User login

Hospitalists Should Research Salary Range by Market Before Negotiating a Job Offer

I am a third-year internal-medicine resident and currently looking for a nocturnist opportunity. I have no experience in negotiating a job or salary. When I interview for a job, should I negotiate for salary? How do I know that the salary is correct and what others in the same group are getting? Thanks for the help.

–Santhosh Mannem, New York City

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Salary discussions are always intriguing, mainly because you won’t really know what everyone else is getting paid. There are several places to get some information. To begin, find out the general salary range for the market in which you want to work. Just because an annual salary might be $240,000 in Emporia, Kan., doesn’t mean a thing if you are looking for a job in Salt Lake City or Seattle. You can use the online resources through SHM (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) to paint a pretty good picture of salary by region, but remember that these are ranges only.

When I think of job offers, I like to take total compensation and break it down by category. For example, benefits are not negotiable—your employer cannot vary the health insurance coverage they provide by physician. Still, you need to consider benefits as an important part of the package. A good health insurance plan won’t mean as much to a single physician as it would to one with a family, so consider your individual needs. I strongly encourage you to make a line item for every potential benefit: health, dental, disability, life, continuing medical education (CME), professional dues, retirement plans (potentially with an employer match), malpractice insurance costs, and so on. A job with a “salary” of $300,000 but no benefits would pale in comparison to a job paying $250,000 with full benefits.

Don’t discount the value of benefits; get the numbers and assign a dollar amount. If the group is not being transparent on benefits, walk away.

With strict regard to salary, you probably will get little to no information as to what the rest of the group members are paid. Feel free to ask, but expect some vague answers. Most often, there is a fairly tight convergence of salaries within a given market, and it’s always better to interview for more than one job in the same location. You mentioned that you’d like to work as a nocturnist, which is good. These positions are recruited heavily and tend to command a higher initial salary.

Overall, your ability to negotiate a higher salary is going to be rather limited. However, there is another calculation worth mentioning: You need to find out how much you are being paid per unit of work so you can compare jobs. Here are some of the items to help you figure out a formula that works for you: annual salary, contracted shifts per year/month, pay per shift, admits/census per shift, number of weekends, and potential bonus thresholds. Use these numbers (metrics) to more accurately compare different jobs. There is no magic formula; it just depends on what is important to you, but you will get a much better picture if you combine these metrics with your benefit analysis.

As a nocturnist, I would not expect to hit any productivity metrics. If you are that busy, it’s probably a miserable job. In a business sense, nights almost always lose money.

One thing that can always be negotiated: a signing bonus and/or loan forgiveness. Often, a practice won’t want to continually offer higher starting salaries since eventually this causes wage creep across the practice. However, they can be much more flexible when it comes to “one-time” payments. This keeps the overall salary structure for the practice intact and is usually much more agreeable for your employer. As always, it’s a supply-and-demand issue, but if you are a nocturnist looking at a high-demand area, I would negotiate hard for a signing bonus and maybe even a contract-renewal bonus after your first year.

It never hurts to get creative, either. I remember negotiating my first job; I offered to sign a two-year contract (instead of one) if they would let me take off six months the first year. They said yes, I did some traveling that first year on my new salary, and I stayed with the practice for 11 years. Don’t get so caught up in salary numbers that you lose sight of what’s really important to you and whether the job would be the right fit.

Good luck and welcome to hospital medicine. You’ll love it.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

I am a third-year internal-medicine resident and currently looking for a nocturnist opportunity. I have no experience in negotiating a job or salary. When I interview for a job, should I negotiate for salary? How do I know that the salary is correct and what others in the same group are getting? Thanks for the help.

–Santhosh Mannem, New York City

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Salary discussions are always intriguing, mainly because you won’t really know what everyone else is getting paid. There are several places to get some information. To begin, find out the general salary range for the market in which you want to work. Just because an annual salary might be $240,000 in Emporia, Kan., doesn’t mean a thing if you are looking for a job in Salt Lake City or Seattle. You can use the online resources through SHM (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) to paint a pretty good picture of salary by region, but remember that these are ranges only.

When I think of job offers, I like to take total compensation and break it down by category. For example, benefits are not negotiable—your employer cannot vary the health insurance coverage they provide by physician. Still, you need to consider benefits as an important part of the package. A good health insurance plan won’t mean as much to a single physician as it would to one with a family, so consider your individual needs. I strongly encourage you to make a line item for every potential benefit: health, dental, disability, life, continuing medical education (CME), professional dues, retirement plans (potentially with an employer match), malpractice insurance costs, and so on. A job with a “salary” of $300,000 but no benefits would pale in comparison to a job paying $250,000 with full benefits.

Don’t discount the value of benefits; get the numbers and assign a dollar amount. If the group is not being transparent on benefits, walk away.

With strict regard to salary, you probably will get little to no information as to what the rest of the group members are paid. Feel free to ask, but expect some vague answers. Most often, there is a fairly tight convergence of salaries within a given market, and it’s always better to interview for more than one job in the same location. You mentioned that you’d like to work as a nocturnist, which is good. These positions are recruited heavily and tend to command a higher initial salary.

Overall, your ability to negotiate a higher salary is going to be rather limited. However, there is another calculation worth mentioning: You need to find out how much you are being paid per unit of work so you can compare jobs. Here are some of the items to help you figure out a formula that works for you: annual salary, contracted shifts per year/month, pay per shift, admits/census per shift, number of weekends, and potential bonus thresholds. Use these numbers (metrics) to more accurately compare different jobs. There is no magic formula; it just depends on what is important to you, but you will get a much better picture if you combine these metrics with your benefit analysis.

As a nocturnist, I would not expect to hit any productivity metrics. If you are that busy, it’s probably a miserable job. In a business sense, nights almost always lose money.

One thing that can always be negotiated: a signing bonus and/or loan forgiveness. Often, a practice won’t want to continually offer higher starting salaries since eventually this causes wage creep across the practice. However, they can be much more flexible when it comes to “one-time” payments. This keeps the overall salary structure for the practice intact and is usually much more agreeable for your employer. As always, it’s a supply-and-demand issue, but if you are a nocturnist looking at a high-demand area, I would negotiate hard for a signing bonus and maybe even a contract-renewal bonus after your first year.

It never hurts to get creative, either. I remember negotiating my first job; I offered to sign a two-year contract (instead of one) if they would let me take off six months the first year. They said yes, I did some traveling that first year on my new salary, and I stayed with the practice for 11 years. Don’t get so caught up in salary numbers that you lose sight of what’s really important to you and whether the job would be the right fit.

Good luck and welcome to hospital medicine. You’ll love it.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

I am a third-year internal-medicine resident and currently looking for a nocturnist opportunity. I have no experience in negotiating a job or salary. When I interview for a job, should I negotiate for salary? How do I know that the salary is correct and what others in the same group are getting? Thanks for the help.

–Santhosh Mannem, New York City

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Salary discussions are always intriguing, mainly because you won’t really know what everyone else is getting paid. There are several places to get some information. To begin, find out the general salary range for the market in which you want to work. Just because an annual salary might be $240,000 in Emporia, Kan., doesn’t mean a thing if you are looking for a job in Salt Lake City or Seattle. You can use the online resources through SHM (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) to paint a pretty good picture of salary by region, but remember that these are ranges only.

When I think of job offers, I like to take total compensation and break it down by category. For example, benefits are not negotiable—your employer cannot vary the health insurance coverage they provide by physician. Still, you need to consider benefits as an important part of the package. A good health insurance plan won’t mean as much to a single physician as it would to one with a family, so consider your individual needs. I strongly encourage you to make a line item for every potential benefit: health, dental, disability, life, continuing medical education (CME), professional dues, retirement plans (potentially with an employer match), malpractice insurance costs, and so on. A job with a “salary” of $300,000 but no benefits would pale in comparison to a job paying $250,000 with full benefits.

Don’t discount the value of benefits; get the numbers and assign a dollar amount. If the group is not being transparent on benefits, walk away.

With strict regard to salary, you probably will get little to no information as to what the rest of the group members are paid. Feel free to ask, but expect some vague answers. Most often, there is a fairly tight convergence of salaries within a given market, and it’s always better to interview for more than one job in the same location. You mentioned that you’d like to work as a nocturnist, which is good. These positions are recruited heavily and tend to command a higher initial salary.

Overall, your ability to negotiate a higher salary is going to be rather limited. However, there is another calculation worth mentioning: You need to find out how much you are being paid per unit of work so you can compare jobs. Here are some of the items to help you figure out a formula that works for you: annual salary, contracted shifts per year/month, pay per shift, admits/census per shift, number of weekends, and potential bonus thresholds. Use these numbers (metrics) to more accurately compare different jobs. There is no magic formula; it just depends on what is important to you, but you will get a much better picture if you combine these metrics with your benefit analysis.

As a nocturnist, I would not expect to hit any productivity metrics. If you are that busy, it’s probably a miserable job. In a business sense, nights almost always lose money.

One thing that can always be negotiated: a signing bonus and/or loan forgiveness. Often, a practice won’t want to continually offer higher starting salaries since eventually this causes wage creep across the practice. However, they can be much more flexible when it comes to “one-time” payments. This keeps the overall salary structure for the practice intact and is usually much more agreeable for your employer. As always, it’s a supply-and-demand issue, but if you are a nocturnist looking at a high-demand area, I would negotiate hard for a signing bonus and maybe even a contract-renewal bonus after your first year.

It never hurts to get creative, either. I remember negotiating my first job; I offered to sign a two-year contract (instead of one) if they would let me take off six months the first year. They said yes, I did some traveling that first year on my new salary, and I stayed with the practice for 11 years. Don’t get so caught up in salary numbers that you lose sight of what’s really important to you and whether the job would be the right fit.

Good luck and welcome to hospital medicine. You’ll love it.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Four pillars of a successful practice: 3. Obtain and maintain physician referrals

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

New HIPAA requirements

I’m hearing a lot of concern about the impending changes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) – which is understandable, since the Department of Health and Human Services has presented them as "the most sweeping ... since [the Act] was first implemented."

But after a careful perusal of the new rules – all 150 three-column pages of them – I can say with a modest degree of confidence that for most physicians, compliance will not be as challenging as some (such as those trying to sell you compliance-related materials) have warned.

However, you can’t simply ignore the new regulations; definitions will be more complex, security breaches more liberally defined, and potential penalties will be stiffer. Herewith the salient points:

• Business associates. The criteria for identifying "business associates" (BAs) remain the same: nonemployees, performing "functions or activities" on behalf of the "covered entity" (your practice), that involve "creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting" personal health information (PHI).

Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, companies that store or microfilm medical records, and record-shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to PHI to do their jobs.

Mail carriers, package-delivery people, cleaning services, copier repairmen, bank employees, and the like are not considered BAs, even though they might conceivably come in contact with PHI on occasion. You are required to use "reasonable diligence" in limiting the PHI that these folks may encounter, but you do not need to enter into written BA agreements with them.

Independent contractors who work within your practice – aestheticians and physical therapists, for example – are not considered BAs either, and do not need to sign a BA agreement; just train them, as you do your employees. (I’ll have more on HIPAA and OSHA training in a future column.)

What is new is the additional onus placed on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract. You are expected to use "reasonable diligence" in monitoring the work of your BAs. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is ours. Let’s say that a contractor you hire to shred old medical records throws them into a trash bin instead; under the new rules, you must assume the worst-case scenario. Previously, you would only have to notify affected patients (and the government) if there was a "significant risk of financial or reputational harm," but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported. Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines – as high as $1 million in egregious cases.

• New patient rights. Patients will now be able to restrict the PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records, and you can bill the actual costs of responding to such a request. If you have EHR, now might be a good time to work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 to 30 days – even less in some states.

• Marketing limitations. The new rule prohibits third-party-funded marketing to patients for products and services without their prior written authorization. You do not need prior authorization to market your own products and services, even when the communication is funded by a third party, but if there is any such funding, you will need to disclose it.

• Notice of privacy practices (NPP). You will need to revise your NPP to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules. You will need to explain the breach notification process, too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

• Get on it. The rules specify Sept. 23 as the effective date for the new regulations, although you have a year beyond that to revise your existing BA agreements. Extensions are possible, even likely.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

I’m hearing a lot of concern about the impending changes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) – which is understandable, since the Department of Health and Human Services has presented them as "the most sweeping ... since [the Act] was first implemented."

But after a careful perusal of the new rules – all 150 three-column pages of them – I can say with a modest degree of confidence that for most physicians, compliance will not be as challenging as some (such as those trying to sell you compliance-related materials) have warned.

However, you can’t simply ignore the new regulations; definitions will be more complex, security breaches more liberally defined, and potential penalties will be stiffer. Herewith the salient points:

• Business associates. The criteria for identifying "business associates" (BAs) remain the same: nonemployees, performing "functions or activities" on behalf of the "covered entity" (your practice), that involve "creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting" personal health information (PHI).

Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, companies that store or microfilm medical records, and record-shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to PHI to do their jobs.

Mail carriers, package-delivery people, cleaning services, copier repairmen, bank employees, and the like are not considered BAs, even though they might conceivably come in contact with PHI on occasion. You are required to use "reasonable diligence" in limiting the PHI that these folks may encounter, but you do not need to enter into written BA agreements with them.

Independent contractors who work within your practice – aestheticians and physical therapists, for example – are not considered BAs either, and do not need to sign a BA agreement; just train them, as you do your employees. (I’ll have more on HIPAA and OSHA training in a future column.)

What is new is the additional onus placed on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract. You are expected to use "reasonable diligence" in monitoring the work of your BAs. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is ours. Let’s say that a contractor you hire to shred old medical records throws them into a trash bin instead; under the new rules, you must assume the worst-case scenario. Previously, you would only have to notify affected patients (and the government) if there was a "significant risk of financial or reputational harm," but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported. Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines – as high as $1 million in egregious cases.

• New patient rights. Patients will now be able to restrict the PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records, and you can bill the actual costs of responding to such a request. If you have EHR, now might be a good time to work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 to 30 days – even less in some states.

• Marketing limitations. The new rule prohibits third-party-funded marketing to patients for products and services without their prior written authorization. You do not need prior authorization to market your own products and services, even when the communication is funded by a third party, but if there is any such funding, you will need to disclose it.

• Notice of privacy practices (NPP). You will need to revise your NPP to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules. You will need to explain the breach notification process, too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

• Get on it. The rules specify Sept. 23 as the effective date for the new regulations, although you have a year beyond that to revise your existing BA agreements. Extensions are possible, even likely.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

I’m hearing a lot of concern about the impending changes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) – which is understandable, since the Department of Health and Human Services has presented them as "the most sweeping ... since [the Act] was first implemented."

But after a careful perusal of the new rules – all 150 three-column pages of them – I can say with a modest degree of confidence that for most physicians, compliance will not be as challenging as some (such as those trying to sell you compliance-related materials) have warned.

However, you can’t simply ignore the new regulations; definitions will be more complex, security breaches more liberally defined, and potential penalties will be stiffer. Herewith the salient points:

• Business associates. The criteria for identifying "business associates" (BAs) remain the same: nonemployees, performing "functions or activities" on behalf of the "covered entity" (your practice), that involve "creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting" personal health information (PHI).

Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, companies that store or microfilm medical records, and record-shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to PHI to do their jobs.

Mail carriers, package-delivery people, cleaning services, copier repairmen, bank employees, and the like are not considered BAs, even though they might conceivably come in contact with PHI on occasion. You are required to use "reasonable diligence" in limiting the PHI that these folks may encounter, but you do not need to enter into written BA agreements with them.

Independent contractors who work within your practice – aestheticians and physical therapists, for example – are not considered BAs either, and do not need to sign a BA agreement; just train them, as you do your employees. (I’ll have more on HIPAA and OSHA training in a future column.)

What is new is the additional onus placed on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract. You are expected to use "reasonable diligence" in monitoring the work of your BAs. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is ours. Let’s say that a contractor you hire to shred old medical records throws them into a trash bin instead; under the new rules, you must assume the worst-case scenario. Previously, you would only have to notify affected patients (and the government) if there was a "significant risk of financial or reputational harm," but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported. Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines – as high as $1 million in egregious cases.

• New patient rights. Patients will now be able to restrict the PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records, and you can bill the actual costs of responding to such a request. If you have EHR, now might be a good time to work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 to 30 days – even less in some states.

• Marketing limitations. The new rule prohibits third-party-funded marketing to patients for products and services without their prior written authorization. You do not need prior authorization to market your own products and services, even when the communication is funded by a third party, but if there is any such funding, you will need to disclose it.

• Notice of privacy practices (NPP). You will need to revise your NPP to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules. You will need to explain the breach notification process, too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

• Get on it. The rules specify Sept. 23 as the effective date for the new regulations, although you have a year beyond that to revise your existing BA agreements. Extensions are possible, even likely.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Should Skyrocketing Health Care Costs Concern Hospitalists?

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Advanced-Practice Providers Have More to Offer Hospital Medicine Groups

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

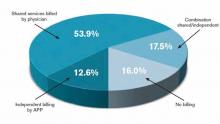

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospital Medicine Leaders Flock to HM13 for Answers, Encouragement

Ibe Mbanu, MD, MBA, MPH, became medical director of the adult hospitalist department at Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Va., about six months ago. Since then, he’s been besieged by a torrent of reform-based challenges he says make his job exponentially more difficult than that of medical directors just a few years ago.

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, and discussions about bundled payments for episodic care are changing rapidly, and as a new administrator in a group with 24 hospitalists and three nonphysician providers (NPPs), he felt he needed to attend his first SHM annual meeting to keep up.

“The landscape in health care is rapidly evolving, at a frantic pace,” Dr. Mbanu says. “I essentially came here to just try to get a condensed source of information on how to manage the changes that are coming through the pipeline, and how to effectively run my department.”

Managing a practice is a challenge, and many of the more than 2,700 attendees at HM13 said the four-day confab’s focus on the topic was a major draw. From a rebooted continuing medical education (CME) pre-course appropriately named “What Keeps You Awake at Night? Hot Topics in Hospitalist Practice Management” to dozens of breakout sessions on the topic, it’s clear that successful practice management is a concern for many hospitalists.

“Before, the drivers were pretty clear,” Dr. Mbanu says. “Volume, productivity. Now we’re switching more toward a business model that’s changing from volume to value. Trying to adapt to that change is pretty challenging.

“Now it’s critical to really understand the environment.”

Comanagement Conundrum

One particularly hot topic this year was the trend of hospitalists taking on more comanagement responsibilities for patients previously managed by other specialties, including neurology, surgery, and others. Frank Volpicelli, MD, a first-year hospitalist and instructor at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center in New York, was one of three members of his HM group that attended the “Perioperative Medicine: Medical Consultation and Co-Management” pre-course. This summer, his group is going to establish a presence in the preoperative clinic.

“We hope very strongly that we can prevent some complications, identify patients that we should be following when they come into the hospital, and help the surgeons out,” he says. “No. 1, keep them in the [operating room] more, and No. 2, get in front of some of the complications that they are less comfortable managing.”

Ralph Velazquez, MD, senior vice president of care management for OSF Healthcare System in Peoria, Ill., isn’t so sure comanagement of more and more patients is the best practice-management model moving forward. For example, as physician compensation is tied more to how much their care costs to deliver, a hospitalist comanaging a surgical patient’s elective knee replacement could be financially penalized for the cost of that person’s stay, despite having nothing to do with the most expensive portion of the bill.

“You have a financial model that says do more billings, but as you start developing analytics … you may see there is no difference between the model that’s doing more billing, in terms of improving quality, and the one that is doing less,” Dr. Velazquez says. “So if you’re getting the same amount of quality, and the only thing you’re doing is generating more cost by doing more billing, you need to reevaluate your strategy.”

He believes some patients benefit from comanagement, but HM groups have to be diligent in seeking them out.

“We look for simple solutions and one-size-fits-all,” he adds. “Comanagement in complex patients—definitely there’s a need for that. Comanagement in noncomplex patients, elective patients—there’s no need for that. It’s just additional cost. I don’t think it’s going to produce any value.”

Startup Academy

John Colombo, MD, FACP, a 30-year veteran of internal medicine who moved to HM a few years ago when one of the hospitals he worked at asked him to launch a hospitalist group, thinks bundled payments might alleviate that value conundrum. Then again, he’s not quite sure. That’s why attended his first annual meeting.

“I found it difficult starting a new program from scratch,” says Dr. Colombo, of Crozer Keystone Health System in Drexel Hill, Pa. “Even with the materials available, there’s not a lot of ‘how to do it’ out there. There’s no ‘Starting Hospitals for Dummies’ book.”

Dr. Colombo spent much of his meeting focused on recruiting, compensation, bonus structures, and scheduling concerns. He said all are important in the hospital-heavy metropolitan Philadelphia region where he works. Plus, with departures and retirements at other programs in his health system, Dr. Colombo went from no HM experience three years ago to being in charge of four HM programs.

“The biggest thing is, I wanted to make sure I hadn’t stepped in something that I shouldn’t have already,” he adds. “There’s many different ways to do things. So I’ve learned a few different ways. I found value.”

Demonstrate Value

Another way to discover value in running a practice is looking at the business side of the house, says Denice Cora-Bramble, MD, MBA, chief medical officer and executive vice president of Ambulatory & Community Health Services at the Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Bramble says many hospitalists need to understand that while clinical care is what brought them to medicine, their future paychecks depend on recognizing how to provide that care in a way that demonstrates business value.

“When you finish residency, if you have not intentionally sought out those courses or those seminars, you need to recognize that as a blind spot,” she says. “You need to fill that toolkit as it relates to the business side of medicine.

“You don’t necessarily have to know all the answers, but you need to know the right questions to ask,” she says.

Dr. Bramble adds that hospitalist leaders should take advantage of certificate programs, leadership courses, basic budgeting classes, or anything that gives them added education about the economics of healthcare.

“It all comes down to demonstrating your outcomes, demonstrating the value that you bring to that institution,” she says. “And with health-care reform, I think hospitalists are uniquely positioned to be able to partner with other areas of the hospital to look at this value-based approach.”

Gary Gammon, MD, FHM, the newly named medical director of the Hospitalist Service at FirstHealth Moore Regional Hospital in Pinehurst, N.C., is doing his part to demonstrate value to his administrators. While his group does multidisciplinary rounds on patients, one of his questions for the pre-course faculty was to make sure that system of rounding is an evidence-based practice. He’s also looking for ways to establish more hegemony to his practice to ensure the rounds are effective, regardless of which physicians and others are participating.

The feedback he received was that most people view multidisciplinary rounds as a best practice. Now, Dr. Gammon can feel more authoritative that he and his 32 hospitalists and 12 extenders are practicing HM the way it should be practiced.

“I wanted to hear just what I heard, which is the leaders in the community feel that it’s helping, feel that it’s the right thing to do, feel that there’s objective data,” he says. “This is the stuff that makes me say, ‘OK, I’ve got the same problems everybody else has.’”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Ibe Mbanu, MD, MBA, MPH, became medical director of the adult hospitalist department at Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Va., about six months ago. Since then, he’s been besieged by a torrent of reform-based challenges he says make his job exponentially more difficult than that of medical directors just a few years ago.

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, and discussions about bundled payments for episodic care are changing rapidly, and as a new administrator in a group with 24 hospitalists and three nonphysician providers (NPPs), he felt he needed to attend his first SHM annual meeting to keep up.

“The landscape in health care is rapidly evolving, at a frantic pace,” Dr. Mbanu says. “I essentially came here to just try to get a condensed source of information on how to manage the changes that are coming through the pipeline, and how to effectively run my department.”

Managing a practice is a challenge, and many of the more than 2,700 attendees at HM13 said the four-day confab’s focus on the topic was a major draw. From a rebooted continuing medical education (CME) pre-course appropriately named “What Keeps You Awake at Night? Hot Topics in Hospitalist Practice Management” to dozens of breakout sessions on the topic, it’s clear that successful practice management is a concern for many hospitalists.

“Before, the drivers were pretty clear,” Dr. Mbanu says. “Volume, productivity. Now we’re switching more toward a business model that’s changing from volume to value. Trying to adapt to that change is pretty challenging.

“Now it’s critical to really understand the environment.”

Comanagement Conundrum

One particularly hot topic this year was the trend of hospitalists taking on more comanagement responsibilities for patients previously managed by other specialties, including neurology, surgery, and others. Frank Volpicelli, MD, a first-year hospitalist and instructor at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center in New York, was one of three members of his HM group that attended the “Perioperative Medicine: Medical Consultation and Co-Management” pre-course. This summer, his group is going to establish a presence in the preoperative clinic.

“We hope very strongly that we can prevent some complications, identify patients that we should be following when they come into the hospital, and help the surgeons out,” he says. “No. 1, keep them in the [operating room] more, and No. 2, get in front of some of the complications that they are less comfortable managing.”

Ralph Velazquez, MD, senior vice president of care management for OSF Healthcare System in Peoria, Ill., isn’t so sure comanagement of more and more patients is the best practice-management model moving forward. For example, as physician compensation is tied more to how much their care costs to deliver, a hospitalist comanaging a surgical patient’s elective knee replacement could be financially penalized for the cost of that person’s stay, despite having nothing to do with the most expensive portion of the bill.

“You have a financial model that says do more billings, but as you start developing analytics … you may see there is no difference between the model that’s doing more billing, in terms of improving quality, and the one that is doing less,” Dr. Velazquez says. “So if you’re getting the same amount of quality, and the only thing you’re doing is generating more cost by doing more billing, you need to reevaluate your strategy.”

He believes some patients benefit from comanagement, but HM groups have to be diligent in seeking them out.

“We look for simple solutions and one-size-fits-all,” he adds. “Comanagement in complex patients—definitely there’s a need for that. Comanagement in noncomplex patients, elective patients—there’s no need for that. It’s just additional cost. I don’t think it’s going to produce any value.”

Startup Academy

John Colombo, MD, FACP, a 30-year veteran of internal medicine who moved to HM a few years ago when one of the hospitals he worked at asked him to launch a hospitalist group, thinks bundled payments might alleviate that value conundrum. Then again, he’s not quite sure. That’s why attended his first annual meeting.

“I found it difficult starting a new program from scratch,” says Dr. Colombo, of Crozer Keystone Health System in Drexel Hill, Pa. “Even with the materials available, there’s not a lot of ‘how to do it’ out there. There’s no ‘Starting Hospitals for Dummies’ book.”

Dr. Colombo spent much of his meeting focused on recruiting, compensation, bonus structures, and scheduling concerns. He said all are important in the hospital-heavy metropolitan Philadelphia region where he works. Plus, with departures and retirements at other programs in his health system, Dr. Colombo went from no HM experience three years ago to being in charge of four HM programs.

“The biggest thing is, I wanted to make sure I hadn’t stepped in something that I shouldn’t have already,” he adds. “There’s many different ways to do things. So I’ve learned a few different ways. I found value.”

Demonstrate Value

Another way to discover value in running a practice is looking at the business side of the house, says Denice Cora-Bramble, MD, MBA, chief medical officer and executive vice president of Ambulatory & Community Health Services at the Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Bramble says many hospitalists need to understand that while clinical care is what brought them to medicine, their future paychecks depend on recognizing how to provide that care in a way that demonstrates business value.