User login

Unintentional weight loss

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma, with nodal involvement.

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide. In Western countries, 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives. Various histologic subtypes with specific clinical characteristics exist. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common subtype, accounting for an estimated 10%-15% of breast cancers. Over the past two decades, a significant increase has been observed in the incidence of ILC, particularly among postmenopausal women. Improved diagnostic techniques and the use of hormone replacement therapy may account for this increased incidence. White women have the highest incidence of ILC; however, compared with White women and women of other races, Black women experience the worst 5-year overall survival from ILC.

ILC arises in the mammary ducts (lobules) of the breast. Women with ILC are typically slightly older than women with invasive breast cancer of no special type at diagnosis (mean age 63.4 vs 59.5 years, respectively). Risk factors for ILC may include early menarche, use of progesterone-based hormone replacement therapy, late age at first live birth, and alcohol consumption.

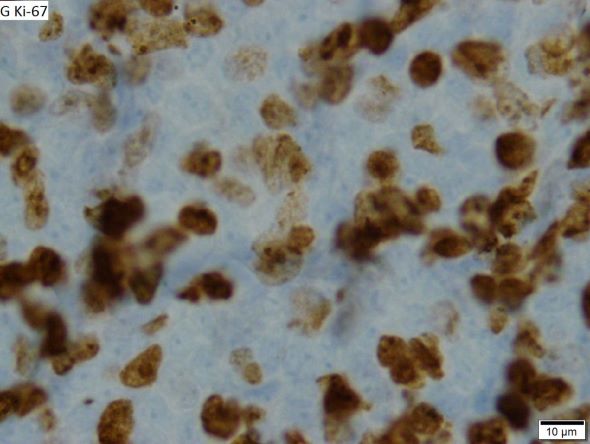

In most cases, ILC does not form a discrete palpable mass until it has reached an advanced stage, making it more difficult to detect through physical examination or imaging. Patients often present with a large tumor and with nodal involvement. A slight thickening of the nipple, an exudative scab on the skin, or other changes in the skin, such as flushing or swelling, may be seen in patients presenting with advanced disease. Additionally, ILC tumors are often bilateral and multifocal.

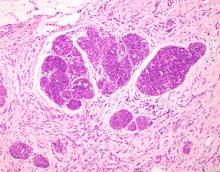

ILC is predominantly a histopathologic diagnosis based on standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Histologically, ILC is characterized by a proliferation of small cells that lack cohesion. These cells are often dispersed individually through a fibrous connective tissue; alternatively, they may be organized in single-file linear cords invading the stroma. A concentric pattern around normal ducts is often seen in the infiltrating cords. There is usually little host reaction of the background architecture. Round or notched ovoid nuclei are seen in the neoplastic cells, along with a thin rim of cytoplasm. Occasionally, an intracytoplasmic lumen is present and may harbor a central mucoid inclusion. Very few or no mitoses are seen.

Several variants of ILC exist, all of which lack cell-to-cell cohesion. These include:

• Solid type

• Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma

• Tubulo-lobular variant

• Alveolar variant

• Mixed type

Complete loss of E-cadherin expression occurs in most ILCs, which can help to differentiate it from invasive ductal cancers or ductal carcinomas in situ. Diffuse cortical thickening without hilar mass effect is often seen in nodal metastases associated with ILC.

Most classic ILCs are estrogen receptor– and progesterone receptor–positive. Conversely, HER2 overexpression and amplification rarely occurs in ILC.

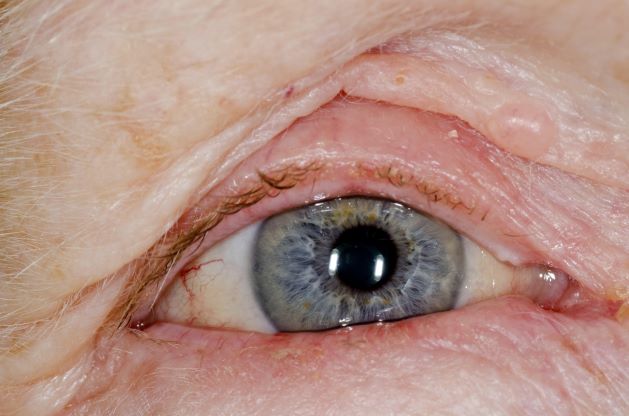

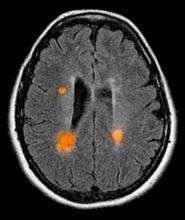

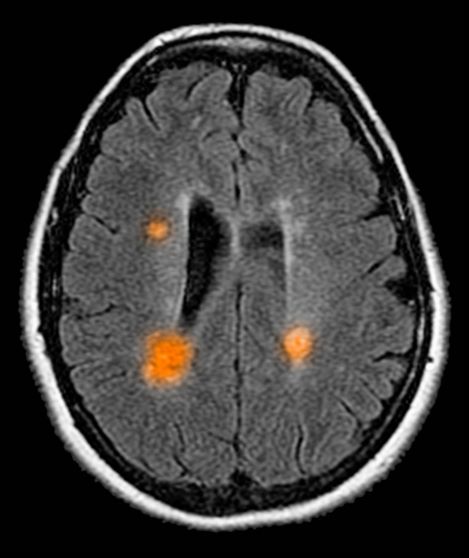

Late relapses more than 10 years after remission may occur. In addition to frequent bone and liver metastasis, ILC is associated with metastatic spread to unusual sites, including the peritoneum, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, leptomeninges, skin, orbit, and ovaries.

Mastectomy is often indicated in ILC. In the neoadjuvant setting, ILC is associated with low pathologic complete response rates. Endocrine therapy in the neoadjuvant setting is an emerging approach for some patients with ILC. According to 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, adjuvant chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone should be considered for pre- and postmenopausal patients with ILC.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma, with nodal involvement.

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide. In Western countries, 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives. Various histologic subtypes with specific clinical characteristics exist. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common subtype, accounting for an estimated 10%-15% of breast cancers. Over the past two decades, a significant increase has been observed in the incidence of ILC, particularly among postmenopausal women. Improved diagnostic techniques and the use of hormone replacement therapy may account for this increased incidence. White women have the highest incidence of ILC; however, compared with White women and women of other races, Black women experience the worst 5-year overall survival from ILC.

ILC arises in the mammary ducts (lobules) of the breast. Women with ILC are typically slightly older than women with invasive breast cancer of no special type at diagnosis (mean age 63.4 vs 59.5 years, respectively). Risk factors for ILC may include early menarche, use of progesterone-based hormone replacement therapy, late age at first live birth, and alcohol consumption.

In most cases, ILC does not form a discrete palpable mass until it has reached an advanced stage, making it more difficult to detect through physical examination or imaging. Patients often present with a large tumor and with nodal involvement. A slight thickening of the nipple, an exudative scab on the skin, or other changes in the skin, such as flushing or swelling, may be seen in patients presenting with advanced disease. Additionally, ILC tumors are often bilateral and multifocal.

ILC is predominantly a histopathologic diagnosis based on standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Histologically, ILC is characterized by a proliferation of small cells that lack cohesion. These cells are often dispersed individually through a fibrous connective tissue; alternatively, they may be organized in single-file linear cords invading the stroma. A concentric pattern around normal ducts is often seen in the infiltrating cords. There is usually little host reaction of the background architecture. Round or notched ovoid nuclei are seen in the neoplastic cells, along with a thin rim of cytoplasm. Occasionally, an intracytoplasmic lumen is present and may harbor a central mucoid inclusion. Very few or no mitoses are seen.

Several variants of ILC exist, all of which lack cell-to-cell cohesion. These include:

• Solid type

• Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma

• Tubulo-lobular variant

• Alveolar variant

• Mixed type

Complete loss of E-cadherin expression occurs in most ILCs, which can help to differentiate it from invasive ductal cancers or ductal carcinomas in situ. Diffuse cortical thickening without hilar mass effect is often seen in nodal metastases associated with ILC.

Most classic ILCs are estrogen receptor– and progesterone receptor–positive. Conversely, HER2 overexpression and amplification rarely occurs in ILC.

Late relapses more than 10 years after remission may occur. In addition to frequent bone and liver metastasis, ILC is associated with metastatic spread to unusual sites, including the peritoneum, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, leptomeninges, skin, orbit, and ovaries.

Mastectomy is often indicated in ILC. In the neoadjuvant setting, ILC is associated with low pathologic complete response rates. Endocrine therapy in the neoadjuvant setting is an emerging approach for some patients with ILC. According to 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, adjuvant chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone should be considered for pre- and postmenopausal patients with ILC.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma, with nodal involvement.

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide. In Western countries, 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives. Various histologic subtypes with specific clinical characteristics exist. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common subtype, accounting for an estimated 10%-15% of breast cancers. Over the past two decades, a significant increase has been observed in the incidence of ILC, particularly among postmenopausal women. Improved diagnostic techniques and the use of hormone replacement therapy may account for this increased incidence. White women have the highest incidence of ILC; however, compared with White women and women of other races, Black women experience the worst 5-year overall survival from ILC.

ILC arises in the mammary ducts (lobules) of the breast. Women with ILC are typically slightly older than women with invasive breast cancer of no special type at diagnosis (mean age 63.4 vs 59.5 years, respectively). Risk factors for ILC may include early menarche, use of progesterone-based hormone replacement therapy, late age at first live birth, and alcohol consumption.

In most cases, ILC does not form a discrete palpable mass until it has reached an advanced stage, making it more difficult to detect through physical examination or imaging. Patients often present with a large tumor and with nodal involvement. A slight thickening of the nipple, an exudative scab on the skin, or other changes in the skin, such as flushing or swelling, may be seen in patients presenting with advanced disease. Additionally, ILC tumors are often bilateral and multifocal.

ILC is predominantly a histopathologic diagnosis based on standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Histologically, ILC is characterized by a proliferation of small cells that lack cohesion. These cells are often dispersed individually through a fibrous connective tissue; alternatively, they may be organized in single-file linear cords invading the stroma. A concentric pattern around normal ducts is often seen in the infiltrating cords. There is usually little host reaction of the background architecture. Round or notched ovoid nuclei are seen in the neoplastic cells, along with a thin rim of cytoplasm. Occasionally, an intracytoplasmic lumen is present and may harbor a central mucoid inclusion. Very few or no mitoses are seen.

Several variants of ILC exist, all of which lack cell-to-cell cohesion. These include:

• Solid type

• Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma

• Tubulo-lobular variant

• Alveolar variant

• Mixed type

Complete loss of E-cadherin expression occurs in most ILCs, which can help to differentiate it from invasive ductal cancers or ductal carcinomas in situ. Diffuse cortical thickening without hilar mass effect is often seen in nodal metastases associated with ILC.

Most classic ILCs are estrogen receptor– and progesterone receptor–positive. Conversely, HER2 overexpression and amplification rarely occurs in ILC.

Late relapses more than 10 years after remission may occur. In addition to frequent bone and liver metastasis, ILC is associated with metastatic spread to unusual sites, including the peritoneum, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, leptomeninges, skin, orbit, and ovaries.

Mastectomy is often indicated in ILC. In the neoadjuvant setting, ILC is associated with low pathologic complete response rates. Endocrine therapy in the neoadjuvant setting is an emerging approach for some patients with ILC. According to 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, adjuvant chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone should be considered for pre- and postmenopausal patients with ILC.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 47-year-old woman presented for her annual gynecologic examination. Her current height and weight were 5 ft 4 in and 133 lb. This reflected a 9-lb weight loss since the previous visit. At completion of the height and weight intake by a nurse, the patient reported being surprised by this unintentional weight loss. Her previous medical history was unremarkable except for an advanced maternal age pregnancy 5 years earlier and dental implant surgery approximately 1 month earlier. The patient believed that her weight loss was related to her diminished appetite and transient difficulty chewing following her dental surgery. Laboratory findings were all within normal ranges except for a hemoglobin level of 9.4 g/dL. Physical examination revealed a palpable mass in the right upper outer quadrant of the right breast with slight thickening of the nipple and a right axillary mass. The patient's last bilateral screening mammogram 3 months earlier did not reveal any suspicious masses or lesions.

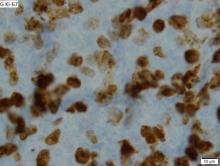

An ultrasound-guided biopsy of the right breast and axillary lymph node was performed. Histopathologic findings included small tumor cells without cohesion arranged in single files, loss of the long arm of chromosome 16, and a complete loss of E-cadherin expression on immunohistochemistry. Additionally, the tumor was estrogen receptor–positive/progesterone receptor–positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (ER+/PR+/HER2-).

Mild shortness of breath

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

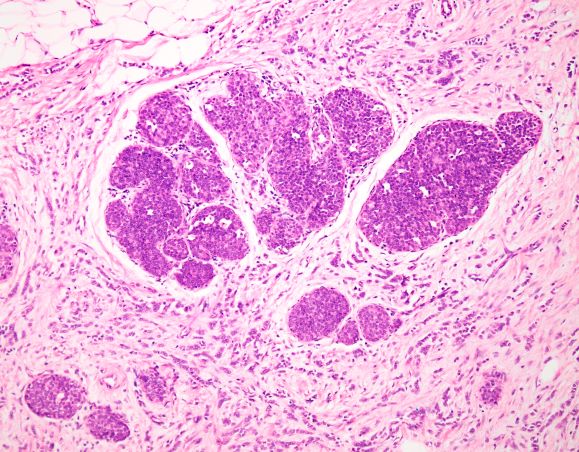

A 33-year-old African American woman presents for an initial consultation. The patient states that it has been several years since she received regular medical care because she did not have health insurance. She recently started a new job as an IT professional that has healthcare benefits. She does not currently take any medications. She reports mild shortness of breath upon exertion, which has worsened in the last year. She denies dizziness, chest pain, wheezing, cough, fever, or other associated symptoms. There is no history of any cardiac or pulmonary diseases as a child. The patient does not smoke or engage in recreational drug use. She is conscious of her diet and avoids red meat as well as sugary and processed foods. Although she was active in the past, she notes that she has been less intentional with her physical activity and has been living a more sedentary lifestyle recently. She has gained more than 40 lb over the past 3 years.

The patient is 5 ft 8 in, her weight is 266 lb (BMI 40.4), and her blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg. Her pulse oximeter is 97%; however, this result should be interpreted with caution and in consideration of the patient's other signs and symptoms because numerous studies have shown inaccuracies in pulse oximeter readings among people with darker skin. Her physical exam is unremarkable except for a waist circumference of 49 in; breathing sounds are normal and no dermatologic abnormalities are noted.

An ECG is performed and is normal. A chest radiograph shows normal heart and blood vessel structures and airways of the lungs. Pertinent laboratory findings include A1c of 6.4%, HDL cholesterol of 37 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol of 185 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL; AST of 27 U/L; ALT of 35 IU/L; and TSH of 4.2 mIU/L.

Abdominal pain and constipation

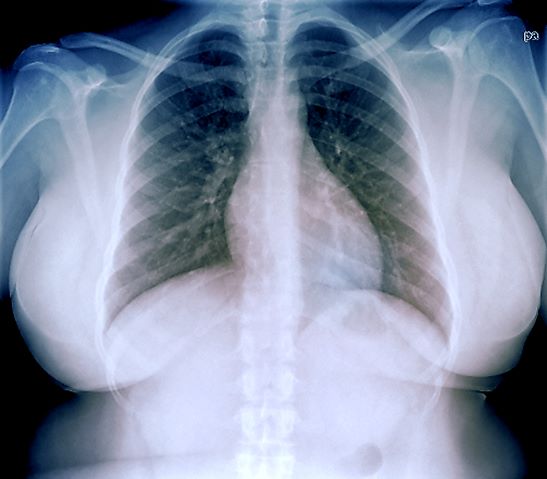

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old White woman presents with complaints of left-sided abdominal pain and constipation of 10-day duration. The patient's prior medical history is notable for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) treated 2 years earlier with RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. No lymphadenopathy is noted on physical examination. Abdominal examination reveals abdominal distension, normal bowel sounds, and left lower quadrant tenderness to palpation without guarding, rigidity, or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory test results including CBC are within normal range. Endoscopy reveals a growth in the colon, as shown in the image.

Increasing fatigue and dry cough

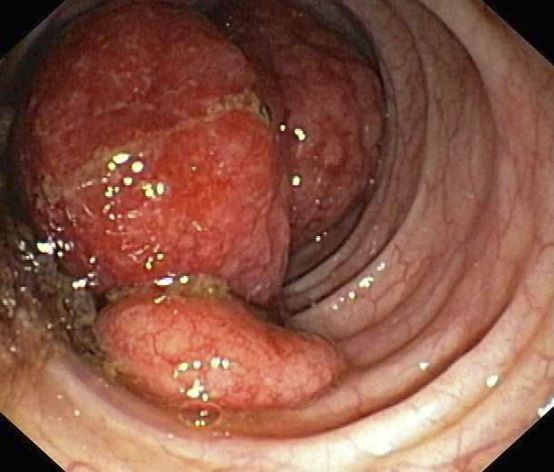

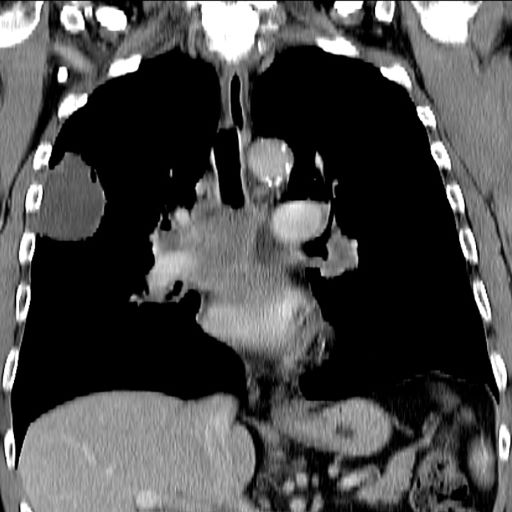

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 66-year-old African American man was diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) after the discovery of an endobronchial tumor on bronchoscopy. A biopsy of the tumor was positive for SCLC and CT revealed multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. The patient completed his first cycle of carboplatin-based chemotherapy about 1 month ago. At today's visit, he presents with complaints of worsening symptoms over the past week or so; specifically, he reports increasing fatigue and shortness of breath, a dry cough, light-headedness, difficulty swallowing, and facial swelling. Physical examination reveals facial edema and venous distension of the neck and chest wall; blood pressure is 140/70 mm Hg, respiratory rate is 19 breaths/min, and pulse is 84 beats/min. The patient has a 45-pack-year smoking history and reports having two or three alcoholic drinks per day. His previous medical history is positive for hypertension, which is treated with enalapril 20 mg/day and metoprolol 200 mg/day. Complete blood cell count findings are all within normal range.

Lesions on upper arms

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) complicated by skin infection.

AD is the most common chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disorder that affects both children and adults. In the United States, up to 18% of children and 7% of adults are affected. Atopic dermatitis is associated with diminished quality of life, including disruption in activities of daily living, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, patients with AD have an increased risk for infections. A significantly higher prevalence of cutaneous and systemic infections is seen in patients with AD compared with individuals without AD.

Bacterial infections are common in AD and are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Examples include impetigo, which typically presents with oozing serum that dries, resulting in a honey-crusted appearance surrounded by an erythematous base. Fluid-filled blisters (bullous impetigo) may also be present, which can be mistaken for eczema herpeticum (EH).

Nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) include erysipelas and cellulitis. In most cases, these infections begin in a focal skin area but spread rapidly across the affected sites such as the arms, legs, trunk, or face. Signs typically include focal erythema, swelling, warmth, and tenderness; fever and bacteremia may also be present.

Purulent SSTIs present as skin abscesses, involving fluctuant or nonfluctuant nodules or pustules surrounded by an erythematous swelling; the lesions may also be tender and warm. Methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is a common cause of purulent SSTIs.

Systemic complications of SSTI in AD may include bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or bursitis; less often, endocarditis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome may occur. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for these complications in patients who present with an ill-looking appearance, lethargy, focal point tenderness of the bone, joint swelling, heart murmur, and widespread desquamation. Persistent elevated inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) should increase the level of suspicion.

Nonbacterial infections can occur concurrently with bacterial skin infections and the two can be difficult to distinguish. For example, EH results from the local spread of herpes simplex virus, which has a predilection for AD lesions. Early during EH, skin lesions appear as superficial clusters of dome‐shaped vesicles and/or small, round, punched‐out erosions. With progression, the lesions may become superficially infected with S aureus and may develop the characteristic honey-colored scale of impetigo.

Factors that contribute to the increased prevalence of infections in AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, allergen sensitivity, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, and cutaneous dysbiosis.

Daily skin hydration and moisturization is a fundamental component of treatment for any patient with AD, both to treat the AD and prevent infection. Patients with AD should bathe daily, followed by gentle drying and application of a moisturizer or a prescribed topical medication. Standard topical anti-inflammatory medications, including topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors, improve skin barrier functions and have been reported to decrease S aureus colonization in AD lesions. Similarly, the monoclonal antibody dupilumab has been shown to decrease S aureus colonization and increase microbial diversity.

In the presence of an uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be sufficient, depending on clinical response or culture and in consideration of local epidemiology and resistance patterns. For patients with AD who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, coverage for MRSA should be considered. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Topical mupirocin ointment can be used for patients with minor, localized skin infections (eg, impetigo).

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) complicated by skin infection.

AD is the most common chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disorder that affects both children and adults. In the United States, up to 18% of children and 7% of adults are affected. Atopic dermatitis is associated with diminished quality of life, including disruption in activities of daily living, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, patients with AD have an increased risk for infections. A significantly higher prevalence of cutaneous and systemic infections is seen in patients with AD compared with individuals without AD.

Bacterial infections are common in AD and are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Examples include impetigo, which typically presents with oozing serum that dries, resulting in a honey-crusted appearance surrounded by an erythematous base. Fluid-filled blisters (bullous impetigo) may also be present, which can be mistaken for eczema herpeticum (EH).

Nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) include erysipelas and cellulitis. In most cases, these infections begin in a focal skin area but spread rapidly across the affected sites such as the arms, legs, trunk, or face. Signs typically include focal erythema, swelling, warmth, and tenderness; fever and bacteremia may also be present.

Purulent SSTIs present as skin abscesses, involving fluctuant or nonfluctuant nodules or pustules surrounded by an erythematous swelling; the lesions may also be tender and warm. Methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is a common cause of purulent SSTIs.

Systemic complications of SSTI in AD may include bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or bursitis; less often, endocarditis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome may occur. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for these complications in patients who present with an ill-looking appearance, lethargy, focal point tenderness of the bone, joint swelling, heart murmur, and widespread desquamation. Persistent elevated inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) should increase the level of suspicion.

Nonbacterial infections can occur concurrently with bacterial skin infections and the two can be difficult to distinguish. For example, EH results from the local spread of herpes simplex virus, which has a predilection for AD lesions. Early during EH, skin lesions appear as superficial clusters of dome‐shaped vesicles and/or small, round, punched‐out erosions. With progression, the lesions may become superficially infected with S aureus and may develop the characteristic honey-colored scale of impetigo.

Factors that contribute to the increased prevalence of infections in AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, allergen sensitivity, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, and cutaneous dysbiosis.

Daily skin hydration and moisturization is a fundamental component of treatment for any patient with AD, both to treat the AD and prevent infection. Patients with AD should bathe daily, followed by gentle drying and application of a moisturizer or a prescribed topical medication. Standard topical anti-inflammatory medications, including topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors, improve skin barrier functions and have been reported to decrease S aureus colonization in AD lesions. Similarly, the monoclonal antibody dupilumab has been shown to decrease S aureus colonization and increase microbial diversity.

In the presence of an uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be sufficient, depending on clinical response or culture and in consideration of local epidemiology and resistance patterns. For patients with AD who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, coverage for MRSA should be considered. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Topical mupirocin ointment can be used for patients with minor, localized skin infections (eg, impetigo).

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) complicated by skin infection.

AD is the most common chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disorder that affects both children and adults. In the United States, up to 18% of children and 7% of adults are affected. Atopic dermatitis is associated with diminished quality of life, including disruption in activities of daily living, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, patients with AD have an increased risk for infections. A significantly higher prevalence of cutaneous and systemic infections is seen in patients with AD compared with individuals without AD.

Bacterial infections are common in AD and are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Examples include impetigo, which typically presents with oozing serum that dries, resulting in a honey-crusted appearance surrounded by an erythematous base. Fluid-filled blisters (bullous impetigo) may also be present, which can be mistaken for eczema herpeticum (EH).

Nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) include erysipelas and cellulitis. In most cases, these infections begin in a focal skin area but spread rapidly across the affected sites such as the arms, legs, trunk, or face. Signs typically include focal erythema, swelling, warmth, and tenderness; fever and bacteremia may also be present.

Purulent SSTIs present as skin abscesses, involving fluctuant or nonfluctuant nodules or pustules surrounded by an erythematous swelling; the lesions may also be tender and warm. Methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is a common cause of purulent SSTIs.

Systemic complications of SSTI in AD may include bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or bursitis; less often, endocarditis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome may occur. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for these complications in patients who present with an ill-looking appearance, lethargy, focal point tenderness of the bone, joint swelling, heart murmur, and widespread desquamation. Persistent elevated inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) should increase the level of suspicion.

Nonbacterial infections can occur concurrently with bacterial skin infections and the two can be difficult to distinguish. For example, EH results from the local spread of herpes simplex virus, which has a predilection for AD lesions. Early during EH, skin lesions appear as superficial clusters of dome‐shaped vesicles and/or small, round, punched‐out erosions. With progression, the lesions may become superficially infected with S aureus and may develop the characteristic honey-colored scale of impetigo.

Factors that contribute to the increased prevalence of infections in AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, allergen sensitivity, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, and cutaneous dysbiosis.

Daily skin hydration and moisturization is a fundamental component of treatment for any patient with AD, both to treat the AD and prevent infection. Patients with AD should bathe daily, followed by gentle drying and application of a moisturizer or a prescribed topical medication. Standard topical anti-inflammatory medications, including topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors, improve skin barrier functions and have been reported to decrease S aureus colonization in AD lesions. Similarly, the monoclonal antibody dupilumab has been shown to decrease S aureus colonization and increase microbial diversity.

In the presence of an uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be sufficient, depending on clinical response or culture and in consideration of local epidemiology and resistance patterns. For patients with AD who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, coverage for MRSA should be considered. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Topical mupirocin ointment can be used for patients with minor, localized skin infections (eg, impetigo).

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 8-year-old girl presents with pruritic lesions on her upper arms. As an infant, the patient was treated for widespread dermatitis with topical steroids and emollients; recently, after a long symptom-free period, she has had multiple bouts of dermatitis on her face, knees, ankles, and elbows. According to the patient's mother, the patient bathes every 2-3 days to not dry out her skin. At the current visit, physical examination reveals scaly patches and plaques with a honey-colored crust surrounded by an erythematous base. No other family members are experiencing symptoms. There is a positive family history for atopy and asthma.

Fatigue and sporadic fever

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of malignant mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. MCL has a characteristic immunophenotype (ie, CD5+, CD10−, Bcl-2+, Bcl-6−, CD20+), with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, and expression of cyclin D1. The median age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases occur in men.

The clinical presentation of MCL can vary. Patients may have asymptomatic monoclonal MCL type lymphocytosis or nonbulky nodal/extra nodal disease with minimal symptoms, or they may present with significant symptoms, progressive generalized lymphadenopathy, cytopenia, splenomegaly, and extranodal disease, including gastrointestinal involvement (lymphomatous polyposis), kidney involvement, involvement of other organs, or, rarely, central nervous system involvement. Disease involving multiple lymph nodes and other sites of the body is seen in most patients. Approximately 70% of patients present with stage IV disease requiring systemic treatment.

According to 2022 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), essential components in the workup for MCL include:

• Physical examination, with attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer ring, and to size of liver and spleen

• Assessment of performance status and B symptoms (ie, fever > 100.4°F [may be sporadic], drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss of > 10% of body weight over 6 months or less)

• CBC with differential

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (an important prognostic marker)

• PET/CT scan (including neck)

• Hepatitis B testing if treatment with rituximab is being contemplated

• Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan if anthracycline or anthracenedione-based regimen is indicated

• Pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age (if chemotherapy or radiation therapy is planned)

Additional testing may be indicated in specific circumstances, such as colonoscopy/endoscopy.

MCL remains challenging to treat. While 50%-90% of patients with MCL respond to combination chemotherapy, only 30% achieve a complete response. Median time to treatment failure is < 18 months.

When selecting systemic treatment for patients with MCL, clinicians should consider the availability of clinical trials for subsets of patients, eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT), high-risk status (ie, blastoid MCL, high Ki-67% > 30%, or central nervous system involvement), age, and performance status. The addition of radiation to chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with limited-stage, nonbulky disease, although this has not been confirmed in large, randomized studies. Outside of clinical trials, the usual approach for frontline treatment of MCL is chemoimmunotherapy with/without autologous SCT and with/without maintenance therapy.

Available options for primary MCL therapy in patients who require systemic therapy include:

• Single alkylating agents

• CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone)

• CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [hydroxydaunorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone)

• Hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) with or without rituximab

• R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)

• Lenalidomide plus rituximab

• Hyper-CVAD with autologous SCT

Options for relapsed or refractory MCL include:

• R-hyper-CVAD

• Hyper-CVAD with or without rituximab followed by autologous SCT

• Nucleoside analogues and combinations

• Salvage chemotherapy combinations followed by autologous SCT

• Bortezomib

• Lenalidomide

• Ibrutinib

• Radioimmunotherapy

• Rituximab

• Rituximab and thalidomide combination

• Acalabrutinib

• High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or SCT

• Brexucabtagene autoleucel

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of malignant mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. MCL has a characteristic immunophenotype (ie, CD5+, CD10−, Bcl-2+, Bcl-6−, CD20+), with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, and expression of cyclin D1. The median age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases occur in men.

The clinical presentation of MCL can vary. Patients may have asymptomatic monoclonal MCL type lymphocytosis or nonbulky nodal/extra nodal disease with minimal symptoms, or they may present with significant symptoms, progressive generalized lymphadenopathy, cytopenia, splenomegaly, and extranodal disease, including gastrointestinal involvement (lymphomatous polyposis), kidney involvement, involvement of other organs, or, rarely, central nervous system involvement. Disease involving multiple lymph nodes and other sites of the body is seen in most patients. Approximately 70% of patients present with stage IV disease requiring systemic treatment.

According to 2022 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), essential components in the workup for MCL include:

• Physical examination, with attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer ring, and to size of liver and spleen

• Assessment of performance status and B symptoms (ie, fever > 100.4°F [may be sporadic], drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss of > 10% of body weight over 6 months or less)

• CBC with differential

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (an important prognostic marker)

• PET/CT scan (including neck)

• Hepatitis B testing if treatment with rituximab is being contemplated

• Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan if anthracycline or anthracenedione-based regimen is indicated

• Pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age (if chemotherapy or radiation therapy is planned)

Additional testing may be indicated in specific circumstances, such as colonoscopy/endoscopy.

MCL remains challenging to treat. While 50%-90% of patients with MCL respond to combination chemotherapy, only 30% achieve a complete response. Median time to treatment failure is < 18 months.

When selecting systemic treatment for patients with MCL, clinicians should consider the availability of clinical trials for subsets of patients, eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT), high-risk status (ie, blastoid MCL, high Ki-67% > 30%, or central nervous system involvement), age, and performance status. The addition of radiation to chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with limited-stage, nonbulky disease, although this has not been confirmed in large, randomized studies. Outside of clinical trials, the usual approach for frontline treatment of MCL is chemoimmunotherapy with/without autologous SCT and with/without maintenance therapy.

Available options for primary MCL therapy in patients who require systemic therapy include:

• Single alkylating agents

• CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone)

• CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [hydroxydaunorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone)

• Hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) with or without rituximab

• R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)

• Lenalidomide plus rituximab

• Hyper-CVAD with autologous SCT

Options for relapsed or refractory MCL include:

• R-hyper-CVAD

• Hyper-CVAD with or without rituximab followed by autologous SCT

• Nucleoside analogues and combinations

• Salvage chemotherapy combinations followed by autologous SCT

• Bortezomib

• Lenalidomide

• Ibrutinib

• Radioimmunotherapy

• Rituximab

• Rituximab and thalidomide combination

• Acalabrutinib

• High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or SCT

• Brexucabtagene autoleucel

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.