User login

Anastrozole-Induced Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DI-SCLE) was first described in 1985 in 5 patients who had been taking hydrochlorothiazide.1 The skin lesions in these patients were identical to those seen in idiopathic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) and were accompanied by the same autoantibodies (anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A [SS-A] and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B [SS-B]) and HLA type (HLA-DR2/DR3) that are known to be associated with idiopathic SCLE. The skin lesions of SCLE in these 5 patients resolved spontaneously after discontinuing hydrochlorothiazide; however, anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies persisted in all except 1 patient.1 Over the last decade, an increasing number of drugs from different classes have been implicated to be associated with DI-SCLE. Since the concept of DI-SCLE was introduced, it has been reported to look identical to idiopathic SCLE, both clinically and histopathologically; however, one report suggested that the 2 entities can be distinguished based on clinical variations.2 In general, patients with DI-SCLE develop the same anti-Ro antibodies as seen in idiopathic SCLE. In addition, although the rash in DI-SCLE typically resolves with withdrawal of the offending drug, the antibodies tend to persist. Herein, we report a case of a patient being treated with an aromatase inhibitor who presented with clinical, serologic, and histopathologic evidence of DI-SCLE.

Case Report

A 69-year-old woman diagnosed with breast cancer 4 years prior to her presentation to dermatology initially underwent a lumpectomy and radiation treatment. She was subsequently started on anastrozole 2 years later. After 16 months of treatment with anastrozole, she developed an erythematous scaly rash on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The patient was seen by an outside dermatologist who treated her for a patient-perceived drug rash based on biopsy results that simply demonstrated interface dermatitis. She was treated with both topical and oral steroids with little improvement and therefore presented to our office approximately 6 months after starting treatment seeking a second opinion.

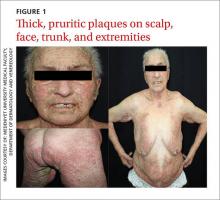

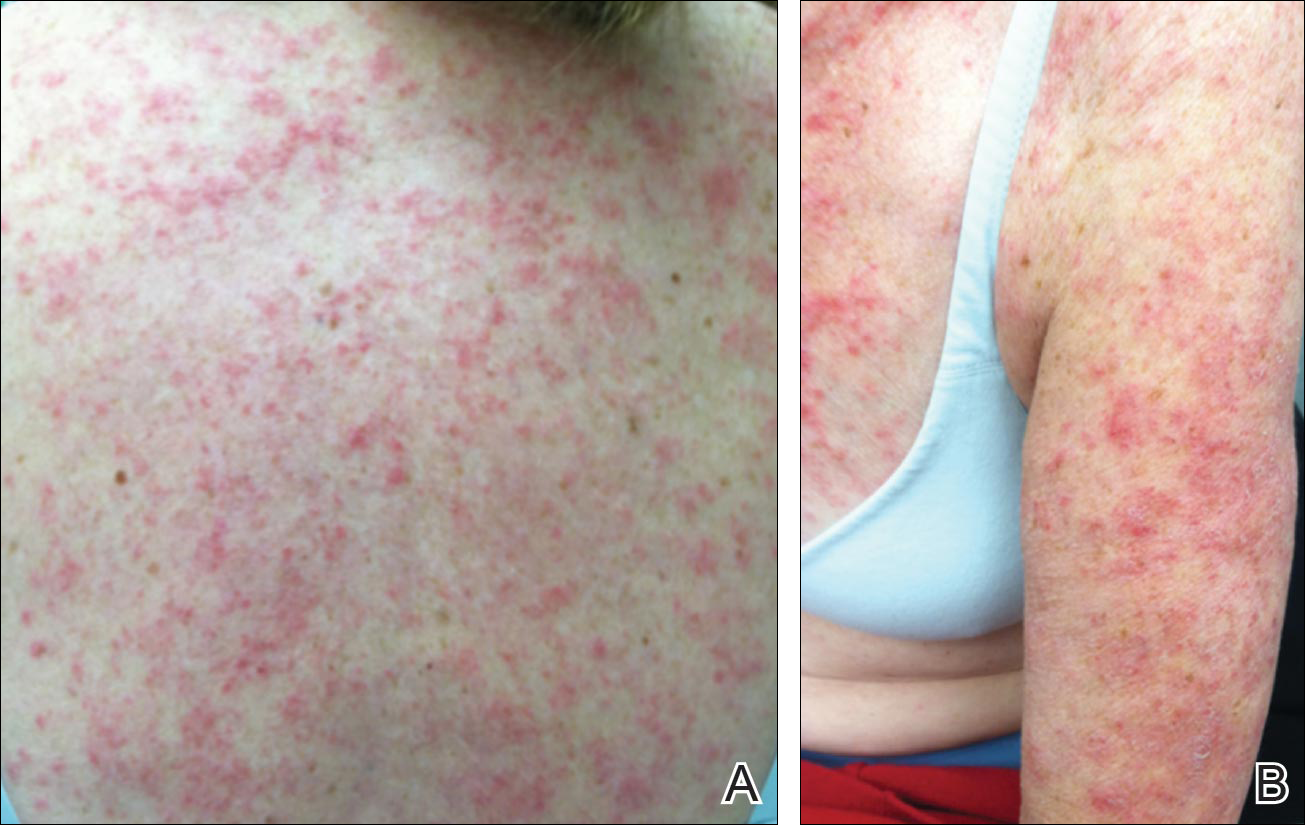

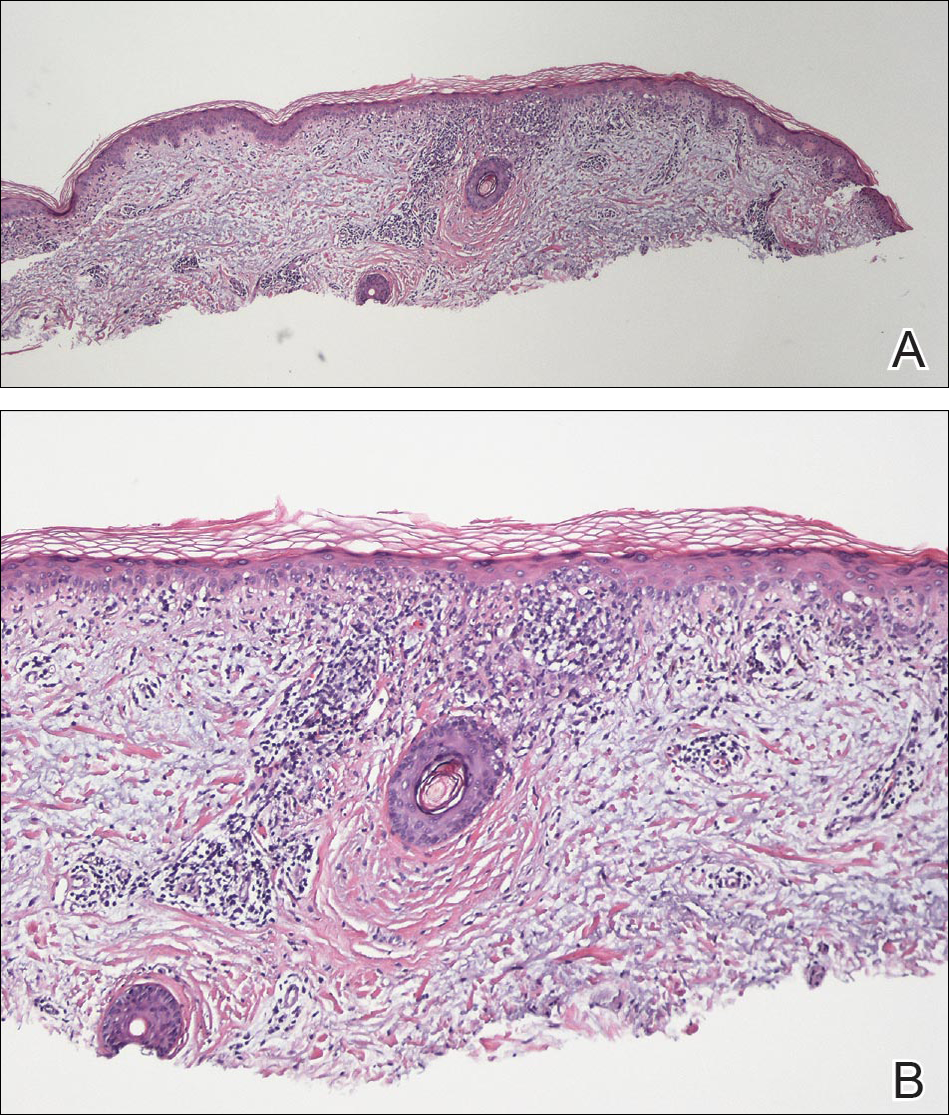

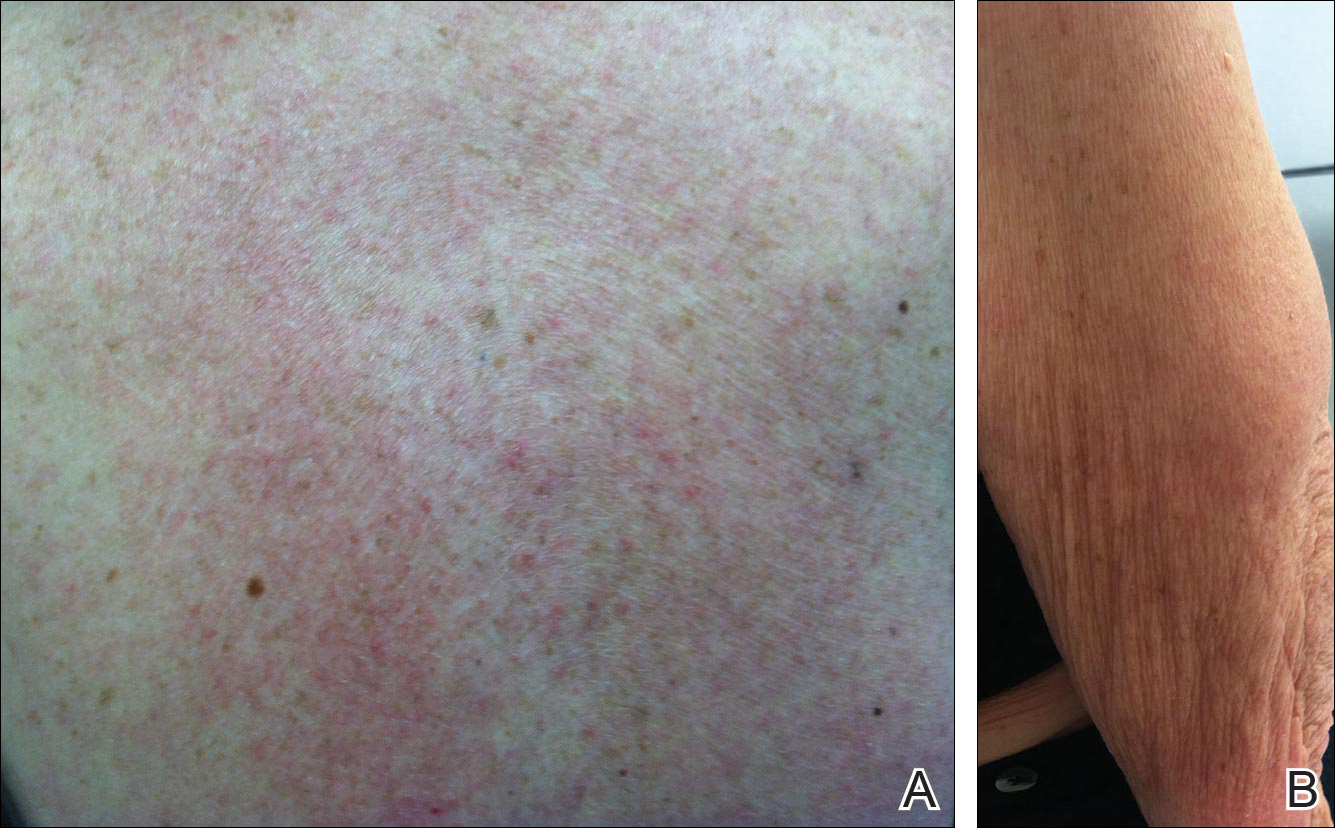

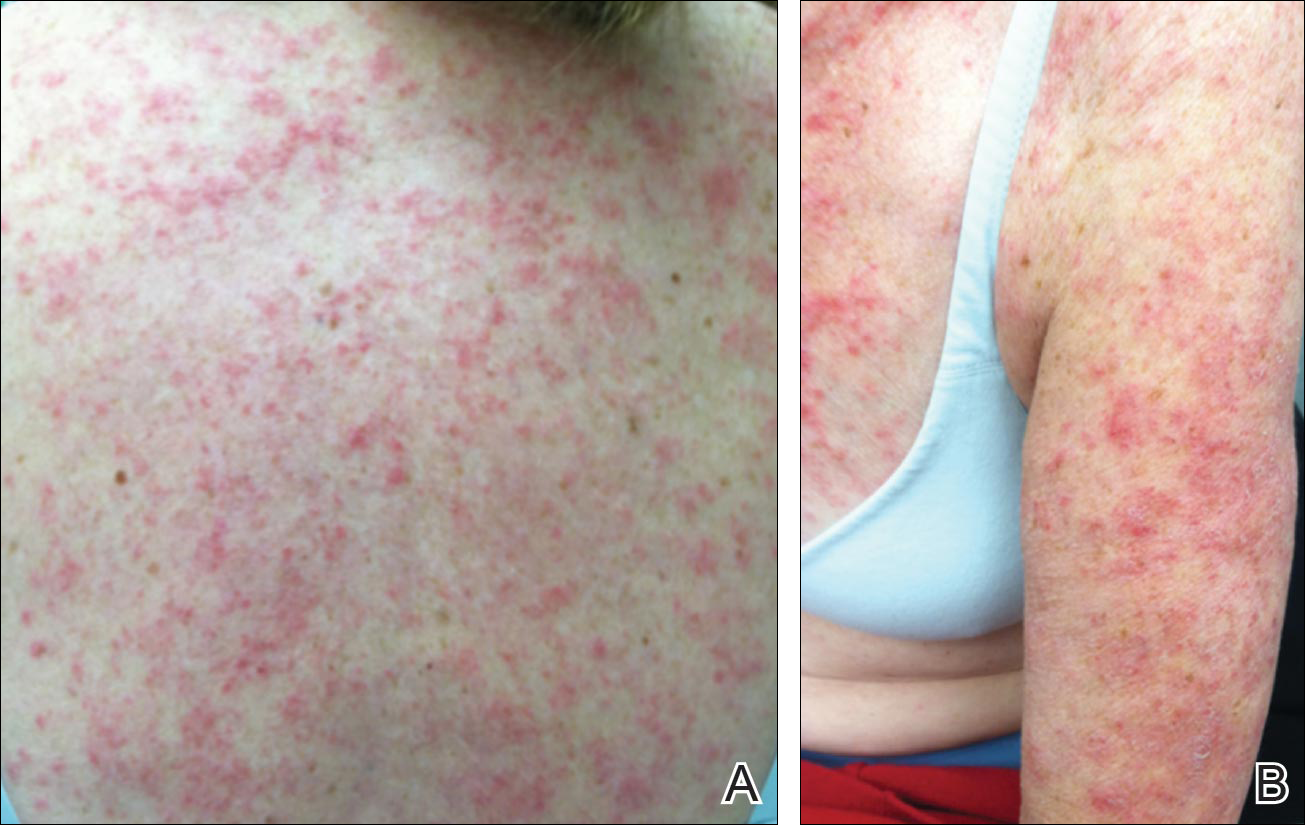

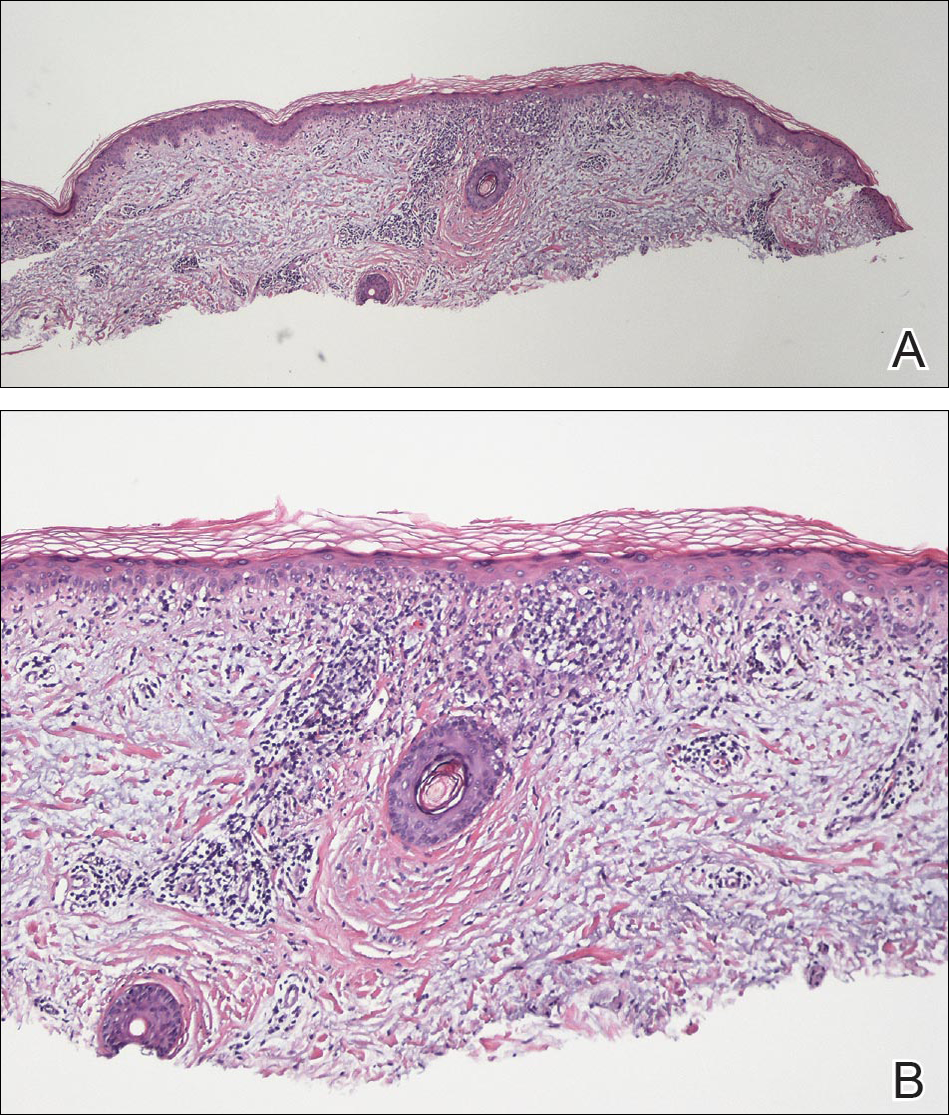

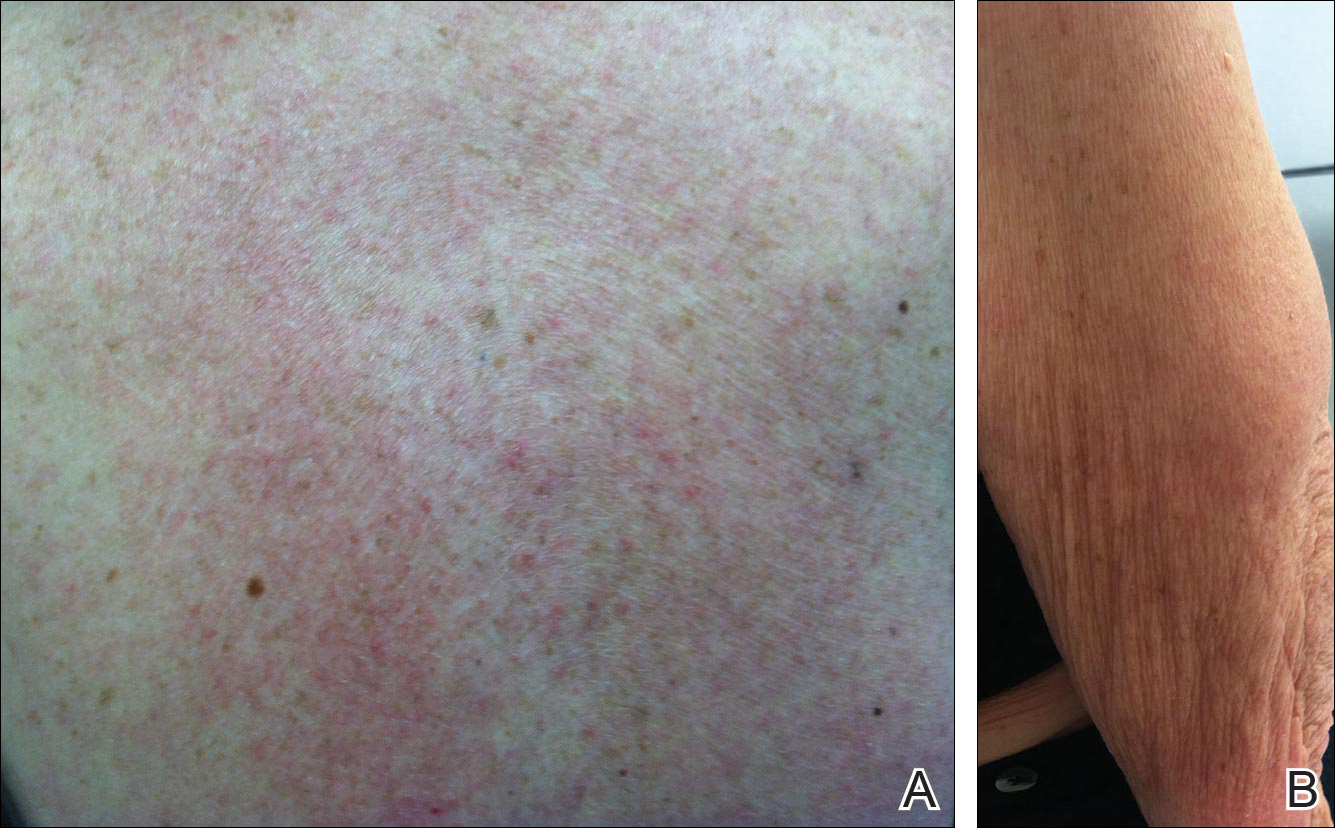

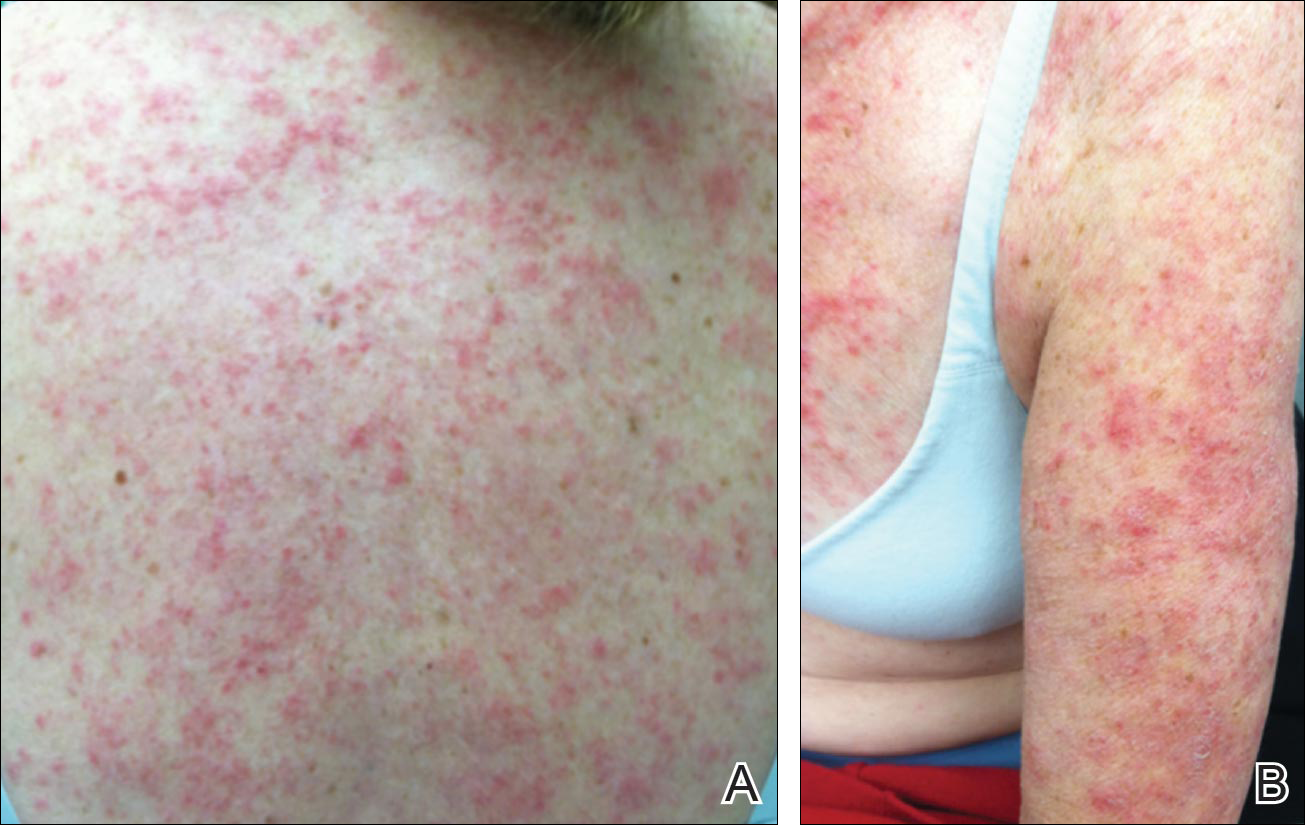

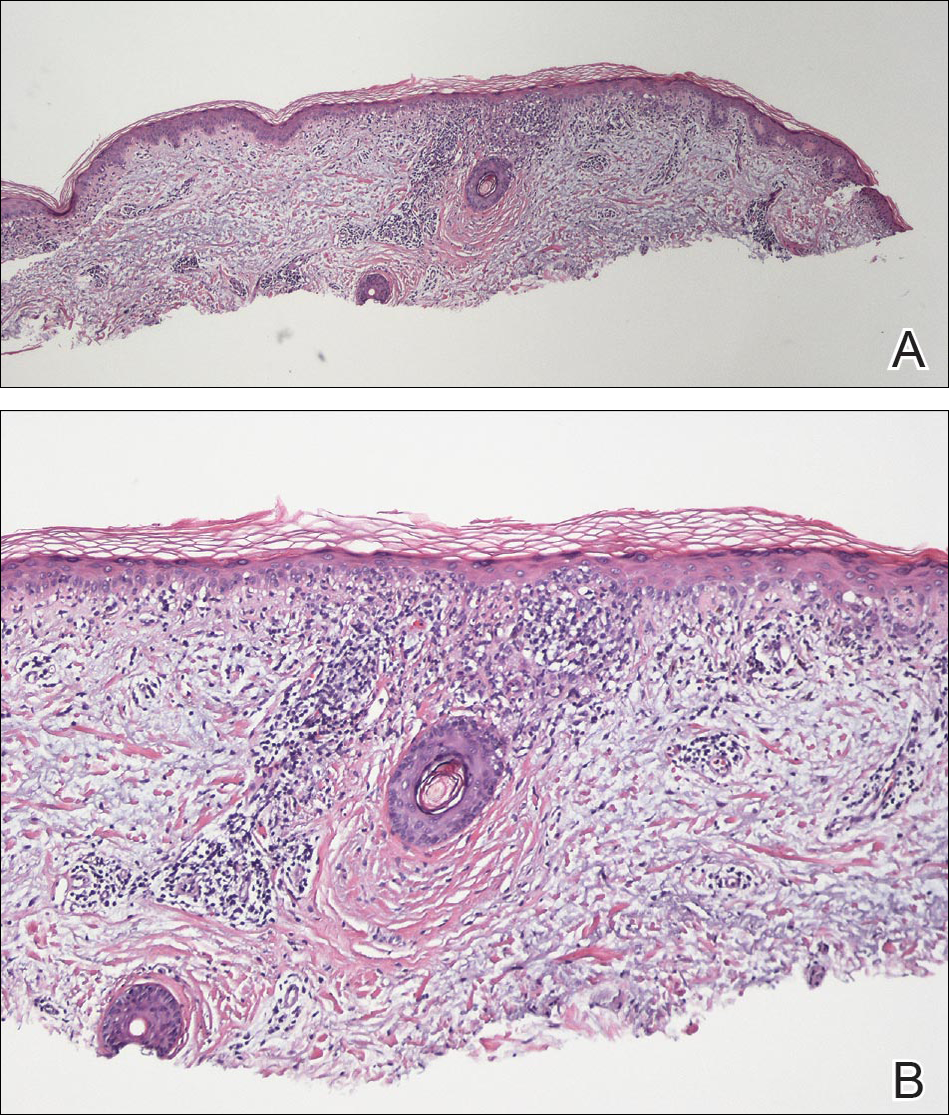

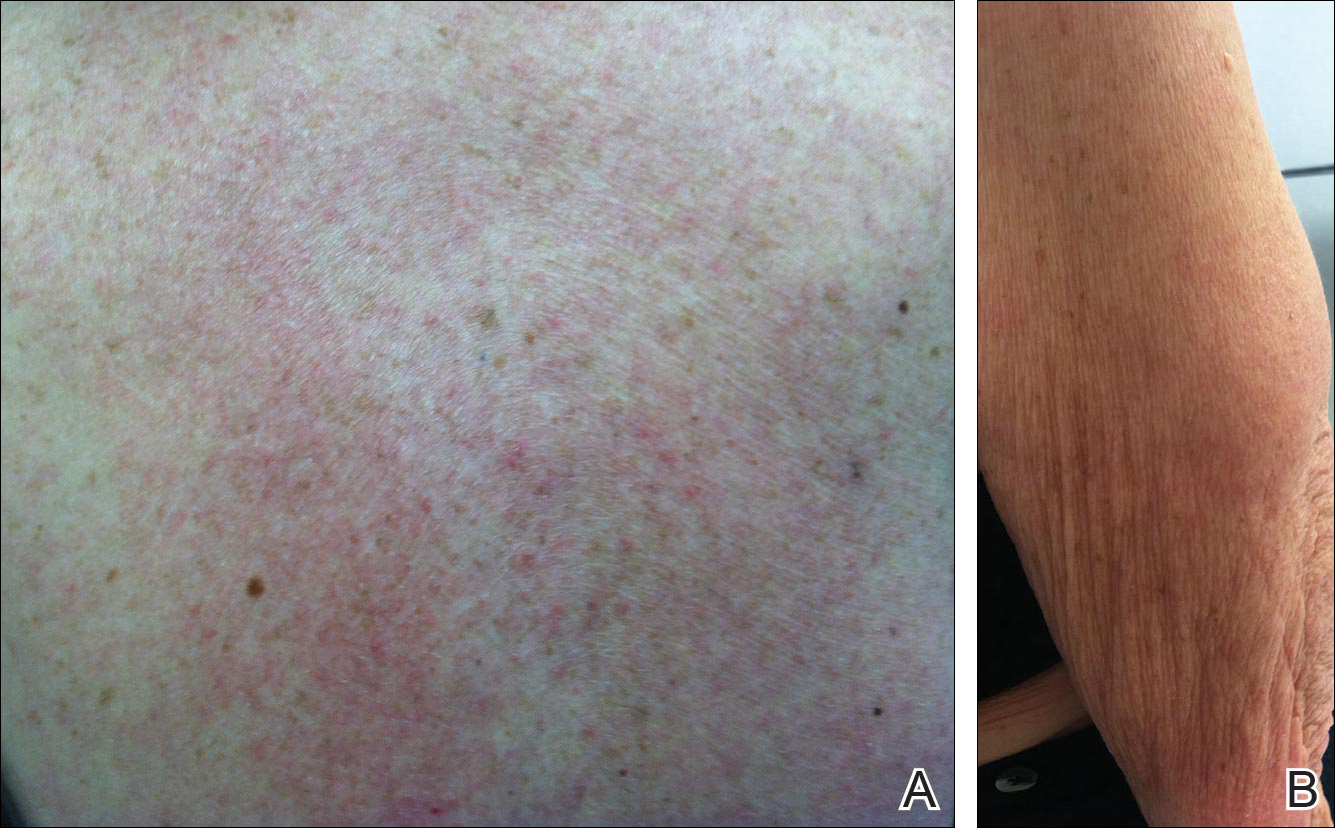

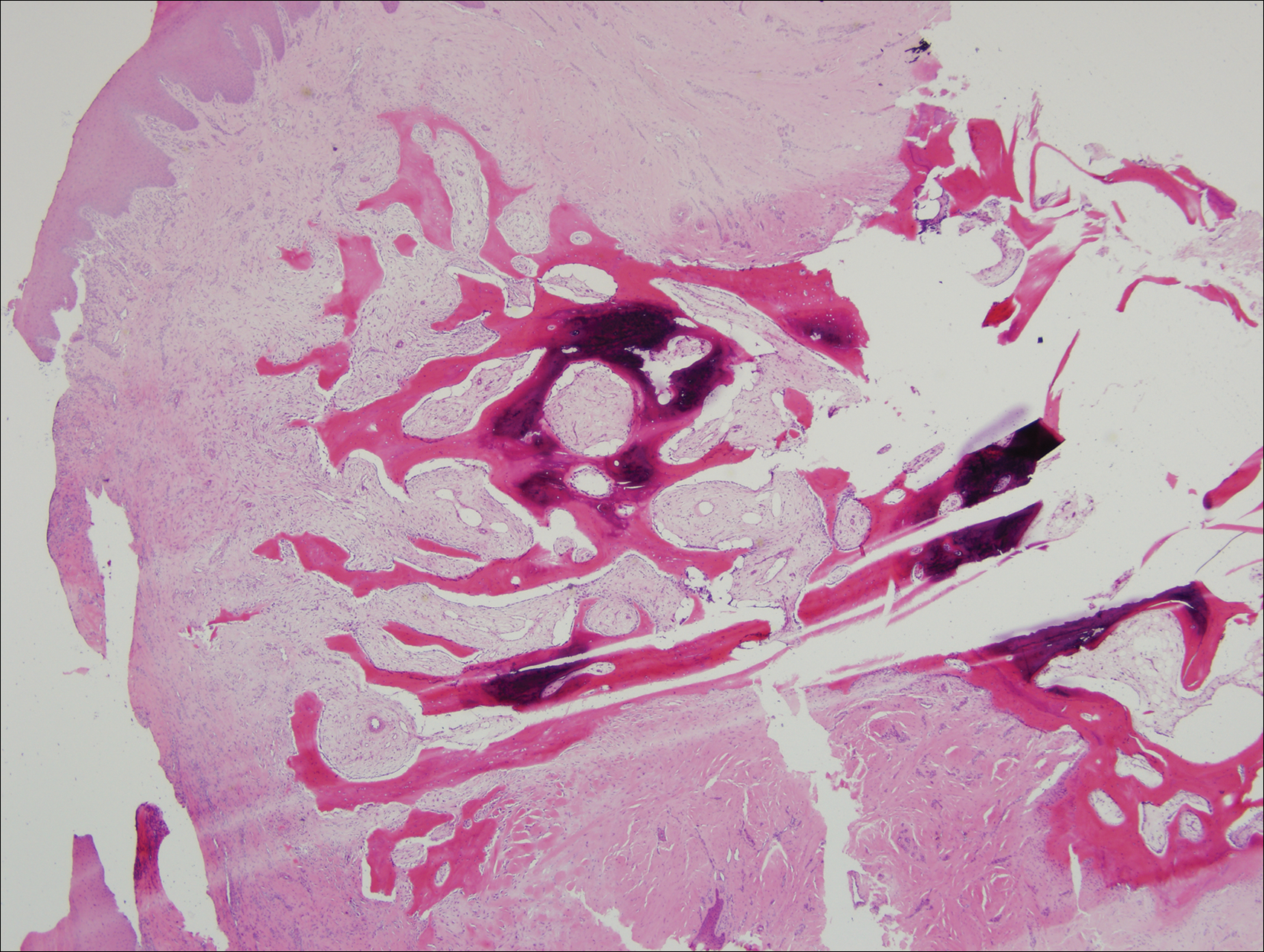

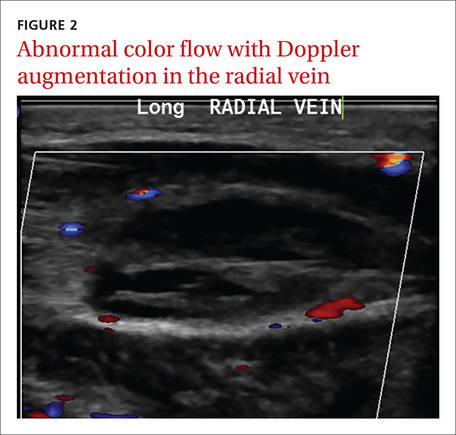

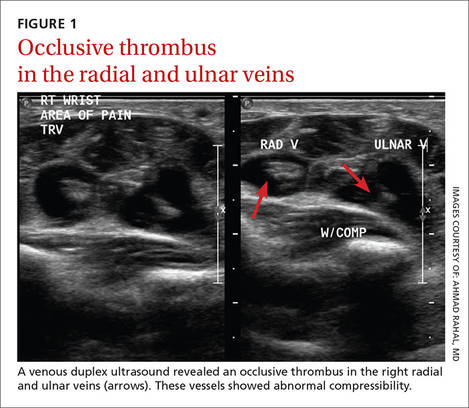

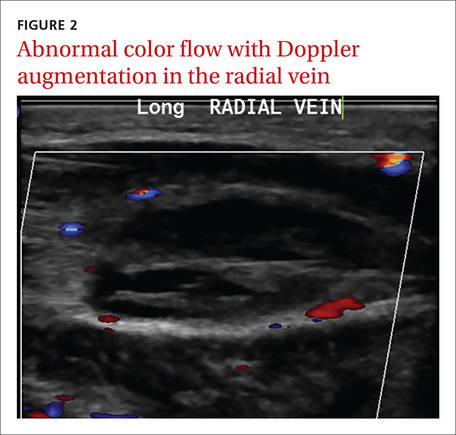

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques in a photodistributed pattern on the chest, back, legs, and arms (Figure 1). On further questioning, the patient noted that the rash became worse when she was at the beach or playing tennis outside as well as under indoor lights. A repeat biopsy was performed, revealing interface and perivascular dermatitis with an infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered pigment-laden macrophages (Figure 2). Given the appearance and distribution of the rash as well as the clinical scenario, drug-induced lupus was suspected. Anastrozole was the only medication being taken. Laboratory evaluation was performed and was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antihistone antibodies, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies but was positive for anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range, <1.0 U]). Based on these findings, anastrozole-induced SCLE was the most likely explanation for this presentation. The patient was started on a sun-protective regimen (ie, wide-brimmed hat, daily sunscreen) and anastrozole was discontinued by her oncologist; the combination led to moderate improvement in symptoms. One week later, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started, which led to notable improvement (Figure 3). The patient was seen for 2 additional follow-up visits, each time with sustained resolution of the rash. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped at her last visit 3 months after diagnosis. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation of SCLE

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a form of lupus erythematosus characterized by nonscarring, annular, scaly, erythematous plaques that occur on sun-exposed skin. The lesions are classically distributed on the upper back, chest, dorsal arms, and lateral neck but also can be found in other locations.3,4 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus may be idiopathic; may occur in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, or deficiency of the second component of complement (C2d); or may be drug induced.5 On histology SCLE presents as a lichenoid tissue reaction with focal vacuolization of the epidermal basal layer and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. On direct immunofluorescence, both idiopathic and drug-induced SCLE present with granular deposition of IgM, IgG, and C3 in a bandlike array at the dermoepidermal junction and circulating anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies. Therefore, histopathologically and immunologically, DI-SCLE is indistinguishable from idiopathic cases.6

Differential Diagnosis

It was previously thought that the clinical presentation of DI-SCLE and idiopathic SCLE were indistinguishable; however, Marzano et al2 described remarkable differences in the cutaneous manifestations of the 2 diseases. Drug-induced SCLE lesions are more widespread, occur more frequently on the legs, and may be bullous or erythema multiforme–like versus the idiopathic lesions, which tend to be more concentrated on the upper body and classically present as scaly erythematous plaques. Additionally, malar rash and vasculitic lesions, such as purpura and necrotic-ulcerative lesions, are seen more often in DI-SCLE.

Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (DI-SLE) is a lupuslike syndrome that can be differentiated from DI-SCLE by virtue of its clinical and serological presentation. It differs from DI-SCLE in that DI-SLE typically does not present with skin symptoms; rather, systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, arthralgia, polyarthritis, pericarditis, and pleuritis are more commonly seen. Additionally, it has been associated with antihistone antibodies.4 More than 80 drugs have been reported to cause DI-SLE, including procainamide, hydralazine, and quinidine.7

To be classified as either DI-SCLE or DI-SLE, symptoms need to present after administration of the triggering drug and must resolve after the drug is discontinued.7 The drugs most commonly associated with DI-SCLE are thiazides, calcium channel blockers, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and terbinafine, with few cases citing anastrozole as the inciting agent.4,6,8,9 The incubation period for DI-SCLE varies substantially. Thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers typically have the longest incubation period, ranging from 6 months to 5 years for thiazides,1,6,10,11 while calcium channel blockers have an average incubation period of 3 years.12 Drug-induced SCLE associated with antifungals, however, usually is much more rapid in onset; the incubation period on average is 5 weeks for terbinafine and 2 weeks for griseofulvin.13-15

Antiestrogen Drugs and SCLE

Anastrozole, the inciting agent in our case, is a third-generation, selective, nonsteroidal, aromatase inhibitor with no progestogenic, androgenic, or estrogenic activity. Anastrozole, when taken at its recommended dosage of 1 mg daily, will suppress estradiol. It is used as an adjuvant treatment of estrogen-sensitive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. In contrast to a prior case of DI-SCLE secondary to anastrozole in which the incubation period was approximately 1 month,8 our patient had an incubation period of approximately 16 months. Tamoxifen, another antiestrogen drug, also has been associated with DI-SCLE.9 In cases of tamoxifen-induced SCLE, the incubation period was several years, which is more similar to our patient. Although these drugs do not have the same mechanism of action, they both have antiestrogen properties.9 A systemic review of DI-SCLE reported that incubation periods between drug exposure and appearance of DI-SCLE varied greatly and were drug class dependent. It is possible that reactions associated with antiestrogen medications have a delayed presentation; however, given there are limited cases of anastrozole-induced DI-SCLE, we cannot make a clear statement on incubation periods.6

Reports of DI-SCLE caused by antiestrogen drugs are particularly interesting because sex hormones in relation to lupus disease activity have been the subject of debate for decades. Women are considerably more likely to develop autoimmune diseases than men, suggesting that steroid hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, influence the immune system.16 Estrogen actions are proinflammatory, while the actions of progesterone, androgens, and glucocorticoids are anti-inflammatory.17 Studies in women with lupus revealed an increased rate of mild- to moderate-intensity disease flares associated with estrogen-containing hormone replace-ment therapy.18-20

Over the years, several antiestrogen therapies have been used in murine models, which showed remarkable clinical improvement in the course of SLE. The precise mechanisms involved in disease immunomodulation by these therapies have not been elucidated.21-23 It is thought that estrogen plays a role in the synthesis and expression of Ro antigens on the surface of keratinocytes, increasing the fixation of anti-Ro antibodies in keratinocytes and provoking the appearance of a cutaneous eruption in patients with a susceptible HLA profile.6

Conclusion

We report a rare case of SCLE induced by anastrozole use. Cases such as ours and others that implicate antiestrogen drugs in association with DI-SCLE are particularly noteworthy, considering many studies are looking at the potential usefulness of antiestrogen therapy in the treatment of SLE. Further research on this relationship is warranted.

- Reed B, Huff J, Jones S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:49-51.

- Marzano A, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: evidence for differences from its idiopathic counterpart. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:335-341.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger T, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:925-931.

- Callen J. Review: drug induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1107-1111.

- Lin J, Callen JP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Medscape website. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1065657-overview. Updated March 7, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2016.

- Lowe GC, Henderson CL, Grau RH, et al. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:465-472.

- Vedove C, Giglio M, Schena D, et al. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:99-105.

- Trancart M, Cavailhes A, Balme B, et al. Anastrozole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus [published online December 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:628-629.

- Fumal I, Danchin A, Cosserat F, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with tamoxifen therapy: two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:251-252.

- Brown C, Deng J. Thiazide diuretics induce cutaneous lupus-like adverse reaction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33:729-733.

- Sontheimer R. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263.

- Crowson A, Magro C. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus arising in the setting of calcium channel blocker therapy. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:67-73.

- Lorentz K, Booken N, Goerdt S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by terbinafine: case report and review of literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:823-837.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Anemüller W, Angelova-Fischer I, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with terbinafine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:403-404.

- Miyagawa S, Okuchi T, Shiomi Y, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions precipitated by griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:343-346.

- Inman RD. Immunologic sex differences and the female predominance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:849-854.

- Cutolo M, Wilder RL. Different roles of androgens and estrogens in the susceptibility to autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26:825-839.

- Petri M. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:412-415.

- Lateef A, Petri M. Hormone replacement and contraceptive therapy in autoimmune diseases [published online January 18, 2012]. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:J170-J176.

- Buyon JP, Petri M, Kim MY, et al. The effect of combined estrogen and progesterone hormone replacement therapy on disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:954-962.

- Wu W, Suen J, Lin B, et al. Tamoxifen alleviates disease severity and decreases double negative T cells in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Immunology. 2000;100:110-118.

- Dayan M, Zinger H, Kalush F, et al. The beneficial effects of treatment with tamoxifen and anti-oestradiol antibody on experimental systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with cytokine modulations. Immunology. 1997;90:101-108.

- Sthoeger Z, Zinger H, Mozes E. Beneficial effects of the anti-oestrogen tamoxifen on systemic lupus erythematosus of (NZBxNZW)F1 female mice are associated with specific reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:341-346.

Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DI-SCLE) was first described in 1985 in 5 patients who had been taking hydrochlorothiazide.1 The skin lesions in these patients were identical to those seen in idiopathic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) and were accompanied by the same autoantibodies (anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A [SS-A] and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B [SS-B]) and HLA type (HLA-DR2/DR3) that are known to be associated with idiopathic SCLE. The skin lesions of SCLE in these 5 patients resolved spontaneously after discontinuing hydrochlorothiazide; however, anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies persisted in all except 1 patient.1 Over the last decade, an increasing number of drugs from different classes have been implicated to be associated with DI-SCLE. Since the concept of DI-SCLE was introduced, it has been reported to look identical to idiopathic SCLE, both clinically and histopathologically; however, one report suggested that the 2 entities can be distinguished based on clinical variations.2 In general, patients with DI-SCLE develop the same anti-Ro antibodies as seen in idiopathic SCLE. In addition, although the rash in DI-SCLE typically resolves with withdrawal of the offending drug, the antibodies tend to persist. Herein, we report a case of a patient being treated with an aromatase inhibitor who presented with clinical, serologic, and histopathologic evidence of DI-SCLE.

Case Report

A 69-year-old woman diagnosed with breast cancer 4 years prior to her presentation to dermatology initially underwent a lumpectomy and radiation treatment. She was subsequently started on anastrozole 2 years later. After 16 months of treatment with anastrozole, she developed an erythematous scaly rash on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The patient was seen by an outside dermatologist who treated her for a patient-perceived drug rash based on biopsy results that simply demonstrated interface dermatitis. She was treated with both topical and oral steroids with little improvement and therefore presented to our office approximately 6 months after starting treatment seeking a second opinion.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques in a photodistributed pattern on the chest, back, legs, and arms (Figure 1). On further questioning, the patient noted that the rash became worse when she was at the beach or playing tennis outside as well as under indoor lights. A repeat biopsy was performed, revealing interface and perivascular dermatitis with an infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered pigment-laden macrophages (Figure 2). Given the appearance and distribution of the rash as well as the clinical scenario, drug-induced lupus was suspected. Anastrozole was the only medication being taken. Laboratory evaluation was performed and was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antihistone antibodies, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies but was positive for anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range, <1.0 U]). Based on these findings, anastrozole-induced SCLE was the most likely explanation for this presentation. The patient was started on a sun-protective regimen (ie, wide-brimmed hat, daily sunscreen) and anastrozole was discontinued by her oncologist; the combination led to moderate improvement in symptoms. One week later, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started, which led to notable improvement (Figure 3). The patient was seen for 2 additional follow-up visits, each time with sustained resolution of the rash. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped at her last visit 3 months after diagnosis. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation of SCLE

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a form of lupus erythematosus characterized by nonscarring, annular, scaly, erythematous plaques that occur on sun-exposed skin. The lesions are classically distributed on the upper back, chest, dorsal arms, and lateral neck but also can be found in other locations.3,4 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus may be idiopathic; may occur in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, or deficiency of the second component of complement (C2d); or may be drug induced.5 On histology SCLE presents as a lichenoid tissue reaction with focal vacuolization of the epidermal basal layer and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. On direct immunofluorescence, both idiopathic and drug-induced SCLE present with granular deposition of IgM, IgG, and C3 in a bandlike array at the dermoepidermal junction and circulating anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies. Therefore, histopathologically and immunologically, DI-SCLE is indistinguishable from idiopathic cases.6

Differential Diagnosis

It was previously thought that the clinical presentation of DI-SCLE and idiopathic SCLE were indistinguishable; however, Marzano et al2 described remarkable differences in the cutaneous manifestations of the 2 diseases. Drug-induced SCLE lesions are more widespread, occur more frequently on the legs, and may be bullous or erythema multiforme–like versus the idiopathic lesions, which tend to be more concentrated on the upper body and classically present as scaly erythematous plaques. Additionally, malar rash and vasculitic lesions, such as purpura and necrotic-ulcerative lesions, are seen more often in DI-SCLE.

Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (DI-SLE) is a lupuslike syndrome that can be differentiated from DI-SCLE by virtue of its clinical and serological presentation. It differs from DI-SCLE in that DI-SLE typically does not present with skin symptoms; rather, systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, arthralgia, polyarthritis, pericarditis, and pleuritis are more commonly seen. Additionally, it has been associated with antihistone antibodies.4 More than 80 drugs have been reported to cause DI-SLE, including procainamide, hydralazine, and quinidine.7

To be classified as either DI-SCLE or DI-SLE, symptoms need to present after administration of the triggering drug and must resolve after the drug is discontinued.7 The drugs most commonly associated with DI-SCLE are thiazides, calcium channel blockers, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and terbinafine, with few cases citing anastrozole as the inciting agent.4,6,8,9 The incubation period for DI-SCLE varies substantially. Thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers typically have the longest incubation period, ranging from 6 months to 5 years for thiazides,1,6,10,11 while calcium channel blockers have an average incubation period of 3 years.12 Drug-induced SCLE associated with antifungals, however, usually is much more rapid in onset; the incubation period on average is 5 weeks for terbinafine and 2 weeks for griseofulvin.13-15

Antiestrogen Drugs and SCLE

Anastrozole, the inciting agent in our case, is a third-generation, selective, nonsteroidal, aromatase inhibitor with no progestogenic, androgenic, or estrogenic activity. Anastrozole, when taken at its recommended dosage of 1 mg daily, will suppress estradiol. It is used as an adjuvant treatment of estrogen-sensitive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. In contrast to a prior case of DI-SCLE secondary to anastrozole in which the incubation period was approximately 1 month,8 our patient had an incubation period of approximately 16 months. Tamoxifen, another antiestrogen drug, also has been associated with DI-SCLE.9 In cases of tamoxifen-induced SCLE, the incubation period was several years, which is more similar to our patient. Although these drugs do not have the same mechanism of action, they both have antiestrogen properties.9 A systemic review of DI-SCLE reported that incubation periods between drug exposure and appearance of DI-SCLE varied greatly and were drug class dependent. It is possible that reactions associated with antiestrogen medications have a delayed presentation; however, given there are limited cases of anastrozole-induced DI-SCLE, we cannot make a clear statement on incubation periods.6

Reports of DI-SCLE caused by antiestrogen drugs are particularly interesting because sex hormones in relation to lupus disease activity have been the subject of debate for decades. Women are considerably more likely to develop autoimmune diseases than men, suggesting that steroid hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, influence the immune system.16 Estrogen actions are proinflammatory, while the actions of progesterone, androgens, and glucocorticoids are anti-inflammatory.17 Studies in women with lupus revealed an increased rate of mild- to moderate-intensity disease flares associated with estrogen-containing hormone replace-ment therapy.18-20

Over the years, several antiestrogen therapies have been used in murine models, which showed remarkable clinical improvement in the course of SLE. The precise mechanisms involved in disease immunomodulation by these therapies have not been elucidated.21-23 It is thought that estrogen plays a role in the synthesis and expression of Ro antigens on the surface of keratinocytes, increasing the fixation of anti-Ro antibodies in keratinocytes and provoking the appearance of a cutaneous eruption in patients with a susceptible HLA profile.6

Conclusion

We report a rare case of SCLE induced by anastrozole use. Cases such as ours and others that implicate antiestrogen drugs in association with DI-SCLE are particularly noteworthy, considering many studies are looking at the potential usefulness of antiestrogen therapy in the treatment of SLE. Further research on this relationship is warranted.

Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DI-SCLE) was first described in 1985 in 5 patients who had been taking hydrochlorothiazide.1 The skin lesions in these patients were identical to those seen in idiopathic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) and were accompanied by the same autoantibodies (anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A [SS-A] and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B [SS-B]) and HLA type (HLA-DR2/DR3) that are known to be associated with idiopathic SCLE. The skin lesions of SCLE in these 5 patients resolved spontaneously after discontinuing hydrochlorothiazide; however, anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies persisted in all except 1 patient.1 Over the last decade, an increasing number of drugs from different classes have been implicated to be associated with DI-SCLE. Since the concept of DI-SCLE was introduced, it has been reported to look identical to idiopathic SCLE, both clinically and histopathologically; however, one report suggested that the 2 entities can be distinguished based on clinical variations.2 In general, patients with DI-SCLE develop the same anti-Ro antibodies as seen in idiopathic SCLE. In addition, although the rash in DI-SCLE typically resolves with withdrawal of the offending drug, the antibodies tend to persist. Herein, we report a case of a patient being treated with an aromatase inhibitor who presented with clinical, serologic, and histopathologic evidence of DI-SCLE.

Case Report

A 69-year-old woman diagnosed with breast cancer 4 years prior to her presentation to dermatology initially underwent a lumpectomy and radiation treatment. She was subsequently started on anastrozole 2 years later. After 16 months of treatment with anastrozole, she developed an erythematous scaly rash on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The patient was seen by an outside dermatologist who treated her for a patient-perceived drug rash based on biopsy results that simply demonstrated interface dermatitis. She was treated with both topical and oral steroids with little improvement and therefore presented to our office approximately 6 months after starting treatment seeking a second opinion.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques in a photodistributed pattern on the chest, back, legs, and arms (Figure 1). On further questioning, the patient noted that the rash became worse when she was at the beach or playing tennis outside as well as under indoor lights. A repeat biopsy was performed, revealing interface and perivascular dermatitis with an infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered pigment-laden macrophages (Figure 2). Given the appearance and distribution of the rash as well as the clinical scenario, drug-induced lupus was suspected. Anastrozole was the only medication being taken. Laboratory evaluation was performed and was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antihistone antibodies, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies but was positive for anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range, <1.0 U]). Based on these findings, anastrozole-induced SCLE was the most likely explanation for this presentation. The patient was started on a sun-protective regimen (ie, wide-brimmed hat, daily sunscreen) and anastrozole was discontinued by her oncologist; the combination led to moderate improvement in symptoms. One week later, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started, which led to notable improvement (Figure 3). The patient was seen for 2 additional follow-up visits, each time with sustained resolution of the rash. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped at her last visit 3 months after diagnosis. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation of SCLE

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a form of lupus erythematosus characterized by nonscarring, annular, scaly, erythematous plaques that occur on sun-exposed skin. The lesions are classically distributed on the upper back, chest, dorsal arms, and lateral neck but also can be found in other locations.3,4 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus may be idiopathic; may occur in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, or deficiency of the second component of complement (C2d); or may be drug induced.5 On histology SCLE presents as a lichenoid tissue reaction with focal vacuolization of the epidermal basal layer and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. On direct immunofluorescence, both idiopathic and drug-induced SCLE present with granular deposition of IgM, IgG, and C3 in a bandlike array at the dermoepidermal junction and circulating anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies. Therefore, histopathologically and immunologically, DI-SCLE is indistinguishable from idiopathic cases.6

Differential Diagnosis

It was previously thought that the clinical presentation of DI-SCLE and idiopathic SCLE were indistinguishable; however, Marzano et al2 described remarkable differences in the cutaneous manifestations of the 2 diseases. Drug-induced SCLE lesions are more widespread, occur more frequently on the legs, and may be bullous or erythema multiforme–like versus the idiopathic lesions, which tend to be more concentrated on the upper body and classically present as scaly erythematous plaques. Additionally, malar rash and vasculitic lesions, such as purpura and necrotic-ulcerative lesions, are seen more often in DI-SCLE.

Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (DI-SLE) is a lupuslike syndrome that can be differentiated from DI-SCLE by virtue of its clinical and serological presentation. It differs from DI-SCLE in that DI-SLE typically does not present with skin symptoms; rather, systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, arthralgia, polyarthritis, pericarditis, and pleuritis are more commonly seen. Additionally, it has been associated with antihistone antibodies.4 More than 80 drugs have been reported to cause DI-SLE, including procainamide, hydralazine, and quinidine.7

To be classified as either DI-SCLE or DI-SLE, symptoms need to present after administration of the triggering drug and must resolve after the drug is discontinued.7 The drugs most commonly associated with DI-SCLE are thiazides, calcium channel blockers, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and terbinafine, with few cases citing anastrozole as the inciting agent.4,6,8,9 The incubation period for DI-SCLE varies substantially. Thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers typically have the longest incubation period, ranging from 6 months to 5 years for thiazides,1,6,10,11 while calcium channel blockers have an average incubation period of 3 years.12 Drug-induced SCLE associated with antifungals, however, usually is much more rapid in onset; the incubation period on average is 5 weeks for terbinafine and 2 weeks for griseofulvin.13-15

Antiestrogen Drugs and SCLE

Anastrozole, the inciting agent in our case, is a third-generation, selective, nonsteroidal, aromatase inhibitor with no progestogenic, androgenic, or estrogenic activity. Anastrozole, when taken at its recommended dosage of 1 mg daily, will suppress estradiol. It is used as an adjuvant treatment of estrogen-sensitive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. In contrast to a prior case of DI-SCLE secondary to anastrozole in which the incubation period was approximately 1 month,8 our patient had an incubation period of approximately 16 months. Tamoxifen, another antiestrogen drug, also has been associated with DI-SCLE.9 In cases of tamoxifen-induced SCLE, the incubation period was several years, which is more similar to our patient. Although these drugs do not have the same mechanism of action, they both have antiestrogen properties.9 A systemic review of DI-SCLE reported that incubation periods between drug exposure and appearance of DI-SCLE varied greatly and were drug class dependent. It is possible that reactions associated with antiestrogen medications have a delayed presentation; however, given there are limited cases of anastrozole-induced DI-SCLE, we cannot make a clear statement on incubation periods.6

Reports of DI-SCLE caused by antiestrogen drugs are particularly interesting because sex hormones in relation to lupus disease activity have been the subject of debate for decades. Women are considerably more likely to develop autoimmune diseases than men, suggesting that steroid hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, influence the immune system.16 Estrogen actions are proinflammatory, while the actions of progesterone, androgens, and glucocorticoids are anti-inflammatory.17 Studies in women with lupus revealed an increased rate of mild- to moderate-intensity disease flares associated with estrogen-containing hormone replace-ment therapy.18-20

Over the years, several antiestrogen therapies have been used in murine models, which showed remarkable clinical improvement in the course of SLE. The precise mechanisms involved in disease immunomodulation by these therapies have not been elucidated.21-23 It is thought that estrogen plays a role in the synthesis and expression of Ro antigens on the surface of keratinocytes, increasing the fixation of anti-Ro antibodies in keratinocytes and provoking the appearance of a cutaneous eruption in patients with a susceptible HLA profile.6

Conclusion

We report a rare case of SCLE induced by anastrozole use. Cases such as ours and others that implicate antiestrogen drugs in association with DI-SCLE are particularly noteworthy, considering many studies are looking at the potential usefulness of antiestrogen therapy in the treatment of SLE. Further research on this relationship is warranted.

- Reed B, Huff J, Jones S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:49-51.

- Marzano A, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: evidence for differences from its idiopathic counterpart. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:335-341.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger T, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:925-931.

- Callen J. Review: drug induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1107-1111.

- Lin J, Callen JP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Medscape website. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1065657-overview. Updated March 7, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2016.

- Lowe GC, Henderson CL, Grau RH, et al. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:465-472.

- Vedove C, Giglio M, Schena D, et al. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:99-105.

- Trancart M, Cavailhes A, Balme B, et al. Anastrozole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus [published online December 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:628-629.

- Fumal I, Danchin A, Cosserat F, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with tamoxifen therapy: two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:251-252.

- Brown C, Deng J. Thiazide diuretics induce cutaneous lupus-like adverse reaction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33:729-733.

- Sontheimer R. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263.

- Crowson A, Magro C. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus arising in the setting of calcium channel blocker therapy. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:67-73.

- Lorentz K, Booken N, Goerdt S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by terbinafine: case report and review of literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:823-837.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Anemüller W, Angelova-Fischer I, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with terbinafine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:403-404.

- Miyagawa S, Okuchi T, Shiomi Y, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions precipitated by griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:343-346.

- Inman RD. Immunologic sex differences and the female predominance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:849-854.

- Cutolo M, Wilder RL. Different roles of androgens and estrogens in the susceptibility to autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26:825-839.

- Petri M. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:412-415.

- Lateef A, Petri M. Hormone replacement and contraceptive therapy in autoimmune diseases [published online January 18, 2012]. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:J170-J176.

- Buyon JP, Petri M, Kim MY, et al. The effect of combined estrogen and progesterone hormone replacement therapy on disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:954-962.

- Wu W, Suen J, Lin B, et al. Tamoxifen alleviates disease severity and decreases double negative T cells in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Immunology. 2000;100:110-118.

- Dayan M, Zinger H, Kalush F, et al. The beneficial effects of treatment with tamoxifen and anti-oestradiol antibody on experimental systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with cytokine modulations. Immunology. 1997;90:101-108.

- Sthoeger Z, Zinger H, Mozes E. Beneficial effects of the anti-oestrogen tamoxifen on systemic lupus erythematosus of (NZBxNZW)F1 female mice are associated with specific reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:341-346.

- Reed B, Huff J, Jones S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:49-51.

- Marzano A, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: evidence for differences from its idiopathic counterpart. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:335-341.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger T, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:925-931.

- Callen J. Review: drug induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1107-1111.

- Lin J, Callen JP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Medscape website. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1065657-overview. Updated March 7, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2016.

- Lowe GC, Henderson CL, Grau RH, et al. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:465-472.

- Vedove C, Giglio M, Schena D, et al. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:99-105.

- Trancart M, Cavailhes A, Balme B, et al. Anastrozole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus [published online December 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:628-629.

- Fumal I, Danchin A, Cosserat F, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with tamoxifen therapy: two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:251-252.

- Brown C, Deng J. Thiazide diuretics induce cutaneous lupus-like adverse reaction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33:729-733.

- Sontheimer R. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263.

- Crowson A, Magro C. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus arising in the setting of calcium channel blocker therapy. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:67-73.

- Lorentz K, Booken N, Goerdt S, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by terbinafine: case report and review of literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:823-837.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Anemüller W, Angelova-Fischer I, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with terbinafine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:403-404.

- Miyagawa S, Okuchi T, Shiomi Y, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions precipitated by griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:343-346.

- Inman RD. Immunologic sex differences and the female predominance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:849-854.

- Cutolo M, Wilder RL. Different roles of androgens and estrogens in the susceptibility to autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26:825-839.

- Petri M. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:412-415.

- Lateef A, Petri M. Hormone replacement and contraceptive therapy in autoimmune diseases [published online January 18, 2012]. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:J170-J176.

- Buyon JP, Petri M, Kim MY, et al. The effect of combined estrogen and progesterone hormone replacement therapy on disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:954-962.

- Wu W, Suen J, Lin B, et al. Tamoxifen alleviates disease severity and decreases double negative T cells in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Immunology. 2000;100:110-118.

- Dayan M, Zinger H, Kalush F, et al. The beneficial effects of treatment with tamoxifen and anti-oestradiol antibody on experimental systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with cytokine modulations. Immunology. 1997;90:101-108.

- Sthoeger Z, Zinger H, Mozes E. Beneficial effects of the anti-oestrogen tamoxifen on systemic lupus erythematosus of (NZBxNZW)F1 female mice are associated with specific reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:341-346.

Practice Points

- There are numerous cases of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DI-SCLE) published in the literature; however, there are limited reports with anastrozole implicated as the causative agent.

- Cases of DI-SCLE are clinically and histologically indistinguishable from idiopathic cases. It is important to recognize and withdraw the offending agent.

Prednisone and Vardenafil Hydrochloride for Refractory Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

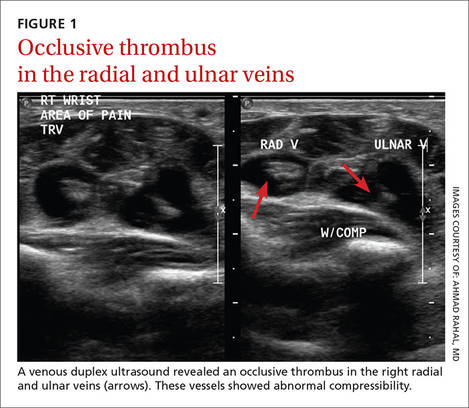

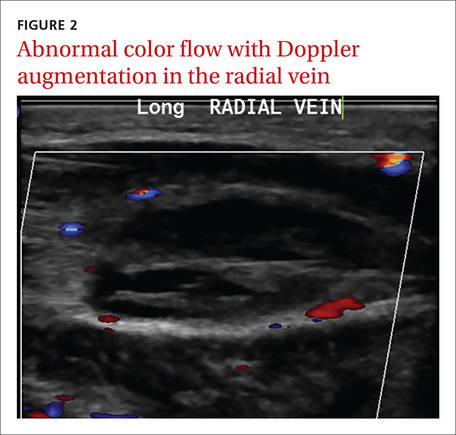

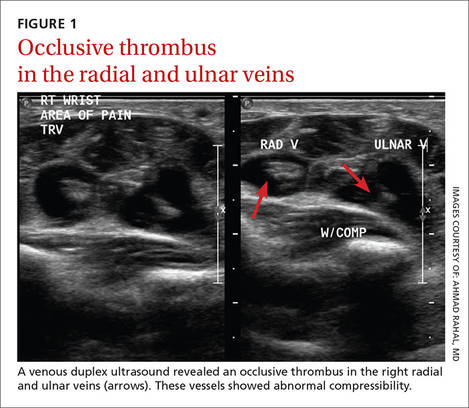

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

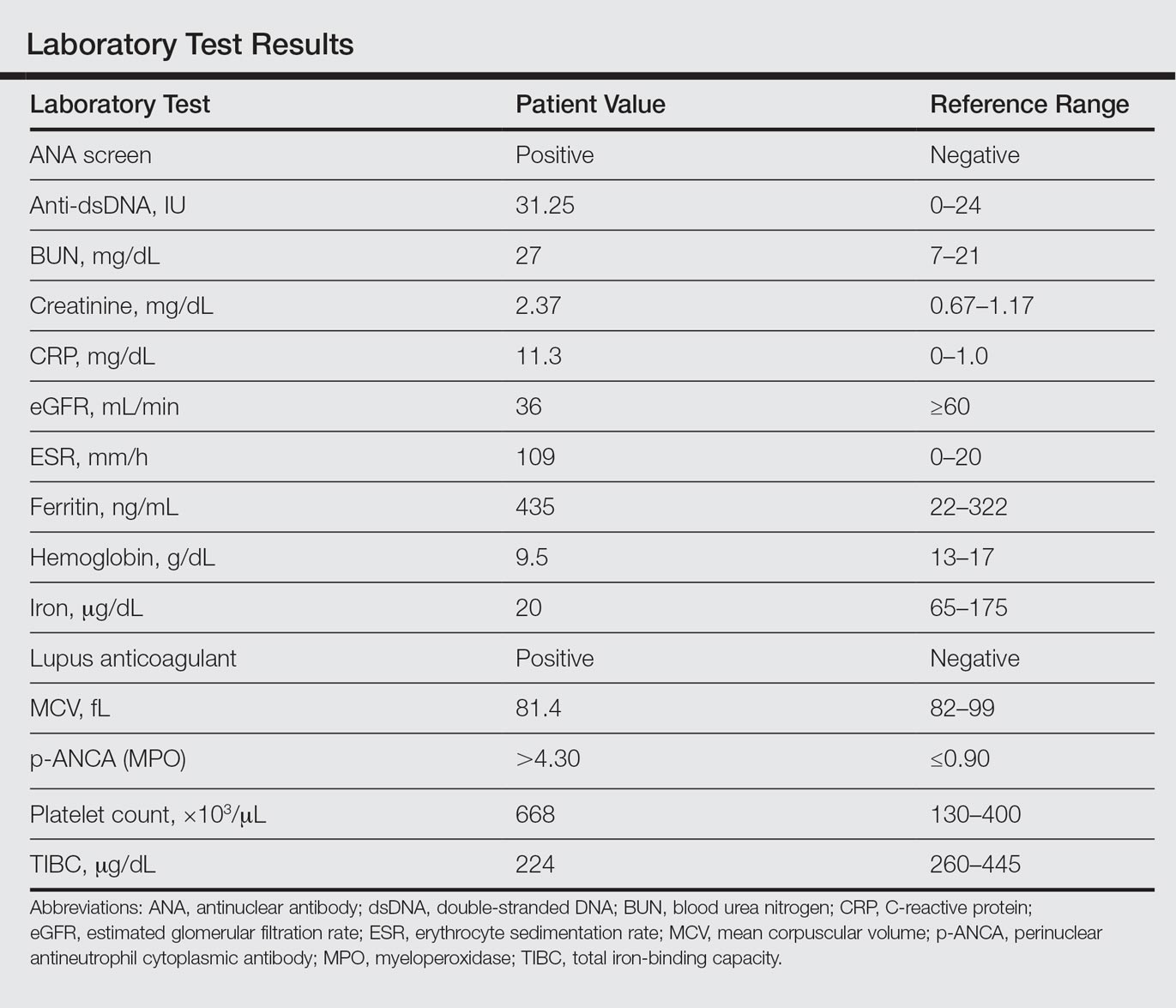

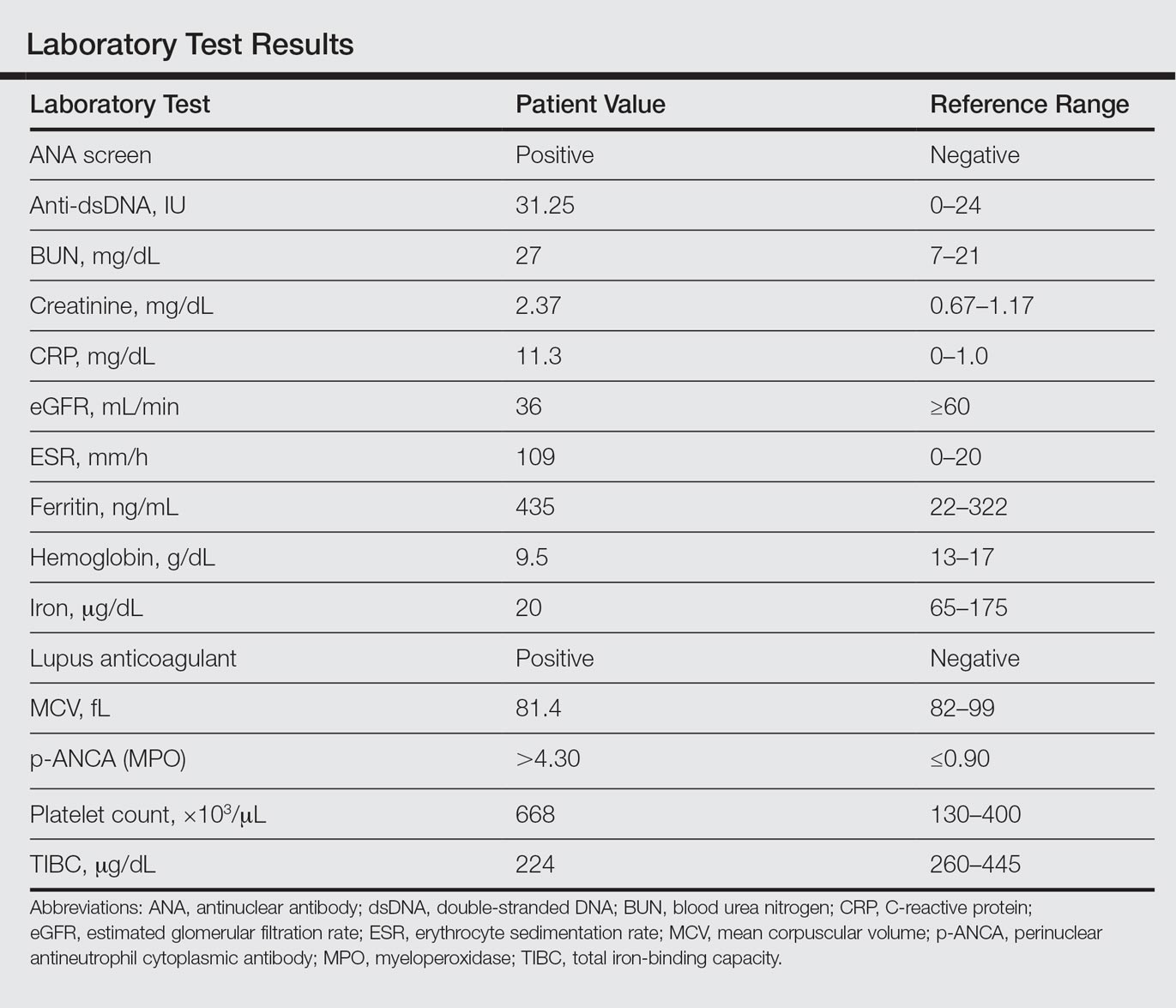

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

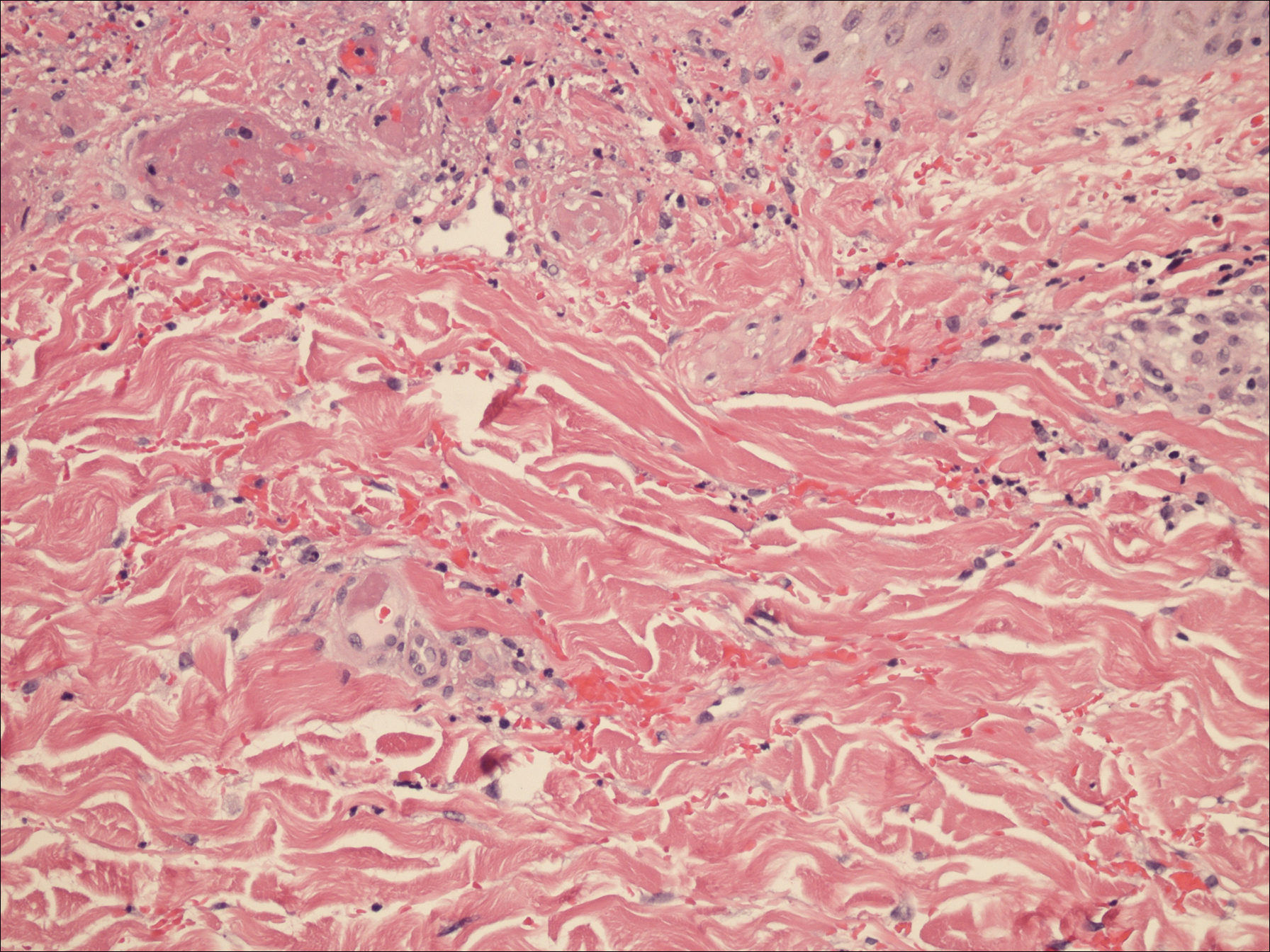

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.