User login

Hospitalist Explains Benefits of Bundling, Other Integration Strategies

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Why It's Important to Have Supportive Colleagues

Hospitalist-Focused Strategies to Address Medicare's Expanded Quality, Efficiency Measures

VBP. ACO. HAC. EHR. Suddenly, Medicare-derived acronyms are everywhere, and many of them are attached to a growing set of programs aimed at boosting efficiency and quality. Some are optional; others are mandatory. Some have carrots as incentives; others have sticks. Some seem well-designed; others seemingly work at cross-purposes.

Love or hate these initiatives, the combined time, money, and resources needed to address all of them could put hospitals and hospitalists under considerable duress.

“It can either prove or dismantle the whole hospitalist movement,” says Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va. “Hospitals expect us to be agile and adapt to the pressures to keep them alive. If we cannot adapt and provide that, then why give us a job?”

Whether or not the focus is on lowering readmission rates, decreasing the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, or improving efficiencies, Dr. Hazen tends to lump most of the sticks and carrots together. “I throw them all into one basket because for the most part, they’re all reflective of good care,” he says.

The basket is growing, however, and the bundle of sticks could deliver a financial beating to the unwary.

—Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; SHM Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee member; co-founder and past president of SHM; author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column

At What Cost?

For the lowest-performing hospitals, the top readmission penalties will grow to 2% of Medicare reimbursements in fiscal year 2014 and 3% in 2015. Meanwhile, CMS’ Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HAC) program will begin assessing a 1% penalty on the worst performing hospitals in 2015, and the amount withheld under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program will reach 2% in 2017 (top-performing hospitals can recoup the withhold and more, depending on performance). By that year, the three programs alone could result in a 6% loss of reimbursements.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee, estimates that by 2017, the total at-risk payments could reach about $10 million for a 650-bed academic medical center. The tally for a 90-bed community hospital, he estimates, might run a bit less than $1 million. Although the combined penalty is probably enough to get the attention of most hospitals, very few institutions are likely to be dinged for the entire amount.

Nevertheless, the cumulative loss of reimbursements could be a tipping point for hospitals already in dire straits. “It’s possible that some low-margin hospitals that are facing big penalties could actually have their solvency threatened,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “If hospitals that are a vital part of the community are threatened with insolvency because of these programs, we may need to take a second look at how we structure the penalties.”

The necessary investment in infrastructure, he says, could prove to be a far bigger concern—at least initially.

“What is more expensive is just putting out the effort to do the work to improve and perform well under these programs,” says Dr. Whitcomb, co-founder and past president of SHM and author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column. “That’s a big unreported hidden expense of all of these programs.”

With the fairly rapid implementation of multiple measures mandated by the Accountable Care Act, Medicare may be disinclined to dramatically ramp up the programs in play until it has a better sense of what’s working well. Then again, analysts like Laurence Baker, PhD, professor of health research and policy at Stanford University, say it’s doubtful that the agency will scale back its efforts given the widely held perception that plenty of waste can yet be wrung from the system.

“If I was a hospitalist, I would expect more of this coming,” Dr. Baker says.

Of course, rolling out new incentive programs is always a difficult balancing act in which the creators must be careful not to focus too much attention on the wrong measure or create unintended disincentives.

“That’s one of the great challenges: making a program that’s going to be successful when we know that people will do what’s measured and maybe even, without thinking about it, do less of what’s not measured. So we have to be careful about that,” Dr. Baker says.

—Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pa.

Out of Alignment

Beyond cost and infrastructure, the proliferation of new measures also presents challenges for alignment. Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive at Lancaster General Hospital in Lancaster, Pa., says the targets are changing so rapidly that tension can arise between hospitals and hospitalists in aligning expectations about priorities and considering how much time, resources, and staffing will be required to address them.

Likewise, the impetus to install new infrastructure can sometimes have unintended consequences, as Dr. Duke has seen firsthand with his hospital’s recent implementation of electronic health records (EHRs).

“In many ways, the electronic health record has changed the dynamic of rounding between physicians and nurses, and it’s really challenging communication,” he says. How so? “Because people spend more time communicating with the computer than they do talking to one another,” he says. The discordant communication, in turn, can conspire against a clear plan of care and overall goals as well as challenge efforts that emphasize a team-based approach.

Despite federal meaningful-use incentives, a recent survey also suggested that a majority of healthcare practices still may not achieve a positive return on investment for EHRs unless they can figure out how to use the systems to increase revenue.1 A minority of providers have succeeded by seeing more patients every day or by improving their billing process so the codes are more accurate and fewer claims are rejected.

Similarly, hospitalists like Dr. Hazen contend that some patient-satisfaction measures in the HCAHPS section of the VBP program can work against good clinical care. “That one drives me crazy because we’re not waiters or waitresses in a five-star restaurant,” he says. “Health care is complicated; it’s not like sending back a bowl of cold soup the way you can in a restaurant.”

Increasing satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital longer than warranted or leaving in a Foley catheter for patient convenience, for example, can negatively impact actual outcomes.

“Physicians and nurses get put in this catch-22 where we have to choose between patient satisfaction and by-the-book clinical care,” Dr. Hazen says. “And our job is to try to mitigate that, but you’re kind of damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

A new study, on the other hand, suggests that HCAHPS scores reflecting lower staff responsiveness are associated with an increased risk of HACs like central line–associated bloodstream infections and that lower scores may be a symptom of hospitals “with a multitude of problems.”2

A 10-Step Program

As existing rules and metrics are revised, new ones added, and others merged or discontinued, hospitalists are likely to encounter more hiccups and headaches. So what’s the solution? Beyond establishing good personal habits like hand-washing when entering and leaving a patient’s room, hospitalist leaders and healthcare analysts point to 10 strategies that may help keep HM providers from getting squeezed by all the demands:

1) Keep everyone on the same page. Because hospitals and health systems often take a subset of CMS core measures and make them strategic priorities, Dr. Whitcomb says hospitalists must thoroughly understand their own institutions’ internal system-level quality and safety goals. He stresses the need for hospitalists to develop and maintain close working connections with their organization’s safety- and quality-improvement (QI) teams “to understand exactly what the rules of the road are.”

Dr. Whitcomb says hospitals should compensate hospitalists for time spent working with these teams on feasible solutions. Hospitalist representatives can then champion specific safety or quality issues and keep them foremost in the minds of their colleagues. “I’m a big believer in paying people to do that work,” he says.

2) Take a wider view. It’s clear that most providers wouldn’t have chosen some of the performance indicators that Medicare and other third-party payors are asking them to meet, and many physicians have been more focused on outcomes than on clinical measures. Like it or not, however, thriving in the new era of health care means accepting more benchmarks. “We’ve had to broaden our scope to say, ‘OK, these other things matter, too,’” Dr. Duke says.

3) Use visual cues. Hospitalists can’t rely on memory to keep track of the dozens of measures for which they are being held accountable. “Every hospitalist program should have a dashboard of priority measures that they’re paying attention to and that’s out in front of them on a regular basis,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It could be presented to them at monthly meetings, or it could be in a prominent place in their office, but there needs to be a set of cues.”

4) Use bonuses for alignment. Dr. Hazen says hospitals also may find success in using bonuses as a positive reinforcement for well-aligned care. Inova Fairfax’s bonuses include a clinical component that aligns with many of CMS’s core measures, and the financial incentives ensure that discharge summaries are completed and distributed in a timely manner.

5) Emphasize a team approach. Espousing a multidisciplinary approach to care can give patients the confidence that all providers are on the same page, thereby aiding patient-satisfaction scores and easing throughput. And as Dr. Hazen points out, avoiding a silo mentality can pay dividends for improving patient safety.

6) Offer the right information. Tierza Stephan, MD, regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says Allina has worked hard to ensure that hospitalists complete their discharge summaries within 24 hours of a patient’s release from the hospital. Beyond timeliness, the health system is emphasizing content that informs without overwhelming the patient, caregiver, or follow-up provider with unnecessary details.

The discharge summary, for example, includes a section called “Recommendations for the Outpatient Provider,” which provides a checklist of sorts so those providers don’t miss the forest for the trees. The same is true for patients. “The hospital is probably not the best place to be educating patients, so we really focus more on patient instruction at discharge and then timely follow-up,” Dr. Stephan says.

In addition to allowing better care coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, she says, “it cuts across patient experience and readmissions, and it helps patients to be engaged because they have very clear, easy-to-read information.” Paying attention to such details may have outsized impacts: In a recent study, researchers found that patients who are actively engaged in their own health care are significantly less costly to treat, on average.3

7) Follow through after discharge. Inova Fairfax is setting up an outpatient follow-up clinic as a safety net for patients at the highest risk of being readmitted. Many of these target patients are uninsured or underinsured and battling complex medical problems like heart failure or pneumonia. Establishing a physical location for follow-ups and direct communication with primary-care providers, the hospital hopes, might reduce noncompliance among these outpatients and thereby curtail subsequent readmissions.

8) Optimize EHR. When optimized, experts say, electronic medical records can help hospitals ensure that their providers are following core measures and preventing hospital-acquired conditions while leaving channels of communication open and keeping revenue streams flowing.

“Luckily, we just switched to electronic medical records so we can monitor who has a Foley catheter in, who does or doesn’t have DVT prophylaxis, because even really good docs sometimes make these knucklehead mistakes every once in a while,” Dr. Hazen says. “So we try to use systems to back ourselves up. But for the most part, there’s just no substitute for having good docs do the right thing and documenting that.”

9) Bundle up. Although bundled payments represent yet another CMS initiative, Dr. Duke says the model has the potential to reduce waste, standardize care, and monitor outcomes. Lancaster General has been working on the approach for the past few years, with an initial focus on cardiovascular medicine, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. “We’re getting a lot of traction to get physicians to work together to improve care, where before there wasn’t an incentive to do this,” Dr. Duke says. “So we see this as a good thing, and I think it has potential to reduce expenses in high-cost areas.”

10) Connect the dots. Joane Goodroe, an independent healthcare consultant based in Atlanta, says CMS expects providers to connect the dots and combine their efforts in the separate incentive programs to maximize their resources. By providing consistent care coordination and setting patients on the right track, then, she says hospitalists might help boost savings across the board—a benefit that wouldn’t necessarily be apparent based solely on improved quality metrics in specific programs.

Even here, though, the current fee-for-service model can create awkward side effects. For example, Goodroe recommends following the path that many care groups delving into accountable care and bundled payment systems are already taking: connecting those models to efforts aimed at reducing hospital readmissions. Without the proper financial incentives, however, those efforts may be constrained due to a significant increase in expended resources and a potential decrease in overall revenues.

Some of the kinks may work themselves out of the system over time, but experts say the era of multiple metrics—and additional pressure—is just beginning. Combined, they will require providers to be much better at working as a system and coordinating care across multiple environments beyond the hospital, Dr. Stephan says.

One main question boils down to this, she says: “How do we get more efficient as a system and eliminate waste? I think the hospitalists really play a vital role, and it’s mainly through communication and transfer of information. Hospitalists have to be really well-connected with the different physicians and venues that send the patients into the hospital so that we’re not duplicating services and so that we can get right to the crux of the problem.”

Doing so, regardless of which CMS program is on tap, may be the very best way to avoid getting squeezed.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Adler-Milstein J, Green CE, Bates DW. A survey analysis suggests that electronic health records will yield revenue gains for some practices and losses for many. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):562-570.

- Saman DM, Kavanagh KT, Johnson B, Lutfiyya MN. Can inpatient hospital experiences predict central line-associated bloodstream infections? PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61097.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores.’ Health Affairs. 2013; 32(2):216-222.

VBP. ACO. HAC. EHR. Suddenly, Medicare-derived acronyms are everywhere, and many of them are attached to a growing set of programs aimed at boosting efficiency and quality. Some are optional; others are mandatory. Some have carrots as incentives; others have sticks. Some seem well-designed; others seemingly work at cross-purposes.

Love or hate these initiatives, the combined time, money, and resources needed to address all of them could put hospitals and hospitalists under considerable duress.

“It can either prove or dismantle the whole hospitalist movement,” says Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va. “Hospitals expect us to be agile and adapt to the pressures to keep them alive. If we cannot adapt and provide that, then why give us a job?”

Whether or not the focus is on lowering readmission rates, decreasing the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, or improving efficiencies, Dr. Hazen tends to lump most of the sticks and carrots together. “I throw them all into one basket because for the most part, they’re all reflective of good care,” he says.

The basket is growing, however, and the bundle of sticks could deliver a financial beating to the unwary.

—Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; SHM Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee member; co-founder and past president of SHM; author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column

At What Cost?

For the lowest-performing hospitals, the top readmission penalties will grow to 2% of Medicare reimbursements in fiscal year 2014 and 3% in 2015. Meanwhile, CMS’ Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HAC) program will begin assessing a 1% penalty on the worst performing hospitals in 2015, and the amount withheld under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program will reach 2% in 2017 (top-performing hospitals can recoup the withhold and more, depending on performance). By that year, the three programs alone could result in a 6% loss of reimbursements.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee, estimates that by 2017, the total at-risk payments could reach about $10 million for a 650-bed academic medical center. The tally for a 90-bed community hospital, he estimates, might run a bit less than $1 million. Although the combined penalty is probably enough to get the attention of most hospitals, very few institutions are likely to be dinged for the entire amount.

Nevertheless, the cumulative loss of reimbursements could be a tipping point for hospitals already in dire straits. “It’s possible that some low-margin hospitals that are facing big penalties could actually have their solvency threatened,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “If hospitals that are a vital part of the community are threatened with insolvency because of these programs, we may need to take a second look at how we structure the penalties.”

The necessary investment in infrastructure, he says, could prove to be a far bigger concern—at least initially.

“What is more expensive is just putting out the effort to do the work to improve and perform well under these programs,” says Dr. Whitcomb, co-founder and past president of SHM and author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column. “That’s a big unreported hidden expense of all of these programs.”

With the fairly rapid implementation of multiple measures mandated by the Accountable Care Act, Medicare may be disinclined to dramatically ramp up the programs in play until it has a better sense of what’s working well. Then again, analysts like Laurence Baker, PhD, professor of health research and policy at Stanford University, say it’s doubtful that the agency will scale back its efforts given the widely held perception that plenty of waste can yet be wrung from the system.

“If I was a hospitalist, I would expect more of this coming,” Dr. Baker says.

Of course, rolling out new incentive programs is always a difficult balancing act in which the creators must be careful not to focus too much attention on the wrong measure or create unintended disincentives.

“That’s one of the great challenges: making a program that’s going to be successful when we know that people will do what’s measured and maybe even, without thinking about it, do less of what’s not measured. So we have to be careful about that,” Dr. Baker says.

—Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pa.

Out of Alignment

Beyond cost and infrastructure, the proliferation of new measures also presents challenges for alignment. Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive at Lancaster General Hospital in Lancaster, Pa., says the targets are changing so rapidly that tension can arise between hospitals and hospitalists in aligning expectations about priorities and considering how much time, resources, and staffing will be required to address them.

Likewise, the impetus to install new infrastructure can sometimes have unintended consequences, as Dr. Duke has seen firsthand with his hospital’s recent implementation of electronic health records (EHRs).

“In many ways, the electronic health record has changed the dynamic of rounding between physicians and nurses, and it’s really challenging communication,” he says. How so? “Because people spend more time communicating with the computer than they do talking to one another,” he says. The discordant communication, in turn, can conspire against a clear plan of care and overall goals as well as challenge efforts that emphasize a team-based approach.

Despite federal meaningful-use incentives, a recent survey also suggested that a majority of healthcare practices still may not achieve a positive return on investment for EHRs unless they can figure out how to use the systems to increase revenue.1 A minority of providers have succeeded by seeing more patients every day or by improving their billing process so the codes are more accurate and fewer claims are rejected.

Similarly, hospitalists like Dr. Hazen contend that some patient-satisfaction measures in the HCAHPS section of the VBP program can work against good clinical care. “That one drives me crazy because we’re not waiters or waitresses in a five-star restaurant,” he says. “Health care is complicated; it’s not like sending back a bowl of cold soup the way you can in a restaurant.”

Increasing satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital longer than warranted or leaving in a Foley catheter for patient convenience, for example, can negatively impact actual outcomes.

“Physicians and nurses get put in this catch-22 where we have to choose between patient satisfaction and by-the-book clinical care,” Dr. Hazen says. “And our job is to try to mitigate that, but you’re kind of damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

A new study, on the other hand, suggests that HCAHPS scores reflecting lower staff responsiveness are associated with an increased risk of HACs like central line–associated bloodstream infections and that lower scores may be a symptom of hospitals “with a multitude of problems.”2

A 10-Step Program

As existing rules and metrics are revised, new ones added, and others merged or discontinued, hospitalists are likely to encounter more hiccups and headaches. So what’s the solution? Beyond establishing good personal habits like hand-washing when entering and leaving a patient’s room, hospitalist leaders and healthcare analysts point to 10 strategies that may help keep HM providers from getting squeezed by all the demands:

1) Keep everyone on the same page. Because hospitals and health systems often take a subset of CMS core measures and make them strategic priorities, Dr. Whitcomb says hospitalists must thoroughly understand their own institutions’ internal system-level quality and safety goals. He stresses the need for hospitalists to develop and maintain close working connections with their organization’s safety- and quality-improvement (QI) teams “to understand exactly what the rules of the road are.”

Dr. Whitcomb says hospitals should compensate hospitalists for time spent working with these teams on feasible solutions. Hospitalist representatives can then champion specific safety or quality issues and keep them foremost in the minds of their colleagues. “I’m a big believer in paying people to do that work,” he says.

2) Take a wider view. It’s clear that most providers wouldn’t have chosen some of the performance indicators that Medicare and other third-party payors are asking them to meet, and many physicians have been more focused on outcomes than on clinical measures. Like it or not, however, thriving in the new era of health care means accepting more benchmarks. “We’ve had to broaden our scope to say, ‘OK, these other things matter, too,’” Dr. Duke says.

3) Use visual cues. Hospitalists can’t rely on memory to keep track of the dozens of measures for which they are being held accountable. “Every hospitalist program should have a dashboard of priority measures that they’re paying attention to and that’s out in front of them on a regular basis,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It could be presented to them at monthly meetings, or it could be in a prominent place in their office, but there needs to be a set of cues.”

4) Use bonuses for alignment. Dr. Hazen says hospitals also may find success in using bonuses as a positive reinforcement for well-aligned care. Inova Fairfax’s bonuses include a clinical component that aligns with many of CMS’s core measures, and the financial incentives ensure that discharge summaries are completed and distributed in a timely manner.

5) Emphasize a team approach. Espousing a multidisciplinary approach to care can give patients the confidence that all providers are on the same page, thereby aiding patient-satisfaction scores and easing throughput. And as Dr. Hazen points out, avoiding a silo mentality can pay dividends for improving patient safety.

6) Offer the right information. Tierza Stephan, MD, regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says Allina has worked hard to ensure that hospitalists complete their discharge summaries within 24 hours of a patient’s release from the hospital. Beyond timeliness, the health system is emphasizing content that informs without overwhelming the patient, caregiver, or follow-up provider with unnecessary details.

The discharge summary, for example, includes a section called “Recommendations for the Outpatient Provider,” which provides a checklist of sorts so those providers don’t miss the forest for the trees. The same is true for patients. “The hospital is probably not the best place to be educating patients, so we really focus more on patient instruction at discharge and then timely follow-up,” Dr. Stephan says.

In addition to allowing better care coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, she says, “it cuts across patient experience and readmissions, and it helps patients to be engaged because they have very clear, easy-to-read information.” Paying attention to such details may have outsized impacts: In a recent study, researchers found that patients who are actively engaged in their own health care are significantly less costly to treat, on average.3

7) Follow through after discharge. Inova Fairfax is setting up an outpatient follow-up clinic as a safety net for patients at the highest risk of being readmitted. Many of these target patients are uninsured or underinsured and battling complex medical problems like heart failure or pneumonia. Establishing a physical location for follow-ups and direct communication with primary-care providers, the hospital hopes, might reduce noncompliance among these outpatients and thereby curtail subsequent readmissions.

8) Optimize EHR. When optimized, experts say, electronic medical records can help hospitals ensure that their providers are following core measures and preventing hospital-acquired conditions while leaving channels of communication open and keeping revenue streams flowing.

“Luckily, we just switched to electronic medical records so we can monitor who has a Foley catheter in, who does or doesn’t have DVT prophylaxis, because even really good docs sometimes make these knucklehead mistakes every once in a while,” Dr. Hazen says. “So we try to use systems to back ourselves up. But for the most part, there’s just no substitute for having good docs do the right thing and documenting that.”

9) Bundle up. Although bundled payments represent yet another CMS initiative, Dr. Duke says the model has the potential to reduce waste, standardize care, and monitor outcomes. Lancaster General has been working on the approach for the past few years, with an initial focus on cardiovascular medicine, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. “We’re getting a lot of traction to get physicians to work together to improve care, where before there wasn’t an incentive to do this,” Dr. Duke says. “So we see this as a good thing, and I think it has potential to reduce expenses in high-cost areas.”

10) Connect the dots. Joane Goodroe, an independent healthcare consultant based in Atlanta, says CMS expects providers to connect the dots and combine their efforts in the separate incentive programs to maximize their resources. By providing consistent care coordination and setting patients on the right track, then, she says hospitalists might help boost savings across the board—a benefit that wouldn’t necessarily be apparent based solely on improved quality metrics in specific programs.

Even here, though, the current fee-for-service model can create awkward side effects. For example, Goodroe recommends following the path that many care groups delving into accountable care and bundled payment systems are already taking: connecting those models to efforts aimed at reducing hospital readmissions. Without the proper financial incentives, however, those efforts may be constrained due to a significant increase in expended resources and a potential decrease in overall revenues.

Some of the kinks may work themselves out of the system over time, but experts say the era of multiple metrics—and additional pressure—is just beginning. Combined, they will require providers to be much better at working as a system and coordinating care across multiple environments beyond the hospital, Dr. Stephan says.

One main question boils down to this, she says: “How do we get more efficient as a system and eliminate waste? I think the hospitalists really play a vital role, and it’s mainly through communication and transfer of information. Hospitalists have to be really well-connected with the different physicians and venues that send the patients into the hospital so that we’re not duplicating services and so that we can get right to the crux of the problem.”

Doing so, regardless of which CMS program is on tap, may be the very best way to avoid getting squeezed.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Adler-Milstein J, Green CE, Bates DW. A survey analysis suggests that electronic health records will yield revenue gains for some practices and losses for many. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):562-570.

- Saman DM, Kavanagh KT, Johnson B, Lutfiyya MN. Can inpatient hospital experiences predict central line-associated bloodstream infections? PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61097.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores.’ Health Affairs. 2013; 32(2):216-222.

VBP. ACO. HAC. EHR. Suddenly, Medicare-derived acronyms are everywhere, and many of them are attached to a growing set of programs aimed at boosting efficiency and quality. Some are optional; others are mandatory. Some have carrots as incentives; others have sticks. Some seem well-designed; others seemingly work at cross-purposes.

Love or hate these initiatives, the combined time, money, and resources needed to address all of them could put hospitals and hospitalists under considerable duress.

“It can either prove or dismantle the whole hospitalist movement,” says Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va. “Hospitals expect us to be agile and adapt to the pressures to keep them alive. If we cannot adapt and provide that, then why give us a job?”

Whether or not the focus is on lowering readmission rates, decreasing the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, or improving efficiencies, Dr. Hazen tends to lump most of the sticks and carrots together. “I throw them all into one basket because for the most part, they’re all reflective of good care,” he says.

The basket is growing, however, and the bundle of sticks could deliver a financial beating to the unwary.

—Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; SHM Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee member; co-founder and past president of SHM; author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column

At What Cost?

For the lowest-performing hospitals, the top readmission penalties will grow to 2% of Medicare reimbursements in fiscal year 2014 and 3% in 2015. Meanwhile, CMS’ Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HAC) program will begin assessing a 1% penalty on the worst performing hospitals in 2015, and the amount withheld under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program will reach 2% in 2017 (top-performing hospitals can recoup the withhold and more, depending on performance). By that year, the three programs alone could result in a 6% loss of reimbursements.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Performance and Measurement Reporting Committee, estimates that by 2017, the total at-risk payments could reach about $10 million for a 650-bed academic medical center. The tally for a 90-bed community hospital, he estimates, might run a bit less than $1 million. Although the combined penalty is probably enough to get the attention of most hospitals, very few institutions are likely to be dinged for the entire amount.

Nevertheless, the cumulative loss of reimbursements could be a tipping point for hospitals already in dire straits. “It’s possible that some low-margin hospitals that are facing big penalties could actually have their solvency threatened,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “If hospitals that are a vital part of the community are threatened with insolvency because of these programs, we may need to take a second look at how we structure the penalties.”

The necessary investment in infrastructure, he says, could prove to be a far bigger concern—at least initially.

“What is more expensive is just putting out the effort to do the work to improve and perform well under these programs,” says Dr. Whitcomb, co-founder and past president of SHM and author of The Hospitalist’s “On the Horizon” column. “That’s a big unreported hidden expense of all of these programs.”

With the fairly rapid implementation of multiple measures mandated by the Accountable Care Act, Medicare may be disinclined to dramatically ramp up the programs in play until it has a better sense of what’s working well. Then again, analysts like Laurence Baker, PhD, professor of health research and policy at Stanford University, say it’s doubtful that the agency will scale back its efforts given the widely held perception that plenty of waste can yet be wrung from the system.

“If I was a hospitalist, I would expect more of this coming,” Dr. Baker says.

Of course, rolling out new incentive programs is always a difficult balancing act in which the creators must be careful not to focus too much attention on the wrong measure or create unintended disincentives.

“That’s one of the great challenges: making a program that’s going to be successful when we know that people will do what’s measured and maybe even, without thinking about it, do less of what’s not measured. So we have to be careful about that,” Dr. Baker says.

—Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pa.

Out of Alignment

Beyond cost and infrastructure, the proliferation of new measures also presents challenges for alignment. Monty Duke, MD, chief physician executive at Lancaster General Hospital in Lancaster, Pa., says the targets are changing so rapidly that tension can arise between hospitals and hospitalists in aligning expectations about priorities and considering how much time, resources, and staffing will be required to address them.

Likewise, the impetus to install new infrastructure can sometimes have unintended consequences, as Dr. Duke has seen firsthand with his hospital’s recent implementation of electronic health records (EHRs).

“In many ways, the electronic health record has changed the dynamic of rounding between physicians and nurses, and it’s really challenging communication,” he says. How so? “Because people spend more time communicating with the computer than they do talking to one another,” he says. The discordant communication, in turn, can conspire against a clear plan of care and overall goals as well as challenge efforts that emphasize a team-based approach.

Despite federal meaningful-use incentives, a recent survey also suggested that a majority of healthcare practices still may not achieve a positive return on investment for EHRs unless they can figure out how to use the systems to increase revenue.1 A minority of providers have succeeded by seeing more patients every day or by improving their billing process so the codes are more accurate and fewer claims are rejected.

Similarly, hospitalists like Dr. Hazen contend that some patient-satisfaction measures in the HCAHPS section of the VBP program can work against good clinical care. “That one drives me crazy because we’re not waiters or waitresses in a five-star restaurant,” he says. “Health care is complicated; it’s not like sending back a bowl of cold soup the way you can in a restaurant.”

Increasing satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital longer than warranted or leaving in a Foley catheter for patient convenience, for example, can negatively impact actual outcomes.

“Physicians and nurses get put in this catch-22 where we have to choose between patient satisfaction and by-the-book clinical care,” Dr. Hazen says. “And our job is to try to mitigate that, but you’re kind of damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

A new study, on the other hand, suggests that HCAHPS scores reflecting lower staff responsiveness are associated with an increased risk of HACs like central line–associated bloodstream infections and that lower scores may be a symptom of hospitals “with a multitude of problems.”2

A 10-Step Program

As existing rules and metrics are revised, new ones added, and others merged or discontinued, hospitalists are likely to encounter more hiccups and headaches. So what’s the solution? Beyond establishing good personal habits like hand-washing when entering and leaving a patient’s room, hospitalist leaders and healthcare analysts point to 10 strategies that may help keep HM providers from getting squeezed by all the demands:

1) Keep everyone on the same page. Because hospitals and health systems often take a subset of CMS core measures and make them strategic priorities, Dr. Whitcomb says hospitalists must thoroughly understand their own institutions’ internal system-level quality and safety goals. He stresses the need for hospitalists to develop and maintain close working connections with their organization’s safety- and quality-improvement (QI) teams “to understand exactly what the rules of the road are.”

Dr. Whitcomb says hospitals should compensate hospitalists for time spent working with these teams on feasible solutions. Hospitalist representatives can then champion specific safety or quality issues and keep them foremost in the minds of their colleagues. “I’m a big believer in paying people to do that work,” he says.

2) Take a wider view. It’s clear that most providers wouldn’t have chosen some of the performance indicators that Medicare and other third-party payors are asking them to meet, and many physicians have been more focused on outcomes than on clinical measures. Like it or not, however, thriving in the new era of health care means accepting more benchmarks. “We’ve had to broaden our scope to say, ‘OK, these other things matter, too,’” Dr. Duke says.

3) Use visual cues. Hospitalists can’t rely on memory to keep track of the dozens of measures for which they are being held accountable. “Every hospitalist program should have a dashboard of priority measures that they’re paying attention to and that’s out in front of them on a regular basis,” Dr. Whitcomb says. “It could be presented to them at monthly meetings, or it could be in a prominent place in their office, but there needs to be a set of cues.”

4) Use bonuses for alignment. Dr. Hazen says hospitals also may find success in using bonuses as a positive reinforcement for well-aligned care. Inova Fairfax’s bonuses include a clinical component that aligns with many of CMS’s core measures, and the financial incentives ensure that discharge summaries are completed and distributed in a timely manner.

5) Emphasize a team approach. Espousing a multidisciplinary approach to care can give patients the confidence that all providers are on the same page, thereby aiding patient-satisfaction scores and easing throughput. And as Dr. Hazen points out, avoiding a silo mentality can pay dividends for improving patient safety.

6) Offer the right information. Tierza Stephan, MD, regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says Allina has worked hard to ensure that hospitalists complete their discharge summaries within 24 hours of a patient’s release from the hospital. Beyond timeliness, the health system is emphasizing content that informs without overwhelming the patient, caregiver, or follow-up provider with unnecessary details.

The discharge summary, for example, includes a section called “Recommendations for the Outpatient Provider,” which provides a checklist of sorts so those providers don’t miss the forest for the trees. The same is true for patients. “The hospital is probably not the best place to be educating patients, so we really focus more on patient instruction at discharge and then timely follow-up,” Dr. Stephan says.

In addition to allowing better care coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, she says, “it cuts across patient experience and readmissions, and it helps patients to be engaged because they have very clear, easy-to-read information.” Paying attention to such details may have outsized impacts: In a recent study, researchers found that patients who are actively engaged in their own health care are significantly less costly to treat, on average.3

7) Follow through after discharge. Inova Fairfax is setting up an outpatient follow-up clinic as a safety net for patients at the highest risk of being readmitted. Many of these target patients are uninsured or underinsured and battling complex medical problems like heart failure or pneumonia. Establishing a physical location for follow-ups and direct communication with primary-care providers, the hospital hopes, might reduce noncompliance among these outpatients and thereby curtail subsequent readmissions.

8) Optimize EHR. When optimized, experts say, electronic medical records can help hospitals ensure that their providers are following core measures and preventing hospital-acquired conditions while leaving channels of communication open and keeping revenue streams flowing.

“Luckily, we just switched to electronic medical records so we can monitor who has a Foley catheter in, who does or doesn’t have DVT prophylaxis, because even really good docs sometimes make these knucklehead mistakes every once in a while,” Dr. Hazen says. “So we try to use systems to back ourselves up. But for the most part, there’s just no substitute for having good docs do the right thing and documenting that.”

9) Bundle up. Although bundled payments represent yet another CMS initiative, Dr. Duke says the model has the potential to reduce waste, standardize care, and monitor outcomes. Lancaster General has been working on the approach for the past few years, with an initial focus on cardiovascular medicine, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. “We’re getting a lot of traction to get physicians to work together to improve care, where before there wasn’t an incentive to do this,” Dr. Duke says. “So we see this as a good thing, and I think it has potential to reduce expenses in high-cost areas.”

10) Connect the dots. Joane Goodroe, an independent healthcare consultant based in Atlanta, says CMS expects providers to connect the dots and combine their efforts in the separate incentive programs to maximize their resources. By providing consistent care coordination and setting patients on the right track, then, she says hospitalists might help boost savings across the board—a benefit that wouldn’t necessarily be apparent based solely on improved quality metrics in specific programs.

Even here, though, the current fee-for-service model can create awkward side effects. For example, Goodroe recommends following the path that many care groups delving into accountable care and bundled payment systems are already taking: connecting those models to efforts aimed at reducing hospital readmissions. Without the proper financial incentives, however, those efforts may be constrained due to a significant increase in expended resources and a potential decrease in overall revenues.

Some of the kinks may work themselves out of the system over time, but experts say the era of multiple metrics—and additional pressure—is just beginning. Combined, they will require providers to be much better at working as a system and coordinating care across multiple environments beyond the hospital, Dr. Stephan says.

One main question boils down to this, she says: “How do we get more efficient as a system and eliminate waste? I think the hospitalists really play a vital role, and it’s mainly through communication and transfer of information. Hospitalists have to be really well-connected with the different physicians and venues that send the patients into the hospital so that we’re not duplicating services and so that we can get right to the crux of the problem.”

Doing so, regardless of which CMS program is on tap, may be the very best way to avoid getting squeezed.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Adler-Milstein J, Green CE, Bates DW. A survey analysis suggests that electronic health records will yield revenue gains for some practices and losses for many. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):562-570.

- Saman DM, Kavanagh KT, Johnson B, Lutfiyya MN. Can inpatient hospital experiences predict central line-associated bloodstream infections? PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61097.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores.’ Health Affairs. 2013; 32(2):216-222.

SHM Allies with Leading Health Care Groups to Advance Hospital Patient Nutrition

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

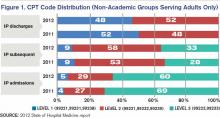

Hospitalist-Specific Data Shows Rise in Use of Some CPT Codes

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Commemorating Round-the-Clock Hospital Medicine Programs

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?