User login

From neuroplasticity to psychoplasticity: Psilocybin may reverse personality disorders and political fanaticism

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

Mifepristone for the treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise

In the uterus, coordinated myometrial cell contraction is not triggered by neural activation; instead, myometrial cells work together as a contractile syncytium through cell-to-cell gap junction connections permitting the intercellular sharing of small molecules, which in turn facilitates activation of the actin-myosin contractile apparatus and coordinated uterine contraction. In myometrial cells, connexin 43 (Cx43) is the main gap junction protein. Cx43 permits the passage of small hydrophilic molecules (ATP) and ions (calcium) cell to cell. Estradiol increases Cx43 synthesis in human myometrial cells.1 Progesterone decreases Cx43 synthesis effectively isolating myometrial cells, reducing cell-to-cell sharing of chemicals that stimulate contraction, blocking coordinated uterine contraction.2 Progesterone suppression of Cx43 synthesis helps to prevent premature uterine contraction during pregnancy. At term, decreases in progesterone levels result in an increase in Cx43 synthesis, facilitating the onset of effective labor. In myometrial cells, antiprogestins, including mifepristone, increase the number of gap junction connections, facilitating a coordinated contractile signal in response to misoprostol or oxytocin.3,4

It takes time for antiprogestins to stimulate myometrial cell production of Cx43. In the rat myometrium the administration of mifepristone results in a 2.5-fold increase of Cx43 mRNA transcripts within 9 hours and a 5.6-fold increase in 24 hours.3 Hence, most mifepristone treatment protocols involve administering mifepristone and waiting 24 to 48 hours before administering an agent that stimulates myometrial contraction, such as misoprostol. Antiprogestins also increase the sensitivity of myometrial cells to oxytocin stimulation of uterine contractions by increasing Cx43 concentration.4

Progesterone also regulates other important biological processes in the cervix, decidua, placenta, and cervix. Antiprogestins can facilitate cervical ripening and disrupt decidual function, interfering with the attachment of pregnancy tissue.5 In the cervix, antiprogestins increase matrix metalloproteinase expression, disrupting collagen organization, decreasing cervical tensile strength and leading to cervical ripening.6

Pharmacology of mifepristone

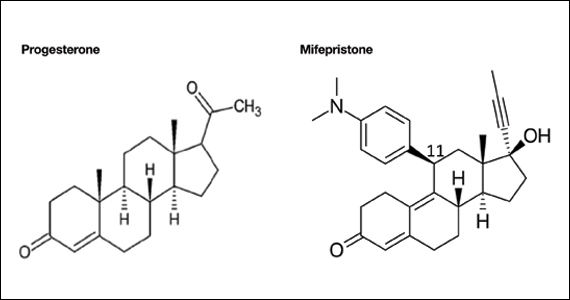

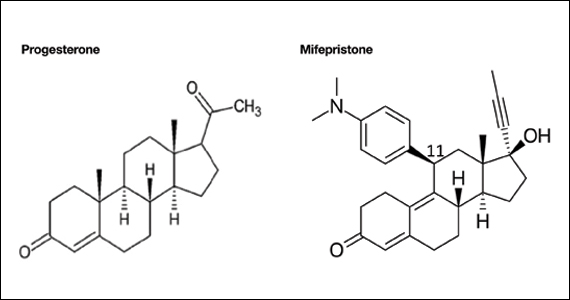

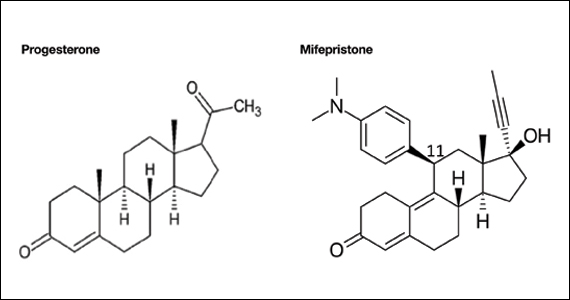

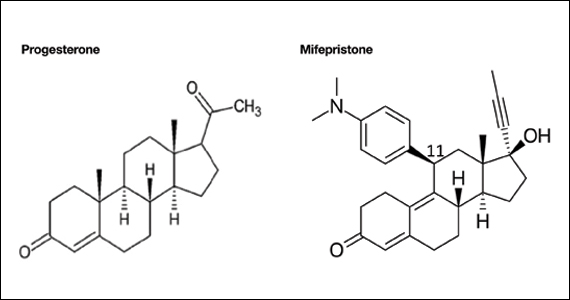

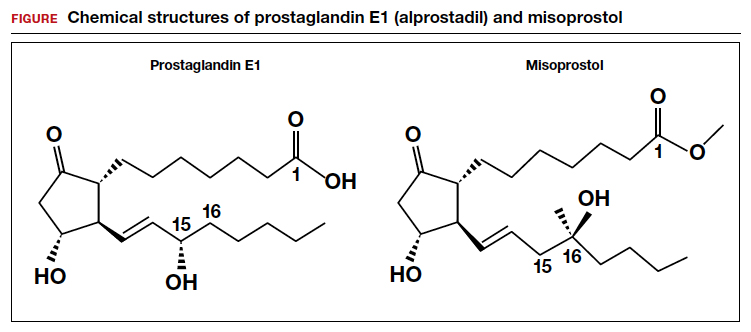

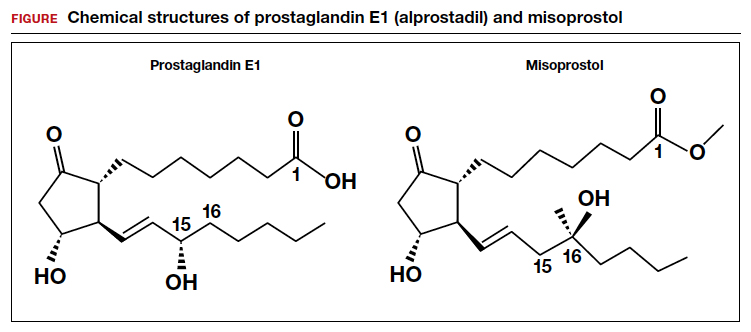

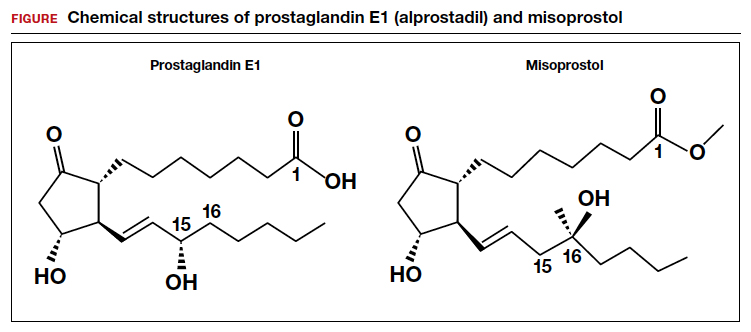

Mifepristone is an antiprogestin and antiglucocorticoid with high-affinity binding to both the progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors (FIGURE 1). The phenylaminodimethyl group at C-11 of mifepristone changes the positional equilibrium of helix 12 of the progesterone receptor, reducing the ability of the receptor to bind required co-activators, limiting receptor binding to DNA, resulting in an antiprogesterone effect.7 At the low, single-dose used for treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise (200 mg one dose), mifepristone is an antiprogestin. At the high, daily dose used for the treatment of hyperglycemia caused by Cushing disease (≥ 300 mg daily), mifepristone is also an antiglucocorticoid.

Although mifepristone is a powerful antiglucocorticoid, in patients with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, mifepristone does not cause adrenal insufficiency. In people with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, daily administration of mifepristone (≥ 200 mg) for 7 days or longer results in an increase in pituitary secretion of ACTH and adrenal secretion of cortisol, largely overcoming the antiglucocorticoid action of mifepristone.8-10 This compensatory increase in ACTH and cortisol is not possible in patients who have had a hypophysectomy or bilateral adrenalectomy or have adrenal suppression due to long-term treatment with high doses of glucocorticoids. Mifepristone is contraindicated for patients with these conditions because it may cause glucocorticoid insufficiency by blocking glucocorticoid receptors.

The terminal half-life of mifepristone is 18 hours.11 Following oral administration of a single dose of mifepristone 200 mg the peak circulating concentration is reached in 90 minutes. Mifepristone is metabolized by CYP3A4 and is also a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4. Contraindications to the use of mifepristone include adrenal failure, porphyria, hemorrhagic diseases, anticoagulation, an IUD in the uterus, ectopic pregnancy, long-term glucocorticoid administration, and an undiagnosed adnexal mass.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac

For patients with a miscarriage, the treatment options to resolve the pregnancy loss are expectant management, medication, or surgery.12 Joint decision-making is recommended to establish a management plan that supports the patient’s values. Expectant management is most likely to result in a multi-week process to achieve completion of the miscarriage. A surgical procedure is most likely to result in rapid resolution of the miscarriage with the greatest rate of success. Surgical evacuation of the uterus may be the preferred option for patients who have excessive uterine bleeding or concerning vital signs. Both medical and surgical management are more likely than expectant management to successfully resolve the miscarriage.13

In the past, the standard approach to medication management of a miscarriage was the administration of one or more doses of misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1. However, two large trials have reported that the dual-medication sequence of mifepristone followed 24 to 48 hours later by misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone for resolving a miscarriage.14,15 This is probably due to mifepristone making the uterus more responsive to the effects of misoprostol.

Schreiber and colleagues14 reported a study of 300 patients with an anembryonic gestation or embryonic demise, between 5 and 12 completed weeks of gestation, who were randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone (200 mg) followed in 24 to 48 hours with vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) or vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) alone. Ultrasonography was performed 1 to 4 days after misoprostol administration. Successful treatment was defined as expulsion of the gestational sac plus no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days after treatment. In this study, the dual-medication regimen of mifepristone-misoprostol was more successful than misoprostol alone in resolving the miscarriage, 84% and 67%, respectively (relative risk [RR], 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–1.43).

Surgical evacuation of the uterus occurred less often with mifepristone-misoprostol treatment than with misoprostol monotherapy—9% and 24%, respectively (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21–0.68). Pelvic infection occurred in 2 patients (1.3%) in each group. Uterine bleeding managed with blood transfusion occurred in 3 patients who received mifepristone-misoprostol and 1 patient who received misoprostol alone. In this study, clinical factors including active bleeding, parity, and gestational age did not influence treatment success with the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen.16 The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen was reported to be more cost-effective than misoprostol alone.17

Chu and colleagues15 reported a study of medication treatment of missed miscarriage that included more than 700 patients randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone-misoprostol or placebo-misoprostol. Missed miscarriage was diagnosed by an ultrasound demonstrating a gestational sac and a nonviable pregnancy. The doses of mifepristone and misoprostol were 200 mg and 800 µg, respectively. In this study the misoprostol was administered 48 hours following mifepristone or placebo using a vaginal, oral, or buccal route, but 90% of patients used the vaginal route. Treatment was considered successful if the patient passed the gestational sac as determined by an ultrasound performed 7 days after entry into the study. If the gestational sac was passed, the patients were asked to do a urine pregnancy test 3 weeks after entering the study to conclude their care episode. If patients did not pass the gestational sac, they were offered a second dose of misoprostol or surgical evacuation. In this study, mifepristone-misoprostol resulted in fewer patients who did not pass the gestational sac within 7 days after entry into the study than placebo (mifepristone-misoprostol, 17% vs placebo-misoprostol, 24% (P=.043). Surgical intervention was performed in 25% of patients treated with placebo-misoprostol and 17% of patients treated with mifepristone-misoprostol (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.53–0.95; P=.021). A cost-effectiveness analysis of the trial results reported that the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol was less costly than misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriages.18

Misoprostol can be administered by an oral, buccal, rectal, or vaginal route.19,20 Vaginal administration results in higher circulating concentrations of misoprostol than buccal administration, but both routes of administration produce similar mean uterine tone and mean uterine activity as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer over 5 hours.21 Hence, at our institution, we most often use buccal administration of misoprostol. To assess effectiveness of mifepristone-misoprostol treatment, 1 week after treatment with a pelvic ultrasound to detect expulsion of the gestational sac. Alternatively, a urine pregnancy test can be performed 3 weeks following medication treatment. The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of miscarriage.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise

Fetal loss in the second or third trimesters is a devastating experience for most patients, painfully echoing in the heart and mind for years. Empathic and effective treatment of fetal loss may reduce the adverse impact of the event. Multiple studies have reported that combinations of mifepristone and misoprostol reduced the time from initiation of labor contractions to birth compared with misoprostol alone.22-28 In addition, the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol reduced the amount of misoprostol needed to achieve delivery.22,23

In one clinical trial, 66 patients with fetal demise between 14 and 28 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.22 Twenty-four to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 14 to 23 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 400 µg vaginally every 6 hours. For patients from 24 to 28 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 200 µg vaginally every 4 hours. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 6.8 hours and 10.5 hours (P=.002).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required fewer doses of misoprostol (2.1 vs 3.4; P=.002) and a lower total dose of misoprostol (768 µg vs 1,182 µg; P=.003). All patients in the mifepristone group delivered within 24 hours. By contrast, 13% of the patients in the placebo group delivered more than 24 hours after the initiation of misoprostol treatment. Five patients were readmitted with retained products of conception needing suction curettage—4 in the placebo group and 1 in the mifepristone group.22

In a second clinical trial, 110 patients with fetal demise after 20 weeks of gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.23 Thirty-six to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 20 to 25 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 100 µg vaginally every 6 hours for a maximum of 4 doses. For patients ≥26 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 50 µg vaginally every 4 hours for a maximum of 6 doses. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 9.8 hours and 16.3 hours. (P=.001).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required a lower total dose of misoprostol (110 µg vs 198 µg, P<.001).

Delivery within 24 hours following initiation of misoprostol occurred in 93% and 73% of the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups, respectively (P<.001). Compared with patients in the mifepristone group, shivering occurred more frequently among the patients in the placebo group (7.5% vs 19.2%; P=.09), likely because they received greater doses of misoprostol.23

Miscarriage and fetal demise frequently cause patients to experience a range of emotions including denial, numbness, grief, anger, guilt, and depression. It may take months or years for people to progress to a tentative acceptance of the loss, refocusing on future aspirations. Empathic care and timely and effective medical intervention to resolve the pregnancy loss optimize outcomes. For medication treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, mifepristone is an important agent because it improves the success rate for resolution of miscarriage without surgery and it shortens the time of labor for inductions for fetal demise. Obstetrician-gynecologists are the specialists leading advances in treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. I encourage you to use mifepristone in your care of appropriate patients with miscarriage and fetal demise. ●

- Andersen J, Grine E, Eng L, et al. Expression of connexin-43 in human myometrium and leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1266-1276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90293-r.

- Ou CW, Orsino A, Lye SJ. Expression of connexin-43 and connexin-26 in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and labor is differentially regulated by mechanical and hormonal signals. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5398-5407. doi: 10.1210 /endo.138.12.5624.

- Petrocelli T, Lye SJ. Regulation of transcripts encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, by estrogen and progesterone. Endocrinology. 1993;133:284-290. doi: 10.1210 /endo.133.1.8391423.

- Chwalisz K, Fahrenholz F, Hackenberg M, et al. The progesterone antagonist onapristone increases the effectiveness of oxytocin to produce delivery without changing the myometrial oxytocin receptor concentration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1760-1770. doi: 10.1016/0002 -9378(91)90030-u.

- Large MJ, DeMayo FJ. The regulation of embryo implantation and endometrial decidualization by progesterone receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:155-165. doi: 10.1016 /j.mce.2011.07.027.

- Clark K, Ji H, Feltovich H, et al. Mifepristone-induced cervical ripening: structural, biomechanical and molecular events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1391-1398. doi: 10.1016 /j.ajog.2005.11.026.

- Raaijmakers HCA, Versteegh JE, Uitdehaag JCM. T he x-ray structure of RU486 bound to the progesterone receptor in a destabilized agonist conformation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19572-19579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007872.

- Yuen KCJ, Moraitis A, Nguyen D. Evaluation of evidence of adrenal insufficiency in trials of normocortisolemic patients treated with mifepristone. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1:237-246. doi: 10.1210 /js.2016-1097.

- Spitz IM, Grunberg SM, Chabbert-Buffet N, et al. Management of patients receiving long-term treatment with mifepristone. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1719-1726. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2005.05.056.

- Bertagna X, Escourolle H, Pinquier JL, et al. Administration of RU 486 for 8 days in normal volunteers: antiglucocorticoid effect with no evidence of peripheral cortisol deprivation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:375-380. doi: 10.1210 /jcem.78.2.8106625.

- Mifeprex [package insert]. New York, NY: Danco Laboratories; March 2016.

- Early pregnancy loss. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 200. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197-e207. doi: /AOG.0000000000002899. 10.1097

- Chu J, Devall AJ, Hardy P, et al. What is the best method for managing early miscarriage? BMJ. 2020;368:l6483. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6438.

- Schreiber C, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170. doi: 10.1056 /NEJMoa1715726.

- Chu JJ, Devall AJ, Beeson LE, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol versus misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriage (MifeMiso): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:770-778. doi: 10.1016 /S0140-6736(20)31788-8.

- Sonalkar S, Koelper N, Creinin MD, et al. Management of early pregnancy loss with mifepristone and misoprostol: clinical predictors of treatment success from a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:551.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j. ajog.2020.04.006. 17.

- Nagendra D, Koelper N, Loza-Avalos SE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of nonviable early pregnancy: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1594.

- Okeke-Ogwulu CB, Williams EV, Chu JJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mifepristone and misoprostol versus misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriage: an economic evaluation based on the MifeMiso trial. BJOG. 2021;128: 1534-1545. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16737.

- Tang OS, Schweer H, Seyberth HW, et al. Pharmacokinetics of different routes of administration of misoprostol. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:332336. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.332.

- Schaff EA, DiCenzo R, Fielding SL. Comparison of misoprostol plasma concentrations following buccal and sublingual administration. Contraception. 2005;71:22-25. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2004.06.014.

- Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, et al. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes: drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:582-590. doi: 10.1097/01 .AOG.0000230398.32794.9d.

- Allanson ER, Copson S, Spilsbury K, et al. Pretreatment with mifepristone compared with misoprostol alone for delivery after fetal death between 14 and 28 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:801-809. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004344.

- Chaudhuri P, Datta S. Mifepristone and misoprostol compared with misoprostol alone for induction of labor in intrauterine fetal death: a randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:1884-1890. doi: 10.1111/jog.12815.

- Fyfe R, Murray H. Comparison of induction of labour regimens for termination of pregnancy with and without mifepristone, from 20 to 41 weeks gestation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57:604-608. doi: 10.1111 /ajo.12648.

- Panda S, Jha V, Singh S. Role of combination of mifepristone and misoprostol verses misoprostol alone in induction of labour in late intrauterine fetal death: a prospective study. J Family Reprod Health. 2013;7:177-179.

- Vayrynen W, Heikinheimo O, Nuutila M. Misoprostol-only versus mifepristone plus misoprostol in induction of labor following intrauterine fetal death. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86: 701-705. doi: 10.1080/00016340701379853.

- Sharma D, Singhal SR, Poonam AP. Comparison of mifepristone combination with misoprostol and misoprostol alone in the management of intrauterine death. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;50:322-325. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2011.07.007.

- Stibbe KJM, de Weerd S. Induction of delivery by mifepristone and misoprostol in termination of pregnancy and intrauterine fetal death: 2nd and 3rd trimester induction of labour. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:795-796. doi: 10.1007 /s00404-012-2289-3.

In the uterus, coordinated myometrial cell contraction is not triggered by neural activation; instead, myometrial cells work together as a contractile syncytium through cell-to-cell gap junction connections permitting the intercellular sharing of small molecules, which in turn facilitates activation of the actin-myosin contractile apparatus and coordinated uterine contraction. In myometrial cells, connexin 43 (Cx43) is the main gap junction protein. Cx43 permits the passage of small hydrophilic molecules (ATP) and ions (calcium) cell to cell. Estradiol increases Cx43 synthesis in human myometrial cells.1 Progesterone decreases Cx43 synthesis effectively isolating myometrial cells, reducing cell-to-cell sharing of chemicals that stimulate contraction, blocking coordinated uterine contraction.2 Progesterone suppression of Cx43 synthesis helps to prevent premature uterine contraction during pregnancy. At term, decreases in progesterone levels result in an increase in Cx43 synthesis, facilitating the onset of effective labor. In myometrial cells, antiprogestins, including mifepristone, increase the number of gap junction connections, facilitating a coordinated contractile signal in response to misoprostol or oxytocin.3,4

It takes time for antiprogestins to stimulate myometrial cell production of Cx43. In the rat myometrium the administration of mifepristone results in a 2.5-fold increase of Cx43 mRNA transcripts within 9 hours and a 5.6-fold increase in 24 hours.3 Hence, most mifepristone treatment protocols involve administering mifepristone and waiting 24 to 48 hours before administering an agent that stimulates myometrial contraction, such as misoprostol. Antiprogestins also increase the sensitivity of myometrial cells to oxytocin stimulation of uterine contractions by increasing Cx43 concentration.4

Progesterone also regulates other important biological processes in the cervix, decidua, placenta, and cervix. Antiprogestins can facilitate cervical ripening and disrupt decidual function, interfering with the attachment of pregnancy tissue.5 In the cervix, antiprogestins increase matrix metalloproteinase expression, disrupting collagen organization, decreasing cervical tensile strength and leading to cervical ripening.6

Pharmacology of mifepristone

Mifepristone is an antiprogestin and antiglucocorticoid with high-affinity binding to both the progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors (FIGURE 1). The phenylaminodimethyl group at C-11 of mifepristone changes the positional equilibrium of helix 12 of the progesterone receptor, reducing the ability of the receptor to bind required co-activators, limiting receptor binding to DNA, resulting in an antiprogesterone effect.7 At the low, single-dose used for treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise (200 mg one dose), mifepristone is an antiprogestin. At the high, daily dose used for the treatment of hyperglycemia caused by Cushing disease (≥ 300 mg daily), mifepristone is also an antiglucocorticoid.

Although mifepristone is a powerful antiglucocorticoid, in patients with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, mifepristone does not cause adrenal insufficiency. In people with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, daily administration of mifepristone (≥ 200 mg) for 7 days or longer results in an increase in pituitary secretion of ACTH and adrenal secretion of cortisol, largely overcoming the antiglucocorticoid action of mifepristone.8-10 This compensatory increase in ACTH and cortisol is not possible in patients who have had a hypophysectomy or bilateral adrenalectomy or have adrenal suppression due to long-term treatment with high doses of glucocorticoids. Mifepristone is contraindicated for patients with these conditions because it may cause glucocorticoid insufficiency by blocking glucocorticoid receptors.

The terminal half-life of mifepristone is 18 hours.11 Following oral administration of a single dose of mifepristone 200 mg the peak circulating concentration is reached in 90 minutes. Mifepristone is metabolized by CYP3A4 and is also a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4. Contraindications to the use of mifepristone include adrenal failure, porphyria, hemorrhagic diseases, anticoagulation, an IUD in the uterus, ectopic pregnancy, long-term glucocorticoid administration, and an undiagnosed adnexal mass.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac

For patients with a miscarriage, the treatment options to resolve the pregnancy loss are expectant management, medication, or surgery.12 Joint decision-making is recommended to establish a management plan that supports the patient’s values. Expectant management is most likely to result in a multi-week process to achieve completion of the miscarriage. A surgical procedure is most likely to result in rapid resolution of the miscarriage with the greatest rate of success. Surgical evacuation of the uterus may be the preferred option for patients who have excessive uterine bleeding or concerning vital signs. Both medical and surgical management are more likely than expectant management to successfully resolve the miscarriage.13

In the past, the standard approach to medication management of a miscarriage was the administration of one or more doses of misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1. However, two large trials have reported that the dual-medication sequence of mifepristone followed 24 to 48 hours later by misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone for resolving a miscarriage.14,15 This is probably due to mifepristone making the uterus more responsive to the effects of misoprostol.

Schreiber and colleagues14 reported a study of 300 patients with an anembryonic gestation or embryonic demise, between 5 and 12 completed weeks of gestation, who were randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone (200 mg) followed in 24 to 48 hours with vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) or vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) alone. Ultrasonography was performed 1 to 4 days after misoprostol administration. Successful treatment was defined as expulsion of the gestational sac plus no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days after treatment. In this study, the dual-medication regimen of mifepristone-misoprostol was more successful than misoprostol alone in resolving the miscarriage, 84% and 67%, respectively (relative risk [RR], 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–1.43).

Surgical evacuation of the uterus occurred less often with mifepristone-misoprostol treatment than with misoprostol monotherapy—9% and 24%, respectively (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21–0.68). Pelvic infection occurred in 2 patients (1.3%) in each group. Uterine bleeding managed with blood transfusion occurred in 3 patients who received mifepristone-misoprostol and 1 patient who received misoprostol alone. In this study, clinical factors including active bleeding, parity, and gestational age did not influence treatment success with the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen.16 The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen was reported to be more cost-effective than misoprostol alone.17

Chu and colleagues15 reported a study of medication treatment of missed miscarriage that included more than 700 patients randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone-misoprostol or placebo-misoprostol. Missed miscarriage was diagnosed by an ultrasound demonstrating a gestational sac and a nonviable pregnancy. The doses of mifepristone and misoprostol were 200 mg and 800 µg, respectively. In this study the misoprostol was administered 48 hours following mifepristone or placebo using a vaginal, oral, or buccal route, but 90% of patients used the vaginal route. Treatment was considered successful if the patient passed the gestational sac as determined by an ultrasound performed 7 days after entry into the study. If the gestational sac was passed, the patients were asked to do a urine pregnancy test 3 weeks after entering the study to conclude their care episode. If patients did not pass the gestational sac, they were offered a second dose of misoprostol or surgical evacuation. In this study, mifepristone-misoprostol resulted in fewer patients who did not pass the gestational sac within 7 days after entry into the study than placebo (mifepristone-misoprostol, 17% vs placebo-misoprostol, 24% (P=.043). Surgical intervention was performed in 25% of patients treated with placebo-misoprostol and 17% of patients treated with mifepristone-misoprostol (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.53–0.95; P=.021). A cost-effectiveness analysis of the trial results reported that the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol was less costly than misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriages.18

Misoprostol can be administered by an oral, buccal, rectal, or vaginal route.19,20 Vaginal administration results in higher circulating concentrations of misoprostol than buccal administration, but both routes of administration produce similar mean uterine tone and mean uterine activity as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer over 5 hours.21 Hence, at our institution, we most often use buccal administration of misoprostol. To assess effectiveness of mifepristone-misoprostol treatment, 1 week after treatment with a pelvic ultrasound to detect expulsion of the gestational sac. Alternatively, a urine pregnancy test can be performed 3 weeks following medication treatment. The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of miscarriage.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise

Fetal loss in the second or third trimesters is a devastating experience for most patients, painfully echoing in the heart and mind for years. Empathic and effective treatment of fetal loss may reduce the adverse impact of the event. Multiple studies have reported that combinations of mifepristone and misoprostol reduced the time from initiation of labor contractions to birth compared with misoprostol alone.22-28 In addition, the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol reduced the amount of misoprostol needed to achieve delivery.22,23

In one clinical trial, 66 patients with fetal demise between 14 and 28 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.22 Twenty-four to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 14 to 23 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 400 µg vaginally every 6 hours. For patients from 24 to 28 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 200 µg vaginally every 4 hours. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 6.8 hours and 10.5 hours (P=.002).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required fewer doses of misoprostol (2.1 vs 3.4; P=.002) and a lower total dose of misoprostol (768 µg vs 1,182 µg; P=.003). All patients in the mifepristone group delivered within 24 hours. By contrast, 13% of the patients in the placebo group delivered more than 24 hours after the initiation of misoprostol treatment. Five patients were readmitted with retained products of conception needing suction curettage—4 in the placebo group and 1 in the mifepristone group.22

In a second clinical trial, 110 patients with fetal demise after 20 weeks of gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.23 Thirty-six to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 20 to 25 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 100 µg vaginally every 6 hours for a maximum of 4 doses. For patients ≥26 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 50 µg vaginally every 4 hours for a maximum of 6 doses. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 9.8 hours and 16.3 hours. (P=.001).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required a lower total dose of misoprostol (110 µg vs 198 µg, P<.001).

Delivery within 24 hours following initiation of misoprostol occurred in 93% and 73% of the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups, respectively (P<.001). Compared with patients in the mifepristone group, shivering occurred more frequently among the patients in the placebo group (7.5% vs 19.2%; P=.09), likely because they received greater doses of misoprostol.23

Miscarriage and fetal demise frequently cause patients to experience a range of emotions including denial, numbness, grief, anger, guilt, and depression. It may take months or years for people to progress to a tentative acceptance of the loss, refocusing on future aspirations. Empathic care and timely and effective medical intervention to resolve the pregnancy loss optimize outcomes. For medication treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, mifepristone is an important agent because it improves the success rate for resolution of miscarriage without surgery and it shortens the time of labor for inductions for fetal demise. Obstetrician-gynecologists are the specialists leading advances in treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. I encourage you to use mifepristone in your care of appropriate patients with miscarriage and fetal demise. ●

In the uterus, coordinated myometrial cell contraction is not triggered by neural activation; instead, myometrial cells work together as a contractile syncytium through cell-to-cell gap junction connections permitting the intercellular sharing of small molecules, which in turn facilitates activation of the actin-myosin contractile apparatus and coordinated uterine contraction. In myometrial cells, connexin 43 (Cx43) is the main gap junction protein. Cx43 permits the passage of small hydrophilic molecules (ATP) and ions (calcium) cell to cell. Estradiol increases Cx43 synthesis in human myometrial cells.1 Progesterone decreases Cx43 synthesis effectively isolating myometrial cells, reducing cell-to-cell sharing of chemicals that stimulate contraction, blocking coordinated uterine contraction.2 Progesterone suppression of Cx43 synthesis helps to prevent premature uterine contraction during pregnancy. At term, decreases in progesterone levels result in an increase in Cx43 synthesis, facilitating the onset of effective labor. In myometrial cells, antiprogestins, including mifepristone, increase the number of gap junction connections, facilitating a coordinated contractile signal in response to misoprostol or oxytocin.3,4

It takes time for antiprogestins to stimulate myometrial cell production of Cx43. In the rat myometrium the administration of mifepristone results in a 2.5-fold increase of Cx43 mRNA transcripts within 9 hours and a 5.6-fold increase in 24 hours.3 Hence, most mifepristone treatment protocols involve administering mifepristone and waiting 24 to 48 hours before administering an agent that stimulates myometrial contraction, such as misoprostol. Antiprogestins also increase the sensitivity of myometrial cells to oxytocin stimulation of uterine contractions by increasing Cx43 concentration.4

Progesterone also regulates other important biological processes in the cervix, decidua, placenta, and cervix. Antiprogestins can facilitate cervical ripening and disrupt decidual function, interfering with the attachment of pregnancy tissue.5 In the cervix, antiprogestins increase matrix metalloproteinase expression, disrupting collagen organization, decreasing cervical tensile strength and leading to cervical ripening.6

Pharmacology of mifepristone

Mifepristone is an antiprogestin and antiglucocorticoid with high-affinity binding to both the progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors (FIGURE 1). The phenylaminodimethyl group at C-11 of mifepristone changes the positional equilibrium of helix 12 of the progesterone receptor, reducing the ability of the receptor to bind required co-activators, limiting receptor binding to DNA, resulting in an antiprogesterone effect.7 At the low, single-dose used for treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise (200 mg one dose), mifepristone is an antiprogestin. At the high, daily dose used for the treatment of hyperglycemia caused by Cushing disease (≥ 300 mg daily), mifepristone is also an antiglucocorticoid.

Although mifepristone is a powerful antiglucocorticoid, in patients with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, mifepristone does not cause adrenal insufficiency. In people with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, daily administration of mifepristone (≥ 200 mg) for 7 days or longer results in an increase in pituitary secretion of ACTH and adrenal secretion of cortisol, largely overcoming the antiglucocorticoid action of mifepristone.8-10 This compensatory increase in ACTH and cortisol is not possible in patients who have had a hypophysectomy or bilateral adrenalectomy or have adrenal suppression due to long-term treatment with high doses of glucocorticoids. Mifepristone is contraindicated for patients with these conditions because it may cause glucocorticoid insufficiency by blocking glucocorticoid receptors.

The terminal half-life of mifepristone is 18 hours.11 Following oral administration of a single dose of mifepristone 200 mg the peak circulating concentration is reached in 90 minutes. Mifepristone is metabolized by CYP3A4 and is also a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4. Contraindications to the use of mifepristone include adrenal failure, porphyria, hemorrhagic diseases, anticoagulation, an IUD in the uterus, ectopic pregnancy, long-term glucocorticoid administration, and an undiagnosed adnexal mass.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of early missed miscarriage with a gestational sac

For patients with a miscarriage, the treatment options to resolve the pregnancy loss are expectant management, medication, or surgery.12 Joint decision-making is recommended to establish a management plan that supports the patient’s values. Expectant management is most likely to result in a multi-week process to achieve completion of the miscarriage. A surgical procedure is most likely to result in rapid resolution of the miscarriage with the greatest rate of success. Surgical evacuation of the uterus may be the preferred option for patients who have excessive uterine bleeding or concerning vital signs. Both medical and surgical management are more likely than expectant management to successfully resolve the miscarriage.13

In the past, the standard approach to medication management of a miscarriage was the administration of one or more doses of misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1. However, two large trials have reported that the dual-medication sequence of mifepristone followed 24 to 48 hours later by misoprostol is more effective than misoprostol alone for resolving a miscarriage.14,15 This is probably due to mifepristone making the uterus more responsive to the effects of misoprostol.

Schreiber and colleagues14 reported a study of 300 patients with an anembryonic gestation or embryonic demise, between 5 and 12 completed weeks of gestation, who were randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone (200 mg) followed in 24 to 48 hours with vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) or vaginal misoprostol (800 µg) alone. Ultrasonography was performed 1 to 4 days after misoprostol administration. Successful treatment was defined as expulsion of the gestational sac plus no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days after treatment. In this study, the dual-medication regimen of mifepristone-misoprostol was more successful than misoprostol alone in resolving the miscarriage, 84% and 67%, respectively (relative risk [RR], 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–1.43).

Surgical evacuation of the uterus occurred less often with mifepristone-misoprostol treatment than with misoprostol monotherapy—9% and 24%, respectively (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21–0.68). Pelvic infection occurred in 2 patients (1.3%) in each group. Uterine bleeding managed with blood transfusion occurred in 3 patients who received mifepristone-misoprostol and 1 patient who received misoprostol alone. In this study, clinical factors including active bleeding, parity, and gestational age did not influence treatment success with the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen.16 The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen was reported to be more cost-effective than misoprostol alone.17

Chu and colleagues15 reported a study of medication treatment of missed miscarriage that included more than 700 patients randomly assigned to treatment with mifepristone-misoprostol or placebo-misoprostol. Missed miscarriage was diagnosed by an ultrasound demonstrating a gestational sac and a nonviable pregnancy. The doses of mifepristone and misoprostol were 200 mg and 800 µg, respectively. In this study the misoprostol was administered 48 hours following mifepristone or placebo using a vaginal, oral, or buccal route, but 90% of patients used the vaginal route. Treatment was considered successful if the patient passed the gestational sac as determined by an ultrasound performed 7 days after entry into the study. If the gestational sac was passed, the patients were asked to do a urine pregnancy test 3 weeks after entering the study to conclude their care episode. If patients did not pass the gestational sac, they were offered a second dose of misoprostol or surgical evacuation. In this study, mifepristone-misoprostol resulted in fewer patients who did not pass the gestational sac within 7 days after entry into the study than placebo (mifepristone-misoprostol, 17% vs placebo-misoprostol, 24% (P=.043). Surgical intervention was performed in 25% of patients treated with placebo-misoprostol and 17% of patients treated with mifepristone-misoprostol (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.53–0.95; P=.021). A cost-effectiveness analysis of the trial results reported that the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol was less costly than misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriages.18

Misoprostol can be administered by an oral, buccal, rectal, or vaginal route.19,20 Vaginal administration results in higher circulating concentrations of misoprostol than buccal administration, but both routes of administration produce similar mean uterine tone and mean uterine activity as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer over 5 hours.21 Hence, at our institution, we most often use buccal administration of misoprostol. To assess effectiveness of mifepristone-misoprostol treatment, 1 week after treatment with a pelvic ultrasound to detect expulsion of the gestational sac. Alternatively, a urine pregnancy test can be performed 3 weeks following medication treatment. The mifepristone-misoprostol regimen is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of miscarriage.

Continue to: Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise...

Mifepristone-misoprostol for the treatment of fetal demise

Fetal loss in the second or third trimesters is a devastating experience for most patients, painfully echoing in the heart and mind for years. Empathic and effective treatment of fetal loss may reduce the adverse impact of the event. Multiple studies have reported that combinations of mifepristone and misoprostol reduced the time from initiation of labor contractions to birth compared with misoprostol alone.22-28 In addition, the combination of mifepristone-misoprostol reduced the amount of misoprostol needed to achieve delivery.22,23

In one clinical trial, 66 patients with fetal demise between 14 and 28 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.22 Twenty-four to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 14 to 23 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 400 µg vaginally every 6 hours. For patients from 24 to 28 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 200 µg vaginally every 4 hours. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 6.8 hours and 10.5 hours (P=.002).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required fewer doses of misoprostol (2.1 vs 3.4; P=.002) and a lower total dose of misoprostol (768 µg vs 1,182 µg; P=.003). All patients in the mifepristone group delivered within 24 hours. By contrast, 13% of the patients in the placebo group delivered more than 24 hours after the initiation of misoprostol treatment. Five patients were readmitted with retained products of conception needing suction curettage—4 in the placebo group and 1 in the mifepristone group.22

In a second clinical trial, 110 patients with fetal demise after 20 weeks of gestation were randomized to receive mifepristone 200 mg or placebo.23 Thirty-six to 48 hours later, misoprostol for induction of labor was initiated. Among the patients from 20 to 25 completed weeks of gestation, the misoprostol dose was 100 µg vaginally every 6 hours for a maximum of 4 doses. For patients ≥26 weeks gestation, the misoprostol dose was 50 µg vaginally every 4 hours for a maximum of 6 doses. The median times from initiation of misoprostol to birth for the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups were 9.8 hours and 16.3 hours. (P=.001).

Compared with the patients in the placebo-misoprostol group, the patients in the mifepristone-misoprostol group required a lower total dose of misoprostol (110 µg vs 198 µg, P<.001).

Delivery within 24 hours following initiation of misoprostol occurred in 93% and 73% of the patients in the mifepristone and placebo groups, respectively (P<.001). Compared with patients in the mifepristone group, shivering occurred more frequently among the patients in the placebo group (7.5% vs 19.2%; P=.09), likely because they received greater doses of misoprostol.23

Miscarriage and fetal demise frequently cause patients to experience a range of emotions including denial, numbness, grief, anger, guilt, and depression. It may take months or years for people to progress to a tentative acceptance of the loss, refocusing on future aspirations. Empathic care and timely and effective medical intervention to resolve the pregnancy loss optimize outcomes. For medication treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, mifepristone is an important agent because it improves the success rate for resolution of miscarriage without surgery and it shortens the time of labor for inductions for fetal demise. Obstetrician-gynecologists are the specialists leading advances in treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. I encourage you to use mifepristone in your care of appropriate patients with miscarriage and fetal demise. ●

- Andersen J, Grine E, Eng L, et al. Expression of connexin-43 in human myometrium and leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1266-1276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90293-r.

- Ou CW, Orsino A, Lye SJ. Expression of connexin-43 and connexin-26 in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and labor is differentially regulated by mechanical and hormonal signals. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5398-5407. doi: 10.1210 /endo.138.12.5624.

- Petrocelli T, Lye SJ. Regulation of transcripts encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, by estrogen and progesterone. Endocrinology. 1993;133:284-290. doi: 10.1210 /endo.133.1.8391423.

- Chwalisz K, Fahrenholz F, Hackenberg M, et al. The progesterone antagonist onapristone increases the effectiveness of oxytocin to produce delivery without changing the myometrial oxytocin receptor concentration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1760-1770. doi: 10.1016/0002 -9378(91)90030-u.

- Large MJ, DeMayo FJ. The regulation of embryo implantation and endometrial decidualization by progesterone receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:155-165. doi: 10.1016 /j.mce.2011.07.027.

- Clark K, Ji H, Feltovich H, et al. Mifepristone-induced cervical ripening: structural, biomechanical and molecular events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1391-1398. doi: 10.1016 /j.ajog.2005.11.026.

- Raaijmakers HCA, Versteegh JE, Uitdehaag JCM. T he x-ray structure of RU486 bound to the progesterone receptor in a destabilized agonist conformation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19572-19579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007872.

- Yuen KCJ, Moraitis A, Nguyen D. Evaluation of evidence of adrenal insufficiency in trials of normocortisolemic patients treated with mifepristone. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1:237-246. doi: 10.1210 /js.2016-1097.

- Spitz IM, Grunberg SM, Chabbert-Buffet N, et al. Management of patients receiving long-term treatment with mifepristone. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1719-1726. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2005.05.056.

- Bertagna X, Escourolle H, Pinquier JL, et al. Administration of RU 486 for 8 days in normal volunteers: antiglucocorticoid effect with no evidence of peripheral cortisol deprivation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:375-380. doi: 10.1210 /jcem.78.2.8106625.

- Mifeprex [package insert]. New York, NY: Danco Laboratories; March 2016.

- Early pregnancy loss. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 200. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197-e207. doi: /AOG.0000000000002899. 10.1097

- Chu J, Devall AJ, Hardy P, et al. What is the best method for managing early miscarriage? BMJ. 2020;368:l6483. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6438.

- Schreiber C, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170. doi: 10.1056 /NEJMoa1715726.

- Chu JJ, Devall AJ, Beeson LE, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol versus misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriage (MifeMiso): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:770-778. doi: 10.1016 /S0140-6736(20)31788-8.