improving CSA with the option to resubmit the nonformulary consult.11 Recommendations regarding cardiovascular risk reduction were also sent to HCPs at that time, which included optimal endpoints for managing other conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia when necesary.8,11

Regardless of whether ranolazine was initiated at baseline, all patients enrolled in the clinic underwent appropriate labs and tests, including a basic metabolic panel, magnesium level, and an ECG, if not otherwise available from the CPRS or documented from outside facilities. A thorough history and description of the patient’s anginal symptoms were also taken at baseline and during follow-up visits. Once it was confirmed that the patients’ electrolytes were within normal limits and there was no evidence of prolongation in the Bazett’s QTc interval or major drug interactions, all patients who met criteria for ranolazine were initiated at 500 mg twice daily.9,12 The Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) was also completed by patients at the initiation of ranolazine and then again at follow-up visits. The SAQ is an 11-question, self-administered survey that measures functional status of patients with angina.13

All patients initiated on or ensuing dose changes with ranolazine followed up with the clinic at 1 and 3 months with labs and ECGs obtained prior to ensure that there were no electrolyte imbalances or excessive QTc prolongation. Excessive QTc prolongation was defined as an increase of ≥ 60 milliseconds (msec) from baseline or > 500 msec.14 If this boundary was exceeded, ranolazine was discontinued, or for those taking higher doses, it was reduced to the initial 500 mg twice daily as long as there was no previous excessive QTc prolongation. In cases where ranolazine was not added at baseline, doses of antianginal medications were titrated over appropriate intervals to improve angina symptoms with ranolazine subsequently added in conjunction with the nonformulary criteria.

A generalized treatment algorithm was followed by the clinic for the management of CSA (Figure). It was highly recommended that all referred patients have an active prescription in the CPRS for short-acting sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg in case of any acute episodes. Although other forms of short-acting nitroglycerin were available, sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg was the preferred formulary medication at the time of the study.

Depending on whether the patients met nonformulary inclusion or exclusion criteria, they were either initiated or optimized on ranolazine or other traditional antianginals, such as beta-blockers (BBs), dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (DHP-CCBs), or long-acting nitrates (LANs). Beta-blockers were recommended as first-line treatment for patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI) and left ventricular dysfunction, in accordance with treatment guidelines and because of their benefits in treating patients with CSA.12,15

Once patients were optimized on BBs and/or DHP-CCBs, LANs were added if patients experienced ≥ 3 bothersome episodes of chest pain weekly. Optimization for BBs meant an ideal heart rate of at least about 60 bpm without symptoms suggestive of excessive bradycardia, whereas optimization for all 3 classes (BBs, DHP-CCBs, and LANs) consisted of dose titration until the presence of drug-related adverse effects (AEs) or symptoms suggestive of hypotension. Because LANs have lesser effects on blood pressure (BP) compared with DHP-CCBs, they were preferred in patients with persistent anginal symptoms whose BPs were considered low or normal, according to the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guidelines.16

If patients with normal or controlled BP continued to have symptoms of angina despite optimal doses of BBs and LANs, an appropriate dose of a DHP-CCB was administered and titrated for as long as the patients tolerated the treatment. If titration of antianginal agents was limited due to the presence of other antihypertensives, then the patient’s medication regimen was modified as necessary to allow for an increased dose of the BB or DHP-CCB due to these medications’ abilities to improve angina symptoms while also lowering BP. If patients achieved an acceptable reduction in their angina symptoms, they were discharged from the clinic, whereas those with contraindications to other classes were referred to their PCP or cardiologist.

Patients successfully treated with ranolazine (defined as a noticeable reduction in angina symptoms in the absence of intolerable AEs and excessive QTc prolongation after 3 months) were discharged from the clinic and instructed to follow up with their PCP at least annually. If the patient was discharged from the clinic at the baseline dose, it was recommended to the HCP that he or she follow up within 3 months after any dose increases. Any patient whose symptoms were consistent with unstable angina (described as occurring in an unpredictable manner, as determined by the clinical pharmacy specialist, lasting longer in duration and/or increasing in frequency, and those who experience symptoms at rest) were immediately evaluated and referred to a cardiologist. Patients who continued to have unacceptable rates or episodes of angina despite an optimal medical regimen were referred to Cardiology for consideration of other treatment modalities.

Results

The initial report of this study population was described by Reeder and colleagues.17 Fifty-seven patients were evaluated for study inclusion, of which 22 were excluded due to ranolazine being managed by an outside HCP or because an SAQ was not obtained at baseline. All study participants were males with an average age of 68 years and were predominantly white (86%). All patients had a past medical history significant for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. More than half (57%) had a prior MI and multivessel disease, although only 1 patient had an ejection fraction of < 35%. The majority of patients enrolled were being treated with BBs (97%) and LANs (94%) with a little more than half prescribed CCBs (60%). A large percentage (97%) of patients were also taking aspirin and a statin.

Improvements in angina symptoms as measured by the SAQ and safety measures, which included details of AEs and discontinuation rates following the initiation of ranolazine within the clinic, have previously been published.17 In summary, it was found that the addition of ranolazine to an optimal medical regimen for CSA improved all dimensions of the SAQ scores at 1 and 3 months compared with baseline (Table). Additionally, it was noted that higher doses may not have been as well tolerated in the veteran population, despite that only a small number of eligible patients were captured. This was because 5 of 7 patients whose dose was increased to 1,000 mg twice daily after 1 month required withdrawal as a result of AEs or lack of efficacy. The AEs reported included dizziness, abdominal pain, blurry vision, nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, and dyspnea.

The pharmacists were able to ensure that relevant electrolytes were replaced during the treatment period and also minimized the number of clinically significant drug interactions. Twenty-one patients received medications at baseline that had known interactions with ranolazine. Two patients required discontinuation of other medications: sotalol and diltiazem. At the time this study was conducted, diltiazem was contraindicated when given concomitantly but has since been allowed per manufacturer recommendations as long as the dose of ranolazine does not exceed 500 mg twice daily. Electrolyte replacement was also required in 3 patients, 2 of whom had hypomagnesemia.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have been influential in managing a variety of chronic diseases. When instituted into collaborative practice agreements, CSA is another unique condition that pharmacists can play a role in treating. Given that pharmacists are heavily involved with cardiovascular risk reduction, combined with the higher cost of ranolazine and the need for monitoring due to its AEs, QTc interval prolongation, and significant drug interactions, the benefits of having pharmacist-oriented clinics can ensure the safe and effective use of medications in the treatment of CSA.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28-e292.

2. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(15):1503-1516.

3. RITA-2 trial participants. Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: The second Randomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):461-468.

4. Norton JL, Gibson DL. Establishing an outpatient anticoagulation clinic in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1996;53(10):1151-1157.

5. Morello CM, Zadvorny EB, Cording MA, Suemoto RT, Skog J, Harari A. Development and clinical outcomes of pharmacist-managed diabetes care clinics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(14):1325-1331.

6. Vivian EM. Improving blood pressure control in a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(12):1533-1540.

7. Cording MA, Engelbrecht-Zadvorny EB, Pettit BJ, Eastham JH, Sandoval R. Development of a pharmacist-managed lipid clinic. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(5):892-904.

8. Geber J, Parra D, Beckey NP, Korman L. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: The impact of pharmacist-managed pharmacotherapy clinics in a primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22(6):738-747.

9. Ranexa [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2013.

10. VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group and the Medical Advisory Panel. Ranolazine. National PBM Drug Monograph. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Website. http://www.pbm.va.gov/clinicalguidance/drugmonographs/Ranolazine.pdf. Published June 2007. Accessed May 7, 2014.

11. Fraker TD Jr, Fihn SD; writing on behalf of the 2002 Chronic Stable Angina Writing Committee. 2007 chronic angina focused update of the ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Group to develop the focused update of the 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina. Circulation. 2007;116(23):2762-2772.

12. Funck-Brentano C, Jaillon P. Rate-corrected QT interval: Techniques and limitations. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(6):17B-22B.

13. Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(2):333-341.

14. Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-1060.

15. Heidenreich PA, McDonald KM, Hastie T, et al. Meta-analysis of trials comparing beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, and nitrates for stable angina. JAMA. 1999;281(20):1927-1936.

16. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572.

17. Reeder DN, Gillette MA, Franck AJ, Frohnapple DJ. Clinical experience with ranolazine in a veteran population with chronic stable angina. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(1):42-50.

1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28-e292.

2. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(15):1503-1516.

3. RITA-2 trial participants. Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: The second Randomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):461-468.

4. Norton JL, Gibson DL. Establishing an outpatient anticoagulation clinic in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1996;53(10):1151-1157.

5. Morello CM, Zadvorny EB, Cording MA, Suemoto RT, Skog J, Harari A. Development and clinical outcomes of pharmacist-managed diabetes care clinics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(14):1325-1331.

6. Vivian EM. Improving blood pressure control in a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(12):1533-1540.

7. Cording MA, Engelbrecht-Zadvorny EB, Pettit BJ, Eastham JH, Sandoval R. Development of a pharmacist-managed lipid clinic. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(5):892-904.

8. Geber J, Parra D, Beckey NP, Korman L. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: The impact of pharmacist-managed pharmacotherapy clinics in a primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22(6):738-747.

9. Ranexa [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2013.

10. VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group and the Medical Advisory Panel. Ranolazine. National PBM Drug Monograph. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Website. http://www.pbm.va.gov/clinicalguidance/drugmonographs/Ranolazine.pdf. Published June 2007. Accessed May 7, 2014.