User login

Produce and promises

Most of us are in medicine because we find joy and fulfillment in treating patients. That’s why we signed up for the long educational slog, and why many of us continue to practice medicine long after all the bills have been paid. That is why we all find obstructions between us and our patients so maddening.

I guess Medicare was a great boon for seniors, who found health insurance increasingly more difficult to afford, and for doctors, who now got paid in something other than produce and promises by indigent, elderly patients. The American Medical Association opposed the adoption of Medicare, fearing that it would interfere with the physician-patient relationship. This may sound quaint now, especially at a time when there are calls for Medicare for all. While it is hard to argue against Medicare improving access to health care, the AMA was right about the government’s intrusion into the physician-patient relationship, which has become progressively more intrusive. Medicare has undergone major revisions at least five times; none of these revisions has simplified care. Think about the steadily increasing documentation requirements, audits, inflation-ravaged fee schedules, and MIPS [Merit-Based Incentive Payment System], and MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015], although the current proposed Medicare rule, with a two-level fee schedule and reduced documentation, claims to eliminate 50 hours of charting per year.

The next big blow was ERISA (the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974), which really did not seem relevant to medical practice at the time. However, embedded in this law was indemnification of insurers from patient lawsuits. Well, OK, insurers don’t practice medicine, right? Fast-forward to today, when critical medical decisions, including which test can be ordered and which drug can be administered, are driven by insurers – who can delay or refuse care and who cannot be legally blamed for the death or harm of the patient. That’s right, step therapy and prior authorizations would not be possible without ERISA.

Of course, absolutely the most onerous intrusion on the physician-patient relationship is the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2014, which mandated electronic health records. I believe this is the major cause of current physician burnout, which has created the worst and most intrusive barrier between physicians and patients to date. Talk about good intentions gone awry!

In addition, now private equity has entered into medicine, in part in response to these issues and intrusions. But has this improved the patient-physician relationship, or just made things worse?

A big selling point of these private equity–backed groups is the central handling of administrative issues, such as billing, coding, compliance, human resources, prior authorizations, as well as other back-office functions. Some groups even claim to improve patient care and value, by instituting quality metrics for care (I would love to see these published). These services all must be paid for, and the logical argument is that pooling these services will result in efficiency and cost less overall.

Maybe so, but private equity creates yet another barrier between the patient and the physician while it eliminate others. These businesses are driven by profit; they are private equity after all. They are a more insidious threat to the physician-patient relationship and the future of medicine than are clumsy laws, since private equity commoditizes patients and their care. .

Any barrier between the patient and the physician is bad, and two or three barriers make things logarithmically worse. No wonder physicians have become cynical and disillusioned. It makes you pause and wonder, how much do we currently pay in time and overhead to navigate these barriers? Maybe we should call it all even. Maybe we would come out ahead if we counted in produce, promises, and unobstructed patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of us are in medicine because we find joy and fulfillment in treating patients. That’s why we signed up for the long educational slog, and why many of us continue to practice medicine long after all the bills have been paid. That is why we all find obstructions between us and our patients so maddening.

I guess Medicare was a great boon for seniors, who found health insurance increasingly more difficult to afford, and for doctors, who now got paid in something other than produce and promises by indigent, elderly patients. The American Medical Association opposed the adoption of Medicare, fearing that it would interfere with the physician-patient relationship. This may sound quaint now, especially at a time when there are calls for Medicare for all. While it is hard to argue against Medicare improving access to health care, the AMA was right about the government’s intrusion into the physician-patient relationship, which has become progressively more intrusive. Medicare has undergone major revisions at least five times; none of these revisions has simplified care. Think about the steadily increasing documentation requirements, audits, inflation-ravaged fee schedules, and MIPS [Merit-Based Incentive Payment System], and MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015], although the current proposed Medicare rule, with a two-level fee schedule and reduced documentation, claims to eliminate 50 hours of charting per year.

The next big blow was ERISA (the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974), which really did not seem relevant to medical practice at the time. However, embedded in this law was indemnification of insurers from patient lawsuits. Well, OK, insurers don’t practice medicine, right? Fast-forward to today, when critical medical decisions, including which test can be ordered and which drug can be administered, are driven by insurers – who can delay or refuse care and who cannot be legally blamed for the death or harm of the patient. That’s right, step therapy and prior authorizations would not be possible without ERISA.

Of course, absolutely the most onerous intrusion on the physician-patient relationship is the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2014, which mandated electronic health records. I believe this is the major cause of current physician burnout, which has created the worst and most intrusive barrier between physicians and patients to date. Talk about good intentions gone awry!

In addition, now private equity has entered into medicine, in part in response to these issues and intrusions. But has this improved the patient-physician relationship, or just made things worse?

A big selling point of these private equity–backed groups is the central handling of administrative issues, such as billing, coding, compliance, human resources, prior authorizations, as well as other back-office functions. Some groups even claim to improve patient care and value, by instituting quality metrics for care (I would love to see these published). These services all must be paid for, and the logical argument is that pooling these services will result in efficiency and cost less overall.

Maybe so, but private equity creates yet another barrier between the patient and the physician while it eliminate others. These businesses are driven by profit; they are private equity after all. They are a more insidious threat to the physician-patient relationship and the future of medicine than are clumsy laws, since private equity commoditizes patients and their care. .

Any barrier between the patient and the physician is bad, and two or three barriers make things logarithmically worse. No wonder physicians have become cynical and disillusioned. It makes you pause and wonder, how much do we currently pay in time and overhead to navigate these barriers? Maybe we should call it all even. Maybe we would come out ahead if we counted in produce, promises, and unobstructed patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of us are in medicine because we find joy and fulfillment in treating patients. That’s why we signed up for the long educational slog, and why many of us continue to practice medicine long after all the bills have been paid. That is why we all find obstructions between us and our patients so maddening.

I guess Medicare was a great boon for seniors, who found health insurance increasingly more difficult to afford, and for doctors, who now got paid in something other than produce and promises by indigent, elderly patients. The American Medical Association opposed the adoption of Medicare, fearing that it would interfere with the physician-patient relationship. This may sound quaint now, especially at a time when there are calls for Medicare for all. While it is hard to argue against Medicare improving access to health care, the AMA was right about the government’s intrusion into the physician-patient relationship, which has become progressively more intrusive. Medicare has undergone major revisions at least five times; none of these revisions has simplified care. Think about the steadily increasing documentation requirements, audits, inflation-ravaged fee schedules, and MIPS [Merit-Based Incentive Payment System], and MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015], although the current proposed Medicare rule, with a two-level fee schedule and reduced documentation, claims to eliminate 50 hours of charting per year.

The next big blow was ERISA (the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974), which really did not seem relevant to medical practice at the time. However, embedded in this law was indemnification of insurers from patient lawsuits. Well, OK, insurers don’t practice medicine, right? Fast-forward to today, when critical medical decisions, including which test can be ordered and which drug can be administered, are driven by insurers – who can delay or refuse care and who cannot be legally blamed for the death or harm of the patient. That’s right, step therapy and prior authorizations would not be possible without ERISA.

Of course, absolutely the most onerous intrusion on the physician-patient relationship is the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2014, which mandated electronic health records. I believe this is the major cause of current physician burnout, which has created the worst and most intrusive barrier between physicians and patients to date. Talk about good intentions gone awry!

In addition, now private equity has entered into medicine, in part in response to these issues and intrusions. But has this improved the patient-physician relationship, or just made things worse?

A big selling point of these private equity–backed groups is the central handling of administrative issues, such as billing, coding, compliance, human resources, prior authorizations, as well as other back-office functions. Some groups even claim to improve patient care and value, by instituting quality metrics for care (I would love to see these published). These services all must be paid for, and the logical argument is that pooling these services will result in efficiency and cost less overall.

Maybe so, but private equity creates yet another barrier between the patient and the physician while it eliminate others. These businesses are driven by profit; they are private equity after all. They are a more insidious threat to the physician-patient relationship and the future of medicine than are clumsy laws, since private equity commoditizes patients and their care. .

Any barrier between the patient and the physician is bad, and two or three barriers make things logarithmically worse. No wonder physicians have become cynical and disillusioned. It makes you pause and wonder, how much do we currently pay in time and overhead to navigate these barriers? Maybe we should call it all even. Maybe we would come out ahead if we counted in produce, promises, and unobstructed patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The 2019 Medicare proposed rule might just make your head explode

When sitting through interminable meetings, endless reports, and unfocused discussions, I often feel a building pressure in my head that, if it continues, will surely result in my brain exploding. I used to carry in my pocket an elastic compression bandage, intending to wrap it around my head as a signal to the offending speakers, but never had the heart to use it. Still, that bandage in my pocket was the backup resource that gave me solace, gave me patience.

Yet, my emergency bandage was nowhere to be found while I was reading the 2019 Medicare proposed rule, which unexpectedly triggered the threat of a brain explosion.

I was prepared for the usual proposed rule of about 1,500 pages of dense, bureaucratic “Engfish,” proposing a cut here, a tuck there, an occasional evisceration, and several correctable errors. This time, though, the proposed rule is wide open, disruptive, uninformed, and disappointing to almost all medical practitioners.

For dermatology, it starts out promisingly, by collapsing the evaluation and management (E/M) codes into two levels, instead of five. That should benefit us slightly, because our coding usually falls at about level three. Also, it would simplify record keeping by only requiring level two documentation and not making docs repeatedly reenter data. Well, OK so far.

Keep reading, though, and then the hammer falls: a proposed 50% reduction in reimbursement for any procedure performed on the same day as the E/M code. What?! Implementation of this change would result in an estimated 20% reduction in reimbursement for dermatologists who, as a courtesy to their patients, do procedures on the same day as an evaluation visit. And this proposed change would likely hurt ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and even primary care physicians who do same-day procedures.

There are new extended-care codes that only primary care docs could use, and some other extended care codes for specialists (dermatology is not mentioned) that pay about $5 extra. There is a bone thrown to telemedicine, since telemedicine coverage is supported, including “store and forward,” but not if the patient is seen in person within a week, “or at the soonest available appointment.” Very strange.

The current reimbursement system is a carefully honed, carefully balanced, work of reasonable rational thought by the current procedural terminology committee, the American Medical Association’s RVS Update Committee (RUC) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS officials sit at the table at all these meetings, frequently comment, and the agency has the power of final approval. No one loves the final product, particularly the participants, but there are procedures and rules, an appeals process, and the process allows for a rough form of justice administered by your medical peers. Who better to decide what is fair to pay anyone out of a fixed reimbursement pool?

Unfortunately, there seems to be no institutional memory in this year’s final rule. For example, since it came out, various branches of organized medicine have held urgent meetings at which it was pointed out that a 50% reduction in procedures on the same day as an evaluation and management code is inappropriate, since the overlapping work and practice expense already had been removed for such codes by the relative value update committee. This observation reportedly came as a surprise to the CMS attendees – a most disturbing admission.

There was also discouraging news about the global period survey. Dermatology reported only 3% of the global visits possible.

It turns out that CMS did not look for additional 99024 visits beyond the 10- or 90-day global period in the surveyed states and did not look at practices of fewer than 10 dermatologists, even if they did report. Think about it, how many dermatology groups do you know of 10 or more dermatologists in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, and Rhode Island? How often do you delay suture removal beyond 10 days? How many times do you see a patient back for a triamcinolone injection or reassurance at no charge more than 10 days after procedures? Talk about a flawed process destined to fail!

The loss of global periods will hurt much, much more than the 50% cut in procedures on the same day as an E/M code. The premalignant and benign destruction codes could be cut by 75% – and good luck in charging for suture removal after surgery. We are talking about another 20% reimbursement cut if implemented.

The American Academy of Dermatology and other dermatology societies are actively involved in responding to the CMS regarding the shortcomings of the proposed rule. Be prepared to be called upon to submit your comments to CMS soon. I am hopeful that much of these misguided proposals can be corrected, but it will take a concerted effort of numerous individual dermatologists, including you.

Finally, I advise you to read the final rule for yourself. And, unlike me, do not forget to keep your emergency wrap handy!

Comments will be taken at www.regulations.gov through Sept. 10, 2018.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected] .

When sitting through interminable meetings, endless reports, and unfocused discussions, I often feel a building pressure in my head that, if it continues, will surely result in my brain exploding. I used to carry in my pocket an elastic compression bandage, intending to wrap it around my head as a signal to the offending speakers, but never had the heart to use it. Still, that bandage in my pocket was the backup resource that gave me solace, gave me patience.

Yet, my emergency bandage was nowhere to be found while I was reading the 2019 Medicare proposed rule, which unexpectedly triggered the threat of a brain explosion.

I was prepared for the usual proposed rule of about 1,500 pages of dense, bureaucratic “Engfish,” proposing a cut here, a tuck there, an occasional evisceration, and several correctable errors. This time, though, the proposed rule is wide open, disruptive, uninformed, and disappointing to almost all medical practitioners.

For dermatology, it starts out promisingly, by collapsing the evaluation and management (E/M) codes into two levels, instead of five. That should benefit us slightly, because our coding usually falls at about level three. Also, it would simplify record keeping by only requiring level two documentation and not making docs repeatedly reenter data. Well, OK so far.

Keep reading, though, and then the hammer falls: a proposed 50% reduction in reimbursement for any procedure performed on the same day as the E/M code. What?! Implementation of this change would result in an estimated 20% reduction in reimbursement for dermatologists who, as a courtesy to their patients, do procedures on the same day as an evaluation visit. And this proposed change would likely hurt ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and even primary care physicians who do same-day procedures.

There are new extended-care codes that only primary care docs could use, and some other extended care codes for specialists (dermatology is not mentioned) that pay about $5 extra. There is a bone thrown to telemedicine, since telemedicine coverage is supported, including “store and forward,” but not if the patient is seen in person within a week, “or at the soonest available appointment.” Very strange.

The current reimbursement system is a carefully honed, carefully balanced, work of reasonable rational thought by the current procedural terminology committee, the American Medical Association’s RVS Update Committee (RUC) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS officials sit at the table at all these meetings, frequently comment, and the agency has the power of final approval. No one loves the final product, particularly the participants, but there are procedures and rules, an appeals process, and the process allows for a rough form of justice administered by your medical peers. Who better to decide what is fair to pay anyone out of a fixed reimbursement pool?

Unfortunately, there seems to be no institutional memory in this year’s final rule. For example, since it came out, various branches of organized medicine have held urgent meetings at which it was pointed out that a 50% reduction in procedures on the same day as an evaluation and management code is inappropriate, since the overlapping work and practice expense already had been removed for such codes by the relative value update committee. This observation reportedly came as a surprise to the CMS attendees – a most disturbing admission.

There was also discouraging news about the global period survey. Dermatology reported only 3% of the global visits possible.

It turns out that CMS did not look for additional 99024 visits beyond the 10- or 90-day global period in the surveyed states and did not look at practices of fewer than 10 dermatologists, even if they did report. Think about it, how many dermatology groups do you know of 10 or more dermatologists in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, and Rhode Island? How often do you delay suture removal beyond 10 days? How many times do you see a patient back for a triamcinolone injection or reassurance at no charge more than 10 days after procedures? Talk about a flawed process destined to fail!

The loss of global periods will hurt much, much more than the 50% cut in procedures on the same day as an E/M code. The premalignant and benign destruction codes could be cut by 75% – and good luck in charging for suture removal after surgery. We are talking about another 20% reimbursement cut if implemented.

The American Academy of Dermatology and other dermatology societies are actively involved in responding to the CMS regarding the shortcomings of the proposed rule. Be prepared to be called upon to submit your comments to CMS soon. I am hopeful that much of these misguided proposals can be corrected, but it will take a concerted effort of numerous individual dermatologists, including you.

Finally, I advise you to read the final rule for yourself. And, unlike me, do not forget to keep your emergency wrap handy!

Comments will be taken at www.regulations.gov through Sept. 10, 2018.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected] .

When sitting through interminable meetings, endless reports, and unfocused discussions, I often feel a building pressure in my head that, if it continues, will surely result in my brain exploding. I used to carry in my pocket an elastic compression bandage, intending to wrap it around my head as a signal to the offending speakers, but never had the heart to use it. Still, that bandage in my pocket was the backup resource that gave me solace, gave me patience.

Yet, my emergency bandage was nowhere to be found while I was reading the 2019 Medicare proposed rule, which unexpectedly triggered the threat of a brain explosion.

I was prepared for the usual proposed rule of about 1,500 pages of dense, bureaucratic “Engfish,” proposing a cut here, a tuck there, an occasional evisceration, and several correctable errors. This time, though, the proposed rule is wide open, disruptive, uninformed, and disappointing to almost all medical practitioners.

For dermatology, it starts out promisingly, by collapsing the evaluation and management (E/M) codes into two levels, instead of five. That should benefit us slightly, because our coding usually falls at about level three. Also, it would simplify record keeping by only requiring level two documentation and not making docs repeatedly reenter data. Well, OK so far.

Keep reading, though, and then the hammer falls: a proposed 50% reduction in reimbursement for any procedure performed on the same day as the E/M code. What?! Implementation of this change would result in an estimated 20% reduction in reimbursement for dermatologists who, as a courtesy to their patients, do procedures on the same day as an evaluation visit. And this proposed change would likely hurt ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and even primary care physicians who do same-day procedures.

There are new extended-care codes that only primary care docs could use, and some other extended care codes for specialists (dermatology is not mentioned) that pay about $5 extra. There is a bone thrown to telemedicine, since telemedicine coverage is supported, including “store and forward,” but not if the patient is seen in person within a week, “or at the soonest available appointment.” Very strange.

The current reimbursement system is a carefully honed, carefully balanced, work of reasonable rational thought by the current procedural terminology committee, the American Medical Association’s RVS Update Committee (RUC) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS officials sit at the table at all these meetings, frequently comment, and the agency has the power of final approval. No one loves the final product, particularly the participants, but there are procedures and rules, an appeals process, and the process allows for a rough form of justice administered by your medical peers. Who better to decide what is fair to pay anyone out of a fixed reimbursement pool?

Unfortunately, there seems to be no institutional memory in this year’s final rule. For example, since it came out, various branches of organized medicine have held urgent meetings at which it was pointed out that a 50% reduction in procedures on the same day as an evaluation and management code is inappropriate, since the overlapping work and practice expense already had been removed for such codes by the relative value update committee. This observation reportedly came as a surprise to the CMS attendees – a most disturbing admission.

There was also discouraging news about the global period survey. Dermatology reported only 3% of the global visits possible.

It turns out that CMS did not look for additional 99024 visits beyond the 10- or 90-day global period in the surveyed states and did not look at practices of fewer than 10 dermatologists, even if they did report. Think about it, how many dermatology groups do you know of 10 or more dermatologists in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, and Rhode Island? How often do you delay suture removal beyond 10 days? How many times do you see a patient back for a triamcinolone injection or reassurance at no charge more than 10 days after procedures? Talk about a flawed process destined to fail!

The loss of global periods will hurt much, much more than the 50% cut in procedures on the same day as an E/M code. The premalignant and benign destruction codes could be cut by 75% – and good luck in charging for suture removal after surgery. We are talking about another 20% reimbursement cut if implemented.

The American Academy of Dermatology and other dermatology societies are actively involved in responding to the CMS regarding the shortcomings of the proposed rule. Be prepared to be called upon to submit your comments to CMS soon. I am hopeful that much of these misguided proposals can be corrected, but it will take a concerted effort of numerous individual dermatologists, including you.

Finally, I advise you to read the final rule for yourself. And, unlike me, do not forget to keep your emergency wrap handy!

Comments will be taken at www.regulations.gov through Sept. 10, 2018.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected] .

Unlikely mentors

Mentorship is a hot topic. Mentors are generally perceived as knowledgeable, kind, generous souls who will guide mentees through tough challenges and be your pal. I suggest to you that while such encounters are marvelous, and to be sought out, some of the most important lessons are taught by members of the opposite cast.

The presiding secretary of the Ohio state medical board was a brigadier general, still active reserve, tall with a bristling countenance. I was president of the Ohio Dermatological Association and was accompanied by Mark Bechtel, MD, who was our chair of state legislation. We had been invited to , and that there had not been any deaths related to local anesthesia administered by dermatologists in Ohio (or anywhere else). We expected to tell the medical board there was nothing to worry about, and we could all go home. This was 17 years ago.

It quickly became apparent that there had been an extensive prior dialogue between the medical board and representatives of the American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. They sat at the head table with the secretary of the medical board.

“In our experience, there are really some dangerous procedures going on in the office setting under local anesthesia, and this area desperately needs regulation,” the anesthesiologist’s representative said. The surgeon’s representative chimed in: “From what I’ve heard, office surgery is a ticking time bomb and needs regulation, and as soon as possible.” This prattle went on and on, with the medical board secretary sympathetically nodding his head. I raised my hand and was ignored – and ignored. It became apparent that this was a show trial, and our opinion was not really wanted, just our attendance noted in the minutes. Finally, I stood up and protested, and pointed out that all of this “testimony” was conjecture and personal opinion, and that there was no factual basis for their claims. The president stiffened, stood up, and started barking orders.He told me to “sit down and not speak unless I was called on.” I sat down and shut up. And I was never called on. Mark Bechtel put a calming hand on my arm. Goodness, I had not been treated like that since junior high.

I soon realized that dermatologists were not at all important to the medical board, and that the medical board had no idea about our safety and efficiency and really did not care.

Following the meeting, I was told by Larry Lanier (the American Academy of Dermatology state legislative liaison at the time) that Ohio was to be the test state to restrict local anesthesia and tumescent anesthesia nationwide. He explained that some widely reported liposuction-related deaths in Florida had given the medical board the “justification” to act. He went on to explain that yes, there were no data either way, but we had better hire a lobbyist and hope for the best.

I was stunned by what I now call (in this case, rough) “mentorship” by the medical board secretary. I understood I could meekly go along – or get angry. I chose the latter, and it has greatly changed my career.

Now, this was not a hot, red, foam-at-the-mouth mad, but a slow burn, the kind that sustains, not consumes.

I went home and did a literature review and was disheartened to find absolutely nothing in the literature on the safety record of dermatologists in the office setting or on the safety of office surgery in general under local anesthesia. We had nothing to back us up.

I looked up the liposuction deaths in Florida and discovered the procedures were all done under general anesthesia or deep sedation by surgeons of one type or another. I also discovered that Florida had enacted mandatory reporting, and the reports could be had for copying costs. I ordered all available, 9 months of data.

We dermatologists passed a special assessment and hired a lobbyist who told us we were too late to have any impact on the impending restrictions. We took a resolution opposing the medical board rules – which would have eliminated using any sedation in the office, even haloperidol and tumescent anesthesia – to the state medical society and got it passed despite the medical board secretary (who was a former president of the society) testifying against us. The Florida data showed no deaths or injuries from using local anesthesia in the office by anyone, and I succeeded in getting a letter addressing that data published expeditiously in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2001;285[20]:2582).

The president of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery at that time, Stephen Mandy, MD, came to town and testified against the proposed restrictions along with about 60 physicians, including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and other physicians who perform office-based surgery who we had rallied to join us from across the state. So many colleagues joined us, in fact, that some of us had to sit on the floor during the proceedings.

The proposed restrictions evaporated. I and many others have since devoted our research efforts to solidifying dermatology’s safety and quality record. Dr. Bechtel, professor of dermatology at Ohio State University, Columbus, is now secretary of the state medical board. At the last annual state meeting, I thanked the brigadier general, the former secretary of the medical board, for his unlikely mentorship. He smiled and we got our picture taken together.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Mentorship is a hot topic. Mentors are generally perceived as knowledgeable, kind, generous souls who will guide mentees through tough challenges and be your pal. I suggest to you that while such encounters are marvelous, and to be sought out, some of the most important lessons are taught by members of the opposite cast.

The presiding secretary of the Ohio state medical board was a brigadier general, still active reserve, tall with a bristling countenance. I was president of the Ohio Dermatological Association and was accompanied by Mark Bechtel, MD, who was our chair of state legislation. We had been invited to , and that there had not been any deaths related to local anesthesia administered by dermatologists in Ohio (or anywhere else). We expected to tell the medical board there was nothing to worry about, and we could all go home. This was 17 years ago.

It quickly became apparent that there had been an extensive prior dialogue between the medical board and representatives of the American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. They sat at the head table with the secretary of the medical board.

“In our experience, there are really some dangerous procedures going on in the office setting under local anesthesia, and this area desperately needs regulation,” the anesthesiologist’s representative said. The surgeon’s representative chimed in: “From what I’ve heard, office surgery is a ticking time bomb and needs regulation, and as soon as possible.” This prattle went on and on, with the medical board secretary sympathetically nodding his head. I raised my hand and was ignored – and ignored. It became apparent that this was a show trial, and our opinion was not really wanted, just our attendance noted in the minutes. Finally, I stood up and protested, and pointed out that all of this “testimony” was conjecture and personal opinion, and that there was no factual basis for their claims. The president stiffened, stood up, and started barking orders.He told me to “sit down and not speak unless I was called on.” I sat down and shut up. And I was never called on. Mark Bechtel put a calming hand on my arm. Goodness, I had not been treated like that since junior high.

I soon realized that dermatologists were not at all important to the medical board, and that the medical board had no idea about our safety and efficiency and really did not care.

Following the meeting, I was told by Larry Lanier (the American Academy of Dermatology state legislative liaison at the time) that Ohio was to be the test state to restrict local anesthesia and tumescent anesthesia nationwide. He explained that some widely reported liposuction-related deaths in Florida had given the medical board the “justification” to act. He went on to explain that yes, there were no data either way, but we had better hire a lobbyist and hope for the best.

I was stunned by what I now call (in this case, rough) “mentorship” by the medical board secretary. I understood I could meekly go along – or get angry. I chose the latter, and it has greatly changed my career.

Now, this was not a hot, red, foam-at-the-mouth mad, but a slow burn, the kind that sustains, not consumes.

I went home and did a literature review and was disheartened to find absolutely nothing in the literature on the safety record of dermatologists in the office setting or on the safety of office surgery in general under local anesthesia. We had nothing to back us up.

I looked up the liposuction deaths in Florida and discovered the procedures were all done under general anesthesia or deep sedation by surgeons of one type or another. I also discovered that Florida had enacted mandatory reporting, and the reports could be had for copying costs. I ordered all available, 9 months of data.

We dermatologists passed a special assessment and hired a lobbyist who told us we were too late to have any impact on the impending restrictions. We took a resolution opposing the medical board rules – which would have eliminated using any sedation in the office, even haloperidol and tumescent anesthesia – to the state medical society and got it passed despite the medical board secretary (who was a former president of the society) testifying against us. The Florida data showed no deaths or injuries from using local anesthesia in the office by anyone, and I succeeded in getting a letter addressing that data published expeditiously in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2001;285[20]:2582).

The president of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery at that time, Stephen Mandy, MD, came to town and testified against the proposed restrictions along with about 60 physicians, including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and other physicians who perform office-based surgery who we had rallied to join us from across the state. So many colleagues joined us, in fact, that some of us had to sit on the floor during the proceedings.

The proposed restrictions evaporated. I and many others have since devoted our research efforts to solidifying dermatology’s safety and quality record. Dr. Bechtel, professor of dermatology at Ohio State University, Columbus, is now secretary of the state medical board. At the last annual state meeting, I thanked the brigadier general, the former secretary of the medical board, for his unlikely mentorship. He smiled and we got our picture taken together.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Mentorship is a hot topic. Mentors are generally perceived as knowledgeable, kind, generous souls who will guide mentees through tough challenges and be your pal. I suggest to you that while such encounters are marvelous, and to be sought out, some of the most important lessons are taught by members of the opposite cast.

The presiding secretary of the Ohio state medical board was a brigadier general, still active reserve, tall with a bristling countenance. I was president of the Ohio Dermatological Association and was accompanied by Mark Bechtel, MD, who was our chair of state legislation. We had been invited to , and that there had not been any deaths related to local anesthesia administered by dermatologists in Ohio (or anywhere else). We expected to tell the medical board there was nothing to worry about, and we could all go home. This was 17 years ago.

It quickly became apparent that there had been an extensive prior dialogue between the medical board and representatives of the American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. They sat at the head table with the secretary of the medical board.

“In our experience, there are really some dangerous procedures going on in the office setting under local anesthesia, and this area desperately needs regulation,” the anesthesiologist’s representative said. The surgeon’s representative chimed in: “From what I’ve heard, office surgery is a ticking time bomb and needs regulation, and as soon as possible.” This prattle went on and on, with the medical board secretary sympathetically nodding his head. I raised my hand and was ignored – and ignored. It became apparent that this was a show trial, and our opinion was not really wanted, just our attendance noted in the minutes. Finally, I stood up and protested, and pointed out that all of this “testimony” was conjecture and personal opinion, and that there was no factual basis for their claims. The president stiffened, stood up, and started barking orders.He told me to “sit down and not speak unless I was called on.” I sat down and shut up. And I was never called on. Mark Bechtel put a calming hand on my arm. Goodness, I had not been treated like that since junior high.

I soon realized that dermatologists were not at all important to the medical board, and that the medical board had no idea about our safety and efficiency and really did not care.

Following the meeting, I was told by Larry Lanier (the American Academy of Dermatology state legislative liaison at the time) that Ohio was to be the test state to restrict local anesthesia and tumescent anesthesia nationwide. He explained that some widely reported liposuction-related deaths in Florida had given the medical board the “justification” to act. He went on to explain that yes, there were no data either way, but we had better hire a lobbyist and hope for the best.

I was stunned by what I now call (in this case, rough) “mentorship” by the medical board secretary. I understood I could meekly go along – or get angry. I chose the latter, and it has greatly changed my career.

Now, this was not a hot, red, foam-at-the-mouth mad, but a slow burn, the kind that sustains, not consumes.

I went home and did a literature review and was disheartened to find absolutely nothing in the literature on the safety record of dermatologists in the office setting or on the safety of office surgery in general under local anesthesia. We had nothing to back us up.

I looked up the liposuction deaths in Florida and discovered the procedures were all done under general anesthesia or deep sedation by surgeons of one type or another. I also discovered that Florida had enacted mandatory reporting, and the reports could be had for copying costs. I ordered all available, 9 months of data.

We dermatologists passed a special assessment and hired a lobbyist who told us we were too late to have any impact on the impending restrictions. We took a resolution opposing the medical board rules – which would have eliminated using any sedation in the office, even haloperidol and tumescent anesthesia – to the state medical society and got it passed despite the medical board secretary (who was a former president of the society) testifying against us. The Florida data showed no deaths or injuries from using local anesthesia in the office by anyone, and I succeeded in getting a letter addressing that data published expeditiously in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2001;285[20]:2582).

The president of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery at that time, Stephen Mandy, MD, came to town and testified against the proposed restrictions along with about 60 physicians, including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and other physicians who perform office-based surgery who we had rallied to join us from across the state. So many colleagues joined us, in fact, that some of us had to sit on the floor during the proceedings.

The proposed restrictions evaporated. I and many others have since devoted our research efforts to solidifying dermatology’s safety and quality record. Dr. Bechtel, professor of dermatology at Ohio State University, Columbus, is now secretary of the state medical board. At the last annual state meeting, I thanked the brigadier general, the former secretary of the medical board, for his unlikely mentorship. He smiled and we got our picture taken together.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Why contribute to your political action committee?

I got a phone call recently from a friend north of me. “Gosh, did you hear about the State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy ransacking a dermatologist’s office?” he asked. Yes, I had heard about it, and explained that the office compounding rule in Ohio, the reason behind this surprise search and practice, was the subject of an active struggle going on at the state and federal level (see “Beware the state pharmacy board,” Dermatology News, June 3, 2016). I also told him that the pharmacy board swooped into that location because the office had registered for a license to mix drugs (defined by the board as altering a prescription drug by mixing, diluting, or combining), and agreed to unannounced inspections – and that while the dermatologist was not fined, there was a list of compliance issues to be met, including recording the lot number of all samples, keeping separate paper records of each time he mixed medications, and the promise of a return visit soon.

I went on to explain that representatives – past presidents and board members – of the Ohio Dermatological Association (accompanied by Lisa Albany, director of state policy at the American Academy of Dermatology’s Washington office) had met with the state pharmacy board and explained how ridiculous these regulations were. It was a frustrating meeting.

This was obviously unacceptable, and we went on to meet with state legislators, then federal legislators, and even the Food and Drug Administration. The Ohio Dermatological Association, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, the American College of Mohs Surgery, and the AAD all went to Washington, DC, and to the FDA last fall. The Ohio State Medical Association and the American Medical Association lined up in opposition to the rules. The state pharmacy board withdrew its rules and reopened the comment period. We are still waiting to hear back and have encouraged the pharmacy board to wait for FDA and USP (United States Pharmacopeia) guidance.

So, what has this got to do with SkinPAC, our dermatology political action committee?

When our groups went to Washington to talk to our representatives and senators, we had access to all the movers and shakers who could act on this issue because of the AAD Association’s contacts though SkinPAC.

The point I want to make is that . There are many issues directly affecting dermatology, not only compounding, but loss of global periods (see “Time for dermatologists in nine states to start submitting CPT Code 99024,” Dermatology News, July 18, 2017), MACRA reform, MACRA relief, and legislative relief for medication pricing.

So, I told my northern friend who called to attend the AAD’s legislative conference in Washington (July 15-17), regularly contribute to SkinPAC, and get five of his colleagues to sign up too. This is a solid investment of your time and money. Not participating will make it more likely that you will soon need a pharmacy license (in addition to your medical license), may have to start charging patients to remove their sutures, be forced into larger groups to demonstrate quality, and continue to have to explain why a once-cheap generic drug now costs thousands of dollars. Seems like a good investment to me.

Dr. Coldiron is vice chair of the dermatology political action committee (SkinPAC). He is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

I got a phone call recently from a friend north of me. “Gosh, did you hear about the State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy ransacking a dermatologist’s office?” he asked. Yes, I had heard about it, and explained that the office compounding rule in Ohio, the reason behind this surprise search and practice, was the subject of an active struggle going on at the state and federal level (see “Beware the state pharmacy board,” Dermatology News, June 3, 2016). I also told him that the pharmacy board swooped into that location because the office had registered for a license to mix drugs (defined by the board as altering a prescription drug by mixing, diluting, or combining), and agreed to unannounced inspections – and that while the dermatologist was not fined, there was a list of compliance issues to be met, including recording the lot number of all samples, keeping separate paper records of each time he mixed medications, and the promise of a return visit soon.

I went on to explain that representatives – past presidents and board members – of the Ohio Dermatological Association (accompanied by Lisa Albany, director of state policy at the American Academy of Dermatology’s Washington office) had met with the state pharmacy board and explained how ridiculous these regulations were. It was a frustrating meeting.

This was obviously unacceptable, and we went on to meet with state legislators, then federal legislators, and even the Food and Drug Administration. The Ohio Dermatological Association, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, the American College of Mohs Surgery, and the AAD all went to Washington, DC, and to the FDA last fall. The Ohio State Medical Association and the American Medical Association lined up in opposition to the rules. The state pharmacy board withdrew its rules and reopened the comment period. We are still waiting to hear back and have encouraged the pharmacy board to wait for FDA and USP (United States Pharmacopeia) guidance.

So, what has this got to do with SkinPAC, our dermatology political action committee?

When our groups went to Washington to talk to our representatives and senators, we had access to all the movers and shakers who could act on this issue because of the AAD Association’s contacts though SkinPAC.

The point I want to make is that . There are many issues directly affecting dermatology, not only compounding, but loss of global periods (see “Time for dermatologists in nine states to start submitting CPT Code 99024,” Dermatology News, July 18, 2017), MACRA reform, MACRA relief, and legislative relief for medication pricing.

So, I told my northern friend who called to attend the AAD’s legislative conference in Washington (July 15-17), regularly contribute to SkinPAC, and get five of his colleagues to sign up too. This is a solid investment of your time and money. Not participating will make it more likely that you will soon need a pharmacy license (in addition to your medical license), may have to start charging patients to remove their sutures, be forced into larger groups to demonstrate quality, and continue to have to explain why a once-cheap generic drug now costs thousands of dollars. Seems like a good investment to me.

Dr. Coldiron is vice chair of the dermatology political action committee (SkinPAC). He is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

I got a phone call recently from a friend north of me. “Gosh, did you hear about the State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy ransacking a dermatologist’s office?” he asked. Yes, I had heard about it, and explained that the office compounding rule in Ohio, the reason behind this surprise search and practice, was the subject of an active struggle going on at the state and federal level (see “Beware the state pharmacy board,” Dermatology News, June 3, 2016). I also told him that the pharmacy board swooped into that location because the office had registered for a license to mix drugs (defined by the board as altering a prescription drug by mixing, diluting, or combining), and agreed to unannounced inspections – and that while the dermatologist was not fined, there was a list of compliance issues to be met, including recording the lot number of all samples, keeping separate paper records of each time he mixed medications, and the promise of a return visit soon.

I went on to explain that representatives – past presidents and board members – of the Ohio Dermatological Association (accompanied by Lisa Albany, director of state policy at the American Academy of Dermatology’s Washington office) had met with the state pharmacy board and explained how ridiculous these regulations were. It was a frustrating meeting.

This was obviously unacceptable, and we went on to meet with state legislators, then federal legislators, and even the Food and Drug Administration. The Ohio Dermatological Association, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, the American College of Mohs Surgery, and the AAD all went to Washington, DC, and to the FDA last fall. The Ohio State Medical Association and the American Medical Association lined up in opposition to the rules. The state pharmacy board withdrew its rules and reopened the comment period. We are still waiting to hear back and have encouraged the pharmacy board to wait for FDA and USP (United States Pharmacopeia) guidance.

So, what has this got to do with SkinPAC, our dermatology political action committee?

When our groups went to Washington to talk to our representatives and senators, we had access to all the movers and shakers who could act on this issue because of the AAD Association’s contacts though SkinPAC.

The point I want to make is that . There are many issues directly affecting dermatology, not only compounding, but loss of global periods (see “Time for dermatologists in nine states to start submitting CPT Code 99024,” Dermatology News, July 18, 2017), MACRA reform, MACRA relief, and legislative relief for medication pricing.

So, I told my northern friend who called to attend the AAD’s legislative conference in Washington (July 15-17), regularly contribute to SkinPAC, and get five of his colleagues to sign up too. This is a solid investment of your time and money. Not participating will make it more likely that you will soon need a pharmacy license (in addition to your medical license), may have to start charging patients to remove their sutures, be forced into larger groups to demonstrate quality, and continue to have to explain why a once-cheap generic drug now costs thousands of dollars. Seems like a good investment to me.

Dr. Coldiron is vice chair of the dermatology political action committee (SkinPAC). He is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Melanoma in situ: It’s hard to know what you don’t know

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

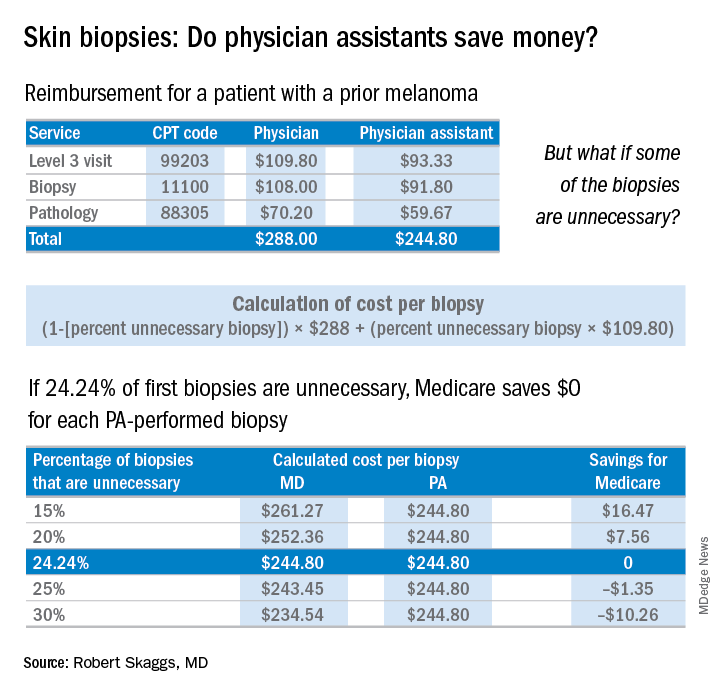

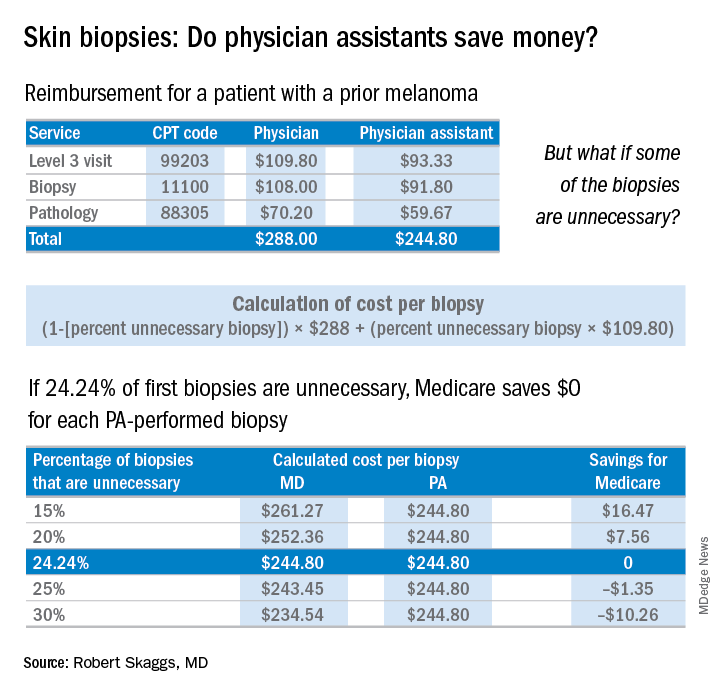

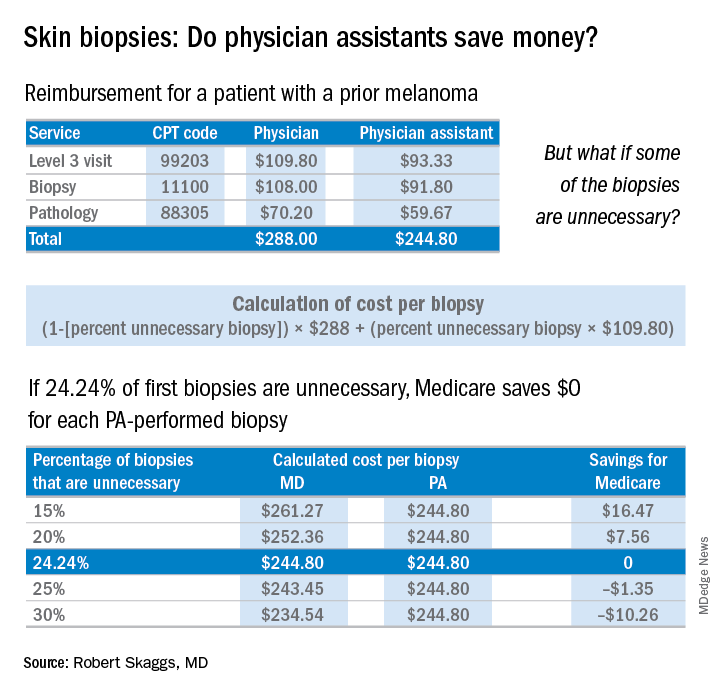

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Tanning is the new tobacco

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.

More than 50 years ago, a national campaign against smoking was launched after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report concluded that smoking was a major health hazard. (Looking back, one of the few losses of not having to pull journal articles from the stacks in the library, is that medical students and residents can’t shake their heads in wonder at the cigarette ads in old medical journals.) The impact of the national antismoking campaign has been dramatic, but smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States and globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in 2006, from 1992 (Arch Dermatol. 2010;146[3]:283-7), dermatologists had good footing on which to start a major prevention campaign. The American Cancer Society got on board, and in 2014, acting surgeon general Boris Lushniak, MD, issued a call to action to prevent skin cancer along with Howard Koh, MD, the assistant secretary of health, in “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer” in 2014, and the campaign was on.

Well, I am delighted to pass on a report from Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who recently described in his March 2018 blog what may the first signs of the effectiveness of efforts to promote protection from ultraviolet ray exposure (JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154[3]:361-2). He writes: “In young white women ages 15 to 24, the incidence of melanoma has declined an average of 5.5% per year from January 2005 through December 2014. Not 5.5% over those ten years but 5.5 % PER YEAR. That’s remarkable, to say the least.”

As for the reasons behind these trends, he says, “no one can say for certain,” but he refers to national data indicating that indoor tanning has decreased in the past few years, especially among adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.