User login

The Role of the Medical Consultant in 2018: Putting It All Together

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Cannabis for chronic pain: Not a simple solution

The narrative review by Modesto-Lowe et al1 in this issue on the potential therapeutic use of cannabis for peripheral neuropathy is only the latest in a vogue string of examinations on how medical marijuana may be used to manage complex conditions. While the authors should be lauded for acknowledging that the role of cannabis in treating peripheral neuropathy is far from settled (“the unknown” in their title), the high stakes involved warrant even more stringent scrutiny than they suggest.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of chronic opioid use with massive repercussions, and it did not start overnight. Mounting calls for liberalizing narcotic use across a broad range of pain conditions accumulated gradually during the patient-advocacy era of the 1990s, with supporting “evidence” coming mostly from small uncontrolled studies, anecdotal reports, and industry pressure.2 Although cannabis and opioids are not interchangeable, we should be cautious about concluding that cannabis is effective and that it should be used to treat chronic pain.

CHRONIC PAIN IS COMPLICATED

Peripheral neuropathy, by definition, is a chronic pain condition. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is characterized by biologic, psychologic, and social complexities that require nuance to manage and study.

Such nuance is lacking in most recent reviews of the medical use of cannabis. The conditions in question are often studied as if they were transient and acute, eg, employing short-term studies and rudimentary measures such as numeric pain-rating scales or other snapshots of pain intensity. Results of these shortsighted assessments are impossible to extrapolate to long-term outcomes.

Whether cannabis therapy for chronic pain conditions is sustainable remains to be seen. Outcomes in chronic pain should not be defined simply by pain reduction, but by other dimensions such as changes in pain-related disability and quality of life, development of pharmacologic tolerance or dependence, adverse effects, and other “collateral damage.” We are far from understanding these issues, which require highly controlled and regulated longitudinal studies.

A recent Cochrane review3 of the efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain found that harms might outweigh the benefits. The quality of evidence was rated as very low to moderate; the reviewers cited small sample sizes and exclusion of important subgroups of patients (eg, those with substance abuse or other psychiatric comorbidities). Such exclusions are the crux of a major problem with cannabis research: studies are not naturalistic. The gritty reality of chronic pain management is paramount, and failing to consider the high-risk biopsychosocial factors typical of patients with chronic pain is naïve and, frankly, dangerous.

COGNITIVE AND MOTIVATIONAL PROBLEMS

The true danger of cannabis lies in what we already know with certainty. As the authors discuss, cannabis undisputedly results in dose-dependent cognitive and motivational problems. If we are preaching physical therapy and home exercise to counter deconditioning, socialization to reverse depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy to increase coping, returning to work to prevent prolonged disability, and other active measures to prevent pain from becoming chronic, then why would we suggest treatments known to blunt motivation, energy, concentration, and overall mood? As a general central nervous system suppressant,4 cannabis works broadly against our best efforts to rehabilitate patients and restore their overall function.

ALL CANNABIS IS NOT THE SAME

The authors use the general term cannabis in their title, yet rightly unpack the differences between medical marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD). However, in the minds of untrained and pain-stricken patients seeking rapid relief and practical solutions, such distinctions are likely irrelevant.

The danger in the barrage of publications examining cannabis vs medical marijuana vs THC vs CBD is that they all communicate an unintentional yet problematic message: that marijuana of some sort for pain is acceptable to try. And in the face of financial pressures, changing legal landscapes, insurance coverage volatility, and access issues, are patients really going to always secure prescriptions for well-regulated CBD (lacking psychoactive THC) from thoughtful and well-informed physicians, or will they turn to convenient street suppliers?

Simplified perceptions of safety and efficacy across all cannabis products do not help. More troublesome would be to extrapolate safety to other forms of marijuana known to be dangerous, such as synthetic cannabinoids, which in some instances have been associated with catastrophic outcomes.5 The slippery slope is real: if the message becomes that some (or most) marijuana is benign or even therapeutic, what is to curb a widespread and unregulated epidemic?

YOUTH AT RISK

Some groups are more vulnerable than others to the potential negative effects of cannabis. In a study at a medical cannabis dispensary in San Francisco,6 adolescents and young adults used more marijuana than older users did and had higher rates of “use when bored” and eventual pharmacologic dependence. Sustained use of marijuana by young people places them at risk of serious psychiatric disorders, with numerous studies demonstrating the unfolding of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and more.7

As the authors point out, cannabis may be contraindicated in those already burdened with mental health problems. If we recall that comorbid psychiatric disorders are the norm rather than the exception in chronic pain conditions,8 can we recommend cannabis therapy for most patients with chronic pain with confidence that it will not cause unintended problems? Evidence already shows that even well-established medical marijuana services attract (and perhaps unintentionally debilitate) a certain high-risk demographic: young, socioeconomically disadvantaged men with other comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, who ultimately rank poorly in functional health measures compared with the general population.9

NOT REEFER MADNESS, BUT REEFER CAUTION

I am not advocating the fear-mongering misinformation campaigns of the past. We should not exaggerate and warn about “reefer madness” or equate marijuana with untruths about random violence or complete bedlam. Nonetheless, concerns for widespread amotivation, worsening psychiatric states, chronic disability, and chemical dependence are very real.

Needed are tightly regulated, well-controlled, and long-term prospective studies involving isolated CBD formulations lacking THC. Over time, perhaps only formulations approved by the US Food and Drug Administration will be embraced. In the meantime, more comprehensive approaches should be recommended, such as team-based interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs that have shown efficacy in handling chronic pain complexities.10,11

If such steps are unlikely, physicians should nonetheless stand united in sending a message of cautious optimism regarding medical marijuana, educating their patients not only about recently advertised potential yet inconclusive benefits, but also about the well-known and actual certitudes of its harms for use in chronic pain management. There is plenty of bad and worse information to share with patients, and there is a slippery slope of epidemic proportions to be wary about.

- Modesto-Lowe V, Bojka R, Alvarado C. Cannabis for peripheral neuropathy: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(12):943–949. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17115

- Wailoo K. Pain: A Political History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014.

- Mucke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, Petzke F, Hauser W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 3:CD012182. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2

- Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/bcp.13710

- Patel NA, Jerry JM, Jimenez XF, Hantus ST. New-onset refractory status epilepticus associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids. Psychosomatics 2017; 58(2):180–186. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2016.10.006

- Haug NA, Padula CB, Sottile JE, Vandrey R, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabis use patterns and motives: a comparison of younger, middle-aged, and older medical cannabis dispensary patients. Addict Behav 2017; 72:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.006

- Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, Bonato S, Lev-Ran S, Rehm J. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2018; 79(4)pii:17r11839. doi:10.4088/JCP.17r11839

- Velly AM, Mohit S. Epidemiology of pain and relation to psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2017; pii:S0278–5846(17)30194–X. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.012

- Fischer B, Ialomiteanu AR, Aeby S, Rudzinski K, Kurdyak P, Rehm J. Substance use, health, and functioning characteristics of medical marijuana program participants compared to the general adult population in Ontario (Canada). J Psychoactive Drugs 2017; 49(1):31–38. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1264648

- Shah A, Craner J, Cunningham JL. Medical cannabis use among patients with chronic pain in an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program: characterization and treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 77:95–100. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.012

- Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16(2):147–152. doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0252-4

The narrative review by Modesto-Lowe et al1 in this issue on the potential therapeutic use of cannabis for peripheral neuropathy is only the latest in a vogue string of examinations on how medical marijuana may be used to manage complex conditions. While the authors should be lauded for acknowledging that the role of cannabis in treating peripheral neuropathy is far from settled (“the unknown” in their title), the high stakes involved warrant even more stringent scrutiny than they suggest.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of chronic opioid use with massive repercussions, and it did not start overnight. Mounting calls for liberalizing narcotic use across a broad range of pain conditions accumulated gradually during the patient-advocacy era of the 1990s, with supporting “evidence” coming mostly from small uncontrolled studies, anecdotal reports, and industry pressure.2 Although cannabis and opioids are not interchangeable, we should be cautious about concluding that cannabis is effective and that it should be used to treat chronic pain.

CHRONIC PAIN IS COMPLICATED

Peripheral neuropathy, by definition, is a chronic pain condition. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is characterized by biologic, psychologic, and social complexities that require nuance to manage and study.

Such nuance is lacking in most recent reviews of the medical use of cannabis. The conditions in question are often studied as if they were transient and acute, eg, employing short-term studies and rudimentary measures such as numeric pain-rating scales or other snapshots of pain intensity. Results of these shortsighted assessments are impossible to extrapolate to long-term outcomes.

Whether cannabis therapy for chronic pain conditions is sustainable remains to be seen. Outcomes in chronic pain should not be defined simply by pain reduction, but by other dimensions such as changes in pain-related disability and quality of life, development of pharmacologic tolerance or dependence, adverse effects, and other “collateral damage.” We are far from understanding these issues, which require highly controlled and regulated longitudinal studies.

A recent Cochrane review3 of the efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain found that harms might outweigh the benefits. The quality of evidence was rated as very low to moderate; the reviewers cited small sample sizes and exclusion of important subgroups of patients (eg, those with substance abuse or other psychiatric comorbidities). Such exclusions are the crux of a major problem with cannabis research: studies are not naturalistic. The gritty reality of chronic pain management is paramount, and failing to consider the high-risk biopsychosocial factors typical of patients with chronic pain is naïve and, frankly, dangerous.

COGNITIVE AND MOTIVATIONAL PROBLEMS

The true danger of cannabis lies in what we already know with certainty. As the authors discuss, cannabis undisputedly results in dose-dependent cognitive and motivational problems. If we are preaching physical therapy and home exercise to counter deconditioning, socialization to reverse depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy to increase coping, returning to work to prevent prolonged disability, and other active measures to prevent pain from becoming chronic, then why would we suggest treatments known to blunt motivation, energy, concentration, and overall mood? As a general central nervous system suppressant,4 cannabis works broadly against our best efforts to rehabilitate patients and restore their overall function.

ALL CANNABIS IS NOT THE SAME

The authors use the general term cannabis in their title, yet rightly unpack the differences between medical marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD). However, in the minds of untrained and pain-stricken patients seeking rapid relief and practical solutions, such distinctions are likely irrelevant.

The danger in the barrage of publications examining cannabis vs medical marijuana vs THC vs CBD is that they all communicate an unintentional yet problematic message: that marijuana of some sort for pain is acceptable to try. And in the face of financial pressures, changing legal landscapes, insurance coverage volatility, and access issues, are patients really going to always secure prescriptions for well-regulated CBD (lacking psychoactive THC) from thoughtful and well-informed physicians, or will they turn to convenient street suppliers?

Simplified perceptions of safety and efficacy across all cannabis products do not help. More troublesome would be to extrapolate safety to other forms of marijuana known to be dangerous, such as synthetic cannabinoids, which in some instances have been associated with catastrophic outcomes.5 The slippery slope is real: if the message becomes that some (or most) marijuana is benign or even therapeutic, what is to curb a widespread and unregulated epidemic?

YOUTH AT RISK

Some groups are more vulnerable than others to the potential negative effects of cannabis. In a study at a medical cannabis dispensary in San Francisco,6 adolescents and young adults used more marijuana than older users did and had higher rates of “use when bored” and eventual pharmacologic dependence. Sustained use of marijuana by young people places them at risk of serious psychiatric disorders, with numerous studies demonstrating the unfolding of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and more.7

As the authors point out, cannabis may be contraindicated in those already burdened with mental health problems. If we recall that comorbid psychiatric disorders are the norm rather than the exception in chronic pain conditions,8 can we recommend cannabis therapy for most patients with chronic pain with confidence that it will not cause unintended problems? Evidence already shows that even well-established medical marijuana services attract (and perhaps unintentionally debilitate) a certain high-risk demographic: young, socioeconomically disadvantaged men with other comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, who ultimately rank poorly in functional health measures compared with the general population.9

NOT REEFER MADNESS, BUT REEFER CAUTION

I am not advocating the fear-mongering misinformation campaigns of the past. We should not exaggerate and warn about “reefer madness” or equate marijuana with untruths about random violence or complete bedlam. Nonetheless, concerns for widespread amotivation, worsening psychiatric states, chronic disability, and chemical dependence are very real.

Needed are tightly regulated, well-controlled, and long-term prospective studies involving isolated CBD formulations lacking THC. Over time, perhaps only formulations approved by the US Food and Drug Administration will be embraced. In the meantime, more comprehensive approaches should be recommended, such as team-based interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs that have shown efficacy in handling chronic pain complexities.10,11

If such steps are unlikely, physicians should nonetheless stand united in sending a message of cautious optimism regarding medical marijuana, educating their patients not only about recently advertised potential yet inconclusive benefits, but also about the well-known and actual certitudes of its harms for use in chronic pain management. There is plenty of bad and worse information to share with patients, and there is a slippery slope of epidemic proportions to be wary about.

The narrative review by Modesto-Lowe et al1 in this issue on the potential therapeutic use of cannabis for peripheral neuropathy is only the latest in a vogue string of examinations on how medical marijuana may be used to manage complex conditions. While the authors should be lauded for acknowledging that the role of cannabis in treating peripheral neuropathy is far from settled (“the unknown” in their title), the high stakes involved warrant even more stringent scrutiny than they suggest.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of chronic opioid use with massive repercussions, and it did not start overnight. Mounting calls for liberalizing narcotic use across a broad range of pain conditions accumulated gradually during the patient-advocacy era of the 1990s, with supporting “evidence” coming mostly from small uncontrolled studies, anecdotal reports, and industry pressure.2 Although cannabis and opioids are not interchangeable, we should be cautious about concluding that cannabis is effective and that it should be used to treat chronic pain.

CHRONIC PAIN IS COMPLICATED

Peripheral neuropathy, by definition, is a chronic pain condition. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is characterized by biologic, psychologic, and social complexities that require nuance to manage and study.

Such nuance is lacking in most recent reviews of the medical use of cannabis. The conditions in question are often studied as if they were transient and acute, eg, employing short-term studies and rudimentary measures such as numeric pain-rating scales or other snapshots of pain intensity. Results of these shortsighted assessments are impossible to extrapolate to long-term outcomes.

Whether cannabis therapy for chronic pain conditions is sustainable remains to be seen. Outcomes in chronic pain should not be defined simply by pain reduction, but by other dimensions such as changes in pain-related disability and quality of life, development of pharmacologic tolerance or dependence, adverse effects, and other “collateral damage.” We are far from understanding these issues, which require highly controlled and regulated longitudinal studies.

A recent Cochrane review3 of the efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain found that harms might outweigh the benefits. The quality of evidence was rated as very low to moderate; the reviewers cited small sample sizes and exclusion of important subgroups of patients (eg, those with substance abuse or other psychiatric comorbidities). Such exclusions are the crux of a major problem with cannabis research: studies are not naturalistic. The gritty reality of chronic pain management is paramount, and failing to consider the high-risk biopsychosocial factors typical of patients with chronic pain is naïve and, frankly, dangerous.

COGNITIVE AND MOTIVATIONAL PROBLEMS

The true danger of cannabis lies in what we already know with certainty. As the authors discuss, cannabis undisputedly results in dose-dependent cognitive and motivational problems. If we are preaching physical therapy and home exercise to counter deconditioning, socialization to reverse depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy to increase coping, returning to work to prevent prolonged disability, and other active measures to prevent pain from becoming chronic, then why would we suggest treatments known to blunt motivation, energy, concentration, and overall mood? As a general central nervous system suppressant,4 cannabis works broadly against our best efforts to rehabilitate patients and restore their overall function.

ALL CANNABIS IS NOT THE SAME

The authors use the general term cannabis in their title, yet rightly unpack the differences between medical marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD). However, in the minds of untrained and pain-stricken patients seeking rapid relief and practical solutions, such distinctions are likely irrelevant.

The danger in the barrage of publications examining cannabis vs medical marijuana vs THC vs CBD is that they all communicate an unintentional yet problematic message: that marijuana of some sort for pain is acceptable to try. And in the face of financial pressures, changing legal landscapes, insurance coverage volatility, and access issues, are patients really going to always secure prescriptions for well-regulated CBD (lacking psychoactive THC) from thoughtful and well-informed physicians, or will they turn to convenient street suppliers?

Simplified perceptions of safety and efficacy across all cannabis products do not help. More troublesome would be to extrapolate safety to other forms of marijuana known to be dangerous, such as synthetic cannabinoids, which in some instances have been associated with catastrophic outcomes.5 The slippery slope is real: if the message becomes that some (or most) marijuana is benign or even therapeutic, what is to curb a widespread and unregulated epidemic?

YOUTH AT RISK

Some groups are more vulnerable than others to the potential negative effects of cannabis. In a study at a medical cannabis dispensary in San Francisco,6 adolescents and young adults used more marijuana than older users did and had higher rates of “use when bored” and eventual pharmacologic dependence. Sustained use of marijuana by young people places them at risk of serious psychiatric disorders, with numerous studies demonstrating the unfolding of schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and more.7

As the authors point out, cannabis may be contraindicated in those already burdened with mental health problems. If we recall that comorbid psychiatric disorders are the norm rather than the exception in chronic pain conditions,8 can we recommend cannabis therapy for most patients with chronic pain with confidence that it will not cause unintended problems? Evidence already shows that even well-established medical marijuana services attract (and perhaps unintentionally debilitate) a certain high-risk demographic: young, socioeconomically disadvantaged men with other comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, who ultimately rank poorly in functional health measures compared with the general population.9

NOT REEFER MADNESS, BUT REEFER CAUTION

I am not advocating the fear-mongering misinformation campaigns of the past. We should not exaggerate and warn about “reefer madness” or equate marijuana with untruths about random violence or complete bedlam. Nonetheless, concerns for widespread amotivation, worsening psychiatric states, chronic disability, and chemical dependence are very real.

Needed are tightly regulated, well-controlled, and long-term prospective studies involving isolated CBD formulations lacking THC. Over time, perhaps only formulations approved by the US Food and Drug Administration will be embraced. In the meantime, more comprehensive approaches should be recommended, such as team-based interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs that have shown efficacy in handling chronic pain complexities.10,11

If such steps are unlikely, physicians should nonetheless stand united in sending a message of cautious optimism regarding medical marijuana, educating their patients not only about recently advertised potential yet inconclusive benefits, but also about the well-known and actual certitudes of its harms for use in chronic pain management. There is plenty of bad and worse information to share with patients, and there is a slippery slope of epidemic proportions to be wary about.

- Modesto-Lowe V, Bojka R, Alvarado C. Cannabis for peripheral neuropathy: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(12):943–949. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17115

- Wailoo K. Pain: A Political History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014.

- Mucke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, Petzke F, Hauser W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 3:CD012182. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2

- Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/bcp.13710

- Patel NA, Jerry JM, Jimenez XF, Hantus ST. New-onset refractory status epilepticus associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids. Psychosomatics 2017; 58(2):180–186. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2016.10.006

- Haug NA, Padula CB, Sottile JE, Vandrey R, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabis use patterns and motives: a comparison of younger, middle-aged, and older medical cannabis dispensary patients. Addict Behav 2017; 72:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.006

- Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, Bonato S, Lev-Ran S, Rehm J. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2018; 79(4)pii:17r11839. doi:10.4088/JCP.17r11839

- Velly AM, Mohit S. Epidemiology of pain and relation to psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2017; pii:S0278–5846(17)30194–X. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.012

- Fischer B, Ialomiteanu AR, Aeby S, Rudzinski K, Kurdyak P, Rehm J. Substance use, health, and functioning characteristics of medical marijuana program participants compared to the general adult population in Ontario (Canada). J Psychoactive Drugs 2017; 49(1):31–38. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1264648

- Shah A, Craner J, Cunningham JL. Medical cannabis use among patients with chronic pain in an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program: characterization and treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 77:95–100. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.012

- Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16(2):147–152. doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0252-4

- Modesto-Lowe V, Bojka R, Alvarado C. Cannabis for peripheral neuropathy: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(12):943–949. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17115

- Wailoo K. Pain: A Political History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014.

- Mucke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, Petzke F, Hauser W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 3:CD012182. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2

- Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/bcp.13710

- Patel NA, Jerry JM, Jimenez XF, Hantus ST. New-onset refractory status epilepticus associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids. Psychosomatics 2017; 58(2):180–186. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2016.10.006

- Haug NA, Padula CB, Sottile JE, Vandrey R, Heinz AJ, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabis use patterns and motives: a comparison of younger, middle-aged, and older medical cannabis dispensary patients. Addict Behav 2017; 72:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.006

- Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, Bonato S, Lev-Ran S, Rehm J. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2018; 79(4)pii:17r11839. doi:10.4088/JCP.17r11839

- Velly AM, Mohit S. Epidemiology of pain and relation to psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2017; pii:S0278–5846(17)30194–X. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.012

- Fischer B, Ialomiteanu AR, Aeby S, Rudzinski K, Kurdyak P, Rehm J. Substance use, health, and functioning characteristics of medical marijuana program participants compared to the general adult population in Ontario (Canada). J Psychoactive Drugs 2017; 49(1):31–38. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1264648

- Shah A, Craner J, Cunningham JL. Medical cannabis use among patients with chronic pain in an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program: characterization and treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 77:95–100. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.012

- Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16(2):147–152. doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0252-4

Moving On

After seven years at the helm of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I am both pleased to hand over the reins and sad to let them go. My time as Editor in Chief has been wonderful, challenging, and fulfilling.

When I began my tenure, JHM managed approximately 350 papers annually, and published 10 times per year. We had no social media presence, a developing editorial sense (and developing Editor in Chief), and a pool of hard-working and passionate Editors. As of this year, we have handled more than 700 papers and are publishing content monthly, online only, and online first. Our dedicated team is deeply passionate about making every paper better through interaction with the authors—whether we accept it for publication or not.

JHM has added a presence on Facebook and Twitter, launched a Twitter Journal Club as a regular offering (#JHMChat), added visual abstracts to our Tweets and Facebook postings, and researched how these novel approaches increase not only the Journal’s social media presence but also its public face. Our efforts in social media were trendsetting in peer-reviewed literature, and the Editors who lead those efforts—Vineet Arora and Charlie Wray—are asked to consult for other journals regularly.

We launched two new series— Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps, and Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason—with help from the ABIM Foundation and visionary Editors, Andy Masica, Ann Sheehy, and Lenny Feldman. These papers have pushed Hospitalists and Hospital Medicine to think carefully about the simple things we do every day, to think broadly about how to move past the initial ‘low-hanging fruit’ of value improvement, and point us towards policy and intervention approaches that are disruptive rather than incremental.

A special thank you to Som Mookherjee, Brian Harte, Dan Hunt, and Read Pierce who ably developed the Clinical Care Conundrums and Review series. They are assisted by teams of national correspondents and many contributors who’ve submitted work for those series.

I have been blessed by a team of more than a dozen Associate Editors who have ably, expeditiously, and collegially managed more than 2,000 papers. These Editors work out of a sense of altruism and commitment to Hospital Medicine and have made huge individual contributions to JHM through their reviewing expertise and ensuring that the editorial sense for JHM is as broad and innovative as our field.

Finally, I must thank my core team of Senior Deputy Editors who have shouldered the majority of editorial work, mentored Editors (including me) and Peer Reviewers, and provided strategic guidance.

How peer-reviewed journals are published is changing rapidly. Setting aside the questions of how we consume our medical literature and the transition from paper to digital, old financial models depending on subscriptions and advertising are either dying or evolving into something very different. The challenge is that the new model is very unclear and the old model based on ads and subscriptions is clearly nonviable but is the primary way to support the work of producing a journal. Moving from the current model to one based on clicks, views, or downloads will come down to who will derive benefit from those clicks/downloads, who will be willing to pay to read and learn from the work of authors, or who views that activity as being worthy enough advertise somewhere in that process or to monetize the data garnered from readers’ activities. In addition, many journals, including JHM, are supported by professional societies. While professional societies have a goal to serve their members, the goal of the peer-reviewed journal is to independently and broadly represent the field. One must reflect the other, but space between the two will always be required.

The speed with which research takes place is too slow, and the process of getting evidence into print (much less adopted) is even slower. But, this too is changing; the role of peer review and the publication process is evolving. In order to speed the potential discovery of new innovations, prepublication repositories (such as BioRxViv) are gaining popularity; well-publicized scandals around peer reviewing rings 1 have not gone unnoticed, and have produced greater interest in using prepublication comments and online discussions as early forms of review. As a result, the disintermediation between scientist and ‘evidence’ is paralleling the disintermediation between events and messengers elsewhere. One need only review Twitter for a moment to get a sense for how crowdsourcing can lead to evidence (or news) generation for good or ill. I agree that while the end of journals (as we understand them now) is upon us, these are also opportunities for JHM as it enters its new phase and a place for leadership. 2

I am proud of what we have done at JHM in the last seven years. We have grown substantially. We have innovated and provided great service to our authors and the field of Hospital Medicine. Our growth and forward-looking approaches to social media and our digital footprint put the journal on a great path towards adapting to the trends in Hospital Medicine research and peer-reviewed publishing. Our focus on being doctors who care for patients and our teams—not just doctors who care for hospitals—is supporting the field and our practice. I look forward to seeing where JHM goes next.

1. Retraction Watch. BioMedCentral retracting 43 papers for fake peer reviews. March 26, 2015; http://retractionwatch.com/2015/03/26/biomed-central-retracting-43-papers-for-fake-peer-review/. Accessed November 12, 2018.

2. Krumholz HM. The End of Journals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(6):533-534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002415. PubMed

After seven years at the helm of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I am both pleased to hand over the reins and sad to let them go. My time as Editor in Chief has been wonderful, challenging, and fulfilling.

When I began my tenure, JHM managed approximately 350 papers annually, and published 10 times per year. We had no social media presence, a developing editorial sense (and developing Editor in Chief), and a pool of hard-working and passionate Editors. As of this year, we have handled more than 700 papers and are publishing content monthly, online only, and online first. Our dedicated team is deeply passionate about making every paper better through interaction with the authors—whether we accept it for publication or not.

JHM has added a presence on Facebook and Twitter, launched a Twitter Journal Club as a regular offering (#JHMChat), added visual abstracts to our Tweets and Facebook postings, and researched how these novel approaches increase not only the Journal’s social media presence but also its public face. Our efforts in social media were trendsetting in peer-reviewed literature, and the Editors who lead those efforts—Vineet Arora and Charlie Wray—are asked to consult for other journals regularly.

We launched two new series— Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps, and Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason—with help from the ABIM Foundation and visionary Editors, Andy Masica, Ann Sheehy, and Lenny Feldman. These papers have pushed Hospitalists and Hospital Medicine to think carefully about the simple things we do every day, to think broadly about how to move past the initial ‘low-hanging fruit’ of value improvement, and point us towards policy and intervention approaches that are disruptive rather than incremental.

A special thank you to Som Mookherjee, Brian Harte, Dan Hunt, and Read Pierce who ably developed the Clinical Care Conundrums and Review series. They are assisted by teams of national correspondents and many contributors who’ve submitted work for those series.

I have been blessed by a team of more than a dozen Associate Editors who have ably, expeditiously, and collegially managed more than 2,000 papers. These Editors work out of a sense of altruism and commitment to Hospital Medicine and have made huge individual contributions to JHM through their reviewing expertise and ensuring that the editorial sense for JHM is as broad and innovative as our field.

Finally, I must thank my core team of Senior Deputy Editors who have shouldered the majority of editorial work, mentored Editors (including me) and Peer Reviewers, and provided strategic guidance.

How peer-reviewed journals are published is changing rapidly. Setting aside the questions of how we consume our medical literature and the transition from paper to digital, old financial models depending on subscriptions and advertising are either dying or evolving into something very different. The challenge is that the new model is very unclear and the old model based on ads and subscriptions is clearly nonviable but is the primary way to support the work of producing a journal. Moving from the current model to one based on clicks, views, or downloads will come down to who will derive benefit from those clicks/downloads, who will be willing to pay to read and learn from the work of authors, or who views that activity as being worthy enough advertise somewhere in that process or to monetize the data garnered from readers’ activities. In addition, many journals, including JHM, are supported by professional societies. While professional societies have a goal to serve their members, the goal of the peer-reviewed journal is to independently and broadly represent the field. One must reflect the other, but space between the two will always be required.

The speed with which research takes place is too slow, and the process of getting evidence into print (much less adopted) is even slower. But, this too is changing; the role of peer review and the publication process is evolving. In order to speed the potential discovery of new innovations, prepublication repositories (such as BioRxViv) are gaining popularity; well-publicized scandals around peer reviewing rings 1 have not gone unnoticed, and have produced greater interest in using prepublication comments and online discussions as early forms of review. As a result, the disintermediation between scientist and ‘evidence’ is paralleling the disintermediation between events and messengers elsewhere. One need only review Twitter for a moment to get a sense for how crowdsourcing can lead to evidence (or news) generation for good or ill. I agree that while the end of journals (as we understand them now) is upon us, these are also opportunities for JHM as it enters its new phase and a place for leadership. 2

I am proud of what we have done at JHM in the last seven years. We have grown substantially. We have innovated and provided great service to our authors and the field of Hospital Medicine. Our growth and forward-looking approaches to social media and our digital footprint put the journal on a great path towards adapting to the trends in Hospital Medicine research and peer-reviewed publishing. Our focus on being doctors who care for patients and our teams—not just doctors who care for hospitals—is supporting the field and our practice. I look forward to seeing where JHM goes next.

After seven years at the helm of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I am both pleased to hand over the reins and sad to let them go. My time as Editor in Chief has been wonderful, challenging, and fulfilling.

When I began my tenure, JHM managed approximately 350 papers annually, and published 10 times per year. We had no social media presence, a developing editorial sense (and developing Editor in Chief), and a pool of hard-working and passionate Editors. As of this year, we have handled more than 700 papers and are publishing content monthly, online only, and online first. Our dedicated team is deeply passionate about making every paper better through interaction with the authors—whether we accept it for publication or not.

JHM has added a presence on Facebook and Twitter, launched a Twitter Journal Club as a regular offering (#JHMChat), added visual abstracts to our Tweets and Facebook postings, and researched how these novel approaches increase not only the Journal’s social media presence but also its public face. Our efforts in social media were trendsetting in peer-reviewed literature, and the Editors who lead those efforts—Vineet Arora and Charlie Wray—are asked to consult for other journals regularly.

We launched two new series— Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps, and Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason—with help from the ABIM Foundation and visionary Editors, Andy Masica, Ann Sheehy, and Lenny Feldman. These papers have pushed Hospitalists and Hospital Medicine to think carefully about the simple things we do every day, to think broadly about how to move past the initial ‘low-hanging fruit’ of value improvement, and point us towards policy and intervention approaches that are disruptive rather than incremental.

A special thank you to Som Mookherjee, Brian Harte, Dan Hunt, and Read Pierce who ably developed the Clinical Care Conundrums and Review series. They are assisted by teams of national correspondents and many contributors who’ve submitted work for those series.

I have been blessed by a team of more than a dozen Associate Editors who have ably, expeditiously, and collegially managed more than 2,000 papers. These Editors work out of a sense of altruism and commitment to Hospital Medicine and have made huge individual contributions to JHM through their reviewing expertise and ensuring that the editorial sense for JHM is as broad and innovative as our field.

Finally, I must thank my core team of Senior Deputy Editors who have shouldered the majority of editorial work, mentored Editors (including me) and Peer Reviewers, and provided strategic guidance.

How peer-reviewed journals are published is changing rapidly. Setting aside the questions of how we consume our medical literature and the transition from paper to digital, old financial models depending on subscriptions and advertising are either dying or evolving into something very different. The challenge is that the new model is very unclear and the old model based on ads and subscriptions is clearly nonviable but is the primary way to support the work of producing a journal. Moving from the current model to one based on clicks, views, or downloads will come down to who will derive benefit from those clicks/downloads, who will be willing to pay to read and learn from the work of authors, or who views that activity as being worthy enough advertise somewhere in that process or to monetize the data garnered from readers’ activities. In addition, many journals, including JHM, are supported by professional societies. While professional societies have a goal to serve their members, the goal of the peer-reviewed journal is to independently and broadly represent the field. One must reflect the other, but space between the two will always be required.

The speed with which research takes place is too slow, and the process of getting evidence into print (much less adopted) is even slower. But, this too is changing; the role of peer review and the publication process is evolving. In order to speed the potential discovery of new innovations, prepublication repositories (such as BioRxViv) are gaining popularity; well-publicized scandals around peer reviewing rings 1 have not gone unnoticed, and have produced greater interest in using prepublication comments and online discussions as early forms of review. As a result, the disintermediation between scientist and ‘evidence’ is paralleling the disintermediation between events and messengers elsewhere. One need only review Twitter for a moment to get a sense for how crowdsourcing can lead to evidence (or news) generation for good or ill. I agree that while the end of journals (as we understand them now) is upon us, these are also opportunities for JHM as it enters its new phase and a place for leadership. 2

I am proud of what we have done at JHM in the last seven years. We have grown substantially. We have innovated and provided great service to our authors and the field of Hospital Medicine. Our growth and forward-looking approaches to social media and our digital footprint put the journal on a great path towards adapting to the trends in Hospital Medicine research and peer-reviewed publishing. Our focus on being doctors who care for patients and our teams—not just doctors who care for hospitals—is supporting the field and our practice. I look forward to seeing where JHM goes next.

1. Retraction Watch. BioMedCentral retracting 43 papers for fake peer reviews. March 26, 2015; http://retractionwatch.com/2015/03/26/biomed-central-retracting-43-papers-for-fake-peer-review/. Accessed November 12, 2018.

2. Krumholz HM. The End of Journals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(6):533-534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002415. PubMed

1. Retraction Watch. BioMedCentral retracting 43 papers for fake peer reviews. March 26, 2015; http://retractionwatch.com/2015/03/26/biomed-central-retracting-43-papers-for-fake-peer-review/. Accessed November 12, 2018.

2. Krumholz HM. The End of Journals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(6):533-534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002415. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

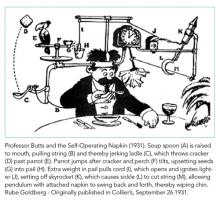

Is Hospital Discharge the Rube Goldberg Machine of Academic Internal Medicine?

One of the least taught yet most complicated tasks confronting new trainees is the bewildering process of discharging a patient. On an internal medicine service, this process can often resemble a Rube Goldberg machine, in which a “simple” task is accomplished through a series of interconnected, almost comically convoluted, yet separate steps that are triggered one after another and must be executed perfectly in sequence for success. It seems easy at first; just tap out a few sentences in the discharge paperwork, do a quick medication reconciliation, and a click of a button later, voila! The patient magically falls off the list and is on their merry way home. In reality, it only takes one wrench thrown into the Rube Goldberg machine to take down the whole operation. Much to the chagrin of internal medicine interns across the country, residents quickly learn that discharge planning is usually far from straightforward and that a myriad of obstacles (often dynamic and frustratingly unpredictable) can stand in the way of a successful discharge.

While some surgical services can streamline discharge processes to target defined lengths of stay based on a particular diagnosis, general medicine patients tend to have greater numbers of comorbid conditions, complex hospital courses, and wider variation in access to posthospital healthcare. In addition, there is very little formal instruction in transitions of care, and most residents identify direct patient care (learning by doing) as the primary mode of education.1,2 Struggling through the process of finding an appropriate placement, ensuring adequate outpatient follow-up, and untangling a jumbled mess of a medication reconciliation is often the only way that housestaff learn the Sisyphean task of transitioning care out of the hospital. The unpredictability and intensity of patient care adds to the ever growing list of competing demands on the time and attention of residents. Attendings face pressure on all sides to not only provide exemplary patient care and an educational experience but also to optimize hospital throughput by discharging patients as soon as possible (and ideally before noon). No wonder that the discharge process can threaten to unravel at any time, with delays and complications in discharge metamorphosing into increased length of stay (LOS), poorer outcomes, and increased 30-day readmission rates. As on-the-ground providers, what realities do we face when challenging ourselves to discharge patients before noon, and what practical changes in our workflow can we make to reach this goal?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Zoucha et al. examine these questions in real time by identifying barriers preventing both “definite” and “possible” discharges at three representative time points over the course of randomly chosen weekdays. They surveyed both housestaff and attendings at five academic hospitals across the United States, and the majority of patients were cared for on teaching services.3 Reflecting the inherent differences in workflow between teaching and nonteaching services, delays in definite discharges on teaching services were most often hindered by completing rounds and the need to staff the patient with the attending, whereas nonresident services identified other patient-care-related (both urgent and nonurgent) issues to be the culprits. Late-afternoon discharges were delayed on teaching services due to outstanding paperwork and follow-up arrangements, both of which most senior residents are keenly aware of and make their best effort to complete ahead of time. Patients designated as “possible” discharges were awaiting clinical improvement and resolution of disposition issues dependent on social work and safe placement, which reasonably seemed independent of service type. These descriptive findings suggest that nonresident services are more efficient than resident teams, and we are keen to identify novel solutions, such as dedicated discharge coordinators,4 to facilitate the discharge process on resident teams without detracting from the educational value of the rotation.

Zoucha et al. also found that factors beyond our control (having a lower daily census, attending on a nonresident service) were significantly associated with both earlier discharge order entry times and the actual time of patient discharge.3 While it is tempting to foist the entirety of the blame on extrinsic factors such as discharge placement and insurance issues, the reality is there might be some workflow changes that could expedite the discharge process. The authors are correct to emphasize that rounding style, in which discharges are prioritized to be seen first, is a behavior modification worth targeting. The percentage of teams that routinely see discharges first is not well studied, as other factors, such as clinically unstable patients, new admissions from overnight, and even mundane characteristics such as geographic location in the hospital, can also compete for prioritization in rounding order. Given the authors’ findings, we are eager to see further work in this area as prioritization of discharges during rounds could conceivably be studied within the context of a randomized controlled trial. Other innovations in rounding styles such as rounding-in-flow5 (in which all tasks are completed for a single patient before rounding on the next patient) can also significantly reduce the time to discharge order placement.

With help from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, we are actively studying bottlenecks in the discharge process by developing an interactive platform focused on delivering real-time information to all members of the healthcare team. Rapid rounds are held every morning with the attending physician, floor nursing leadership, physical therapy, social worker, and case management to quickly identify pending tasks, anticipated disposition, and a target date of discharge. Efficiency is key, as each team is limited to approximately 5-10 minutes. Previous studies (mostly pre–post studies) have shown that this simple intervention significantly reduced LOS,6,7 increased rates of discharge before noon,8 and was improved by electronic tracking tools.9 Our multidisciplinary rounds are unique in that information is then entered into an intuitive, web-based platform, which allows consolidation and analysis that permits generation of real-time statistics. By standardizing the discharge planning process, we hope to streamline a previously fragmented process and maximize the efficiency of hospital resource utilization.

Ultimately, high-quality care of complex patients on internal medicine services from admission to discharge requires hard work, smart utilization of resources, and a little bit of luck. There may not be a secret ingredient that guarantees perfectly efficient discharges 100% of the time, but this study inspires us to ponder additional approaches to this longstanding problem. The authors are to be congratulated for a rigorous study that illuminates where we as healthcare providers are able to realistically intervene to expedite the discharge process. First, having a lower census cap may not be possible in this era of maximal hospital usage, but this work suggests that thoughtful management of time on rounds may be a way to address the underlying problem. Secondly, the superior efficiency of nonteaching services may merely reflect the increased experience of the providers, and a realistic solution could be to implement a formal curriculum to educate housestaff about the discharge process, which would simultaneously address residency competency standards for transitions of care. Finally, the role of innovative informatics tools will surely open further avenues of investigation, as we continually evolve in response to intensifying standards of modern, efficient healthcare delivery in the 21st century. It may not be possible to eliminate the complexity from this particular Rube Goldberg machine, but taking the steps above may allow us to implement as many fail-safes as we can.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Young E, Stickrath C, McNulty M, et al. Residents’ exposure to educational experiences in facilitating hospital discharges. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):184-189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00503.1. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Curry L, et al. “Learning by doing” - Resident perspectives on developing competency in high-quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188-1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2094-5. PubMed

3. Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):816-822. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3074. PubMed

4. Finn KM, Heffner R, Chang Y, et al. Improving the discharge process by embedding a discharge facilitator in a resident team. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(9):494-500. doi: 10.1002/jhm.924. PubMed

5. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00324.1. PubMed