User login

Adverse Events and Rural Discharges

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

Hand Hygiene Makes Headlines

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

By the Numbers: 57

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Resume Red Flags

Fifteen seconds: That’s approximately how long an employer looks at a CV. Recruiters and employers know what they want; they skim even the best resumes. They are on the lookout for applicants who meet their requirements; sometimes they’ll take a chance on a long shot whose pitch catches their eye.

So what happens when a resume stands out for the wrong reasons? Work histories aren’t always perfect, and recruiters and prospective employers will notice any blemishes.

“The thing about red flags is they’re just an indicator that the applicant is an outlier,” says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West Region for EmCare, a Dallas-based company that provides outsourced physician services to more than 500 hospitals in 40 states. “It doesn’t necessarily rule them out.”

Preempt Suspicion

For hospitalists, resume imperfections that attract attention include:

- Gaps in employment;

- Frequent changes in employment;

- Changes in residency;

- Medical board sanctions or probation;

- Failures on the board exam; and

- Forced resignations or firings.

—Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director, Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

When recruiters or employers notice a red flag, they look for other problems to see if patterns emerge and to discern if the applicant exhibited bad judgment, has character flaws, or shows an inability to learn from a mistake, says Jeff Kaplan, PhD, MBA, MCC, a licensed psychologist and Philadelphia-based executive coach whose clients include healthcare industry executives. If such signs exist, the applicant is generally eliminated from consideration. Therefore, it’s critical that applicants explain clearly and succinctly the reason for any resume shortcoming.

“A good way is to actually write a cover letter to explain some uniqueness in their CV that they want [recruiters] to understand,” says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, SFHM, professor and chairman of the Department of Medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine.

By explaining the situation, Dr. Bell says, the hospitalist doesn’t give the employer a chance to guess a reason for the red flag—and potentially guess wrong.

“There’s a big difference between there’s been some sort of serious censure and they’ve been driven out, versus they thought another setting might be more interesting or they just wanted to make a geographic move,” says Thomas E. Thorsheim, PhD, a licensed psychologist and physician leadership coach based in Greenville, S.C. “It’s important to preempt any concerns about how reliable or stable they’re going to be.”

Applicants with resume red flags should show that they’ve taken responsibility for what happened and grown from the experience, say Dr. Thorsheim and Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director in the department of internal medicine and pediatrics at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

“Everyone wants to know that you have learned from your mistakes. Try to have a demonstrated remediation of the concern and go above and beyond the minimum requirements,” Dr. O’Malley says. “For example, if the red flag is academic concerns or not passing your board exams, then bring in documentation of your schedule for reading daily and all of the CME and MKSAP you complete. If it is interpersonal issues, then give examples of recent successes that show how you have improved.”

Brand Recognition

Physicians with a resume blemish should concentrate on highlighting their strengths and “branding” themselves as a workplace contributor, says Bernadette Norz, MBA, ACC, a certified physician development coach. While this advice applies to all applicants, it is particularly critical for those with resume problems, as it will demonstrate they have skills that set them apart from others.

“What people are really looking for is what did you do and what was the result,” Norz says. “Things that one accomplished as a volunteer or on a committee count, too, because that’s where people gain a lot of leadership skills.”

Resumes should not be recitations of job descriptions, she advises. They should be lists of achievements described with action verbs that give the applicant a clear identity and brand. “When you read a resume, you should walk away from it knowing who this person is,” says Dr. Kaplan. “If you don’t see that on their resume, then you’ve got to question it.”

The best applicants network. The more you can develop a relationship and rapport with peers and potential employers, the more likely you will be given a greater chance to sell your strengths and explain weaknesses, says career strategist Ellen Dunagan, president of Traverse Management Solutions in Arlington, Va. “You really want to step it up and be much more active with your own pitch,” she says.

Attitude Matters

But before a hospitalist or any applicant with a resume shortcoming begins to look for a job, they must resolve the issue internally, Dr. Kaplan notes. Taking responsibility will allow you to speak clearly and comfortably about what happened, without negativity or blame.

“If you don’t, you will fumble,” he says. “The prospective employer will start seeing those red flags and they will ask you about it, and you thought you had your pitch ready. Then they ask you two more questions, and before you know it, they’re not going to feel a sense of transparency with you.”

More and more, what employers are looking for is positivity, Dunagan says. It’s a trait applicants won’t have if they still harbor negative feelings toward a previous employer. “It’s just very important to be not only a team player, but to have a really good attitude,” she says. “So present yourself in the best possible light.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Fifteen seconds: That’s approximately how long an employer looks at a CV. Recruiters and employers know what they want; they skim even the best resumes. They are on the lookout for applicants who meet their requirements; sometimes they’ll take a chance on a long shot whose pitch catches their eye.

So what happens when a resume stands out for the wrong reasons? Work histories aren’t always perfect, and recruiters and prospective employers will notice any blemishes.

“The thing about red flags is they’re just an indicator that the applicant is an outlier,” says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West Region for EmCare, a Dallas-based company that provides outsourced physician services to more than 500 hospitals in 40 states. “It doesn’t necessarily rule them out.”

Preempt Suspicion

For hospitalists, resume imperfections that attract attention include:

- Gaps in employment;

- Frequent changes in employment;

- Changes in residency;

- Medical board sanctions or probation;

- Failures on the board exam; and

- Forced resignations or firings.

—Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director, Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

When recruiters or employers notice a red flag, they look for other problems to see if patterns emerge and to discern if the applicant exhibited bad judgment, has character flaws, or shows an inability to learn from a mistake, says Jeff Kaplan, PhD, MBA, MCC, a licensed psychologist and Philadelphia-based executive coach whose clients include healthcare industry executives. If such signs exist, the applicant is generally eliminated from consideration. Therefore, it’s critical that applicants explain clearly and succinctly the reason for any resume shortcoming.

“A good way is to actually write a cover letter to explain some uniqueness in their CV that they want [recruiters] to understand,” says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, SFHM, professor and chairman of the Department of Medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine.

By explaining the situation, Dr. Bell says, the hospitalist doesn’t give the employer a chance to guess a reason for the red flag—and potentially guess wrong.

“There’s a big difference between there’s been some sort of serious censure and they’ve been driven out, versus they thought another setting might be more interesting or they just wanted to make a geographic move,” says Thomas E. Thorsheim, PhD, a licensed psychologist and physician leadership coach based in Greenville, S.C. “It’s important to preempt any concerns about how reliable or stable they’re going to be.”

Applicants with resume red flags should show that they’ve taken responsibility for what happened and grown from the experience, say Dr. Thorsheim and Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director in the department of internal medicine and pediatrics at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

“Everyone wants to know that you have learned from your mistakes. Try to have a demonstrated remediation of the concern and go above and beyond the minimum requirements,” Dr. O’Malley says. “For example, if the red flag is academic concerns or not passing your board exams, then bring in documentation of your schedule for reading daily and all of the CME and MKSAP you complete. If it is interpersonal issues, then give examples of recent successes that show how you have improved.”

Brand Recognition

Physicians with a resume blemish should concentrate on highlighting their strengths and “branding” themselves as a workplace contributor, says Bernadette Norz, MBA, ACC, a certified physician development coach. While this advice applies to all applicants, it is particularly critical for those with resume problems, as it will demonstrate they have skills that set them apart from others.

“What people are really looking for is what did you do and what was the result,” Norz says. “Things that one accomplished as a volunteer or on a committee count, too, because that’s where people gain a lot of leadership skills.”

Resumes should not be recitations of job descriptions, she advises. They should be lists of achievements described with action verbs that give the applicant a clear identity and brand. “When you read a resume, you should walk away from it knowing who this person is,” says Dr. Kaplan. “If you don’t see that on their resume, then you’ve got to question it.”

The best applicants network. The more you can develop a relationship and rapport with peers and potential employers, the more likely you will be given a greater chance to sell your strengths and explain weaknesses, says career strategist Ellen Dunagan, president of Traverse Management Solutions in Arlington, Va. “You really want to step it up and be much more active with your own pitch,” she says.

Attitude Matters

But before a hospitalist or any applicant with a resume shortcoming begins to look for a job, they must resolve the issue internally, Dr. Kaplan notes. Taking responsibility will allow you to speak clearly and comfortably about what happened, without negativity or blame.

“If you don’t, you will fumble,” he says. “The prospective employer will start seeing those red flags and they will ask you about it, and you thought you had your pitch ready. Then they ask you two more questions, and before you know it, they’re not going to feel a sense of transparency with you.”

More and more, what employers are looking for is positivity, Dunagan says. It’s a trait applicants won’t have if they still harbor negative feelings toward a previous employer. “It’s just very important to be not only a team player, but to have a really good attitude,” she says. “So present yourself in the best possible light.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Fifteen seconds: That’s approximately how long an employer looks at a CV. Recruiters and employers know what they want; they skim even the best resumes. They are on the lookout for applicants who meet their requirements; sometimes they’ll take a chance on a long shot whose pitch catches their eye.

So what happens when a resume stands out for the wrong reasons? Work histories aren’t always perfect, and recruiters and prospective employers will notice any blemishes.

“The thing about red flags is they’re just an indicator that the applicant is an outlier,” says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West Region for EmCare, a Dallas-based company that provides outsourced physician services to more than 500 hospitals in 40 states. “It doesn’t necessarily rule them out.”

Preempt Suspicion

For hospitalists, resume imperfections that attract attention include:

- Gaps in employment;

- Frequent changes in employment;

- Changes in residency;

- Medical board sanctions or probation;

- Failures on the board exam; and

- Forced resignations or firings.

—Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director, Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

When recruiters or employers notice a red flag, they look for other problems to see if patterns emerge and to discern if the applicant exhibited bad judgment, has character flaws, or shows an inability to learn from a mistake, says Jeff Kaplan, PhD, MBA, MCC, a licensed psychologist and Philadelphia-based executive coach whose clients include healthcare industry executives. If such signs exist, the applicant is generally eliminated from consideration. Therefore, it’s critical that applicants explain clearly and succinctly the reason for any resume shortcoming.

“A good way is to actually write a cover letter to explain some uniqueness in their CV that they want [recruiters] to understand,” says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, SFHM, professor and chairman of the Department of Medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine.

By explaining the situation, Dr. Bell says, the hospitalist doesn’t give the employer a chance to guess a reason for the red flag—and potentially guess wrong.

“There’s a big difference between there’s been some sort of serious censure and they’ve been driven out, versus they thought another setting might be more interesting or they just wanted to make a geographic move,” says Thomas E. Thorsheim, PhD, a licensed psychologist and physician leadership coach based in Greenville, S.C. “It’s important to preempt any concerns about how reliable or stable they’re going to be.”

Applicants with resume red flags should show that they’ve taken responsibility for what happened and grown from the experience, say Dr. Thorsheim and Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director in the department of internal medicine and pediatrics at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

“Everyone wants to know that you have learned from your mistakes. Try to have a demonstrated remediation of the concern and go above and beyond the minimum requirements,” Dr. O’Malley says. “For example, if the red flag is academic concerns or not passing your board exams, then bring in documentation of your schedule for reading daily and all of the CME and MKSAP you complete. If it is interpersonal issues, then give examples of recent successes that show how you have improved.”

Brand Recognition

Physicians with a resume blemish should concentrate on highlighting their strengths and “branding” themselves as a workplace contributor, says Bernadette Norz, MBA, ACC, a certified physician development coach. While this advice applies to all applicants, it is particularly critical for those with resume problems, as it will demonstrate they have skills that set them apart from others.

“What people are really looking for is what did you do and what was the result,” Norz says. “Things that one accomplished as a volunteer or on a committee count, too, because that’s where people gain a lot of leadership skills.”

Resumes should not be recitations of job descriptions, she advises. They should be lists of achievements described with action verbs that give the applicant a clear identity and brand. “When you read a resume, you should walk away from it knowing who this person is,” says Dr. Kaplan. “If you don’t see that on their resume, then you’ve got to question it.”

The best applicants network. The more you can develop a relationship and rapport with peers and potential employers, the more likely you will be given a greater chance to sell your strengths and explain weaknesses, says career strategist Ellen Dunagan, president of Traverse Management Solutions in Arlington, Va. “You really want to step it up and be much more active with your own pitch,” she says.

Attitude Matters

But before a hospitalist or any applicant with a resume shortcoming begins to look for a job, they must resolve the issue internally, Dr. Kaplan notes. Taking responsibility will allow you to speak clearly and comfortably about what happened, without negativity or blame.

“If you don’t, you will fumble,” he says. “The prospective employer will start seeing those red flags and they will ask you about it, and you thought you had your pitch ready. Then they ask you two more questions, and before you know it, they’re not going to feel a sense of transparency with you.”

More and more, what employers are looking for is positivity, Dunagan says. It’s a trait applicants won’t have if they still harbor negative feelings toward a previous employer. “It’s just very important to be not only a team player, but to have a really good attitude,” she says. “So present yourself in the best possible light.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Medical Decision-Making Factors Include Quantity of Information, Complexity

Physicians should formulate a complete and accurate description of a patient’s condition with an equivalent plan of care for each encounter. While acuity and severity can be inferred by healthcare professionals without excessive detail or repetitive documentation of previously entered information, adequate documentation for every service date assists in conveying patient complexity during medical record review.

Regardless of how complex a patient’s condition might be, physicians tend to undervalue their services. This is due, in part, to the routine nature of patient care for seasoned physicians; it is also due in part to a general lack of understanding with respect to the documentation guidelines.

Consider the following scenario: A 68-year-old male with diabetes and a history of chronic obstructive bronchitis was hospitalized after a five-day history of progressive cough with increasing purulent sputum, shortness of breath, and fever. He was treated for an exacerbation of chronic bronchitis within the past six weeks. Upon admission, the patient had an increased temperature (102°F), increased heart rate (96 beats per minute), and increased respiratory rate (28 shallow breaths per minute). His breath sounds included in the right lower lobe rhonchi, and his pulse oximetry was 89% on room air. Chest X-ray confirmed right lower lobe infiltrates along with chronic changes.

Although some physicians would consider this “low complexity” due to the frequency in which they encounter this type of case, others will more appropriately identify this as moderately complex.

MDM Categories

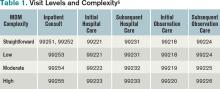

Medical decision-making (MDM) remains consistent in both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, based on the content of physician documentation. Each visit level is associated with a particular level of complexity. Only the care plan for a given date of service is considered when assigning MDM complexity. For each encounter, the physician receives credit for the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality (see Table 1).

Number of diagnoses or treatment options. Physicians should document problems addressed and managed daily despite any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem with an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue treatment.” Credit also depends upon the quantity of problems addressed, as well as the problem type. An established problem in which the care plan has been established by the physician or group practice member during the current hospitalization is less complex than a new problem for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or plan has not been determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A worsening problem is more complex than an improving problem. Physician documentation should:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”), be sure that the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list).

The plan of care outlines problems that the physician personally manages and those that impact management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist might primarily manage diabetes, while the pulmonologist manages pneumonia. Since the pneumonia may impact the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist can receive credit for the pneumonia diagnosis if there is a non-overlapping, hospitalist-related care plan or comment about the pneumonia.

Amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed. “Data” is classified as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Pertinent orders or results could be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”);

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary;

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed”; and

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Risks of complication and/or morbidity or mortality. Risk involves the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. It is measured as minimal, low, moderate, or high when compared with corresponding items assigned to each risk level (see Table 2). The highest individual item detected on the table determines the overall patient risk for that encounter.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures pose more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are not as menacing as progressing problems; minor exacerbations are less hazardous than severe exacerbations; and medication risk varies with the type and potential for adverse effects. A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Status all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), when applicable;

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving comorbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding medication (e.g. “Continue Coumadin, monitor PT/INR”).

Determining complexity of medical decision-making. The final complexity of MDM depends upon the second-highest MDM category. The physician does not have to meet the requirements for all three MDM categories. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for a “multiple” number of diagnoses/treatment options, “limited” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3). Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Beware of payor variation, as it could have a significant impact on visit-level selection.3 Become acquainted with rules applicable to the geographical area. Review insurer websites for guidelines, policies, and “frequently asked questions” that can help improve documentation skills and support billing practices.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians, 2009; 87-118.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

Physicians should formulate a complete and accurate description of a patient’s condition with an equivalent plan of care for each encounter. While acuity and severity can be inferred by healthcare professionals without excessive detail or repetitive documentation of previously entered information, adequate documentation for every service date assists in conveying patient complexity during medical record review.

Regardless of how complex a patient’s condition might be, physicians tend to undervalue their services. This is due, in part, to the routine nature of patient care for seasoned physicians; it is also due in part to a general lack of understanding with respect to the documentation guidelines.

Consider the following scenario: A 68-year-old male with diabetes and a history of chronic obstructive bronchitis was hospitalized after a five-day history of progressive cough with increasing purulent sputum, shortness of breath, and fever. He was treated for an exacerbation of chronic bronchitis within the past six weeks. Upon admission, the patient had an increased temperature (102°F), increased heart rate (96 beats per minute), and increased respiratory rate (28 shallow breaths per minute). His breath sounds included in the right lower lobe rhonchi, and his pulse oximetry was 89% on room air. Chest X-ray confirmed right lower lobe infiltrates along with chronic changes.

Although some physicians would consider this “low complexity” due to the frequency in which they encounter this type of case, others will more appropriately identify this as moderately complex.

MDM Categories

Medical decision-making (MDM) remains consistent in both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, based on the content of physician documentation. Each visit level is associated with a particular level of complexity. Only the care plan for a given date of service is considered when assigning MDM complexity. For each encounter, the physician receives credit for the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality (see Table 1).

Number of diagnoses or treatment options. Physicians should document problems addressed and managed daily despite any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem with an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue treatment.” Credit also depends upon the quantity of problems addressed, as well as the problem type. An established problem in which the care plan has been established by the physician or group practice member during the current hospitalization is less complex than a new problem for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or plan has not been determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A worsening problem is more complex than an improving problem. Physician documentation should:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”), be sure that the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list).

The plan of care outlines problems that the physician personally manages and those that impact management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist might primarily manage diabetes, while the pulmonologist manages pneumonia. Since the pneumonia may impact the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist can receive credit for the pneumonia diagnosis if there is a non-overlapping, hospitalist-related care plan or comment about the pneumonia.

Amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed. “Data” is classified as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Pertinent orders or results could be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”);

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary;

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed”; and

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Risks of complication and/or morbidity or mortality. Risk involves the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. It is measured as minimal, low, moderate, or high when compared with corresponding items assigned to each risk level (see Table 2). The highest individual item detected on the table determines the overall patient risk for that encounter.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures pose more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are not as menacing as progressing problems; minor exacerbations are less hazardous than severe exacerbations; and medication risk varies with the type and potential for adverse effects. A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Status all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), when applicable;

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving comorbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding medication (e.g. “Continue Coumadin, monitor PT/INR”).

Determining complexity of medical decision-making. The final complexity of MDM depends upon the second-highest MDM category. The physician does not have to meet the requirements for all three MDM categories. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for a “multiple” number of diagnoses/treatment options, “limited” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3). Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Beware of payor variation, as it could have a significant impact on visit-level selection.3 Become acquainted with rules applicable to the geographical area. Review insurer websites for guidelines, policies, and “frequently asked questions” that can help improve documentation skills and support billing practices.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians, 2009; 87-118.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

Physicians should formulate a complete and accurate description of a patient’s condition with an equivalent plan of care for each encounter. While acuity and severity can be inferred by healthcare professionals without excessive detail or repetitive documentation of previously entered information, adequate documentation for every service date assists in conveying patient complexity during medical record review.

Regardless of how complex a patient’s condition might be, physicians tend to undervalue their services. This is due, in part, to the routine nature of patient care for seasoned physicians; it is also due in part to a general lack of understanding with respect to the documentation guidelines.

Consider the following scenario: A 68-year-old male with diabetes and a history of chronic obstructive bronchitis was hospitalized after a five-day history of progressive cough with increasing purulent sputum, shortness of breath, and fever. He was treated for an exacerbation of chronic bronchitis within the past six weeks. Upon admission, the patient had an increased temperature (102°F), increased heart rate (96 beats per minute), and increased respiratory rate (28 shallow breaths per minute). His breath sounds included in the right lower lobe rhonchi, and his pulse oximetry was 89% on room air. Chest X-ray confirmed right lower lobe infiltrates along with chronic changes.

Although some physicians would consider this “low complexity” due to the frequency in which they encounter this type of case, others will more appropriately identify this as moderately complex.

MDM Categories

Medical decision-making (MDM) remains consistent in both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, based on the content of physician documentation. Each visit level is associated with a particular level of complexity. Only the care plan for a given date of service is considered when assigning MDM complexity. For each encounter, the physician receives credit for the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality (see Table 1).

Number of diagnoses or treatment options. Physicians should document problems addressed and managed daily despite any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem with an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue treatment.” Credit also depends upon the quantity of problems addressed, as well as the problem type. An established problem in which the care plan has been established by the physician or group practice member during the current hospitalization is less complex than a new problem for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or plan has not been determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A worsening problem is more complex than an improving problem. Physician documentation should:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”), be sure that the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list).

The plan of care outlines problems that the physician personally manages and those that impact management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist might primarily manage diabetes, while the pulmonologist manages pneumonia. Since the pneumonia may impact the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist can receive credit for the pneumonia diagnosis if there is a non-overlapping, hospitalist-related care plan or comment about the pneumonia.

Amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed. “Data” is classified as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Pertinent orders or results could be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”);

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary;

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed”; and

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Risks of complication and/or morbidity or mortality. Risk involves the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. It is measured as minimal, low, moderate, or high when compared with corresponding items assigned to each risk level (see Table 2). The highest individual item detected on the table determines the overall patient risk for that encounter.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures pose more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are not as menacing as progressing problems; minor exacerbations are less hazardous than severe exacerbations; and medication risk varies with the type and potential for adverse effects. A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Status all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), when applicable;

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving comorbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding medication (e.g. “Continue Coumadin, monitor PT/INR”).

Determining complexity of medical decision-making. The final complexity of MDM depends upon the second-highest MDM category. The physician does not have to meet the requirements for all three MDM categories. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for a “multiple” number of diagnoses/treatment options, “limited” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3). Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Beware of payor variation, as it could have a significant impact on visit-level selection.3 Become acquainted with rules applicable to the geographical area. Review insurer websites for guidelines, policies, and “frequently asked questions” that can help improve documentation skills and support billing practices.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/1995dg.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation & Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2011.

- Pohlig, C. Documentation and Coding Evaluation and Management Services. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2010. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians, 2009; 87-118.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:1-20.

IPAB is Medicare's New Hammer for Spending Accountability

Now that the latest annual “doc fix” is in, physicians have been granted another reprieve from potentially crippling cuts to their Medicare reimbursement under the flawed sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula.

Beginning this year, there’s a new player in town that will have the authority to achieve what Congress has consistently failed to do—cut Medicare provider spending to keep it below a cap—and it can do so with unprecedented autonomy.

Say hello to the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), a creature of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that will propose ways to reduce “overpayment” to Medicare providers if target-spending levels are exceeded.

What distinguishes the IPAB from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) is that its proposals will automatically become law, unless Congress enacts its own proposals that reduce Medicare provider spending by at least as much as IPAB’s, or the Senate musters a three-fifths majority vote to override IPAB’s proposals entirely. Further, the IPAB’s changes to Medicare cannot be overruled by the executive branch or a court of law.

MedPAC never wielded such authority; in fact, many of its cost-control recommendations were ignored.

—Judith Feder, PhD, professor of public policy, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., former dean, Georgetown Public Policy Institute, fellow, the Urban Institute

The IPAB comes to life this year, with a $15 million appropriation from the ACA, and begins ramping up its operations (see “The IPAB Timetable,” p. 26). The board will be comprised of a 15-member, multi-stakeholder group—expected to include physicians, nurses, medical experts, economists, consumer advocates, and others—appointed by the President and subject to Senate confirmation.

Incendiary Reactions

Dubbed by its most vociferous and largely Republican critics as “dangerously powerful,” “the real death panel,” and “bureaucrats deciding whether you get care,” the IPAB even has some Democrats decrying its power grab. Rep. Pete Stark (D-Calif.) called the IPAB “an unprecedented abrogation of Congressional authority to an unelected, unaccountable body of so-called experts.”1

Even Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.), who helped draft the ACA, has come out against the IPAB, joining a handful of Democrats and more than 200 Republicans in signing on to a bill (H.R. 452) to repeal the ACA’s IPAB provision. The Senate has a similar bill (S. 668).

Although the IPAB legally is barred from formally making recommendations to ration care, increase beneficiary premiums or cost sharing, and from restricting benefits or eligibility criteria, critics worry that its authority to control prices could hurt patients by driving Medicare payments so low that physicians cease to offer certain services to them.

Enforcement Power

IPAB will have unprecedented power to enforce Medicare’s provider spending benchmarks. Beginning in 2014, if Medicare’s projected spending growth rate per beneficiary rises above an inflation threshold of Gross Domestic Product per capita plus 1%, the IPAB would be triggered and would propose ways to trim provider payments. President Obama has since proposed a lower threshold of GDP per capita plus 0.5%, meaning that the IPAB would be triggered earlier and likely would have deeper cuts to make.

It is unclear how the spending growth benchmark will be affected by the $123 billion in Medicare payment cuts to hospitals and other providers over nine years, which were triggered when the so-called “super committee” failed to reach a budget-cutting consensus last fall.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius describes the IPAB as a “backstop to ensure that rising costs don’t accelerate out of control, threatening Medicare’s stability,” and she maintains that the board is a necessary fallback mechanism to enforce Medicare spending within budget while healthcare providers continue to prove the effectiveness of various value-based delivery and reimbursement reform projects the ACA is funding.2

Impact on Physicians

“The IPAB is a structural intervention to put pressure on Congress, the Executive, and CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] to guarantee the ACA’s investment in cost-containment, and it gives physicians the incentive to act on its principles,” says Judith Feder, PhD, professor of public policy at Georgetown University, former dean of the Georgetown Public Policy Institute, and a fellow at the Urban Institute.

Dr. Feder was a co-signer of a letter sent by 100 health policy experts and economists—including Congressional Budget Office founding director Alice Rivlin, now with the Brookings Institute—to congressional leaders last May urging them to abandon attempts to repeal the IPAB provision. Dr. Feder maintains that the IPAB will marshal “the expertise of professionals who can weigh evidence on how payment incentives affect care delivery and suggest sensible improvements, while forcing debate on difficult choices that Congress has thus far failed to address.”

Because of the changes the ACA has already made to provider reimbursement and Medicare Advantage plan funding, Feder says that Medicare’s average annual growth rate for the next decade is projected to be a full percentage point below per capita growth in GDP. On top of that, she says, “the ACA’s other payment reform experiments have the potential to improve quality and cut spending growth even further by reducing payment for overpriced or undesirable care–like unnecessary hospital readmissions–and rewarding efficiently provided, coordinated care.” By Feder’s analysis, the IPAB would not likely be triggered for a decade, but stands ready as a backup, if needed. Indeed, she favors extending IPAB’s authority beyond Medicare, to allow a system-wide spending target that creates an all-payer incentive to assure that providers really change their behavior to boost quality and efficiency.

Impact on Hospitalists

If the IPAB does come into play, Feder believes that hospitalists have less to worry about than other physician specialists, because the Board’s cost-reduction proposals would likely focus on services where overpayment is the most acute – like imaging and high-cost specialty procedures. “If hospitalists are promoting efficient, coordinated care, their position can only be enhanced by IPAB’s recommendations, to the extent that they can demonstrate value for the healthcare dollar spent,” she says.

Necessary quality and cost reforms that patients deserve, and physicians want to deliver, have been stymied for too long by a crippled Congress, and by powerful special interest agendas, says SHM Public Policy Committee member Bradley Flansbaum DO, MPH, FACP, SFHM, director of the HM program at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, and clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine. Reform requires some real enforcement authority to put value-based quality above the fray, he adds.

“CMS just does not have the teeth to do that right now; they are in the cross-hairs, and an IPAB-like body is needed to insulate Congress from the politically-risky choices, bring evidence and expertise to the decisions, bust through the politics, and get the job done,” Dr. Flansbaum says.

Dr. Flansbaum illustrates the problem by pointing to recent clinical studies that show percutaneous vertebroplasty, which injects bone cement into the spine to treat fractures, to be no better than a placebo in relieving pain. Medicare and private health insurers have been covering vertebroplasty for many years, despite the absence of rigorous study of its effectiveness. The same likely holds true for scores of other expensive treatments and surgical procedures. “Who, exactly, is going to put the kibosh on this?” Dr. Flansbaum asks. “The free market, which includes surgeons, hospitals, and device companies, each with their agendas, or regulators?”

Dr. Flansbaum believes that, in order to effectively bring down costs, the IPAB should not be restricted to supply-side proposals (i.e. provider reimbursement), but also should be allowed to propose demand-side changes to Medicare’s benefit plans, such as tiered network pricing with higher premiums to cover the latest and most expensive technologies.

SHM supports the need for an independent entity to check the growth in Medicare spending, but it does not support the IPAB as it is currently established under the ACA because certain groups (including hospitals) are protected from its scrutiny during its first several years—a limitation that SHM says puts the board’s legitimacy into question and seriously weakens its potential cost-saving effectiveness. SHM supports replacing the IPAB with an independent board that (1) subjects all Medicare providers and suppliers to the same scrutiny without special interest carve-outs, (2) balances cost-saving with QI considerations, (3) protects delivery of quality services, and (4) ensures board membership that represents all potentially affected groups, including physicians. (Read the entire statement in the “Where We Stand” section of SHM’s Advocacy microsite at www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy.)

By removing the IPAB’s present handcuffs—opening its scope to all providers, as well as to demand-side changes in Medicare’s benefit structure—an IPAB-like entity with the proper staff and expertise can rationally think-out the choices that Congress will never make, according to Dr. Flansbaum.

“For the sake of our economy and our future generations, healthcare costs have to come down, even if that means some short-term pain,” he says. “Hospitals may take a hit. Some physician income might take a hit. Otherwise, there won’t be any hospitals or salaries to be hit.”

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

- Statement of Congressman Pete Stark Supporting Health Care Reform, March 21, 2010. Available at: http://www.stark.house.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1534:statement-of-congressman-pete-stark-supporting-health-care-reform&catid=67:floor-statements-2010-. Accessed Jan. 5, 2012.

- Kathleen Sebelius, “IPAB Will Protect Medicare.” Politico, June 23, 2011. Available at: http://dyn.politico.com/printstory.cfm?uuid=FDE594BA-87EE-4DA5-9841-33804926EF36. Accessed Jan. 5, 2012.

Now that the latest annual “doc fix” is in, physicians have been granted another reprieve from potentially crippling cuts to their Medicare reimbursement under the flawed sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula.

Beginning this year, there’s a new player in town that will have the authority to achieve what Congress has consistently failed to do—cut Medicare provider spending to keep it below a cap—and it can do so with unprecedented autonomy.

Say hello to the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), a creature of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that will propose ways to reduce “overpayment” to Medicare providers if target-spending levels are exceeded.

What distinguishes the IPAB from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) is that its proposals will automatically become law, unless Congress enacts its own proposals that reduce Medicare provider spending by at least as much as IPAB’s, or the Senate musters a three-fifths majority vote to override IPAB’s proposals entirely. Further, the IPAB’s changes to Medicare cannot be overruled by the executive branch or a court of law.

MedPAC never wielded such authority; in fact, many of its cost-control recommendations were ignored.

—Judith Feder, PhD, professor of public policy, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., former dean, Georgetown Public Policy Institute, fellow, the Urban Institute

The IPAB comes to life this year, with a $15 million appropriation from the ACA, and begins ramping up its operations (see “The IPAB Timetable,” p. 26). The board will be comprised of a 15-member, multi-stakeholder group—expected to include physicians, nurses, medical experts, economists, consumer advocates, and others—appointed by the President and subject to Senate confirmation.

Incendiary Reactions

Dubbed by its most vociferous and largely Republican critics as “dangerously powerful,” “the real death panel,” and “bureaucrats deciding whether you get care,” the IPAB even has some Democrats decrying its power grab. Rep. Pete Stark (D-Calif.) called the IPAB “an unprecedented abrogation of Congressional authority to an unelected, unaccountable body of so-called experts.”1

Even Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.), who helped draft the ACA, has come out against the IPAB, joining a handful of Democrats and more than 200 Republicans in signing on to a bill (H.R. 452) to repeal the ACA’s IPAB provision. The Senate has a similar bill (S. 668).

Although the IPAB legally is barred from formally making recommendations to ration care, increase beneficiary premiums or cost sharing, and from restricting benefits or eligibility criteria, critics worry that its authority to control prices could hurt patients by driving Medicare payments so low that physicians cease to offer certain services to them.

Enforcement Power

IPAB will have unprecedented power to enforce Medicare’s provider spending benchmarks. Beginning in 2014, if Medicare’s projected spending growth rate per beneficiary rises above an inflation threshold of Gross Domestic Product per capita plus 1%, the IPAB would be triggered and would propose ways to trim provider payments. President Obama has since proposed a lower threshold of GDP per capita plus 0.5%, meaning that the IPAB would be triggered earlier and likely would have deeper cuts to make.

It is unclear how the spending growth benchmark will be affected by the $123 billion in Medicare payment cuts to hospitals and other providers over nine years, which were triggered when the so-called “super committee” failed to reach a budget-cutting consensus last fall.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius describes the IPAB as a “backstop to ensure that rising costs don’t accelerate out of control, threatening Medicare’s stability,” and she maintains that the board is a necessary fallback mechanism to enforce Medicare spending within budget while healthcare providers continue to prove the effectiveness of various value-based delivery and reimbursement reform projects the ACA is funding.2

Impact on Physicians

“The IPAB is a structural intervention to put pressure on Congress, the Executive, and CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] to guarantee the ACA’s investment in cost-containment, and it gives physicians the incentive to act on its principles,” says Judith Feder, PhD, professor of public policy at Georgetown University, former dean of the Georgetown Public Policy Institute, and a fellow at the Urban Institute.

Dr. Feder was a co-signer of a letter sent by 100 health policy experts and economists—including Congressional Budget Office founding director Alice Rivlin, now with the Brookings Institute—to congressional leaders last May urging them to abandon attempts to repeal the IPAB provision. Dr. Feder maintains that the IPAB will marshal “the expertise of professionals who can weigh evidence on how payment incentives affect care delivery and suggest sensible improvements, while forcing debate on difficult choices that Congress has thus far failed to address.”

Because of the changes the ACA has already made to provider reimbursement and Medicare Advantage plan funding, Feder says that Medicare’s average annual growth rate for the next decade is projected to be a full percentage point below per capita growth in GDP. On top of that, she says, “the ACA’s other payment reform experiments have the potential to improve quality and cut spending growth even further by reducing payment for overpriced or undesirable care–like unnecessary hospital readmissions–and rewarding efficiently provided, coordinated care.” By Feder’s analysis, the IPAB would not likely be triggered for a decade, but stands ready as a backup, if needed. Indeed, she favors extending IPAB’s authority beyond Medicare, to allow a system-wide spending target that creates an all-payer incentive to assure that providers really change their behavior to boost quality and efficiency.

Impact on Hospitalists

If the IPAB does come into play, Feder believes that hospitalists have less to worry about than other physician specialists, because the Board’s cost-reduction proposals would likely focus on services where overpayment is the most acute – like imaging and high-cost specialty procedures. “If hospitalists are promoting efficient, coordinated care, their position can only be enhanced by IPAB’s recommendations, to the extent that they can demonstrate value for the healthcare dollar spent,” she says.

Necessary quality and cost reforms that patients deserve, and physicians want to deliver, have been stymied for too long by a crippled Congress, and by powerful special interest agendas, says SHM Public Policy Committee member Bradley Flansbaum DO, MPH, FACP, SFHM, director of the HM program at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, and clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine. Reform requires some real enforcement authority to put value-based quality above the fray, he adds.

“CMS just does not have the teeth to do that right now; they are in the cross-hairs, and an IPAB-like body is needed to insulate Congress from the politically-risky choices, bring evidence and expertise to the decisions, bust through the politics, and get the job done,” Dr. Flansbaum says.

Dr. Flansbaum illustrates the problem by pointing to recent clinical studies that show percutaneous vertebroplasty, which injects bone cement into the spine to treat fractures, to be no better than a placebo in relieving pain. Medicare and private health insurers have been covering vertebroplasty for many years, despite the absence of rigorous study of its effectiveness. The same likely holds true for scores of other expensive treatments and surgical procedures. “Who, exactly, is going to put the kibosh on this?” Dr. Flansbaum asks. “The free market, which includes surgeons, hospitals, and device companies, each with their agendas, or regulators?”

Dr. Flansbaum believes that, in order to effectively bring down costs, the IPAB should not be restricted to supply-side proposals (i.e. provider reimbursement), but also should be allowed to propose demand-side changes to Medicare’s benefit plans, such as tiered network pricing with higher premiums to cover the latest and most expensive technologies.

SHM supports the need for an independent entity to check the growth in Medicare spending, but it does not support the IPAB as it is currently established under the ACA because certain groups (including hospitals) are protected from its scrutiny during its first several years—a limitation that SHM says puts the board’s legitimacy into question and seriously weakens its potential cost-saving effectiveness. SHM supports replacing the IPAB with an independent board that (1) subjects all Medicare providers and suppliers to the same scrutiny without special interest carve-outs, (2) balances cost-saving with QI considerations, (3) protects delivery of quality services, and (4) ensures board membership that represents all potentially affected groups, including physicians. (Read the entire statement in the “Where We Stand” section of SHM’s Advocacy microsite at www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy.)

By removing the IPAB’s present handcuffs—opening its scope to all providers, as well as to demand-side changes in Medicare’s benefit structure—an IPAB-like entity with the proper staff and expertise can rationally think-out the choices that Congress will never make, according to Dr. Flansbaum.

“For the sake of our economy and our future generations, healthcare costs have to come down, even if that means some short-term pain,” he says. “Hospitals may take a hit. Some physician income might take a hit. Otherwise, there won’t be any hospitals or salaries to be hit.”

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

- Statement of Congressman Pete Stark Supporting Health Care Reform, March 21, 2010. Available at: http://www.stark.house.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1534:statement-of-congressman-pete-stark-supporting-health-care-reform&catid=67:floor-statements-2010-. Accessed Jan. 5, 2012.

- Kathleen Sebelius, “IPAB Will Protect Medicare.” Politico, June 23, 2011. Available at: http://dyn.politico.com/printstory.cfm?uuid=FDE594BA-87EE-4DA5-9841-33804926EF36. Accessed Jan. 5, 2012.

Now that the latest annual “doc fix” is in, physicians have been granted another reprieve from potentially crippling cuts to their Medicare reimbursement under the flawed sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula.

Beginning this year, there’s a new player in town that will have the authority to achieve what Congress has consistently failed to do—cut Medicare provider spending to keep it below a cap—and it can do so with unprecedented autonomy.

Say hello to the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), a creature of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that will propose ways to reduce “overpayment” to Medicare providers if target-spending levels are exceeded.

What distinguishes the IPAB from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) is that its proposals will automatically become law, unless Congress enacts its own proposals that reduce Medicare provider spending by at least as much as IPAB’s, or the Senate musters a three-fifths majority vote to override IPAB’s proposals entirely. Further, the IPAB’s changes to Medicare cannot be overruled by the executive branch or a court of law.

MedPAC never wielded such authority; in fact, many of its cost-control recommendations were ignored.

—Judith Feder, PhD, professor of public policy, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., former dean, Georgetown Public Policy Institute, fellow, the Urban Institute

The IPAB comes to life this year, with a $15 million appropriation from the ACA, and begins ramping up its operations (see “The IPAB Timetable,” p. 26). The board will be comprised of a 15-member, multi-stakeholder group—expected to include physicians, nurses, medical experts, economists, consumer advocates, and others—appointed by the President and subject to Senate confirmation.

Incendiary Reactions