User login

John Nelson, MD: A New Hospitalist

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Host of Factors Play Into Hospitalist Billing for Patient Transfers

Patient Transfers

Hospitalist billing depends on several factors. Know your role and avoid common mistakes Patient transfers can occur for many reasons: advanced technological services required, health insurance coverage, or a change in the level of care, to name a few. Patient care that is provided in the acute-care setting does not always terminate with discharge to home. Frequently, hospitalists are involved in patient transfers to another location to receive additional services: intrafacility (a different unit or related facility within the same physical plant) or interfacility (geographically separate facilities). The hospitalist must identify his or her role in the transfer and the patient’s new environment.

Physician billing in the transferred setting depends upon several factors:1

- Shared or merged medical record;

- The attending of record in each setting;

- The requirements for care rendered by the hospitalist in each setting; and

- Service dates.

Intrafacility Initial Service

Let’s examine a common example: A hospitalist serves as the “attending of record” in an inpatient hospital where acute care is required for an 83-year-old female with hypertension and diabetes who sustained a left hip fracture. The hospitalist plans to discharge the patient to the rehabilitation unit. After transfer, the rehabilitation physician becomes the attending of record, and the hospitalist might be asked to provide ongoing care for the patient’s hypertension and diabetes.

What should the hospitalist report for the initial post-transfer service? The typical options to consider are:2

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255);

- Initial hospital care (99221-99223); and

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233).

Report a consultation only if the rehab attending requests an opinion or advice for an unrelated, new condition instead of previously treated conditions, and the requesting physician’s intent is for opinion or advice on management options rather than the a priori intent for the hospitalist to assume the patient’s medical care. If these requirements are met, the hospitalist may report an inpatient consultation code (99251-99255). Alternatively, if the intent or need represents a continuity of medical care provided during the acute episode of care, report the most appropriate subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) for the hospitalist’s initial rehab visit and all follow-up services.

Initial hospital care (99221-99223) codes can only be reported for Medicare beneficiaries in place of consultation codes (99251-99255), as Medicare ceased to reimburse consultation codes.3 Most other payors who do not recognize consultation services only allow one initial hospital care code per hospitalization, reserved for the attending of record.

Interfacility Initial Service

Hospitalist groups provide patient care and coverage in many different types of facilities. Confusion often arises when the “attending of record” during acute care and the “subacute” setting (e.g. long-term acute-care hospital) are two different hospitalists from the same group practice. The hospitalist receiving the patient in the transfer facility may decide to report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233), because the group has been providing ongoing care to this patient. In this scenario, the hospitalist group could be losing revenue if an admission service (99221-99223) was not reported.

An initial hospital care service (99221-99223) is permitted when the transfer is between:

- Different hospitals;

- Different facilities under common ownership which do not have merged records; or

- Between the acute-care hospital and a PPS (prospective payment system)-exempt unit within the same hospital when there are no merged records (e.g. Medicare Part A-covered inpatient care in psychiatric, rehabilitation, critical access, and long-term care hospitals).4

In all other transfer circumstances not meeting the elements noted above, the physician should bill only the appropriate level of subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for the date of transfer.1 Do not equate “merged records” to commonly accessible charts via an electronic medical record system or an electronic storage system. If the medical record for the patient’s acute stay is “closed” and the patient is given a separate medical record and registration for the stay in the transferred facility, consider the transfer stay as a separate admission.

Billing Two Services on Day of Transfer

Whether the transfer is classified as intrafacility or interfacility, an individual hospitalist or two separate hospitalists from the same group practice may provide the acute-care discharge and the transfer admission. A hospital discharge day management service (99238-99239) and an initial hospital care service (99221-99223) can only be reported if they do not occur on the same day.1 Physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician; if more than one evaluation and management (face to face) service is provided on the same day to the same patient by the same physician or more than one physician in the same specialty in the same group, only one evaluation and management service may be reported.5

The Exception

CMS will allow a single hospitalist or two hospitalists from the same group practice to report a discharge day management service on the same day as an admission service. When they are billed by the same physician or group with the same date of service, contractors are instructed to pay the hospital discharge day management code (99238-99239) in addition to a nursing facility admission code (99304-99306).6

Conversely, if the patient is admitted to a hospital (99221-99223) following a nursing facility discharge (99315-99316) on the same date by the same physician/group, insurers will only reimburse the initial hospital care code. Payment for the initial hospital care service includes all work performed by the physician/group in all sites of service on that date.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References available online at the-hospitalist.org

Patient Transfers

Hospitalist billing depends on several factors. Know your role and avoid common mistakes Patient transfers can occur for many reasons: advanced technological services required, health insurance coverage, or a change in the level of care, to name a few. Patient care that is provided in the acute-care setting does not always terminate with discharge to home. Frequently, hospitalists are involved in patient transfers to another location to receive additional services: intrafacility (a different unit or related facility within the same physical plant) or interfacility (geographically separate facilities). The hospitalist must identify his or her role in the transfer and the patient’s new environment.

Physician billing in the transferred setting depends upon several factors:1

- Shared or merged medical record;

- The attending of record in each setting;

- The requirements for care rendered by the hospitalist in each setting; and

- Service dates.

Intrafacility Initial Service

Let’s examine a common example: A hospitalist serves as the “attending of record” in an inpatient hospital where acute care is required for an 83-year-old female with hypertension and diabetes who sustained a left hip fracture. The hospitalist plans to discharge the patient to the rehabilitation unit. After transfer, the rehabilitation physician becomes the attending of record, and the hospitalist might be asked to provide ongoing care for the patient’s hypertension and diabetes.

What should the hospitalist report for the initial post-transfer service? The typical options to consider are:2

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255);

- Initial hospital care (99221-99223); and

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233).

Report a consultation only if the rehab attending requests an opinion or advice for an unrelated, new condition instead of previously treated conditions, and the requesting physician’s intent is for opinion or advice on management options rather than the a priori intent for the hospitalist to assume the patient’s medical care. If these requirements are met, the hospitalist may report an inpatient consultation code (99251-99255). Alternatively, if the intent or need represents a continuity of medical care provided during the acute episode of care, report the most appropriate subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) for the hospitalist’s initial rehab visit and all follow-up services.

Initial hospital care (99221-99223) codes can only be reported for Medicare beneficiaries in place of consultation codes (99251-99255), as Medicare ceased to reimburse consultation codes.3 Most other payors who do not recognize consultation services only allow one initial hospital care code per hospitalization, reserved for the attending of record.

Interfacility Initial Service

Hospitalist groups provide patient care and coverage in many different types of facilities. Confusion often arises when the “attending of record” during acute care and the “subacute” setting (e.g. long-term acute-care hospital) are two different hospitalists from the same group practice. The hospitalist receiving the patient in the transfer facility may decide to report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233), because the group has been providing ongoing care to this patient. In this scenario, the hospitalist group could be losing revenue if an admission service (99221-99223) was not reported.

An initial hospital care service (99221-99223) is permitted when the transfer is between:

- Different hospitals;

- Different facilities under common ownership which do not have merged records; or

- Between the acute-care hospital and a PPS (prospective payment system)-exempt unit within the same hospital when there are no merged records (e.g. Medicare Part A-covered inpatient care in psychiatric, rehabilitation, critical access, and long-term care hospitals).4

In all other transfer circumstances not meeting the elements noted above, the physician should bill only the appropriate level of subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for the date of transfer.1 Do not equate “merged records” to commonly accessible charts via an electronic medical record system or an electronic storage system. If the medical record for the patient’s acute stay is “closed” and the patient is given a separate medical record and registration for the stay in the transferred facility, consider the transfer stay as a separate admission.

Billing Two Services on Day of Transfer

Whether the transfer is classified as intrafacility or interfacility, an individual hospitalist or two separate hospitalists from the same group practice may provide the acute-care discharge and the transfer admission. A hospital discharge day management service (99238-99239) and an initial hospital care service (99221-99223) can only be reported if they do not occur on the same day.1 Physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician; if more than one evaluation and management (face to face) service is provided on the same day to the same patient by the same physician or more than one physician in the same specialty in the same group, only one evaluation and management service may be reported.5

The Exception

CMS will allow a single hospitalist or two hospitalists from the same group practice to report a discharge day management service on the same day as an admission service. When they are billed by the same physician or group with the same date of service, contractors are instructed to pay the hospital discharge day management code (99238-99239) in addition to a nursing facility admission code (99304-99306).6

Conversely, if the patient is admitted to a hospital (99221-99223) following a nursing facility discharge (99315-99316) on the same date by the same physician/group, insurers will only reimburse the initial hospital care code. Payment for the initial hospital care service includes all work performed by the physician/group in all sites of service on that date.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References available online at the-hospitalist.org

Patient Transfers

Hospitalist billing depends on several factors. Know your role and avoid common mistakes Patient transfers can occur for many reasons: advanced technological services required, health insurance coverage, or a change in the level of care, to name a few. Patient care that is provided in the acute-care setting does not always terminate with discharge to home. Frequently, hospitalists are involved in patient transfers to another location to receive additional services: intrafacility (a different unit or related facility within the same physical plant) or interfacility (geographically separate facilities). The hospitalist must identify his or her role in the transfer and the patient’s new environment.

Physician billing in the transferred setting depends upon several factors:1

- Shared or merged medical record;

- The attending of record in each setting;

- The requirements for care rendered by the hospitalist in each setting; and

- Service dates.

Intrafacility Initial Service

Let’s examine a common example: A hospitalist serves as the “attending of record” in an inpatient hospital where acute care is required for an 83-year-old female with hypertension and diabetes who sustained a left hip fracture. The hospitalist plans to discharge the patient to the rehabilitation unit. After transfer, the rehabilitation physician becomes the attending of record, and the hospitalist might be asked to provide ongoing care for the patient’s hypertension and diabetes.

What should the hospitalist report for the initial post-transfer service? The typical options to consider are:2

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255);

- Initial hospital care (99221-99223); and

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233).

Report a consultation only if the rehab attending requests an opinion or advice for an unrelated, new condition instead of previously treated conditions, and the requesting physician’s intent is for opinion or advice on management options rather than the a priori intent for the hospitalist to assume the patient’s medical care. If these requirements are met, the hospitalist may report an inpatient consultation code (99251-99255). Alternatively, if the intent or need represents a continuity of medical care provided during the acute episode of care, report the most appropriate subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) for the hospitalist’s initial rehab visit and all follow-up services.

Initial hospital care (99221-99223) codes can only be reported for Medicare beneficiaries in place of consultation codes (99251-99255), as Medicare ceased to reimburse consultation codes.3 Most other payors who do not recognize consultation services only allow one initial hospital care code per hospitalization, reserved for the attending of record.

Interfacility Initial Service

Hospitalist groups provide patient care and coverage in many different types of facilities. Confusion often arises when the “attending of record” during acute care and the “subacute” setting (e.g. long-term acute-care hospital) are two different hospitalists from the same group practice. The hospitalist receiving the patient in the transfer facility may decide to report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233), because the group has been providing ongoing care to this patient. In this scenario, the hospitalist group could be losing revenue if an admission service (99221-99223) was not reported.

An initial hospital care service (99221-99223) is permitted when the transfer is between:

- Different hospitals;

- Different facilities under common ownership which do not have merged records; or

- Between the acute-care hospital and a PPS (prospective payment system)-exempt unit within the same hospital when there are no merged records (e.g. Medicare Part A-covered inpatient care in psychiatric, rehabilitation, critical access, and long-term care hospitals).4

In all other transfer circumstances not meeting the elements noted above, the physician should bill only the appropriate level of subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for the date of transfer.1 Do not equate “merged records” to commonly accessible charts via an electronic medical record system or an electronic storage system. If the medical record for the patient’s acute stay is “closed” and the patient is given a separate medical record and registration for the stay in the transferred facility, consider the transfer stay as a separate admission.

Billing Two Services on Day of Transfer

Whether the transfer is classified as intrafacility or interfacility, an individual hospitalist or two separate hospitalists from the same group practice may provide the acute-care discharge and the transfer admission. A hospital discharge day management service (99238-99239) and an initial hospital care service (99221-99223) can only be reported if they do not occur on the same day.1 Physicians in the same group practice who are in the same specialty must bill and be paid as though they were a single physician; if more than one evaluation and management (face to face) service is provided on the same day to the same patient by the same physician or more than one physician in the same specialty in the same group, only one evaluation and management service may be reported.5

The Exception

CMS will allow a single hospitalist or two hospitalists from the same group practice to report a discharge day management service on the same day as an admission service. When they are billed by the same physician or group with the same date of service, contractors are instructed to pay the hospital discharge day management code (99238-99239) in addition to a nursing facility admission code (99304-99306).6

Conversely, if the patient is admitted to a hospital (99221-99223) following a nursing facility discharge (99315-99316) on the same date by the same physician/group, insurers will only reimburse the initial hospital care code. Payment for the initial hospital care service includes all work performed by the physician/group in all sites of service on that date.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References available online at the-hospitalist.org

Society of Hospital Medicine's CODE-H Returns in January

Staying up to date on the latest techniques for optimal coding can be daunting, but you don't have to do it alone. SHM's exclusive CODE-H program enables hospitalists (and others in their practice) to learn best practices in coding from national experts in the field. It also allows participants to ask questions of other hospitalists who may be experiencing similar coding challenges.

CODE-H works through SHM's new online collaboration space, HMX (www.hmxchange.org), and provides live webinar sessions with expert faculty, downloadable resources, and a discussion forum for participants to ask questions and provide answers.

Previous CODE-H participants can extend their CODE-H subscriptions. The extension is $300, and free for prior participants who refer an individual or group to CODE-H.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Staying up to date on the latest techniques for optimal coding can be daunting, but you don't have to do it alone. SHM's exclusive CODE-H program enables hospitalists (and others in their practice) to learn best practices in coding from national experts in the field. It also allows participants to ask questions of other hospitalists who may be experiencing similar coding challenges.

CODE-H works through SHM's new online collaboration space, HMX (www.hmxchange.org), and provides live webinar sessions with expert faculty, downloadable resources, and a discussion forum for participants to ask questions and provide answers.

Previous CODE-H participants can extend their CODE-H subscriptions. The extension is $300, and free for prior participants who refer an individual or group to CODE-H.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Staying up to date on the latest techniques for optimal coding can be daunting, but you don't have to do it alone. SHM's exclusive CODE-H program enables hospitalists (and others in their practice) to learn best practices in coding from national experts in the field. It also allows participants to ask questions of other hospitalists who may be experiencing similar coding challenges.

CODE-H works through SHM's new online collaboration space, HMX (www.hmxchange.org), and provides live webinar sessions with expert faculty, downloadable resources, and a discussion forum for participants to ask questions and provide answers.

Previous CODE-H participants can extend their CODE-H subscriptions. The extension is $300, and free for prior participants who refer an individual or group to CODE-H.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

John Nelson: Peformance Key to Federal Value-Based Payment Modifier Plan

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

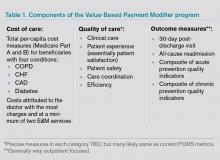

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

Pay-for-Performance Challenged as Best Model for Healthcare

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

John Nelson: Learning CPT Coding and Documentation Tricky for Hospitalists

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

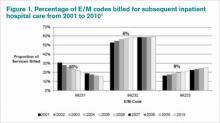

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).