User login

Up in Arms: Bilateral Luxatio Erecta Fracture-Dislocations

Unilateral inferior shoulder dislocation (luxatio erecta) is uncommon, accounting for only 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 Bilateral luxatio erecta is extremely rare, having been described fewer than 20 times in the literature. The most common etiology is hyperabduction causing the humerus to lever on the acromion; less common is axial loading onto a fully abducted arm and an extended elbow.2 Hyperabduction can occur when a person grabs an object in an attempt to stop a fall, as occurred in the present case. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 58-year-old man with a trauma injury presented to our emergency department. For his open right elbow fracture, emergency medical services had given him fentanyl en route, and when he arrived he was less responsive. As the patient reported, he had been on a scaffold 16 feet high when it began to give way. He jumped for another scaffold, 3 to 4 feet away, but came up short and, in an attempt to stop himself from falling, grabbed onto it with arms extended and above his head. His hands and arms were immediately pulled up in full extension. When both shoulders became dislocated, he could not hold on and fell to the ground, landing on a buttock. He did not lose consciousness.

Physical examination revealed both arms abducted at the shoulder, and elbows extended (Figure 1).

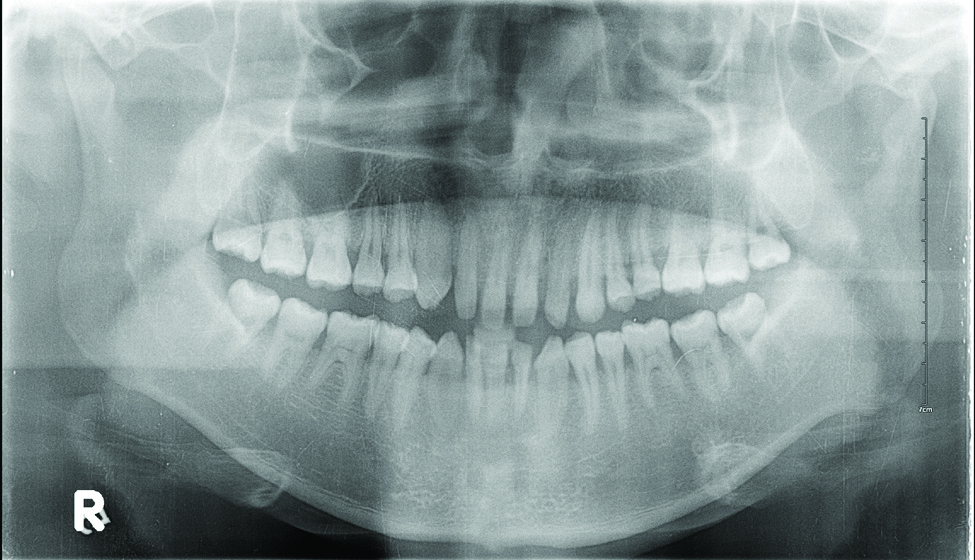

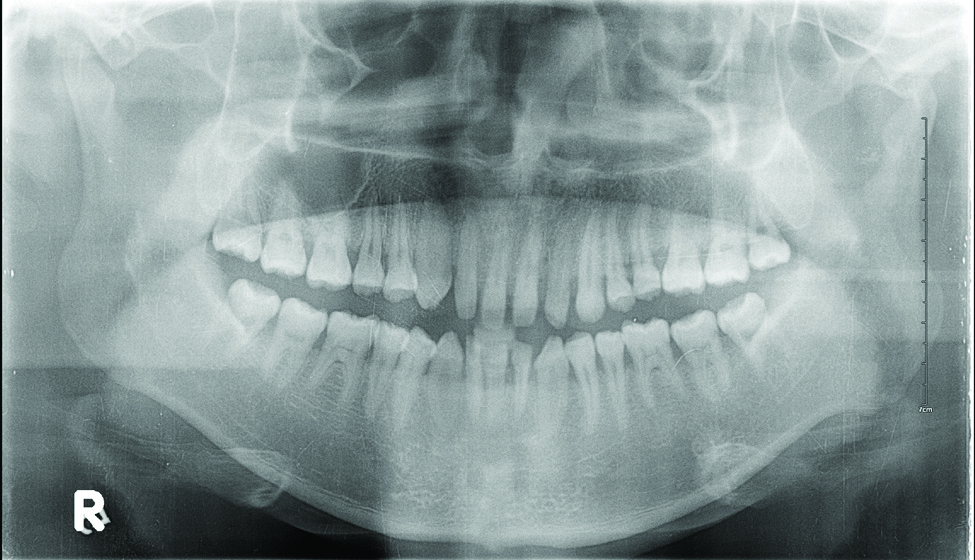

Radiographs confirmed the diagnosis and showed bilateral nondisplaced proximal humeral fractures of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2).

For the shoulder reductions, we administered propofol for conscious sedation and fentanyl for analgesia. Then, a sheet was wrapped supraclavicular and pulled across the torso inferiorly to allow countertraction when pulling the arm superiorly on the axial line. Another countertraction sheet was placed on the opposite side. For each arm, the countertraction was pulled inferiorly when the arm was pulled superiorly, both on the longitudinal plane. The arm was then gently rotated in adduction until reduction was achieved.

The right shoulder reduced relatively easily. The left shoulder reduced into an anterior dislocation—a relatively uncommon outcome in in-line traction attempts.3 (Reduction into anterior dislocation can also be a desired result in a specific technique of 2-step reduction, as described by Nho and colleagues.4) The patient’s anterior dislocation was then easily reduced into anatomical position with use of the Kocher technique of arm adduction with elbow flexion, followed by external rotation, and then finally into anatomical position with internal rotation.5 Both arms were then immobilized in full adduction with bilateral slings. The patient was admitted for further treatment of multiple fractures of the arms and vertebrae.

He was discharged in bilateral shoulder slings to an extended-care facility for physical therapy. One month after discharge, he could not elevate his arms and had minimal use of them. Two weeks later, magnetic resonance imaging showed a “comminuted greater tuberosity fracture with new displacement of fragments involving the attachment of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus; posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint with evidence of posterior and anterior labral tears; and large glenohumeral joint effusion.” The patient opted for surgical repair and underwent left shoulder arthroscopy with extensive débridement, open rotator cuff repair, open greater tuberosity reduction and internal fixation, and open biceps tenodesis. He was then discharged back to an extended-care facility to continue rehabilitation. One and a half months after surgery, he started the physical therapy phase of the massive rotator cuff repair protocol. He declined reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).

Four and a half months after injury (3 months after surgery), the left shoulder demonstrated 20° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested), and the right shoulder demonstrated 30° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested). He had no instability and no lag with good external rotation.

Six months after injury, the patient still could not lift his arms above his head. He likely would not be able to do so without RTSA, which he again declined. He continued physical therapy and clinical follow-ups.

Discussion

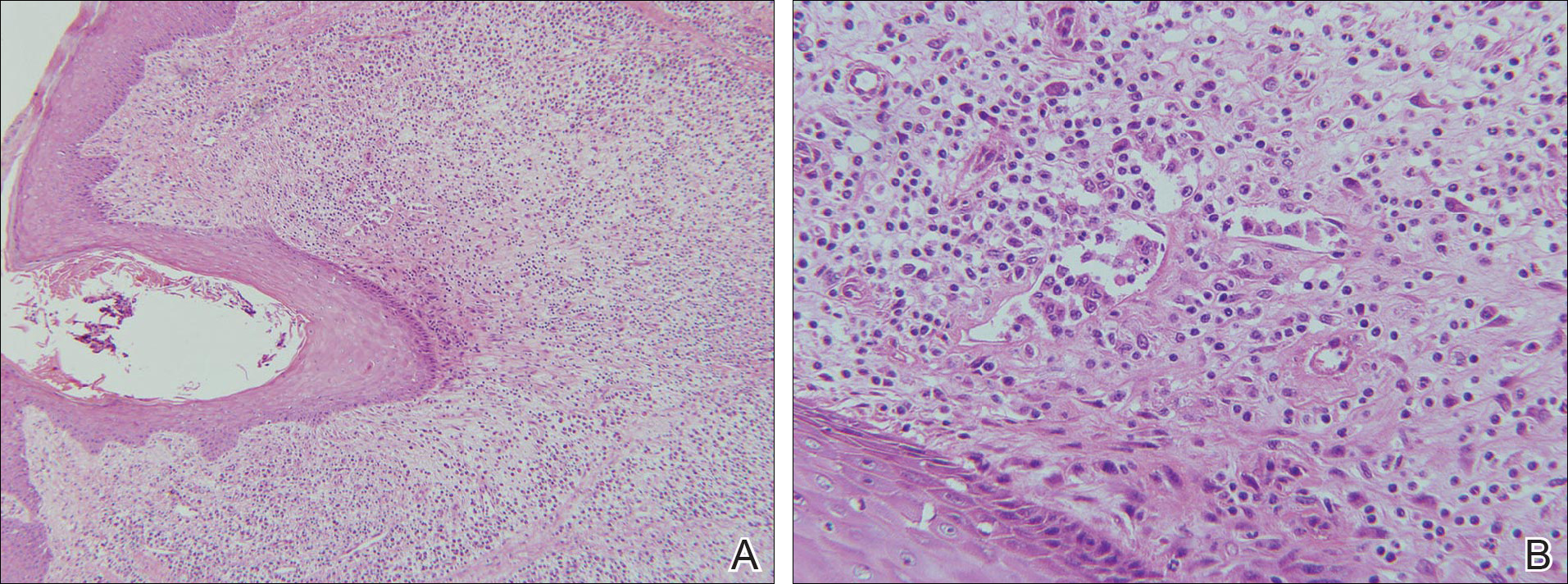

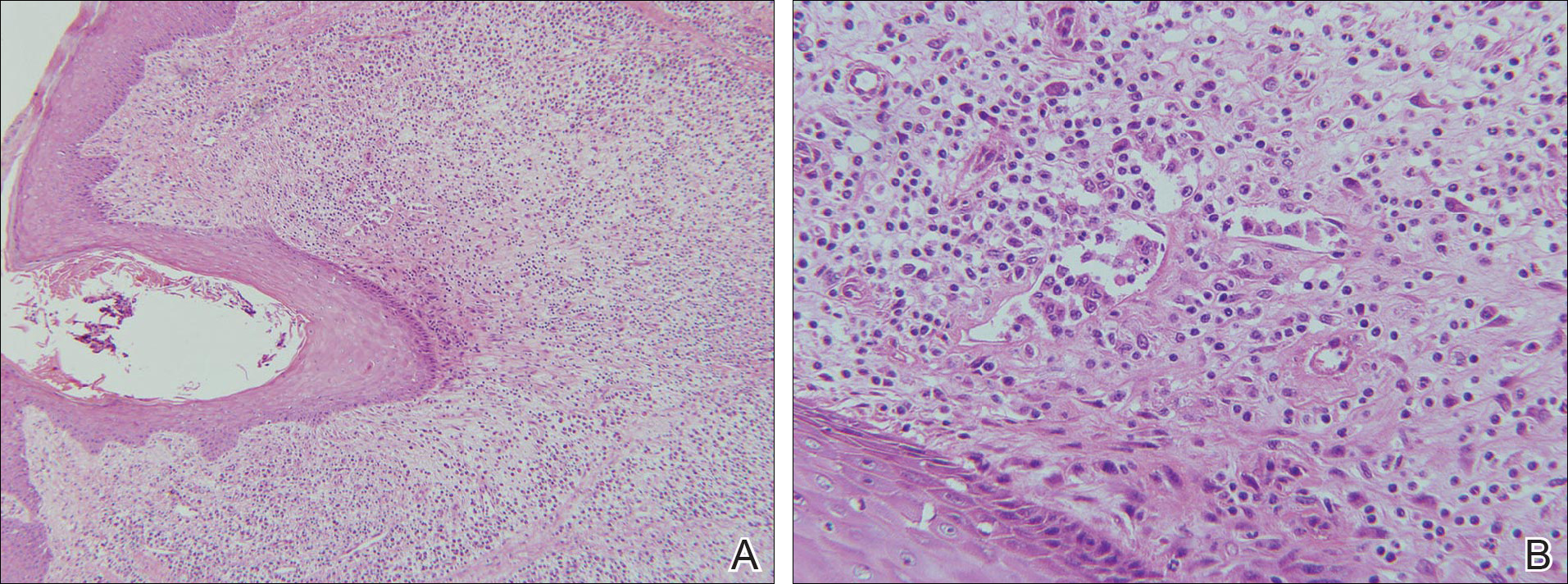

Although inferior shoulder dislocations are rare, they carry a higher rate of complications, most of which our patient experienced. Our patient had bilateral humeral head fractures, which occur in 80% of cases.6 Postreduction CT showed the degree of his fractures (Figure 3).

Our patient also had reduced sensation in the axillary nerve distribution, which occurs in 60% of inferior dislocations.6 Axillary nerve injuries produce numbness in the lateral arm or posterior shoulder and weakness with shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation.7 In our patient’s case, sensation returned after reduction, which is typical (most patients have a positive prognosis).8 As the shoulder dislocates inferiorly, the humeral head tears the glenohumeral capsule inferiorly, which can damage the axillary artery. This artery becomes the brachial and eventually the radial and ulnar arteries, which can have decreased or absent pulses with injury.

Inferior dislocations are also associated with abundant soft-tissue injuries, including torn rotator cuff, shoulder capsule avulsion, and disruption of adjacent muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis, pectoralis major).9Luxatio erecta is relatively easy to diagnose given the unmistakable arm positioning. The key for the physician is first to assess for the many possible complications, then to administer the proper sedation and analgesia for reduction, and finally to reassess for complications.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E328-E330. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Camarda L, Martorana U, D’Arienzo M. A case of bilateral luxatio erecta. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(2):97-99.

2. Musmeci E, Gaspari D, Sandri A, Regis D, Bartolozzi P. Bilateral luxatio erecta humeri associated with a unilateral brachial plexus and bilateral rotator cuff injuries: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(7):498-500.

3. Lam AC, Shih RD. Luxatio erecta complicated by anterior shoulder dislocation during reduction. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):28-30.

4. Nho SJ, Dodson CC, Bardzik KF, Brophy RH, Domb BG, MacGillivray JD. The two-step maneuver for closed reduction of inferior glenohumeral dislocation (luxatio erecta to anterior dislocation to reduction). J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(5):354-357.

5. Beattie TF, Steedman DJ, McGowan A, Robertson CE. A comparison of the Milch and Kocher techniques for acute anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury. 1986;17(5):349-352.

6. Mallon WJ, Bassett FH 3rd, Goldner RD. Luxatio erecta: the inferior glenohumeral dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 1990;4(1):19-24.

7. Miller T. Peripheral nerve injuries at the shoulder. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;6(4):170-183.

8. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):423-426.

9. Garcia R, Ponsky T, Brody F, Long J. Bilateral luxatio erecta complicated by venous thrombosis. J Trauma. 2006;60(5):1132-1134.

Unilateral inferior shoulder dislocation (luxatio erecta) is uncommon, accounting for only 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 Bilateral luxatio erecta is extremely rare, having been described fewer than 20 times in the literature. The most common etiology is hyperabduction causing the humerus to lever on the acromion; less common is axial loading onto a fully abducted arm and an extended elbow.2 Hyperabduction can occur when a person grabs an object in an attempt to stop a fall, as occurred in the present case. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 58-year-old man with a trauma injury presented to our emergency department. For his open right elbow fracture, emergency medical services had given him fentanyl en route, and when he arrived he was less responsive. As the patient reported, he had been on a scaffold 16 feet high when it began to give way. He jumped for another scaffold, 3 to 4 feet away, but came up short and, in an attempt to stop himself from falling, grabbed onto it with arms extended and above his head. His hands and arms were immediately pulled up in full extension. When both shoulders became dislocated, he could not hold on and fell to the ground, landing on a buttock. He did not lose consciousness.

Physical examination revealed both arms abducted at the shoulder, and elbows extended (Figure 1).

Radiographs confirmed the diagnosis and showed bilateral nondisplaced proximal humeral fractures of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2).

For the shoulder reductions, we administered propofol for conscious sedation and fentanyl for analgesia. Then, a sheet was wrapped supraclavicular and pulled across the torso inferiorly to allow countertraction when pulling the arm superiorly on the axial line. Another countertraction sheet was placed on the opposite side. For each arm, the countertraction was pulled inferiorly when the arm was pulled superiorly, both on the longitudinal plane. The arm was then gently rotated in adduction until reduction was achieved.

The right shoulder reduced relatively easily. The left shoulder reduced into an anterior dislocation—a relatively uncommon outcome in in-line traction attempts.3 (Reduction into anterior dislocation can also be a desired result in a specific technique of 2-step reduction, as described by Nho and colleagues.4) The patient’s anterior dislocation was then easily reduced into anatomical position with use of the Kocher technique of arm adduction with elbow flexion, followed by external rotation, and then finally into anatomical position with internal rotation.5 Both arms were then immobilized in full adduction with bilateral slings. The patient was admitted for further treatment of multiple fractures of the arms and vertebrae.

He was discharged in bilateral shoulder slings to an extended-care facility for physical therapy. One month after discharge, he could not elevate his arms and had minimal use of them. Two weeks later, magnetic resonance imaging showed a “comminuted greater tuberosity fracture with new displacement of fragments involving the attachment of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus; posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint with evidence of posterior and anterior labral tears; and large glenohumeral joint effusion.” The patient opted for surgical repair and underwent left shoulder arthroscopy with extensive débridement, open rotator cuff repair, open greater tuberosity reduction and internal fixation, and open biceps tenodesis. He was then discharged back to an extended-care facility to continue rehabilitation. One and a half months after surgery, he started the physical therapy phase of the massive rotator cuff repair protocol. He declined reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).

Four and a half months after injury (3 months after surgery), the left shoulder demonstrated 20° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested), and the right shoulder demonstrated 30° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested). He had no instability and no lag with good external rotation.

Six months after injury, the patient still could not lift his arms above his head. He likely would not be able to do so without RTSA, which he again declined. He continued physical therapy and clinical follow-ups.

Discussion

Although inferior shoulder dislocations are rare, they carry a higher rate of complications, most of which our patient experienced. Our patient had bilateral humeral head fractures, which occur in 80% of cases.6 Postreduction CT showed the degree of his fractures (Figure 3).

Our patient also had reduced sensation in the axillary nerve distribution, which occurs in 60% of inferior dislocations.6 Axillary nerve injuries produce numbness in the lateral arm or posterior shoulder and weakness with shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation.7 In our patient’s case, sensation returned after reduction, which is typical (most patients have a positive prognosis).8 As the shoulder dislocates inferiorly, the humeral head tears the glenohumeral capsule inferiorly, which can damage the axillary artery. This artery becomes the brachial and eventually the radial and ulnar arteries, which can have decreased or absent pulses with injury.

Inferior dislocations are also associated with abundant soft-tissue injuries, including torn rotator cuff, shoulder capsule avulsion, and disruption of adjacent muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis, pectoralis major).9Luxatio erecta is relatively easy to diagnose given the unmistakable arm positioning. The key for the physician is first to assess for the many possible complications, then to administer the proper sedation and analgesia for reduction, and finally to reassess for complications.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E328-E330. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Unilateral inferior shoulder dislocation (luxatio erecta) is uncommon, accounting for only 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 Bilateral luxatio erecta is extremely rare, having been described fewer than 20 times in the literature. The most common etiology is hyperabduction causing the humerus to lever on the acromion; less common is axial loading onto a fully abducted arm and an extended elbow.2 Hyperabduction can occur when a person grabs an object in an attempt to stop a fall, as occurred in the present case. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 58-year-old man with a trauma injury presented to our emergency department. For his open right elbow fracture, emergency medical services had given him fentanyl en route, and when he arrived he was less responsive. As the patient reported, he had been on a scaffold 16 feet high when it began to give way. He jumped for another scaffold, 3 to 4 feet away, but came up short and, in an attempt to stop himself from falling, grabbed onto it with arms extended and above his head. His hands and arms were immediately pulled up in full extension. When both shoulders became dislocated, he could not hold on and fell to the ground, landing on a buttock. He did not lose consciousness.

Physical examination revealed both arms abducted at the shoulder, and elbows extended (Figure 1).

Radiographs confirmed the diagnosis and showed bilateral nondisplaced proximal humeral fractures of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2).

For the shoulder reductions, we administered propofol for conscious sedation and fentanyl for analgesia. Then, a sheet was wrapped supraclavicular and pulled across the torso inferiorly to allow countertraction when pulling the arm superiorly on the axial line. Another countertraction sheet was placed on the opposite side. For each arm, the countertraction was pulled inferiorly when the arm was pulled superiorly, both on the longitudinal plane. The arm was then gently rotated in adduction until reduction was achieved.

The right shoulder reduced relatively easily. The left shoulder reduced into an anterior dislocation—a relatively uncommon outcome in in-line traction attempts.3 (Reduction into anterior dislocation can also be a desired result in a specific technique of 2-step reduction, as described by Nho and colleagues.4) The patient’s anterior dislocation was then easily reduced into anatomical position with use of the Kocher technique of arm adduction with elbow flexion, followed by external rotation, and then finally into anatomical position with internal rotation.5 Both arms were then immobilized in full adduction with bilateral slings. The patient was admitted for further treatment of multiple fractures of the arms and vertebrae.

He was discharged in bilateral shoulder slings to an extended-care facility for physical therapy. One month after discharge, he could not elevate his arms and had minimal use of them. Two weeks later, magnetic resonance imaging showed a “comminuted greater tuberosity fracture with new displacement of fragments involving the attachment of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus; posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint with evidence of posterior and anterior labral tears; and large glenohumeral joint effusion.” The patient opted for surgical repair and underwent left shoulder arthroscopy with extensive débridement, open rotator cuff repair, open greater tuberosity reduction and internal fixation, and open biceps tenodesis. He was then discharged back to an extended-care facility to continue rehabilitation. One and a half months after surgery, he started the physical therapy phase of the massive rotator cuff repair protocol. He declined reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).

Four and a half months after injury (3 months after surgery), the left shoulder demonstrated 20° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested), and the right shoulder demonstrated 30° of flexion and 70° to 110° of abduction (external rotation not tested). He had no instability and no lag with good external rotation.

Six months after injury, the patient still could not lift his arms above his head. He likely would not be able to do so without RTSA, which he again declined. He continued physical therapy and clinical follow-ups.

Discussion

Although inferior shoulder dislocations are rare, they carry a higher rate of complications, most of which our patient experienced. Our patient had bilateral humeral head fractures, which occur in 80% of cases.6 Postreduction CT showed the degree of his fractures (Figure 3).

Our patient also had reduced sensation in the axillary nerve distribution, which occurs in 60% of inferior dislocations.6 Axillary nerve injuries produce numbness in the lateral arm or posterior shoulder and weakness with shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation.7 In our patient’s case, sensation returned after reduction, which is typical (most patients have a positive prognosis).8 As the shoulder dislocates inferiorly, the humeral head tears the glenohumeral capsule inferiorly, which can damage the axillary artery. This artery becomes the brachial and eventually the radial and ulnar arteries, which can have decreased or absent pulses with injury.

Inferior dislocations are also associated with abundant soft-tissue injuries, including torn rotator cuff, shoulder capsule avulsion, and disruption of adjacent muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis, pectoralis major).9Luxatio erecta is relatively easy to diagnose given the unmistakable arm positioning. The key for the physician is first to assess for the many possible complications, then to administer the proper sedation and analgesia for reduction, and finally to reassess for complications.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E328-E330. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Camarda L, Martorana U, D’Arienzo M. A case of bilateral luxatio erecta. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(2):97-99.

2. Musmeci E, Gaspari D, Sandri A, Regis D, Bartolozzi P. Bilateral luxatio erecta humeri associated with a unilateral brachial plexus and bilateral rotator cuff injuries: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(7):498-500.

3. Lam AC, Shih RD. Luxatio erecta complicated by anterior shoulder dislocation during reduction. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):28-30.

4. Nho SJ, Dodson CC, Bardzik KF, Brophy RH, Domb BG, MacGillivray JD. The two-step maneuver for closed reduction of inferior glenohumeral dislocation (luxatio erecta to anterior dislocation to reduction). J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(5):354-357.

5. Beattie TF, Steedman DJ, McGowan A, Robertson CE. A comparison of the Milch and Kocher techniques for acute anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury. 1986;17(5):349-352.

6. Mallon WJ, Bassett FH 3rd, Goldner RD. Luxatio erecta: the inferior glenohumeral dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 1990;4(1):19-24.

7. Miller T. Peripheral nerve injuries at the shoulder. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;6(4):170-183.

8. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):423-426.

9. Garcia R, Ponsky T, Brody F, Long J. Bilateral luxatio erecta complicated by venous thrombosis. J Trauma. 2006;60(5):1132-1134.

1. Camarda L, Martorana U, D’Arienzo M. A case of bilateral luxatio erecta. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(2):97-99.

2. Musmeci E, Gaspari D, Sandri A, Regis D, Bartolozzi P. Bilateral luxatio erecta humeri associated with a unilateral brachial plexus and bilateral rotator cuff injuries: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(7):498-500.

3. Lam AC, Shih RD. Luxatio erecta complicated by anterior shoulder dislocation during reduction. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):28-30.

4. Nho SJ, Dodson CC, Bardzik KF, Brophy RH, Domb BG, MacGillivray JD. The two-step maneuver for closed reduction of inferior glenohumeral dislocation (luxatio erecta to anterior dislocation to reduction). J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(5):354-357.

5. Beattie TF, Steedman DJ, McGowan A, Robertson CE. A comparison of the Milch and Kocher techniques for acute anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury. 1986;17(5):349-352.

6. Mallon WJ, Bassett FH 3rd, Goldner RD. Luxatio erecta: the inferior glenohumeral dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 1990;4(1):19-24.

7. Miller T. Peripheral nerve injuries at the shoulder. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;6(4):170-183.

8. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):423-426.

9. Garcia R, Ponsky T, Brody F, Long J. Bilateral luxatio erecta complicated by venous thrombosis. J Trauma. 2006;60(5):1132-1134.

Intrauterine Device Migration

Although intrauterine devices (IUDs) are a mainstay of reversible contraception, they do carry the risk of complications, including septic abortion, abscess formation, ectopic pregnancy, bleeding, and uterine perforation.1 Although perforation is a relatively rare complication, occurring in 0.3 to 2.6 per 1,000 insertions for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and 0.3 to 2.2 per 1,000 insertions for copper IUDs, it can lead to serious complications, including IUD migration to various sites.2 Most patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with abdominal pain and bleeding; however, 30% of patients are asymptomatic.3

This article presents the case of a young woman who was diagnosed with IUD migration into the abdominal cavity. I discuss the management of this uncommon complication, and stress the importance of adequate education for both patients and health care providers regarding proper surveillance.

Case

A 33-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 4, live 4) presented to our ED for evaluation of rectal bleeding that she had experienced intermittently over the past 2 years. She reported that the first occurrence had been 2 years ago, starting a few weeks after she had a cesarean delivery. The patient described the initial episode as bright red blood mixed with stool. She stated that subsequent episodes had been intermittent, felt as if she were “passing rocks” through her abdomen and rectum, and were accompanied by streaks of blood covering her stool. The day before the patient presented to the ED, she had experienced a second episode of a large bowel movement mixed with blood and accompanied by weakness, which prompted her to seek treatment.

A review of the patient’s symptoms revealed abdominal pain and weakness. She denied any bleeding disorders, fever, chills, sick contacts, anal trauma, presyncope, syncope, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. She further denied any prescription-medication use, illicit drug use, or smoking, but admitted to occasional alcohol use. Her last menstrual period had been 3 weeks prior to presentation. She denied any history of cancer or abnormal Pap smears. Her gynecologic history was significant for chlamydia and trichomoniasis, for which she had been treated. The patient’s surgical history was pertinent for umbilical hernia repair with surgical mesh.

On physical examination, the patient was mildly hypotensive (blood pressure, 97/78 mm Hg) but had a normal heart rate. She had mild conjunctival pallor. The abdominal examination exhibited normoactive bowel sounds with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness to deep palpation, but without rebound, guarding, or distension. Rectal examination revealed a small internal hemorrhoid at the 6 o’clock position (no active bleeding) and an external hemorrhoid with some tenderness to palpation; the external hemorrhoid was not thrombosed, had no signs of infection, and was the same color as the surrounding skin.

A fecal occult blood screen was negative, and a serum pregnancy test was also negative. Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and urinalysis were all unremarkable and within normal ranges. Abdominal X-ray revealed a nonobstructive stool pattern and a foreign body, likely in the abdominal cavity, which appeared to be an IUD (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast were performed to accurately locate the foreign body and to assess for any complications. The CT scans revealed an IUD outside of the uterus, between loops of the transverse colon within the left midabdomen (Figure 2). There were no signs of infection, fluid, or free air. There were also findings of colonic diverticula and narrowed lumen, which were suggestive of diverticulosis.

The patient stated that the IUD had been placed several months after the vaginal birth of her third child. She continued to have normal menstrual periods with the IUD in place. Seven years later, she became pregnant with her fourth child, who was delivered via cesarean, secondary to fetal malpositioning. The IUD was not removed during the cesarean delivery.

Based on the CT scan findings, gynecology services was consulted, and the gynecologist recommended immediate follow-up in a gynecology clinic. The patient was discharged on a bowel regimen. She was assessed in a gynecology clinic 4 days later, where she was found to have a mobile retroverted uterus without tenderness or signs of infection. She underwent exploratory laparoscopy, during which the IUD was removed from the omentum in the left upper abdomen without complications.

Discussion

The IUD has had great acceptance among women since the 1960s. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 14.3% of women used an IUD in 2009.4 Although complications are rare, the most serious are perforation of the uterus and migration of the IUD into adjacent organs.1

Risk factors of uterine perforation include clinician inexperience in IUD placement, an immobile uterus, a retroverted uterus, and the presence of a myometrial defect.4 Heinemann et al2 also suggested that breastfeeding and IUD placement soon after a delivery (≤36 weeks) are independent risk factors, and the presence of both factors has an additive increase in risk of perforation.

Primary rupture of the uterus has been reported at the time of IUD insertion, but secondary or delayed rupture is more common and seems to be due to the spasms of the uterus.5 Although 85% of perforations do not affect other organs, the remaining 15% lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs.6 The most frequent sites of migration are to the omentum (26.7%), pouch of Douglas (21.5%), large bowel (10.4%), myometrium (7.4%), broad ligament (6.7%), abdominal cavity (5.2%), adhesion to ileal loop serosa (4.4%) or large bowel serosa (3.7%), and mesentery (3%).7 Rare sites are to the appendix, abdominal wall, ovary, and bladder.7

Intrauterine device migration should be suspected in patients who become pregnant after IUD placement (as was the case for our patient), when the “threads” or string cannot be located while attempting to remove an IUD, or when a patient has an “expulsed” IUD without observation of the device thereafter. Even though expulsion of the device happens in approximately 8 per 1,000 insertions, uterine perforation is also a possibility in the case of a “lost” IUD.8 When a lost IUD is suspected, a pelvic examination should be performed to assess for threads or string location. If unsuccessful, ultrasound or plain abdominal radiographic imaging may be used to locate the IUD. Once IUD migration has been confirmed, cross-sectional imaging such as CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is suggested to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4 If colonic involvement is suspected, colonoscopy can be used to confirm the diagnosis before operative removal.4

Although management of a migrated IUD in an asymptomatic patient is controversial, there appears to be a consensus that all extrauterine devices should be removed unless the patient’s surgical risk is excessive.1,5,9 Retrieval of an IUD can be performed by laparotomy or laparoscopy.10,11

To avoid these complications and interventions, IUDs should be inserted by an appropriately trained professional, after proper patient selection. These devices should be monitored by periodic examinations, either by medical professionals or by well-informed patients. This can be done by either checking for the threads or string in the cervical opening or by ultrasound imaging to confirm the location of the IUD.

Conclusion

Although many patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with symptoms, approximately 30% are asymptomatic.3 If a patient has a lost IUD and the threads or string is not visible during pelvic examination, appropriate work-up, including transvaginal or transabdominal ultrasound or radiographs, should be obtained to confirm the position of the IUD. If IUD migration is suspected, cross-sectional imaging, such as CT scans or MRI, is recommended to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4

Even though only 15% of migrated IUDs lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs,6 surgical removal of the IUD is advised regardless of the presence of symptoms or identified complications. Importantly, to prevent the delayed diagnosis and morbidity of IUD migration, patients with IUDs should be educated about the possibility of migration and the importance of regular self-examination for missing threads or string.

1. Hoşcan MB, Koşar A, Gümüştaş U, Güney M. Intravesical migration of intrauterine device resulting in pregnancy. Int J Urol. 2006;13(3):301-302.

2. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Minh TD. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274-279.

3. Singh SP, Mangla D, Chawan J, Haq AU. Asymptomatic presentation of silent uterine perforation by Cu-T 380A: a case report with review of literature. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2014;3(4):1157-1159.

4. Akpinar F, Ozgur EN, Yilmaz S, Ustaoglu O. Sigmoid colon migration of an intrauterine device. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:207659.

5. Rahnemai-Azar AA, Apfel T, Naghshizadian R, Cosgrove JM, Farkas DT. Laparoscopic removal of migrated intrauterine device embedded in intestine. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

6. Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. II. Diagnostic methods, prevention, and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36(8):401-417.

7. Gill RS, Mok D, Hudson M, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S. Laparoscopic removal of an intra-abdominal intrauterine device: case and systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(1):15-18.

8. Paterson H, Ashton J, Harrison-Woolrych M. A nationwide cohort study of the use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in New Zealand adolescents. Contraception. 2009;79(6):433-438.

9. Gorsline JC, Osborne NG. Management of the missing intrauterine contraceptive device: report of a case. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(2):228-229.

10. Mederos R, Humaran L, Minervini D. Surgical removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report. Int J Surg. 2008;6(6):e60-e62.

11. Chi E, Rosenfeld D, Sokol TP. Laparoscopic removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2005;71(12):1055-1057.

Although intrauterine devices (IUDs) are a mainstay of reversible contraception, they do carry the risk of complications, including septic abortion, abscess formation, ectopic pregnancy, bleeding, and uterine perforation.1 Although perforation is a relatively rare complication, occurring in 0.3 to 2.6 per 1,000 insertions for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and 0.3 to 2.2 per 1,000 insertions for copper IUDs, it can lead to serious complications, including IUD migration to various sites.2 Most patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with abdominal pain and bleeding; however, 30% of patients are asymptomatic.3

This article presents the case of a young woman who was diagnosed with IUD migration into the abdominal cavity. I discuss the management of this uncommon complication, and stress the importance of adequate education for both patients and health care providers regarding proper surveillance.

Case

A 33-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 4, live 4) presented to our ED for evaluation of rectal bleeding that she had experienced intermittently over the past 2 years. She reported that the first occurrence had been 2 years ago, starting a few weeks after she had a cesarean delivery. The patient described the initial episode as bright red blood mixed with stool. She stated that subsequent episodes had been intermittent, felt as if she were “passing rocks” through her abdomen and rectum, and were accompanied by streaks of blood covering her stool. The day before the patient presented to the ED, she had experienced a second episode of a large bowel movement mixed with blood and accompanied by weakness, which prompted her to seek treatment.

A review of the patient’s symptoms revealed abdominal pain and weakness. She denied any bleeding disorders, fever, chills, sick contacts, anal trauma, presyncope, syncope, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. She further denied any prescription-medication use, illicit drug use, or smoking, but admitted to occasional alcohol use. Her last menstrual period had been 3 weeks prior to presentation. She denied any history of cancer or abnormal Pap smears. Her gynecologic history was significant for chlamydia and trichomoniasis, for which she had been treated. The patient’s surgical history was pertinent for umbilical hernia repair with surgical mesh.

On physical examination, the patient was mildly hypotensive (blood pressure, 97/78 mm Hg) but had a normal heart rate. She had mild conjunctival pallor. The abdominal examination exhibited normoactive bowel sounds with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness to deep palpation, but without rebound, guarding, or distension. Rectal examination revealed a small internal hemorrhoid at the 6 o’clock position (no active bleeding) and an external hemorrhoid with some tenderness to palpation; the external hemorrhoid was not thrombosed, had no signs of infection, and was the same color as the surrounding skin.

A fecal occult blood screen was negative, and a serum pregnancy test was also negative. Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and urinalysis were all unremarkable and within normal ranges. Abdominal X-ray revealed a nonobstructive stool pattern and a foreign body, likely in the abdominal cavity, which appeared to be an IUD (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast were performed to accurately locate the foreign body and to assess for any complications. The CT scans revealed an IUD outside of the uterus, between loops of the transverse colon within the left midabdomen (Figure 2). There were no signs of infection, fluid, or free air. There were also findings of colonic diverticula and narrowed lumen, which were suggestive of diverticulosis.

The patient stated that the IUD had been placed several months after the vaginal birth of her third child. She continued to have normal menstrual periods with the IUD in place. Seven years later, she became pregnant with her fourth child, who was delivered via cesarean, secondary to fetal malpositioning. The IUD was not removed during the cesarean delivery.

Based on the CT scan findings, gynecology services was consulted, and the gynecologist recommended immediate follow-up in a gynecology clinic. The patient was discharged on a bowel regimen. She was assessed in a gynecology clinic 4 days later, where she was found to have a mobile retroverted uterus without tenderness or signs of infection. She underwent exploratory laparoscopy, during which the IUD was removed from the omentum in the left upper abdomen without complications.

Discussion

The IUD has had great acceptance among women since the 1960s. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 14.3% of women used an IUD in 2009.4 Although complications are rare, the most serious are perforation of the uterus and migration of the IUD into adjacent organs.1

Risk factors of uterine perforation include clinician inexperience in IUD placement, an immobile uterus, a retroverted uterus, and the presence of a myometrial defect.4 Heinemann et al2 also suggested that breastfeeding and IUD placement soon after a delivery (≤36 weeks) are independent risk factors, and the presence of both factors has an additive increase in risk of perforation.

Primary rupture of the uterus has been reported at the time of IUD insertion, but secondary or delayed rupture is more common and seems to be due to the spasms of the uterus.5 Although 85% of perforations do not affect other organs, the remaining 15% lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs.6 The most frequent sites of migration are to the omentum (26.7%), pouch of Douglas (21.5%), large bowel (10.4%), myometrium (7.4%), broad ligament (6.7%), abdominal cavity (5.2%), adhesion to ileal loop serosa (4.4%) or large bowel serosa (3.7%), and mesentery (3%).7 Rare sites are to the appendix, abdominal wall, ovary, and bladder.7

Intrauterine device migration should be suspected in patients who become pregnant after IUD placement (as was the case for our patient), when the “threads” or string cannot be located while attempting to remove an IUD, or when a patient has an “expulsed” IUD without observation of the device thereafter. Even though expulsion of the device happens in approximately 8 per 1,000 insertions, uterine perforation is also a possibility in the case of a “lost” IUD.8 When a lost IUD is suspected, a pelvic examination should be performed to assess for threads or string location. If unsuccessful, ultrasound or plain abdominal radiographic imaging may be used to locate the IUD. Once IUD migration has been confirmed, cross-sectional imaging such as CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is suggested to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4 If colonic involvement is suspected, colonoscopy can be used to confirm the diagnosis before operative removal.4

Although management of a migrated IUD in an asymptomatic patient is controversial, there appears to be a consensus that all extrauterine devices should be removed unless the patient’s surgical risk is excessive.1,5,9 Retrieval of an IUD can be performed by laparotomy or laparoscopy.10,11

To avoid these complications and interventions, IUDs should be inserted by an appropriately trained professional, after proper patient selection. These devices should be monitored by periodic examinations, either by medical professionals or by well-informed patients. This can be done by either checking for the threads or string in the cervical opening or by ultrasound imaging to confirm the location of the IUD.

Conclusion

Although many patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with symptoms, approximately 30% are asymptomatic.3 If a patient has a lost IUD and the threads or string is not visible during pelvic examination, appropriate work-up, including transvaginal or transabdominal ultrasound or radiographs, should be obtained to confirm the position of the IUD. If IUD migration is suspected, cross-sectional imaging, such as CT scans or MRI, is recommended to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4

Even though only 15% of migrated IUDs lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs,6 surgical removal of the IUD is advised regardless of the presence of symptoms or identified complications. Importantly, to prevent the delayed diagnosis and morbidity of IUD migration, patients with IUDs should be educated about the possibility of migration and the importance of regular self-examination for missing threads or string.

Although intrauterine devices (IUDs) are a mainstay of reversible contraception, they do carry the risk of complications, including septic abortion, abscess formation, ectopic pregnancy, bleeding, and uterine perforation.1 Although perforation is a relatively rare complication, occurring in 0.3 to 2.6 per 1,000 insertions for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and 0.3 to 2.2 per 1,000 insertions for copper IUDs, it can lead to serious complications, including IUD migration to various sites.2 Most patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with abdominal pain and bleeding; however, 30% of patients are asymptomatic.3

This article presents the case of a young woman who was diagnosed with IUD migration into the abdominal cavity. I discuss the management of this uncommon complication, and stress the importance of adequate education for both patients and health care providers regarding proper surveillance.

Case

A 33-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 4, live 4) presented to our ED for evaluation of rectal bleeding that she had experienced intermittently over the past 2 years. She reported that the first occurrence had been 2 years ago, starting a few weeks after she had a cesarean delivery. The patient described the initial episode as bright red blood mixed with stool. She stated that subsequent episodes had been intermittent, felt as if she were “passing rocks” through her abdomen and rectum, and were accompanied by streaks of blood covering her stool. The day before the patient presented to the ED, she had experienced a second episode of a large bowel movement mixed with blood and accompanied by weakness, which prompted her to seek treatment.

A review of the patient’s symptoms revealed abdominal pain and weakness. She denied any bleeding disorders, fever, chills, sick contacts, anal trauma, presyncope, syncope, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. She further denied any prescription-medication use, illicit drug use, or smoking, but admitted to occasional alcohol use. Her last menstrual period had been 3 weeks prior to presentation. She denied any history of cancer or abnormal Pap smears. Her gynecologic history was significant for chlamydia and trichomoniasis, for which she had been treated. The patient’s surgical history was pertinent for umbilical hernia repair with surgical mesh.

On physical examination, the patient was mildly hypotensive (blood pressure, 97/78 mm Hg) but had a normal heart rate. She had mild conjunctival pallor. The abdominal examination exhibited normoactive bowel sounds with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness to deep palpation, but without rebound, guarding, or distension. Rectal examination revealed a small internal hemorrhoid at the 6 o’clock position (no active bleeding) and an external hemorrhoid with some tenderness to palpation; the external hemorrhoid was not thrombosed, had no signs of infection, and was the same color as the surrounding skin.

A fecal occult blood screen was negative, and a serum pregnancy test was also negative. Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and urinalysis were all unremarkable and within normal ranges. Abdominal X-ray revealed a nonobstructive stool pattern and a foreign body, likely in the abdominal cavity, which appeared to be an IUD (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast were performed to accurately locate the foreign body and to assess for any complications. The CT scans revealed an IUD outside of the uterus, between loops of the transverse colon within the left midabdomen (Figure 2). There were no signs of infection, fluid, or free air. There were also findings of colonic diverticula and narrowed lumen, which were suggestive of diverticulosis.

The patient stated that the IUD had been placed several months after the vaginal birth of her third child. She continued to have normal menstrual periods with the IUD in place. Seven years later, she became pregnant with her fourth child, who was delivered via cesarean, secondary to fetal malpositioning. The IUD was not removed during the cesarean delivery.

Based on the CT scan findings, gynecology services was consulted, and the gynecologist recommended immediate follow-up in a gynecology clinic. The patient was discharged on a bowel regimen. She was assessed in a gynecology clinic 4 days later, where she was found to have a mobile retroverted uterus without tenderness or signs of infection. She underwent exploratory laparoscopy, during which the IUD was removed from the omentum in the left upper abdomen without complications.

Discussion

The IUD has had great acceptance among women since the 1960s. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 14.3% of women used an IUD in 2009.4 Although complications are rare, the most serious are perforation of the uterus and migration of the IUD into adjacent organs.1

Risk factors of uterine perforation include clinician inexperience in IUD placement, an immobile uterus, a retroverted uterus, and the presence of a myometrial defect.4 Heinemann et al2 also suggested that breastfeeding and IUD placement soon after a delivery (≤36 weeks) are independent risk factors, and the presence of both factors has an additive increase in risk of perforation.

Primary rupture of the uterus has been reported at the time of IUD insertion, but secondary or delayed rupture is more common and seems to be due to the spasms of the uterus.5 Although 85% of perforations do not affect other organs, the remaining 15% lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs.6 The most frequent sites of migration are to the omentum (26.7%), pouch of Douglas (21.5%), large bowel (10.4%), myometrium (7.4%), broad ligament (6.7%), abdominal cavity (5.2%), adhesion to ileal loop serosa (4.4%) or large bowel serosa (3.7%), and mesentery (3%).7 Rare sites are to the appendix, abdominal wall, ovary, and bladder.7

Intrauterine device migration should be suspected in patients who become pregnant after IUD placement (as was the case for our patient), when the “threads” or string cannot be located while attempting to remove an IUD, or when a patient has an “expulsed” IUD without observation of the device thereafter. Even though expulsion of the device happens in approximately 8 per 1,000 insertions, uterine perforation is also a possibility in the case of a “lost” IUD.8 When a lost IUD is suspected, a pelvic examination should be performed to assess for threads or string location. If unsuccessful, ultrasound or plain abdominal radiographic imaging may be used to locate the IUD. Once IUD migration has been confirmed, cross-sectional imaging such as CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is suggested to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4 If colonic involvement is suspected, colonoscopy can be used to confirm the diagnosis before operative removal.4

Although management of a migrated IUD in an asymptomatic patient is controversial, there appears to be a consensus that all extrauterine devices should be removed unless the patient’s surgical risk is excessive.1,5,9 Retrieval of an IUD can be performed by laparotomy or laparoscopy.10,11

To avoid these complications and interventions, IUDs should be inserted by an appropriately trained professional, after proper patient selection. These devices should be monitored by periodic examinations, either by medical professionals or by well-informed patients. This can be done by either checking for the threads or string in the cervical opening or by ultrasound imaging to confirm the location of the IUD.

Conclusion

Although many patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with symptoms, approximately 30% are asymptomatic.3 If a patient has a lost IUD and the threads or string is not visible during pelvic examination, appropriate work-up, including transvaginal or transabdominal ultrasound or radiographs, should be obtained to confirm the position of the IUD. If IUD migration is suspected, cross-sectional imaging, such as CT scans or MRI, is recommended to rule out adjacent organ involvement before considering surgical removal.4

Even though only 15% of migrated IUDs lead to complications in the adjacent visceral organs,6 surgical removal of the IUD is advised regardless of the presence of symptoms or identified complications. Importantly, to prevent the delayed diagnosis and morbidity of IUD migration, patients with IUDs should be educated about the possibility of migration and the importance of regular self-examination for missing threads or string.

1. Hoşcan MB, Koşar A, Gümüştaş U, Güney M. Intravesical migration of intrauterine device resulting in pregnancy. Int J Urol. 2006;13(3):301-302.

2. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Minh TD. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274-279.

3. Singh SP, Mangla D, Chawan J, Haq AU. Asymptomatic presentation of silent uterine perforation by Cu-T 380A: a case report with review of literature. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2014;3(4):1157-1159.

4. Akpinar F, Ozgur EN, Yilmaz S, Ustaoglu O. Sigmoid colon migration of an intrauterine device. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:207659.

5. Rahnemai-Azar AA, Apfel T, Naghshizadian R, Cosgrove JM, Farkas DT. Laparoscopic removal of migrated intrauterine device embedded in intestine. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

6. Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. II. Diagnostic methods, prevention, and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36(8):401-417.

7. Gill RS, Mok D, Hudson M, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S. Laparoscopic removal of an intra-abdominal intrauterine device: case and systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(1):15-18.

8. Paterson H, Ashton J, Harrison-Woolrych M. A nationwide cohort study of the use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in New Zealand adolescents. Contraception. 2009;79(6):433-438.

9. Gorsline JC, Osborne NG. Management of the missing intrauterine contraceptive device: report of a case. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(2):228-229.

10. Mederos R, Humaran L, Minervini D. Surgical removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report. Int J Surg. 2008;6(6):e60-e62.

11. Chi E, Rosenfeld D, Sokol TP. Laparoscopic removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2005;71(12):1055-1057.

1. Hoşcan MB, Koşar A, Gümüştaş U, Güney M. Intravesical migration of intrauterine device resulting in pregnancy. Int J Urol. 2006;13(3):301-302.

2. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Minh TD. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274-279.

3. Singh SP, Mangla D, Chawan J, Haq AU. Asymptomatic presentation of silent uterine perforation by Cu-T 380A: a case report with review of literature. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2014;3(4):1157-1159.

4. Akpinar F, Ozgur EN, Yilmaz S, Ustaoglu O. Sigmoid colon migration of an intrauterine device. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:207659.

5. Rahnemai-Azar AA, Apfel T, Naghshizadian R, Cosgrove JM, Farkas DT. Laparoscopic removal of migrated intrauterine device embedded in intestine. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

6. Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. II. Diagnostic methods, prevention, and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36(8):401-417.

7. Gill RS, Mok D, Hudson M, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S. Laparoscopic removal of an intra-abdominal intrauterine device: case and systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(1):15-18.

8. Paterson H, Ashton J, Harrison-Woolrych M. A nationwide cohort study of the use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in New Zealand adolescents. Contraception. 2009;79(6):433-438.

9. Gorsline JC, Osborne NG. Management of the missing intrauterine contraceptive device: report of a case. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(2):228-229.

10. Mederos R, Humaran L, Minervini D. Surgical removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report. Int J Surg. 2008;6(6):e60-e62.

11. Chi E, Rosenfeld D, Sokol TP. Laparoscopic removal of an intrauterine device perforating the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2005;71(12):1055-1057.

Dengue Fever: Two Unexpected Findings

Dengue fever is the most commonly transmitted arboviral disease in the world, affecting an estimated 2.5 billion people who live in areas endemic to the virus. This exposure yields an annual incidence of 100 million cases of dengue, which translates into 250,000 cases of hemorrhagic fever. With an expanding geographic distribution and increasing number of epidemics, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified dengue as a major public health concern.1 Enhanced globalization and changing climate patterns have resulted in a dramatic increase in the incidence of dengue in both North and Central America. Aggregate North and Central American data from 2010 to the present revealed over 1.7 million cases of dengue, nearly 80,000 of which were severe, and 747 deaths.2 Based on these statistics, dengue fever should be considered in the differential diagnosis of febrile ED patients in the developed world who had a history of recent travel. We present two cases that highlight the complexity of diagnosis and novel complications associated with dengue fever.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 24-year-old man presented to the ED with a 4-day history of intermittent fever of up to 102.02°F, which was accompanied by chills, myalgia, and rigors. The patient stated that he had visited Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia 8 days prior to presentation, and had experienced mosquito bites daily throughout his travels. He further noted that his symptoms had improved on day 3 of his illness, but acutely worsened on day 4, which prompted him to visit the ED. The patient’s primary complaint was a severe retro-orbital headache, fever, and one episode of epistaxis.

On physical examination, the patient had conjunctivitis and hepatosplenomegaly, but otherwise appeared well. His laboratory evaluation was significant for leukopenia (white blood cell [WBC] count, 2.40 x 109/L), thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 123 x 109/L), and a positive mononuclear spot test. Both dengue immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) tests sent from the ED were negative. Based on the patient’s thrombocytopenia and epistaxis, as well as concerns that the patient was entering into the critical phase of dengue fever, he was admitted to the inpatient hospital for observation.

The patient’s course improved during his stay with symptomatic treatment and blood-count monitoring, and he was discharged home on hospital day 3. He followed up at our hospital travel clinic the day after discharge; a repeat dengue IgM test taken during this visit came back positive.

Case 2

A 51-year-old man presented to the ED with a 3-day history of intermittent fever and diffuse myalgia. He reported chills, night sweats, and the feeling of abdominal fullness. He denied nausea, vomiting, or changes in the character of his stool. He had no known sick contacts, but reported he had traveled from the Philippines 3 days prior to presentation and that his symptoms had developed en route to the United States. The patient also denied any known tick, mosquito, or animal exposures. He said he had treated his symptoms with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Prior to his arrival at the ED, he had twice presented to a walk-in clinic earlier that day. Repeated laboratory testing at the ED showed a decrease in WBC count from 42.0 x 109/L to 31.0 x 109/L, as well as a declining platelet count from 123 x 109/L to 87 x 109/L. On physical examination, the patient was ill-appearing, diaphoretic, and had a temperature of 100.6°F. His vital signs were otherwise within normal limits.

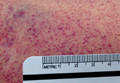

With the exception of a mild diffuse petechial rash on the patient’s thighs bilaterally, the physical examination was unrevealing. A tourniquet test (TT) to assess capillary fragility was performed at bedside, and yielded a positive result (Figure 1). Work-up further demonstrated a declining WBC of 2.70 x 109/L and declining platelet count of 65 x 109/L.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test confirmed a diagnosis of dengue, with a positive dengue type-4 (DEN-4) serotype detection. Supportive care was initiated, and the patient was admitted to the inpatient hospital for continued treatment. He was discharged home on hospital day 5; however, he returned to the ED later that day with increasing headache and left flank pain. Work-up included axial and coronal computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis, which revealed hematuria and a left upper pole renal infarction surrounded by mild perinephric fat stranding (Figure 2a and 2b) with maintenance of left renal artery/vein patency.

The patient was admitted to an inpatient floor, where symptomatic management was employed. He underwent unrevealing bubble echocardiography and lower extremity Doppler ultrasound imaging, and anticoagulation therapy was initiated per a consultation with hematology services. The patient was discharged home in improved, stable condition on hospital day 8.

Discussion

Dengue virus is a single-stranded, nonsegmented RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. Four major subtypes exist: DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4. Lifelong serotype-specific immunity is conferred following infection. The virus is transmitted by the female Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is found worldwide but has a predilection for tropical and subtropical regions. The Aedes aegypti mosquito remains an effective vector secondary to its diurnal feeding habit and nearly imperceptible bite.1,3

The viral incubation period for dengue is typically 3 to 7 days4; therefore, dengue is highly unlikely in patients whose symptoms begin more than 2 weeks after departure from an endemic area. Replication primarily occurs in the regional lymph nodes and disseminates through the lymphatic system and bloodstream.1

The 1997 WHO guidelines previously classified dengue into three categories: undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever (which was further classified by four severity grades, with grades III and IV defined as dengue shock syndrome). However, changes in epidemiology of the disease and reports of difficulty applying the criteria in the clinical setting led to reclassification of dengue on a continuum from dengue to severe dengue in the WHO’s updated 2009 guidelines.4

Signs and Symptoms

The ramifications of dengue infection can range from asymptomatic (typically in young, immunocompetent patients) to lethal. Key symptoms of dengue fever include nausea, vomiting, fever, respiratory symptoms, morbilliform or maculopapular rash, and headache or retro-orbital pain. In addition, arthralgia (hence the colloquial name for dengue of “breakbone fever”), myalgia, and conjunctivitis may exist.3,4 Fever usually lasts 5 to 7 days and can be biphasic, with a return of symptoms after the initial resolution as seen in case report 1.4 Severe dengue is characterized by capillary leakage, hemorrhage, or end-organ damage.3-5 The most common bleeding sites are the skin, nose, and gums.

Diagnosis

Bedside evaluation for dengue can be performed with the TT—one of the WHO’s case definitions for dengue.6 This is accomplished by placing a manual blood pressure (BP) cuff on the arm and inflating it to halfway between systolic and diastolic BP for 5 minutes. The test is positive for dengue if more than 10 petechiae appear per 1-inch (2.5-cm) square below the antecubital fossa.7 Of note, the test has poor sensitivity (51.6%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 33-69), but good specificity (82.4%, 95% CI, 76-87).7,8 A positive TT combined with leukopenia increases the sensitivity to 93.9%, [95% CI, 89-96].7 While not specific to dengue infection, in the right clinical scenario, the TT is a simple bedside test to help confirm the diagnosis and is extremely useful in resource-limited settings.

During the initial days of illness, the virus may be detected by PCR, as viremia and fever usually correlate. Once defervescence occurs, IgM and then IgG antibodies become detectable. When using these antibody tests to evaluate for dengue, clinicians should be aware of cross-reactivity with other flavivirus infections, such as yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis (including immunological cross-reactivity).1 New diagnostic modalities include enzyme immunoassays that can detect dengue viral RNA within 24 to 48 hours, and viral antigen-detection kits, which can yield results in less than 1 hour.4

Aside from advanced laboratory testing, worsening thrombocytopenia in light of a rising hematocrit can be highly suggestive of dengue. Leukopenia with lymphopenia and mild elevation of hepatic enzymes (typically 2 to 5 times the upper limits of the normal reference range) are also often seen in active infections.1 The occurrence of these signs in conjunction with a rapid reduction in the platelets often signals transition to the critical phase of plasma leakage.1,4

Treatment

Treatment of dengue consists of supportive care and transfusion when necessary. The WHO recommends strict observation of patients with suspected dengue who have warning signs of severe disease (eg, abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, hepatomegaly, rapid increase in hematocrit with concomitant drop in platelet count). Inpatient treatment centers on judicious fluid management, trending blood count parameters, and monitoring for signs of plasma leakage and hemorrhage. Fluid resuscitation is titrated to optimize central and peripheral circulation and end-organ perfusion. Blood-product administration should be reserved for suspected or severe bleeding.4

While dengue fever was the final diagnosis in both of our case presentations, these cases also highlight key diagnostic and treatment dilemmas associated with dengue. The patient in the first case report demonstrated the characteristic biphasic fever seen with dengue—resolution of symptoms on day 3, but then return of fever and symptoms on day 4. Often the dengue-specific antibodies are not formed until after the resolution of fever. This patient represents a classic example of dengue as the serologic studies sent on day 4 of the patient’s illness were negative but then turned positive on day 7, illustrating the need for high clinical suspicion and underscoring the importance of initiating treatment despite laboratory confirmation.

Further, regarding the patient in the second case, though proteinuria, hematuria, acute renal failure, and glomerulonephritis are previously described renal complications of dengue,9 a thorough literature search yielded no prior published accounts of renal infarction. Given the patient’s previous healthy status and the lack of other hypothesis as to the mechanism of injury, we suspect this patient’s renal infarction was due to the transient hypercoagulability characteristic of dengue and responsible for other clinical manifestations of the disease.

Conclusion

In addition to more prevalent illnesses such as malaria, acute traveler’s diarrhea, and respiratory tract infections, dengue fever should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating a febrile patient who has a history of recent travel to countries where dengue is endemic. A high clinical suspicion, combined with a thorough history and physical examination, is essential to making the diagnosis.

Both of our case reports demonstrate some of the diagnostic limitations in the acute setting, and the breadth of clinical complications that can occur in this complex disease. With the increasing prevalence of dengue fever in North and Central America, it is likely that patients with the disease will present to EDs in the United States. Early diagnosis and awareness of potential complications can lead to timely initiation of life-saving supportive care.

1. Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):924-932. dpo:10.1056/NEJMra041927

2. Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Number of reported cases of dengue and severe dengue (SD), Region of the Americas (by country and subregion). Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization. http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=&gid=35610&lang=es. Updated August 5, 2016. Accessed August 17, 2016.

3. Whitehorn J, Farrar J. Dengue. Clin Med (Lond). 2011;11(5):483-487.

4. World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. New Edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/dengue-diagnosis.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2016.

5. Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370(9599):1644-1652. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue Clinical Case Management E-learning. http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/training/cme/ccm/page73112.html; http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/training/cme/ccm/Tourniquet%20Test_F.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2016.

7. Gregory CJ, Lorenzi OD, Colón L, et al. Utility of the tourniquet test and the white blood cell count to differentiate dengue among acute febrile illnesses in the emergency room. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(12):e1400.

8. Mayxay M, Phetsouvanh R, Moore CE, et al. Predictive diagnostic value of the tourniquet test for the diagnosis of dengue infection in adults. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(1):127-133.

9. Lizarraga KJ, Nayer A. Dengue-associated kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2014;3(2):57-62.

Dengue fever is the most commonly transmitted arboviral disease in the world, affecting an estimated 2.5 billion people who live in areas endemic to the virus. This exposure yields an annual incidence of 100 million cases of dengue, which translates into 250,000 cases of hemorrhagic fever. With an expanding geographic distribution and increasing number of epidemics, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified dengue as a major public health concern.1 Enhanced globalization and changing climate patterns have resulted in a dramatic increase in the incidence of dengue in both North and Central America. Aggregate North and Central American data from 2010 to the present revealed over 1.7 million cases of dengue, nearly 80,000 of which were severe, and 747 deaths.2 Based on these statistics, dengue fever should be considered in the differential diagnosis of febrile ED patients in the developed world who had a history of recent travel. We present two cases that highlight the complexity of diagnosis and novel complications associated with dengue fever.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 24-year-old man presented to the ED with a 4-day history of intermittent fever of up to 102.02°F, which was accompanied by chills, myalgia, and rigors. The patient stated that he had visited Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia 8 days prior to presentation, and had experienced mosquito bites daily throughout his travels. He further noted that his symptoms had improved on day 3 of his illness, but acutely worsened on day 4, which prompted him to visit the ED. The patient’s primary complaint was a severe retro-orbital headache, fever, and one episode of epistaxis.

On physical examination, the patient had conjunctivitis and hepatosplenomegaly, but otherwise appeared well. His laboratory evaluation was significant for leukopenia (white blood cell [WBC] count, 2.40 x 109/L), thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 123 x 109/L), and a positive mononuclear spot test. Both dengue immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) tests sent from the ED were negative. Based on the patient’s thrombocytopenia and epistaxis, as well as concerns that the patient was entering into the critical phase of dengue fever, he was admitted to the inpatient hospital for observation.

The patient’s course improved during his stay with symptomatic treatment and blood-count monitoring, and he was discharged home on hospital day 3. He followed up at our hospital travel clinic the day after discharge; a repeat dengue IgM test taken during this visit came back positive.

Case 2

A 51-year-old man presented to the ED with a 3-day history of intermittent fever and diffuse myalgia. He reported chills, night sweats, and the feeling of abdominal fullness. He denied nausea, vomiting, or changes in the character of his stool. He had no known sick contacts, but reported he had traveled from the Philippines 3 days prior to presentation and that his symptoms had developed en route to the United States. The patient also denied any known tick, mosquito, or animal exposures. He said he had treated his symptoms with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Prior to his arrival at the ED, he had twice presented to a walk-in clinic earlier that day. Repeated laboratory testing at the ED showed a decrease in WBC count from 42.0 x 109/L to 31.0 x 109/L, as well as a declining platelet count from 123 x 109/L to 87 x 109/L. On physical examination, the patient was ill-appearing, diaphoretic, and had a temperature of 100.6°F. His vital signs were otherwise within normal limits.

With the exception of a mild diffuse petechial rash on the patient’s thighs bilaterally, the physical examination was unrevealing. A tourniquet test (TT) to assess capillary fragility was performed at bedside, and yielded a positive result (Figure 1). Work-up further demonstrated a declining WBC of 2.70 x 109/L and declining platelet count of 65 x 109/L.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test confirmed a diagnosis of dengue, with a positive dengue type-4 (DEN-4) serotype detection. Supportive care was initiated, and the patient was admitted to the inpatient hospital for continued treatment. He was discharged home on hospital day 5; however, he returned to the ED later that day with increasing headache and left flank pain. Work-up included axial and coronal computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis, which revealed hematuria and a left upper pole renal infarction surrounded by mild perinephric fat stranding (Figure 2a and 2b) with maintenance of left renal artery/vein patency.

The patient was admitted to an inpatient floor, where symptomatic management was employed. He underwent unrevealing bubble echocardiography and lower extremity Doppler ultrasound imaging, and anticoagulation therapy was initiated per a consultation with hematology services. The patient was discharged home in improved, stable condition on hospital day 8.

Discussion

Dengue virus is a single-stranded, nonsegmented RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. Four major subtypes exist: DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, and DEN-4. Lifelong serotype-specific immunity is conferred following infection. The virus is transmitted by the female Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is found worldwide but has a predilection for tropical and subtropical regions. The Aedes aegypti mosquito remains an effective vector secondary to its diurnal feeding habit and nearly imperceptible bite.1,3

The viral incubation period for dengue is typically 3 to 7 days4; therefore, dengue is highly unlikely in patients whose symptoms begin more than 2 weeks after departure from an endemic area. Replication primarily occurs in the regional lymph nodes and disseminates through the lymphatic system and bloodstream.1

The 1997 WHO guidelines previously classified dengue into three categories: undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever (which was further classified by four severity grades, with grades III and IV defined as dengue shock syndrome). However, changes in epidemiology of the disease and reports of difficulty applying the criteria in the clinical setting led to reclassification of dengue on a continuum from dengue to severe dengue in the WHO’s updated 2009 guidelines.4

Signs and Symptoms

The ramifications of dengue infection can range from asymptomatic (typically in young, immunocompetent patients) to lethal. Key symptoms of dengue fever include nausea, vomiting, fever, respiratory symptoms, morbilliform or maculopapular rash, and headache or retro-orbital pain. In addition, arthralgia (hence the colloquial name for dengue of “breakbone fever”), myalgia, and conjunctivitis may exist.3,4 Fever usually lasts 5 to 7 days and can be biphasic, with a return of symptoms after the initial resolution as seen in case report 1.4 Severe dengue is characterized by capillary leakage, hemorrhage, or end-organ damage.3-5 The most common bleeding sites are the skin, nose, and gums.

Diagnosis

Bedside evaluation for dengue can be performed with the TT—one of the WHO’s case definitions for dengue.6 This is accomplished by placing a manual blood pressure (BP) cuff on the arm and inflating it to halfway between systolic and diastolic BP for 5 minutes. The test is positive for dengue if more than 10 petechiae appear per 1-inch (2.5-cm) square below the antecubital fossa.7 Of note, the test has poor sensitivity (51.6%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 33-69), but good specificity (82.4%, 95% CI, 76-87).7,8 A positive TT combined with leukopenia increases the sensitivity to 93.9%, [95% CI, 89-96].7 While not specific to dengue infection, in the right clinical scenario, the TT is a simple bedside test to help confirm the diagnosis and is extremely useful in resource-limited settings.

During the initial days of illness, the virus may be detected by PCR, as viremia and fever usually correlate. Once defervescence occurs, IgM and then IgG antibodies become detectable. When using these antibody tests to evaluate for dengue, clinicians should be aware of cross-reactivity with other flavivirus infections, such as yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis (including immunological cross-reactivity).1 New diagnostic modalities include enzyme immunoassays that can detect dengue viral RNA within 24 to 48 hours, and viral antigen-detection kits, which can yield results in less than 1 hour.4

Aside from advanced laboratory testing, worsening thrombocytopenia in light of a rising hematocrit can be highly suggestive of dengue. Leukopenia with lymphopenia and mild elevation of hepatic enzymes (typically 2 to 5 times the upper limits of the normal reference range) are also often seen in active infections.1 The occurrence of these signs in conjunction with a rapid reduction in the platelets often signals transition to the critical phase of plasma leakage.1,4

Treatment

Treatment of dengue consists of supportive care and transfusion when necessary. The WHO recommends strict observation of patients with suspected dengue who have warning signs of severe disease (eg, abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, hepatomegaly, rapid increase in hematocrit with concomitant drop in platelet count). Inpatient treatment centers on judicious fluid management, trending blood count parameters, and monitoring for signs of plasma leakage and hemorrhage. Fluid resuscitation is titrated to optimize central and peripheral circulation and end-organ perfusion. Blood-product administration should be reserved for suspected or severe bleeding.4

While dengue fever was the final diagnosis in both of our case presentations, these cases also highlight key diagnostic and treatment dilemmas associated with dengue. The patient in the first case report demonstrated the characteristic biphasic fever seen with dengue—resolution of symptoms on day 3, but then return of fever and symptoms on day 4. Often the dengue-specific antibodies are not formed until after the resolution of fever. This patient represents a classic example of dengue as the serologic studies sent on day 4 of the patient’s illness were negative but then turned positive on day 7, illustrating the need for high clinical suspicion and underscoring the importance of initiating treatment despite laboratory confirmation.

Further, regarding the patient in the second case, though proteinuria, hematuria, acute renal failure, and glomerulonephritis are previously described renal complications of dengue,9 a thorough literature search yielded no prior published accounts of renal infarction. Given the patient’s previous healthy status and the lack of other hypothesis as to the mechanism of injury, we suspect this patient’s renal infarction was due to the transient hypercoagulability characteristic of dengue and responsible for other clinical manifestations of the disease.

Conclusion

In addition to more prevalent illnesses such as malaria, acute traveler’s diarrhea, and respiratory tract infections, dengue fever should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating a febrile patient who has a history of recent travel to countries where dengue is endemic. A high clinical suspicion, combined with a thorough history and physical examination, is essential to making the diagnosis.