User login

One AA meeting doesn’t fit all: 6 keys to prescribing 12-step programs

“The meeting was like sitting in a chimney – I practically choked to death.”

“I was the only person there without a tattoo.”

Attending the wrong 12-step meeting can turn off some patients, despite the substance abuse treatment support offered by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and similar programs. Because of the stigma associated with alcohol or drug addiction, most patients are ambivalent at best about attending their first 12-step meetings. Feeling “out of place”—the most common turn-off—can transform this ambivalence into adamant resistance.

Simply advising an addicted patient to “call AA” is tantamount to giving a depressed patient a copy of the Physicians’ Desk Reference and telling him or her to pick an antidepressant. Not all 12-step meetings are alike; 50,000 AA meetings are held every week in the United States (Box 1).1-7 Recognizing the differences between the groups in your area will help you guide your patients to the best match.

In prescribing a 12-step program, consider these six patient factors: socioeconomic status, gender, age, attitude towards spirituality, smoking status, and drug of choice.

More than 50,000 AA meetings, 20,000 NA meetings, and at least 15,000 Alanon/Alateen meetings are held every week in the United States. Other 12-step fellowships that model the AA approach include Gamblers Anonymous, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, Smokers Anonymous, Debtors Anonymous, Dual Recovery Anonymous, and Co-dependence Anonymous.

The combined membership of AA, NA, and Alanon/Alateen is approximately 2 million. To put this in perspective, if the 12-step approach was a religion—as some have proposed1 —it would have more U.S. congregants than Buddhism and Hinduism combined.

Although 12-step therapy has been a central tenet of community-based substance abuse treatment for more than 50 years,2 only recently has it become a focus of clinical research. Two major national multicenter clinical trials3,4 and several important but smaller clinical studies5-7 have found that 12-step-oriented therapies achieve modestly better abstinence rates than the psychotherapies with which they were compared.

Socioeconomic status

Matching patients with meetings according to socioeconomic status is not elitist—it’s pragmatic. Patients generally feel most comfortable and relate most readily at meetings where they feel they have something in common with the other members. For example, when a newly recovering middle-class alcoholic visits an AA group that is frequented by homeless and unemployed alcoholics, chances are that he will become more ambivalent about attending meetings. After all, he was never “that bad.”

A good practice is to give your patients an up-to-date 12-step meeting directory (Box 2). Suggest that they identify the meetings where they think they will feel most comfortable, based on the neighborhoods in which they are held.

Patients in early recovery often are terrified of encountering someone they know at a 12-step meeting. One strategy for patients concerned about protecting their anonymity—as many are—is to attend meetings outside their own neighborhoods but still in areas that match their socioeconomic status. Similarly, referring patients to meetings that are “closed to members only” might reduce their concerns about exposure.

Once a patient has connected with a 12-step program, matching by socioeconomic status becomes less important. Many begin to see similarities between themselves and other addicted individuals from all walks of life. In the beginning, however, similarities attract.

Your patient’s gender

Though women were once a small minority in AA and Narcotics Anonymous (NA), today they make up about one-third of AA’s membership and more than 40% of NA.8 One factor that may have boosted the number of women attending 12-step programs is the increased availability of women-only meetings.

Most cities have women-only meetings, and they generally will be a good place for your female patients to begin. Evidence indicates that gender-specific treatment enhances treatment outcomes.9,10 Women-only meetings tend to be smaller than mixed groups, and the senior members are often particularly willing to welcome newcomers.

Although it is severely frowned upon, the phenomenon of AA or NA members attempting to become romantically or sexually involved with a newcomer is common enough that 12-step members have coined a term for it: “13-stepping.” Newly recovering patients are often emotionally vulnerable and at risk of becoming enmeshed in a potentially destructive relationship. Beginning recovery in gender-specific meetings helps to reduce this risk.

Your patient’s age

A 12-step meeting dominated by people with gray, blue, or no hair can quickly put off teens and young adults in early recovery. Though these meetings with older members are likely to include persons who have achieved long-term and healthy recovery (making such meetings ideal territory for finding a sponsor), finding peers of a similar age is also important.

Meetings intended for young people are identified in 12-step meeting directories, but many of these “young peoples’ ” meetings have a preponderance of members older than 30—quite ancient by a 16-year-old’s standards. Conversely, some generic 12-step meetings might have a cadre of teenagers that attend regularly—at least for a while.

In AA and NA, teens and young adults tend to travel in nomadic packs, linger for a few months, then move on. For this reason, having contacts familiar with the characteristics of local meetings can be invaluable as you try to match a younger patient with a 12-step meeting.

Attitude toward spirituality

One of patients’ most common complaints about 12-step meetings is their surprise at how “religious” the programs are. Insiders are quick to point out that 12-step programs are “spiritual” and not “religious,” but the distinction is moot to patients who are uneasy with this aspect of meetings. The talk about “God as I understand Him,” the opening and closing of meetings with prayers, and the generous adoption of Judeo-Christian practices can rub agnostic, atheistic, and otherwise spiritually indifferent patients the wrong way.

To protect your patients from being blind-sided, review with them some of the spiritual practices employed in 12-step programs before they attend their first meeting:

- Meetings begin with reading the Twelve Steps (Box 3) and other 12-step literature; all readings are peppered with spiritually-loaded words such as “God,” “Higher Power,” “prayer,” and “meditation.”

- Meetings end with a prayer in which the group stands and holds hands (in AA) or links their arms in a huddle (NA). [I advise patients who might find this activity intolerable to duck out to the rest room 5 minutes before the meeting ends.]

- Group leaders typically collect donations by passing the basket.

Certain meetings have a particularly heavy spiritual focus and might be appropriately prescribed for patients hungering for spiritual growth. But for patients who have had toxic encounters with religion or otherwise are ill-at-ease with spirituality or religious matters, starting out at one of the more spiritually hardcore 12-step meetings could be overwhelming. While your 12-step contact person is your best guide in these matters, the following points also apply:

- Meetings listed as “11th Step” or “God as I understand Him” meetings will have a strong spiritual focus.

- Meetings held on Sunday mornings often have the express purpose of focusing on spirituality.

- “Step” meetings generally have a more spiritual focus, as 11 of the 12 steps are aimed at eliciting a “spiritual awakening.”

- “Speaker” or “topic discussion” meetings tend to have a less spiritual focus, though this will vary with the meeting chairperson’s preferences.

- “Beginners” meetings, when available, are intended for new members and devote more time to helping the newcomer understand the 12-step approach to spirituality.

Unless you regularly attend 12-step meetings, it is impossible to know which groups would be the best match for your patients. Here are suggestions for matching your patient’s needs with local 12-step meetings:

- Use fellowship directories. All 12-step fellowships maintain directories of where and when meetings are held and whether meetings are nonsmoking or have other restrictions (e.g., gay-only, women-only). For directories, call local AA and NA fellowships (in the phone book’s white pages).

- Develop a 12-step contact list. Rehabilitation centers often have counselors on staff who are familiar with local 12-step meetings and can recommend those that match your patients’ characteristics. Counselors who are active AA or NA members can be a valuable resource in identifying subtle differences in meetings.

- Locate 12-step meetings for impaired professionals. Special 12-step meetings for nurses, physicians, and pharmacists are held in many cities. For technical reasons, these are not “official”12-step meetings and are not listed in 12-step directories. Times and locations can generally be obtained from local medical societies, impaired-professional programs, or treatment centers.

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Cameto believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Source: Alcoholics Anonymous

AA’s main text, the so-called “Big Book” (its real title is: Alcoholics Anonymous7) has a chapter titled, “We Agnostics.” AA has many long-time members who have found support in the fellowship but never “found God” or a belief in a higher power other than the fellowship itself. These secular 12-step members demonstrate one of the many ironies of AA and NA—that spiritual fellowships can work even for individuals who reject spirituality.

Patients who resist spirituality are advised to “take what you can use” from the fellowship and “leave the rest.” While 12-step members will propose that the newcomer keep an open mind about spirituality, patients should also be assured that a seat is always waiting for them, regardless.

Whether your patient smokes

Most 12-step meetings today are smoke-free, not because of enlightenment within the fellowships but because meetings are usually held in churches, synagogues, and health care facilities where smoking is banned. The perception that attending 12-step meetings can be harmful to your health is out-of-date. Nonetheless, because most meetings have banned smoking, the few in which smoking is allowed are thick with smoke.

In general, 12-step clubhouses are among the holdouts where smoking is allowed during and after meetings. A clubhouse is typically a storefront rented or acquired by AA/NA members where meetings are held around the clock. Given the evidence that quitting smoking may improve overall health,10,11 patients should be encouraged to begin their involvement in smoke-free fellowships, which are identified in 12-step directories.

Your patient’s drug of choice

As its name implies, AA is intended for persons who desire to stop drinking. In practice, however, much of AA’s membership is addicted to more than one substance, and—in some cases—the drug of choice might not be alcohol.

Narcotics Anonymous—contrary to what its name implies—is for individuals addicted to any drug, not just narcotics. Patients generally should be advised to join the fellowship (AA or NA) that best matches their substance use history. There is, however, at least one exception that might best be illustrated with an example:

After I recommended NA meetings to a middle-class nurse addicted to analgesics, she returned for her next appointment quite angry. She attended three different NA meetings, and “all of the members were either heroin or crack cocaine addicts.” It seemed to her that all of them were on probation or parole. She was very uncomfortable throughout the meetings and upset with my recommendation.

In matching patients with meetings, socioeconomic and cultural factors take precedence over biochemistry. At the neuronal level, a nurse addicted to analgesics has a lot in common with a heroin addict, but her ability to relate to another recovering person—particularly in early recovery—may be limited. Arguing with my patient or countering that other nurses were probably at the meetings she attended would not have eased her reluctance to return to NA or helped our therapeutic alliance.

NA meetings are generally attended by individuals addicted to illicit drugs: amphetamines, crack cocaine, cannabis, and heroin. In larger cities, other 12-step fellowships may focus on specific drugs, such as cocaine, but these are rare. Just as individuals addicted to prescription narcotics are a minority in the treatment population, they are also a minority in NA.

For this reason, our prior recommendation—to match patients to meetings based on socioeconomic status—applies. It’s good policy to recommend that patients addicted to prescription medications try both AA and NA meetings and decide where they feel most comfortable.

The third tradition of AA states, “the only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking.” Though a purist might suggest that our analgesics-dependent nurse should join NA, her need to connect culturally with similar persons in recovery argues strongly for her to blend in at open AA meetings. A social drinker who never fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence, she will have a better chance of abstaining from analgesics if she abstains from alcohol as well. For this reason, she should qualify for AA membership because she does, in fact, have “a desire to stop drinking.”

Some professionals addicted to prescription drugs will feel at home in NA meetings, whereas others will react as my patient did. Having access to a 12-step contact person who knows about the demographics of local NA meetings can help you make the best patient/meeting match.

Related resources

- Alcoholics Anonymous. www.alcoholics-anonymous.org

- Narcotics Anonymous. www.na.org

- Alanon-Alateen. www.al-anon.org

1. The Church of God Anonymous (religion of the 12-step movement) http://www.churchofgodanonymous.org/index2.html

2. White W. Slaying the Dragon Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems, 1998.

3. Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;57(6):493-502.

4. Project Match. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Studies Alcohol 1997;58(1):7-29.

5. Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Twelve-step and cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse: A comparison of treatment effectiveness. J Consult Clin Psychology 1997;65:230-40.

6. Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Hayaki J. Testing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: Within treatment and post-treatment findings. J Consult Clin Psychology 2001;69:1007-17.

7. Alcoholics Anonymous (3rd ed). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Service, 1976.

8. Emrick CD, Tonigan SJ, Montgomery H, Little L. Alcoholics Anonymous: what is currently known. In: McCrady BS, Miller WR (eds). Research on Alcoholics Anonymous New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center on Alcohol Studies Publications, 1993:45.

9. Blume S. Addiction in women. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD (eds). Textbook of substance abuse treatment (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999;485-91.

10. Jarvis TJ. Implications of gender for alcohol treatment research: a quantitative and qualitative review. Br J Addiction 1992;87:1249-61.

11. Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Lando HA, Walker RD, Leed-Kelly A. Effect of smoking cessation counseling on recovery from alcoholism: findings from a randomized community intervention trial. Addiction 1998;93:877-87.

12. Burling TA, Marshall GD, Seidner AL. Smoking cessation for substance abuse inpatients. J Subs Abuse 1991;3(3):269-76.

“The meeting was like sitting in a chimney – I practically choked to death.”

“I was the only person there without a tattoo.”

Attending the wrong 12-step meeting can turn off some patients, despite the substance abuse treatment support offered by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and similar programs. Because of the stigma associated with alcohol or drug addiction, most patients are ambivalent at best about attending their first 12-step meetings. Feeling “out of place”—the most common turn-off—can transform this ambivalence into adamant resistance.

Simply advising an addicted patient to “call AA” is tantamount to giving a depressed patient a copy of the Physicians’ Desk Reference and telling him or her to pick an antidepressant. Not all 12-step meetings are alike; 50,000 AA meetings are held every week in the United States (Box 1).1-7 Recognizing the differences between the groups in your area will help you guide your patients to the best match.

In prescribing a 12-step program, consider these six patient factors: socioeconomic status, gender, age, attitude towards spirituality, smoking status, and drug of choice.

More than 50,000 AA meetings, 20,000 NA meetings, and at least 15,000 Alanon/Alateen meetings are held every week in the United States. Other 12-step fellowships that model the AA approach include Gamblers Anonymous, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, Smokers Anonymous, Debtors Anonymous, Dual Recovery Anonymous, and Co-dependence Anonymous.

The combined membership of AA, NA, and Alanon/Alateen is approximately 2 million. To put this in perspective, if the 12-step approach was a religion—as some have proposed1 —it would have more U.S. congregants than Buddhism and Hinduism combined.

Although 12-step therapy has been a central tenet of community-based substance abuse treatment for more than 50 years,2 only recently has it become a focus of clinical research. Two major national multicenter clinical trials3,4 and several important but smaller clinical studies5-7 have found that 12-step-oriented therapies achieve modestly better abstinence rates than the psychotherapies with which they were compared.

Socioeconomic status

Matching patients with meetings according to socioeconomic status is not elitist—it’s pragmatic. Patients generally feel most comfortable and relate most readily at meetings where they feel they have something in common with the other members. For example, when a newly recovering middle-class alcoholic visits an AA group that is frequented by homeless and unemployed alcoholics, chances are that he will become more ambivalent about attending meetings. After all, he was never “that bad.”

A good practice is to give your patients an up-to-date 12-step meeting directory (Box 2). Suggest that they identify the meetings where they think they will feel most comfortable, based on the neighborhoods in which they are held.

Patients in early recovery often are terrified of encountering someone they know at a 12-step meeting. One strategy for patients concerned about protecting their anonymity—as many are—is to attend meetings outside their own neighborhoods but still in areas that match their socioeconomic status. Similarly, referring patients to meetings that are “closed to members only” might reduce their concerns about exposure.

Once a patient has connected with a 12-step program, matching by socioeconomic status becomes less important. Many begin to see similarities between themselves and other addicted individuals from all walks of life. In the beginning, however, similarities attract.

Your patient’s gender

Though women were once a small minority in AA and Narcotics Anonymous (NA), today they make up about one-third of AA’s membership and more than 40% of NA.8 One factor that may have boosted the number of women attending 12-step programs is the increased availability of women-only meetings.

Most cities have women-only meetings, and they generally will be a good place for your female patients to begin. Evidence indicates that gender-specific treatment enhances treatment outcomes.9,10 Women-only meetings tend to be smaller than mixed groups, and the senior members are often particularly willing to welcome newcomers.

Although it is severely frowned upon, the phenomenon of AA or NA members attempting to become romantically or sexually involved with a newcomer is common enough that 12-step members have coined a term for it: “13-stepping.” Newly recovering patients are often emotionally vulnerable and at risk of becoming enmeshed in a potentially destructive relationship. Beginning recovery in gender-specific meetings helps to reduce this risk.

Your patient’s age

A 12-step meeting dominated by people with gray, blue, or no hair can quickly put off teens and young adults in early recovery. Though these meetings with older members are likely to include persons who have achieved long-term and healthy recovery (making such meetings ideal territory for finding a sponsor), finding peers of a similar age is also important.

Meetings intended for young people are identified in 12-step meeting directories, but many of these “young peoples’ ” meetings have a preponderance of members older than 30—quite ancient by a 16-year-old’s standards. Conversely, some generic 12-step meetings might have a cadre of teenagers that attend regularly—at least for a while.

In AA and NA, teens and young adults tend to travel in nomadic packs, linger for a few months, then move on. For this reason, having contacts familiar with the characteristics of local meetings can be invaluable as you try to match a younger patient with a 12-step meeting.

Attitude toward spirituality

One of patients’ most common complaints about 12-step meetings is their surprise at how “religious” the programs are. Insiders are quick to point out that 12-step programs are “spiritual” and not “religious,” but the distinction is moot to patients who are uneasy with this aspect of meetings. The talk about “God as I understand Him,” the opening and closing of meetings with prayers, and the generous adoption of Judeo-Christian practices can rub agnostic, atheistic, and otherwise spiritually indifferent patients the wrong way.

To protect your patients from being blind-sided, review with them some of the spiritual practices employed in 12-step programs before they attend their first meeting:

- Meetings begin with reading the Twelve Steps (Box 3) and other 12-step literature; all readings are peppered with spiritually-loaded words such as “God,” “Higher Power,” “prayer,” and “meditation.”

- Meetings end with a prayer in which the group stands and holds hands (in AA) or links their arms in a huddle (NA). [I advise patients who might find this activity intolerable to duck out to the rest room 5 minutes before the meeting ends.]

- Group leaders typically collect donations by passing the basket.

Certain meetings have a particularly heavy spiritual focus and might be appropriately prescribed for patients hungering for spiritual growth. But for patients who have had toxic encounters with religion or otherwise are ill-at-ease with spirituality or religious matters, starting out at one of the more spiritually hardcore 12-step meetings could be overwhelming. While your 12-step contact person is your best guide in these matters, the following points also apply:

- Meetings listed as “11th Step” or “God as I understand Him” meetings will have a strong spiritual focus.

- Meetings held on Sunday mornings often have the express purpose of focusing on spirituality.

- “Step” meetings generally have a more spiritual focus, as 11 of the 12 steps are aimed at eliciting a “spiritual awakening.”

- “Speaker” or “topic discussion” meetings tend to have a less spiritual focus, though this will vary with the meeting chairperson’s preferences.

- “Beginners” meetings, when available, are intended for new members and devote more time to helping the newcomer understand the 12-step approach to spirituality.

Unless you regularly attend 12-step meetings, it is impossible to know which groups would be the best match for your patients. Here are suggestions for matching your patient’s needs with local 12-step meetings:

- Use fellowship directories. All 12-step fellowships maintain directories of where and when meetings are held and whether meetings are nonsmoking or have other restrictions (e.g., gay-only, women-only). For directories, call local AA and NA fellowships (in the phone book’s white pages).

- Develop a 12-step contact list. Rehabilitation centers often have counselors on staff who are familiar with local 12-step meetings and can recommend those that match your patients’ characteristics. Counselors who are active AA or NA members can be a valuable resource in identifying subtle differences in meetings.

- Locate 12-step meetings for impaired professionals. Special 12-step meetings for nurses, physicians, and pharmacists are held in many cities. For technical reasons, these are not “official”12-step meetings and are not listed in 12-step directories. Times and locations can generally be obtained from local medical societies, impaired-professional programs, or treatment centers.

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Cameto believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Source: Alcoholics Anonymous

AA’s main text, the so-called “Big Book” (its real title is: Alcoholics Anonymous7) has a chapter titled, “We Agnostics.” AA has many long-time members who have found support in the fellowship but never “found God” or a belief in a higher power other than the fellowship itself. These secular 12-step members demonstrate one of the many ironies of AA and NA—that spiritual fellowships can work even for individuals who reject spirituality.

Patients who resist spirituality are advised to “take what you can use” from the fellowship and “leave the rest.” While 12-step members will propose that the newcomer keep an open mind about spirituality, patients should also be assured that a seat is always waiting for them, regardless.

Whether your patient smokes

Most 12-step meetings today are smoke-free, not because of enlightenment within the fellowships but because meetings are usually held in churches, synagogues, and health care facilities where smoking is banned. The perception that attending 12-step meetings can be harmful to your health is out-of-date. Nonetheless, because most meetings have banned smoking, the few in which smoking is allowed are thick with smoke.

In general, 12-step clubhouses are among the holdouts where smoking is allowed during and after meetings. A clubhouse is typically a storefront rented or acquired by AA/NA members where meetings are held around the clock. Given the evidence that quitting smoking may improve overall health,10,11 patients should be encouraged to begin their involvement in smoke-free fellowships, which are identified in 12-step directories.

Your patient’s drug of choice

As its name implies, AA is intended for persons who desire to stop drinking. In practice, however, much of AA’s membership is addicted to more than one substance, and—in some cases—the drug of choice might not be alcohol.

Narcotics Anonymous—contrary to what its name implies—is for individuals addicted to any drug, not just narcotics. Patients generally should be advised to join the fellowship (AA or NA) that best matches their substance use history. There is, however, at least one exception that might best be illustrated with an example:

After I recommended NA meetings to a middle-class nurse addicted to analgesics, she returned for her next appointment quite angry. She attended three different NA meetings, and “all of the members were either heroin or crack cocaine addicts.” It seemed to her that all of them were on probation or parole. She was very uncomfortable throughout the meetings and upset with my recommendation.

In matching patients with meetings, socioeconomic and cultural factors take precedence over biochemistry. At the neuronal level, a nurse addicted to analgesics has a lot in common with a heroin addict, but her ability to relate to another recovering person—particularly in early recovery—may be limited. Arguing with my patient or countering that other nurses were probably at the meetings she attended would not have eased her reluctance to return to NA or helped our therapeutic alliance.

NA meetings are generally attended by individuals addicted to illicit drugs: amphetamines, crack cocaine, cannabis, and heroin. In larger cities, other 12-step fellowships may focus on specific drugs, such as cocaine, but these are rare. Just as individuals addicted to prescription narcotics are a minority in the treatment population, they are also a minority in NA.

For this reason, our prior recommendation—to match patients to meetings based on socioeconomic status—applies. It’s good policy to recommend that patients addicted to prescription medications try both AA and NA meetings and decide where they feel most comfortable.

The third tradition of AA states, “the only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking.” Though a purist might suggest that our analgesics-dependent nurse should join NA, her need to connect culturally with similar persons in recovery argues strongly for her to blend in at open AA meetings. A social drinker who never fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence, she will have a better chance of abstaining from analgesics if she abstains from alcohol as well. For this reason, she should qualify for AA membership because she does, in fact, have “a desire to stop drinking.”

Some professionals addicted to prescription drugs will feel at home in NA meetings, whereas others will react as my patient did. Having access to a 12-step contact person who knows about the demographics of local NA meetings can help you make the best patient/meeting match.

Related resources

- Alcoholics Anonymous. www.alcoholics-anonymous.org

- Narcotics Anonymous. www.na.org

- Alanon-Alateen. www.al-anon.org

“The meeting was like sitting in a chimney – I practically choked to death.”

“I was the only person there without a tattoo.”

Attending the wrong 12-step meeting can turn off some patients, despite the substance abuse treatment support offered by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and similar programs. Because of the stigma associated with alcohol or drug addiction, most patients are ambivalent at best about attending their first 12-step meetings. Feeling “out of place”—the most common turn-off—can transform this ambivalence into adamant resistance.

Simply advising an addicted patient to “call AA” is tantamount to giving a depressed patient a copy of the Physicians’ Desk Reference and telling him or her to pick an antidepressant. Not all 12-step meetings are alike; 50,000 AA meetings are held every week in the United States (Box 1).1-7 Recognizing the differences between the groups in your area will help you guide your patients to the best match.

In prescribing a 12-step program, consider these six patient factors: socioeconomic status, gender, age, attitude towards spirituality, smoking status, and drug of choice.

More than 50,000 AA meetings, 20,000 NA meetings, and at least 15,000 Alanon/Alateen meetings are held every week in the United States. Other 12-step fellowships that model the AA approach include Gamblers Anonymous, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, Smokers Anonymous, Debtors Anonymous, Dual Recovery Anonymous, and Co-dependence Anonymous.

The combined membership of AA, NA, and Alanon/Alateen is approximately 2 million. To put this in perspective, if the 12-step approach was a religion—as some have proposed1 —it would have more U.S. congregants than Buddhism and Hinduism combined.

Although 12-step therapy has been a central tenet of community-based substance abuse treatment for more than 50 years,2 only recently has it become a focus of clinical research. Two major national multicenter clinical trials3,4 and several important but smaller clinical studies5-7 have found that 12-step-oriented therapies achieve modestly better abstinence rates than the psychotherapies with which they were compared.

Socioeconomic status

Matching patients with meetings according to socioeconomic status is not elitist—it’s pragmatic. Patients generally feel most comfortable and relate most readily at meetings where they feel they have something in common with the other members. For example, when a newly recovering middle-class alcoholic visits an AA group that is frequented by homeless and unemployed alcoholics, chances are that he will become more ambivalent about attending meetings. After all, he was never “that bad.”

A good practice is to give your patients an up-to-date 12-step meeting directory (Box 2). Suggest that they identify the meetings where they think they will feel most comfortable, based on the neighborhoods in which they are held.

Patients in early recovery often are terrified of encountering someone they know at a 12-step meeting. One strategy for patients concerned about protecting their anonymity—as many are—is to attend meetings outside their own neighborhoods but still in areas that match their socioeconomic status. Similarly, referring patients to meetings that are “closed to members only” might reduce their concerns about exposure.

Once a patient has connected with a 12-step program, matching by socioeconomic status becomes less important. Many begin to see similarities between themselves and other addicted individuals from all walks of life. In the beginning, however, similarities attract.

Your patient’s gender

Though women were once a small minority in AA and Narcotics Anonymous (NA), today they make up about one-third of AA’s membership and more than 40% of NA.8 One factor that may have boosted the number of women attending 12-step programs is the increased availability of women-only meetings.

Most cities have women-only meetings, and they generally will be a good place for your female patients to begin. Evidence indicates that gender-specific treatment enhances treatment outcomes.9,10 Women-only meetings tend to be smaller than mixed groups, and the senior members are often particularly willing to welcome newcomers.

Although it is severely frowned upon, the phenomenon of AA or NA members attempting to become romantically or sexually involved with a newcomer is common enough that 12-step members have coined a term for it: “13-stepping.” Newly recovering patients are often emotionally vulnerable and at risk of becoming enmeshed in a potentially destructive relationship. Beginning recovery in gender-specific meetings helps to reduce this risk.

Your patient’s age

A 12-step meeting dominated by people with gray, blue, or no hair can quickly put off teens and young adults in early recovery. Though these meetings with older members are likely to include persons who have achieved long-term and healthy recovery (making such meetings ideal territory for finding a sponsor), finding peers of a similar age is also important.

Meetings intended for young people are identified in 12-step meeting directories, but many of these “young peoples’ ” meetings have a preponderance of members older than 30—quite ancient by a 16-year-old’s standards. Conversely, some generic 12-step meetings might have a cadre of teenagers that attend regularly—at least for a while.

In AA and NA, teens and young adults tend to travel in nomadic packs, linger for a few months, then move on. For this reason, having contacts familiar with the characteristics of local meetings can be invaluable as you try to match a younger patient with a 12-step meeting.

Attitude toward spirituality

One of patients’ most common complaints about 12-step meetings is their surprise at how “religious” the programs are. Insiders are quick to point out that 12-step programs are “spiritual” and not “religious,” but the distinction is moot to patients who are uneasy with this aspect of meetings. The talk about “God as I understand Him,” the opening and closing of meetings with prayers, and the generous adoption of Judeo-Christian practices can rub agnostic, atheistic, and otherwise spiritually indifferent patients the wrong way.

To protect your patients from being blind-sided, review with them some of the spiritual practices employed in 12-step programs before they attend their first meeting:

- Meetings begin with reading the Twelve Steps (Box 3) and other 12-step literature; all readings are peppered with spiritually-loaded words such as “God,” “Higher Power,” “prayer,” and “meditation.”

- Meetings end with a prayer in which the group stands and holds hands (in AA) or links their arms in a huddle (NA). [I advise patients who might find this activity intolerable to duck out to the rest room 5 minutes before the meeting ends.]

- Group leaders typically collect donations by passing the basket.

Certain meetings have a particularly heavy spiritual focus and might be appropriately prescribed for patients hungering for spiritual growth. But for patients who have had toxic encounters with religion or otherwise are ill-at-ease with spirituality or religious matters, starting out at one of the more spiritually hardcore 12-step meetings could be overwhelming. While your 12-step contact person is your best guide in these matters, the following points also apply:

- Meetings listed as “11th Step” or “God as I understand Him” meetings will have a strong spiritual focus.

- Meetings held on Sunday mornings often have the express purpose of focusing on spirituality.

- “Step” meetings generally have a more spiritual focus, as 11 of the 12 steps are aimed at eliciting a “spiritual awakening.”

- “Speaker” or “topic discussion” meetings tend to have a less spiritual focus, though this will vary with the meeting chairperson’s preferences.

- “Beginners” meetings, when available, are intended for new members and devote more time to helping the newcomer understand the 12-step approach to spirituality.

Unless you regularly attend 12-step meetings, it is impossible to know which groups would be the best match for your patients. Here are suggestions for matching your patient’s needs with local 12-step meetings:

- Use fellowship directories. All 12-step fellowships maintain directories of where and when meetings are held and whether meetings are nonsmoking or have other restrictions (e.g., gay-only, women-only). For directories, call local AA and NA fellowships (in the phone book’s white pages).

- Develop a 12-step contact list. Rehabilitation centers often have counselors on staff who are familiar with local 12-step meetings and can recommend those that match your patients’ characteristics. Counselors who are active AA or NA members can be a valuable resource in identifying subtle differences in meetings.

- Locate 12-step meetings for impaired professionals. Special 12-step meetings for nurses, physicians, and pharmacists are held in many cities. For technical reasons, these are not “official”12-step meetings and are not listed in 12-step directories. Times and locations can generally be obtained from local medical societies, impaired-professional programs, or treatment centers.

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Cameto believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Source: Alcoholics Anonymous

AA’s main text, the so-called “Big Book” (its real title is: Alcoholics Anonymous7) has a chapter titled, “We Agnostics.” AA has many long-time members who have found support in the fellowship but never “found God” or a belief in a higher power other than the fellowship itself. These secular 12-step members demonstrate one of the many ironies of AA and NA—that spiritual fellowships can work even for individuals who reject spirituality.

Patients who resist spirituality are advised to “take what you can use” from the fellowship and “leave the rest.” While 12-step members will propose that the newcomer keep an open mind about spirituality, patients should also be assured that a seat is always waiting for them, regardless.

Whether your patient smokes

Most 12-step meetings today are smoke-free, not because of enlightenment within the fellowships but because meetings are usually held in churches, synagogues, and health care facilities where smoking is banned. The perception that attending 12-step meetings can be harmful to your health is out-of-date. Nonetheless, because most meetings have banned smoking, the few in which smoking is allowed are thick with smoke.

In general, 12-step clubhouses are among the holdouts where smoking is allowed during and after meetings. A clubhouse is typically a storefront rented or acquired by AA/NA members where meetings are held around the clock. Given the evidence that quitting smoking may improve overall health,10,11 patients should be encouraged to begin their involvement in smoke-free fellowships, which are identified in 12-step directories.

Your patient’s drug of choice

As its name implies, AA is intended for persons who desire to stop drinking. In practice, however, much of AA’s membership is addicted to more than one substance, and—in some cases—the drug of choice might not be alcohol.

Narcotics Anonymous—contrary to what its name implies—is for individuals addicted to any drug, not just narcotics. Patients generally should be advised to join the fellowship (AA or NA) that best matches their substance use history. There is, however, at least one exception that might best be illustrated with an example:

After I recommended NA meetings to a middle-class nurse addicted to analgesics, she returned for her next appointment quite angry. She attended three different NA meetings, and “all of the members were either heroin or crack cocaine addicts.” It seemed to her that all of them were on probation or parole. She was very uncomfortable throughout the meetings and upset with my recommendation.

In matching patients with meetings, socioeconomic and cultural factors take precedence over biochemistry. At the neuronal level, a nurse addicted to analgesics has a lot in common with a heroin addict, but her ability to relate to another recovering person—particularly in early recovery—may be limited. Arguing with my patient or countering that other nurses were probably at the meetings she attended would not have eased her reluctance to return to NA or helped our therapeutic alliance.

NA meetings are generally attended by individuals addicted to illicit drugs: amphetamines, crack cocaine, cannabis, and heroin. In larger cities, other 12-step fellowships may focus on specific drugs, such as cocaine, but these are rare. Just as individuals addicted to prescription narcotics are a minority in the treatment population, they are also a minority in NA.

For this reason, our prior recommendation—to match patients to meetings based on socioeconomic status—applies. It’s good policy to recommend that patients addicted to prescription medications try both AA and NA meetings and decide where they feel most comfortable.

The third tradition of AA states, “the only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking.” Though a purist might suggest that our analgesics-dependent nurse should join NA, her need to connect culturally with similar persons in recovery argues strongly for her to blend in at open AA meetings. A social drinker who never fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence, she will have a better chance of abstaining from analgesics if she abstains from alcohol as well. For this reason, she should qualify for AA membership because she does, in fact, have “a desire to stop drinking.”

Some professionals addicted to prescription drugs will feel at home in NA meetings, whereas others will react as my patient did. Having access to a 12-step contact person who knows about the demographics of local NA meetings can help you make the best patient/meeting match.

Related resources

- Alcoholics Anonymous. www.alcoholics-anonymous.org

- Narcotics Anonymous. www.na.org

- Alanon-Alateen. www.al-anon.org

1. The Church of God Anonymous (religion of the 12-step movement) http://www.churchofgodanonymous.org/index2.html

2. White W. Slaying the Dragon Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems, 1998.

3. Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;57(6):493-502.

4. Project Match. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Studies Alcohol 1997;58(1):7-29.

5. Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Twelve-step and cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse: A comparison of treatment effectiveness. J Consult Clin Psychology 1997;65:230-40.

6. Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Hayaki J. Testing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: Within treatment and post-treatment findings. J Consult Clin Psychology 2001;69:1007-17.

7. Alcoholics Anonymous (3rd ed). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Service, 1976.

8. Emrick CD, Tonigan SJ, Montgomery H, Little L. Alcoholics Anonymous: what is currently known. In: McCrady BS, Miller WR (eds). Research on Alcoholics Anonymous New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center on Alcohol Studies Publications, 1993:45.

9. Blume S. Addiction in women. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD (eds). Textbook of substance abuse treatment (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999;485-91.

10. Jarvis TJ. Implications of gender for alcohol treatment research: a quantitative and qualitative review. Br J Addiction 1992;87:1249-61.

11. Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Lando HA, Walker RD, Leed-Kelly A. Effect of smoking cessation counseling on recovery from alcoholism: findings from a randomized community intervention trial. Addiction 1998;93:877-87.

12. Burling TA, Marshall GD, Seidner AL. Smoking cessation for substance abuse inpatients. J Subs Abuse 1991;3(3):269-76.

1. The Church of God Anonymous (religion of the 12-step movement) http://www.churchofgodanonymous.org/index2.html

2. White W. Slaying the Dragon Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems, 1998.

3. Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;57(6):493-502.

4. Project Match. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Studies Alcohol 1997;58(1):7-29.

5. Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Twelve-step and cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse: A comparison of treatment effectiveness. J Consult Clin Psychology 1997;65:230-40.

6. Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Hayaki J. Testing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: Within treatment and post-treatment findings. J Consult Clin Psychology 2001;69:1007-17.

7. Alcoholics Anonymous (3rd ed). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Service, 1976.

8. Emrick CD, Tonigan SJ, Montgomery H, Little L. Alcoholics Anonymous: what is currently known. In: McCrady BS, Miller WR (eds). Research on Alcoholics Anonymous New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center on Alcohol Studies Publications, 1993:45.

9. Blume S. Addiction in women. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD (eds). Textbook of substance abuse treatment (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999;485-91.

10. Jarvis TJ. Implications of gender for alcohol treatment research: a quantitative and qualitative review. Br J Addiction 1992;87:1249-61.

11. Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Lando HA, Walker RD, Leed-Kelly A. Effect of smoking cessation counseling on recovery from alcoholism: findings from a randomized community intervention trial. Addiction 1998;93:877-87.

12. Burling TA, Marshall GD, Seidner AL. Smoking cessation for substance abuse inpatients. J Subs Abuse 1991;3(3):269-76.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: How to treat them most effectively

Negative symptoms are the major contributor to low function levels and debilitation in most patients with schizophrenia. Poorly motivated patients cannot function adequately at school or work. Relationships with family and friends decay in the face of unresponsive affect and inattention to social cues. Personal interests yield to the dampening influences of anhedonia, apathy, and inattention.

Yet because active psychosis is the most common cause of hospital admission, a primary goal of treatment—and sometimes the only objective of pharmacologic treatment—is to eliminate or reduce positive symptoms. And although controlling positive symptoms is remarkably effective in reducing hospitalizations, patients’ functional capacity improves only minimally as psychosis abates. Even with optimal antipsychotic treatment, negative symptoms tend to persist.

For psychiatrists, the three major challenges of schizophrenia’s negative symptoms are their modest therapeutic response, pervasiveness, and diminution of patients’ quality of life. To help you manage negative symptoms, we suggest the following approach to their assessment and treatment.

Importance of negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by positive, negative, cognitive, and mood symptoms. The relative severity of these four pathologic domains varies from case to case and within the same individual over time. Though related, these domains have distinct underlying mechanisms and are differentially related to functional capacity and quality of life. They also show different patterns of response to treatment. Whereas positive symptoms refer to new psychological experiences outside the range of normal (e.g., delusions, hallucinations, suspiciousness, disorganized thinking), negative symptoms represent loss of normal function.

Negative symptoms include blunting of affect, poverty of speech and thought, apathy, anhedonia, reduced social drive, loss of motivation, lack of social interest, and inattention to social or cognitive input. These symptoms have devastating consequences on patients’ lives, and only modest progress has been made in treating them effectively.

From negative to positive. Early investigators1,2 considered negative symptoms to represent the fundamental defect of schizophrenia. Over the years, however, the importance of negative symptoms was progressively downplayed. Positive symptoms were increasingly emphasized because:

- positive symptoms have a more dramatic and easily recognized presentation

- negative symptoms are more difficult to reliably define and document

- antipsychotics, which revolutionized schizophrenia treatment, produce their most dramatic improvement in positive symptoms.

Renewed interest. The almost universal presence and relative persistence of negative symptoms, and the fact that they represent the most debilitating and refractory aspect of schizophrenic psychopathology, make them difficult to ignore. Consequently, interest in negative symptoms resurged in the 1980s-90s, with intense efforts to better understand them and treat them more effectively.3-5

Table

SCHIZOPHRENIA’S NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY COMPONENTS

| Primary Associated with positive symptoms Deficit or primary enduring symptoms (premorbid and deteriorative) |

| Secondary Associated with extrapyramidal symptoms, depression, or environmental deprivation |

| Source: Adapted from DeQuardo JR, Tandon R. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32 (3-4):229-42. |

Negative symptoms are now better (but still incompletely) understood, and their treatment has improved but is still inadequate. Because intense effort yielded only modest success, researchers and clinicians have again begun to pay less attention to negative symptoms and shifted their focus to cognition in schizophrenia. Negative symptoms remain relevant, however, because they constitute the main barrier to a better quality of life for patients with schizophrenia.

Assessment for negative symptoms

The four major clinical subgroups of negative symptoms are affective, communicative, conational, and relational.

Affective. Blunted affect—including deficits in facial expression, eye contact, gestures, and voice pattern—is perhaps the most conspicuous negative symptom. In mild form, gestures may seem artificial or mechanical, and the voice is stilted or lacks normal inflection. Patients with severe blunted affect may appear devoid of facial expression or communicative gestures. They may sit impassively with little spontaneous movement, speak in a monotone, and gaze blankly in no particular direction.

Even when conversation becomes emotional, the patient’s affect does not adjust appropriately to reflect his or her feelings. Nor does the patient display even a basic level of understanding or responsiveness that typically characterize casual human interactions. The ability to experience pleasure (anhedonia) and sense of caring (apathy) are also reduced.

Communicative. The patient’s speech may be reduced in quantity (poverty of speech) and information (poverty of content of speech). In mild forms of impoverished speech (alogia), the patient makes brief, unelaborated statements; in the more severe form, the patient can be virtually mute. Whatever speech is present tends to be vague and overly generalized. Periods of silence may occur, either before the patient answers a question (increased latency) or in the midst of a response (blocking).

Conational. The patient may show a lack of drive or goal-directed behavior (avolition). Personal grooming may be poor. Physical activity may be limited. Patients typically have great difficulty following a work schedule or hospital ward routine. They fail to initiate activities, participate grudgingly, and require frequent direction and encouragement.

Continue to: Relational

Relational. Interest in social activities and relationships is reduced (asociality). Even enjoyable and recreational activities are neglected. Interpersonal relations may be of little interest. Friendships become rare and shallow, with little sharing of intimacy. Contacts with family are neglected. Sexual interest declines. As symptoms progress, patients become increasingly isolated.

Primary and secondary symptoms

Negative symptoms are an intrinsic component of schizophrenic psychopathology, and they can also be caused by secondary factors (Table).6,7 Distinguishing between primary and secondary causes of negative symptoms can help you select appropriate treatment in specific clinical situations.

Primary symptoms. From a longitudinal perspective, the three major components of primary negative symptoms are:

- premorbid negative symptoms (present prior to psychosis onset and associated with poor premorbid functioning)

- psychotic-phase, nonenduring negative symptoms that fluctuate with positive symptoms around periods of psychotic exacerbation

- deteriorative negative symptoms that intensify following each psychotic exacerbation and reflect a decline from premorbid levels of functioning.

Though little can be done to treat the premorbid component, psychotic-phase negative symptoms improve along with positive symptoms (although more slowly).8,9 Therefore, the best strategy for managing negative symptoms is to treat positive symptoms more effectively. Although there is no specific treatment for deteriorative negative symptoms, the severity of this component appears to be related to the “toxicity of psychosis” and can be reduced by early, effective antipsychotic treatment.10,11

Secondary negative symptoms occur in association with (and presumably are caused by) factors such as depression, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and environmental deprivation. Secondary negative symptoms usually respond to treatment of the underlying cause.

Assessment

Symptom severity. Assessing the severity of a patient’s negative symptoms on an ongoing basis is a most important first step towards optimal treatment:

- Our objective is to improve patients’ function and quality of life, and negative symptoms compromise both of these more than any other factor.

- Ongoing assessment can track whether prescribed treatments are improving or worsening a patient’s symptoms.

Tools to assess the severity of negative symptoms include the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS).12 The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)13 measures them exclusively, and others such as the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS)14 attempt to classify them into subgroups.

Discussing these instruments is beyond the scope of this article, but they differ greatly in their approach to assessing negative symptoms. Instead of using cumbersome assessment instruments, however, we recommend that you focus on two to four of a patient’s “target” symptoms or behaviors and note their severity on an ongoing basis.

Contributing factors. Determining the overall contribution of different factors to a patient’s negative symptoms allows us to target treatments. Sorting out these relative factors can be difficult, however. For example:

- In a patient on antipsychotic treatment who is experiencing psychotic symptoms (eg, persecutory delusions), depressive symptoms, and prominent negative symptoms, the clinician can only guess whether the negative symptoms are primary or secondary.

- In a patient who is socially withdrawn and delusional, withdrawal may be secondary to delusions or may represent a primary negative symptom.

- In a patient on typical antipsychotics, a flat affect may be caused by antipsychotic-induced EPS or it may be a primary negative symptom.

- A disorganized patient with schizophrenia and depression is often unable to convey his or her feelings coherently, so that negative symptoms secondary to affective disturbance may often be mistaken as primary.

Even in research settings, the distinction between primary and secondary symptoms is quite unreliable; nevertheless, it is of great clinical importance. Two strategies may be helpful:

- Consider whether symptoms are specific to the presumed etiology, such as guilt and sadness in depression or cogwheeling and tremor in EPS.

- Treat empirically, and monitor whether negative symptoms improve. If they improve with antidepressant treatment, for example, then depression was the presumable cause. If they improve with anticholinergics, they were presumably secondary to EPS.

Treatment

Negative symptoms are generally viewed as treatment-resistant, but evidence suggests that they do respond to pharmacologic and social interventions (Box). Most responsive to treatment are negative symptoms that occur in association with positive symptoms (psychotic-phase) and secondary negative symptoms caused by neuroleptic medication, depression, or lack of stimulation.

The most effective treatment for secondary symptoms is to target the underlying cause. Neuroleptic-induced akinesia may respond to anticholinergic agents, reduction in antipsychotic dose, or a change in antipsychotic. Using one of the newer-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or ziprasidone) may prevent EPS.

Apsychosocial approach to schizophrenia builds on relationships between the patient and others and may involve social skills training, vocational rehabilitation, and psychotherapy. Activity-oriented therapies appear to be significantly more effective than verbal therapies.

Goals of psychosocial therapy:

- set realistic expectations for the patient

- stay active in treatment in the face of a protracted illness

- create a benign and supportive environment for the patient and caregivers.

Social skills training, designed to help the patient correctly perceive and respond to social situations, is the most widely studied and applied psychosocial intervention. The training is similar to that used in educational settings but focuses on remedying social rather than academic deficits. In schizophrenia, skills training programs address living skills, communication, conflict resolution, vocational skills, etc.

In early studies of social skills training, patients and their families described enhanced social adjustment, and hospitalization rates improved. More recent studies have confirmed improved social adjustment and relapse rates but suggest that overall symptom improvement is modest.

Continue to: Comorbid depression

Comorbid depression may require adding an antidepressant, or it may respond directly to an antipsychotic. Lack of stimulation is best handled by placing the patient in a more appropriately stimulating (but not overstimulating) and supportive environment. Nonenduring primary or psychotic-phase negative symptoms respond to effective antipsychotic treatment of the positive symptoms.

Atypical antipsychotics. Conventional antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, chlorpromazine) clearly offer some benefit in treating negative symptoms, but they have a much greater effect on positive symptoms.15 Using higher-than-appropriate doses diminishes their effect on negative symptoms and may result in severe EPS.

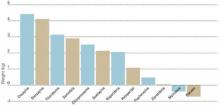

Two-thirds of the approximately 35 studies comparing conventional and atypical antipsychotics in treating negative symptoms have found atypicals to be significantly more effective (regardless of which atypical was used). In general, atypical antipsychotics improve negative symptoms by about 25%, compared with 10 to 15% improvement with conventional agents.16,17

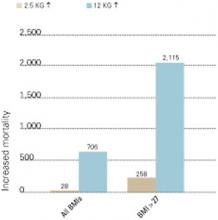

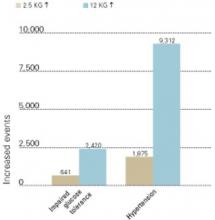

Much of the greater benefit with atypicals appears to be related to their at least equivalent ability to improve positive symptoms without causing EPS. Consequently, the key to improved patient outcomes is appropriate dosing of atypical antipsychotics that reduces positive symptoms optimally without EPS and without the need for an anticholinergic (Figure).

Whether the greater improvement with atypical agents implies an improvement in primary versus secondary negative symptoms is academic.18 From the patient’s perspective, the greater reduction in negative symptoms is meaningful, regardless of why it occurs.

Other medications. Secondary negative symptoms are most effectively treated with medications directed at the primary etiology. For EPS, change the antipsychotic, reduce the dosage, or add an anticholinergic. For depression, try an antidepressant (preferably a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor). If a likely contributing factor can be identified, then initiate specific treatment.

Figure

ANTIPSYCHOTICS IMPROVE NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS THROUGH THEIR EFFECT ON PSYCHOSIS

Source: Adapted from Tandon et al. J Psychiatric Res. 1993;27:341-347.

Antipsychotics improve negative symptoms through their effect on positive (psychotic) symptoms, but they do not affect secondary components—such as environmental deprivation and depression—or the primary components of deterioration and premorbid symptoms. Typical and atypical antipsychotics have similar effects on positive symptoms, but atypical antipsychotics carry a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects.

Empiric therapy—trying one agent and then another in an effort to reduce negative symptoms—is appropriate if done systematically and sequentially. Medications that are found not to be helpful should be discontinued. Electroconvulsive therapy is not effective in treating negative symptoms.

Related resources

- Greden JF, Tandon R (eds). Negative schizophrenic symptoms: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1991.

- Keefe RSE, McEvoy JP (eds). Negative symptom and cognitive deficit treatment response in schizophrenia. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2001.

Drug brand names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia. Translated by Barclay RM, Robertson GM. Edinburgh: E&S Livingstone; 1919.

2. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Translated by Zinkin H. New York: International Universities Press; 1911.

3. Crow TJ. Molecular pathology of schizophrenia: More than one disease process. Br Med J. 1980;280:66-68.

4. Andreasen NC. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: definition and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:784-788.

5. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Alphs LD. Treatment of negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bull. 1985;11:440-452.

6. Carpenter WT, Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AMI. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:578-583.

7. DeQuardo JR, Tandon R. Do atypical antipsychotic medications favorably alter the long-term course of schizophrenia? J Psychiatric Res. 1998;32:229-242.

8. Tandon R, Greden JF. Cholinergic hyperactivity and negative schizophrenic symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:745-753.

9. Tandon R, et al. Covariance of positive and negative symptoms during neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia: a replication. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34(7):495-497.

10. Tandon R, Milner K, Jibson MD. Antipsychotics from theory to practice: integrating clinical and basic data. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 8):21-28.

11. Jibson MD, Tandon R. Treatment of schizophrenia. Psych Clin North Am Annual of Drug Therapy. 2000;7:83-113.

12. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS). Schizophrenia Bull. 1987;13:261-276.

13. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1983.

14. Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT, Jr. The Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;30(2):119-124.

15. Meltzer HY, Sommers AA, Luchins DJ. The effect of neuroleptics and other psychotropic drugs on negative symptoms in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6:329-338.

16. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

17. Tandon R, Goldman R, DeQuardo JR, et al. Positive and negative symptoms covary during clozapine treatment in schizophrenia. J Psychiatric Res. 1993;27:341-347.

18. Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Effect of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(1):20-26.

Negative symptoms are the major contributor to low function levels and debilitation in most patients with schizophrenia. Poorly motivated patients cannot function adequately at school or work. Relationships with family and friends decay in the face of unresponsive affect and inattention to social cues. Personal interests yield to the dampening influences of anhedonia, apathy, and inattention.

Yet because active psychosis is the most common cause of hospital admission, a primary goal of treatment—and sometimes the only objective of pharmacologic treatment—is to eliminate or reduce positive symptoms. And although controlling positive symptoms is remarkably effective in reducing hospitalizations, patients’ functional capacity improves only minimally as psychosis abates. Even with optimal antipsychotic treatment, negative symptoms tend to persist.

For psychiatrists, the three major challenges of schizophrenia’s negative symptoms are their modest therapeutic response, pervasiveness, and diminution of patients’ quality of life. To help you manage negative symptoms, we suggest the following approach to their assessment and treatment.

Importance of negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by positive, negative, cognitive, and mood symptoms. The relative severity of these four pathologic domains varies from case to case and within the same individual over time. Though related, these domains have distinct underlying mechanisms and are differentially related to functional capacity and quality of life. They also show different patterns of response to treatment. Whereas positive symptoms refer to new psychological experiences outside the range of normal (e.g., delusions, hallucinations, suspiciousness, disorganized thinking), negative symptoms represent loss of normal function.

Negative symptoms include blunting of affect, poverty of speech and thought, apathy, anhedonia, reduced social drive, loss of motivation, lack of social interest, and inattention to social or cognitive input. These symptoms have devastating consequences on patients’ lives, and only modest progress has been made in treating them effectively.

From negative to positive. Early investigators1,2 considered negative symptoms to represent the fundamental defect of schizophrenia. Over the years, however, the importance of negative symptoms was progressively downplayed. Positive symptoms were increasingly emphasized because:

- positive symptoms have a more dramatic and easily recognized presentation

- negative symptoms are more difficult to reliably define and document

- antipsychotics, which revolutionized schizophrenia treatment, produce their most dramatic improvement in positive symptoms.

Renewed interest. The almost universal presence and relative persistence of negative symptoms, and the fact that they represent the most debilitating and refractory aspect of schizophrenic psychopathology, make them difficult to ignore. Consequently, interest in negative symptoms resurged in the 1980s-90s, with intense efforts to better understand them and treat them more effectively.3-5

Table

SCHIZOPHRENIA’S NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY COMPONENTS

| Primary Associated with positive symptoms Deficit or primary enduring symptoms (premorbid and deteriorative) |

| Secondary Associated with extrapyramidal symptoms, depression, or environmental deprivation |

| Source: Adapted from DeQuardo JR, Tandon R. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32 (3-4):229-42. |

Negative symptoms are now better (but still incompletely) understood, and their treatment has improved but is still inadequate. Because intense effort yielded only modest success, researchers and clinicians have again begun to pay less attention to negative symptoms and shifted their focus to cognition in schizophrenia. Negative symptoms remain relevant, however, because they constitute the main barrier to a better quality of life for patients with schizophrenia.

Assessment for negative symptoms

The four major clinical subgroups of negative symptoms are affective, communicative, conational, and relational.

Affective. Blunted affect—including deficits in facial expression, eye contact, gestures, and voice pattern—is perhaps the most conspicuous negative symptom. In mild form, gestures may seem artificial or mechanical, and the voice is stilted or lacks normal inflection. Patients with severe blunted affect may appear devoid of facial expression or communicative gestures. They may sit impassively with little spontaneous movement, speak in a monotone, and gaze blankly in no particular direction.

Even when conversation becomes emotional, the patient’s affect does not adjust appropriately to reflect his or her feelings. Nor does the patient display even a basic level of understanding or responsiveness that typically characterize casual human interactions. The ability to experience pleasure (anhedonia) and sense of caring (apathy) are also reduced.

Communicative. The patient’s speech may be reduced in quantity (poverty of speech) and information (poverty of content of speech). In mild forms of impoverished speech (alogia), the patient makes brief, unelaborated statements; in the more severe form, the patient can be virtually mute. Whatever speech is present tends to be vague and overly generalized. Periods of silence may occur, either before the patient answers a question (increased latency) or in the midst of a response (blocking).

Conational. The patient may show a lack of drive or goal-directed behavior (avolition). Personal grooming may be poor. Physical activity may be limited. Patients typically have great difficulty following a work schedule or hospital ward routine. They fail to initiate activities, participate grudgingly, and require frequent direction and encouragement.

Continue to: Relational

Relational. Interest in social activities and relationships is reduced (asociality). Even enjoyable and recreational activities are neglected. Interpersonal relations may be of little interest. Friendships become rare and shallow, with little sharing of intimacy. Contacts with family are neglected. Sexual interest declines. As symptoms progress, patients become increasingly isolated.

Primary and secondary symptoms

Negative symptoms are an intrinsic component of schizophrenic psychopathology, and they can also be caused by secondary factors (Table).6,7 Distinguishing between primary and secondary causes of negative symptoms can help you select appropriate treatment in specific clinical situations.

Primary symptoms. From a longitudinal perspective, the three major components of primary negative symptoms are:

- premorbid negative symptoms (present prior to psychosis onset and associated with poor premorbid functioning)

- psychotic-phase, nonenduring negative symptoms that fluctuate with positive symptoms around periods of psychotic exacerbation

- deteriorative negative symptoms that intensify following each psychotic exacerbation and reflect a decline from premorbid levels of functioning.

Though little can be done to treat the premorbid component, psychotic-phase negative symptoms improve along with positive symptoms (although more slowly).8,9 Therefore, the best strategy for managing negative symptoms is to treat positive symptoms more effectively. Although there is no specific treatment for deteriorative negative symptoms, the severity of this component appears to be related to the “toxicity of psychosis” and can be reduced by early, effective antipsychotic treatment.10,11

Secondary negative symptoms occur in association with (and presumably are caused by) factors such as depression, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and environmental deprivation. Secondary negative symptoms usually respond to treatment of the underlying cause.

Assessment

Symptom severity. Assessing the severity of a patient’s negative symptoms on an ongoing basis is a most important first step towards optimal treatment: