User login

Testifying for civil commitment

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

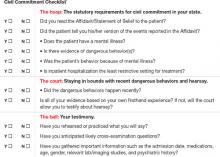

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).

Clinical trials support new algorithm for treating pediatric bipolar mania

Five recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics for treating bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, but 4 of these 5 trials remain unpublished. The lag time between the completion of these trials and publication of their results—typically 4 to 5 years1—leaves psychiatrists without important evidence to explain to families and critics2 why they might recommend using these powerful medications in children with mental illness.

This article previews the preliminary results of these 5 RCTs of atypical antipsychotics, offers a treatment algorithm supported by this evidence, and discusses how to manage potentially serious risks when using antipsychotics to treat children and adolescents with bipolar disorder (BPD).

Where do atypical antipsychotics fit in?

Details of the 5 industry-sponsored RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with bipolar I manic or mixed episodes are summarized in Table 1.3-7 Only the olanzapine study4 has been published; data from the other 4 trials were presented at medical meetings in 2007 and 2008.

Change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was the primary outcome measure in these 5 trials, and each compound was more effective than placebo. The trials demonstrated statistically significant and clinically relevant differences between each antipsychotic and placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT)—how many patients need to be treated for 1 to benefit in a controlled clinical trial—ranged from 2 to 4. For comparison, the NNT for statins in the prevention of coronary events is 12 to 22,8 and the NNT in an analysis of trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for pediatric major depressive disorder was 9.9 Thus, an NNT of ≤4 represents a clinically significant effect.

Risperidone is FDA-approved for short-term treatment of acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in patients age 10 to 17. Aripiprazole is approved for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar I manic or mixed episodes (with or without psychosis) as monotherapy or with lithium or valproate in patients age 10 to 17. In June, an FDA advisory committee recommended pediatric bipolar indications for olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

‘Mood stabilizers’ such as lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine have been used for years to treat bipolar mania in adults, adolescents, and children, despite limited supporting evidence. Preliminary results of a National Institute of Mental Health-funded double-blind RCT provide insights on their efficacy.10

The 153 outpatients age 7 to 17 in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode were randomly assigned to lithium, divalproex, or placebo for 8 weeks. Response rates—based on a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved)—were divalproex, 54%; lithium, 42%; and placebo, 29%. Lithium showed a trend toward efficacy but did not clearly separate from placebo on the primary outcome measures. Effect sizes for lithium and divalproex were moderate.10

Only 1 study has compared a mood stabilizer with an atypical antipsychotic for treating mania in adolescents. In a double-blind trial, DelBello et al11 randomly assigned 50 patients age 12 to 18 with a bipolar I manic or mixed episode to quetiapine, 400 to 600 mg/d, or divalproex, serum level 80 to 120 μg/mL, for 28 days. Manic symptoms resolved more rapidly, and remission rates measured by the YMRS were higher with quetiapine than with divalproex. Both medications were well tolerated.

Combination therapy. BPD as it presents in children and adolescents is often difficult to treat because of the disorder’s various phases (manic, depressed, mixed), frequent psychotic symptoms, and high rate of comorbidity. Pediatric BPD patients frequently require several psychotropics, including mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 30 adolescents in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode initially received divalproex, 20 mg/kg/d, then were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of adjunctive quetiapine, titrated to 450 mg/d in 7 days (n=15), or placebo (n=15). Those receiving divalproex plus quetiapine showed a statistically significant greater reduction in manic symptoms (P=.03) and a higher response rate (87% vs 53%, P=.05), compared with those receiving divalproex and placebo. This suggests that a mood stabilizer plus an atypical antipsychotic is more effective than a mood stabilizer alone for adolescent mania. Quetiapine was well tolerated.12

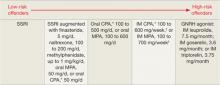

Treatment. The American Psychiatric Association’s outdated 2002 practice guideline for acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in adults recommends lithium, valproate, and/or an antipsychotic.13 The more recent Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines recommend monotherapy with lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone for adults with euphoric or irritable manic or hypomanic symptoms.14

Based on the TMAP algorithm, recent clinical trial evidence, and our experience in treating pediatric BPD, we offer an approach for treating mania/hypomania in patients age 10 to 17 (see Proposed Algorithm). For dosing and precautions when using atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with BPD, see Table 2.15-17

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses (such as anxiety disorders) are prevalent in adolescents with BPD. Evidence in adults and adolescents suggests that some atypical antipsychotics may provide additional benefit for these conditions as well. Thus, consider comorbid conditions and symptoms when choosing antimanic agents.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common comorbidity in children with BPD, and stimulant medications are most often prescribed to treat inattentiveness and hyperactivity. Caution is imperative when treating bipolar youth with stimulants, which can exacerbate manic symptoms. Treat the patient’s mania before adding or reintroducing stimulant medication. Research and clinical experience suggest that if you first stabilize these patients on a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic, adding a stimulant can be very helpful in treating comorbid ADHD symptoms. Start with low stimulant doses, and increase slowly.

Table 1

RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in patients age 10 to 17

with bipolar I disorder*

| Antipsychotic and source | Bipolar I episode (# of subjects) | Trial duration (days) | Dosage (mg/d) | Response rate or YMRS score change | NNT | Mean weight gain (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone Pandina et al3 AACAP 2007 | Manic, mixed (169) | 21 | 0.5 to 2.5 3 to 6 | 59% 63% | 3.3 3.5 | 1.9 1.4 |

| Olanzapine Tohen et al4 | Manic, mixed (161) | 21 | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 49% | 4.1 | 3.7 ± 2.2 |

| Quetiapine DelBello et al5 AACAP 2007 | Manic (284) | 21 | 400 600 | 64% 58% | 4.4 4.2 | 1.7 1.7 |

| Aripiprazole Wagner et al6 ACNP 2007 | Manic, mixed (296) | 28 | 10 30 | 45% 64% | 4.1 2.4 | 0.9 0.54 |

| Ziprasidone DelBello et al7 APA 2008 | Manic, mixed (238) | 28 | 80 to 160 | –13.83 with ziprasidone, –8.61 with placebo | 3.7 | None |

| *Each trial included a 6-month open extension phase; results are pending | ||||||

| AACAP: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; ACNP: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; APA: American Psychiatric Association; NNT: number needed to treat; RCT: randomized controlled trial; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale | ||||||

Table 2

Recommended antipsychotic use in pediatric bipolar disorder

| Drug | Starting dosage (mg) | Target dosage (mg/d) | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 2.5 to 5 at bedtime | 10 to 30 | Monitor for CYP 3A4 and 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Olanzapine | 2.5 bid | 10 to 20 | Monitor for CYP 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Quetiapine | 50 bid | 400 to 1,200 | Monitor for weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Risperidone | 0.25 bid | 1 to 2.5 | Monitor for EPS, hyperprolactinemia (and associated sexual side effects, including galactorrhea), weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Ziprasidone | 20 bid | 80 to 160 | Check baseline ECG and as dose increases or with reason for high level of concern; monitor prolactin levels |

| BMI: body mass index; CYP: cytochrome P450; ECG: electrocardiography; EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms | |||

| Source: References 15-17 | |||

Proposed Algorithm: Treating a bipolar mixed/manic episode in patients age 10 to 17

Stage 1. Consider patient’s experience with antipsychotics, body weight, and family history when choosing first-line monotherapy (1A). Quetiapine poses low risk for extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Aripiprazole and ziprasidone pose relatively low risk of weight gain. Risperidone is potent at low doses but increases prolactin levels (long-term effect unknown).

Second-line choices (1B) are mood stabilizers lithium and valproate (because of lower potency than atypical antipsychotics), and olanzapine (which—although potent—causes substantial weight gain). In case of lack of response or intolerable side effects with initial agent, select an alternate from 1A or 1B. If this is not effective, move to Stage 2.

Stage 2. Consider augmentation for patients who show partial response to monotherapy (in your clinical judgment “mild to moderately improved” but not “much or very much improved”).

Stage 3. Combination therapy could include 2 mood stabilizers (such as lithium and valproate) plus an atypical antipsychotic; 2 atypical antipsychotics; or other combinations based on patient’s past responses. No research has shown these combinations to be efficacious in bipolar children and adolescents, but we find they sometimes help those with treatment-resistant symptoms.

Duration. Maintain psychotropics 12 to 18 months. When patient is euthymic, slowly taper 1 medication across several months. If symptoms recur, reintroduce the mood-stabilizing agent(s).

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling R, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008

Managing adverse effects

Although clinically effective, atypical antipsychotics may cause serious side effects that must be recognized and managed. These include extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), tardive dyskinesia (TD), weight gain and obesity, hyperlipidemia, increased prolactin levels, and QTc changes. Counsel patients and families about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics when you consider them for children and adolescents with BPD (Table 3).

EPS. Drug-induced parkinsonism and akathisia are the most common EPS in children and adolescents with BPD treated with atypical antipsychotics.18

Correll et al19 reported a 10% rate of EPS in patients treated with aripiprazole. Treatment-emergent EPS also was observed in the RCT of risperidone.20 EPS-related adverse events were associated with higher doses of risperidone, although none of the akathisia/EPS measures were thought to be “clinically significant.”

EPS frequency was relatively low and similar to placebo in the 3-week quetiapine trial,21 and no changes in movement disorder scale scores were observed during the olanzapine or ziprasidone RCTs.4,7

Recommendations. If your pediatric patient develops EPS, first try an antipsychotic dose reduction. Because anticholinergics can contribute to antipsychotic-induced weight gain, reserve them until after a dosage reduction has been unsuccessful.

Benztropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg given 2 to 3 times daily, not to exceed 3 mg/d) or diphenhydramine (25 to 50 mg given 3 to 4 times daily; maximum dosage 5 mg/kg/d) can be effective in treating EPS. Avoid anticholinergics in children with narrow-angle glaucoma or age <3.

Akathisia may be managed with propranolol (20 to 120 mg/d in divided doses). Multiple doses (typically 3 times daily) are needed to prevent interdose withdrawal symptoms. Use this beta blocker with caution in children with asthma because of the possibility of bronchospasm.

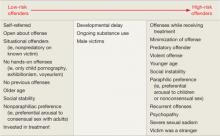

TD. Short-term trials and a meta-analysis of atypical antipsychotic trials (>11 months’ duration, subject age <18) suggest a low annual risk for TD (0.4%).22 Large, prospective, long-term trials of atypical antipsychotics are necessary to more accurately define the risk of TD in the pediatric population, however. Retrospective analyses of adolescents treated with antipsychotics suggest 3 TD risk factors:

- early age of antipsychotic use

- medication nonadherence

- concomitant use of antiparkinsonian agents.23

Kumra et al24 identified lower premorbid functioning and greater positive symptoms at baseline as factors associated with “withdrawal dyskinesia/tardive dyskinesia” in children and adolescents with early-onset psychotic-spectrum disorders treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics.

Recommendations. To minimize TD risk, use the lowest effective antipsychotic dose, monitor for abnormal involuntary movements with standardized assessments (such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale), review risks and benefits with parents and patients, and regularly evaluate the indication and need for antipsychotic therapy. It is reasonable to attempt to lower the antipsychotic dose after the patient has attained remission and been stable for 1 year.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). This complication of dopamine-blocking medications:

- is among the most serious adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment

- continues to be associated with a mortality rate of 10%.25

Recommendation. At least 1 recent review of pediatric NMS cases suggests that essential features (hyperthermia and severe muscular rigidity) are retained in children.26 Nonetheless, monitor for variant presentations; hyper thermia or muscle rigidity may be absent or develop slowly over several days in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.27

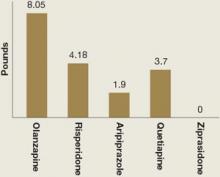

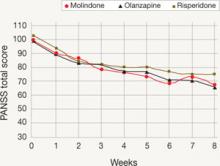

Weight gain and glucose metabolism. A major adverse effect of most atypical antipsychotics is increased appetite, weight gain, and possible obesity.28 In children, “obesity” refers to a body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile for age and sex; “over-weight” refers to BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile. Mean weight gain in the 5 atypical antipsychotic pediatric bipolar trials ranged from 0 to 8 lbs across 3 to 4 weeks of treatment (Figure).3-7

Recommendations. Emphasize diet and exercise, with restriction of high-carbohydrate food, “fast foods,” and soft drinks. Another option is a trial of metformin, which decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization.

Klein et al29 studied 39 patients age 10 to 17 with mood and psychotic disorders whose weight increased by >10% during <1 year of olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine therapy. In this 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, weight was stabilized in subjects receiving metformin, whereas those receiving placebo continued to gain weight (0.31 kg [0.68 lb]/week).

The usual starting metformin dose is 500 mg bid with meals. Increase in increments of 500 mg weekly, up to a maximum of 2,000 mg/d in divided doses. Potential side effects include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, flatulence, and headache.

Hyperlipidemia. Patients who gain weight with atypical antipsychotics also may develop hyperlipidemia. Fasting serum triglycerides >150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L) in obese children are considered to be elevated and an early sign of metabolic syndrome.30 Fasting total cholesterol >200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL (3.38 mmol/L) is consistent with hyperlipidemia.

Recommendation. Monitor and treat hyperlipidemia, which increases the risk of atherosclerosis as obese children grow older.31

Prolactin. Elevated prolactin concentrations may have deleterious effects in the developing child or adolescent, including gynecomastia, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.17 Long-term effects on growth and sexual maturation have not been fully evaluated.

The relative tendency of atypical antipsychotics to cause hyperprolactinemia is roughly: risperidone/paliperidone > olanzapine > ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine > aripiprazole.18 In the risperidone RCT, mean changes in baseline prolactin levels were 41 ng/mL for boys and 59 ng/mL in girls.3 Results of the olanzapine RCT suggest a high incidence of hyperprolactinemia (26% of girls, 63% of boys).4 Decreases in serum prolactin were observed in bipolar children and adolescents treated with aripiprazole for 30 weeks.19

Recommendations. For any pediatric patient treated with an atypical antipsychotic that increases prolactin levels:

- Obtain a baseline prolactin level.

- Repeat after 6 months of treatment or with the emergence of elevated prolactin symptoms, such as gynecomastia in boys. Ask about increases in breast size, galactorrhea, changes in menstruation, sexual functioning, and pubertal development.

Switch patients who develop any of these side effects to another atypical agent that does not increase serum prolactin.32

QTc interval prolongation. All atypical antipsychotics can cause QTc prolongation. Several cases of significant QTc prolongation have been reported in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone.33,34 In the RCT of ziprasidone, QTc prolongation was not clinically significant in most of the patients in which it was reported, and it did not lead to adverse events.34 Mean QTc change was 8.1 msec at study termination.7

Patients enrolled in clinical trails are screened very carefully, however, and those with preexisting medical abnormalities typically are excluded. Thus, these findings may have limited usefulness for “real-world” patients.

Recommendations. Until additional information is known about the cardiac effects of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents:

- Perform a careful history, review of symptoms, and physical exam looking for any history of palpitations, shortness of breath, or syncope.

- Query specifically about any family history of sudden cardiac death.

- Perform a baseline resting ECG for patients starting ziprasidone or clozapine, or for other atypicals if indicated by history, review of systems, physical exam, etc.

- For patients treated with ziprasidone or clozapine, repeat ECG as the dose increases or if the patient has cardiac symptoms (unexplained shortness of breath, palpitations, skipped beats, etc.).

Table 3

Talking to families about using antipsychotics

in children with bipolar disorder

| Effectiveness. Large, placebo-controlled studies have shown that atypical antipsychotics can significantly reduce manic symptoms in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

| Safety data. Additional 6-month safety data indicate that atypical antipsychotics continue to be effective in children and adolescents, without dramatic changes in side effects |

| Precautions. Antipsychotics are powerful medications and must be used carefully in pediatric patients |

| Potential side effects. All antipsychotics have serious potential side effects that must be recognized, monitored, and managed |

| Potential benefits from using atypical antipsychotics include mood stabilization, treatment of psychotic symptoms, and lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with typical antipsychotics |

| Risk vs benefit. On balance, the potential benefit of these agents outweighs the potential risk for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

Figure: Mean weight gain with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar trials

Weight gain in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder varied among atypical antipsychotics used in 5 recent randomized controlled trials. Treatment duration was 3 weeks with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine and 4 weeks with aripiprazole and ziprasidone. Dosages were olanzapine, 10.4 ± 4.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d or 3 to 6 mg/d; aripiprazole, 10 or 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 400 or 600 mg/d; and ziprasidone, 80 to 160 mg/d.

Source: References 3-7Related resources

- Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation. www.bpkids.org.

- University of Illinois at Chicago Pediatric Mood Disorders Clinic. www.psych.uic.edu/pmdc.

- Ryan Licht Sang Bipolar Foundation. www.ryanlichtsangbipolarfoundation.org.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Metformin • Glucophage

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paliperidone • Invega

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Valproate • Depacon

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch is a consultant to and speaker for AstraZeneca and a consultant to Forest Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Stanley Foundation.

Dr. Strawn has received research support from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Lilly Pilot Research Award).

Dr. Sorter receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati.

1. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Stewart L, et al. Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000011.-

2. Carey B. Risks found for youths in new antipsychotics. The New York Times. September 15, 2008:A17.

3. Pandina G, DelBello M, Kushner S, et al. Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar youth. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

4. Tohen M, Kryzhanovskaya L, Carlson G, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1547-1556.

5. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescents with bipolar mania: a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

6. Wagner K, Nyilas M, Forbes R, et al. Acute efficacy of aripiprazole for the treatment of bipolar I disorder, mixed or manic, in pediatric patients. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

7. DelBello M, Findling RL, Wang P, et al. Safety and efficacy of ziprasidone in pediatric bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 3-8, 2008; Washington, DC.

8. McElduff P, Jaefarnezhad M, Durrington PN. American, British and European recommendations for statins in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease applied to British men studied prospectively. Heart. 2006;92(9):1213-1218.

9. Tsapakis EM, Soldani F, Tondo L, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):10-17.

10. Kowatch R, Findling R, Scheffer R, et al. Placebo controlled trial of divalproex versus lithium for bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

11. DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):305-313.

12. DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1216-1223.

13. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50.

14. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(7):870-886.

15. Becker AL, Epperson CN. Female puberty: clinical implications for the use of prolactin-modulating psychotropics. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):207-220.

16. Correll CU, Penzner JB, Parikh UH, et al. Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):177-206.

17. Correll CU. Effect of hyperprolactinemia during development in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):e24.-

18. Correll CU. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):9-20.

19. Correll CU, Nyilas M, Ashfaque S, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in children (10-17 years) with bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

20. Pandina GJ, Bossie CA, Youssef E, et al. Risperidone improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(2):367-373.

21. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescent with bipolar mania; a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

22. Correll CU, Kane JM. One-year incidence rates of tardive dyskinesia in children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(5):647-656.

23. McDermid SA, Hood J, Bockus S, et al. Adolescents on neuroleptic medication: is this population at risk for tardive dyskinesia? Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43(6):629-631.

24. Kumra S, Jacobsen LK, Lenane M, et al. Case series: spectrum of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders and extrapyramidal side effects in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):221-227.

25. Strawn JR, Keck PE, Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876.

26. Croarkin PE, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric patients: a review of published cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1157-1165.