User login

Uterine rupture, child stillborn: $3.8M net award

Uterine rupture, child stillborn: $3.8M net award

At 35 weeks' gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain, fast heartbeat, and irregular contractions. Her history included three cesarean deliveries, including one with a vertical incision. She was admitted, and a cesarean delivery was planned for the next day. After 8 hours, during which the patient’s condition worsened, an emergency cesarean delivery was undertaken. A full rupture of the uterus was found; the baby’s body had extruded into the mother’s abdomen. The child was stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The stillbirth could have been avoided if the nurses had communicated the mother’s worsening condition to the physicians.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE After the hospital and physicians settled prior to trial, the case continued against the nurse in charge of the mother’s care and the nurse-staffing group. Negligence was denied; all protocols were followed.

VERDICT A $2.9 million Illinois verdict was returned. With a $900,000 settlement from the hospital and physicians, the net award was $3.8 million.

_______________

Where did rare strep A infection come from?

A 36-year-old woman reported heavy vaginal bleeding to her ObGyn. She underwent endometrial ablation in her physician’s office.

The next day, the woman called the office to report abdominal pain. She was told to stop the medication she was taking, and if the pain continued to the next day, to go to an ED. The next day, the patient went to the ED and was found to be in septic shock. During emergency laparotomy, 50 mL of purulent fluid were drained and an emergency hysterectomy was performed. Three days later, the patient died from pulmonary arrest caused by toxic shock syndrome. An autopsy revealed that the patient’s sepsis was caused by group A streptococci (GAS) infection.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The patient was not a proper candidate for endometrial ablation because of her history of chronic cervical infection. The ObGyn perforated the cervix during the procedure and tried to conceal it. At autopsy, bone wax was found in the rectal lumen that had been used to cover up damage to the cervix. The ObGyn introduced GAS bacteria into the patient’s system. The ObGyn’s staff failed to ask the proper questions when she called the day after the procedure. She should have been told to go directly to the ED.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn did not perforate the cervix or uterus during the procedure. GAS infection is so rare that it would have been difficult to foresee or diagnose. Potentially, the patient had a chronic

cervical infection before ablation.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

_______________

DURING INSERTION, IUD PERFORATES UTERINE WALL; LATER FOUND BELOW LIVER

On July 21, a 46-year-old woman went to an ObGyn for placement of an intrauterine device (IUD). Shortly after the ObGyn inserted the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena, Bayer HealthCare), the patient reported severe pelvic and abdominal pain. On July 26, the patient underwent surgical removal of the IUD.

She was discharged on July 29 but continued to report pain. She was readmitted to the hospital the next day and treated for pain. She was bed ridden for 3 weeks after IUD-removal surgery, and had a 3-month recovery before feeling pain free.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in perforating the patient’s uterine wall during IUD insertion, causing the device to ultimately migrate under the patient’s liver.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Uterine perforation is a known complication of IUD insertion. The IUD escaped from the patient’s uterus at a later time and not during the insertion procedure.

VERDICT A Florida verdict of $208,839 was returned; the amount was reduced to $161,058 because the medical expenses were written off by the health-care providers.

_______________

Was travel appropriate for this pregnant woman?

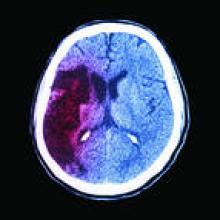

A woman with a history of two premature deliveries and one miscarriage became pregnant again. She received prenatal care at an Army hospital. She traveled to Spain, where the baby was born at 31 weeks’ gestation. The baby required treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for 17 days. The child has cerebral palsy, with tetraplegia of all four extremities. She cannot walk without assistance and suffers severe cognitive and vision impairment.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn at the Army hospital should not have approved the mother’s request for travel; he did so, despite knowing that the mother was at high risk for premature birth. The military medical hospital to which she was assigned in Spain could not manage a high-risk pregnancy, didn’t have a NICU, and didn’t have specialists to treat premature infants.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that he did not have access to the medical records showing the mother’s history. The patient countered that the ObGyn did indeed have the patient’s records, as he had discussed them with her.

VERDICT A $10,409,700 California verdict was returned against the ObGyn and the government facility.

_______________

Triple-negative BrCa not diagnosed until metastasized: $5.2M

After finding lumps in both breasts, a woman in her 30s saw a nurse practitioner (NP) at an Army hospital. A radiologist reported no mass in the right breast and multiple benign-appearing anechoic lesions in the left breast after bilateral mammography and ultrasonography (US) in July 2008. The Chief of Mammography Services recommended referral to a breast surgeon, but the patient never received the letter. It was placed in her mammography file, not in the treatment file.

In November 2008, the patient returned to the clinic. Bilateral diagnostic mammography and US were ordered, but for unknown reasons, cancelled. US of the left breast was interpreted as benign in January 2009.

After imaging in March 2010, followed by a needle biopsy of the right breast, a radiologist reported finding intermediate-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

The patient sought care outside the military medical system at a large university hospital. In April 2010, stage 3 triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was identified. The patient underwent chemotherapy, a double mastectomy, removal of 21 lymph nodes, and breast reconstruction. She was given a 60% chance of recurrence in 5–7 years.

PATIENT’S CLAIM It was negligent to not inform her of imaging results. Biopsy should have been performed in 2008, when the IDC was likely at stage 1; treatment would have been far less aggressive. Electronic medical records showed that the 2008 mammography and US results had been “signed off” by an NP at the clinic.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE While unable to concede liability, the government agency did not contest the point.

VERDICT A $5.2 million Tennessee federal court bench verdict was returned, citing failures in communication, poor and improper record keeping and retention, failure to follow-up, and an unexplained cancellation of a medical order.

_______________

Woman dies from cervical cancer: $2.3M

In 2001, a 41-year-old woman had abnormal Pap smear results but her gynecologist did not order more testing. The patient was told to return in 3 months, but she did not return until 2007—reporting abnormal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and pain. Her Pap results were normal, however, and the gynecologist did not order further testing. In 2009, the patient was found to have advanced cervical cancer. She died 2 years later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Further testing should have been ordered in 2001, which would have likely revealed dysplasia, which can lead to cancer. The laboratory incorrectly interpreted the 2007 Pap test; if the results had been properly reported, additional testing could have been ordered.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The laboratory and patient’s estate settled for a confidential amount before trial. The gynecologist denied negligence.

VERDICT A New Jersey jury found the gynecologist 40% at fault for his actions in 2007. The jury found the laboratory 50% at fault, and the patient 10% at fault. A gross verdict of $2.33 million was returned.

_______________

Bowel injury after cesarean delivery; mother dies of sepsis

At 40 4/7 weeks' gestation, a 37-year-old woman gave birth to a healthy child by cesarean delivery. The next day, the patient had an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with a left shift, her abdomen was tympanic but soft, and she was passing flatus and belching. The ObGyn ordered a Fleet enema; only flatus was released. A covering ObGyn ordered an abdominal radiograph, which the radiologist reported as showing postoperative ileus and mild constipation. The patient was given a second Fleet enema the next day, resulting in watery stool. She vomited 300 mL of dark green fluid.

After a rectal tube was placed 2 days later, one hard brown stool and several brown, pasty, loose, and liquid stools were returned. She vomited several times that day, and was found to have hypoactive bowel sounds with continued tympanic quality in the upper quadrants. Laboratory testing revealed continued elevated WBC count with left shift. The next day, she had hypoactive bowel sounds with brown liquid stools. Later that morning, she was able to tolerate clear liquids. The ObGyn decided to discharge her home with instructions to continue on a clear liquid diet for 2 more days before advancing her diet.

The day after discharge, she was found unresponsive at home. She was taken to the hospital, but resuscitation attempts failed. She died. An autopsy revealed that the cause of death was sepsis.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to diagnose and treat a postoperative intra-abdominal infection caused by bowel perforation. A surgical consult should have been obtained. The woman was prematurely discharged. The radiologist failed to report the presence of free air on the abdominal x-ray.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT A $1 million Maryland settlement was reached.

_______________

Right ureter injury detected and repaired

During laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, the ObGyn detected and repaired an injury to the right ureter. The patient’s recovery was delayed by the injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in using a Kleppinger bipolar cauterizing instrument to cauterize the vaginal cuff. Thermal overspray from the instrument or the instrument itself damaged the ureter. The ObGyn was also negligent in not performing diagnostic cystoscopy to confirm patency of the ureter after the repair was made.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. All procedures were performed according to protocol.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

_______________

Failure to detect inflammatory BrCa; woman dies

A 42-year-old woman underwent mammography in February 2002 after reporting pain, discoloration, inflammation, and swelling in her left breast. The radiologist who interpreted the mammography suggested a biopsy for a differential diagnosis of mastitis or inflammatory carcinoma. The biopsy results were negative.

The patient’s symptoms persisted, and she underwent US in late May 2002. Another radiologist interpreted the US, noting that the patient could not tolerate compression, which led to less than optimal evaluation. The radiologist suggested that mastitis was the likely cause of the patient’s symptoms.

The patient then consulted a surgeon, who ordered mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) followed by biopsy, which indicated cancer. The patient underwent a mastectomy but metastasis had already occurred. She died at age 50 prior to the trial.

ESTATE’S CLAIM If the cancer had been diagnosed earlier, the outcome would have been better. Both radiologists misinterpreted the mammographies.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The mammographies had been properly interpreted. Any missed diagnosis would not have impacted the outcome due to the type of cancer. The scans had been released to the patient, but were subsequently lost; an adverse interference instruction was given to the jury.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine rupture, child stillborn: $3.8M net award

At 35 weeks' gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain, fast heartbeat, and irregular contractions. Her history included three cesarean deliveries, including one with a vertical incision. She was admitted, and a cesarean delivery was planned for the next day. After 8 hours, during which the patient’s condition worsened, an emergency cesarean delivery was undertaken. A full rupture of the uterus was found; the baby’s body had extruded into the mother’s abdomen. The child was stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The stillbirth could have been avoided if the nurses had communicated the mother’s worsening condition to the physicians.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE After the hospital and physicians settled prior to trial, the case continued against the nurse in charge of the mother’s care and the nurse-staffing group. Negligence was denied; all protocols were followed.

VERDICT A $2.9 million Illinois verdict was returned. With a $900,000 settlement from the hospital and physicians, the net award was $3.8 million.

_______________

Where did rare strep A infection come from?

A 36-year-old woman reported heavy vaginal bleeding to her ObGyn. She underwent endometrial ablation in her physician’s office.

The next day, the woman called the office to report abdominal pain. She was told to stop the medication she was taking, and if the pain continued to the next day, to go to an ED. The next day, the patient went to the ED and was found to be in septic shock. During emergency laparotomy, 50 mL of purulent fluid were drained and an emergency hysterectomy was performed. Three days later, the patient died from pulmonary arrest caused by toxic shock syndrome. An autopsy revealed that the patient’s sepsis was caused by group A streptococci (GAS) infection.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The patient was not a proper candidate for endometrial ablation because of her history of chronic cervical infection. The ObGyn perforated the cervix during the procedure and tried to conceal it. At autopsy, bone wax was found in the rectal lumen that had been used to cover up damage to the cervix. The ObGyn introduced GAS bacteria into the patient’s system. The ObGyn’s staff failed to ask the proper questions when she called the day after the procedure. She should have been told to go directly to the ED.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn did not perforate the cervix or uterus during the procedure. GAS infection is so rare that it would have been difficult to foresee or diagnose. Potentially, the patient had a chronic

cervical infection before ablation.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

_______________

DURING INSERTION, IUD PERFORATES UTERINE WALL; LATER FOUND BELOW LIVER

On July 21, a 46-year-old woman went to an ObGyn for placement of an intrauterine device (IUD). Shortly after the ObGyn inserted the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena, Bayer HealthCare), the patient reported severe pelvic and abdominal pain. On July 26, the patient underwent surgical removal of the IUD.

She was discharged on July 29 but continued to report pain. She was readmitted to the hospital the next day and treated for pain. She was bed ridden for 3 weeks after IUD-removal surgery, and had a 3-month recovery before feeling pain free.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in perforating the patient’s uterine wall during IUD insertion, causing the device to ultimately migrate under the patient’s liver.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Uterine perforation is a known complication of IUD insertion. The IUD escaped from the patient’s uterus at a later time and not during the insertion procedure.

VERDICT A Florida verdict of $208,839 was returned; the amount was reduced to $161,058 because the medical expenses were written off by the health-care providers.

_______________

Was travel appropriate for this pregnant woman?

A woman with a history of two premature deliveries and one miscarriage became pregnant again. She received prenatal care at an Army hospital. She traveled to Spain, where the baby was born at 31 weeks’ gestation. The baby required treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for 17 days. The child has cerebral palsy, with tetraplegia of all four extremities. She cannot walk without assistance and suffers severe cognitive and vision impairment.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn at the Army hospital should not have approved the mother’s request for travel; he did so, despite knowing that the mother was at high risk for premature birth. The military medical hospital to which she was assigned in Spain could not manage a high-risk pregnancy, didn’t have a NICU, and didn’t have specialists to treat premature infants.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that he did not have access to the medical records showing the mother’s history. The patient countered that the ObGyn did indeed have the patient’s records, as he had discussed them with her.

VERDICT A $10,409,700 California verdict was returned against the ObGyn and the government facility.

_______________

Triple-negative BrCa not diagnosed until metastasized: $5.2M

After finding lumps in both breasts, a woman in her 30s saw a nurse practitioner (NP) at an Army hospital. A radiologist reported no mass in the right breast and multiple benign-appearing anechoic lesions in the left breast after bilateral mammography and ultrasonography (US) in July 2008. The Chief of Mammography Services recommended referral to a breast surgeon, but the patient never received the letter. It was placed in her mammography file, not in the treatment file.

In November 2008, the patient returned to the clinic. Bilateral diagnostic mammography and US were ordered, but for unknown reasons, cancelled. US of the left breast was interpreted as benign in January 2009.

After imaging in March 2010, followed by a needle biopsy of the right breast, a radiologist reported finding intermediate-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

The patient sought care outside the military medical system at a large university hospital. In April 2010, stage 3 triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was identified. The patient underwent chemotherapy, a double mastectomy, removal of 21 lymph nodes, and breast reconstruction. She was given a 60% chance of recurrence in 5–7 years.

PATIENT’S CLAIM It was negligent to not inform her of imaging results. Biopsy should have been performed in 2008, when the IDC was likely at stage 1; treatment would have been far less aggressive. Electronic medical records showed that the 2008 mammography and US results had been “signed off” by an NP at the clinic.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE While unable to concede liability, the government agency did not contest the point.

VERDICT A $5.2 million Tennessee federal court bench verdict was returned, citing failures in communication, poor and improper record keeping and retention, failure to follow-up, and an unexplained cancellation of a medical order.

_______________

Woman dies from cervical cancer: $2.3M

In 2001, a 41-year-old woman had abnormal Pap smear results but her gynecologist did not order more testing. The patient was told to return in 3 months, but she did not return until 2007—reporting abnormal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and pain. Her Pap results were normal, however, and the gynecologist did not order further testing. In 2009, the patient was found to have advanced cervical cancer. She died 2 years later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Further testing should have been ordered in 2001, which would have likely revealed dysplasia, which can lead to cancer. The laboratory incorrectly interpreted the 2007 Pap test; if the results had been properly reported, additional testing could have been ordered.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The laboratory and patient’s estate settled for a confidential amount before trial. The gynecologist denied negligence.

VERDICT A New Jersey jury found the gynecologist 40% at fault for his actions in 2007. The jury found the laboratory 50% at fault, and the patient 10% at fault. A gross verdict of $2.33 million was returned.

_______________

Bowel injury after cesarean delivery; mother dies of sepsis

At 40 4/7 weeks' gestation, a 37-year-old woman gave birth to a healthy child by cesarean delivery. The next day, the patient had an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with a left shift, her abdomen was tympanic but soft, and she was passing flatus and belching. The ObGyn ordered a Fleet enema; only flatus was released. A covering ObGyn ordered an abdominal radiograph, which the radiologist reported as showing postoperative ileus and mild constipation. The patient was given a second Fleet enema the next day, resulting in watery stool. She vomited 300 mL of dark green fluid.

After a rectal tube was placed 2 days later, one hard brown stool and several brown, pasty, loose, and liquid stools were returned. She vomited several times that day, and was found to have hypoactive bowel sounds with continued tympanic quality in the upper quadrants. Laboratory testing revealed continued elevated WBC count with left shift. The next day, she had hypoactive bowel sounds with brown liquid stools. Later that morning, she was able to tolerate clear liquids. The ObGyn decided to discharge her home with instructions to continue on a clear liquid diet for 2 more days before advancing her diet.

The day after discharge, she was found unresponsive at home. She was taken to the hospital, but resuscitation attempts failed. She died. An autopsy revealed that the cause of death was sepsis.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to diagnose and treat a postoperative intra-abdominal infection caused by bowel perforation. A surgical consult should have been obtained. The woman was prematurely discharged. The radiologist failed to report the presence of free air on the abdominal x-ray.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT A $1 million Maryland settlement was reached.

_______________

Right ureter injury detected and repaired

During laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, the ObGyn detected and repaired an injury to the right ureter. The patient’s recovery was delayed by the injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in using a Kleppinger bipolar cauterizing instrument to cauterize the vaginal cuff. Thermal overspray from the instrument or the instrument itself damaged the ureter. The ObGyn was also negligent in not performing diagnostic cystoscopy to confirm patency of the ureter after the repair was made.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. All procedures were performed according to protocol.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

_______________

Failure to detect inflammatory BrCa; woman dies

A 42-year-old woman underwent mammography in February 2002 after reporting pain, discoloration, inflammation, and swelling in her left breast. The radiologist who interpreted the mammography suggested a biopsy for a differential diagnosis of mastitis or inflammatory carcinoma. The biopsy results were negative.

The patient’s symptoms persisted, and she underwent US in late May 2002. Another radiologist interpreted the US, noting that the patient could not tolerate compression, which led to less than optimal evaluation. The radiologist suggested that mastitis was the likely cause of the patient’s symptoms.

The patient then consulted a surgeon, who ordered mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) followed by biopsy, which indicated cancer. The patient underwent a mastectomy but metastasis had already occurred. She died at age 50 prior to the trial.

ESTATE’S CLAIM If the cancer had been diagnosed earlier, the outcome would have been better. Both radiologists misinterpreted the mammographies.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The mammographies had been properly interpreted. Any missed diagnosis would not have impacted the outcome due to the type of cancer. The scans had been released to the patient, but were subsequently lost; an adverse interference instruction was given to the jury.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine rupture, child stillborn: $3.8M net award

At 35 weeks' gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain, fast heartbeat, and irregular contractions. Her history included three cesarean deliveries, including one with a vertical incision. She was admitted, and a cesarean delivery was planned for the next day. After 8 hours, during which the patient’s condition worsened, an emergency cesarean delivery was undertaken. A full rupture of the uterus was found; the baby’s body had extruded into the mother’s abdomen. The child was stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The stillbirth could have been avoided if the nurses had communicated the mother’s worsening condition to the physicians.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE After the hospital and physicians settled prior to trial, the case continued against the nurse in charge of the mother’s care and the nurse-staffing group. Negligence was denied; all protocols were followed.

VERDICT A $2.9 million Illinois verdict was returned. With a $900,000 settlement from the hospital and physicians, the net award was $3.8 million.

_______________

Where did rare strep A infection come from?

A 36-year-old woman reported heavy vaginal bleeding to her ObGyn. She underwent endometrial ablation in her physician’s office.

The next day, the woman called the office to report abdominal pain. She was told to stop the medication she was taking, and if the pain continued to the next day, to go to an ED. The next day, the patient went to the ED and was found to be in septic shock. During emergency laparotomy, 50 mL of purulent fluid were drained and an emergency hysterectomy was performed. Three days later, the patient died from pulmonary arrest caused by toxic shock syndrome. An autopsy revealed that the patient’s sepsis was caused by group A streptococci (GAS) infection.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The patient was not a proper candidate for endometrial ablation because of her history of chronic cervical infection. The ObGyn perforated the cervix during the procedure and tried to conceal it. At autopsy, bone wax was found in the rectal lumen that had been used to cover up damage to the cervix. The ObGyn introduced GAS bacteria into the patient’s system. The ObGyn’s staff failed to ask the proper questions when she called the day after the procedure. She should have been told to go directly to the ED.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn did not perforate the cervix or uterus during the procedure. GAS infection is so rare that it would have been difficult to foresee or diagnose. Potentially, the patient had a chronic

cervical infection before ablation.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

_______________

DURING INSERTION, IUD PERFORATES UTERINE WALL; LATER FOUND BELOW LIVER

On July 21, a 46-year-old woman went to an ObGyn for placement of an intrauterine device (IUD). Shortly after the ObGyn inserted the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena, Bayer HealthCare), the patient reported severe pelvic and abdominal pain. On July 26, the patient underwent surgical removal of the IUD.

She was discharged on July 29 but continued to report pain. She was readmitted to the hospital the next day and treated for pain. She was bed ridden for 3 weeks after IUD-removal surgery, and had a 3-month recovery before feeling pain free.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in perforating the patient’s uterine wall during IUD insertion, causing the device to ultimately migrate under the patient’s liver.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Uterine perforation is a known complication of IUD insertion. The IUD escaped from the patient’s uterus at a later time and not during the insertion procedure.

VERDICT A Florida verdict of $208,839 was returned; the amount was reduced to $161,058 because the medical expenses were written off by the health-care providers.

_______________

Was travel appropriate for this pregnant woman?

A woman with a history of two premature deliveries and one miscarriage became pregnant again. She received prenatal care at an Army hospital. She traveled to Spain, where the baby was born at 31 weeks’ gestation. The baby required treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for 17 days. The child has cerebral palsy, with tetraplegia of all four extremities. She cannot walk without assistance and suffers severe cognitive and vision impairment.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn at the Army hospital should not have approved the mother’s request for travel; he did so, despite knowing that the mother was at high risk for premature birth. The military medical hospital to which she was assigned in Spain could not manage a high-risk pregnancy, didn’t have a NICU, and didn’t have specialists to treat premature infants.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that he did not have access to the medical records showing the mother’s history. The patient countered that the ObGyn did indeed have the patient’s records, as he had discussed them with her.

VERDICT A $10,409,700 California verdict was returned against the ObGyn and the government facility.

_______________

Triple-negative BrCa not diagnosed until metastasized: $5.2M

After finding lumps in both breasts, a woman in her 30s saw a nurse practitioner (NP) at an Army hospital. A radiologist reported no mass in the right breast and multiple benign-appearing anechoic lesions in the left breast after bilateral mammography and ultrasonography (US) in July 2008. The Chief of Mammography Services recommended referral to a breast surgeon, but the patient never received the letter. It was placed in her mammography file, not in the treatment file.

In November 2008, the patient returned to the clinic. Bilateral diagnostic mammography and US were ordered, but for unknown reasons, cancelled. US of the left breast was interpreted as benign in January 2009.

After imaging in March 2010, followed by a needle biopsy of the right breast, a radiologist reported finding intermediate-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

The patient sought care outside the military medical system at a large university hospital. In April 2010, stage 3 triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was identified. The patient underwent chemotherapy, a double mastectomy, removal of 21 lymph nodes, and breast reconstruction. She was given a 60% chance of recurrence in 5–7 years.

PATIENT’S CLAIM It was negligent to not inform her of imaging results. Biopsy should have been performed in 2008, when the IDC was likely at stage 1; treatment would have been far less aggressive. Electronic medical records showed that the 2008 mammography and US results had been “signed off” by an NP at the clinic.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE While unable to concede liability, the government agency did not contest the point.

VERDICT A $5.2 million Tennessee federal court bench verdict was returned, citing failures in communication, poor and improper record keeping and retention, failure to follow-up, and an unexplained cancellation of a medical order.

_______________

Woman dies from cervical cancer: $2.3M

In 2001, a 41-year-old woman had abnormal Pap smear results but her gynecologist did not order more testing. The patient was told to return in 3 months, but she did not return until 2007—reporting abnormal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and pain. Her Pap results were normal, however, and the gynecologist did not order further testing. In 2009, the patient was found to have advanced cervical cancer. She died 2 years later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Further testing should have been ordered in 2001, which would have likely revealed dysplasia, which can lead to cancer. The laboratory incorrectly interpreted the 2007 Pap test; if the results had been properly reported, additional testing could have been ordered.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The laboratory and patient’s estate settled for a confidential amount before trial. The gynecologist denied negligence.

VERDICT A New Jersey jury found the gynecologist 40% at fault for his actions in 2007. The jury found the laboratory 50% at fault, and the patient 10% at fault. A gross verdict of $2.33 million was returned.

_______________

Bowel injury after cesarean delivery; mother dies of sepsis

At 40 4/7 weeks' gestation, a 37-year-old woman gave birth to a healthy child by cesarean delivery. The next day, the patient had an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with a left shift, her abdomen was tympanic but soft, and she was passing flatus and belching. The ObGyn ordered a Fleet enema; only flatus was released. A covering ObGyn ordered an abdominal radiograph, which the radiologist reported as showing postoperative ileus and mild constipation. The patient was given a second Fleet enema the next day, resulting in watery stool. She vomited 300 mL of dark green fluid.

After a rectal tube was placed 2 days later, one hard brown stool and several brown, pasty, loose, and liquid stools were returned. She vomited several times that day, and was found to have hypoactive bowel sounds with continued tympanic quality in the upper quadrants. Laboratory testing revealed continued elevated WBC count with left shift. The next day, she had hypoactive bowel sounds with brown liquid stools. Later that morning, she was able to tolerate clear liquids. The ObGyn decided to discharge her home with instructions to continue on a clear liquid diet for 2 more days before advancing her diet.

The day after discharge, she was found unresponsive at home. She was taken to the hospital, but resuscitation attempts failed. She died. An autopsy revealed that the cause of death was sepsis.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to diagnose and treat a postoperative intra-abdominal infection caused by bowel perforation. A surgical consult should have been obtained. The woman was prematurely discharged. The radiologist failed to report the presence of free air on the abdominal x-ray.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT A $1 million Maryland settlement was reached.

_______________

Right ureter injury detected and repaired

During laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, the ObGyn detected and repaired an injury to the right ureter. The patient’s recovery was delayed by the injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in using a Kleppinger bipolar cauterizing instrument to cauterize the vaginal cuff. Thermal overspray from the instrument or the instrument itself damaged the ureter. The ObGyn was also negligent in not performing diagnostic cystoscopy to confirm patency of the ureter after the repair was made.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. All procedures were performed according to protocol.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

_______________

Failure to detect inflammatory BrCa; woman dies

A 42-year-old woman underwent mammography in February 2002 after reporting pain, discoloration, inflammation, and swelling in her left breast. The radiologist who interpreted the mammography suggested a biopsy for a differential diagnosis of mastitis or inflammatory carcinoma. The biopsy results were negative.

The patient’s symptoms persisted, and she underwent US in late May 2002. Another radiologist interpreted the US, noting that the patient could not tolerate compression, which led to less than optimal evaluation. The radiologist suggested that mastitis was the likely cause of the patient’s symptoms.

The patient then consulted a surgeon, who ordered mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) followed by biopsy, which indicated cancer. The patient underwent a mastectomy but metastasis had already occurred. She died at age 50 prior to the trial.

ESTATE’S CLAIM If the cancer had been diagnosed earlier, the outcome would have been better. Both radiologists misinterpreted the mammographies.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The mammographies had been properly interpreted. Any missed diagnosis would not have impacted the outcome due to the type of cancer. The scans had been released to the patient, but were subsequently lost; an adverse interference instruction was given to the jury.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More inclusions:

- Where did rare strep A infection come from?

- During insertion, IUD perforates uterine wall; Later found below liver

- Was travel appropriate for this pregnant woman?

- Triple-negative BrCa not diagnosed until metastasized: $5.2M

- Woman dies from cervical cancer: $2.3M

- Bowel injury after cesarean delivery; mother dies of sepsis

- Right ureter injury detected and repaired

- Failure to detect inflammatory BrCa; woman dies

The Affordable Care Act: What’s the latest?

mmmm

When I last wrote about the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in May 2014, I focused on the contraception issue. Since then, the US Supreme Court ruled, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, that closely held, for-profit companies with religious objections to covering birth control can opt out of the requirement to provide contraceptive coverage to their employees.

In this article, I explore that decision and what it means for women’s health. I also present data on the uninsured rate in the United States, which has dropped significantly since enactment of the ACA, and I discuss one increasingly common barrier to access to care—the use of narrow networks by insurers.

A corporation now can hold a religious belief

The Supreme Court’s majority 5-4 ruling recognized, for the first time, that a for-profit corporation can hold a religious belief, but the Court limited this claim to closely held corporations. The Court also decided that the ACA placed a substantial burden on the corporations’ religious beliefs and concluded that there are less burdensome ways to accomplish the law’s intent, rendering the contraceptive coverage provision in the ACA in violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). The Court limited its ruling to the contraceptive coverage requirement, essentially turning the requirement into an option for many employers.

Are contraceptives abortifacients?

The religious belief at the center of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby was that life begins at conception, which the Green family—the owners of Hobby Lobby—equate to fertilization. Hobby Lobby’s attorneys also asserted that four contraceptives approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and included in the ACA mandate may prevent implantation of a fertilized egg, thereby constituting abortion.

Although there is no scientific answer as to when life begins, ACOG and the medical community agree that pregnancy begins at implantation. In its amicus brief to the US Supreme Court, ACOG asserted the medical community’s consensus that the four contraceptives prevent pregnancy rather than end it, and are not abortifacients:

- emergency contraceptive pills: levonorgestrel (Plan B) and its generic equivalents and ulipristal acetate (ella)

- the copper IUD (ParaGard)

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (Mirena, Skyla).

What is a closely held corporation?

In general, according to the Pew Research Center, a closely held corporation is a private company (not publicly traded) with a limited number of shareholders. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), an important source, defines a closely held corporation as one in which more than half of the stock is owned (directly or indirectly) by five or fewer individuals at any time in the second half of the year.

“S” corporations are also considered closely held. These are corporations with 100 or fewer shareholders, with all members of the same family counted as one shareholder. “S” corporations don’t pay income tax; their shareholders pay tax on their personal returns, based on the corporations’ profits and losses.

Hobby Lobby is organized as an “S” corporation. According to the IRS, in 2011, there were 4,158,572 “S” corporations, 99.4% of them with 10 or fewer shareholders.1

The US Census Bureau estimates that, in 2012, about 2.9 million “S” corporations employed more than 29 million people. Many closely held corporations are quite large.2 According to the Pew Research Center, family-owned Cargill employs 140,000 people and had $136.7 billion in revenue in fiscal 2013. Hobby Lobby has estimated revenues of $3.3 billion and 23,000 employees.2

What’s next?

ACOG helped secure coverage of contraceptives in the ACA and is working with the US Congress and our women’s health partners to restore this important care. Days after the Supreme Court decision, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) introduced the Protect Women’s Health from Corporate Interference Act, S. 2578, with 46 cosponsors as of this writing. ACOG fully supports this bill, also known as the “Not My Boss’ Business Bill,” which would reestablish the contraceptive coverage mandate as well as other care required by federal law. This bill still maintains the exemption from contraceptive coverage for houses of worship and the accommodation for religious nonprofits.

In introducing her bill, Senator Murray pointed out that “the contraceptive coverage requirement has already made a tremendous difference in women’s lives—24 million more prescriptions for oral contraceptives were filled with no copay in 2013 than in 2012, and women have saved $483 million in out-of-pocket costs for oral contraceptives.”3

Uninsured rate is declining

The Commonwealth Fund shows that, from July–September 2013 to April–June 2014, the nation’s uninsured rate fell from 20% to 15%, resulting in 9.5 million fewer uninsured adults.4 The biggest drop occurred among young adults, with the uninsured rate falling from 28% to 18%, and in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion, where uninsured rates fell from 28% to 17%.4

States that didn’t expand their Medicaid program didn’t show any noticeable change, with the uninsured rate declining only two points, from 38% to 36%.4

Coverage resulted in access to care for the majority of the newly covered. Sixty percent of people with new coverage visited a provider or hospital or paid for a prescription. Sixty-two percent of these individuals said they wouldn’t have been able to access this care before getting this coverage. Eighty-one percent of people with new coverage said they were better off now than before.4

ACA works better in some states than others

The Kaiser Family Foundation looked at four successful states—Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, and Washington state—to see what lessons can be learned. Important commonalities include the fact that the states run their own marketplace, adopted the Medi-caid expansion, and conducted extensive outreach and public education, including engaging providers in patient outreach and enrollment.5

Other tools of success were developing good marketing and branding, providing consumer-friendly assistance, and attention to systems and operations.5

How the Hobby Lobby decision affects individual states

Because the Supreme Court’s decision concerned interpretation of a federal law—the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA)—it does not supersede state laws that mandate coverage of contraceptives.

Twenty-eight states have laws or rulings requiring insurers to cover contraceptives, most of them dating from the 1990s and providing some exemption for religious insurers or plans. Only Illinois allows an exemption for secular bodies.

Although these state laws remain in effect, state officials may opt to stop enforcing them with regard to certain companies. For example, after the Hobby Lobby decision, Wisconsin officials announced that they no longer will enforce contraceptive coverage when a company has a religious objection.

For companies that self-fund or self-insure worker health coverage, the state coverage laws don’t apply—only federal law does. These companies do not have to adhere to state insurance mandates.

Some states have their own version of the RFRA. See the chart at right for details on a state-by-state basis.

The Supreme Court ruling also has no effect on state laws that guarantee access to emergency contraception in hospital emergency departments and that require pharmacists to dispense contraceptives.

| State | Contraceptive equity law? | Employer/insurer exemption to equity law? | Religious freedom law? |

| Alabama | ✔ | ||

| Alaska | |||

| Arizona | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Arkansas | ✔ | ✔ | |

| California | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Colorado | ✔ | ||

| Connecticut | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Delaware | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Florida | ✔ | ||

| Georgia | ✔ | ||

| Hawaii | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Idaho | ✔ | ||

| Illinois | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Indiana | |||

| Iowa | ✔ | ||

| Kansas | |||

| Kentucky | ✔ | ||

| Louisiana | ✔ | ||

| Maine | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Maryland | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Massachusetts | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Michigan | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Minnesota | |||

| Mississippi | ✔ | ||

| Missouri | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Montana | ✔ | ||

| Nebraska | |||

| Nevada | ✔ | ✔ | |

| New Hampshire | ✔ | ||

| New Jersey | ✔ | ✔ | |

| New Mexico | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| New York | ✔ | ✔ | |

| North Carolina | ✔ | ✔ | |

| North Dakota | |||

| Ohio | |||

| Oklahoma | ✔ | ||

| Oregon | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Pennsylvania | ✔ | ||

| Rhode Island | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| South Carolina | ✔ | ||

| South Dakota | |||

| Tennessee | ✔ | ||

| Texas | ✔ | ||

| Utah | |||

| Vermont | ✔ | ||

| Virginia | ✔ | ||

| Washington | ✔ | ||

| West Virginia | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Wisconsin | ✔ | ||

| Wyoming | |||

| TOTAL | 28 | 20 | 18 |

Narrow networks limit access to care

Huge concerns abound regarding implementation and real-life experiences related to the ACA. A number of them—high deductibles, low payment rates, limited access to physicians, long drive and wait times—can be related to “narrow networks.” Insurers exclude certain providers and offer all providers lower payment rates (which leads some physicians to drop out of the plan); they also create tiers (charging consumers lower copays and deductibles for using inner-tier preferred providers and high out-of-pocket costs for using other providers, even though they may be in the network).

Narrow networks work for insurers as an effective tool for lowering provider payment rates to keep premiums low and gain market share. The narrower the network, the lower are physician payments and premiums.

The ACA promises expanded access to high-quality, affordable health care for millions of Americans—a promise being compromised in many areas of the country through narrow networks. In these instances, insurers offering new plans in a health-care marketplace limit patient access to the numbers, types, and locations of physicians and hospitals covered under certain plans. Insurers typically offer patients low premiums, offer selected providers a high volume of patients at low payment levels, and exclude other providers whom the insurer deems to be high-cost.

Narrow networks aren’t new

As with so many elements of the ACA, narrow networks aren’t a new phenomenon. Many of us remember the public relations price that HMOs paid in the 1980s and 1990s for exceedingly limiting patients’ access to care while charging low premiums. The consumer outcry led the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to urge states to require managed-care plans to maintain adequate networks, the approach adopted by the federal government in the ACA.6

The pendulum swung in the next decade to broader networks in which consumers had much greater access, but premiums increased by an average of 11% per year.6 Employers then pushed insurers to reduce premium costs, leading back to narrow networks in the years just before the ACA. Narrow network plans accounted for 23% of all employer-sponsored plans in 2012, up from 15% in 2007.6

Increasing consolidation contributes to narrow networks

The trend toward narrower networks is also linked to increasing consolidation in health care. As health systems grow and individual or small group practices disappear, insurers rely on being able to credibly threaten to exclude systems and big groups from their networks as leverage in payment negotiations. By restricting the choice of providers in a plan, the insurer can promise more customers for the doctors and hospitals that are included, and negotiate lower payments to those providers.

The downside for physicians is clear:

- low payment rates

- exclusion from networks and coverage

- inability to refer patients to providers the physician determines to be best for that patient’s needs.

- The downside for patients:

- If they have to go out of network to get needed care, they may end up paying high out-of-pocket costs

- If they delay or forego care, their health may suffer significantly.

The insurance industry’s position is that patients have choices. Plans with access to more hospitals and specialists are available but usually at a higher price.

Narrow networks are one way to achieve low premiums

In the months leading up to ACA enactment, insurers got to work developing plans designed to be sold on the exchanges that would attract consumers through low-cost premiums and still maximize profits, especially now that insurers, under the ACA, are barred from excluding sick enrollees or increasing premiums for women, in addition to other important protections.

In previous articles, we’ve explored these landmark protections. Insurers in the individual market used to be able to keep premiums relatively low, and profits up, through use of preexisting coverage exclusions, benefit exclusions including noncoverage for maternity care or prescription drugs, and high cost sharing. Not anymore.

Since enactment of the ACA, narrow networks seem to be the preferred, and most effective, payment negotiation tool of many insurers offering plans through the exchanges, reflecting the trend we’re already seeing in the private health insurance marketplace.

NPR spotlights the difficulty of finding a specialist

The consumer and provider problems of narrow networks have been gaining attention in the media. In July, the National Public Radio (NPR) Web site carried an article entitled, “Patients with low-cost insurance struggle to find specialists,” with a key subtitle: “So you found an exchange plan. But can you find a provider?”7

In the NPR article, author Carrie Feibel reported on the situation in a majority-immigrant area of southwest Houston.

There, many patients at the local clinic have health insurance coverage for the first time, an important step toward healthier lives for themselves and their families. But many people in need of a specialist are learning that their insurance card doesn’t guarantee them access to a needed surgeon or hospital. They’ve purchased a narrow-network insurance plan, with a low premium but few specialists who accept that insurance.7

The two largest hospital chains in Houston—Houston Methodist and Memorial Hermann—as well as Houston’s MD Anderson Cancer Center, don’t participate in the Blue Cross Blue Shield HMO Silver plan, a plan popular with low-income consumers because of its low premium.7

Will the government take action?

The ACA actually guards against overly narrow networks and established the first national standard for network adequacy—a standard that needs fuller development, for sure. Plans sold on the exchanges are required to establish networks that include, among other providers, essential community providers, who typically care for mostly low-income and medically underserved populations. Networks also must include sufficient numbers and types of providers, including “providers that specialize in mental health and substance abuse services, to assure that all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay.”8

Insurers also must provide people who are considering purchasing their products with an accurate directory—both online and a hard copy—identifying providers not accepting new patients in the network. And plans are prohibited from charging out-of-network cost-sharing for emergency services.

Much of the oversight and many of the details—how much is adequate? what is unreasonable?—are left to the states, many of which have years of experience grappling with the downsides and delicate balance of networks.

The Urban Institute points out that Vermont and Delaware set standards for maximum geographic distance and drive times for primary care services. In California, plans must make it easy for consumers to reach urban providers on public transportation.6

Professional societies are taking note

Today, the misuse of narrow networks by exchange plans also has gotten the attention of the American Medical Association, ACOG, and many other national medical specialty societies, in addition to the states and federal government.

The trick, many health-care policy experts agree, is to find the right balance. How broad can the network be before premiums soar? Most agree that consumers must be able to choose between plans with confidence, without any cost or access surprises, meaning much better transparency. And many agree that provider quality, in addition to cost, has to find its way into the equation.

This year, the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, a part of the federal Department of Health and Human Services created by the ACA to investigate these kinds of issues, is investigating access to hospital systems, mental health services, oncology, and primary care providers and is developing time, distance, and other standards that insurers will have to adhere to.

Employer groups oppose strong standards or limits on narrow networks. Recently, representatives of the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Retail Federation, and others warned Congress to stay out of this fight. They understand that more generous networks mean higher premiums. These employer representative groups prefer to strengthen consumer protections like directories and keep low the cost of health insurance that they provide for their employees.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the work and expertise of ACOG's state government affairs team for the state analysis—Kathryn Moore, Director, and Kate Vlach, Senior Manager—as well as advocacy partners.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Internal Revenue Service. SOI Tax States, Table 1, Returns of Active Corporations, Form 1120S. http://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Table-1-Returns-of-Active-Corporations,-Form-1120S. Updated June 27, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

2. DeSilver D. What is a ‘closely held corporation,’ anyway, and how many are there? Pew Research Center: Fact Tank. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/07/07/what-is-a-closely-held-corporation-anyway-and-how-many-are-there/. Published July 7, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

3. Murray P. Protect Women’s Health From Corporate Interference Act: Summary. http://www.murray.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/30554052-0f84-485a-babc-ccc04af85bb6/protect-women-s-health-from-corporate-interference-act---one-page-summary---final.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2014.

4. The Commonwealth Fund. New Survey: After First ACA Enrollment Period, Uninsured Rate Dropped from 20% to 15%; Largest Declines Among Young Adults, Latinos, and Low-Income People. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/press-releases/2014/jul/after-first-aca -enrollment-period. Published July 10,2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

5. Artiga S, Stephens J, Rudowitz R, Perry M. What Worked and What’s Next? Strategies in Four States Leading ACA Enrollment Efforts. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/what-worked-and-whats-next-strategies-in-four-states-leading-aca-enrollment-efforts/. Published July 16, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

6. Corlette S, Volk J. Narrow Provider Networks in New Health Plans: Balancing Affordability with Access to Quality Care. Urban Institute: Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/413135-New-Provider-Networks-in-New-Health-Plans.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

7. Feibel C. Patients With Low-Cost Insurance Struggle to Find Specialists. National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/07/16/331419293/patients-with-low-cost-insurance-struggle-to-find-specialists. Published July 16, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

8. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preexisting Condition Exclusions, Lifetime and Annual Limits, Rescissions, and Patient Protections. US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.regulations.go/#!documentDetail;D=HHS-OS-2010-0014-0001. Published June 28, 2010. Accessed September 9, 2014.

mmmm

When I last wrote about the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in May 2014, I focused on the contraception issue. Since then, the US Supreme Court ruled, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, that closely held, for-profit companies with religious objections to covering birth control can opt out of the requirement to provide contraceptive coverage to their employees.

In this article, I explore that decision and what it means for women’s health. I also present data on the uninsured rate in the United States, which has dropped significantly since enactment of the ACA, and I discuss one increasingly common barrier to access to care—the use of narrow networks by insurers.

A corporation now can hold a religious belief

The Supreme Court’s majority 5-4 ruling recognized, for the first time, that a for-profit corporation can hold a religious belief, but the Court limited this claim to closely held corporations. The Court also decided that the ACA placed a substantial burden on the corporations’ religious beliefs and concluded that there are less burdensome ways to accomplish the law’s intent, rendering the contraceptive coverage provision in the ACA in violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). The Court limited its ruling to the contraceptive coverage requirement, essentially turning the requirement into an option for many employers.

Are contraceptives abortifacients?

The religious belief at the center of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby was that life begins at conception, which the Green family—the owners of Hobby Lobby—equate to fertilization. Hobby Lobby’s attorneys also asserted that four contraceptives approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and included in the ACA mandate may prevent implantation of a fertilized egg, thereby constituting abortion.

Although there is no scientific answer as to when life begins, ACOG and the medical community agree that pregnancy begins at implantation. In its amicus brief to the US Supreme Court, ACOG asserted the medical community’s consensus that the four contraceptives prevent pregnancy rather than end it, and are not abortifacients:

- emergency contraceptive pills: levonorgestrel (Plan B) and its generic equivalents and ulipristal acetate (ella)

- the copper IUD (ParaGard)

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (Mirena, Skyla).

What is a closely held corporation?

In general, according to the Pew Research Center, a closely held corporation is a private company (not publicly traded) with a limited number of shareholders. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), an important source, defines a closely held corporation as one in which more than half of the stock is owned (directly or indirectly) by five or fewer individuals at any time in the second half of the year.

“S” corporations are also considered closely held. These are corporations with 100 or fewer shareholders, with all members of the same family counted as one shareholder. “S” corporations don’t pay income tax; their shareholders pay tax on their personal returns, based on the corporations’ profits and losses.

Hobby Lobby is organized as an “S” corporation. According to the IRS, in 2011, there were 4,158,572 “S” corporations, 99.4% of them with 10 or fewer shareholders.1

The US Census Bureau estimates that, in 2012, about 2.9 million “S” corporations employed more than 29 million people. Many closely held corporations are quite large.2 According to the Pew Research Center, family-owned Cargill employs 140,000 people and had $136.7 billion in revenue in fiscal 2013. Hobby Lobby has estimated revenues of $3.3 billion and 23,000 employees.2

What’s next?

ACOG helped secure coverage of contraceptives in the ACA and is working with the US Congress and our women’s health partners to restore this important care. Days after the Supreme Court decision, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) introduced the Protect Women’s Health from Corporate Interference Act, S. 2578, with 46 cosponsors as of this writing. ACOG fully supports this bill, also known as the “Not My Boss’ Business Bill,” which would reestablish the contraceptive coverage mandate as well as other care required by federal law. This bill still maintains the exemption from contraceptive coverage for houses of worship and the accommodation for religious nonprofits.

In introducing her bill, Senator Murray pointed out that “the contraceptive coverage requirement has already made a tremendous difference in women’s lives—24 million more prescriptions for oral contraceptives were filled with no copay in 2013 than in 2012, and women have saved $483 million in out-of-pocket costs for oral contraceptives.”3

Uninsured rate is declining

The Commonwealth Fund shows that, from July–September 2013 to April–June 2014, the nation’s uninsured rate fell from 20% to 15%, resulting in 9.5 million fewer uninsured adults.4 The biggest drop occurred among young adults, with the uninsured rate falling from 28% to 18%, and in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion, where uninsured rates fell from 28% to 17%.4

States that didn’t expand their Medicaid program didn’t show any noticeable change, with the uninsured rate declining only two points, from 38% to 36%.4

Coverage resulted in access to care for the majority of the newly covered. Sixty percent of people with new coverage visited a provider or hospital or paid for a prescription. Sixty-two percent of these individuals said they wouldn’t have been able to access this care before getting this coverage. Eighty-one percent of people with new coverage said they were better off now than before.4

ACA works better in some states than others

The Kaiser Family Foundation looked at four successful states—Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, and Washington state—to see what lessons can be learned. Important commonalities include the fact that the states run their own marketplace, adopted the Medi-caid expansion, and conducted extensive outreach and public education, including engaging providers in patient outreach and enrollment.5

Other tools of success were developing good marketing and branding, providing consumer-friendly assistance, and attention to systems and operations.5

How the Hobby Lobby decision affects individual states

Because the Supreme Court’s decision concerned interpretation of a federal law—the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA)—it does not supersede state laws that mandate coverage of contraceptives.

Twenty-eight states have laws or rulings requiring insurers to cover contraceptives, most of them dating from the 1990s and providing some exemption for religious insurers or plans. Only Illinois allows an exemption for secular bodies.

Although these state laws remain in effect, state officials may opt to stop enforcing them with regard to certain companies. For example, after the Hobby Lobby decision, Wisconsin officials announced that they no longer will enforce contraceptive coverage when a company has a religious objection.

For companies that self-fund or self-insure worker health coverage, the state coverage laws don’t apply—only federal law does. These companies do not have to adhere to state insurance mandates.

Some states have their own version of the RFRA. See the chart at right for details on a state-by-state basis.

The Supreme Court ruling also has no effect on state laws that guarantee access to emergency contraception in hospital emergency departments and that require pharmacists to dispense contraceptives.

| State | Contraceptive equity law? | Employer/insurer exemption to equity law? | Religious freedom law? |

| Alabama | ✔ | ||

| Alaska | |||

| Arizona | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Arkansas | ✔ | ✔ | |

| California | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Colorado | ✔ | ||

| Connecticut | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Delaware | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Florida | ✔ | ||

| Georgia | ✔ | ||

| Hawaii | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Idaho | ✔ | ||

| Illinois | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Indiana | |||

| Iowa | ✔ | ||

| Kansas | |||

| Kentucky | ✔ | ||

| Louisiana | ✔ | ||

| Maine | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Maryland | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Massachusetts | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Michigan | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Minnesota | |||

| Mississippi | ✔ | ||

| Missouri | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Montana | ✔ | ||

| Nebraska | |||

| Nevada | ✔ | ✔ | |

| New Hampshire | ✔ | ||

| New Jersey | ✔ | ✔ | |

| New Mexico | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| New York | ✔ | ✔ | |

| North Carolina | ✔ | ✔ | |

| North Dakota | |||

| Ohio | |||

| Oklahoma | ✔ | ||

| Oregon | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Pennsylvania | ✔ | ||

| Rhode Island | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| South Carolina | ✔ | ||

| South Dakota | |||

| Tennessee | ✔ | ||

| Texas | ✔ | ||

| Utah | |||

| Vermont | ✔ | ||

| Virginia | ✔ | ||

| Washington | ✔ | ||

| West Virginia | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Wisconsin | ✔ | ||

| Wyoming | |||

| TOTAL | 28 | 20 | 18 |

Narrow networks limit access to care

Huge concerns abound regarding implementation and real-life experiences related to the ACA. A number of them—high deductibles, low payment rates, limited access to physicians, long drive and wait times—can be related to “narrow networks.” Insurers exclude certain providers and offer all providers lower payment rates (which leads some physicians to drop out of the plan); they also create tiers (charging consumers lower copays and deductibles for using inner-tier preferred providers and high out-of-pocket costs for using other providers, even though they may be in the network).

Narrow networks work for insurers as an effective tool for lowering provider payment rates to keep premiums low and gain market share. The narrower the network, the lower are physician payments and premiums.

The ACA promises expanded access to high-quality, affordable health care for millions of Americans—a promise being compromised in many areas of the country through narrow networks. In these instances, insurers offering new plans in a health-care marketplace limit patient access to the numbers, types, and locations of physicians and hospitals covered under certain plans. Insurers typically offer patients low premiums, offer selected providers a high volume of patients at low payment levels, and exclude other providers whom the insurer deems to be high-cost.

Narrow networks aren’t new

As with so many elements of the ACA, narrow networks aren’t a new phenomenon. Many of us remember the public relations price that HMOs paid in the 1980s and 1990s for exceedingly limiting patients’ access to care while charging low premiums. The consumer outcry led the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to urge states to require managed-care plans to maintain adequate networks, the approach adopted by the federal government in the ACA.6

The pendulum swung in the next decade to broader networks in which consumers had much greater access, but premiums increased by an average of 11% per year.6 Employers then pushed insurers to reduce premium costs, leading back to narrow networks in the years just before the ACA. Narrow network plans accounted for 23% of all employer-sponsored plans in 2012, up from 15% in 2007.6

Increasing consolidation contributes to narrow networks

The trend toward narrower networks is also linked to increasing consolidation in health care. As health systems grow and individual or small group practices disappear, insurers rely on being able to credibly threaten to exclude systems and big groups from their networks as leverage in payment negotiations. By restricting the choice of providers in a plan, the insurer can promise more customers for the doctors and hospitals that are included, and negotiate lower payments to those providers.

The downside for physicians is clear:

- low payment rates

- exclusion from networks and coverage

- inability to refer patients to providers the physician determines to be best for that patient’s needs.

- The downside for patients:

- If they have to go out of network to get needed care, they may end up paying high out-of-pocket costs

- If they delay or forego care, their health may suffer significantly.

The insurance industry’s position is that patients have choices. Plans with access to more hospitals and specialists are available but usually at a higher price.

Narrow networks are one way to achieve low premiums

In the months leading up to ACA enactment, insurers got to work developing plans designed to be sold on the exchanges that would attract consumers through low-cost premiums and still maximize profits, especially now that insurers, under the ACA, are barred from excluding sick enrollees or increasing premiums for women, in addition to other important protections.

In previous articles, we’ve explored these landmark protections. Insurers in the individual market used to be able to keep premiums relatively low, and profits up, through use of preexisting coverage exclusions, benefit exclusions including noncoverage for maternity care or prescription drugs, and high cost sharing. Not anymore.

Since enactment of the ACA, narrow networks seem to be the preferred, and most effective, payment negotiation tool of many insurers offering plans through the exchanges, reflecting the trend we’re already seeing in the private health insurance marketplace.

NPR spotlights the difficulty of finding a specialist

The consumer and provider problems of narrow networks have been gaining attention in the media. In July, the National Public Radio (NPR) Web site carried an article entitled, “Patients with low-cost insurance struggle to find specialists,” with a key subtitle: “So you found an exchange plan. But can you find a provider?”7

In the NPR article, author Carrie Feibel reported on the situation in a majority-immigrant area of southwest Houston.

There, many patients at the local clinic have health insurance coverage for the first time, an important step toward healthier lives for themselves and their families. But many people in need of a specialist are learning that their insurance card doesn’t guarantee them access to a needed surgeon or hospital. They’ve purchased a narrow-network insurance plan, with a low premium but few specialists who accept that insurance.7

The two largest hospital chains in Houston—Houston Methodist and Memorial Hermann—as well as Houston’s MD Anderson Cancer Center, don’t participate in the Blue Cross Blue Shield HMO Silver plan, a plan popular with low-income consumers because of its low premium.7

Will the government take action?

The ACA actually guards against overly narrow networks and established the first national standard for network adequacy—a standard that needs fuller development, for sure. Plans sold on the exchanges are required to establish networks that include, among other providers, essential community providers, who typically care for mostly low-income and medically underserved populations. Networks also must include sufficient numbers and types of providers, including “providers that specialize in mental health and substance abuse services, to assure that all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay.”8

Insurers also must provide people who are considering purchasing their products with an accurate directory—both online and a hard copy—identifying providers not accepting new patients in the network. And plans are prohibited from charging out-of-network cost-sharing for emergency services.

Much of the oversight and many of the details—how much is adequate? what is unreasonable?—are left to the states, many of which have years of experience grappling with the downsides and delicate balance of networks.

The Urban Institute points out that Vermont and Delaware set standards for maximum geographic distance and drive times for primary care services. In California, plans must make it easy for consumers to reach urban providers on public transportation.6

Professional societies are taking note

Today, the misuse of narrow networks by exchange plans also has gotten the attention of the American Medical Association, ACOG, and many other national medical specialty societies, in addition to the states and federal government.

The trick, many health-care policy experts agree, is to find the right balance. How broad can the network be before premiums soar? Most agree that consumers must be able to choose between plans with confidence, without any cost or access surprises, meaning much better transparency. And many agree that provider quality, in addition to cost, has to find its way into the equation.

This year, the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, a part of the federal Department of Health and Human Services created by the ACA to investigate these kinds of issues, is investigating access to hospital systems, mental health services, oncology, and primary care providers and is developing time, distance, and other standards that insurers will have to adhere to.

Employer groups oppose strong standards or limits on narrow networks. Recently, representatives of the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Retail Federation, and others warned Congress to stay out of this fight. They understand that more generous networks mean higher premiums. These employer representative groups prefer to strengthen consumer protections like directories and keep low the cost of health insurance that they provide for their employees.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the work and expertise of ACOG's state government affairs team for the state analysis—Kathryn Moore, Director, and Kate Vlach, Senior Manager—as well as advocacy partners.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

mmmm

When I last wrote about the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in May 2014, I focused on the contraception issue. Since then, the US Supreme Court ruled, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, that closely held, for-profit companies with religious objections to covering birth control can opt out of the requirement to provide contraceptive coverage to their employees.

In this article, I explore that decision and what it means for women’s health. I also present data on the uninsured rate in the United States, which has dropped significantly since enactment of the ACA, and I discuss one increasingly common barrier to access to care—the use of narrow networks by insurers.

A corporation now can hold a religious belief