User login

Alendronate Therapy and Renal Insufficiency: A Prescription for Problems?

ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

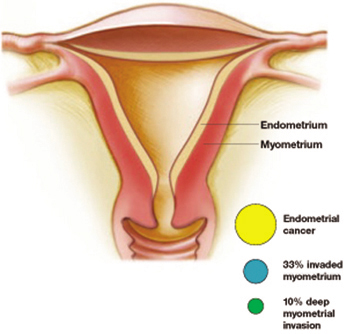

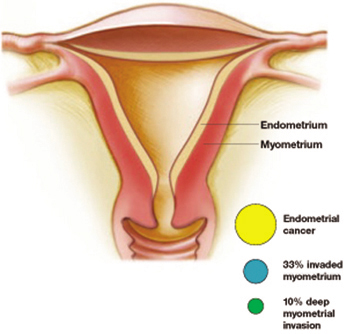

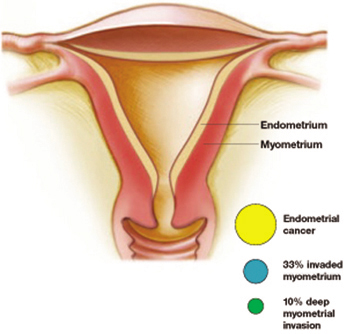

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

How to divorce a difficult patient and live happily ever after

You need not despair if you’re confronted with a patient who disrupts your practice. You have every right to discharge her. But once a physician-patient relationship is established, you must terminate the relationship officially, to end your obligation. An orderly dismissal does not abandon your patient, and minimizes potential for legal problems.

Although difficult patients may be uncommon in your practice, it is unwise to give no thought to the possibility, and to have no plan to handle the situation. Protect yourself and your practice by following a consistent path with difficult patients, and seek legal counsel when faced with an unusual situation.

Difficult patients aren’t the only ones you may need to dismiss. You may have to dismiss patients because you are retiring or discontinuing your participation with an insurance company.

…chronically skip key appointments

You know that Kimberly means well, but she has a history of failing to keep her appointments. Your last encounter was a consult at the hospital, where she left against medical advice, as reported to you by her admitting physician. A recent positive test result has you concerned, particularly because she did not show up for 3 visits you’ve scheduled to discuss her care.

…never pay

You’ve delivered 2 of Julie’s babies, and now she’s on the schedule for her preventive gynecological care this afternoon. While you’re grabbing a bite of lunch, your manager comes in to let you know that Julie has never paid you a dime—for three years’ running, despite dozens of statements, phone calls and requests for payments at the front office.

…verbally abuse your staff

Sally has verbally abused your staff on multiple occasions since she became your patient several years ago. She often brings her partner, whom you’ve observed to be ill-tempered with staff. Although they’re pleasant to you when you walk into the room, their behavior is such that your staff refuses to provide nursing assistance any longer.

First, call your liability insurance carrier

Using your professional liability insurance carrier as an adviser is critical. In sensitive situations, such as a patient who displays disruptive behavior, and whom you believe may be litigious, consult the risk management department before a dismissal. Your carrier knows your state’s laws on terminating the patient-physician relationship.

Check insurance contracts

Although most health insurance contracts do not state dismissal terms, they can stipulate anything. HMOs often require specific procedures. If you’ve signed such a contract, you’ll need to be aware of and follow the rules before a situation comes up. Examples: Some payers require a period of time (eg, 90 days) before dismissal, and some require notification first, so that they can counsel the beneficiary.

In future contracting, negotiate for terms that are friendly to your practice, not just to the insurance company.

Warning signs

Difficult patients tend to:

- Fail to make payment arrangements according to normal practices

- Fail to comply with a recommended plan of care, including subsequent appointments

- Display disruptive or violent behavior in the practice (or the patient’s partner is disruptive or violent)

- Leave the hospital against medical advice

- Threaten lawsuits

- Abuse drugs or controlled substances

Put your policy in writing and practice it consistently

Your dismissal policy—and the reasons and protocols your practice follows—must be in writing. Decide what constitutes a reason for dismissal and make sure you apply your own rules consistently.

Do not discriminate or appear to discriminate

As a physician, you have the right to terminate a difficult patient from your practice. Exceptions are dismissals based on ethnicity, gender, religion, or age. If you apply your dismissal policy inconsistently, your actions could be considered discriminatory. For example, do not terminate one patient for failure to pay her $500 debt while ignoring another patient’s past-due balance.

Document, document, document

Document in the patient’s medical record any verbal or written communication to and from the patient. This is especially important in the case of a noncompliant patient. Record every instance, for example, of a patient who fails to show up for her appointment. Record your attempts to contact her to reschedule, and notate the consequences of her failure to keep the appointment.

No-shows are dangerous

Although no-show abuse is rampant for many practices, be careful about continuing to treat these patients without taking some action. Let’s say, for example, you notify a patient of a positive Pap smear and recommend a colposcopy. The patient cancels her first colposcopy and fails to show for the rescheduled procedure. You document your multiple attempts to contact the patient.

If the patient continues to schedule appointments and fails to show up for them, contact your malpractice carrier for advice. This patient will likely have a serious medical problem in the future, and you do not want to get tied up in a lawsuit claiming abandonment. Although it may be tedious, thorough documentation of your actions prior to dismissal will pay off in the long run. Include in the record when you communicated to the patient and what you told her regarding the consequences of her failure to present for her appointment.

Dismissal for nonpayment

In the case of nonpayment—the most common cause for dismissal—consider dismissal if the patient refuses to work out payment arrangements.

Consider offering the option of continued treatment on the basis of payment of past debts and future payment prior to service. It is standard practice to offer to allow the patient to return if she abides by this arrangement.

Threats and violence

Call local authorities immediately if a patient makes a threat or displays violent physical behavior. Stop short of broadcasting the situation to other area ObGyns, because that is the responsibility of the police.

When you have dealt with a violent or abusive patient, ask authorities to advise other physicians who may be affected.

You may immediately dismiss a patient when there is a threat or perceived threat of violence. Otherwise, follow the steps of a consistent process to terminate a patient.

Pre-dismissal strategy to avert allegations

The goal of the dismissal process is to terminate your patient-physician relationship while avoiding an allegation of abandonment or discrimination.

Consider alternatives

If the patient is in the course of treatment for a medical condition that requires physician supervision, such as an obstetrics patient or a postoperative gynecologic surgery patient, consider alternatives before dismissing her.

- Can you treat her during the course of the condition and dismiss her afterwards?

- Can you contact a community agency for assistance if, for example, the reason for her failure to show up for appointments is transportation or childcare challenges?

If you have no alternatives but still want to dismiss a patient during a specific course of treatment, seek counsel from your malpractice carrier.

Ask her about correcting the problem

Before dismissing a patient, attempt to communicate with her directly. Discuss your concerns. Document your conversation and her reactions. Proceed with the termination unless she assures you that she will alter her actions. This is optional, and certainly not recommended for a violent patient or one who has a violent partner. However, open communication is suggested because it can help avoid angering the patient. An angry patient may be more likely to sue, especially if she had been unaware of your intention or reasons to dismiss her.

If the cause for dismissal is noncompliance with your recommended treatment, document the recommendations and conversations in detail. Include the recommended treatment plan, her objections, and your statement of the consequences of her failure to comply. In the case of an adverse event, documentation may be crucial.

You may receive a transfer of medical records that includes a dismissal letter for a reason that causes you concern. You are not obligated to treat that patient if you have not yet established a relationship. The establishment normally occurs at the first appointment.

All the same, it’s wise to contact your malpractice carrier about any state laws that would impact the initiation of the patient-physician relationship and how you should handle refusing to treat a patient.

- The letter of dismissal (Sample letter) Outline in the letter the reason(s) for the dismissal. Be objective. Stating subjective reasons for dismissal may open the door for a case of abandonment on the basis of discrimination.

- How to handle the referral Include a copy of your medical records transfer request with your letter. When possible, include a referral source such as your medical society or hospital referral center. Do not refer her to a specific physician.

- How to handle the mailing Mail the letter with a return receipt requested. Patients may refuse a letter sent with receipt requested, so also send a copy by regular mail. Copy the letter and record the date and method by which the letters were sent. Keep the return receipt (or record of refusal) in the patient’s record.

- Consider 30-day continuance Most physicians allow 30 days to establish a relationship with another provider, and limit care during this time to acute needs only—but sensitivity to the patient’s situation is wise. Although 30 days typically suffice, check with your malpractice carrier if you are concerned about the patient’s condition or availability of other ObGyns.

- Specify termination of services In your written communication, outline what services you will provide until she locates another provider.

Be sure to indicate a specific termination date—30 days following the date of the dismissal letter is recommended.

A special thank you to Pam Hutcherson, RN, LNC, Risk Management Specialist, State Volunteer Mutual Insurance Company of Brentwood, Tennessee, who reviewed this article.

Atlanta-based Elizabeth W. Woodcock is a speaker, trainer, and author specializing in practice management. Among her recent books are Mastering Patient Flow.

You need not despair if you’re confronted with a patient who disrupts your practice. You have every right to discharge her. But once a physician-patient relationship is established, you must terminate the relationship officially, to end your obligation. An orderly dismissal does not abandon your patient, and minimizes potential for legal problems.

Although difficult patients may be uncommon in your practice, it is unwise to give no thought to the possibility, and to have no plan to handle the situation. Protect yourself and your practice by following a consistent path with difficult patients, and seek legal counsel when faced with an unusual situation.

Difficult patients aren’t the only ones you may need to dismiss. You may have to dismiss patients because you are retiring or discontinuing your participation with an insurance company.

…chronically skip key appointments

You know that Kimberly means well, but she has a history of failing to keep her appointments. Your last encounter was a consult at the hospital, where she left against medical advice, as reported to you by her admitting physician. A recent positive test result has you concerned, particularly because she did not show up for 3 visits you’ve scheduled to discuss her care.

…never pay

You’ve delivered 2 of Julie’s babies, and now she’s on the schedule for her preventive gynecological care this afternoon. While you’re grabbing a bite of lunch, your manager comes in to let you know that Julie has never paid you a dime—for three years’ running, despite dozens of statements, phone calls and requests for payments at the front office.

…verbally abuse your staff

Sally has verbally abused your staff on multiple occasions since she became your patient several years ago. She often brings her partner, whom you’ve observed to be ill-tempered with staff. Although they’re pleasant to you when you walk into the room, their behavior is such that your staff refuses to provide nursing assistance any longer.

First, call your liability insurance carrier

Using your professional liability insurance carrier as an adviser is critical. In sensitive situations, such as a patient who displays disruptive behavior, and whom you believe may be litigious, consult the risk management department before a dismissal. Your carrier knows your state’s laws on terminating the patient-physician relationship.

Check insurance contracts

Although most health insurance contracts do not state dismissal terms, they can stipulate anything. HMOs often require specific procedures. If you’ve signed such a contract, you’ll need to be aware of and follow the rules before a situation comes up. Examples: Some payers require a period of time (eg, 90 days) before dismissal, and some require notification first, so that they can counsel the beneficiary.

In future contracting, negotiate for terms that are friendly to your practice, not just to the insurance company.

Warning signs

Difficult patients tend to:

- Fail to make payment arrangements according to normal practices

- Fail to comply with a recommended plan of care, including subsequent appointments

- Display disruptive or violent behavior in the practice (or the patient’s partner is disruptive or violent)

- Leave the hospital against medical advice

- Threaten lawsuits

- Abuse drugs or controlled substances

Put your policy in writing and practice it consistently

Your dismissal policy—and the reasons and protocols your practice follows—must be in writing. Decide what constitutes a reason for dismissal and make sure you apply your own rules consistently.

Do not discriminate or appear to discriminate

As a physician, you have the right to terminate a difficult patient from your practice. Exceptions are dismissals based on ethnicity, gender, religion, or age. If you apply your dismissal policy inconsistently, your actions could be considered discriminatory. For example, do not terminate one patient for failure to pay her $500 debt while ignoring another patient’s past-due balance.

Document, document, document

Document in the patient’s medical record any verbal or written communication to and from the patient. This is especially important in the case of a noncompliant patient. Record every instance, for example, of a patient who fails to show up for her appointment. Record your attempts to contact her to reschedule, and notate the consequences of her failure to keep the appointment.

No-shows are dangerous

Although no-show abuse is rampant for many practices, be careful about continuing to treat these patients without taking some action. Let’s say, for example, you notify a patient of a positive Pap smear and recommend a colposcopy. The patient cancels her first colposcopy and fails to show for the rescheduled procedure. You document your multiple attempts to contact the patient.

If the patient continues to schedule appointments and fails to show up for them, contact your malpractice carrier for advice. This patient will likely have a serious medical problem in the future, and you do not want to get tied up in a lawsuit claiming abandonment. Although it may be tedious, thorough documentation of your actions prior to dismissal will pay off in the long run. Include in the record when you communicated to the patient and what you told her regarding the consequences of her failure to present for her appointment.

Dismissal for nonpayment

In the case of nonpayment—the most common cause for dismissal—consider dismissal if the patient refuses to work out payment arrangements.

Consider offering the option of continued treatment on the basis of payment of past debts and future payment prior to service. It is standard practice to offer to allow the patient to return if she abides by this arrangement.

Threats and violence

Call local authorities immediately if a patient makes a threat or displays violent physical behavior. Stop short of broadcasting the situation to other area ObGyns, because that is the responsibility of the police.

When you have dealt with a violent or abusive patient, ask authorities to advise other physicians who may be affected.

You may immediately dismiss a patient when there is a threat or perceived threat of violence. Otherwise, follow the steps of a consistent process to terminate a patient.

Pre-dismissal strategy to avert allegations

The goal of the dismissal process is to terminate your patient-physician relationship while avoiding an allegation of abandonment or discrimination.

Consider alternatives

If the patient is in the course of treatment for a medical condition that requires physician supervision, such as an obstetrics patient or a postoperative gynecologic surgery patient, consider alternatives before dismissing her.

- Can you treat her during the course of the condition and dismiss her afterwards?

- Can you contact a community agency for assistance if, for example, the reason for her failure to show up for appointments is transportation or childcare challenges?

If you have no alternatives but still want to dismiss a patient during a specific course of treatment, seek counsel from your malpractice carrier.

Ask her about correcting the problem

Before dismissing a patient, attempt to communicate with her directly. Discuss your concerns. Document your conversation and her reactions. Proceed with the termination unless she assures you that she will alter her actions. This is optional, and certainly not recommended for a violent patient or one who has a violent partner. However, open communication is suggested because it can help avoid angering the patient. An angry patient may be more likely to sue, especially if she had been unaware of your intention or reasons to dismiss her.

If the cause for dismissal is noncompliance with your recommended treatment, document the recommendations and conversations in detail. Include the recommended treatment plan, her objections, and your statement of the consequences of her failure to comply. In the case of an adverse event, documentation may be crucial.

You may receive a transfer of medical records that includes a dismissal letter for a reason that causes you concern. You are not obligated to treat that patient if you have not yet established a relationship. The establishment normally occurs at the first appointment.

All the same, it’s wise to contact your malpractice carrier about any state laws that would impact the initiation of the patient-physician relationship and how you should handle refusing to treat a patient.

- The letter of dismissal (Sample letter) Outline in the letter the reason(s) for the dismissal. Be objective. Stating subjective reasons for dismissal may open the door for a case of abandonment on the basis of discrimination.

- How to handle the referral Include a copy of your medical records transfer request with your letter. When possible, include a referral source such as your medical society or hospital referral center. Do not refer her to a specific physician.

- How to handle the mailing Mail the letter with a return receipt requested. Patients may refuse a letter sent with receipt requested, so also send a copy by regular mail. Copy the letter and record the date and method by which the letters were sent. Keep the return receipt (or record of refusal) in the patient’s record.

- Consider 30-day continuance Most physicians allow 30 days to establish a relationship with another provider, and limit care during this time to acute needs only—but sensitivity to the patient’s situation is wise. Although 30 days typically suffice, check with your malpractice carrier if you are concerned about the patient’s condition or availability of other ObGyns.

- Specify termination of services In your written communication, outline what services you will provide until she locates another provider.

Be sure to indicate a specific termination date—30 days following the date of the dismissal letter is recommended.

A special thank you to Pam Hutcherson, RN, LNC, Risk Management Specialist, State Volunteer Mutual Insurance Company of Brentwood, Tennessee, who reviewed this article.

You need not despair if you’re confronted with a patient who disrupts your practice. You have every right to discharge her. But once a physician-patient relationship is established, you must terminate the relationship officially, to end your obligation. An orderly dismissal does not abandon your patient, and minimizes potential for legal problems.

Although difficult patients may be uncommon in your practice, it is unwise to give no thought to the possibility, and to have no plan to handle the situation. Protect yourself and your practice by following a consistent path with difficult patients, and seek legal counsel when faced with an unusual situation.

Difficult patients aren’t the only ones you may need to dismiss. You may have to dismiss patients because you are retiring or discontinuing your participation with an insurance company.

…chronically skip key appointments

You know that Kimberly means well, but she has a history of failing to keep her appointments. Your last encounter was a consult at the hospital, where she left against medical advice, as reported to you by her admitting physician. A recent positive test result has you concerned, particularly because she did not show up for 3 visits you’ve scheduled to discuss her care.

…never pay

You’ve delivered 2 of Julie’s babies, and now she’s on the schedule for her preventive gynecological care this afternoon. While you’re grabbing a bite of lunch, your manager comes in to let you know that Julie has never paid you a dime—for three years’ running, despite dozens of statements, phone calls and requests for payments at the front office.

…verbally abuse your staff

Sally has verbally abused your staff on multiple occasions since she became your patient several years ago. She often brings her partner, whom you’ve observed to be ill-tempered with staff. Although they’re pleasant to you when you walk into the room, their behavior is such that your staff refuses to provide nursing assistance any longer.

First, call your liability insurance carrier

Using your professional liability insurance carrier as an adviser is critical. In sensitive situations, such as a patient who displays disruptive behavior, and whom you believe may be litigious, consult the risk management department before a dismissal. Your carrier knows your state’s laws on terminating the patient-physician relationship.

Check insurance contracts

Although most health insurance contracts do not state dismissal terms, they can stipulate anything. HMOs often require specific procedures. If you’ve signed such a contract, you’ll need to be aware of and follow the rules before a situation comes up. Examples: Some payers require a period of time (eg, 90 days) before dismissal, and some require notification first, so that they can counsel the beneficiary.

In future contracting, negotiate for terms that are friendly to your practice, not just to the insurance company.

Warning signs

Difficult patients tend to:

- Fail to make payment arrangements according to normal practices

- Fail to comply with a recommended plan of care, including subsequent appointments

- Display disruptive or violent behavior in the practice (or the patient’s partner is disruptive or violent)

- Leave the hospital against medical advice

- Threaten lawsuits

- Abuse drugs or controlled substances

Put your policy in writing and practice it consistently

Your dismissal policy—and the reasons and protocols your practice follows—must be in writing. Decide what constitutes a reason for dismissal and make sure you apply your own rules consistently.

Do not discriminate or appear to discriminate

As a physician, you have the right to terminate a difficult patient from your practice. Exceptions are dismissals based on ethnicity, gender, religion, or age. If you apply your dismissal policy inconsistently, your actions could be considered discriminatory. For example, do not terminate one patient for failure to pay her $500 debt while ignoring another patient’s past-due balance.

Document, document, document

Document in the patient’s medical record any verbal or written communication to and from the patient. This is especially important in the case of a noncompliant patient. Record every instance, for example, of a patient who fails to show up for her appointment. Record your attempts to contact her to reschedule, and notate the consequences of her failure to keep the appointment.

No-shows are dangerous

Although no-show abuse is rampant for many practices, be careful about continuing to treat these patients without taking some action. Let’s say, for example, you notify a patient of a positive Pap smear and recommend a colposcopy. The patient cancels her first colposcopy and fails to show for the rescheduled procedure. You document your multiple attempts to contact the patient.

If the patient continues to schedule appointments and fails to show up for them, contact your malpractice carrier for advice. This patient will likely have a serious medical problem in the future, and you do not want to get tied up in a lawsuit claiming abandonment. Although it may be tedious, thorough documentation of your actions prior to dismissal will pay off in the long run. Include in the record when you communicated to the patient and what you told her regarding the consequences of her failure to present for her appointment.

Dismissal for nonpayment

In the case of nonpayment—the most common cause for dismissal—consider dismissal if the patient refuses to work out payment arrangements.

Consider offering the option of continued treatment on the basis of payment of past debts and future payment prior to service. It is standard practice to offer to allow the patient to return if she abides by this arrangement.

Threats and violence

Call local authorities immediately if a patient makes a threat or displays violent physical behavior. Stop short of broadcasting the situation to other area ObGyns, because that is the responsibility of the police.

When you have dealt with a violent or abusive patient, ask authorities to advise other physicians who may be affected.

You may immediately dismiss a patient when there is a threat or perceived threat of violence. Otherwise, follow the steps of a consistent process to terminate a patient.

Pre-dismissal strategy to avert allegations

The goal of the dismissal process is to terminate your patient-physician relationship while avoiding an allegation of abandonment or discrimination.

Consider alternatives

If the patient is in the course of treatment for a medical condition that requires physician supervision, such as an obstetrics patient or a postoperative gynecologic surgery patient, consider alternatives before dismissing her.

- Can you treat her during the course of the condition and dismiss her afterwards?

- Can you contact a community agency for assistance if, for example, the reason for her failure to show up for appointments is transportation or childcare challenges?

If you have no alternatives but still want to dismiss a patient during a specific course of treatment, seek counsel from your malpractice carrier.

Ask her about correcting the problem

Before dismissing a patient, attempt to communicate with her directly. Discuss your concerns. Document your conversation and her reactions. Proceed with the termination unless she assures you that she will alter her actions. This is optional, and certainly not recommended for a violent patient or one who has a violent partner. However, open communication is suggested because it can help avoid angering the patient. An angry patient may be more likely to sue, especially if she had been unaware of your intention or reasons to dismiss her.

If the cause for dismissal is noncompliance with your recommended treatment, document the recommendations and conversations in detail. Include the recommended treatment plan, her objections, and your statement of the consequences of her failure to comply. In the case of an adverse event, documentation may be crucial.

You may receive a transfer of medical records that includes a dismissal letter for a reason that causes you concern. You are not obligated to treat that patient if you have not yet established a relationship. The establishment normally occurs at the first appointment.

All the same, it’s wise to contact your malpractice carrier about any state laws that would impact the initiation of the patient-physician relationship and how you should handle refusing to treat a patient.

- The letter of dismissal (Sample letter) Outline in the letter the reason(s) for the dismissal. Be objective. Stating subjective reasons for dismissal may open the door for a case of abandonment on the basis of discrimination.

- How to handle the referral Include a copy of your medical records transfer request with your letter. When possible, include a referral source such as your medical society or hospital referral center. Do not refer her to a specific physician.

- How to handle the mailing Mail the letter with a return receipt requested. Patients may refuse a letter sent with receipt requested, so also send a copy by regular mail. Copy the letter and record the date and method by which the letters were sent. Keep the return receipt (or record of refusal) in the patient’s record.

- Consider 30-day continuance Most physicians allow 30 days to establish a relationship with another provider, and limit care during this time to acute needs only—but sensitivity to the patient’s situation is wise. Although 30 days typically suffice, check with your malpractice carrier if you are concerned about the patient’s condition or availability of other ObGyns.

- Specify termination of services In your written communication, outline what services you will provide until she locates another provider.

Be sure to indicate a specific termination date—30 days following the date of the dismissal letter is recommended.

A special thank you to Pam Hutcherson, RN, LNC, Risk Management Specialist, State Volunteer Mutual Insurance Company of Brentwood, Tennessee, who reviewed this article.

Atlanta-based Elizabeth W. Woodcock is a speaker, trainer, and author specializing in practice management. Among her recent books are Mastering Patient Flow.

Atlanta-based Elizabeth W. Woodcock is a speaker, trainer, and author specializing in practice management. Among her recent books are Mastering Patient Flow.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Evaluating Hyperprolactinemia in Veterans

How Veterans Use Stroke Services in the VA and Beyond

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

For the 2006 Update, I have chosen to focus on 3 important new clinical reports that stand to improve patient care, and another development that necessitates a change in how we treat gonorrhea in pregnant women:

CMV vaccine. A new immunologic agent for the treatment and prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is extremely promising. Until now, no consistently effective therapy for this serious congenital infection has been identified.

- Recommended hygiene measures to prevent transmission—Page 64

Outpatient treatment of PID. Relatively inexpensive outpatient therapy for mild to moderately severe pelvic inflammatory disease was demonstrated to be equal to inpatient therapy in efficacy and safety.

- Whom to hospitalize—Page 68

Wound complications after cesarean delivery in the obese were reduced by use of subcutaneous closure and avoidance of surgical drains.

- Recommended technique—Page 70

2 antibiotics with unique application in the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections in pregnant women—cefixime and spectinomycin—were recently withdrawn from the market. This unfortunate development is a special dilemma in pregnant women with allergy to beta-lactams.

- Alternative regimens, using other antibiotics—Page 75

A promising therapy for congenital CMV

For now, emphasize prevention

Nigro G, Adler SP, LaTorre R, Best AM. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1350–1362.

- Although anti-cytomegalovirus hyperimmune globulin appears to have great promise for prevention and treatment of congenital CMV infection, I propose that obstetricians avoid a rush to judgment and maintain their focus on simple measures to prevent horizontal transmission of CMV

Summary

Nigro and colleagues present a provocative report of a promising new treatment for congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Their prospective cohort study at 8 Italian medical centers involved 157 pregnant women with confirmed primary CMV infection: 148 women were asymptomatic and were identified by routine serologic screening; 8 had symptomatic infections and 1 had ultrasound findings consistent with congenital CMV infection.

CMV was detected in the amniotic fluid of 45 women who had a primary infection more than 6 weeks before enrollment, and 31 of these women agreed to receive CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin (200 units per kilogram of maternal body weight). Nine of the 31 women received 1 or 2 additional infusions into either the amniotic fluid or umbilical cord because of persistent fetal abnormalities on ultrasound.

- Only 1 of the 31 treated women delivered an infected infant (adjusted odds ratio, 0.02; P<.001).

- In contrast, of the 14 women who declined treatment, 7 had infants who were symptomatically infected at birth.

There were 84 additional women who did not have an amniocentesis because their infection occurred within 6 weeks of enrollment, their gestational age was less than 20 weeks, or they declined the procedure. Of these, 37 agreed to treatment with 100 U of hyperimmune globulin per kilogram of maternal weight every month until delivery.

- 6 of these treated women delivered infected infants.

- In contrast, 19 of the untreated women (adjusted odds ratio 0.32; P=.04) delivered infected infants.

No adverse effects of hyperimmune globulin were noted in either treatment group.

Commentary

This study is remarkable because, until now, no consistently effective therapy for this serious congenital infection has been available. However, before we fully embrace the findings, 3 caveats should be considered.1

- Although the study was prospective, it was neither randomized nor controlled. The lack of strict randomization resulted in a curious blend of 2 cohorts—a treatment group and a prevention group. The dosage regimens were different both within and between the 2 groups.

- There are biological reasons to question the remarkable success rates reported by the authors. For example, administration of anti-HIV hyperimmune globulin has not protected neonates against perinatal transmission of HIV.2 Moreover, the presence of naturally acquired antibody against CMV does not fully protect a mother or her fetus against reactivation and subsequent perinatal transmission of CMV infection.1 This latter observation is particularly important in assessing the authors’ observations that major abnormalities identified by ultrasound, such as ascites, ventriculomegaly, intracerebral and intraabdominal echodensities, and intrauterine growth restriction apparently resolved completely in 14 fetuses after maternal treatment.

- The study did not address the financial and logistic issues of screening large obstetric populations for CMV infection, triaging patients with inevitable false-positive test results, performing targeted sonography and amniocentesis in affected women, and then treating at-risk women with hyperimmune globulin.

Recommendations

Hyperimmune globulin appears to be very safe and to have great promise for treatment and prevention of congenital CMV infection. However, additional investigations are needed to delineate the appropriate dose, method of administration, and timing of immunoprophylaxis and to define its precise level of effectiveness.

Meanwhile, focus on simple hygiene measures

Until confirmatory studies are reported, I propose that obstetricians avoid a rush to judgment and maintain their focus on simple measures to prevent horizontal transmission of CMV, such as:

- using CMV-negative blood products when transfusing pregnant women or fetuses

- encouraging expectant mothers to adopt safe sex practices

- encouraging expectant mothers to use careful handwashing techniques after handling infants’ diapers and toys.

Outpatient treatment of PID is effective, safe, and economical

Fertility and recurrence rates similar to inpatient therapy

Ness RB, Trautmann G, Richter HE, Randall H, Peipert JF, Nelson DB, et al. Effectiveness of treatment strategies of some women with pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:573–580.

- Outpatient treatment is an effective and economically attractive alternative to inpatient therapy for women with mild to moderately severe pelvic inflammatory disease

Summary

Relatively inexpensive outpatient therapy for mild to moderately severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) proved effective and equivalent to inpatient treatment in key respects, in this long-term follow-up study.

Ness and colleagues describe 831 patients who had participated in a prospective, randomized, unblinded multicenter trial of outpatient versus inpatient treatment for mild-to-moderate PID.3 The patients were followed for a mean of 84 months (range 64–100 months).

- The inpatient treatment group received intravenous cefoxitin (2 grams every 6 hours) and either intravenous or oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) for at least 72 hours, followed by oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) to complete a 14-day course.

- The outpatient treatment group received a single 2-g intramuscular injection of cefoxitin plus a single 1-g oral dose of probenecid, followed by oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) for 14 days.

Equivalent outcomes

Outpatient treatment did not adversely affect subsequent fertility or increase the frequency of recurrent PID or chronic pelvic pain. The equivalence of outpatient compared with inpatient therapy extended to women of all races and to those with a history of PID; those colonized by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and/or Chlamydia trachomatis; and those with a high temperature, high white count, and high pelvic tenderness score.

Even in teenage women and women who had never had a live birth, outpatient and inpatient therapy were equivalent.

Risk of ectopic pregnancy was increased in outpatients (odds ratio 4.91); however, ectopic pregnancy was such a rare event that the 95% confidence interval was quite wide, ranging from 0.57 to 42.25.

Commentary

The initial encouraging results of the authors’ 2002 landmark Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Randomized Trial3 led to this long-term follow-up study. In the women who were treated as described above, the short-term clinical outcomes and markers of micro-biologic improvement were similar in the outpatient and inpatient groups. After a mean follow-up of 35 months, pregnancy rates were essentially equal (42%) in both groups. Moreover, the groups did not differ significantly in risk of recurrent PID, chronic pelvic pain, or ectopic pregnancy.

Extended follow-up is reassuring

PID, a common and potentially serious illness, is the single most common predisposing factor for ectopic pregnancy and one of the principal causes of infertility and chronic pelvic pain. The direct and indirect expenses of PID are enormous, and the PEACH trial provides great reassurance that women who are not seriously ill can be safely, effectively, and inexpensively treated as outpatients.

The additional 4 years of follow-up reassures us that outpatient treatment did not adversely affect long-term outcome. Moreover, outpatient therapy was not less effective in women who initially appeared to be at higher risk for adverse sequelae: teens, African-Americans, women with a history of PID, and women colonized with N gonorrhoeae and/or C trachomatis.

Cost comparison

A 14-day prescription for doxycycline should cost less than $25. The single 2-g dose of cefoxitin, combined with the administration charge, should not exceed $100. If cefotetan (2 g) were substituted for cefoxitin (the 2 drugs should be therapeutically equivalent in this clinical situation), the cost would be even less. Conservatively, the charges for a single day in the hospital combined with charges for intravenous antibiotics would be at least $300 to $400.

Beyond the issue of expense are considerations of patient and physician convenience, ease of management, and conservation of scarce resources.

Recommendations

In carefully selected patients, outpatient treatment makes good sense, economically and clinically.

Whom to hospitalize

Patients judged to be seriously ill, particularly those in whom a tubo-ovarian abscess is suspected, should be treated in the hospital. Even with modern antibiotics and sophisticated intensive care, mortalities still occur in women with severe PID complicated by a ruptured abscess.

In addition, patients should be hospitalized for treatment if they are judged to be at risk for noncompliance, lack a reliable support system at home, or have previously failed outpatient management.

A technique that reduces C-section wound complications in the obese

Closure method, but not surgical drains, lowers morbidity

Ramsey PS, White AM, Guinn D, et al. Subcutaneous tissue reapproximation, alone or in combination with drain, in obese women undergoing cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:967–973.

- In obese women having cesarean delivery, closure of the subcutaneous layer reduces risk of wound complications such as seroma, hematoma, incisional abscess, and fascial dehiscence. Addition of a closed system drain did not improve outcome beyond that achieved with subcutaneous closure alone.

Summary

This prospective randomized trial at 5 medical centers assessed the role of 2 surgical techniques in decreasing the risk of wound complications after cesarean delivery in 280 obese women. Patients with subcutaneous thickness greater than or equal to 4 cm were randomized to either subcutaneous suture closure alone (149 women) or suture plus drain (131 women).

The primary study outcome was composite wound morbidity rate, defined by any of the following: subcutaneous tissue dehiscence, seroma, hematoma, incisional abscess, or fascial dehiscence.

Addition of drain did not improve wound morbidity

A running, nonlocking suture of 3-0 Vicryl was used for closure of the subcutaneous layer. The drain used was the Jackson-Pratt surgical drain (10 mm), and it was placed below the layer of subcutaneous suture and then connected to bulb suction. The drain was removed on the third postoperative day, or sooner, if drain output was less than 30 mL in 24 hours. The drain exited the wound via a separate stab site lateral to the incision. All of the skin incisions were closed with staples, which were removed 7 to 14 days after surgery. All patients received standard skin preparations and prophylactic antibiotics.

The composite wound morbidity rate was 17.4% in the suture group and 22.7% in the suture plus drain group (P=NS). Individual wound complication rates were similar in the 2 groups. The authors concluded that the surgical drain did not improve outcome beyond that achieved by closure of the subcutaneous layer.

Commentary

Endometritis and wound disruption are the most common complications of cesarean delivery. Wound complications clearly are the more serious, for they inevitably lead to persistent patient discomfort, prolonged hospitalization, and increased expense. Moreover, they may necessitate additional surgical intervention to drain a seroma, hematoma or abscess or to repair a fascial dehiscence.

Postcesarean wound complications are particularly likely in the obese, and, unfortunately, the prevalence of obesity is steadily increasing among obstetric patients.

In a landmark study of wound infections in many different types of surgery, Cruse and Foord4 demonstrated that sutures in the subcutaneous space actually increased the wound complication rate. DelValle and colleagues5 were among the first to challenge this observation and show that, at least in women having cesarean delivery, reapproximation of Camper’s fascia reduced risk of wound disruption.

Is thickness of subcutaneous layer a key determinant of wound morbidity?

Naumann et al6 and Vermillion and colleagues7 subsequently demonstrated that thickness of the subcutaneous layer was the key determinant of wound complications. Chelmow and colleagues8 recently published an excellent meta-analysis confirming that, in women with a subcutaneous layer greater than 2 cm, closure of the subcutaneous layer with suture significantly reduced the rate of wound disruption.