User login

Which Hospitalist Should Bill for Inpatient Stays with Multiple Providers?

During a facility stay, a patient could be attended to by more than one hospitalist. For example, perhaps one hospitalist is the admitting physician, but the patient has a three-day stay and may be seen by three different hospitalists. Are there any guidelines as to which physician should be billed on the facility claim? Thank you for any remarks, suggestions, or references.

—Anonymous

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Most of us can definitely relate to the concerns you have about properly billing during the patient’s hospital stay. By facility claim, I’m assuming you mean the physician’s bill for services rendered to a hospitalized patient. After querying the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) website and discussing the question with several of our coding and billing gurus, as far as I can tell, there are no specific guidelines pertaining to which physician in a multiphysician group should bill. CMS guidelines are clear that you should only bill for the services you provide. CMS is very specific about allowing only one physician of the same specialty billing per day (reference the CMS Manual, Chapter 12, 30.6.9-Payment for Inpatient Hospital Visits).

In our very large group, we bill daily for the individual inpatient services we provide. That way, when the bill goes out, the clinician author is responsible for its validity and can support the level of care as documented.

Billing and coding is such an arduous process, I can’t imagine attempting it without an electronic interface. Most hospitalist groups have some form of electronic billing software that has integrated checks and balances to catch the common mistakes. Improper billing done by anyone in the group can expose the entire group to an audit. With ICD-10 now upon us, this becomes ever more important.

Good luck!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

During a facility stay, a patient could be attended to by more than one hospitalist. For example, perhaps one hospitalist is the admitting physician, but the patient has a three-day stay and may be seen by three different hospitalists. Are there any guidelines as to which physician should be billed on the facility claim? Thank you for any remarks, suggestions, or references.

—Anonymous

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Most of us can definitely relate to the concerns you have about properly billing during the patient’s hospital stay. By facility claim, I’m assuming you mean the physician’s bill for services rendered to a hospitalized patient. After querying the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) website and discussing the question with several of our coding and billing gurus, as far as I can tell, there are no specific guidelines pertaining to which physician in a multiphysician group should bill. CMS guidelines are clear that you should only bill for the services you provide. CMS is very specific about allowing only one physician of the same specialty billing per day (reference the CMS Manual, Chapter 12, 30.6.9-Payment for Inpatient Hospital Visits).

In our very large group, we bill daily for the individual inpatient services we provide. That way, when the bill goes out, the clinician author is responsible for its validity and can support the level of care as documented.

Billing and coding is such an arduous process, I can’t imagine attempting it without an electronic interface. Most hospitalist groups have some form of electronic billing software that has integrated checks and balances to catch the common mistakes. Improper billing done by anyone in the group can expose the entire group to an audit. With ICD-10 now upon us, this becomes ever more important.

Good luck!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

During a facility stay, a patient could be attended to by more than one hospitalist. For example, perhaps one hospitalist is the admitting physician, but the patient has a three-day stay and may be seen by three different hospitalists. Are there any guidelines as to which physician should be billed on the facility claim? Thank you for any remarks, suggestions, or references.

—Anonymous

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Most of us can definitely relate to the concerns you have about properly billing during the patient’s hospital stay. By facility claim, I’m assuming you mean the physician’s bill for services rendered to a hospitalized patient. After querying the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) website and discussing the question with several of our coding and billing gurus, as far as I can tell, there are no specific guidelines pertaining to which physician in a multiphysician group should bill. CMS guidelines are clear that you should only bill for the services you provide. CMS is very specific about allowing only one physician of the same specialty billing per day (reference the CMS Manual, Chapter 12, 30.6.9-Payment for Inpatient Hospital Visits).

In our very large group, we bill daily for the individual inpatient services we provide. That way, when the bill goes out, the clinician author is responsible for its validity and can support the level of care as documented.

Billing and coding is such an arduous process, I can’t imagine attempting it without an electronic interface. Most hospitalist groups have some form of electronic billing software that has integrated checks and balances to catch the common mistakes. Improper billing done by anyone in the group can expose the entire group to an audit. With ICD-10 now upon us, this becomes ever more important.

Good luck!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Billing, Coding Documentation to Support Services, Minimize Risks

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

Medically Unlikely Edits

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUEs) are benchmarks recognized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that are designed to prevent incorrect or excessive coding. Specifically, an MUE is an edit that tests medical claims for services billed in excess of the maximum number of units of service permitted for a single beneficiary on the same date of service from the same provider (eg, multiples of the same Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] code listed on different claim lines).1

The MUE System

If the number of units of service billed by the same physician for the same patient on the same day exceeds the maximum number permitted by the CMS, the Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) will deny the code or return the claim to the provider for correction (return to provider [RTP]). Units of service billed in excess of the MUE will not be paid, but other services billed on the same claim form may still be paid. In the case of an MUE-associated RTP, the provider should resubmit a corrected claim, not an appeal; however, an appeal is possible in the case of an MUE-associated denial. An MUE-associated denial is a coding denial, not a medical necessity denial; therefore, the provider cannot use an Advance Beneficiary Notice to transfer liability for claim payment to the patient.

MUE Adjudication Indicators

In 2013, the CMS modified the MUE process to include 3 different MUE adjudication indicators (MAIs) with a value of 1, 2, or 3 so that some MUE values would be date of service edits rather than claim line edits.2 Medically Unlikely Edits for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 1 are identical to the prior claim line edits. If a provider needs to report excess units of service with an MAI of 1, appropriate modifiers should be used to report them on separate lines of a claim. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) modifiers such as -76 (repeat procedure or service by the same physician) and -91 (repeat clinical diagnostic laboratory test) as well as anatomic modifiers (eg, RT, LT, F1, F2) may be used, with modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) used only if no other modifier suffices. An example of an MUE with an MAI of 1 is CPT code 17264 (destruction, malignant lesion [eg, laser surgery, electrosurgery, cryosurgery, chemosurgery, surgical curettement], trunk, arms or legs; lesion diameter 3.1–4.0 cm), for which the MUE threshold is 3, meaning no more than 3 destructions can be submitted per claim line without triggering an edit-based rejection or RTP.

An MAI of 2 denotes absolute date of service edits, or so-called “per day edits based on policy.” Such edits are in place because units of service billed in excess of the MUE value on the same date of service are considered to be impossible by the CMS based on regulatory guidance or anatomic considerations.2 For instance, although the same physician may destroy multiple actinic keratoses in a single patient on the same date of service, it would not be possible to code more than one unit of service as

CPT code 17000, which specifically and exclusively

refers to the first lesion destroyed. Similarly,

CPT code 13101 (repair, complex, trunk; lesion diameter 2.6–7.5 cm) could only be reported once that day, as all complex repairs at that anatomic site must be summed and smaller or larger totals would be reported with another code.

Anatomic limitations are sometimes obvious and do not require specific coding rules. For example, only 1 gallbladder can be removed per patient. Although Qualified Independent Contractors and Administrative Law Judges are not bound by MAIs, they do give particular deference to an MAI of

2 given its definitive nature.2 Because ambulatory surgical center providers (Medicare specialty code 49) cannot report modifier -50 for bilateral

procedures, the MUE value used for editing is doubled for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 2 or 3 if the bilateral surgery indicator for the HCPCS code is 1.3

An MAI of 3 describes less strict date of service edits, so-called “per day edits based on clinical benchmarks.”2 Similar to MAIs of 1, MUEs for MAIs of 3 are based on medically likely daily frequencies of services provided in most settings. To determine if an MUE with an MAI of 3 has been reached, the MAC sums the units of service billed on all claim lines of the current claim as well as all prior paid claims for the same patient billed by the same provider on the same date of service. If the total units of service obtained in this manner exceeds the MUE value, then all claim lines with the relevant code for the current claim will be denied, but prior paid claims will not be adjusted. Denials based on MUEs for codes with an MAI of 3 can be appealed to the local MAC. Successful appeals require documentation that the units of service in excess of the MUE value were actually delivered and demonstration of medical necessity.2 An example of a CPT code with an MAI of 3 is 40490 (biopsy of lip) for which the MUE value is 3.

Complications With MUE and MAI

Because MUEs are based on current coding guidelines as well as current clinical practice, they are only applicable for the time period in which they are in effect. A change made to an MUE value for a particular code is not retroactive; however, in exceptional circumstances when a retroactive effective date is applied, MACs are not directed to examine prior claims but only “claims that are brought to their attention.”2

It also is important to realize that not all MUEs are publicly available and many are confidential. When claim denials occur, particularly in the context of multiple units of a particular code, automated MUE edits should be among the issues that are suspected. Physicians may resubmit RTP claims on separate lines if a claim line edit (MAI of 1) is operative. An MAI of 2 suggests a coding error that needs to be corrected, as these coding approaches are generally impossible based on definitional issues or anatomy. If an MUE with an MAI of 3 is the reason for denial, an appeal is possible, provided there is documentation to show that the service was actually provided and that it was medically necessary.

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists should be vigilant for unexpected payment denials, which may coincide with the implementation of new MUE values. When such denials occur and MUE values are publicly available, dermatologists should consider filing an appeal if the relevant MUEs were associated with an MAI of 1 or 3. Overall, dermatologists should be aware that many MUEs that were formerly claim line edits (MAI of 1) have been recently transitioned to date of service edits (MAI of 3), which are more restrictive.

1. American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare’s expanded medically unlikely edits. https://www.aad.org/members

/practice-and-advocacy-resource-center/coding-resources

/derm-coding-consult-library/winter-2014/medicare-

s-expanded-medically-unlikely-edits. Published Winter 2014. Accessed August 6, 2015.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised modification to the Medically Unlikely Edit (MUE) program. MLN Matters. Number MM8853. https://www.cms.gov

/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM8853.pdf. Published January 1, 2015. Accessed August 6, 2015.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUE) and bilateral procedures. MLN Matters. Number SE1422.

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance

/Guidance/Transmittals/2014-Transmittals-Items/SE1422.html?DLPage=2&DLEntries=10&DLSort=1&DLSort

Dir=ascending. Accessed July 28, 2015.

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUEs) are benchmarks recognized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that are designed to prevent incorrect or excessive coding. Specifically, an MUE is an edit that tests medical claims for services billed in excess of the maximum number of units of service permitted for a single beneficiary on the same date of service from the same provider (eg, multiples of the same Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] code listed on different claim lines).1

The MUE System

If the number of units of service billed by the same physician for the same patient on the same day exceeds the maximum number permitted by the CMS, the Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) will deny the code or return the claim to the provider for correction (return to provider [RTP]). Units of service billed in excess of the MUE will not be paid, but other services billed on the same claim form may still be paid. In the case of an MUE-associated RTP, the provider should resubmit a corrected claim, not an appeal; however, an appeal is possible in the case of an MUE-associated denial. An MUE-associated denial is a coding denial, not a medical necessity denial; therefore, the provider cannot use an Advance Beneficiary Notice to transfer liability for claim payment to the patient.

MUE Adjudication Indicators

In 2013, the CMS modified the MUE process to include 3 different MUE adjudication indicators (MAIs) with a value of 1, 2, or 3 so that some MUE values would be date of service edits rather than claim line edits.2 Medically Unlikely Edits for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 1 are identical to the prior claim line edits. If a provider needs to report excess units of service with an MAI of 1, appropriate modifiers should be used to report them on separate lines of a claim. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) modifiers such as -76 (repeat procedure or service by the same physician) and -91 (repeat clinical diagnostic laboratory test) as well as anatomic modifiers (eg, RT, LT, F1, F2) may be used, with modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) used only if no other modifier suffices. An example of an MUE with an MAI of 1 is CPT code 17264 (destruction, malignant lesion [eg, laser surgery, electrosurgery, cryosurgery, chemosurgery, surgical curettement], trunk, arms or legs; lesion diameter 3.1–4.0 cm), for which the MUE threshold is 3, meaning no more than 3 destructions can be submitted per claim line without triggering an edit-based rejection or RTP.

An MAI of 2 denotes absolute date of service edits, or so-called “per day edits based on policy.” Such edits are in place because units of service billed in excess of the MUE value on the same date of service are considered to be impossible by the CMS based on regulatory guidance or anatomic considerations.2 For instance, although the same physician may destroy multiple actinic keratoses in a single patient on the same date of service, it would not be possible to code more than one unit of service as

CPT code 17000, which specifically and exclusively

refers to the first lesion destroyed. Similarly,

CPT code 13101 (repair, complex, trunk; lesion diameter 2.6–7.5 cm) could only be reported once that day, as all complex repairs at that anatomic site must be summed and smaller or larger totals would be reported with another code.

Anatomic limitations are sometimes obvious and do not require specific coding rules. For example, only 1 gallbladder can be removed per patient. Although Qualified Independent Contractors and Administrative Law Judges are not bound by MAIs, they do give particular deference to an MAI of

2 given its definitive nature.2 Because ambulatory surgical center providers (Medicare specialty code 49) cannot report modifier -50 for bilateral

procedures, the MUE value used for editing is doubled for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 2 or 3 if the bilateral surgery indicator for the HCPCS code is 1.3

An MAI of 3 describes less strict date of service edits, so-called “per day edits based on clinical benchmarks.”2 Similar to MAIs of 1, MUEs for MAIs of 3 are based on medically likely daily frequencies of services provided in most settings. To determine if an MUE with an MAI of 3 has been reached, the MAC sums the units of service billed on all claim lines of the current claim as well as all prior paid claims for the same patient billed by the same provider on the same date of service. If the total units of service obtained in this manner exceeds the MUE value, then all claim lines with the relevant code for the current claim will be denied, but prior paid claims will not be adjusted. Denials based on MUEs for codes with an MAI of 3 can be appealed to the local MAC. Successful appeals require documentation that the units of service in excess of the MUE value were actually delivered and demonstration of medical necessity.2 An example of a CPT code with an MAI of 3 is 40490 (biopsy of lip) for which the MUE value is 3.

Complications With MUE and MAI

Because MUEs are based on current coding guidelines as well as current clinical practice, they are only applicable for the time period in which they are in effect. A change made to an MUE value for a particular code is not retroactive; however, in exceptional circumstances when a retroactive effective date is applied, MACs are not directed to examine prior claims but only “claims that are brought to their attention.”2

It also is important to realize that not all MUEs are publicly available and many are confidential. When claim denials occur, particularly in the context of multiple units of a particular code, automated MUE edits should be among the issues that are suspected. Physicians may resubmit RTP claims on separate lines if a claim line edit (MAI of 1) is operative. An MAI of 2 suggests a coding error that needs to be corrected, as these coding approaches are generally impossible based on definitional issues or anatomy. If an MUE with an MAI of 3 is the reason for denial, an appeal is possible, provided there is documentation to show that the service was actually provided and that it was medically necessary.

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists should be vigilant for unexpected payment denials, which may coincide with the implementation of new MUE values. When such denials occur and MUE values are publicly available, dermatologists should consider filing an appeal if the relevant MUEs were associated with an MAI of 1 or 3. Overall, dermatologists should be aware that many MUEs that were formerly claim line edits (MAI of 1) have been recently transitioned to date of service edits (MAI of 3), which are more restrictive.

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUEs) are benchmarks recognized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that are designed to prevent incorrect or excessive coding. Specifically, an MUE is an edit that tests medical claims for services billed in excess of the maximum number of units of service permitted for a single beneficiary on the same date of service from the same provider (eg, multiples of the same Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] code listed on different claim lines).1

The MUE System

If the number of units of service billed by the same physician for the same patient on the same day exceeds the maximum number permitted by the CMS, the Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) will deny the code or return the claim to the provider for correction (return to provider [RTP]). Units of service billed in excess of the MUE will not be paid, but other services billed on the same claim form may still be paid. In the case of an MUE-associated RTP, the provider should resubmit a corrected claim, not an appeal; however, an appeal is possible in the case of an MUE-associated denial. An MUE-associated denial is a coding denial, not a medical necessity denial; therefore, the provider cannot use an Advance Beneficiary Notice to transfer liability for claim payment to the patient.

MUE Adjudication Indicators

In 2013, the CMS modified the MUE process to include 3 different MUE adjudication indicators (MAIs) with a value of 1, 2, or 3 so that some MUE values would be date of service edits rather than claim line edits.2 Medically Unlikely Edits for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 1 are identical to the prior claim line edits. If a provider needs to report excess units of service with an MAI of 1, appropriate modifiers should be used to report them on separate lines of a claim. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) modifiers such as -76 (repeat procedure or service by the same physician) and -91 (repeat clinical diagnostic laboratory test) as well as anatomic modifiers (eg, RT, LT, F1, F2) may be used, with modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) used only if no other modifier suffices. An example of an MUE with an MAI of 1 is CPT code 17264 (destruction, malignant lesion [eg, laser surgery, electrosurgery, cryosurgery, chemosurgery, surgical curettement], trunk, arms or legs; lesion diameter 3.1–4.0 cm), for which the MUE threshold is 3, meaning no more than 3 destructions can be submitted per claim line without triggering an edit-based rejection or RTP.

An MAI of 2 denotes absolute date of service edits, or so-called “per day edits based on policy.” Such edits are in place because units of service billed in excess of the MUE value on the same date of service are considered to be impossible by the CMS based on regulatory guidance or anatomic considerations.2 For instance, although the same physician may destroy multiple actinic keratoses in a single patient on the same date of service, it would not be possible to code more than one unit of service as

CPT code 17000, which specifically and exclusively

refers to the first lesion destroyed. Similarly,

CPT code 13101 (repair, complex, trunk; lesion diameter 2.6–7.5 cm) could only be reported once that day, as all complex repairs at that anatomic site must be summed and smaller or larger totals would be reported with another code.

Anatomic limitations are sometimes obvious and do not require specific coding rules. For example, only 1 gallbladder can be removed per patient. Although Qualified Independent Contractors and Administrative Law Judges are not bound by MAIs, they do give particular deference to an MAI of

2 given its definitive nature.2 Because ambulatory surgical center providers (Medicare specialty code 49) cannot report modifier -50 for bilateral

procedures, the MUE value used for editing is doubled for HCPCS codes with an MAI of 2 or 3 if the bilateral surgery indicator for the HCPCS code is 1.3

An MAI of 3 describes less strict date of service edits, so-called “per day edits based on clinical benchmarks.”2 Similar to MAIs of 1, MUEs for MAIs of 3 are based on medically likely daily frequencies of services provided in most settings. To determine if an MUE with an MAI of 3 has been reached, the MAC sums the units of service billed on all claim lines of the current claim as well as all prior paid claims for the same patient billed by the same provider on the same date of service. If the total units of service obtained in this manner exceeds the MUE value, then all claim lines with the relevant code for the current claim will be denied, but prior paid claims will not be adjusted. Denials based on MUEs for codes with an MAI of 3 can be appealed to the local MAC. Successful appeals require documentation that the units of service in excess of the MUE value were actually delivered and demonstration of medical necessity.2 An example of a CPT code with an MAI of 3 is 40490 (biopsy of lip) for which the MUE value is 3.

Complications With MUE and MAI

Because MUEs are based on current coding guidelines as well as current clinical practice, they are only applicable for the time period in which they are in effect. A change made to an MUE value for a particular code is not retroactive; however, in exceptional circumstances when a retroactive effective date is applied, MACs are not directed to examine prior claims but only “claims that are brought to their attention.”2

It also is important to realize that not all MUEs are publicly available and many are confidential. When claim denials occur, particularly in the context of multiple units of a particular code, automated MUE edits should be among the issues that are suspected. Physicians may resubmit RTP claims on separate lines if a claim line edit (MAI of 1) is operative. An MAI of 2 suggests a coding error that needs to be corrected, as these coding approaches are generally impossible based on definitional issues or anatomy. If an MUE with an MAI of 3 is the reason for denial, an appeal is possible, provided there is documentation to show that the service was actually provided and that it was medically necessary.

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists should be vigilant for unexpected payment denials, which may coincide with the implementation of new MUE values. When such denials occur and MUE values are publicly available, dermatologists should consider filing an appeal if the relevant MUEs were associated with an MAI of 1 or 3. Overall, dermatologists should be aware that many MUEs that were formerly claim line edits (MAI of 1) have been recently transitioned to date of service edits (MAI of 3), which are more restrictive.

1. American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare’s expanded medically unlikely edits. https://www.aad.org/members

/practice-and-advocacy-resource-center/coding-resources

/derm-coding-consult-library/winter-2014/medicare-

s-expanded-medically-unlikely-edits. Published Winter 2014. Accessed August 6, 2015.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised modification to the Medically Unlikely Edit (MUE) program. MLN Matters. Number MM8853. https://www.cms.gov

/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM8853.pdf. Published January 1, 2015. Accessed August 6, 2015.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUE) and bilateral procedures. MLN Matters. Number SE1422.

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance

/Guidance/Transmittals/2014-Transmittals-Items/SE1422.html?DLPage=2&DLEntries=10&DLSort=1&DLSort

Dir=ascending. Accessed July 28, 2015.

1. American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare’s expanded medically unlikely edits. https://www.aad.org/members

/practice-and-advocacy-resource-center/coding-resources

/derm-coding-consult-library/winter-2014/medicare-

s-expanded-medically-unlikely-edits. Published Winter 2014. Accessed August 6, 2015.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised modification to the Medically Unlikely Edit (MUE) program. MLN Matters. Number MM8853. https://www.cms.gov

/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM8853.pdf. Published January 1, 2015. Accessed August 6, 2015.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Medically Unlikely Edits (MUE) and bilateral procedures. MLN Matters. Number SE1422.

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance

/Guidance/Transmittals/2014-Transmittals-Items/SE1422.html?DLPage=2&DLEntries=10&DLSort=1&DLSort

Dir=ascending. Accessed July 28, 2015.

Practice Points

- Medically Unlikely Edits (MUEs) are designed to prevent incorrect or excessive coding. Units of service billed in excess of the MUE will not be paid.

- Three different MUE adjudication indicators (MAIs) were added so that some MUE values would be date of service edits.

- Dermatologists should be vigilant for unexpected payment denials.

Is Your Electronic Health Record Putting You at Risk for a Documentation Audit?

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.

“If you pull in unnecessary history or exam information from a previous visit that’s not relevant to the current visit, you can get dinged in an audit for not customizing the note to the patient’s specific presenting complaint,” LeGrand explains, “or, for attempting to bill a higher-level code by unintentionally padding the note with irrelevant information. What is documented for ‘reference’ has to be separated from what can be used to select the level of service.”

Your first documentation risk-reduction strategy is to review notes and look for signs of cloning.

LeGrand explains that a practice may be predisposed to cloning simply because of the way the EHR templates and workflow were set up when the system was implemented. “But,” she says, “‘the EHR made me do it’ defense won’t hold water, because it’s still the physician’s responsibility to customize or remove the information from templates and make the note unique to the visit.”

Yes, physician time is precious. But the reality is that the onus is on the physician to integrate EHR features with clinic workflow and to follow documentation rules.

The second documentation risk-reduction strategy is to make sure the level of evaluation and management (E/M) service billed is supported by medical necessity, not only by documentation artifacts that were relevant to the patient in the past but irrelevant to his or her current presenting complaint or condition.

“Medicare won’t pay for services that aren’t supported by medical necessity,” says LeGrand, “and you can’t achieve medical necessity by simply documenting additional E/M elements.”

This has always been the rule, LeGrand says. “But with the increased use of EHRs, and templates that automatically document visit elements and drive visits to a higher level of service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and private payers have added scrutiny to medical necessity reviews. They want to validate that higher-level visits billed indeed required a higher level of history and/or exam.”

To do this, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has supplemented its audit team with registered nurses. “The nurses assist certified coders by determining whether medical necessity has been met,” explains LeGrand.

Look at a patient who presents with toe pain. You take a detailed family history, conduct a review of systems (ROS), bill a high-level code, and document all the elements to support it. LeGrand explains, “There is no medical necessity to support doing an eye exam for a patient with toe pain in the absence of any other medical history, or performing a ROS to correlate an eye exam with toe pain. So, even if you do it and document it, the higher-level code won’t pass muster in an audit because the information documented is not medically necessary.”

According to LeGrand, the extent of the history and examination should be based on the presenting problem and the patient’s condition. “If an ankle sprain patient returns 2 weeks after the initial evaluation of the injury with a negative medical or surgical history, and the patient has been treated conservatively, it’s probably not necessary to conduct a ROS that includes 10 organ systems,” she says. “If your standard of care is to perform this level of service, no one will fault you for your care delivery; however, if you also choose a level of service based on this system review, without relevance to the presenting problem, and you bill a higher level of service than is supported by the nature of the presenting problem or the plan of care, the documentation probably won’t hold up in an audit where medical necessity is valued into the equation.”

On the other hand, LeGrand adds, if a patient presents to the emergency department after an automobile accident with an open fracture and other injuries, and the surgeon performs a complete ROS, the medical necessity would most likely be supported as the surgeon is preparing the patient for surgery.

Based on LeGrand’s work with practices, this distinction about medical necessity is news to many nonclinical billing staff. “They confuse medical necessity with medical decision-making, an E/M code documentation component, and incorrectly bill for a high-level visit because medical decision-making elements meet the documentation requirements—yet the code is not supported by medical necessity of the presenting problem.”

Talk with your billing team to make sure all staff members understand this critical difference. They must comprehend that the medically necessary level of service is determined by a number of clinical factors, not medical decision-making. Describe some of these clinical factors, which include, but are not limited to, chief complaint, clinical judgment, standards of practice, acute exacerbations/onsets of medical conditions or injuries, and comorbidities.

EHR Dos and Don’ts

LeGrand recommends the following best practices for using EHR documentation features:

1. DON’T simply cut and paste from a previous note. “This is what leads to verbose notes that have little to do with the patient you are documenting,” she says. “If you don’t cut and paste, you’ll avoid the root cause of this risk.”

2. DON’T pull forward information from previous visit notes that have nothing to do with the nature of the patient’s problem. “We understand that this takes extra time because physicians must review the previous note,” LeGrand says. “So if you don’t have time to review the past note, just don’t pull it forward. Start fresh with a new drop-down menu and select elements pertinent to the current visit. Or, dictate or type a note relevant to the current condition and presenting problems.”

How you choose to work this into your process will vary depending on which EHR system you use. “One surgeon I work with dictates everything because the drop-down menus and templates are cumbersome,” LeGrand says. “Some groups find it faster to use the EHR templates that they have customized. Others find their EHR’s point-and-click features most efficient for customizing quickly.”

3. DO customize your EHR visit templates if the use of templates is critical to your efficiency. “This is the most overlooked step in the EHR implementation process because it takes a fair amount of time to do,” LeGrand says. She suggests avoiding the use of multisystem examination templates created for medicine specialties altogether, and insists, “Don’t assume ‘that is how the vendor built it so we have to use it.’ Customize a template for each of your visit types so you can document in the EHR in the same fashion as when you used a paper system. Doing so will save you loads of documentation time.”

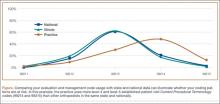

4. DO review your E/M code distribution. Generate a CPT frequency report for each physician and for the practice as a whole. Compare the data with state and national usage in orthopedics as a baseline. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon’s Code-X tool enables easy comparison of your practice’s E/M code usage with state and national data for orthopedics. Simply generate a CPT frequency report from your practice management system and enter the E/M data. Line graphs are automatically generated, making trends and patterns easy to see (Figure).

“Identify your outliers, pull charts randomly, and review the notes,” recommends LeGrand. “Make sure there is medical necessity for the level of code that’s been billed and that documentation supports it.”

You may be surprised to find you are an outlier on inpatient hospital codes, or your distribution of level-2 or -3 codes varies from your practice, state, or national data. Orthopedic surgeons don’t typically report high volumes of CPT codes 99204, 99205 or 99215, but if your practice does and you are an outlier, best to pay attention before someone else does.

5. DO select auditors with the right skill sets. Evaluating medical necessity in the note requires a clinical background. “If internal documentation reviews are conducted by the billing team, that’s fine,” LeGrand advises. “Just add a physician assistant or nurse to your internal review team. They can provide clinical oversight and review the note when necessary for medical necessity.”

If you are contracting with external auditors or consultants, verify auditor credentials and skill sets to ensure they can abstract and incorporate medical necessity into the review. “Auditors must be able to do more than count elements,” LeGrand says. “They must have clinical knowledge, and expertise in orthopedics is critical. This knowledge should be used to verify that medical necessity is present in every note.” LeGrand is quick to point out that not every note will be at risk, based on the amount of work performed and documented and the level of service billed. “But medical necessity must always be present.”

The addition of nurses to the OIG’s audit team is a big change and will refine the auditing process by adding more clinical scrutiny. The EHR documentation features are intended to improve efficiency, but only a clinician can determine and document unique visit elements and medical necessity.

Address these intersections of risk by ensuring your documentation meets medical necessity as well as E/M documentation elements. Conduct internal audits bi-annually to verify that E/M usage patterns align with peers and physician documentation is appropriate. And be sure there is clinical expertise on your audit team, whether it is internal or external. CMS now has it, and your practice should too. ◾

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.

“If you pull in unnecessary history or exam information from a previous visit that’s not relevant to the current visit, you can get dinged in an audit for not customizing the note to the patient’s specific presenting complaint,” LeGrand explains, “or, for attempting to bill a higher-level code by unintentionally padding the note with irrelevant information. What is documented for ‘reference’ has to be separated from what can be used to select the level of service.”

Your first documentation risk-reduction strategy is to review notes and look for signs of cloning.

LeGrand explains that a practice may be predisposed to cloning simply because of the way the EHR templates and workflow were set up when the system was implemented. “But,” she says, “‘the EHR made me do it’ defense won’t hold water, because it’s still the physician’s responsibility to customize or remove the information from templates and make the note unique to the visit.”

Yes, physician time is precious. But the reality is that the onus is on the physician to integrate EHR features with clinic workflow and to follow documentation rules.

The second documentation risk-reduction strategy is to make sure the level of evaluation and management (E/M) service billed is supported by medical necessity, not only by documentation artifacts that were relevant to the patient in the past but irrelevant to his or her current presenting complaint or condition.

“Medicare won’t pay for services that aren’t supported by medical necessity,” says LeGrand, “and you can’t achieve medical necessity by simply documenting additional E/M elements.”

This has always been the rule, LeGrand says. “But with the increased use of EHRs, and templates that automatically document visit elements and drive visits to a higher level of service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and private payers have added scrutiny to medical necessity reviews. They want to validate that higher-level visits billed indeed required a higher level of history and/or exam.”

To do this, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has supplemented its audit team with registered nurses. “The nurses assist certified coders by determining whether medical necessity has been met,” explains LeGrand.

Look at a patient who presents with toe pain. You take a detailed family history, conduct a review of systems (ROS), bill a high-level code, and document all the elements to support it. LeGrand explains, “There is no medical necessity to support doing an eye exam for a patient with toe pain in the absence of any other medical history, or performing a ROS to correlate an eye exam with toe pain. So, even if you do it and document it, the higher-level code won’t pass muster in an audit because the information documented is not medically necessary.”

According to LeGrand, the extent of the history and examination should be based on the presenting problem and the patient’s condition. “If an ankle sprain patient returns 2 weeks after the initial evaluation of the injury with a negative medical or surgical history, and the patient has been treated conservatively, it’s probably not necessary to conduct a ROS that includes 10 organ systems,” she says. “If your standard of care is to perform this level of service, no one will fault you for your care delivery; however, if you also choose a level of service based on this system review, without relevance to the presenting problem, and you bill a higher level of service than is supported by the nature of the presenting problem or the plan of care, the documentation probably won’t hold up in an audit where medical necessity is valued into the equation.”

On the other hand, LeGrand adds, if a patient presents to the emergency department after an automobile accident with an open fracture and other injuries, and the surgeon performs a complete ROS, the medical necessity would most likely be supported as the surgeon is preparing the patient for surgery.

Based on LeGrand’s work with practices, this distinction about medical necessity is news to many nonclinical billing staff. “They confuse medical necessity with medical decision-making, an E/M code documentation component, and incorrectly bill for a high-level visit because medical decision-making elements meet the documentation requirements—yet the code is not supported by medical necessity of the presenting problem.”

Talk with your billing team to make sure all staff members understand this critical difference. They must comprehend that the medically necessary level of service is determined by a number of clinical factors, not medical decision-making. Describe some of these clinical factors, which include, but are not limited to, chief complaint, clinical judgment, standards of practice, acute exacerbations/onsets of medical conditions or injuries, and comorbidities.

EHR Dos and Don’ts

LeGrand recommends the following best practices for using EHR documentation features:

1. DON’T simply cut and paste from a previous note. “This is what leads to verbose notes that have little to do with the patient you are documenting,” she says. “If you don’t cut and paste, you’ll avoid the root cause of this risk.”

2. DON’T pull forward information from previous visit notes that have nothing to do with the nature of the patient’s problem. “We understand that this takes extra time because physicians must review the previous note,” LeGrand says. “So if you don’t have time to review the past note, just don’t pull it forward. Start fresh with a new drop-down menu and select elements pertinent to the current visit. Or, dictate or type a note relevant to the current condition and presenting problems.”

How you choose to work this into your process will vary depending on which EHR system you use. “One surgeon I work with dictates everything because the drop-down menus and templates are cumbersome,” LeGrand says. “Some groups find it faster to use the EHR templates that they have customized. Others find their EHR’s point-and-click features most efficient for customizing quickly.”

3. DO customize your EHR visit templates if the use of templates is critical to your efficiency. “This is the most overlooked step in the EHR implementation process because it takes a fair amount of time to do,” LeGrand says. She suggests avoiding the use of multisystem examination templates created for medicine specialties altogether, and insists, “Don’t assume ‘that is how the vendor built it so we have to use it.’ Customize a template for each of your visit types so you can document in the EHR in the same fashion as when you used a paper system. Doing so will save you loads of documentation time.”

4. DO review your E/M code distribution. Generate a CPT frequency report for each physician and for the practice as a whole. Compare the data with state and national usage in orthopedics as a baseline. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon’s Code-X tool enables easy comparison of your practice’s E/M code usage with state and national data for orthopedics. Simply generate a CPT frequency report from your practice management system and enter the E/M data. Line graphs are automatically generated, making trends and patterns easy to see (Figure).

“Identify your outliers, pull charts randomly, and review the notes,” recommends LeGrand. “Make sure there is medical necessity for the level of code that’s been billed and that documentation supports it.”

You may be surprised to find you are an outlier on inpatient hospital codes, or your distribution of level-2 or -3 codes varies from your practice, state, or national data. Orthopedic surgeons don’t typically report high volumes of CPT codes 99204, 99205 or 99215, but if your practice does and you are an outlier, best to pay attention before someone else does.

5. DO select auditors with the right skill sets. Evaluating medical necessity in the note requires a clinical background. “If internal documentation reviews are conducted by the billing team, that’s fine,” LeGrand advises. “Just add a physician assistant or nurse to your internal review team. They can provide clinical oversight and review the note when necessary for medical necessity.”

If you are contracting with external auditors or consultants, verify auditor credentials and skill sets to ensure they can abstract and incorporate medical necessity into the review. “Auditors must be able to do more than count elements,” LeGrand says. “They must have clinical knowledge, and expertise in orthopedics is critical. This knowledge should be used to verify that medical necessity is present in every note.” LeGrand is quick to point out that not every note will be at risk, based on the amount of work performed and documented and the level of service billed. “But medical necessity must always be present.”

The addition of nurses to the OIG’s audit team is a big change and will refine the auditing process by adding more clinical scrutiny. The EHR documentation features are intended to improve efficiency, but only a clinician can determine and document unique visit elements and medical necessity.

Address these intersections of risk by ensuring your documentation meets medical necessity as well as E/M documentation elements. Conduct internal audits bi-annually to verify that E/M usage patterns align with peers and physician documentation is appropriate. And be sure there is clinical expertise on your audit team, whether it is internal or external. CMS now has it, and your practice should too. ◾

A group of 3 busy orthopedists attended coding education each year and did their best to accurately code and document their services. As a risk-reduction strategy, the group engaged our firm to conduct an audit to determine whether they were documenting their services properly and to provide feedback about how they could improve.

What we found was shocking to the surgeons, but all too common, as we review thousands of orthopedic visit notes every year: The same examination had been documented for all visits, with physicians stating in their notes that the examination was medically necessary. In addition, their documentation supported Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99214 at every visit, with visit frequencies of 2 weeks to 4 months.

The culprit of all this sameness? The practice’s electronic health record (EHR).

“Practices with EHRs often have a large volume of visit notes that look almost identical for a patient who is seen for multiple visits,” explains Mary LeGrand, RN, MA, CCS-P, CPC, KarenZupko & Associates consultant and coding educator. “And that is putting physicians at higher risk of being audited or of not passing an audit.”

According to LeGrand, this is because physicians are using the practice’s EHR to “pull forward” the patient’s previous visit note for the current visit, but failing to customize it for the current visit. The unintended consequence of this workflow efficiency is twofold:

1. It creates documentation that looks strikingly similar to, if not exactly like, the patient’s last billed visit note. This is often referred to as note “cloning.”

2. It creates documentation that includes a lot of unnecessary detail that, even if delivered and documented, doesn’t match the medical necessity of the visit, based on the history of present illness statements.

Both of these things can come back to bite you.

Zero in on the Risk

If your practice has an EHR, it is important that you evaluate whether certain workflow efficiency features are putting the practice at risk. You do not necessarily need to dump the EHR, but you may need to take action to reduce the risk of using these features.

In a pre-EHR practice, physicians began each visit with a blank piece of paper or dictated the entire visit. Then along came EHR vendors who, in an effort to make things easier and more efficient, created visit templates and the ability to “pull forward” the last visit note and use it as a basis for the current visit. The intention was always that physicians would modify it based on the current visit. But the reality is that physicians are busy, editing is time-consuming, and the unintended consequence is cloning.