User login

Clinician practices to connect with patients

Background: As technology and medical advances improve patient care, physicians and patients have become more dissatisfied with their interactions and relationships. Practices are needed to improve the connection between physician and patient.

Study design: Mixed-methods.

Setting: Three diverse primary care settings (academic medical center, Veterans Affairs facility, federally qualified health center).

Synopsis: Initial evidence- and narrative-based practices were identified from a systematic literature review, clinical observations of primary care encounters, and qualitative discussions with physicians, patients, and nonmedical professionals. A three-round modified Delphi process was performed with experts representing different aspects of the patient-physician relationship.

Five recommended clinical practices were recognized to foster presence and meaningful connections with patients: 1. Prepare with intention (becoming familiar with the patient before you meet them); 2. Listen intently and completely (sit down, lean forward, and don’t interrupt, but listen); 3. Agree on what matters most (discover your patient’s goals and fit them into the visit); 4. Connect with the patient’s story (take notice of efforts by the patient and successes); 5. Explore emotional cues (be aware of your patient’s emotions). Limitations of this study include the use of convenience sampling for the qualitative research, lack of international diversity of the expert panelists, and the lack of validation of the five practices as a whole.

Bottom line: The five practices of prepare with intention, listen intently and completely, agree on what matters most, connect with the patient’s story, and explore emotional cues may improve the patient-physician connection.

Citation: Zulman DM et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70-81.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: As technology and medical advances improve patient care, physicians and patients have become more dissatisfied with their interactions and relationships. Practices are needed to improve the connection between physician and patient.

Study design: Mixed-methods.

Setting: Three diverse primary care settings (academic medical center, Veterans Affairs facility, federally qualified health center).

Synopsis: Initial evidence- and narrative-based practices were identified from a systematic literature review, clinical observations of primary care encounters, and qualitative discussions with physicians, patients, and nonmedical professionals. A three-round modified Delphi process was performed with experts representing different aspects of the patient-physician relationship.

Five recommended clinical practices were recognized to foster presence and meaningful connections with patients: 1. Prepare with intention (becoming familiar with the patient before you meet them); 2. Listen intently and completely (sit down, lean forward, and don’t interrupt, but listen); 3. Agree on what matters most (discover your patient’s goals and fit them into the visit); 4. Connect with the patient’s story (take notice of efforts by the patient and successes); 5. Explore emotional cues (be aware of your patient’s emotions). Limitations of this study include the use of convenience sampling for the qualitative research, lack of international diversity of the expert panelists, and the lack of validation of the five practices as a whole.

Bottom line: The five practices of prepare with intention, listen intently and completely, agree on what matters most, connect with the patient’s story, and explore emotional cues may improve the patient-physician connection.

Citation: Zulman DM et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70-81.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: As technology and medical advances improve patient care, physicians and patients have become more dissatisfied with their interactions and relationships. Practices are needed to improve the connection between physician and patient.

Study design: Mixed-methods.

Setting: Three diverse primary care settings (academic medical center, Veterans Affairs facility, federally qualified health center).

Synopsis: Initial evidence- and narrative-based practices were identified from a systematic literature review, clinical observations of primary care encounters, and qualitative discussions with physicians, patients, and nonmedical professionals. A three-round modified Delphi process was performed with experts representing different aspects of the patient-physician relationship.

Five recommended clinical practices were recognized to foster presence and meaningful connections with patients: 1. Prepare with intention (becoming familiar with the patient before you meet them); 2. Listen intently and completely (sit down, lean forward, and don’t interrupt, but listen); 3. Agree on what matters most (discover your patient’s goals and fit them into the visit); 4. Connect with the patient’s story (take notice of efforts by the patient and successes); 5. Explore emotional cues (be aware of your patient’s emotions). Limitations of this study include the use of convenience sampling for the qualitative research, lack of international diversity of the expert panelists, and the lack of validation of the five practices as a whole.

Bottom line: The five practices of prepare with intention, listen intently and completely, agree on what matters most, connect with the patient’s story, and explore emotional cues may improve the patient-physician connection.

Citation: Zulman DM et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70-81.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Hotspotting does not reduce readmissions

Background: In the United States, 5% of the population use half of the annual spending for health care services and 1% account for approximately a quarter of annual spending, considered “superutilizers” of U.S. health care services. The Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers (the Coalition) developed a model using hospital admission data to identify superutilizers, termed “hotspotting,” which has gained national recognition. Unlike other similar programs, this model targets a more diverse population with higher utilization than other programs that have been studied.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Two hospitals in Camden, N.J., from June 2, 2014, to March 31, 2018.

Synopsis: Eight-hundred superutilizers (at least one hospital admission at any of the four Camden-area hospital systems in the past 6 months, greater than one chronic medical condition, more than one high-risk traits/conditions) were randomly assigned to the intervention group or usual care. Once enrolled in the hospital, a multidisciplinary team began working with the patient in the intervention group on discharge. Team members conducted home visits, scheduled/took patients to appointments, managed medications, monitored and coached patients in disease-specific self-care, and assisted with applying for social and other assistive programs.

The readmission rate within 180 days after hospital discharge (primary outcome) between groups was not significant, with 62.3% readmitted in the intervention group and 61.7% in the control group. There was also no effect on the defined secondary outcomes (number of readmissions, proportion of patients with more than two readmissions, hospital days, charges, payments received, mortality).

The trial was not powered to detect smaller reductions in readmissions or to analyze effects within specific subgroups.

Bottom line: The addition of the Coalition’s program to patients with very high use of health care services did not decrease hospital readmission rate when compared to usual care.

Citation: Finkelstein A et al. Health care hotspotting – a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:152-62.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: In the United States, 5% of the population use half of the annual spending for health care services and 1% account for approximately a quarter of annual spending, considered “superutilizers” of U.S. health care services. The Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers (the Coalition) developed a model using hospital admission data to identify superutilizers, termed “hotspotting,” which has gained national recognition. Unlike other similar programs, this model targets a more diverse population with higher utilization than other programs that have been studied.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Two hospitals in Camden, N.J., from June 2, 2014, to March 31, 2018.

Synopsis: Eight-hundred superutilizers (at least one hospital admission at any of the four Camden-area hospital systems in the past 6 months, greater than one chronic medical condition, more than one high-risk traits/conditions) were randomly assigned to the intervention group or usual care. Once enrolled in the hospital, a multidisciplinary team began working with the patient in the intervention group on discharge. Team members conducted home visits, scheduled/took patients to appointments, managed medications, monitored and coached patients in disease-specific self-care, and assisted with applying for social and other assistive programs.

The readmission rate within 180 days after hospital discharge (primary outcome) between groups was not significant, with 62.3% readmitted in the intervention group and 61.7% in the control group. There was also no effect on the defined secondary outcomes (number of readmissions, proportion of patients with more than two readmissions, hospital days, charges, payments received, mortality).

The trial was not powered to detect smaller reductions in readmissions or to analyze effects within specific subgroups.

Bottom line: The addition of the Coalition’s program to patients with very high use of health care services did not decrease hospital readmission rate when compared to usual care.

Citation: Finkelstein A et al. Health care hotspotting – a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:152-62.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: In the United States, 5% of the population use half of the annual spending for health care services and 1% account for approximately a quarter of annual spending, considered “superutilizers” of U.S. health care services. The Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers (the Coalition) developed a model using hospital admission data to identify superutilizers, termed “hotspotting,” which has gained national recognition. Unlike other similar programs, this model targets a more diverse population with higher utilization than other programs that have been studied.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Two hospitals in Camden, N.J., from June 2, 2014, to March 31, 2018.

Synopsis: Eight-hundred superutilizers (at least one hospital admission at any of the four Camden-area hospital systems in the past 6 months, greater than one chronic medical condition, more than one high-risk traits/conditions) were randomly assigned to the intervention group or usual care. Once enrolled in the hospital, a multidisciplinary team began working with the patient in the intervention group on discharge. Team members conducted home visits, scheduled/took patients to appointments, managed medications, monitored and coached patients in disease-specific self-care, and assisted with applying for social and other assistive programs.

The readmission rate within 180 days after hospital discharge (primary outcome) between groups was not significant, with 62.3% readmitted in the intervention group and 61.7% in the control group. There was also no effect on the defined secondary outcomes (number of readmissions, proportion of patients with more than two readmissions, hospital days, charges, payments received, mortality).

The trial was not powered to detect smaller reductions in readmissions or to analyze effects within specific subgroups.

Bottom line: The addition of the Coalition’s program to patients with very high use of health care services did not decrease hospital readmission rate when compared to usual care.

Citation: Finkelstein A et al. Health care hotspotting – a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:152-62.

Dr. Trammell-Velasquez is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Lack of fever in ESRD with S. aureus bacteremia is common

Background: Fever is a common symptom in patients presenting to the ED. In patients with hemodialysis-dependent ESRD, the literature on febrile response during infection is scarce. In this study, authors compared ED triage temperatures of S. aureus bacteremic patients with and without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD.

Study design: Paired, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary care referral center.

Synopsis: A total of 74 patients with methicillin-resistant or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus bacteremia were included in this study (37 patients with and 37 patients without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD). Upon triage, 54% (95% confidence interval, 38%-70%) and 82% (95% CI, 65%-91%) of hemodialysis and nonhemodialysis patients did not have a detectable fever (less than 100.4° F), respectively. The estimated mean ED triage temperatures were 100.5° F in the hemodialysis-dependent patients and 99.0° F in the non–hemodialysis-dependent patients (P < .001). The authors note the significant lack of fevers may be the result of insensitive methods for measuring body temperature, such as peripheral thermometers.

Bottom line: In this small retrospective cohort study, these data suggest a high incidence of afebrile bacteremia in patients with ESRD, especially those patients not dialysis dependent. This may lead to delays in obtaining blood cultures and initiating antibiotics. However, given the study design, the authors were unable to conclude a causal relationship between ESRD and febrile response.

Citation: Weatherall SL et al. Do bacteremic patients with end-stage renal disease have a fever when presenting to the emergency department? A paired, retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20:2.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Fever is a common symptom in patients presenting to the ED. In patients with hemodialysis-dependent ESRD, the literature on febrile response during infection is scarce. In this study, authors compared ED triage temperatures of S. aureus bacteremic patients with and without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD.

Study design: Paired, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary care referral center.

Synopsis: A total of 74 patients with methicillin-resistant or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus bacteremia were included in this study (37 patients with and 37 patients without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD). Upon triage, 54% (95% confidence interval, 38%-70%) and 82% (95% CI, 65%-91%) of hemodialysis and nonhemodialysis patients did not have a detectable fever (less than 100.4° F), respectively. The estimated mean ED triage temperatures were 100.5° F in the hemodialysis-dependent patients and 99.0° F in the non–hemodialysis-dependent patients (P < .001). The authors note the significant lack of fevers may be the result of insensitive methods for measuring body temperature, such as peripheral thermometers.

Bottom line: In this small retrospective cohort study, these data suggest a high incidence of afebrile bacteremia in patients with ESRD, especially those patients not dialysis dependent. This may lead to delays in obtaining blood cultures and initiating antibiotics. However, given the study design, the authors were unable to conclude a causal relationship between ESRD and febrile response.

Citation: Weatherall SL et al. Do bacteremic patients with end-stage renal disease have a fever when presenting to the emergency department? A paired, retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20:2.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Fever is a common symptom in patients presenting to the ED. In patients with hemodialysis-dependent ESRD, the literature on febrile response during infection is scarce. In this study, authors compared ED triage temperatures of S. aureus bacteremic patients with and without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD.

Study design: Paired, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary care referral center.

Synopsis: A total of 74 patients with methicillin-resistant or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus bacteremia were included in this study (37 patients with and 37 patients without hemodialysis-dependent ESRD). Upon triage, 54% (95% confidence interval, 38%-70%) and 82% (95% CI, 65%-91%) of hemodialysis and nonhemodialysis patients did not have a detectable fever (less than 100.4° F), respectively. The estimated mean ED triage temperatures were 100.5° F in the hemodialysis-dependent patients and 99.0° F in the non–hemodialysis-dependent patients (P < .001). The authors note the significant lack of fevers may be the result of insensitive methods for measuring body temperature, such as peripheral thermometers.

Bottom line: In this small retrospective cohort study, these data suggest a high incidence of afebrile bacteremia in patients with ESRD, especially those patients not dialysis dependent. This may lead to delays in obtaining blood cultures and initiating antibiotics. However, given the study design, the authors were unable to conclude a causal relationship between ESRD and febrile response.

Citation: Weatherall SL et al. Do bacteremic patients with end-stage renal disease have a fever when presenting to the emergency department? A paired, retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20:2.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Conservative treatment for spontaneous pneumothorax?

Background: Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is usually with the insertion of a chest tube and typically requires hospitalization. This procedure can result in pain, organ injury, bleeding, and infection, and, if unresolved, may require surgery, introducing additional risks and complications. Few data exist from randomized trials comparing conservative versus interventional management.

Study design: Open-label, multicenter, prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial.

Setting: A total of 39 metropolitan and rural hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Overall, 316 patients with moderate to large primary spontaneous pneumothorax were randomized (154 to the intervention group and 162 in the conservative group). In the conservative group, 25 patients (15.4%) required eventual intervention for prespecified reasons (uncontrolled pain, chest pain or shortness of breath preventing mobilization, clinical instability, enlarging pneumothorax).

In complete-case analysis, 129 out of 131 (98.5%) patients in the intervention group had resolution within 8 weeks, compared with 118 of 125 (94.4%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –4.1 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, –8.6 to 0.5, P = .02 for noninferiority).

In sensitivity analysis, in which missing data after the 8-week period were imputed as treatment failures, re-expansion occurred in 129 out of 138 (93.5%) patients in the intervention group and 118 out of 143 (82.5%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –11.0 percentage points; 95% CI, –18.4 to –3.5), which is outside the noninferiority margin of –9.0.

Overall, 41 patients in the intervention group and 13 in the conservative group had at least one adverse event.

Bottom line: Missing data limit the ability to make strong conclusions, but this trial suggests that conservative management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax was noninferior to interventional management with lower risk of serious adverse events.

Citation: Brown SG et al. Conservative versus interventional treatment for spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:405-15.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is usually with the insertion of a chest tube and typically requires hospitalization. This procedure can result in pain, organ injury, bleeding, and infection, and, if unresolved, may require surgery, introducing additional risks and complications. Few data exist from randomized trials comparing conservative versus interventional management.

Study design: Open-label, multicenter, prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial.

Setting: A total of 39 metropolitan and rural hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Overall, 316 patients with moderate to large primary spontaneous pneumothorax were randomized (154 to the intervention group and 162 in the conservative group). In the conservative group, 25 patients (15.4%) required eventual intervention for prespecified reasons (uncontrolled pain, chest pain or shortness of breath preventing mobilization, clinical instability, enlarging pneumothorax).

In complete-case analysis, 129 out of 131 (98.5%) patients in the intervention group had resolution within 8 weeks, compared with 118 of 125 (94.4%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –4.1 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, –8.6 to 0.5, P = .02 for noninferiority).

In sensitivity analysis, in which missing data after the 8-week period were imputed as treatment failures, re-expansion occurred in 129 out of 138 (93.5%) patients in the intervention group and 118 out of 143 (82.5%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –11.0 percentage points; 95% CI, –18.4 to –3.5), which is outside the noninferiority margin of –9.0.

Overall, 41 patients in the intervention group and 13 in the conservative group had at least one adverse event.

Bottom line: Missing data limit the ability to make strong conclusions, but this trial suggests that conservative management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax was noninferior to interventional management with lower risk of serious adverse events.

Citation: Brown SG et al. Conservative versus interventional treatment for spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:405-15.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is usually with the insertion of a chest tube and typically requires hospitalization. This procedure can result in pain, organ injury, bleeding, and infection, and, if unresolved, may require surgery, introducing additional risks and complications. Few data exist from randomized trials comparing conservative versus interventional management.

Study design: Open-label, multicenter, prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial.

Setting: A total of 39 metropolitan and rural hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Overall, 316 patients with moderate to large primary spontaneous pneumothorax were randomized (154 to the intervention group and 162 in the conservative group). In the conservative group, 25 patients (15.4%) required eventual intervention for prespecified reasons (uncontrolled pain, chest pain or shortness of breath preventing mobilization, clinical instability, enlarging pneumothorax).

In complete-case analysis, 129 out of 131 (98.5%) patients in the intervention group had resolution within 8 weeks, compared with 118 of 125 (94.4%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –4.1 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, –8.6 to 0.5, P = .02 for noninferiority).

In sensitivity analysis, in which missing data after the 8-week period were imputed as treatment failures, re-expansion occurred in 129 out of 138 (93.5%) patients in the intervention group and 118 out of 143 (82.5%) in the conservative group (risk difference, –11.0 percentage points; 95% CI, –18.4 to –3.5), which is outside the noninferiority margin of –9.0.

Overall, 41 patients in the intervention group and 13 in the conservative group had at least one adverse event.

Bottom line: Missing data limit the ability to make strong conclusions, but this trial suggests that conservative management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax was noninferior to interventional management with lower risk of serious adverse events.

Citation: Brown SG et al. Conservative versus interventional treatment for spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:405-15.

Dr. Schmit is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Abnormal exercise EKG in the setting of normal stress echo linked with increased CV risk

Background: Exercise EKG is often integrated with stress echocardiography, but discordance with +EKG/–Echo has unknown significance.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Synopsis: 47,944 patients without known coronary artery disease underwent exercise stress echocardiogram (Echo) with stress EKG. Of those patients, 8.5% had +EKG/–Echo results, which was associated with annualized event rate of adverse cardiac events of 1.72%, which is higher than the 0.89% of patients with –EKG/–Echo results. This was most significant for composite major adverse cardiovascular events less than 30 days out, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 8.06 (95% confidence interval, 5.02-12.94). For major adverse cardiovascular events greater than 30 days out, HR was 1.25 (95% CI 1.02-1.53).

Bottom line: Patients with +EKG/–Echo findings appear to be at higher risk of adverse cardiac events, especially in the short term.

Citation: Daubert MA et al. Implications of abnormal exercise electrocardiography with normal stress echocardiography. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6958.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Exercise EKG is often integrated with stress echocardiography, but discordance with +EKG/–Echo has unknown significance.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Synopsis: 47,944 patients without known coronary artery disease underwent exercise stress echocardiogram (Echo) with stress EKG. Of those patients, 8.5% had +EKG/–Echo results, which was associated with annualized event rate of adverse cardiac events of 1.72%, which is higher than the 0.89% of patients with –EKG/–Echo results. This was most significant for composite major adverse cardiovascular events less than 30 days out, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 8.06 (95% confidence interval, 5.02-12.94). For major adverse cardiovascular events greater than 30 days out, HR was 1.25 (95% CI 1.02-1.53).

Bottom line: Patients with +EKG/–Echo findings appear to be at higher risk of adverse cardiac events, especially in the short term.

Citation: Daubert MA et al. Implications of abnormal exercise electrocardiography with normal stress echocardiography. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6958.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Exercise EKG is often integrated with stress echocardiography, but discordance with +EKG/–Echo has unknown significance.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Synopsis: 47,944 patients without known coronary artery disease underwent exercise stress echocardiogram (Echo) with stress EKG. Of those patients, 8.5% had +EKG/–Echo results, which was associated with annualized event rate of adverse cardiac events of 1.72%, which is higher than the 0.89% of patients with –EKG/–Echo results. This was most significant for composite major adverse cardiovascular events less than 30 days out, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 8.06 (95% confidence interval, 5.02-12.94). For major adverse cardiovascular events greater than 30 days out, HR was 1.25 (95% CI 1.02-1.53).

Bottom line: Patients with +EKG/–Echo findings appear to be at higher risk of adverse cardiac events, especially in the short term.

Citation: Daubert MA et al. Implications of abnormal exercise electrocardiography with normal stress echocardiography. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6958.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Post–acute kidney injury proteinuria predicts subsequent kidney disease progression

Background: Recent studies have shown that the level of proteinuria increases after AKI. It is not yet shown if this increases risk of kidney disease progression.

Study design: Prospective matched cohort study.

Setting: North American hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 769 hospitalized adults with AKI were matched with those without based on clinical center and preadmission chronic kidney disease (CKD) status. Study authors found that albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 3 months after hospitalization were highly associated with kidney disease progression, with a hazard ratio of 1.53 for each doubling (95% confidence interval, 1.43-1.64).

Episodes of AKI were also associated with progression, but this is severely attenuated once adjusted for ACR, eGFR, and traditional CKD risk factors. This suggests more routine quantification of proteinuria after AKI for better risk stratification.

Bottom line: Posthospitalization ACR predicts progression of kidney disease.

Citation: Hsu CY et al. Post–acute kidney injury proteinuria and subsequent kidney disease progression. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6390.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Recent studies have shown that the level of proteinuria increases after AKI. It is not yet shown if this increases risk of kidney disease progression.

Study design: Prospective matched cohort study.

Setting: North American hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 769 hospitalized adults with AKI were matched with those without based on clinical center and preadmission chronic kidney disease (CKD) status. Study authors found that albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 3 months after hospitalization were highly associated with kidney disease progression, with a hazard ratio of 1.53 for each doubling (95% confidence interval, 1.43-1.64).

Episodes of AKI were also associated with progression, but this is severely attenuated once adjusted for ACR, eGFR, and traditional CKD risk factors. This suggests more routine quantification of proteinuria after AKI for better risk stratification.

Bottom line: Posthospitalization ACR predicts progression of kidney disease.

Citation: Hsu CY et al. Post–acute kidney injury proteinuria and subsequent kidney disease progression. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6390.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: Recent studies have shown that the level of proteinuria increases after AKI. It is not yet shown if this increases risk of kidney disease progression.

Study design: Prospective matched cohort study.

Setting: North American hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 769 hospitalized adults with AKI were matched with those without based on clinical center and preadmission chronic kidney disease (CKD) status. Study authors found that albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 3 months after hospitalization were highly associated with kidney disease progression, with a hazard ratio of 1.53 for each doubling (95% confidence interval, 1.43-1.64).

Episodes of AKI were also associated with progression, but this is severely attenuated once adjusted for ACR, eGFR, and traditional CKD risk factors. This suggests more routine quantification of proteinuria after AKI for better risk stratification.

Bottom line: Posthospitalization ACR predicts progression of kidney disease.

Citation: Hsu CY et al. Post–acute kidney injury proteinuria and subsequent kidney disease progression. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6390.

Dr. Ho is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

FIND: A framework for success as a first-year hospitalist

Congratulations! You’re about to start your first year as a hospitalist, and in many cases your first real job. Hospital medicine is an incredibly rewarding subspecialty, but the progression from resident to attending physician can be daunting. To facilitate this transition, we present FIND (Familiarity, Identity, Network, and Direction) – a novel, sequential framework for success as a first-year hospitalist. For each component, we provide a narrative overview and a summary bullet point for quick reference.

Familiarity

- Lay the foundation: Learn the ins and outs of your job, EMR, and team.

Familiarize yourself with your surroundings. Know where your patients are located, where you can document, where to find equipment for procedures, and how to reach information technology. Proactively set up the electronic medical record on your home computer and phone. Make sure to review your responsibilities, including your call schedule, your shifts, your assigned patient panel, when you can leave campus, and how people should contact you. Also, others should know your expectations of them, especially if you are working with trainees.

Maintain a file with all of your orientation materials, including phone numbers and emails of key personnel. Know who your people are – who can access your calendar, who you can call with a clinical question or to escalate care, who can assist you with billing, and who helps with the throughput of your patients in the hospital. Take time to review your benefits, including parental leave, insurance coverage, retirement planning, vacation time, and ancillary services like laundry for your white coat. Familiarizing yourself with these basics will provide comfort and lay the foundation for your first year.

Identity

- Perform self-reflection: Overcome imposter syndrome and invest in hobbies.

One of the fundamental realizations that will occur with your first hospitalist job is that you are the attending. You walk in with a vision of your first job; be prepared to be surprised. You have earned the privilege of deciding on patient plans, and you are no longer obligated to staff with a senior physician. This is both empowering and terrifying. In a way, it may oddly remind you of intern year. A new hospital, new EMR, new colleagues, and imposter syndrome will trick you into doubting your decisions.

How to battle it? Positive thinking. You do know the basics of inpatient medicine and you do have a support system to cheer you on. As part of imposter syndrome, you may feel pressured to focus solely on work. Yet, your first job as a hospitalist is finally an amazing opportunity to focus on you. What hobbies have you been neglecting: cooking, photography, reading, more time with family, a new pet? You have the power to schedule your off-weeks. Are you interested in academics? Reserve a portion of your time off to explore scholarship opportunities at your institution. Your first job as a hospitalist is a chance to develop your identity, both as a physician and as an individual.

Network

- Engage your support system: Communicate with nursing, administration, colleagues.

Networking, or building a web of mutually beneficial professional relationships, is imperative for long-term career success. Hospitalists should focus on developing their network across multiple departments, such as nursing, subspecialties, medical education, and hospital administration. Curating a broad network will increase your visibility within your organization, showcase your unique services, and demonstrate your value.

To make networking encounters impactful, express interest, actively listen, ask relevant questions, and seek areas of mutual benefit. It’s equally important to cultivate these new relationships after the initial encounter and to demonstrate how your skill set will aid colleagues in achieving their professional goals. Over time, as you establish your niche, deliberate networking with those who share similar interests can lead to a wealth of new experiences and opportunities. Intentionally mastering networking early in your career provides insight into different aspects of the hospital system, new perspectives on ideas, and access to valuable guidance from other professionals. Engaging in networking to establish your support system is an essential step towards success as a first-year hospitalist.

Direction

- Visualize your path: Find a mentor and develop a mission statement and career plan.

Once you’re familiar with your work environment, confident in your identity, and acquainted with your support network, you’re ready for the final step – direction. Hospital medicine offers many professional avenues and clarifying your career path is challenging when attempted alone. A mentor is the necessary catalyst to find direction and purpose.

Selecting and engaging with a mentor will bolster your professional advancement, academic productivity, and most importantly, career satisfaction.1 At its best, mentorship is a symbiotic relationship. Your mentor should inspire you, challenge you, and support your growth and emotional well-being. In turn, as the mentee, you should be proactive, establish expectations, and take responsibility for maintaining communication to ensure a successful relationship. As your career takes shape over time, you may require a mentorship team to fulfill your unique needs.

When you’ve established a relationship with your mentor, take time to develop 1-year and 5-year plans. Your 1-year plan should focus on a few “quick wins,” often projects or opportunities at your home institution. Small victories in your first year will boost your confidence, motivation, and sense of control. Your 5-year plan should delineate the steps necessary to make your first major career transition, such as from instructor to assistant professor. Working with your mentor to draft a career mission statement is a useful first step in this process. Beginning with the end in mind, will help you visualize your direction.2

We hope that the FIND framework will help you find your path to success as a first-year hospitalist.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director, department of internal medicine/pediatrics, at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Crecelius is assistant professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training committee, which submits quarterly content to the Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early -career hospitalists.

References

1. Zerzan JT et al. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84:140-4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f.

2. Covey F. The seven habits of highly effective people. 25th anniversary edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013.

Congratulations! You’re about to start your first year as a hospitalist, and in many cases your first real job. Hospital medicine is an incredibly rewarding subspecialty, but the progression from resident to attending physician can be daunting. To facilitate this transition, we present FIND (Familiarity, Identity, Network, and Direction) – a novel, sequential framework for success as a first-year hospitalist. For each component, we provide a narrative overview and a summary bullet point for quick reference.

Familiarity

- Lay the foundation: Learn the ins and outs of your job, EMR, and team.

Familiarize yourself with your surroundings. Know where your patients are located, where you can document, where to find equipment for procedures, and how to reach information technology. Proactively set up the electronic medical record on your home computer and phone. Make sure to review your responsibilities, including your call schedule, your shifts, your assigned patient panel, when you can leave campus, and how people should contact you. Also, others should know your expectations of them, especially if you are working with trainees.

Maintain a file with all of your orientation materials, including phone numbers and emails of key personnel. Know who your people are – who can access your calendar, who you can call with a clinical question or to escalate care, who can assist you with billing, and who helps with the throughput of your patients in the hospital. Take time to review your benefits, including parental leave, insurance coverage, retirement planning, vacation time, and ancillary services like laundry for your white coat. Familiarizing yourself with these basics will provide comfort and lay the foundation for your first year.

Identity

- Perform self-reflection: Overcome imposter syndrome and invest in hobbies.

One of the fundamental realizations that will occur with your first hospitalist job is that you are the attending. You walk in with a vision of your first job; be prepared to be surprised. You have earned the privilege of deciding on patient plans, and you are no longer obligated to staff with a senior physician. This is both empowering and terrifying. In a way, it may oddly remind you of intern year. A new hospital, new EMR, new colleagues, and imposter syndrome will trick you into doubting your decisions.

How to battle it? Positive thinking. You do know the basics of inpatient medicine and you do have a support system to cheer you on. As part of imposter syndrome, you may feel pressured to focus solely on work. Yet, your first job as a hospitalist is finally an amazing opportunity to focus on you. What hobbies have you been neglecting: cooking, photography, reading, more time with family, a new pet? You have the power to schedule your off-weeks. Are you interested in academics? Reserve a portion of your time off to explore scholarship opportunities at your institution. Your first job as a hospitalist is a chance to develop your identity, both as a physician and as an individual.

Network

- Engage your support system: Communicate with nursing, administration, colleagues.

Networking, or building a web of mutually beneficial professional relationships, is imperative for long-term career success. Hospitalists should focus on developing their network across multiple departments, such as nursing, subspecialties, medical education, and hospital administration. Curating a broad network will increase your visibility within your organization, showcase your unique services, and demonstrate your value.

To make networking encounters impactful, express interest, actively listen, ask relevant questions, and seek areas of mutual benefit. It’s equally important to cultivate these new relationships after the initial encounter and to demonstrate how your skill set will aid colleagues in achieving their professional goals. Over time, as you establish your niche, deliberate networking with those who share similar interests can lead to a wealth of new experiences and opportunities. Intentionally mastering networking early in your career provides insight into different aspects of the hospital system, new perspectives on ideas, and access to valuable guidance from other professionals. Engaging in networking to establish your support system is an essential step towards success as a first-year hospitalist.

Direction

- Visualize your path: Find a mentor and develop a mission statement and career plan.

Once you’re familiar with your work environment, confident in your identity, and acquainted with your support network, you’re ready for the final step – direction. Hospital medicine offers many professional avenues and clarifying your career path is challenging when attempted alone. A mentor is the necessary catalyst to find direction and purpose.

Selecting and engaging with a mentor will bolster your professional advancement, academic productivity, and most importantly, career satisfaction.1 At its best, mentorship is a symbiotic relationship. Your mentor should inspire you, challenge you, and support your growth and emotional well-being. In turn, as the mentee, you should be proactive, establish expectations, and take responsibility for maintaining communication to ensure a successful relationship. As your career takes shape over time, you may require a mentorship team to fulfill your unique needs.

When you’ve established a relationship with your mentor, take time to develop 1-year and 5-year plans. Your 1-year plan should focus on a few “quick wins,” often projects or opportunities at your home institution. Small victories in your first year will boost your confidence, motivation, and sense of control. Your 5-year plan should delineate the steps necessary to make your first major career transition, such as from instructor to assistant professor. Working with your mentor to draft a career mission statement is a useful first step in this process. Beginning with the end in mind, will help you visualize your direction.2

We hope that the FIND framework will help you find your path to success as a first-year hospitalist.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director, department of internal medicine/pediatrics, at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Crecelius is assistant professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training committee, which submits quarterly content to the Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early -career hospitalists.

References

1. Zerzan JT et al. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84:140-4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f.

2. Covey F. The seven habits of highly effective people. 25th anniversary edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013.

Congratulations! You’re about to start your first year as a hospitalist, and in many cases your first real job. Hospital medicine is an incredibly rewarding subspecialty, but the progression from resident to attending physician can be daunting. To facilitate this transition, we present FIND (Familiarity, Identity, Network, and Direction) – a novel, sequential framework for success as a first-year hospitalist. For each component, we provide a narrative overview and a summary bullet point for quick reference.

Familiarity

- Lay the foundation: Learn the ins and outs of your job, EMR, and team.

Familiarize yourself with your surroundings. Know where your patients are located, where you can document, where to find equipment for procedures, and how to reach information technology. Proactively set up the electronic medical record on your home computer and phone. Make sure to review your responsibilities, including your call schedule, your shifts, your assigned patient panel, when you can leave campus, and how people should contact you. Also, others should know your expectations of them, especially if you are working with trainees.

Maintain a file with all of your orientation materials, including phone numbers and emails of key personnel. Know who your people are – who can access your calendar, who you can call with a clinical question or to escalate care, who can assist you with billing, and who helps with the throughput of your patients in the hospital. Take time to review your benefits, including parental leave, insurance coverage, retirement planning, vacation time, and ancillary services like laundry for your white coat. Familiarizing yourself with these basics will provide comfort and lay the foundation for your first year.

Identity

- Perform self-reflection: Overcome imposter syndrome and invest in hobbies.

One of the fundamental realizations that will occur with your first hospitalist job is that you are the attending. You walk in with a vision of your first job; be prepared to be surprised. You have earned the privilege of deciding on patient plans, and you are no longer obligated to staff with a senior physician. This is both empowering and terrifying. In a way, it may oddly remind you of intern year. A new hospital, new EMR, new colleagues, and imposter syndrome will trick you into doubting your decisions.

How to battle it? Positive thinking. You do know the basics of inpatient medicine and you do have a support system to cheer you on. As part of imposter syndrome, you may feel pressured to focus solely on work. Yet, your first job as a hospitalist is finally an amazing opportunity to focus on you. What hobbies have you been neglecting: cooking, photography, reading, more time with family, a new pet? You have the power to schedule your off-weeks. Are you interested in academics? Reserve a portion of your time off to explore scholarship opportunities at your institution. Your first job as a hospitalist is a chance to develop your identity, both as a physician and as an individual.

Network

- Engage your support system: Communicate with nursing, administration, colleagues.

Networking, or building a web of mutually beneficial professional relationships, is imperative for long-term career success. Hospitalists should focus on developing their network across multiple departments, such as nursing, subspecialties, medical education, and hospital administration. Curating a broad network will increase your visibility within your organization, showcase your unique services, and demonstrate your value.

To make networking encounters impactful, express interest, actively listen, ask relevant questions, and seek areas of mutual benefit. It’s equally important to cultivate these new relationships after the initial encounter and to demonstrate how your skill set will aid colleagues in achieving their professional goals. Over time, as you establish your niche, deliberate networking with those who share similar interests can lead to a wealth of new experiences and opportunities. Intentionally mastering networking early in your career provides insight into different aspects of the hospital system, new perspectives on ideas, and access to valuable guidance from other professionals. Engaging in networking to establish your support system is an essential step towards success as a first-year hospitalist.

Direction

- Visualize your path: Find a mentor and develop a mission statement and career plan.

Once you’re familiar with your work environment, confident in your identity, and acquainted with your support network, you’re ready for the final step – direction. Hospital medicine offers many professional avenues and clarifying your career path is challenging when attempted alone. A mentor is the necessary catalyst to find direction and purpose.

Selecting and engaging with a mentor will bolster your professional advancement, academic productivity, and most importantly, career satisfaction.1 At its best, mentorship is a symbiotic relationship. Your mentor should inspire you, challenge you, and support your growth and emotional well-being. In turn, as the mentee, you should be proactive, establish expectations, and take responsibility for maintaining communication to ensure a successful relationship. As your career takes shape over time, you may require a mentorship team to fulfill your unique needs.

When you’ve established a relationship with your mentor, take time to develop 1-year and 5-year plans. Your 1-year plan should focus on a few “quick wins,” often projects or opportunities at your home institution. Small victories in your first year will boost your confidence, motivation, and sense of control. Your 5-year plan should delineate the steps necessary to make your first major career transition, such as from instructor to assistant professor. Working with your mentor to draft a career mission statement is a useful first step in this process. Beginning with the end in mind, will help you visualize your direction.2

We hope that the FIND framework will help you find your path to success as a first-year hospitalist.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director, department of internal medicine/pediatrics, at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Crecelius is assistant professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training committee, which submits quarterly content to the Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early -career hospitalists.

References

1. Zerzan JT et al. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84:140-4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f.

2. Covey F. The seven habits of highly effective people. 25th anniversary edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013.

Fact or fiction? Intravascular contrast and acute kidney injury

Withholding contrast may be the greater risk

Case

A 73-year-old man with stage III chronic kidney disease (CKD) presents to the emergency department with acute left–upper quadrant pain. Serum creatinine is 2.1mg/dL (eGFR 30 mL/min). Noncontrast computed tomography of the abdomen identifies small bowel inflammation and extensive atherosclerosis. Acute mesenteric ischemia is suspected, but further characterization requires intravenous contrast–enhanced images. He and his family worry about the safety of IV contrast and ask to speak with you.

Introduction

Intravenous iodinated contrast material enhances tissue conspicuity in CT imaging and improves its diagnostic performance. Several case reports published in the 1950s suggested that IV administration of high-osmolality contrast provoked acute kidney injury. An ensuing series of studies associated contrast utilization with renal impairment and additional data extrapolated from cardiology arteriography studies further amplified these concerns.

Contrast media use is often cited as a leading cause of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury.1 The associated fear of causing renal impairment or provoking the need for dialysis frequently leads clinicians to forgo contrast-enhanced CT studies or settle for suboptimal noncontrast imaging even in situations where these tests are clearly indicated. The potential for inadequate imaging to contribute to incomplete, delayed, or incorrect diagnoses represents an ongoing patient safety issue.

A growing body of literature suggests the risks of contrast-associated acute kidney injury are overstated, implying the truer danger lies with inadequate imaging, not contrast media utilization. This review discusses the definitions, risks, and incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury, informed by these recent studies.

Overview of the data

Definitions of contrast-induced renal dysfunction vary in clinical studies and range from a creatinine rise of 0.5-1 mg per deciliter or a 25%-50% increase from baseline within 2-5 days following contrast administration. In 2012, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes working group proposed the term “contrast-associated acute kidney injury” (CA-AKI) and defined it as a plasma creatinine rise of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours of contrast exposure, a creatinine increase by a factor of 1.5 over baseline within 7 days of contrast administration, or a urinary volume less than 0.5 mg per kg of body weight within 6 hours of contrast exposure (AKI Network or “AKIN” criteria for CA-AKI).2 Owing in part to inconsistent definitions and partly because of multiple potential confounders, the true incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury is uncertain.

The pathogenesis of CA-AKI is incompletely understood, but proposed mechanisms include direct tubular cytotoxic effects; reductions in intrarenal blood flow from contrast material–provoked arteriolar vasoconstriction and contrast-induced increases in blood viscosity; and renal microvascular thrombosis.

Risk factors for CA-AKI overlap with those for acute kidney injury in general. These include CKD, concurrent nephrotoxic medication use, advancing age, diabetes, hemodynamic disturbances to include intravascular volume depletion, systemic illness, and rapid arterial delivery of a large contrast volume.

Current American College of Radiology guidelines state that intravenous isotonic crystalloid volume expansion prior to contrast administration may provide some renal protection, although randomized clinical trial results are inconsistent. The largest clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine showed rates of CA-AKI, need for dialysis, and mortality were no different than placebo. Studies of intravenous sodium bicarbonate show outcomes similar to normal saline.

Introduced in the 1950s and used until the early 2000s, the osmolality of high-osmolality contrast material (HOCM) is roughly five times that of blood (1551 mOsm/kg H2O).3 The early case reports first identifying concern for contrast-induced renal damage were of HOCM used in angiography and pyelography testing. Multiple follow up clinical studies measured creatinine levels before and after contrast administration and classified the percentage of patients whose creatinine level rose above an arbitrary definition of renal injury as having contrast-induced renal injury. These studies formed the basis of the now longstanding concerns about contrast-associated renal dysfunction. Importantly, very few of these HOCM studies included a control group.

Following multiple studies demonstrating an improved safety profile with a similar image quality, the Food and Drug Administration approved low-osmolality contrast (LOCM, 413-796mOsm/kg H2O) in 1985. Early adoption was slow because of its significantly higher cost and incomplete Medicare reimbursement. Prices fell following generic LOCM introduction in 1995 and in 2005 Medicare approved universal reimbursement, leading to widespread use. The FDA approved an iso-osmolality contrast material (290 mOsm/kg H2O) in the mid-1990s; its safety profile and image quality is similar to LOCM. Both LOCM and iso-osmolality contrast material are used in CTs today. Iso-osmolality contrast is more viscous than LOCM and is currently more expensive. Iso-osmolality and LOCM have similar rates of CA-AKI.

A clinical series published in 2008 examined serum creatinine level variation over 5 consecutive days in 30,000 predominantly hospitalized patients who did not receive intravenous contrast material. Investigators simulated contrast administration between days 1 and 2, then observed creatinine changes over the subsequent days. The incidence of acute kidney injury following the simulated contrast dose closely resembled the rates identified in earlier studies that associated contrast exposure with renal injury.4 These results suggested that changes in renal function commonly attributed to contrast exposure may be because of other, concurrent, clinical factors.

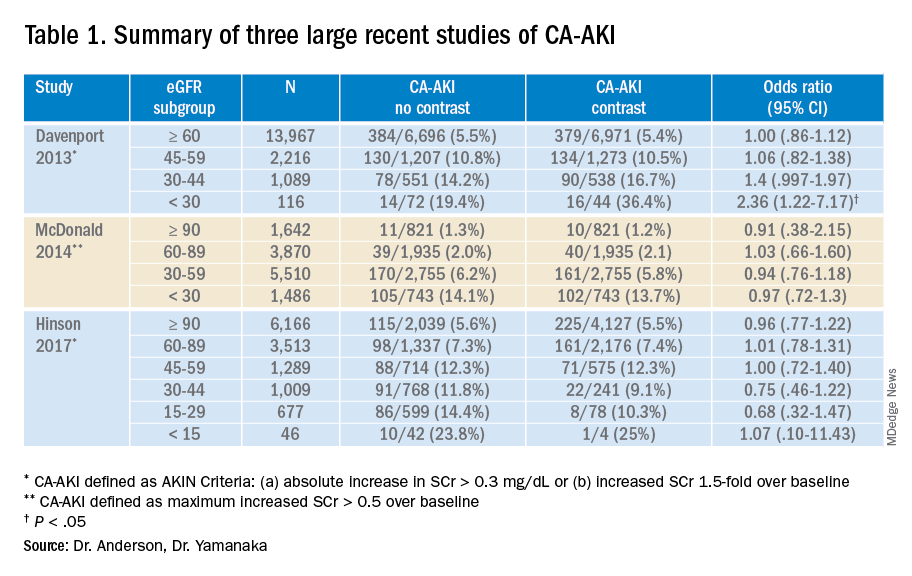

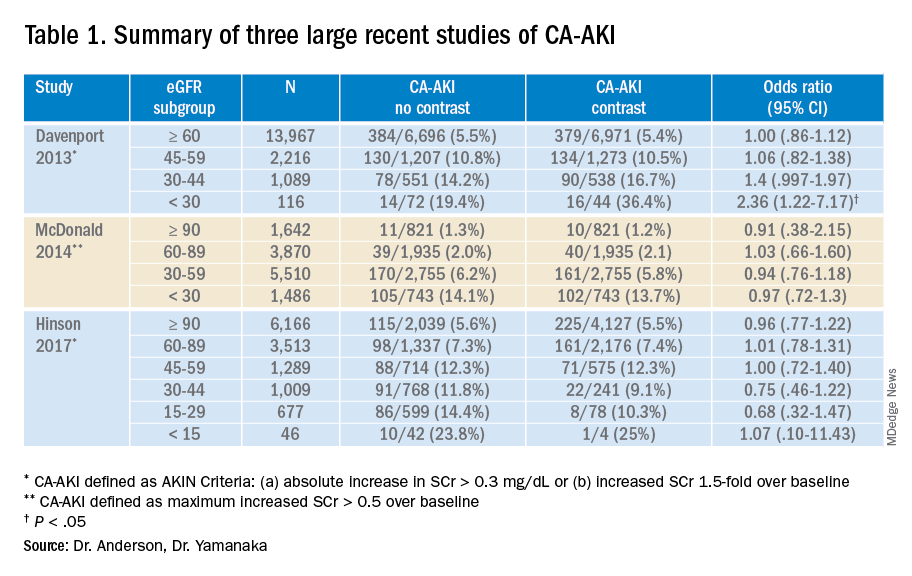

A 2013 study compared 8,826 patients with stable renal function who received a low-osmolality contrast-enhanced CT with 8,826 patients who underwent a noncontrast study.5 After 1:1 propensity matching, they found higher rates of CA-AKI (as defined by AKIN criteria) among only those with baseline eGFR less than 30 mL/min. There was a trend towards higher rates of CA-AKI among those with baseline eGFR of 30-44 mL/min, and no difference among the bulk of patients with normal or near normal baseline renal function.

Another large propensity score–matched study published in 2014 compared 6,254 patients who underwent a contrast-enhanced CT with 6,254 patients who underwent a nonenhanced CT.

Investigators stratified this predominantly inpatient cohort by baseline eGFR. Results demonstrated similar rates of AKI between contrast material and non–contrast material cohorts. They concluded that intravenous contrast administration did not significantly affect the risk of acute kidney injury, even in patients with impaired renal function. The authors noted that the difference in contrast-mediated nephrotoxic risk in patients with eGFRless than 30 between their study and the Davenport study could be explained by their use of a different definition of CA-AKI, differences in propensity score calculation, and by enrolling greater numbers of patients with impaired kidney function in their study.6

Finally, a large single-center study published in 2017 included 16,801 ED patients divided into three groups; patients who received a contrast-enhanced CT, patients who underwent a noncontrast CT study, and a set of patients who did not undergo any CT imaging. Patients with creatinine levels under .4 mg/dL or over 4 mg/dL were excluded from initial analysis.

Investigators stratified each patient group by serum creatinine and eGFR and utilized both traditional contrast-induced nephropathy (serum creatinine increase of .5 mg/dL or a 25% increase over baseline serum creatinine level at 48-72 hours) and AKIN criteria to evaluate for acute kidney injury. Propensity score analyses comparing the contrast-enhanced group and two control groups failed to identify any significant change in AKI incidence. The authors concluded that, in situations where contrast-enhanced CT is indicated to avoid missing or delaying potential diagnoses, the risks of diagnostic failure outweigh any potential risks of contrast induced renal injury.7

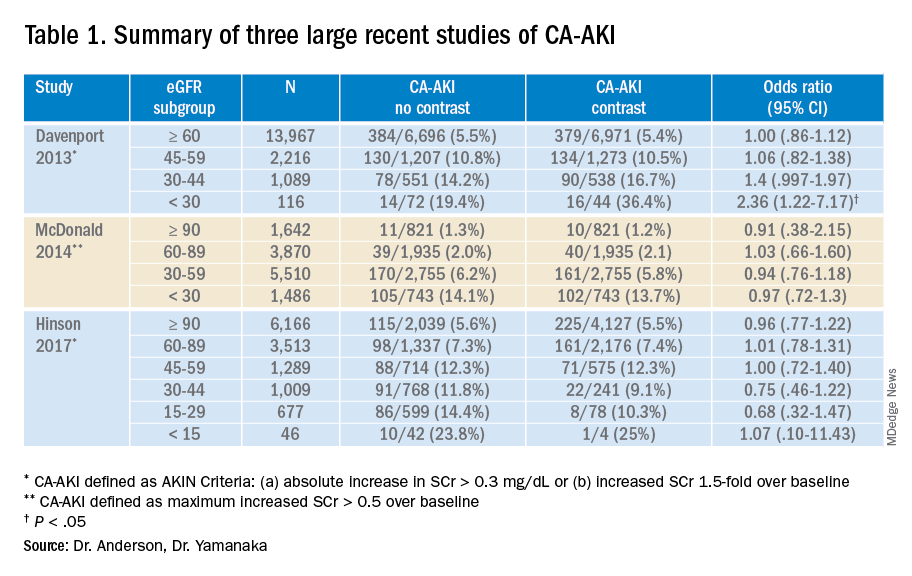

While these three studies utilized control groups and propensity score matching, they are retrospective in nature and unknown or omitted confounding variables could be present. Together, though, they contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting that the risk of contrast-associated AKI relates less to the contrast itself and more to concurrent clinical factors affecting kidney function. Ethical concerns have to date prevented the conduct of a randomized trial of IV contrast in CT scanning. Table 1 summarizes the findings of these three studies.

Application of the data to the case

The patient presented with abdominal pain potentially attributable to acute mesenteric ischemia, where a delayed or missed diagnosis can be potentially fatal. He was counseled about the comparatively small risk of CA-AKI with IV contrast and underwent contrast-enhanced CT scanning without incident. The diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia was confirmed, and he was referred for urgent laparotomy.

Bottom line

The absolute risk of CA-AKI varies according to baseline renal function and is not clearly linked to the receipt of IV contrast. The risks of withholding contrast may be greater than the risk of CA-AKI. Clinicians should counsel patients accordingly.

Dr. Anderson is national lead, VHA Hospital Medicine, and associate professor of medicine at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. Dr. Yamanaka is a hospitalist at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota.

References

1. Nash K et al. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):930-6. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766.

2. Section 4: Contrast-induced AKI. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):69-88. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2011.34.

3. Wilmot A et al. The adoption of low-osmolar contrast agents in the United States: Historical analysis of health policy and clinical practice. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(5):1049-53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8426.

4. Newhouse JH et al. Frequency of serum creatinine changes in the absence of iodinated contrast material: Implications for studies of contrast nephrotoxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(2):376-82. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3280.

5. Davenport MS et al. Contrast material-induced nephrotoxicity and intravenous low-osmolality iodinated contrast material: Risk stratification by using estimated glomerular filtration rate. Radiology. 2013;268(3):719-28. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122276.

6. McDonald JS et al. Risk of intravenous contrast material-mediated acute kidney injury: A propensity score–matched study stratified by baseline-estimated glomerular filtration rate. Radiology. 2014;271(1):65-73. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130775.

7. Hinson JS et al. Risk of acute kidney injury after intravenous contrast media administration. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):577-86. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.11.021.

Key points

- Early studies suggesting an association between IV contrast and AKI used an older formulation of contrast media not routinely used today. Importantly, these studies did not use control groups.

- Results from multiple recent large trials comparing IV contrast patients with controls suggest that AKI is not clearly linked to the receipt of IV contrast and that it varies according to baseline renal function.

- Randomized controlled trials of prophylactic normal saline or sodium bicarbonate to prevent CA-AKI show mixed results. Clinical trials comparing N-acetylcysteine with placebo showed no difference in the rates of AKI, dialysis initiation, or mortality.

Quiz

Which of the following is not clearly associated with acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients?

A. Decreased baseline glomerular filtration rate

B. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor use

C. Hemodynamic instability

D. Intravenous contrast administration

Answer: D

While decreased baseline renal function, ACE inhibitors, and hemodynamic instability are known risk factors for hospital-associated renal injury, a growing body of literature suggests that intravenous contrast used in computed tomography studies does not precipitate acute kidney injury.

Further reading

McDonald JS et al. Frequency of acute kidney injury following intravenous contrast medium administration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2013;267(1):119-128. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12121460.

McDonald RJ et al. Behind the numbers: Propensity score analysis – a primer for the diagnostic radiologist. Radiology. 2013;269(3):640-5. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131465.

Luk L et al. Intravenous contrast-induced nephropathy – the rise and fall of a threatening idea. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(3):169-75. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.03.001.

Mehran R et al. Contrast-associated acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2146-55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1805256.

Withholding contrast may be the greater risk

Withholding contrast may be the greater risk

Case

A 73-year-old man with stage III chronic kidney disease (CKD) presents to the emergency department with acute left–upper quadrant pain. Serum creatinine is 2.1mg/dL (eGFR 30 mL/min). Noncontrast computed tomography of the abdomen identifies small bowel inflammation and extensive atherosclerosis. Acute mesenteric ischemia is suspected, but further characterization requires intravenous contrast–enhanced images. He and his family worry about the safety of IV contrast and ask to speak with you.

Introduction

Intravenous iodinated contrast material enhances tissue conspicuity in CT imaging and improves its diagnostic performance. Several case reports published in the 1950s suggested that IV administration of high-osmolality contrast provoked acute kidney injury. An ensuing series of studies associated contrast utilization with renal impairment and additional data extrapolated from cardiology arteriography studies further amplified these concerns.

Contrast media use is often cited as a leading cause of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury.1 The associated fear of causing renal impairment or provoking the need for dialysis frequently leads clinicians to forgo contrast-enhanced CT studies or settle for suboptimal noncontrast imaging even in situations where these tests are clearly indicated. The potential for inadequate imaging to contribute to incomplete, delayed, or incorrect diagnoses represents an ongoing patient safety issue.

A growing body of literature suggests the risks of contrast-associated acute kidney injury are overstated, implying the truer danger lies with inadequate imaging, not contrast media utilization. This review discusses the definitions, risks, and incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury, informed by these recent studies.

Overview of the data

Definitions of contrast-induced renal dysfunction vary in clinical studies and range from a creatinine rise of 0.5-1 mg per deciliter or a 25%-50% increase from baseline within 2-5 days following contrast administration. In 2012, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes working group proposed the term “contrast-associated acute kidney injury” (CA-AKI) and defined it as a plasma creatinine rise of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours of contrast exposure, a creatinine increase by a factor of 1.5 over baseline within 7 days of contrast administration, or a urinary volume less than 0.5 mg per kg of body weight within 6 hours of contrast exposure (AKI Network or “AKIN” criteria for CA-AKI).2 Owing in part to inconsistent definitions and partly because of multiple potential confounders, the true incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury is uncertain.

The pathogenesis of CA-AKI is incompletely understood, but proposed mechanisms include direct tubular cytotoxic effects; reductions in intrarenal blood flow from contrast material–provoked arteriolar vasoconstriction and contrast-induced increases in blood viscosity; and renal microvascular thrombosis.

Risk factors for CA-AKI overlap with those for acute kidney injury in general. These include CKD, concurrent nephrotoxic medication use, advancing age, diabetes, hemodynamic disturbances to include intravascular volume depletion, systemic illness, and rapid arterial delivery of a large contrast volume.

Current American College of Radiology guidelines state that intravenous isotonic crystalloid volume expansion prior to contrast administration may provide some renal protection, although randomized clinical trial results are inconsistent. The largest clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine showed rates of CA-AKI, need for dialysis, and mortality were no different than placebo. Studies of intravenous sodium bicarbonate show outcomes similar to normal saline.

Introduced in the 1950s and used until the early 2000s, the osmolality of high-osmolality contrast material (HOCM) is roughly five times that of blood (1551 mOsm/kg H2O).3 The early case reports first identifying concern for contrast-induced renal damage were of HOCM used in angiography and pyelography testing. Multiple follow up clinical studies measured creatinine levels before and after contrast administration and classified the percentage of patients whose creatinine level rose above an arbitrary definition of renal injury as having contrast-induced renal injury. These studies formed the basis of the now longstanding concerns about contrast-associated renal dysfunction. Importantly, very few of these HOCM studies included a control group.

Following multiple studies demonstrating an improved safety profile with a similar image quality, the Food and Drug Administration approved low-osmolality contrast (LOCM, 413-796mOsm/kg H2O) in 1985. Early adoption was slow because of its significantly higher cost and incomplete Medicare reimbursement. Prices fell following generic LOCM introduction in 1995 and in 2005 Medicare approved universal reimbursement, leading to widespread use. The FDA approved an iso-osmolality contrast material (290 mOsm/kg H2O) in the mid-1990s; its safety profile and image quality is similar to LOCM. Both LOCM and iso-osmolality contrast material are used in CTs today. Iso-osmolality contrast is more viscous than LOCM and is currently more expensive. Iso-osmolality and LOCM have similar rates of CA-AKI.

A clinical series published in 2008 examined serum creatinine level variation over 5 consecutive days in 30,000 predominantly hospitalized patients who did not receive intravenous contrast material. Investigators simulated contrast administration between days 1 and 2, then observed creatinine changes over the subsequent days. The incidence of acute kidney injury following the simulated contrast dose closely resembled the rates identified in earlier studies that associated contrast exposure with renal injury.4 These results suggested that changes in renal function commonly attributed to contrast exposure may be because of other, concurrent, clinical factors.

A 2013 study compared 8,826 patients with stable renal function who received a low-osmolality contrast-enhanced CT with 8,826 patients who underwent a noncontrast study.5 After 1:1 propensity matching, they found higher rates of CA-AKI (as defined by AKIN criteria) among only those with baseline eGFR less than 30 mL/min. There was a trend towards higher rates of CA-AKI among those with baseline eGFR of 30-44 mL/min, and no difference among the bulk of patients with normal or near normal baseline renal function.

Another large propensity score–matched study published in 2014 compared 6,254 patients who underwent a contrast-enhanced CT with 6,254 patients who underwent a nonenhanced CT.

Investigators stratified this predominantly inpatient cohort by baseline eGFR. Results demonstrated similar rates of AKI between contrast material and non–contrast material cohorts. They concluded that intravenous contrast administration did not significantly affect the risk of acute kidney injury, even in patients with impaired renal function. The authors noted that the difference in contrast-mediated nephrotoxic risk in patients with eGFRless than 30 between their study and the Davenport study could be explained by their use of a different definition of CA-AKI, differences in propensity score calculation, and by enrolling greater numbers of patients with impaired kidney function in their study.6

Finally, a large single-center study published in 2017 included 16,801 ED patients divided into three groups; patients who received a contrast-enhanced CT, patients who underwent a noncontrast CT study, and a set of patients who did not undergo any CT imaging. Patients with creatinine levels under .4 mg/dL or over 4 mg/dL were excluded from initial analysis.

Investigators stratified each patient group by serum creatinine and eGFR and utilized both traditional contrast-induced nephropathy (serum creatinine increase of .5 mg/dL or a 25% increase over baseline serum creatinine level at 48-72 hours) and AKIN criteria to evaluate for acute kidney injury. Propensity score analyses comparing the contrast-enhanced group and two control groups failed to identify any significant change in AKI incidence. The authors concluded that, in situations where contrast-enhanced CT is indicated to avoid missing or delaying potential diagnoses, the risks of diagnostic failure outweigh any potential risks of contrast induced renal injury.7

While these three studies utilized control groups and propensity score matching, they are retrospective in nature and unknown or omitted confounding variables could be present. Together, though, they contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting that the risk of contrast-associated AKI relates less to the contrast itself and more to concurrent clinical factors affecting kidney function. Ethical concerns have to date prevented the conduct of a randomized trial of IV contrast in CT scanning. Table 1 summarizes the findings of these three studies.

Application of the data to the case

The patient presented with abdominal pain potentially attributable to acute mesenteric ischemia, where a delayed or missed diagnosis can be potentially fatal. He was counseled about the comparatively small risk of CA-AKI with IV contrast and underwent contrast-enhanced CT scanning without incident. The diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia was confirmed, and he was referred for urgent laparotomy.

Bottom line

The absolute risk of CA-AKI varies according to baseline renal function and is not clearly linked to the receipt of IV contrast. The risks of withholding contrast may be greater than the risk of CA-AKI. Clinicians should counsel patients accordingly.

Dr. Anderson is national lead, VHA Hospital Medicine, and associate professor of medicine at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. Dr. Yamanaka is a hospitalist at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota.

References

1. Nash K et al. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):930-6. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766.

2. Section 4: Contrast-induced AKI. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):69-88. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2011.34.

3. Wilmot A et al. The adoption of low-osmolar contrast agents in the United States: Historical analysis of health policy and clinical practice. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(5):1049-53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8426.

4. Newhouse JH et al. Frequency of serum creatinine changes in the absence of iodinated contrast material: Implications for studies of contrast nephrotoxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(2):376-82. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3280.