User login

Reimbursement Readiness

Doctors shouldn’t have to worry about financial issues. The welfare of our patients should be our only concern.

We should be able to devote our full attention to studying how best to serve the needs of the people we care for. We shouldn’t need to spend time learning about healthcare reform or things like ICD-9 (or ICD-10!)—things that don’t help us provide better care to patients.

But these are pie-in-the-sky dreams. As far as I can tell, all healthcare systems require caregivers to attend to economics and data management that aren’t directly tied to clinical care. Our system depends on all caregivers devoting some time to learn how the system is organized, and keeping up with how it evolves. And the crisis in runaway costs in U.S. healthcare only increases the need for all who work in healthcare to devote significant time (too much) to the operational (nonclinical side) of healthcare.

Hospitalist practice is a much simpler business to manage and operate than most forms of clinical practice. There usually is no building to rent, few nonclinical employees to manage, and a comparatively simple financial model. And if employed by a hospital or other large entity, nonclinicians handle most of the “business management.” So when it comes to the number of brain cells diverted to business rather than clinical concerns, hospitalists start with an advantage over most other specialties.

Still, we have a lot of nonclinical stuff to keep up with. Consider the concept of “managing to Medicare reimbursement.” This means managing a practice or hospital in a way that minimizes the failure to capture all appropriate Medicare reimbursement dollars. Even if you’ve never heard of this concept before, there are probably a lot of people at your hospital who have this as their main responsibility, and clinicians should know something about it.

So in an effort to distract the fewest brain cells away from clinical matters, here is a very simple overview of some components of managing to Medicare reimbursement relevant to hospitalists. This isn’t a comprehensive list, only some hospitalist-relevant highlights.

Medicare Reimbursement Today

Accurate determination of inpatient vs. observation status. Wow, this can get complicated. Most hospitals have people who devote significant time to doing this for patients every day, and even those experts sometimes disagree on the appropriate status. But all hospitalists should have a basic understanding of how this works and a willingness to answer questions from the hospital’s experts, and, when appropriate, write additional information in the chart to clarify the appropriate status.

Optimal resource utilization, including length of stay. Because Medicare pays an essentially fixed amount based on the diagnoses for each inpatient admission, managing costs is critical to a hospital’s financial well-being. Hospitalists have a huge role in this. And regardless of how Medicare reimburses for services, there is clinical rationale for being careful about resources used and how long someone stays in a hospital. In many cases, more is not better—and it even could be worse—for the patient.

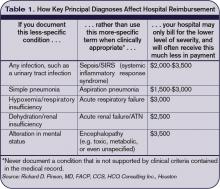

Optimal clinical documentation and accurate DRG assignment. Good documentation is important for clinical care, but beyond that, the precise way things are documented can have significant influence on Medicare reimbursement. Low potassium might in some cases lead to higher reimbursement, but a doctor must write “hypokalemia”; simply writing K+ means the hospital can’t include hypokalemia as a diagnosis. (A doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant must write out “hypokalemia” only once for Medicare purposes; it would then be fine to use K+ in the chart every other time.)

Say you have a patient with a UTI and sepsis. Write only “urosepsis,” and the hospital must bill for cystitis—low reimbursement. Write “urinary tract infection with sepsis,” and the hospital can bill for higher reimbursement.

There should be people at your hospital who are experts at this, and all hospitalists should work with them to learn appropriate documentation language to describe illnesses correctly for billing purposes. Many hospitals use a system of “DRG queries,” which hospitalists should always respond to (though they should agree with the issue raised, such as “was the pneumonia likely due to aspiration?” only when clinically appropriate).

Change Is Coming

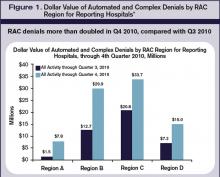

Don’t make the mistake of thinking Medicare reimbursement is a static phenomenon. It is undergoing rapid and significant evolution. For example, the Affordable Care Act, aka healthcare reform legislation, provides for a number of changes hospitalists need to understand.

I suggest that you make sure to understand your hospital’s or medical group’s position on accountable-care organizations (ACOs). It is a pretty complicated program that, in the first few years, has modest impact on reimbursement. If the ACO performs well, the additional reimbursement to an organization might pay for little more than the staff salaries of the staff that managed the considerable complexity of enrolling in and reporting for the program. And there is a risk the organization could lose money if it doesn’t perform well. So many organizations have decided not to pursue participation as an ACO, but they may decide to put in place most of the elements of an ACO without enrolling in the program. Some refer to this as an “aco” rather than an “ACO.”

Value-based purchasing (VBP) is set to influence hospital reimbursement rates starting in 2013 based on a hospital’s performance in 2012. SHM has a terrific VBP toolkit available online.

Bundled payments and financial penalties for readmissions also take effect in 2013. Now is the time ensure that you understand the implications of these programs; they are designed so that the financial impact to most organizations will be modest.

Reimbursement penalties for a specified list of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) will begin in 2015. Conditions most relevant for hospitalists include vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter-related urinary infection, or manifestations of poor glycemic control (HONK, DKA, hypo-/hyperglycemia).

I plan to address some of these programs in greater detail in future practice management columns.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Doctors shouldn’t have to worry about financial issues. The welfare of our patients should be our only concern.

We should be able to devote our full attention to studying how best to serve the needs of the people we care for. We shouldn’t need to spend time learning about healthcare reform or things like ICD-9 (or ICD-10!)—things that don’t help us provide better care to patients.

But these are pie-in-the-sky dreams. As far as I can tell, all healthcare systems require caregivers to attend to economics and data management that aren’t directly tied to clinical care. Our system depends on all caregivers devoting some time to learn how the system is organized, and keeping up with how it evolves. And the crisis in runaway costs in U.S. healthcare only increases the need for all who work in healthcare to devote significant time (too much) to the operational (nonclinical side) of healthcare.

Hospitalist practice is a much simpler business to manage and operate than most forms of clinical practice. There usually is no building to rent, few nonclinical employees to manage, and a comparatively simple financial model. And if employed by a hospital or other large entity, nonclinicians handle most of the “business management.” So when it comes to the number of brain cells diverted to business rather than clinical concerns, hospitalists start with an advantage over most other specialties.

Still, we have a lot of nonclinical stuff to keep up with. Consider the concept of “managing to Medicare reimbursement.” This means managing a practice or hospital in a way that minimizes the failure to capture all appropriate Medicare reimbursement dollars. Even if you’ve never heard of this concept before, there are probably a lot of people at your hospital who have this as their main responsibility, and clinicians should know something about it.

So in an effort to distract the fewest brain cells away from clinical matters, here is a very simple overview of some components of managing to Medicare reimbursement relevant to hospitalists. This isn’t a comprehensive list, only some hospitalist-relevant highlights.

Medicare Reimbursement Today

Accurate determination of inpatient vs. observation status. Wow, this can get complicated. Most hospitals have people who devote significant time to doing this for patients every day, and even those experts sometimes disagree on the appropriate status. But all hospitalists should have a basic understanding of how this works and a willingness to answer questions from the hospital’s experts, and, when appropriate, write additional information in the chart to clarify the appropriate status.

Optimal resource utilization, including length of stay. Because Medicare pays an essentially fixed amount based on the diagnoses for each inpatient admission, managing costs is critical to a hospital’s financial well-being. Hospitalists have a huge role in this. And regardless of how Medicare reimburses for services, there is clinical rationale for being careful about resources used and how long someone stays in a hospital. In many cases, more is not better—and it even could be worse—for the patient.

Optimal clinical documentation and accurate DRG assignment. Good documentation is important for clinical care, but beyond that, the precise way things are documented can have significant influence on Medicare reimbursement. Low potassium might in some cases lead to higher reimbursement, but a doctor must write “hypokalemia”; simply writing K+ means the hospital can’t include hypokalemia as a diagnosis. (A doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant must write out “hypokalemia” only once for Medicare purposes; it would then be fine to use K+ in the chart every other time.)

Say you have a patient with a UTI and sepsis. Write only “urosepsis,” and the hospital must bill for cystitis—low reimbursement. Write “urinary tract infection with sepsis,” and the hospital can bill for higher reimbursement.

There should be people at your hospital who are experts at this, and all hospitalists should work with them to learn appropriate documentation language to describe illnesses correctly for billing purposes. Many hospitals use a system of “DRG queries,” which hospitalists should always respond to (though they should agree with the issue raised, such as “was the pneumonia likely due to aspiration?” only when clinically appropriate).

Change Is Coming

Don’t make the mistake of thinking Medicare reimbursement is a static phenomenon. It is undergoing rapid and significant evolution. For example, the Affordable Care Act, aka healthcare reform legislation, provides for a number of changes hospitalists need to understand.

I suggest that you make sure to understand your hospital’s or medical group’s position on accountable-care organizations (ACOs). It is a pretty complicated program that, in the first few years, has modest impact on reimbursement. If the ACO performs well, the additional reimbursement to an organization might pay for little more than the staff salaries of the staff that managed the considerable complexity of enrolling in and reporting for the program. And there is a risk the organization could lose money if it doesn’t perform well. So many organizations have decided not to pursue participation as an ACO, but they may decide to put in place most of the elements of an ACO without enrolling in the program. Some refer to this as an “aco” rather than an “ACO.”

Value-based purchasing (VBP) is set to influence hospital reimbursement rates starting in 2013 based on a hospital’s performance in 2012. SHM has a terrific VBP toolkit available online.

Bundled payments and financial penalties for readmissions also take effect in 2013. Now is the time ensure that you understand the implications of these programs; they are designed so that the financial impact to most organizations will be modest.

Reimbursement penalties for a specified list of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) will begin in 2015. Conditions most relevant for hospitalists include vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter-related urinary infection, or manifestations of poor glycemic control (HONK, DKA, hypo-/hyperglycemia).

I plan to address some of these programs in greater detail in future practice management columns.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Doctors shouldn’t have to worry about financial issues. The welfare of our patients should be our only concern.

We should be able to devote our full attention to studying how best to serve the needs of the people we care for. We shouldn’t need to spend time learning about healthcare reform or things like ICD-9 (or ICD-10!)—things that don’t help us provide better care to patients.

But these are pie-in-the-sky dreams. As far as I can tell, all healthcare systems require caregivers to attend to economics and data management that aren’t directly tied to clinical care. Our system depends on all caregivers devoting some time to learn how the system is organized, and keeping up with how it evolves. And the crisis in runaway costs in U.S. healthcare only increases the need for all who work in healthcare to devote significant time (too much) to the operational (nonclinical side) of healthcare.

Hospitalist practice is a much simpler business to manage and operate than most forms of clinical practice. There usually is no building to rent, few nonclinical employees to manage, and a comparatively simple financial model. And if employed by a hospital or other large entity, nonclinicians handle most of the “business management.” So when it comes to the number of brain cells diverted to business rather than clinical concerns, hospitalists start with an advantage over most other specialties.

Still, we have a lot of nonclinical stuff to keep up with. Consider the concept of “managing to Medicare reimbursement.” This means managing a practice or hospital in a way that minimizes the failure to capture all appropriate Medicare reimbursement dollars. Even if you’ve never heard of this concept before, there are probably a lot of people at your hospital who have this as their main responsibility, and clinicians should know something about it.

So in an effort to distract the fewest brain cells away from clinical matters, here is a very simple overview of some components of managing to Medicare reimbursement relevant to hospitalists. This isn’t a comprehensive list, only some hospitalist-relevant highlights.

Medicare Reimbursement Today

Accurate determination of inpatient vs. observation status. Wow, this can get complicated. Most hospitals have people who devote significant time to doing this for patients every day, and even those experts sometimes disagree on the appropriate status. But all hospitalists should have a basic understanding of how this works and a willingness to answer questions from the hospital’s experts, and, when appropriate, write additional information in the chart to clarify the appropriate status.

Optimal resource utilization, including length of stay. Because Medicare pays an essentially fixed amount based on the diagnoses for each inpatient admission, managing costs is critical to a hospital’s financial well-being. Hospitalists have a huge role in this. And regardless of how Medicare reimburses for services, there is clinical rationale for being careful about resources used and how long someone stays in a hospital. In many cases, more is not better—and it even could be worse—for the patient.

Optimal clinical documentation and accurate DRG assignment. Good documentation is important for clinical care, but beyond that, the precise way things are documented can have significant influence on Medicare reimbursement. Low potassium might in some cases lead to higher reimbursement, but a doctor must write “hypokalemia”; simply writing K+ means the hospital can’t include hypokalemia as a diagnosis. (A doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant must write out “hypokalemia” only once for Medicare purposes; it would then be fine to use K+ in the chart every other time.)

Say you have a patient with a UTI and sepsis. Write only “urosepsis,” and the hospital must bill for cystitis—low reimbursement. Write “urinary tract infection with sepsis,” and the hospital can bill for higher reimbursement.

There should be people at your hospital who are experts at this, and all hospitalists should work with them to learn appropriate documentation language to describe illnesses correctly for billing purposes. Many hospitals use a system of “DRG queries,” which hospitalists should always respond to (though they should agree with the issue raised, such as “was the pneumonia likely due to aspiration?” only when clinically appropriate).

Change Is Coming

Don’t make the mistake of thinking Medicare reimbursement is a static phenomenon. It is undergoing rapid and significant evolution. For example, the Affordable Care Act, aka healthcare reform legislation, provides for a number of changes hospitalists need to understand.

I suggest that you make sure to understand your hospital’s or medical group’s position on accountable-care organizations (ACOs). It is a pretty complicated program that, in the first few years, has modest impact on reimbursement. If the ACO performs well, the additional reimbursement to an organization might pay for little more than the staff salaries of the staff that managed the considerable complexity of enrolling in and reporting for the program. And there is a risk the organization could lose money if it doesn’t perform well. So many organizations have decided not to pursue participation as an ACO, but they may decide to put in place most of the elements of an ACO without enrolling in the program. Some refer to this as an “aco” rather than an “ACO.”

Value-based purchasing (VBP) is set to influence hospital reimbursement rates starting in 2013 based on a hospital’s performance in 2012. SHM has a terrific VBP toolkit available online.

Bundled payments and financial penalties for readmissions also take effect in 2013. Now is the time ensure that you understand the implications of these programs; they are designed so that the financial impact to most organizations will be modest.

Reimbursement penalties for a specified list of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) will begin in 2015. Conditions most relevant for hospitalists include vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter-related urinary infection, or manifestations of poor glycemic control (HONK, DKA, hypo-/hyperglycemia).

I plan to address some of these programs in greater detail in future practice management columns.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Survey Insights: It's All Written in Code

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

Exam Guidelines

The extent of the exam should correspond to the nature of the presenting problem, the standard of care, and the physicians’ clinical judgment. Remember, medical necessity issues can arise if the physician performs and submits a claim for a comprehensive service involving a self-limiting problem. The easiest way to demonstrate the medical necessity for evaluation and management (E/M) services is through medical decision-making. It prevents a third party from making accusations that a Level 5 service was reported solely based upon a comprehensive history and examination that was not warranted by the patient’s presenting problem (e.g. the common cold).1

1995 Exam Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines differentiate 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory, gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).2 Physicians are permitted to perform and comment without mandate, as appropriate, but with a few minor directives:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems.

- Elaborate abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Documentation Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines are formatted as organ systems with corresponding, bulleted items referred to as “elements.”3 Additionally, a few elements have a numeric requirement to be achieved before satisfying the documentation of that particular element. For example, credit for the “vital signs element” (located within the constitutional system) is only awarded after documentation of three individual measurements (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Failure to document the specified criterion (e.g. two measurements: “blood pressure and heart rate only,” or a single nonspecific comment: “vital signs stable”) leads to failure to assign credit.

Take note that these specified criterion do not resonate within the 1995 guidelines. Numerical requirements also are indicated for the lymphatic system. The physician must examine and document findings associated with two or more lymphatic areas (e.g. “no lymphadenopathy noted in the neck or axillae”).

In the absence of numeric criterion, some elements contain multiple components, which require documentation of at least one component. For example, one listed psychiatric element designates the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” The physician receives credit for a comment regarding the patient’s mood (e.g. “appears depressed”) without identification of a flat (or normal).

The 1997 Documentation Guide-lines comprise the following systems and elements:

Constitutional

- Measurement of any three of the following seven vital signs:

- Sitting or standing blood pressure;

- Supine blood pressure;

- Pulse rate and regularity;

- Respiration;

- Temperature;

- Height; or

- Weight (can be measured and recorded by ancillary staff).

- General appearance of patient (e.g. development, nutrition, body habitus, deformities, attention to grooming)

Eyes

- Inspection of conjunctivae and lids;

- Examination of pupils and irises (e.g. reaction to light and accommodation, size, symmetry); and

- Ophthalmoscopic examination of optic discs (e.g. size, C/D ratio, appearance) and posterior segments (e.g. vessel changes, exudates, hemorrhages).

Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Throat

- External inspection of ears and nose (e.g. overall appearance, scars, lesions, masses);

- Otoscopic examination of external auditory canals and tympanic membranes;

- Assessment of hearing (e.g. whispered voice, finger rub, tuning fork);

- Inspection of nasal mucosa, septum, and turbinates;

- Inspection of lips, teeth, and gums; and

- Examination of oropharynx: oral mucosa, salivary glands, hard and soft palates, tongue, tonsils, and posterior pharynx.

Neck

- Examination of neck (e.g. masses, overall appearance, symmetry, tracheal position, crepitus); and

- Examination of thyroid (e.g. enlargement, tenderness, mass).

Respiratory

- Assessment of respiratory effort (e.g. intercostal retractions, use of accessory muscles, diaphragmatic movement);

- Percussion of chest (e.g. dullness, flatness, hyperresonance);

- Palpation of chest (e.g. tactile fremitus); and

- Auscultation of lungs (e.g. breath sounds, adventitious sounds, rubs).

Cardiovascular

- Palpation of heart (e.g. location, size, thrills);

- Auscultation of heart with notation of abnormal sounds and murmurs; and

- Examination of:

- Carotid arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Abdominal aorta (e.g. size, bruits);

- Femoral arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Pedal pulses (e.g. pulse amplitude); and

- Extremities for edema and/or varicosities.

Chest

- Inspection of breasts (e.g. symmetry, nipple discharge); and

- Palpation of breasts and axillae (e.g. masses or lumps, tenderness).

Gastrointestinal

- Examination of abdomen with notation of presence of masses or tenderness;

- Examination of liver and spleen;

- Examination for presence or absence of hernia;

- Examination (when indicated) of anus, perineum, and rectum, including sphincter tone, presence of hemorrhoids, and rectal masses; and

- Obtain stool sample for occult blood test when indicated.

Genitourinary (Male)

- Examination of the scrotal contents (e.g. hydrocele, spermatocele, tenderness of cord, testicular mass);

- Examination of the penis; and

- Digital rectal examination of prostate gland (e.g. size, symmetry, nodularity, tenderness).

Genitourinary (Female)

- Pelvic examination (with or without specimen collection for smears and cultures), including:

- Examination of external genitalia (e.g. general appearance, hair distribution, lesions) and vagina (e.g. general appearance, estrogen effect, discharge, lesions, pelvic support, cystocele, rectocele);

- Examination of urethra (e.g. masses, tenderness, scarring);

- Examination of bladder (e.g. fullness, masses, tenderness);

- Cervix (e.g. general appearance, lesions, discharge);

- Uterus (e.g. size, contour, position, mobility, tenderness, consistency, descent or support); and

- Adnexa/parametria (e.g. masses, tenderness, organomegaly, nodularity).

- Lymphatic Palpation of lymph nodes in two or more areas: Neck, axillae, groin, other.

Musculoskeletal

- Examination of gait and station;

- Inspection and/or palpation of digits and nails (e.g. clubbing, cyanosis, inflammatory conditions, petechiae, ischemia, infections, nodes);

- Examination of joints, bones and muscles of one or more of the following six areas:

- head and neck;

- spine, ribs and pelvis;

- right upper extremity;

- left upper extremity;

- right lower extremity; and

- left lower extremity.

The examination of a given area includes:

- Inspection and/or palpation with notation of presence of any misalignment, asymmetry, crepitation, defects, tenderness, masses, effusions;

- Assessment of range of motion with notation of any pain, crepitation or contracture;

- Assessment of stability with notation of any dislocation (luxation), subluxation or laxity; and

- Assessment of muscle strength and tone (e.g. flaccid, cog wheel, spastic) with notation of any atrophy or abnormal movements.

Skin

- Inspection of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. rashes, lesions, ulcers); and

- Palpation of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. induration, subcutaneous nodules, tightening).

Neurologic

- Test cranial nerves with notation of any deficits;

- Examination of deep tendon reflexes with notation of pathological reflexes (e.g. Babinski); and

- Examination of sensation (e.g. by touch, pin, vibration, proprioception).

Psychiatric

- Description of patient’s judgment and insight;

- Brief assessment of mental status, including:

- Orientation to time, place, and person;

- Recent and remote memory; and

- Mood and affect (e.g. depression, anxiety, agitation).

Considerations

The 1997 Documentation Guidelines often are criticized for their “specific” nature. Although this assists the auditor, it hinders the physician. The consequence is difficulty and frustration with remembering the explicit comments and number of elements associated with each level of exam. As a solution, consider documentation templates—paper or electronic—that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings with adequate space for elaboration of abnormal findings.

Remember that both sets of guidelines apply to visit level selection, and physicians may utilize either set when documenting their services. Auditors will review documentation with each of the guidelines, and assign the final audited result as the highest visit level supported during the comparison. Physicians should use the set that is best for their patients, practice, and peace of mind.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2009:87-118.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Highmark Medicare Services. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation And Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/faq/partb/pet/lpet-evaluation_management_services.html#10. Accessed Sept. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transmittal 2282: Clarification of Evaluation and Management Payment Policy. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R2282CP.pdf. Accessed Sept. 15, 2011.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

The extent of the exam should correspond to the nature of the presenting problem, the standard of care, and the physicians’ clinical judgment. Remember, medical necessity issues can arise if the physician performs and submits a claim for a comprehensive service involving a self-limiting problem. The easiest way to demonstrate the medical necessity for evaluation and management (E/M) services is through medical decision-making. It prevents a third party from making accusations that a Level 5 service was reported solely based upon a comprehensive history and examination that was not warranted by the patient’s presenting problem (e.g. the common cold).1

1995 Exam Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines differentiate 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory, gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).2 Physicians are permitted to perform and comment without mandate, as appropriate, but with a few minor directives:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems.

- Elaborate abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Documentation Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines are formatted as organ systems with corresponding, bulleted items referred to as “elements.”3 Additionally, a few elements have a numeric requirement to be achieved before satisfying the documentation of that particular element. For example, credit for the “vital signs element” (located within the constitutional system) is only awarded after documentation of three individual measurements (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Failure to document the specified criterion (e.g. two measurements: “blood pressure and heart rate only,” or a single nonspecific comment: “vital signs stable”) leads to failure to assign credit.

Take note that these specified criterion do not resonate within the 1995 guidelines. Numerical requirements also are indicated for the lymphatic system. The physician must examine and document findings associated with two or more lymphatic areas (e.g. “no lymphadenopathy noted in the neck or axillae”).

In the absence of numeric criterion, some elements contain multiple components, which require documentation of at least one component. For example, one listed psychiatric element designates the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” The physician receives credit for a comment regarding the patient’s mood (e.g. “appears depressed”) without identification of a flat (or normal).

The 1997 Documentation Guide-lines comprise the following systems and elements:

Constitutional

- Measurement of any three of the following seven vital signs:

- Sitting or standing blood pressure;

- Supine blood pressure;

- Pulse rate and regularity;

- Respiration;

- Temperature;

- Height; or

- Weight (can be measured and recorded by ancillary staff).

- General appearance of patient (e.g. development, nutrition, body habitus, deformities, attention to grooming)

Eyes

- Inspection of conjunctivae and lids;

- Examination of pupils and irises (e.g. reaction to light and accommodation, size, symmetry); and

- Ophthalmoscopic examination of optic discs (e.g. size, C/D ratio, appearance) and posterior segments (e.g. vessel changes, exudates, hemorrhages).

Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Throat

- External inspection of ears and nose (e.g. overall appearance, scars, lesions, masses);

- Otoscopic examination of external auditory canals and tympanic membranes;

- Assessment of hearing (e.g. whispered voice, finger rub, tuning fork);

- Inspection of nasal mucosa, septum, and turbinates;

- Inspection of lips, teeth, and gums; and

- Examination of oropharynx: oral mucosa, salivary glands, hard and soft palates, tongue, tonsils, and posterior pharynx.

Neck

- Examination of neck (e.g. masses, overall appearance, symmetry, tracheal position, crepitus); and

- Examination of thyroid (e.g. enlargement, tenderness, mass).

Respiratory

- Assessment of respiratory effort (e.g. intercostal retractions, use of accessory muscles, diaphragmatic movement);

- Percussion of chest (e.g. dullness, flatness, hyperresonance);

- Palpation of chest (e.g. tactile fremitus); and

- Auscultation of lungs (e.g. breath sounds, adventitious sounds, rubs).

Cardiovascular

- Palpation of heart (e.g. location, size, thrills);

- Auscultation of heart with notation of abnormal sounds and murmurs; and

- Examination of:

- Carotid arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Abdominal aorta (e.g. size, bruits);

- Femoral arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Pedal pulses (e.g. pulse amplitude); and

- Extremities for edema and/or varicosities.

Chest

- Inspection of breasts (e.g. symmetry, nipple discharge); and

- Palpation of breasts and axillae (e.g. masses or lumps, tenderness).

Gastrointestinal

- Examination of abdomen with notation of presence of masses or tenderness;

- Examination of liver and spleen;

- Examination for presence or absence of hernia;

- Examination (when indicated) of anus, perineum, and rectum, including sphincter tone, presence of hemorrhoids, and rectal masses; and

- Obtain stool sample for occult blood test when indicated.

Genitourinary (Male)

- Examination of the scrotal contents (e.g. hydrocele, spermatocele, tenderness of cord, testicular mass);

- Examination of the penis; and

- Digital rectal examination of prostate gland (e.g. size, symmetry, nodularity, tenderness).

Genitourinary (Female)

- Pelvic examination (with or without specimen collection for smears and cultures), including:

- Examination of external genitalia (e.g. general appearance, hair distribution, lesions) and vagina (e.g. general appearance, estrogen effect, discharge, lesions, pelvic support, cystocele, rectocele);

- Examination of urethra (e.g. masses, tenderness, scarring);

- Examination of bladder (e.g. fullness, masses, tenderness);

- Cervix (e.g. general appearance, lesions, discharge);

- Uterus (e.g. size, contour, position, mobility, tenderness, consistency, descent or support); and

- Adnexa/parametria (e.g. masses, tenderness, organomegaly, nodularity).

- Lymphatic Palpation of lymph nodes in two or more areas: Neck, axillae, groin, other.

Musculoskeletal

- Examination of gait and station;

- Inspection and/or palpation of digits and nails (e.g. clubbing, cyanosis, inflammatory conditions, petechiae, ischemia, infections, nodes);

- Examination of joints, bones and muscles of one or more of the following six areas:

- head and neck;

- spine, ribs and pelvis;

- right upper extremity;

- left upper extremity;

- right lower extremity; and

- left lower extremity.

The examination of a given area includes:

- Inspection and/or palpation with notation of presence of any misalignment, asymmetry, crepitation, defects, tenderness, masses, effusions;

- Assessment of range of motion with notation of any pain, crepitation or contracture;

- Assessment of stability with notation of any dislocation (luxation), subluxation or laxity; and

- Assessment of muscle strength and tone (e.g. flaccid, cog wheel, spastic) with notation of any atrophy or abnormal movements.

Skin

- Inspection of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. rashes, lesions, ulcers); and

- Palpation of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. induration, subcutaneous nodules, tightening).

Neurologic

- Test cranial nerves with notation of any deficits;

- Examination of deep tendon reflexes with notation of pathological reflexes (e.g. Babinski); and

- Examination of sensation (e.g. by touch, pin, vibration, proprioception).

Psychiatric

- Description of patient’s judgment and insight;

- Brief assessment of mental status, including:

- Orientation to time, place, and person;

- Recent and remote memory; and

- Mood and affect (e.g. depression, anxiety, agitation).

Considerations

The 1997 Documentation Guidelines often are criticized for their “specific” nature. Although this assists the auditor, it hinders the physician. The consequence is difficulty and frustration with remembering the explicit comments and number of elements associated with each level of exam. As a solution, consider documentation templates—paper or electronic—that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings with adequate space for elaboration of abnormal findings.

Remember that both sets of guidelines apply to visit level selection, and physicians may utilize either set when documenting their services. Auditors will review documentation with each of the guidelines, and assign the final audited result as the highest visit level supported during the comparison. Physicians should use the set that is best for their patients, practice, and peace of mind.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2009:87-118.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Highmark Medicare Services. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation And Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/faq/partb/pet/lpet-evaluation_management_services.html#10. Accessed Sept. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transmittal 2282: Clarification of Evaluation and Management Payment Policy. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R2282CP.pdf. Accessed Sept. 15, 2011.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

The extent of the exam should correspond to the nature of the presenting problem, the standard of care, and the physicians’ clinical judgment. Remember, medical necessity issues can arise if the physician performs and submits a claim for a comprehensive service involving a self-limiting problem. The easiest way to demonstrate the medical necessity for evaluation and management (E/M) services is through medical decision-making. It prevents a third party from making accusations that a Level 5 service was reported solely based upon a comprehensive history and examination that was not warranted by the patient’s presenting problem (e.g. the common cold).1

1995 Exam Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines differentiate 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory, gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).2 Physicians are permitted to perform and comment without mandate, as appropriate, but with a few minor directives:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems.

- Elaborate abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Documentation Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines are formatted as organ systems with corresponding, bulleted items referred to as “elements.”3 Additionally, a few elements have a numeric requirement to be achieved before satisfying the documentation of that particular element. For example, credit for the “vital signs element” (located within the constitutional system) is only awarded after documentation of three individual measurements (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Failure to document the specified criterion (e.g. two measurements: “blood pressure and heart rate only,” or a single nonspecific comment: “vital signs stable”) leads to failure to assign credit.

Take note that these specified criterion do not resonate within the 1995 guidelines. Numerical requirements also are indicated for the lymphatic system. The physician must examine and document findings associated with two or more lymphatic areas (e.g. “no lymphadenopathy noted in the neck or axillae”).

In the absence of numeric criterion, some elements contain multiple components, which require documentation of at least one component. For example, one listed psychiatric element designates the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” The physician receives credit for a comment regarding the patient’s mood (e.g. “appears depressed”) without identification of a flat (or normal).

The 1997 Documentation Guide-lines comprise the following systems and elements:

Constitutional

- Measurement of any three of the following seven vital signs:

- Sitting or standing blood pressure;

- Supine blood pressure;

- Pulse rate and regularity;

- Respiration;

- Temperature;

- Height; or

- Weight (can be measured and recorded by ancillary staff).

- General appearance of patient (e.g. development, nutrition, body habitus, deformities, attention to grooming)

Eyes

- Inspection of conjunctivae and lids;

- Examination of pupils and irises (e.g. reaction to light and accommodation, size, symmetry); and

- Ophthalmoscopic examination of optic discs (e.g. size, C/D ratio, appearance) and posterior segments (e.g. vessel changes, exudates, hemorrhages).

Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Throat

- External inspection of ears and nose (e.g. overall appearance, scars, lesions, masses);

- Otoscopic examination of external auditory canals and tympanic membranes;

- Assessment of hearing (e.g. whispered voice, finger rub, tuning fork);

- Inspection of nasal mucosa, septum, and turbinates;

- Inspection of lips, teeth, and gums; and

- Examination of oropharynx: oral mucosa, salivary glands, hard and soft palates, tongue, tonsils, and posterior pharynx.

Neck

- Examination of neck (e.g. masses, overall appearance, symmetry, tracheal position, crepitus); and

- Examination of thyroid (e.g. enlargement, tenderness, mass).

Respiratory

- Assessment of respiratory effort (e.g. intercostal retractions, use of accessory muscles, diaphragmatic movement);

- Percussion of chest (e.g. dullness, flatness, hyperresonance);

- Palpation of chest (e.g. tactile fremitus); and

- Auscultation of lungs (e.g. breath sounds, adventitious sounds, rubs).

Cardiovascular

- Palpation of heart (e.g. location, size, thrills);

- Auscultation of heart with notation of abnormal sounds and murmurs; and

- Examination of:

- Carotid arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Abdominal aorta (e.g. size, bruits);

- Femoral arteries (e.g. pulse amplitude, bruits);

- Pedal pulses (e.g. pulse amplitude); and

- Extremities for edema and/or varicosities.

Chest

- Inspection of breasts (e.g. symmetry, nipple discharge); and

- Palpation of breasts and axillae (e.g. masses or lumps, tenderness).

Gastrointestinal

- Examination of abdomen with notation of presence of masses or tenderness;

- Examination of liver and spleen;

- Examination for presence or absence of hernia;

- Examination (when indicated) of anus, perineum, and rectum, including sphincter tone, presence of hemorrhoids, and rectal masses; and

- Obtain stool sample for occult blood test when indicated.

Genitourinary (Male)

- Examination of the scrotal contents (e.g. hydrocele, spermatocele, tenderness of cord, testicular mass);

- Examination of the penis; and

- Digital rectal examination of prostate gland (e.g. size, symmetry, nodularity, tenderness).

Genitourinary (Female)

- Pelvic examination (with or without specimen collection for smears and cultures), including:

- Examination of external genitalia (e.g. general appearance, hair distribution, lesions) and vagina (e.g. general appearance, estrogen effect, discharge, lesions, pelvic support, cystocele, rectocele);

- Examination of urethra (e.g. masses, tenderness, scarring);

- Examination of bladder (e.g. fullness, masses, tenderness);

- Cervix (e.g. general appearance, lesions, discharge);

- Uterus (e.g. size, contour, position, mobility, tenderness, consistency, descent or support); and

- Adnexa/parametria (e.g. masses, tenderness, organomegaly, nodularity).

- Lymphatic Palpation of lymph nodes in two or more areas: Neck, axillae, groin, other.

Musculoskeletal

- Examination of gait and station;

- Inspection and/or palpation of digits and nails (e.g. clubbing, cyanosis, inflammatory conditions, petechiae, ischemia, infections, nodes);

- Examination of joints, bones and muscles of one or more of the following six areas:

- head and neck;

- spine, ribs and pelvis;

- right upper extremity;

- left upper extremity;

- right lower extremity; and

- left lower extremity.

The examination of a given area includes:

- Inspection and/or palpation with notation of presence of any misalignment, asymmetry, crepitation, defects, tenderness, masses, effusions;

- Assessment of range of motion with notation of any pain, crepitation or contracture;

- Assessment of stability with notation of any dislocation (luxation), subluxation or laxity; and

- Assessment of muscle strength and tone (e.g. flaccid, cog wheel, spastic) with notation of any atrophy or abnormal movements.

Skin

- Inspection of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. rashes, lesions, ulcers); and

- Palpation of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g. induration, subcutaneous nodules, tightening).

Neurologic

- Test cranial nerves with notation of any deficits;

- Examination of deep tendon reflexes with notation of pathological reflexes (e.g. Babinski); and

- Examination of sensation (e.g. by touch, pin, vibration, proprioception).

Psychiatric

- Description of patient’s judgment and insight;

- Brief assessment of mental status, including:

- Orientation to time, place, and person;

- Recent and remote memory; and

- Mood and affect (e.g. depression, anxiety, agitation).

Considerations

The 1997 Documentation Guidelines often are criticized for their “specific” nature. Although this assists the auditor, it hinders the physician. The consequence is difficulty and frustration with remembering the explicit comments and number of elements associated with each level of exam. As a solution, consider documentation templates—paper or electronic—that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings with adequate space for elaboration of abnormal findings.

Remember that both sets of guidelines apply to visit level selection, and physicians may utilize either set when documenting their services. Auditors will review documentation with each of the guidelines, and assign the final audited result as the highest visit level supported during the comparison. Physicians should use the set that is best for their patients, practice, and peace of mind.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2009:87-118.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Highmark Medicare Services. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation And Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/faq/partb/pet/lpet-evaluation_management_services.html#10. Accessed Sept. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transmittal 2282: Clarification of Evaluation and Management Payment Policy. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R2282CP.pdf. Accessed Sept. 15, 2011.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

A Brief History

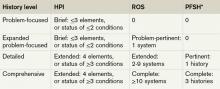

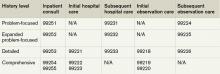

Each visit category and level of service has corresponding documentation requirements.1 Selecting an evaluation and management (E/M) level is based upon 1) the content of the three “key” components: history, exam, and decision-making, or 2) time, but only when counseling or coordination of care dominates more than 50% of the physician’s total visit time. Failure to document any essential element in a given visit level (e.g. family history required but missing for 99222 and 99223) could result in downcoding or service denial. Be aware of what an auditor expects when reviewing the key component of “history.”

Documentation Options

Auditors recognize two sets of documentation guidelines: “1995” and “1997” guidelines.2,3,4 Each set of guidelines has received valid criticism. The 1995 guidelines undoubtedly are vague and subjective in some areas, whereas the 1997 guidelines are known for arduous specificity.

However, to benefit all physicians and specialties, both sets of guidelines apply to visit-level selection. In other words, physicians can utilize either set when documenting their services, and auditors must review provider records against both styles. The final audited outcome reflects the highest visit level supported upon comparison.

Elements of History2,3,4

Chief complaint. The chief complaint (CC) is the reason for the visit, as stated in the patient’s own words. Every encounter, regardless of visit type, must include a CC. The physician must personally document and/or validate the CC with reference to a specific condition or symptom (e.g. patient complains of abdominal pain).

History of present illness (HPI). The HPI is a description of the patient’s present illness as it developed. It characteristically is referenced as location, quality, severity, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs/symptoms, as related to the chief complaint. The 1997 guidelines allow physicians to receive HPI credit for providing the status of the patient’s chronic or inactive conditions, such as “extrinsic asthma without acute exacerbation in past six months.” An auditor will not assign HPI credit to a chronic or inactive condition that does not have a corresponding status (e.g. “asthma”). This will be considered “past medical history.”

The HPI is classified as brief (a comment on <3 HPI elements, or the status of <2 conditions) or extended (a comment on >4 HPI elements, or the status of >3 conditions). Consider these examples of an extended HPI:

- “The patient has intermittent (duration), sharp (quality) pain in the right upper quadrant (location) without associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea (associated signs/symptoms).”

- “Diabetes controlled by oral medication; hyperlipidemia stable on simvastatin with increased dietary efforts; hypertension stable with pressures ranging from 130-140/80-90.” (Status of three chronic conditions.)

Physicians receive credit for confirming and personally documenting the HPI, or linking to documentation recorded by residents (residents, fellows, interns) or nonphysician providers (NPPs) when performing services according to the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules, respectively. An auditor will not assign physician credit for HPI elements documented by ancillary staff (registered nurses, medical assistants) or students.

Review of systems (ROS). The ROS is a series of questions used to elicit information about additional signs, symptoms, or problems currently or previously experienced by the patient: constitutional; eyes, ears, nose, mouth, throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary (including skin and/or breast); neurological; psychiatric; endocrine; hematologic/ lymphatic; and allergic/immunologic. Auditors classify the ROS as brief (a comment on one system), extended (a comment on two to nine systems), or complete (a comment on >10 systems). Physicians can document a complete ROS by noting individual systems: “no fever/chills (constitutional) or blurred vision (eyes); no chest pain (cardiovascular) or shortness of breath (respiratory); intermittent nausea (gastrointestinal); and occasional runny nose (ears, nose, mouth, throat),” or by eliciting a complete system review but documenting only the positive and pertinent negative findings related to the chief complaint, along with an additional comment that “all other systems are negative.”

Although the latter method is formally included in Medicare’s documentation guidelines and accepted by some Medicare contractors (e.g. Highmark, WPS), be aware that it is not universally accepted.5,6

Documentation involving the ROS can be provided by anyone, including the patient. The physician should reference ROS information that is completed by individuals other than residents or NPPs during services provided under the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules. Physician duplication of ROS information is unnecessary unless an update or revision is required.

Past, family, and social history (PFSH). The PFSH involves data obtained about the patient’s previous illness or medical conditions/therapies, family occurrences with illness, and relevant patient activities. The PFSH could be classified as pertinent (a comment on one history) or complete (a comment in each of the three histories). The physician merely needs a single comment associated with each history for the PFSH to be regarded as complete. Refrain from using “noncontributory” to describe any of the histories, as previous misuse of this term has resulted in its prohibition. An example of a complete PFSH documentation includes: “Patient currently on Prilosec 20 mg daily; family history of Barrett’s esophagus; no tobacco or alcohol use.”

Similar to the ROS, PFSH documentation can be provided by anyone, including the patient, and the physician should reference the documented PFSH in his own progress note. Redocumentation of the PFSH is not necessary unless a revision is required.

PFSH documentation is only required for initial care services (i.e. initial hospital care, initial observation care, consultations). It is not warranted in subsequent care services unless additional, pertinent information is obtained during the hospital stay that impacts care.

Considerations

When a physician cannot elicit historical information from the patient directly, and no other source is available, they should document “unable to obtain” the history. A comment regarding the circumstances surrounding this problem (e.g. patient confused, no caregiver present) should be provided, along with the available information from the limited resources (e.g. emergency medical technicians, previous hospitalizations at the same facility). Some contractors will not penalize the physician for the inability to ascertain complete historical information, as long as a proven attempt to obtain the information is evident.

Never document any item for the purpose of “getting paid.” Only document information that is clinically relevant, lends to the quality of care provided, or demonstrates the delivery of healthcare services. This prevents accusations of fraud and abuse, promotes billing compliance, and supports medical necessity for the services provided.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians, 2009; 87-118.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2011.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- History of E/M (Q&As). WPS Health Insurance website. Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/resources/provider_types/2009_0526_emqahistory.shtml. Accessed July 11, 2011.

- Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Highmark Medicare Services website. Available at: www.highmarkmedicareservices.com/faq/partb/pet/lpet-evaluation_management_services.html. Accessed on July 11, 2011.

Each visit category and level of service has corresponding documentation requirements.1 Selecting an evaluation and management (E/M) level is based upon 1) the content of the three “key” components: history, exam, and decision-making, or 2) time, but only when counseling or coordination of care dominates more than 50% of the physician’s total visit time. Failure to document any essential element in a given visit level (e.g. family history required but missing for 99222 and 99223) could result in downcoding or service denial. Be aware of what an auditor expects when reviewing the key component of “history.”

Documentation Options

Auditors recognize two sets of documentation guidelines: “1995” and “1997” guidelines.2,3,4 Each set of guidelines has received valid criticism. The 1995 guidelines undoubtedly are vague and subjective in some areas, whereas the 1997 guidelines are known for arduous specificity.

However, to benefit all physicians and specialties, both sets of guidelines apply to visit-level selection. In other words, physicians can utilize either set when documenting their services, and auditors must review provider records against both styles. The final audited outcome reflects the highest visit level supported upon comparison.

Elements of History2,3,4

Chief complaint. The chief complaint (CC) is the reason for the visit, as stated in the patient’s own words. Every encounter, regardless of visit type, must include a CC. The physician must personally document and/or validate the CC with reference to a specific condition or symptom (e.g. patient complains of abdominal pain).

History of present illness (HPI). The HPI is a description of the patient’s present illness as it developed. It characteristically is referenced as location, quality, severity, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs/symptoms, as related to the chief complaint. The 1997 guidelines allow physicians to receive HPI credit for providing the status of the patient’s chronic or inactive conditions, such as “extrinsic asthma without acute exacerbation in past six months.” An auditor will not assign HPI credit to a chronic or inactive condition that does not have a corresponding status (e.g. “asthma”). This will be considered “past medical history.”

The HPI is classified as brief (a comment on <3 HPI elements, or the status of <2 conditions) or extended (a comment on >4 HPI elements, or the status of >3 conditions). Consider these examples of an extended HPI:

- “The patient has intermittent (duration), sharp (quality) pain in the right upper quadrant (location) without associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea (associated signs/symptoms).”

- “Diabetes controlled by oral medication; hyperlipidemia stable on simvastatin with increased dietary efforts; hypertension stable with pressures ranging from 130-140/80-90.” (Status of three chronic conditions.)

Physicians receive credit for confirming and personally documenting the HPI, or linking to documentation recorded by residents (residents, fellows, interns) or nonphysician providers (NPPs) when performing services according to the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules, respectively. An auditor will not assign physician credit for HPI elements documented by ancillary staff (registered nurses, medical assistants) or students.

Review of systems (ROS). The ROS is a series of questions used to elicit information about additional signs, symptoms, or problems currently or previously experienced by the patient: constitutional; eyes, ears, nose, mouth, throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary (including skin and/or breast); neurological; psychiatric; endocrine; hematologic/ lymphatic; and allergic/immunologic. Auditors classify the ROS as brief (a comment on one system), extended (a comment on two to nine systems), or complete (a comment on >10 systems). Physicians can document a complete ROS by noting individual systems: “no fever/chills (constitutional) or blurred vision (eyes); no chest pain (cardiovascular) or shortness of breath (respiratory); intermittent nausea (gastrointestinal); and occasional runny nose (ears, nose, mouth, throat),” or by eliciting a complete system review but documenting only the positive and pertinent negative findings related to the chief complaint, along with an additional comment that “all other systems are negative.”

Although the latter method is formally included in Medicare’s documentation guidelines and accepted by some Medicare contractors (e.g. Highmark, WPS), be aware that it is not universally accepted.5,6

Documentation involving the ROS can be provided by anyone, including the patient. The physician should reference ROS information that is completed by individuals other than residents or NPPs during services provided under the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules. Physician duplication of ROS information is unnecessary unless an update or revision is required.

Past, family, and social history (PFSH). The PFSH involves data obtained about the patient’s previous illness or medical conditions/therapies, family occurrences with illness, and relevant patient activities. The PFSH could be classified as pertinent (a comment on one history) or complete (a comment in each of the three histories). The physician merely needs a single comment associated with each history for the PFSH to be regarded as complete. Refrain from using “noncontributory” to describe any of the histories, as previous misuse of this term has resulted in its prohibition. An example of a complete PFSH documentation includes: “Patient currently on Prilosec 20 mg daily; family history of Barrett’s esophagus; no tobacco or alcohol use.”