User login

Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality in patients with pneumonia

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Pharmacologic and electrical cardioversion of acute Afib reduces hospital admissions

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Treatment of opioid use disorder with buprenorphine and methadone effective but underutilized

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Disconnect between POLST orders and end-of-life care

Background: In order to reduce the mismatch between patients’ desired and actual end-of-life care, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) was created. POLST is a portable document delineating medical orders for emergency care treatment at the end of life including whether to attempt resuscitation and general level of medical interventions. For nursing home residents, an association between POLST creation and reduction of unwanted CPR has been substantiated. Outside of this population, the association is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Patients older than age 18 years who had one of nine chronic health conditions associated with 90% of deaths among Medicare beneficiaries were identified using Washington state death certificates. Additional inclusion criteria included hospital admission in the last 6 months of life and creation of a POLST prior to this admission. This led to identification of 1,818 patients. Patients with full-treatment POLST orders were significantly more likely to be admitted to the ICU as well as receive life-sustaining treatments such as mechanical ventilation, vasoactive infusions, or CPR, compared with patients with limited interventions or comfort-only POLST orders (P < .001 for both). 38% of patients with treatment-limiting POLSTs received aggressive end-of-life care that was discordant with their previously documented wishes.

Bottom line: Completion of POLST was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving end-of-life care that was in line with patients’ previously documented wishes regarding admission to ICU and life-sustaining treatment. Washington was one of the first states to adopt POLST in 2005 and therefore these results may not be broadly applicable.

Citation: Lee RY et al. Association of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment with ICU admission among patients hospitalized hear the end of life. JAMA. 2020 Feb 16;323(10):950-60.

Dr. Dreicer is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: In order to reduce the mismatch between patients’ desired and actual end-of-life care, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) was created. POLST is a portable document delineating medical orders for emergency care treatment at the end of life including whether to attempt resuscitation and general level of medical interventions. For nursing home residents, an association between POLST creation and reduction of unwanted CPR has been substantiated. Outside of this population, the association is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Patients older than age 18 years who had one of nine chronic health conditions associated with 90% of deaths among Medicare beneficiaries were identified using Washington state death certificates. Additional inclusion criteria included hospital admission in the last 6 months of life and creation of a POLST prior to this admission. This led to identification of 1,818 patients. Patients with full-treatment POLST orders were significantly more likely to be admitted to the ICU as well as receive life-sustaining treatments such as mechanical ventilation, vasoactive infusions, or CPR, compared with patients with limited interventions or comfort-only POLST orders (P < .001 for both). 38% of patients with treatment-limiting POLSTs received aggressive end-of-life care that was discordant with their previously documented wishes.

Bottom line: Completion of POLST was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving end-of-life care that was in line with patients’ previously documented wishes regarding admission to ICU and life-sustaining treatment. Washington was one of the first states to adopt POLST in 2005 and therefore these results may not be broadly applicable.

Citation: Lee RY et al. Association of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment with ICU admission among patients hospitalized hear the end of life. JAMA. 2020 Feb 16;323(10):950-60.

Dr. Dreicer is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: In order to reduce the mismatch between patients’ desired and actual end-of-life care, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) was created. POLST is a portable document delineating medical orders for emergency care treatment at the end of life including whether to attempt resuscitation and general level of medical interventions. For nursing home residents, an association between POLST creation and reduction of unwanted CPR has been substantiated. Outside of this population, the association is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Patients older than age 18 years who had one of nine chronic health conditions associated with 90% of deaths among Medicare beneficiaries were identified using Washington state death certificates. Additional inclusion criteria included hospital admission in the last 6 months of life and creation of a POLST prior to this admission. This led to identification of 1,818 patients. Patients with full-treatment POLST orders were significantly more likely to be admitted to the ICU as well as receive life-sustaining treatments such as mechanical ventilation, vasoactive infusions, or CPR, compared with patients with limited interventions or comfort-only POLST orders (P < .001 for both). 38% of patients with treatment-limiting POLSTs received aggressive end-of-life care that was discordant with their previously documented wishes.

Bottom line: Completion of POLST was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving end-of-life care that was in line with patients’ previously documented wishes regarding admission to ICU and life-sustaining treatment. Washington was one of the first states to adopt POLST in 2005 and therefore these results may not be broadly applicable.

Citation: Lee RY et al. Association of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment with ICU admission among patients hospitalized hear the end of life. JAMA. 2020 Feb 16;323(10):950-60.

Dr. Dreicer is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

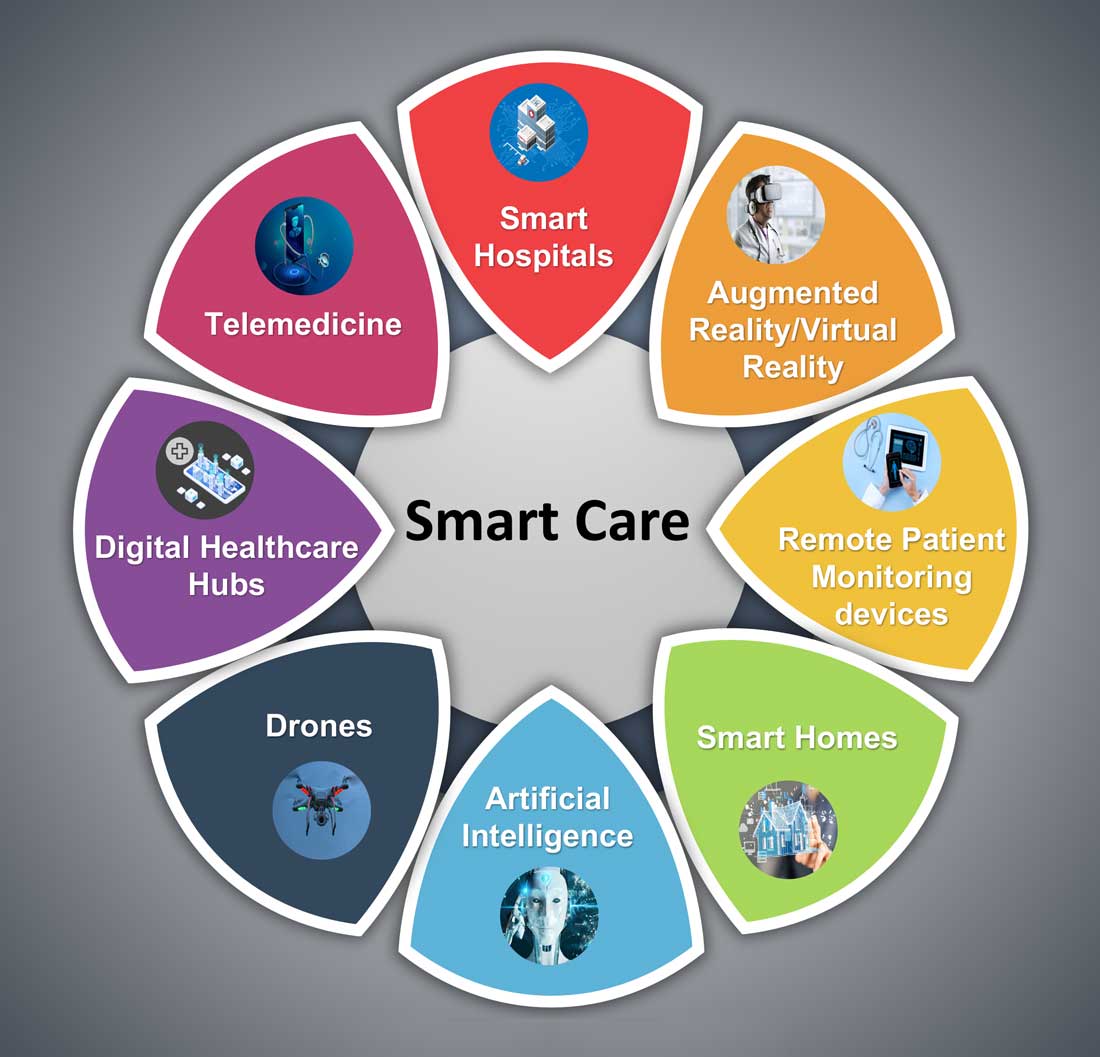

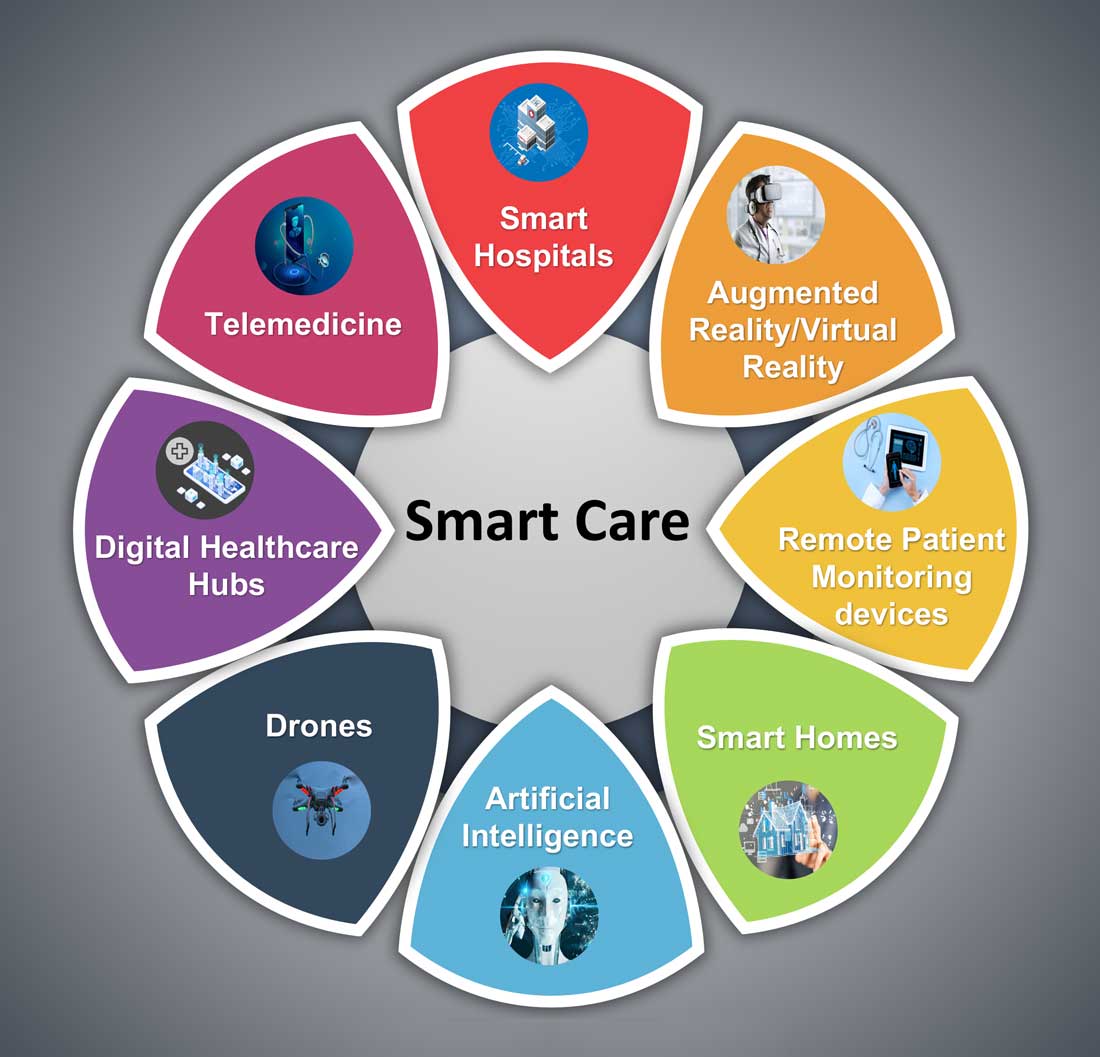

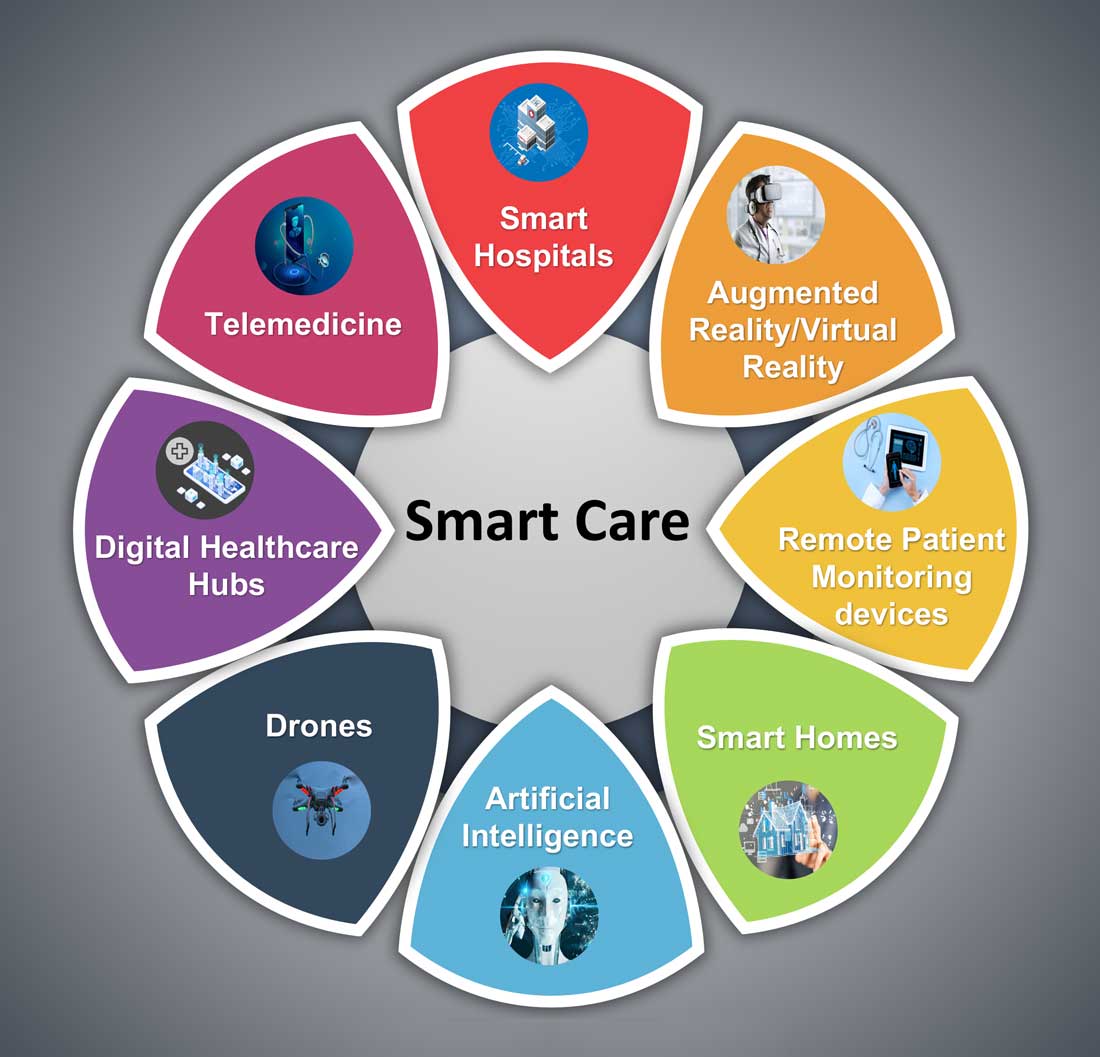

Hospital medicine and the future of smart care

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

“Enough English” to be at risk

A hectic Friday morning at the hospital seemed less stressful amid morning greetings and humor from colleagues. In a team room full of hospitalists, life and death are often discussed in detail, ranging from medical discussions to joys and frustrations of the day to philosophy, politics, and more. It is almost impossible to miss something interesting.

People breaking into their native languages over the phone call from home always make me smile. The mention of a “complicated Indian patient unable to use interpreter” caught my attention.

My friend and colleague asked if I would be willing to take over the patient since I could speak Hindi. I was doubtful if I would add anything to make a meaningful difference, given the patient wasn’t even participating in a conversation. However, my colleague’s concern for the patient and faith in me was enough to say, “Sure, let me add her to my list.”

At the bedside, it felt like a classic “acute on chronic” hot mess situation. The patient presented with a generalized rash, anasarca, renal failure, multifocal pneumonia, and delirium. All I could gather from the patient were some incomprehensible words that sounded like Hindi. I called the family to obtain some history and to provide updates. Her son was excited to hear from me, and it didn’t take him long to guess that I was from India. But that could still mean that I might speak any of the twenty-two or more Indian languages.

Answering my questions one by one in perfectly understandable English, he was short and sweet. Suspicious of missing out on details, I offered hesitantly, “You could speak in Hindi with me.” Then came a flood of information with the details, concerns, questions, and what was lost in the translation.

We all attend to patients and families with limited English proficiency (LEP), immigrants, and nonimmigrants. LEP is a term used to describe individuals who do not speak English as their primary language and have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English.1 Recent data from the American Community Survey (2005-2009) reports that 8.6% of the population (24 million Americans) have LEP.2 It’s a large and growing population that needs help overcoming language barriers and the appropriate use of professional medical interpreter services – a backbone to safe, quality, and cost-effective patient care.

The following day at bedside rounds, the nurse reported that the patient was looking and responding better. She could cooperate with interpreter services and could speak “some English.” Over the years, one thing that sounds more alarming than “no English” is “some English” or “enough English.” Around noon I received a page that the patient was refusing intravenous Lasix. At the bedside, however, the patient seemed unaware of the perceived refusal. Further discussions with the nurse lead to a familiar culprit, a relatively common gesture in South Asian cultures, a head bobble or shake.

The nurse reported that the patient shook her head side to side, seemed upset, and said “NO” when trying to administer the medication. On the other hand, the patient reported that she was upset to be at the hospital but had “NO” problem with the medicine.

My patient’s “some English” was indeed “enough English” to put her at risk due to medical error, which is highly likely when patients or providers can speak or understand a language to “get by” or to “make do.” Like my patient, the LEP patient population is more likely to experience medical errors, longer hospital stays, hospital-acquired complications, surgical delays, and readmissions. They are also less likely to receive preventive care, have access to regular care, or be satisfied with their care. They are much more likely to have adverse effects from drug complications, poor understanding of diagnoses, a greater risk of being misunderstood by their physicians or ancillary staff, and less likely to follow physician instructions.3-5 One study analyzed over 1,000 adverse-incident reports from six Joint Commission-accredited hospitals for LEP and English-speaking patients and found that 49% of LEP patients experienced physical harm versus 29.5% of English-speaking patients.6

I updated the patient’s LEP status that was missing in the chart, likely due to altered mental status at the time of admission. Reliable language and English proficiency data are usually entered at the patient’s point of entry with documentation of the language services required during the patient-provider encounter. The U.S. Census Bureau’s operational definition for LEP is a patient’s self-assessed ability to speak English less than “very well,” but how well it correlates with a patient’s actual English ability needs more study. Also, one’s self-assessed perception of ability might vary day to day, and language ability, by itself, is not static; it can differ from moment to moment and situation to situation. It may be easier to understand words in English when the situation is simple and less stressful than when things are complicated and stressful.

With a definition of LEP rather vague and the term somewhat derogatory, its meaning is open to interpretation. One study found that though speaking English less than “very well” was the most sensitive measure for identifying all of the patients who reported that they were unable to communicate effectively with their physicians, it was also the least specific.7 This lower specificity could lead to misclassification of some patients as LEP who are, in fact, able to effectively communicate in English with their physicians. This type of misclassification might lead to costly language assistance and carry the potential to cause conflicts between patient and provider. Telling a patient or family that they may have a “limited English proficiency” when they have believed otherwise and feel confident about their skills may come as a challenge. Some patients may also pretend to understand English to avoid being embarrassed about their linguistic abilities or perceive that they might be judged on their abilities in general.

Exiting the room, I gently reminded the RN to use the interpreter services. “Who has never been guilty of using an ad hoc interpreter or rushing through a long interpreter phone call due to time constraints?” I thought. A study from 2011 found that 43% of hospitalized patients with LEP had communicated without an interpreter present during admission, and 40% had communicated without an interpreter present after admission.8 In other words, a system in place does not mean service in use. But, the use of a trained interpreter is not only an obligation for care providers but a right for patients as per legal requirements of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and the Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) by the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HSS) Office of Minority Health.9 In January 2010, The Joint Commission released a set of new and revised standards for patient-centered communication as part of an initiative to advance effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care.

Despite the requirements and availability of qualified medical interpreter services, there are multiple perceived and experienced barriers to the use of interpreter services. The most common one is that what comes as a free service for patients is a time commitment for providers. A long list of patients, acuity of the situation, and ease of use/availability of translation aids can change the calculus. One may be able to bill a prolonged service code (99354-99357) in addition to the appropriate E/M code, although a patient cannot be billed for the actual service provided by the interpreter. Longstanding CMS policy also permits reimbursement for translation/interpretation activities, so long as they are not included and paid for as part of the rate for direct service.10

The patient, however, insisted that she would rather have her son as the interpreter on the 3-way over the phone (OPI) conference call for interpretation. “He speaks good English and knows my medical history well,” she said. I counseled the patient on the benefits of using interpreter services and explained how to use the call button light and the visual aids.

Placing emphasis on educating patients about the benefits of using, and risks of not using, interpreter services is as essential as emphasizing that care providers use the services. Some patients may voluntarily choose to provide their own interpreter. Use of family members, friends, or unqualified staff as interpreters is one of the most commonly reported causes of errors by frontline staff. Using in-language collateral may help these patients understand how medical interpretation may create a better patient experience and outcome. A short factsheet, in different languages, on qualified interpreters’ expected benefits: meaning-for-meaning communication, impartiality, medical privacy, and improved patient safety and satisfaction, can also come in handy.

However, if the patient still refuses, providers should document the refusal of the offer of free language services, the name of the interpreter designated by the patient, the interpreter’s relationship to the LEP person, and the time or portions of the patient encounter that the interpreter’s services were used. Yet, language interpretation alone can be inadequate without document translation. According to one study, despite the availability of on-site professional interpreter services, hospitalized patients who do not speak English are less likely to have signed consent forms in their medical records.11 Health care professionals, therefore, need well-translated documents to treat LEP patients. Translated documents of consent forms for medical procedures, post-discharge instructions, prescription and medical device labels, and drug usage information may enhance informed decision making, safety and reduce stress and medical errors.

An unpopular and underused service needs it all: availability, convenience, monitoring, reporting, and team effort. Due to the sheer unpopularity and underuse of interpreter services, institutions should enhance ease of availability, monitor the use and quality of interpreter services, and optimize reporting of language-related errors. Ease of availability goes hand in hand with tapping local resources. Over the years, and even more so during the pandemic, in-person interpretation has transitioned to telephonic or video interpretation due to availability, safety, and cost issues. There are challenges in translating a language, and the absence of a visual channel adds another layer of complexity.

The current body of evidence does not indicate a superior interpreting method. Still, in one study providers and interpreters exposed to all three methods were more critical of remote methods and preferred videoconferencing to the telephone as a remote method. The significantly shorter phone interviews raised questions about the prospects of miscommunication in telephonic interpretation, given the absence of a visual channel.12

One way to bypass language barriers is to recognize the value added by hiring and training bilingual health care providers and fostering cultural competence. International medical graduates in many parts of the country aid in closing language barriers. Language-concordant care enhances trust between patients and physicians, optimizes health outcomes, and advances health equity for diverse populations.13-15 The presence of bilingual providers means more effective and timelier communication and improved patient satisfaction. But, according to a Doximity study, there is a significant “language gap” between those languages spoken by physicians and their patients.16 Hospitals, therefore, should assess, qualify, and incentivize staff who can serve as on-site medical interpreters for patients as a means to facilitate language concordant care for LEP patients.

The Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also has a guide on how hospitals can better identify, report, monitor, and prevent medical errors in patients with LEP. Included is the TeamSTEPPS LEP module to help develop and deploy a customized plan to train staff in teamwork skills and lead a medical teamwork improvement initiative.17

“Without my family, I was scared that nobody would understand me”

Back to the case. My patient was recovering well, and I was tying up loose ends on the switch day for the hospitalist teams.

“You will likely be discharged in a couple of days,” I said. She and the family were grateful and satisfied with the care. She had used the interpreter services and also received ethnocultural and language concordant and culturally competent care. Reducing language barriers is one of the crucial ways to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in quality of care and health outcomes, and it starts – in many cases – with identifying LEP patients. Proper use and monitoring of interpreter services, reporting language-related errors, hiring and testing bilingual staff’s language proficiency, and educating staff on cultural awareness are essential strategies for caring for LEP patients.

At my weeks’ end, in my handoff note to the incoming providers, I highlighted: “Patient will benefit from a Hindi speaking provider, Limited English Proficiency.”

Dr. Saigal is a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

References

1. Questions and Answers. Limited English Proficiency: A federal interagency website. www.lep.gov/commonly-asked-questions.

2. United States Census Bureau. Percent of people 5 years and over who speak English less than ‘very well’. www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/people-that-speak-english-less-than-very-well.html.

3. Jacobs EA, et al. Overcoming language barriers in health care: Costs and benefits of interpreter services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):866–869. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.866.

4. Gandhi TK, et al. Drug complications in outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(3):149–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04199.x.

5. Karliner LS, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x.

6. Divi C, et al. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Apr;19(2):60-7. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl069.

7. Karliner LS, et al. Identification of limited English proficient patients in clinical care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1555-1560. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0693-y.

8. Schenker Y, et al. Patterns of interpreter use for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):712-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1619-z.

9. Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care: Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/finalreport.pdf.

10. www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financial-management/medicaid-administrative-claiming/translation-and-interpretation-services/index.html

11. Schenker Y, et al. The Impact of Language Barriers on Documentation of Informed Consent at a Hospital with On-Site Interpreter Services. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Nov;22 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):294-9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0359-1.

12. Locatis C, et al. Comparing in-person, video, and telephonic medical interpretation. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):345-350. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1236-x.

13. Dunlap JL, et al. The effects of language concordant care on patient satisfaction and clinical understanding for Hispanic pediatric surgery patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Sep;50(9):1586-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.12.020.

14. Diamond L, et al. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient–Physician Non-English Language Concordance on Quality of Care and Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Aug;34(8):1591-1606. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5.

15. Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Nov;22 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):324-30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z.

16. https://press.doximity.com/articles/first-ever-national-study-to-examine-different-languages-spoken-by-us-doctors.

17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patients with Limited English Proficiency. www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/lep/index.html.

A hectic Friday morning at the hospital seemed less stressful amid morning greetings and humor from colleagues. In a team room full of hospitalists, life and death are often discussed in detail, ranging from medical discussions to joys and frustrations of the day to philosophy, politics, and more. It is almost impossible to miss something interesting.

People breaking into their native languages over the phone call from home always make me smile. The mention of a “complicated Indian patient unable to use interpreter” caught my attention.

My friend and colleague asked if I would be willing to take over the patient since I could speak Hindi. I was doubtful if I would add anything to make a meaningful difference, given the patient wasn’t even participating in a conversation. However, my colleague’s concern for the patient and faith in me was enough to say, “Sure, let me add her to my list.”

At the bedside, it felt like a classic “acute on chronic” hot mess situation. The patient presented with a generalized rash, anasarca, renal failure, multifocal pneumonia, and delirium. All I could gather from the patient were some incomprehensible words that sounded like Hindi. I called the family to obtain some history and to provide updates. Her son was excited to hear from me, and it didn’t take him long to guess that I was from India. But that could still mean that I might speak any of the twenty-two or more Indian languages.

Answering my questions one by one in perfectly understandable English, he was short and sweet. Suspicious of missing out on details, I offered hesitantly, “You could speak in Hindi with me.” Then came a flood of information with the details, concerns, questions, and what was lost in the translation.

We all attend to patients and families with limited English proficiency (LEP), immigrants, and nonimmigrants. LEP is a term used to describe individuals who do not speak English as their primary language and have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English.1 Recent data from the American Community Survey (2005-2009) reports that 8.6% of the population (24 million Americans) have LEP.2 It’s a large and growing population that needs help overcoming language barriers and the appropriate use of professional medical interpreter services – a backbone to safe, quality, and cost-effective patient care.

The following day at bedside rounds, the nurse reported that the patient was looking and responding better. She could cooperate with interpreter services and could speak “some English.” Over the years, one thing that sounds more alarming than “no English” is “some English” or “enough English.” Around noon I received a page that the patient was refusing intravenous Lasix. At the bedside, however, the patient seemed unaware of the perceived refusal. Further discussions with the nurse lead to a familiar culprit, a relatively common gesture in South Asian cultures, a head bobble or shake.

The nurse reported that the patient shook her head side to side, seemed upset, and said “NO” when trying to administer the medication. On the other hand, the patient reported that she was upset to be at the hospital but had “NO” problem with the medicine.

My patient’s “some English” was indeed “enough English” to put her at risk due to medical error, which is highly likely when patients or providers can speak or understand a language to “get by” or to “make do.” Like my patient, the LEP patient population is more likely to experience medical errors, longer hospital stays, hospital-acquired complications, surgical delays, and readmissions. They are also less likely to receive preventive care, have access to regular care, or be satisfied with their care. They are much more likely to have adverse effects from drug complications, poor understanding of diagnoses, a greater risk of being misunderstood by their physicians or ancillary staff, and less likely to follow physician instructions.3-5 One study analyzed over 1,000 adverse-incident reports from six Joint Commission-accredited hospitals for LEP and English-speaking patients and found that 49% of LEP patients experienced physical harm versus 29.5% of English-speaking patients.6

I updated the patient’s LEP status that was missing in the chart, likely due to altered mental status at the time of admission. Reliable language and English proficiency data are usually entered at the patient’s point of entry with documentation of the language services required during the patient-provider encounter. The U.S. Census Bureau’s operational definition for LEP is a patient’s self-assessed ability to speak English less than “very well,” but how well it correlates with a patient’s actual English ability needs more study. Also, one’s self-assessed perception of ability might vary day to day, and language ability, by itself, is not static; it can differ from moment to moment and situation to situation. It may be easier to understand words in English when the situation is simple and less stressful than when things are complicated and stressful.

With a definition of LEP rather vague and the term somewhat derogatory, its meaning is open to interpretation. One study found that though speaking English less than “very well” was the most sensitive measure for identifying all of the patients who reported that they were unable to communicate effectively with their physicians, it was also the least specific.7 This lower specificity could lead to misclassification of some patients as LEP who are, in fact, able to effectively communicate in English with their physicians. This type of misclassification might lead to costly language assistance and carry the potential to cause conflicts between patient and provider. Telling a patient or family that they may have a “limited English proficiency” when they have believed otherwise and feel confident about their skills may come as a challenge. Some patients may also pretend to understand English to avoid being embarrassed about their linguistic abilities or perceive that they might be judged on their abilities in general.

Exiting the room, I gently reminded the RN to use the interpreter services. “Who has never been guilty of using an ad hoc interpreter or rushing through a long interpreter phone call due to time constraints?” I thought. A study from 2011 found that 43% of hospitalized patients with LEP had communicated without an interpreter present during admission, and 40% had communicated without an interpreter present after admission.8 In other words, a system in place does not mean service in use. But, the use of a trained interpreter is not only an obligation for care providers but a right for patients as per legal requirements of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and the Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) by the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HSS) Office of Minority Health.9 In January 2010, The Joint Commission released a set of new and revised standards for patient-centered communication as part of an initiative to advance effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care.

Despite the requirements and availability of qualified medical interpreter services, there are multiple perceived and experienced barriers to the use of interpreter services. The most common one is that what comes as a free service for patients is a time commitment for providers. A long list of patients, acuity of the situation, and ease of use/availability of translation aids can change the calculus. One may be able to bill a prolonged service code (99354-99357) in addition to the appropriate E/M code, although a patient cannot be billed for the actual service provided by the interpreter. Longstanding CMS policy also permits reimbursement for translation/interpretation activities, so long as they are not included and paid for as part of the rate for direct service.10

The patient, however, insisted that she would rather have her son as the interpreter on the 3-way over the phone (OPI) conference call for interpretation. “He speaks good English and knows my medical history well,” she said. I counseled the patient on the benefits of using interpreter services and explained how to use the call button light and the visual aids.

Placing emphasis on educating patients about the benefits of using, and risks of not using, interpreter services is as essential as emphasizing that care providers use the services. Some patients may voluntarily choose to provide their own interpreter. Use of family members, friends, or unqualified staff as interpreters is one of the most commonly reported causes of errors by frontline staff. Using in-language collateral may help these patients understand how medical interpretation may create a better patient experience and outcome. A short factsheet, in different languages, on qualified interpreters’ expected benefits: meaning-for-meaning communication, impartiality, medical privacy, and improved patient safety and satisfaction, can also come in handy.

However, if the patient still refuses, providers should document the refusal of the offer of free language services, the name of the interpreter designated by the patient, the interpreter’s relationship to the LEP person, and the time or portions of the patient encounter that the interpreter’s services were used. Yet, language interpretation alone can be inadequate without document translation. According to one study, despite the availability of on-site professional interpreter services, hospitalized patients who do not speak English are less likely to have signed consent forms in their medical records.11 Health care professionals, therefore, need well-translated documents to treat LEP patients. Translated documents of consent forms for medical procedures, post-discharge instructions, prescription and medical device labels, and drug usage information may enhance informed decision making, safety and reduce stress and medical errors.

An unpopular and underused service needs it all: availability, convenience, monitoring, reporting, and team effort. Due to the sheer unpopularity and underuse of interpreter services, institutions should enhance ease of availability, monitor the use and quality of interpreter services, and optimize reporting of language-related errors. Ease of availability goes hand in hand with tapping local resources. Over the years, and even more so during the pandemic, in-person interpretation has transitioned to telephonic or video interpretation due to availability, safety, and cost issues. There are challenges in translating a language, and the absence of a visual channel adds another layer of complexity.

The current body of evidence does not indicate a superior interpreting method. Still, in one study providers and interpreters exposed to all three methods were more critical of remote methods and preferred videoconferencing to the telephone as a remote method. The significantly shorter phone interviews raised questions about the prospects of miscommunication in telephonic interpretation, given the absence of a visual channel.12