User login

The paranoid business executive

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

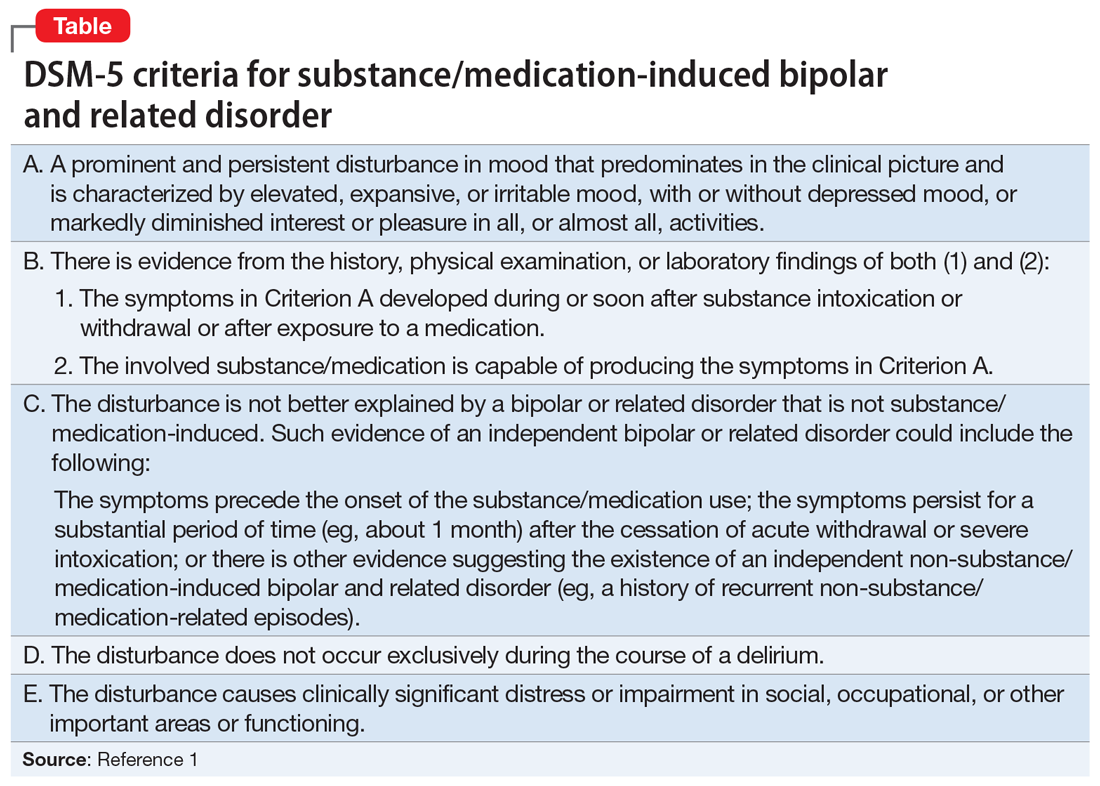

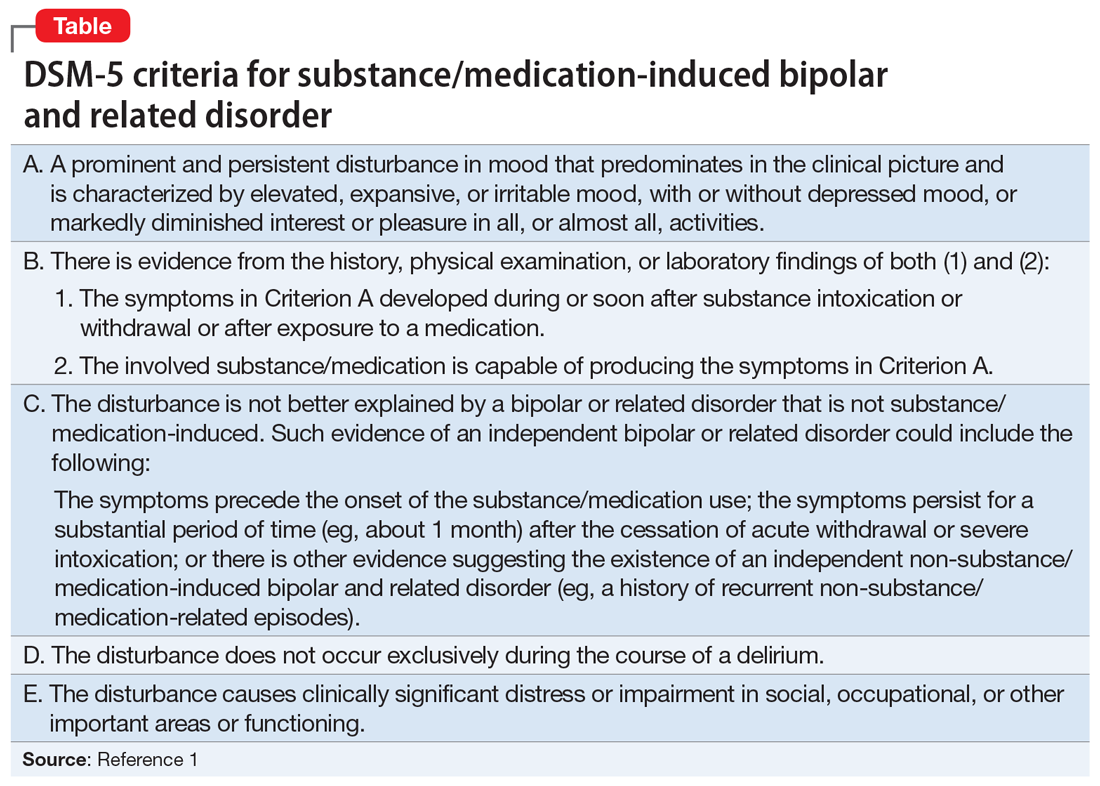

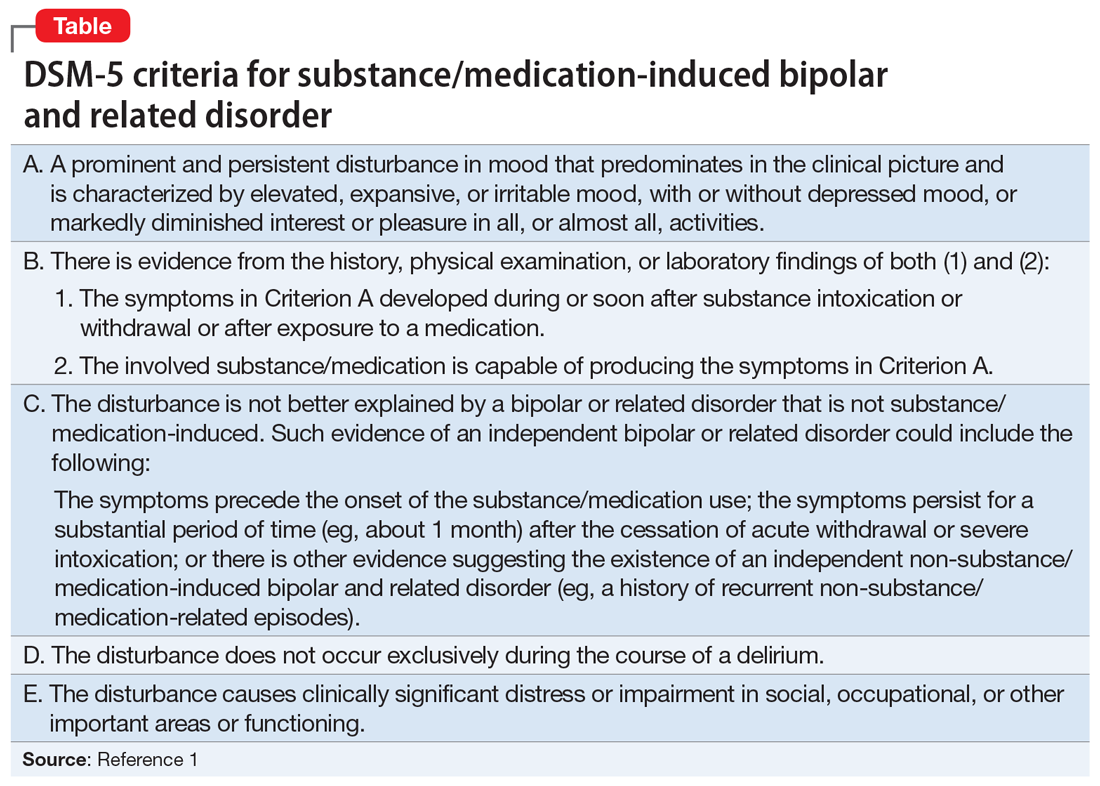

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

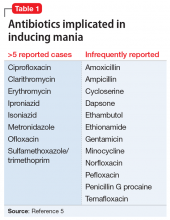

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

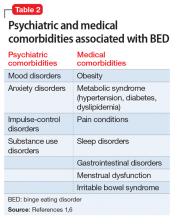

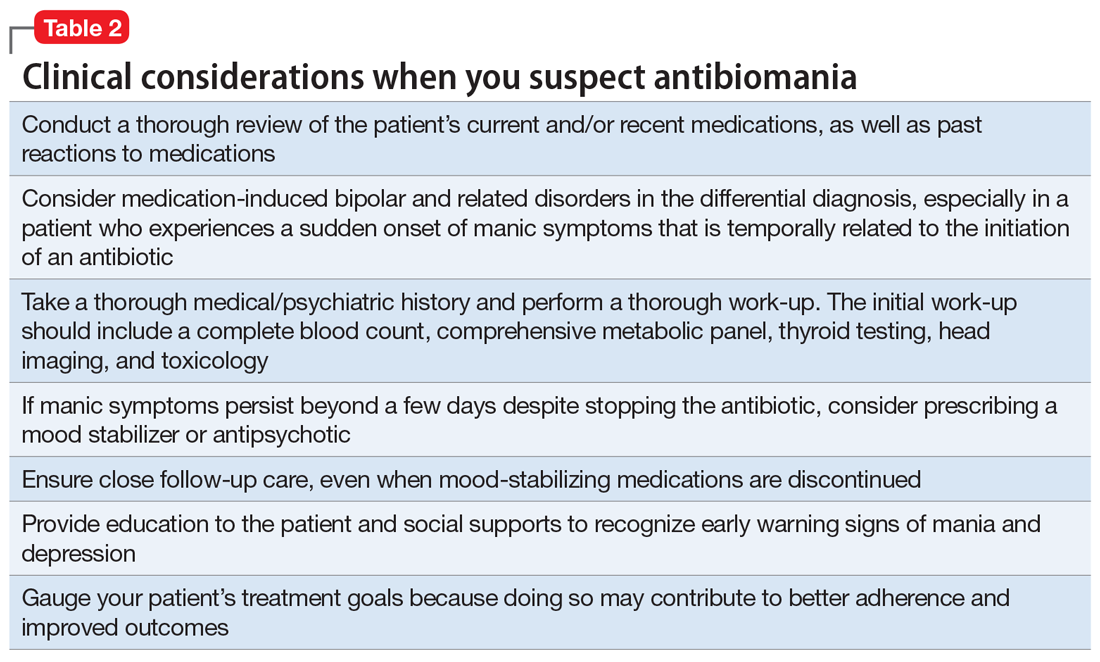

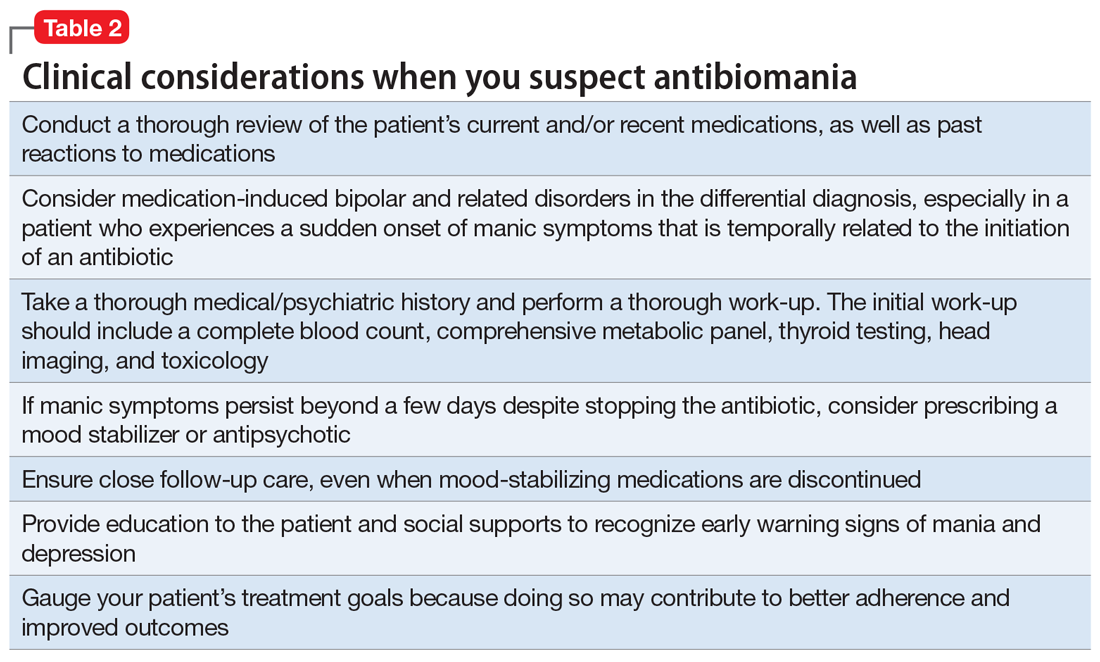

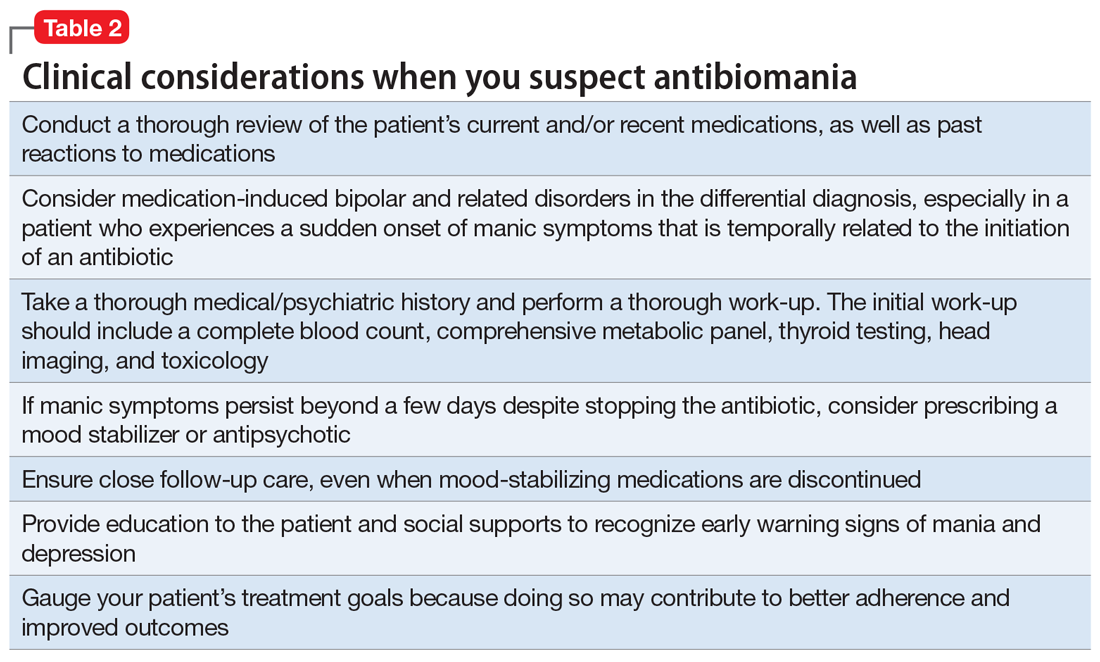

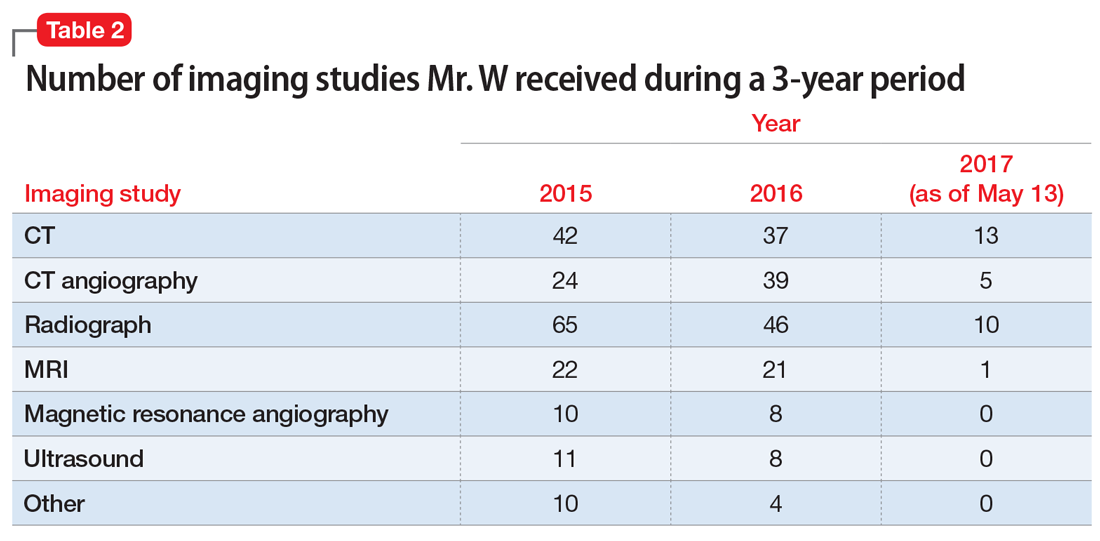

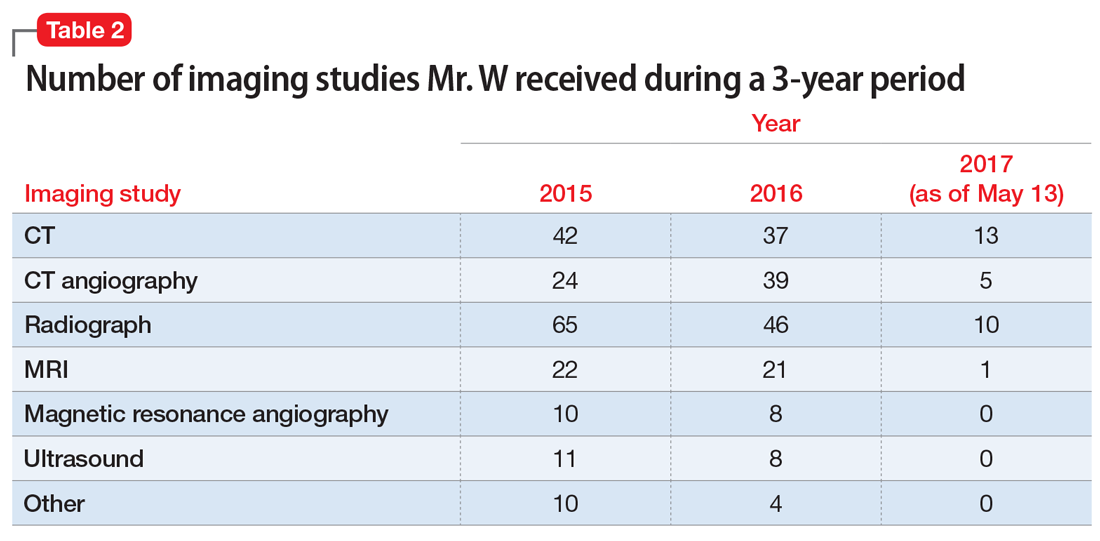

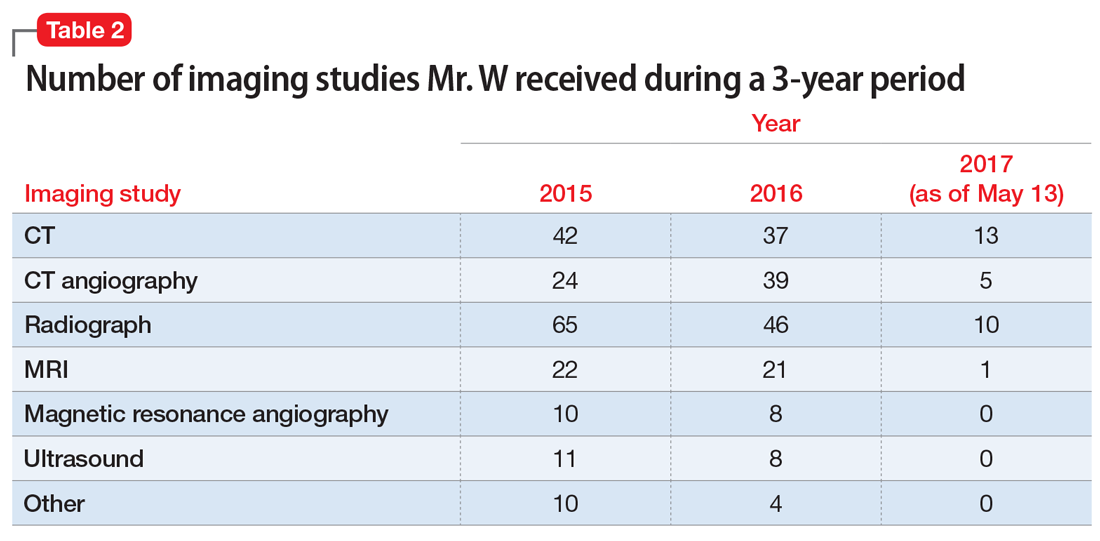

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

Seeing snakes that aren’t there

CASE Disruptive and inattentive

R, age 9, is brought by his mother to our child/adolescent psychiatry clinic, where he has been receiving treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), because he is experiencing visual hallucinations and exhibiting aggressive behavior. R had initially been prescribed (and had been taking) short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg every morning for weeks. During this time, he responded well to the medication; he had reduced hyperactivity, talked less in class, and was able to give increased attention to his academic work. After 2 weeks, because R did not want to take short-acting methylphenidate in school, we switched him to osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) methylphenidate, 18 mg every morning.

Two days after starting the OROS methylphenidate formulation, R develops visual hallucinations and aggressive behavior. His visual hallucinations—which occur both at home and at school—involve seeing snakes circling him. When hallucinating, he hits and pushes family members and throws objects at them. He refuses to go to school because he fears the snakes. The hallucinations continue throughout the day and persist for the next 3 to 4 days.

R does not have any comorbid medical or psychiatric illnesses; however, his father has a history of schizophrenia, polysubstance abuse, and multiple prior psychiatric hospitalizations due to medication noncompliance.

R undergoes laboratory workup, which includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and urine drug screening. All results are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10468215]

The authors’ observations

We ruled out delirium by ordering a basic laboratory workup. We considered the possibility of a new mood or psychotic disorder, but began to suspect the OROS methylphenidate might be causing R’s symptoms.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is an increasingly prevalent diagnosis in the United States, affecting up to 6.4 million children age 4 to 17. While symptoms of ADHD often first appear in preschool-age children, the average age at which a child receives a diagnosis of ADHD is 7.

Stimulants are a clinically effective treatment for ADHD. In general, their use is safe and well tolerated, especially in pediatric patients. Some common adverse effects of stimulant medications include reduced appetite, headache, and insomnia.1 Psychotic symptoms such as paranoid delusions, visual hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, and tactile hallucinations are rare. In some cases, these psychotic symptoms can be accompanied by increased aggression.2-4

Continue to: Methylphenidate is one of the most...

Methylphenidate is one of the most commonly prescribed stimulants for treating ADHD. Methylphenidate has 2 known mechanisms of action: 1) inhibition of catecholamine reuptake at the presynaptic dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and 2) binding to and blocking intracellular dopamine transporters, inhibiting both dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake.5,6 Because increased levels of synaptic dopamine are implicated in the generation of psychotic symptoms, the pharmacologic mechanism of methylphenidate also implies a potential to induce psychotic symptoms.7

How common is this problem?

On the population level, there is no detectable difference in the event rate (incidence) of psychosis in children treated with stimulants or children not taking stimulants.8 However, there are reports that individual patients can experience psychosis due to treatment with stimulants as an unusual adverse medication reaction. In 1971, Lucas and Weiss9 were among the first to describe 3 cases of methylphenidate-induced psychosis. Since then, many articles in the scientific literature have reported cases of psychosis related to stimulant medications.

A brief review of the literature between 2002 and 2010 revealed 14 cases of stimulant-related psychosis, in patients ranging from age 7 to 45. Six of the patients were children, age 7 to 12; 1 patient was an adolescent, age 15; 4 were young adults, age 18 to 25; and 3 were older adults. Of all 14 individuals, 7 reported visual hallucinations, 4 had tactile hallucinations, 4 had auditory hallucinations, and 3 displayed paranoid delusions.10 With the aim of exploring possible etiologic factors associated with psychotic symptoms, such as type of drug and dosage, it was found that 9 patients received methylphenidate, with total daily doses ranging from 7.5 to 74 mg (3 patients received short-acting methylphenidate; 1 patient received methylphenidate extended release (ER); 1 patient received both; 4 patients received dextroamphetamine, with doses of 30 to 50 mg/d; and 1 patient received amphetamine, 10 mg/d). In terms of family history, 1 patient had a positive family history of schizophrenia; 1 patient had a family history of bipolar disorder; and 6 patients were negative for family history of any psychotic disorder.10

In 2006, due to growing concerns about adverse psychiatric effects of ADHD medications, the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology requested the electronic clinical trial databases of manufacturers of drugs approved for the treatment of ADHD, or those with active clinical development programs for the same indication.11 In that study, Mosholder et al11 analyzed data from 49 randomized, controlled clinical trials that were in pediatric development programs and found that there were psychotic or manic adverse events in 11 individuals in the pooled active drug group. These were observed with methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, and atomoxetine. There were no events in the placebo group, which reinforced the causality between the ADHD medication and these symptoms, as participants with untreated ADHD did not develop them.11

It is important to note that ADHD medications taken in excessive doses are much more likely to provoke psychotic adverse effects than when taken at therapeutic doses. However, as seen in our clinical case, patients such as R could develop acute psychosis even with a lower dosage of stimulant medications. An article by Ross2 suggested rates of .25% for this psychiatric adverse effect (1 in 400 children treated with therapeutic doses of stimulants will develop psychosis), which is consistent with the data from the Mosholder et al11 study.

Continue to: TREATMENT Discontinuation and re-challenge

TREATMENT Discontinuation and re-challenge

After 3 days, we discontinue OROS methylphenidate. Five days after discontinuation, R’s visual hallucinations and aggressive behaviors completely resolve. After not receiving stimulants for 2 weeks, R is restarted on short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg/d, because he had a relatively good clinical response to short-acting methylphenidate previously. After 14 days, the short-acting methylphenidate dosage is increased to 5 mg twice daily without the re-emergence of psychosis or aggressive behaviors.

The authors’ observations

Although stimulant-induced psychosis can be a disturbing adverse effect, severe ADHD greatly affects a person’s functioning at school and at home and can lead to several comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. For these reasons, most patients with ADHD who experience psychotic symptoms are re-challenged with stimulants.10 Out of the 14 cases discussed above, 4 patients were restarted on the same stimulant or a different ADHD medication; 2 of them had the same psychotic symptoms days after the reintroduction of the drug and the other 2 had no recurrence.10,12,13

Stimulant-induced hallucinations

The emergence of hallucinations with methylphenidate or amphetamines has been attributed to a chronic increase of dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft, while the pathophysiological mechanisms are not clearly known. In some cases, hallucinations emerged after taking the first low dose, which has been thought to be an effect of idiosyncratic mechanism. Stimulants cause an increase of the releasing of catecholamines. Porfirio et al14 argue that high-dose stimulants can deteriorate the response to visual stimuli, causing a different perception of visual stimuli in susceptible children, based on the information that norepinephrine is released in the lateral geniculate nucleus, and it increases the transmission of visual information.

An idiosyncratic drug reaction

Despite the existence of many theories on the pathophysiology of stimulant-induced psychosis (Box15-18), its actual mechanism remains unknown. In R’s case, given the speed with which his symptoms developed, the proposed mechanisms of action may not explain his psychotic symptoms. We must consider an idiosyncratic drug reaction as an explanation. This suggestion is supported by the fact that re-challenging with a stimulant did not re-induce psychosis in 2 out of the 4 cases described in the literature,10,12,13 as well as in R’s case.

Box

Although the subjective effects of methylphenidate and amphetamines are similar, neurochemical effects of the 2 stimulants are distinct, with different mechanisms of action. Methylphenidate targets the dopamine transporter (DAT) and the noradrenaline transporter (NET), inhibiting DA and NA reuptake, and therefore increasing DA and NA levels in the synaptic cleft. Amphetamine targets DAT and NET, inhibiting DA and NA reuptake, and therefore increasing DA and NA levels in the synaptic cleft. It also enters the presynaptic neuron, preventing DA/NA from storing in the vesicles. In addition, it promotes the release of catecholamines from vesicles into the cytosol and ultimately from the cytosol into the synaptic cleft.18

Generally, amphetamines are twice as potent as methylphenidate. As such, lower doses of amphetamine preparations can cause psychotic symptoms when compared with methamphetamine products.17 Griffith15 showed that paranoia manifested itself in all participants who were previously healthy as they underwent repeated administration of 5 to 15 mg of oral dextroamphetamine many times per day for up to 5 days in a row, leading to cumulative doses ranging from 200 to 800 mg.15 At such doses, the effects are similar to those obtained with illicit use of methamphetamine, a drug of abuse for which psychosis-inducing effects are well documented.

Psychosis in reaction to therapeutic doses of methylphenidate may have a mechanism of action that is shared by psychosis in response to chronic use of methamphetamine. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain the mechanism behind stimulantinduced psychosis in cases of chronic methamphetamine use:

- Young,16 who had one of the first proposed theories in 1981, hypothesized attributing symptoms to dose-related effects at pre- and post-synaptic noradrenergic and dopaminergic receptors.

- Hsieh et al18 hypothesized that methamphetamine use causes an increased flow of dopamine in the striatum, which leads to excessive glutamate release into the cortex. Excess glutamate in the cortex might, over time, cause damage to cortical interneurons. This damage may dysregulate thalamocortical signals, resulting in psychotic symptoms.18

Although the mechanisms by which psychotic symptoms associated with stimulants occur remain unknown, possibilities include10,19:

- genetic predisposition

- changes induced by stimulants at the level of neurotransmitters, synapses, and brain circuits

- an idiosyncratic drug reaction.

Continue to: What to consider before prescribing stimulants

What to consider before prescribing stimulants

While stimulants are clearly beneficial for the vast majority of children with ADHD, there may be a small subgroup of patients for whom stimulants carry increased risk. For example, it is possible that patients with a family history of mood and psychotic disorders may be more vulnerable to stimulant-induced psychotic symptoms that are reversible on discontinuation.20 In our case, R had a first-degree relative (his father) with treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Attentional dysfunction is a common premorbid presentation for children who later develop schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Retrospective data from patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder document high rates of childhood stimulant use—generally higher even than other groups with attentional dysfunction21 and histories of stimulant-associated adverse behavioral effects.22 In these patients, a history of stimulant use is also associated with an earlier age at onset23 and a more severe course of illness during hospitalization.24 Stimulant exposure in vulnerable individuals may hasten the onset or worsen the course of bipolar or psychotic illnesses.21,25,26

OUTCOME Well-controlled symptoms

R continues to receive short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg twice a day. His ADHD symptoms remain well-controlled, and he is able to do well academically.

The authors’ observations

Although stimulant-induced psychosis is a rare and unpredictable occurrence, carefully monitoring all patients for any adverse effects of ADHD medication is recommended. When present, psychotic symptoms may quickly remit upon discontinuation of the medication. The question of subsequently reintroducing stimulant medication for a patient with severe ADHD is complicated. One needs to measure the possible risk of a reoccurrence of the psychotic symptoms against the consequences of untreated ADHD. These consequences include increased risk for academic and occupational failure, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Psychosocial interventions for ADHD should be implemented, but for optimal results, they often need to be combined with medication. However, if a stimulant medication is to be reintroduced, this should be done with extreme care. Starting dosages need to be low, and increases should be gradual, with frequent monitoring.

Bottom Line

Although stimulant-induced psychosis is a rare occurrence, determine if your pediatric patient with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has a family history of mood or psychotic disorders before initiating stimulants. Carefully monitor all patients for any adverse effects of stimulant medications prescribed for ADHD. If psychotic symptoms occur at therapeutic doses, reduce the dose or discontinue the medication. Once the psychotic or manic symptoms resolve, it may be appropriate to re-challenge with a stimulant.

Related Resource

- Man KK, Coghill D, Chan EW, et al. Methylphenidate and the risk of psychotic disorders and hallucinations in children and adolescents in a large health system. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(11):e956. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.216.

Drug Brand Names

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Methylphenidate • Metadate, Ritalin

Methylphenidate ER • Concerta

1. Cherland E, Fitzpatrick R. Psychotic side effects of psychostimulants: a 5-year review. Can J Psychiatry. 1999; 44(8):811-813.

2. Ross RG. Psychotic and manic-like symptoms during stimulant treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1149-1152.

3. Rashid J, Mitelman S. Methylphenidate and somatic hallucinations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):945-946.

4. Rubio JM, Sanjuán J, Flórez-Salamanca L, et al. Examining the course of hallucinatory experiences in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2-3):248-254.

5. Iversen L. Neurotransmitter transporters and their impact on the development of psychopharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S82-S88.

6. Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):776-786.

7. Bloom AS, Russell LJ, Weisskopf B, et al. Methylphenidate-induced delusional disorder in a child with attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(1):88-89.

8. Shibib S, Chaloub N. Stimulant induced psychosis. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2009;14(1):1420-1423.

9. Lucas AR, Weiss M. Methylphenidate hallucinosis. JAMA. 1971;217(8):1079-1081.

10. Kraemer M, Uekermann J, Wiltfang J, et al. Methylphenidate-induced psychosis in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: report of 3 new cases and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(4):204-206.

11. Mosholder AD, Gelperin K, Hammad TA, et al. Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2009; 123:611-616.

12. Gross-Tsur V, Joseph A, Shalev RS. Hallucinations during methylphenidate therapy. Neurology. 2004;63(4):753-754.

13. Halevy A, Shuper A. Methylphenidate induction of complex visual hallucinations. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(8):1005-1007.

14. Porfirio MC, Giana G, Giovinazzo S, et al. Methylphenidate-induced visual hallucinations. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42(1):30-31.

15. Griffith J. A study of illicit amphetamine drug traffic in Oklahoma City. Am J Psychiatry. 1966;123(5):560-569.

16. Young JG. Methylphenidate-induced hallucinosis: case histories and possible mechanisms of action. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1981;2(2):35-38.

17. Stein MA, Sarampote CS, Waldman ID, et al. A dose-response study of OROS methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2003; 112(5):e404. PMID: 14595084.

18. Hsieh JH, Stein DJ, Howells FM. The neurobiology of methamphetamine induced psychosis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:537. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00537.

19. Shyu YC, Yuan SS, Lee SY, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, methylphenidate use and the risk of developing schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Schizophrenia Res. 2015;168(1-2):161-167.

20. MacKenzie LE, Abidi S, Fisher HL, et al. Stimulant medication and psychotic symptoms in offspring of parents with mental illness. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2486.

21. Schaeffer J, Ross RG. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: premorbid and prodromal diagnosis and treatment histories. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):538-545.

22. Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Blovinsky IP, et al. Treatment-emergent mania in pediatric bipolar disorder: a retrospective case review. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(1):149-158.

23. DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, et al. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(2):53-57.

24. Soutullo CA, DelBello MP, Ochsner BS, et al. Severity of bipolarity in hospitalized manic adolescents with history of stimulant or antidepressant treatment. J Affect Disord. 2002;70(3):323-327.

25. Reichart CG, Nolen WA. Earlier onset of bipolar disorder in children by antidepressants or stimulants? An hypothesis. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(1):81-84.

26. Ikeda M, Okahisa Y, Aleksic B, et al. Evidence for shared genetic risk between methamphetamine-induced psychosis and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(10):1864-1870.

CASE Disruptive and inattentive

R, age 9, is brought by his mother to our child/adolescent psychiatry clinic, where he has been receiving treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), because he is experiencing visual hallucinations and exhibiting aggressive behavior. R had initially been prescribed (and had been taking) short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg every morning for weeks. During this time, he responded well to the medication; he had reduced hyperactivity, talked less in class, and was able to give increased attention to his academic work. After 2 weeks, because R did not want to take short-acting methylphenidate in school, we switched him to osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) methylphenidate, 18 mg every morning.

Two days after starting the OROS methylphenidate formulation, R develops visual hallucinations and aggressive behavior. His visual hallucinations—which occur both at home and at school—involve seeing snakes circling him. When hallucinating, he hits and pushes family members and throws objects at them. He refuses to go to school because he fears the snakes. The hallucinations continue throughout the day and persist for the next 3 to 4 days.

R does not have any comorbid medical or psychiatric illnesses; however, his father has a history of schizophrenia, polysubstance abuse, and multiple prior psychiatric hospitalizations due to medication noncompliance.

R undergoes laboratory workup, which includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and urine drug screening. All results are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10468215]

The authors’ observations

We ruled out delirium by ordering a basic laboratory workup. We considered the possibility of a new mood or psychotic disorder, but began to suspect the OROS methylphenidate might be causing R’s symptoms.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is an increasingly prevalent diagnosis in the United States, affecting up to 6.4 million children age 4 to 17. While symptoms of ADHD often first appear in preschool-age children, the average age at which a child receives a diagnosis of ADHD is 7.

Stimulants are a clinically effective treatment for ADHD. In general, their use is safe and well tolerated, especially in pediatric patients. Some common adverse effects of stimulant medications include reduced appetite, headache, and insomnia.1 Psychotic symptoms such as paranoid delusions, visual hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, and tactile hallucinations are rare. In some cases, these psychotic symptoms can be accompanied by increased aggression.2-4

Continue to: Methylphenidate is one of the most...

Methylphenidate is one of the most commonly prescribed stimulants for treating ADHD. Methylphenidate has 2 known mechanisms of action: 1) inhibition of catecholamine reuptake at the presynaptic dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and 2) binding to and blocking intracellular dopamine transporters, inhibiting both dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake.5,6 Because increased levels of synaptic dopamine are implicated in the generation of psychotic symptoms, the pharmacologic mechanism of methylphenidate also implies a potential to induce psychotic symptoms.7

How common is this problem?

On the population level, there is no detectable difference in the event rate (incidence) of psychosis in children treated with stimulants or children not taking stimulants.8 However, there are reports that individual patients can experience psychosis due to treatment with stimulants as an unusual adverse medication reaction. In 1971, Lucas and Weiss9 were among the first to describe 3 cases of methylphenidate-induced psychosis. Since then, many articles in the scientific literature have reported cases of psychosis related to stimulant medications.

A brief review of the literature between 2002 and 2010 revealed 14 cases of stimulant-related psychosis, in patients ranging from age 7 to 45. Six of the patients were children, age 7 to 12; 1 patient was an adolescent, age 15; 4 were young adults, age 18 to 25; and 3 were older adults. Of all 14 individuals, 7 reported visual hallucinations, 4 had tactile hallucinations, 4 had auditory hallucinations, and 3 displayed paranoid delusions.10 With the aim of exploring possible etiologic factors associated with psychotic symptoms, such as type of drug and dosage, it was found that 9 patients received methylphenidate, with total daily doses ranging from 7.5 to 74 mg (3 patients received short-acting methylphenidate; 1 patient received methylphenidate extended release (ER); 1 patient received both; 4 patients received dextroamphetamine, with doses of 30 to 50 mg/d; and 1 patient received amphetamine, 10 mg/d). In terms of family history, 1 patient had a positive family history of schizophrenia; 1 patient had a family history of bipolar disorder; and 6 patients were negative for family history of any psychotic disorder.10

In 2006, due to growing concerns about adverse psychiatric effects of ADHD medications, the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology requested the electronic clinical trial databases of manufacturers of drugs approved for the treatment of ADHD, or those with active clinical development programs for the same indication.11 In that study, Mosholder et al11 analyzed data from 49 randomized, controlled clinical trials that were in pediatric development programs and found that there were psychotic or manic adverse events in 11 individuals in the pooled active drug group. These were observed with methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, and atomoxetine. There were no events in the placebo group, which reinforced the causality between the ADHD medication and these symptoms, as participants with untreated ADHD did not develop them.11

It is important to note that ADHD medications taken in excessive doses are much more likely to provoke psychotic adverse effects than when taken at therapeutic doses. However, as seen in our clinical case, patients such as R could develop acute psychosis even with a lower dosage of stimulant medications. An article by Ross2 suggested rates of .25% for this psychiatric adverse effect (1 in 400 children treated with therapeutic doses of stimulants will develop psychosis), which is consistent with the data from the Mosholder et al11 study.

Continue to: TREATMENT Discontinuation and re-challenge

TREATMENT Discontinuation and re-challenge

After 3 days, we discontinue OROS methylphenidate. Five days after discontinuation, R’s visual hallucinations and aggressive behaviors completely resolve. After not receiving stimulants for 2 weeks, R is restarted on short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg/d, because he had a relatively good clinical response to short-acting methylphenidate previously. After 14 days, the short-acting methylphenidate dosage is increased to 5 mg twice daily without the re-emergence of psychosis or aggressive behaviors.

The authors’ observations

Although stimulant-induced psychosis can be a disturbing adverse effect, severe ADHD greatly affects a person’s functioning at school and at home and can lead to several comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. For these reasons, most patients with ADHD who experience psychotic symptoms are re-challenged with stimulants.10 Out of the 14 cases discussed above, 4 patients were restarted on the same stimulant or a different ADHD medication; 2 of them had the same psychotic symptoms days after the reintroduction of the drug and the other 2 had no recurrence.10,12,13

Stimulant-induced hallucinations

The emergence of hallucinations with methylphenidate or amphetamines has been attributed to a chronic increase of dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft, while the pathophysiological mechanisms are not clearly known. In some cases, hallucinations emerged after taking the first low dose, which has been thought to be an effect of idiosyncratic mechanism. Stimulants cause an increase of the releasing of catecholamines. Porfirio et al14 argue that high-dose stimulants can deteriorate the response to visual stimuli, causing a different perception of visual stimuli in susceptible children, based on the information that norepinephrine is released in the lateral geniculate nucleus, and it increases the transmission of visual information.

An idiosyncratic drug reaction

Despite the existence of many theories on the pathophysiology of stimulant-induced psychosis (Box15-18), its actual mechanism remains unknown. In R’s case, given the speed with which his symptoms developed, the proposed mechanisms of action may not explain his psychotic symptoms. We must consider an idiosyncratic drug reaction as an explanation. This suggestion is supported by the fact that re-challenging with a stimulant did not re-induce psychosis in 2 out of the 4 cases described in the literature,10,12,13 as well as in R’s case.

Box

Although the subjective effects of methylphenidate and amphetamines are similar, neurochemical effects of the 2 stimulants are distinct, with different mechanisms of action. Methylphenidate targets the dopamine transporter (DAT) and the noradrenaline transporter (NET), inhibiting DA and NA reuptake, and therefore increasing DA and NA levels in the synaptic cleft. Amphetamine targets DAT and NET, inhibiting DA and NA reuptake, and therefore increasing DA and NA levels in the synaptic cleft. It also enters the presynaptic neuron, preventing DA/NA from storing in the vesicles. In addition, it promotes the release of catecholamines from vesicles into the cytosol and ultimately from the cytosol into the synaptic cleft.18

Generally, amphetamines are twice as potent as methylphenidate. As such, lower doses of amphetamine preparations can cause psychotic symptoms when compared with methamphetamine products.17 Griffith15 showed that paranoia manifested itself in all participants who were previously healthy as they underwent repeated administration of 5 to 15 mg of oral dextroamphetamine many times per day for up to 5 days in a row, leading to cumulative doses ranging from 200 to 800 mg.15 At such doses, the effects are similar to those obtained with illicit use of methamphetamine, a drug of abuse for which psychosis-inducing effects are well documented.

Psychosis in reaction to therapeutic doses of methylphenidate may have a mechanism of action that is shared by psychosis in response to chronic use of methamphetamine. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain the mechanism behind stimulantinduced psychosis in cases of chronic methamphetamine use:

- Young,16 who had one of the first proposed theories in 1981, hypothesized attributing symptoms to dose-related effects at pre- and post-synaptic noradrenergic and dopaminergic receptors.

- Hsieh et al18 hypothesized that methamphetamine use causes an increased flow of dopamine in the striatum, which leads to excessive glutamate release into the cortex. Excess glutamate in the cortex might, over time, cause damage to cortical interneurons. This damage may dysregulate thalamocortical signals, resulting in psychotic symptoms.18

Although the mechanisms by which psychotic symptoms associated with stimulants occur remain unknown, possibilities include10,19:

- genetic predisposition

- changes induced by stimulants at the level of neurotransmitters, synapses, and brain circuits

- an idiosyncratic drug reaction.

Continue to: What to consider before prescribing stimulants

What to consider before prescribing stimulants

While stimulants are clearly beneficial for the vast majority of children with ADHD, there may be a small subgroup of patients for whom stimulants carry increased risk. For example, it is possible that patients with a family history of mood and psychotic disorders may be more vulnerable to stimulant-induced psychotic symptoms that are reversible on discontinuation.20 In our case, R had a first-degree relative (his father) with treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Attentional dysfunction is a common premorbid presentation for children who later develop schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Retrospective data from patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder document high rates of childhood stimulant use—generally higher even than other groups with attentional dysfunction21 and histories of stimulant-associated adverse behavioral effects.22 In these patients, a history of stimulant use is also associated with an earlier age at onset23 and a more severe course of illness during hospitalization.24 Stimulant exposure in vulnerable individuals may hasten the onset or worsen the course of bipolar or psychotic illnesses.21,25,26

OUTCOME Well-controlled symptoms

R continues to receive short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg twice a day. His ADHD symptoms remain well-controlled, and he is able to do well academically.

The authors’ observations

Although stimulant-induced psychosis is a rare and unpredictable occurrence, carefully monitoring all patients for any adverse effects of ADHD medication is recommended. When present, psychotic symptoms may quickly remit upon discontinuation of the medication. The question of subsequently reintroducing stimulant medication for a patient with severe ADHD is complicated. One needs to measure the possible risk of a reoccurrence of the psychotic symptoms against the consequences of untreated ADHD. These consequences include increased risk for academic and occupational failure, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Psychosocial interventions for ADHD should be implemented, but for optimal results, they often need to be combined with medication. However, if a stimulant medication is to be reintroduced, this should be done with extreme care. Starting dosages need to be low, and increases should be gradual, with frequent monitoring.

Bottom Line

Although stimulant-induced psychosis is a rare occurrence, determine if your pediatric patient with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has a family history of mood or psychotic disorders before initiating stimulants. Carefully monitor all patients for any adverse effects of stimulant medications prescribed for ADHD. If psychotic symptoms occur at therapeutic doses, reduce the dose or discontinue the medication. Once the psychotic or manic symptoms resolve, it may be appropriate to re-challenge with a stimulant.

Related Resource

- Man KK, Coghill D, Chan EW, et al. Methylphenidate and the risk of psychotic disorders and hallucinations in children and adolescents in a large health system. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(11):e956. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.216.

Drug Brand Names

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Methylphenidate • Metadate, Ritalin

Methylphenidate ER • Concerta

CASE Disruptive and inattentive

R, age 9, is brought by his mother to our child/adolescent psychiatry clinic, where he has been receiving treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), because he is experiencing visual hallucinations and exhibiting aggressive behavior. R had initially been prescribed (and had been taking) short-acting methylphenidate, 5 mg every morning for weeks. During this time, he responded well to the medication; he had reduced hyperactivity, talked less in class, and was able to give increased attention to his academic work. After 2 weeks, because R did not want to take short-acting methylphenidate in school, we switched him to osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) methylphenidate, 18 mg every morning.