User login

Hospital Medicine Groups Must Determine Tolerance Levels for Workload, Night Work

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Bowel perforation causes woman’s death: $1.5M verdict

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Four pillars of a successful practice: 4. Motivate your staff

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

The success of any medical practice and any marketing program begins and ends with the staff. You can gain new patients, forge excellent relationships with referring physicians, and maintain a plentiful number of existing patients—but if you don’t have a staff that is excited, enthusiastic, and knowledgeable when answering the telephone and managing patients, your marketing plan will be ineffective, and you will be disappointed in your practice.

In this article, I review the importance of motivating employees by providing measurable, written goals in the form of a succinct, effective mission statement and policy manual. I also offer practical strategies to inspire your employees by sharing the power, vision, and rewards.

Start with your mission statement

Nearly every successful practice and every successful business has a well-defined vision, mission, goal, or objective. The mission statement should spell out the purpose of the practice and the methods of achieving it. It serves as the road map, providing direction to all members of the staff, doctors included.

The mission statement for my practice is:

We are committed to:

- excellence

- providing the best urologic health care for our patients

- persistent and consistent attention to the little details because they make a big difference.

Develop a policy manual

Every practice should have a manual that contains its rules and regulations. Ideally, this manual should also serve as a guide for any new or temporary employee who comes to work in the office.

The manual should cover job descriptions, the dress code, hours of operation, the division of office responsibilities, vacation and sick days, and emergency telephone numbers.

In my practice, we summarize our policy manual with this expectation:

Dr. Baum’s policy manual statement:

Rule #1— The patient is always right.

Rule #2— If you think the patient is wrong, reread rule #1.

ALL OTHER POLICIES ARE NULL AND VOID.

We post the mission statement in prominent places throughout the office (the reception area and most of the examination rooms, our Web site, and on a large banner in the employee lounge) to remind us and our patients of our dedication to excellent customer service.

Whenever a mistake or problem occurs, the first question we ask each other is, “Did we adhere to the mission statement and the policy statement?” Usually, we discover that we did not. We use the mission statement and the policy statement to refocus us on our number one priority: our patients.

10 LOW-COST WAYS TO MOTIVATE STAFF

A well-motivated staff creates an effective team environment. Most enlightened businesses have discovered that team management leads to increased output and productivity. Your employees want to be valued as human beings and individuals, not just as workers. The more you include them in the process of running the office, the more invested they become in helping to improve the way it works.

1. Review staff performance regularly

Employees like to know where they stand and how they can improve performance on the job. Motivated staff members appreciate feedback on their progress—or, even, their lack of it. The best way to furnish this important feedback is by conducting periodic performance reviews.

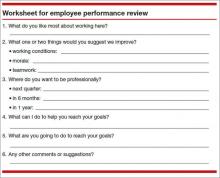

I suggest that you meet with your employees on a scheduled basis every 3 to 4 months. Give each employee a worksheet before the scheduled review (see Worksheet below), and then go over her responses during the review. You can learn a lot about what motivates her during this process.

I always end each performance review on a positive note, by telling the employee how great an asset she is to the practice. I document these meetings in the employee’s file.

2. Encourage continuing education

Just as physicians need continuing medical education to stay up to date, your staff members require continuing motivational experiences. Encourage your staff to participate in continuing education courses and support their efforts financially—you’ll get a favorable return on your investment.

I suggest that you offer to pay the fees for any seminars and classes your employees take. You may want to suggest courses in computers, social media, marketing, or any other subject area that will help the practice grow and prosper.

To make these educational experiences even more effective, ask employees to share what they have learned with other staff members. This can be done at a staff meeting. Simply ask the employee who attended a seminar or a course to share the information with the rest of the staff by briefly reviewing the course or describing what he learned and how it applies to the practice.

3. Empower your staff

Office management is complicated. Few ObGyns have a thorough understanding of all business aspects of a medical practice. Most successful ObGyns have learned to delegate the responsibility of running the office and to empower their employees to take control and assume responsibility for their decisions and actions.

In my practice, I empower any employee to make financial decisions up to a limit of $200 without consulting me. For instance, if the office needs a new telephone answering machine, I expect my employees to consider which features we need, check the machines that are available, and compare prices at the local electronics outlet, office supply store, and online retailers to find the best machine at the lowest price.

The take-home message: More than ever before, ObGyns should do what we are best trained to do—diagnose and treat diseases. Very few ObGyns are experts on fax machines. Don’t waste time on activities that your staff members can do.

4. Promote a positive mental attitude

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.” This is also true of the practice of medicine. When the doctor has a positive mental attitude, employees are motivated by the example. When a doctor is easily irritable and carries problems from home to the office and takes her frustration out on the staff, the employees will, in turn, take it out on the patients.

I have an attitude that employees are on stage. The moment they walk in the door in the morning, they have to leave all other problems and concerns behind them. They need to believe that they are responsible for making sure that each patient has a positive experience with the office at every contact point. That includes the telephone, the receptionist who welcomes patients to the practice, the nurse taking the patient into the exam room, the billing clerk who handles the patient’s bill, and, yes, the doctor, too! We all contribute to the patient’s experience, and we all need to have a positive attitude.

5. Recognize achievement

Nothing is more motivating for an employee than for the doctor to recognize his achievements and accomplishments. When an employee improves in job performance, tell him directly. You will satisfy that employee’s need for self-esteem, improve his confidence, and help him fulfill the need for self-esteem from fellow employees.

6. Show your staff that you care

Your employees need to know that you care about them not just as workers but as individuals with their own personal lives. When one of my employees is sick, or one of her family members is ill, I call her at home to check on her and make sure that she has access to adequate medical care. If someone gets sick in the office, I call another medical office and get the employee seen immediately.

7. Catch your employees doing things right

My philosophy is to praise in public, pan in private. When I catch an employee doing something right, I send a thank-you note to her home address, making sure that it arrives on a Saturday. I hope the employee will show my note to family and friends. I use a specially created card or a “thanks a million” check (a non-negotiable replication of a check that is made out to the employee and says, “Thanks a million,” with my name signed at the bottom).

You will be amazed at how appreciative the employee is that you not only recognized her superior service but took the time to put your recognition in writing.

8. Reward your staff for saving money

If a staff member comes up with an idea that saves the practice money, give her a bonus. For example, in my practice, the 15-year-old autoclave broke down. When I tried to get parts, I was informed that the machine is no longer made. The nurse in our office took the autoclave to the hospital’s biomedical engineering department, where workers installed a $30 part that saved me from buying a new $2,000 machine. The nurse deserved to be rewarded for that, so I gave her a $50 check on the spot.

I try to motivate my staff not just to earn more money for the practice but to reduce expenses, so I pay them when they identify and design money-saving ideas.

9. Involve your employees in decision making

Ask your employees for advice. Then make sure you follow it. Your staff members are on the front line; they want the office routine to go well. Include them in the decision-making process, whether the task is writing a mission statement or policy manual, determining a change in procedures, implementing an electronic health record, or meeting new job candidates. By including them, you make them feel like part of the team.

10. Have fun!

Surprise is the spice of life. Whenever you can provide an unexpected perk for your staff, you can be sure the gesture will be appreciated. For example, during a week in which two of my employees were unable to work (due to vacation and illness), the rest of us had to take up the slack. Despite being short-handed, we were able to function at regular speed and capacity without affecting the quality of care. I was so impressed by the extra effort that I arranged for a massage therapist to visit our practice at the end of the week and give everyone a 15- to 20-minute massage. It was my way of saying, “Thank you.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Encourage team spirit. It makes good business sense. When your employees have a personal investment in problem-solving and decision-making, they will go the extra mile for your patients and your practice.

This is the last article in this four-part series on promoting your practice and increasing productivity. I hope you have identified the four pillars of success for your practice—and that I have helped you understand the importance of all four pillars. They represent the strength and stability of a successful ObGyn practice.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

The success of any medical practice and any marketing program begins and ends with the staff. You can gain new patients, forge excellent relationships with referring physicians, and maintain a plentiful number of existing patients—but if you don’t have a staff that is excited, enthusiastic, and knowledgeable when answering the telephone and managing patients, your marketing plan will be ineffective, and you will be disappointed in your practice.

In this article, I review the importance of motivating employees by providing measurable, written goals in the form of a succinct, effective mission statement and policy manual. I also offer practical strategies to inspire your employees by sharing the power, vision, and rewards.

Start with your mission statement

Nearly every successful practice and every successful business has a well-defined vision, mission, goal, or objective. The mission statement should spell out the purpose of the practice and the methods of achieving it. It serves as the road map, providing direction to all members of the staff, doctors included.

The mission statement for my practice is:

We are committed to:

- excellence

- providing the best urologic health care for our patients

- persistent and consistent attention to the little details because they make a big difference.

Develop a policy manual

Every practice should have a manual that contains its rules and regulations. Ideally, this manual should also serve as a guide for any new or temporary employee who comes to work in the office.

The manual should cover job descriptions, the dress code, hours of operation, the division of office responsibilities, vacation and sick days, and emergency telephone numbers.

In my practice, we summarize our policy manual with this expectation:

Dr. Baum’s policy manual statement:

Rule #1— The patient is always right.

Rule #2— If you think the patient is wrong, reread rule #1.

ALL OTHER POLICIES ARE NULL AND VOID.

We post the mission statement in prominent places throughout the office (the reception area and most of the examination rooms, our Web site, and on a large banner in the employee lounge) to remind us and our patients of our dedication to excellent customer service.

Whenever a mistake or problem occurs, the first question we ask each other is, “Did we adhere to the mission statement and the policy statement?” Usually, we discover that we did not. We use the mission statement and the policy statement to refocus us on our number one priority: our patients.

10 LOW-COST WAYS TO MOTIVATE STAFF

A well-motivated staff creates an effective team environment. Most enlightened businesses have discovered that team management leads to increased output and productivity. Your employees want to be valued as human beings and individuals, not just as workers. The more you include them in the process of running the office, the more invested they become in helping to improve the way it works.

1. Review staff performance regularly

Employees like to know where they stand and how they can improve performance on the job. Motivated staff members appreciate feedback on their progress—or, even, their lack of it. The best way to furnish this important feedback is by conducting periodic performance reviews.

I suggest that you meet with your employees on a scheduled basis every 3 to 4 months. Give each employee a worksheet before the scheduled review (see Worksheet below), and then go over her responses during the review. You can learn a lot about what motivates her during this process.

I always end each performance review on a positive note, by telling the employee how great an asset she is to the practice. I document these meetings in the employee’s file.

2. Encourage continuing education

Just as physicians need continuing medical education to stay up to date, your staff members require continuing motivational experiences. Encourage your staff to participate in continuing education courses and support their efforts financially—you’ll get a favorable return on your investment.

I suggest that you offer to pay the fees for any seminars and classes your employees take. You may want to suggest courses in computers, social media, marketing, or any other subject area that will help the practice grow and prosper.

To make these educational experiences even more effective, ask employees to share what they have learned with other staff members. This can be done at a staff meeting. Simply ask the employee who attended a seminar or a course to share the information with the rest of the staff by briefly reviewing the course or describing what he learned and how it applies to the practice.

3. Empower your staff

Office management is complicated. Few ObGyns have a thorough understanding of all business aspects of a medical practice. Most successful ObGyns have learned to delegate the responsibility of running the office and to empower their employees to take control and assume responsibility for their decisions and actions.

In my practice, I empower any employee to make financial decisions up to a limit of $200 without consulting me. For instance, if the office needs a new telephone answering machine, I expect my employees to consider which features we need, check the machines that are available, and compare prices at the local electronics outlet, office supply store, and online retailers to find the best machine at the lowest price.

The take-home message: More than ever before, ObGyns should do what we are best trained to do—diagnose and treat diseases. Very few ObGyns are experts on fax machines. Don’t waste time on activities that your staff members can do.

4. Promote a positive mental attitude

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.” This is also true of the practice of medicine. When the doctor has a positive mental attitude, employees are motivated by the example. When a doctor is easily irritable and carries problems from home to the office and takes her frustration out on the staff, the employees will, in turn, take it out on the patients.

I have an attitude that employees are on stage. The moment they walk in the door in the morning, they have to leave all other problems and concerns behind them. They need to believe that they are responsible for making sure that each patient has a positive experience with the office at every contact point. That includes the telephone, the receptionist who welcomes patients to the practice, the nurse taking the patient into the exam room, the billing clerk who handles the patient’s bill, and, yes, the doctor, too! We all contribute to the patient’s experience, and we all need to have a positive attitude.

5. Recognize achievement

Nothing is more motivating for an employee than for the doctor to recognize his achievements and accomplishments. When an employee improves in job performance, tell him directly. You will satisfy that employee’s need for self-esteem, improve his confidence, and help him fulfill the need for self-esteem from fellow employees.

6. Show your staff that you care

Your employees need to know that you care about them not just as workers but as individuals with their own personal lives. When one of my employees is sick, or one of her family members is ill, I call her at home to check on her and make sure that she has access to adequate medical care. If someone gets sick in the office, I call another medical office and get the employee seen immediately.

7. Catch your employees doing things right

My philosophy is to praise in public, pan in private. When I catch an employee doing something right, I send a thank-you note to her home address, making sure that it arrives on a Saturday. I hope the employee will show my note to family and friends. I use a specially created card or a “thanks a million” check (a non-negotiable replication of a check that is made out to the employee and says, “Thanks a million,” with my name signed at the bottom).

You will be amazed at how appreciative the employee is that you not only recognized her superior service but took the time to put your recognition in writing.

8. Reward your staff for saving money

If a staff member comes up with an idea that saves the practice money, give her a bonus. For example, in my practice, the 15-year-old autoclave broke down. When I tried to get parts, I was informed that the machine is no longer made. The nurse in our office took the autoclave to the hospital’s biomedical engineering department, where workers installed a $30 part that saved me from buying a new $2,000 machine. The nurse deserved to be rewarded for that, so I gave her a $50 check on the spot.

I try to motivate my staff not just to earn more money for the practice but to reduce expenses, so I pay them when they identify and design money-saving ideas.

9. Involve your employees in decision making

Ask your employees for advice. Then make sure you follow it. Your staff members are on the front line; they want the office routine to go well. Include them in the decision-making process, whether the task is writing a mission statement or policy manual, determining a change in procedures, implementing an electronic health record, or meeting new job candidates. By including them, you make them feel like part of the team.

10. Have fun!

Surprise is the spice of life. Whenever you can provide an unexpected perk for your staff, you can be sure the gesture will be appreciated. For example, during a week in which two of my employees were unable to work (due to vacation and illness), the rest of us had to take up the slack. Despite being short-handed, we were able to function at regular speed and capacity without affecting the quality of care. I was so impressed by the extra effort that I arranged for a massage therapist to visit our practice at the end of the week and give everyone a 15- to 20-minute massage. It was my way of saying, “Thank you.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Encourage team spirit. It makes good business sense. When your employees have a personal investment in problem-solving and decision-making, they will go the extra mile for your patients and your practice.

This is the last article in this four-part series on promoting your practice and increasing productivity. I hope you have identified the four pillars of success for your practice—and that I have helped you understand the importance of all four pillars. They represent the strength and stability of a successful ObGyn practice.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

The success of any medical practice and any marketing program begins and ends with the staff. You can gain new patients, forge excellent relationships with referring physicians, and maintain a plentiful number of existing patients—but if you don’t have a staff that is excited, enthusiastic, and knowledgeable when answering the telephone and managing patients, your marketing plan will be ineffective, and you will be disappointed in your practice.

In this article, I review the importance of motivating employees by providing measurable, written goals in the form of a succinct, effective mission statement and policy manual. I also offer practical strategies to inspire your employees by sharing the power, vision, and rewards.

Start with your mission statement

Nearly every successful practice and every successful business has a well-defined vision, mission, goal, or objective. The mission statement should spell out the purpose of the practice and the methods of achieving it. It serves as the road map, providing direction to all members of the staff, doctors included.

The mission statement for my practice is:

We are committed to:

- excellence

- providing the best urologic health care for our patients

- persistent and consistent attention to the little details because they make a big difference.

Develop a policy manual

Every practice should have a manual that contains its rules and regulations. Ideally, this manual should also serve as a guide for any new or temporary employee who comes to work in the office.

The manual should cover job descriptions, the dress code, hours of operation, the division of office responsibilities, vacation and sick days, and emergency telephone numbers.

In my practice, we summarize our policy manual with this expectation:

Dr. Baum’s policy manual statement:

Rule #1— The patient is always right.

Rule #2— If you think the patient is wrong, reread rule #1.

ALL OTHER POLICIES ARE NULL AND VOID.

We post the mission statement in prominent places throughout the office (the reception area and most of the examination rooms, our Web site, and on a large banner in the employee lounge) to remind us and our patients of our dedication to excellent customer service.

Whenever a mistake or problem occurs, the first question we ask each other is, “Did we adhere to the mission statement and the policy statement?” Usually, we discover that we did not. We use the mission statement and the policy statement to refocus us on our number one priority: our patients.

10 LOW-COST WAYS TO MOTIVATE STAFF

A well-motivated staff creates an effective team environment. Most enlightened businesses have discovered that team management leads to increased output and productivity. Your employees want to be valued as human beings and individuals, not just as workers. The more you include them in the process of running the office, the more invested they become in helping to improve the way it works.

1. Review staff performance regularly

Employees like to know where they stand and how they can improve performance on the job. Motivated staff members appreciate feedback on their progress—or, even, their lack of it. The best way to furnish this important feedback is by conducting periodic performance reviews.

I suggest that you meet with your employees on a scheduled basis every 3 to 4 months. Give each employee a worksheet before the scheduled review (see Worksheet below), and then go over her responses during the review. You can learn a lot about what motivates her during this process.

I always end each performance review on a positive note, by telling the employee how great an asset she is to the practice. I document these meetings in the employee’s file.

2. Encourage continuing education

Just as physicians need continuing medical education to stay up to date, your staff members require continuing motivational experiences. Encourage your staff to participate in continuing education courses and support their efforts financially—you’ll get a favorable return on your investment.

I suggest that you offer to pay the fees for any seminars and classes your employees take. You may want to suggest courses in computers, social media, marketing, or any other subject area that will help the practice grow and prosper.

To make these educational experiences even more effective, ask employees to share what they have learned with other staff members. This can be done at a staff meeting. Simply ask the employee who attended a seminar or a course to share the information with the rest of the staff by briefly reviewing the course or describing what he learned and how it applies to the practice.

3. Empower your staff

Office management is complicated. Few ObGyns have a thorough understanding of all business aspects of a medical practice. Most successful ObGyns have learned to delegate the responsibility of running the office and to empower their employees to take control and assume responsibility for their decisions and actions.

In my practice, I empower any employee to make financial decisions up to a limit of $200 without consulting me. For instance, if the office needs a new telephone answering machine, I expect my employees to consider which features we need, check the machines that are available, and compare prices at the local electronics outlet, office supply store, and online retailers to find the best machine at the lowest price.

The take-home message: More than ever before, ObGyns should do what we are best trained to do—diagnose and treat diseases. Very few ObGyns are experts on fax machines. Don’t waste time on activities that your staff members can do.

4. Promote a positive mental attitude

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.” This is also true of the practice of medicine. When the doctor has a positive mental attitude, employees are motivated by the example. When a doctor is easily irritable and carries problems from home to the office and takes her frustration out on the staff, the employees will, in turn, take it out on the patients.

I have an attitude that employees are on stage. The moment they walk in the door in the morning, they have to leave all other problems and concerns behind them. They need to believe that they are responsible for making sure that each patient has a positive experience with the office at every contact point. That includes the telephone, the receptionist who welcomes patients to the practice, the nurse taking the patient into the exam room, the billing clerk who handles the patient’s bill, and, yes, the doctor, too! We all contribute to the patient’s experience, and we all need to have a positive attitude.

5. Recognize achievement

Nothing is more motivating for an employee than for the doctor to recognize his achievements and accomplishments. When an employee improves in job performance, tell him directly. You will satisfy that employee’s need for self-esteem, improve his confidence, and help him fulfill the need for self-esteem from fellow employees.

6. Show your staff that you care

Your employees need to know that you care about them not just as workers but as individuals with their own personal lives. When one of my employees is sick, or one of her family members is ill, I call her at home to check on her and make sure that she has access to adequate medical care. If someone gets sick in the office, I call another medical office and get the employee seen immediately.

7. Catch your employees doing things right

My philosophy is to praise in public, pan in private. When I catch an employee doing something right, I send a thank-you note to her home address, making sure that it arrives on a Saturday. I hope the employee will show my note to family and friends. I use a specially created card or a “thanks a million” check (a non-negotiable replication of a check that is made out to the employee and says, “Thanks a million,” with my name signed at the bottom).

You will be amazed at how appreciative the employee is that you not only recognized her superior service but took the time to put your recognition in writing.

8. Reward your staff for saving money

If a staff member comes up with an idea that saves the practice money, give her a bonus. For example, in my practice, the 15-year-old autoclave broke down. When I tried to get parts, I was informed that the machine is no longer made. The nurse in our office took the autoclave to the hospital’s biomedical engineering department, where workers installed a $30 part that saved me from buying a new $2,000 machine. The nurse deserved to be rewarded for that, so I gave her a $50 check on the spot.

I try to motivate my staff not just to earn more money for the practice but to reduce expenses, so I pay them when they identify and design money-saving ideas.

9. Involve your employees in decision making

Ask your employees for advice. Then make sure you follow it. Your staff members are on the front line; they want the office routine to go well. Include them in the decision-making process, whether the task is writing a mission statement or policy manual, determining a change in procedures, implementing an electronic health record, or meeting new job candidates. By including them, you make them feel like part of the team.

10. Have fun!

Surprise is the spice of life. Whenever you can provide an unexpected perk for your staff, you can be sure the gesture will be appreciated. For example, during a week in which two of my employees were unable to work (due to vacation and illness), the rest of us had to take up the slack. Despite being short-handed, we were able to function at regular speed and capacity without affecting the quality of care. I was so impressed by the extra effort that I arranged for a massage therapist to visit our practice at the end of the week and give everyone a 15- to 20-minute massage. It was my way of saying, “Thank you.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Encourage team spirit. It makes good business sense. When your employees have a personal investment in problem-solving and decision-making, they will go the extra mile for your patients and your practice.

This is the last article in this four-part series on promoting your practice and increasing productivity. I hope you have identified the four pillars of success for your practice—and that I have helped you understand the importance of all four pillars. They represent the strength and stability of a successful ObGyn practice.

Premature baby is severely handicapped: $21M verdict

AT 31 2/7 WEEKS' GESTATION, a woman was admitted to the hospital for hypertension. A maternal-fetal medicine specialist determined that a vaginal delivery was reasonable as long as the mother and fetus remained clinically stable; a cesarean delivery would be required if the status changed. An ObGyn and nurse midwife took over the mother’s care. Before dinoprostone and oxytocin were administered the next morning, a second ObGyn conducted a vaginal exam and found the mother’s cervix to be 4-cm dilated. After noon, the fetal heart rate became nonreassuring, with late and prolonged variable decelerations. The baby was born shortly after 5:00 pm with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck. He was pale, lifeless, and had Apgar scores of 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. He required initial positive pressure ventilation due to bradycardia and poor respiratory effort.

The boy has cerebral palsy; although not cognitively impaired, he is severely physically handicapped. He has had several operations because one leg is shorter than the other. He has 65% function of his arms, making it impossible for him to complete normal, daily tasks by himself.

PARENTS' CLAIM A cesarean delivery should have been performed 3 hours earlier.

DEFENDANT' DEFENSE Fetal heart-rate monitoring was reassuring during the last 40 minutes of labor. An Apgar score of 7 at 5 minutes is normal. Blood gases taken at birth were normal (7.3 pH). Ultrasonography of the baby’s head at age 3 days showed normal findings. Problems were not evident on the head ultrasound until the child was 2 weeks of age, showing that the injury occurred after birth and was due to prematurity. Defendants included both ObGyns, the midwife, and the hospital.

VERDICT A $21 million Maryland verdict was returned, including $1 million in noneconomic damages that was reduced to $650,000 under the state cap.

PHYSICIAN APOLOGIZED: DIDN'T READ BIOPSY REPORT BEFORE SURGERY

A 34-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a family history of breast cancer found a lump in her left breast. After fine-needle aspiration, a general surgeon diagnosed cancer and performed a double mastectomy.

At the first postoperative visit, the surgeon told the patient that she did not have breast cancer, and that the fine-needle aspiration results were negative. The surgeon apologized for never looking at the biopsy report prior to surgery, and admitted that is she had seen the report, she would have cancelled surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The surgeon was negligent in performing bilateral mastectomies without first reading biopsy results.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT Michigan case evaluation delivered an award of $542,000, which both parties accepted.

CYSTOSCOPY BLAMED FOR URETERAL OBSTRUCTION, POOR KIDNEY FUNCTION

WHEN A 59-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent gynecologic surgery that included a cystoscopy, her uterers were functioning normally. During the following month, the ObGyn performed several follow-up examinations. A year later, the patient's right ureter was completely obstructed. The obstruction was repaired, but the patient lost function in her right kidney. She must take a drug to improve kidney function for the rest of her life.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The obstruction was caused by ligation that occurred during cystoscopy. The ObGyn should have diagnosed the obstruction during the weeks following surgery.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE The cystoscopy was properly performed. The patient had not reported any symptoms after the procedure that suggested the presence of an obstruction. The obstruction gradually developed and could not have been diagnosed earlier.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

INFERIOR VENA CAVA DAMAGED DURING ROBOTIC HYSTERECTOMY

A HYSTERECTOMY AND SALPINGO-OOPHORECTOMY were performed on a 64-year-old woman using the da Vinci Surgical System. The gynecologist also removed a cancerous endometrial mass and dissected the periaortic lymph nodes. When the gynecologist used the robot to lift a lymph fat pad, the inferior vena cava was injured and the patient lost 3 L of blood. After converting the laparotomy, a vascular surgeon implanted an artificial graft to repair the inferior vena cava. The patient fully recovered.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The gynecologist did not perform robotic surgery properly, and the patient was not told of all of the risks associated with robotic surgery. Due to the uncertainty regarding the graft's effectiveness, the patient developed posttraumatic stress disorder.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE The vascular injury was a known risk associated with the procedure. The vena cava was not lacerated or transected: perforator veins that joined the lymph fat pad were unintentionally pulled out. The injury was most likely due to the application of pressure, not laceration by the surgical instrument.

VERDICT A $300,000 New York settlement was reached.

READ: The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it? A roundtable discussion with Arnold P. Advincula, MD; Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD; Rosanne M. Kho, MD; Jamal Mourad, DO; Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD; and Jason D. Wright, MD (April 2013)

FETAL DISTRESS CAUSED BRAIN INJURY: $13.9M

DURING THE LAST 2 HOURS OF LABOR, the mother was febrile, the baby's heart rate rose to over 160 bpm, and fetal monitoring indicated fetal distress. Oxytocin was administered to hasten delivery, but the mother's uterus became hyperstimulated. After nearly 17 hours of labor, the child was born without respirations. A video of the vaginal birth shows that the child was blue and unresponsive. The baby was resuscitated, and was subsequently found to have cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and mental retardation. At the time of trial, the 10-year-old had the mental capacity of a 3-year-old.

PARENTS' CLAIM The child suffered brain injury due to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. A cesarean delivery should have been performed as soon as fetal distress was evident. The doctors and nurses misread the baseline heart rate, and did not react when the baby did not recover well from the mother's contractions. Brain imaging did not show damage caused by infection or meningitis.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE The girl's condition was caused by an infection or meningitis.

VERDICT A confidential settlement was reached with the midwife before the trial. The ObGyn was dismissed because he was never alerted to any problem by the labor and delivery team. A $13.9 million Georgia verdict was returned against the hospital system.

UTERINE ARTERY INJURED DURING CESAREAN DELIVERY

AFTER A SCHEDULED CESAREAN delivery, the 29-year-old mother had low blood pressure and an altered state of consciousness When she returned to the OR several hours later, her ObGyn found a uterine artery hematoma and laceration. After the laceration was clamped and sutured, uterine atony was noted and an emergency hysterectomy was performed

PATIENT'S CLAIM The mother was no longer able to bear children. The ObGyn was negligent in lacerating the uterine artery, failing to recognize the laceration during cesarean surgery, failing to properly monitor the patient after surgery, and failing to repair the artery in a timely manner. The patient's low blood pressure and altered state of consciousness should have been an indication that she had severe blood loss. The hospital's nursing staff failed to properly check her vital signs after surgery, and failed to report the abnormalities in blood pressure and consciousness to the ObGyn.