User login

Think beyond prazosin when treating nightmares in PTSD

Nightmares are a common feature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that could lead to fatigue, impaired concentration, and poor work performance. The α-1 antagonist prazosin decreases noradrenergic hyperactivity and reduces nightmares; however, it can cause adverse effects, be contraindicated, or provide no benefit to some patients. Consider these alternative medications to reduce nightmares in PTSD.

Alpha-2 agonists

Clonidine and guanfacine are α-2 agonists, used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and high blood pressure, that decrease noradrenergic activity, and either medication might be preferable to prazosin because they are more likely to cause sedation. A review and a case series showed that many patients—some with comorbid traumatic brain injury—reported fewer nightmares after taking 0.2 to 0.6 mg of clonidine.1,2 Guanfacine might be more beneficial because it has a longer half-life; 2 mg of guanfacine eliminated nightmares in 1 patient.3 However, in a double-blind placebo-controlled study and an extension study, guanfacine did not reduce nightmares or other PTSD symptoms.4,5

Initiate 0.1 mg of clonidine at bedtime, and titrate to efficacy or to 0.6 mg. Similarly, initiate guanfacine at 1 mg, and titrate to efficacy or to 4 mg. Monitor for hypotension, excess sedation, dry mouth, and rebound hypertension.

Cyproheptadine

Used to treat serotonin syndrome, cyproheptadine’s antagonism of serotonin 2A receptors has varying efficacy for reducing nightmares. Some patients have reported a decrease in nightmares at dosages ranging from 4 to 24 mg.1,6 Other studies found no reduction in nightmares or diminished quality of sleep.1,7

Initiate cyproheptadine at 4 mg/d, titrate every 2 or 3 days, and monitor for sedation, confusion, or reduced efficacy of concurrent serotonergic medications. Cyproheptadine might be preferable for its sedating effect and potential to reduce sexual adverse effects from serotonergic medications.

Topiramate

Topiramate is approved for treatment of epilepsy and migraine headache. At 75 to 100 mg/d in a clinical trial, topiramate partially or completely suppressed nightmares.8 Start with 25 mg/d, titrate to efficacy, and monitor for anorexia, paresthesias, and cognitive impairment. Topiramate might be better than prazosin for patients without renal impairment who want sedation, weight loss, or reduced irritability.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved to treat seizures and postherpetic neuralgia and also is used to treat neuropathic pain. When 300 to 3,600 mg/d (mean dosage, 1,300 mg/d) of gabapentin was added to medication regimens, most patients reported decreased frequency or intensity of nightmares.9 Monitor patients for sedation, dizziness, mood changes, and weight gain. Gabapentin might be an option for patients without renal impairment who have comorbid pain, insomnia, or anxiety.

Are these reasonable alternatives?

Despite small sample sizes in published studies and few randomized trials, clonidine, guanfacine, cyproheptadine, topiramate, and gabapentin are reasonable alternatives to prazosin for reducing nightmares in patients with PTSD.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Aurora RN, Zak RS, Auerbach SH, et al; Standards of Practice Committee; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

2. Alao A, Selvarajah J, Razi S. The use of clonidine in the treatment of nightmares among patients with co-morbid PTSD and traumatic brain injury. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(2):165-169.

3. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ. The suppression of nightmares with guanfacine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(8):371.

4. Davis LL, Ward C, Rasmusson A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of guanfacine for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):8-18.

5. Neylan TC, Lenoci M, Samuelson KW, et al. No improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with guanfacine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2186-2188.

6. Harsch HH. Cyproheptadine for recurrent nightmares. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(11):1491-1492.

7. Jacobs-Rebhun S, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep difficulty. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1525-1526.

8. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

9. Hamner MB, Brodrick PS, Labbate LA. Gabapentin in PTSD: a retrospective, clinical series of adjunctive therapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13(3):141-146.

Nightmares are a common feature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that could lead to fatigue, impaired concentration, and poor work performance. The α-1 antagonist prazosin decreases noradrenergic hyperactivity and reduces nightmares; however, it can cause adverse effects, be contraindicated, or provide no benefit to some patients. Consider these alternative medications to reduce nightmares in PTSD.

Alpha-2 agonists

Clonidine and guanfacine are α-2 agonists, used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and high blood pressure, that decrease noradrenergic activity, and either medication might be preferable to prazosin because they are more likely to cause sedation. A review and a case series showed that many patients—some with comorbid traumatic brain injury—reported fewer nightmares after taking 0.2 to 0.6 mg of clonidine.1,2 Guanfacine might be more beneficial because it has a longer half-life; 2 mg of guanfacine eliminated nightmares in 1 patient.3 However, in a double-blind placebo-controlled study and an extension study, guanfacine did not reduce nightmares or other PTSD symptoms.4,5

Initiate 0.1 mg of clonidine at bedtime, and titrate to efficacy or to 0.6 mg. Similarly, initiate guanfacine at 1 mg, and titrate to efficacy or to 4 mg. Monitor for hypotension, excess sedation, dry mouth, and rebound hypertension.

Cyproheptadine

Used to treat serotonin syndrome, cyproheptadine’s antagonism of serotonin 2A receptors has varying efficacy for reducing nightmares. Some patients have reported a decrease in nightmares at dosages ranging from 4 to 24 mg.1,6 Other studies found no reduction in nightmares or diminished quality of sleep.1,7

Initiate cyproheptadine at 4 mg/d, titrate every 2 or 3 days, and monitor for sedation, confusion, or reduced efficacy of concurrent serotonergic medications. Cyproheptadine might be preferable for its sedating effect and potential to reduce sexual adverse effects from serotonergic medications.

Topiramate

Topiramate is approved for treatment of epilepsy and migraine headache. At 75 to 100 mg/d in a clinical trial, topiramate partially or completely suppressed nightmares.8 Start with 25 mg/d, titrate to efficacy, and monitor for anorexia, paresthesias, and cognitive impairment. Topiramate might be better than prazosin for patients without renal impairment who want sedation, weight loss, or reduced irritability.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved to treat seizures and postherpetic neuralgia and also is used to treat neuropathic pain. When 300 to 3,600 mg/d (mean dosage, 1,300 mg/d) of gabapentin was added to medication regimens, most patients reported decreased frequency or intensity of nightmares.9 Monitor patients for sedation, dizziness, mood changes, and weight gain. Gabapentin might be an option for patients without renal impairment who have comorbid pain, insomnia, or anxiety.

Are these reasonable alternatives?

Despite small sample sizes in published studies and few randomized trials, clonidine, guanfacine, cyproheptadine, topiramate, and gabapentin are reasonable alternatives to prazosin for reducing nightmares in patients with PTSD.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Nightmares are a common feature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that could lead to fatigue, impaired concentration, and poor work performance. The α-1 antagonist prazosin decreases noradrenergic hyperactivity and reduces nightmares; however, it can cause adverse effects, be contraindicated, or provide no benefit to some patients. Consider these alternative medications to reduce nightmares in PTSD.

Alpha-2 agonists

Clonidine and guanfacine are α-2 agonists, used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and high blood pressure, that decrease noradrenergic activity, and either medication might be preferable to prazosin because they are more likely to cause sedation. A review and a case series showed that many patients—some with comorbid traumatic brain injury—reported fewer nightmares after taking 0.2 to 0.6 mg of clonidine.1,2 Guanfacine might be more beneficial because it has a longer half-life; 2 mg of guanfacine eliminated nightmares in 1 patient.3 However, in a double-blind placebo-controlled study and an extension study, guanfacine did not reduce nightmares or other PTSD symptoms.4,5

Initiate 0.1 mg of clonidine at bedtime, and titrate to efficacy or to 0.6 mg. Similarly, initiate guanfacine at 1 mg, and titrate to efficacy or to 4 mg. Monitor for hypotension, excess sedation, dry mouth, and rebound hypertension.

Cyproheptadine

Used to treat serotonin syndrome, cyproheptadine’s antagonism of serotonin 2A receptors has varying efficacy for reducing nightmares. Some patients have reported a decrease in nightmares at dosages ranging from 4 to 24 mg.1,6 Other studies found no reduction in nightmares or diminished quality of sleep.1,7

Initiate cyproheptadine at 4 mg/d, titrate every 2 or 3 days, and monitor for sedation, confusion, or reduced efficacy of concurrent serotonergic medications. Cyproheptadine might be preferable for its sedating effect and potential to reduce sexual adverse effects from serotonergic medications.

Topiramate

Topiramate is approved for treatment of epilepsy and migraine headache. At 75 to 100 mg/d in a clinical trial, topiramate partially or completely suppressed nightmares.8 Start with 25 mg/d, titrate to efficacy, and monitor for anorexia, paresthesias, and cognitive impairment. Topiramate might be better than prazosin for patients without renal impairment who want sedation, weight loss, or reduced irritability.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved to treat seizures and postherpetic neuralgia and also is used to treat neuropathic pain. When 300 to 3,600 mg/d (mean dosage, 1,300 mg/d) of gabapentin was added to medication regimens, most patients reported decreased frequency or intensity of nightmares.9 Monitor patients for sedation, dizziness, mood changes, and weight gain. Gabapentin might be an option for patients without renal impairment who have comorbid pain, insomnia, or anxiety.

Are these reasonable alternatives?

Despite small sample sizes in published studies and few randomized trials, clonidine, guanfacine, cyproheptadine, topiramate, and gabapentin are reasonable alternatives to prazosin for reducing nightmares in patients with PTSD.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Aurora RN, Zak RS, Auerbach SH, et al; Standards of Practice Committee; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

2. Alao A, Selvarajah J, Razi S. The use of clonidine in the treatment of nightmares among patients with co-morbid PTSD and traumatic brain injury. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(2):165-169.

3. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ. The suppression of nightmares with guanfacine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(8):371.

4. Davis LL, Ward C, Rasmusson A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of guanfacine for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):8-18.

5. Neylan TC, Lenoci M, Samuelson KW, et al. No improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with guanfacine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2186-2188.

6. Harsch HH. Cyproheptadine for recurrent nightmares. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(11):1491-1492.

7. Jacobs-Rebhun S, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep difficulty. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1525-1526.

8. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

9. Hamner MB, Brodrick PS, Labbate LA. Gabapentin in PTSD: a retrospective, clinical series of adjunctive therapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13(3):141-146.

1. Aurora RN, Zak RS, Auerbach SH, et al; Standards of Practice Committee; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

2. Alao A, Selvarajah J, Razi S. The use of clonidine in the treatment of nightmares among patients with co-morbid PTSD and traumatic brain injury. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(2):165-169.

3. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ. The suppression of nightmares with guanfacine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(8):371.

4. Davis LL, Ward C, Rasmusson A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of guanfacine for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):8-18.

5. Neylan TC, Lenoci M, Samuelson KW, et al. No improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with guanfacine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2186-2188.

6. Harsch HH. Cyproheptadine for recurrent nightmares. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(11):1491-1492.

7. Jacobs-Rebhun S, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep difficulty. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1525-1526.

8. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

9. Hamner MB, Brodrick PS, Labbate LA. Gabapentin in PTSD: a retrospective, clinical series of adjunctive therapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13(3):141-146.

What to do when adolescents with ADHD self-medicate with bath salts

Designer drugs are rapidly making inroads with young people, primarily because of easier access, lower overall cost, and nebulous legality. These drugs are made as variants of illicit drugs or new formulations and sold as “research chemicals” and labeled as “not for human consumption,” which allows them to fall outside existing laws. The ingredients typically are not detected in a urine drug screen.

Notoriously addictive, these designer drugs, such as bath salts, are known to incorporate synthetic cathinones—namely, methylone, mephedrone or methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). The stimulant, amphetamine-like effects of bath salts make the drug attractive to adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Why do teens gravitate toward bath salts?

Adolescents with undiagnosed ADHD might self-medicate with drugs that are suited for addressing restlessness, intrapsychic turmoil, and other symptoms of ADHD. In 2 case studies, using the self-medication hypothesis, people with ADHD were more likely to seek cocaine by means of “self-selection.”1 These drug-seeking behaviors often led to cocaine dependence, even when other substances, such as alcohol or Cannabis, were available.

Methylphenidate and other ADHD pharmacotherapies influence the nucleus accumbens in a manner similar to that of cocaine. These findings suggest that adolescents with ADHD and cocaine dependence might respond to therapeutic interventions that substitute cocaine with psychostimulants.1

Bath salts fall within the same spectrum of psychostimulant agents as methylphenidate and cocaine. MDPV approximates the effect of methylphenidate at low doses, and cocaine at higher doses. It often is marketed under the name “Ivory Wave” and could be confused with cocaine. Self-administration of MDPV can induce psychoactive effects that help alleviate ADHD symptoms; adolescents might continue to experience enhanced concentration and overall performance.2 Also, because of the low cost of “legal” bath salts, they are an appealing alternative to cocaine for self-medication.

Managing the sequelae of bath salt intoxication

Bath salts may produce sympathomimetic effects greater than cocaine, which require a proactive approach to symptom management. A medley of unknown ingredients in bath salt preparations makes it difficult for clinicians to gauge the pharmacological impact on individual patients; therefore, therapeutic interventions are on a case-by-case basis. However, emergencies concerning amphetamines and amphetamine analogues and derivatives often have similar presentations.

Cardiovascular effects. MDPV-specific urine and blood tests conducted on patients admitted to the emergency room showed a 10-fold increase in overall dopamine levels compared with those who took cocaine. As a sympathomimetic, high doses of dopamine are responsible for raising blood pressure and could lead to the development of pronounced cardiovascular effects.3,4

Agitation. Clinicians generally are advised to treat agitation before providing a more comprehensive assessment of symptoms. Endotracheal intubation often is a required for adequate control of agitation. Bath salt-induced agitation often is treated with IV benzodiazepines.4,5 Monitor patients for excessive sedation or new-onset “paradoxical agitation” as a function of ongoing benzo-diazepine therapy. Clinicians also may choose to co-administer an antipsychotic with benzodiazepines, although the practice is not universally encouraged for agitation control.

Mephedrone produces a delirious state in conjunction with psychotic symptoms. Antipsychotic therapy has been suggested for addressing ongoing agitation.6

Tachycardia. Symptomatic treatment of tachycardia involves beta blockers, such as labetalol. Nitroglycerine has evidence of efficacy for chest pain associated with cocaine intoxication; however, it is unclear whether it is effective for similar drugs of abuse.4

Multi-organ collapse caused by MDPV necessitates aggressive intervention, including prompt dialysis. Carefully evaluate the patient for the presence of organ-specific insults and initiate supportive measures accordingly. Pronounced agitation with hyperthermia might portend severely compromised renal, hepatic, and/or cardiac function in MDPV users.7 Those who present with MDPV intoxication and concomitant renal injury seem to benefit from hemodialysis.8 Repeat intoxication events may yield a presentation of acute renal injury replete with metabolic derangements, including metabolic acidosis, hyperuricemia, and rhabdomyolysis.9 Thorough patient assessments and interventions are useful in determining long-term outcomes, including issues pertaining to mortality.

Confronting an epidemic

Adolescents are quickly adopting designer drugs as a readily accessible form of recreational “legal highs.”10 Public awareness and educational initiatives can bring to light the dangers of these substances that exert powerful and, sometimes, unpredictable psychoactive effects on the user.

Self-mutilation and suicidal ideation also have been documented among those who ingested bath salts. These reports appear to be escalating across Europe and the United States. On a national level, U.S. poison centers have reported an almost 20-fold increase in calls regarding bath salts between 2010 and 2011.5 It is of utmost importance for clinicians and emergency personnel to familiarize themselves with the sympathomimetic toxidrome and management for bath salt consumption.

1. Mariani JJ, Khantzian EJ, Levin FR. The self-medication hypothesis and psychostimulant treatment of cocaine dependence: an update. Am J Addict. 2014;23(2):189-193.

2. Deluca P, Schifano F, Davey Z, et al. MDPV Report: Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project. https://catbull.com/alamut/Bibliothek/PsychonautMDPVreport. pdf. Updated June 8, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2015.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. What are bath salts? http://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/bath-salts. Updated October 23, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

4. Richards JR, Derlet RW, Albertson TE, et al. Methamphetamine, “bath salts,” and other amphetamine-related derivatives. Enliven: Toxicology and Allied Clinical Pharmacology. 2014;1(1):1-15.

5. Olives TD, Orozco BS, Stellpflug SJ. Bath salts: the ivory wave of trouble. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):58-62.

6. Kasick DP, McKnight CA, Klisovic E. “Bath salt” ingestion leading to severe intoxication delirium: two cases and a brief review of the emergence of mephedrone use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(2):176-180.

7. Borek HA, Holstege CP. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of “bath salts” containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):103-105.

8. Regunath H, Ariyamuthu VK, Dalal P, et al. Bath salt intoxication causing acute kidney injury requiring hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(suppl 1):S47-S49.

9. Adebamiro A, Perazella MA. Recurrent acute kidney injury following bath salts intoxication. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):273-275.

10. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. New designer drug, ‘bath salts,’ may confer additional risk for adolescents. EurekAlert. http://www.eurekalert.org/ pub_releases/2013-04/foas-ndd041813.php. Published April 23, 2013. Accessed November 10, 2015.

Designer drugs are rapidly making inroads with young people, primarily because of easier access, lower overall cost, and nebulous legality. These drugs are made as variants of illicit drugs or new formulations and sold as “research chemicals” and labeled as “not for human consumption,” which allows them to fall outside existing laws. The ingredients typically are not detected in a urine drug screen.

Notoriously addictive, these designer drugs, such as bath salts, are known to incorporate synthetic cathinones—namely, methylone, mephedrone or methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). The stimulant, amphetamine-like effects of bath salts make the drug attractive to adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Why do teens gravitate toward bath salts?

Adolescents with undiagnosed ADHD might self-medicate with drugs that are suited for addressing restlessness, intrapsychic turmoil, and other symptoms of ADHD. In 2 case studies, using the self-medication hypothesis, people with ADHD were more likely to seek cocaine by means of “self-selection.”1 These drug-seeking behaviors often led to cocaine dependence, even when other substances, such as alcohol or Cannabis, were available.

Methylphenidate and other ADHD pharmacotherapies influence the nucleus accumbens in a manner similar to that of cocaine. These findings suggest that adolescents with ADHD and cocaine dependence might respond to therapeutic interventions that substitute cocaine with psychostimulants.1

Bath salts fall within the same spectrum of psychostimulant agents as methylphenidate and cocaine. MDPV approximates the effect of methylphenidate at low doses, and cocaine at higher doses. It often is marketed under the name “Ivory Wave” and could be confused with cocaine. Self-administration of MDPV can induce psychoactive effects that help alleviate ADHD symptoms; adolescents might continue to experience enhanced concentration and overall performance.2 Also, because of the low cost of “legal” bath salts, they are an appealing alternative to cocaine for self-medication.

Managing the sequelae of bath salt intoxication

Bath salts may produce sympathomimetic effects greater than cocaine, which require a proactive approach to symptom management. A medley of unknown ingredients in bath salt preparations makes it difficult for clinicians to gauge the pharmacological impact on individual patients; therefore, therapeutic interventions are on a case-by-case basis. However, emergencies concerning amphetamines and amphetamine analogues and derivatives often have similar presentations.

Cardiovascular effects. MDPV-specific urine and blood tests conducted on patients admitted to the emergency room showed a 10-fold increase in overall dopamine levels compared with those who took cocaine. As a sympathomimetic, high doses of dopamine are responsible for raising blood pressure and could lead to the development of pronounced cardiovascular effects.3,4

Agitation. Clinicians generally are advised to treat agitation before providing a more comprehensive assessment of symptoms. Endotracheal intubation often is a required for adequate control of agitation. Bath salt-induced agitation often is treated with IV benzodiazepines.4,5 Monitor patients for excessive sedation or new-onset “paradoxical agitation” as a function of ongoing benzo-diazepine therapy. Clinicians also may choose to co-administer an antipsychotic with benzodiazepines, although the practice is not universally encouraged for agitation control.

Mephedrone produces a delirious state in conjunction with psychotic symptoms. Antipsychotic therapy has been suggested for addressing ongoing agitation.6

Tachycardia. Symptomatic treatment of tachycardia involves beta blockers, such as labetalol. Nitroglycerine has evidence of efficacy for chest pain associated with cocaine intoxication; however, it is unclear whether it is effective for similar drugs of abuse.4

Multi-organ collapse caused by MDPV necessitates aggressive intervention, including prompt dialysis. Carefully evaluate the patient for the presence of organ-specific insults and initiate supportive measures accordingly. Pronounced agitation with hyperthermia might portend severely compromised renal, hepatic, and/or cardiac function in MDPV users.7 Those who present with MDPV intoxication and concomitant renal injury seem to benefit from hemodialysis.8 Repeat intoxication events may yield a presentation of acute renal injury replete with metabolic derangements, including metabolic acidosis, hyperuricemia, and rhabdomyolysis.9 Thorough patient assessments and interventions are useful in determining long-term outcomes, including issues pertaining to mortality.

Confronting an epidemic

Adolescents are quickly adopting designer drugs as a readily accessible form of recreational “legal highs.”10 Public awareness and educational initiatives can bring to light the dangers of these substances that exert powerful and, sometimes, unpredictable psychoactive effects on the user.

Self-mutilation and suicidal ideation also have been documented among those who ingested bath salts. These reports appear to be escalating across Europe and the United States. On a national level, U.S. poison centers have reported an almost 20-fold increase in calls regarding bath salts between 2010 and 2011.5 It is of utmost importance for clinicians and emergency personnel to familiarize themselves with the sympathomimetic toxidrome and management for bath salt consumption.

Designer drugs are rapidly making inroads with young people, primarily because of easier access, lower overall cost, and nebulous legality. These drugs are made as variants of illicit drugs or new formulations and sold as “research chemicals” and labeled as “not for human consumption,” which allows them to fall outside existing laws. The ingredients typically are not detected in a urine drug screen.

Notoriously addictive, these designer drugs, such as bath salts, are known to incorporate synthetic cathinones—namely, methylone, mephedrone or methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). The stimulant, amphetamine-like effects of bath salts make the drug attractive to adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Why do teens gravitate toward bath salts?

Adolescents with undiagnosed ADHD might self-medicate with drugs that are suited for addressing restlessness, intrapsychic turmoil, and other symptoms of ADHD. In 2 case studies, using the self-medication hypothesis, people with ADHD were more likely to seek cocaine by means of “self-selection.”1 These drug-seeking behaviors often led to cocaine dependence, even when other substances, such as alcohol or Cannabis, were available.

Methylphenidate and other ADHD pharmacotherapies influence the nucleus accumbens in a manner similar to that of cocaine. These findings suggest that adolescents with ADHD and cocaine dependence might respond to therapeutic interventions that substitute cocaine with psychostimulants.1

Bath salts fall within the same spectrum of psychostimulant agents as methylphenidate and cocaine. MDPV approximates the effect of methylphenidate at low doses, and cocaine at higher doses. It often is marketed under the name “Ivory Wave” and could be confused with cocaine. Self-administration of MDPV can induce psychoactive effects that help alleviate ADHD symptoms; adolescents might continue to experience enhanced concentration and overall performance.2 Also, because of the low cost of “legal” bath salts, they are an appealing alternative to cocaine for self-medication.

Managing the sequelae of bath salt intoxication

Bath salts may produce sympathomimetic effects greater than cocaine, which require a proactive approach to symptom management. A medley of unknown ingredients in bath salt preparations makes it difficult for clinicians to gauge the pharmacological impact on individual patients; therefore, therapeutic interventions are on a case-by-case basis. However, emergencies concerning amphetamines and amphetamine analogues and derivatives often have similar presentations.

Cardiovascular effects. MDPV-specific urine and blood tests conducted on patients admitted to the emergency room showed a 10-fold increase in overall dopamine levels compared with those who took cocaine. As a sympathomimetic, high doses of dopamine are responsible for raising blood pressure and could lead to the development of pronounced cardiovascular effects.3,4

Agitation. Clinicians generally are advised to treat agitation before providing a more comprehensive assessment of symptoms. Endotracheal intubation often is a required for adequate control of agitation. Bath salt-induced agitation often is treated with IV benzodiazepines.4,5 Monitor patients for excessive sedation or new-onset “paradoxical agitation” as a function of ongoing benzo-diazepine therapy. Clinicians also may choose to co-administer an antipsychotic with benzodiazepines, although the practice is not universally encouraged for agitation control.

Mephedrone produces a delirious state in conjunction with psychotic symptoms. Antipsychotic therapy has been suggested for addressing ongoing agitation.6

Tachycardia. Symptomatic treatment of tachycardia involves beta blockers, such as labetalol. Nitroglycerine has evidence of efficacy for chest pain associated with cocaine intoxication; however, it is unclear whether it is effective for similar drugs of abuse.4

Multi-organ collapse caused by MDPV necessitates aggressive intervention, including prompt dialysis. Carefully evaluate the patient for the presence of organ-specific insults and initiate supportive measures accordingly. Pronounced agitation with hyperthermia might portend severely compromised renal, hepatic, and/or cardiac function in MDPV users.7 Those who present with MDPV intoxication and concomitant renal injury seem to benefit from hemodialysis.8 Repeat intoxication events may yield a presentation of acute renal injury replete with metabolic derangements, including metabolic acidosis, hyperuricemia, and rhabdomyolysis.9 Thorough patient assessments and interventions are useful in determining long-term outcomes, including issues pertaining to mortality.

Confronting an epidemic

Adolescents are quickly adopting designer drugs as a readily accessible form of recreational “legal highs.”10 Public awareness and educational initiatives can bring to light the dangers of these substances that exert powerful and, sometimes, unpredictable psychoactive effects on the user.

Self-mutilation and suicidal ideation also have been documented among those who ingested bath salts. These reports appear to be escalating across Europe and the United States. On a national level, U.S. poison centers have reported an almost 20-fold increase in calls regarding bath salts between 2010 and 2011.5 It is of utmost importance for clinicians and emergency personnel to familiarize themselves with the sympathomimetic toxidrome and management for bath salt consumption.

1. Mariani JJ, Khantzian EJ, Levin FR. The self-medication hypothesis and psychostimulant treatment of cocaine dependence: an update. Am J Addict. 2014;23(2):189-193.

2. Deluca P, Schifano F, Davey Z, et al. MDPV Report: Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project. https://catbull.com/alamut/Bibliothek/PsychonautMDPVreport. pdf. Updated June 8, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2015.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. What are bath salts? http://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/bath-salts. Updated October 23, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

4. Richards JR, Derlet RW, Albertson TE, et al. Methamphetamine, “bath salts,” and other amphetamine-related derivatives. Enliven: Toxicology and Allied Clinical Pharmacology. 2014;1(1):1-15.

5. Olives TD, Orozco BS, Stellpflug SJ. Bath salts: the ivory wave of trouble. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):58-62.

6. Kasick DP, McKnight CA, Klisovic E. “Bath salt” ingestion leading to severe intoxication delirium: two cases and a brief review of the emergence of mephedrone use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(2):176-180.

7. Borek HA, Holstege CP. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of “bath salts” containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):103-105.

8. Regunath H, Ariyamuthu VK, Dalal P, et al. Bath salt intoxication causing acute kidney injury requiring hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(suppl 1):S47-S49.

9. Adebamiro A, Perazella MA. Recurrent acute kidney injury following bath salts intoxication. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):273-275.

10. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. New designer drug, ‘bath salts,’ may confer additional risk for adolescents. EurekAlert. http://www.eurekalert.org/ pub_releases/2013-04/foas-ndd041813.php. Published April 23, 2013. Accessed November 10, 2015.

1. Mariani JJ, Khantzian EJ, Levin FR. The self-medication hypothesis and psychostimulant treatment of cocaine dependence: an update. Am J Addict. 2014;23(2):189-193.

2. Deluca P, Schifano F, Davey Z, et al. MDPV Report: Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project. https://catbull.com/alamut/Bibliothek/PsychonautMDPVreport. pdf. Updated June 8, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2015.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. What are bath salts? http://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/bath-salts. Updated October 23, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

4. Richards JR, Derlet RW, Albertson TE, et al. Methamphetamine, “bath salts,” and other amphetamine-related derivatives. Enliven: Toxicology and Allied Clinical Pharmacology. 2014;1(1):1-15.

5. Olives TD, Orozco BS, Stellpflug SJ. Bath salts: the ivory wave of trouble. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):58-62.

6. Kasick DP, McKnight CA, Klisovic E. “Bath salt” ingestion leading to severe intoxication delirium: two cases and a brief review of the emergence of mephedrone use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(2):176-180.

7. Borek HA, Holstege CP. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of “bath salts” containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):103-105.

8. Regunath H, Ariyamuthu VK, Dalal P, et al. Bath salt intoxication causing acute kidney injury requiring hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(suppl 1):S47-S49.

9. Adebamiro A, Perazella MA. Recurrent acute kidney injury following bath salts intoxication. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):273-275.

10. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. New designer drug, ‘bath salts,’ may confer additional risk for adolescents. EurekAlert. http://www.eurekalert.org/ pub_releases/2013-04/foas-ndd041813.php. Published April 23, 2013. Accessed November 10, 2015.

To blog or not to blog? That is the marketing question

Few methods can build your practice and reputation as well as blogging— nor can they give you as much grief. Your opinions can become known to a wide audience; you might influence public thinking or behavior; and you might become associated with a particular expertise at almost no financial cost. Yet, having regular deadlines to produce creative content can be stressful, and the time required to do it well has its own cost.

What is it?

“Blog” is the collapsed expression of “Web log.” Blogging is posting your thoughts on a Web site for colleagues or consumers, or both, to read. Typically, a blog is written as if you were writing a newspaper column; word count varies, from 250 to 1,000 words. Alternative formats are auditory (podcasts) or visual (vlog) but those media require greater technical proficiency and take more time to produce.

Whether you decide to write or record your blog entry, be guided by this advice:

• The subject matter can be anything you choose, but will be easiest to write when what you write about is based on your expertise.

• The format can be stream of consciousness,essay, or bulleted lists or slides; the latter is the most common and often follows a how-to or list format (eg, “Top [number] strategies to XYZ” or “[Number] of things you didn’t know about ABC”).

• End the blog with a cliffhanger or a call-to-action statement that invites readers to comment (especially if you then comment on their comments), to help drive interest.

• Generate material at a consistent interval (eg, once a week or twice a month), so your readers can look forward to your soliloquies on a regular basis.

Your professional Web site can serve as a venue for your blog. Using a WordPressa-based site, for example, offers a user-friendly way to compose your dispatch, add formatting (headers, bullets, color, images, etc.) as you see fit, and then publish it. It requires little technical expertise and adds no extra expense to your Web site. Alternatively, you might wish to contact editors at magazines or blog aggregators with story ideas, and let them handle the logistics if your content is appealing to them.

aWordPress is a Web site creation and management tool.

Spreading the word

There is much you can do to publicize your blog.

• Take advantage of social media. Build up your contacts on LinkedIn and follow other bloggers and large news sites on Twitter. Often, recipients will respond in-kind. Then, for each new piece, post or tweet it in these accounts.

• Offer an e-mail subscription so that readers can easily follow you (by means of a free WordPress plug-in, for example).

• Be found in search engines, such as Google, by writing high-quality, original content. Don’t force certain keywords into your article in the hopes that search engines find them—doing so tends to make writing more robotic and can lower your page rank.

Successful strategies

Regularly setting time aside so that the process is enjoyable and not onerously deadline-driven lends satisfaction to the experience and comes through in the quality of the composition. To save time, consider dictating your thoughts to your computer or phone, then outsource transcription.

Don’t overlook the bounty of material in your day-to-day life: stories from sessions; discoveries from your own reading or the latest news; and lectures you give. All of these can serve as inspiration and material for posts. Jot down these moments in a notebook as soon as they come up, or else the memory will likely slip away.

Just as with other forms of social media, be mindful of appropriate boundaries. Do not disclose identifying patient information; even revealing facets of your life might not be appropriate for current or future patients to have access to. On the other hand, it might be therapeutic for them to know select personal information, such as how you have handled past dilemmas, that reveals you are a real person (a “whole object” in psychoanalytic terms), and that models meaningful thoughts or deeds.

You’ll find your voice, in time

Getting started with blogging often is the toughest part. Finding the right format, material, and routine will take time. Eventually, you will find your blogging voice, and will value the unique opportunity to brand your practice and yourself, provide valuable content to your readers, and find an outlet for artistic expression.

Disclosure

Dr. Braslow is the founder of Luminello.com.

Few methods can build your practice and reputation as well as blogging— nor can they give you as much grief. Your opinions can become known to a wide audience; you might influence public thinking or behavior; and you might become associated with a particular expertise at almost no financial cost. Yet, having regular deadlines to produce creative content can be stressful, and the time required to do it well has its own cost.

What is it?

“Blog” is the collapsed expression of “Web log.” Blogging is posting your thoughts on a Web site for colleagues or consumers, or both, to read. Typically, a blog is written as if you were writing a newspaper column; word count varies, from 250 to 1,000 words. Alternative formats are auditory (podcasts) or visual (vlog) but those media require greater technical proficiency and take more time to produce.

Whether you decide to write or record your blog entry, be guided by this advice:

• The subject matter can be anything you choose, but will be easiest to write when what you write about is based on your expertise.

• The format can be stream of consciousness,essay, or bulleted lists or slides; the latter is the most common and often follows a how-to or list format (eg, “Top [number] strategies to XYZ” or “[Number] of things you didn’t know about ABC”).

• End the blog with a cliffhanger or a call-to-action statement that invites readers to comment (especially if you then comment on their comments), to help drive interest.

• Generate material at a consistent interval (eg, once a week or twice a month), so your readers can look forward to your soliloquies on a regular basis.

Your professional Web site can serve as a venue for your blog. Using a WordPressa-based site, for example, offers a user-friendly way to compose your dispatch, add formatting (headers, bullets, color, images, etc.) as you see fit, and then publish it. It requires little technical expertise and adds no extra expense to your Web site. Alternatively, you might wish to contact editors at magazines or blog aggregators with story ideas, and let them handle the logistics if your content is appealing to them.

aWordPress is a Web site creation and management tool.

Spreading the word

There is much you can do to publicize your blog.

• Take advantage of social media. Build up your contacts on LinkedIn and follow other bloggers and large news sites on Twitter. Often, recipients will respond in-kind. Then, for each new piece, post or tweet it in these accounts.

• Offer an e-mail subscription so that readers can easily follow you (by means of a free WordPress plug-in, for example).

• Be found in search engines, such as Google, by writing high-quality, original content. Don’t force certain keywords into your article in the hopes that search engines find them—doing so tends to make writing more robotic and can lower your page rank.

Successful strategies

Regularly setting time aside so that the process is enjoyable and not onerously deadline-driven lends satisfaction to the experience and comes through in the quality of the composition. To save time, consider dictating your thoughts to your computer or phone, then outsource transcription.

Don’t overlook the bounty of material in your day-to-day life: stories from sessions; discoveries from your own reading or the latest news; and lectures you give. All of these can serve as inspiration and material for posts. Jot down these moments in a notebook as soon as they come up, or else the memory will likely slip away.

Just as with other forms of social media, be mindful of appropriate boundaries. Do not disclose identifying patient information; even revealing facets of your life might not be appropriate for current or future patients to have access to. On the other hand, it might be therapeutic for them to know select personal information, such as how you have handled past dilemmas, that reveals you are a real person (a “whole object” in psychoanalytic terms), and that models meaningful thoughts or deeds.

You’ll find your voice, in time

Getting started with blogging often is the toughest part. Finding the right format, material, and routine will take time. Eventually, you will find your blogging voice, and will value the unique opportunity to brand your practice and yourself, provide valuable content to your readers, and find an outlet for artistic expression.

Disclosure

Dr. Braslow is the founder of Luminello.com.

Few methods can build your practice and reputation as well as blogging— nor can they give you as much grief. Your opinions can become known to a wide audience; you might influence public thinking or behavior; and you might become associated with a particular expertise at almost no financial cost. Yet, having regular deadlines to produce creative content can be stressful, and the time required to do it well has its own cost.

What is it?

“Blog” is the collapsed expression of “Web log.” Blogging is posting your thoughts on a Web site for colleagues or consumers, or both, to read. Typically, a blog is written as if you were writing a newspaper column; word count varies, from 250 to 1,000 words. Alternative formats are auditory (podcasts) or visual (vlog) but those media require greater technical proficiency and take more time to produce.

Whether you decide to write or record your blog entry, be guided by this advice:

• The subject matter can be anything you choose, but will be easiest to write when what you write about is based on your expertise.

• The format can be stream of consciousness,essay, or bulleted lists or slides; the latter is the most common and often follows a how-to or list format (eg, “Top [number] strategies to XYZ” or “[Number] of things you didn’t know about ABC”).

• End the blog with a cliffhanger or a call-to-action statement that invites readers to comment (especially if you then comment on their comments), to help drive interest.

• Generate material at a consistent interval (eg, once a week or twice a month), so your readers can look forward to your soliloquies on a regular basis.

Your professional Web site can serve as a venue for your blog. Using a WordPressa-based site, for example, offers a user-friendly way to compose your dispatch, add formatting (headers, bullets, color, images, etc.) as you see fit, and then publish it. It requires little technical expertise and adds no extra expense to your Web site. Alternatively, you might wish to contact editors at magazines or blog aggregators with story ideas, and let them handle the logistics if your content is appealing to them.

aWordPress is a Web site creation and management tool.

Spreading the word

There is much you can do to publicize your blog.

• Take advantage of social media. Build up your contacts on LinkedIn and follow other bloggers and large news sites on Twitter. Often, recipients will respond in-kind. Then, for each new piece, post or tweet it in these accounts.

• Offer an e-mail subscription so that readers can easily follow you (by means of a free WordPress plug-in, for example).

• Be found in search engines, such as Google, by writing high-quality, original content. Don’t force certain keywords into your article in the hopes that search engines find them—doing so tends to make writing more robotic and can lower your page rank.

Successful strategies

Regularly setting time aside so that the process is enjoyable and not onerously deadline-driven lends satisfaction to the experience and comes through in the quality of the composition. To save time, consider dictating your thoughts to your computer or phone, then outsource transcription.

Don’t overlook the bounty of material in your day-to-day life: stories from sessions; discoveries from your own reading or the latest news; and lectures you give. All of these can serve as inspiration and material for posts. Jot down these moments in a notebook as soon as they come up, or else the memory will likely slip away.

Just as with other forms of social media, be mindful of appropriate boundaries. Do not disclose identifying patient information; even revealing facets of your life might not be appropriate for current or future patients to have access to. On the other hand, it might be therapeutic for them to know select personal information, such as how you have handled past dilemmas, that reveals you are a real person (a “whole object” in psychoanalytic terms), and that models meaningful thoughts or deeds.

You’ll find your voice, in time

Getting started with blogging often is the toughest part. Finding the right format, material, and routine will take time. Eventually, you will find your blogging voice, and will value the unique opportunity to brand your practice and yourself, provide valuable content to your readers, and find an outlet for artistic expression.

Disclosure

Dr. Braslow is the founder of Luminello.com.

MINIDEP: A simple, self-administered depression screening tool

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Venlafaxine discontinuation syndrome: Prevention and management

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

Mind your ABCDs, and your Es, when caring for a ‘difficult patient’

Much has been written about “the difficult patient” in the medical literature.1,2 Also labeled as a “heartsink patient,” “hateful patient,” and “black hole,” they possess characteristics that evoke powerful, often negative, emotional responses in providers that can be counter-therapeutic. “The difficult provider” also is thought to contribute to the failure of the patient encounter,3 and providers may have limited awareness of these patient–provider characteristics that can lead to such interactions. Early identification of these characteristics is essential to implementing effective interventions for the care of a difficult patient.

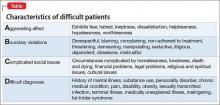

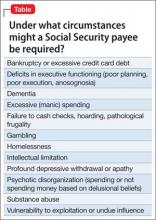

The mnemonic ABCD highlights patient characteristics that suggest you are dealing with a difficult patient (Table).

7 Negatives that affect the provider–patient relationship

The 7 Es highlight negative provider-related variables that contribute to perceived and actual difficulty providing care. As a psychiatrist doing consultation-liaison work, this memory device also can be a tool to educate physician–colleagues, nursing staff, and other members of the treatment team.

Expertise. Lack of basic knowledge or experience with your patient’s condition and circumstances, or not being familiar with available resources, could limit your confidence, be counter-productive, and lead to inappropriate care.

Experiences. Current and past life experiences could negatively color a provider’s feelings, thoughts, and interactions with the patient. Negative interpersonal experiences could manifest as countertransference.