User login

Managing risk—to mother and fetuses—in a twin gestation

Multiple gestations are far more common today than they once were—up 70% since 1980.1 Today, every 1,000 live births include 32.3 sets of twins, a 2% increase in the rate of twin births since 2004. Why this phenomenon is occurring is not entirely understood but, certainly, the trend toward older maternal age and the emergence of assisted reproduction are both part of the explanation.

Multiple gestations are of particular concern to obstetricians because, even though they remain relatively rare, they are responsible for a significant percentage of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The difficulties that twins encounter are often associated with preterm birth and occur most often in identical twins developing within a single gestational sac. Those difficulties include malformation, chromosomal abnormalities, learning disability, behavioral problems, chronic lung disease, neuromuscular developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth. Women pregnant with twins are also at heightened risk, particularly of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes.2

Your task is to manage these risks so that the outlook for mother and infant is as favorable as possible.

Determining chorionicity in the first trimester

Ultrasonographic determination of chorionicity should be the first step in the management of a twin gestation. The determination should be made as early as possible in the pregnancy because it has an immediate impact on counseling, risk of miscarriage, and efficacy of noninvasive screening. (See “Is there 1 sac, or more? Key to predicting risk.”)

The accuracy of ultrasonography (US) in determining chorionicity depends on gestational age. US predictors of dichorionicity include:

- gender discordance

- separate placentas

- the so-called twin-peak sign (also called the lambda sign) (FIGURE 1), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs; compare this with FIGURE 2, showing monochorionic twins with the absence of an intervening placenta

- an intertwin membrane thicker than 1.5 mm to 2.0 mm.

US examination can accurately identify chorionicity at 10 to 14 weeks’ gestation, with overall sensitivity that is reported to be as high as 100%.3-5

FIGURE 1

The twin-peak sign on US

This dichorionic–diamnionic twin gestation demonstrates the so-called twin peak, or lambda, sign (arrow), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs.

FIGURE 2

Monochorionic–diamnionic twin gestation

This US scan of a monochorionic twin gestation reveals the absence of an intervening placenta

Monochorionic twins

Twins who share a gestational sac are more likely than 2-sac twins to suffer spontaneous loss, congenital anomalies, growth restriction and discordancy, preterm delivery, and neurologic morbidity.

Spontaneous loss. In 1 comparative series, the risk of pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks’ gestation was 12.2% for monochorionic twins, compared with 1.8% for dichorionic twins.6 Spontaneously conceived monochorionic twins may have the highest risk of loss.7 However, monochorionic twins occur more often in conceptions achieved by assisted reproductive technology—at a rate 3 to 10 times higher than the background rate of monochorionic twinning.8

- A multiple gestation involves a higher level of risk than a singleton pregnancy

- Chorionicity is the basis for determining risk. Twins within a single sac (monochorionic) are at higher risk of malformation, Down syndrome, and premature birth

- The risk of Down syndrome can be estimated by noninvasive screening in the first trimester and by chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis later in the pregnancy

- A detailed anatomic survey at 18 to 20 weeks’ gestation should be done to detect possible malformations

- Assessment of cervical length, performed every 2 weeks from the 16th to the 28th week, may help predict premature delivery—but is not definitive

- Assessment of fetal growth every 4 weeks in dichorionic twins and every 2 weeks in monochorionic twins can alert you to potential problems. This is particularly important for detecting signs of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Congenital anomalies. These occur 2 to 3 times as often in monochorionic twins, and have been reported in as many as 10% of such pregnancies. Reported anomalies include midline defects, cloacal abnormalities, neural tube defects, ventral wall defects, craniofacial abnormalities, conjoined twins, and acardiac twins.9-11 In light of these risks, a detailed anatomic survey is suggested for all twins.

Heart defects. The incidence of congenital heart defects is 4 times greater in monochorionic twins, even in the absence of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS).12 Cardiac malformations may occur secondary to abnormal lateralization during embryogenesis or result from an abnormal vascular distribution in the shared placenta.9,10 The presence of abnormal vascular communications may also cause limb reduction defects and the rare acardiac twin.

Long-term neurologic morbidity. In one series, the incidence of cerebral palsy was 8%, compared with 1% among dichorionic twins. In twins followed to 2 years of age, rates of minor neurologic morbidity were 15% in monochorionic twins and 3% in dichorionic twins. The overall rate of neurologic disorders in monochorionic twins was 23%, regardless of fetal weight.13 At 4 years, long-term neurologic morbidity was particularly high in single survivors of a monochorionic pair; the incidence of cerebral palsy has been reported to be as high as 50% in single survivors, compared with 14.3% in cases in which both twins survived.14

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. In this condition, abnormal vascular connections arise in the shared placenta, allowing blood to be shunted from one fetus to the other. The syndrome is unique to monochorionic gestations and occurs in 15% to 20% of cases.15 A significant percentage of neurologic morbidity is probably the result of TTTS. To evaluate for TTTS, include a detailed anatomic survey and serial US every 2 weeks beginning in the second trimester as part of the surveillance of monochorionic twin gestations. (See “TTTS: Diagnosis, staging, treatment.”)

Twin-related morbidity and mortality are directly related to chorionicity. Twin embryos in a single chorion (monochorionic twins) have a higher rate of perinatal morbidity and mortality than do twins in separate sacs (dichorionic twins). To some extent, the higher risk faced by monochorionic twins—of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and certain structural and chromosomal abnormalities, for example—is the result of complications uniquely related to having a single placenta. But recent evidence also suggests that the higher risk of adverse outcomes is associated with monochorionicity itself, independent of the complications attributable to the single placenta.1

When twins develop in separate chorionic sacs, the risks are not as great. All fraternal twins (approximately 2/3 of all twins) are dichorionic and, therefore, at lower risk of an adverse outcome. The situation is more complex with identical (monozygotic) twins, however: Most (70%) are monochorionic, but approximately one third (30%) have separate chorionic sacs and are therefore dichorionic.

Reference

1. Leduc L, Takser L, Rinfret D. Persistence of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes in monochorionic twins after exclusion of disorders unique to monochorionic placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1670-1675.

Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities

Estimating odds

Assessing the likelihood of a chromosomal abnormality (aneuploidy) in a multiple gestation is complicated by differences in twinning mechanisms (chorionicity versus zygosity) and by the increasing rate of dizygotic twinning with advancing maternal age. The risk is greater in dizygotic twin gestations than in age-matched singleton gestations. The definition of advanced maternal age (AMA) in a twin pregnancy has ranged from 31 to 33 years of age in reports in the literature.2,16,17

The probability that a twin gestation contains a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality is directly related to zygosity. Each twin in a dizygotic gestation carries an independent risk, so the composite risk for the pregnancy is a summation of the independent risk for each fetus. For monozygotic twins, the risk is similar to the age-related risk in a singleton gestation. Presumptions about zygosity are based on chorionicity: Almost all (90%) dichorionic twins are dizygotic and all monochorionic twins are monozygotic.

What is the utility of noninvasive screening?

Multiple gestations can be screened for aneuploidy using maternal age, maternal serum markers, and nuchal translucency (NT) on US, or combinations of these assessments.

When first-trimester serum markers (free β-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A [PAPPA]) are combined with NT and maternal age, a pregnancy-specific risk can be calculated that includes the individual contribution of each fetus, thus yielding an improved detection rate. In monochorionic twins, the NTs are averaged to calculate a single risk for the entire pregnancy. In dichorionic twins, the risk for each fetus is calculated independently and then summed to establish a pregnancy-specific risk. The combined test has a reported detection rate of 84% for monochorionic twins and 70% for dichorionic twins, compared with detection rates of 85% to 87% for singletons at a 5% false-positive rate.18,19 The integrated test (combined test plus measurement of second-trimester serum analytes) has a 93% detection rate for monochorionic twins and a 78% detection rate for dichorionic twins, compared with 95% to 96% for singletons at the same 5% false-positive rate.18,19 Second-trimester screening has a lower detection rate in both singleton and twin gestations.

The diagnosis of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) depends on the presence of a single monochorionic placenta and abnormalities in the volume of amniotic fluid (the polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios sequence). The syndrome may have an abrupt or gradual onset, heralded by discordancy and restriction in the growth of the 2 fetuses.

The natural history of the syndrome and treatment outcome are based on a staging system described by Quintero and colleagues1:

Stage I is characterized by polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios with the bladder still visible in the donor twin

Stage II The donor bladder is no longer visible

Stage III is defined by abnormal Doppler studies showing absent or reversed flow in the umbilical artery, reversed flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile umbilical venous flow

Stage IV is indicated by hydrops in either twin

Stage V One or both twins die.

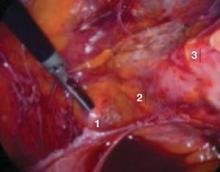

The prognosis for TTTS grows poorer with increasing stage and is poor if the condition goes untreated, with a reported survival rate of only 25% to 50% for 1 twin when the diagnosis is made in the second trimester.2,3 Treatment options include removal of excess amniotic fluid through serial amniocenteses (amnioreduction), fetoscopic laser coagulation of communicating vessels, selective fetocide, and perforation of the membrane that separates the twins (septostomy).

Serial amnioreduction is the most common procedure for treating TTTS. When Senat and colleagues compared the efficacy of serial amnioreduction with fetoscopic laser occlusion in a randomized control trial, however, they found that the laser group had a significantly higher likelihood of survival of at least 1 twin (76%) than the amnioreduction group (56%).4

Septostomy. A recently published randomized trial in which amnioreduction was compared with septostomy found no difference in survival between the 2 treatments.5 Septostomy often has the advantage of requiring only 1 procedure to be successful, whereas repeated amniocenteses are necessary in serial amnioreduction. Septostomy does carry the risk of creating a single amnion, as the size of the membranous defect created by the perforation is difficult to control.

Selective fetocide using US-guided cord occlusion or radiofrequency ablation has been described when there is a coexisting fetal anomaly, growth restriction, or a chromosomal abnormality in 1 twin (heterokaryotypia).6,7 Use of bipolar coagulation in this setting has been associated with a liveborn in 83% of cases and intact neurologic survival in 70%.7 Radiofrequency ablation has also been described for selective fetal termination in monochorionic placentation with an abnormality in 1 twin.6 Data presented at the 2006 annual meeting for the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine showed no difference in the overall complication rate between these 2 techniques of selective fetocide.8

References

1. Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Allen MH, Bornick PW, Johnson PK, Kruger M. Staging of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol. 1999;19:550-555.

2. Berghella V, Kaufman M. Natural history of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:480-484.

3. Bromley B, Frigoletto FD, Setroff JA, Benacerraf BR. The natural history of oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios sequence in monochorionic diamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:317-320.

4. Senat MV, Deprest J, Boulvain M, Paupe A, Winer N, Ville Y. Endoscopic laser surgery versus serial amnioreduction for severe twin to twin transfusion syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:136-144.

5. Moise KJ, Dorman K, Lamvu G, et al. A randomized trial of amnioreduction versus septostomy in the treatment of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:701-707.

6. Robyr R, Yamamoto M, Ville Y. Selective feticide in complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies using ultrasound-guided bipolar cord coagulation. BJOG. 2005;112:1344-1348.

7. Shevell T, Malone FD, Weintraub J, Harshwardhan MT, D’Alton ME. Radiofrequency ablation in a monochorionic twin discordant for fetal anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:575-576.

8. Bebbington M, Danzer E, Johnson M, Wilson RD. RFA vs cord coagulation in complex monochorionic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S192.-

Prenatal diagnosis

Given the lower detection rate of aneuploidy in twin gestations and the associated increase in aneuploidy with advancing maternal age, many patients choose to undergo prenatal diagnosis rather than relying on screening. On the basis of maternal age alone, invasive prenatal diagnosis can be offered to women who will be 31 years or older at their estimated due date.

Available diagnostic options include chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis. CVS is performed at an earlier gestational age (10 to 13 weeks) than amniocentesis (15 to 20 weeks). Multiples pose specific technical considerations for either procedure, and accurate fetal mapping is essential. Successful sampling with CVS can be performed in more than 99% of cases; the rate of cross-contamination is less than 1%.

Is there a risk of miscarriage?

In counseling patients about the risk of fetal death that CVS or amniocentesis may entail, the place to begin is the background loss rate, which is greater in twin than in single gestations. The reported background loss rate of twins at 24 weeks’ gestation or less ranges from 5.8% to 7.2%.20,21 In women of advanced maternal age (35 years and older), a background rate as high as 17.6% has been described.21 Once parents are aware of this, they have a context for weighing the risk of miscarriage that prenatal testing may hold.

The twin loss rate following amniocentesis has been evaluated in several studies. (See “Integrating evidence and experience: Does invasive prenatal testing raise the risk of miscarriage in a twin gestation?”)

A greatly elevated risk of preterm birth

Multiple gestations are at extremely high risk for premature delivery, and—like all premature newborns—these infants are at risk for a wide range of disabilities. Risk factors for premature delivery include history of second trimester pregnancy loss, preterm birth at less than 35 weeks’ gestation, more than 2 previous curettage procedures, cone biopsy, müllerian anomaly, and diethylstilbestrol exposure. Unfortunately, current yardsticks for predicting premature delivery in multiple pregnancy have serious limitations, and available interventions have not been particularly successful.

Predictors

Measurement of cervical length has been evaluated as a predictor of preterm delivery in a number of twin studies that were looking for a cutoff point that can predict which twins are at greatest risk. No such cutoff has been found.22-25

In general, studies demonstrate a low risk of preterm delivery for women who have a cervical length measurement of more than 35 mm at 24 to 26 weeks. A shorter cervical length correlates with premature delivery, but specific cutoffs have proved not to be sensitive predictors.

In the largest published series, To and colleagues evaluated 1,163 sets of twins undergoing routine care with cervical length assessments at 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation. They demonstrated a direct correlation between cervical length and preterm delivery, but were unable to define a cutoff sufficiently sensitive to be useful.25 A shortened cervix may be predictive of prematurity in general, but it does not allow the obstetrician to predict with certainty which mothers will give birth prematurely or how long a particular mother will carry.

Fetal fibronectin. The presence of fetal fibronectin (ffN) in cervicovaginal secretions is widely used as an adjunct to other potential predictors of preterm delivery. In a multistudy review that included symptomatic women, a negative ffN had a 99% negative predictive value but a poor positive predictive value (13% to 30%) for delivery within 7 to 10 days.26

Use of ffN in conjunction with cervical length has also been investigated in twin gestations. Although the negative predictive value of ffN remained high, the addition of ffN to cervical length assessment did not improve the positive predictive value of cervical length alone.27,28

Interventions

Cerclage is often used in high-risk singleton pregnancies in which a shortened cervix is seen on a sonogram. The utility of cerclage in twins is less clear. Randomized controlled trials comparing women at risk of premature delivery treated with cerclage and controls not considered at risk found no difference in the rate of premature delivery in the 2 groups.29,30 Meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials also found no benefit and, in fact, detected a possibility of actual harm. Cerclage twins were more likely to deliver early (at less than 35 weeks’ gestation) and had a 2.6 relative risk of perinatal mortality. The differences found in the meta-analysis were not statistically significant, however, and the overall sample size was small (n=48).31

The best available data seem to show that cerclage based on US indications of cervical shortening is not beneficial and may even be associated with worse outcome.

17-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) has been found to decrease the rate of recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations by almost 35%.32 Although twins are at increased risk of preterm birth, the use of 17P has not, however, been shown to be of benefit.33

Bed rest. A Cochrane Database review of 6 randomized controlled trials compared 1) patients with a multiple gestation who were offered bed rest in the hospital with 2) patients hospitalized for complications of pregnancy. The review found that bed rest did not reduce the risk of preterm birth or of perinatal mortality in the routinely hospitalized women. There was, however, a tendency to a decreased number of low-birth-weight infants born to women given bed rest.34

INTEGRATING EVIDENCE AND EXPERIENCE

The evidence for amniocentesis

Toth-Pal and colleagues compared the twin loss rate after amniocentesis in 155 twin pairs; twins who had a structural anomaly or aneuploidy were excluded. The investigators found a 3.87% loss rate at 24 weeks or less, compared with a background loss rate of 2.39% in twins who did not undergo the procedure—an insignificant difference.1

Yukobowich and colleagues compared 476 diamniotic, dichorionic twin pairs that had undergone amniocentesis with 1) 477 twin pairs undergoing routine US examination and 2) 489 singleton amniocenteses. They found a 4-week postprocedure loss rate of 2.7% in the amniocentesis twins, compared with 0.63% in twin controls who had routine US and 0.6% in the amniocentesis singletons.2 The difference is significant, but the reported loss rate is still less than, or comparable to, the reported background twin loss rate at 24 weeks or less.

Chorionic villus sampling

Only a few studies of the loss rate in twins after CVS have been published, but those that are available report a loss rate lower than, or comparable to, the background rate for twins generally. In a series of 169 twin pairs undergoing CVS at an average gestational age of 10 weeks, the risk of loss at 20 weeks or more was 1.7%.3

CVS and amniocentesis, in tandem

Although CVS and amniocentesis are not directly comparable given the difference in the timing of procedure, a few series have compared the risk of loss for the 2 procedures. Eighty-one twin pairs that underwent amniocentesis were compared with 161 twins undergoing CVS. The rate of spontaneous delivery at less than 28 weeks was 2.9% for amniocentesis, compared with 3.2% following CVS.4

To sum up

Invasive testing does not appear to increase the risk of fetal loss above the background loss rate for twins overall. Prenatal diagnosis as early as 10 weeks is a feasible option in a twin gestation, given the limitations of screening in multiple gestations.

References

1. Toth-Pal E, Papp C, Beke A, Ban Z, Papp Z. Genetic amniocentesis in multiple pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:138-144.

2. Yukobowich E, Anteby EY, Cohen SM, Lavy Y, Granat M, Yagel S. Risk of fetal loss in twin pregnancies undergoing second trimester amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:231-234.

3. Brambati B, Tului L, Guercilena S, Alberti E. Outcome of first-trimester chorionic villus sampling for genetic investigation in multiple pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:209-216.

4. Wapner RJ, Johnson A, Davis G, Urban A, Morgan P, Jackson L. Prenatal diagnosis in twin gestations: a comparison between second trimester amniocentesis and first trimester chorionic villus sampling. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:49-56.

Some parents elect fetal reduction

Given the high level of risk in a multiple pregnancy, reducing the number of fetuses is an option that some patients choose. A recent trend toward reduction to singleton pregnancy seems to be related to:

- increasing maternal age

- single parenthood

- financial considerations

- the increased medical risk to mother and fetuses associated with twins.35

Evans and colleagues found that, although the overall rate of reduction from twins to a singleton was 3%, the percentage (76%) of women older than 35 years who opted for such a reduction was disproportionately high.36

In a series of 1,000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction, Stone et al found that the pregnancy loss rate was lowest (2.5%) when there was reduction to a singleton gestation.37 A comparative analysis of 2,000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction presented at the 2006 meeting of the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine found that the percentage of twin gestations undergoing reduction to a singleton has increased from 4% to 15.6% between 1999 and 2006, with an increase in the overall incidence of reduction to a singleton from 11.8% to 31.8%.38

You should discuss pregnancy reduction with patients at high risk of pregnancy-associated complications such as cervical incompetence, preterm delivery, severe maternal cardiac disease, hypertension, diabetes, and uterine anomalies, as well as with patients who are carrying higher-order multiple gestations, in which the fetuses are at risk of problems.

Wrap-up: The tasks facing you in a multiple gestation

Start your management of a multiple gestation by taking the essential first step of determining the chorionicity of the fetuses.

Once you have done that, explain the risks of twin pregnancy and the particular risks of a single-sac pregnancy. Parents will want to know their risk of having a child with an anomaly; pay particular attention to the likelihood of a Down syndrome child. Noninvasive screening for Down syndrome and other chromosomal anomalies may be sufficient, but an older mother may prefer more definitive answers from CVS or amniocentesis.

You must prepare parents of a twin gestation for the risk of premature delivery. Cervical length assessment in the second trimester to early-third trimester may provide some indications of what is to happen, but the predictive value of this procedure is limited, and a shortened cervical length should be interpreted with caution.

In a monochorionic pregnancy, fetal growth should be assessed at regular intervals to evaluate for possible growth restriction or TTTS. If you detect evidence of abnormal fetal growth or amniotic fluid, US surveillance is indicated. Routine antepartum US surveillance of twins is not, however, recommended.2

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S. Births: final data 2004; Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;55:1-101.

2. Multiple gestation: Complicated twin, triplet and high-order multifetal pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin; 2004. No. 56.

3. Sepulveda W, Sebire NJ, Hughes K, Odibo A, Nicolaides KH. The lambda sign at 10–14 weeks of gestation as a predictor of chorionicity in twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:421-423.

4. Carroll SGM, Soothill PW, Abdel-Fattah SA, Porter H, Montague I, Kyle PM. Prediction of chorionicity in twin pregnancies at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:182-186.

5. Stenhouse E, Hardwick C, Maharaj S, Webb J, Kelly T, Mackenzie FM. Chorionicity determination in twin pregnancies; how accurate are we? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19:350-352.

6. Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, Hughes K, Sepulveda W, Nicolaides KH. The hidden mortality of monochorionic twin pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1203-1207.

7. Sperling L, Kiil C, Larsen LU, et al. Naturally conceived twins with monochorionic placentation have the highest risk of fetal loss. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:644-652.

8. Trevett T, Johnson A. Monochorionic twin pregnancies. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:475-494.

9. Rustico MA, Baietti MG, Coviello D, Orlandi E, Nicolini U. Managing twins discordant for fetal anomaly. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:766-771.

10. Hall JG. Developmental biology IV. Lancet. 2003;362:735-743.

11. Mohammed SN, Swan MC, Wall SA, Wilkie AO. Monozygotic twins discordant for frontonasal malformation. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130:384-388.

12. Karatza AA, Wolfenden JL, Taylor MJ, Wee L, Fisk NM, Gardiner HM. Influence of twin–twin transfusion syndrome on fetal cardiovascular structure and function; prospective case-control study of 136 monochorionic twin pregnancies. Heart. 2002;88:271-277.

13. Adegbite AL, Castille S, Ward S, Bajoria R. Neuromorbidity in preterm twins in relation to chorionicity and discordant birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:156-163.

14. Lopriore E, Nagel HTC, Vandenbussche FPHA, Walther FJ. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in twin–twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1314-1319.

15. Bromley B, Frigoletto FD, Setroff JA, Benacerraf BR. The natural history of oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios sequence in monochorionic diamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:317-320.

16. Rodis JF, Egan JFX, Craffey A, Ciarleglio L, Greenstein RM, Scorza WE. Calculated risk of chromosomal abnormalities in twin gestations. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:1037-1041.

17. Meyers C, Adam R, Dungan J, Prenger V. Aneuploidy in twin gestations; when is maternal age advanced? Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:248-251.

18. Wald J, Rish S. Prenatal screening for Down syndrome and neural tube defects in twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:740-745.

19. Malone FD, Canick JA, Ball RH, et al. The First- and Second-Trimester Evaluation of Risk (FASTER) Research Consortium. First trimester or second trimester screening, or both, for Down’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2001-2011.

20. Yaron Y, Bryant-Greenwood PK, Dave N, et al. Multifetal pregnancy reduction of triplets to twins: comparison with nonreduced triplets and twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1268-1271.

21. La Sala GB, Nucera G, Gallinelli A, Nicoli A, Villani MT, Blickstein I. Spontaneous embryonic loss following in vitro fertilization: incidence and effect on outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:741-746.

22. Imseis HM, Albert TA, Iams JD. Identifying twin gestations at low risk for preterm birth with a transvaginal ultrasonographic cervical measurement at 24 to 26 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1149-1155.

23. Vayssiere C, Favre R, Audibert F, et al. Cervical length and funneling at 22 and 27 weeks to predict spontaneous birth before 32 weeks in twin pregnancies: a French prospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1596-1604.

24. Guzman ER, Walters C, O’Reilly-Green C, et al. Use of cervical ultrasonography in prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in twin gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1103-1107.

25. To MS, Fonseca EB, Molina FS, Cacho AM, Nicolaides KH. Maternal characteristics and cervical length in prediction of spontaneous early preterm delivery in twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1360-1365.

26. Honest H, Bachmann LM, Gupta JK, Kleijnen J, Khan KS. Accuracy of cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin test in predicting risk of spontaneous preterm birth: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325:301.-

27. Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Miodovnik M, et al. The preterm prediction study: risk factors in twin gestations. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1047-1053.

28. Gibson JL, Macara LM, Owen P, Young D, Macauley J, Mackenzie F. Prediction of preterm delivery in twin pregnancy: a prospective, observational study of cervical length and fetal fibronectin testing. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:561-566.

29. Berghella V, Odibo AO, Tolosa JE. Cerclage for prevention of preterm birth in women with a short cervix found on transvaginal ultrasound examination: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1311-1317.

30. Rust OA, Atlas RO, Reed J, van Gaalen J, Baldussi J. Revisiting the short cervix detected by transvaginal ultrasound in the second trimester: why cerclage therapy may not help. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1098-1105.

31. Berghella V, Odibo AO, To MS, Rust OA, Althuisius SM. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography: meta-analysis of trials using individual patient-level data. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:181-189.

32. Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

33. Caritis S, Rouse D. NICHD MFMU Network. A randomized controlled trial of 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S2.-

34. Crowther CA. Hospitalisation and bed rest for multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD000110.-

35. Evans MI, Ciorica D, Britt DW, Fletcher JC. Update on selective reduction. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:807-813.

36. Evans MI, Kaufman MI, Urban AJ, Britt DW, Fletcher JC. Fetal reduction from twins to a singleton: a reasonable consideration. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:102-109.

37. Stone J, Eddleman K, Lynch L, Berkowitz RL. A single center experience with 1000 consecutive cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1163-1167.

38. Stone J, Matho A, Berkowitz R, Belogolovkin V, Eddleman K. Evolving trends in 2,000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S184.-

Multiple gestations are far more common today than they once were—up 70% since 1980.1 Today, every 1,000 live births include 32.3 sets of twins, a 2% increase in the rate of twin births since 2004. Why this phenomenon is occurring is not entirely understood but, certainly, the trend toward older maternal age and the emergence of assisted reproduction are both part of the explanation.

Multiple gestations are of particular concern to obstetricians because, even though they remain relatively rare, they are responsible for a significant percentage of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The difficulties that twins encounter are often associated with preterm birth and occur most often in identical twins developing within a single gestational sac. Those difficulties include malformation, chromosomal abnormalities, learning disability, behavioral problems, chronic lung disease, neuromuscular developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth. Women pregnant with twins are also at heightened risk, particularly of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes.2

Your task is to manage these risks so that the outlook for mother and infant is as favorable as possible.

Determining chorionicity in the first trimester

Ultrasonographic determination of chorionicity should be the first step in the management of a twin gestation. The determination should be made as early as possible in the pregnancy because it has an immediate impact on counseling, risk of miscarriage, and efficacy of noninvasive screening. (See “Is there 1 sac, or more? Key to predicting risk.”)

The accuracy of ultrasonography (US) in determining chorionicity depends on gestational age. US predictors of dichorionicity include:

- gender discordance

- separate placentas

- the so-called twin-peak sign (also called the lambda sign) (FIGURE 1), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs; compare this with FIGURE 2, showing monochorionic twins with the absence of an intervening placenta

- an intertwin membrane thicker than 1.5 mm to 2.0 mm.

US examination can accurately identify chorionicity at 10 to 14 weeks’ gestation, with overall sensitivity that is reported to be as high as 100%.3-5

FIGURE 1

The twin-peak sign on US

This dichorionic–diamnionic twin gestation demonstrates the so-called twin peak, or lambda, sign (arrow), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs.

FIGURE 2

Monochorionic–diamnionic twin gestation

This US scan of a monochorionic twin gestation reveals the absence of an intervening placenta

Monochorionic twins

Twins who share a gestational sac are more likely than 2-sac twins to suffer spontaneous loss, congenital anomalies, growth restriction and discordancy, preterm delivery, and neurologic morbidity.

Spontaneous loss. In 1 comparative series, the risk of pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks’ gestation was 12.2% for monochorionic twins, compared with 1.8% for dichorionic twins.6 Spontaneously conceived monochorionic twins may have the highest risk of loss.7 However, monochorionic twins occur more often in conceptions achieved by assisted reproductive technology—at a rate 3 to 10 times higher than the background rate of monochorionic twinning.8

- A multiple gestation involves a higher level of risk than a singleton pregnancy

- Chorionicity is the basis for determining risk. Twins within a single sac (monochorionic) are at higher risk of malformation, Down syndrome, and premature birth

- The risk of Down syndrome can be estimated by noninvasive screening in the first trimester and by chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis later in the pregnancy

- A detailed anatomic survey at 18 to 20 weeks’ gestation should be done to detect possible malformations

- Assessment of cervical length, performed every 2 weeks from the 16th to the 28th week, may help predict premature delivery—but is not definitive

- Assessment of fetal growth every 4 weeks in dichorionic twins and every 2 weeks in monochorionic twins can alert you to potential problems. This is particularly important for detecting signs of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Congenital anomalies. These occur 2 to 3 times as often in monochorionic twins, and have been reported in as many as 10% of such pregnancies. Reported anomalies include midline defects, cloacal abnormalities, neural tube defects, ventral wall defects, craniofacial abnormalities, conjoined twins, and acardiac twins.9-11 In light of these risks, a detailed anatomic survey is suggested for all twins.

Heart defects. The incidence of congenital heart defects is 4 times greater in monochorionic twins, even in the absence of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS).12 Cardiac malformations may occur secondary to abnormal lateralization during embryogenesis or result from an abnormal vascular distribution in the shared placenta.9,10 The presence of abnormal vascular communications may also cause limb reduction defects and the rare acardiac twin.

Long-term neurologic morbidity. In one series, the incidence of cerebral palsy was 8%, compared with 1% among dichorionic twins. In twins followed to 2 years of age, rates of minor neurologic morbidity were 15% in monochorionic twins and 3% in dichorionic twins. The overall rate of neurologic disorders in monochorionic twins was 23%, regardless of fetal weight.13 At 4 years, long-term neurologic morbidity was particularly high in single survivors of a monochorionic pair; the incidence of cerebral palsy has been reported to be as high as 50% in single survivors, compared with 14.3% in cases in which both twins survived.14

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. In this condition, abnormal vascular connections arise in the shared placenta, allowing blood to be shunted from one fetus to the other. The syndrome is unique to monochorionic gestations and occurs in 15% to 20% of cases.15 A significant percentage of neurologic morbidity is probably the result of TTTS. To evaluate for TTTS, include a detailed anatomic survey and serial US every 2 weeks beginning in the second trimester as part of the surveillance of monochorionic twin gestations. (See “TTTS: Diagnosis, staging, treatment.”)

Twin-related morbidity and mortality are directly related to chorionicity. Twin embryos in a single chorion (monochorionic twins) have a higher rate of perinatal morbidity and mortality than do twins in separate sacs (dichorionic twins). To some extent, the higher risk faced by monochorionic twins—of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and certain structural and chromosomal abnormalities, for example—is the result of complications uniquely related to having a single placenta. But recent evidence also suggests that the higher risk of adverse outcomes is associated with monochorionicity itself, independent of the complications attributable to the single placenta.1

When twins develop in separate chorionic sacs, the risks are not as great. All fraternal twins (approximately 2/3 of all twins) are dichorionic and, therefore, at lower risk of an adverse outcome. The situation is more complex with identical (monozygotic) twins, however: Most (70%) are monochorionic, but approximately one third (30%) have separate chorionic sacs and are therefore dichorionic.

Reference

1. Leduc L, Takser L, Rinfret D. Persistence of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes in monochorionic twins after exclusion of disorders unique to monochorionic placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1670-1675.

Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities

Estimating odds

Assessing the likelihood of a chromosomal abnormality (aneuploidy) in a multiple gestation is complicated by differences in twinning mechanisms (chorionicity versus zygosity) and by the increasing rate of dizygotic twinning with advancing maternal age. The risk is greater in dizygotic twin gestations than in age-matched singleton gestations. The definition of advanced maternal age (AMA) in a twin pregnancy has ranged from 31 to 33 years of age in reports in the literature.2,16,17

The probability that a twin gestation contains a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality is directly related to zygosity. Each twin in a dizygotic gestation carries an independent risk, so the composite risk for the pregnancy is a summation of the independent risk for each fetus. For monozygotic twins, the risk is similar to the age-related risk in a singleton gestation. Presumptions about zygosity are based on chorionicity: Almost all (90%) dichorionic twins are dizygotic and all monochorionic twins are monozygotic.

What is the utility of noninvasive screening?

Multiple gestations can be screened for aneuploidy using maternal age, maternal serum markers, and nuchal translucency (NT) on US, or combinations of these assessments.

When first-trimester serum markers (free β-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A [PAPPA]) are combined with NT and maternal age, a pregnancy-specific risk can be calculated that includes the individual contribution of each fetus, thus yielding an improved detection rate. In monochorionic twins, the NTs are averaged to calculate a single risk for the entire pregnancy. In dichorionic twins, the risk for each fetus is calculated independently and then summed to establish a pregnancy-specific risk. The combined test has a reported detection rate of 84% for monochorionic twins and 70% for dichorionic twins, compared with detection rates of 85% to 87% for singletons at a 5% false-positive rate.18,19 The integrated test (combined test plus measurement of second-trimester serum analytes) has a 93% detection rate for monochorionic twins and a 78% detection rate for dichorionic twins, compared with 95% to 96% for singletons at the same 5% false-positive rate.18,19 Second-trimester screening has a lower detection rate in both singleton and twin gestations.

The diagnosis of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) depends on the presence of a single monochorionic placenta and abnormalities in the volume of amniotic fluid (the polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios sequence). The syndrome may have an abrupt or gradual onset, heralded by discordancy and restriction in the growth of the 2 fetuses.

The natural history of the syndrome and treatment outcome are based on a staging system described by Quintero and colleagues1:

Stage I is characterized by polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios with the bladder still visible in the donor twin

Stage II The donor bladder is no longer visible

Stage III is defined by abnormal Doppler studies showing absent or reversed flow in the umbilical artery, reversed flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile umbilical venous flow

Stage IV is indicated by hydrops in either twin

Stage V One or both twins die.

The prognosis for TTTS grows poorer with increasing stage and is poor if the condition goes untreated, with a reported survival rate of only 25% to 50% for 1 twin when the diagnosis is made in the second trimester.2,3 Treatment options include removal of excess amniotic fluid through serial amniocenteses (amnioreduction), fetoscopic laser coagulation of communicating vessels, selective fetocide, and perforation of the membrane that separates the twins (septostomy).

Serial amnioreduction is the most common procedure for treating TTTS. When Senat and colleagues compared the efficacy of serial amnioreduction with fetoscopic laser occlusion in a randomized control trial, however, they found that the laser group had a significantly higher likelihood of survival of at least 1 twin (76%) than the amnioreduction group (56%).4

Septostomy. A recently published randomized trial in which amnioreduction was compared with septostomy found no difference in survival between the 2 treatments.5 Septostomy often has the advantage of requiring only 1 procedure to be successful, whereas repeated amniocenteses are necessary in serial amnioreduction. Septostomy does carry the risk of creating a single amnion, as the size of the membranous defect created by the perforation is difficult to control.

Selective fetocide using US-guided cord occlusion or radiofrequency ablation has been described when there is a coexisting fetal anomaly, growth restriction, or a chromosomal abnormality in 1 twin (heterokaryotypia).6,7 Use of bipolar coagulation in this setting has been associated with a liveborn in 83% of cases and intact neurologic survival in 70%.7 Radiofrequency ablation has also been described for selective fetal termination in monochorionic placentation with an abnormality in 1 twin.6 Data presented at the 2006 annual meeting for the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine showed no difference in the overall complication rate between these 2 techniques of selective fetocide.8

References

1. Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Allen MH, Bornick PW, Johnson PK, Kruger M. Staging of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol. 1999;19:550-555.

2. Berghella V, Kaufman M. Natural history of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:480-484.

3. Bromley B, Frigoletto FD, Setroff JA, Benacerraf BR. The natural history of oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios sequence in monochorionic diamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:317-320.

4. Senat MV, Deprest J, Boulvain M, Paupe A, Winer N, Ville Y. Endoscopic laser surgery versus serial amnioreduction for severe twin to twin transfusion syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:136-144.

5. Moise KJ, Dorman K, Lamvu G, et al. A randomized trial of amnioreduction versus septostomy in the treatment of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:701-707.

6. Robyr R, Yamamoto M, Ville Y. Selective feticide in complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies using ultrasound-guided bipolar cord coagulation. BJOG. 2005;112:1344-1348.

7. Shevell T, Malone FD, Weintraub J, Harshwardhan MT, D’Alton ME. Radiofrequency ablation in a monochorionic twin discordant for fetal anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:575-576.

8. Bebbington M, Danzer E, Johnson M, Wilson RD. RFA vs cord coagulation in complex monochorionic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S192.-

Prenatal diagnosis

Given the lower detection rate of aneuploidy in twin gestations and the associated increase in aneuploidy with advancing maternal age, many patients choose to undergo prenatal diagnosis rather than relying on screening. On the basis of maternal age alone, invasive prenatal diagnosis can be offered to women who will be 31 years or older at their estimated due date.

Available diagnostic options include chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis. CVS is performed at an earlier gestational age (10 to 13 weeks) than amniocentesis (15 to 20 weeks). Multiples pose specific technical considerations for either procedure, and accurate fetal mapping is essential. Successful sampling with CVS can be performed in more than 99% of cases; the rate of cross-contamination is less than 1%.

Is there a risk of miscarriage?

In counseling patients about the risk of fetal death that CVS or amniocentesis may entail, the place to begin is the background loss rate, which is greater in twin than in single gestations. The reported background loss rate of twins at 24 weeks’ gestation or less ranges from 5.8% to 7.2%.20,21 In women of advanced maternal age (35 years and older), a background rate as high as 17.6% has been described.21 Once parents are aware of this, they have a context for weighing the risk of miscarriage that prenatal testing may hold.

The twin loss rate following amniocentesis has been evaluated in several studies. (See “Integrating evidence and experience: Does invasive prenatal testing raise the risk of miscarriage in a twin gestation?”)

A greatly elevated risk of preterm birth

Multiple gestations are at extremely high risk for premature delivery, and—like all premature newborns—these infants are at risk for a wide range of disabilities. Risk factors for premature delivery include history of second trimester pregnancy loss, preterm birth at less than 35 weeks’ gestation, more than 2 previous curettage procedures, cone biopsy, müllerian anomaly, and diethylstilbestrol exposure. Unfortunately, current yardsticks for predicting premature delivery in multiple pregnancy have serious limitations, and available interventions have not been particularly successful.

Predictors

Measurement of cervical length has been evaluated as a predictor of preterm delivery in a number of twin studies that were looking for a cutoff point that can predict which twins are at greatest risk. No such cutoff has been found.22-25

In general, studies demonstrate a low risk of preterm delivery for women who have a cervical length measurement of more than 35 mm at 24 to 26 weeks. A shorter cervical length correlates with premature delivery, but specific cutoffs have proved not to be sensitive predictors.

In the largest published series, To and colleagues evaluated 1,163 sets of twins undergoing routine care with cervical length assessments at 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation. They demonstrated a direct correlation between cervical length and preterm delivery, but were unable to define a cutoff sufficiently sensitive to be useful.25 A shortened cervix may be predictive of prematurity in general, but it does not allow the obstetrician to predict with certainty which mothers will give birth prematurely or how long a particular mother will carry.

Fetal fibronectin. The presence of fetal fibronectin (ffN) in cervicovaginal secretions is widely used as an adjunct to other potential predictors of preterm delivery. In a multistudy review that included symptomatic women, a negative ffN had a 99% negative predictive value but a poor positive predictive value (13% to 30%) for delivery within 7 to 10 days.26

Use of ffN in conjunction with cervical length has also been investigated in twin gestations. Although the negative predictive value of ffN remained high, the addition of ffN to cervical length assessment did not improve the positive predictive value of cervical length alone.27,28

Interventions

Cerclage is often used in high-risk singleton pregnancies in which a shortened cervix is seen on a sonogram. The utility of cerclage in twins is less clear. Randomized controlled trials comparing women at risk of premature delivery treated with cerclage and controls not considered at risk found no difference in the rate of premature delivery in the 2 groups.29,30 Meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials also found no benefit and, in fact, detected a possibility of actual harm. Cerclage twins were more likely to deliver early (at less than 35 weeks’ gestation) and had a 2.6 relative risk of perinatal mortality. The differences found in the meta-analysis were not statistically significant, however, and the overall sample size was small (n=48).31

The best available data seem to show that cerclage based on US indications of cervical shortening is not beneficial and may even be associated with worse outcome.

17-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) has been found to decrease the rate of recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations by almost 35%.32 Although twins are at increased risk of preterm birth, the use of 17P has not, however, been shown to be of benefit.33

Bed rest. A Cochrane Database review of 6 randomized controlled trials compared 1) patients with a multiple gestation who were offered bed rest in the hospital with 2) patients hospitalized for complications of pregnancy. The review found that bed rest did not reduce the risk of preterm birth or of perinatal mortality in the routinely hospitalized women. There was, however, a tendency to a decreased number of low-birth-weight infants born to women given bed rest.34

INTEGRATING EVIDENCE AND EXPERIENCE

The evidence for amniocentesis

Toth-Pal and colleagues compared the twin loss rate after amniocentesis in 155 twin pairs; twins who had a structural anomaly or aneuploidy were excluded. The investigators found a 3.87% loss rate at 24 weeks or less, compared with a background loss rate of 2.39% in twins who did not undergo the procedure—an insignificant difference.1

Yukobowich and colleagues compared 476 diamniotic, dichorionic twin pairs that had undergone amniocentesis with 1) 477 twin pairs undergoing routine US examination and 2) 489 singleton amniocenteses. They found a 4-week postprocedure loss rate of 2.7% in the amniocentesis twins, compared with 0.63% in twin controls who had routine US and 0.6% in the amniocentesis singletons.2 The difference is significant, but the reported loss rate is still less than, or comparable to, the reported background twin loss rate at 24 weeks or less.

Chorionic villus sampling

Only a few studies of the loss rate in twins after CVS have been published, but those that are available report a loss rate lower than, or comparable to, the background rate for twins generally. In a series of 169 twin pairs undergoing CVS at an average gestational age of 10 weeks, the risk of loss at 20 weeks or more was 1.7%.3

CVS and amniocentesis, in tandem

Although CVS and amniocentesis are not directly comparable given the difference in the timing of procedure, a few series have compared the risk of loss for the 2 procedures. Eighty-one twin pairs that underwent amniocentesis were compared with 161 twins undergoing CVS. The rate of spontaneous delivery at less than 28 weeks was 2.9% for amniocentesis, compared with 3.2% following CVS.4

To sum up

Invasive testing does not appear to increase the risk of fetal loss above the background loss rate for twins overall. Prenatal diagnosis as early as 10 weeks is a feasible option in a twin gestation, given the limitations of screening in multiple gestations.

References

1. Toth-Pal E, Papp C, Beke A, Ban Z, Papp Z. Genetic amniocentesis in multiple pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:138-144.

2. Yukobowich E, Anteby EY, Cohen SM, Lavy Y, Granat M, Yagel S. Risk of fetal loss in twin pregnancies undergoing second trimester amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:231-234.

3. Brambati B, Tului L, Guercilena S, Alberti E. Outcome of first-trimester chorionic villus sampling for genetic investigation in multiple pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:209-216.

4. Wapner RJ, Johnson A, Davis G, Urban A, Morgan P, Jackson L. Prenatal diagnosis in twin gestations: a comparison between second trimester amniocentesis and first trimester chorionic villus sampling. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:49-56.

Some parents elect fetal reduction

Given the high level of risk in a multiple pregnancy, reducing the number of fetuses is an option that some patients choose. A recent trend toward reduction to singleton pregnancy seems to be related to:

- increasing maternal age

- single parenthood

- financial considerations

- the increased medical risk to mother and fetuses associated with twins.35

Evans and colleagues found that, although the overall rate of reduction from twins to a singleton was 3%, the percentage (76%) of women older than 35 years who opted for such a reduction was disproportionately high.36

In a series of 1,000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction, Stone et al found that the pregnancy loss rate was lowest (2.5%) when there was reduction to a singleton gestation.37 A comparative analysis of 2,000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction presented at the 2006 meeting of the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine found that the percentage of twin gestations undergoing reduction to a singleton has increased from 4% to 15.6% between 1999 and 2006, with an increase in the overall incidence of reduction to a singleton from 11.8% to 31.8%.38

You should discuss pregnancy reduction with patients at high risk of pregnancy-associated complications such as cervical incompetence, preterm delivery, severe maternal cardiac disease, hypertension, diabetes, and uterine anomalies, as well as with patients who are carrying higher-order multiple gestations, in which the fetuses are at risk of problems.

Wrap-up: The tasks facing you in a multiple gestation

Start your management of a multiple gestation by taking the essential first step of determining the chorionicity of the fetuses.

Once you have done that, explain the risks of twin pregnancy and the particular risks of a single-sac pregnancy. Parents will want to know their risk of having a child with an anomaly; pay particular attention to the likelihood of a Down syndrome child. Noninvasive screening for Down syndrome and other chromosomal anomalies may be sufficient, but an older mother may prefer more definitive answers from CVS or amniocentesis.

You must prepare parents of a twin gestation for the risk of premature delivery. Cervical length assessment in the second trimester to early-third trimester may provide some indications of what is to happen, but the predictive value of this procedure is limited, and a shortened cervical length should be interpreted with caution.

In a monochorionic pregnancy, fetal growth should be assessed at regular intervals to evaluate for possible growth restriction or TTTS. If you detect evidence of abnormal fetal growth or amniotic fluid, US surveillance is indicated. Routine antepartum US surveillance of twins is not, however, recommended.2

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Multiple gestations are far more common today than they once were—up 70% since 1980.1 Today, every 1,000 live births include 32.3 sets of twins, a 2% increase in the rate of twin births since 2004. Why this phenomenon is occurring is not entirely understood but, certainly, the trend toward older maternal age and the emergence of assisted reproduction are both part of the explanation.

Multiple gestations are of particular concern to obstetricians because, even though they remain relatively rare, they are responsible for a significant percentage of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The difficulties that twins encounter are often associated with preterm birth and occur most often in identical twins developing within a single gestational sac. Those difficulties include malformation, chromosomal abnormalities, learning disability, behavioral problems, chronic lung disease, neuromuscular developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth. Women pregnant with twins are also at heightened risk, particularly of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes.2

Your task is to manage these risks so that the outlook for mother and infant is as favorable as possible.

Determining chorionicity in the first trimester

Ultrasonographic determination of chorionicity should be the first step in the management of a twin gestation. The determination should be made as early as possible in the pregnancy because it has an immediate impact on counseling, risk of miscarriage, and efficacy of noninvasive screening. (See “Is there 1 sac, or more? Key to predicting risk.”)

The accuracy of ultrasonography (US) in determining chorionicity depends on gestational age. US predictors of dichorionicity include:

- gender discordance

- separate placentas

- the so-called twin-peak sign (also called the lambda sign) (FIGURE 1), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs; compare this with FIGURE 2, showing monochorionic twins with the absence of an intervening placenta

- an intertwin membrane thicker than 1.5 mm to 2.0 mm.

US examination can accurately identify chorionicity at 10 to 14 weeks’ gestation, with overall sensitivity that is reported to be as high as 100%.3-5

FIGURE 1

The twin-peak sign on US

This dichorionic–diamnionic twin gestation demonstrates the so-called twin peak, or lambda, sign (arrow), in which the placenta appears to extend a short distance between the gestational sacs.

FIGURE 2

Monochorionic–diamnionic twin gestation

This US scan of a monochorionic twin gestation reveals the absence of an intervening placenta

Monochorionic twins

Twins who share a gestational sac are more likely than 2-sac twins to suffer spontaneous loss, congenital anomalies, growth restriction and discordancy, preterm delivery, and neurologic morbidity.

Spontaneous loss. In 1 comparative series, the risk of pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks’ gestation was 12.2% for monochorionic twins, compared with 1.8% for dichorionic twins.6 Spontaneously conceived monochorionic twins may have the highest risk of loss.7 However, monochorionic twins occur more often in conceptions achieved by assisted reproductive technology—at a rate 3 to 10 times higher than the background rate of monochorionic twinning.8

- A multiple gestation involves a higher level of risk than a singleton pregnancy

- Chorionicity is the basis for determining risk. Twins within a single sac (monochorionic) are at higher risk of malformation, Down syndrome, and premature birth

- The risk of Down syndrome can be estimated by noninvasive screening in the first trimester and by chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis later in the pregnancy

- A detailed anatomic survey at 18 to 20 weeks’ gestation should be done to detect possible malformations

- Assessment of cervical length, performed every 2 weeks from the 16th to the 28th week, may help predict premature delivery—but is not definitive

- Assessment of fetal growth every 4 weeks in dichorionic twins and every 2 weeks in monochorionic twins can alert you to potential problems. This is particularly important for detecting signs of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Congenital anomalies. These occur 2 to 3 times as often in monochorionic twins, and have been reported in as many as 10% of such pregnancies. Reported anomalies include midline defects, cloacal abnormalities, neural tube defects, ventral wall defects, craniofacial abnormalities, conjoined twins, and acardiac twins.9-11 In light of these risks, a detailed anatomic survey is suggested for all twins.

Heart defects. The incidence of congenital heart defects is 4 times greater in monochorionic twins, even in the absence of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS).12 Cardiac malformations may occur secondary to abnormal lateralization during embryogenesis or result from an abnormal vascular distribution in the shared placenta.9,10 The presence of abnormal vascular communications may also cause limb reduction defects and the rare acardiac twin.

Long-term neurologic morbidity. In one series, the incidence of cerebral palsy was 8%, compared with 1% among dichorionic twins. In twins followed to 2 years of age, rates of minor neurologic morbidity were 15% in monochorionic twins and 3% in dichorionic twins. The overall rate of neurologic disorders in monochorionic twins was 23%, regardless of fetal weight.13 At 4 years, long-term neurologic morbidity was particularly high in single survivors of a monochorionic pair; the incidence of cerebral palsy has been reported to be as high as 50% in single survivors, compared with 14.3% in cases in which both twins survived.14

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. In this condition, abnormal vascular connections arise in the shared placenta, allowing blood to be shunted from one fetus to the other. The syndrome is unique to monochorionic gestations and occurs in 15% to 20% of cases.15 A significant percentage of neurologic morbidity is probably the result of TTTS. To evaluate for TTTS, include a detailed anatomic survey and serial US every 2 weeks beginning in the second trimester as part of the surveillance of monochorionic twin gestations. (See “TTTS: Diagnosis, staging, treatment.”)

Twin-related morbidity and mortality are directly related to chorionicity. Twin embryos in a single chorion (monochorionic twins) have a higher rate of perinatal morbidity and mortality than do twins in separate sacs (dichorionic twins). To some extent, the higher risk faced by monochorionic twins—of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and certain structural and chromosomal abnormalities, for example—is the result of complications uniquely related to having a single placenta. But recent evidence also suggests that the higher risk of adverse outcomes is associated with monochorionicity itself, independent of the complications attributable to the single placenta.1

When twins develop in separate chorionic sacs, the risks are not as great. All fraternal twins (approximately 2/3 of all twins) are dichorionic and, therefore, at lower risk of an adverse outcome. The situation is more complex with identical (monozygotic) twins, however: Most (70%) are monochorionic, but approximately one third (30%) have separate chorionic sacs and are therefore dichorionic.

Reference

1. Leduc L, Takser L, Rinfret D. Persistence of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes in monochorionic twins after exclusion of disorders unique to monochorionic placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1670-1675.

Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities

Estimating odds

Assessing the likelihood of a chromosomal abnormality (aneuploidy) in a multiple gestation is complicated by differences in twinning mechanisms (chorionicity versus zygosity) and by the increasing rate of dizygotic twinning with advancing maternal age. The risk is greater in dizygotic twin gestations than in age-matched singleton gestations. The definition of advanced maternal age (AMA) in a twin pregnancy has ranged from 31 to 33 years of age in reports in the literature.2,16,17

The probability that a twin gestation contains a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality is directly related to zygosity. Each twin in a dizygotic gestation carries an independent risk, so the composite risk for the pregnancy is a summation of the independent risk for each fetus. For monozygotic twins, the risk is similar to the age-related risk in a singleton gestation. Presumptions about zygosity are based on chorionicity: Almost all (90%) dichorionic twins are dizygotic and all monochorionic twins are monozygotic.

What is the utility of noninvasive screening?

Multiple gestations can be screened for aneuploidy using maternal age, maternal serum markers, and nuchal translucency (NT) on US, or combinations of these assessments.

When first-trimester serum markers (free β-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A [PAPPA]) are combined with NT and maternal age, a pregnancy-specific risk can be calculated that includes the individual contribution of each fetus, thus yielding an improved detection rate. In monochorionic twins, the NTs are averaged to calculate a single risk for the entire pregnancy. In dichorionic twins, the risk for each fetus is calculated independently and then summed to establish a pregnancy-specific risk. The combined test has a reported detection rate of 84% for monochorionic twins and 70% for dichorionic twins, compared with detection rates of 85% to 87% for singletons at a 5% false-positive rate.18,19 The integrated test (combined test plus measurement of second-trimester serum analytes) has a 93% detection rate for monochorionic twins and a 78% detection rate for dichorionic twins, compared with 95% to 96% for singletons at the same 5% false-positive rate.18,19 Second-trimester screening has a lower detection rate in both singleton and twin gestations.

The diagnosis of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) depends on the presence of a single monochorionic placenta and abnormalities in the volume of amniotic fluid (the polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios sequence). The syndrome may have an abrupt or gradual onset, heralded by discordancy and restriction in the growth of the 2 fetuses.

The natural history of the syndrome and treatment outcome are based on a staging system described by Quintero and colleagues1:

Stage I is characterized by polyhydramnios–oligohydramnios with the bladder still visible in the donor twin

Stage II The donor bladder is no longer visible

Stage III is defined by abnormal Doppler studies showing absent or reversed flow in the umbilical artery, reversed flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile umbilical venous flow

Stage IV is indicated by hydrops in either twin

Stage V One or both twins die.

The prognosis for TTTS grows poorer with increasing stage and is poor if the condition goes untreated, with a reported survival rate of only 25% to 50% for 1 twin when the diagnosis is made in the second trimester.2,3 Treatment options include removal of excess amniotic fluid through serial amniocenteses (amnioreduction), fetoscopic laser coagulation of communicating vessels, selective fetocide, and perforation of the membrane that separates the twins (septostomy).

Serial amnioreduction is the most common procedure for treating TTTS. When Senat and colleagues compared the efficacy of serial amnioreduction with fetoscopic laser occlusion in a randomized control trial, however, they found that the laser group had a significantly higher likelihood of survival of at least 1 twin (76%) than the amnioreduction group (56%).4

Septostomy. A recently published randomized trial in which amnioreduction was compared with septostomy found no difference in survival between the 2 treatments.5 Septostomy often has the advantage of requiring only 1 procedure to be successful, whereas repeated amniocenteses are necessary in serial amnioreduction. Septostomy does carry the risk of creating a single amnion, as the size of the membranous defect created by the perforation is difficult to control.

Selective fetocide using US-guided cord occlusion or radiofrequency ablation has been described when there is a coexisting fetal anomaly, growth restriction, or a chromosomal abnormality in 1 twin (heterokaryotypia).6,7 Use of bipolar coagulation in this setting has been associated with a liveborn in 83% of cases and intact neurologic survival in 70%.7 Radiofrequency ablation has also been described for selective fetal termination in monochorionic placentation with an abnormality in 1 twin.6 Data presented at the 2006 annual meeting for the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine showed no difference in the overall complication rate between these 2 techniques of selective fetocide.8

References

1. Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Allen MH, Bornick PW, Johnson PK, Kruger M. Staging of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol. 1999;19:550-555.

2. Berghella V, Kaufman M. Natural history of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:480-484.

3. Bromley B, Frigoletto FD, Setroff JA, Benacerraf BR. The natural history of oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios sequence in monochorionic diamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:317-320.

4. Senat MV, Deprest J, Boulvain M, Paupe A, Winer N, Ville Y. Endoscopic laser surgery versus serial amnioreduction for severe twin to twin transfusion syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:136-144.

5. Moise KJ, Dorman K, Lamvu G, et al. A randomized trial of amnioreduction versus septostomy in the treatment of twin–twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:701-707.

6. Robyr R, Yamamoto M, Ville Y. Selective feticide in complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies using ultrasound-guided bipolar cord coagulation. BJOG. 2005;112:1344-1348.

7. Shevell T, Malone FD, Weintraub J, Harshwardhan MT, D’Alton ME. Radiofrequency ablation in a monochorionic twin discordant for fetal anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:575-576.

8. Bebbington M, Danzer E, Johnson M, Wilson RD. RFA vs cord coagulation in complex monochorionic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S192.-

Prenatal diagnosis

Given the lower detection rate of aneuploidy in twin gestations and the associated increase in aneuploidy with advancing maternal age, many patients choose to undergo prenatal diagnosis rather than relying on screening. On the basis of maternal age alone, invasive prenatal diagnosis can be offered to women who will be 31 years or older at their estimated due date.

Available diagnostic options include chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis. CVS is performed at an earlier gestational age (10 to 13 weeks) than amniocentesis (15 to 20 weeks). Multiples pose specific technical considerations for either procedure, and accurate fetal mapping is essential. Successful sampling with CVS can be performed in more than 99% of cases; the rate of cross-contamination is less than 1%.

Is there a risk of miscarriage?

In counseling patients about the risk of fetal death that CVS or amniocentesis may entail, the place to begin is the background loss rate, which is greater in twin than in single gestations. The reported background loss rate of twins at 24 weeks’ gestation or less ranges from 5.8% to 7.2%.20,21 In women of advanced maternal age (35 years and older), a background rate as high as 17.6% has been described.21 Once parents are aware of this, they have a context for weighing the risk of miscarriage that prenatal testing may hold.

The twin loss rate following amniocentesis has been evaluated in several studies. (See “Integrating evidence and experience: Does invasive prenatal testing raise the risk of miscarriage in a twin gestation?”)

A greatly elevated risk of preterm birth

Multiple gestations are at extremely high risk for premature delivery, and—like all premature newborns—these infants are at risk for a wide range of disabilities. Risk factors for premature delivery include history of second trimester pregnancy loss, preterm birth at less than 35 weeks’ gestation, more than 2 previous curettage procedures, cone biopsy, müllerian anomaly, and diethylstilbestrol exposure. Unfortunately, current yardsticks for predicting premature delivery in multiple pregnancy have serious limitations, and available interventions have not been particularly successful.

Predictors

Measurement of cervical length has been evaluated as a predictor of preterm delivery in a number of twin studies that were looking for a cutoff point that can predict which twins are at greatest risk. No such cutoff has been found.22-25

In general, studies demonstrate a low risk of preterm delivery for women who have a cervical length measurement of more than 35 mm at 24 to 26 weeks. A shorter cervical length correlates with premature delivery, but specific cutoffs have proved not to be sensitive predictors.

In the largest published series, To and colleagues evaluated 1,163 sets of twins undergoing routine care with cervical length assessments at 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation. They demonstrated a direct correlation between cervical length and preterm delivery, but were unable to define a cutoff sufficiently sensitive to be useful.25 A shortened cervix may be predictive of prematurity in general, but it does not allow the obstetrician to predict with certainty which mothers will give birth prematurely or how long a particular mother will carry.

Fetal fibronectin. The presence of fetal fibronectin (ffN) in cervicovaginal secretions is widely used as an adjunct to other potential predictors of preterm delivery. In a multistudy review that included symptomatic women, a negative ffN had a 99% negative predictive value but a poor positive predictive value (13% to 30%) for delivery within 7 to 10 days.26

Use of ffN in conjunction with cervical length has also been investigated in twin gestations. Although the negative predictive value of ffN remained high, the addition of ffN to cervical length assessment did not improve the positive predictive value of cervical length alone.27,28

Interventions

Cerclage is often used in high-risk singleton pregnancies in which a shortened cervix is seen on a sonogram. The utility of cerclage in twins is less clear. Randomized controlled trials comparing women at risk of premature delivery treated with cerclage and controls not considered at risk found no difference in the rate of premature delivery in the 2 groups.29,30 Meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials also found no benefit and, in fact, detected a possibility of actual harm. Cerclage twins were more likely to deliver early (at less than 35 weeks’ gestation) and had a 2.6 relative risk of perinatal mortality. The differences found in the meta-analysis were not statistically significant, however, and the overall sample size was small (n=48).31

The best available data seem to show that cerclage based on US indications of cervical shortening is not beneficial and may even be associated with worse outcome.

17-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) has been found to decrease the rate of recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations by almost 35%.32 Although twins are at increased risk of preterm birth, the use of 17P has not, however, been shown to be of benefit.33

Bed rest. A Cochrane Database review of 6 randomized controlled trials compared 1) patients with a multiple gestation who were offered bed rest in the hospital with 2) patients hospitalized for complications of pregnancy. The review found that bed rest did not reduce the risk of preterm birth or of perinatal mortality in the routinely hospitalized women. There was, however, a tendency to a decreased number of low-birth-weight infants born to women given bed rest.34

INTEGRATING EVIDENCE AND EXPERIENCE

The evidence for amniocentesis

Toth-Pal and colleagues compared the twin loss rate after amniocentesis in 155 twin pairs; twins who had a structural anomaly or aneuploidy were excluded. The investigators found a 3.87% loss rate at 24 weeks or less, compared with a background loss rate of 2.39% in twins who did not undergo the procedure—an insignificant difference.1

Yukobowich and colleagues compared 476 diamniotic, dichorionic twin pairs that had undergone amniocentesis with 1) 477 twin pairs undergoing routine US examination and 2) 489 singleton amniocenteses. They found a 4-week postprocedure loss rate of 2.7% in the amniocentesis twins, compared with 0.63% in twin controls who had routine US and 0.6% in the amniocentesis singletons.2 The difference is significant, but the reported loss rate is still less than, or comparable to, the reported background twin loss rate at 24 weeks or less.

Chorionic villus sampling