User login

Hormonal contraception in women with medical conditions

Decisive new data on risks and benefits of hormonal contraception will change how we manage many patients. These findings prompted the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update its practice bulletin (released in June) on hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions.1 Among the most notable areas of change:

- Family history of breast cancer or BRCA1 or 2 mutations. Combination oral contraceptives (OCs) do not appear to increase the risk of breast cancer in these women, and do help prevent ovarian cancer.

- Concomitant medications. More women are using enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants for conditions other than seizure disorders; some affect steroid levels.

- Obesity. Progestin-only and intrauterine methods may be better for obese women older than 35 years, who face an elevated baseline risk of venous thromboembolism.

- Lupus. Combination OCs are safe in women with stable, mild disease who are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although bone density declines in women using DMPA, it recovers within 3 years after the drug is discontinued.

- Patch and ring. Until method-specific data come in, assume that the patch and ring have the same contraindications as combination OCs.

For the fine points on these and other findings, we talked with Dr. Andrew M. Kaunitz, who assisted ACOG with preparation of the new bulletin.1

1. Breast cancer risk

OCs do not add to existing high risk

OBG Management: Women who have a family history of breast cancer have a higher-than-average risk of developing the cancer themselves, and it is widely assumed that estrogen further heightens that risk. Should these women avoid combination OCs?

KAUNITZ: No. Although these women have been reluctant to use hormonal contraceptives (as have many caregivers), we now have several lines of reassuring evidence.

Among the studies demonstrating safety of hormonal methods in this population is the 2002 Women’s CARE study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which found no elevated risk of breast cancer in women currently or formerly using OCs, compared with women who had never used them.

This study compared 4,575 women who had breast cancer with 4,682 controls. The relative risk of breast cancer was 1.0 (95% confidence interval 0.8–1.3) among current OC users and 0.9 (0.8–1.0) among women who had previously used OCs. The relative risk did not increase consistently with higher doses or longer use.2 Nor did use of OCs add risk in women with a family history of breast cancer.2

OBG Management: An editorial accompanying that study said: “The importance of this finding for public health is enormous, because more than 75% of the women in the study had used oral contraceptives.”3

KAUNITZ: Yes, but this does not mean that women with a positive family history have no increased risk of breast cancer—they do. Rather, the use of hormonal contraceptives does not augment that risk further.

OBG Management: What about women with other high-risk factors, such as germline mutations? Do OCs increase their risk of breast cancer?

KAUNITZ: No. In the largest study to date of breast cancer risk associated with prior or current OC use in women 35 to 64 years of age with BRCA1 and 2 mutations, low-dose OC formulations did not increase it.4 In fact, OC use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers (odds ratio 0.22; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.49).4

Pill reduces risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA carriers

KAUNITZ: It is also important to remember the higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations. We now know that use of the Pill reduces ovarian cancer risk in BRCA-positive women, just as it does in the general population. In a study involving 451 women with BRCA1 or 2 mutations, who self-reported their lifetime history of OC use (or nonuse), the odds ratio for ovarian cancer associated with OC use for a minimum of 1 year was 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.53–1.36) and declined by 5% (1%–9%) with each additional year of use (P for trend=.01). Use for 6 years or more carried an odds ratio of 0.62 (0.35–1.09).5

The bottom line: Women with a family history of breast cancer in general or BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations more specifically, who have not completed childbearing or who want to avoid prophylactic mastectomy/oophorectomy, can use the Pill to prevent ovarian cancer without increasing their risk of breast cancer.5,6

2. Concomitant medications

Some drugs decrease steroid levels

Anticonvulsants

OBG Management: Many, perhaps most, women with medical conditions are already taking some kind of medication. What do ObGyns need to know about interactions between hormonal contraceptives and other medications, such as anticonvulsants and antibiotics?

KAUNITZ: We regularly encounter patients who are using anticonvulsants, both older and newer formulations.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants for indications other than seizure disorders (eg, bipolar disease) is increasing.

Levetiracetam and zonisamide. The revised practice bulletin includes pharmacokinetic data on 2 new anticonvulsants—levetiracetam7 and zonisamide.8 Fortunately, neither appears to reduce contraceptive steroid levels in women who are also taking combination OCs.

Which dosage, which method? Some widely used anticonvulsants do decrease steroid levels (TABLE 1); although some clinicians prescribe OCs containing 50 μg of ethinyl estradiol to offset the reduction, there is no evidence that this strategy is effective. The ObGyn may consider prescribing pills containing 30 to 35 μg of estradiol rather than lower doses, although again, we lack data to support this recommendation.

Another important point: Because serum steroid levels of women using progestin-only OCs and implants are lower than for combination OCs, low-dose progestin-only methods (progestin-only minipills and progestin implants) do not represent by themselves optimal contraceptives for women taking drugs (eg, anticonvulsants) that increase liver enzymes.9,10

This recommendation does not include the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraceptive effects remain high with its use, even when anticonvulsants or other liver enzyme-inducing drugs are taken.11

DMPA, a high-dose progestin contraceptive, has not been formally studied in this regard; the efficacy of this injectable contraceptive does not appear to be reduced by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.30 Interestingly enough, DMPA has anticonvulsant effects itself and therefore may represent a particularly attractive contraceptive for women taking anticonvulsants.12

TABLE 1

Some anticonvulsants reduce steroid levels in women taking OCs, and some do not

| Interaction of anticonvulsants and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants that decrease steroid levels in women taking oral contraceptives (OCs) | |

| Barbiturates (including phenobarbital and primidone) | |

| Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine | |

| Felbamate | |

| Phenytoin | |

| Topiramate | |

| Vigabatrin | |

| Anticonvulsants that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking combination OCs | |

| Ethosuximide* | Tiagabine† |

| Gabapentin† | Valproic acid |

| Lamotrigine† | Zonisamide |

| Levetiracetam | |

| * No pharmacokinetic data available. | |

| †Pharmacokinetic study used anticonvulsant dose lower than that used in clinical practice. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antibiotics

KAUNITZ: As for antibiotics, we have often been taught that many drugs lower the efficacy of combination OCs, but in fact it is not clear that they do.

Rifampin. The only antibiotic for which we have pharmacokinetic evidence of substantially lower steroid levels is rifampin13 (although anecdotal reports of OC failure in women taking other antibiotics have been noted). Therefore, any woman who is taking rifampin should be advised that OCs (combination or progestin-only), transdermal or vaginal contraceptives, and hormonal implants are inadequate birth control (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Rifampin decreases steroid levels in women taking combination OCs; other anti-infectives do not

| Interaction of anti-infective agents and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anti-infective that decreases steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Rifampin | |

| Anti-infectives that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Ampicillin | Miconazole* |

| Doxycycline | Quinolone antibiotics |

| Fluconazole | Tetracycline |

| Metronidazole | |

| *Vaginal administration does not lower steroid levels in women using the contraceptive vaginal ring. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antiretrovirals

KAUNITZ: Several small trials suggest that contraceptive steroid levels in OC users may be affected by antiretroviral medications (TABLE 3), but we lack clinical outcome studies.

TABLE 3

Antiretrovirals may affect steroid levels in women taking OCs

| Pharmacokinetic interactions between combination OCs and antiretroviral drugs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ANTIRETROVIRAL | CONTRACEPTIVE STEROID LEVELS | ANTIRETROVIRAL LEVELS |

| PROTEASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nelfinavir | ↓ | No data |

| Ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Atazanavir | ↑ | No data |

| Amprenavir | ↑ | ↓ |

| Indinavir | ↑ | No data |

| Saquinavir | No data | No change |

| NONNUCLEOSIDE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nevirapine | ↓ | No change |

| Efavirenz | ↑ | No change |

| Delavirdine | ?↑ | No data |

| Source: World Health Organization.29 Reprinted by permission. | ||

St. John’s wort

KAUNITZ: Another medication I want to mention is St. John’s wort, an over-the-counter hepatic enzyme inducer that many women take for depression. One clinical trial found elevated progestin and estrogen metabolism in women taking combination OCs and St. John’s wort concomitantly, as well as increased likelihood of breakthrough bleeding and ovulation.

St. John’s wort (300 mg thrice daily) was associated with a 13% to 15% reduction in the dose exposure of combination OCs containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol.14 So it is important to ask about St. John’s wort when counseling a woman about contraception.

St. John’s wort raised progestin and estrogen metabolism and increased breakthrough bleeding and ovulation in women taking OCs

3. Obesity

In obese women over 35, avoid combination OCs

OBG Management: ObGyns are seeing increasing numbers of overweight and obese women. Has selection of hormonal contraception for these women changed?

KAUNITZ: Yes. We now have a recognized obesity epidemic on our hands—and obesity, age over 35 years, and use of combination OCs all represent independent risk factors for thrombosis—prompting the question: Are there safer alternatives to combination OCs for obese women older than 35?

Tenfold risk for thromboembolism. Among the evidence addressing this question, a 2003 Dutch study found that women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 who used combination OCs had 10 times the risk of venous thromboembolism of lean controls who did not use the Pill.15

Thus, progestin-only and intrauterine contraceptive methods may be more appropriate for older obese women. This language about obesity and combination contraceptives was not in the earlier version of the practice bulletin.

No need to rule out the patch

OBG Management: Aren’t some hormonal contraceptives less effective in obese women?

KAUNITZ: In a 2002 analysis of pooled data, women in the highest weight category (≥90 kg) who were using the contraceptive patch had a higher pregnancy rate than lower-weight women.16 However, this finding does not rule out use of the patch in overweight women who prefer it to less effective methods. Rather, it should be kept in mind when counseling these patients about their options.

Although the new ACOG bulletin cites data from Holt et al17 suggesting a higher failure rate in obese women using combination OCs, other OC clinical trials have not confirmed this association.18,19 In a study by Anderson and colleagues,18 which found no pregnancies among the heaviest women, the mean weight was 155.9 lb, but ranged from 91.0 to 360.0 lb, and the mean BMI was 26.0, but ranged from 15.2 to an extreme of 56.5!

What about DMPA? We also lack evidence of higher pregnancy rates among overweight women using DMPA (150-mg intramuscular or 104-mg subcutaneous formulations).20,21

4. Lupus

OCs are an option in some women with lupus

OBG Management: As The New England Journal of Medicine observed last year, there has been an “implicit moratorium” on prescribing combination hormonal contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) because clinicians have feared that exogenous estrogens might exacerbate disease.22 This moratorium derives from data suggesting that estrogens worsen SLE, while androgens appear to protect against the condition.

The new practice bulletin now indicates that oral contraceptives are an option for this population. What is behind the change?

KAUNITZ: We now have data from 2 randomized clinical trials23,24 indicating that women can safely use combination OCs if they:

- have stable, mild disease

- are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies

- have no history of thrombosis

Disease remained stable. In the first trial,24 162 women with mild, stable SLE were randomized to combination OCs, progestin-only pills, or the copper IUD. Their disease level was established at baseline and over 12 months, using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index. Disease remained stable in all 3 groups.

Estrogen did not increase severity of SLE. In the second trial,23 183 women with inactive or stable active SLE were randomized to combination OCs or placebo. The primary endpoint for this trial was severe lupus flare: 7 of 91 women (7.7%) in the OC group experienced a flare, compared with 7 of 92 women (7.6%) taking placebo. Thus, estrogen does not appear to increase the severity of SLE.

OBG Management: Isn’t another concern about patients with SLE the substantial risk of thrombosis?

KAUNITZ: Yes. In the first study,24 2 thromboses occurred in women taking OCs, and 2 occurred in women using the progestin-only pill. All the women with thromboses were seropositive for antiphospholipid antibodies. Hence, we need to exclude the presence of these antibodies in women with SLE prior to prescribing combination estrogen-progestin contraception. In women with lupus and a history of thrombosis, as with all women with a history of thrombosis, we should avoid combination hormonal contraception.

In the second study,23 which compared women on combination OCs to a placebo group, the OC group experienced 1 case of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and 1 clotted graft. The placebo group experienced 1 case of DVT, 1 ocular thrombosis, 1 superficial thrombophlebitis, and 1 death (after the trial ended).

5. DMPA and bone density

DMPA does not appear to have long-term impact

OBG Management: There has been some furor over DMPA’s effect on bone mineral density (BMD). What are the latest findings in this area?

KAUNITZ: Studies assessing BMD in former DMPA users, including postmenopausal women, show that prior use of DMPA does not appear to have any long-term impact on BMD.25,26 In addition, more recent longitudinal data indicate that after DMPA is discontinued BMD fully recovers, which appears to take about 3 years in adults and as little as 1 year in teens.27,28

One population-based prospective cohort study followed 457 nongravid women aged 18 to 39 years. These women had bone density measured every 6 months for 3 years using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Although bone density decreased among DMPA users at the spine and total hip compared with nonusers, there was no difference in bone density 30 months after discontinuation of birth control injections.27

In a study of 170 adolescent women 14 to 18 years of age, 80 were DMPA users and 90 were nonusers. Bone density was measured every 6 months for 24 or 36 months, and declined significantly at the hip and spine in DMPA users. Sixty-one women discontinued DMPA during the course of the study. After discontinuation, bone density increased at all anatomical sites, recovering completely over the course of 1 year.28

Although the US Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in the fall of 2004 that use of DMPA should be reconsidered after 2 years, particularly in teens, the studies I just mentioned suggest there should be no routine restrictions on the use of DMPA in terms of skeletal health, and that DMPA use by itself is not an indication for bone density measurement.

6. Patch and ring

Assume contraindications are the same as for OCs

OBG Management: What about newer forms of combination contraceptives such as the patch and ring?

KAUNITZ: The new practice bulletin contains information on the patch, the ring, and the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, which were not available when the earlier bulletin was prepared. In that version we talked about combination pills only.

Even so, we continue to have much more data on the Pill than the ring or patch. For that reason, until more data become available, the patch and the ring should be assumed to have the same contraindications as combination OCs. We have very little data—if any—on the use of newer combination contraceptives in high-risk women or those with medical problems.

1. Use of Hormonal Contraception in Women With Coexisting Medical Conditions. ACOG Practice Bulletin #73. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

2. Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2025-2032.

3. Davidson NE, Helzlsouer KJ. Good news about oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2078-2079.

4. Milne RL, Knight JA, John EM, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of early-onset breast cancer in carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:350-356.

5. Whittemore AS, Balise RR, Pharoah PD, et al. Oral contraceptive use and ovarian cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1911-1915.

6. Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424-428.

7. Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Levy RH, Janik F. Levetiracetam does not alter the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive in healthy women. Epilepsia. 2002;43:697-702.

8. Griffith SG, Dai Y. Effect of zonisamide on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a combination ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone oral contraceptive in healthy women. Clin Ther. 2004;26:2056-2065.

9. McCann MF, Potter LS. Progestin-only oral contraception: a comprehensive review. Contraception. 1994;50(6 suppl 1):S1-S195.

10. Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

11. Bounds W, Guillebaud J. Observational series on women using the contraceptive Mirena concurrently with antiepileptic and other enzyme-inducing drugs. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;187:551-555.

12. Mattson RH, Rebar RW. Contraceptive methods for women with neurologic disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:2027-2032.

13. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, Crawford F, et al. The effect of rifampicin on norethisterone pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15:193-197.

14. Murphy PA, Kern SE, Stanczyk FZ, Westhoff CL. Interaction of St. John’s wort with oral contraceptives: effects on the pharmacokinetics of norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol, ovarian activity, and breakthrough bleeding. Contraception. 2005;71:402-408.

15. Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal F. Obesity: risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493-498.

16. Zieman M, Guillebaud J, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S13-S18.

17. Holt VL, Scholes D, Wicklund KG, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Body mass index, weight, and oral contraceptive failure risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:46-52.

18. Anderson FD. Hait H and the Seasonale-301 Study Group. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

19. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

20. Leiman G. Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive agent: its effect on weight and blood pressure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:97-102.

21. Jain J, Jakimiuk AJ, Bode FR, Ross D, Kaunitz AM. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of DMPA-SC. Contraception. 2004;70:269-275.

22. Bermas BL. Oral contraceptives in systemic lupus erythematosus—a tough pill to swallow? N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2602-2604.

23. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. OC-SELENA Trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2550-2558.

24. Sanchez-Guerrero, Urive AG, Jimenez-Santana L, et al. A trial of contraceptive methods in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2539-2549.

25. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, et al. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49:615-618.

26. Petitti DB, Piaggio G, Mehta S, Cravioto MC, Meirik O. Steroid hormone contraception and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study in an international population. The WHO Study of Hormonal Contraception and Bone Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:736-744.

27. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: results from a prospective study [published erratum appears in Epidemiology. 2002;13:749]. Epidemiology. 2002;13:581-587.

28. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, et al. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:139-144.

29. World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Annex 1. COCs and antiretroviral therapies. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

30. Sapire KE. Depo-provera and carbamazapine. Br J Fam Plann. 1990;15:130.-

Dr. Kaunitz has received funding from Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, and the National Institutes of Health. He is a speaker or consultant for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals, Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble; and holds stock with Noven, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis.

Decisive new data on risks and benefits of hormonal contraception will change how we manage many patients. These findings prompted the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update its practice bulletin (released in June) on hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions.1 Among the most notable areas of change:

- Family history of breast cancer or BRCA1 or 2 mutations. Combination oral contraceptives (OCs) do not appear to increase the risk of breast cancer in these women, and do help prevent ovarian cancer.

- Concomitant medications. More women are using enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants for conditions other than seizure disorders; some affect steroid levels.

- Obesity. Progestin-only and intrauterine methods may be better for obese women older than 35 years, who face an elevated baseline risk of venous thromboembolism.

- Lupus. Combination OCs are safe in women with stable, mild disease who are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although bone density declines in women using DMPA, it recovers within 3 years after the drug is discontinued.

- Patch and ring. Until method-specific data come in, assume that the patch and ring have the same contraindications as combination OCs.

For the fine points on these and other findings, we talked with Dr. Andrew M. Kaunitz, who assisted ACOG with preparation of the new bulletin.1

1. Breast cancer risk

OCs do not add to existing high risk

OBG Management: Women who have a family history of breast cancer have a higher-than-average risk of developing the cancer themselves, and it is widely assumed that estrogen further heightens that risk. Should these women avoid combination OCs?

KAUNITZ: No. Although these women have been reluctant to use hormonal contraceptives (as have many caregivers), we now have several lines of reassuring evidence.

Among the studies demonstrating safety of hormonal methods in this population is the 2002 Women’s CARE study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which found no elevated risk of breast cancer in women currently or formerly using OCs, compared with women who had never used them.

This study compared 4,575 women who had breast cancer with 4,682 controls. The relative risk of breast cancer was 1.0 (95% confidence interval 0.8–1.3) among current OC users and 0.9 (0.8–1.0) among women who had previously used OCs. The relative risk did not increase consistently with higher doses or longer use.2 Nor did use of OCs add risk in women with a family history of breast cancer.2

OBG Management: An editorial accompanying that study said: “The importance of this finding for public health is enormous, because more than 75% of the women in the study had used oral contraceptives.”3

KAUNITZ: Yes, but this does not mean that women with a positive family history have no increased risk of breast cancer—they do. Rather, the use of hormonal contraceptives does not augment that risk further.

OBG Management: What about women with other high-risk factors, such as germline mutations? Do OCs increase their risk of breast cancer?

KAUNITZ: No. In the largest study to date of breast cancer risk associated with prior or current OC use in women 35 to 64 years of age with BRCA1 and 2 mutations, low-dose OC formulations did not increase it.4 In fact, OC use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers (odds ratio 0.22; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.49).4

Pill reduces risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA carriers

KAUNITZ: It is also important to remember the higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations. We now know that use of the Pill reduces ovarian cancer risk in BRCA-positive women, just as it does in the general population. In a study involving 451 women with BRCA1 or 2 mutations, who self-reported their lifetime history of OC use (or nonuse), the odds ratio for ovarian cancer associated with OC use for a minimum of 1 year was 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.53–1.36) and declined by 5% (1%–9%) with each additional year of use (P for trend=.01). Use for 6 years or more carried an odds ratio of 0.62 (0.35–1.09).5

The bottom line: Women with a family history of breast cancer in general or BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations more specifically, who have not completed childbearing or who want to avoid prophylactic mastectomy/oophorectomy, can use the Pill to prevent ovarian cancer without increasing their risk of breast cancer.5,6

2. Concomitant medications

Some drugs decrease steroid levels

Anticonvulsants

OBG Management: Many, perhaps most, women with medical conditions are already taking some kind of medication. What do ObGyns need to know about interactions between hormonal contraceptives and other medications, such as anticonvulsants and antibiotics?

KAUNITZ: We regularly encounter patients who are using anticonvulsants, both older and newer formulations.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants for indications other than seizure disorders (eg, bipolar disease) is increasing.

Levetiracetam and zonisamide. The revised practice bulletin includes pharmacokinetic data on 2 new anticonvulsants—levetiracetam7 and zonisamide.8 Fortunately, neither appears to reduce contraceptive steroid levels in women who are also taking combination OCs.

Which dosage, which method? Some widely used anticonvulsants do decrease steroid levels (TABLE 1); although some clinicians prescribe OCs containing 50 μg of ethinyl estradiol to offset the reduction, there is no evidence that this strategy is effective. The ObGyn may consider prescribing pills containing 30 to 35 μg of estradiol rather than lower doses, although again, we lack data to support this recommendation.

Another important point: Because serum steroid levels of women using progestin-only OCs and implants are lower than for combination OCs, low-dose progestin-only methods (progestin-only minipills and progestin implants) do not represent by themselves optimal contraceptives for women taking drugs (eg, anticonvulsants) that increase liver enzymes.9,10

This recommendation does not include the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraceptive effects remain high with its use, even when anticonvulsants or other liver enzyme-inducing drugs are taken.11

DMPA, a high-dose progestin contraceptive, has not been formally studied in this regard; the efficacy of this injectable contraceptive does not appear to be reduced by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.30 Interestingly enough, DMPA has anticonvulsant effects itself and therefore may represent a particularly attractive contraceptive for women taking anticonvulsants.12

TABLE 1

Some anticonvulsants reduce steroid levels in women taking OCs, and some do not

| Interaction of anticonvulsants and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants that decrease steroid levels in women taking oral contraceptives (OCs) | |

| Barbiturates (including phenobarbital and primidone) | |

| Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine | |

| Felbamate | |

| Phenytoin | |

| Topiramate | |

| Vigabatrin | |

| Anticonvulsants that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking combination OCs | |

| Ethosuximide* | Tiagabine† |

| Gabapentin† | Valproic acid |

| Lamotrigine† | Zonisamide |

| Levetiracetam | |

| * No pharmacokinetic data available. | |

| †Pharmacokinetic study used anticonvulsant dose lower than that used in clinical practice. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antibiotics

KAUNITZ: As for antibiotics, we have often been taught that many drugs lower the efficacy of combination OCs, but in fact it is not clear that they do.

Rifampin. The only antibiotic for which we have pharmacokinetic evidence of substantially lower steroid levels is rifampin13 (although anecdotal reports of OC failure in women taking other antibiotics have been noted). Therefore, any woman who is taking rifampin should be advised that OCs (combination or progestin-only), transdermal or vaginal contraceptives, and hormonal implants are inadequate birth control (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Rifampin decreases steroid levels in women taking combination OCs; other anti-infectives do not

| Interaction of anti-infective agents and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anti-infective that decreases steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Rifampin | |

| Anti-infectives that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Ampicillin | Miconazole* |

| Doxycycline | Quinolone antibiotics |

| Fluconazole | Tetracycline |

| Metronidazole | |

| *Vaginal administration does not lower steroid levels in women using the contraceptive vaginal ring. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antiretrovirals

KAUNITZ: Several small trials suggest that contraceptive steroid levels in OC users may be affected by antiretroviral medications (TABLE 3), but we lack clinical outcome studies.

TABLE 3

Antiretrovirals may affect steroid levels in women taking OCs

| Pharmacokinetic interactions between combination OCs and antiretroviral drugs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ANTIRETROVIRAL | CONTRACEPTIVE STEROID LEVELS | ANTIRETROVIRAL LEVELS |

| PROTEASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nelfinavir | ↓ | No data |

| Ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Atazanavir | ↑ | No data |

| Amprenavir | ↑ | ↓ |

| Indinavir | ↑ | No data |

| Saquinavir | No data | No change |

| NONNUCLEOSIDE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nevirapine | ↓ | No change |

| Efavirenz | ↑ | No change |

| Delavirdine | ?↑ | No data |

| Source: World Health Organization.29 Reprinted by permission. | ||

St. John’s wort

KAUNITZ: Another medication I want to mention is St. John’s wort, an over-the-counter hepatic enzyme inducer that many women take for depression. One clinical trial found elevated progestin and estrogen metabolism in women taking combination OCs and St. John’s wort concomitantly, as well as increased likelihood of breakthrough bleeding and ovulation.

St. John’s wort (300 mg thrice daily) was associated with a 13% to 15% reduction in the dose exposure of combination OCs containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol.14 So it is important to ask about St. John’s wort when counseling a woman about contraception.

St. John’s wort raised progestin and estrogen metabolism and increased breakthrough bleeding and ovulation in women taking OCs

3. Obesity

In obese women over 35, avoid combination OCs

OBG Management: ObGyns are seeing increasing numbers of overweight and obese women. Has selection of hormonal contraception for these women changed?

KAUNITZ: Yes. We now have a recognized obesity epidemic on our hands—and obesity, age over 35 years, and use of combination OCs all represent independent risk factors for thrombosis—prompting the question: Are there safer alternatives to combination OCs for obese women older than 35?

Tenfold risk for thromboembolism. Among the evidence addressing this question, a 2003 Dutch study found that women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 who used combination OCs had 10 times the risk of venous thromboembolism of lean controls who did not use the Pill.15

Thus, progestin-only and intrauterine contraceptive methods may be more appropriate for older obese women. This language about obesity and combination contraceptives was not in the earlier version of the practice bulletin.

No need to rule out the patch

OBG Management: Aren’t some hormonal contraceptives less effective in obese women?

KAUNITZ: In a 2002 analysis of pooled data, women in the highest weight category (≥90 kg) who were using the contraceptive patch had a higher pregnancy rate than lower-weight women.16 However, this finding does not rule out use of the patch in overweight women who prefer it to less effective methods. Rather, it should be kept in mind when counseling these patients about their options.

Although the new ACOG bulletin cites data from Holt et al17 suggesting a higher failure rate in obese women using combination OCs, other OC clinical trials have not confirmed this association.18,19 In a study by Anderson and colleagues,18 which found no pregnancies among the heaviest women, the mean weight was 155.9 lb, but ranged from 91.0 to 360.0 lb, and the mean BMI was 26.0, but ranged from 15.2 to an extreme of 56.5!

What about DMPA? We also lack evidence of higher pregnancy rates among overweight women using DMPA (150-mg intramuscular or 104-mg subcutaneous formulations).20,21

4. Lupus

OCs are an option in some women with lupus

OBG Management: As The New England Journal of Medicine observed last year, there has been an “implicit moratorium” on prescribing combination hormonal contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) because clinicians have feared that exogenous estrogens might exacerbate disease.22 This moratorium derives from data suggesting that estrogens worsen SLE, while androgens appear to protect against the condition.

The new practice bulletin now indicates that oral contraceptives are an option for this population. What is behind the change?

KAUNITZ: We now have data from 2 randomized clinical trials23,24 indicating that women can safely use combination OCs if they:

- have stable, mild disease

- are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies

- have no history of thrombosis

Disease remained stable. In the first trial,24 162 women with mild, stable SLE were randomized to combination OCs, progestin-only pills, or the copper IUD. Their disease level was established at baseline and over 12 months, using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index. Disease remained stable in all 3 groups.

Estrogen did not increase severity of SLE. In the second trial,23 183 women with inactive or stable active SLE were randomized to combination OCs or placebo. The primary endpoint for this trial was severe lupus flare: 7 of 91 women (7.7%) in the OC group experienced a flare, compared with 7 of 92 women (7.6%) taking placebo. Thus, estrogen does not appear to increase the severity of SLE.

OBG Management: Isn’t another concern about patients with SLE the substantial risk of thrombosis?

KAUNITZ: Yes. In the first study,24 2 thromboses occurred in women taking OCs, and 2 occurred in women using the progestin-only pill. All the women with thromboses were seropositive for antiphospholipid antibodies. Hence, we need to exclude the presence of these antibodies in women with SLE prior to prescribing combination estrogen-progestin contraception. In women with lupus and a history of thrombosis, as with all women with a history of thrombosis, we should avoid combination hormonal contraception.

In the second study,23 which compared women on combination OCs to a placebo group, the OC group experienced 1 case of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and 1 clotted graft. The placebo group experienced 1 case of DVT, 1 ocular thrombosis, 1 superficial thrombophlebitis, and 1 death (after the trial ended).

5. DMPA and bone density

DMPA does not appear to have long-term impact

OBG Management: There has been some furor over DMPA’s effect on bone mineral density (BMD). What are the latest findings in this area?

KAUNITZ: Studies assessing BMD in former DMPA users, including postmenopausal women, show that prior use of DMPA does not appear to have any long-term impact on BMD.25,26 In addition, more recent longitudinal data indicate that after DMPA is discontinued BMD fully recovers, which appears to take about 3 years in adults and as little as 1 year in teens.27,28

One population-based prospective cohort study followed 457 nongravid women aged 18 to 39 years. These women had bone density measured every 6 months for 3 years using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Although bone density decreased among DMPA users at the spine and total hip compared with nonusers, there was no difference in bone density 30 months after discontinuation of birth control injections.27

In a study of 170 adolescent women 14 to 18 years of age, 80 were DMPA users and 90 were nonusers. Bone density was measured every 6 months for 24 or 36 months, and declined significantly at the hip and spine in DMPA users. Sixty-one women discontinued DMPA during the course of the study. After discontinuation, bone density increased at all anatomical sites, recovering completely over the course of 1 year.28

Although the US Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in the fall of 2004 that use of DMPA should be reconsidered after 2 years, particularly in teens, the studies I just mentioned suggest there should be no routine restrictions on the use of DMPA in terms of skeletal health, and that DMPA use by itself is not an indication for bone density measurement.

6. Patch and ring

Assume contraindications are the same as for OCs

OBG Management: What about newer forms of combination contraceptives such as the patch and ring?

KAUNITZ: The new practice bulletin contains information on the patch, the ring, and the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, which were not available when the earlier bulletin was prepared. In that version we talked about combination pills only.

Even so, we continue to have much more data on the Pill than the ring or patch. For that reason, until more data become available, the patch and the ring should be assumed to have the same contraindications as combination OCs. We have very little data—if any—on the use of newer combination contraceptives in high-risk women or those with medical problems.

Decisive new data on risks and benefits of hormonal contraception will change how we manage many patients. These findings prompted the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update its practice bulletin (released in June) on hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions.1 Among the most notable areas of change:

- Family history of breast cancer or BRCA1 or 2 mutations. Combination oral contraceptives (OCs) do not appear to increase the risk of breast cancer in these women, and do help prevent ovarian cancer.

- Concomitant medications. More women are using enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants for conditions other than seizure disorders; some affect steroid levels.

- Obesity. Progestin-only and intrauterine methods may be better for obese women older than 35 years, who face an elevated baseline risk of venous thromboembolism.

- Lupus. Combination OCs are safe in women with stable, mild disease who are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although bone density declines in women using DMPA, it recovers within 3 years after the drug is discontinued.

- Patch and ring. Until method-specific data come in, assume that the patch and ring have the same contraindications as combination OCs.

For the fine points on these and other findings, we talked with Dr. Andrew M. Kaunitz, who assisted ACOG with preparation of the new bulletin.1

1. Breast cancer risk

OCs do not add to existing high risk

OBG Management: Women who have a family history of breast cancer have a higher-than-average risk of developing the cancer themselves, and it is widely assumed that estrogen further heightens that risk. Should these women avoid combination OCs?

KAUNITZ: No. Although these women have been reluctant to use hormonal contraceptives (as have many caregivers), we now have several lines of reassuring evidence.

Among the studies demonstrating safety of hormonal methods in this population is the 2002 Women’s CARE study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which found no elevated risk of breast cancer in women currently or formerly using OCs, compared with women who had never used them.

This study compared 4,575 women who had breast cancer with 4,682 controls. The relative risk of breast cancer was 1.0 (95% confidence interval 0.8–1.3) among current OC users and 0.9 (0.8–1.0) among women who had previously used OCs. The relative risk did not increase consistently with higher doses or longer use.2 Nor did use of OCs add risk in women with a family history of breast cancer.2

OBG Management: An editorial accompanying that study said: “The importance of this finding for public health is enormous, because more than 75% of the women in the study had used oral contraceptives.”3

KAUNITZ: Yes, but this does not mean that women with a positive family history have no increased risk of breast cancer—they do. Rather, the use of hormonal contraceptives does not augment that risk further.

OBG Management: What about women with other high-risk factors, such as germline mutations? Do OCs increase their risk of breast cancer?

KAUNITZ: No. In the largest study to date of breast cancer risk associated with prior or current OC use in women 35 to 64 years of age with BRCA1 and 2 mutations, low-dose OC formulations did not increase it.4 In fact, OC use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers (odds ratio 0.22; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.49).4

Pill reduces risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA carriers

KAUNITZ: It is also important to remember the higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations. We now know that use of the Pill reduces ovarian cancer risk in BRCA-positive women, just as it does in the general population. In a study involving 451 women with BRCA1 or 2 mutations, who self-reported their lifetime history of OC use (or nonuse), the odds ratio for ovarian cancer associated with OC use for a minimum of 1 year was 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.53–1.36) and declined by 5% (1%–9%) with each additional year of use (P for trend=.01). Use for 6 years or more carried an odds ratio of 0.62 (0.35–1.09).5

The bottom line: Women with a family history of breast cancer in general or BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations more specifically, who have not completed childbearing or who want to avoid prophylactic mastectomy/oophorectomy, can use the Pill to prevent ovarian cancer without increasing their risk of breast cancer.5,6

2. Concomitant medications

Some drugs decrease steroid levels

Anticonvulsants

OBG Management: Many, perhaps most, women with medical conditions are already taking some kind of medication. What do ObGyns need to know about interactions between hormonal contraceptives and other medications, such as anticonvulsants and antibiotics?

KAUNITZ: We regularly encounter patients who are using anticonvulsants, both older and newer formulations.

Off-label use of anticonvulsants for indications other than seizure disorders (eg, bipolar disease) is increasing.

Levetiracetam and zonisamide. The revised practice bulletin includes pharmacokinetic data on 2 new anticonvulsants—levetiracetam7 and zonisamide.8 Fortunately, neither appears to reduce contraceptive steroid levels in women who are also taking combination OCs.

Which dosage, which method? Some widely used anticonvulsants do decrease steroid levels (TABLE 1); although some clinicians prescribe OCs containing 50 μg of ethinyl estradiol to offset the reduction, there is no evidence that this strategy is effective. The ObGyn may consider prescribing pills containing 30 to 35 μg of estradiol rather than lower doses, although again, we lack data to support this recommendation.

Another important point: Because serum steroid levels of women using progestin-only OCs and implants are lower than for combination OCs, low-dose progestin-only methods (progestin-only minipills and progestin implants) do not represent by themselves optimal contraceptives for women taking drugs (eg, anticonvulsants) that increase liver enzymes.9,10

This recommendation does not include the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraceptive effects remain high with its use, even when anticonvulsants or other liver enzyme-inducing drugs are taken.11

DMPA, a high-dose progestin contraceptive, has not been formally studied in this regard; the efficacy of this injectable contraceptive does not appear to be reduced by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.30 Interestingly enough, DMPA has anticonvulsant effects itself and therefore may represent a particularly attractive contraceptive for women taking anticonvulsants.12

TABLE 1

Some anticonvulsants reduce steroid levels in women taking OCs, and some do not

| Interaction of anticonvulsants and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants that decrease steroid levels in women taking oral contraceptives (OCs) | |

| Barbiturates (including phenobarbital and primidone) | |

| Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine | |

| Felbamate | |

| Phenytoin | |

| Topiramate | |

| Vigabatrin | |

| Anticonvulsants that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking combination OCs | |

| Ethosuximide* | Tiagabine† |

| Gabapentin† | Valproic acid |

| Lamotrigine† | Zonisamide |

| Levetiracetam | |

| * No pharmacokinetic data available. | |

| †Pharmacokinetic study used anticonvulsant dose lower than that used in clinical practice. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antibiotics

KAUNITZ: As for antibiotics, we have often been taught that many drugs lower the efficacy of combination OCs, but in fact it is not clear that they do.

Rifampin. The only antibiotic for which we have pharmacokinetic evidence of substantially lower steroid levels is rifampin13 (although anecdotal reports of OC failure in women taking other antibiotics have been noted). Therefore, any woman who is taking rifampin should be advised that OCs (combination or progestin-only), transdermal or vaginal contraceptives, and hormonal implants are inadequate birth control (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Rifampin decreases steroid levels in women taking combination OCs; other anti-infectives do not

| Interaction of anti-infective agents and combination OCs | |

|---|---|

| Anti-infective that decreases steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Rifampin | |

| Anti-infectives that do not decrease steroid levels in women taking OCs | |

| Ampicillin | Miconazole* |

| Doxycycline | Quinolone antibiotics |

| Fluconazole | Tetracycline |

| Metronidazole | |

| *Vaginal administration does not lower steroid levels in women using the contraceptive vaginal ring. | |

| Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Reprinted by permission. | |

Antiretrovirals

KAUNITZ: Several small trials suggest that contraceptive steroid levels in OC users may be affected by antiretroviral medications (TABLE 3), but we lack clinical outcome studies.

TABLE 3

Antiretrovirals may affect steroid levels in women taking OCs

| Pharmacokinetic interactions between combination OCs and antiretroviral drugs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ANTIRETROVIRAL | CONTRACEPTIVE STEROID LEVELS | ANTIRETROVIRAL LEVELS |

| PROTEASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nelfinavir | ↓ | No data |

| Ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | ↓ | No data |

| Atazanavir | ↑ | No data |

| Amprenavir | ↑ | ↓ |

| Indinavir | ↑ | No data |

| Saquinavir | No data | No change |

| NONNUCLEOSIDE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE INHIBITORS | ||

| Nevirapine | ↓ | No change |

| Efavirenz | ↑ | No change |

| Delavirdine | ?↑ | No data |

| Source: World Health Organization.29 Reprinted by permission. | ||

St. John’s wort

KAUNITZ: Another medication I want to mention is St. John’s wort, an over-the-counter hepatic enzyme inducer that many women take for depression. One clinical trial found elevated progestin and estrogen metabolism in women taking combination OCs and St. John’s wort concomitantly, as well as increased likelihood of breakthrough bleeding and ovulation.

St. John’s wort (300 mg thrice daily) was associated with a 13% to 15% reduction in the dose exposure of combination OCs containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol.14 So it is important to ask about St. John’s wort when counseling a woman about contraception.

St. John’s wort raised progestin and estrogen metabolism and increased breakthrough bleeding and ovulation in women taking OCs

3. Obesity

In obese women over 35, avoid combination OCs

OBG Management: ObGyns are seeing increasing numbers of overweight and obese women. Has selection of hormonal contraception for these women changed?

KAUNITZ: Yes. We now have a recognized obesity epidemic on our hands—and obesity, age over 35 years, and use of combination OCs all represent independent risk factors for thrombosis—prompting the question: Are there safer alternatives to combination OCs for obese women older than 35?

Tenfold risk for thromboembolism. Among the evidence addressing this question, a 2003 Dutch study found that women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 who used combination OCs had 10 times the risk of venous thromboembolism of lean controls who did not use the Pill.15

Thus, progestin-only and intrauterine contraceptive methods may be more appropriate for older obese women. This language about obesity and combination contraceptives was not in the earlier version of the practice bulletin.

No need to rule out the patch

OBG Management: Aren’t some hormonal contraceptives less effective in obese women?

KAUNITZ: In a 2002 analysis of pooled data, women in the highest weight category (≥90 kg) who were using the contraceptive patch had a higher pregnancy rate than lower-weight women.16 However, this finding does not rule out use of the patch in overweight women who prefer it to less effective methods. Rather, it should be kept in mind when counseling these patients about their options.

Although the new ACOG bulletin cites data from Holt et al17 suggesting a higher failure rate in obese women using combination OCs, other OC clinical trials have not confirmed this association.18,19 In a study by Anderson and colleagues,18 which found no pregnancies among the heaviest women, the mean weight was 155.9 lb, but ranged from 91.0 to 360.0 lb, and the mean BMI was 26.0, but ranged from 15.2 to an extreme of 56.5!

What about DMPA? We also lack evidence of higher pregnancy rates among overweight women using DMPA (150-mg intramuscular or 104-mg subcutaneous formulations).20,21

4. Lupus

OCs are an option in some women with lupus

OBG Management: As The New England Journal of Medicine observed last year, there has been an “implicit moratorium” on prescribing combination hormonal contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) because clinicians have feared that exogenous estrogens might exacerbate disease.22 This moratorium derives from data suggesting that estrogens worsen SLE, while androgens appear to protect against the condition.

The new practice bulletin now indicates that oral contraceptives are an option for this population. What is behind the change?

KAUNITZ: We now have data from 2 randomized clinical trials23,24 indicating that women can safely use combination OCs if they:

- have stable, mild disease

- are seronegative for antiphospholipid antibodies

- have no history of thrombosis

Disease remained stable. In the first trial,24 162 women with mild, stable SLE were randomized to combination OCs, progestin-only pills, or the copper IUD. Their disease level was established at baseline and over 12 months, using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index. Disease remained stable in all 3 groups.

Estrogen did not increase severity of SLE. In the second trial,23 183 women with inactive or stable active SLE were randomized to combination OCs or placebo. The primary endpoint for this trial was severe lupus flare: 7 of 91 women (7.7%) in the OC group experienced a flare, compared with 7 of 92 women (7.6%) taking placebo. Thus, estrogen does not appear to increase the severity of SLE.

OBG Management: Isn’t another concern about patients with SLE the substantial risk of thrombosis?

KAUNITZ: Yes. In the first study,24 2 thromboses occurred in women taking OCs, and 2 occurred in women using the progestin-only pill. All the women with thromboses were seropositive for antiphospholipid antibodies. Hence, we need to exclude the presence of these antibodies in women with SLE prior to prescribing combination estrogen-progestin contraception. In women with lupus and a history of thrombosis, as with all women with a history of thrombosis, we should avoid combination hormonal contraception.

In the second study,23 which compared women on combination OCs to a placebo group, the OC group experienced 1 case of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and 1 clotted graft. The placebo group experienced 1 case of DVT, 1 ocular thrombosis, 1 superficial thrombophlebitis, and 1 death (after the trial ended).

5. DMPA and bone density

DMPA does not appear to have long-term impact

OBG Management: There has been some furor over DMPA’s effect on bone mineral density (BMD). What are the latest findings in this area?

KAUNITZ: Studies assessing BMD in former DMPA users, including postmenopausal women, show that prior use of DMPA does not appear to have any long-term impact on BMD.25,26 In addition, more recent longitudinal data indicate that after DMPA is discontinued BMD fully recovers, which appears to take about 3 years in adults and as little as 1 year in teens.27,28

One population-based prospective cohort study followed 457 nongravid women aged 18 to 39 years. These women had bone density measured every 6 months for 3 years using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Although bone density decreased among DMPA users at the spine and total hip compared with nonusers, there was no difference in bone density 30 months after discontinuation of birth control injections.27

In a study of 170 adolescent women 14 to 18 years of age, 80 were DMPA users and 90 were nonusers. Bone density was measured every 6 months for 24 or 36 months, and declined significantly at the hip and spine in DMPA users. Sixty-one women discontinued DMPA during the course of the study. After discontinuation, bone density increased at all anatomical sites, recovering completely over the course of 1 year.28

Although the US Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in the fall of 2004 that use of DMPA should be reconsidered after 2 years, particularly in teens, the studies I just mentioned suggest there should be no routine restrictions on the use of DMPA in terms of skeletal health, and that DMPA use by itself is not an indication for bone density measurement.

6. Patch and ring

Assume contraindications are the same as for OCs

OBG Management: What about newer forms of combination contraceptives such as the patch and ring?

KAUNITZ: The new practice bulletin contains information on the patch, the ring, and the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, which were not available when the earlier bulletin was prepared. In that version we talked about combination pills only.

Even so, we continue to have much more data on the Pill than the ring or patch. For that reason, until more data become available, the patch and the ring should be assumed to have the same contraindications as combination OCs. We have very little data—if any—on the use of newer combination contraceptives in high-risk women or those with medical problems.

1. Use of Hormonal Contraception in Women With Coexisting Medical Conditions. ACOG Practice Bulletin #73. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

2. Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2025-2032.

3. Davidson NE, Helzlsouer KJ. Good news about oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2078-2079.

4. Milne RL, Knight JA, John EM, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of early-onset breast cancer in carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:350-356.

5. Whittemore AS, Balise RR, Pharoah PD, et al. Oral contraceptive use and ovarian cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1911-1915.

6. Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424-428.

7. Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Levy RH, Janik F. Levetiracetam does not alter the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive in healthy women. Epilepsia. 2002;43:697-702.

8. Griffith SG, Dai Y. Effect of zonisamide on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a combination ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone oral contraceptive in healthy women. Clin Ther. 2004;26:2056-2065.

9. McCann MF, Potter LS. Progestin-only oral contraception: a comprehensive review. Contraception. 1994;50(6 suppl 1):S1-S195.

10. Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

11. Bounds W, Guillebaud J. Observational series on women using the contraceptive Mirena concurrently with antiepileptic and other enzyme-inducing drugs. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;187:551-555.

12. Mattson RH, Rebar RW. Contraceptive methods for women with neurologic disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:2027-2032.

13. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, Crawford F, et al. The effect of rifampicin on norethisterone pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15:193-197.

14. Murphy PA, Kern SE, Stanczyk FZ, Westhoff CL. Interaction of St. John’s wort with oral contraceptives: effects on the pharmacokinetics of norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol, ovarian activity, and breakthrough bleeding. Contraception. 2005;71:402-408.

15. Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal F. Obesity: risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493-498.

16. Zieman M, Guillebaud J, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S13-S18.

17. Holt VL, Scholes D, Wicklund KG, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Body mass index, weight, and oral contraceptive failure risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:46-52.

18. Anderson FD. Hait H and the Seasonale-301 Study Group. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

19. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

20. Leiman G. Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive agent: its effect on weight and blood pressure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:97-102.

21. Jain J, Jakimiuk AJ, Bode FR, Ross D, Kaunitz AM. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of DMPA-SC. Contraception. 2004;70:269-275.

22. Bermas BL. Oral contraceptives in systemic lupus erythematosus—a tough pill to swallow? N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2602-2604.

23. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. OC-SELENA Trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2550-2558.

24. Sanchez-Guerrero, Urive AG, Jimenez-Santana L, et al. A trial of contraceptive methods in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2539-2549.

25. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, et al. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49:615-618.

26. Petitti DB, Piaggio G, Mehta S, Cravioto MC, Meirik O. Steroid hormone contraception and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study in an international population. The WHO Study of Hormonal Contraception and Bone Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:736-744.

27. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: results from a prospective study [published erratum appears in Epidemiology. 2002;13:749]. Epidemiology. 2002;13:581-587.

28. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, et al. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:139-144.

29. World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Annex 1. COCs and antiretroviral therapies. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

30. Sapire KE. Depo-provera and carbamazapine. Br J Fam Plann. 1990;15:130.-

Dr. Kaunitz has received funding from Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, and the National Institutes of Health. He is a speaker or consultant for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals, Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble; and holds stock with Noven, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis.

1. Use of Hormonal Contraception in Women With Coexisting Medical Conditions. ACOG Practice Bulletin #73. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

2. Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2025-2032.

3. Davidson NE, Helzlsouer KJ. Good news about oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2078-2079.

4. Milne RL, Knight JA, John EM, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of early-onset breast cancer in carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:350-356.

5. Whittemore AS, Balise RR, Pharoah PD, et al. Oral contraceptive use and ovarian cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1911-1915.

6. Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424-428.

7. Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Levy RH, Janik F. Levetiracetam does not alter the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive in healthy women. Epilepsia. 2002;43:697-702.

8. Griffith SG, Dai Y. Effect of zonisamide on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a combination ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone oral contraceptive in healthy women. Clin Ther. 2004;26:2056-2065.

9. McCann MF, Potter LS. Progestin-only oral contraception: a comprehensive review. Contraception. 1994;50(6 suppl 1):S1-S195.

10. Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

11. Bounds W, Guillebaud J. Observational series on women using the contraceptive Mirena concurrently with antiepileptic and other enzyme-inducing drugs. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;187:551-555.

12. Mattson RH, Rebar RW. Contraceptive methods for women with neurologic disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:2027-2032.

13. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, Crawford F, et al. The effect of rifampicin on norethisterone pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15:193-197.

14. Murphy PA, Kern SE, Stanczyk FZ, Westhoff CL. Interaction of St. John’s wort with oral contraceptives: effects on the pharmacokinetics of norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol, ovarian activity, and breakthrough bleeding. Contraception. 2005;71:402-408.

15. Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal F. Obesity: risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493-498.

16. Zieman M, Guillebaud J, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S13-S18.

17. Holt VL, Scholes D, Wicklund KG, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Body mass index, weight, and oral contraceptive failure risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:46-52.

18. Anderson FD. Hait H and the Seasonale-301 Study Group. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

19. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

20. Leiman G. Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive agent: its effect on weight and blood pressure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:97-102.

21. Jain J, Jakimiuk AJ, Bode FR, Ross D, Kaunitz AM. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of DMPA-SC. Contraception. 2004;70:269-275.

22. Bermas BL. Oral contraceptives in systemic lupus erythematosus—a tough pill to swallow? N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2602-2604.

23. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. OC-SELENA Trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2550-2558.

24. Sanchez-Guerrero, Urive AG, Jimenez-Santana L, et al. A trial of contraceptive methods in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2539-2549.

25. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, et al. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49:615-618.

26. Petitti DB, Piaggio G, Mehta S, Cravioto MC, Meirik O. Steroid hormone contraception and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study in an international population. The WHO Study of Hormonal Contraception and Bone Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:736-744.

27. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: results from a prospective study [published erratum appears in Epidemiology. 2002;13:749]. Epidemiology. 2002;13:581-587.

28. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, et al. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:139-144.

29. World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Annex 1. COCs and antiretroviral therapies. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

30. Sapire KE. Depo-provera and carbamazapine. Br J Fam Plann. 1990;15:130.-

Dr. Kaunitz has received funding from Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, and the National Institutes of Health. He is a speaker or consultant for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals, Barr Laboratories, Berlex, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble; and holds stock with Noven, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis.

HYSTEROSCOPIC STERILIZATION

With over 50,000 completed hysteroscopic sterilization procedures worldwide, and 5 years of data, what do we know so far about this innovation? It is now almost 4 years since the FDA approved Essure (Conceptus; San Carlos, Calif), the first hysteroscopic sterilization method available for use in the United States. Two other systems are in the works: Adiana (Adiana; Redwood City, Calif) has completed its Phase III clinical trial and Ovion (American Medical Systems; Minnetonka, Minn) is just beginning its clinical trial this year.

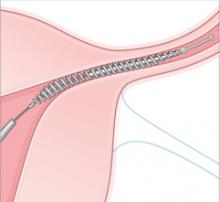

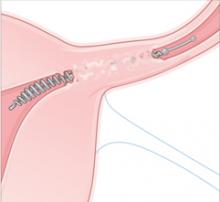

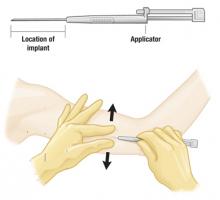

Comparison of the devices

Essure is a disposable delivery system with polyethylene (PET) fibers wound in and around a stainless steel inner coil. An outer coil of nitinol, a superelastic titanium/nickel alloy, is deployed to anchor the device across the uterotubal junction. Wound down, the micro-insert is 0.8 mm in diameter. Once released, the coil expands to 1.5 to 2.0 mm to hold the inner coil and PET fibers in place at the uterine cornua.

Over a period of about 3 months, the PET fibers elicit tissue ingrowth and proximal tubal occlusion. Women must use additional contraception during this time. Documentation of occlusion by a hysterosalpingogram about 3 months after device placement is required before patients may rely on the device and stop birth control.

Adiana (not yet available in the United States) uses a combination of controlled epithelial destruction and insertion of a porous biomatrix to induce vascularized tissue ingrowth. A catheter placed through the operating channel of a small hysteroscope delivers low-power bipolar electrosurgical energy to the tubal orifice (average less than 1 watt to the endosalpinx). A pushrod then delivers a small porous matrix of material into the tubal lumen. Ingrowth of healthy, vascularized tissue occurs over approximately 3 months, to occlude the tubes.

Retention of the matrix and tubal occlusion are documented by both transvaginal ultrasonography and hysterosalpingogram before patients may discontinue additional contraception.

Accessing the tubes

One of the greatest hurdles for occluding the fallopian tubes hysteroscopically is access to the tubes. Both the Adiana clinical trial (not yet published) and the post-market analysis of Essure (not yet published) have demonstrated excellent bilateral placement rates.

Technique is not hard to learn. Both types of devices are inserted through the operating channel of a small hysteroscope. Initial concerns about the ability to access the tubal ostia do not appear to be an issue—at least for those early-adopter physicians performing the procedures. Both clinical trials included gynecologists who were not experienced in operative hysteroscopy. These studies found that cannulation of the tubes is a technique that is easy to learn and rapidly accomplished in most circumstances.

Bilateral placement rates were similar for both devices in the pivotal trials: Adiana 95% (612/655); Essure 90% (464/518).

What are the contraindications?

Approximately 10% of patients have factors that preclude bilateral device placement:

Anatomic factors

- Blocked or stenotic tubes

- Intrauterine adhesions

- Visual field obstructed by polyps, fibroids, or shaggy endometrium

- Lateral tubes

Device or procedure failures due to

- Tubal spasm

- Patient pain/intolerance

- Device malfunction

A second procedure (after correcting the initial problems) will be successful in many women who have what appears to be a technical glitch.

Clinical outcomes, so far

Ultimately, of course, the success of these procedures and the benefits to our patients will be determined by the placement rates in the real world and the ability of a majority of women to rely on the devices for permanent sterilization.

What can we say so far?

Bilateral placement rates

Although the bilateral placement rates for Essure in the pivotal trial were 88% with one attempt, increasing to 92% of all patients enrolled with a second attempt, the data from the postmarket study is even more promising. After FDA approval in November 2002, the manufacturer trained gynecologists in the procedure, and then monitored clinical outcomes in the initial cases performed by these surgeons once they had completed their training and mandatory proctored cases (data not yet published).

Physicians who participated in the clinical trial were excluded from this analysis. The bilateral device placement rate for these women treated by novice users is over 94%. Adiana’s Phase III trial data demonstrate a similar bilateral success rate. It appears that despite the misgivings of many ObGyns, these systems are easy to learn.

I have incorporated the following tips and tricks into my office practice with great results. Patients are thrilled with their experience and leave ready to recruit their friends for the procedure.

- Pretreatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug to block prostaglandin release and uterotubal spasm

- Scheduling the procedure for the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle to minimize shaggy endometrium, or

- Suppressing the endometrium with progestins from the first day of menses until the scheduled procedure

- Use of warm fluid for uterine distension to reduce spasm

- Placement of topical lidocaine gel into the uterus 10 to 15 minutes prior to the procedure

- Use of a pressure bag to assure adequate uterine distension

Patient safety

Few complications have been reported with either technique. There were the expected rare vasovagal reactions, as well as 2 cases of hypervolemia with Essure and 1 case of hyponatremia in the Adiana trial. Both of these situations should be avoidable with proper monitoring and limiting distension fluids to isotonic solutions. All patients recovered fully. There were no problems with persistent pain or changes in menstrual patterns at 1 year in the Essure trial.

Expulsion of the devices was associated with proximal positioning of the devices in all cases (3%). Patients had no symptoms, and most were able to have a second procedure with excellent placement and retention. Expulsions were identified at the postprocedure scout film or hysterosalpingogram.

Tubal perforation was noted in 0.9% of the patients. Predisposing factors were preexisting tubal occlusion or hydrosalpinx.

Perforations were asymptomatic, as well. Laparoscopic evaluation in 3 cases demonstrated no adhesions or reactions to the tiny perforation sites.

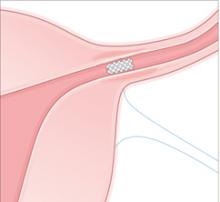

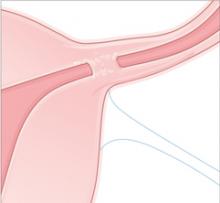

Delivery. An outer coil of nitinol, a superelastic titanium/nickel alloy is deployed to anchor the device across the uterotubal junction. Once released, the coil expands to 1.5 to 2.0 mm to hold the inner coil and PET fibers in place at the uterine cornua.

Occlusion. Over about 3 months, the PET fibers elicit tissue ingrowth and proximal tubal occlusion. Women must use additional contraception during this time. Documentation of occlusion by a hysterosalpingogram is required before patients may discontinue additional contraception.

Images: Rich Larocco