User login

Hospitalist movers and shakers – November 2019

Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, has been announced as Southeast Health Statera Network’s (Dothan, Ala.) director of physician integration, and chairman of the network’s Physicians Participation Committee. Dr. Skandhan is senior lead hospitalist with Southeast Health, where he has worked for nearly a decade. He also champions the medical group’s clinical documentation improvement faction.

One of just 10 hospitalists in the nation to receive Top Hospitalist recognition by the American College of Physicians in 2018, Dr. Skandhan is also an assistant professor at Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine and is one of Southeast Health’s Internal Medicine Residency Program’s core faculty members.

Ruby Sahoo, DO, has been promoted by Team Health (Knoxville, Tenn.) as regional performance director of its hospitalist services performance improvement team. Dr. Sahoo joined Team Health in 2016 and has most recently served as medical director and chief of staff at Grand Strand Medical Center (Myrtle Beach, S.C.).

Dr. Sahoo is a highly decorated internist and hospitalist. She was Team Health’s Medical Director of the Year for Hospital Medicine 2018, and a Frist Humanitarian Award winner in 2017. Additionally, Dr. Sahoo is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American College of Physicians, and the American Association of Physician Leadership.

David Vandenberg, MD, SFHM, recently was elevated to chief medical officer at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital (Ann Arbor and Livingston, Mich.). The hospitalist and senior fellow of hospital medicine previously has been St. Joseph’s vice chair of internal medicine and medical director of care management and documentation integrity. Dr. Vandenberg has spent 20 years as an employee at St. Joseph’s.

Cristian Andrade, MD, has been elevated to vice president of medical affairs with St. Joseph’s Health (Syracuse, N.Y.). A 16-year veteran with St. Joseph’s, Dr. Andrade has been a hospitalist with the system since 2006, and most recently has served as chief of hospitalist services.

Dr. Andrade now will provide guidance focusing on improving length of stay, as well as staff governance, utilization review, and the hospitalist program in general.

Paul DeJac, MD, has received a promotion to chief of hospitalist medicine at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (Buffalo, N.Y.). Dr. DeJac was hired at Roswell Park in 2016, becoming lead hospitalist in 2017. He will look to boost professional development on the hospitalist team with a focus on improving patient care.

Independent Emergency Physicians (Farmington, Mich.), which provides hospitalist physicians, ED physicians, scribes, and more at a handful of hospitals in Michigan, has added urgent care facilities in Southfield, Mich., and Novi, Mich., to its portfolio. In addition, IEP has joined with Healthy Urgent Care to create a network of up to 15 urgent care centers in Southeast Michigan.

This is IEP’s first foray into urgent care. The company was founded in 1997 and practices at Ascension Health, Trinity Health, and Henry Ford Health System, covering four different hospitals.

Private hospitalist management provider Sound Physicians (Tacoma, Wash.) has grown once again, acquiring Indigo Health Partners (Traverse City, Mich.), one of Michigan’s largest private hospitalist groups. The new company will be known as Indigo, a division of Sound Inpatient Physicians.

Indigo’s approximately 150 providers are included in the transaction, which includes professionals in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities. Indigo was previously known as Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan, based out of Munson Medical Center.

Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, has been announced as Southeast Health Statera Network’s (Dothan, Ala.) director of physician integration, and chairman of the network’s Physicians Participation Committee. Dr. Skandhan is senior lead hospitalist with Southeast Health, where he has worked for nearly a decade. He also champions the medical group’s clinical documentation improvement faction.

One of just 10 hospitalists in the nation to receive Top Hospitalist recognition by the American College of Physicians in 2018, Dr. Skandhan is also an assistant professor at Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine and is one of Southeast Health’s Internal Medicine Residency Program’s core faculty members.

Ruby Sahoo, DO, has been promoted by Team Health (Knoxville, Tenn.) as regional performance director of its hospitalist services performance improvement team. Dr. Sahoo joined Team Health in 2016 and has most recently served as medical director and chief of staff at Grand Strand Medical Center (Myrtle Beach, S.C.).

Dr. Sahoo is a highly decorated internist and hospitalist. She was Team Health’s Medical Director of the Year for Hospital Medicine 2018, and a Frist Humanitarian Award winner in 2017. Additionally, Dr. Sahoo is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American College of Physicians, and the American Association of Physician Leadership.

David Vandenberg, MD, SFHM, recently was elevated to chief medical officer at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital (Ann Arbor and Livingston, Mich.). The hospitalist and senior fellow of hospital medicine previously has been St. Joseph’s vice chair of internal medicine and medical director of care management and documentation integrity. Dr. Vandenberg has spent 20 years as an employee at St. Joseph’s.

Cristian Andrade, MD, has been elevated to vice president of medical affairs with St. Joseph’s Health (Syracuse, N.Y.). A 16-year veteran with St. Joseph’s, Dr. Andrade has been a hospitalist with the system since 2006, and most recently has served as chief of hospitalist services.

Dr. Andrade now will provide guidance focusing on improving length of stay, as well as staff governance, utilization review, and the hospitalist program in general.

Paul DeJac, MD, has received a promotion to chief of hospitalist medicine at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (Buffalo, N.Y.). Dr. DeJac was hired at Roswell Park in 2016, becoming lead hospitalist in 2017. He will look to boost professional development on the hospitalist team with a focus on improving patient care.

Independent Emergency Physicians (Farmington, Mich.), which provides hospitalist physicians, ED physicians, scribes, and more at a handful of hospitals in Michigan, has added urgent care facilities in Southfield, Mich., and Novi, Mich., to its portfolio. In addition, IEP has joined with Healthy Urgent Care to create a network of up to 15 urgent care centers in Southeast Michigan.

This is IEP’s first foray into urgent care. The company was founded in 1997 and practices at Ascension Health, Trinity Health, and Henry Ford Health System, covering four different hospitals.

Private hospitalist management provider Sound Physicians (Tacoma, Wash.) has grown once again, acquiring Indigo Health Partners (Traverse City, Mich.), one of Michigan’s largest private hospitalist groups. The new company will be known as Indigo, a division of Sound Inpatient Physicians.

Indigo’s approximately 150 providers are included in the transaction, which includes professionals in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities. Indigo was previously known as Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan, based out of Munson Medical Center.

Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, has been announced as Southeast Health Statera Network’s (Dothan, Ala.) director of physician integration, and chairman of the network’s Physicians Participation Committee. Dr. Skandhan is senior lead hospitalist with Southeast Health, where he has worked for nearly a decade. He also champions the medical group’s clinical documentation improvement faction.

One of just 10 hospitalists in the nation to receive Top Hospitalist recognition by the American College of Physicians in 2018, Dr. Skandhan is also an assistant professor at Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine and is one of Southeast Health’s Internal Medicine Residency Program’s core faculty members.

Ruby Sahoo, DO, has been promoted by Team Health (Knoxville, Tenn.) as regional performance director of its hospitalist services performance improvement team. Dr. Sahoo joined Team Health in 2016 and has most recently served as medical director and chief of staff at Grand Strand Medical Center (Myrtle Beach, S.C.).

Dr. Sahoo is a highly decorated internist and hospitalist. She was Team Health’s Medical Director of the Year for Hospital Medicine 2018, and a Frist Humanitarian Award winner in 2017. Additionally, Dr. Sahoo is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American College of Physicians, and the American Association of Physician Leadership.

David Vandenberg, MD, SFHM, recently was elevated to chief medical officer at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital (Ann Arbor and Livingston, Mich.). The hospitalist and senior fellow of hospital medicine previously has been St. Joseph’s vice chair of internal medicine and medical director of care management and documentation integrity. Dr. Vandenberg has spent 20 years as an employee at St. Joseph’s.

Cristian Andrade, MD, has been elevated to vice president of medical affairs with St. Joseph’s Health (Syracuse, N.Y.). A 16-year veteran with St. Joseph’s, Dr. Andrade has been a hospitalist with the system since 2006, and most recently has served as chief of hospitalist services.

Dr. Andrade now will provide guidance focusing on improving length of stay, as well as staff governance, utilization review, and the hospitalist program in general.

Paul DeJac, MD, has received a promotion to chief of hospitalist medicine at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (Buffalo, N.Y.). Dr. DeJac was hired at Roswell Park in 2016, becoming lead hospitalist in 2017. He will look to boost professional development on the hospitalist team with a focus on improving patient care.

Independent Emergency Physicians (Farmington, Mich.), which provides hospitalist physicians, ED physicians, scribes, and more at a handful of hospitals in Michigan, has added urgent care facilities in Southfield, Mich., and Novi, Mich., to its portfolio. In addition, IEP has joined with Healthy Urgent Care to create a network of up to 15 urgent care centers in Southeast Michigan.

This is IEP’s first foray into urgent care. The company was founded in 1997 and practices at Ascension Health, Trinity Health, and Henry Ford Health System, covering four different hospitals.

Private hospitalist management provider Sound Physicians (Tacoma, Wash.) has grown once again, acquiring Indigo Health Partners (Traverse City, Mich.), one of Michigan’s largest private hospitalist groups. The new company will be known as Indigo, a division of Sound Inpatient Physicians.

Indigo’s approximately 150 providers are included in the transaction, which includes professionals in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities. Indigo was previously known as Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan, based out of Munson Medical Center.

PHM19: Mitigating the harm we cause learners in medical education

PHM19 session

Mitigating the harm we cause learners in medical education

Presenters

Benjamin Kinnear, MD, MEd

Andrew Olson, MD

Matthew Kelleher, MD, MEd

Session summary

Dr. Kinnear, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Kelleher expertly led this TED-Talk style session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019, convincing the audience that medical educators persistently harm the learners under their supervision.

Dr. Kinnear, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, opened the session noting that the path through medical school presently has a perverse focus on grades as a necessary achievement. As an expert in competency-based assessment, he asserted that the current learner assessment strategy is neither valid nor robust enough to indicate actual competence. Summary assessments presented throughout medical school are lacking continuous constructive feedback, leaving early residents in a state of shock when receiving corrective or negative assessments. He also noted that structurally many rotations create both team and patient discontinuity, leaving the learner with a feeling of detachment and limited ownership of the human patient under his/her/their care.

Dr. Olson of the University of Minnesota next described the need for the USMLE STEP 1 exam to be transitioned to a pass/fail endeavor. He cited the error of measurement of 24 points (i.e., the same test taker could have a 220 one day and a 244 the next) and the potential loss of valuable rotation experiences during the several-month period of intense study. He challenged audience members to complete an esoteric exam question to prove his point and asserted that many learners are lacking in humility, communication skills, and professionalism, and seek only the honors designation on rotations. He likened the experience of medical students on rotation and residents on service weeks to a series of first dates and affirmed the value of longitudinal learner-educator relationships.

Further, he outlined the detachment of learners from patient outcomes, demonstrated by frequent hand-offs and rotation transitions. Dr Olson also cited medical pedagogy as failing to meet the known needs of adult learners to engage in deliberate progressive practice, reflective practice, or to use concepts such as spacing or interleaving to reinforce knowledge.

Dr. Kelleher, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, ended the session by taking those in attendance on an imagined “what-if” journey where each of the wrongs currently done to early learners in medical education were corrected. This included engagement in daily reflection (5 minutes at a time), reporting system issues on rounds that had failed the patient, presenting learners with a CV of attending failures to reinforce the imperfection that is a reality in medicine, praising learners when they admit “they don’t know the answer” to a question posed on rounds, completing assessments in real time in the learner’s presence, rounding until specific feedback can be identified for each learner on the team, having a kiosk on each floor where ANY team member could provide feedback to learners, using cognitive science on rounds for teaching (i.e., Socratic) rather than pimping, modeling interprofessional teamwork daily using a culture of vulnerability rather than infallibility (i.e., airline culture), and by encouraging the attending to care for patients or complete tasks independently, showing the value of education over service and model ideal family-centered communication with the team.

One might wonder, if all of the above were accomplished at the request of our talented presenters, would a pass/fail USMLE world where medical education was learner centered and filled with longitudinal relationships with teams and patients, and outcomes were connected to education produce more engaged, knowledgeable, and holistic physicians? According to this team of presenters, yes.

Key takeaways

• Current processes in medical education are harming today’s adult learner.

• Harms include reliance on numerical rather than competency-based assessment, fragmented learning environments, focus on perfection rather than improvement, ignorance of updates in cognitive science for instructional methodology, and individualist rather than team-based learning.

• Reforms are needed to remedy harms in health professional education, including making USMLE pass/fail, creating a learning-centered rather than service-centered residency environment, encouraging longitudinal relationships between teacher and learner, and connecting education to clinical outcomes.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program, Minneapolis.

PHM19 session

Mitigating the harm we cause learners in medical education

Presenters

Benjamin Kinnear, MD, MEd

Andrew Olson, MD

Matthew Kelleher, MD, MEd

Session summary

Dr. Kinnear, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Kelleher expertly led this TED-Talk style session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019, convincing the audience that medical educators persistently harm the learners under their supervision.

Dr. Kinnear, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, opened the session noting that the path through medical school presently has a perverse focus on grades as a necessary achievement. As an expert in competency-based assessment, he asserted that the current learner assessment strategy is neither valid nor robust enough to indicate actual competence. Summary assessments presented throughout medical school are lacking continuous constructive feedback, leaving early residents in a state of shock when receiving corrective or negative assessments. He also noted that structurally many rotations create both team and patient discontinuity, leaving the learner with a feeling of detachment and limited ownership of the human patient under his/her/their care.

Dr. Olson of the University of Minnesota next described the need for the USMLE STEP 1 exam to be transitioned to a pass/fail endeavor. He cited the error of measurement of 24 points (i.e., the same test taker could have a 220 one day and a 244 the next) and the potential loss of valuable rotation experiences during the several-month period of intense study. He challenged audience members to complete an esoteric exam question to prove his point and asserted that many learners are lacking in humility, communication skills, and professionalism, and seek only the honors designation on rotations. He likened the experience of medical students on rotation and residents on service weeks to a series of first dates and affirmed the value of longitudinal learner-educator relationships.

Further, he outlined the detachment of learners from patient outcomes, demonstrated by frequent hand-offs and rotation transitions. Dr Olson also cited medical pedagogy as failing to meet the known needs of adult learners to engage in deliberate progressive practice, reflective practice, or to use concepts such as spacing or interleaving to reinforce knowledge.

Dr. Kelleher, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, ended the session by taking those in attendance on an imagined “what-if” journey where each of the wrongs currently done to early learners in medical education were corrected. This included engagement in daily reflection (5 minutes at a time), reporting system issues on rounds that had failed the patient, presenting learners with a CV of attending failures to reinforce the imperfection that is a reality in medicine, praising learners when they admit “they don’t know the answer” to a question posed on rounds, completing assessments in real time in the learner’s presence, rounding until specific feedback can be identified for each learner on the team, having a kiosk on each floor where ANY team member could provide feedback to learners, using cognitive science on rounds for teaching (i.e., Socratic) rather than pimping, modeling interprofessional teamwork daily using a culture of vulnerability rather than infallibility (i.e., airline culture), and by encouraging the attending to care for patients or complete tasks independently, showing the value of education over service and model ideal family-centered communication with the team.

One might wonder, if all of the above were accomplished at the request of our talented presenters, would a pass/fail USMLE world where medical education was learner centered and filled with longitudinal relationships with teams and patients, and outcomes were connected to education produce more engaged, knowledgeable, and holistic physicians? According to this team of presenters, yes.

Key takeaways

• Current processes in medical education are harming today’s adult learner.

• Harms include reliance on numerical rather than competency-based assessment, fragmented learning environments, focus on perfection rather than improvement, ignorance of updates in cognitive science for instructional methodology, and individualist rather than team-based learning.

• Reforms are needed to remedy harms in health professional education, including making USMLE pass/fail, creating a learning-centered rather than service-centered residency environment, encouraging longitudinal relationships between teacher and learner, and connecting education to clinical outcomes.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program, Minneapolis.

PHM19 session

Mitigating the harm we cause learners in medical education

Presenters

Benjamin Kinnear, MD, MEd

Andrew Olson, MD

Matthew Kelleher, MD, MEd

Session summary

Dr. Kinnear, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Kelleher expertly led this TED-Talk style session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019, convincing the audience that medical educators persistently harm the learners under their supervision.

Dr. Kinnear, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, opened the session noting that the path through medical school presently has a perverse focus on grades as a necessary achievement. As an expert in competency-based assessment, he asserted that the current learner assessment strategy is neither valid nor robust enough to indicate actual competence. Summary assessments presented throughout medical school are lacking continuous constructive feedback, leaving early residents in a state of shock when receiving corrective or negative assessments. He also noted that structurally many rotations create both team and patient discontinuity, leaving the learner with a feeling of detachment and limited ownership of the human patient under his/her/their care.

Dr. Olson of the University of Minnesota next described the need for the USMLE STEP 1 exam to be transitioned to a pass/fail endeavor. He cited the error of measurement of 24 points (i.e., the same test taker could have a 220 one day and a 244 the next) and the potential loss of valuable rotation experiences during the several-month period of intense study. He challenged audience members to complete an esoteric exam question to prove his point and asserted that many learners are lacking in humility, communication skills, and professionalism, and seek only the honors designation on rotations. He likened the experience of medical students on rotation and residents on service weeks to a series of first dates and affirmed the value of longitudinal learner-educator relationships.

Further, he outlined the detachment of learners from patient outcomes, demonstrated by frequent hand-offs and rotation transitions. Dr Olson also cited medical pedagogy as failing to meet the known needs of adult learners to engage in deliberate progressive practice, reflective practice, or to use concepts such as spacing or interleaving to reinforce knowledge.

Dr. Kelleher, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, ended the session by taking those in attendance on an imagined “what-if” journey where each of the wrongs currently done to early learners in medical education were corrected. This included engagement in daily reflection (5 minutes at a time), reporting system issues on rounds that had failed the patient, presenting learners with a CV of attending failures to reinforce the imperfection that is a reality in medicine, praising learners when they admit “they don’t know the answer” to a question posed on rounds, completing assessments in real time in the learner’s presence, rounding until specific feedback can be identified for each learner on the team, having a kiosk on each floor where ANY team member could provide feedback to learners, using cognitive science on rounds for teaching (i.e., Socratic) rather than pimping, modeling interprofessional teamwork daily using a culture of vulnerability rather than infallibility (i.e., airline culture), and by encouraging the attending to care for patients or complete tasks independently, showing the value of education over service and model ideal family-centered communication with the team.

One might wonder, if all of the above were accomplished at the request of our talented presenters, would a pass/fail USMLE world where medical education was learner centered and filled with longitudinal relationships with teams and patients, and outcomes were connected to education produce more engaged, knowledgeable, and holistic physicians? According to this team of presenters, yes.

Key takeaways

• Current processes in medical education are harming today’s adult learner.

• Harms include reliance on numerical rather than competency-based assessment, fragmented learning environments, focus on perfection rather than improvement, ignorance of updates in cognitive science for instructional methodology, and individualist rather than team-based learning.

• Reforms are needed to remedy harms in health professional education, including making USMLE pass/fail, creating a learning-centered rather than service-centered residency environment, encouraging longitudinal relationships between teacher and learner, and connecting education to clinical outcomes.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program, Minneapolis.

The SHM Fellow designation: Class of 2020

Society invites applicants in multiple membership categories

In an industry brimming with opportunity and ongoing transformation, it is easy to feel indecisive about your next professional step when ample career paths exist in hospital medicine.

Yingkei Hui, MD, FHM, is an academic hospitalist at St. Vincent Indianapolis, and a Society of Hospital Medicine member since 2015. Seeking to set herself apart as an aspiring patient safety and quality improvement leader while continuing her professional development, she looked to SHM’s Fellow designation as the next piece of her career puzzle.

With more than 14 years of experience in the health care industry, Dr. Hui fell in love with the specialty because of its flexibility and patient-centric focus.

“I have a broad interest in medicine and want to learn everything under the larger umbrella of medicine,” she said. “I also find myself deeply in love with hospital medicine because it provides me with the opportunity to participate in various hospital committees and allows me to enjoy my practice from a macroscopic view of U.S. health care transformation – especially given the popular value-based patient care approach from recent years.”

Dr. Hui’s breadth of experience has allowed her to gain a unique set of perspectives and experiences from international and domestic standpoints. From attending medical school at the Chinese University of Hong Kong to completing her residency on the east coast at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia – part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System – Dr. Hui has held active medical licenses in New Jersey and currently, Indiana.

“SHM’s Fellow designation allows me to challenge myself in setting my career goal as a patient safety and quality improvement leader in my program,” she said. “It means a lot to me as it is a stand-out recognition of my participation in and contribution to patient care in my institution.”

When asked about the most rewarding aspect of being a part of the hospital medicine community, Dr. Hui identified “satisfaction in the teaching role.” She said she is “motivated by the holistic care for the patients, the integration of medical knowledge and coordination of care, and also the opportunity to conduct quality improvement projects.”

Motivated by her colleagues, Dr. Hui credits SHM with providing her with the inspiration and tools to push herself and advance her career in hospital medicine.

“I enjoy immersing myself in SHM’s patient safety and quality improvement resources; they are perfect for frontline hospitalists and also provide CME [continuing medical education],” she noted. “My previous medical directors were all Senior Fellows; they are my role models and continue to inspire me throughout my career.”

Dr. Hui also said that networking within the SHM community has been encouraging. “I’ve met talented Fellows at a number of hospital medicine annual conferences who have inspired me in the areas of patient care, education, and health promotion,” she explained. “Some of them have extensive publications; they are truly amazing physicians. SHM’s Annual Conference provides great opportunities for networking.”

As Dr. Hui continues to progress her career in hospital medicine, she believes that communication is a key pillar in her success. “Be a true listener and fill your heart with compassion, empathy, and courage,” she said. “Recognize your role as the enabler for the patients to improve their health.”

Completing her Master’s degree in population health management at Johns Hopkins University and expecting to graduate in May 2020, Dr. Hui is the designer of system safety (comprising patient safety, second victim safety, quality improvement, and just culture) in the academic setting of her residency program. She is also chairing a pioneer project for the St. Vincent IM residency program.

Dr. Hui plans to apply for a Senior Fellow designation with SHM in the future.

If you would like to join Dr. Hui and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in taking your career to the next level, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows: Class of 2020. Applications are open until Nov. 29 of this year. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and improving the quality of patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Society invites applicants in multiple membership categories

Society invites applicants in multiple membership categories

In an industry brimming with opportunity and ongoing transformation, it is easy to feel indecisive about your next professional step when ample career paths exist in hospital medicine.

Yingkei Hui, MD, FHM, is an academic hospitalist at St. Vincent Indianapolis, and a Society of Hospital Medicine member since 2015. Seeking to set herself apart as an aspiring patient safety and quality improvement leader while continuing her professional development, she looked to SHM’s Fellow designation as the next piece of her career puzzle.

With more than 14 years of experience in the health care industry, Dr. Hui fell in love with the specialty because of its flexibility and patient-centric focus.

“I have a broad interest in medicine and want to learn everything under the larger umbrella of medicine,” she said. “I also find myself deeply in love with hospital medicine because it provides me with the opportunity to participate in various hospital committees and allows me to enjoy my practice from a macroscopic view of U.S. health care transformation – especially given the popular value-based patient care approach from recent years.”

Dr. Hui’s breadth of experience has allowed her to gain a unique set of perspectives and experiences from international and domestic standpoints. From attending medical school at the Chinese University of Hong Kong to completing her residency on the east coast at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia – part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System – Dr. Hui has held active medical licenses in New Jersey and currently, Indiana.

“SHM’s Fellow designation allows me to challenge myself in setting my career goal as a patient safety and quality improvement leader in my program,” she said. “It means a lot to me as it is a stand-out recognition of my participation in and contribution to patient care in my institution.”

When asked about the most rewarding aspect of being a part of the hospital medicine community, Dr. Hui identified “satisfaction in the teaching role.” She said she is “motivated by the holistic care for the patients, the integration of medical knowledge and coordination of care, and also the opportunity to conduct quality improvement projects.”

Motivated by her colleagues, Dr. Hui credits SHM with providing her with the inspiration and tools to push herself and advance her career in hospital medicine.

“I enjoy immersing myself in SHM’s patient safety and quality improvement resources; they are perfect for frontline hospitalists and also provide CME [continuing medical education],” she noted. “My previous medical directors were all Senior Fellows; they are my role models and continue to inspire me throughout my career.”

Dr. Hui also said that networking within the SHM community has been encouraging. “I’ve met talented Fellows at a number of hospital medicine annual conferences who have inspired me in the areas of patient care, education, and health promotion,” she explained. “Some of them have extensive publications; they are truly amazing physicians. SHM’s Annual Conference provides great opportunities for networking.”

As Dr. Hui continues to progress her career in hospital medicine, she believes that communication is a key pillar in her success. “Be a true listener and fill your heart with compassion, empathy, and courage,” she said. “Recognize your role as the enabler for the patients to improve their health.”

Completing her Master’s degree in population health management at Johns Hopkins University and expecting to graduate in May 2020, Dr. Hui is the designer of system safety (comprising patient safety, second victim safety, quality improvement, and just culture) in the academic setting of her residency program. She is also chairing a pioneer project for the St. Vincent IM residency program.

Dr. Hui plans to apply for a Senior Fellow designation with SHM in the future.

If you would like to join Dr. Hui and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in taking your career to the next level, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows: Class of 2020. Applications are open until Nov. 29 of this year. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and improving the quality of patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

In an industry brimming with opportunity and ongoing transformation, it is easy to feel indecisive about your next professional step when ample career paths exist in hospital medicine.

Yingkei Hui, MD, FHM, is an academic hospitalist at St. Vincent Indianapolis, and a Society of Hospital Medicine member since 2015. Seeking to set herself apart as an aspiring patient safety and quality improvement leader while continuing her professional development, she looked to SHM’s Fellow designation as the next piece of her career puzzle.

With more than 14 years of experience in the health care industry, Dr. Hui fell in love with the specialty because of its flexibility and patient-centric focus.

“I have a broad interest in medicine and want to learn everything under the larger umbrella of medicine,” she said. “I also find myself deeply in love with hospital medicine because it provides me with the opportunity to participate in various hospital committees and allows me to enjoy my practice from a macroscopic view of U.S. health care transformation – especially given the popular value-based patient care approach from recent years.”

Dr. Hui’s breadth of experience has allowed her to gain a unique set of perspectives and experiences from international and domestic standpoints. From attending medical school at the Chinese University of Hong Kong to completing her residency on the east coast at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia – part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System – Dr. Hui has held active medical licenses in New Jersey and currently, Indiana.

“SHM’s Fellow designation allows me to challenge myself in setting my career goal as a patient safety and quality improvement leader in my program,” she said. “It means a lot to me as it is a stand-out recognition of my participation in and contribution to patient care in my institution.”

When asked about the most rewarding aspect of being a part of the hospital medicine community, Dr. Hui identified “satisfaction in the teaching role.” She said she is “motivated by the holistic care for the patients, the integration of medical knowledge and coordination of care, and also the opportunity to conduct quality improvement projects.”

Motivated by her colleagues, Dr. Hui credits SHM with providing her with the inspiration and tools to push herself and advance her career in hospital medicine.

“I enjoy immersing myself in SHM’s patient safety and quality improvement resources; they are perfect for frontline hospitalists and also provide CME [continuing medical education],” she noted. “My previous medical directors were all Senior Fellows; they are my role models and continue to inspire me throughout my career.”

Dr. Hui also said that networking within the SHM community has been encouraging. “I’ve met talented Fellows at a number of hospital medicine annual conferences who have inspired me in the areas of patient care, education, and health promotion,” she explained. “Some of them have extensive publications; they are truly amazing physicians. SHM’s Annual Conference provides great opportunities for networking.”

As Dr. Hui continues to progress her career in hospital medicine, she believes that communication is a key pillar in her success. “Be a true listener and fill your heart with compassion, empathy, and courage,” she said. “Recognize your role as the enabler for the patients to improve their health.”

Completing her Master’s degree in population health management at Johns Hopkins University and expecting to graduate in May 2020, Dr. Hui is the designer of system safety (comprising patient safety, second victim safety, quality improvement, and just culture) in the academic setting of her residency program. She is also chairing a pioneer project for the St. Vincent IM residency program.

Dr. Hui plans to apply for a Senior Fellow designation with SHM in the future.

If you would like to join Dr. Hui and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in taking your career to the next level, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows: Class of 2020. Applications are open until Nov. 29 of this year. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and improving the quality of patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PHM 19: PREP yourself for the PHM boards

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

NAM offers recommendations to fight clinician burnout

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

The growing NP and PA workforce in hospital medicine

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

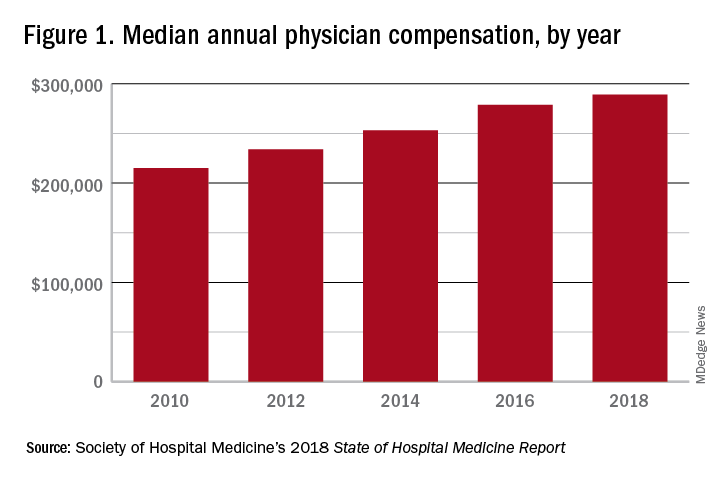

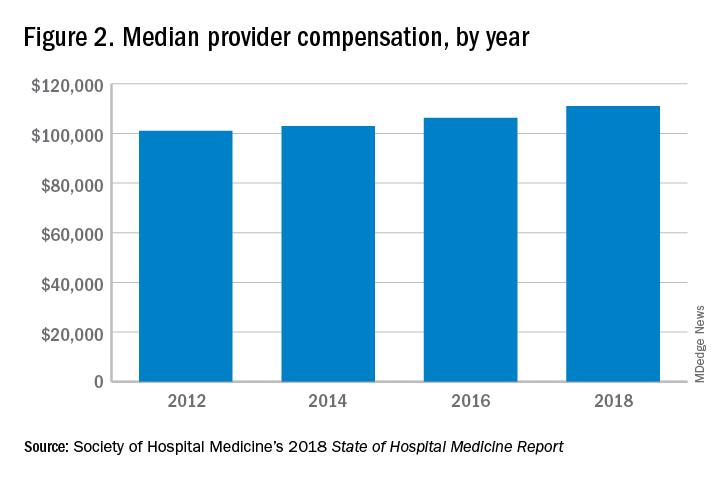

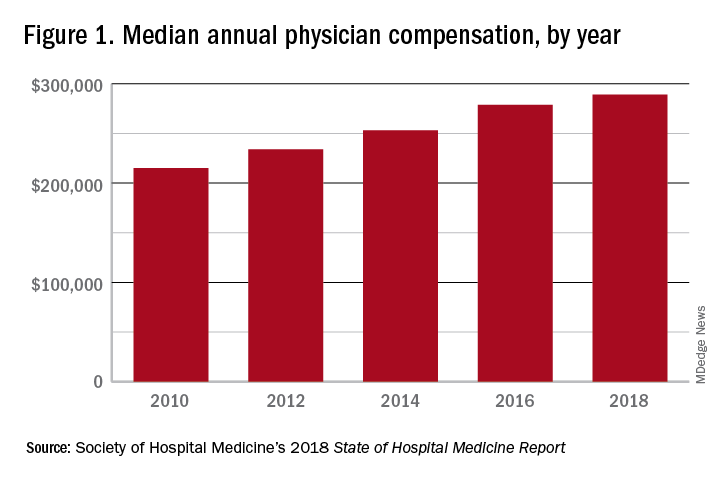

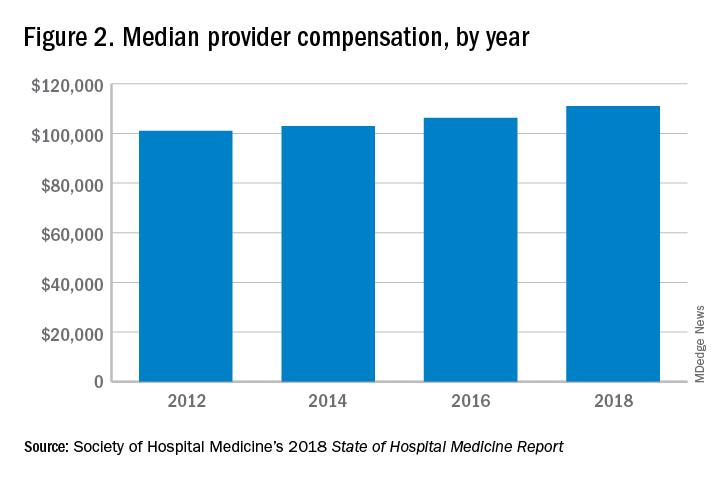

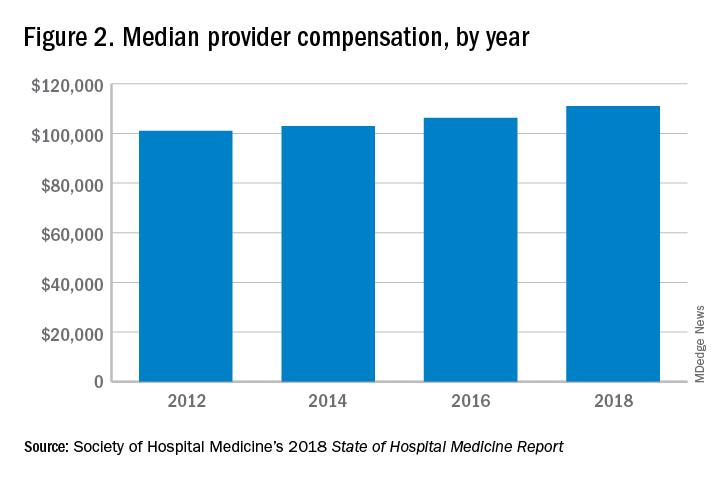

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

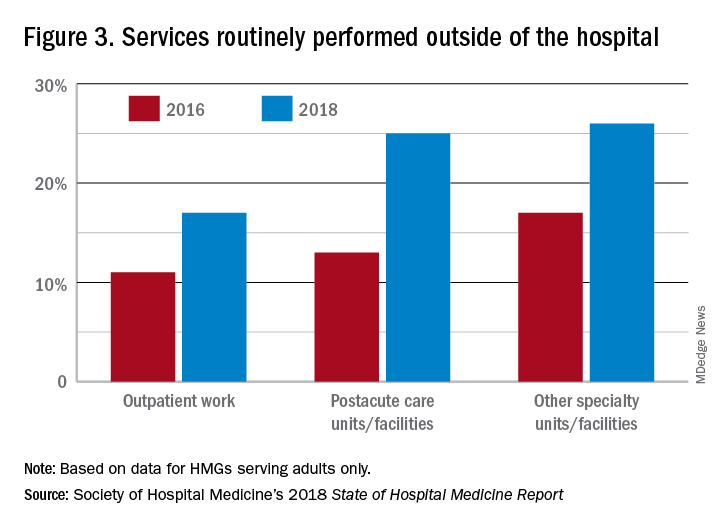

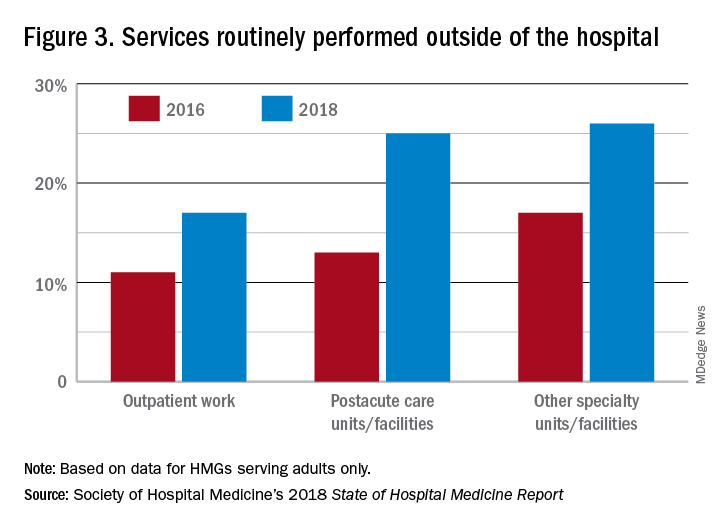

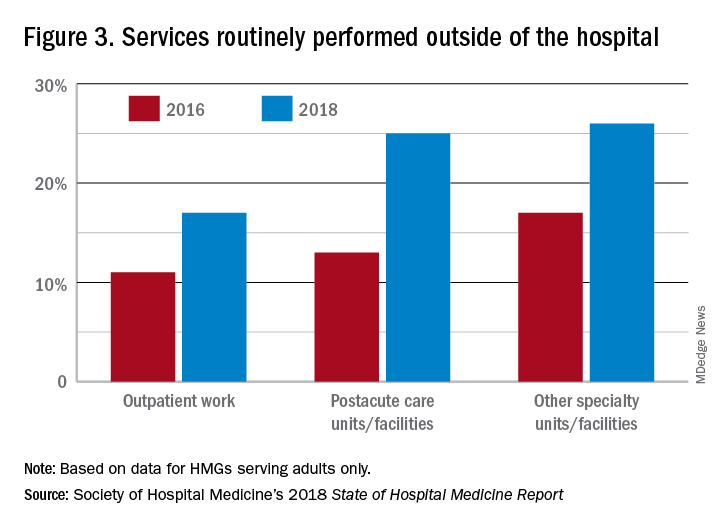

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.