User login

Being “Puzzled” as the First Step to Diagnosis

A 43-year-old Hispanic man has a very itchy rash on his left leg. It manifested within a few weeks of the patient starting a new job, one that involved working more hours than he had previously and on rotating shifts, which interfered with his sleep schedule.

For several years, he tried using different products—mostly OTC creams—on it, with no success. Increasingly annoyed by the rash, he finally consulted his family physician, who prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone cream. This helped a bit, but over time, the rash steadily worsened, and his primary care provider referred him to dermatology.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy, with no history of atopy. He takes no prescription medications. He admits finding it difficult to refrain from scratching his legs.

EXAMINATION

There are large, slightly purplish, hypertrophic papulosquamous plaques of up to 8 cm on both anterior tibial areas. His arms, trunk, and wrists are rash-free, and his oral mucosal surfaces show no obvious signs of disease.

Punch biopsy shows a hypertrophic epidermis. There is marked obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by a dense bandlike layer of lymphocytic infiltrate, associated with vacuolar change and necrotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic clinical and histologic picture of a dermatosis commonly seen in dermatology offices: lichen planus (LP). As is often the case, by the time the patient gets to dermatology, the clinical picture can be confused and atypical. But there is much to learn from such a case.

LP is the prototypical interface lichenoid dermatitis, which can be depended on to present in certain identifiable ways. In this case, what suggested this diagnosis was the word “puzzling.” It’s the perfect example of the intuitive, somewhat subjective side of dermatologic diagnosis: When I see a condition that baffles me momentarily, my puzzled reaction becomes meaningful because the word puzzling starts with a “p.” Lichen planus has long been associated with an extremely useful mnemonic device known as “The Ps.” Besides puzzling, it can stand for purple, plaquish, polygonal (ie, not round), prurtitic, papular, penile (LP has a predilection for this area), and planar (ie, flat-topped).

But it’s the “puzzling” aspect that unlocks the entrance to “The Ps,” and that in turn leads to consideration of this diagnosis. In this case, LP was not totally obvious, but a biopsy confirmed my clinical suspicions by demonstrating the classic findings associated with it.

An LP-like eruption can be provoked by drugs, such as the antimalarials, gold compounds, and penicillamine. It has also been associated with hepatitis C. But in my experience, the most common trigger appears to be stress, since it’s a rare case that doesn’t involve some. (I’ll happily concede that this is my opinion and not established fact.)

This patient’s LP demonstrated two common variants: For one, the darker the patient’s skin, the deeper the purple color of the LP—sometimes to the point of obscuring the diagnosis.

As if that were not enough to confuse the examiner, there was an element of lichen simplex chronicus (LSC; also known as neurodermatitis), which instigates the “itch-scratch-itch” cycle. By its nature, LSC tends to hyperpigmentation (brown). By definition, it involves hypertrophy of the epidermis secondary to scratching. But there is always a primary cause; sometimes mere dry skin will trigger it, or insect bites, eczema, or even psoriasis. This confuses the issue, but the biopsy will establish the true basis for the patient’s condition.

The more common presentation of LP is that of a collection of flat-topped (“planar”), pruritic, purplish papules on the volar wrist, ankles, and sacral area. The surfaces of these lesions often demonstrate a faintly white, shiny surface. LP can also appear on oral mucosal surfaces, where it has a totally different, lacy-white look. In these areas, it tends to burn and not itch. LP appears to have a predilection for the penile glans, where it presents as an annular purplish plaque that sits astride the proximal glans, spilling over onto the coronal area.

LP can present as a widespread generalized eruption mimicking granuloma annulare and secondary syphilis. The differential for simple, classic LP includes psoriasis, granuloma annulare and pityriasis rosea.

Treatment of LP is with topical steroid creams or ointments, tailored in terms of strength to the area of involvement. For example, a class II or III corticosteroid would be used on areas with thicker skin and a class IV or V on thinner skin. Stubborn, solitary plaques can be treated with intralesional steroid injection (2.5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone solution).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is common and typically presents on the volar wrists, dorsal ankles, and sacrum.

• In a minority of cases, LP can present on the legs as a hypertrophic, plaquish condition with secondary features of lichen simplex chronicus.

• A mnemonic device (“The Ps”) describes LP: papular, pruritic, purple, planar, polygonal, plaquish, and (perhaps most importantly) “puzzling.”

• LP can present as an annular plaque on the penile glans.

• LP has a pathognomic histologic picture on biopsy.

A 43-year-old Hispanic man has a very itchy rash on his left leg. It manifested within a few weeks of the patient starting a new job, one that involved working more hours than he had previously and on rotating shifts, which interfered with his sleep schedule.

For several years, he tried using different products—mostly OTC creams—on it, with no success. Increasingly annoyed by the rash, he finally consulted his family physician, who prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone cream. This helped a bit, but over time, the rash steadily worsened, and his primary care provider referred him to dermatology.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy, with no history of atopy. He takes no prescription medications. He admits finding it difficult to refrain from scratching his legs.

EXAMINATION

There are large, slightly purplish, hypertrophic papulosquamous plaques of up to 8 cm on both anterior tibial areas. His arms, trunk, and wrists are rash-free, and his oral mucosal surfaces show no obvious signs of disease.

Punch biopsy shows a hypertrophic epidermis. There is marked obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by a dense bandlike layer of lymphocytic infiltrate, associated with vacuolar change and necrotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic clinical and histologic picture of a dermatosis commonly seen in dermatology offices: lichen planus (LP). As is often the case, by the time the patient gets to dermatology, the clinical picture can be confused and atypical. But there is much to learn from such a case.

LP is the prototypical interface lichenoid dermatitis, which can be depended on to present in certain identifiable ways. In this case, what suggested this diagnosis was the word “puzzling.” It’s the perfect example of the intuitive, somewhat subjective side of dermatologic diagnosis: When I see a condition that baffles me momentarily, my puzzled reaction becomes meaningful because the word puzzling starts with a “p.” Lichen planus has long been associated with an extremely useful mnemonic device known as “The Ps.” Besides puzzling, it can stand for purple, plaquish, polygonal (ie, not round), prurtitic, papular, penile (LP has a predilection for this area), and planar (ie, flat-topped).

But it’s the “puzzling” aspect that unlocks the entrance to “The Ps,” and that in turn leads to consideration of this diagnosis. In this case, LP was not totally obvious, but a biopsy confirmed my clinical suspicions by demonstrating the classic findings associated with it.

An LP-like eruption can be provoked by drugs, such as the antimalarials, gold compounds, and penicillamine. It has also been associated with hepatitis C. But in my experience, the most common trigger appears to be stress, since it’s a rare case that doesn’t involve some. (I’ll happily concede that this is my opinion and not established fact.)

This patient’s LP demonstrated two common variants: For one, the darker the patient’s skin, the deeper the purple color of the LP—sometimes to the point of obscuring the diagnosis.

As if that were not enough to confuse the examiner, there was an element of lichen simplex chronicus (LSC; also known as neurodermatitis), which instigates the “itch-scratch-itch” cycle. By its nature, LSC tends to hyperpigmentation (brown). By definition, it involves hypertrophy of the epidermis secondary to scratching. But there is always a primary cause; sometimes mere dry skin will trigger it, or insect bites, eczema, or even psoriasis. This confuses the issue, but the biopsy will establish the true basis for the patient’s condition.

The more common presentation of LP is that of a collection of flat-topped (“planar”), pruritic, purplish papules on the volar wrist, ankles, and sacral area. The surfaces of these lesions often demonstrate a faintly white, shiny surface. LP can also appear on oral mucosal surfaces, where it has a totally different, lacy-white look. In these areas, it tends to burn and not itch. LP appears to have a predilection for the penile glans, where it presents as an annular purplish plaque that sits astride the proximal glans, spilling over onto the coronal area.

LP can present as a widespread generalized eruption mimicking granuloma annulare and secondary syphilis. The differential for simple, classic LP includes psoriasis, granuloma annulare and pityriasis rosea.

Treatment of LP is with topical steroid creams or ointments, tailored in terms of strength to the area of involvement. For example, a class II or III corticosteroid would be used on areas with thicker skin and a class IV or V on thinner skin. Stubborn, solitary plaques can be treated with intralesional steroid injection (2.5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone solution).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is common and typically presents on the volar wrists, dorsal ankles, and sacrum.

• In a minority of cases, LP can present on the legs as a hypertrophic, plaquish condition with secondary features of lichen simplex chronicus.

• A mnemonic device (“The Ps”) describes LP: papular, pruritic, purple, planar, polygonal, plaquish, and (perhaps most importantly) “puzzling.”

• LP can present as an annular plaque on the penile glans.

• LP has a pathognomic histologic picture on biopsy.

A 43-year-old Hispanic man has a very itchy rash on his left leg. It manifested within a few weeks of the patient starting a new job, one that involved working more hours than he had previously and on rotating shifts, which interfered with his sleep schedule.

For several years, he tried using different products—mostly OTC creams—on it, with no success. Increasingly annoyed by the rash, he finally consulted his family physician, who prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone cream. This helped a bit, but over time, the rash steadily worsened, and his primary care provider referred him to dermatology.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy, with no history of atopy. He takes no prescription medications. He admits finding it difficult to refrain from scratching his legs.

EXAMINATION

There are large, slightly purplish, hypertrophic papulosquamous plaques of up to 8 cm on both anterior tibial areas. His arms, trunk, and wrists are rash-free, and his oral mucosal surfaces show no obvious signs of disease.

Punch biopsy shows a hypertrophic epidermis. There is marked obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by a dense bandlike layer of lymphocytic infiltrate, associated with vacuolar change and necrotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic clinical and histologic picture of a dermatosis commonly seen in dermatology offices: lichen planus (LP). As is often the case, by the time the patient gets to dermatology, the clinical picture can be confused and atypical. But there is much to learn from such a case.

LP is the prototypical interface lichenoid dermatitis, which can be depended on to present in certain identifiable ways. In this case, what suggested this diagnosis was the word “puzzling.” It’s the perfect example of the intuitive, somewhat subjective side of dermatologic diagnosis: When I see a condition that baffles me momentarily, my puzzled reaction becomes meaningful because the word puzzling starts with a “p.” Lichen planus has long been associated with an extremely useful mnemonic device known as “The Ps.” Besides puzzling, it can stand for purple, plaquish, polygonal (ie, not round), prurtitic, papular, penile (LP has a predilection for this area), and planar (ie, flat-topped).

But it’s the “puzzling” aspect that unlocks the entrance to “The Ps,” and that in turn leads to consideration of this diagnosis. In this case, LP was not totally obvious, but a biopsy confirmed my clinical suspicions by demonstrating the classic findings associated with it.

An LP-like eruption can be provoked by drugs, such as the antimalarials, gold compounds, and penicillamine. It has also been associated with hepatitis C. But in my experience, the most common trigger appears to be stress, since it’s a rare case that doesn’t involve some. (I’ll happily concede that this is my opinion and not established fact.)

This patient’s LP demonstrated two common variants: For one, the darker the patient’s skin, the deeper the purple color of the LP—sometimes to the point of obscuring the diagnosis.

As if that were not enough to confuse the examiner, there was an element of lichen simplex chronicus (LSC; also known as neurodermatitis), which instigates the “itch-scratch-itch” cycle. By its nature, LSC tends to hyperpigmentation (brown). By definition, it involves hypertrophy of the epidermis secondary to scratching. But there is always a primary cause; sometimes mere dry skin will trigger it, or insect bites, eczema, or even psoriasis. This confuses the issue, but the biopsy will establish the true basis for the patient’s condition.

The more common presentation of LP is that of a collection of flat-topped (“planar”), pruritic, purplish papules on the volar wrist, ankles, and sacral area. The surfaces of these lesions often demonstrate a faintly white, shiny surface. LP can also appear on oral mucosal surfaces, where it has a totally different, lacy-white look. In these areas, it tends to burn and not itch. LP appears to have a predilection for the penile glans, where it presents as an annular purplish plaque that sits astride the proximal glans, spilling over onto the coronal area.

LP can present as a widespread generalized eruption mimicking granuloma annulare and secondary syphilis. The differential for simple, classic LP includes psoriasis, granuloma annulare and pityriasis rosea.

Treatment of LP is with topical steroid creams or ointments, tailored in terms of strength to the area of involvement. For example, a class II or III corticosteroid would be used on areas with thicker skin and a class IV or V on thinner skin. Stubborn, solitary plaques can be treated with intralesional steroid injection (2.5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone solution).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is common and typically presents on the volar wrists, dorsal ankles, and sacrum.

• In a minority of cases, LP can present on the legs as a hypertrophic, plaquish condition with secondary features of lichen simplex chronicus.

• A mnemonic device (“The Ps”) describes LP: papular, pruritic, purple, planar, polygonal, plaquish, and (perhaps most importantly) “puzzling.”

• LP can present as an annular plaque on the penile glans.

• LP has a pathognomic histologic picture on biopsy.

When There’s More to the Story …

Three or four weeks ago, this 56-year-old man noticed asymptomatic lesions on his hands and feet. He says he’s never had anything like them before. He denies taking any new medications and claims to “feel fine,” with no fever, joint pain, or malaise.

EXAMINATION

Numerous round macules and papules are seen on the patient’s palms and soles, many of which have scaly peripheral margins. Most are brownish-red, and they are especially dense on the periphery of the feet.

Looking elsewhere, similar lesions are noted on the penile corona and glans. There is a faint but definite morbiliform, blanchable pink rash covering most of the patient’s trunk, taking on a “shawl” distribution across the shoulders.

These findings prompt a more directed and thorough history, which reveals that the patient is exclusively homosexual and recently engaged in high-risk sexual activity. He denies being HIV-positive, though he admits he hasn’t been tested for several years.

At this point, the patient admits to consulting a urologist two weeks ago. However, he came away from that visit with an assurance that serious disease was “unlikely.”

Accordingly, laboratory tests, including a rapid plasma reagin (RPR), are obtained. The RPR results are positive (1:64). The case is reported to the county health department.

DISCUSSION

It’s been said (by me and others) that half the job of any clinician is staying awake, in advance of the inevitable appearance of serious disease. These diseases are out there but don’t always appear the way they do in the textbooks. “Monroe’s rule #4” says the more serious the skin disease, the less likely it is to be diagnosed in a timely fashion.

It would be hard to imagine a more classic example of secondary syphilis than was seen in this case, occurring in a patient so obviously at risk. But it’s only “obvious” if you’re ready and aware of how syphilis manifests. It also helps if you understand how common it is and who’s likely to get it.

This patient’s primary care provider didn’t recognize the condition and referred the patient to a provider whose specialty is surgical diseases of the urogenital system. I mean no disrespect to urologists (or to urology PAs/NPs), but there’s no particular reason they would know what this was. It’s analogous to the referral of patients to podiatry for a rash or other lesion on the foot. Being a surgical expert on the structural maladies of the foot and ankle in no way imparts expertise in skin diseases of the same areas.

The point is: Skin diseases belong with the experts in skin disease (ie, dermatology providers). They are uniquely qualified, not only in terms of recognizing what is being seen, but in being able to see those findings in the context of other physical and historical data. This case is the perfect example.

Here’s the thought process that occurred in this case: Rashes of the feet and palms are unusual, though far from unknown. But when the rash is composed of round, slightly scaly lesions concentrated on the peripheral feet and hands, the differential narrows significantly. Pointed questions regarding sexual history become necessary. Homosexuality, by itself, is not a risk factor, but engaging in high-risk behaviors performed with exclusively homosexual partners is. These facts, combined with the discovery of the widespread truncal rash, mandated specific blood tests; once those tests confirmed the suspected diagnosis, the law mandated reporting of the case to the health department.

Representatives of said entity will likely confirm the diagnosis with more specific testing, treat the patient (probably with penicillin injection), then take a detailed history of sexual exposure in order to stop the spread of the disease in the community. Physically, this patient will be fine. But, as one might imagine, more fallout can be expected in terms of accusations and denials.

Other items in the differential for such rashes include: lichen planus, psoriasis, and erythema multiforme. A biopsy would have been necessary had the tests for syphilis been negative.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Palmar and plantar rashes are unusual and should prompt the examiner to expand the history and physical.

• Secondary syphilis, though uncommon, is far from rare, especially among gay men engaging in high-risk sexual behavior.

• It’s common for the patient to deny the appearance of the chancre of primary syphilis, and such a lesion would be long gone by the time those of secondary syphilis manifest.

• Conditions involving the skin should be seen by a dermatology provider, regardless of location. This includes diseases of the skin, hair, nails, oral mucosa, genitals, feet, or palms. One potential exception is the eye itself, though most diseases “of the eye” are, in reality, diseases of the periocular skin—and belong with a dermatology provider.

Three or four weeks ago, this 56-year-old man noticed asymptomatic lesions on his hands and feet. He says he’s never had anything like them before. He denies taking any new medications and claims to “feel fine,” with no fever, joint pain, or malaise.

EXAMINATION

Numerous round macules and papules are seen on the patient’s palms and soles, many of which have scaly peripheral margins. Most are brownish-red, and they are especially dense on the periphery of the feet.

Looking elsewhere, similar lesions are noted on the penile corona and glans. There is a faint but definite morbiliform, blanchable pink rash covering most of the patient’s trunk, taking on a “shawl” distribution across the shoulders.

These findings prompt a more directed and thorough history, which reveals that the patient is exclusively homosexual and recently engaged in high-risk sexual activity. He denies being HIV-positive, though he admits he hasn’t been tested for several years.

At this point, the patient admits to consulting a urologist two weeks ago. However, he came away from that visit with an assurance that serious disease was “unlikely.”

Accordingly, laboratory tests, including a rapid plasma reagin (RPR), are obtained. The RPR results are positive (1:64). The case is reported to the county health department.

DISCUSSION

It’s been said (by me and others) that half the job of any clinician is staying awake, in advance of the inevitable appearance of serious disease. These diseases are out there but don’t always appear the way they do in the textbooks. “Monroe’s rule #4” says the more serious the skin disease, the less likely it is to be diagnosed in a timely fashion.

It would be hard to imagine a more classic example of secondary syphilis than was seen in this case, occurring in a patient so obviously at risk. But it’s only “obvious” if you’re ready and aware of how syphilis manifests. It also helps if you understand how common it is and who’s likely to get it.

This patient’s primary care provider didn’t recognize the condition and referred the patient to a provider whose specialty is surgical diseases of the urogenital system. I mean no disrespect to urologists (or to urology PAs/NPs), but there’s no particular reason they would know what this was. It’s analogous to the referral of patients to podiatry for a rash or other lesion on the foot. Being a surgical expert on the structural maladies of the foot and ankle in no way imparts expertise in skin diseases of the same areas.

The point is: Skin diseases belong with the experts in skin disease (ie, dermatology providers). They are uniquely qualified, not only in terms of recognizing what is being seen, but in being able to see those findings in the context of other physical and historical data. This case is the perfect example.

Here’s the thought process that occurred in this case: Rashes of the feet and palms are unusual, though far from unknown. But when the rash is composed of round, slightly scaly lesions concentrated on the peripheral feet and hands, the differential narrows significantly. Pointed questions regarding sexual history become necessary. Homosexuality, by itself, is not a risk factor, but engaging in high-risk behaviors performed with exclusively homosexual partners is. These facts, combined with the discovery of the widespread truncal rash, mandated specific blood tests; once those tests confirmed the suspected diagnosis, the law mandated reporting of the case to the health department.

Representatives of said entity will likely confirm the diagnosis with more specific testing, treat the patient (probably with penicillin injection), then take a detailed history of sexual exposure in order to stop the spread of the disease in the community. Physically, this patient will be fine. But, as one might imagine, more fallout can be expected in terms of accusations and denials.

Other items in the differential for such rashes include: lichen planus, psoriasis, and erythema multiforme. A biopsy would have been necessary had the tests for syphilis been negative.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Palmar and plantar rashes are unusual and should prompt the examiner to expand the history and physical.

• Secondary syphilis, though uncommon, is far from rare, especially among gay men engaging in high-risk sexual behavior.

• It’s common for the patient to deny the appearance of the chancre of primary syphilis, and such a lesion would be long gone by the time those of secondary syphilis manifest.

• Conditions involving the skin should be seen by a dermatology provider, regardless of location. This includes diseases of the skin, hair, nails, oral mucosa, genitals, feet, or palms. One potential exception is the eye itself, though most diseases “of the eye” are, in reality, diseases of the periocular skin—and belong with a dermatology provider.

Three or four weeks ago, this 56-year-old man noticed asymptomatic lesions on his hands and feet. He says he’s never had anything like them before. He denies taking any new medications and claims to “feel fine,” with no fever, joint pain, or malaise.

EXAMINATION

Numerous round macules and papules are seen on the patient’s palms and soles, many of which have scaly peripheral margins. Most are brownish-red, and they are especially dense on the periphery of the feet.

Looking elsewhere, similar lesions are noted on the penile corona and glans. There is a faint but definite morbiliform, blanchable pink rash covering most of the patient’s trunk, taking on a “shawl” distribution across the shoulders.

These findings prompt a more directed and thorough history, which reveals that the patient is exclusively homosexual and recently engaged in high-risk sexual activity. He denies being HIV-positive, though he admits he hasn’t been tested for several years.

At this point, the patient admits to consulting a urologist two weeks ago. However, he came away from that visit with an assurance that serious disease was “unlikely.”

Accordingly, laboratory tests, including a rapid plasma reagin (RPR), are obtained. The RPR results are positive (1:64). The case is reported to the county health department.

DISCUSSION

It’s been said (by me and others) that half the job of any clinician is staying awake, in advance of the inevitable appearance of serious disease. These diseases are out there but don’t always appear the way they do in the textbooks. “Monroe’s rule #4” says the more serious the skin disease, the less likely it is to be diagnosed in a timely fashion.

It would be hard to imagine a more classic example of secondary syphilis than was seen in this case, occurring in a patient so obviously at risk. But it’s only “obvious” if you’re ready and aware of how syphilis manifests. It also helps if you understand how common it is and who’s likely to get it.

This patient’s primary care provider didn’t recognize the condition and referred the patient to a provider whose specialty is surgical diseases of the urogenital system. I mean no disrespect to urologists (or to urology PAs/NPs), but there’s no particular reason they would know what this was. It’s analogous to the referral of patients to podiatry for a rash or other lesion on the foot. Being a surgical expert on the structural maladies of the foot and ankle in no way imparts expertise in skin diseases of the same areas.

The point is: Skin diseases belong with the experts in skin disease (ie, dermatology providers). They are uniquely qualified, not only in terms of recognizing what is being seen, but in being able to see those findings in the context of other physical and historical data. This case is the perfect example.

Here’s the thought process that occurred in this case: Rashes of the feet and palms are unusual, though far from unknown. But when the rash is composed of round, slightly scaly lesions concentrated on the peripheral feet and hands, the differential narrows significantly. Pointed questions regarding sexual history become necessary. Homosexuality, by itself, is not a risk factor, but engaging in high-risk behaviors performed with exclusively homosexual partners is. These facts, combined with the discovery of the widespread truncal rash, mandated specific blood tests; once those tests confirmed the suspected diagnosis, the law mandated reporting of the case to the health department.

Representatives of said entity will likely confirm the diagnosis with more specific testing, treat the patient (probably with penicillin injection), then take a detailed history of sexual exposure in order to stop the spread of the disease in the community. Physically, this patient will be fine. But, as one might imagine, more fallout can be expected in terms of accusations and denials.

Other items in the differential for such rashes include: lichen planus, psoriasis, and erythema multiforme. A biopsy would have been necessary had the tests for syphilis been negative.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Palmar and plantar rashes are unusual and should prompt the examiner to expand the history and physical.

• Secondary syphilis, though uncommon, is far from rare, especially among gay men engaging in high-risk sexual behavior.

• It’s common for the patient to deny the appearance of the chancre of primary syphilis, and such a lesion would be long gone by the time those of secondary syphilis manifest.

• Conditions involving the skin should be seen by a dermatology provider, regardless of location. This includes diseases of the skin, hair, nails, oral mucosa, genitals, feet, or palms. One potential exception is the eye itself, though most diseases “of the eye” are, in reality, diseases of the periocular skin—and belong with a dermatology provider.

Painless Lesion Interferes With Man’s Vision

For years, this 80-year-old man has had a lesion on his right upper eyelid. It has slowly grown, though it causes no pain or other symptoms, and is now interfering with his lateral vision. This is what prompts him to seek evaluation.

His primary care providers over the years have seen the lesion. All have assured him of its benignancy.

In the distant past, the patient had a great deal of overexposure to the sun. Several skin cancers have been removed from his face.

At this time, he is residing in a rehab center, where he is recovering from a stroke. With his daughter’s assistance, the patient, who is not ambulatory and is a bit confused, is able to understand what is happening.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a well-defined, 5 mm x 1.1–cm pearly plaque located on the lateral portion of his left upper eyelid, within 2 to 3 mm of the lateral palpebral margin. It is seen in the context of heavily sun-damaged type II facial skin.

A shave biopsy indicates the lesion is a basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

DISCUSSION

BCCs, though rarely fatal, can be associated with a great deal of morbidity. This case highlights several issues regarding the diagnosis and treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers (eg, basal or squamous cell carcinoma)—not the least of which is the delayed diagnosis. In this instance, the delay is unlikely to harm the patient; however, that is not always the case. If this BCC had been a bit more aggressive, it could have invaded the periocular structures, which might have necessitated extensive surgery and possibly postoperative radiation.

Fortunately, this particular BCC was exceptionally slow to grow, to the extent that doing nothing was a serious consideration. If the patient had been older and/or less capable of cooperating with the surgical process, taking no action might have been the best choice.

But his BCC had grown, and he was able to state his preference (as did the family) to have it surgically removed. As of this writing, he has been scheduled for an appointment with a Mohs surgeon, who is likely to remove the lesion with margins. If the sample tests negative for residual cancer, the patient may not require further treatment. (Given the lesion’s location, the surgical wound does not even require closure, since they usually heal nicely by secondary intention.)

If microscopic examination reveals that the cancer extends into the eyelid itself, the patient will probably be referred to an oculoplastic surgeon for definitive excision and repair, which can be complex and difficult.

While the initial biopsy identified the lesion as a BCC, other items in the differential include seborrheic keratosis and even sebaceous carcinoma (an unusual diagnosis, but one common in patients this age). Squamous cell carcinoma and wart were also possibilities.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Changing lesions require investigation, usually in the form of a simple shave biopsy.

• Patients with a history of skin cancer tend to develop additional skin cancers.

• Not all basal cell carcinomas are aggressive. Some are remarkably slow-growing.

• For nonaggressive basal cell carcinomas in patients who are unable to cooperate with treatment decisions, consider doing nothing.

• The eyelid is a favorite location for an unusual type of skin cancer: sebaceous carcinoma.

For years, this 80-year-old man has had a lesion on his right upper eyelid. It has slowly grown, though it causes no pain or other symptoms, and is now interfering with his lateral vision. This is what prompts him to seek evaluation.

His primary care providers over the years have seen the lesion. All have assured him of its benignancy.

In the distant past, the patient had a great deal of overexposure to the sun. Several skin cancers have been removed from his face.

At this time, he is residing in a rehab center, where he is recovering from a stroke. With his daughter’s assistance, the patient, who is not ambulatory and is a bit confused, is able to understand what is happening.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a well-defined, 5 mm x 1.1–cm pearly plaque located on the lateral portion of his left upper eyelid, within 2 to 3 mm of the lateral palpebral margin. It is seen in the context of heavily sun-damaged type II facial skin.

A shave biopsy indicates the lesion is a basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

DISCUSSION

BCCs, though rarely fatal, can be associated with a great deal of morbidity. This case highlights several issues regarding the diagnosis and treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers (eg, basal or squamous cell carcinoma)—not the least of which is the delayed diagnosis. In this instance, the delay is unlikely to harm the patient; however, that is not always the case. If this BCC had been a bit more aggressive, it could have invaded the periocular structures, which might have necessitated extensive surgery and possibly postoperative radiation.

Fortunately, this particular BCC was exceptionally slow to grow, to the extent that doing nothing was a serious consideration. If the patient had been older and/or less capable of cooperating with the surgical process, taking no action might have been the best choice.

But his BCC had grown, and he was able to state his preference (as did the family) to have it surgically removed. As of this writing, he has been scheduled for an appointment with a Mohs surgeon, who is likely to remove the lesion with margins. If the sample tests negative for residual cancer, the patient may not require further treatment. (Given the lesion’s location, the surgical wound does not even require closure, since they usually heal nicely by secondary intention.)

If microscopic examination reveals that the cancer extends into the eyelid itself, the patient will probably be referred to an oculoplastic surgeon for definitive excision and repair, which can be complex and difficult.

While the initial biopsy identified the lesion as a BCC, other items in the differential include seborrheic keratosis and even sebaceous carcinoma (an unusual diagnosis, but one common in patients this age). Squamous cell carcinoma and wart were also possibilities.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Changing lesions require investigation, usually in the form of a simple shave biopsy.

• Patients with a history of skin cancer tend to develop additional skin cancers.

• Not all basal cell carcinomas are aggressive. Some are remarkably slow-growing.

• For nonaggressive basal cell carcinomas in patients who are unable to cooperate with treatment decisions, consider doing nothing.

• The eyelid is a favorite location for an unusual type of skin cancer: sebaceous carcinoma.

For years, this 80-year-old man has had a lesion on his right upper eyelid. It has slowly grown, though it causes no pain or other symptoms, and is now interfering with his lateral vision. This is what prompts him to seek evaluation.

His primary care providers over the years have seen the lesion. All have assured him of its benignancy.

In the distant past, the patient had a great deal of overexposure to the sun. Several skin cancers have been removed from his face.

At this time, he is residing in a rehab center, where he is recovering from a stroke. With his daughter’s assistance, the patient, who is not ambulatory and is a bit confused, is able to understand what is happening.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is a well-defined, 5 mm x 1.1–cm pearly plaque located on the lateral portion of his left upper eyelid, within 2 to 3 mm of the lateral palpebral margin. It is seen in the context of heavily sun-damaged type II facial skin.

A shave biopsy indicates the lesion is a basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

DISCUSSION

BCCs, though rarely fatal, can be associated with a great deal of morbidity. This case highlights several issues regarding the diagnosis and treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers (eg, basal or squamous cell carcinoma)—not the least of which is the delayed diagnosis. In this instance, the delay is unlikely to harm the patient; however, that is not always the case. If this BCC had been a bit more aggressive, it could have invaded the periocular structures, which might have necessitated extensive surgery and possibly postoperative radiation.

Fortunately, this particular BCC was exceptionally slow to grow, to the extent that doing nothing was a serious consideration. If the patient had been older and/or less capable of cooperating with the surgical process, taking no action might have been the best choice.

But his BCC had grown, and he was able to state his preference (as did the family) to have it surgically removed. As of this writing, he has been scheduled for an appointment with a Mohs surgeon, who is likely to remove the lesion with margins. If the sample tests negative for residual cancer, the patient may not require further treatment. (Given the lesion’s location, the surgical wound does not even require closure, since they usually heal nicely by secondary intention.)

If microscopic examination reveals that the cancer extends into the eyelid itself, the patient will probably be referred to an oculoplastic surgeon for definitive excision and repair, which can be complex and difficult.

While the initial biopsy identified the lesion as a BCC, other items in the differential include seborrheic keratosis and even sebaceous carcinoma (an unusual diagnosis, but one common in patients this age). Squamous cell carcinoma and wart were also possibilities.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Changing lesions require investigation, usually in the form of a simple shave biopsy.

• Patients with a history of skin cancer tend to develop additional skin cancers.

• Not all basal cell carcinomas are aggressive. Some are remarkably slow-growing.

• For nonaggressive basal cell carcinomas in patients who are unable to cooperate with treatment decisions, consider doing nothing.

• The eyelid is a favorite location for an unusual type of skin cancer: sebaceous carcinoma.

Cryotherapy: A Beginner’s Guide

Without a doubt, the most useful treatment modality I’ve acquired in my career is the proper use of liquid nitrogen. Cryotherapy is the standard treatment for small epidermal lesions, because it allows for removal without the need for anesthesia, with no broken skin or bleeding, and with a tolerable amount of pain.

Over the years, I’ve learned—often the hard way!—how to work with liquid nitrogen. For example, for the past 25 years, I’ve used a cryogun (or “unit,” as it’s sometimes called), having discovered that applying LN2 with anything else (eg, a cotton-tipped applicator) is a huge exercise in futility.

As with any tool in medicine, there are uses and misuses of cryotherapy. It is not intuitive—but it does yield to common sense. So allow me to give you the benefit of my experience.

APPROPRIATE AND INAPPROPRIATE TARGETS

In general, only epidermal lesions of obvious origin are treated with liquid nitrogen. This includes ordinary skin tags, small warts, and seborrheic and actinic keratosis. Utterly common and easy to treat, these lesions have no potential for malignant transformation and have relatively poor vasculature, which makes them ideal candidates for controlled, localized frostbite. This process (which can take as long as two weeks) kills the cells, disrupts the blood supply, and causes the lesions to die and fall away.

Other uses for cryotherapy include softening keloids or hypertrophic scars sufficiently to facilitate intralesional injection; treating condyloma, molluscum contagiosum, and small chondromdermatitis nodules; and even to destroy skin cancers (basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas)—the latter, however, only by clinicians with specialized training.

Inappropriate targets for cryotherapy include “moles” (nevi), vascular lesions such as hemangiomas, “birthmarks,” or any lesion of unknown nature. There are two reasons not to use liquid nitrogen in these cases: First, relatively well–vascularized lesions will be superficially blistered but will survive the treatment. Second, these lesions have at least a theoretical chance of having undergone malignant transformation. (As such, these lesions may need to be sampled to determine whether they are malignant; but that is a discussion for another column.)

THE NEED FOR CAUTION

For all its positive features, there are drawbacks to using cryotherapy. Here are six to consider:

• Blistering, which can be severe in sensitive patients

• Dyschromia (color changes in treated skin), especially in darker-skinned patients

• Pain, particularly in children

• Loss of function (eg, nerve or cartilage damage)

• Scarring, usually from overtreatment

• Disability—walking (let alone running or working) may be painful for a day or two after treatment, especially following brisk cryotherapy of a larger plantar wart

TREATING WARTS WITH CRYOTHERAPY

First, you must confirm the diagnosis: “Seeds” (black dots on the surface, which really represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries) are pathognomic. Warts lack surface skin lines (dermatoglyphics) and do not umbilicate on paring (unlike clavi or corns).

Always discuss indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks prior to performing cryotherapy. Patients (and parents) need to understand that the “perfect” treatment for warts has yet to be devised. All currently available methods have shortcomings.

Consider using an ear speculum (3 to 5 mm) to concentrate the spray of liquid nitrogen, reducing pain and shortening the length of treatment. Particularly with thicker plantar warts, you might want to pare away surface keratotic material first, then use the “freeze-thaw-freeze” technique. The average length of a single treatment seldom exceeds five seconds, particularly if a speculum or other dam is used.

Arrange for follow-up, typically one month later, since it’s a rare wart that clears with a single treatment.

Without a doubt, the most useful treatment modality I’ve acquired in my career is the proper use of liquid nitrogen. Cryotherapy is the standard treatment for small epidermal lesions, because it allows for removal without the need for anesthesia, with no broken skin or bleeding, and with a tolerable amount of pain.

Over the years, I’ve learned—often the hard way!—how to work with liquid nitrogen. For example, for the past 25 years, I’ve used a cryogun (or “unit,” as it’s sometimes called), having discovered that applying LN2 with anything else (eg, a cotton-tipped applicator) is a huge exercise in futility.

As with any tool in medicine, there are uses and misuses of cryotherapy. It is not intuitive—but it does yield to common sense. So allow me to give you the benefit of my experience.

APPROPRIATE AND INAPPROPRIATE TARGETS

In general, only epidermal lesions of obvious origin are treated with liquid nitrogen. This includes ordinary skin tags, small warts, and seborrheic and actinic keratosis. Utterly common and easy to treat, these lesions have no potential for malignant transformation and have relatively poor vasculature, which makes them ideal candidates for controlled, localized frostbite. This process (which can take as long as two weeks) kills the cells, disrupts the blood supply, and causes the lesions to die and fall away.

Other uses for cryotherapy include softening keloids or hypertrophic scars sufficiently to facilitate intralesional injection; treating condyloma, molluscum contagiosum, and small chondromdermatitis nodules; and even to destroy skin cancers (basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas)—the latter, however, only by clinicians with specialized training.

Inappropriate targets for cryotherapy include “moles” (nevi), vascular lesions such as hemangiomas, “birthmarks,” or any lesion of unknown nature. There are two reasons not to use liquid nitrogen in these cases: First, relatively well–vascularized lesions will be superficially blistered but will survive the treatment. Second, these lesions have at least a theoretical chance of having undergone malignant transformation. (As such, these lesions may need to be sampled to determine whether they are malignant; but that is a discussion for another column.)

THE NEED FOR CAUTION

For all its positive features, there are drawbacks to using cryotherapy. Here are six to consider:

• Blistering, which can be severe in sensitive patients

• Dyschromia (color changes in treated skin), especially in darker-skinned patients

• Pain, particularly in children

• Loss of function (eg, nerve or cartilage damage)

• Scarring, usually from overtreatment

• Disability—walking (let alone running or working) may be painful for a day or two after treatment, especially following brisk cryotherapy of a larger plantar wart

TREATING WARTS WITH CRYOTHERAPY

First, you must confirm the diagnosis: “Seeds” (black dots on the surface, which really represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries) are pathognomic. Warts lack surface skin lines (dermatoglyphics) and do not umbilicate on paring (unlike clavi or corns).

Always discuss indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks prior to performing cryotherapy. Patients (and parents) need to understand that the “perfect” treatment for warts has yet to be devised. All currently available methods have shortcomings.

Consider using an ear speculum (3 to 5 mm) to concentrate the spray of liquid nitrogen, reducing pain and shortening the length of treatment. Particularly with thicker plantar warts, you might want to pare away surface keratotic material first, then use the “freeze-thaw-freeze” technique. The average length of a single treatment seldom exceeds five seconds, particularly if a speculum or other dam is used.

Arrange for follow-up, typically one month later, since it’s a rare wart that clears with a single treatment.

Without a doubt, the most useful treatment modality I’ve acquired in my career is the proper use of liquid nitrogen. Cryotherapy is the standard treatment for small epidermal lesions, because it allows for removal without the need for anesthesia, with no broken skin or bleeding, and with a tolerable amount of pain.

Over the years, I’ve learned—often the hard way!—how to work with liquid nitrogen. For example, for the past 25 years, I’ve used a cryogun (or “unit,” as it’s sometimes called), having discovered that applying LN2 with anything else (eg, a cotton-tipped applicator) is a huge exercise in futility.

As with any tool in medicine, there are uses and misuses of cryotherapy. It is not intuitive—but it does yield to common sense. So allow me to give you the benefit of my experience.

APPROPRIATE AND INAPPROPRIATE TARGETS

In general, only epidermal lesions of obvious origin are treated with liquid nitrogen. This includes ordinary skin tags, small warts, and seborrheic and actinic keratosis. Utterly common and easy to treat, these lesions have no potential for malignant transformation and have relatively poor vasculature, which makes them ideal candidates for controlled, localized frostbite. This process (which can take as long as two weeks) kills the cells, disrupts the blood supply, and causes the lesions to die and fall away.

Other uses for cryotherapy include softening keloids or hypertrophic scars sufficiently to facilitate intralesional injection; treating condyloma, molluscum contagiosum, and small chondromdermatitis nodules; and even to destroy skin cancers (basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas)—the latter, however, only by clinicians with specialized training.

Inappropriate targets for cryotherapy include “moles” (nevi), vascular lesions such as hemangiomas, “birthmarks,” or any lesion of unknown nature. There are two reasons not to use liquid nitrogen in these cases: First, relatively well–vascularized lesions will be superficially blistered but will survive the treatment. Second, these lesions have at least a theoretical chance of having undergone malignant transformation. (As such, these lesions may need to be sampled to determine whether they are malignant; but that is a discussion for another column.)

THE NEED FOR CAUTION

For all its positive features, there are drawbacks to using cryotherapy. Here are six to consider:

• Blistering, which can be severe in sensitive patients

• Dyschromia (color changes in treated skin), especially in darker-skinned patients

• Pain, particularly in children

• Loss of function (eg, nerve or cartilage damage)

• Scarring, usually from overtreatment

• Disability—walking (let alone running or working) may be painful for a day or two after treatment, especially following brisk cryotherapy of a larger plantar wart

TREATING WARTS WITH CRYOTHERAPY

First, you must confirm the diagnosis: “Seeds” (black dots on the surface, which really represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries) are pathognomic. Warts lack surface skin lines (dermatoglyphics) and do not umbilicate on paring (unlike clavi or corns).

Always discuss indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks prior to performing cryotherapy. Patients (and parents) need to understand that the “perfect” treatment for warts has yet to be devised. All currently available methods have shortcomings.

Consider using an ear speculum (3 to 5 mm) to concentrate the spray of liquid nitrogen, reducing pain and shortening the length of treatment. Particularly with thicker plantar warts, you might want to pare away surface keratotic material first, then use the “freeze-thaw-freeze” technique. The average length of a single treatment seldom exceeds five seconds, particularly if a speculum or other dam is used.

Arrange for follow-up, typically one month later, since it’s a rare wart that clears with a single treatment.

A Little Pink in the Cheeks Signals Serious Problem

A 37-year-old man presents with a complaint of a scalp rash that first appeared several months ago. On his friends’ advice, he tried changing shampoos and applying tea tree oil, with no discernible improvement. He has never had problems with his scalp before, but there is a family history of “unknown skin disease” (mentioned by his father in past conversations). The patient denies any other skin problems.

Recently, he’s experienced a lot of stress: job loss, marital strife, and a subsequent increase in alcohol intake. He has also gained weight, adding that he isn’t getting any exercise. He denies joint pain or swelling.

EXAMINATION

Faint scaling is seen in the patient’s scalp, most of it over and behind the ears. These areas are modestly excoriated as well. There is similar faint scale in both external auditory meati. Examination of the fingernails reveals modest, scattered pits in four nail plates, which the patient says have been there “on and off for years.”

Looking elsewhere, focal heavy white scaling is noted on one knee and both elbows. These findings prompt examination of the patient’s upper intergluteal area, where definite pinkish erythema is observed. It covers an area of 7 x 4 cm, with no significant scaling.

DISCUSSION

You might expect a skin disease that “runs in the family” to be well known to all of them, but in truth, it’s quite common for family members to suffer for years without seeking evaluation by dermatology. Even worse, they might be misdiagnosed by someone else and spend a lifetime thinking they have “eczema” or “ringworm,” and passing this misinformation on to their kin.

Psoriasis is like that; it can present in so many ways, and it can also vary extensively in severity and morphology from one generation to another. As such, while most cases of psoriasis are obvious and therefore easy to diagnose, some are more obscure.

It helps to know how common psoriasis is: It affects 3% of the population, which equates to about 9 million people in the United States. Many, like this patient, have relatively mild cases that flare with stress. Known stressors include infection (especially strep) or introduction of certain medications (eg, β-blockers and lithium). A history of genetic predisposition can be obtained in about 30% of such cases.

This case illustrates a major point about the diagnosis of psoriasis: Often, it must be cobbled together from a collection of findings that appear disconnected on first glance. The scalp findings, by themselves, could have simply represented dry skin or seborrhea. However, taken in context with the nail changes, the family history, the extensor involvement, and intergluteal “pinking,” an almost certain diagnosis emerges.

The intergluteal pinking, by the way, can also be seen with seborrhea—so it’s not pathognomic for psoriasis but is highly suggestive of that diagnosis. The salmon-pink color and lack of scaling (because of the friction and moisture in the affected area) are especially typical.

Those tempted to dismiss all of this as mere sophistry have likely never experienced the effects of this disease, which is notorious for its association with serious negative psychologic repercussions, such as depression, isolation, and suicide. Imagine, for example, having to vacuum out your bed and surrounding carpet every morning just to remove the skin that was shed overnight, then having to be seen and judged by the public.

And that’s not even the worst of it. Up to 30% of psoriatic patients go on to develop psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive form of inflammatory arthritis that is relentless in its course without correct diagnosis and treatment. We know a great deal more about this autoimmune disease now than when I started out in dermatology, and we have marvelous treatment for it, more of which are in the research pipeline.

But these are of little use without the one essential ingredient the clinician must supply: a correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Weight gain, smoking, and stress are all documented triggers for psoriasis.

• A positive family history of psoriasis can be obtained in about 30% of suspected cases, but a negative history does not rule out the diagnosis.

• Certain medications, such as β-blockers and lithium, can trigger exacerbations of psoriasis.

• Psoriasis often presents with what appear to be unrelated findings, such as scalp rash, nail pits, genital involvement, and intergluteal pinking.

• Psoriasis is associated with significant psychologic pathology, including poor body image, depression, isolation, increased incidence of drug and alcohol abuse, and suicide.

• Almost 30% of psoriasis patients will develop a related form of arthritis called psoriatic arthropathy.

• Effective treatment is available for psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy, but these conditions must first be suspected and diagnosed.

A 37-year-old man presents with a complaint of a scalp rash that first appeared several months ago. On his friends’ advice, he tried changing shampoos and applying tea tree oil, with no discernible improvement. He has never had problems with his scalp before, but there is a family history of “unknown skin disease” (mentioned by his father in past conversations). The patient denies any other skin problems.

Recently, he’s experienced a lot of stress: job loss, marital strife, and a subsequent increase in alcohol intake. He has also gained weight, adding that he isn’t getting any exercise. He denies joint pain or swelling.

EXAMINATION

Faint scaling is seen in the patient’s scalp, most of it over and behind the ears. These areas are modestly excoriated as well. There is similar faint scale in both external auditory meati. Examination of the fingernails reveals modest, scattered pits in four nail plates, which the patient says have been there “on and off for years.”

Looking elsewhere, focal heavy white scaling is noted on one knee and both elbows. These findings prompt examination of the patient’s upper intergluteal area, where definite pinkish erythema is observed. It covers an area of 7 x 4 cm, with no significant scaling.

DISCUSSION

You might expect a skin disease that “runs in the family” to be well known to all of them, but in truth, it’s quite common for family members to suffer for years without seeking evaluation by dermatology. Even worse, they might be misdiagnosed by someone else and spend a lifetime thinking they have “eczema” or “ringworm,” and passing this misinformation on to their kin.

Psoriasis is like that; it can present in so many ways, and it can also vary extensively in severity and morphology from one generation to another. As such, while most cases of psoriasis are obvious and therefore easy to diagnose, some are more obscure.

It helps to know how common psoriasis is: It affects 3% of the population, which equates to about 9 million people in the United States. Many, like this patient, have relatively mild cases that flare with stress. Known stressors include infection (especially strep) or introduction of certain medications (eg, β-blockers and lithium). A history of genetic predisposition can be obtained in about 30% of such cases.

This case illustrates a major point about the diagnosis of psoriasis: Often, it must be cobbled together from a collection of findings that appear disconnected on first glance. The scalp findings, by themselves, could have simply represented dry skin or seborrhea. However, taken in context with the nail changes, the family history, the extensor involvement, and intergluteal “pinking,” an almost certain diagnosis emerges.

The intergluteal pinking, by the way, can also be seen with seborrhea—so it’s not pathognomic for psoriasis but is highly suggestive of that diagnosis. The salmon-pink color and lack of scaling (because of the friction and moisture in the affected area) are especially typical.

Those tempted to dismiss all of this as mere sophistry have likely never experienced the effects of this disease, which is notorious for its association with serious negative psychologic repercussions, such as depression, isolation, and suicide. Imagine, for example, having to vacuum out your bed and surrounding carpet every morning just to remove the skin that was shed overnight, then having to be seen and judged by the public.

And that’s not even the worst of it. Up to 30% of psoriatic patients go on to develop psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive form of inflammatory arthritis that is relentless in its course without correct diagnosis and treatment. We know a great deal more about this autoimmune disease now than when I started out in dermatology, and we have marvelous treatment for it, more of which are in the research pipeline.

But these are of little use without the one essential ingredient the clinician must supply: a correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Weight gain, smoking, and stress are all documented triggers for psoriasis.

• A positive family history of psoriasis can be obtained in about 30% of suspected cases, but a negative history does not rule out the diagnosis.

• Certain medications, such as β-blockers and lithium, can trigger exacerbations of psoriasis.

• Psoriasis often presents with what appear to be unrelated findings, such as scalp rash, nail pits, genital involvement, and intergluteal pinking.

• Psoriasis is associated with significant psychologic pathology, including poor body image, depression, isolation, increased incidence of drug and alcohol abuse, and suicide.

• Almost 30% of psoriasis patients will develop a related form of arthritis called psoriatic arthropathy.

• Effective treatment is available for psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy, but these conditions must first be suspected and diagnosed.

A 37-year-old man presents with a complaint of a scalp rash that first appeared several months ago. On his friends’ advice, he tried changing shampoos and applying tea tree oil, with no discernible improvement. He has never had problems with his scalp before, but there is a family history of “unknown skin disease” (mentioned by his father in past conversations). The patient denies any other skin problems.

Recently, he’s experienced a lot of stress: job loss, marital strife, and a subsequent increase in alcohol intake. He has also gained weight, adding that he isn’t getting any exercise. He denies joint pain or swelling.

EXAMINATION

Faint scaling is seen in the patient’s scalp, most of it over and behind the ears. These areas are modestly excoriated as well. There is similar faint scale in both external auditory meati. Examination of the fingernails reveals modest, scattered pits in four nail plates, which the patient says have been there “on and off for years.”

Looking elsewhere, focal heavy white scaling is noted on one knee and both elbows. These findings prompt examination of the patient’s upper intergluteal area, where definite pinkish erythema is observed. It covers an area of 7 x 4 cm, with no significant scaling.

DISCUSSION

You might expect a skin disease that “runs in the family” to be well known to all of them, but in truth, it’s quite common for family members to suffer for years without seeking evaluation by dermatology. Even worse, they might be misdiagnosed by someone else and spend a lifetime thinking they have “eczema” or “ringworm,” and passing this misinformation on to their kin.

Psoriasis is like that; it can present in so many ways, and it can also vary extensively in severity and morphology from one generation to another. As such, while most cases of psoriasis are obvious and therefore easy to diagnose, some are more obscure.

It helps to know how common psoriasis is: It affects 3% of the population, which equates to about 9 million people in the United States. Many, like this patient, have relatively mild cases that flare with stress. Known stressors include infection (especially strep) or introduction of certain medications (eg, β-blockers and lithium). A history of genetic predisposition can be obtained in about 30% of such cases.

This case illustrates a major point about the diagnosis of psoriasis: Often, it must be cobbled together from a collection of findings that appear disconnected on first glance. The scalp findings, by themselves, could have simply represented dry skin or seborrhea. However, taken in context with the nail changes, the family history, the extensor involvement, and intergluteal “pinking,” an almost certain diagnosis emerges.

The intergluteal pinking, by the way, can also be seen with seborrhea—so it’s not pathognomic for psoriasis but is highly suggestive of that diagnosis. The salmon-pink color and lack of scaling (because of the friction and moisture in the affected area) are especially typical.

Those tempted to dismiss all of this as mere sophistry have likely never experienced the effects of this disease, which is notorious for its association with serious negative psychologic repercussions, such as depression, isolation, and suicide. Imagine, for example, having to vacuum out your bed and surrounding carpet every morning just to remove the skin that was shed overnight, then having to be seen and judged by the public.

And that’s not even the worst of it. Up to 30% of psoriatic patients go on to develop psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive form of inflammatory arthritis that is relentless in its course without correct diagnosis and treatment. We know a great deal more about this autoimmune disease now than when I started out in dermatology, and we have marvelous treatment for it, more of which are in the research pipeline.

But these are of little use without the one essential ingredient the clinician must supply: a correct diagnosis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Weight gain, smoking, and stress are all documented triggers for psoriasis.

• A positive family history of psoriasis can be obtained in about 30% of suspected cases, but a negative history does not rule out the diagnosis.

• Certain medications, such as β-blockers and lithium, can trigger exacerbations of psoriasis.

• Psoriasis often presents with what appear to be unrelated findings, such as scalp rash, nail pits, genital involvement, and intergluteal pinking.

• Psoriasis is associated with significant psychologic pathology, including poor body image, depression, isolation, increased incidence of drug and alcohol abuse, and suicide.

• Almost 30% of psoriasis patients will develop a related form of arthritis called psoriatic arthropathy.

• Effective treatment is available for psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy, but these conditions must first be suspected and diagnosed.

The Most Problematic Warts Have No Sure Treatment

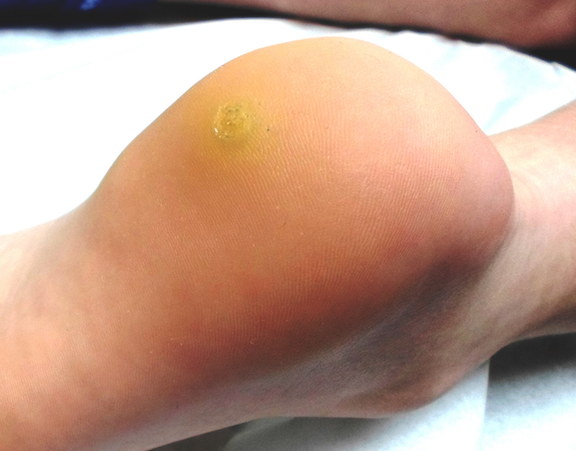

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.