User login

Still No Implementation Date Set for ICD-10

A new implementation date for the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases coding system (ICD-10) isn't expected to be known until after the November election, says a coding specialist. But hospitalists and others should not take that as a sign to just sit around and wait for a date.

"We're probably not going to hear anything until after the election is finished," says Brenda Edwards, CPC, CPMA, a coding and compliance specialist with Kansas Medical Mutual Insurance Co. and a trainer with AAPC. "The thing that's worrisome, though, is people think this delay we have encountered is a time to sit back and do nothing, but really we’re almost burning money by not doing anything."

An outcry from many physicians led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to delay the planned October 2013 implementation date. No new date has been announced.

Edwards urges physicians, billing specialists, and group leaders to use the delay as an opportunity to better prepare for the implementation. She suggests checking with vendors and preparing training programs to help adjust to the new coding initiative, which will quadruple the number of billing codes to 68,000.

"Everyone at this point should still be moving forward," she says.

At the same time, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is seeking public comment on a new version of its ICD-10 readiness assessment. Those interested in weighing in can learn more here.

A new implementation date for the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases coding system (ICD-10) isn't expected to be known until after the November election, says a coding specialist. But hospitalists and others should not take that as a sign to just sit around and wait for a date.

"We're probably not going to hear anything until after the election is finished," says Brenda Edwards, CPC, CPMA, a coding and compliance specialist with Kansas Medical Mutual Insurance Co. and a trainer with AAPC. "The thing that's worrisome, though, is people think this delay we have encountered is a time to sit back and do nothing, but really we’re almost burning money by not doing anything."

An outcry from many physicians led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to delay the planned October 2013 implementation date. No new date has been announced.

Edwards urges physicians, billing specialists, and group leaders to use the delay as an opportunity to better prepare for the implementation. She suggests checking with vendors and preparing training programs to help adjust to the new coding initiative, which will quadruple the number of billing codes to 68,000.

"Everyone at this point should still be moving forward," she says.

At the same time, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is seeking public comment on a new version of its ICD-10 readiness assessment. Those interested in weighing in can learn more here.

A new implementation date for the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases coding system (ICD-10) isn't expected to be known until after the November election, says a coding specialist. But hospitalists and others should not take that as a sign to just sit around and wait for a date.

"We're probably not going to hear anything until after the election is finished," says Brenda Edwards, CPC, CPMA, a coding and compliance specialist with Kansas Medical Mutual Insurance Co. and a trainer with AAPC. "The thing that's worrisome, though, is people think this delay we have encountered is a time to sit back and do nothing, but really we’re almost burning money by not doing anything."

An outcry from many physicians led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to delay the planned October 2013 implementation date. No new date has been announced.

Edwards urges physicians, billing specialists, and group leaders to use the delay as an opportunity to better prepare for the implementation. She suggests checking with vendors and preparing training programs to help adjust to the new coding initiative, which will quadruple the number of billing codes to 68,000.

"Everyone at this point should still be moving forward," she says.

At the same time, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is seeking public comment on a new version of its ICD-10 readiness assessment. Those interested in weighing in can learn more here.

Survey Insights: Better Understand CPT Coding Intensity

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

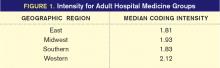

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Know Surgical Package Requirements before Billing Postoperative Care

Hospitalists often are involved in the postoperative care of the surgical patient. However, HM is emerging in the admitting/attending role for procedural patients. Confusion can arise as to the nature of the hospitalist service, and whether it is deemed billable. Knowing the surgical package requirements can help hospitalists consider the issues.

Global Surgical Package Period1

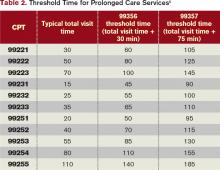

Surgical procedures, categorized as major or minor surgery, are reimbursed for pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. Postoperative care varies according to the procedure’s assigned global period, which designates zero, 10, or 90 postoperative days. (Physicians can review the global period for any given CPT code in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, available at www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.)

Services classified with “XXX” do not have the global period concept. “ZZZ” services denote an “add-on” procedure code that must always be reported with a primary procedure code and assumes the global period assigned to the primary procedure performed.

Major surgery allocates a 90-day global period in which the surgeon is responsible for all related surgical care one day before surgery through 90 postoperative days with no additional charge. Minor surgery, including endoscopy, appoints a zero-day or 10-day postoperative period. The zero-day global period encompasses only services provided on the surgical day, whereas 10-day global periods include services on the surgical day through 10 postoperative days.

Global Surgical Package Components2

The global surgical package comprises a host of responsibilities that include standard facility requirements of filling out all necessary paperwork involved in surgical cases (e.g. preoperative H&P, operative consent forms, preoperative orders). Additionally, the surgeon’s packaged payment includes (at no extra charge):

- Preoperative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional postoperative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes; local incisional care; removal of cutaneous sutures and staples; line removals; changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes; and discharge services; and

- Postoperative pain management provided by the surgeon.

- Examples of services that are not included in the global surgical package, (i.e. are separately billable and may require an appropriate modifier) are:

- The initial consultation or evaluation of the problem by the surgeon to determine the need for surgery;

- Services of other physicians except where the other physicians are providing coverage for the surgeon or agree on a transfer of care (i.e. a formal agreement in the form of a letter or an annotation in the discharge summary, hospital record, or ASC record);

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon unrelated to the diagnosis for which the surgical procedure is performed, unless the visits occur due to complications of the surgery;

- Diagnostic tests and procedures, including diagnostic radiological procedures;

- Clearly distinct surgical procedures during the postoperative period that do not result in repeat operations or treatment for complications;

- Treatment for postoperative complications that requires a return trip to the operating room (OR), catheterization lab or endoscopy suite;

- Immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants; and

- Critical-care services (CPT codes 99291 and 99292) unrelated to the surgery where a seriously injured or burned patient is critically ill and requires constant attendance of the surgeon.

Classification of “Surgeon”

For billing purposes, the “surgeon” is a qualified physician who can perform “surgical” services within their scope of practice. All physicians with the same specialty designation in the same group practice as the “surgeon” (i.e. reporting services under the same tax identification number) are considered a single entity and must adhere to the global period billing rules initiated by the “surgeon.”

Alternately, physicians with different specialty designations in the same group practice (e.g. a hospitalist and a cardiologist in a multispecialty group who report services under the same tax identification number) or different group practices can perform and separately report medically necessary services during the surgeon’s global period, as long as a formal (mutually agreed-upon) transfer of care did not occur.

Medical Necessity

With the growth of HM programs and the admission/attending role expansion, involvement in surgical cases comes under scrutiny for medical necessity. Admitting a patient who has active medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, emphysema) is reasonable and necessary because the patient has a well-defined need for medical management by the hospitalist. Participation in the care of these patients is separately billable from the surgeon’s global period package.

Alternatively, a hospitalist might be required to admit and follow surgical patients who have no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions aside from the surgical problem. In these cases, hospitalist involvement may satisfy facility policy (quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) and administrative functions (discharge services or coordination of care) rather than active clinical management. This “medical management” will not be considered “medically necessary” by the payor, and may be denied as incidental to the surgeon’s perioperative services. Erroneous payment can occur, which will result in refund requests, as payors do not want to pay twice for duplicate services. Hospitalists can attempt to negotiate other terms with facilities to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

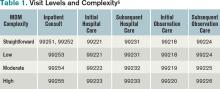

Consider the Case

A patient with numerous medical comorbidities is admitted to the hospitalist service for stabilization prior to surgery, which will occur the next day. The hospitalist can report the appropriate admission code (99221-99223) without need for modifiers because the hospitalist is the attending of record and in a different specialty group. If a private insurer denies the claim as inclusive to the surgical service, the hospitalist can appeal with notes and a cover letter, along with the Medicare guidelines for global surgical package. The hospitalist may continue to provide postoperative daily care, as needed, to manage the patient’s chronic conditions, and report each service as subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) without modifier until the day of discharge (99238-99239). Again, if a payor issues a denial (inclusive to surgery), appealing with notes might be necessary.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10: HHS proposes one-year delay of ICD-10 compliance date. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/index.html?redirect=/ICD10. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

Hospitalists often are involved in the postoperative care of the surgical patient. However, HM is emerging in the admitting/attending role for procedural patients. Confusion can arise as to the nature of the hospitalist service, and whether it is deemed billable. Knowing the surgical package requirements can help hospitalists consider the issues.

Global Surgical Package Period1

Surgical procedures, categorized as major or minor surgery, are reimbursed for pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. Postoperative care varies according to the procedure’s assigned global period, which designates zero, 10, or 90 postoperative days. (Physicians can review the global period for any given CPT code in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, available at www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.)

Services classified with “XXX” do not have the global period concept. “ZZZ” services denote an “add-on” procedure code that must always be reported with a primary procedure code and assumes the global period assigned to the primary procedure performed.

Major surgery allocates a 90-day global period in which the surgeon is responsible for all related surgical care one day before surgery through 90 postoperative days with no additional charge. Minor surgery, including endoscopy, appoints a zero-day or 10-day postoperative period. The zero-day global period encompasses only services provided on the surgical day, whereas 10-day global periods include services on the surgical day through 10 postoperative days.

Global Surgical Package Components2

The global surgical package comprises a host of responsibilities that include standard facility requirements of filling out all necessary paperwork involved in surgical cases (e.g. preoperative H&P, operative consent forms, preoperative orders). Additionally, the surgeon’s packaged payment includes (at no extra charge):

- Preoperative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional postoperative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes; local incisional care; removal of cutaneous sutures and staples; line removals; changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes; and discharge services; and

- Postoperative pain management provided by the surgeon.

- Examples of services that are not included in the global surgical package, (i.e. are separately billable and may require an appropriate modifier) are:

- The initial consultation or evaluation of the problem by the surgeon to determine the need for surgery;

- Services of other physicians except where the other physicians are providing coverage for the surgeon or agree on a transfer of care (i.e. a formal agreement in the form of a letter or an annotation in the discharge summary, hospital record, or ASC record);

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon unrelated to the diagnosis for which the surgical procedure is performed, unless the visits occur due to complications of the surgery;

- Diagnostic tests and procedures, including diagnostic radiological procedures;

- Clearly distinct surgical procedures during the postoperative period that do not result in repeat operations or treatment for complications;

- Treatment for postoperative complications that requires a return trip to the operating room (OR), catheterization lab or endoscopy suite;

- Immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants; and

- Critical-care services (CPT codes 99291 and 99292) unrelated to the surgery where a seriously injured or burned patient is critically ill and requires constant attendance of the surgeon.

Classification of “Surgeon”

For billing purposes, the “surgeon” is a qualified physician who can perform “surgical” services within their scope of practice. All physicians with the same specialty designation in the same group practice as the “surgeon” (i.e. reporting services under the same tax identification number) are considered a single entity and must adhere to the global period billing rules initiated by the “surgeon.”

Alternately, physicians with different specialty designations in the same group practice (e.g. a hospitalist and a cardiologist in a multispecialty group who report services under the same tax identification number) or different group practices can perform and separately report medically necessary services during the surgeon’s global period, as long as a formal (mutually agreed-upon) transfer of care did not occur.

Medical Necessity

With the growth of HM programs and the admission/attending role expansion, involvement in surgical cases comes under scrutiny for medical necessity. Admitting a patient who has active medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, emphysema) is reasonable and necessary because the patient has a well-defined need for medical management by the hospitalist. Participation in the care of these patients is separately billable from the surgeon’s global period package.

Alternatively, a hospitalist might be required to admit and follow surgical patients who have no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions aside from the surgical problem. In these cases, hospitalist involvement may satisfy facility policy (quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) and administrative functions (discharge services or coordination of care) rather than active clinical management. This “medical management” will not be considered “medically necessary” by the payor, and may be denied as incidental to the surgeon’s perioperative services. Erroneous payment can occur, which will result in refund requests, as payors do not want to pay twice for duplicate services. Hospitalists can attempt to negotiate other terms with facilities to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Consider the Case

A patient with numerous medical comorbidities is admitted to the hospitalist service for stabilization prior to surgery, which will occur the next day. The hospitalist can report the appropriate admission code (99221-99223) without need for modifiers because the hospitalist is the attending of record and in a different specialty group. If a private insurer denies the claim as inclusive to the surgical service, the hospitalist can appeal with notes and a cover letter, along with the Medicare guidelines for global surgical package. The hospitalist may continue to provide postoperative daily care, as needed, to manage the patient’s chronic conditions, and report each service as subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) without modifier until the day of discharge (99238-99239). Again, if a payor issues a denial (inclusive to surgery), appealing with notes might be necessary.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10: HHS proposes one-year delay of ICD-10 compliance date. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/index.html?redirect=/ICD10. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

Hospitalists often are involved in the postoperative care of the surgical patient. However, HM is emerging in the admitting/attending role for procedural patients. Confusion can arise as to the nature of the hospitalist service, and whether it is deemed billable. Knowing the surgical package requirements can help hospitalists consider the issues.

Global Surgical Package Period1

Surgical procedures, categorized as major or minor surgery, are reimbursed for pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. Postoperative care varies according to the procedure’s assigned global period, which designates zero, 10, or 90 postoperative days. (Physicians can review the global period for any given CPT code in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, available at www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.)

Services classified with “XXX” do not have the global period concept. “ZZZ” services denote an “add-on” procedure code that must always be reported with a primary procedure code and assumes the global period assigned to the primary procedure performed.

Major surgery allocates a 90-day global period in which the surgeon is responsible for all related surgical care one day before surgery through 90 postoperative days with no additional charge. Minor surgery, including endoscopy, appoints a zero-day or 10-day postoperative period. The zero-day global period encompasses only services provided on the surgical day, whereas 10-day global periods include services on the surgical day through 10 postoperative days.

Global Surgical Package Components2

The global surgical package comprises a host of responsibilities that include standard facility requirements of filling out all necessary paperwork involved in surgical cases (e.g. preoperative H&P, operative consent forms, preoperative orders). Additionally, the surgeon’s packaged payment includes (at no extra charge):

- Preoperative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional postoperative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes; local incisional care; removal of cutaneous sutures and staples; line removals; changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes; and discharge services; and

- Postoperative pain management provided by the surgeon.

- Examples of services that are not included in the global surgical package, (i.e. are separately billable and may require an appropriate modifier) are:

- The initial consultation or evaluation of the problem by the surgeon to determine the need for surgery;

- Services of other physicians except where the other physicians are providing coverage for the surgeon or agree on a transfer of care (i.e. a formal agreement in the form of a letter or an annotation in the discharge summary, hospital record, or ASC record);

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon unrelated to the diagnosis for which the surgical procedure is performed, unless the visits occur due to complications of the surgery;

- Diagnostic tests and procedures, including diagnostic radiological procedures;

- Clearly distinct surgical procedures during the postoperative period that do not result in repeat operations or treatment for complications;

- Treatment for postoperative complications that requires a return trip to the operating room (OR), catheterization lab or endoscopy suite;

- Immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants; and

- Critical-care services (CPT codes 99291 and 99292) unrelated to the surgery where a seriously injured or burned patient is critically ill and requires constant attendance of the surgeon.

Classification of “Surgeon”

For billing purposes, the “surgeon” is a qualified physician who can perform “surgical” services within their scope of practice. All physicians with the same specialty designation in the same group practice as the “surgeon” (i.e. reporting services under the same tax identification number) are considered a single entity and must adhere to the global period billing rules initiated by the “surgeon.”

Alternately, physicians with different specialty designations in the same group practice (e.g. a hospitalist and a cardiologist in a multispecialty group who report services under the same tax identification number) or different group practices can perform and separately report medically necessary services during the surgeon’s global period, as long as a formal (mutually agreed-upon) transfer of care did not occur.

Medical Necessity

With the growth of HM programs and the admission/attending role expansion, involvement in surgical cases comes under scrutiny for medical necessity. Admitting a patient who has active medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, emphysema) is reasonable and necessary because the patient has a well-defined need for medical management by the hospitalist. Participation in the care of these patients is separately billable from the surgeon’s global period package.

Alternatively, a hospitalist might be required to admit and follow surgical patients who have no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions aside from the surgical problem. In these cases, hospitalist involvement may satisfy facility policy (quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) and administrative functions (discharge services or coordination of care) rather than active clinical management. This “medical management” will not be considered “medically necessary” by the payor, and may be denied as incidental to the surgeon’s perioperative services. Erroneous payment can occur, which will result in refund requests, as payors do not want to pay twice for duplicate services. Hospitalists can attempt to negotiate other terms with facilities to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Consider the Case

A patient with numerous medical comorbidities is admitted to the hospitalist service for stabilization prior to surgery, which will occur the next day. The hospitalist can report the appropriate admission code (99221-99223) without need for modifiers because the hospitalist is the attending of record and in a different specialty group. If a private insurer denies the claim as inclusive to the surgical service, the hospitalist can appeal with notes and a cover letter, along with the Medicare guidelines for global surgical package. The hospitalist may continue to provide postoperative daily care, as needed, to manage the patient’s chronic conditions, and report each service as subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) without modifier until the day of discharge (99238-99239). Again, if a payor issues a denial (inclusive to surgery), appealing with notes might be necessary.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10: HHS proposes one-year delay of ICD-10 compliance date. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/index.html?redirect=/ICD10. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

Physician Payment Systems Remain Constant

I would like to know where payment for the service of hospitalists fits into the insurance/Medicare payment system. Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital and, therefore, billed through the hospital system? Are they considered independent doctors and, therefore, do their own direct billing? Do they, in general, accept assignment of benefits from you for your insurance/Medicare? Do they sign contracts with insurance/Medicare to participate in their plans?

Carole L. Hughes

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

For the sake of argument, let’s say that Carole is on the outside looking in—meaning she’s not a healthcare practitioner, but a consumer. It might seem a bit strange to wonder where all these “hospitalists” come from, and who pays for them. Let’s walk through a few scenarios as outlined here.

Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital? They certainly could be directly employed by the hospital, but it’s just as likely they could be contracted with the hospital for certain services, such as taking ED call for unassigned patients. It’s also entirely possible that the hospitalist has no direct financial relationship with the hospital at all. In this case, a hospitalist is taking cases that are referred from other physicians and for which there is a coverage agreement. The most common situation is a primary-care physician group that is looking for a hospitalist to care for their patients in the hospital. This is usually a handshake agreement, with no money involved.

Do hospitalists do their own direct billing to the insurers? As for this part of the question, it’s time to separate “hospital services” from “hospitalist services.” Hospital services are billed under Medicare Part A, while physician services are billed under Medicare Part B, meaning that even if a physician is employed directly by the hospital, that physician’s professional services are still billed and paid separate from any hospital charges (for things like the bed, supplies, and nursing). Because Medicare sets the ground rules, other insurances typically follow suit. Payment applies similarly to the contracted hospitalists and independent hospitalists.

Do hospitalists have to be credentialed with the insurers? Yes. Whether it is Medicare or Cigna or United, each individual physician must be credentialed with the payors to receive payment. Medicare credentialing for physicians is pretty universal, given that most of our patients have this as their primary insurance. Without it, there is no payment from Medicare to the physician. Many groups or hospitals won’t even let their physicians begin seeing patients until that paperwork is approved. Due to timely filing rules, you can’t just start to see patients and hope to get paid later. And there’s no negotiating with the government—whatever Medicare pays in a region for a specific service is the payment the physician receives.

For the private insurers, it’s generally easier to receive payment if you are credentialed, but I’ve seen a few physician groups negotiate payments without agreeing to a flat contracted rate. I don’t recommend this setup, as the patient can often get caught in the middle with a rather hefty bill. Still, there is some room for negotiation on the private insurer payment rates.

In summary, whether a hospitalist is employed by the hospital, contracted, or truly independent, they all bill Medicare and the insurers for their professional fees. Medicare payments won’t vary, but private insurance payments can. It’s certainly a challenging payment system to understand, from either the provider or the patient point of view.

I would like to know where payment for the service of hospitalists fits into the insurance/Medicare payment system. Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital and, therefore, billed through the hospital system? Are they considered independent doctors and, therefore, do their own direct billing? Do they, in general, accept assignment of benefits from you for your insurance/Medicare? Do they sign contracts with insurance/Medicare to participate in their plans?

Carole L. Hughes

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

For the sake of argument, let’s say that Carole is on the outside looking in—meaning she’s not a healthcare practitioner, but a consumer. It might seem a bit strange to wonder where all these “hospitalists” come from, and who pays for them. Let’s walk through a few scenarios as outlined here.

Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital? They certainly could be directly employed by the hospital, but it’s just as likely they could be contracted with the hospital for certain services, such as taking ED call for unassigned patients. It’s also entirely possible that the hospitalist has no direct financial relationship with the hospital at all. In this case, a hospitalist is taking cases that are referred from other physicians and for which there is a coverage agreement. The most common situation is a primary-care physician group that is looking for a hospitalist to care for their patients in the hospital. This is usually a handshake agreement, with no money involved.

Do hospitalists do their own direct billing to the insurers? As for this part of the question, it’s time to separate “hospital services” from “hospitalist services.” Hospital services are billed under Medicare Part A, while physician services are billed under Medicare Part B, meaning that even if a physician is employed directly by the hospital, that physician’s professional services are still billed and paid separate from any hospital charges (for things like the bed, supplies, and nursing). Because Medicare sets the ground rules, other insurances typically follow suit. Payment applies similarly to the contracted hospitalists and independent hospitalists.

Do hospitalists have to be credentialed with the insurers? Yes. Whether it is Medicare or Cigna or United, each individual physician must be credentialed with the payors to receive payment. Medicare credentialing for physicians is pretty universal, given that most of our patients have this as their primary insurance. Without it, there is no payment from Medicare to the physician. Many groups or hospitals won’t even let their physicians begin seeing patients until that paperwork is approved. Due to timely filing rules, you can’t just start to see patients and hope to get paid later. And there’s no negotiating with the government—whatever Medicare pays in a region for a specific service is the payment the physician receives.

For the private insurers, it’s generally easier to receive payment if you are credentialed, but I’ve seen a few physician groups negotiate payments without agreeing to a flat contracted rate. I don’t recommend this setup, as the patient can often get caught in the middle with a rather hefty bill. Still, there is some room for negotiation on the private insurer payment rates.

In summary, whether a hospitalist is employed by the hospital, contracted, or truly independent, they all bill Medicare and the insurers for their professional fees. Medicare payments won’t vary, but private insurance payments can. It’s certainly a challenging payment system to understand, from either the provider or the patient point of view.

I would like to know where payment for the service of hospitalists fits into the insurance/Medicare payment system. Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital and, therefore, billed through the hospital system? Are they considered independent doctors and, therefore, do their own direct billing? Do they, in general, accept assignment of benefits from you for your insurance/Medicare? Do they sign contracts with insurance/Medicare to participate in their plans?

Carole L. Hughes

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

For the sake of argument, let’s say that Carole is on the outside looking in—meaning she’s not a healthcare practitioner, but a consumer. It might seem a bit strange to wonder where all these “hospitalists” come from, and who pays for them. Let’s walk through a few scenarios as outlined here.

Are hospitalists considered employees of the hospital? They certainly could be directly employed by the hospital, but it’s just as likely they could be contracted with the hospital for certain services, such as taking ED call for unassigned patients. It’s also entirely possible that the hospitalist has no direct financial relationship with the hospital at all. In this case, a hospitalist is taking cases that are referred from other physicians and for which there is a coverage agreement. The most common situation is a primary-care physician group that is looking for a hospitalist to care for their patients in the hospital. This is usually a handshake agreement, with no money involved.

Do hospitalists do their own direct billing to the insurers? As for this part of the question, it’s time to separate “hospital services” from “hospitalist services.” Hospital services are billed under Medicare Part A, while physician services are billed under Medicare Part B, meaning that even if a physician is employed directly by the hospital, that physician’s professional services are still billed and paid separate from any hospital charges (for things like the bed, supplies, and nursing). Because Medicare sets the ground rules, other insurances typically follow suit. Payment applies similarly to the contracted hospitalists and independent hospitalists.

Do hospitalists have to be credentialed with the insurers? Yes. Whether it is Medicare or Cigna or United, each individual physician must be credentialed with the payors to receive payment. Medicare credentialing for physicians is pretty universal, given that most of our patients have this as their primary insurance. Without it, there is no payment from Medicare to the physician. Many groups or hospitals won’t even let their physicians begin seeing patients until that paperwork is approved. Due to timely filing rules, you can’t just start to see patients and hope to get paid later. And there’s no negotiating with the government—whatever Medicare pays in a region for a specific service is the payment the physician receives.

For the private insurers, it’s generally easier to receive payment if you are credentialed, but I’ve seen a few physician groups negotiate payments without agreeing to a flat contracted rate. I don’t recommend this setup, as the patient can often get caught in the middle with a rather hefty bill. Still, there is some room for negotiation on the private insurer payment rates.

In summary, whether a hospitalist is employed by the hospital, contracted, or truly independent, they all bill Medicare and the insurers for their professional fees. Medicare payments won’t vary, but private insurance payments can. It’s certainly a challenging payment system to understand, from either the provider or the patient point of view.

ICD-10 Update

On April 17, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published a proposed rule to delay the compliance date for the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10) from Oct. 1, 2013, to Oct. 1, 2014.2

Per HHS, the ICD-10 compliance date change is part of a proposed rule that would adopt a standard for a unique health plan identifier (HPID), adopt a data element that would serve as an “other entity” identifier (OEID), and add a National Provider Identifier (NPI) requirement. The proposed rule was developed by the Office of E-Health Standards and Services (OESS) as part of its ongoing role, delegated by HHS, to establish standards for electronic healthcare transactions under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

HHS proposes that covered entities must be in compliance with ICD-10 by Oct. 1, 2014.

On April 17, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published a proposed rule to delay the compliance date for the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10) from Oct. 1, 2013, to Oct. 1, 2014.2

Per HHS, the ICD-10 compliance date change is part of a proposed rule that would adopt a standard for a unique health plan identifier (HPID), adopt a data element that would serve as an “other entity” identifier (OEID), and add a National Provider Identifier (NPI) requirement. The proposed rule was developed by the Office of E-Health Standards and Services (OESS) as part of its ongoing role, delegated by HHS, to establish standards for electronic healthcare transactions under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

HHS proposes that covered entities must be in compliance with ICD-10 by Oct. 1, 2014.

On April 17, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published a proposed rule to delay the compliance date for the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10) from Oct. 1, 2013, to Oct. 1, 2014.2

Per HHS, the ICD-10 compliance date change is part of a proposed rule that would adopt a standard for a unique health plan identifier (HPID), adopt a data element that would serve as an “other entity” identifier (OEID), and add a National Provider Identifier (NPI) requirement. The proposed rule was developed by the Office of E-Health Standards and Services (OESS) as part of its ongoing role, delegated by HHS, to establish standards for electronic healthcare transactions under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

HHS proposes that covered entities must be in compliance with ICD-10 by Oct. 1, 2014.

Efficacy, Diagnoses, Frequency Play Parts in Coverage Limitations

Under Section 1862(a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).1 Coverage limitations include:2

- Proven clinical efficacy. For example, Medicare deems acupuncture “experimental/investigational” in the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury;

- Diagnoses. As an example, vitamin B-12 injections are covered, but only for such diagnoses as pernicious anemia and dementias secondary to vitamin B-12 deficiency; and

- Frequency/utilization parameters. For example, a screening colonoscopy (G0105) can be paid once every 24 months for beneficiaries who are at high risk for colorectal cancer; otherwise the service is limited to once every 10 years.

Beyond these factors, individual consideration might be granted. Supportive and unambiguous documentation (medical records, clinical studies, etc.) must be submitted when the clinical circumstances do not appear to support the medical necessity for the service.

Diagnoses Selection

Select the code that best represents the primary reason for the service or procedure on a given date. In the absence of a definitive diagnosis, the code may correspond to a sign or symptom. Physicians never should report a code that represents a probable, suspected, or “rule out” condition. Although facility billing might consider these unconfirmed circumstances (when necessary), physician billing prohibits this practice.

Reporting services for hospitalized patients is challenging when multiple services for the same patient are provided on the same date by the same or different physician, also known as concurrent care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while still considering the patient’s overall condition; each physician should report the corresponding diagnosis for that management. If billed correctly, each physician will have a different primary diagnosis code to justify their involvement, increasing their opportunity for payment.3

The non-primary diagnoses might also be listed on the claim if appropriately addressed in the documentation (i.e. “non-primary” conditions’ indirect role in the focused management of the primary condition). For example, a hospitalist, pulmonologist, and nephrologist manage a patient’s uncontrolled diabetes (250.02), COPD exacerbation (491.21), and CRI (585.9), respectively. Each may report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for medically necessary concurrent care:

- Hospitalist: 250.02, 491.21, 585.9;

- Pulmonologist: 491.21, 250.02, 585.9; and

- Nephrologist: 585.9, 492.21, 250.02.

Coverage Determinations

Code comparisons can be made after diagnosis code selection. Coverage determinations identify specific conditions (i.e. ICD-9-CM codes) for which services are considered medically necessary. They also outline the frequency interval at which services can be performed, when applicable.

For example, vascular studies (e.g. CPT 93971) are indicated for the preoperative examination (ICD-9-CM V72.83) of potential harvest vein grafts prior to bypass surgery.4 This is a covered service only when the results of the study are necessary to locate suitable graft vessels. The need for bypass surgery must be determined prior to performance of the test. V72.83 is “covered” only when reported for a unilateral study, not a bilateral study (CPT 93970). Frequency parameters allow for only one preoperative scan.4

Coverage determination can occur on two levels: national and local. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) develops national coverage determinations (NCDs) through an evidence-based process, with opportunities for public participation.5 All Medicare administrative contractors must abide by NCDs without imposing further limitations or guidelines. As example, the NCD “Consultations With a Beneficiary’s Family and Associates” permits a physician to provide counseling to family members. Family counseling services are covered only when the primary purpose of such counseling is the treatment of the patient’s condition.6

Non-Medicare payors do not have to follow federal guidelines unless the member participates in a Medicare managed-care plan.

In the absence of a national coverage policy, an item or service may be covered at the discretion of the Medicare contractors based on a local coverage determination (LCD).5 LCDs vary by state, creating an inconsistent approach to medical coverage. The vascular study guidelines listed above do not apply to all contractors. For example, Trailblazer Health Enterprises’ policy does not reference preoperative exams being limited to unilateral studies.7 (A listing of Medicare Contractor LCDs can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/04_LCDs.asp.)

Other Considerations

Investigate “medical necessity” denials. Do not take them at face value. Billing personnel often assume that the physician reported an incorrect diagnosis code. Consider the service when trying to formulate a response to the denial. Procedures (surgical or diagnostic services) may be denied for an invalid diagnosis. After reviewing the documentation to ensure that it supports the diagnosis, the claim may be resubmitted with a corrected diagnosis code, when applicable. Denials for frequency limitations can only be appealed with documentation that explicitly identifies the need for the service beyond the contractor-stated parameters.

If the “medical necessity” denial involves a covered evaluation and management (E/M) visit, it is less likely to be diagnosis-related. More likely, when dealing with Medicare contractors, the denial is the result of a failed response to a prepayment request for documentation. Medicare typically issues a request to review documentation prior to payment for the following inpatient E/M services: 99223, 99233, 99239, and 99292.

If the documentation is not provided to the Medicare prepayment review department within the designated time frame, the claim is automatically denied with a citation of “not deemed a medical necessity.” Acknowledge this remittance remark and do not assume that the physician assigned an incorrect diagnosis code. Although this is a possibility, it is more likely due to the failed request response. Appealing these claims requires submission of documentation to the Medicare appeals department. Reimbursement is provided once supportive documentation is received.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as a secondary payer. Social Security Administration website. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1862.htm. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Highmark Medicare Services. A/B Reference Manual: Chapter 6, Medical Coverage, Medical Necessity, and Medical Policy. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/refman/chapter-6.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Pohlig C. Daily care conundrums. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(12):18.

- Highmark Medicare Services. LCD L27506: Non-Invasive Peripheral Venous Studies. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/policy/mac-ab/l27506-r10.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage Determination Process: Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determination Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Trailblazer Health Enterprises. LCD 2866: Non-Invasive Venous Studies. Trailblazer Health Enterprises website. Available at: http://www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/LCDs.aspx?ID=2866. Accessed March 1, 2012.

Under Section 1862(a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).1 Coverage limitations include:2

- Proven clinical efficacy. For example, Medicare deems acupuncture “experimental/investigational” in the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury;

- Diagnoses. As an example, vitamin B-12 injections are covered, but only for such diagnoses as pernicious anemia and dementias secondary to vitamin B-12 deficiency; and

- Frequency/utilization parameters. For example, a screening colonoscopy (G0105) can be paid once every 24 months for beneficiaries who are at high risk for colorectal cancer; otherwise the service is limited to once every 10 years.

Beyond these factors, individual consideration might be granted. Supportive and unambiguous documentation (medical records, clinical studies, etc.) must be submitted when the clinical circumstances do not appear to support the medical necessity for the service.

Diagnoses Selection

Select the code that best represents the primary reason for the service or procedure on a given date. In the absence of a definitive diagnosis, the code may correspond to a sign or symptom. Physicians never should report a code that represents a probable, suspected, or “rule out” condition. Although facility billing might consider these unconfirmed circumstances (when necessary), physician billing prohibits this practice.

Reporting services for hospitalized patients is challenging when multiple services for the same patient are provided on the same date by the same or different physician, also known as concurrent care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while still considering the patient’s overall condition; each physician should report the corresponding diagnosis for that management. If billed correctly, each physician will have a different primary diagnosis code to justify their involvement, increasing their opportunity for payment.3

The non-primary diagnoses might also be listed on the claim if appropriately addressed in the documentation (i.e. “non-primary” conditions’ indirect role in the focused management of the primary condition). For example, a hospitalist, pulmonologist, and nephrologist manage a patient’s uncontrolled diabetes (250.02), COPD exacerbation (491.21), and CRI (585.9), respectively. Each may report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for medically necessary concurrent care:

- Hospitalist: 250.02, 491.21, 585.9;

- Pulmonologist: 491.21, 250.02, 585.9; and

- Nephrologist: 585.9, 492.21, 250.02.

Coverage Determinations

Code comparisons can be made after diagnosis code selection. Coverage determinations identify specific conditions (i.e. ICD-9-CM codes) for which services are considered medically necessary. They also outline the frequency interval at which services can be performed, when applicable.

For example, vascular studies (e.g. CPT 93971) are indicated for the preoperative examination (ICD-9-CM V72.83) of potential harvest vein grafts prior to bypass surgery.4 This is a covered service only when the results of the study are necessary to locate suitable graft vessels. The need for bypass surgery must be determined prior to performance of the test. V72.83 is “covered” only when reported for a unilateral study, not a bilateral study (CPT 93970). Frequency parameters allow for only one preoperative scan.4

Coverage determination can occur on two levels: national and local. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) develops national coverage determinations (NCDs) through an evidence-based process, with opportunities for public participation.5 All Medicare administrative contractors must abide by NCDs without imposing further limitations or guidelines. As example, the NCD “Consultations With a Beneficiary’s Family and Associates” permits a physician to provide counseling to family members. Family counseling services are covered only when the primary purpose of such counseling is the treatment of the patient’s condition.6

Non-Medicare payors do not have to follow federal guidelines unless the member participates in a Medicare managed-care plan.

In the absence of a national coverage policy, an item or service may be covered at the discretion of the Medicare contractors based on a local coverage determination (LCD).5 LCDs vary by state, creating an inconsistent approach to medical coverage. The vascular study guidelines listed above do not apply to all contractors. For example, Trailblazer Health Enterprises’ policy does not reference preoperative exams being limited to unilateral studies.7 (A listing of Medicare Contractor LCDs can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/04_LCDs.asp.)

Other Considerations

Investigate “medical necessity” denials. Do not take them at face value. Billing personnel often assume that the physician reported an incorrect diagnosis code. Consider the service when trying to formulate a response to the denial. Procedures (surgical or diagnostic services) may be denied for an invalid diagnosis. After reviewing the documentation to ensure that it supports the diagnosis, the claim may be resubmitted with a corrected diagnosis code, when applicable. Denials for frequency limitations can only be appealed with documentation that explicitly identifies the need for the service beyond the contractor-stated parameters.

If the “medical necessity” denial involves a covered evaluation and management (E/M) visit, it is less likely to be diagnosis-related. More likely, when dealing with Medicare contractors, the denial is the result of a failed response to a prepayment request for documentation. Medicare typically issues a request to review documentation prior to payment for the following inpatient E/M services: 99223, 99233, 99239, and 99292.

If the documentation is not provided to the Medicare prepayment review department within the designated time frame, the claim is automatically denied with a citation of “not deemed a medical necessity.” Acknowledge this remittance remark and do not assume that the physician assigned an incorrect diagnosis code. Although this is a possibility, it is more likely due to the failed request response. Appealing these claims requires submission of documentation to the Medicare appeals department. Reimbursement is provided once supportive documentation is received.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as a secondary payer. Social Security Administration website. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1862.htm. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Highmark Medicare Services. A/B Reference Manual: Chapter 6, Medical Coverage, Medical Necessity, and Medical Policy. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/refman/chapter-6.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Pohlig C. Daily care conundrums. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(12):18.

- Highmark Medicare Services. LCD L27506: Non-Invasive Peripheral Venous Studies. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/policy/mac-ab/l27506-r10.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage Determination Process: Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determination Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Trailblazer Health Enterprises. LCD 2866: Non-Invasive Venous Studies. Trailblazer Health Enterprises website. Available at: http://www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/LCDs.aspx?ID=2866. Accessed March 1, 2012.

Under Section 1862(a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).1 Coverage limitations include:2

- Proven clinical efficacy. For example, Medicare deems acupuncture “experimental/investigational” in the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury;

- Diagnoses. As an example, vitamin B-12 injections are covered, but only for such diagnoses as pernicious anemia and dementias secondary to vitamin B-12 deficiency; and

- Frequency/utilization parameters. For example, a screening colonoscopy (G0105) can be paid once every 24 months for beneficiaries who are at high risk for colorectal cancer; otherwise the service is limited to once every 10 years.

Beyond these factors, individual consideration might be granted. Supportive and unambiguous documentation (medical records, clinical studies, etc.) must be submitted when the clinical circumstances do not appear to support the medical necessity for the service.

Diagnoses Selection

Select the code that best represents the primary reason for the service or procedure on a given date. In the absence of a definitive diagnosis, the code may correspond to a sign or symptom. Physicians never should report a code that represents a probable, suspected, or “rule out” condition. Although facility billing might consider these unconfirmed circumstances (when necessary), physician billing prohibits this practice.

Reporting services for hospitalized patients is challenging when multiple services for the same patient are provided on the same date by the same or different physician, also known as concurrent care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while still considering the patient’s overall condition; each physician should report the corresponding diagnosis for that management. If billed correctly, each physician will have a different primary diagnosis code to justify their involvement, increasing their opportunity for payment.3

The non-primary diagnoses might also be listed on the claim if appropriately addressed in the documentation (i.e. “non-primary” conditions’ indirect role in the focused management of the primary condition). For example, a hospitalist, pulmonologist, and nephrologist manage a patient’s uncontrolled diabetes (250.02), COPD exacerbation (491.21), and CRI (585.9), respectively. Each may report subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) for medically necessary concurrent care:

- Hospitalist: 250.02, 491.21, 585.9;

- Pulmonologist: 491.21, 250.02, 585.9; and

- Nephrologist: 585.9, 492.21, 250.02.

Coverage Determinations

Code comparisons can be made after diagnosis code selection. Coverage determinations identify specific conditions (i.e. ICD-9-CM codes) for which services are considered medically necessary. They also outline the frequency interval at which services can be performed, when applicable.

For example, vascular studies (e.g. CPT 93971) are indicated for the preoperative examination (ICD-9-CM V72.83) of potential harvest vein grafts prior to bypass surgery.4 This is a covered service only when the results of the study are necessary to locate suitable graft vessels. The need for bypass surgery must be determined prior to performance of the test. V72.83 is “covered” only when reported for a unilateral study, not a bilateral study (CPT 93970). Frequency parameters allow for only one preoperative scan.4

Coverage determination can occur on two levels: national and local. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) develops national coverage determinations (NCDs) through an evidence-based process, with opportunities for public participation.5 All Medicare administrative contractors must abide by NCDs without imposing further limitations or guidelines. As example, the NCD “Consultations With a Beneficiary’s Family and Associates” permits a physician to provide counseling to family members. Family counseling services are covered only when the primary purpose of such counseling is the treatment of the patient’s condition.6

Non-Medicare payors do not have to follow federal guidelines unless the member participates in a Medicare managed-care plan.

In the absence of a national coverage policy, an item or service may be covered at the discretion of the Medicare contractors based on a local coverage determination (LCD).5 LCDs vary by state, creating an inconsistent approach to medical coverage. The vascular study guidelines listed above do not apply to all contractors. For example, Trailblazer Health Enterprises’ policy does not reference preoperative exams being limited to unilateral studies.7 (A listing of Medicare Contractor LCDs can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/04_LCDs.asp.)

Other Considerations

Investigate “medical necessity” denials. Do not take them at face value. Billing personnel often assume that the physician reported an incorrect diagnosis code. Consider the service when trying to formulate a response to the denial. Procedures (surgical or diagnostic services) may be denied for an invalid diagnosis. After reviewing the documentation to ensure that it supports the diagnosis, the claim may be resubmitted with a corrected diagnosis code, when applicable. Denials for frequency limitations can only be appealed with documentation that explicitly identifies the need for the service beyond the contractor-stated parameters.

If the “medical necessity” denial involves a covered evaluation and management (E/M) visit, it is less likely to be diagnosis-related. More likely, when dealing with Medicare contractors, the denial is the result of a failed response to a prepayment request for documentation. Medicare typically issues a request to review documentation prior to payment for the following inpatient E/M services: 99223, 99233, 99239, and 99292.

If the documentation is not provided to the Medicare prepayment review department within the designated time frame, the claim is automatically denied with a citation of “not deemed a medical necessity.” Acknowledge this remittance remark and do not assume that the physician assigned an incorrect diagnosis code. Although this is a possibility, it is more likely due to the failed request response. Appealing these claims requires submission of documentation to the Medicare appeals department. Reimbursement is provided once supportive documentation is received.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as a secondary payer. Social Security Administration website. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1862.htm. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Highmark Medicare Services. A/B Reference Manual: Chapter 6, Medical Coverage, Medical Necessity, and Medical Policy. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/refman/chapter-6.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Pohlig C. Daily care conundrums. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(12):18.

- Highmark Medicare Services. LCD L27506: Non-Invasive Peripheral Venous Studies. Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/policy/mac-ab/l27506-r10.html. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage Determination Process: Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DeterminationProcess/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determination Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2012.

- Trailblazer Health Enterprises. LCD 2866: Non-Invasive Venous Studies. Trailblazer Health Enterprises website. Available at: http://www.trailblazerhealth.com/Tools/LCDs.aspx?ID=2866. Accessed March 1, 2012.

HHS Delays ICD-10 Compliance Date

According to a CMS statement regarding part of President Obama’s “commitment to reducing regulatory burden,” Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius announced that HHS will initiate a process to “postpone the date” by which certain healthcare entities have to comply with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10).1

The final rule adopting ICD-10 as a standard was published in January 2009; it set a compliance date of Oct. 1, 2013 (a two-year delay from the 2008 proposed rule). HHS will announce a new compliance date moving forward.

“ICD-10 codes are important to many positive improvements in our healthcare system,” Sebelius said in the statement. “We have heard from many in the provider community who have concerns about the administrative burdens they face in the years ahead. We are committing to work with the provider community to re-examine the pace at which HHS and the nation implement these important improvements to our healthcare system.”

ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our healthcare data with that of the rest of the world, much of which has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes.

All that said, do not postpone any activities toward ICD-10 implementation until further clarification comes from CMS.

—Carol Pohlig

Reference