User login

No more 'stickies'!: Help your patients bring their ‘to-do’ list into the 21st century

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Where to find guidance on using pharmacogenomics in psychiatric practice

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

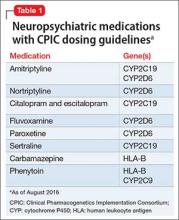

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

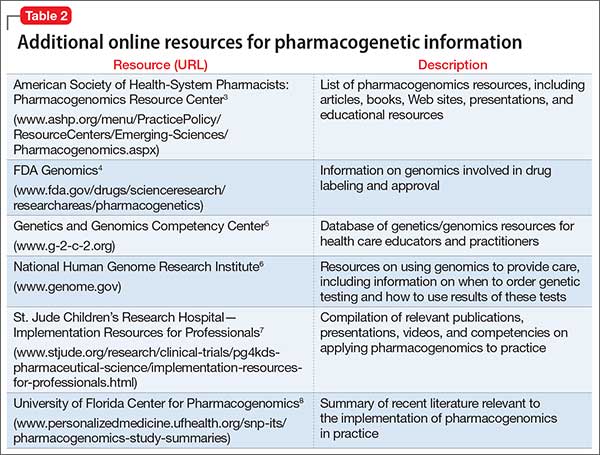

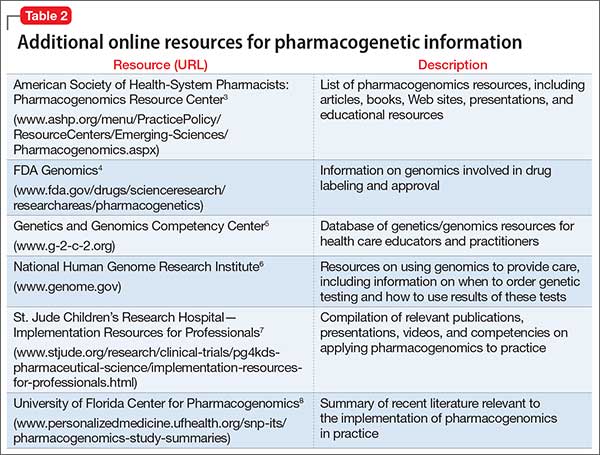

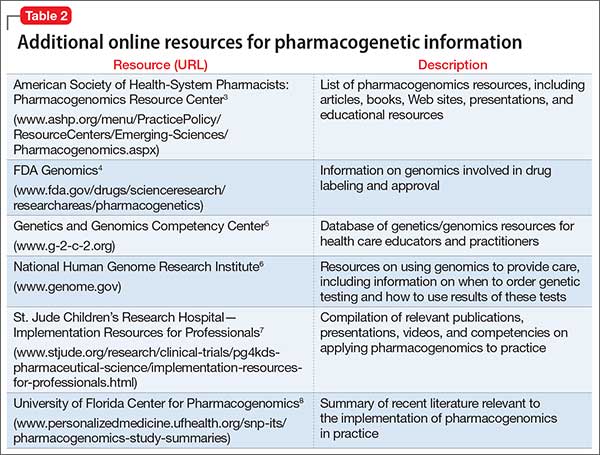

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

The future of ketamine in psychiatry

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

When the diagnosis is hard to swallow, take these management steps

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

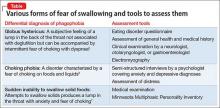

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

Disordered sleep: Ask the right questions to reveal this hidden confounder

It seems like common sense: Sleeping poorly results in not feeling good. The truth is that many of our patients are sleep deprived but are either unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge, their problem. The busy life that many patients have does not allow adequate time for sleep. In fact, I have encountered patients who think of sleep as an inconvenience that takes away time from other pursuits.

Sleep deprivation in psychiatric disorders

Sleep deprivation occurs when the duration or quality of sleep is inadequate. Inadequate sleep duration can be caused by insomnia or simply not allowing enough time for sleep (1 aspect of poor sleep hygiene). Poor sleep quality often is caused by sleep-disordered breathing.

Sleep deprivation can result in either sleepiness or fatigue. Sleepiness is a propensity to fall asleep; fatigue is a lack of energy that is not alleviated by additional sleep. Fatigue is more likely to be associated with a psychiatric disorder; sleepiness is more predominant in sleep disorders (although there is significant overlap). For example, patients with a major depressive disorder can experience fatigue as much as patients with sleep deprivation, but the latter also is more likely to result in sleepiness. Trouble concentrating is seen in anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep deprivation.1

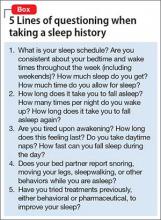

Insomnia or poor sleep hygiene can be diagnosed with a thorough sleep history. I take special care to consider sleep problems by presenting 5 groups of questions to the patient (Box).

Sleep-disordered breathing

A sleep study is required to accurately diagnose sleep-disordered breathing. Unless this diagnosis is specifically looked for, it remains hidden from both physicians and patients. Clues to the presence of sleep-disordered breathing include snorting, snoring, and gasping for air during sleep; witnessed apnea during sleep; nighttime awakening; daytime fatigue; nocturia; mouth breathing or dry mouth; acid reflux; irritability; morning headache; nighttime sweating; and low libido. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing include obesity; smoking; menopause; family history; increasing age; and anatomical factors (eg, deviation of the nasal septum; retrognathia; long face syndrome; high-arched narrow hard palate; large tonsils, uvula, or tongue).2

Measuring sleep quality

Some patients are unaware of the extent to which they are sleepy. The most widely used scale to measure sleepiness is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.3 Sleep specialists view a score of ≥10 on the Epworth scale as indicative of daytime sleepiness. In addition, a patient’s daily consumption of caffeinated beverages can be a clue to excessive sleepiness or, at least, fatigue. If the degree of sleepiness cannot be determined subjectively, objective measures, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), can quantify it. In a randomly selected sample from the general population, 13.4% had excessive daytime sleepiness as measured by the MSLT.4

Adult ADHD and sleep deprivation

In my practice, sleep problems confound both the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders, especially ADHD. Often, patients who report ADHD symptoms have no clear history of ADHD during childhood. In these cases, I always consider the possibility that their ADHD symptoms are due to sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation can mimic the poor executive function and difficulty concentrating that is often seen in ADHD, because such deprivation is associated with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during wakefulness.5

In patients who provide a clear history of ADHD symptoms during childhood, it is possible that inadequate sleep exacerbates ADHD symptoms as adults. Unless sleep deprivation is diagnosed and treated in these patients, they can end up taking a higher-than-necessary dosage of a stimulant. Also, patients who have ADHD might have a difficult time managing their sleep schedule because of poor executive functioning. This, in turn, can result in additional sleep deprivation, thus worsening their ADHD symptoms, creating a vicious circle.

Psychotropics and sedation

Many psychiatric medications list sedation as a side effect. Patients with untreated sleep problems might be more likely to notice this side effect because sleep problems contribute to their fatigue. I have had patients who were unable to tolerate sedative medications until their sleep apnea was treated.

In conclusion

It is important to consider sleep deprivation in your differential diagnosis of psychiatric patients. This will allow for more accurate diagnosis and treatment and, in some cases, can avoid treatment resistance.

1. Stahl SM. Excessive sleepiness. San Diego, CA: NEI Press; 2005.

2. Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):736-747.

3. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

4. Drake CL, Roehrs TA, Richardson GS, et al. Epidemiology and morbidity of excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 2002;25:A91-A92.

5. Thomas M, Sing H, Belenky G, et al. Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness. I. Effects of 24 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):335-352.

It seems like common sense: Sleeping poorly results in not feeling good. The truth is that many of our patients are sleep deprived but are either unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge, their problem. The busy life that many patients have does not allow adequate time for sleep. In fact, I have encountered patients who think of sleep as an inconvenience that takes away time from other pursuits.

Sleep deprivation in psychiatric disorders

Sleep deprivation occurs when the duration or quality of sleep is inadequate. Inadequate sleep duration can be caused by insomnia or simply not allowing enough time for sleep (1 aspect of poor sleep hygiene). Poor sleep quality often is caused by sleep-disordered breathing.

Sleep deprivation can result in either sleepiness or fatigue. Sleepiness is a propensity to fall asleep; fatigue is a lack of energy that is not alleviated by additional sleep. Fatigue is more likely to be associated with a psychiatric disorder; sleepiness is more predominant in sleep disorders (although there is significant overlap). For example, patients with a major depressive disorder can experience fatigue as much as patients with sleep deprivation, but the latter also is more likely to result in sleepiness. Trouble concentrating is seen in anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep deprivation.1

Insomnia or poor sleep hygiene can be diagnosed with a thorough sleep history. I take special care to consider sleep problems by presenting 5 groups of questions to the patient (Box).

Sleep-disordered breathing

A sleep study is required to accurately diagnose sleep-disordered breathing. Unless this diagnosis is specifically looked for, it remains hidden from both physicians and patients. Clues to the presence of sleep-disordered breathing include snorting, snoring, and gasping for air during sleep; witnessed apnea during sleep; nighttime awakening; daytime fatigue; nocturia; mouth breathing or dry mouth; acid reflux; irritability; morning headache; nighttime sweating; and low libido. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing include obesity; smoking; menopause; family history; increasing age; and anatomical factors (eg, deviation of the nasal septum; retrognathia; long face syndrome; high-arched narrow hard palate; large tonsils, uvula, or tongue).2

Measuring sleep quality

Some patients are unaware of the extent to which they are sleepy. The most widely used scale to measure sleepiness is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.3 Sleep specialists view a score of ≥10 on the Epworth scale as indicative of daytime sleepiness. In addition, a patient’s daily consumption of caffeinated beverages can be a clue to excessive sleepiness or, at least, fatigue. If the degree of sleepiness cannot be determined subjectively, objective measures, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), can quantify it. In a randomly selected sample from the general population, 13.4% had excessive daytime sleepiness as measured by the MSLT.4

Adult ADHD and sleep deprivation

In my practice, sleep problems confound both the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders, especially ADHD. Often, patients who report ADHD symptoms have no clear history of ADHD during childhood. In these cases, I always consider the possibility that their ADHD symptoms are due to sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation can mimic the poor executive function and difficulty concentrating that is often seen in ADHD, because such deprivation is associated with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during wakefulness.5

In patients who provide a clear history of ADHD symptoms during childhood, it is possible that inadequate sleep exacerbates ADHD symptoms as adults. Unless sleep deprivation is diagnosed and treated in these patients, they can end up taking a higher-than-necessary dosage of a stimulant. Also, patients who have ADHD might have a difficult time managing their sleep schedule because of poor executive functioning. This, in turn, can result in additional sleep deprivation, thus worsening their ADHD symptoms, creating a vicious circle.

Psychotropics and sedation

Many psychiatric medications list sedation as a side effect. Patients with untreated sleep problems might be more likely to notice this side effect because sleep problems contribute to their fatigue. I have had patients who were unable to tolerate sedative medications until their sleep apnea was treated.

In conclusion

It is important to consider sleep deprivation in your differential diagnosis of psychiatric patients. This will allow for more accurate diagnosis and treatment and, in some cases, can avoid treatment resistance.

It seems like common sense: Sleeping poorly results in not feeling good. The truth is that many of our patients are sleep deprived but are either unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge, their problem. The busy life that many patients have does not allow adequate time for sleep. In fact, I have encountered patients who think of sleep as an inconvenience that takes away time from other pursuits.

Sleep deprivation in psychiatric disorders

Sleep deprivation occurs when the duration or quality of sleep is inadequate. Inadequate sleep duration can be caused by insomnia or simply not allowing enough time for sleep (1 aspect of poor sleep hygiene). Poor sleep quality often is caused by sleep-disordered breathing.

Sleep deprivation can result in either sleepiness or fatigue. Sleepiness is a propensity to fall asleep; fatigue is a lack of energy that is not alleviated by additional sleep. Fatigue is more likely to be associated with a psychiatric disorder; sleepiness is more predominant in sleep disorders (although there is significant overlap). For example, patients with a major depressive disorder can experience fatigue as much as patients with sleep deprivation, but the latter also is more likely to result in sleepiness. Trouble concentrating is seen in anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep deprivation.1

Insomnia or poor sleep hygiene can be diagnosed with a thorough sleep history. I take special care to consider sleep problems by presenting 5 groups of questions to the patient (Box).

Sleep-disordered breathing

A sleep study is required to accurately diagnose sleep-disordered breathing. Unless this diagnosis is specifically looked for, it remains hidden from both physicians and patients. Clues to the presence of sleep-disordered breathing include snorting, snoring, and gasping for air during sleep; witnessed apnea during sleep; nighttime awakening; daytime fatigue; nocturia; mouth breathing or dry mouth; acid reflux; irritability; morning headache; nighttime sweating; and low libido. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing include obesity; smoking; menopause; family history; increasing age; and anatomical factors (eg, deviation of the nasal septum; retrognathia; long face syndrome; high-arched narrow hard palate; large tonsils, uvula, or tongue).2

Measuring sleep quality

Some patients are unaware of the extent to which they are sleepy. The most widely used scale to measure sleepiness is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.3 Sleep specialists view a score of ≥10 on the Epworth scale as indicative of daytime sleepiness. In addition, a patient’s daily consumption of caffeinated beverages can be a clue to excessive sleepiness or, at least, fatigue. If the degree of sleepiness cannot be determined subjectively, objective measures, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), can quantify it. In a randomly selected sample from the general population, 13.4% had excessive daytime sleepiness as measured by the MSLT.4

Adult ADHD and sleep deprivation

In my practice, sleep problems confound both the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders, especially ADHD. Often, patients who report ADHD symptoms have no clear history of ADHD during childhood. In these cases, I always consider the possibility that their ADHD symptoms are due to sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation can mimic the poor executive function and difficulty concentrating that is often seen in ADHD, because such deprivation is associated with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during wakefulness.5

In patients who provide a clear history of ADHD symptoms during childhood, it is possible that inadequate sleep exacerbates ADHD symptoms as adults. Unless sleep deprivation is diagnosed and treated in these patients, they can end up taking a higher-than-necessary dosage of a stimulant. Also, patients who have ADHD might have a difficult time managing their sleep schedule because of poor executive functioning. This, in turn, can result in additional sleep deprivation, thus worsening their ADHD symptoms, creating a vicious circle.

Psychotropics and sedation

Many psychiatric medications list sedation as a side effect. Patients with untreated sleep problems might be more likely to notice this side effect because sleep problems contribute to their fatigue. I have had patients who were unable to tolerate sedative medications until their sleep apnea was treated.

In conclusion

It is important to consider sleep deprivation in your differential diagnosis of psychiatric patients. This will allow for more accurate diagnosis and treatment and, in some cases, can avoid treatment resistance.

1. Stahl SM. Excessive sleepiness. San Diego, CA: NEI Press; 2005.

2. Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):736-747.

3. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

4. Drake CL, Roehrs TA, Richardson GS, et al. Epidemiology and morbidity of excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 2002;25:A91-A92.

5. Thomas M, Sing H, Belenky G, et al. Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness. I. Effects of 24 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):335-352.

1. Stahl SM. Excessive sleepiness. San Diego, CA: NEI Press; 2005.

2. Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):736-747.

3. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

4. Drake CL, Roehrs TA, Richardson GS, et al. Epidemiology and morbidity of excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 2002;25:A91-A92.

5. Thomas M, Sing H, Belenky G, et al. Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness. I. Effects of 24 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):335-352.

How to talk to patients and families about brain stimulation

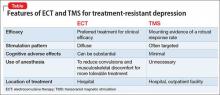

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.