User login

15 Things Dermatologists Think Hospitalists Need to Know

- Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

- Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

- Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

- Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

- Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

- Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

- Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

- Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

- Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

- Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

- Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

- Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesions on the skin.

- Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer.

- Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

- Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

Dermatologic diseases tend to receive little attention at most U.S. medical schools—typically only several days of lectures or a few weeks of clinical exposure.

“Not surprisingly, many general practitioners may feel unprepared to address hospitalized patients with challenging dermatologic findings,” says R. Samuel Hopkins, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and assistant residency program director at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

Few studies have examined the quality of inpatient dermatologic care. One study, a retrospective chart review at a Midwestern university hospital, found that the primary ward team submitted an accurate dermatologic diagnosis in only 23.9% of cases. Meanwhile, consultation with a dermatologist led to a change or addition to treatment in 77% of patients (Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(2):12).

“Given that medical schools may not be able to dedicate more time to managing dermatologic conditions, the burden of education may fall on post-graduate programs and continuing medical education to fill this gap,” Dr. Hopkins says. To further complicate matters, “it is difficult in many hospitals to obtain a dermatology consult on an inpatient, reflecting the limited access hospitalists often have to dermatologists.”

The most frequently encountered dermatologic conditions in the hospital setting are drug eruptions and skin infections. Dermatitis is the most misdiagnosed condition by nondermatologists in hospitals, says Russell Vinik, MD, co-director of the hospitalist group at the University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

The majority of skin issues don’t require a dermatologist’s input, but some do. “Clearly, there’s also the rash that we just don’t know what it is,” Dr. Vinik says. When in doubt, it’s best to err on the safe side and call the specialist.

Here’s how to assess whether to manage a dermatologic case yourself, or how to involve a dermatologist for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. In general, Dr. Hopkins says, “Whether one can handle a case on their own or not is a case-by-case decision by the hospitalist based on their comfort with their diagnosis and management.”

Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

“Very often, patients with skin diseases are given a specific diagnosis without consideration of mimickers,” says Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“Cellulitis is a great example. People will come in with hot, red skin and be diagnosed with and treated for cellulitis but really have stasis dermatitis, Lyme [disease], gout, et cetera,” says Dr. Kroshinsky, who also is director of pediatric dermatology and director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The clinical picture of warm, red, tender skin can fit many conditions but is most often called cellulitis by nondermatologists,” she explains. “It’s not clear why, but I would suspect this is because cellulitis is one of the few dermatologic conditions taught in medical school, while the mimickers get less attention.”

Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

This would increase your knowledge of skin conditions affecting hospitalized patients, Dr. Kroshinsky says. If there is a dermatologic consultant for your hospital, work closely with this specialist until you feel comfortable making diagnoses and incorporating treatment plans.

Similarly, if you are a resident who is interested in a career in hospital medicine, consider doing a rotation in dermatology.

Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

This keeps your mind open to differential diagnoses for a given situation that you may encounter in the hospital setting. A more comprehensive book or online reference can be helpful to peruse after seeing a patient with a particular rash, Dr. Kroshinsky says.

Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

When a specialist isn’t available on site, the phone communication is vital to the specialist. This includes familiarizing yourself with some of the more life-threatening dermatologic problems, such as drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions. It will be easier to recognize when an urgent dermatologic consultation is required. Sometimes this is necessary when a patient doesn’t respond to treatment for a reasonable and presumed diagnosis—when one condition seems to mimic the symptoms of another, says Lindy Fox, MD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California at San Francisco and director of its hospital dermatology consultation service.

Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

In fact, there is a very large differential diagnosis for intertriginous eruptions, Dr. Fox says. Perform a KOH test (potassium hydroxide) and fungal cultures on intertriginous eruptions. If no fungus is identified or the patient is not responding appropriately to therapy, call for a dermatologic consultation.

Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

It is typically seven to 10 days post-exposure that a drug eruption develops, Dr. Fox says. He suggests making a drug chart to highlight dates of medication administration. This helps pinpoint the most likely culprit based on timing and the probability that a certain drug may induce cutaneous eruptions. Correct identification of the type of drug eruption (e.g. simple drug eruption vs. hypersensitivity vs. potentially deadly Stevens-Johnson syndrome) is important.

Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

There are many different causes of skin ulcers. Trauma, infections, and even malignancies can present as open wounds. Leg ulcers may be due to venous stasis, but they also can be caused by arterial insufficiency, vasculitis, and other conditions. A dermatologist might opt to perform a skin biopsy to help diagnose the lesion.

“Wound-care nurses can be very helpful in managing skin lesions, but they do not always have the experience needed to correctly diagnose the underlying problem,” says Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington. “If you’re thinking of calling the wound-care nurse, think of calling the dermatologist first.”

Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

“It’s really important to provide enough medicine,” Dr. Schwarzenberger says. Typically, a patient will receive a small tube, apply the contents, and find that “it’s enough medicine to cover their body once. This doesn’t work if you intended to have the patient apply it all over for two weeks.”

It takes, on average, 30 g of a topical medication to cover the body once. With topical steroids, prescribing an insufficient quantity “dooms your therapy to failure.”

Allergic reactions from these medications are rare, and some insurance companies charge the same regardless of the size. Prescribing a small amount initially might incur an additional expense for the patient.

Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

“These symptoms can be associated with potentially deadly toxic epidermal necrolysis,” says Daniel Aires, MD, JD, director of the division of dermatology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, Kan. “Consult dermatology immediately. The sooner treatment is begun, the better the odds of survival.”

If a rash involves the eye, call an ophthalmologist and a dermatologist. “Eyes are more likely than skin to develop chronic complications after resolution of an acute condition,” he says.

For a rash involving primarily the mouth, call an otolaryngologist, a dentist, or both, as well as a dermatologist. These specialists are more skilled in visualizing and treating oral conditions.

Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

These blistering conditions require urgent diagnosis and treatment, so a dermatologist’s expertise is needed quickly, Dr. Aires says. Even without the presence of blisters, a single region of the skin or “dermatome” gives pause for concern.

“This could be a sign of zoster, which is especially dangerous in immunosuppressed or otherwise debilitated patients,” he cautions. “Either perform a culture and begin treatment, or consult dermatology, or do both.”

Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

This may be due to scabies infestation. “Scabies can spread rapidly throughout a hospital ward,” Dr. Aires says. What to do: Scrape for scabies, consider a trial of topical treatment, and consult a dermatologist if you’re unsure.

Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesionscon the skin.

They warrant suspicion of such conditions as vasculitis, hypercoaguable states, and disseminated angiotropic infections, says Dr. Hopkins of Oregon Health & Science University. “The shape and size of purpuric skin lesions help determine the etiology. A few characteristic examples include papular purpura and retiform purpura. Papular purpura [raised purpuric papules] may suggest vasculitis. Purpura that forms net-like patches is called retiform purpura and suggests a vaso-occlusive process, such as from a hypercoaguable state, embolic phenomena, or calciphylaxis.”

13 Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer. These conditions “are more easily addressed in a clinic, as opposed to in a hospital, where the patient is lying in a bed feeling ill with IV tubes in place,” Dr. Aires says. “It also reflects respect for the dermatologist’s time. Inpatient dermatology can be pretty busy, so it’s preferable to consult primarily for urgent skin issues.” Consultations can be costly, too, and most patients would rather avoid additional medical bills.

Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

Although it is not harmful, “it is not usually a great choice for typical ‘dermatophyte’ fungal infections, such as athlete’s foot and ‘jock itch,’” Dr. Aires says. “Over-the-counter Lamisil is better, particularly following daily use of 10-minute soaks in 50-50 vinegar-water. Even for yeast infections, miconazole is better than clotrimazole.”

As for betamethasone, this “component is way too strong for the groin area and can cause atrophy or worse,” he says.

—Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

By heeding this advice, patients are less likely to return to the ED for skin conditions that can be managed in an office, says Kirsten Flynn, MD, a dermatologist at Banner Health Center in Sun City West, Ariz. Inpatient admissions by dermatologists have been decreasing over the years. Most patients with skin diseases or cutaneous manifestations of systemic illnesses are admitted to hospitals by other physicians.

“Many dermatologists are happy to fit in urgent consults in their clinics. Drug eruptions are by far the most common consultation request,” says Dr. Flynn, who notes that high-dose IV steroids can cause complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel perforation, opportunistic infections, and exacerbation of underlying diseases. “In most cases, removing the offending agent and providing supportive care is the best option.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York.

- Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

- Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

- Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

- Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

- Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

- Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

- Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

- Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

- Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

- Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

- Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

- Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesions on the skin.

- Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer.

- Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

- Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

Dermatologic diseases tend to receive little attention at most U.S. medical schools—typically only several days of lectures or a few weeks of clinical exposure.

“Not surprisingly, many general practitioners may feel unprepared to address hospitalized patients with challenging dermatologic findings,” says R. Samuel Hopkins, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and assistant residency program director at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

Few studies have examined the quality of inpatient dermatologic care. One study, a retrospective chart review at a Midwestern university hospital, found that the primary ward team submitted an accurate dermatologic diagnosis in only 23.9% of cases. Meanwhile, consultation with a dermatologist led to a change or addition to treatment in 77% of patients (Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(2):12).

“Given that medical schools may not be able to dedicate more time to managing dermatologic conditions, the burden of education may fall on post-graduate programs and continuing medical education to fill this gap,” Dr. Hopkins says. To further complicate matters, “it is difficult in many hospitals to obtain a dermatology consult on an inpatient, reflecting the limited access hospitalists often have to dermatologists.”

The most frequently encountered dermatologic conditions in the hospital setting are drug eruptions and skin infections. Dermatitis is the most misdiagnosed condition by nondermatologists in hospitals, says Russell Vinik, MD, co-director of the hospitalist group at the University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

The majority of skin issues don’t require a dermatologist’s input, but some do. “Clearly, there’s also the rash that we just don’t know what it is,” Dr. Vinik says. When in doubt, it’s best to err on the safe side and call the specialist.

Here’s how to assess whether to manage a dermatologic case yourself, or how to involve a dermatologist for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. In general, Dr. Hopkins says, “Whether one can handle a case on their own or not is a case-by-case decision by the hospitalist based on their comfort with their diagnosis and management.”

Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

“Very often, patients with skin diseases are given a specific diagnosis without consideration of mimickers,” says Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“Cellulitis is a great example. People will come in with hot, red skin and be diagnosed with and treated for cellulitis but really have stasis dermatitis, Lyme [disease], gout, et cetera,” says Dr. Kroshinsky, who also is director of pediatric dermatology and director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The clinical picture of warm, red, tender skin can fit many conditions but is most often called cellulitis by nondermatologists,” she explains. “It’s not clear why, but I would suspect this is because cellulitis is one of the few dermatologic conditions taught in medical school, while the mimickers get less attention.”

Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

This would increase your knowledge of skin conditions affecting hospitalized patients, Dr. Kroshinsky says. If there is a dermatologic consultant for your hospital, work closely with this specialist until you feel comfortable making diagnoses and incorporating treatment plans.

Similarly, if you are a resident who is interested in a career in hospital medicine, consider doing a rotation in dermatology.

Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

This keeps your mind open to differential diagnoses for a given situation that you may encounter in the hospital setting. A more comprehensive book or online reference can be helpful to peruse after seeing a patient with a particular rash, Dr. Kroshinsky says.

Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

When a specialist isn’t available on site, the phone communication is vital to the specialist. This includes familiarizing yourself with some of the more life-threatening dermatologic problems, such as drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions. It will be easier to recognize when an urgent dermatologic consultation is required. Sometimes this is necessary when a patient doesn’t respond to treatment for a reasonable and presumed diagnosis—when one condition seems to mimic the symptoms of another, says Lindy Fox, MD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California at San Francisco and director of its hospital dermatology consultation service.

Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

In fact, there is a very large differential diagnosis for intertriginous eruptions, Dr. Fox says. Perform a KOH test (potassium hydroxide) and fungal cultures on intertriginous eruptions. If no fungus is identified or the patient is not responding appropriately to therapy, call for a dermatologic consultation.

Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

It is typically seven to 10 days post-exposure that a drug eruption develops, Dr. Fox says. He suggests making a drug chart to highlight dates of medication administration. This helps pinpoint the most likely culprit based on timing and the probability that a certain drug may induce cutaneous eruptions. Correct identification of the type of drug eruption (e.g. simple drug eruption vs. hypersensitivity vs. potentially deadly Stevens-Johnson syndrome) is important.

Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

There are many different causes of skin ulcers. Trauma, infections, and even malignancies can present as open wounds. Leg ulcers may be due to venous stasis, but they also can be caused by arterial insufficiency, vasculitis, and other conditions. A dermatologist might opt to perform a skin biopsy to help diagnose the lesion.

“Wound-care nurses can be very helpful in managing skin lesions, but they do not always have the experience needed to correctly diagnose the underlying problem,” says Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington. “If you’re thinking of calling the wound-care nurse, think of calling the dermatologist first.”

Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

“It’s really important to provide enough medicine,” Dr. Schwarzenberger says. Typically, a patient will receive a small tube, apply the contents, and find that “it’s enough medicine to cover their body once. This doesn’t work if you intended to have the patient apply it all over for two weeks.”

It takes, on average, 30 g of a topical medication to cover the body once. With topical steroids, prescribing an insufficient quantity “dooms your therapy to failure.”

Allergic reactions from these medications are rare, and some insurance companies charge the same regardless of the size. Prescribing a small amount initially might incur an additional expense for the patient.

Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

“These symptoms can be associated with potentially deadly toxic epidermal necrolysis,” says Daniel Aires, MD, JD, director of the division of dermatology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, Kan. “Consult dermatology immediately. The sooner treatment is begun, the better the odds of survival.”

If a rash involves the eye, call an ophthalmologist and a dermatologist. “Eyes are more likely than skin to develop chronic complications after resolution of an acute condition,” he says.

For a rash involving primarily the mouth, call an otolaryngologist, a dentist, or both, as well as a dermatologist. These specialists are more skilled in visualizing and treating oral conditions.

Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

These blistering conditions require urgent diagnosis and treatment, so a dermatologist’s expertise is needed quickly, Dr. Aires says. Even without the presence of blisters, a single region of the skin or “dermatome” gives pause for concern.

“This could be a sign of zoster, which is especially dangerous in immunosuppressed or otherwise debilitated patients,” he cautions. “Either perform a culture and begin treatment, or consult dermatology, or do both.”

Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

This may be due to scabies infestation. “Scabies can spread rapidly throughout a hospital ward,” Dr. Aires says. What to do: Scrape for scabies, consider a trial of topical treatment, and consult a dermatologist if you’re unsure.

Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesionscon the skin.

They warrant suspicion of such conditions as vasculitis, hypercoaguable states, and disseminated angiotropic infections, says Dr. Hopkins of Oregon Health & Science University. “The shape and size of purpuric skin lesions help determine the etiology. A few characteristic examples include papular purpura and retiform purpura. Papular purpura [raised purpuric papules] may suggest vasculitis. Purpura that forms net-like patches is called retiform purpura and suggests a vaso-occlusive process, such as from a hypercoaguable state, embolic phenomena, or calciphylaxis.”

13 Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer. These conditions “are more easily addressed in a clinic, as opposed to in a hospital, where the patient is lying in a bed feeling ill with IV tubes in place,” Dr. Aires says. “It also reflects respect for the dermatologist’s time. Inpatient dermatology can be pretty busy, so it’s preferable to consult primarily for urgent skin issues.” Consultations can be costly, too, and most patients would rather avoid additional medical bills.

Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

Although it is not harmful, “it is not usually a great choice for typical ‘dermatophyte’ fungal infections, such as athlete’s foot and ‘jock itch,’” Dr. Aires says. “Over-the-counter Lamisil is better, particularly following daily use of 10-minute soaks in 50-50 vinegar-water. Even for yeast infections, miconazole is better than clotrimazole.”

As for betamethasone, this “component is way too strong for the groin area and can cause atrophy or worse,” he says.

—Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

By heeding this advice, patients are less likely to return to the ED for skin conditions that can be managed in an office, says Kirsten Flynn, MD, a dermatologist at Banner Health Center in Sun City West, Ariz. Inpatient admissions by dermatologists have been decreasing over the years. Most patients with skin diseases or cutaneous manifestations of systemic illnesses are admitted to hospitals by other physicians.

“Many dermatologists are happy to fit in urgent consults in their clinics. Drug eruptions are by far the most common consultation request,” says Dr. Flynn, who notes that high-dose IV steroids can cause complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel perforation, opportunistic infections, and exacerbation of underlying diseases. “In most cases, removing the offending agent and providing supportive care is the best option.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York.

- Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

- Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

- Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

- Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

- Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

- Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

- Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

- Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

- Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

- Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

- Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

- Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesions on the skin.

- Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer.

- Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

- Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

Dermatologic diseases tend to receive little attention at most U.S. medical schools—typically only several days of lectures or a few weeks of clinical exposure.

“Not surprisingly, many general practitioners may feel unprepared to address hospitalized patients with challenging dermatologic findings,” says R. Samuel Hopkins, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and assistant residency program director at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

Few studies have examined the quality of inpatient dermatologic care. One study, a retrospective chart review at a Midwestern university hospital, found that the primary ward team submitted an accurate dermatologic diagnosis in only 23.9% of cases. Meanwhile, consultation with a dermatologist led to a change or addition to treatment in 77% of patients (Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(2):12).

“Given that medical schools may not be able to dedicate more time to managing dermatologic conditions, the burden of education may fall on post-graduate programs and continuing medical education to fill this gap,” Dr. Hopkins says. To further complicate matters, “it is difficult in many hospitals to obtain a dermatology consult on an inpatient, reflecting the limited access hospitalists often have to dermatologists.”

The most frequently encountered dermatologic conditions in the hospital setting are drug eruptions and skin infections. Dermatitis is the most misdiagnosed condition by nondermatologists in hospitals, says Russell Vinik, MD, co-director of the hospitalist group at the University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

The majority of skin issues don’t require a dermatologist’s input, but some do. “Clearly, there’s also the rash that we just don’t know what it is,” Dr. Vinik says. When in doubt, it’s best to err on the safe side and call the specialist.

Here’s how to assess whether to manage a dermatologic case yourself, or how to involve a dermatologist for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. In general, Dr. Hopkins says, “Whether one can handle a case on their own or not is a case-by-case decision by the hospitalist based on their comfort with their diagnosis and management.”

Maintain a broader range of differential diagnoses before ruling in or out something more concrete.

“Very often, patients with skin diseases are given a specific diagnosis without consideration of mimickers,” says Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“Cellulitis is a great example. People will come in with hot, red skin and be diagnosed with and treated for cellulitis but really have stasis dermatitis, Lyme [disease], gout, et cetera,” says Dr. Kroshinsky, who also is director of pediatric dermatology and director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The clinical picture of warm, red, tender skin can fit many conditions but is most often called cellulitis by nondermatologists,” she explains. “It’s not clear why, but I would suspect this is because cellulitis is one of the few dermatologic conditions taught in medical school, while the mimickers get less attention.”

Attend dermatology lectures as part of primary care’s continuing medical education courses.

This would increase your knowledge of skin conditions affecting hospitalized patients, Dr. Kroshinsky says. If there is a dermatologic consultant for your hospital, work closely with this specialist until you feel comfortable making diagnoses and incorporating treatment plans.

Similarly, if you are a resident who is interested in a career in hospital medicine, consider doing a rotation in dermatology.

Review a good basic dermatology atlas from time to time.

This keeps your mind open to differential diagnoses for a given situation that you may encounter in the hospital setting. A more comprehensive book or online reference can be helpful to peruse after seeing a patient with a particular rash, Dr. Kroshinsky says.

Learn to correctly describe lesions to a dermatologist by phone.

When a specialist isn’t available on site, the phone communication is vital to the specialist. This includes familiarizing yourself with some of the more life-threatening dermatologic problems, such as drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions. It will be easier to recognize when an urgent dermatologic consultation is required. Sometimes this is necessary when a patient doesn’t respond to treatment for a reasonable and presumed diagnosis—when one condition seems to mimic the symptoms of another, says Lindy Fox, MD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California at San Francisco and director of its hospital dermatology consultation service.

Don’t assume that groin rashes are all fungal.

In fact, there is a very large differential diagnosis for intertriginous eruptions, Dr. Fox says. Perform a KOH test (potassium hydroxide) and fungal cultures on intertriginous eruptions. If no fungus is identified or the patient is not responding appropriately to therapy, call for a dermatologic consultation.

Don’t mistakenly associate a drug-related reaction with a medication given one to two days before the onset of a rash.

It is typically seven to 10 days post-exposure that a drug eruption develops, Dr. Fox says. He suggests making a drug chart to highlight dates of medication administration. This helps pinpoint the most likely culprit based on timing and the probability that a certain drug may induce cutaneous eruptions. Correct identification of the type of drug eruption (e.g. simple drug eruption vs. hypersensitivity vs. potentially deadly Stevens-Johnson syndrome) is important.

Consider involving a dermatologist to help manage open skin lesions, particularly if you’re unsure of the cause.

There are many different causes of skin ulcers. Trauma, infections, and even malignancies can present as open wounds. Leg ulcers may be due to venous stasis, but they also can be caused by arterial insufficiency, vasculitis, and other conditions. A dermatologist might opt to perform a skin biopsy to help diagnose the lesion.

“Wound-care nurses can be very helpful in managing skin lesions, but they do not always have the experience needed to correctly diagnose the underlying problem,” says Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington. “If you’re thinking of calling the wound-care nurse, think of calling the dermatologist first.”

Prescribe an adequate quantity of topical corticosteroids for the duration of treatment.

“It’s really important to provide enough medicine,” Dr. Schwarzenberger says. Typically, a patient will receive a small tube, apply the contents, and find that “it’s enough medicine to cover their body once. This doesn’t work if you intended to have the patient apply it all over for two weeks.”

It takes, on average, 30 g of a topical medication to cover the body once. With topical steroids, prescribing an insufficient quantity “dooms your therapy to failure.”

Allergic reactions from these medications are rare, and some insurance companies charge the same regardless of the size. Prescribing a small amount initially might incur an additional expense for the patient.

Beware of painful or blistering rashes, especially if they involve the mucosa of the mouth, eyes, or genitals.

“These symptoms can be associated with potentially deadly toxic epidermal necrolysis,” says Daniel Aires, MD, JD, director of the division of dermatology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, Kan. “Consult dermatology immediately. The sooner treatment is begun, the better the odds of survival.”

If a rash involves the eye, call an ophthalmologist and a dermatologist. “Eyes are more likely than skin to develop chronic complications after resolution of an acute condition,” he says.

For a rash involving primarily the mouth, call an otolaryngologist, a dentist, or both, as well as a dermatologist. These specialists are more skilled in visualizing and treating oral conditions.

Watch out for zoster, widespread herpes, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

These blistering conditions require urgent diagnosis and treatment, so a dermatologist’s expertise is needed quickly, Dr. Aires says. Even without the presence of blisters, a single region of the skin or “dermatome” gives pause for concern.

“This could be a sign of zoster, which is especially dangerous in immunosuppressed or otherwise debilitated patients,” he cautions. “Either perform a culture and begin treatment, or consult dermatology, or do both.”

Pay attention to itching in the wrists, genital region, and web spaces of fingers and toes.

This may be due to scabies infestation. “Scabies can spread rapidly throughout a hospital ward,” Dr. Aires says. What to do: Scrape for scabies, consider a trial of topical treatment, and consult a dermatologist if you’re unsure.

Be mindful of the rapid onset of purpuric lesionscon the skin.

They warrant suspicion of such conditions as vasculitis, hypercoaguable states, and disseminated angiotropic infections, says Dr. Hopkins of Oregon Health & Science University. “The shape and size of purpuric skin lesions help determine the etiology. A few characteristic examples include papular purpura and retiform purpura. Papular purpura [raised purpuric papules] may suggest vasculitis. Purpura that forms net-like patches is called retiform purpura and suggests a vaso-occlusive process, such as from a hypercoaguable state, embolic phenomena, or calciphylaxis.”

13 Avoid consults for improving rashes and seborrheic keratosis, as well as nonurgent outpatient issues, such as psoriasis, rosacea, or a history of skin cancer. These conditions “are more easily addressed in a clinic, as opposed to in a hospital, where the patient is lying in a bed feeling ill with IV tubes in place,” Dr. Aires says. “It also reflects respect for the dermatologist’s time. Inpatient dermatology can be pretty busy, so it’s preferable to consult primarily for urgent skin issues.” Consultations can be costly, too, and most patients would rather avoid additional medical bills.

Don’t prescribe combined betamethasone/clotrimazole, also known as Lotrisone, for chronic scaly hands, feet, or groin.

Although it is not harmful, “it is not usually a great choice for typical ‘dermatophyte’ fungal infections, such as athlete’s foot and ‘jock itch,’” Dr. Aires says. “Over-the-counter Lamisil is better, particularly following daily use of 10-minute soaks in 50-50 vinegar-water. Even for yeast infections, miconazole is better than clotrimazole.”

As for betamethasone, this “component is way too strong for the groin area and can cause atrophy or worse,” he says.

—Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, MPH, director of inpatient dermatology, education, and research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Encourage patients to follow up with a dermatologist on an outpatient basis.

By heeding this advice, patients are less likely to return to the ED for skin conditions that can be managed in an office, says Kirsten Flynn, MD, a dermatologist at Banner Health Center in Sun City West, Ariz. Inpatient admissions by dermatologists have been decreasing over the years. Most patients with skin diseases or cutaneous manifestations of systemic illnesses are admitted to hospitals by other physicians.

“Many dermatologists are happy to fit in urgent consults in their clinics. Drug eruptions are by far the most common consultation request,” says Dr. Flynn, who notes that high-dose IV steroids can cause complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel perforation, opportunistic infections, and exacerbation of underlying diseases. “In most cases, removing the offending agent and providing supportive care is the best option.”

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York.

Rival Hospitalists Can Bring Havoc, or Healthy Competition to Hospitals

In November 2011, the board of directors of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla., voted to close access at its four hospitals to any hospitalist who didn’t already practice there or wasn’t affiliated with private practices that contracted with the health system. According to a report in a local newspaper, the proliferation of competing hospitalist practices at Lee Memorial was contributing to high rates of patient and referring physician dissatisfaction and hospitalist turnover.1 As a result, the board limited new hospitalists from entering practice in their facilities until they could develop “rules of engagement” for the existing hospitalists through new contracts and standards of practice.

The Lee Memorial example of multiple, competing hospitalist groups—and individuals practicing hospital medicine, also known as “lone wolf” hospitalists—causing havoc is atypical of the fledgling medical specialty, which has seen rapid growth the past two decades. Even so, veteran hospitalists confirm that nowadays, with nearly 40,000 hospitalists practicing in a majority of U.S. hospitals, it’s not uncommon to have multiple groups or individuals working under the same hospital roof. What is concerning to some in the specialty is how the competition can turn ugly, especially considering SHM espouses such virtues as teamwork, leadership, and quality improvement (QI).

Even so, situations arise when multiple HM groups under one roof don’t get along. Sometimes those groups or individual practitioners compete, head to head, for new admissions. Some hospitals have patient populations carved out by capitated medical groups or staff/group model HMOs. Some specialty groups, cardiology or orthopedics, for example, choose to contract hospitalist groups for their patients, setting up potential conflicts with new admissions. Other hospitals have “lone wolf” hospitalists, basically a practice of one.

No matter the dynamic, hospital administrators are frustrated with their inability to control competitive situations, especially when competing groups or individuals do not act in conjunction with their strategic goals.

Depending on hospital bylaws and state regulations, it might be difficult to exclude hospitalists from practicing in the hospital or to cut off competition. Some hospitals even welcome competition—as a prime virtue in its own right, a way to advance quality, or to guard against staffing shortages. The challenge, hospitalists and administrators say, is to encourage multiple groups to work amicably alongside each other, cooperating on the hospital’s larger mission and working toward its quality targets—and to make sure clinicians focus less on competition and more on patients (see “The Magic Bullet: Communication,”).

—Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, hospitalist, Southwest Washington Medical Center, Vancouver

Purposeful, Team-Based Medicine

Scott Nygaard, MD, Lee Memorial’s chief medical officer for physician services, announced on Aug. 29, 2012, that the health system was contracting with a newly formed medical group called Inpatient Specialists of Southwest Florida (ISSF), a partnership between Cape Coral, Fla.-based Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida (HGSF) and national management company Cogent HMG based in Brentwood, Tenn. HGSF and Cogent HMG already had established practices in two of Lee’s four hospitals.

Other existing hospitalist groups are permitted to continue practicing in these hospitals, although only a contracted group will be able to recruit or add new physicians, Dr. Nygaard says.

“The bylaws did not allow us to formally close access for staff already in practice,” he said. Physicians have the option of joining ISSF, and eventually, he says, the other groups dwindled in numbers through attrition. As Lee Memorial’s sole provider of hospitalist care, ISSF’s long-term goal is to put HM on a similar footing with other hospital-based specialties, such as emergency medicine and anesthesiology.

As of late 2012, six hospitalist groups and more than 80 hospitalists practice at Lee Memorial hospitals; 40 of those hospitalists belong to ISSF. “The other groups were all offered an opportunity to discuss a contractual relationship with the system, but they declined,” Dr. Nygaard says.

The remaining groups had worked amicably alongside each other but in an atmosphere Dr. Nygaard likens to a flea market, with each group practicing its own separate business and business model.

A standardized approach conducive to achieving the hospital’s quality and performance targets was lacking, however. As a result, Lee Memorial implemented an HM standard of care within the system. It helped somewhat, Dr. Nygaard says, but it didn’t fix all of the competition problems.

“We have learned that variation is the enemy of quality, especially in the highly complex environment of an acute-care hospital, trying to generate the kinds of measurable results we are now being asked to provide,” he explains. “We need to be more organized, structured, and purposeful in an era of team-based medicine. You need committed, aligned partnerships offering appropriate incentives.”

The ISSF contract contains such performance incentives.

“The joint venture formalizes an informal, long-standing, collaborative relationship” between the two participating HM groups, says Joseph Daley, MD, co-founder and director of quality services for Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida. “We bring substantial, local expertise to the table, and have been quality partners with both Lee Memorial and Cogent HMG.”

And, as of April, Lee Memorial spokesperson Mary Briggs reported patient satisfaction scores for hospitalists are improving. “We believe the changes put in place were the right ones,” she emailed The Hospitalist.

—Scott Nygaard, MD, chief medical officer for physician services, Lee Memorial Health System, Fort Myers, Fla.

Supply and Demand

Every local hospital environment is different, with HM group arrangements shaped to a large degree by supply and demand for physicians, says Brian Hazen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., one of five hospitals in the Inova system. Inova Fairfax employs the hospitalists in Dr. Hazen’s group but is also home to other groups, including a neurohospitalist service and about a half dozen solo practitioners. Dr. Hazen’s group receives administrative support from the hospital and primarily is assigned patients through the ED. Some of the private hospitalists don’t want to take ED call, he says, instead preferring to get referrals of insured patients from primary-care-physician groups.

“Here in the D.C. area, we’re reasonably well staffed by hospitalists, but we’re not fighting over patients. In fact, if it weren’t for the private physicians, we’d have trouble meeting current staffing needs,” Dr. Hazen says. “I have also seen competition in other hospital settings, but I haven’t been in a situation where the doctors were fighting over patients.”

The “lone wolf” hospitalists at Inova Fairfax work very hard, Dr. Hazen adds. “A lot of them have private practices, see patients in the hospital, and also take call. If one of them has to leave town on short notice, we can help them out. On the flip side, if we’re busy in the emergency department, we’ll call on them,” he says.

The ED receives instruction on which hospitalist group admits which patient, but sometimes referral mistakes are made.

“If we accidently admit a patient who should have gone to one of the private people, who depend on these admissions for their income, I let them choose whether we should continue to see that patient or do a transfer,” Dr. Hazen says. “For the most part, we all try to be nice people.”

In the current health-care environment, hospital administrators might be reluctant to erect barriers to multiple hospitalist practices under one roof for fear of restraining trade, just as they don’t stand in the way of primary-care physicians who want to follow their own patients into the hospital. It might be easier to enact equally enforced requirements for the credentialing and privileging of all hospitalists who want to practice at the hospital, spelling out expectations in such areas as following protocols. (In 2011, SHM issued a position paper on hospitalist credentialing that addressed the appropriate time to institute a credentialing category with privileging criteria for hospitalists, and how to preserve maximum flexibility within this process.)2

Hospitals can limit who they contract with, who gets administrative support—and how much—using financial and quality performance to shape contracting decisions. In many communities, that could serve as an excluder of multiple groups in the same building, but in other locales, the payor mix might be attractive enough for physicians to survive on billing alone, says Leslie Flores, MPH, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. If the hospital isn’t providing financial support, it will have less influence over how that group does things.

Dr. Hazen says his employed hospitalist group at Inova Fairfax is represented on more than 20 hospital committees and quality initiatives in the hospital, and has demonstrated its alignment with the hospital’s goals. Recently, in response to the administration’s concerns about throughput, his group initiated geographic, multidisciplinary rounding.

“I can do this because I have elite physicians, and because I protect them from unreasonable expectations,” he says. “Everyone needs to understand that the hospital needs to survive, so the hospital has a right to expect certain things from its hospitalists, such as performance on length of stay, throughput, other core measures, and promptly answering pages. Everyone should understand that those are the rules. Being fair, honest, and transparent about expectations is not an unreasonable expectation.”

Competition among hospitalists should be on a professional basis, experts emphasize, and cooperation is in everyone’s best interests. But Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Southwest Washington Medical Center in Vancouver, Wash., thinks competition can be a healthy thing for hospitalist groups.

“It forces us to make sure the services we provide are meeting the customer’s expectations,” says Dr. Palmer, who works with Cogent Physician Services, one of the three HM groups at Southwest Washington. “We can and do learn from each other.”

Impact of Health-Care Reform

Beware the transformation health-care reform is having on the dynamics of hospital-based practice and the competitive landscape facing more hospitalist groups, says Roger Heroux, MHA, PhD, CHE, consultant with Hospitalist Management Resources LLC. Reforms mean hospitalists are seeing an increased emphasis on coordinating with post-acute-care providers, improving care transitions, preventing readmissions, and meeting hospital targets for quality and patient safety.

Primary-care groups, accountable-care organizations (ACOs), and health plans could choose specific hospitalist practices they want to partner with to manage the care of their hospitalized members, but they will have clear performance expectations that those groups will need to meet, spelled out in benchmarks. Or, as some experts believe, they might opt to bring in their own hospitalist group.

“We’re spending our time working with existing hospitalist programs to help them be more efficient and effective, to manage risk, and to become aggressive about meeting the clinical benchmarks,” Heroux says. Hospitals, ACOs, and capitated groups can’t afford not to have a high-performing hospitalist program, so this will become a hallmark of survival for hospitalist programs as well. “In a highly managed environment, patients will be managed by a hospitalist group that is responsive to these expectations,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Gluck F. Lee Memorial Health Systems’ hospitalists under new controls. Fort Myers News Press. Dec. 1, 2011.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Position Statement on Hospitalist Credentialing and Medical Staff Privileges. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Where_We_Stand&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=28262. Accessed April 1, 2013.

In November 2011, the board of directors of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla., voted to close access at its four hospitals to any hospitalist who didn’t already practice there or wasn’t affiliated with private practices that contracted with the health system. According to a report in a local newspaper, the proliferation of competing hospitalist practices at Lee Memorial was contributing to high rates of patient and referring physician dissatisfaction and hospitalist turnover.1 As a result, the board limited new hospitalists from entering practice in their facilities until they could develop “rules of engagement” for the existing hospitalists through new contracts and standards of practice.

The Lee Memorial example of multiple, competing hospitalist groups—and individuals practicing hospital medicine, also known as “lone wolf” hospitalists—causing havoc is atypical of the fledgling medical specialty, which has seen rapid growth the past two decades. Even so, veteran hospitalists confirm that nowadays, with nearly 40,000 hospitalists practicing in a majority of U.S. hospitals, it’s not uncommon to have multiple groups or individuals working under the same hospital roof. What is concerning to some in the specialty is how the competition can turn ugly, especially considering SHM espouses such virtues as teamwork, leadership, and quality improvement (QI).

Even so, situations arise when multiple HM groups under one roof don’t get along. Sometimes those groups or individual practitioners compete, head to head, for new admissions. Some hospitals have patient populations carved out by capitated medical groups or staff/group model HMOs. Some specialty groups, cardiology or orthopedics, for example, choose to contract hospitalist groups for their patients, setting up potential conflicts with new admissions. Other hospitals have “lone wolf” hospitalists, basically a practice of one.

No matter the dynamic, hospital administrators are frustrated with their inability to control competitive situations, especially when competing groups or individuals do not act in conjunction with their strategic goals.

Depending on hospital bylaws and state regulations, it might be difficult to exclude hospitalists from practicing in the hospital or to cut off competition. Some hospitals even welcome competition—as a prime virtue in its own right, a way to advance quality, or to guard against staffing shortages. The challenge, hospitalists and administrators say, is to encourage multiple groups to work amicably alongside each other, cooperating on the hospital’s larger mission and working toward its quality targets—and to make sure clinicians focus less on competition and more on patients (see “The Magic Bullet: Communication,”).

—Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, hospitalist, Southwest Washington Medical Center, Vancouver

Purposeful, Team-Based Medicine

Scott Nygaard, MD, Lee Memorial’s chief medical officer for physician services, announced on Aug. 29, 2012, that the health system was contracting with a newly formed medical group called Inpatient Specialists of Southwest Florida (ISSF), a partnership between Cape Coral, Fla.-based Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida (HGSF) and national management company Cogent HMG based in Brentwood, Tenn. HGSF and Cogent HMG already had established practices in two of Lee’s four hospitals.

Other existing hospitalist groups are permitted to continue practicing in these hospitals, although only a contracted group will be able to recruit or add new physicians, Dr. Nygaard says.

“The bylaws did not allow us to formally close access for staff already in practice,” he said. Physicians have the option of joining ISSF, and eventually, he says, the other groups dwindled in numbers through attrition. As Lee Memorial’s sole provider of hospitalist care, ISSF’s long-term goal is to put HM on a similar footing with other hospital-based specialties, such as emergency medicine and anesthesiology.

As of late 2012, six hospitalist groups and more than 80 hospitalists practice at Lee Memorial hospitals; 40 of those hospitalists belong to ISSF. “The other groups were all offered an opportunity to discuss a contractual relationship with the system, but they declined,” Dr. Nygaard says.

The remaining groups had worked amicably alongside each other but in an atmosphere Dr. Nygaard likens to a flea market, with each group practicing its own separate business and business model.

A standardized approach conducive to achieving the hospital’s quality and performance targets was lacking, however. As a result, Lee Memorial implemented an HM standard of care within the system. It helped somewhat, Dr. Nygaard says, but it didn’t fix all of the competition problems.

“We have learned that variation is the enemy of quality, especially in the highly complex environment of an acute-care hospital, trying to generate the kinds of measurable results we are now being asked to provide,” he explains. “We need to be more organized, structured, and purposeful in an era of team-based medicine. You need committed, aligned partnerships offering appropriate incentives.”

The ISSF contract contains such performance incentives.

“The joint venture formalizes an informal, long-standing, collaborative relationship” between the two participating HM groups, says Joseph Daley, MD, co-founder and director of quality services for Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida. “We bring substantial, local expertise to the table, and have been quality partners with both Lee Memorial and Cogent HMG.”

And, as of April, Lee Memorial spokesperson Mary Briggs reported patient satisfaction scores for hospitalists are improving. “We believe the changes put in place were the right ones,” she emailed The Hospitalist.

—Scott Nygaard, MD, chief medical officer for physician services, Lee Memorial Health System, Fort Myers, Fla.

Supply and Demand

Every local hospital environment is different, with HM group arrangements shaped to a large degree by supply and demand for physicians, says Brian Hazen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., one of five hospitals in the Inova system. Inova Fairfax employs the hospitalists in Dr. Hazen’s group but is also home to other groups, including a neurohospitalist service and about a half dozen solo practitioners. Dr. Hazen’s group receives administrative support from the hospital and primarily is assigned patients through the ED. Some of the private hospitalists don’t want to take ED call, he says, instead preferring to get referrals of insured patients from primary-care-physician groups.

“Here in the D.C. area, we’re reasonably well staffed by hospitalists, but we’re not fighting over patients. In fact, if it weren’t for the private physicians, we’d have trouble meeting current staffing needs,” Dr. Hazen says. “I have also seen competition in other hospital settings, but I haven’t been in a situation where the doctors were fighting over patients.”

The “lone wolf” hospitalists at Inova Fairfax work very hard, Dr. Hazen adds. “A lot of them have private practices, see patients in the hospital, and also take call. If one of them has to leave town on short notice, we can help them out. On the flip side, if we’re busy in the emergency department, we’ll call on them,” he says.

The ED receives instruction on which hospitalist group admits which patient, but sometimes referral mistakes are made.

“If we accidently admit a patient who should have gone to one of the private people, who depend on these admissions for their income, I let them choose whether we should continue to see that patient or do a transfer,” Dr. Hazen says. “For the most part, we all try to be nice people.”

In the current health-care environment, hospital administrators might be reluctant to erect barriers to multiple hospitalist practices under one roof for fear of restraining trade, just as they don’t stand in the way of primary-care physicians who want to follow their own patients into the hospital. It might be easier to enact equally enforced requirements for the credentialing and privileging of all hospitalists who want to practice at the hospital, spelling out expectations in such areas as following protocols. (In 2011, SHM issued a position paper on hospitalist credentialing that addressed the appropriate time to institute a credentialing category with privileging criteria for hospitalists, and how to preserve maximum flexibility within this process.)2

Hospitals can limit who they contract with, who gets administrative support—and how much—using financial and quality performance to shape contracting decisions. In many communities, that could serve as an excluder of multiple groups in the same building, but in other locales, the payor mix might be attractive enough for physicians to survive on billing alone, says Leslie Flores, MPH, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. If the hospital isn’t providing financial support, it will have less influence over how that group does things.

Dr. Hazen says his employed hospitalist group at Inova Fairfax is represented on more than 20 hospital committees and quality initiatives in the hospital, and has demonstrated its alignment with the hospital’s goals. Recently, in response to the administration’s concerns about throughput, his group initiated geographic, multidisciplinary rounding.

“I can do this because I have elite physicians, and because I protect them from unreasonable expectations,” he says. “Everyone needs to understand that the hospital needs to survive, so the hospital has a right to expect certain things from its hospitalists, such as performance on length of stay, throughput, other core measures, and promptly answering pages. Everyone should understand that those are the rules. Being fair, honest, and transparent about expectations is not an unreasonable expectation.”

Competition among hospitalists should be on a professional basis, experts emphasize, and cooperation is in everyone’s best interests. But Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Southwest Washington Medical Center in Vancouver, Wash., thinks competition can be a healthy thing for hospitalist groups.

“It forces us to make sure the services we provide are meeting the customer’s expectations,” says Dr. Palmer, who works with Cogent Physician Services, one of the three HM groups at Southwest Washington. “We can and do learn from each other.”

Impact of Health-Care Reform

Beware the transformation health-care reform is having on the dynamics of hospital-based practice and the competitive landscape facing more hospitalist groups, says Roger Heroux, MHA, PhD, CHE, consultant with Hospitalist Management Resources LLC. Reforms mean hospitalists are seeing an increased emphasis on coordinating with post-acute-care providers, improving care transitions, preventing readmissions, and meeting hospital targets for quality and patient safety.

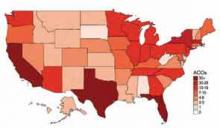

Primary-care groups, accountable-care organizations (ACOs), and health plans could choose specific hospitalist practices they want to partner with to manage the care of their hospitalized members, but they will have clear performance expectations that those groups will need to meet, spelled out in benchmarks. Or, as some experts believe, they might opt to bring in their own hospitalist group.

“We’re spending our time working with existing hospitalist programs to help them be more efficient and effective, to manage risk, and to become aggressive about meeting the clinical benchmarks,” Heroux says. Hospitals, ACOs, and capitated groups can’t afford not to have a high-performing hospitalist program, so this will become a hallmark of survival for hospitalist programs as well. “In a highly managed environment, patients will be managed by a hospitalist group that is responsive to these expectations,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Gluck F. Lee Memorial Health Systems’ hospitalists under new controls. Fort Myers News Press. Dec. 1, 2011.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Position Statement on Hospitalist Credentialing and Medical Staff Privileges. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Where_We_Stand&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=28262. Accessed April 1, 2013.

In November 2011, the board of directors of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla., voted to close access at its four hospitals to any hospitalist who didn’t already practice there or wasn’t affiliated with private practices that contracted with the health system. According to a report in a local newspaper, the proliferation of competing hospitalist practices at Lee Memorial was contributing to high rates of patient and referring physician dissatisfaction and hospitalist turnover.1 As a result, the board limited new hospitalists from entering practice in their facilities until they could develop “rules of engagement” for the existing hospitalists through new contracts and standards of practice.

The Lee Memorial example of multiple, competing hospitalist groups—and individuals practicing hospital medicine, also known as “lone wolf” hospitalists—causing havoc is atypical of the fledgling medical specialty, which has seen rapid growth the past two decades. Even so, veteran hospitalists confirm that nowadays, with nearly 40,000 hospitalists practicing in a majority of U.S. hospitals, it’s not uncommon to have multiple groups or individuals working under the same hospital roof. What is concerning to some in the specialty is how the competition can turn ugly, especially considering SHM espouses such virtues as teamwork, leadership, and quality improvement (QI).

Even so, situations arise when multiple HM groups under one roof don’t get along. Sometimes those groups or individual practitioners compete, head to head, for new admissions. Some hospitals have patient populations carved out by capitated medical groups or staff/group model HMOs. Some specialty groups, cardiology or orthopedics, for example, choose to contract hospitalist groups for their patients, setting up potential conflicts with new admissions. Other hospitals have “lone wolf” hospitalists, basically a practice of one.

No matter the dynamic, hospital administrators are frustrated with their inability to control competitive situations, especially when competing groups or individuals do not act in conjunction with their strategic goals.

Depending on hospital bylaws and state regulations, it might be difficult to exclude hospitalists from practicing in the hospital or to cut off competition. Some hospitals even welcome competition—as a prime virtue in its own right, a way to advance quality, or to guard against staffing shortages. The challenge, hospitalists and administrators say, is to encourage multiple groups to work amicably alongside each other, cooperating on the hospital’s larger mission and working toward its quality targets—and to make sure clinicians focus less on competition and more on patients (see “The Magic Bullet: Communication,”).

—Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, hospitalist, Southwest Washington Medical Center, Vancouver

Purposeful, Team-Based Medicine

Scott Nygaard, MD, Lee Memorial’s chief medical officer for physician services, announced on Aug. 29, 2012, that the health system was contracting with a newly formed medical group called Inpatient Specialists of Southwest Florida (ISSF), a partnership between Cape Coral, Fla.-based Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida (HGSF) and national management company Cogent HMG based in Brentwood, Tenn. HGSF and Cogent HMG already had established practices in two of Lee’s four hospitals.

Other existing hospitalist groups are permitted to continue practicing in these hospitals, although only a contracted group will be able to recruit or add new physicians, Dr. Nygaard says.

“The bylaws did not allow us to formally close access for staff already in practice,” he said. Physicians have the option of joining ISSF, and eventually, he says, the other groups dwindled in numbers through attrition. As Lee Memorial’s sole provider of hospitalist care, ISSF’s long-term goal is to put HM on a similar footing with other hospital-based specialties, such as emergency medicine and anesthesiology.

As of late 2012, six hospitalist groups and more than 80 hospitalists practice at Lee Memorial hospitals; 40 of those hospitalists belong to ISSF. “The other groups were all offered an opportunity to discuss a contractual relationship with the system, but they declined,” Dr. Nygaard says.

The remaining groups had worked amicably alongside each other but in an atmosphere Dr. Nygaard likens to a flea market, with each group practicing its own separate business and business model.

A standardized approach conducive to achieving the hospital’s quality and performance targets was lacking, however. As a result, Lee Memorial implemented an HM standard of care within the system. It helped somewhat, Dr. Nygaard says, but it didn’t fix all of the competition problems.

“We have learned that variation is the enemy of quality, especially in the highly complex environment of an acute-care hospital, trying to generate the kinds of measurable results we are now being asked to provide,” he explains. “We need to be more organized, structured, and purposeful in an era of team-based medicine. You need committed, aligned partnerships offering appropriate incentives.”

The ISSF contract contains such performance incentives.

“The joint venture formalizes an informal, long-standing, collaborative relationship” between the two participating HM groups, says Joseph Daley, MD, co-founder and director of quality services for Hospitalist Group of Southwest Florida. “We bring substantial, local expertise to the table, and have been quality partners with both Lee Memorial and Cogent HMG.”

And, as of April, Lee Memorial spokesperson Mary Briggs reported patient satisfaction scores for hospitalists are improving. “We believe the changes put in place were the right ones,” she emailed The Hospitalist.

—Scott Nygaard, MD, chief medical officer for physician services, Lee Memorial Health System, Fort Myers, Fla.

Supply and Demand

Every local hospital environment is different, with HM group arrangements shaped to a large degree by supply and demand for physicians, says Brian Hazen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., one of five hospitals in the Inova system. Inova Fairfax employs the hospitalists in Dr. Hazen’s group but is also home to other groups, including a neurohospitalist service and about a half dozen solo practitioners. Dr. Hazen’s group receives administrative support from the hospital and primarily is assigned patients through the ED. Some of the private hospitalists don’t want to take ED call, he says, instead preferring to get referrals of insured patients from primary-care-physician groups.

“Here in the D.C. area, we’re reasonably well staffed by hospitalists, but we’re not fighting over patients. In fact, if it weren’t for the private physicians, we’d have trouble meeting current staffing needs,” Dr. Hazen says. “I have also seen competition in other hospital settings, but I haven’t been in a situation where the doctors were fighting over patients.”

The “lone wolf” hospitalists at Inova Fairfax work very hard, Dr. Hazen adds. “A lot of them have private practices, see patients in the hospital, and also take call. If one of them has to leave town on short notice, we can help them out. On the flip side, if we’re busy in the emergency department, we’ll call on them,” he says.

The ED receives instruction on which hospitalist group admits which patient, but sometimes referral mistakes are made.

“If we accidently admit a patient who should have gone to one of the private people, who depend on these admissions for their income, I let them choose whether we should continue to see that patient or do a transfer,” Dr. Hazen says. “For the most part, we all try to be nice people.”

In the current health-care environment, hospital administrators might be reluctant to erect barriers to multiple hospitalist practices under one roof for fear of restraining trade, just as they don’t stand in the way of primary-care physicians who want to follow their own patients into the hospital. It might be easier to enact equally enforced requirements for the credentialing and privileging of all hospitalists who want to practice at the hospital, spelling out expectations in such areas as following protocols. (In 2011, SHM issued a position paper on hospitalist credentialing that addressed the appropriate time to institute a credentialing category with privileging criteria for hospitalists, and how to preserve maximum flexibility within this process.)2

Hospitals can limit who they contract with, who gets administrative support—and how much—using financial and quality performance to shape contracting decisions. In many communities, that could serve as an excluder of multiple groups in the same building, but in other locales, the payor mix might be attractive enough for physicians to survive on billing alone, says Leslie Flores, MPH, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. If the hospital isn’t providing financial support, it will have less influence over how that group does things.

Dr. Hazen says his employed hospitalist group at Inova Fairfax is represented on more than 20 hospital committees and quality initiatives in the hospital, and has demonstrated its alignment with the hospital’s goals. Recently, in response to the administration’s concerns about throughput, his group initiated geographic, multidisciplinary rounding.

“I can do this because I have elite physicians, and because I protect them from unreasonable expectations,” he says. “Everyone needs to understand that the hospital needs to survive, so the hospital has a right to expect certain things from its hospitalists, such as performance on length of stay, throughput, other core measures, and promptly answering pages. Everyone should understand that those are the rules. Being fair, honest, and transparent about expectations is not an unreasonable expectation.”

Competition among hospitalists should be on a professional basis, experts emphasize, and cooperation is in everyone’s best interests. But Lowell Palmer, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Southwest Washington Medical Center in Vancouver, Wash., thinks competition can be a healthy thing for hospitalist groups.

“It forces us to make sure the services we provide are meeting the customer’s expectations,” says Dr. Palmer, who works with Cogent Physician Services, one of the three HM groups at Southwest Washington. “We can and do learn from each other.”

Impact of Health-Care Reform

Beware the transformation health-care reform is having on the dynamics of hospital-based practice and the competitive landscape facing more hospitalist groups, says Roger Heroux, MHA, PhD, CHE, consultant with Hospitalist Management Resources LLC. Reforms mean hospitalists are seeing an increased emphasis on coordinating with post-acute-care providers, improving care transitions, preventing readmissions, and meeting hospital targets for quality and patient safety.

Primary-care groups, accountable-care organizations (ACOs), and health plans could choose specific hospitalist practices they want to partner with to manage the care of their hospitalized members, but they will have clear performance expectations that those groups will need to meet, spelled out in benchmarks. Or, as some experts believe, they might opt to bring in their own hospitalist group.

“We’re spending our time working with existing hospitalist programs to help them be more efficient and effective, to manage risk, and to become aggressive about meeting the clinical benchmarks,” Heroux says. Hospitals, ACOs, and capitated groups can’t afford not to have a high-performing hospitalist program, so this will become a hallmark of survival for hospitalist programs as well. “In a highly managed environment, patients will be managed by a hospitalist group that is responsive to these expectations,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Gluck F. Lee Memorial Health Systems’ hospitalists under new controls. Fort Myers News Press. Dec. 1, 2011.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Position Statement on Hospitalist Credentialing and Medical Staff Privileges. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Where_We_Stand&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=28262. Accessed April 1, 2013.

UCSF Engages Hospitalists to Improve Patient Communication

In a poster presented at HM12, Kathryn Quinn, MPH, CPPS, FACHE, described how her quality team at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) developed a checklist to improve physician communication with patients, then taught it to the attending hospitalist faculty.1 The project began with a list of 29 best practices for patient-physician interaction, as identified in medical literature. Hospitalists then voted for the elements they felt were most important to their practice, as well as those best able to be measured, and a top-10 list was created.

Quinn, the program manager for quality and safety in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, says the communication best practices were “chosen by the people whose practices we are trying to change.”

The quality team presented the best practices in one-hour training sessions that included small-group role plays, explains co-investigator and UCSF hospitalist Diane Sliwka, MD. The training extended to outpatient physicians, medical specialists, and chief residents. Participants also were provided a laminated pocket card listing the interventions. They also received feedback from structured observations with patients on service.