User login

Functional Assessment in Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis

Androgens in women: To replace or not?

Although women produce only one tenth the amount of androgen that men do, testosterone and related androgen metabolites are as important to women throughout the lifespan as is estrogen. Androgens modulate a feeling of well-being, increase energy, support bone metabolism, and improve sexual function in women.1-3 But too much androgen production, with elevated levels of testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), can result in hirsutism, acne, and infertility in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), all of which present clinical problems.

An equally complicated topic is androgen insufficiency in women. Not only is it difficult to diagnose, it is a major clinical issue to decide whether, when, and how to replace androgens in women. In this article, I look at androgen production throughout the female lifespan, particularly the relationship between estrogen and androgen. I also describe the evaluation of androgen insufficiency, which requires understanding of androgen physiology and ovarian function before and after menopause. These issues form the basis of the decision to replace androgen in women.

Androgen over the lifespan

In the premenopausal woman, androgen production is approximately equally divided between the adrenal gland and the ovaries. Androstenedione from both is converted to testosterone and then irreversibly to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Androstenedione, testosterone, and even DHEA are secreted in equal quantities by the adrenals and ovaries. The only androgen that is predominantly adrenal is DHEAS, which is sulfated in the adrenal gland.

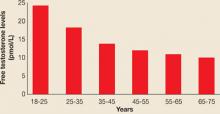

In premenopausal women, androstenedione is the precursor to testosterone, which is then metabolized to DHT, the androgen most active in hair follicles and implicated in hirsutism. It has been clear for many years that DHEA, although a weak androgen, is present in the greatest quantity in the circulation and is secreted during adrenarche, prior to menarche, beginning at ages 8 to 10. DHEAS peaks in young adulthood and begins to decline after age 40.4 The same is true for both total testosterone and free testosterone levels, which also decline in women after about age 25. Thus, peri- and postmenopausal women have approximately half the level of circulating androgens of women in their 20s (FIGURE 1, TABLE 1).5

FIGURE 1

Testosterone levels in women decline with aging

N=595

SOURCE: Davison S, et al5TABLE 1

How menopause affects plasma hormone levels

| HORMONE | MEAN PLASMA LEVEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| REPRODUCTIVE AGE* (N=15) | NATURALLY MENOPAUSAL (N=18) | OOPHORECTOMIZED (N=8) | |

| Estrone (pg/mL) | 58 | 49 | 48 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 40 | 20† | 18 |

| Testosterone (ng/dL) | 44 | 30† | 12‡ |

| DHT (ng/dL) | 30 | 10† | <5‡ |

| Androstenedione (ng/dL) | 166 | 99† | 64‡ |

| DHEA (ng/dL) | 542 | 197† | 126§ |

| DHT=dihydrotestosterone, DHEA=dehydroepiandrosterone | |||

| * Mean value during early follicular phase | |||

| † P<.01 for comparison with reproductive age | |||

| ‡ P<.01 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| § P<.05 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| SOURCE: Vermeulen18 | |||

It matters how menopause happens

Circulating androgen levels are greatly influenced by menopause—how much depends on whether it occurs naturally with the ovaries intact, or by surgical removal of the ovaries. Not only does estradiol diminish significantly in naturally menopausal women, but all androgens do as well. In young oophorectomized women, estrogen levels are similar to levels in naturally menopausal women, but androgen levels—including testosterone, DHT, and androstenedione—are significantly lower than in naturally menopausal women, demonstrating that the circulating levels of androgen after natural menopause are still significantly greater than those in oophorectomized women.6 Thus, the postmenopausal ovary contributes significantly to circulating levels of androgen.

Androgen physiology

Both androgens and estrogens circulate in the bloodstream tightly bound to the protein sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and more loosely bound to albumin. The SHBG-bound fraction is unavailable for biologic activity. Therefore, the amount of SHBG a woman produces is a key determinant of her level of androgen bioactivity. For this reason, it is crucial to measure circulating SHBG.

In a feedback mechanism, SHBG production is regulated by androgen and estrogen levels, with estrogen stimulating SHBG production and testosterone decreasing it.7 In the normal woman, about 65% of testosterone is bound to SHBG and 30% is bound to albumin, leaving only 0.5% to 2% free and bioactively available.8 In postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy, SHBG increases, but the addition of methyltestosterone lowers the overall levels of SHBG, even in the presence of estrogen, increasing the amount of bioavailable testosterone simply by lowering SHBG levels. Postmenopausal replacement with estrogen alone decreases the amount of bioavailable testosterone because of higher SHBG levels.

SHBG is synthesized in the liver, whose metabolism is increased by exposure to steroids. Therefore, oral forms of estrogen replacement, which stimulate the liver because of the “first pass” effect, result in a greater increase in SHBG than do transdermal estrogen preparations.

Elevated androgen levels have both ill and good effects

As I stated earlier, an appropriate level of androgen is optimal for women as well as men. Elevated androgen levels are problematic, in that they are the hallmark of PCOS, usually resulting from increased ovarian production of androgen. This elevation can cause anovulation, infertility, hirsutism, and other androgen-mediated physiologic effects. Androgen is also associated with elevated low-density lipoprotein and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, implying a possible relationship with cardiovascular disease. At the same time, however, elevated testosterone has been correlated with increased bone density in both the hip and the femoral neck.9

It is clear that appropriate androgen secretion, which does not elicit the side effects described above, is best for both the health and well-being of the woman.

How androgen affects female sexual function

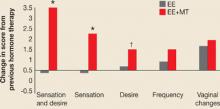

We have known for years that androgen—not estrogen—is associated with satisfactory sexual function. Although estrogen replacement increases vaginal lubrication, it is androgen, most commonly in the form of oral methyltestosterone or injectable testosterone, that increases frequency of intercourse, desire, and sexual sensation (FIGURE 2).10 The definition of androgen insufficiency has been hotly debated, and is currently “a pattern of clinical symptoms in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen.”11

FIGURE 2

How estrogen plus androgen affects sexual function

*P<.01; †P=.05

EE=esterified estrogens; MT=methyltestosterone

SOURCE: Sarrel PM, et al19

Assessing androgen levels

Clinical signs and symptoms of androgen insufficiency are important in establishing the diagnosis. They include a diminished sense of well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning and loss of pubic hair.11 Although it is possible to assess testosterone production and availability in women by measuring serum testosterone levels, a lack of consensus about the best measurement technique and interpretation of results makes it difficult to base the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency solely on serum levels.12 Therefore, the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency is primarily a clinical diagnosis of symptoms.11

Obtain serum samples between 8 and 10 AM after day 8 and before day 20 of the normal menstrual cycle because testosterone is subject to diurnal variation, peaking in the early morning, as well as cyclic variation, peaking around midcycle.

Because free testosterone is the only bioavailable steroid, total testosterone and either free testosterone or SHBG must be measured to assess how much androgen is actually available. From total testosterone and SHBG, one can assess the free testosterone index as a measure of bioavailable androgen (the free testosterone index is a ratio of the amount of total testosterone divided by the SHBG level).11 In fact, using the free testosterone index is preferable to the actual measurement of free testosterone because commercial assays lack the sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of androgen found in women.

Several different testosterone assays exist, and the immunoassay for total testosterone is reasonably accurate. However, measurements of free testosterone are relatively inaccurate and poorly reproducible. Equilibrium dialysis is thought to be the gold standard for measuring free testosterone, but it is a difficult and time-consuming assay.12

Causes of low testosterone

In women, low testosterone secretion is usually the result of normal aging. Other conditions that alter testosterone production include oophorectomy, ovarian failure, adrenal insufficiency, hypopituitarism, and other forms of chronic illness.

Treatment with corticosteroids and estrogen therapy lowers active androgen levels in women.

What levels are cause for concern?

If androgen levels are at or below the 25th percentile of the normal range for reproductive-aged women, consider the possibility of androgen insufficiency and determine whether androgen replacement is in order.11

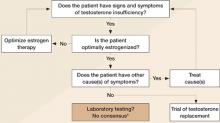

When the signs and symptoms of testosterone insufficiency are present, one must first assess estrogen levels by measuring serum estradiol, obtaining vaginal cytology, or both, and by determining whether symptoms of estrogen insufficiency are present, such as hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness. If the patient is estrogen-insufficient, the first step in resolving her symptoms is estrogen replacement. If estrogen levels are adequate and there is no other reason for the patient’s symptoms of fatigue, lack of sexual desire, or low energy, a trial of testosterone is reasonable.

Treating androgen insufficiency

Current therapies include oral methyltestosterone combined with estrogen, and intramuscular testosterone propionate, testosterone cypionate, and testosterone enanthate. Subcutaneous implants of testosterone propionate are also available, as are transdermal preparations (TABLE 2). However, the transdermal formulations are designed for androgen insufficiency in men, and therefore deliver approximately 10 times as much androgen as women normally produce. Testosterone gel preparations are available that can be applied in lower levels to achieve normal female androgen levels.

TABLE 2

Testosterone therapies available now—or in the pipeline

| Oral |

|

| Intramuscular |

|

| Subcutaneous (implant) |

|

| Transdermal |

|

| Other |

|

How long until relief?

It is clear from a number of studies13,14 that estrogen plus methyltestosterone oral replacement improves sexual desire in women after 12 to 16 weeks, and that this improvement is based on an increase in bioavailable testosterone. A testosterone patch under development delivers 300 μg per day. When used with conjugated equine estrogens, this patch has been shown to increase bioavailable testosterone in women without ovaries who have very low androgen levels.3

In a 2005 study,15 more than 500 women with hypoactive sexual desire who had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were randomized to placebo or a testosterone patch that delivered 300 μg per day for 24 weeks. Not only did serum testosterone levels increase, but satisfying sexual activity and the numbers of sexual interactions and orgasms increased (FIGURE 3). Side effects of therapy included increased facial hair and acne, but there was no increase in serious adverse effects, and no increase in withdrawal from the study because of side effects. Unfortunately, this patch is in development and unavailable commercially in the United States.

FIGURE 3

Assessing testosterone status in women

Adapted from Braunstein GD20

*Bachmann G, et al11

Watch for side effects, and follow closely

Testosterone therapy is most appropriate for women who have undergone surgical menopause and for postmenopausal women who are dissatisfied with estrogen therapy because of symptoms such as decreased libido and a diminished sense of well-being, including headaches and fatigue. Side effects of testosterone therapy include hirsutism, acne, alopecia, worsening lipoproteins, and, in the case of methyltestosterone, the possibility of liver toxicity, so women receiving testosterone should be followed frequently and carefully to detect any of these effects.

Androgen insufficiency in a nutshell

Androgens in women engender a general sense of well-being, which includes elevated energy and mood and increased libido. It is appropriate to consider androgen replacement using oral methyltestosterone, androgen implants, or transdermal androgen gels in women with a clinical diagnosis of androgen insufficiency.

Before initiating androgen therapy, however, it is important to measure total androgen level and assess clinical symptoms. Also, monitor the incidence of side effects to ensure that the patient does not exceed normal female androgen levels. It is hoped that additional forms of androgen replacement for women will become available in the near future.

The role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2005;12:497–511.

In 2005, the North American Menopause Society issued a comprehensive position statement on the role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women. Its purpose was to offer recommendations based on reliable evidence, and it reflects a thorough analysis of the data to date. Note that its findings, highlighted below, pertain to postmenopausal women only.

1. Endogenous testosterone levels have no clear link to sexual function

No definitive studies have established a relationship between endogenous testosterone levels and sexual function, and observational data have been mixed. Because of this lack of clarity, we do not have specific total or free testosterone values that indicate clinical testosterone deficiency.

Exogenous testosterone is a different story. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated greater sexual desire and sexual responsiveness and more frequent sexual activity when exogenous testosterone is given. Almost all trials involved testosterone combined with estrogen or estrogen–progestogen therapy. The only trial that included a testosterone-alone arm found that testosterone added to estrogen therapy or given alone increased sexual desire, arousal, and frequency of sexual fantasies, compared with placebo or estrogen alone.14

2. Use the free testosterone index to determine testosterone bioavailability

Only 1% to 2% of circulating testosterone is free or bioavailable. The remainder binds tightly to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG, about 65%) or loosely to albumin (~30%). Because oral estrogen therapy increases SHBG levels, it lowers unbound testosterone. Conversely, obesity and hypothyroidism depress SHBG levels and increase free testosterone.

The simplest method to determine the amount of bioavailable testosterone is to measure total testosterone and SHBG, dividing total testosterone (ng/dL) by SHBG (nmol/L). Multiply this figure by 3.47 to obtain the free testosterone index. If the total testosterone value is reported in nmol/L, the multiplication factor is 100.

During the menopausal transition, free testosterone concentrations appear to remain fairly constant or increase slightly, probably because SHBG declines as ovarian estrogen production diminishes. One small study found little difference in total testosterone between younger premenopausal women (age 19–37 years) and older women (age 43–47), although the older age group lacked the midcycle rise in free testosterone and androstenedione.16

3. Causes of androgen insufficiency: Chronic illness, age, and oophorectomy, to name a few

Bilateral oophorectomy can lower testosterone levels by as much as 50%. Other contributors include increasing age, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal insufficiency, systemic glucocorticoids, hyperthyroidism and excessive thyroid medication, and chronic illness such as depression and advanced cancer. Both endogenous and exogenous estrogens lower testosterone levels by raising SHBG.

4. Sexual dysfunction is the only indication

Thus far, we lack sufficient data to justify use of testosterone for any other indication, including preserving bone mineral density, reducing hot flashes, and improving the patient’s overall sense of well-being.

5. A comprehensive clinical exam is mandatory

This includes a psychosexual and psychosocial history; a thorough medical history, including use of prescription and other drugs (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which can reduce sexual desire); and a physical exam. It may also be appropriate to measure thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin and get a complete blood cell count. Consider the effects of other physical, psychological, and emotional complaints on sexual function, and ask about the relationship itself.

A study from Australia17 concluded that a postmenopausal woman’s previous level of sexual function, her feelings toward her partner, any change in partner status, and estradiol levels have the greatest influence on her sexual interest, arousal, and enjoyment. Declining levels of estradiol at menopause have a smaller impact than these psychological factors.

6. Non-oral forms of testosterone are preferred

To avoid the first-pass hepatic effects of oral administration, prescribe transdermal patches and topical gels and creams whenever possible, rather than oral testosterone.

Oral testosterone in combination with oral estrogen reduces high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides in postmenopausal women, but non-oral testosterone has no significant effect on these parameters.

Extended use of high doses of oral testosterone can cause liver dysfunction in women.

7. Impact on fracture risk is unclear

Adding testosterone to estrogen therapy increases bone mineral density or reduces bone turnover, but no randomized trial has reported its effects on fracture risk in postmenopausal women.

8. No testosterone product is FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women

However, a few testosterone-containing prescription products are approved for use by women and men; some of these are used “off-label” to treat diminished sexual desire in women.

Be wary of custom-compounded prescription formulations because they do not undergo the same rigorous quality control as FDA-approved products.

A number of testosterone products are under development specifically for female sexual desire disorders, including an oral product, a cream, gels, a patch, a spray, and a vaginal ring.

9. Avoid testosterone in cancer and in heart and liver disease

Testosterone therapy is contraindicated in patients who have cancer of the breast or uterus, or cardiovascular or liver disease.

10. As with estrogen, use the lowest dosage for the shortest time possible

Once therapy meets treatment goals, it should be curtailed, if possible. And the dose should be kept as low as possible.

Most trials of testosterone therapy lasted 6 months or less, so we lack long-term data on safety and efficacy.

11. Supraphysiologic levels can cause adverse effects, some of them permanent

Risks include lowering of the voice (which may be permanent), enlargement of the clitoris, excess body hair, erythrocytosis, edema, and liver dysfunction. Psychological effects are also possible.

1. Sherwin BB. Hormones, mood, and cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:20S-26S.

2. Raisz LG, Wiita B, Artis A, et al. Comparison of the effects of estrogen alone and estrogen plus androgen on biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:37-43.

3. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

4. Buster JE, et al. In: Lobo RA, ed. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:142.

5. Davison S, et al. Testosterone levels in women decline with aging. Abstract presented at the Endocrine Society Annual Meeting, held June 16–19, 2004, New Orleans.

6. Hughes CL, Jr, Wall LL, Creasman WT. Reproductive hormone levels in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing surgical castration after spontaneous menopause. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:42-45.

7. Selby C. Sex hormone-binding globulin. Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:532-541.

8. Simon JA. Estrogen replacement therapy: effects on the endogenous androgen milieu. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S77-S82.

9. Miller KK, Biller BM, Hier J, Arena E, Klibanski A. Androgens and bone density in women with hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2770-2776.

10. Sarrel PM. Broadened spectrum of menopausal symptom relief. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:734-740.

11. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

12. Guay AT. Screening for androgen deficiency in women: methodological and interpretive issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S83-S88.

13. Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, Block B, Van Der Hoop RG. Comparative effects of oral and esterified estrogens with or without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles on dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

14. Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

15. Buster JE, Kingsberg SA, Aguirre O, et al. Testosterone patch for low sexual desire in surgically menopausal women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:938-940.

16. Mushayandebvu T, Castracane VD, Gimpel T, Adel T, Santoro N. Evidence for diminished midcycle ovarian androgen production in older reproductive aged women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:721-723.

17. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

18. Vermeulen A. The hormonal activity of the postmenopausal ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:247-253.

19. Sarrel P, Dobay B, Wiita B. Estrogen and estrogen–androgen replacement in postmenopausal women dissatisfied with estrogen-only therapy. Sexual behavior and neuroendocrine responses. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:847-856.

20. Braunstein GD. Androgen insufficiency in women: summary of critical issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(suppl 4):S94-S99.

Although women produce only one tenth the amount of androgen that men do, testosterone and related androgen metabolites are as important to women throughout the lifespan as is estrogen. Androgens modulate a feeling of well-being, increase energy, support bone metabolism, and improve sexual function in women.1-3 But too much androgen production, with elevated levels of testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), can result in hirsutism, acne, and infertility in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), all of which present clinical problems.

An equally complicated topic is androgen insufficiency in women. Not only is it difficult to diagnose, it is a major clinical issue to decide whether, when, and how to replace androgens in women. In this article, I look at androgen production throughout the female lifespan, particularly the relationship between estrogen and androgen. I also describe the evaluation of androgen insufficiency, which requires understanding of androgen physiology and ovarian function before and after menopause. These issues form the basis of the decision to replace androgen in women.

Androgen over the lifespan

In the premenopausal woman, androgen production is approximately equally divided between the adrenal gland and the ovaries. Androstenedione from both is converted to testosterone and then irreversibly to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Androstenedione, testosterone, and even DHEA are secreted in equal quantities by the adrenals and ovaries. The only androgen that is predominantly adrenal is DHEAS, which is sulfated in the adrenal gland.

In premenopausal women, androstenedione is the precursor to testosterone, which is then metabolized to DHT, the androgen most active in hair follicles and implicated in hirsutism. It has been clear for many years that DHEA, although a weak androgen, is present in the greatest quantity in the circulation and is secreted during adrenarche, prior to menarche, beginning at ages 8 to 10. DHEAS peaks in young adulthood and begins to decline after age 40.4 The same is true for both total testosterone and free testosterone levels, which also decline in women after about age 25. Thus, peri- and postmenopausal women have approximately half the level of circulating androgens of women in their 20s (FIGURE 1, TABLE 1).5

FIGURE 1

Testosterone levels in women decline with aging

N=595

SOURCE: Davison S, et al5TABLE 1

How menopause affects plasma hormone levels

| HORMONE | MEAN PLASMA LEVEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| REPRODUCTIVE AGE* (N=15) | NATURALLY MENOPAUSAL (N=18) | OOPHORECTOMIZED (N=8) | |

| Estrone (pg/mL) | 58 | 49 | 48 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 40 | 20† | 18 |

| Testosterone (ng/dL) | 44 | 30† | 12‡ |

| DHT (ng/dL) | 30 | 10† | <5‡ |

| Androstenedione (ng/dL) | 166 | 99† | 64‡ |

| DHEA (ng/dL) | 542 | 197† | 126§ |

| DHT=dihydrotestosterone, DHEA=dehydroepiandrosterone | |||

| * Mean value during early follicular phase | |||

| † P<.01 for comparison with reproductive age | |||

| ‡ P<.01 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| § P<.05 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| SOURCE: Vermeulen18 | |||

It matters how menopause happens

Circulating androgen levels are greatly influenced by menopause—how much depends on whether it occurs naturally with the ovaries intact, or by surgical removal of the ovaries. Not only does estradiol diminish significantly in naturally menopausal women, but all androgens do as well. In young oophorectomized women, estrogen levels are similar to levels in naturally menopausal women, but androgen levels—including testosterone, DHT, and androstenedione—are significantly lower than in naturally menopausal women, demonstrating that the circulating levels of androgen after natural menopause are still significantly greater than those in oophorectomized women.6 Thus, the postmenopausal ovary contributes significantly to circulating levels of androgen.

Androgen physiology

Both androgens and estrogens circulate in the bloodstream tightly bound to the protein sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and more loosely bound to albumin. The SHBG-bound fraction is unavailable for biologic activity. Therefore, the amount of SHBG a woman produces is a key determinant of her level of androgen bioactivity. For this reason, it is crucial to measure circulating SHBG.

In a feedback mechanism, SHBG production is regulated by androgen and estrogen levels, with estrogen stimulating SHBG production and testosterone decreasing it.7 In the normal woman, about 65% of testosterone is bound to SHBG and 30% is bound to albumin, leaving only 0.5% to 2% free and bioactively available.8 In postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy, SHBG increases, but the addition of methyltestosterone lowers the overall levels of SHBG, even in the presence of estrogen, increasing the amount of bioavailable testosterone simply by lowering SHBG levels. Postmenopausal replacement with estrogen alone decreases the amount of bioavailable testosterone because of higher SHBG levels.

SHBG is synthesized in the liver, whose metabolism is increased by exposure to steroids. Therefore, oral forms of estrogen replacement, which stimulate the liver because of the “first pass” effect, result in a greater increase in SHBG than do transdermal estrogen preparations.

Elevated androgen levels have both ill and good effects

As I stated earlier, an appropriate level of androgen is optimal for women as well as men. Elevated androgen levels are problematic, in that they are the hallmark of PCOS, usually resulting from increased ovarian production of androgen. This elevation can cause anovulation, infertility, hirsutism, and other androgen-mediated physiologic effects. Androgen is also associated with elevated low-density lipoprotein and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, implying a possible relationship with cardiovascular disease. At the same time, however, elevated testosterone has been correlated with increased bone density in both the hip and the femoral neck.9

It is clear that appropriate androgen secretion, which does not elicit the side effects described above, is best for both the health and well-being of the woman.

How androgen affects female sexual function

We have known for years that androgen—not estrogen—is associated with satisfactory sexual function. Although estrogen replacement increases vaginal lubrication, it is androgen, most commonly in the form of oral methyltestosterone or injectable testosterone, that increases frequency of intercourse, desire, and sexual sensation (FIGURE 2).10 The definition of androgen insufficiency has been hotly debated, and is currently “a pattern of clinical symptoms in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen.”11

FIGURE 2

How estrogen plus androgen affects sexual function

*P<.01; †P=.05

EE=esterified estrogens; MT=methyltestosterone

SOURCE: Sarrel PM, et al19

Assessing androgen levels

Clinical signs and symptoms of androgen insufficiency are important in establishing the diagnosis. They include a diminished sense of well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning and loss of pubic hair.11 Although it is possible to assess testosterone production and availability in women by measuring serum testosterone levels, a lack of consensus about the best measurement technique and interpretation of results makes it difficult to base the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency solely on serum levels.12 Therefore, the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency is primarily a clinical diagnosis of symptoms.11

Obtain serum samples between 8 and 10 AM after day 8 and before day 20 of the normal menstrual cycle because testosterone is subject to diurnal variation, peaking in the early morning, as well as cyclic variation, peaking around midcycle.

Because free testosterone is the only bioavailable steroid, total testosterone and either free testosterone or SHBG must be measured to assess how much androgen is actually available. From total testosterone and SHBG, one can assess the free testosterone index as a measure of bioavailable androgen (the free testosterone index is a ratio of the amount of total testosterone divided by the SHBG level).11 In fact, using the free testosterone index is preferable to the actual measurement of free testosterone because commercial assays lack the sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of androgen found in women.

Several different testosterone assays exist, and the immunoassay for total testosterone is reasonably accurate. However, measurements of free testosterone are relatively inaccurate and poorly reproducible. Equilibrium dialysis is thought to be the gold standard for measuring free testosterone, but it is a difficult and time-consuming assay.12

Causes of low testosterone

In women, low testosterone secretion is usually the result of normal aging. Other conditions that alter testosterone production include oophorectomy, ovarian failure, adrenal insufficiency, hypopituitarism, and other forms of chronic illness.

Treatment with corticosteroids and estrogen therapy lowers active androgen levels in women.

What levels are cause for concern?

If androgen levels are at or below the 25th percentile of the normal range for reproductive-aged women, consider the possibility of androgen insufficiency and determine whether androgen replacement is in order.11

When the signs and symptoms of testosterone insufficiency are present, one must first assess estrogen levels by measuring serum estradiol, obtaining vaginal cytology, or both, and by determining whether symptoms of estrogen insufficiency are present, such as hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness. If the patient is estrogen-insufficient, the first step in resolving her symptoms is estrogen replacement. If estrogen levels are adequate and there is no other reason for the patient’s symptoms of fatigue, lack of sexual desire, or low energy, a trial of testosterone is reasonable.

Treating androgen insufficiency

Current therapies include oral methyltestosterone combined with estrogen, and intramuscular testosterone propionate, testosterone cypionate, and testosterone enanthate. Subcutaneous implants of testosterone propionate are also available, as are transdermal preparations (TABLE 2). However, the transdermal formulations are designed for androgen insufficiency in men, and therefore deliver approximately 10 times as much androgen as women normally produce. Testosterone gel preparations are available that can be applied in lower levels to achieve normal female androgen levels.

TABLE 2

Testosterone therapies available now—or in the pipeline

| Oral |

|

| Intramuscular |

|

| Subcutaneous (implant) |

|

| Transdermal |

|

| Other |

|

How long until relief?

It is clear from a number of studies13,14 that estrogen plus methyltestosterone oral replacement improves sexual desire in women after 12 to 16 weeks, and that this improvement is based on an increase in bioavailable testosterone. A testosterone patch under development delivers 300 μg per day. When used with conjugated equine estrogens, this patch has been shown to increase bioavailable testosterone in women without ovaries who have very low androgen levels.3

In a 2005 study,15 more than 500 women with hypoactive sexual desire who had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were randomized to placebo or a testosterone patch that delivered 300 μg per day for 24 weeks. Not only did serum testosterone levels increase, but satisfying sexual activity and the numbers of sexual interactions and orgasms increased (FIGURE 3). Side effects of therapy included increased facial hair and acne, but there was no increase in serious adverse effects, and no increase in withdrawal from the study because of side effects. Unfortunately, this patch is in development and unavailable commercially in the United States.

FIGURE 3

Assessing testosterone status in women

Adapted from Braunstein GD20

*Bachmann G, et al11

Watch for side effects, and follow closely

Testosterone therapy is most appropriate for women who have undergone surgical menopause and for postmenopausal women who are dissatisfied with estrogen therapy because of symptoms such as decreased libido and a diminished sense of well-being, including headaches and fatigue. Side effects of testosterone therapy include hirsutism, acne, alopecia, worsening lipoproteins, and, in the case of methyltestosterone, the possibility of liver toxicity, so women receiving testosterone should be followed frequently and carefully to detect any of these effects.

Androgen insufficiency in a nutshell

Androgens in women engender a general sense of well-being, which includes elevated energy and mood and increased libido. It is appropriate to consider androgen replacement using oral methyltestosterone, androgen implants, or transdermal androgen gels in women with a clinical diagnosis of androgen insufficiency.

Before initiating androgen therapy, however, it is important to measure total androgen level and assess clinical symptoms. Also, monitor the incidence of side effects to ensure that the patient does not exceed normal female androgen levels. It is hoped that additional forms of androgen replacement for women will become available in the near future.

The role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2005;12:497–511.

In 2005, the North American Menopause Society issued a comprehensive position statement on the role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women. Its purpose was to offer recommendations based on reliable evidence, and it reflects a thorough analysis of the data to date. Note that its findings, highlighted below, pertain to postmenopausal women only.

1. Endogenous testosterone levels have no clear link to sexual function

No definitive studies have established a relationship between endogenous testosterone levels and sexual function, and observational data have been mixed. Because of this lack of clarity, we do not have specific total or free testosterone values that indicate clinical testosterone deficiency.

Exogenous testosterone is a different story. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated greater sexual desire and sexual responsiveness and more frequent sexual activity when exogenous testosterone is given. Almost all trials involved testosterone combined with estrogen or estrogen–progestogen therapy. The only trial that included a testosterone-alone arm found that testosterone added to estrogen therapy or given alone increased sexual desire, arousal, and frequency of sexual fantasies, compared with placebo or estrogen alone.14

2. Use the free testosterone index to determine testosterone bioavailability

Only 1% to 2% of circulating testosterone is free or bioavailable. The remainder binds tightly to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG, about 65%) or loosely to albumin (~30%). Because oral estrogen therapy increases SHBG levels, it lowers unbound testosterone. Conversely, obesity and hypothyroidism depress SHBG levels and increase free testosterone.

The simplest method to determine the amount of bioavailable testosterone is to measure total testosterone and SHBG, dividing total testosterone (ng/dL) by SHBG (nmol/L). Multiply this figure by 3.47 to obtain the free testosterone index. If the total testosterone value is reported in nmol/L, the multiplication factor is 100.

During the menopausal transition, free testosterone concentrations appear to remain fairly constant or increase slightly, probably because SHBG declines as ovarian estrogen production diminishes. One small study found little difference in total testosterone between younger premenopausal women (age 19–37 years) and older women (age 43–47), although the older age group lacked the midcycle rise in free testosterone and androstenedione.16

3. Causes of androgen insufficiency: Chronic illness, age, and oophorectomy, to name a few

Bilateral oophorectomy can lower testosterone levels by as much as 50%. Other contributors include increasing age, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal insufficiency, systemic glucocorticoids, hyperthyroidism and excessive thyroid medication, and chronic illness such as depression and advanced cancer. Both endogenous and exogenous estrogens lower testosterone levels by raising SHBG.

4. Sexual dysfunction is the only indication

Thus far, we lack sufficient data to justify use of testosterone for any other indication, including preserving bone mineral density, reducing hot flashes, and improving the patient’s overall sense of well-being.

5. A comprehensive clinical exam is mandatory

This includes a psychosexual and psychosocial history; a thorough medical history, including use of prescription and other drugs (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which can reduce sexual desire); and a physical exam. It may also be appropriate to measure thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin and get a complete blood cell count. Consider the effects of other physical, psychological, and emotional complaints on sexual function, and ask about the relationship itself.

A study from Australia17 concluded that a postmenopausal woman’s previous level of sexual function, her feelings toward her partner, any change in partner status, and estradiol levels have the greatest influence on her sexual interest, arousal, and enjoyment. Declining levels of estradiol at menopause have a smaller impact than these psychological factors.

6. Non-oral forms of testosterone are preferred

To avoid the first-pass hepatic effects of oral administration, prescribe transdermal patches and topical gels and creams whenever possible, rather than oral testosterone.

Oral testosterone in combination with oral estrogen reduces high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides in postmenopausal women, but non-oral testosterone has no significant effect on these parameters.

Extended use of high doses of oral testosterone can cause liver dysfunction in women.

7. Impact on fracture risk is unclear

Adding testosterone to estrogen therapy increases bone mineral density or reduces bone turnover, but no randomized trial has reported its effects on fracture risk in postmenopausal women.

8. No testosterone product is FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women

However, a few testosterone-containing prescription products are approved for use by women and men; some of these are used “off-label” to treat diminished sexual desire in women.

Be wary of custom-compounded prescription formulations because they do not undergo the same rigorous quality control as FDA-approved products.

A number of testosterone products are under development specifically for female sexual desire disorders, including an oral product, a cream, gels, a patch, a spray, and a vaginal ring.

9. Avoid testosterone in cancer and in heart and liver disease

Testosterone therapy is contraindicated in patients who have cancer of the breast or uterus, or cardiovascular or liver disease.

10. As with estrogen, use the lowest dosage for the shortest time possible

Once therapy meets treatment goals, it should be curtailed, if possible. And the dose should be kept as low as possible.

Most trials of testosterone therapy lasted 6 months or less, so we lack long-term data on safety and efficacy.

11. Supraphysiologic levels can cause adverse effects, some of them permanent

Risks include lowering of the voice (which may be permanent), enlargement of the clitoris, excess body hair, erythrocytosis, edema, and liver dysfunction. Psychological effects are also possible.

Although women produce only one tenth the amount of androgen that men do, testosterone and related androgen metabolites are as important to women throughout the lifespan as is estrogen. Androgens modulate a feeling of well-being, increase energy, support bone metabolism, and improve sexual function in women.1-3 But too much androgen production, with elevated levels of testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), can result in hirsutism, acne, and infertility in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), all of which present clinical problems.

An equally complicated topic is androgen insufficiency in women. Not only is it difficult to diagnose, it is a major clinical issue to decide whether, when, and how to replace androgens in women. In this article, I look at androgen production throughout the female lifespan, particularly the relationship between estrogen and androgen. I also describe the evaluation of androgen insufficiency, which requires understanding of androgen physiology and ovarian function before and after menopause. These issues form the basis of the decision to replace androgen in women.

Androgen over the lifespan

In the premenopausal woman, androgen production is approximately equally divided between the adrenal gland and the ovaries. Androstenedione from both is converted to testosterone and then irreversibly to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Androstenedione, testosterone, and even DHEA are secreted in equal quantities by the adrenals and ovaries. The only androgen that is predominantly adrenal is DHEAS, which is sulfated in the adrenal gland.

In premenopausal women, androstenedione is the precursor to testosterone, which is then metabolized to DHT, the androgen most active in hair follicles and implicated in hirsutism. It has been clear for many years that DHEA, although a weak androgen, is present in the greatest quantity in the circulation and is secreted during adrenarche, prior to menarche, beginning at ages 8 to 10. DHEAS peaks in young adulthood and begins to decline after age 40.4 The same is true for both total testosterone and free testosterone levels, which also decline in women after about age 25. Thus, peri- and postmenopausal women have approximately half the level of circulating androgens of women in their 20s (FIGURE 1, TABLE 1).5

FIGURE 1

Testosterone levels in women decline with aging

N=595

SOURCE: Davison S, et al5TABLE 1

How menopause affects plasma hormone levels

| HORMONE | MEAN PLASMA LEVEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| REPRODUCTIVE AGE* (N=15) | NATURALLY MENOPAUSAL (N=18) | OOPHORECTOMIZED (N=8) | |

| Estrone (pg/mL) | 58 | 49 | 48 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 40 | 20† | 18 |

| Testosterone (ng/dL) | 44 | 30† | 12‡ |

| DHT (ng/dL) | 30 | 10† | <5‡ |

| Androstenedione (ng/dL) | 166 | 99† | 64‡ |

| DHEA (ng/dL) | 542 | 197† | 126§ |

| DHT=dihydrotestosterone, DHEA=dehydroepiandrosterone | |||

| * Mean value during early follicular phase | |||

| † P<.01 for comparison with reproductive age | |||

| ‡ P<.01 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| § P<.05 for comparison with naturally menopausal women | |||

| SOURCE: Vermeulen18 | |||

It matters how menopause happens

Circulating androgen levels are greatly influenced by menopause—how much depends on whether it occurs naturally with the ovaries intact, or by surgical removal of the ovaries. Not only does estradiol diminish significantly in naturally menopausal women, but all androgens do as well. In young oophorectomized women, estrogen levels are similar to levels in naturally menopausal women, but androgen levels—including testosterone, DHT, and androstenedione—are significantly lower than in naturally menopausal women, demonstrating that the circulating levels of androgen after natural menopause are still significantly greater than those in oophorectomized women.6 Thus, the postmenopausal ovary contributes significantly to circulating levels of androgen.

Androgen physiology

Both androgens and estrogens circulate in the bloodstream tightly bound to the protein sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and more loosely bound to albumin. The SHBG-bound fraction is unavailable for biologic activity. Therefore, the amount of SHBG a woman produces is a key determinant of her level of androgen bioactivity. For this reason, it is crucial to measure circulating SHBG.

In a feedback mechanism, SHBG production is regulated by androgen and estrogen levels, with estrogen stimulating SHBG production and testosterone decreasing it.7 In the normal woman, about 65% of testosterone is bound to SHBG and 30% is bound to albumin, leaving only 0.5% to 2% free and bioactively available.8 In postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy, SHBG increases, but the addition of methyltestosterone lowers the overall levels of SHBG, even in the presence of estrogen, increasing the amount of bioavailable testosterone simply by lowering SHBG levels. Postmenopausal replacement with estrogen alone decreases the amount of bioavailable testosterone because of higher SHBG levels.

SHBG is synthesized in the liver, whose metabolism is increased by exposure to steroids. Therefore, oral forms of estrogen replacement, which stimulate the liver because of the “first pass” effect, result in a greater increase in SHBG than do transdermal estrogen preparations.

Elevated androgen levels have both ill and good effects

As I stated earlier, an appropriate level of androgen is optimal for women as well as men. Elevated androgen levels are problematic, in that they are the hallmark of PCOS, usually resulting from increased ovarian production of androgen. This elevation can cause anovulation, infertility, hirsutism, and other androgen-mediated physiologic effects. Androgen is also associated with elevated low-density lipoprotein and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, implying a possible relationship with cardiovascular disease. At the same time, however, elevated testosterone has been correlated with increased bone density in both the hip and the femoral neck.9

It is clear that appropriate androgen secretion, which does not elicit the side effects described above, is best for both the health and well-being of the woman.

How androgen affects female sexual function

We have known for years that androgen—not estrogen—is associated with satisfactory sexual function. Although estrogen replacement increases vaginal lubrication, it is androgen, most commonly in the form of oral methyltestosterone or injectable testosterone, that increases frequency of intercourse, desire, and sexual sensation (FIGURE 2).10 The definition of androgen insufficiency has been hotly debated, and is currently “a pattern of clinical symptoms in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen.”11

FIGURE 2

How estrogen plus androgen affects sexual function

*P<.01; †P=.05

EE=esterified estrogens; MT=methyltestosterone

SOURCE: Sarrel PM, et al19

Assessing androgen levels

Clinical signs and symptoms of androgen insufficiency are important in establishing the diagnosis. They include a diminished sense of well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning and loss of pubic hair.11 Although it is possible to assess testosterone production and availability in women by measuring serum testosterone levels, a lack of consensus about the best measurement technique and interpretation of results makes it difficult to base the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency solely on serum levels.12 Therefore, the diagnosis of androgen insufficiency is primarily a clinical diagnosis of symptoms.11

Obtain serum samples between 8 and 10 AM after day 8 and before day 20 of the normal menstrual cycle because testosterone is subject to diurnal variation, peaking in the early morning, as well as cyclic variation, peaking around midcycle.

Because free testosterone is the only bioavailable steroid, total testosterone and either free testosterone or SHBG must be measured to assess how much androgen is actually available. From total testosterone and SHBG, one can assess the free testosterone index as a measure of bioavailable androgen (the free testosterone index is a ratio of the amount of total testosterone divided by the SHBG level).11 In fact, using the free testosterone index is preferable to the actual measurement of free testosterone because commercial assays lack the sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of androgen found in women.

Several different testosterone assays exist, and the immunoassay for total testosterone is reasonably accurate. However, measurements of free testosterone are relatively inaccurate and poorly reproducible. Equilibrium dialysis is thought to be the gold standard for measuring free testosterone, but it is a difficult and time-consuming assay.12

Causes of low testosterone

In women, low testosterone secretion is usually the result of normal aging. Other conditions that alter testosterone production include oophorectomy, ovarian failure, adrenal insufficiency, hypopituitarism, and other forms of chronic illness.

Treatment with corticosteroids and estrogen therapy lowers active androgen levels in women.

What levels are cause for concern?

If androgen levels are at or below the 25th percentile of the normal range for reproductive-aged women, consider the possibility of androgen insufficiency and determine whether androgen replacement is in order.11

When the signs and symptoms of testosterone insufficiency are present, one must first assess estrogen levels by measuring serum estradiol, obtaining vaginal cytology, or both, and by determining whether symptoms of estrogen insufficiency are present, such as hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness. If the patient is estrogen-insufficient, the first step in resolving her symptoms is estrogen replacement. If estrogen levels are adequate and there is no other reason for the patient’s symptoms of fatigue, lack of sexual desire, or low energy, a trial of testosterone is reasonable.

Treating androgen insufficiency

Current therapies include oral methyltestosterone combined with estrogen, and intramuscular testosterone propionate, testosterone cypionate, and testosterone enanthate. Subcutaneous implants of testosterone propionate are also available, as are transdermal preparations (TABLE 2). However, the transdermal formulations are designed for androgen insufficiency in men, and therefore deliver approximately 10 times as much androgen as women normally produce. Testosterone gel preparations are available that can be applied in lower levels to achieve normal female androgen levels.

TABLE 2

Testosterone therapies available now—or in the pipeline

| Oral |

|

| Intramuscular |

|

| Subcutaneous (implant) |

|

| Transdermal |

|

| Other |

|

How long until relief?

It is clear from a number of studies13,14 that estrogen plus methyltestosterone oral replacement improves sexual desire in women after 12 to 16 weeks, and that this improvement is based on an increase in bioavailable testosterone. A testosterone patch under development delivers 300 μg per day. When used with conjugated equine estrogens, this patch has been shown to increase bioavailable testosterone in women without ovaries who have very low androgen levels.3

In a 2005 study,15 more than 500 women with hypoactive sexual desire who had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were randomized to placebo or a testosterone patch that delivered 300 μg per day for 24 weeks. Not only did serum testosterone levels increase, but satisfying sexual activity and the numbers of sexual interactions and orgasms increased (FIGURE 3). Side effects of therapy included increased facial hair and acne, but there was no increase in serious adverse effects, and no increase in withdrawal from the study because of side effects. Unfortunately, this patch is in development and unavailable commercially in the United States.

FIGURE 3

Assessing testosterone status in women

Adapted from Braunstein GD20

*Bachmann G, et al11

Watch for side effects, and follow closely

Testosterone therapy is most appropriate for women who have undergone surgical menopause and for postmenopausal women who are dissatisfied with estrogen therapy because of symptoms such as decreased libido and a diminished sense of well-being, including headaches and fatigue. Side effects of testosterone therapy include hirsutism, acne, alopecia, worsening lipoproteins, and, in the case of methyltestosterone, the possibility of liver toxicity, so women receiving testosterone should be followed frequently and carefully to detect any of these effects.

Androgen insufficiency in a nutshell

Androgens in women engender a general sense of well-being, which includes elevated energy and mood and increased libido. It is appropriate to consider androgen replacement using oral methyltestosterone, androgen implants, or transdermal androgen gels in women with a clinical diagnosis of androgen insufficiency.

Before initiating androgen therapy, however, it is important to measure total androgen level and assess clinical symptoms. Also, monitor the incidence of side effects to ensure that the patient does not exceed normal female androgen levels. It is hoped that additional forms of androgen replacement for women will become available in the near future.

The role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2005;12:497–511.

In 2005, the North American Menopause Society issued a comprehensive position statement on the role of testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women. Its purpose was to offer recommendations based on reliable evidence, and it reflects a thorough analysis of the data to date. Note that its findings, highlighted below, pertain to postmenopausal women only.

1. Endogenous testosterone levels have no clear link to sexual function

No definitive studies have established a relationship between endogenous testosterone levels and sexual function, and observational data have been mixed. Because of this lack of clarity, we do not have specific total or free testosterone values that indicate clinical testosterone deficiency.

Exogenous testosterone is a different story. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated greater sexual desire and sexual responsiveness and more frequent sexual activity when exogenous testosterone is given. Almost all trials involved testosterone combined with estrogen or estrogen–progestogen therapy. The only trial that included a testosterone-alone arm found that testosterone added to estrogen therapy or given alone increased sexual desire, arousal, and frequency of sexual fantasies, compared with placebo or estrogen alone.14

2. Use the free testosterone index to determine testosterone bioavailability

Only 1% to 2% of circulating testosterone is free or bioavailable. The remainder binds tightly to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG, about 65%) or loosely to albumin (~30%). Because oral estrogen therapy increases SHBG levels, it lowers unbound testosterone. Conversely, obesity and hypothyroidism depress SHBG levels and increase free testosterone.

The simplest method to determine the amount of bioavailable testosterone is to measure total testosterone and SHBG, dividing total testosterone (ng/dL) by SHBG (nmol/L). Multiply this figure by 3.47 to obtain the free testosterone index. If the total testosterone value is reported in nmol/L, the multiplication factor is 100.

During the menopausal transition, free testosterone concentrations appear to remain fairly constant or increase slightly, probably because SHBG declines as ovarian estrogen production diminishes. One small study found little difference in total testosterone between younger premenopausal women (age 19–37 years) and older women (age 43–47), although the older age group lacked the midcycle rise in free testosterone and androstenedione.16

3. Causes of androgen insufficiency: Chronic illness, age, and oophorectomy, to name a few

Bilateral oophorectomy can lower testosterone levels by as much as 50%. Other contributors include increasing age, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal insufficiency, systemic glucocorticoids, hyperthyroidism and excessive thyroid medication, and chronic illness such as depression and advanced cancer. Both endogenous and exogenous estrogens lower testosterone levels by raising SHBG.

4. Sexual dysfunction is the only indication

Thus far, we lack sufficient data to justify use of testosterone for any other indication, including preserving bone mineral density, reducing hot flashes, and improving the patient’s overall sense of well-being.

5. A comprehensive clinical exam is mandatory

This includes a psychosexual and psychosocial history; a thorough medical history, including use of prescription and other drugs (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which can reduce sexual desire); and a physical exam. It may also be appropriate to measure thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin and get a complete blood cell count. Consider the effects of other physical, psychological, and emotional complaints on sexual function, and ask about the relationship itself.

A study from Australia17 concluded that a postmenopausal woman’s previous level of sexual function, her feelings toward her partner, any change in partner status, and estradiol levels have the greatest influence on her sexual interest, arousal, and enjoyment. Declining levels of estradiol at menopause have a smaller impact than these psychological factors.

6. Non-oral forms of testosterone are preferred

To avoid the first-pass hepatic effects of oral administration, prescribe transdermal patches and topical gels and creams whenever possible, rather than oral testosterone.

Oral testosterone in combination with oral estrogen reduces high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides in postmenopausal women, but non-oral testosterone has no significant effect on these parameters.

Extended use of high doses of oral testosterone can cause liver dysfunction in women.

7. Impact on fracture risk is unclear

Adding testosterone to estrogen therapy increases bone mineral density or reduces bone turnover, but no randomized trial has reported its effects on fracture risk in postmenopausal women.

8. No testosterone product is FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women

However, a few testosterone-containing prescription products are approved for use by women and men; some of these are used “off-label” to treat diminished sexual desire in women.

Be wary of custom-compounded prescription formulations because they do not undergo the same rigorous quality control as FDA-approved products.

A number of testosterone products are under development specifically for female sexual desire disorders, including an oral product, a cream, gels, a patch, a spray, and a vaginal ring.

9. Avoid testosterone in cancer and in heart and liver disease

Testosterone therapy is contraindicated in patients who have cancer of the breast or uterus, or cardiovascular or liver disease.

10. As with estrogen, use the lowest dosage for the shortest time possible

Once therapy meets treatment goals, it should be curtailed, if possible. And the dose should be kept as low as possible.

Most trials of testosterone therapy lasted 6 months or less, so we lack long-term data on safety and efficacy.

11. Supraphysiologic levels can cause adverse effects, some of them permanent

Risks include lowering of the voice (which may be permanent), enlargement of the clitoris, excess body hair, erythrocytosis, edema, and liver dysfunction. Psychological effects are also possible.

1. Sherwin BB. Hormones, mood, and cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:20S-26S.

2. Raisz LG, Wiita B, Artis A, et al. Comparison of the effects of estrogen alone and estrogen plus androgen on biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:37-43.

3. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

4. Buster JE, et al. In: Lobo RA, ed. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:142.

5. Davison S, et al. Testosterone levels in women decline with aging. Abstract presented at the Endocrine Society Annual Meeting, held June 16–19, 2004, New Orleans.

6. Hughes CL, Jr, Wall LL, Creasman WT. Reproductive hormone levels in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing surgical castration after spontaneous menopause. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:42-45.

7. Selby C. Sex hormone-binding globulin. Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:532-541.

8. Simon JA. Estrogen replacement therapy: effects on the endogenous androgen milieu. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S77-S82.

9. Miller KK, Biller BM, Hier J, Arena E, Klibanski A. Androgens and bone density in women with hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2770-2776.

10. Sarrel PM. Broadened spectrum of menopausal symptom relief. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:734-740.

11. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

12. Guay AT. Screening for androgen deficiency in women: methodological and interpretive issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S83-S88.

13. Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, Block B, Van Der Hoop RG. Comparative effects of oral and esterified estrogens with or without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles on dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

14. Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

15. Buster JE, Kingsberg SA, Aguirre O, et al. Testosterone patch for low sexual desire in surgically menopausal women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:938-940.

16. Mushayandebvu T, Castracane VD, Gimpel T, Adel T, Santoro N. Evidence for diminished midcycle ovarian androgen production in older reproductive aged women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:721-723.

17. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

18. Vermeulen A. The hormonal activity of the postmenopausal ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:247-253.

19. Sarrel P, Dobay B, Wiita B. Estrogen and estrogen–androgen replacement in postmenopausal women dissatisfied with estrogen-only therapy. Sexual behavior and neuroendocrine responses. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:847-856.

20. Braunstein GD. Androgen insufficiency in women: summary of critical issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(suppl 4):S94-S99.

1. Sherwin BB. Hormones, mood, and cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:20S-26S.

2. Raisz LG, Wiita B, Artis A, et al. Comparison of the effects of estrogen alone and estrogen plus androgen on biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:37-43.

3. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

4. Buster JE, et al. In: Lobo RA, ed. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:142.

5. Davison S, et al. Testosterone levels in women decline with aging. Abstract presented at the Endocrine Society Annual Meeting, held June 16–19, 2004, New Orleans.

6. Hughes CL, Jr, Wall LL, Creasman WT. Reproductive hormone levels in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing surgical castration after spontaneous menopause. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:42-45.

7. Selby C. Sex hormone-binding globulin. Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:532-541.

8. Simon JA. Estrogen replacement therapy: effects on the endogenous androgen milieu. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S77-S82.

9. Miller KK, Biller BM, Hier J, Arena E, Klibanski A. Androgens and bone density in women with hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2770-2776.

10. Sarrel PM. Broadened spectrum of menopausal symptom relief. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:734-740.

11. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

12. Guay AT. Screening for androgen deficiency in women: methodological and interpretive issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S83-S88.

13. Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, Block B, Van Der Hoop RG. Comparative effects of oral and esterified estrogens with or without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles on dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

14. Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

15. Buster JE, Kingsberg SA, Aguirre O, et al. Testosterone patch for low sexual desire in surgically menopausal women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:938-940.

16. Mushayandebvu T, Castracane VD, Gimpel T, Adel T, Santoro N. Evidence for diminished midcycle ovarian androgen production in older reproductive aged women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:721-723.

17. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

18. Vermeulen A. The hormonal activity of the postmenopausal ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:247-253.

19. Sarrel P, Dobay B, Wiita B. Estrogen and estrogen–androgen replacement in postmenopausal women dissatisfied with estrogen-only therapy. Sexual behavior and neuroendocrine responses. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:847-856.

20. Braunstein GD. Androgen insufficiency in women: summary of critical issues. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(suppl 4):S94-S99.

MENOPAUSE

I am delighted that Dr. Michael McClung, an internationally recognized expert in skeletal health, has agreed to review current evidence on the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in menopausal women in the latter part of this article.

New WHI analysis confirms safety of short-term combination HT

Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Rossouw JE, et al. Prior hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial of estrogen and progestin. Maturitas. 2006;55:103–115.

At the annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in December, investigators presented data showing that the incidence of breast cancer in US women decreased by 7% from 2002 to 2003, a striking decline that was most prominent among women aged 50 to 69 years. The presenters speculated that the plummeting rates of HT use following publication of the initial Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) findings in the summer of 2002 (in regard to the estrogen–progestin arm2) might be responsible for this decline.3

The major media attention that followed this presentation makes one thing clear: Concerns about developing breast cancer with HT use continue to fuel anxiety among women. Although secular trend data on the national breast cancer incidence can help generate hypotheses, they cannot explain the trends. What can shed light on the association between estrogen–progestin HT and breast cancer are important new data recently released by WHI investigators.

Women new to HT had no increased risk of breast cancer

In the 2006 subgroup analysis of WHI participants in the estrogen–progestin arm, investigators focused on HT use before enrollment in the trial. Recall that in this part of the WHI, 16,608 women with an intact uterus were randomized to conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate or placebo. Use of the study medication was stopped after a mean follow-up of 5.6 years (mean exposure to HT: 4.4 years). Overall, the risk of invasive breast cancer was slightly higher with combination HT than placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.54).2

In the 2006 report from the 2002 WHI study of estrogen–progestin HT versus placebo, investigators compared the risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer in 12,297 women who had not used HT prior to study enrollment with the risk in 4,311 participants who had previously used HT. Of the previous users, 42% reported less than 2 years of use prior to WHI enrollment, and 36% reported more than 4 years of HT prior to WHI enrollment.

The findings: Among WHI participants who had never before used HT, the use of estrogen–progestin HT in the study was not associated with an elevated risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.77–1.36). However, among previous HT users, the additional use of HT in the WHI study was associated with a risk nearly double that of placebo users (HR 1.96, 95% CI 1.17–3.27).

The reassuring results of this WHI subgroup analysis received little media attention in the United States, probably because the report appeared in a journal that has low readership in this country. WHI and other findings allow us to reassure women who have undergone hysterectomy that use of unopposed estrogen has little, if any, impact on breast cancer risk in menopausal women.4,5 This new WHI subgroup analysis, along with a recent review of European and North American data,6 allows ObGyns to counsel women with an intact uterus that up to 5 years of combination estrogen–progestin hormone therapy also has little, if any, impact on breast cancer risk.

Not much to recommend among nonhormonal therapies

Newton KM, Reed SD, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Ehrlich K, Guiltinan J. Treatment of vasomotor symptoms of menopause with black cohosh, multibotanicals, soy, hormone therapy or placebo. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:869–879.

Grady D. Clinical practice. Management of menopausal symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2338–2347.

Grady D, Cohen B, Tice J, et al. Ineffectiveness of sertraline for treatment of menopausal hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:823–830.

Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Barton DL, et al. Phase III trial of gabapentin alone or in conjunction with an antidepressant in the management of hot flashes in women who have inadequate control with an antidepressant alone: NCCTG N03C5. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:308–312.

Since publication of the initial WHI findings in 2002,2 interest in nonhormonal management of vasomotor symptoms has increased among menopausal women and their clinicians. The botanical black cohosh and “nutraceutical” soy or isoflavone supplements represent the nonprescription remedies most widely used for relief of hot flashes. Unfortunately, accumulating evidence does not support the efficacy of these popular remedies.

In a recent NIH-funded, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, Newton and colleagues compared the following interventions:

- black cohosh, 160 mg daily

- daily multibotanical supplement that included 200 mg of black cohosh and 9 other ingredients

- the multibotanical supplement plus counseling regarding dietary soy

- conjugated equine estrogen, 0.625 mg daily (with or without 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate)

- placebo

The findings: At 3, 6, and 12 months, women allocated to estrogen (with or without progestin) had statistically significant relief of symptoms. In contrast, women allocated to botanical and/or herbal supplements experienced minimal relief, comparable to the effects of placebo.

The findings of this important study, as well as those of Grady, are discouraging: Black cohosh, botanicals, and encouraging increased soy intake are ineffective in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

Evidence on antidepressants is inconclusive

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the antidepressant venlafaxine have been assessed for their effects on menopausal vasomotor symptoms, particularly in breast cancer survivors. In a recent review and also a randomized trial, Grady reports that the SSRIs citalopram and sertraline do not appear to be effective, and the findings in regard to the SSRI fluoxetine and venlafaxine have been inconsistent. Compared with placebo, the SSRI paroxetine has eased vasomotor symptoms to a modest degree in breast cancer survivors, but had little effect in women who have not had the disease.

Breast cancer survivors often take tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, medications that can induce or aggravate hot flashes. Breast cancer survivors also have a higher prevalence of mood disorders. These factors suggest that the experience and treatment of menopausal symptoms differ between breast cancer survivors and the general population.

Overall, Grady notes, for women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms who have no history of breast cancer, clinical trials of antidepressants have not been encouraging.

Gabapentin is more effective than antidepressants, but with a price

Clinical trials of gabapentin suggest that this anticonvulsant is moderately effective in the nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms, and the phase III trial by Loprinzi and colleagues finds it to be more effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms than antidepressants.

The drawback? This drug must be taken 2 or 3 times daily, and side effects (including fatigue) limit its attractiveness.

When deciding whom to treat, consider risk as well as BMD

Sanders KM, Nicholson GC, Watts JJ, et al. Half the burden of fragility fractures in the community occur in women without osteoporosis. When is fracture prevention cost-effective? Bone. 2006;38:694–700.

The diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women is now based on a threshold bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of –2.5. However, BMD is only one of several important risk factors for fracture, and most patients who experience a fracture related to osteoporosis do not have BMD values in the range consistent with osteoporosis, as Sanders and colleagues observe. Therefore, clinicians are faced with this question: Which patients who do not have osteoporosis should be treated to prevent fracture?